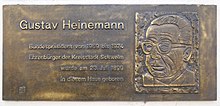

Gustav Heinemann

Gustav Walter Heinemann (born July 23, 1899 in Schwelm ; † July 7, 1976 in Essen ) was a German politician and the third Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany . In his life he was associated with five different parties: In the Weimar Republic he was a member of the student organization of the left-wing liberal DDP and then a member of the Christian Socialist CSVD , after the war he was initially a co-founder of the CDU . Heinemann later co-founded the pacifist GVP and joined the SPD in 1957 .

From 1946 to 1949 he was Lord Mayor of Essen and from 1949 to 1950 Federal Minister of the Interior . Because of the rearmament of the Federal Republic initiated by Konrad Adenauer , he resigned in 1950. He was involved in the peace movement and argued that the integration of the Federal Republic into the NATO , the reunion would make. As an SPD politician, he became a minister again in 1966, in the Kiesinger cabinet ( grand coalition of CDU / CSU and SPD ) as Federal Minister of Justice .

In March 1969 he was elected Federal President. The SPD had organized a majority with the FDP . Heinemann described his election with the much-cited expression "a piece of power change". The actual change of power occurred six months later with a social-liberal coalition at federal level ( Brandt I cabinet ).

Heinemann, who saw himself as a “citizen president”, was committed to the socially excluded and advocated the liberal and democratic legacy of German history. To this end, shortly before the end of his term in office in 1974, he founded the memorial for the freedom movements in German history . Heinemann did not run for a second term and died two years later.

Live and act

Youth and school years (1899-1919)

Gustav Walter Heinemann was the first of three children of Otto Heinemann , who was then authorized signatory at Friedrich Krupp AG in Essen, and Johanna Heinemann (1875–1962). He got his two first names after his maternal grandfather, a master roofer in Barmen . Like Heinemann's father, the latter was radical democratic, left-wing liberal and patriotic and did not belong to any church . His father, Heinemann's great-grandfather, took part in the March Revolution in 1848 . Gustav Walter taught his grandson the Heckerlied as a child .

As a high school student, Gustav wrote a play that was retained and played for the Federal President by Berlin students in 1971 on his 72nd birthday. It contained leitmotifs of his life, for example in which the hero speaks to the antihero:

“I will never regret having spoken to truth and law. Only use brute force to silence me! Right is right! You will have to hear me in front of the chair of the judge who will challenge you! "

Heinemann felt obliged to overcome the German spirit of submission by preserving and developing the liberal-democratic traditions of 1848, which later enabled him to be spiritually independent from church and party majorities.

After a Notabitur 1917 at the Goethe School in Bredeney Heinemann took as a soldier in World War I in part. He became the top gunner of the field artillery regiment No. 22 in Münster , but had to break off his military career after three months because of an inflammation of the heart valves. He did not experience the front. At the Krupp company he performed auxiliary services until the end of the war.

Studies, family, job

Heinemann had wanted to become a lawyer since eighth grade . From 1919 he completed a degree in law , economics and history at the universities of Münster , Marburg , Munich , Göttingen and Berlin , which he completed in 1922 with the first state examination . His first doctorate took place in 1922 as Dr. rer. pole. at the Philipps University in Marburg. In 1926 he passed the second state examination in law. From 1926 to 1928 he worked as a lawyer in Essen. In 1929 he received his doctorate to become Dr. jur.

During his studies in Marburg, Heinemann made lifelong friends, including the economic liberal Wilhelm Röpke , the trade unionist Ernst Lemmer and the economist Viktor Agartz . Like his father, he was a member of the German Monist Association of Ernst Haeckels and, with Röpke and Lemmer, was involved in the Reich Association of German Democratic Students , the student organization of the German Democratic Party (DDP). In Munich he heard Adolf Hitler speak on May 19, 1920 and was thrown out of the room after an interjection against his hatred of Jews .

Since October 24, 1926 he was married to Hilda Ordemann . Their daughter Uta was born in 1927 and their daughter Christa in 1928; their daughter Christina later married Johannes Rau . A third daughter, Barbara, was born in 1933 and their son Peter was born in 1936 . Hilda Heinemann had studied Protestant theology with Rudolf Bultmann and passed the state examination in 1926 and was a regular attendee of church services in the Essen-Altstadt parish. Their pastor Friedrich Wilhelm Graeber brought her husband, who was distant from the church, closer to the evangelical faith through his hands-on and realistic preaching. Through his wife's sister, Gertrud Staewen , a resistance fighter during the National Socialist era, Heinemann met the Swiss theologian Karl Barth , who had a strong influence on him. Like him, Heinemann, as a democrat , resolutely rejected all nationalism and anti-Semitism .

From 1929 to 1949 Heinemann was legal advisor at the Rheinische Stahlwerke in Essen. From 1930 to 1933 he was a member of the Christian Social People's Service , but in 1933 he elected the SPD to defend against National Socialism . Otherwise he was not politically active, but professionally as a lawyer. In 1929 he published a book on statutory health insurance physicians . From 1933 to 1939 he was given a teaching position for mining and commercial law at the University of Cologne . From 1936 to 1949, in addition to his legal work, he was also a mine director at Rheinische Stahlwerke in Essen.

During the Weimar Republic, Heinemann belonged to the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold organization for the protection of the republic .

Participation in the church struggle (1933–1945)

In the time of National Socialism , Heinemann became involved from 1933 against state attacks on the church. As a presbyter (head of the church) in his home parish in Essen, the Paulus parish, he experienced Graeber's removal from office by the new church leadership of the German Christians . This then formed an independent local congregation with its own meeting room; Heinemann ensured that this continued to be a legal member of the Rhenish regional church. To this end, he wrote to Hitler in November 1933 and asked the "dear Mr. Reich Chancellor", "that the actual bearers of church life in our communities can be heard by the official bodies".

Because of his legal competence, Heinemann soon became supra-regional legal advisor to the Confessing Church and spokesman for the Synodal (church members) of the Rhineland in the Confessing Church. As such, he took part in the Barmen Confessing Synod in 1934 and helped revise the Barmen Theological Declaration . After that he often produced illegal pamphlets for the Confessing Church in the basement of his house and sent them across the Reich. In doing so he always remained cautious and conciliatory towards state authorities. He was never arrested until 1945.

