German Communist Party

| German Communist Party | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Party leader | Patrik Köbele |

| vice-chairman | Wera Richter |

| Honorary Chairman | † Max Reimann |

| founding | September 1968 |

| Place of foundation | Frankfurt am Main |

| Headquarters | eat |

| Youth organization | SDAJ (related) |

| newspaper | Our time |

| Alignment |

Communism Marxism-Leninism |

| Colours) | red |

| Government grants | no |

| Number of members | 3500 (2017) |

| Minimum age | 16 years |

| Average age | 60 years |

| International connections | International meeting of communist and workers' parties |

| Website | dkp.de |

The German Communist Party ( DKP ) is a small communist party founded in 1968 in the Federal Republic of Germany . Due to personal continuities and similarities in terms of content with the KPD , which was banned in 1956 , it is considered to be the relevant successor organization. It is observed by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution and classified by them and political scientists as left-wing extremist .

The DKP sees itself as a revolutionary party that is “guided by the future and overall interests of the workers and employees” and is committed to the theory of Marx, Engels and Lenin . In doing so, she refers to previous socialist states such as Cuba , the GDR or the Soviet Union . Although it distances itself from Stalin's crimes, it pays tribute to Stalin's elevation of the Soviet Union to a world power .

Until 1990 it was the party with the largest number of members on the left of the SPD and the Greens in the Federal Republic of Germany . In political elections, it was unsuccessful with a maximum of 3.1% in the Bremen state election in 1971 . In 2008, the DKP member Christel Wegner entered the Lower Saxony state parliament on the open list of the left .

history

prehistory

In August 1956, the KPD was banned by the Federal Constitutional Court , although in March 1956, as a result of the XX. At the party congress of the CPSU had discussed that based on Khrushchev's concept of the "peaceful competition of systems" (according to which the communist parties in Western Europe could also achieve political power in a parliamentary and not only revolutionary way) from the party program of 1952 objectives such as "revolutionary Overthrow of the Adenauer regime ”would have to be revoked and would have to be assessed as a strategically wrong direction. The KPD thereby acknowledged the "constitutional fundamental rights and freedoms" which it called the "ground" of its "struggle" and which it claimed to defend "resolutely against breaches of the constitution and authoritarian arbitrariness".

With the help of the SED and the GDR government, between 1948 and 1952 those party members were removed or excluded from leadership positions in the KPD who spoke out in favor of tolerating the political structures of the Federal Republic and for political work within them. The deputy chairman of the KPD, Kurt Müller , was lured to East Berlin by the later honorary chairman of the DKP, Max Reimann , where he was arrested and sentenced by a Soviet court as an alleged agent to 25 years in prison.

Because of the KPD ban, there was therefore a need for a successor party for their supporters. The reorientation of March 1956 was not taken into account in the prohibition ruling. However, it remained decisive for the KPD and the efforts initially for a readmission, then for a new constitution in the form of the DKP in the 1960s.

Reconstitution

In 1967 and 1968 parts of the SDS , the DFU , the left-wing socialist groups ASO , ADS and the “Initiative Committee for the Re-Admission of the KPD” came together in a project called the “Socialist Center” . The attempt to form a joint organization in connection with the 1968 movement and to include the Communists of the KPD ultimately failed because they preferred their own party with a stronger left profile.

In June 1968 the "Arbeitsbüro", the leading institution of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in the eastern part of Berlin for the KPD, which was illegal after the judicial ban, made an advance in matters of "further development of the Communist Party in West Germany". It drew up a roadmap for the establishment of a communist party, which was actually followed later. First, however, the SED Politburo had to agree.

The phases after the founding were formulated, the concept of a party newspaper as a “collective organizer of the party” was drawn up and organizational concepts outlined. With regard to the relationship with the SED, it was said: “Under the changed conditions, securing a correct political line is of decisive importance.” The long hesitant KPD leadership gave in to the SED's urging and followed it with a decision by its Politburo. After the DKP was founded on September 25, 1968 by the “Federal Committee for the Reconstitution of a Communist Party” in Frankfurt am Main - there was talk of a new constitution because the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) had never ceased to exist - a first one in the labor office Draft of the party statutes spotted. In addition, there was a catalog of requirements for the period up to the 1st party congress and a sketch of an alliance concept. As part of the “practical-political tasks of our department in preparation for the friends' party convention”, thought was given to “how and in what form our department realizes the concrete cooperation with the brother party, how the ideas and ideas worked out by us enter politics find the brotherly party ”. The chairman of the KPD, Max Reimann , joined the DKP in September 1971 and symbolically and politically proclaimed the reference of the DKP to the KPD. Reimann was honorary chairman of the DKP until his death in 1977. The founding members of the DKP consisted primarily of members of the KPD as well as Marxist-oriented members of the socialist wing of contemporary social and political movements ( extra-parliamentary opposition (APO) , 1968 movement ). The number of members was 9,000 in the year it was founded, 42,000 in 1978 according to the North Rhine-Westphalian Interior Minister and 49,000 according to the party’s own information in 1981.

The founding of the DKP was preceded in July 1968 by a conversation between two KPD functionaries and Justice Minister Gustav Heinemann of the ruling grand coalition , in which the latter refused to allow the KPD to be re-admitted and the establishment of a new party as the way to legalize political work Communists in the Federal Republic recommended.

The DKP participated together with the Federation of German (BdD), the German Peace Union (DFU), the SDAJ , the Franconian district , the VVN , the West German Women's Peace Movement (WFFB) and the Association of Independent Socialists (VU) on electoral alliance Action Democratic Progress (ADF), which ran as a party in the 1969 federal election, but failed nationwide with 0.6% at the five percent hurdle . Double membership in the DKP and the ADF was permitted.

Even more than the grand coalition, the social-liberal coalition ruling from 1969 under Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt was interested in improving relations with the GDR and the other socialist states ("New Ostpolitik", "Change through rapprochement") , including the tolerance of a communist party was a precondition in the country itself. Another essential element of the willingness to accept a communist party as legal was the parliamentary successes of an NPD that was not forbidden and generally judged there as neo-Nazi , which was widely criticized abroad . This was about conflict material in relation to the other Western European states, in which communist parties were part of the parliamentary order.

At the same time, the Brandt government, led by Social Democrats, endeavored to prevent repercussions from external to internal policy and to limit the public effectiveness of communist and left-wing socialist policies as much as possible. Up until then, repressive measures had taken extensive forms such as arrests, trials and long-term imprisonment. Even if there was no conviction due to lack of evidence, the dismissal was usually followed by prolonged unemployment. The Brandt government and the interior ministers of the federal states followed up on the last variant in 1972 with the radical decree , after the previous forms of repression no longer seemed practicable and a renewed prohibition procedure against the new foundation because of unconstitutionality was outside the discussion. As a result, the decree led to so-called professional bans against what it was said to be anti- constitutional in the public service . Thus the legally relevant term of unconstitutionality, as it had been the basis of the KPD ban, was avoided and the defense against the undesirable was made an object of political and secret service activity. Since, with the exception of the dictatorial regimes in Spain and Portugal, communist parties were an element of national politics everywhere in Western and Central Europe, the radical decree sometimes met with incomprehension abroad.

