Rudi Dutschke

Alfred Willi Rudolf Dutschke , nickname Rudi (born March 7, 1940 in Schönefeld near Luckenwalde ; † December 24, 1979 in Aarhus , Denmark ), was a German Marxist sociologist and political activist . He is considered the spokesman for the student movement of the 1960s in West Berlin and West Germany . In an assassination attempt on him in April 1968, he suffered severe brain injuries, of which he died in 1979.

Life

Youth and Studies

Rudi Dutschke was the youngest of four sons of the married couple Elsbeth and Alfred Dutschke, a postal worker. He spent his youth in the GDR . He was active in the Protestant young community of Luckenwalde, where he received his " religious socialist " basic character. As a competitive athlete ( decathlon ), he initially wanted to become a sports reporter. In 1956 he joined the Free German Youth (FDJ) in order to increase his chances for a corresponding training in the GDR .

Dutschke was politicized by the Hungarian uprising in 1956. He took sides for a democratic socialism that distanced itself equally from the USA and the Soviet Union , and also rejected the SED . Contrary to their anti-fascist claims, he saw the structures and mentalities of the Nazi era continue in both the East and the West.

In 1956, the GDR founded its National People's Army and promoted military service in it at high schools . Dutschke then wrote to his headmaster that as a pacifist and religious socialist he refused military service with a weapon. His mother did not give birth to her four sons for the war. Despite his belief in God and his refusal to do military service, he believed he was a good socialist. The director reprimanded Dutschke's "misunderstood pacifism" in front of a school meeting. Dutschke then quoted pacifist poems from GDR schoolbooks, which had recently been standard subject matter, and emphasized that it was not him but the school management that had changed. As a result, his overall Abitur grade in 1958 was downgraded to "satisfactory", so that he was not allowed to study immediately. Even after his apprenticeship as an industrial clerk in a Luckenwalder state-owned company, the GDR authorities refused him the desired degree in sports journalism.

In order to be able to study in West Berlin, he attended an Abitur course at the Askanisches Gymnasium in Berlin-Tempelhof from October 1960 to June 1961 . He then successfully applied as a sports reporter for the tabloid B.Z., which is published by Axel Springer AG . Articles signed by him have not survived, but his nine months' activity has been publicly mentioned by other journalists. On August 10, 1961, he moved to West Berlin, thereby fleeing the GDR . When the Berlin Wall was being built three days later , he was registered as a political refugee in protest at the Marienfelde emergency reception center . On August 14, he and some friends tried to tear down part of the wall with a rope and threw leaflets over it. This was his first political action.

Dutschke began studying sociology , ethnology , philosophy and history at the Free University of Berlin (FU) . He remained connected to the FU until his doctorate in 1973. First he studied the existentialism of Martin Heidegger , Karl Jaspers and Jean-Paul Sartre , soon also Marxism and the history of the workers' movement . He read the early writings of Karl Marx , works by the Marxist historical philosophers Georg Lukács and Ernst Bloch as well as critical theory ( Theodor W. Adorno , Max Horkheimer and Herbert Marcuse ). Encouraged by the American theology student Gretchen Klotz , he also read works by the socialist theologians Karl Barth and Paul Tillich . His earlier religious socialism turned into a well-founded Marxism. In doing so, however, he always emphasized the individual's freedom of action in relation to social conditions.

Student movement

In the fall of 1963, Dutschke and Bernd Rabehl joined the Subversive Action group , which combined social and cultural criticism with protest actions. He co-edited their magazine “ Schlag ” and wrote articles on Marx's criticism of capitalism , the situation in many countries in the “ Third World ” and new forms of political organization. The Socialist German Student Union (SDS), which has been independent since 1961 , considered the group to be “actionist” and “ anarchist ” at the time.

In February 1964, Dutschke's attack group distributed a leaflet against the student fraternities who had established themselves at the FU at the time. He became a research assistant at the Eastern European Institute of the FU and explained to guest students from Latin America in a seminar the situation of their countries of origin using basic Marxian terms. In December 1964, Dutschke's group demonstrated with the SDS and others against the state visit of the Congolese Prime Minister Moïse Tschombé . When he was piloted past the demonstrators, he spontaneously organized an unannounced “strolling” demonstration to Schöneberg Town Hall , at which Tschombé, according to the testimony of Dutschke's diary as an “imperialist agent and murderer”, was “hit in the face” with tomatoes . In retrospect, Dutschke described this action as the “beginning of our cultural revolution ”. Governing Mayor Willy Brandt received the demonstrators and subsequently approved their meeting. Dutschke explained his concept of targeted rule violations in detail in Subversive Action and suggested joining the SDS in order to radicalize it. The Munich subgroup around Dieter Kunzelmann and Frank Böckelmann rejected this. They criticized Dutschke's previous actions as “superficial” daily politics, erroneous belief in the “myth of the proletariat ” and demanded a “cultural revolutionary depth dimension”. Class struggle is generally out of date, since sooner or later all people are subject to "depersonalization" through the dictate of "economizing all of life".

From January 1965 to the end of 1966, Dutschke held a seminar on the history of social democracy with Harry Ristock , in which he sharply attacked the SPD . Despite reservations from SDS chairman Tilman Fichter , the Berlin SDS accepted the attack group in January 1965 and elected Dutschke to the political advisory board in June 1965. Because of his knowledge of Marxist theory, he was quickly recognized in the SDS and achieved that this opened up to anti-authoritarian forms of action. He brought politically interested youths and young workers who were willing to take action with him to SDS meetings, for example from the Ça Ira Club, so that the various milieus could learn from each other by arguing.

From February 1965 he organized information evenings for the SDS on the Vietnam War . In April 1965, he traveled with a SDS group in the Soviet Union, which he in the attack had analyzed as a non-socialist, anti-capitalist dictatorship, criticized the victims of the October Revolution in their own ranks and the aligned to mere productivity and performance improvement industrial policy of the CPSU . The hosts classified him as a Trotskyite .

In May 1965, the attack group issued a leaflet to protest against a US military invasion of the Dominican Republic . The fact that the SDS was deleted from the leaflet's imprint sparked debates about a lack of solidarity. Dutschke took part in protests at the FU against a ban on speaking for Erich Kuby and obtained the attorney Horst Mahler for a guest student threatened with deportation . Before the federal election in 1965 he was active against the planned emergency laws and in February 1966 founded a working group to criticize the “formed society” that Chancellor Ludwig Erhard was propagating at the time.

On February 5, 1966, the attack group pasted a poster without the knowledge of the SDS that described the US Vietnam War as genocide and promoted an international anti-colonial revolution. The West Berlin daily newspapers, which had been supporting the war with a fundraising campaign since August 1965, suspected the SDS. He showed solidarity with some imprisoned poster stickers and carried out a sit-in in front of the America House , which the police beat up with clubs. Internally, the older SDS members wanted to exclude Dutschke's group. In the following debate he successfully defended the poster campaign and thus gained influence in the SDS.

Since the Kuby affair, the Free University Rector Hans-Joachim Lieber has opposed striking students and denied them rooms for discussion events. Dutschke was his assistant and wanted to do his doctorate with a thesis on Lukács. After conflicts over the political mandate of the Berlin General Student Committee (AStA) and the students' rights to participate in university committees, which came to a head until spring 1967, Lieber did not extend Dutschke's assistant contract at the Free University of Berlin. He later initiated disciplinary proceedings against several SDS members, including Dutschke. This eliminated an academic career for this for the time being.

On March 23, 1966, Dutschke and Gretchen Klotz married at a private party in a Berlin inn. They decided to get married after a group meeting of the Subversive Action, whose patriarchal structures they rejected. In April 1966 they traveled to Hungary and visited Georg Lukács. Although he distanced himself from his early essays, Dutschke defended his position in the SDS. For the time being, the Dutschke couple stuck to plans for a political living and working community and studied community projects from the 1920s. However, they rejected Kunzelmann's concept of canceling any steady relationship as a "bourgeois principle of exchange under pseudo-revolutionary auspices" and did not move to Commune I and Commune 2, which was founded in 1967 .