As only became known in 2009, Heinemann was a member of two formal Nazi organizations, but was not a member of the "party", the NSDAP , itself. In his curriculum vitae for the Allied occupation authorities of January 23, 1946, he did not provide any information: Firstly, it was about the National Socialist Legal Guardian Association (NSRB), to which all lawyers working as judges, lawyers, legal advisors or notaries had to belong under National Socialism, if they did not wanted to attract attention negatively; and secondly, about the National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV), which after the prohibition of the workers' welfare organization "brought into line " the welfare associations by not dissolving the organizations that were introduced (e.g. DRK , station mission , Caritas , Diakonie , church hospitals and kindergartens) , but should strongly push back and standardize through special government funding. Both NS organizations did not belong to the NSDAP, they were "associated" with the party, but without compulsory membership.

The Rhenish regional church is one of the Uniate churches of the Old Prussian Union . There, Lutherans and Reformed Protestants represent a common evangelical belief towards Catholicism as "Protestants" . Accordingly, Heinemann always saw himself simply as a Protestant Christian who felt and rejected the internal Protestant contradictions as a sterile incidental matter. The church struggle reinforced his belief that denominationalism must be overcome. At the Reich Synod in Bad Oeynhausen in 1936, he and three pastors protested sharply against the formation of a Lutheran council , the resulting split in the Confessing Church and the devaluation of the United Christians. Instead, he demanded a strengthening of the congregations vis-à-vis the church leadership and a more precise, more critical analysis of the political situation. Since this was subsequently rejected, he resigned from his offices in the Confessing Church in the spring of 1939. As the presbyter of his congregation in Essen, he continued to help persecuted Christians with legal advice and provided hidden Jews with food.

From 1936 to 1950 he was also chairman of the Christian Association of Young Men (YMCA) in Essen. In the YMCA he wanted to encourage the younger generation to come together "against the onslaught of organized antichristism", but also to help ensure that the Lutheran and Reformed "confessional churches" would preserve the knowledge they had gained in the church struggle in the future and would not fall back into rigid demarcations.

Church and political offices in the post-war period (1945–1949)

In October 1945, Heinemann and other council representatives of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) signed the Stuttgart confession of guilt , which he understood from then on as the "linchpin" of his church-political work. From 1949 to 1962 he was a member of the leadership of the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland . From 1949 to 1955 he also served as President of the all-German synod of the EKD and was involved in the constitution of the German Evangelical Church Congress ; he was a member of the EKD Council until 1967.

In this function he concluded the first official Protestant church convention in Essen in 1950 (which was later counted as the second church convention) in front of around 180,000 participants with the much-noticed words to the peoples of the world:

“Our freedom was bought at a dear price through the death of the Son of God. Nobody can put us in new chains, because God's Son is risen. Let us answer the world, if it wants to make us afraid: Your masters are going - but our master is coming! "

From 1948 to 1961 he was also a member of the International Affairs Commission in the World Council of Churches .

From 1951 Heinemann was one of the editors of the magazine “ Voice of the Congregation” , which has been the central organ of the Confessing Church since the church struggle. The Brother Councils of the Confessing Church and opponents of rearmament and rearmament in the EKD, organized as regional church brotherhoods since 1956, gathered there .

After the end of the war, Heinemann was among the co-founders of the CDU , which he affirmed as a non-denominational, democratic party supported by opponents of the NSDAP . The British occupation forces made him mayor of Essen. In 1946 he was elected mayor there and held this office until 1949. In his role as Essen mayor, Heinemann was also chairman of the supervisory board of the Süddeutsche Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (SEG) from 1945 to 1949 and remained a member of the SEG supervisory board until 1952. From 1946 to 1950 he was also a CDU member of the state parliament in North Rhine-Westphalia . From June 17, 1947 to September 7, 1948 he was a member of the government of North Rhine-Westphalia led by Prime Minister Karl Arnold (CDU) as Minister of Justice . Even in this office he had his first conflicts with Konrad Adenauer .

Federal Minister of the Interior (1949–1950)

Adenauer was elected the first Federal Chancellor of the new Federal Republic of Germany on September 15, 1949 . Despite the narrow majority in the Bundestag, he rejected a grand coalition with the SPD that was supported by parts of his party. After the CDU parliamentary group had criticized the excessive distribution of ministerial posts to Catholics in Adenauer's planned cabinet, Heinemann appointed Heinemann as Federal Minister of the Interior on September 20, 1949 in order to emphasize the non-denominational orientation of his government. He made it a condition that Heinemann remain President of the EKD Synod in order to involve him as a representative of the Protestants.

Heinemann followed the call only reluctantly at the urging of his friends and asked them to be allowed to continue his church offices. He regretted having to give up his previous professional work due to uncertain political developments, and only agreed to Adenauer after he had received the binding promise from the supervisory board of Rheinstahl and the Niederrheinische Bergwerksgesellschaft that he would later be able to return to his executive board positions there.

Opponents of rearmament (1950–1953)

At the cabinet meeting on August 31, 1950, Adenauer informed his cabinet that he was conducting secret negotiations on the establishment of a federal police force and a German contribution to a European army and that he was "unifying the US High Commissioner John Jay McCloy in a" security memorandum "on his own initiative Contribution in the form of a German contingent ”. This led to a scandal with Heinemann, who, like the other ministers, had only learned from the newspaper that the Chancellor had also handed over two official memoranda. Heinemann said he was “unable” to “face a fait accompli on the most significant issues in which [he] is involved as a cabinet member and as the minister responsible for police matters,” and offered to resign. Adenauer responded with sharp accusations against Heinemann's activity as minister, "since nothing worth mentioning had been done in the field of the protection of the constitution or in the field of the police in the last few months" and read excerpts from one of the two memoranda. Heinemann then announced his resignation, which Adenauer accepted on October 9th. Heinemann was the first Federal Minister to step down from his office.

In his letter of resignation, in accordance with the statements made by the EKD Synod, which was still all-German, he stated :

“What for Russia and its satellites on the one hand and for the Western powers on the other hand [...] still includes chances of winning or at least survival is death for us in any case, because Germany is the battlefield. [...] we legitimize our Germany itself as a battlefield if we include ourselves in the armament. [...] It is important that the chance for a peaceful solution is not lost. Our participation in the rearmament would hardly leave the emergence of such an opportunity open. [...] Our state apparatus is [...] so little established and consolidated that military power will almost inevitably develop its own political will again. If we consider this danger averted by the fact that the German contingents are in an international army, then it must be considered whether the dependence on an international general staff will be less or more tolerable. [...] We cannot yet speak of an established democratic state consciousness. It will therefore not be possible to prevent anti-democratic tendencies being strengthened and remilitarization leading to renazification. "

Heinemann now worked as a lawyer again and founded a law firm with Diether Posser in Essen. There he campaigned especially for conscientious objectors . In 1952 he resigned from the CDU because of the plans to rearm Germany and founded with Helene Wessel , Margarete Schneider - the widow of Paul Schneider , the murdered "Preacher von Buchenwald " -, Erhard Eppler , Robert Scholl , Diether Posser and others the " Emergency Community for Peace in Europe ”, from which the“ All-German People's Party ” GVP emerged. With Johannes Rau , another later Federal President belonged to this.