West Berlin

In Berlin, the KPD ceased to exist from 1946 as a result of the forced merger with the SPD to form the SED . Since May 1946, due to a decision by the Allied Control Council , the SED had been a legal party throughout Berlin, on which the West German KPD ban of 1956 could not take legal effect. In April 1959, the SED created its own leadership for its district organizations in the western sectors of Berlin , thus taking into account the three-state theory developed by the Soviet Union in 1958 . The organization was controlled and financed together with the banned KPD and later the DKP from the SED headquarters in a disguised form through the changing departments responsible for “Western work”. Both were dependent on the SED in every way throughout their time. The construction of the Berlin Wall caused the SED to rename the West Berlin organization to SED West Berlin in 1962. After the consolidation of the newly founded DKP, it was renamed the Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin (SEW) in 1969 . The incompatibility resolutions and the radical decree created in the Federal Republic as a reaction to the de facto resurrection of the communist party turned the democratic parties, the trade unions and the public administration on to members and activists of “communist” organizations in West Berlin as well, due to their integration into the local political system and thus also to that of SEW.

When the SED mutated into the PDS as a result of the collapse of the GDR , which made it impossible for their previous satellite organizations SEW and DKP to merge into an all-German "party of the working class", the remaining third of the SEW members tried in April 1990 1989 a new start as a socialist initiative (SI). The SI, unsuccessful and unnoticed in reunified Germany , decided to dissolve itself in March 1991.

Development until 1989

Within the world communist movement, the DKP cultivated the closest ties to the SED. This included extensive financial and political support from the SED. Since the DKP expected disadvantages from disclosure of the support from the SED, the SED supported the DKP, for example, by means of front companies. During the Honecker era, around 70 million DM were transferred annually from East Berlin to the DKP headquarters in Düsseldorf.

In line with its self- image as a “party of the working class”, the DKP endeavored to convey its views in the trade union movement . The party was comparatively strong in the metal industry.

By the 1980s, the party gained some influence in cultural life. For example, writers joined her at times or were close to her, such as Martin Walser or scientists like Werner Plumpe .

In the federal elections between 1972 and 1983, the DKP won a maximum of 0.3% of the votes. In the state elections in 1971 it achieved its highest result with 3.1% in the Bremen citizenship election. At the communal level, two patterns of communities can be identified in which the DKP was able to obtain mandates: on the one hand, in workers' residential communities with a long left-wing tradition such as Bottrop in the Ruhr area or Mörfelden in Hesse, and on the other hand in university cities such as Marburg or Tübingen.

The DKP defended the violent suppression of the popular uprising of June 17, 1953 in the GDR as well as the construction of the wall and welcomed the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. They welcomed the violent crackdown of the Prague Spring in 1968 as a contribution to the “further development of socialist democracy”.

In the 1970s, currents developed which, with reference to a renewed Marxism , demanded democratic party structures and “open discussions”. The party leadership, however, continued to uphold the organizational principle of democratic centralism , even if the term itself was avoided. In particular after the expatriation of the songwriter Wolf Biermann from the GDR at the end of 1976, there were demands from members for an orientation towards Eurocommunist approaches, which were suppressed by the party leadership. Thereupon, mostly excluded or disappointed comrades from the academic field founded the Working Group West European Workers' Movement (AWA). As a result, there were party withdrawals and expulsions, e.g. B. in Marburg (Günter Platzdasch), in North Rhine-Westphalia ( Detlev Peukert ) and around the magazine Düsseldorfer Debatte (Michael Ben, Peter Maiwald , Thomas Neumann ).

After 1980 the DKP concentrated on the peace movement . She was also involved in the peace list , which took part in a number of elections in the mid-1980s, for which Uta Ranke-Heinemann , daughter of the former Federal President Gustav Heinemann , also ran , and which also achieved selective successes. In the peace movement, the DKP advocated a line of “minimal consensus” within the framework of the Krefeld appeal : fighting (also under the election campaign motto “jobs instead of missiles!”) The NATO double decision as the “lowest common denominator”.

From 1985 onwards, Mikhail Gorbachev's new political line in the Soviet Union also motivated members of the DKP to question earlier positions. The great importance that disarmament as the most important "human issue" had in the political practice of its members at the height of the peace movement led to an alienation in parts of the membership from the original content of a communist party and left the profile of the DKP as a "party of the Working class ”. The Chernobyl nuclear disaster (1986) also caused an increase in criticism of the positions of the party leadership and the party majority, which until then had only spoken out against nuclear power plants in so-called capitalist countries , since, in their opinion, the dangers mainly from profit maximization Operation of nuclear power plants resulted.

The contradictions first became clearly visible at the 1986 Hamburg party congress . A current of “innovators” formed. In the course of the dissolution process in the socialist countries in 1989/1990, these forces left the DKP. Sometimes they ended their political engagement, sometimes they turned to other parties, especially the SPD or the PDS . Individual prominent intellectuals and functionaries such as the writer Peter Schütt , the journalist Franz Sommerfeld or the journalist Christiane Bruns then completely changed their political orientation and became temporarily or permanently prominent representatives of the media life of the Federal Republic of Germany.

The internal disputes, the rapid collapse of the real socialist systems in Europe, but above all the end of the GDR that supported the DKP (see also party finances and assets ) as well as the general decline of the left that accompanied these processes led the DKP into a deep existential crisis. From up to 57,000 (highest named party official number 1986) or 42,000 (constitution protection reports) members remained after 1989 a few thousand.

DKP military organization

From 1969 to 1989 the GDR trained around 200 DKP members of the Ralf Forster group to be paramilitary. In the event of war, they should carry out acts of sabotage and attacks on persons. This group was supplied with money, weapons and explosives by the GDR. The theoretical training took place in East Berlin. At Springsee in Brandenburg, the practical training was carried out by officers of the NVA on the subjects: "Handling weapons and explosives, the tactics of small combat groups, camouflage, covering up tracks and the silent killing of people."

Break-in and reorientation after 1989

Those who remained wanted to the principles of Lenin oriented party of the working class with a uniform view of the world to defend. Nevertheless, it turned out that even within the rest of the DKP, opposing positions existed in many respects. The problem was exacerbated by the accession of former SED members in the new federal states and East Berlin , who accuse the West Party of tendencies towards revisionism and "ideological capitulation" before the turning point and peaceful revolution in the GDR known as " counterrevolution " . Unlike before 1989, the DKP no longer hid its internal tensions from the outside, but instead conducted the controversial discussions openly in the party newspaper, Our Time . The Marxist philosopher Hans Heinz Holz , who had been a member of the party since 1994 , played a key role in shaping the new program . At the 17th party congress in April 2006, the 1978 program was replaced.

In the 2009 Bundestag election, the DKP only ran in Berlin and received fewer than 2000 second votes; nationwide, their election result is shown as 0.0%. Via the lists of the PDS and the party Die Linke as well as by running their own candidacy and via electoral alliances, DKP members were able to move into around 20 predominantly local parliaments.