In May 1966 Dutschke helped to prepare the nationwide Vietnam Congress in Frankfurt am Main . The main presentations were given by well-known professors from the New Left (Herbert Marcuse, Oskar Negt ) and the “traditionalist” Left ( Frank Deppe , Wolfgang Abendroth ). In July Dutschke was involved in an action by later Communards against the showing of the racist film Africa Addio in Berlin cinemas. In September, at the SDS delegates' conference, he called for "the organization of the permanence of the opposing university as a basis for the politicization of universities". His speech made him known beyond Berlin. Shortly afterwards he published a selected and commented bibliography on revolutionary socialism from Karl Marx to the present day, against a “training program” by Frank Deppe and Kurt Steinhaus . In this he also accepted early socialists , syndicalists and Bolsheviks (Leninists). Following Karl Korsch, he did not want them to be understood as deviating from “pure doctrine”, but rather as ambivalent answers to the respective historical changes. He encouraged the SDS to discuss issues that had mostly been suppressed in the labor movement. He obtained many of these writings on trips abroad, for example from the IISG in Amsterdam , from bookstores in Chicago and New York City . He traveled to the United States with his wife in September 1966 when their father passed away. When his bibliography was well received by the SDS, Deppe and Steinhaus resigned as training officers for the SDS federal board.

Dutschke saw the first federal German grand coalition , which was formed in November 1966 without elections, as a consequence of the SPD's drive for power since its integration into capitalism, which endangered democracy. Before the SPD left in West Berlin, he called for the formation of an extra-parliamentary opposition (APO) with quotations from Rosa Luxemburg . On December 6th, after his presentation at the FU, he asked the South Vietnamese ambassador whether he was aware of the strong support of the South Vietnamese rural population for the NLF . The media only reported that “microphone attackers” and Ho Chi Minh shouting from the audience had shouted the ambassador down. Since then, the Berlin Office for the Protection of the Constitution has been monitoring the Dutschkes and other SDS members with several informants. Dutschke was supposed to speak at two “walking demonstrations” against the Vietnam War on Kurfürstendamm on December 10th and 17th, based on the example of the Amsterdam Provo movement . On the orders of the then Interior Senator Heinrich Albertz , the police broke up the demonstrations with clubs, destroyed banners and arrested 86 people, including Rudi and Gretchen Dutschke. Press reports mentioned him for the first time as “spokesman for the SDS” or “the Beijing-friendly SDS wing” and called him from then on “ringleader” or “initiator of the riots”. On a panel discussion between Dutschke and the Trotskyist Ernest Mandel on the cultural revolution in China, Springer's BZ reported under the title: "The leader of the Berlin 'Provos' defended the goings-on of the Red Guards - Dutschke is doing a great thing". In fact, from then on he separated himself from Maoism . He also pointed out the high unemployment rate in Germany to the SDS for the first time and related it to the students' university problems.

Since spring 1967, Dutschke was with Ulrike Meinhof friend, the editor of the magazine concretely . For its June issue, he gave a long interview in which he explained the Vietnam War, the emergency laws and the Stalinist bureaucracies of the Eastern Bloc as different "links in the worldwide chain of authoritarian rule over the incapacitated peoples". The editor-in-chief Klaus Rainer Röhl classified him as a Maoist like the Springer media. Dutschke, Meinhof and the Iranian exile Bahman Nirumand informed the students with leaflets, newspaper articles and lectures about the crimes of the Persian Shah and dictator Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in order to prepare protests against his upcoming state visit. Dutschke and the Chilean Gaston Salvatore wrote a satire in the Oberbaumblatt with the title The Shah is dead - Farah desecrated , in the style of the Springer media, which warned of a possible assassination attempt on the Shah . In it they expressed understanding for an assassination attempt, but at the same time emphasized that neither in Persia nor in the Federal Republic of Germany had the necessary conditions for a successful revolution.

Dutschke was not present at the demonstration on June 2, 1967 in West Berlin , where the policeman Karl-Heinz Kurras shot the student Benno Ohnesorg . The following day he took part in a spontaneous demonstration at Schöneberg Town Hall, which the West Berlin police violently ended. In the evening, at a meeting in the FU with Klaus Meschkat , he demanded the expropriation of the publisher Axel Springer . On June 9th, after Ohnesorg's funeral, he called for nationwide sit-ins at the “University and Democracy” congress in Hanover in front of about 7,000 participants in order to clarify the circumstances of Ohnesorg's death, the resignation of those responsible, the expropriation of Springer and the “de-fascization” of the enforce West Berlin police enforced by former National Socialists. After his departure, the social philosopher Jürgen Habermas described his justification for these proposals for action as “left fascism” and thus shaped the view of many media on the '68 revolt. Dutschke, on the other hand, emphasized that targeted rule violations could prevent further murders. Only a few journalists and professors shared his point of view and showed solidarity with the protesting students, including Margherita von Brentano , Jacob Taubes , Dutschke's friend Helmut Gollwitzer , Wolfgang Abendroth, Peter Brückner and Johannes Agnoli .

In July 1967 he heard Herbert Marcuse's lectures in Berlin, adopted many of his ideas and proposed a campaign by the APO in West Berlin to counter-enlighten the Springer newspapers. With Gaston Salvatore, he translated Che Guevara's influential work Let's Get Two, Three, Many Vietnamese into German and wrote a foreword to it. From his experiences with the SPD and the trade unions, he concluded that they were “absolutely unsuitable for democratization from below”. That is why he wanted to turn the SDS into a political fighting organization. To this end, he held an “organizational lecture” at the SDS federal conference from September 4 to 8, 1967, together with the Frankfurt SDS theorist Hans-Jürgen Krahl . It met with broad approval, so that Dutschke's anti-authoritarian line prevailed throughout the SDS. He then visited the Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli , received writings from him for his dissertation and financial support for the planned expropriated Springer campaign of the SDS, the Vietnam Congress and the International News and Research Institute (INFI). At the end of September, the Dutschke couple went to Sylt for a few days with Röhl and Meinhof. On Westerland, Dutschke discussed the expropriated Springer campaign with entrepreneurs and convinced them not politically, but as a “decent person”.

Dutschke wanted to develop the "Critical University" founded in the FU on November 1, 1967, following the example of similar experiments at the University of California, Berkeley and the Sorbonne in Paris, into a "counter-university" for grassroots democratic learning. On October 21, Dutschke demonstrated with around 10,000 people against the Vietnam War, while 250,000 opponents of the war besieged the Pentagon in the USA . On November 24th, he held a discussion with Rudolf Augstein and Ralf Dahrendorf at the University of Hamburg . Three days earlier, Kurras had been acquitted of the negligent homicide of Ohnesorg, while Communard Fritz Teufel remained in custody. At the start of his criminal trial on November 28th, Dutschke called on around 1000 demonstrators to storm the courthouse unarmed, was arrested and charged as "ringleaders of an unauthorized gathering". On December 3, a long conversation between Dutschke and Günter Gaus appeared on the program “ On Protocol ” . This made him known nationwide. On Christmas Eve 1967 he suggested that some SDS members “ go-in ” to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin in order to initiate a discussion about the Vietnam War. Their banners showed a photograph of a tortured Vietnamese with the biblical quote Mt 25.40 EU . When the worshipers beat the students out of the church, Dutschke climbed into the pulpit, but was immediately prevented from speaking. Former scale-hitting fraternity and self-proclaimed "ancient Nazi" Friedrich Wilhelm Wachau added him a bloody head injury with a blow to his crutch. A policeman present said that Wachau had acted correctly.

In January 1968 Dutschke's first son was born; he was present at the birth. Hatred and attacks increased. Threatening graffiti (“Vergast Dutschke!”) Was sprayed in his hallway, smoke bombs were thrown in the entrance, and excrement was placed in front of his door. That is why the family temporarily moved into the Gollwitzer couple's house. In February 1968, the CSU member of the Bundestag, Franz Xaver Unertl, described Dutschke as an "unwashed, lousy and filthy creature".