It held some positions of the first party program of the CDU, the Ahlen program further and sought a waiver of the Federal Republic to a defense force and strict neutrality between the NATO and the Eastern bloc to reduce the chance for reunification to be kept open and the tradition of German militarism to break up. Instead Heinemann affirmed the establishment of a federal police force of equal strength as the then built up people's police of the GDR .

On March 13, 1952, Heinemann gave a speech in front of thousands of listeners in West Berlin on the first of the Stalin Notes of March 10, 1952. He called for the readiness to seriously consider Stalin's offer for a militarily neutral Germany as a whole. The CDU had called the Berliners to protest with posters, and the hall was filled with hired troublemakers who staged minute-long whistling concerts and tumults to prevent Heinemann from speaking. However, he was not deterred and responded to heckling (“Paid by Moscow!”) Spontaneously by saying that you had paid admission to hear him. You certainly don't want East Berlin newspapers to be able to report that you can no longer speak freely in West Berlin. There are not only eastern fifth columns . This silenced the troublemakers; Heinemann was able to finish his speech in peace.

The GVP won only 1.2 percent of the vote in the 1953 federal election . Nevertheless, he maintained the debate with the GVP about the relationship between rearmament and the reunification of Germany for the next four years.

Converts to the SPD

In 1957 Heinemann represented Viktor Agartz in a trial for treason before the Federal Court of Justice and, after the Spiegel affair, the news magazine Der Spiegel in the trials against Franz Josef Strauss .

In the same year he negotiated with Erich Ollenhauer about converting to the SPD. In return for a promising place on the list, he dissolved the GVP in May 1957 and recommended that its members join the SPD, as Erhard Eppler had already done. Heinemann also became a member of the SPD. In the federal election in 1957 , he ran on the Lower Saxony state list of the SPD and was first a member of the Bundestag and was immediately elected to the executive committee of the SPD parliamentary group. From 1958 to 1969 he was a member of the federal executive committee of the SPD. There he was considered a recognized representative of the social and radical democratic wing in German Protestantism , which at the same time embodied the acceptance of the SPD as a people's party in circles of the industrial bourgeoisie in the Ruhr area .

Also because of Adenauer's political pressure on the EKD Council, Otto Dibelius had suggested Heinemann resign from his position as President of the EKD Synod since January 1951. In 1955 he was voted out of office. His successor was the new Hanoverian regional bishop Johannes Lilje . Dibelius signed the military chaplaincy contract with Adenauer, contrary to a synodal resolution that came about under Heinemann, on February 22nd, 1957 , two months before Heinemann joined the SPD.

Opponents of atomic weapons (from 1957)

In 1957/58 Heinemann was one of the fiercest opponents of the nuclear armament planned by Adenauer and Strauss for the Bundeswehr , as well as all NBC weapons . In a legendary Bundestag speech on January 23, 1958, he and Thomas Dehler carried out a general reckoning of Adenauer's policy in Germany, which he saw as a complete failure, and accused him of fraudulent behavior and defrauding the cabinet and parliament. In this speech he commented on the successful CDU election campaign from the previous federal election, in which Adenauer had declared: “It's about whether Germany and Europe will remain Christian or become communist!” Heinemann criticized this as an ideological appropriation of Christian-Western values for the Cold War :

"It's not about Christianity against Marxism [...] It's about the realization that Christ did not die against Karl Marx , but for all of us!"

The speech provoked violent reactions because it broke the usual pattern, according to which Christian policy is only possible in the CDU and the SPD is a traditionally "atheist" party.

In the second major Bundestag debate on atomic weapons in March 1958, Heinemann, as a speaker for the SPD opposition, referred to Article 25 of the Basic Law , according to which international law is also federal law , and therefore pleaded for a general renunciation of means of mass destruction when building a German defense army. Like Karl Barth, he also argued with the criteria of the Church's teaching of the Just War :

“You [the CDU members] do not need to tell me that, according to the teaching of the two large churches, compulsory military service is given under certain conditions. The question is whether all that [...] will stand up to today's means of mass destruction. "

He then recalled the connection between nuclear weapons and the Holocaust :

"I call the nuclear weapons vermin-killing agents, in which this time humans are supposed to be the vermin ."

He asked "whether there is any reason to justify the use of weapons of mass destruction." To the interjection of a CDU MP - "But self-defense !" - he replied:

"Ladies and gentlemen, self-defense is, according to its meaning and character, a limited defense, but self-defense with weapons of mass destruction is impossible."

In relation to this inclusion of ethically illegitimate mass extermination in armed self-defense that was legitimate in itself, Heinemann had, with reference to the Barmer Theological Declaration of 1934, "the right [...], even the duty to refuse to obey ."

Federal Minister of Justice (1966–1969)

On December 1, 1966, at the suggestion of Willy Brandt , Heinemann was appointed Federal Minister of Justice in the grand coalition led by Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger . This was also welcomed by representatives of other parties who had long been campaigning for a much-discussed major criminal law reform, such as Thomas Dehler (FDP) and Max Güde (CDU), while the Federal Prosecutor's Office reacted skeptically.

Heinemann had two reforms before them: a conservative one that focused more on deterrence (1962) and a liberal one that was more focused on crime prevention and rehabilitation of offenders (1966). He managed to incorporate many of the latter ideas into a compromise draft on general criminal law. In 1969, for example, prison sentences were legally replaced by imprisonment , which included regular rehabilitation offers. Prison sentences of less than six months could only be imposed in exceptional cases so as not to encourage recidivism among first-time offenders. Minor offenses have been downgraded to administrative offenses .

The political criminal law, which was in part only created in 1951, was liberalized in June 1968 with the 8th Criminal Law Amendment Act: Since then, legal remedies can be lodged against judgments in state protection criminal cases that were previously legally incontestable . The risk of "convictions" should be reduced. Detainees convicted under the repealed provisions were given amnesty. At the same time, Heinemann strongly advocated the extension of the statute of limitations for Nazi crimes. In fact, the so-called Introductory Act to the Law on Administrative Offenses (EGOWiG), drafted by the ministerial official Eduard Dreher , came into force in October 1968 , as a result of which the acts of all assistants in National Socialist murders were statute-barred in one fell swoop (see Eduard Dreher # Statute of Limitation Scandal ).