Alignment from 2010

In the years from 2010 onwards, there were more and more disputes about the content of the DKP. The majority of the party and the party executive committee around the chairwoman Bettina Jürgensen , the former chairman Heinz Stehr and the party executive member Leo Meyer wanted to continue the course of the “realignment” of the party and strived to continue the close cooperation with the Left Party and to expand the observer status' in the European Left Party (EL) for full membership. The minority around the party board member Patrik Köbele and Hans-Peter Brenner wanted to end their observer status in the EL , run for supraregional elections and make the party more independent and “class struggle”.

On March 2 and 3, 2013, the 20th party conference of the DKP took place in Mörfelden-Walldorf . Here it came to a battle vote in the election for party chairmanship between incumbent Bettina Jürgensen and her challenger Patrik Köbele. Köbele won the election and wanted the party to be "more militant and revolutionary, again emphasizing the class struggle, class consciousness and the avant-garde role of the Communist Party". "The distance to those forces who prefer reforms within the existing social system to anti-imperialist revolutionary rhetoric without social support as a short-term goal will increase," emphasized Köbele when he took office.

The DKP ended its observer status in the European Left Party on February 27, 2016 at the 21st party congress. The camp around the former chairmen Bettina Jürgensen, Heinz Stehr and the “architect of the reform course” in the party, Leo Meyer, organized itself in the Communist Network and in the Marxist Left Association (MaLi) . MaLi is the official “partner movement” of the European Left Party. Over 70 MaLi members left the DKP in the years after the 20th party congress.

In the course of the intra-party discussion about the party's orientation in relation to the anti-monopoly strategy (AMS) , some, especially young members, left the party and the SDAJ because they rejected the AMS . You first established the context, how next? , from which the Communist Organization (KO) emerged in mid-2018 .

The DKP received 20,396 votes (0.1%) in the 2019 European elections.

On November 9, 2019, the DKP celebrated the 70th anniversary of the founding of the GDR, the “first socialist state on German soil”, in their opinion “a necessary contrast to all the celebrations of the winners and beneficiaries of the fall of the Berlin Wall”. The GDR was "in spite of all contradictions [...] the greatest achievement of the workers' movement in Germany" and a "peace state" with which "essential social and humane rights were realized".

Observation by the constitution protection authorities

Since it was founded in 1968, the DKP has been monitored by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution . It is classified as left-wing extremist and anti-constitutional , as it recognizes itself as a “revolutionary party of the working class” to Marxism-Leninism and continues to strive for a revolutionary transformation of society. In addition, it is assumed that the DKP will increasingly rely on the extra-parliamentary struggle to raise its profile . The party is classified as "clearly unconstitutional" because of the following statement from the party program:

“Socialism cannot be achieved through reforms, but only through profound transformations and the revolutionary overcoming of capitalist property and power relations.”

Content profile

Self-positioning

The DKP sees communism as the ultimate goal of its policy . With this she describes "a social order in which the exploitation of humans by humans is eliminated, careful handling of nature is ensured and the free development of everyone is made possible as the condition for the free development of all".

According to her own statements, she sees “ socialism ” as a “historical transition period to the new society” .

The DKP sees itself “as a Marxist party with revolutionary goals”. It is based on "the findings of scientific socialism , the further development of which it promotes." In doing so, it would work together "on an equal footing and in partnership with other left and democratic organizations and parties". In addition, the DKP is “part of the communist and revolutionary movement while maintaining its complete independence”.

Party platform

On April 8, 2006 (at the 2nd meeting of the 17th party congress of the DKP in Duisburg) the delegates decided on a new party program . It replaced the 1978 program.

In the DKP's program of 1978 (decided at the party congress in Mannheim), the objective was to achieve the long-term goal of a “socialist society” by means of the transitional form of an “anti-monopoly democracy” . This was based on the analysis of modern capitalism as state monopoly capitalism , which was developed by Marxist economists and political scientists , also in the GDR and in France and at the Institute for Marxist Studies and Research (IMSF) in Frankfurt am Main, which is affiliated with the DKP was. Accordingly, an increasing and historically new entanglement of large and internationally operating corporations with the state administration and executive took place in capitalism , which made the distribution of the macroeconomic surplus product to the advantage above all of the large economy ("big capital") and to the detriment of small capital owners and employees in a new order of magnitude and endanger the democratic decision-making processes . This was accompanied by processes of social decline, which more than ever before would affect both the self-employed and the wage-dependent middle classes and whose combating required comprehensive social and political alliances against the policies of internationalized corporations .

In the preamble of its party program (2006), the DKP claims " class antagonisms have become sharper " . The program no longer relies on “units of action” with social democrats . As before, however, the DKP is primarily striving for alliances with “progressive” democratic forces on the ground . Specifically, with the new program it opens up to the new social movements , the Monday demonstrations , Attac and the Antifa .

The DKP always viewed itself as part of the “socialist camp” gathered around the Soviet Union as its center. She maintained a particularly close relationship with the GDR and there with the SED. The orientation of the communist parties in Italy, Spain and temporarily France, known as Eurocommunism , was rejected as “social reformist” and as a path to social democracy.

It just as decidedly condemned all efforts of left groups of the 1970s and 1980s to conquer political power also by means of violence, and declared that the road to socialism should only be strived for by peaceful and democratic means within the framework of the constitutional possibilities.

Disputes

At the analytical level, the DKP primarily deals with two issues. From their different answers, contradicting conclusions arise for their self-image.

- On the one hand, there is the question of what the causes of the failure of socialism in the Soviet Union and in the other Eastern Bloc countries were and what consequences should be drawn from this so that a contemporary conception of socialism can emerge.

- What failed the so-called real socialism ;

- what significance did internal political and economic deficits and contradictions such as the lack of democracy or a high level of social benefits and

- What was the weight of the economic, political and arms race pressures of the competing system?

An essential question beyond this research into the causes is that of the role of democratic co-determination within a socialist society.

- On the other hand, it is controversial how the terms imperialism and globalization should be interpreted. In part globalization is viewed as a qualitatively new stage of development of capitalism , which is characterized by transnational capital entanglements, in part it is believed that the world situation remains unchanged with the basic concepts from Lenin's work Imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism (1917) describe and explain that the increase in international trade is only a quantitative phenomenon.

In contrast to the resolutions of the party as a whole, the state associations in Berlin and Brandenburg announced in May 2009 that they wanted to run for the 2009 Bundestag election . With regard to independent participation in elections, there was only agreement that they should run for the 2009 European elections.