In order to support the international protest against the Vietnam War, Dutschke founded the INFI with Gaston Salvatore and Feltrinelli's funds in February 1968. That month Feltrinelli visited the Dutschkes in Berlin and brought several sticks of dynamite with her. Dutschke smuggled the explosives out of the apartment in the pram in which his son, who was just a few weeks old, was lying. In an interview in 1978, he said that if the Vietnam War worsened, the aim was to blow up American ships that were supposed to bring war material to Vietnam. The historian Petra Terhoeven interprets this anecdote "as part of a strategy actively supported by Dutschke [...], which aimed to establish a transnational network for the implementation of militant, although explicitly not directed against people, actions".

In the same month Dutschke criticized parliamentary rituals and institutions in a dispute with Johannes Rau (SPD North Rhine-Westphalia) and called for a “united front of workers and students”.

He played a key role in preparing the International Vietnam Congress on February 17 and 18, 1968 at the TU Berlin. At the final demonstration of more than 12,000 people, he called on the participants to "smash NATO " and the US soldiers to desert on a massive scale . Originally he wanted to lead the demonstration to Berlin-Lichterfelde and occupy the McNair barracks there . Since the US military had announced the use of firearms, he gave up the plan after talks with Günter Grass , Regional Bishop Kurt Scharf and Heinrich Albertz. According to Rabehl, Dutschke worked during the congress to radicalize and internationalize the struggle, with which he wanted to eliminate the SDS leadership, which he considered too tame. Behind the scenes, the establishment of partisan units in Europe had been negotiated, in which not only German and Italian groups but also the ETA and the IRA should take part. In a "pro-America demonstration" co-organized by the Berlin Senate on February 21, 1968, participants carried posters with the inscription " People's enemy No. 1: Rudi Dutschke". A passer-by was mistaken for Dutschke, demonstrators threatened to kill him.

Following the Vietnam Congress, Dutschke traveled to Amsterdam, where he spoke out in favor of actions in the area of the port: “We cannot see the opposition to NATO as a passive observation or as a protest, but we have to act, e. B. with attacks on NATO ships. ”In March 1968 Dutschke traveled with his family to Prague and witnessed the Prague Spring . In two lectures for the Christian Peace Conference (CFK), he encouraged Czech students to combine socialism and civil rights. He justified this with the Feuerbach theses by Karl Marx. As a result, some German Orthodox Marxists demanded his exclusion from the SDS, which was rejected by a majority. Afterwards Dutschke wanted to live with his wife for one to two years in the USA and study Latin American liberation movements. He had already prepared the move. The main reason was that he had been made the identification figure of the 68 revolt and rejected this role as a contradiction to the anti-authoritarian attitude. The APO should be able to show its activity without its presence. For the 1. May 1968 he was invited as a keynote speaker to Paris, so could the protests of May 1968 in France can influence.

Assassination attempt and recovery

On April 11, 1968, the young unskilled worker Josef Bachmann shot Dutschke three times in front of the SDS office on Kurfürstendamm, shouting "You dirty communist pig!" It hit him twice in the head, once in the left shoulder. Dutschke suffered life-threatening brain injuries and only barely survived after an operation lasting several hours.

Bachmann had the Deutsche National-Zeitung with him, which showed five portrait photos of Dutschke under the headline “Stop the red Rudi now”. It was not until 2009 that it became known that, contrary to earlier reports, Bachmann had not been a lone perpetrator, but had contacts with a neo-Nazi group on record and had admitted this during his interrogations. In 1968, many students made the Springer press jointly responsible for the attack, as it had previously been harassing Dutschke and the demonstrators for months. The Bildzeitung had repeatedly portrayed Dutschke as a “ringleader” since December 1966 and on February 7, 1968, next to a photo of him entitled “Stop the terror of the young reds”, demanded that “all the dirty work of the police and their water cannons should not be allowed leave ". During the subsequent, sometimes violent “Easter riots”, some of them threw stones at the Springer publishing house in Berlin and set fire to delivery vehicles of the Bild newspaper with incendiary devices that had been distributed by the Berlin intelligence agency, Peter Urbach . They did not prevent their extradition.

Dutschke painstakingly regained language and memory in months of daily speech therapy . His friend, psychologist Thomas Ehleiter, helped him with this. The enormous media hype disrupted the learning progress, so that Dutschke left the Federal Republic with his family and married couple in June 1968. In order to recover, he initially stayed in a sanatorium in Switzerland , and from July 1968 on the composer Hans Werner Henze's estate south of Rome in Italy . Ulrike Meinhof visited him there in August 1968. Dutschke showed her his new book Letters to Rudi D. and allowed her to publish excerpts from it in detail . In the foreword he exonerated Bachmann and gave the West German media, especially “Springer and NPD newspapers”, the main culprit for the attack. He also took part in the growing conflicts in the SDS.

Because West German and Italian media discovered Dutschke's whereabouts and pressured him with requests for interviews, he fled from September 1968 to Feltrinelli's country house near Milan . Canada, the Netherlands and Belgium rejected Dutschke's visa applications. With the help of Erich Fried and the Labor MP Michael Foot , he received a temporary residence permit for Great Britain , which can be extended every six months . For this he had to give up all political activities. Despite repeated epileptic seizures, a consequence of the assassination, he learned English, reread works of critical theory and obtained admission to the doctorate. On the advice of his visitor Herbert Marcuse, he dropped the idea of subjecting himself to psychoanalysis . In May 1969 he visited the Federal Republic for the first time and spent ten days discussing the future of APO with leftists, including Ulrike Meinhof. He welcomed the fact that many left groups wanted to go their own way, but missed a common political direction and strategy. He wanted to have a say in the development, but had to take into account his health and linguistic weaknesses. After being temporarily expelled from England, he was allowed to study at the University of Cambridge in 1970 and was given a family apartment on campus. Federal President Gustav Heinemann carried the relocation costs . After the change of government in 1970 , the new British Home Secretary Reginald Maudling lifted the residence permit and limited Dutschke's legal objection to it by classifying him as a threat to “national security”. In doing so, Dutschke learned that he had been monitored by the secret service for years, that his early essays from 1968 and every contact against him on the left had been noted. Although Heinrich Albertz, Gustav Heinemann and Helmut Gollwitzer stood up for him at the immigration appellation tribunal, the Dutschke family had to leave Great Britain by the end of January 1971. She moved to Denmark , where Aarhus University hired him as a sociology lecturer .

Bachmann was sentenced to seven years in prison for attempted murder. Dutschke explained to him in several letters that he had no personal grudge against him and tried to get him involved in socialism. However, Bachmann committed on 24 February 1970 at the prison in the sixth attempt suicide . Dutschke regretted this and wrote in his diary: “He represented the domination of people who were oppressed [...] the struggle for liberation has only just begun; unfortunately Bachmann can no longer take part in it [...] ”.

Late period

From May 1972 Dutschke traveled again to the Federal Republic. He sought talks with trade unionists and social democrats, including Gustav Heinemann, whose vision of a non-aligned, demilitarized Germany as a whole he shared. In July 1972 he visited East Berlin several times and met Wolf Biermann there , with whom he remained friends from then on. He later made contact with other SED dissidents such as Robert Havemann and Rudolf Bahro . On January 14, 1973, he spoke publicly at a demonstration against the Vietnam War in Bonn for the first time since the attack.

In the same year he returned to Berlin to complete the dissertation he had begun under the title “On the Difference of the Asian and European Path to Socialism” and which he had been working on since 1971. The work was supervised by the sociologists Urs Jaeggi and Peter Furth . In the middle of 1973 Dutschke was promoted to Dr. phil. doctorate , the book was published in August 1974, slightly revised as an "attempt to get Lenin on his feet". In 1975 the German Research Foundation (DFG) gave Dutschke a scholarship at the Free University of Berlin. However, he did not complete any of his various book projects, but turned back to politics.

In February 1974 he chaired a panel discussion on Solzhenitsyn and the Left , advocating human rights in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. Since 1976 he has been a member of the Socialist Office that was created when the SDS collapsed. There he was committed to building a party that would unite green-alternative and left-wing initiatives without the K groups .