He paid special attention to sexual law and made sure that adultery and practiced male homosexuality ( Section 175 ) are no longer criminal offenses. Children born out of wedlock and children born in wedlock were treated on an equal footing and received the same right to maintenance. Heinemann justified this with pragmatic reason and the principle of equality of the Basic Law. In the case of homosexuality, for example, he argued with equality between men and women, since lesbian relationships were not criminal. In the case of adultery, he referred to statistics according to which no more than a sixth of all known cases were punished and this had no discernible effect on social morality. This is only shaped to a very limited extent by Christian morals, and it is not desirable to revise this through authoritarian state laws. On the question of abortion, however, he deviated from the SPD majority and only advocated the ethical indication in the case of rape.

Many of the reforms introduced by Heinemann only became concrete after his term of office and became legally effective, for example, with the 9th Criminal Law Amendment Act. He only saw them as the first step. The decisive factor for him was to adapt the legal system to social change on the one hand, and to protect the disadvantaged on the other.

With the responsible Minister of Labor, Hans Katzer , he also campaigned - initially in vain - to recognize the total refusal of war and alternative service for reasons of conscience and not to punish it several times through repeated conscription. This particularly affected the Jehovah's Witnesses , whom he had often defended in court as a lawyer. He referred to the efforts of the churches in the GDR to create an equal civil service, independent of the state, in place of the " building soldiers " companies. On March 7, 1968, the Federal Constitutional Court followed his view and banned the multiple punishments of those who refused to go to war and alternative service, whose "flight" goes back to a decision of conscience made once and for all.

To the surprise of his followers, Heinemann stood up for the emergency laws on May 10, 1968 , which the student movement and parts of the trade unions in particular vehemently opposed. It was feared that a future government could declare a state of emergency for no real reason and thereby bring it about. Heinemann, on the other hand, recalled Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution , the implementing law of which was never passed and just allowed anti-democratic rulers to exercise arbitrariness. Since the Basic Law did not have a comparable article, the CDU-led federal governments had drawn up drafts for an emergency over the years and passed them on to all departments as "classified information". The SPD has found and eliminated these “pigeonhole laws” since joining the grand coalition. The emergency laws should protect the citizens from such arbitrary government "in an emergency".

At the beginning of April 1968, Heinemann published an article in the SPD magazine Die neue Gesellschaft under the title “The Vision of Human Rights ”. In it, he pleaded not only for radical university reforms, but also for an analysis of the societal lack of ideas and the stalemate from which he explained the unrest among students. Utopianism helps just as little as mere technocracy of power: “We need 'realists with vision' ( John F. Kennedy ), sober realists with imagination, who have the image of a better order in their hearts and are filled with the will for more and better justice to fight for when it is here and now. ”He advocated the expansion of liberal civil rights through social, economic and cultural human rights. The tradition of the German authoritarian state must be ended.

"We still come from centuries of education to obedience to the authorities and, above all, from an aversion to anything unusual, and thus also to minorities."

Two days after the assassination attempt on Rudi Dutschke and the partly violent protests against it, Federal Chancellor Kiesinger described the students on April 13, 1968 as "militant left-wing extremist forces" and enemies of the parliamentary order and thus indirectly made them responsible for the assassination. There were also calls from the CDU to restrict the right to demonstrate. Heinemann responded to this on the following day (Easter Monday) with a statement in which he unequivocally rebuked Kiesinger, but also violent protesters:

"Anyone who points with the index finger of general allegations at the alleged instigator or mastermind should consider that in the hand with the outstretched index finger three other fingers are pointing back at him."

He saw the protest as a symptom of a deep crisis of confidence in democracy. Violence is injustice and "stupidity on top of that". But:

“One of the basic rights is the right to demonstrate in order to mobilize public opinion. The younger generation also has the right to be heard and taken seriously with their wishes and suggestions. "

While this triggered great public outrage at the time, Heinemann found praise and recognition from APO supporters: According to Ivan Nagel , “by speaking out the truth of the two-sided guilt”, he made a decisive contribution to the de-escalation and reconciliation of the generations.

Federal President (1969–1974)

choice

After the SPD announced its claim to the office of third Federal President in June 1967, Heinemann was initially not considered the SPD's favorite. He did not appear to the party chairman Willy Brandt as a suitable candidate until autumn 1968 because he reached the younger generation, especially the student movement, and shared their concerns about a comprehensive democratization of society and all political institutions. The CDU / CSU parliamentary group nominated Defense Minister Gerhard Schröder , who was considered to be conservative, instead of Richard von Weizsäcker , who was part of the liberal CDU party spectrum and favored by Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger . The FDP avoided any definition in advance.

In the election on March 5, 1969 , Heinemann received 513 of 1,036 electoral votes in the first ballot , in the second only 511, Schröder 507. In the third ballot, a simple majority of 512 to 506 votes was enough for him to be elected third Federal President. The decisive factor was the votes of the FDP, of whose 83 members of the Federal Assembly 78 had previously agreed internally to vote for Heinemann. "The fact that Gustav Heinemann was elected Federal President removed the last prejudice in public opinion about the ability of the SPD to govern," wrote Carlo Schmid in his memoirs , which he published ten years later. Above all, it signaled that an SPD / FDP coalition, as it had come about after the state elections in North Rhine-Westphalia in 1966 , was also possible in the federal government. Accordingly, after the federal election on September 28, 1969, such a coalition with Willy Brandt as Federal Chancellor came about in a very short time .

Understanding of office and conduct of office

Heinemann saw himself as a "citizen president" and showed this when he took office on July 1, 1969 with the words:

“[W] e are only at the beginning of the first really free period in our history. […] Everywhere authority and tradition have to put up with the question of their justification. [...] Not less, but more democracy - that is the demand, that is the great goal to which we all, and especially the youth, have to subscribe. There are difficult fatherlands. One of them is Germany. But it is our fatherland. "

He tried to serve this goal in office with frequent criticism of systemic deficiencies in post-war democracy. He wanted to strengthen the citizens' initiative towards parties and authorities and plebiscite elements as a complement to parliamentarianism. In doing so, he polarized opinions and was devalued by some conservatives as an "apo-grandpa".

In his inaugural address, Heinemann also emphasized the obligation of all politics to make peace : "War is not an emergency [...], but peace is an emergency in which we all have to prove ourselves." 1970 the German Society for Peace and Conflict Research (DGFK) founded. It was initially supported by the federal government and the eleven state governments as well as important social associations, including the DGB , the BDI , the BDA , the Council of the EKD, the German Bishops' Conference , the Central Council of Jews in Germany . She received around three million DM annually: only a fraction of the simultaneous expenditure on armaments research. In 1983, however, the new federal government under Helmut Kohl and the CDU-led states terminated the contract with the DGFK. It is only continued with projects at a few universities.