structure

Party congresses

According to the statute of the DKP of 2018, the party congress is the highest organ of the party and takes place every 2 years. So far (June 29, 2019) the following party congresses have taken place:

| Party congress | year | date | place |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. | 1969 | 04/12 - 04/13 | eat |

| II. | 1971 | 25.11. - 11/28 | Dusseldorf |

| III. | 1973 | 11/02 - 04.11. | Hamburg |

| IV. | 1976 | 19.03. - 21.03. | Bonn |

| V. | 1978 | 20.10. - 10/22 | Mannheim |

| VI. | 1981 | 05/29 - 31.05. | Hanover |

| VII. | 1984 | 06.01. - 08.01. | Nuremberg |

| VIII. | 1986 | 02.05. - 04.05. | Hamburg |

| IX. | 1989 | 06.01. - 08.01. | Wuppertal |

| X. | 1990 | March | Dortmund |

| XI. | 1991 | 05/10 - 12.05. | Bonn |

| XII. | 1993 | 16.01. - 17.01. | Mannheim |

| XIII. | 1996 | 03.02. - 04.02. | Dortmund |

| XIV. | 1998 | May 22nd - May 24th | Hanover |

| XV. | 2000 | 02.06. - 04.06. | Dusseldorf |

| XVI. | 2002 | 11/30 - 01.12. | Dusseldorf |

| XVII. 1st conference | 2005 | 02/12 - 13.02. | Duisburg |

| XVII. 2nd meeting | 2006 | April 8th | Duisburg |

| XVIII. 1st conference | 2008 | 02/23 - 24.02. | Moerfelden-Walldorf |

| XVIII. 2nd conference (EU election conference) | 2009 | 10.01. | Berlin |

| XIX. | 2010 | 09.10. - 10.10. | Frankfurt / Main |

| XX. | 2013 | 02.03. - 03.03. | Moerfelden |

| XXI. | 2015 | 11/14 - November 15 | Frankfurt / Main |

| XXII. | 2018 | 02.03. - 04.03. | Frankfurt / Main |

| XXIII. | 2020 | 28.02. - 01.03. | Frankfurt / Main |

Members

Since reunification, the DKP has shrunk from tens of thousands of members in the 1980s to around 4,200 (2008), then to around 4,000 (2009), in 2013 to around 3,500, and in 2014 to around 3,000.

Associations

The party is present with 18 district associations in all 16 federal states. The federal states of Bavaria and North Rhine-Westphalia are each divided into two district associations (Northern Bavaria / Southern Bavaria and Rhineland-Westphalia / Ruhr-Westphalia). There are also various district associations .

| district | Number of members | groups | Chairman | Result of the last election of the state parliament |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | under 500 | 7th | 0.0% ( 2016 ) | |

| Bavaria | 340 | 9 | August Ballin (Northern Bavaria) | na ( 2018 ) |

| Berlin | 130 | 6th | Rainer Perschewski | 0.2% ( 2016 ) |

| Brandenburg | 100 | 11 | only started with direct candidates ( 2019 ) | |

| Bremen | 70 | 1 | na ( 2019 ) | |

| Hamburg | 180 | 2 | Michael Gotze | na ( 2020 ) |

| Hesse | 400 | 14th | Axel Koppey | na ( 2018 ) |

| Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | 30th | 6th | 0.2% ( 2016 ) | |

| Lower Saxony | 370 | 8th | Detlef Fricke | na ( 2017 ) |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 800 | 20th | Marion Köster (Ruhr-Westphalia) Wolfgang Bergmann (Rhineland-Westphalia) |

0.0% ( 2017 ) |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 90 | 6th | na ( 2016 ) | |

| Saarland | 200 | 1 | Thomas Hagenhofer | na ( 2017 ) |

| Saxony | 40 | 4th | na ( 2019 ) | |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 40 | 5 | na ( 2016 ) | |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 180 | 2 | na ( 2017 ) | |

| Thuringia | 40 | 7th | na ( 2019 ) |

Commissions

In the party executive committee, commissions and working groups are formed both for permanent activity in one area and for the completion of specific, temporary work assignments. The commissions are advisory bodies to the party executive. You are responsible for drawing up decisions and draft resolutions. Insofar as they are active in a certain political field, they have the right to submit statements on their own responsibility in coordination with the responsible party chairman or secretariat members, to represent the DKP in alliances and to address the public in this area.

Permanent commissions include:

- Company and trade union policy

- Marxist Theory and Education Commission

- Finance Commission

- AG public relations

- International Commission (IC) and AG Cuba Solidarity as part of the IC

- Youth Commission

- Women's working group

- Culture Commission

- History Commission

- DKP queer: Since 2006 there has been an internal party committee of the party executive committee "DKP queer", which deals with orientation, genders and practices of human sexuality. The aim of their work is a society in which these aspects have no meaning in evaluating a person. She has her own publication with the magazine red & queer, which appears four times a year . A collective leadership is elected once a year . The head of the commission, Thomas Knecht from Hesse, who was elected by the party executive committee, is also represented in this collective management as the “organizational responsible”, who is also responsible for red & queer under press law. At the second party board meeting of the 19th party board of the DKP in December 2010 Knecht was elected head of the commission for the first time. At the constituent meeting of the 20th party executive committee on March 23, 2013, Knecht was re-elected as head of the commission.

Publications

The party newspaper is Our Time , which appears weekly in Essen . The theoretical organ Marxist sheets , which is closely related to the DKP, appears every two months . The Neue Impulse Verlag and the Marx-Engels-Foundation in Wuppertal are also connected to the DKP. The party's training center is the Karl Liebknecht School in Leverkusen. In addition, the DKP organizes the UZ press festival every two years .

There are also small publications with corporate or local reach.

Party finances and assets

Due to its election results, the party does not receive any funds from state party funding. The annual report for 2011 is listed in Bundestag printed paper 18/1080. Accordingly, the party received this year income of around 1,429,000 euros, including

- approx. 34% membership fees

- approx. 39% donations

It closed in 2011 with approx. 21,000 euros deficit, in 2010 it was approx. 93,000 euros deficit, her net worth in 2011 was approx. 667,000 euros.

Financing by the GDR

According to the findings of the Independent Commission to Review the Assets of the Parties and Mass Organizations of the GDR , the DKP received payments from the GDR ( Commercial Coordination Department ) totaling DM 526,309,000 (about 270 million euros) in the period 1981 to 1989 . These amounts were not shown in the reports to the German Bundestag. On October 15, 1989 - two days before his fall - SED chief Erich Honecker approved the payment of around 65 million DM for 1990 to the DKP and its “friendly organizations”. Party officials were given bogus employment at SED party companies in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Parliamentary representation

The DKP is locally successful and represented in several local parliaments, both alone and in left-wing alliance lists. In the corresponding places - some since the 1920s - communists have been elected to parliaments again and again. The independent city of Bottrop and Gladbeck can be named as the focal points of the local political presence and activity of the DKP in the northern Ruhr area . In 2009, the DKP lost its seat on the city council in Essen . In addition, Mörfelden-Walldorf and Reinheim in southern Hesse as well as Heidenheim in Baden-Württemberg and Püttlingen in Saarland should be mentioned as focal points. In Hesse, 24 DKP members were elected to the local parliaments via their own lists and on alliance lists with the Left Party. In Nordhorn , the DKP held mandates on the city council between 1976 and 2016. In the Grafschaft Bentheim district , in which Nordhorn is located, she had a district council mandate until 2016.