From January 1976 Dutschke made contact with opponents of nuclear power , visited Walter Mossmann and took part in large-scale demonstrations against nuclear power plants in Wyhl am Kaiserstuhl , Bonn and Brokdorf . In 1977 he worked as a freelancer for various left-wing newspapers and as a visiting professor at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands . He went on lecture tours about the student movement and took part in the Russell International Tribunal against professional bans . He began an exchange of letters with the writer Peter-Paul Zahl , visited him on October 24, 1977 in custody and arranged a joint book project with him.

After Rudolf Bahro was sentenced to eight years in prison in the GDR, Dutschke organized and led the Bahro Solidarity Congress in West Berlin in November 1978. In 1979 he joined the Bremen Green List and took part in their election campaign. After they moved into the city parliament, he was elected as a delegate for the founding congress of the Green Party planned for mid-January 1980 . In October 1979, Dutschke, as a representative of the taz, took part in a press conference by Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and the state guest Hua Guofeng from China and criticized Schmidt's authoritarian behavior: “Mr. Chancellor, you are here with the free press, not with the Bundeswehr, where there is command , not in Beijing, in Moscow or in East Berlin. ”Government spokesman Klaus Bölling then refused him the right to ask questions. Dutschke wanted to ask why Schmidt failed to mention human rights in China to the state guest and thus disregarded them.

On December 24, 1979, Dutschke suffered an epileptic attack and drowned in his bathtub. The attack was a long-term consequence of the attack and the brain surgery that followed. Other causes of death were ruled out by forensic medicine. On January 3, 1980, he was solemnly buried in the St. Anne's Churchyard in Berlin . Because there was initially no free grave site , the theologian Martin Niemöller had given him his grave site. In his speech, Helmut Gollwitzer reminded the thousands of mourners of the resistance against National Socialism that had united Niemöller and Dutschke. In 1999 the Berlin Senate declared Dutschke's grave to be an honorary burial site for the State of Berlin .

Dutschke's second son Rudi-Marek was born in Denmark in April 1980. His first son, Hosea Ché, was born in 1968, and his daughter, Polly Nicole, in 1969. Dutschke has seven grandchildren.

Think

Basic position

Since 1956 Dutschke has represented a democratic socialism that is critical of rule and since 1962 has often referred to Rosa Luxemburg's work The Russian Revolution (1918). By reading the early writings of Karl Marx and Georg Lukács (1962/63) he became a convinced Marxist and from then on distanced himself from existentialism. He considered the Marxian analysis of capitalism in the 19th century for large parts of Europe, Latin America and Asia still correct, but not the Marxian prognosis of a growing proletarian class consciousness . This is lacking in countries with a higher standard of living and does not develop by itself.

He affirmed a critical historical materialism , but rejected any determinism of historical development. Regardless of their objective tendencies, the critical materialist must always stand on the side of a revolutionary resistance that liberates concrete people. As a result, he constantly sought connection to forgotten traditions of the labor movement and other resistance movements that were critical of rule. He rejected reformism , Stalinism and Marxism-Leninism as “legitimation Marxism ”, which justifies existing conditions of oppression as unchangeable. He also represented this criticism against reform communists of the time such as Georg Lukács, Wolf Biermann and Robert Havemann.

He stayed true to his Christian beginnings. On April 14, 1963 ( Easter ) in his diary he described the resurrection of Jesus Christ as a “decisive revolution in world history” through “love which conquers everything”. On March 27, 1964 ( Good Friday ) he wrote about “the world's greatest revolutionary”: “ Jesus Christ shows all people a path to self. For me, however, this gaining of inner freedom is inseparable from gaining a maximum degree of outer freedom, which wants to be fought equally and perhaps even more. ”He could read Jesus' statement 'My kingdom is not of this world' ( Jn 18:36 LUT ) only to be understood as a statement about the still to be created, this worldly new reality, "a Hic-et-Nunc task of humanity". In 1978 he emphasized in retrospect: “In this respect, until I left the GDR, I never got to know Christianity as a state church, never as a ruling opium . It was always about not letting the love and hope for better times go under. ”In the same year, at a meeting with Martin Niemöller, he confessed himself to be a “ socialist who stands in the Christian tradition ”, and he is proud of this tradition. He sees Christianity "as a specific expression of the hopes and dreams of mankind".

At the Ohnesorg Congress on June 9, 1967, Dutschke declared the "abolition of hunger, war and domination" through a " world revolution " to be a political goal that was currently "materially possible" through the development of the productive forces. That is why he distinguished himself from any anti-action, purely analytical-theoretical understanding of Marxism. In December 1967, he named the mainspring of his political action “that people really live together as brothers”. For him, the decisive components of this coexistence were “self-activity, self-organization, development of initiative and the awareness of people and not a principle of leadership ”. His basic position is therefore called "anti-authoritarian socialism" or "libertarian communism ".

Economic analysis

Dutschke tried to apply Marx's critique of political economy to the present and to develop it further. He saw the economic and social system of the Federal Republic as part of a worldwide complex capitalism that pervades all areas of life and suppresses the wage-dependent population. The social market economy does indeed share the proletariat in the relative prosperity of the advanced industrial countries, but thereby ties it into capitalism and deceives it about the actual balance of power.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, Dutschke expected a period of stagnation after the economic miracle : it would no longer be possible to finance subsidies for unproductive sectors such as agriculture and mining. The foreseeable massive reduction in jobs in late capitalism will create a structural crisis that will cause the state to intervene ever deeper in the economy and result in an "integral statism ". This situation can only be stabilized with violence against the rebellious victims of the structural crisis. He adopted the term statism for a state that directs the economy but formally maintains private property from an analysis by Max Horkheimer in 1939.

Like the entire SDS, Dutschke affirmed technical progress , especially nuclear energy , as a process of scientification that would enable a “revolution of the productive forces” and thus a fundamental change in society. The automation of production will reduce the division of labor and specialization, shorten working hours and thus allow industrial workers more and more self-development and extensive learning in a council democracy.

However, the Federal Republic lacks a “revolutionary subject” for the necessary overthrow. Following Herbert Marcuse ( The One-Dimensional Man ), Dutschke and Krahl stated in the organizational unit in 1967: A “gigantic system of manipulation” defused the social and political contradictions and made the masses incapable of revolting themselves. The German proletarians lived so blinded in monopoly capitalism that “the self-organization of their interests, needs and desires has historically become impossible”.

Like many of his colleagues in the SDS looked Dutschke the Vietnam War, the US, the emergency laws in Germany and the Stalinist bureaucracies in the Soviet bloc as "members of the global chain of authoritarian rule over the incapacitated people" (as in concrete interview of June 1967). However, the conditions for overcoming global capitalism are different in the rich industrial countries and in the “third world”. Contrary to what Marx expected, the revolution will come from the impoverished and oppressed peoples of the “periphery” of the world market , not from highly industrialized Central Europe. There the relative prosperity and the welfare state prevent the proletariat from developing a revolutionary consciousness. The prerequisite for this, however, is that the countries of the third world are degraded to suppliers of cheap raw materials and buyers of expensive finished goods. Dutschke therefore hoped for revolutionary movements in Latin America and Africa that would also lead to changes in the rich West. This connection was emphasized by the poster of the attack group from February 1966. Under the heading “Americans out of Vietnam! International Liberation Front ”it said:“ Cuba, Congo, Vietnam - the capitalists' answer is war. The old rule is maintained by force of arms. The economy is secured with a war economy ”.

Relationship to parliamentarianism

Dutschke represented an ethical and moral anti-fascism since his school days in the GDR . In his Abitur essay from 1961 on Article 21 of the Basic Law , he wrote that the Allies and the West German parties had missed the historic opportunity to “educate Germans to be democratic”. Most of the Nazi criminals and their followers were quickly freed from the necessary profound turning away from fascism and their final line mentality was confirmed. The real democratization of Germany is still pending. Only individual political responsibility and self-education can realize real freedom.