Long before his election, when asked whether he did not love this state, the Federal Republic, as an applicant for the federal presidency, he had made his attitude to the subject of patriotism clear in a much-quoted way: “Oh, I don't love any states, I love my wife; finished!"

He took part in the commitment of his wife Hilda, who founded a foundation for the mentally handicapped, worked for drug addicts and female prisoners and took over the patronage of Amnesty International .

Concerning the role of the Bundeswehr , Heinemann judged: "Every Bundeswehr must be fundamentally ready to allow itself to be questioned in order to find a better political solution." With this statement, Heinemann outraged the CDU / CSU in particular. The CSU chairman Franz Josef Strauss said that from there it was only a small step to say that "the Bundeswehr stands in the way of reunification". Contrary to the concerns of the conservatives, Heinemann, as Federal President, cultivated friendly relations with the leaders of the Bundeswehr, visited military facilities and soldiers' units, as well as community service. He remained uncomfortable for the new government under Willy Brandt and warned when it was sworn in: “You too are no longer entrusted with controlled power for a period of time. Use this of your time. "

During his tenure, Heinemann paid the further incoming pension payments from the Rheinische Stahlwerke into a fund with which he supported people for whom he could not do anything ex officio. In 1970, for example, he helped Rudi Dutschke and his family with DM 3,000 when they moved to Cambridge . After serious allegations by CDU MP Gerhard O. Pfeffermann , Heinemann admitted this assistance in 1975, but denied having used public funds for it.

During the multi-week fare riots in Dortmund in March 1971 , Heinemann received representatives of the Communist-dominated Action Committee for an interview in which he pointed out the scarce resources of the municipality and found the "less presidential" formulation: "Do you think the mayor has a ducat shit?"

The attacks by the Red Army Faction (RAF) and especially the attack on Israeli athletes at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich hit Heinemann hard. As a radical democrat, he condemned the terrorist acts and emphasized: "Objectively, anarchists are the best helpers of the reactionaries." At the same time, he warned the government and authorities against overreactions: The state is strong enough to put violent criminals in their place. A call to the RAF to stop the “armed struggle” was not broadcast at Willy Brandt's request.

Heinemann not only invited diplomats to traditional New Year's receptions, but also ordinary citizens of particularly polluted or despised professions, such as nurses, garbage collectors, pool attendants, guest workers, the disabled and those doing community service. He tried to abolish courtly ceremonies and allowed invited gentlemen to bring not only their wives but also other female companions. He avoided large banquets with thousands of guests and preferred to receive state guests in a small group with a private atmosphere. His last guest, three days before leaving office, was Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito .

Heinemann campaigned for the foundation of the memorial for the freedom movements in German history in Rastatt and opened it on June 26, 1974. His commitment to Rastatt as a memorial site also had a personal background: Carl Walter, a brother of his great-grandfather, had participated as a barricade fighter as part of the imperial constitution campaign in the May uprising in Elberfeld in 1849 and then joined the revolutionaries of Baden . After the revolution of 1848/49 was finally put down , he died as a prisoner in the casemates of the Rastatt fortress .

Visits abroad

In office, Heinemann worked very hard for reconciliation with the European states occupied by Germany under the Nazi regime. In November 1969, he was the first Federal President to visit the Netherlands , the population of which at that time still had considerable reservations about the Germans. Heinemann immediately made it clear in his welcoming speech that “we in Germany remain aware of the suffering we are causing the Dutch people”. He and his wife also became friends with the Dutch royal couple.

In May 1970 he visited Japan to open the World Exhibition ( Expo '70 ) in Osaka . During the internal preparations, despite the Foreign Office's concerns, he pushed through to visit Hiroshima on this occasion . He laid a wreath at the memorial of the atomic bomb dome to commemorate the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki , and warned that all people are responsible for ensuring that "our path does not lead to a disaster".

In the following summer and autumn he traveled to the Scandinavian countries. With King Frederik IX. he got on very well with Denmark. In 1972 he attended his funeral. He had to cancel a planned trip to Iran for the 2500th anniversary of the peacock throne because of an eye operation. In March 1971 he made a trip to Latin America to Venezuela , Colombia and Ecuador . As the first German Federal President, he also visited an Eastern Bloc country , Romania , in May 1971.

In October 1972 he visited Switzerland and Great Britain , in 1973 in Italy , the Vatican and in Luxembourg , and in 1974 in Belgium .

The last years of life (1974–1976)

Although the majority would have enabled him to be re-elected, Heinemann decided not to run for a second term due to health and age reasons and resigned from the office of Federal President on July 1, 1974. When saying goodbye, he renounced the usual big tattoo of the Bundeswehr and instead invited them to a boat trip on the Rhine .

Heinemann had visited prisons several times during his tenure. After his departure, he wrote to Ulrike Meinhof in December 1974 to call off a hunger strike by the “ Baader Meinhof Group ” in prison. Heinemann had known Meinhof since 1961, when he had defended her in criminal proceedings for insult . Heinemann wrote to "Dear Ms. Meinhof" that he was seriously concerned about her life and that of her friends. The conditions of detention against which the hunger strike is directed are "- at least today - largely irrelevant". With a "self-sacrifice" it does not achieve any political effects, but only complicates the efforts of those who "seek improvement in other ways" for the socially disadvantaged. In her reply, Ulrike Meinhof refused to end the hunger strike as long as no “consolidation of all political prisoners” and “lifting of isolation torture” had been achieved. You do not want to be "fobbed off with any modification of special treatment". She asked Heinemann to get permission to visit. He immediately refused: “The court with sole responsibility for the prison conditions will not grant anything that would enable you and your group to continue a revolutionary struggle in the prison.” As a result, Heinemann was sharply criticized by conservative voices for his letter: Not Most recently, when he addressed Meinhof, he had "upgraded" the Red Army faction . The theologian Helmut Gollwitzer , in whose Dahlem house Heinemann had a second home, in which he stayed in May 1976, reported that Heinemann had whispered in response to the news of Meinhof's death (May 9, 1976): “It is now in God's gracious hand - and with everything she did, as incomprehensible as it was to us, she meant us. "

Heinemann was opposed to the so-called radical decree of January 28, 1972, which was supposed to protect the public service from enemies of the constitution. He considered the current civil service law to be sufficient, as this also required civil service applicants to stand up for the free and democratic basic order on a permanent basis . On May 22nd, 1976, shortly before his death, his essay Frankish Criticism and Democratic Rule of Law was published , in which he wrote: “Care must be taken that the Basic Law is not protected with methods that are contrary to its aim and spirit. "

The "review of entire vintages", which has become common due to regular inquiries, is "exaggerated" and stirs up "the fear of communist infiltration":

“We have to adhere all the more clearly to the fact that a free society is also a society in motion. It cannot be a finished and permanent state. Their further development must be carried out consciously so that there are no relapses. "

He warned against the tendency to restrict civil liberties in the context of the state's fight against terrorism and the suspicion of radical democrats as terrorists:

"The state should once again be understood as that high thing floating above us, which exists independently of parliaments, parties and popular sovereignty as the epitome of exercising power [...] But if radical criticism of constitutional reality is now consciously confused with anti-constitutional extremism, it applies To sound the alarm. "

Heinemann biographer Helmut Lindemann saw this alarm as his legacy and therefore called it “the most convincing example of a radical in the public service”. In 1995 the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg ruled that the recruitment practice of German authorities associated with the Radical Decree is incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights .

“The basis of democracy is popular sovereignty and not the rulership of an authoritative state. It is not the citizen who obeys the government, but the government is responsible to the citizen for its actions within the framework of the law. The citizen has the right and the duty to call the government to order if he believes that it is disregarding democratic rights. "

Death and inheritance

Heinemann died on July 7, 1976 in Essen as a result of circulatory disorders in the brain and kidneys . At his request, he was buried by his closest friend Helmut Gollwitzer in the Essen Park Cemetery, where he was given an honorary grave . Gollwitzer said in his mourning address:

“He saw clearly how what needs to be done cannot be done because too many of those who are at the various levers of power either do not want to do it or do not want to have done it [...] So he spoke more and more often about the ungovernability of the world and concluded some conversations with the sentence: 'Bring this world in order!' "

The estate of Gustav Heinemann is in the archive of social democracy of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung . He has given at least 2,500 public speeches in his life, of which he himself carefully listed 2,074 speech manuscripts from 1946 to 1969. His bibliography, compiled by his estate administrator Werner Koch, comprises 1285 individual titles.

Cabinets

- Cabinet Arnold I (North Rhine-Westphalia)

- Cabinet Adenauer I (Federation)

- Kiesinger cabinet (federal government)

Honors

Awards during his lifetime

In 1969, as Federal President, he received the special level of the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany and in 1973 the Grand Cross with Great Chain of Merit of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic , the major star of the Honorary Sign for Services to the Republic of Austria and the Nassau House Order of the Golden Lion . He also received the Grand Cross of the British Order of the Bath . He himself had always refused medals and, as Federal President, tried in vain to abolish the grading of the Federal Cross of Merit.

The honorary doctorate was awarded to Heinemann in 1963 by the University of Bonn (theology), in 1970 by the Philipps University of Marburg , on October 27, 1972 by the University of Edinburgh (Dr. jur.) And on June 21, 1974 again as an honorary doctorate of the rights of of the New School for Social Research in New York.

The Deutsche Bundespost issued a series of stamps .

Heinemann as the namesake

The following were named after Gustav Heinemann:

- the Gustav Heinemann Initiative (1977 to 2009, then united with the Humanist Union )

- the Gustav Heinemann Citizen Prize (donated by the SPD in 1977)

- the Gustav Heinemann Peace Prize for books for children and young people (since 1982)

- the Gustav Heinemann educational facility on the Kellersee in Bad Malente-Gremsmühlen (renamed in 1983 in honor of Heinemann)

- numerous schools

- the Gustav Heinemann barracks in Essen-Kray, which closed in 2003

- the Gustav Heinemann Bridge in Berlin-Mitte over the Spree (inaugurated in 2005)

- the Gustav-Heinemann-Bridge in Essen-Werden over the Ruhr

- the Gustav Heinemann Bridge in Minden over the Weser

- the Gustav-Heinemann-Ring in Munich .

- the Gustav Heinemann Comprehensive School in Mülheim an der Ruhr .

- the Gustav-Heinemann-Bürgerhaus in Bremen- Vegesack

Trivia

Gustav Heinemann was jokingly called “Dr. Gustav Gustav Heinemann ”- an allusion to his two doctoral degrees (“ Dr. Dr. Gustav Heinemann ”). The minutes of his assumption of office as Federal President on July 1, 1969 also noted in the first place the honorary doctorate in theology from the University of Bonn: “D. Dr. Dr. ".

Works

- The savings activity of the Essen Krupp factory employees with special consideration of the Krupp savings facilities . Dissertation, 1922.

- The administrative rights to third-party assets . Dissertation, 1929.

- Call to the emergency community for peace in Europe. Speeches at a public rally in the state parliament building in Düsseldorf. With Helene Wessel and Ludwig Stummel , 1951.

- German peace policy. Speeches and essays. Publisher Voice of the Community, Darmstadt 1952.

- Germany and world politics. Ed. Notgemeinschaft für die Frieden Europa, 1954.

- What Dr. Adenauer forgets. Frankfurter Hefte 1956.

- Workshop "Understanding with the East?" March 25, 1956 in the Hotel Harlass in Heidelberg. Published by Ehrenberg Association of North Baden Adult Education Centers, 1956.

- At the intersection of time . With Helmut Gollwitzer , speeches and essays, Verlag Stimm der Gemeinde, Darmstadt 1957.

- The mountain damage. Engel Verlag, 3rd edition, 1961.

- Missed Germany policy. Deception and self-deception . Articles and speeches, Voice Publishing House, Frankfurt / M. 1966.

- Why I am a social democrat. Ed. SPD executive committee, 1968.

- Commemorative speech on July 20, 1944. Lettner-Verlag, 1969.

- On the founding of the Empire in 1871 - on the 100th birthday of Friedrich Ebert. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1971.

- A plea for the rule of law. Political speeches and essays. C. F. Müller, 1969.

- Speeches and interviews by the Federal President (July 1, 1969 - June 30, 1970). Ed. Press and Information Office of the Federal Government, 5 volumes, 1970–1974.

- Presidential speeches. Edition suhrkamp 790, Frankfurt / M. 1975.

- Reconciliation is more important than victory (= edifying speeches 3). Four Christmas speeches 1970–1973 and H. Gollwitzer's speech at the funeral of G. Heinemann in 1976. Neukirchen 1976.

-

Speeches and writings:

- Volume I: Committed to all citizens. Speeches by the Federal President 1969–1974 , Frankfurt / M. 1975.

- Volume II: Freedom of Belief - Citizenship Freedom. Speeches and essays on the church, state - society. Ed. Diether Koch (with thematically sorted bibliography), Frankfurt / M. 1976.

- Volume III: There Are Difficult Fatherlands ... Essays and Speeches 1919–1969. Munich 1988, published by Helmut Lindemann, Frankfurt 1977.

- Volume IV: Our Basic Law is a large offer. Legal writings. Edited by Jürgen Schmude, Munich 1989.

- We have to be democrats. Diary of the academic years 1919–1922. Edited by Brigitte and Helmut Gollwitzer, Munich 1980.

- Peace is the real thing. Edited by Martin Lotz, Kaiser Traktate 59, Munich 1981 (14 texts 1951–1973).

- Objection. Encouragement for staunch Democrats. Edited by Diether Koch, Verlag JHW Dietz Successor, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-8012-0279-8 .

- Gustav W. Heinemann. Bibliography. Edited by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Archive of Social Democracy, edited by Martin Lotz, Bonn-Bad Godesberg 1976 (1,285 titles from 1919 to 1976).

literature

Biographical

- Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, Munich 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 .

- Carola Stern: Two Christians in Politics. Gustav Heinemann, Helmut Gollwitzer. Christian Kaiser, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-459-01229-3 .

- Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (Ed.): Gustav Heinemann. Christian, patriot and social democrat. An exhibition of the archive of social democracy. (Booklet accompanying the exhibition, Bonn).

- Hermann Vinke: Gustav Heinemann. Lamuv-Verlag, Bornheim-Merten 1986, ISBN 3-88977-046-0 .

- Rudolf Wassermann: Gustav Heinemann. In: Claus Hinrich Casdorff: Democrats. Profiles of our republic. Königstein / Taunus 1983, pp. 143–152.

- Ruth Bahn-Flessburg: Passion with a sense of proportion. Five years with Hilda and Gustav Heinemann. Christian Kaiser Verlag, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-459-01564-0 .

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Heinemann, Gustav. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 664-665.

- Diether Koch: Heinemann, Gustav Walter. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 17, Bautz, Herzberg 2000, ISBN 3-88309-080-8 , Sp. 620-631.

- Thomas Flemming: Gustav W. Heinemann. A German citizen. Biography. Klartext, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0950-2 .

Church representatives

- Ulrich Bayer: Between Protestantism and Politics. Gustav Heinemann's way in post-war Germany 1945 to 1957. In: Jörg Thierfelder, Matthias Riemenschneider (Ed.): Gustav Heinemann. Christian and politician. With a foreword by Manfred Kock. Hans Thoma Verlag, Karlsruhe 1999, pp. 118-149.

- Werner Koch: Heinemann in the Third Reich. A Christian lives for tomorrow. ISBN 3-7615-0164-1 .

- Manfred Wichelhaus: Religion and Politics as a Profession. In: Bergische Blätter 1979, Heft 7, pp. 12-2100813X.

- Manfred Wichelhaus: Political Protestantism after the war in the judgment of Gustav Heinemann. In: Titus Häussermann and Horst Krautter (eds.): The Federal Republic and German History. Gustav Heinemann Initiative, Stuttgart 1987, pp. 100-120.

- Joachim Ziegenrücker: Gustav Heinemann - a Protestant statesman. In: Orientation. Reports and analyzes from the work of the Evangelical Academy in Northern Elbe. No. 4 (Oct-Dec 1980), pp. 11-23.

Politician

- Walter Henkels : 99 Bonn heads , reviewed and supplemented edition, Fischer-Bücherei, Frankfurt am Main 1965, p. 121f.

- Dieter Dowe , Dieter Wunder (ed.): Negotiations on reunification instead of armament! Gustav Heinemann and the incorporation of the Federal Republic into the Western military alliance. Research institute of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn 2000, ISBN 3-86077-961-3 (Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung / History Discussion Group ; Vol. 39).

- Gotthard Jasper : Gustav Heinemann . In: Walther L. Bernecker, Volker Dotter Weich (eds.): Personality and Politics in the Federal Republic of Germany , Vol. 1. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1982, ISBN 3-525-03206-4 , pp. 186-195.

- Diether Koch: Heinemann and the German question. Christian Kaiser, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-459-00813-X .

- Diether Posser : Memories of Gustav W. Heinemann. Lecture at an event of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation and the Federal Archives on February 25, 1999 in Rastatt Castle. Research Institute of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Historical Research Center, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-86077-810-2 (Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung / History Discussion Group ; Vol. 24).

- Jörg Treffke: Gustav Heinemann, wanderer between the parties. A political biography. Schöningh, Paderborn (inter alia) 2009, ISBN 978-3-506-76745-5 .

- Hans-Erich Volkmann: Gustav W. Heinemann and Konrad Adenauer. Anatomy and political dimension of a falling out. In: History in Science and Education , vol. 38, 1987, H. 1, pp. 10–32.

- Jürgen Wendler: Walking upright through changeful times. Democrats can still learn a lot from Gustav Heinemann, who would have turned 100 today. In: Weser Kurier, July 23, 1999.

- Rainer Zitelmann : Democrats for Germany: Adenauer's opponents - fighters for Germany. Ullstein TB Contemporary History, Frankfurt / M. 1993, ISBN 3-548-35324-X .

Federal President

- Joachim Braun: The uncomfortable president. CF Müller, Karlsruhe 1972, ISBN 3-7880-9557-1 .

- Gustav W. Heinemann, Heinrich Böll, Helmut Gollwitzer, Carlo Schmid: impetus and encouragement. Federal President 1969–1974. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1974, ISBN 3-518-02046-3 .

- Hermann Schreiber, Frank Sommer: Gustav Heinemann, Federal President. Fischer-TB (1st edition 1969), Frankfurt / Main 1985, ISBN 3-436-00948-2 .

- Ingelore M. Winter: Gustav Heinemann. In: Our Federal Presidents. From Theodor Heuss to Richard von Weizsäcker. Six portraits. Düsseldorf 1988, pp. 91-129.

- Daniel Lenski: From Heuss to Carstens. The understanding of office of the first five Federal Presidents with special consideration of their constitutional competences. EKF, Leipzig / Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-933816-41-2 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Gustav Heinemann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Gustav Heinemann in the German Digital Library

Biographical

- Gustav Heinemann. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Short biography of Gustav Heinemann bundespraesident.de

- Uta Ranke-Heinemann: My father, Gustav the Karge . Speech on the 30th anniversary of Gustav Heinemann's death on August 22, 2006 in the house of the church in Essen.

- Uta Ranke-Heinemann: The BDM cellar in my father's house. In: Alfred Neven DuMont (ed.): Born 1926/27, memories of the years under the swastika. Cologne 2007, pp. 95-106.

- Wolfgang Beutin: "Peace is an emergency" - Radical democrat and anti-fascist: Gustav Heinemann (1899–1976), a "Citizen President" of the Federal Republic Obituary in Junge Welt , July 22, 2006; documented on ag-friedensforschung.de

Audio documents

- Gustav Heinemann: Radio address on his resignation as Federal Minister of the Interior on October 9, 1950 ( RAM ; 0 kB)

- Gustav Heinemann (GVP): The parliamentary majority is not always right - Against West German armament (RAM; 0 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ When the NPD almost decided the election of the Federal President

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , p. 28

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , p. 14

- ↑ Gustav Heinemann (1969–1974) on bundespraesident.de

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , p. 32

- ^ Hermann Vinke : Gustav Heinemann . Lamuv-Verlag, Bornheim-Merten 1986, ISBN 3-88977-046-0 , p. 42.

- ↑ Jörg Treffke: Gustav Heinemann. Wanderer between the parties. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2009, ISBN 978-3-506-76745-5 , p. 272, footnote 158.

- ^ Diether Koch: Heinemann, Gustav Walter. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 17, Bautz, Herzberg 2000, ISBN 3-88309-080-8 , Sp. 620-631.

- ↑ Hans Prolingheuer: Small political church history. Cologne 1984, p. 120

- ^ Gustav Heinemann at the state parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , p. 89

- ↑ August 29, 1950 Memorandum of the Federal Chancellor on the internal and external security of the federal territory

- ^ 93rd Cabinet meeting, August 31, 1950

- ^ Hans-Peter Schwarz : Adenauer. The rise 1876–1952. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1986, p. 766 f.

- ^ Draft letter of resignation (September 3, 1950)

- ↑ a b October 9, 1950 (day of resignation): Letter from Heinemann to Adenauer

- ^ Letter from Adenauer to Heinemann dated October 9, 1950 bundesarchiv.de

- ↑ a b c Werner Koch: Paid hooligans, bought violence. In: German General Sunday Gazette No. 27, July 6, 1986

- ↑ Dehler's speech on bundestag.de (pdf, 3 MB)

- ↑ bundestag.de: full text (pdf, 3 MB)

- ↑ Hans Prolingheuer: Small political church history. Cologne 1984, p. 150

- ↑ Bertold Klappert : Reconciliation and Liberation. Try to understand Karl Barth contextually. Neukirchener Verlag, 1994, p. 264f

- ↑ Clemens Vollnhals : Extension and "cold limitation": the limitation debate in 1969 . In: Jörg Osterloh, Clemens Vollnhals (Hrsg.): Nazi trials and the German public . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-525-36921-0 , p. 394ff.

- ↑ Nonetheless, anti-communism must remain within limits and it must not degenerate into acts of violence. In: Sendezeichen (broadcast on DLF ). April 8, 2012, accessed on April 26, 2012 (interview from April 21, 1968; also for listening as MP3).

- ↑ quoted in: Otherwise our feet will go to sleep. Judgments about the use of force . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 1968, p. 44 ( online ).

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , pp. 200-218

- ↑ Interview with Willy Brandt . In: Der Spiegel . No. 26 , 1967 ( online ).

- ↑ Solo for Schorsch . In: Der Spiegel . No. 33 , 1967 ( online ).

- ↑ FDP - wages of fear . In: Der Spiegel . No. 11 , 1969 ( online ).

- ↑ page 827 books.google

- ↑ Gustav Heinemann: Peace is an emergency. July 1, 1969, negotiations of the German Bundestag 1969, vol. 70, p. 13664ff, reprinted in Christoph Kleßmann (ed.): Two states, one nation. German history 1955–1970. Göttingen 1988, pp. 548-550.

- ^ Institutionalizations of Peace Studies . ( Memento of the original from July 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. University of Munster

- ↑ Hermann Schreiber : Nothing instead of God . In: Der Spiegel . No. 3 , 1969 ( online ).

- ↑ Jörg Treffke: Gustav Heinemann. Wanderer between the parties. A political biography. Schöningh, Paderborn 2009, p. 208 f.

- ^ Hans-Heinrich Bass: Transport policy under the pressure of the street. The Dortmund fare riots of 1971 . In: Werkstatt Geschichte , ed. from the Association for Critical Historiography e. V., No. 61: history and criticism , 2013, p. 59.

- ↑ Cf. Jubilee Colloquium 40 Years of Memorial Site bundesarchiv.de, July 28, 2014

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , p. 246

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , p. 261

- ↑ Memorial plaque on the object

- ^ Heinemann's alternative program , Süddeutsche Online, March 6, 2012

- ^ Image of the letter ( memento of October 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) on the Federal Archives website .

- ^ Illustration of the letter ( memento of October 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) on the Federal Archives website; Jörg Treffke: Gustav Heinemann. Wanderer between the parties. A political biography. Schöningh, Paderborn 2009, p. 207 f.

- ↑ Jörg Treffke: Gustav Heinemann. Wanderer between the parties. A political biography. Schöningh, Paderborn 2009, p. 208.

- ↑ Hermann Schreiber : He did not fear death . In: Der Spiegel . No. 29 , 1976 ( online - obituary).

- ↑ Helmut Gollwitzer: Obituaries . Chr. Kaiser, Munich 1977, p. 50; Günther Scholz: The Federal Presidents. Biography of an office. Bouvier, Berlin 1996, p. 260.

- ^ Diether Posser : Memories of Gustav W. Heinemann . Slightly expanded version of a lecture at an event organized by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation and the Federal Archives on February 25, 1999 in Rastatt Castle.

- ^ Helmut Lindemann: Gustav Heinemann. A life for democracy. Kösel-Verlag, 1986 (1st edition 1978), ISBN 3-466-41012-6 , p. 276

- ^ Personal decree of Gustav Heinemann in the event of death, 1972 Foundation House of the History of the Federal Republic of Germany

- ↑ List of all decorations awarded by the Federal President for services to the Republic of Austria from 1952 (PDF; 6.9 MB)

- ↑ Jean Schoos : The medals and decorations of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the former Duchy of Nassau in the past and present. Publishing house of Sankt-Paulus Druckerei AG. Luxembourg 1990. ISBN 2-87963-048-7 . P. 344.

- ↑ https://www.uni-marburg.de/aktuelles/personalia/ehrenpromotion

- ^ Gustav Gustav , Der Spiegel, January 9, 1967

- ↑ http://www.bundestag.de/blob/486422/13face838cee1c3e1029e84adb3f8e9d/05-gemeinsame-sitzung-von-bundestag-und-bundesrat-am-1--juli-1969-data.pdf

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Heinemann, Gustav |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Heinemann, Gustav Walter (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (CDU), Member of the Bundestag, Member of the Bundestag, Federal President (1969–1974) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 23, 1899 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Schwelm |

| DATE OF DEATH | 7th July 1976 |

| Place of death | eat |