From 2008 to 2013 she was represented in the state parliament of Lower Saxony with Christel Wegner, who was elected from the list of the party Die Linke and later excluded from its parliamentary group .

| Elective area | Year of choice | Seats | percent | Election designation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bochum | 2014 | 1 seat | 0.9% | Social List Bochum |

| Bottrop | 2014 | 2 seats | 4.0% | German Communist Party |

| Bottrop center | 2014 | 1 seat | 4.6% | German Communist Party |

| Bottrop-South | 2014 | 1 seat | 5.8% | German Communist Party |

| Gladbeck | 2014 | 1 seat | 1.4% | German Communist Party |

| Nuremberg | 2020 | 1 seat | 1.3% | Left list Nuremberg |

| Püttlingen | 2014 | 1 seat | 3.37% | German Communist Party |

| Reinheim | 2016 | 4 seats | 11.1% | German Communist Party |

| Reinheim local advisory board | 2016 | 1 seat | 9.9% | German Communist Party |

| Reinheim, Ueberau district | 2016 | 2 seats | 39.0% | German Communist Party |

| Moerfelden-Walldorf | 2016 | 6 seats | 14.0% | German Communist Party / Left List |

| Heidenheim an der Brenz | 2019 | 1 seat | 2.3% | German Communist Party |

Related organizations

The Socialist German Workers' Youth (SDAJ) is a youth organization close to the DKP, the Marxist Student Union Spartakus (MSB or MSB-Spartakus) was the DKP- related student organization that disbanded after the reunification of Germany . With the Association of Marxist Students (AMS), a new DKP-affiliated and nationwide university group was created at the end of the 1990s.

The DKP works with the communist platform of the party Die Linke primarily at the local level. For example, the DKP runs a “Left Center” in Münster together with the Left . In addition, around 30 DKP members moved into local parliaments via the Left Party's list. The Hessian state association called for the election of the left after it did not run for the state election in 2008.

Location determination

At the national level

The party leadership strove for a cautious and cautious opening and renewal while avoiding open conflicts with the "left orthodox". Nonetheless, the left wing of the party accused it of undermining and destroying the foundations of communist identity.

For the 2005 Bundestag elections , the DKP called for the election of the Linkspartei.PDS , whose electoral lists included individual DKP members.

In terms of electoral politics, the DKP oriented itself primarily towards cooperation with the Die Linke party ; it supported their lists and tried to participate in them according to their orientation towards “bundling the left-wing forces”, as it is planned in the new program of the DKP adopted in 2006. The DKP held its 18th party congress from February 23 to 24, 2008 in Mörfelden-Walldorf, Hesse, one of the places with a communal base. With the re-election of Heinz Stehr as chairman and Nina Hager as his deputy and, for the first time, Leo Mayer as additional deputy, the course of the party leadership was confirmed against about a third of the delegates, as was the case with the major political votes. The minority had demanded a concentration on company and local politics and was against the European political orientation of the DKP to cooperation in the party “European Left”. The issue, which was still being discussed, was whether the “main opponent” in times of globalization was “transnational capital” (majority) or “German imperialism” (minority).

At the 20th party conference of the DKP on March 2, 2013 Patrik Köbele was elected chairman of the DKP. After the election, Patrik Köbele completely replaced the old party executive. Since then, the DKP has been a Marxist-Leninist party again, which introduced democratic centralism as its form of organization and sees itself not as a “left collective movement”, but as a communist party. The previous chairwoman, Bettina Jürgensen, and with her the entire DKP district of southern Bavaria resigned due to this development.

At the 21st party congress, the DKP ended its observer status in the “European Left” and has since worked less and less with the Left Party. In the 2017 federal election, the DKP ran for the first time since the 2005 federal election and did not call for the election of the Left Party.

On international level

The positioning of the DKP on an international and especially on a European level has been controversial since around 2000. Since capital today mainly acts transnationally, according to the majority of the party executive, which provokes the contradiction of the minority at the time, anti-capitalist resistance cannot be restricted to the framework of the nation state .

For the DKP, the question of the best possible international cooperation is therefore linked to the problem of determining its own position. At the 14th party conference of the DKP in the spring of 2000, the DKP Federal Chairman Heinz Stehr called for the creation of a “European Communist Party” as an answer to the “challenges of capital-driven European unification”. But since the communist parties in Europe take different positions in many respects, this idea could not be realized.

In the 2000s, the DKP participated in two Europe-wide amalgamations of radical left parties: On the one hand, the Party of the European Left (EL), which consists primarily of post, reform and neo-communist parties such as the German party Die Linke , the French PCF and the Italian PRC exists, on the other hand the European Anti-Capitalist Left (EAL), which is mainly formed by Trotskyist- influenced organizations, but has lost its importance (as of 2008).

Between 2001 and 2006 the DKP took part in the EAL conferences at irregular intervals. She had observer status in the EL for a long time. The cooperation with the EL in the DKP is supported and promoted by forces oriented towards opening up and renewal, while the “left-orthodox” wing of the party strongly rejects close cooperation with “reformists”. On the third day of the XXI. At the DKP party congress in 2016, the majority decided to end observer status in the European Left Party.

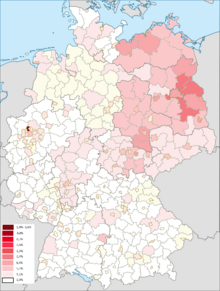

State election results of the DKP since 1970

In the states of Thuringia and Saxony, the party has not yet run to a state election.

| BW | BY | BE | BB | HB | HH | HE | MV | NI | NW | RP | SL | SN | ST | SH | TH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 0.4% | 1.7% | 1.2% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 2.7% | ||||||||||

| 1971 | n / A | 3.1% | 0.9% | 0.4% | ||||||||||||

| 1972 | 0.5% | |||||||||||||||

| 1974 | 0.4% | 2.2% | 0.9% | 0.4% | ||||||||||||

| 1975 | n / A | 2.2% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 0.4% | ||||||||||

| 1976 | 0.4% | |||||||||||||||

| 1978 | 0.3% | 1.0% | 0.4% | 0.3% | ||||||||||||

| 1979 | n / A | 0.8% | 0.4% | 0.2% | ||||||||||||

| 1980 | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.5% | |||||||||||||

| 1981 | n / A | |||||||||||||||

| 1982 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.3% | ||||||||||||

| 1983 | n / A | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.1% | ||||||||||||

| 1984 | 0.3% | |||||||||||||||

| 1985 | n / A | n / A | 0.3% | |||||||||||||

| 1986 | n / A | 0.2% | 0.1% | |||||||||||||

| 1987 | 0.6% | n / A | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% | |||||||||||

| 1988 | 0.2% | 0.1% | ||||||||||||||

| 1989 | n / A | |||||||||||||||

| 1990 | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | 0.0% | 0.1% | n / A | n / A | n / A | ||||||

| 1991 | n / A | 0.1% | n / A | n / A | ||||||||||||

| 1992 | 0.0% | n / A | ||||||||||||||

| 1993 | n / A | |||||||||||||||

| 1994 | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | ||||||||

| 1995 | n / A | n / A | 0.1% | 0.1% | ||||||||||||

| 1996 | 0.0% | n / A | 0.0% | |||||||||||||

| 1997 | n / A | |||||||||||||||

| 1998 | 0.0% | n / A | 0.2% | n / A | ||||||||||||

| 1999 | n / A | n / A | n / A | 0.1% | n / A | n / A | n / A | |||||||||

| 2000 | 0.0% | n / A | ||||||||||||||

| 2001 | 0.0% | 0.1% | n / A | n / A | ||||||||||||

| 2002 | n / A | 0.1% * | ||||||||||||||

| 2003 | n / A | n / A | 0.2% | n / A | ||||||||||||

| 2004 | 0.2% | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | |||||||||||

| 2005 | n / A | 0.1% | ||||||||||||||

| 2006 | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | 0.1% * | |||||||||||