In the 1960s he rejected representative democracy because he did not see the Bundestag as a functioning representative body . In 1967 he explained this: “I consider the existing parliamentary system to be unusable. In other words, we have no representatives in our Parliament who express the interests of our people - the real interests of our people. You can now ask: What are your real interests? But there are demands. Even in parliament. The right to reunification, safeguarding jobs, safeguarding state finances, the economy that needs to be put in order, these are all claims that Parliament must realize. But it can only achieve this if it establishes a critical dialogue with the population. But now there is a total separation between the representatives in parliament and the people who are considered to be minors. "

The parliamentary system was for Dutschke expression of a " repressive tolerance " (Herbert Marcuse), the exploitation conceals the workers and protect the privileges of the wealthy. He saw these structures as not reformable; rather, they would have to be overturned in a protracted, internationally differentiated revolutionary process that he described as the “ march through the institutions ”. In order to overcome the alienation between the rulers and the ruled, he designed the model of a “ Soviet Republic in West Berlin” and presented it in a “Conversation about the future” in October 1967 in the course book. As in the Paris Commune , collectives of no more than three thousand people should be formed on the basis of self-governing companies in order to regulate their affairs holistically in a non-dominant discourse, with a rotation principle and an imperative mandate . The police, the judiciary and prisons, Semler hoped, would then become superfluous. You will only have to work five hours a day. After taking over political power in the whole of Berlin, the council republic was to be built, the wall removed, and "life centers" and "council schools" set up to set a learning process in motion through all areas of production. School, university and factory were supposed to merge as an “association of free individuals” (Karl Marx) into a single productive unit. Dutschke later commented on this plan with the words “What an illusion!”, But left it open as to whether he considered it to be impossible in principle or under the circumstances at the time. He found some aspects of his plan implemented through later citizens' initiatives and new social movements .

For Dutschke, fascism continued to have an effect in his presence. In his speech to the Vietnam Congress on February 18, 1968, he said: “Today's fascism is no longer manifested in a party or in a person, it lies in the day-to-day training of people to become authoritarian personalities , it lies in education, in short in the resulting totality of institutions and the state apparatus. ”From Erich Fromm's and Adorno's studies on the authoritarian personality, he concluded:“ Even the outward defeat of fascism in Germany did not overcome this personality foundation of fascism, but could rather be transformed essentially uninterrupted into anti-communism . “His concept of action was therefore decisively aimed at“ destroying the authoritarian structure of the bourgeois character in ourselves, building moments of ego strength, the conviction that we can overthrow the system as a whole in the future. ”Politics without this self-change is“ manipulation of elites ”. In 1974 Dutschke looked back on the earlier APO actions as effective and said that after the Vietnam Congress "the climax of the fascist tendency would soon be removed".

Before and after the attack, Dutschke demarcated himself from almost all existing parties and was constantly looking for new, directly effective forms of action. He found kindred spirits with some Italian Eurocommunists and considered the establishment of a new Left Party early on. But his skepticism against an independent “revisionist” party elite prevailed. Since 1976, Dutschke has been committed to building an eco-socialist party that would bundle the new extra-parliamentary movements and make them effective in parliament. From 1978 he campaigned with others for a green alternative list that should take part in the upcoming European elections. In June 1979 Joseph Beuys won him over for joint campaign appearances. With his entry into the Bremen Green List , which was the first green state association to cross the five percent hurdle , he finally turned to parliamentarianism. At the program congress of the Greens in Offenbach am Main , in connection with the " German Question ", he advocated the right of nations to self-determination and thus a right of resistance against the military blocs in West and East. Nobody else raised this issue because it contradicted the majority position of strict nonviolence and strict pacifism .

Relationship to real socialism

For Dutschke, democracy and socialism have been inseparable since his youth. That is why he expressed solidarity with the uprising of June 17, 1953 and the Hungarian people's uprising in 1956. Since then he has deliberately demarcated himself from Soviet Marxism-Leninism and emphasized in one of his first attack articles: "There is still no socialism on earth" that this must first be socially realized on a global scale.

As Rosa Luxembourg criticized it Lenin's discussion and group bans within the Bolsheviks and wanted with the disposal of the workers over the means of production , the citizens' rights to preserve, "Rosa Luxembourg insisted on the heritage of the bourgeois revolution , the, to allow proletarian democracy." Communist International represented for him a doctrinal “legitimation Marxism”, which every critical Marxist must criticize as an expression of old and new class relations. That is why, when the SDS visited Moscow in the summer of 1965, he asked about the Kronstadt sailors' uprising in 1921. He saw its violent suppression as Lenin's turning away from genuine Marxism to a new “bureaucratic” form of rule.

Since 1965, he has been intensively involved in the SDS with supporters of the GDR and “traditionalists” and their understanding of the revolution, which is based on Lenin's concept of a cadre party . A spy in the SDS then reported to the East Berlin Ministry for State Security that Dutschke represented “a completely anarchist position”. The IM Dietrich Staritz reported in December 1966: "Dutschke only speaks of shitty socialism in the GDR."

After an initial interest in the Chinese cultural revolution, from which he hoped to reduce the bureaucracy and overcome the “ Asian mode of production ”, Dutschke took over Ernest Mandel's criticism in December 1966: “' Mao does not allow the masses to act independently ' - a damn critical remark. “Since June 17, 1967, in a discussion in the Republican Club West Berlin in the Eastern Bloc , he has been calling for a“ second revolution ”towards a socialism of freely socializing individuals. The "third front" in the international liberation struggle remained for him the Viet Cong in Vietnam and the liberation movements of Latin America, which were based on Che Guevara.

He welcomed the popular reform communist course of Alexander Dubček in the Prague Spring without reservation. During his visit to Prague on April 4, 1968, despite the ban on speaking, he demanded an “international opposition [...] against all forms of authoritarian structures” and continued: “I think that there is a great task in Czechoslovakia: to find new ways to achieve socialism to combine real individual freedom and democracy, not in the bourgeois sense, but in a real social-revolutionary sense. We do not want to abolish bourgeois democracy, but we really want to fill it with new content. ”He specified this the following day at a lecture at Charles University as“ producer democracy for those affected in all areas of life ”.

After the Warsaw Pact troops marched into Czechoslovakia in August 1968, Dutschke self-criticized the previous cooperation between the SDS and the FDJ against the Vietnam War: “Have we even succumbed to huge fraud and self-deception? [...] Why does an SU (without soviets ) that supports social revolutionary movements in the Third World act imperialistically against a people which independently took the democratic-socialist initiative under the leadership of the communist party? [...] Without clarity on this corner, a socialist standpoint of concrete truth, credibility and authenticity is impossible, especially the oppressed, exploited and offended in the FRG and the GDR in particular will not be ready to join the political class struggle beyond wage wars. "

In his dissertation (published 1974) he explained the causes of the Soviet-Chinese undesirable development in the wake of Karl August Wittfogel with the Marxist analysis of society. The prerequisites for a socialist revolution never existed in Russia: there was no feudalist and capitalist, but rather an "Asian" mode of production. This inevitably led to an “Asian despotism ” that continued unbroken from Genghis Khan to Josef Stalin's forced collectivization and industrialization . While Lenin pleaded for the development of capitalism in Russia in 1905 so that a real working class could grow up there, the " Bolsheviks' seizure of power" in the "October coup" of 1917 should be seen as a relapse into "general state slavery". The educational dictatorship of the Bolsheviks was then inevitably followed in order to bring socialism closer to the backward population. The development of Lenin's ban on parties and factions through this educational dictatorship to Stalin was logical. Stalin's brutal forced industrialization in order to increase productivity could never remove the dependence of the Soviet Union on the capitalist world market, but only produced a new imperialism . Military support for liberation movements in the Third World and the suppression of self-determined attempts at socialism in the Eastern Bloc were therefore a logical unit. The Soviet Union could not be a model for the western left, as it was the result of completely different socio-economic conditions. Stalinism is manifest “anti-communism”, which has created a “monopoly bureaucracy” that is no less aggressive than the “monopoly bourgeoisie” that Stalin made responsible for German fascism. It is therefore no coincidence that his gulags and concentration camps were maintained after 1945. Leon Trotsky , Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin , Karl Korsch, Rudolf Bahro, Jürgen Habermas and other Marxist critics and analysts did not fully recognize this system-related character of the Soviet Union, which cannot be understood as a “degeneracy” of Lenin's policy . The isolated “ socialism in one country ” is an “anti-dynamic cul-de-sac formation” that can only be kept alive through loans and imports from the West. All of their apparent attempts at internal reform since Nikita Sergejewitsch Khrushchev and the XX. The party congress of the CPSU in 1956 was only a means to the survival of the Central Committee bureaucracy: “From a pseudo-left, well-intentioned moral-romantic position one can approve of 'skipping over' modes of production, with a socialist point of view one had (and still has) the Moscow position just like the Beijingers never do anything. "

Because of this clear stance, Dutschke was considered by the GDR State Security until 1990 to be the author of the “Manifesto of the Federation of Democratic Communists”, which the magazine Der Spiegel published in January 1978. Like his dissertation, it called for the transition from the Asian mode of production of bureaucratic “ state capitalism ” to a socialist economy, from one-party dictatorship to party pluralism and the separation of powers . It wasn't until 1998 that Hermann von Berg , a Leipzig SED dissident, emerged as an author.

The DKP , founded in 1968 , its representative Robert Steigerwald and its magazine Our Time always gave Dutschke's dissertation, his Solzhenitsyn book and other texts on the Soviet Union and GDR negative reviews, calling him an “anti-communist” and a “useful idiot in the ideological strategy of the big bourgeoisie ". Since the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia (August 21, 1968), Dutschke, in turn, ruled out any cooperation between the SDS and the DKP, the SED and its offshoot SEW . He viewed the founding of the DKP as an attempt to reintegrate the anti-authoritarian left into the reformist camp because it had become too dangerous for the system. He also distanced himself from the K-groups that emerged from 1968 and that leaned uncritically to the People's Republic of China or Albania . Since his participation in the environmental and anti-nuclear power movement (from 1978), he has campaigned for their sharp demarcation from the K groups. At the same time, he called for a clarification process on the relationship between ecology and economy, democracy and socialism.

Anti-imperialist violence and anti-authoritarian provocation

In the military guerrilla struggle of the Viet Cong, Dutschke saw the beginning of a worldwide revolutionary development that could spill over to other Third World countries. In the foreword to his translation of Che Guevara's work Let's create two, three, many Vietnamese, he affirmed military counterviolence on the part of the Viet Cong: “This revolutionary war is terrible, but the suffering of the peoples would be more terrible, if not the war itself because of the armed struggle is abolished by the people. ”Here he shared the anti-imperialist theory of Frantz Fanon following Lenin, according to which the liberation struggle of the peoples led by“ revolutionary hatred ”will first tear the“ weakest links ”in the chain of imperialism and this must be supported . He differentiated “liberating” from “suppressing” violence, justified the former in the context of national liberation struggles in the third world and emphasized: “Full identification with the necessity of revolutionary terrorism and the revolutionary struggle in the third world is an indispensable condition for [...] the development of forms of resistance among us. "

From Che Guevara's book The Partisan War, Dutschke took the assumption in 1966 that a revolution does not necessarily depend on an economic crisis and a class-conscious proletariat, but that subjective activity can also create the “objective conditions for the revolution”. For the Federal Republic, Dutschke did not reject violent guerrilla warfare in principle, but in the given situation.

Since 1965, his concept of action had been aimed at “subversive”, “anti-authoritarian” and also illegal rule violations in order to allow the public to experience and perceive oppression and criticism of the system at all: “It was through systematic, controlled and limited confrontation with state power and the Imperialism in West Berlin to force representative 'democracy' to openly show its class character, its character of rule, to force it to expose itself as the 'dictatorship of violence' ”. “The established rules of the game of this unreasonable democracy cannot be our rules of the game.” “Approved demonstrations must be made illegal. The confrontation with the state authority is to be sought and absolutely necessary. ”The rule violations of the anti-authoritarian protest should expose, expose the violence, on which the bourgeois society in Dutschke's opinion was based, make it sensually tangible and thus educate broadly about it.

Benno Ohnesorg's shooting and the reaction of the state to the protests made Dutschke's concept of action plausible. He wanted to use the aggravated situation to bring about a successful revolution, the objective conditions of which in his opinion existed: “Everything depends on the conscious will of the people to finally make the history they have always made conscious, to control them, to submit to them . ”Jürgen Habermas, on the other hand, criticized the fact that“ transforming sublime violence into manifest violence ”, which is inherent in society, is downright masochism and ultimately means“ submission to precisely this violence. ”To make the revolution dependent only on the determination of the revolutionaries, instead of like Marx Setting the self-development of the relations of production is a " voluntaristic ideology " which he calls "left fascism". Dutschke's plans will arouse fascist tendencies in the state and the people instead of reducing them. He believed, however, “that only careful actions can 'avoid' the dead, both for the present and even more so for the future. Organized counter-violence on our part is the greatest protection, not 'organized balancing-out' a la H [abermas]. "

In an interview in July 1967, he gave examples of the required " direct action ": Support striking workers through solidarity strikes and information about their objective role, for example in arms factories that supplied the US Army, preventing the distribution of Springer newspapers, combined with an expropriation campaign, Establishing a counter-university for comprehensive education of the population: about conflicts in the Third World and their connection with internal German problems as well as legal issues, medicine, sexuality etc. He did not consider throwing eggs, tomatoes and stones to be an effective protest, he refused but following Mario Savio (student leader at Berkeley ) also did not turn off.

In their “organizational presentation” (September 5, 1967) Dutschke and Krahl declared: Only revolutionary groups of consciousness could enlighten the passively suffering masses and turn the abstract violence of the system into a sensual certainty through visibly irregular actions. They referred to Che Guevara's focus theory : “The 'propaganda of gunfire' (Che Guevara) in the 'Third World' must be completed by ' propaganda of deed ' in the metropolises, which historically makes urbanization of rural guerrilla activity possible . The urban guerrilla is the organizer of utter irregularity as a destruction of the system of repressive institutions. "

In 1968 Dutschke named further goals of the action: “Breaking the rules of the game of the ruling capitalist order will only lead to the manifest exposure of the system as the 'dictatorship of violence' if we attack the central nerve points of the system in various forms (from non-violent open demonstrations to conspiratorial forms of action) (Parliament, tax offices, courthouses, manipulation centers such as Springer high-rise or SFB , America House, embassies of the oppressed nations, army centers, police stations, etc.). "

Dutschke distinguished between violence against things and violence against people; The latter he did not reject in principle, but for the German situation. He was also not actively involved in violence against property, although he helped to prepare explosive attacks on a transmission mast for the American Forces Network or a ship with supplies for the US Army in Vietnam. Both attacks were not carried out. He also emphasized: "We have a fundamental difference in the application of the methods in the Third World and in the metropolises."

But he also considered a situation in Germany possible that required armed counter-violence, for example when the Bundeswehr took part in NATO operations against Third World revolutions. In the foreword to his Che Guevara translation, he already pointed out the danger: The problem of revolutionary violence is "the transition from revolutionary violence to violence that supports the goals of violence - the emancipation of man, the creation of the new man - forgets". When Günter Gaus asked (December 1967) whether he would fight with gun in hand if necessary, he replied: “If I were in Latin America, I would fight with gun in hand. I'm not in Latin America, I'm in Germany. We fight to ensure that weapons never have to be picked up. But that's not up to us. We are not in power. The people are not aware of their own fate, and so if in 1969 the exit from NATO does not take place, if we get into the process of the international dispute - it is certain that we will then use weapons if Federal Republican troops in Vietnam or fight in Bolivia or elsewhere - that we will then also fight in our own country. ”In further interviews around the turn of the year 1967/68, Dutschke answered the question of whether he refused to throw tomatoes and stones clearly“ No ”and added:“ But they The level of our counterviolence is determined by the extent of the repressive violence of the rulers. We say yes to the actions of the anti-authoritarians because they represent a permanent learning process for those involved in the action. "

At the Vietnam Congress in February 1968 he therefore demanded intensified, targeted and illegal actions in support of the Viet Cong. He linked his military struggle in the Tet offensive at the time with the struggle of the SDS and APO against authoritarian social structures: "In Vietnam we too are smashed every day [...] If the Viet Cong is not an American, European and Asian Joined Cong, the Vietnamese revolution will fail just as much as others before it. A hierarchical functionary state will reap the fruits that it has not sown. [...] “But he did not demand an armed guerrilla fight in the Federal Republic, but a nationwide appeal to Bundeswehr soldiers to desert, in order to“ break with our own apparatus of rule. ”He himself publicly called US soldiers stationed in the Federal Republic and with them Barracks fences flung up leaflets into massive desertion; he proposed these calls in 1967. They have been adopted by the SDS since January 1968, and later also by the youth union and some university lecturers.

In the foreword to the letters to Rudi D. (summer 1968) Dutschke wrote about the “Easter riots” of April 1968: Spontaneous, direct actions against the Springer concern were insufficient. Only a few trucks were destroyed, but “the machinery of lies and threats” could not be stopped. The 'state of law and order' quickly caught the “completely unexpected, deeply human anger against this machine”. Neither suitable organizations nor suitable weapons were available in time. “ Molotov cocktails came too late.” A “ridiculous discussion of violence” followed: “The phrase non-violence is always the integration of the dispute. [...] Our alternative to the ruling violence is increasing counter-violence. Or should we let ourselves be ruined all the time? No, the oppressed in the underdeveloped countries of Asia, Latin America and Africa have already started their struggle. ”But he also emphasized:“ In the metropolises we do not fight individual character masks by shooting them; it would be counter-revolutionary in my opinion. The system will of course want something like that in order to be able to crush us harder, completely for years. ”For the Shah of Persia, however, he later wanted an exception: that the revolutionaries of the metropolises would not have used the Shah's visit to Europe to shoot him , show "the lack of level of our struggle so far". In order to become revolutionary, the APO supporters would have to leave the universities and go to the institutions in order to “break them open” and repeatedly penetrate them as “permanent revolutionaries”. He called this a "revolutionary global strategy in the anti-authoritarian sense". Its controlled, violent militancy was later reinterpreted as a “march through the institutions”.

In 1971 Dutschke declared self-critically that the revolutionary situation he and some others assumed at the time was an illusion. In 1977, after the murder of Elisabeth Käsemann , who had visited Prague with him in 1968, he defended her participation in the armed struggle against the military junta in Argentina. He recalled that the junta had abrogated all civil rights and attacked the left opposition "by all means of military terror", leaving the persecuted with only armed resistance.

Relationship to terrorism

Dutschke also affirmed terror in the fight against imperialism, but differentiated between “necessary and additional terror” since 1964. The former is legitimate in revolutionary situations, since the bourgeois capitalist state also uses terrorism of convictions and physical terror to maintain its order. In his foreword to Che Guevara's work Let 's Create Two, Three, Many Vietnamese , he explained that hatred of any form of oppression was on the one hand militant humanism and on the other hand endangered by turning into “independent terror”. Like all “cadre” concepts that isolated themselves from the population and prevented them from becoming aware, Dutschke, as an anti-authoritarian Marxist, also rejected the individual terror that some left-wing radical groups such as the “ Tupamaros West Berlin ” or the Red Army faction had been following since 1970 committed the disintegration of the SDS.

At the funeral of RAF member Holger Meins on November 9, 1974, Dutschke shouted with a raised fist: “Holger, the fight continues!” After the murder of Günter von Drenkmann , he replied in a letter to the editor: “'Holger 'The struggle goes on' - for me this means that the struggle of the exploited and offended for their social liberation constitutes the sole basis of our political action as revolutionary socialists and communists. […] The political fight against solitary confinement has a clear meaning, hence our solidarity. The murder of an anti-fascist and social democratic chamber president is to be understood as a murder in the reactionary German tradition. The class struggle is a political learning process. But the terror hinders any learning process of the oppressed and insulted. ”In a letter to Freimut Duve (SPD) of February 1, 1975, Dutschke declared his appearance at Meins' grave as“ psychologically understandable ”, but politically“ not adequately reflected ”. He visited the RAF member Jan-Carl Raspe immediately after Meins' funeral in prison and then expected the RAF to destroy itself as a result of its "wrong conception" and solitary confinement.

On April 7, 1977 Federal Prosecutor General Siegfried Buback was murdered. Dutschke now saw a party to the left of the SPD as a necessary prevention against left-wing terrorism: “The break in left continuity in the SDS, the fateful effects are becoming apparent. What to do? The socialist party is becoming more and more essential! "

In the German autumn of 1977, many left-wing intellectuals were accused of having created the “intellectual breeding ground” for the RAF. In the period from 16 September Dutschke gave this charge to the "ruling party" back and questioned it at all still go to socialist goals of the RAF: "For in their arguments and discussions, as far as they ever see through from the outside and be seen the question of the emancipation of the oppressed and offended has long ceased to exist. Individual terror is terror that later leads to individual despotic rule, but not to socialism. That was not our goal and it never will be. We know only too well what the despotism of capital is, we do not want to replace it with terror despotism. ”Nevertheless, the Stuttgart newspaper attacked him personally the following day as a pioneer of the RAF, who had demanded“ the concept of urban guerrilla must be developed in this country and the War can be unleashed in the imperialist metropolises. ”In contrast, Dutschke declared in 1978 that the RAF had arisen after the attacks on Ohnesorg and himself from the social“ climate of inhumanity ”that right-wing politicians and the Springer media had stirred up. Looking back on his development in December 1978, he emphasized again: “But individual terror is anti-mass and anti-humanist. Every small citizens' initiative, every political and social youth, women, unemployed, pensioner and class struggle movement in the social movement is a hundred times more valuable and qualitatively different than the most spectacular action of individual terror. "

Relationship to the German nation

The division of Germany was an anachronism for Dutschke since his youth in the GDR : “Fascism is gone, why is Germany now also divided?” In 1957, he justified his refusal to do military service in the National People's Army by saying that he would not wanted to shoot at compatriots. In 1968 he declared: “I committed to reunification , I recognized socialism as it was practiced, and spoke out against joining the National People's Army. I was not ready to serve in an army that might have the duty to shoot another German army, in a civil war army, in two German states, without real independence on both sides, I refused. "

After the demand for a socialist revolution in the Eastern Bloc on June 17, 1967, Dutschke presented his plan for a council revolution in West Berlin on June 24, initially in his closest circle of friends, from July in the "Oberbaumblatt" in an edition of 30,000 copies to the GDR and thus end the division of Germany in the long term: "A West Berlin supported from below by direct council democracy [...] could be a strategic transmission belt for a future reunification of Germany." In October 1967 he deepened this idea of a reunification among socialists Signs in a conversation: “If West Berlin were to develop into a new community, the GDR would face a decision: either hardening or real liberation of the socialist tendencies in the GDR. I tend to assume the latter. "

After that, this topic took a back seat in his utterances. It was not until 1977 that he took it up again with a series of articles and asked why the German left did not think nationally. He called for cooperation between the respective socialist opposition in the GDR and the Federal Republic, because “the GDR is not the better Germany. But it is part of Germany ”. In order to interest the West German left in the “national question” it neglected and not to leave the treatment of this topic to the nationalists, he referred to the dialectical connection with the social question emphasized by Karl Marx himself: “The left German starts under such conditions to identify with everything possible, but to ignore a basic feature of the communist manifesto : the class struggle is international, but national in its form. ”At the time, however, these views met with almost unanimous rejection and sometimes outrage.

reception

Obituaries

After Rudi Dutschke's death, a large number of positive obituaries appeared . In his funeral speech, Helmut Gollwitzer recalled Dutschke's last phone call on the evening of his death. The caller Heinz Brandt reminded him of his beginnings with the Christian community in Luckenwalde: "Rudi, you never left what you started from, your beginnings with the young community in the GDR and with the conscientious objection ..." Dutschke agreed. He did not want to be "leader, chief ideologist, authority", but belonged to the revolutionaries who "have not grown old on this earth".

Jürgen Habermas described Dutschke as a “true socialist”. He is "... the charismatic of an intellectual movement, the tireless inspirer, a gorgeous rhetor who has combined with the power to be a visionary a sense for the concrete, for what a situation has to offer."

Wolf Biermann sang in his funeral song on January 3, 1980, referring to personal encounters: “My friend is dead and I am too sad to paint large paintings - he was gentle, gentle, a little too gentle like all real radicals. “From then on, this image determined the perception of Dutschke among many contemporaries. Walter Jens said in 1981 that he was "a peace-loving, deeply Jesuan person".

For Ulrich Chaussy , the “construction of a myth” began during Dutschke's lifetime. He tried to resist his idolization and announced his withdrawal from the student movement only days before the attack on him for a planned television film by Wolfgang Venohr in order to counteract the personalization of social conflicts. Chaussy explains the failure of this intention as follows: “Almost all former comrades felt guilty because Rudi's death, because the bullets in his head had so much to represent, because everyone felt that everyone who revolted in this revolt was meant. [...] That just happens to the early dead, to the pop stars and the revolutionaries, including Rudi Dutschke. You can no longer interfere yourself. "

memory

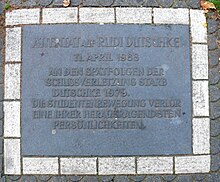

On December 23, 1990, a stone tablet set into the sidewalk was unveiled in front of the former SDS office at 141 Kurfürstendamm, the site of the attack.

On April 30, 2008, part of Kochstrasse in Berlin was officially renamed Rudi-Dutschke-Strasse . It borders directly on Axel-Springer-Straße. The 2005 renaming proposal sparked years of public conflict. Several lawsuits from residents and the Axel Springer Verlag based in Kochstrasse were dismissed. On March 7, 2008, Dutschke's 68th birthday, the forecourt of the disused train station in his place of birth Schönefeld (Nuthe-Urstromtal) was renamed “Rudi-Dutschke-Platz”. A "Rudi-Dutschke-Weg" runs on the campus of the FU Berlin.

Several documentary films dealt with Rudi Dutschke , for example the work of the director Helga Reidemeister from 1988 Going upright, Rudi Dutschke - Traces or the film Dutschke, Rudi, Rebel by his biographer Jürgen Miermeister, which was broadcast on ZDF in April 1998 . Rainer Werner Fassbinder's feature film The Third Generation from 1979 uses archive recordings in which Dutschke can be seen. In the 2008 feature film Der Baader Meinhof Complex by director Uli Edel , Dutschke is portrayed by Sebastian Blomberg . The docu-drama Dutschke (2009) by Stefan Krohmer and Daniel Nocke combines interview passages and staged scenes from Dutschke's life. Christoph Bach was awarded the German TV Prize for Best Actor in 2010 .

Wolf Biermann published the song Three Balls on Rudi Dutschke in 1968 . In 1969 it appeared in his volume of poetry With Marx and Engels Tongues. Thees Uhlmann celebrates the birth of Rudi Dutschke and the naming of the street in his song On March 7th (2013).

In 1967 the picture Dutschke by Wolf Vostell was created , a blurring of a photograph by Rudi Dutschke. The picture is part of the art collection in the House of History .

Dutschke's image changed with the image of the 1968 revolt as a whole. In 2008, on the 40th anniversary of the “68ers”, the former APO activist Götz Aly compared him to Joseph Goebbels in a newspaper article on January 30, 2008 on the anniversary of the National Socialist seizure of power . A photograph printed on this compared the APO's fight against the Springer concern with the book burnings of the National Socialists; other photographs compared a university rally by Nazi students with an anti-war demonstration cited by Dutschke. The caption claimed "similar goals".

Discourse on the question of violence

Dutschke's relationship to revolutionary violence and its possible influence on the terrorism of the RAF have been the subject of intense discussion since the 1970s.

In 1986 Jürgen Miermeister used Dutschke's testimonies to show that he reflected on every form of action and linked it to a political analysis of the situation. In theory, he also considered assassinations of tyrants to be legitimate, but only as a direct trigger for a people's revolution. Because of this lack of prerequisites, he had rejected plans to attack dictators as well as terror for the Federal Republic. He was "not a pacifist, but ultimately neither anarchist nor a putschist Marxist-Leninist, but a Christian" and therefore shied away from violence against people.

In 1987, Wolfgang Kraushaar also documented Dutschke's and Krahl's “Organizational Report” from 1967 in his three-volume chronicle of the West German student movement. He emphasized: “Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to speak of an intellectual anticipation of the Red Army Faction (RAF) in retrospect. Not only because it would be wrong in a concrete historical sense, but also because there is an unmistakable qualitative difference between the appeal of autumn 1967 and the practice of the RAF. Urban guerrilla is still defined by Dutschke and Krahl as an element of an awareness strategy. The status of militancy results from its propagandistic function, not the other way around. "

In her biography, published in 1996, Gretchen Dutschke-Klotz also presented Dutschke's contradicting stance on armed violence: “At the beginning of 1969, Rudi was also prepared to go underground if the conditions were right. [...] The illegality seemed necessary to Rudi, if it were to succeed at all in building new structures in the ruling system. But it was an unsolved question of what this illegality should look like. Rudi did not succeed in clearly separating legitimate forms of violence from illegitimate ones. ”At the time, he did not contradict plans to attack a British airline with Molotov cocktails, only refused to participate. It was clear to him that illegal resistance should not isolate people from the population and should not endanger people.

Dutschke's diaries published by Gretchen Dutschke-Klotz in 2003 enabled new insights into his political development. Michaela Karl traced Dutschke's changed relationship to revolutionary violence in different phases of life and explained it from the respective historical context. In 2004, Rudolf Sievers published Dutschke's article The historical conditions for the international struggle for emancipation, in which the latter also discussed the role of revolutionary counter-violence.

In his 2001 study Mythos '68, Gerd Langguth held Dutschke responsible for a theoretical and practical “taboo removal” of violence in the Federal Republic that led to the RAF. Wolfgang Kraushaar sharpened Langguth's thesis in 2005 in his essay Rudi Dutschke and the armed struggle . He criticized that contemporaries had portrayed Dutschke as an “icon” and “Christian pacifist with a green tinge”. In view of previously unpublished statements by Dutschke in his estate, this is untenable. He was the "inventor of the urban guerrilla concept in Germany", consistently represented it until 1969 and helped prepare explosive attacks, although these remained unexecuted and he distanced himself from later RAF terrorism.

This sparked another discussion. Thomas Medicus concluded "that Dutschke propagated what Baader and the RAF practiced". Lorenz Jäger welcomed the fact that Kraushaar's essay had above all questioned Erich Fried's “Dutschke legend” of a “pacifist revolutionary” who would have kept Ulrike Meinhof from becoming illegally in the event of prolonged contact. Dutschke was ready to use violence even before the student movement began. His "explosive episodes" were the expression and consequence of his action plan.

According to Jürgen Treulieb , Dutschke was not portrayed as an icon and pacifist either at his funeral or at the memorial service in the Free University of Berlin on January 3, 1980. Rather, this view was expressly rejected by those who were reminiscent of Dutschke's early Christian pacifism. Kraushaar ignored these obituaries. Rainer Stephan accused Kraushaar of not defining terms such as “anti-authoritarian”, “extra-parliamentary”, “movement”, “revolt”, “direct action”, “urban guerrilla” etc. so that possible differences in meaning would not be visible. It is not plausible that the early Dutschke should have already provided the theory for the terror, from which he later sharply distinguished himself: “Kraushaar's own, highly unsystematically presented quotes demonstrate that worlds between Dutschke's considerations about an 'urban guerrilla' and the complete one apolitical terror practice of the RAF. " Klaus Meschkat recalled Kraushaar's earlier distinction between Dutschke's and Baader's understanding of urban guerrilla and criticized:" If a word like 'urban guerrilla' appears in the posthumous documents, he no longer asks about its meaning in the respective context He is only interested in the evidence of an assumed readiness for armed struggle à la RAF. Otherwise, well-known anecdotes are retold in great detail, with which Rudi Dutschke should at least reveal himself as a potential terrorist ... "Kraushaar's" criminal investigation exercises "did not take into account the historical situation that explains Dutschke's position. Explaining this context is actually "the duty of a conscientious historian". Oskar Negt had already declared in 1972 to be hypocritical to condemn violence on the part of students without referring to the Vietnam War .