| 2007 | n / A | |||||||||||||||

| 2008 | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | ||||||||||||

| 2009 | 0.2% | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | ||||||||||

| 2010 | n / A | |||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 0.0% | 0.2% | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | |||||||||

| 2012 | n / A | n / A | n / A | |||||||||||||

| 2013 | n / A | n / A | n / A | |||||||||||||

| 2014 | 0.2% | n / A | n / A | |||||||||||||

| 2015 | n / A | n / A | ||||||||||||||

| 2016 | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.2% | n / A | n / A | |||||||||||

| 2017 | n / A | 0.0% | n / A | n / A | ||||||||||||

| 2018 | n / A | n / A | ||||||||||||||

| 2019 | n. D. | n / A |

*) DKP / KPD electoral alliance

na = not started; n. D. = direct candidates only

| highest result in the federal states (without entering the state parliament) |

Federal election results since 1972

| Bundestag election results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| year | Number of votes | Share of votes | |

| 1972 | 113,891 | 0.3% | |

| 1976 | 118,581 | 0.3% | |

| 1980 | 71,600 | 0.2% | |

| 1983 | 64,986 | 0.2% | |

| 1987 | n / A | n / A | |

| 1990 | n / A | n / A | |

| 1994 | n / A | n / A | |

| 1998 | n / A | n / A | |

| 2002 | n / A | n / A | |

| 2005 | n / A | n / A | |

| 2009 | 1,894 | 0.0% * | |

| 2013 | n / A | n / A | |

| 2017 | 11,713 | 0.0% ** | |

*) only competed in Berlin **) only competed in 9 of 16 federal states

In the Bundestag elections in 1994, 1998, 2002 and 2013, the DKP did not run with a list, but did put forward direct candidates who were able to get 0.0% of the first votes in each of the aforementioned elections.

European election results since 1979

| European election results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| year | Number of votes | Share of votes | |

| 1979 | 112.055 | 0.4% | |

| 1984 | n / A | n / A | |

| 1989 | 57,704 | 0.2% | |

| 1994 | n / A | n / A | |

| 1999 | n / A | n / A | |

| 2004 | 37,160 | 0.1% | |

| 2009 | 25,615 | 0.1% | |

| 2014 | 25,147 | 0.1% | |

| 2019 | 20,419 | 0.1% | |

| n / A | not started |

Federal Chairperson

| Surname | Beginning of the term of office | Term expires | particularities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kurt Bachmann | 1969 | 1973 | ||

| Herbert Mies | 1973 | 1990 | ||

| Heinz Stehr | 1990 | 2010 | 1990–1996 only provisionally in office | |

| Bettina Juergensen | 2010 | 2013 | ||

| Patrik Köbele | 2013 | officiating | ||

See also

literature

- Rolf Ebbighausen , Peter Kirchhoff: The DKP in the party system of the Federal Republic. In: Jürgen Dittberner , Rolf Ebbighausen: Party system in the legitimation crisis. Studies and materials on the sociology of the parties in the Federal Republic of Germany (= writings of the Central Institute for Social Research at the Free University of Berlin . Vol. 24). Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1973, ISBN 3-531-11212-0 , pp. 427-466.

- Helmut Bilstein, Sepp Binder, Manfred Elsner: Organized Communism in the Federal Republic of Germany: DKP, SDAJ, MSB Spartakus, KPD / KPD (ML), KBW / KB (= analyzes . 15). 4th revised and expanded edition, Leske and Budrich, Opladen 1977, ISBN 3-8100-0140-6 .

- Ossip K. Flechtheim , Wolfgang Rudzio , Fritz Vilmar : The march of the DKP through the institutions. Soviet Marxist strategies of influence and ideologies (= Fischer pocket books . 4223). Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-596-24223-1 .

- Manfred Wilke , Hans-Peter Müller, Marion Brabant: The German Communist Party (DKP). History, organization, politics (= library science and politics . Vol. 45). Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-8046-8762-8 .

- Georg Fülberth : KPD and DKP 1945–1990. Two communist parties in the fourth period of capitalist development (= Distel-Hefte . 20). Distel-Verlag, Heilbronn 1992, ISBN 3-923208-24-3 .

- Hans-Peter Müller: Foundation and early history of the DKP in the light of the SED files. In: Klaus Schroeder (ed.): History and transformation of the SED state. Contributions and analyzes (= studies by the SED State research association at the Free University of Berlin ). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-05-002638-3 , pp. 251-285.

- Patrick Moreau , Hermann Gleumes : The German Communist Party. Complement or competition for the PDS? In: Patrick Moreau, Marx Lazar, Gerhard Hirscher (eds.): Communism in Western Europe. Decline or mutation? Olzog, Landsberg am Lech 1998, ISBN 3-7892-9319-9 , pp. 333-374.

- Andreas Morgenstern: Extremist and Radical Parties 1990–2005. DVU, REP, DKP and PDS in comparison . Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-86573-188-0 .

- Michael Roik : The DKP and the democratic parties 1968–1984 (= Schöningh Collection on the past and present ). Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2006, ISBN 3-506-75725-3 .

- Eckhard Jesse : The new party program of the DKP . In: Uwe Backes , Eckhard Jesse (eds.): Yearbook Extremism & Democracy , 19th year (2007), Nomos, Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8329-3168-1 , pp. 199–212.

- Gerhard Hirscher, Armin Pfahl-Traughber (Ed.): What happened to the DKP ?. Contributions to the past and present of the extreme left in Germany (= publications on extremism and terrorism research . 1). Federal University of Applied Sciences for Public Administration, Brühl 2008, ISBN 978-3-938407-24-0 .

- Eckhard Jesse: German Communist Party (DKP) . In: Frank Decker , Viola Neu : Handbook of German political parties . 2nd revised and expanded edition, Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-658-00962-5 , pp. 238-240.

Web links

- Search via the German Communist Party in the catalog of the German National Library

- Search for German Communist Party in the German Digital Library

- Search for German Communist Party in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Armin Pfahl-Traughber : The "German Communist Party" (DKP). An analytical consideration of the development and status of the former intervention apparatus of the SED . Left-wing extremism dossier, Federal Agency for Civic Education , August 26, 2014

- Andreas Horn: The founding of the German Communist Party in 1968 . Federal Archives , June 15, 2013

- DKP website

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tagesschau, accessed on August 21, 2017

- ↑ Steffen Kailitz : Political Extremism in the Federal Republic of Germany: An Introduction. P. 68.

- ^ Olav Teichert: The Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin. Investigation of the control of SEW by the SED. kassel university press, 2011, ISBN 978-3-89958-995-5 , p. 93. ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ^ Eckhard Jesse: German history. Compact Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8174-6606-1 , p. 264. ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Between continuity and external determination. Mohr Siebeck, 1996, ISBN 3-16-146603-9 , p. 308. ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ Klaus Stern : The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Vol. V, Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-07021-3 , p. 1465.

- ↑ https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/download/broschuere-2016-05-linksextremismus.pdf

- ↑ Eckhard Jesse : Extremism . In: Uwe Andersen , Wichard Woyke (Ed.): Concise Dictionary of the Political System of the Federal Republic of Germany , 2nd edition, Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1995, p. 163

- ^ Armin Pfahl-Traughber , Left -Wing Extremism in Germany. A critical inventory. Springer, Wiesbaden 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Program of the German Communist Party (DKP). In: dkp-online.de. Retrieved December 30, 2014 .

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report ( Memento of October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), page 173

- ^ Democracy on Cuba / DKP news portal. In: dkp.de. September 23, 2014, archived from the original on October 15, 2014 ; accessed on December 30, 2014 .

- ↑ No negative, no positive Stalin cult on the DKP website

- ↑ Judick, G./Schleifstein, J./Steinhaus, K. (Eds.): KPD 1945-1968. Documents. Volume 2 . Neuss, 1989. p. 97 ff.

- ↑ Lutz Niethammer (ed.): The "cleaned" anti-fascism. The SED and the red kapos from Buchenwald. Documents. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-05-007049-0 , p. 259, note 12 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Communism Today Part V: The DKP in the conflict between adaptation and loyalty to Moscow . In: Der Spiegel . No. 23 , 1977 ( online ).

- ↑ Arno Klöne: Left Socialists in West Germany. In: Left Socialism in Germany, VSA Verlag, Hamburg 2010, p. 97 f.

-

↑ Kurt Bachmann u. a .: Explanation. (PDF) on the reconstitution of a Communist Party. In: Berliner Extradienst . Westberliner Zeitungsgesellschaft mbH, October 5, 1968, pp. 9-11 , archived from the original on April 11, 2020 ; accessed on April 11, 2020 (12 pages; 3.2 MB; .html version: http://www.trend.infopartisan.net/trd0918/t010918.html ).

The declaration is dated September 22nd, 1968. The first sentence after the heading reads: “The signatories of this declaration have reconstituted a Communist Party in the Federal Republic of Germany.” The third to last paragraph before the date line begins with the sentence: “The Federal Committee [for the reconstitution of a Communist Party] beats everyone who stands up want to join the newly constituted Communist Party before naming this party 'German Communist Party' according to the political and national conditions of its activity. "

- ↑ SAPMO Federal Archives DY 30 / IV 2 / 10.03-14 and further evidence from Hans-Peter Müller: Foundation and early history of the DKP in the light of the SED files. In: Klaus Schroeder (ed.): History and transformation of the SED state. Berlin 1994, pp. 251-285. From an earlier perspective, still without knowledge of the SED files: Siegfried Heimann, The German Communist Party, in: Richard Stöss (Ed.), Party Handbook. The parties of the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 (publications of the Central Institute for Social Science Research of the Free University of Berlin, Volume 38), Wiesbaden 1983, pp. 901–981.

- ↑ Side lights from the life of a communist. Franz Ahrens on Max Reimann . Hamburg 1968.

- ^ Ute Schmidt, Richard Stöss: Smaller parties in North Rhine-Westphalia. In: Ulrich von Alemann (Ed.): Parties and elections in North Rhine-Westphalia. Cologne / Stuttgart / Mainz / Berlin 1985, pp. 170–174, here: p. 174.

- ↑ Helmut Bilstein u. a .: Organized communism in the Federal Republic of Germany. Opladen 1977, p. 16.

- ↑ Bundestag printed paper 6/362 (double membership with DKP) Retrieved on September 5, 2019.

- ↑ Alexander von Brünneck: Political Justice against Communists in the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1968. Frankfurt am Main 1978, pp. 141-213.

- ↑ Horst Bethge u. a. (Ed.): The destruction of democracy through occupational bans. Cologne 1976.

- ^ Thomas Klein : SEW - Die Westberliner Einheitssozialisten. An “East German” party as a thorn in the flesh of the “front city”? Links, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86153-559-1 , pp. 91-98.

- ↑ For this purpose, Thomas Klein : SEW - The West Berlin unit Socialists. An “East German” party as a thorn in the flesh of the “front city”? Links, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86153-559-1 , pp. 45-55.

- ^ For the end of SEW, see Thomas Klein: SEW - Die Westberliner Einheitssozialisten. An “East German” party as a thorn in the flesh of the “front city”? Links, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86153-559-1 , pp. 292-296.

- ^ German Bundestag, printed matter, 12/7600, Bonn, p. 505 f. (PDF)

- ↑ Moral duty . In: Der Spiegel . No. 52 , 1989 ( online ).

- ^ Georg Fülberth: KPD and DKP. Two communist parties in the fourth period of capitalist development. Heilbronn 1990, ISBN 3-923208-24-3 , p. 133.

- ^ Georg Fülberth: KPD and DKP. Two communist parties in the fourth period of capitalist development. Heilbronn 1990, ISBN 3-923208-24-3 , p. 128.

- ↑ Overview of the results of the elections to the German Bundestag (1949–2002)

- ^ Georg Fülberth: KPD and DKP. Two communist parties in the fourth period of capitalist development. Heilbronn 1990, ISBN 3-923208-24-3 , pp. 131-132.

- ^ The last waltz . In: Der Spiegel . No. 49 , 1989 ( online ).

- ↑ 1979: DKP and SED full solidarity with the USSR. on: gruene-friedenszeitung.de

- ↑ Christian Siepmann: 40 years DKP: Revolutionaries from the row house. In: Spiegel Online . September 25, 2008, accessed December 30, 2014 .

- ↑ Uwe Klußmann: DON QUICHOTTES AT SANCHO PANSAS - In the race for voters, the radical left does not get going. In: Spiegel Special. January 1, 1994, accessed December 30, 2014 .

- ↑ Helmut Bilstein u. a .: Organized communism in the Federal Republic of Germany. DKP - SDAJ. - MSB Spartacus. KPD / KPD (ML) / KBW. 4th edition. Read, Opladen 1977, p. 26.

- ↑ Michael Jäger: How to force a socialism debate. In: Friday. March 22, 2002.

- ^ DKP party executive (ed.): The German bourgeoisie and 'Eurocommunism'. On the socialism and internationalism discussion. Düsseldorf 1977; Dieter Wenz: The DKP has difficulties with eurocommunist tendencies. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine. March 31, 1978 (PDF)

- ↑ Ulli Stang (Ed.): Sophie and Hans Scholl: 22 February 1942 murdered by Nazis. Edited by DKP Marburg, district group North Am Grün 9, Marburg 1983, pp. 8–12.

- ↑ Udo Baron : "Group Ralf Forster". The secret military organization of the DKP and SED in the Federal Republic. ( Memento from March 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: Germany Archive. 38 (2005), No. 6, pp. 1009-1016.

- ^ The secret combat force of the DKP ( Memento from July 1, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ mk: GDR trained the military arm of the DKP. In: FAZ.net , May 19, 2004, No. 116, p. 6.

- ^ Official final result of the 2009 Bundestag election , Bundeswahlleiter.de, accessed on October 15, 2009

- ^ "Risen from the ruins" - The rebirth of the DKP. In: Panorama .

- ↑ Local election 2009 Bottrop ( Memento from August 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Renate Lääts: Revolution among revolutionaries: 20th Congress rolls up around the DKP. March 26, 2015, accessed September 12, 2019 .

- ↑ ELP observer status ended «DKP news portal. Retrieved September 12, 2019 .

- ↑ www.kommunisten.de - Marxist left, partner of the EL. Retrieved September 12, 2019 .

- ^ "The party executive is destroying the DKP". In: www.kommunisten.de. Retrieved September 12, 2019 .

- ↑ SDAJ spin-off goes KO. June 13, 2018, accessed September 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Results Germany - The Federal Returning Officer. Retrieved September 12, 2019 .

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Baden-Württemberg 2019 , p. 250

- ↑ Federal Ministry of the Interior (ed.): Verfassungsschutzbericht 2016 . 2017, ISSN 0177-0357 , p. 122 ( Online [PDF; 3.8 MB ; accessed on January 15, 2018]).

- ↑ Ministry of the Interior NRW (ed.): Verfassungsschutzbericht of North Rhine-Westphalia on the 2016 . Düsseldorf September 2017, p. 134 ( Online [PDF; 9.0 MB ; accessed on January 15, 2018]). Online ( Memento from January 15, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ NRW Constitutional Protection Report 2007 ( Memento from September 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), p. 92. (PDF)

- ↑ NRW Constitutional Protection Report 2007, p. 94.

- ^ Constitutional Protection of Hesse: General information on the DKP ( Memento from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Statute of the DKP. 1st edition. 1993.

- ↑ DKP: program

- ↑ Armin Pfahl-Traughber : Hardly learned anything. The new DKP program in terms of extremism theory . on the website of the Federal Agency for Civic Education.

- ↑ In Berlin and Brandenburg: DKP wants to run for federal elections ( memento from September 9, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) In: redglobe.de

- ^ Statute of the DKP from 2018

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report 2009 ( Memento from July 4, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (from June 21, 2010) (PDF; 4.3 MB)

- ↑ DKP Nordbayern ( Memento from July 30, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Election results at www.wahlrecht.de

- ↑ Overview of the elections since 1946 on wahl.tagesschau.de. (Old versions: Landtag elections and Federal Council - stat.tagesschau.de ( Memento from August 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ 2010 CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTION IN BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG Constitutional Protection Report Baden-Württemberg 2010 (PDF; 3.8 MB)

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Bavaria 2010. ( Memento from July 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ↑ Unknown people have demolished the DKP shop window , on stopptantiantifa.blogsport.de

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Berlin 2010. ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 6.2 MB)

- ↑ DKP Berlin decides on the election program and candidacy for the House of Representatives elections ( memento from July 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on: redglobe.de , March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Brandenburg Constitutional Protection Report 2010 ( Memento from March 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 6.2 MB)

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Free Hanseatic City of Bremen 2010. ( Memento from February 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.4 MB)

- ↑ Constitutional Protection Report Hamburg 2011. p. 128. (PDF; 7.7 MB)

- ↑ Constitutional Protection in Hesse Report 2010 Constitutional Protection Report Hesse 2010 (PDF)

- ↑ "Axel Koppey new chairman of the DKP Hessen" , http://dkp-hessen.de/ of 15 September, 2015.

- ↑ Ministry of the Interior Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania - government portal ( Memento from July 26, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Lower Saxony Ministry of the Interior and Sport - Publications

- ↑ Information, documentation and archive, German Communist Party of Lower Saxony ( Memento from March 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), dkp-niedersachsen.de

- ^ Protection of the Constitution of North Rhine-Westphalia - German Communist Party ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ DKP Ruhr-Westphalia: Call for elections for the state elections in North Rhine-Westphalia in May 2010

- ↑ Press release of the DKP North Rhine-Westphalia: November 4, 2016

- ^ Ministry of the Interior of Rhineland-Palatinate - left-wing extremist parties and groups

- ^ Observation area left-wing extremism Saarland 2010

- ↑ Buy yourself a prime minister!

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Saxony 2009 ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 17 kB)

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Saxony-Anhalt 2010 ( Memento from February 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Schleswig-Holstein 2010 (PDF)

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report Thuringia 2010 ( Memento from September 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2.1 MB)

- ↑ 1st (constituent) party executive conference 23./24. March 2013 (PDF file)

- ^ Karl Liebknecht School of the DKP. In: karl-liebknecht-schule.org. December 7, 2014, accessed December 30, 2014 .

- ^ For example in Bremen a Bremer Rundschau, in Hanover a Hannoversches Volksblatt, in the districts Wesel and Kleve Rotes from the Lower Rhine, in the Hessian Friedrichsdorf a Taunus Echo for the Hochtaunuskreis, in Nordhorn a Rote Spindel (name refers to the lost textile industry), In Munich a left look, for the VW group Der Rote Käfer, for Voith AG in Heidenheim a turbine, in Brandenburg a Red Brandenburger, in Thuringia a Thuringia report .

- ↑ Bundestag printed matter 18/1080

- ^ German Bundestag (ed.): Drucksache 12/7600 . Bonn, S. 505 f . ( PDF, 195MB [accessed July 28, 2008]).

- ↑ Hubertus Knabe : Honecker's millions for a Trojan horse . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . October 9, 2008 ( faz.net [accessed January 2, 2016]).

- ^ In the communities against right-wing agitation. DKP Hessen, accessed on April 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Preliminary result of the local elections on September 11, 2016 in Lower Saxony. (PDF) Election supervisor from Lower Saxony, September 12, 2016, archived from the original on October 19, 2016 ; accessed on April 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Panorama: "Risen from Ruins" - The rebirth of the DKP

- ↑ In Berlin and Brandenburg: DKP wants to run for federal elections ( memento from September 9, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) In: redglobe.de May 4, 2009.

- ^ Neues Deutschland, February 25, 2008; young world, February 25, 2008; Our time, February 29, 2008.

- ↑ Rolf Priemer, Karl-Heinz Pawlitzki, Dieter Vogel, DKP Party Executive: 20th Congress of the German Communist Party - DKP. Retrieved March 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Renate Lääts: Revolution among revolutionaries: 20th Congress rolls up around the DKP. March 26, 2015, accessed March 10, 2018 .

- ^ Resignations from the DKP completed [Our time] . In: Our time . ( Unser-zeit.de [accessed on March 10, 2018]).

- ↑ End of the DKP's observer status with the Party of the European Left. In: DKP news portal. Retrieved March 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Statement by Anti-capitalist Left conference - International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine. Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ European Anticapitalist Left Declaration. November 28, 2005, accessed April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Communist Politics Network. In: www.kommnet.de. Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ↑ End of the EL observer status - report from the XXI party conference of the DKP. Website for news from the DKP. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ State elections and Federal Council at tagesschau.de ( Memento from August 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Results of the state elections in Baden-Württemberg from 1984 to 1996 ( Memento from March 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Results of the state elections in Baden-Württemberg 1996 to 2011 ( Memento from May 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Election results - Bavaria (state elections 2018 and earlier state elections). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Election results - Brandenburg (state elections). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Election results - Hamburg (state election). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Election results - Hesse (state elections 2018 and previous state elections). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Election results - Lower Saxony (state elections). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Election results - North Rhine-Westphalia (state elections). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Election results - Rhineland-Palatinate (state elections). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Election results - Saarland (state parliament election). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ^ Election results - Schleswig-Holstein (state elections). Retrieved April 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Results of the Bundestag elections ( Memento from July 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Results of the European elections ( Memento of July 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive )