Bavaria Party

| Bavaria Party | |

|---|---|

| Party leader | Florian Weber |

| Secretary General | Hubert Dorn |

| vice-chairman | Fritz Zirngibl Helmut Freund Helmut Kellerer Richard Progl |

| Country Managing Director | Uwe Hartmann |

| State Treasurer | Martin Progl |

| Honorary Chairwoman | Max Zierl , Andreas Settele |

| founding | October 28, 1946 |

| Place of foundation | Munich |

| Headquarters | Baumkirchner Str. 20 81673 Munich |

| Youth organization | Young Bavaria Federation |

| newspaper | Free Bavaria |

| Alignment |

Liberal Conservatism Federalism Regionalism Separatism Christian Democracy |

| Colours) |

White blue |

| Bundestag seats |

0/709 |

| Landtag seats |

0/205 |

| Seats in district days |

4/238 |

| Government grants | 199,614.90 euros (2018) (as of April 15, 2019) |

| Number of members | 6,238 (May 3, 2019) |

| Minimum age | 16 years |

| MEPs |

0/96 |

| European party | European Free Alliance (EFA) |

| Website | bayernpartei.de |

The Bayernpartei e. V. ( short name : BP ) is a state party in Bavaria and strives for the independence of the Free State.

BP regularly takes part in elections in Bavaria as well as in Bundestag and European elections. It is a member of the European Free Alliance (EFA). In political science, the Bavarian party is described as a “regionalist-separatist party with a conservative program”, “extremely federalist” and a “liberal party with conservative elements”. One of their political goals - in addition to strengthening civil rights and simplifying tax law - is the possibility of a referendum on Bavaria's exit from the German state association.

The Bavarian Party was represented by 17 members in the 1st German Bundestag . From 1954 to 1957 she was part of the coalition of four and from 1962 to 1966 through a coalition with the CSU in the Bavarian state government . When she left the Maximilianeum after the state elections in 1966 , she lost influence.

history

Founded in 1946 and successful in the first few years

The Bavarian Party was founded on October 28, 1946 in Munich by Ludwig Lallinger and Jakob Fischbacher , but not as a split from the CSU. The Radical Patriots of 1868 and the Bauernbund of 1893 can be regarded as their forerunners . The BP was only founded after the CSU, because the American occupying power granted it the license later. Licensing at the state level took place on March 29, 1948.

As a result, Bavarian conservatives, monarchists and separatists gathered in the BP , including the founder of the Harnier circle , the former resistance fighter Heinrich Weiß . In addition, there were disappointed CSU members, including most prominent Joseph Baumgartner , who became the actual leading figure in January 1948. Between 1948 and 1950 the party was able to benefit from an internal crisis in the CSU.

In the election campaigns, the Bavarian Party used short, sharp slogans. The medium-sized, peasant and liberal party saw itself as the only really Bavarian party and demanded the independence of the Bavarian Free State. Initially, the BP propagated the idea of a state that is independent under international law. After Bavaria became a member of the Federal Republic in 1949, it relied on a strong federalism.

The first elections in which the Bavarian Party took part were the local elections on May 30, 1948. It provided 153 city councils in independent cities (CSU: 307) and 309 district councils in rural districts (CSU: 2642). In the local elections that followed, on March 30, 1952, it was even able to improve the balance of power with the CSU in some cases, but it always remained well behind the CSU.

In the state elections in 1950, the Bavarian party won just under 18 percent of the vote.

After 1948 the federal election of 1949 followed , in which the BP came to 4.2% nationwide. Since the five percent hurdle in this election only applied per federal state, her share of the vote in Bavaria was 20.9% and she also won several direct seats, she moved into the Bundestag with 17 seats. There she worked with other regional parties to achieve parliamentary group status ( Federal Union , 1951–1953). After that, the party no longer made it to the Bundestag: in 1953 it had 9.2 percent in Bavaria, but the five percent hurdle applied nationwide, in 1957 it was 3.2% for the Federal Union.

Election losses since 1950

The Bavarian Party had its main focus in old Bavaria: in Lower Bavaria, Upper Bavaria and the Upper Palatinate. Despite its slogan “Bayern den Bayern”, it was hardly recognized as a Bavarian state party. In Catholic circles one turned against a splitting of Catholic votes on the CSU and BP. The clergy preferred the CSU. The decline of BP began with the consolidation of the Federal Republic, which decided the state and international legal status of Bavaria. The federal and state elections of the 1950s were characterized by steady decline in votes. In addition, there was the alleged involvement of the Bavarian party in the so-called casino affair . The casino affair was mainly driven by the CSU. In the end, this affair was mainly used by the CSU and one reason why the CSU was able to rise to become the dominant political force.

After 17.9 percent in the 1950 state elections, it was followed by 13.4 percent in the 1954 election and 8.1 percent in 1958 . The 1962 election was the last in which she still received seats - with 4.8 percent. In Bavaria, the party was the third strongest force until 1958.

The CSU decided in 1950 to form a coalition with the SPD , which embittered the BP. When the CSU achieved strong profits in the Bundestag election in 1953 , while BP had lost all direct mandates and was no longer elected to the Bundestag, many conservative BP members converted to the CSU. The result was a strengthening of the more liberal and indeed Catholic but anti-clerical forces in the BP, which in turn made the party more interesting for the SPD. In fact, it formed the state government from 1954 to 1957 with the SPD, the BHE party for expellees and the FDP . Baumgartner became Deputy Prime Minister. This ideologically and economically very colorful alliance was only possible because at that time cultural policy was in the foreground and all four parties were opposed to the CSU and the Catholic Church that was close to it. In addition, the BP politicians aspired to the government and wanted to return the favor for the rejection by the CSU in 1950. The alliance broke up in 1957, and the BP was the target of the investigation into the so-called casino affair .

Casino affair

After 1958, the strategic stance towards the CSU divided the supporters. Should the BP continue to differentiate itself from the CSU or should it make a coalition offer, possibly even calling for the election of the CSU at the federal level?

In 1959, the CSU hit a decisive blow against the competition from the Bavarian Party. Part of the BP party leadership was sentenced on August 8 in the so-called " casino affair " for false testimony on oath to considerable penal sentences, which the CSU knew how to use for its media. But even the former CSU Prime Minister and Justice Minister Hans Ehard later called this judge's verdict “a barbaric judgment”: “The two politicians in the investigative committee were allowed to swear on trivial matters. It doesn't really matter whether someone wore yellow boots or red ones. ”The CSU had previously collected incriminating material against the BP and was involved in the opaque exposure of the case.

A witness reported under oath on a conversation between the casino candidate Karl Freisehner and the then CSU general secretary Friedrich Zimmermann , which he overheard in a Salzburg hotel in 1958: Zimmermann had promised Freehner roulette concessions at that time if he declared the Bavarian party with a voluntary report -Guide burden. A short time later, Zimmermann was also sentenced to a (comparatively low) prison term of 4 months for perjury in the first instance . However, this judgment was overturned in the second instance because Zimmermann had a blackout due to hypoglycaemia in the decisive phase of his testimony against the Bavarian party, according to an expert who was subsequently brought in. In its overall assessment of the hearing, however, the court stated: "There can be no question of the defendant's innocence being proven ...". According to the Spiegel , Zimmermann himself commented on the expert : "This was named by my defense, I saw him for the first time in the courtroom."

The clarification of the affair over the years (particularly through Der Spiegel ) came too late to stop the party's decline in the years that followed. After the BP had barely overcame the then applicable hurdle of 10 percent in an administrative district in Lower Bavaria in the 1962 state elections and had entered the state parliament with eight members, it formed a government alliance with the CSU, which had a narrow absolute majority in the state parliament. In the government she was only represented by the State Secretary in the Interior Ministry Robert Wehgartner . Wehgartner joined the CSU in 1966. The BP was also marginalized by other transfers by members of the state parliament and no longer entered the state parliament in 1966 (7.3% in Lower Bavaria, 3.4% in the state).

The Road to the Small Party (1966–1978)

With the departure from the Bavarian state parliament, the loss of supra-regional political importance followed, which also contributed to splits from BP. In 1967, party chairman Kalkbrenner and his supporters left the Bavarian party after trying unsuccessfully to initiate a reform process in the party. He founded the Bavarian State Party (BSP) .

For the first time since 1957, the Bavarian Party took part in federal elections in 1969 with a state list , but only achieved 0.9 percent of the valid votes cast in Bavaria. As a result, the Bavarian party tried to open up new constituencies. In the state elections in 1970 , various prominent politicians from other parties who had fallen out with them or were no longer elected entered the Bavarian Party's lists. Due to the highly personalized state election rights in Bavaria , personality votes should be gained, which also count for the list and are therefore decisive for the distribution of seats. This was shown, among other things, in the fact that posters and advertising material aimed at the people to an unusually high degree, while the Bavarian party tried to score points with topics in practically all elections before and after. Conversely, these candidates hoped that they could keep their mandates . However, this calculation did not work out for both sides, the BP clearly missed the entry into the state parliament with 1.3 percent. The percentage of votes had thus fallen to a little more than a third of the 1966 value. Some of the applicants therefore went back to their respective previous party. However, the split-off competition from the Bavarian State Party remained completely unsuccessful with 0.2%.

The election of Paula Volkholz , wife of Ludwig Volkholz , as district administrator in Kötzting in 1970 was more of a success for the “political family group Volkholz” ( Die Zeit ) than for the Bavarian party . The election result attracted nationwide attention, as it made Volkholz the first district administrator in Bavaria and the second woman in Germany to be promoted to the executive chair of a district. She was a candidate for the non-partisan electoral group “Equal Rights for All”, which her husband had founded especially for this election. She was also nominated by the Bavarian Party, whose deputy state chairman was Ludwig Volkholz at the time. Their office expired as early as 1972 with the territorial reform in which the district was dissolved.

The local elections of 1972 represented the absolute low point in the history of the party. It lost all seats in the independent cities and could only have two district councilors in all of Bavaria.

The 1974 state election relegated the BP to a splinter party with a result of 0.8% of the vote.

When the deputy state chairman Ludwig Volkholz was surprisingly not elected as state chairman at the state party conference in Regensburg, he left the Bavarian Party with a number of other members in order to subsequently establish the right-wing Christian Bavarian People's Party (Bavarian Patriot Movement) (CBV) .

Shortly before the dissolution (1978/79)

With the establishment of the Bavarian State Party in 1967, the Bavarian Party had lost around 30% of its members, which is why at that point a liquidation of the party was already being considered, but half of the members who had left the party returned to the Bavarian Party in 1970. However, after the result of the 1978 state elections had resulted in another loss of around 15,000 voters and a level of only 0.4%, and since the local elections in 1978 there had been no BP representatives in district assemblies, the Bavarian party was back in early 1979 shortly before the dissolution. There were hardly any active members left. The weekly newspaper Die Zeit characterized the party's ability to organize as “less than that of a Schuhplattler club”. In addition, debts from the state election campaign of 1970 of almost 143,000 marks. The decision to dissolve the party was scheduled for March 1979. The motion submitted by party chairman Rudolf Drasch to dissolve the party was rejected by the majority of the delegates at the regional party conference in 1979. Drasch made his office available, Max Zierl was elected as his successor, the rest of the board remained in office.

Bavarian Party from 1980

In the 1980s there was a certain consolidation at a low level, which was also expressed in the reintegration of the CBV and its chairman Ludwig Volkholz in 1988. A calming of the situation was also evident in the continuity through the long terms of office of the chairmen Max Zierl (1979–1989) and Hubert Dorn (1989–1999). From 2003 to 2017, the BP recorded votes in all elections.

Controversial issue of separatism

For the period after 1979, Uwe Kranenpohl states that the “militant defense of Bavarian statehood” is a contentious issue within the Bavarian party. In the basic program, updated in 1993, the demand for an "independent Bavarian state in a European confederation" was laid down for the first time. In 1994, the former chairman and honorary chairman of the party, Rudolf Drasch, left the party. Even if Drasch justified this step, among other things, with the fact that under Dorn, “absolute Bavarian separatism had become the top political guideline”, this radical demand was already party doctrine under his predecessor. "Bavaria must become independent again, away from those in Bonn who are to blame for the lousy prices for agricultural products, for drugs, to blame for fornication and unemployment," Die Zeit quoted the then party chairman Zierl in June 1981 and noted that the " white-blue dwarf still at one stroke ”understand.

For German reunification , the Bavarian party sought a popular lawsuit before the Bavarian Constitutional Court , but this was rejected. The party had expressed the opinion that Bavaria had rejected the Basic Law in 1949 and thus had not become part of the Federal Republic.

Participation in elections 1980–2003

The party regularly competes in the elections to the Bavarian state parliament, since 1987 to the German Bundestag and since 1984 to the European Parliament. In 1983, participation in the early federal elections was planned, but the necessary support signatures could not be provided.

In the 1994 European elections , BP won 1.6 percent of the vote in the Free State. This was the best result in regional elections since 1966. In the 2009 European elections , the party attracted nationwide media coverage with a satirical advertising poster that was only used outside of Bavaria. The central statement “Don't you want to get rid of Bayern too? Then the Bavarian party "elected the media in the Free State to mockery or assessments such as" bizarre election advertising "and" most bizarre European election poster ".

The popularity of federal elections was and is significantly lower. After the party had received its worst result at Bavarian level since it was founded with almost 10,000 votes (0.1% of the valid votes) in the 2002 Bundestag election , it was able to reduce its share of the vote in Bavaria to 0 at the early 2005 Bundestag election , Increase by 5% and with over 48,000 second votes in the 2009 Bundestag election (0.7%) as well as in absolute terms, still at a low level, the highest result in Bundestag elections since 1969 .

The party was most likely to stabilize in the state elections and from the 1990s to 2003 it achieved results just under or over 1%. In Bavaria, the district days are elected at the same time as the state parliament . There is no threshold clause , so that the Bavarian party was represented by a member of the Upper Bavarian District Assembly from 1990 to 2003 .

At the municipal level, the party had again been represented sporadically in district assemblies since 1984 and increased its parliamentary representation, albeit at a very low level, from 5 district councils in 1984 to 15 in 2002.

Development since 2003

In the 2008 local elections , the Bavarian party - which continues to run only sporadically - achieved a nationwide result of 0.4 percent. It received 15 mandates in the district councils and for the first time since 1966 set up a city council in Munich . In district-dependent municipalities, she succeeded in gaining 13 mandates through its own lists and nine through joint election proposals.

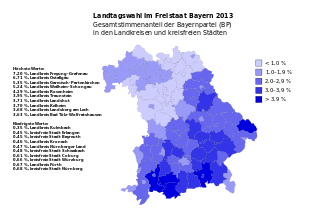

In the 2008 state elections , participation in state party funding was made possible when the 1.1 percent figure was reached. In 2013 , the Bavarian party more than doubled its number of votes compared to 2008 and achieved its best election result since 1966 with 2.1%. In the old stronghold of Lower Bavaria it achieved 3.2%.

The elections for the district days were also very successful for BP in 2013. In addition to Upper Bavaria , where it was already represented by a member, it now sent representatives to three additional district days. In Upper Bavaria it reached 4.27%, gained 2 seats and gained parliamentary strength with 3 seats in the district assembly.

The 2013 federal election brought the party, compared to 2009, an increase of around 9,000 votes and (based on Bavaria) 0.2 percentage points and thus a result like the last one in 1969, but less than half of the voters of the week before decided conducted state election also in this ballot for the party.

For the 2014 local elections , BP ran in twelve districts and two urban districts (Munich and Landshut ) and moved into their parliaments. The city council mandate in Munich was kept short with losses, in the other areas the BP gained significantly in some cases. Their number of mandates in counties and urban districts rose from 16 to 36 and their nationwide share of the vote to 0.6 percent. For the first time in 54 years, BP won mandates in Lower Franconia. In March and April 2016, two city councilors of the CSU , one of the Free Voters and a member of the Bavarian Party who was elected for the SPD and then for some time independent , joined the Munich party. An LKR deputy followed in January 2019 , so that the BP city council faction with six members became the fourth largest in the Munich city council after the Greens .

In the 2017 Bundestag election , the number of second votes for BP remained at the level of the previous 2013 election. However, due to the higher turnout, the proportion of votes fell by 0.1 percentage points to 0.8% (based on Bavaria).

The 2018 state election brought losses to the party; however, with 1.7% of the total vote, it stayed at a level that ensured further state funding. The BP also lost votes in the elections for the district days; Since 2018 it has only been represented in three instead of the previous four district days.

In the 2020 local elections , BP was able to move back into all committees in which it was previously represented and even win seats in another district council ( Deggendorf ). Some of them recorded considerable losses and only had 28 instead of 36 members in the councils of the independent cities and in the district assemblies.

Content profile

In the early years, the Bavarian party was primarily anti-Prussian and Bavarian-particularist orientated, a political-ideological basis that went beyond this did not exist or only existed in conflicting party wings. In later years the party was seen as conservative to reactionary, in more recent times it has been seen programmatically more as liberal with conservative elements, and with regard to the Bavarian statehood as separatist.

Programmatic principles

In its basic program “Courage to Freedom” - decided in 1981, updated in 1994 - the Bavarian Party positions itself as a party with Christian - conservative ideas: “It is not acceptable to 'liberalize' basic norms of our legal system just because some of the citizens are no longer is willing to accept it. ”In the early years in particular, the Bavarian Party - in contrast to the CSU - marked a clear distance from the Christian churches, while the CSU primarily sought proximity to the Roman Catholic Church . However, the party criticized, for example, the rejection of the Pope's visit in 2011 by large parts of the Bundestag as intolerant. Some programmatic statements (e.g. Sunday driving ban, protection of Christian holidays, protection of unborn life in the 2008 state election program) and the party's choice of words are also influenced by Christian values.

In its current “White-Blue Principles” - decided in 2011, updated in 2017 - the Bavarian Party positions itself as a regionalist party: “In deep concern and in full awareness of the increasing erosion of the statehood of Bavaria and the federal state and social order in Germany and In Europe, the Bavarian Party sees it as its foremost task to cultivate the Bavarian state consciousness and democratic principles and to defend them against the burgeoning centralism. "

Desired state structure

The Bavarian Party calls for an elected head of state for the independent state it is striving for: “Experience shows that a state president who stands above party-bound day-to-day politics can often intervene and give important impetus through his reputation alone. The Bavarian Party is therefore campaigning for a democratically elected President in the Free State. ”The BP rules out a return to the hereditary monarchy. At the same time there are contacts to traditional associations that are close to the Wittelsbachers .

The prime minister should be elected directly by the people, which is a middle ground between parliamentary and presidential democracy.

Furthermore, the Bavarian Party would like to convert Bavaria from a unitary to a federal state, in which the three tribes of the Bavarian , Franconian and Swabian tribes (after the separation of the Rhine Palatinate by the Allies in 1946) are to be given a greater life of their own.

Regionalization

The dominant political goal of the Bavarian Party is to regain full sovereignty of the Bavarian state, similar to the secessionist efforts in Scotland, Catalonia and Flanders. Until then, “every attack and encroachment on the state sovereign rights of Bavaria must be combated with all possible means”. The demands for regionalization, which appear in almost all political fields, should be seen from the point of view of gradual decoupling from the Federal Republic. This demand for regionalization is currently very popular in large parts of Europe. The examples of Scotland, Catalonia and Flanders lead to a certain resurgence of the Bavarian party. The Bavarian party also benefits from the various CSU affairs. The Bavarian Party does not differentiate between federal and state politics.

In many of its programmatic standpoints, the Bavarian Party calls for a strengthening of Bavarian personal responsibility and the return of important political powers. In European terms, she advocates a Europe of the Regions , she is a member of the European Free Alliance , a party of the European Parliament.

Participation in referendums and referendums

Bavaria leaves the Federal Republic

The main goal of the Bavarian Party is a Free State of Bavaria that is independent of the Federal Republic of Germany . The statutes (Section 9, Paragraph 2, No. 2) stipulate that it must be excluded "whoever acts or speaks against the statehood and state independence of Bavaria". Statements on daily politics also contain references to or refer to Bavaria's subsequent independence. In 2009, the chairman Florian Weber announced a referendum in the Mittelbayerische Zeitung with the aim of establishing Bavaria's independence by 2020. By April 2015, 7,050 of the 25,000 signatures required to initiate a referendum had been collected. The exit is justified financially, but also historically. According to a study from 2011, 39% of Bavarians - regardless of whether they are from old Bavaria, Franconia or Swabia, locals or newcomers - want more independence for the Free State. The number of supporters of a Free State independent of the Federal Republic has even increased in recent years. The Bavarian Party's constitutional complaint about the implementation of a Bavarian independence referendum was not accepted for decision in 2016. The Federal Constitutional Court does not see the states as “masters of the Basic Law ”. There is therefore no room for secession efforts by individual countries.

Rejection of smoking bans

In 2010, the Bavarian Party was the only party to support the “Action alliance 'Bavaria says no!' Which is mainly financed by the tobacco industry and tobacco wholesalers. for freedom and tolerance ”. This initiative wanted to achieve a rejection of the popular initiative “For real non-smoker protection!” - a project that clearly failed. From the ranks of the party, a referendum “Yes to 'freedom of choice for guests and hosts'” was initiated in 2012, which in fact aims to withdraw the popular referendum, which was successful in 2010. The Bavarian Party justifies its negative stance on the protection of non-smokers through smoking bans primarily with the self-determination of the hosts and guests.

Petitions to the Bavarian State Parliament

Introduction of a basic education salary

At the beginning of June 2012, the Bavarian Party initiated a petition to the Bavarian State Parliament calling for the introduction of a basic education salary. In addition to child benefit, it is to be paid out to parents who do not use state childcare services. The parenting salary depends on the child's income and age. According to the Bavarian Party model, the parent who renounces an employment relationship to look after the child should receive up to 100 percent of the previous net income for pre-school children and up to 50 percent for school-age children. The higher the net income, the higher the basic education salary. There is no provision for a component for social balance. The basic education salary is to be financed by discontinuing the previous benefits and allowances for children, over which the state parliament, however, has no influence. So far the petition has not been submitted.

ESM without Bavaria

The party initiated another petition at the beginning of July 2012. In this, the Bavarian state parliament is called upon to “ fight Bavaria's liability from the ESM with all available means”. She fears that the federal government will have unlimited liability for the debts of other states and that the resulting burdens will be passed on directly and indirectly to the federal states. The Bavarian party had already expressed criticism of the ESM several times and called for participation in a demonstration in Munich against the ESM. The petition has not yet been submitted.

Other political positions

Prevent a surveillance and prohibition state, protect civil rights

The Bavarian party speaks out in its program "Ten points in white-blue" against a total surveillance state. In the opinion of BP, PC, video and telephone surveillance should only be possible if there is justified, urgent suspicion. In the opinion of BP, the privacy of citizens can only be violated if it is used as a protective cover for serious crimes. In its program, the BP rejects the nationwide collection and storage of biometric data and fingerprints as well as the transfer to other countries (e.g. to the USA) on both a national and a European level. The Bavarian Party sees a major problem in the "tendency [of the state] to regulate and restrict the behavior of citizens more and more".

Financial, economic and social policy

Many of the Bavarian Party's demands are aimed at decoupling Bavaria from the federal economic, financial and social systems. This also includes the proposal to regionalize the health and social system. Both the solidarity surcharge and state financial equalization are to be abolished.

In place of the previous commuter lump sum , a lump sum for distance costs is to be used, which is deducted directly from the tax liability. The aim is to achieve tax relief that is independent of the individual tax progression. The assessment basis for the flat rate is the average fuel price for the tax year. A statement about counter-financing is not available.

Social policy statements by the Bavarian party mainly concern the family sub-area. The party is opposed to state care offers. It relies on increased support for parental upbringing in the form of a basic parenting salary. A care allowance of 150 euros per month is considered insufficient. An increase in the retirement age is rejected as this would only lead to reductions in earnings.

The Bavarian party rejects “equating marriage-like relationships and marriages ”.

Environmental and agricultural policy, animal welfare

The Bavarian Party sees environmental protection as one of the major political challenges to preserve home and livelihoods. In contrast, the restriction of civil liberties for environmental reasons is viewed critically. Humans should be perceived as part of the environment and not as intruders into it.

Renewable energies are to be promoted, but the energy transition is to be managed in a decentralized manner. The eco-tax and environmental zones in city centers are to be abolished.

Further demands are agricultural direct marketing, consumer protection through designations of origin, a ban on animal meal and agricultural factories . Instead, small and medium-sized farms are to be supported. The BP calls for a ban on animal transports and "nonsensical" animal experiments .

Domestic politics and justice

Free legal assistance for crime victims is to be made possible, as is the promotion of European and international cooperation. Federalism within Bavaria is to be strengthened in line with the principle of subsidiarity . This should be done in particular by upgrading the local self-government of the communities and districts; the districts are to receive their own legislative powers. The Bavarian Party campaigns for a directly elected Prime Minister and, although there are friendly ties to monarchist groups, for a democratically elected President.

Defense, Foreign and European Policy

The Bavarian party speaks out against foreign deployments of the Bundeswehr. The focus is on the financial aspect of such operations. The Bundeswehr also appears as a cost factor in the argument for an independent state of Bavaria.

In foreign policy, Turkey's admission to the European Union is rejected. In a press release, this was mainly justified with excessive financial demands on the EU.

The party has been committed to a "United Europe" since 1948, but does not define this term any further. At the same time, she criticizes the transfer of competencies to European institutions. She emphasizes the - legally controversial - primacy of the fundamental rights of the national constitutions over EU law . At the state party conference on October 30, 2011 in Bamberg, the Bavarian Party advocated Germany's exit from the euro. After the establishment of an independent state of Bavaria, its own currency is to be introduced.

Cultural and educational policy

The party speaks out in favor of expanding the educational sovereignty of the federal states . It rejects federal influence, including in the form of payments to the federal states. An alignment of the school systems within Germany is rejected.

The tripartite school system is to be retained, but the secondary school is to be upgraded through professional internships. Schooling close to home should also be made possible in rural areas. Bavaria should ensure that the university offers its students freedom of choice. BAföG benefits should be paid independently of parents, tuition fees are rejected.

The Bavarian Party emphasizes the "historically grown cultural differences within Germany" and rejects a "German dominant culture". The imparting of cultural knowledge through local history lessons is understood as a means of integration . The Bavarian dialects should be preserved and cultivated.

organization

Political direction

Party congress

The highest political organ is the party congress. In the party's publications, it is often referred to as the state party conference. It is held as a general meeting. The number of participants and the composition is therefore heavily dependent on the place and date. Its most important tasks are the election of the state board, the appointment of honorary members and decisions about political principles. The party congress can theoretically take on any authority.

Party committee

The party committee corresponds to the “small party congress” of most other parties. It is formed from the delegates of the district associations and the Young Bavaria Association as well as the members of the party leadership. The party committee elects its own chairman and his deputy. It is the highest body between the party congresses and takes on its tasks as long as these are not explicitly reserved for the party congress.

Party leadership

The party leadership is a specialty of the Bavarian party. It consists of the party executive committee, the honorary chairmen, the eight delegates from the district associations and a representative of the youth organization. If there are parliamentary groups in the federal, state or district parliaments, these also each have a seat with a vote. The main task of the party leadership is to coordinate the political work of the subdivisions and to approve the financial budget.

Party executive

The party board of the regional association consists of the chairman, his four deputies, the treasurer, the secretary and the general secretary. The board can co-opt any number of members and non-members. However, these have no voting rights. The state executive is responsible for ongoing party business. He represents the party legally externally.

| Chairman | Florian Weber |

| vice-chairman | Helmut Freund, Helmut Kellerer, Richard Progl, Fritz Zirngibl |

| Treasurer | Martin Progl |

| Deputy Treasurer | Harald Eberhard |

| executive Director | Uwe G. Hartmann |

| Secretary General | Hubert Dorn |

| Deputy Secretary General | Christiane Zeigler |

| Secretary | Georg Weiss |

| Deputy Secretary | Thomas Pepper |

| Party committee chairman | Andreas Settele |

Party leader

What is unusual is the strong position of the party chairman, anchored in the statutes, called the state chairman in the statutes . For example, § 52 stipulates "The state chairman is the appointed spokesman for the party." And § 52 Paragraph 1 specifies "For the announcement of party official declarations, resolutions, statements or reports on current political or internal party issues to the press, radio and television or to third parties The state chairman is responsible for persons who do not belong to the party. ”In the case of other parties, these rights normally belong to the board in its entirety.

Regional breakdown

The Bavarian Party is divided into a total of eight district associations: The district associations Upper Franconia , Middle Franconia , Lower Franconia , Swabia , Upper Palatinate and Lower Bavaria are congruent with the respective Bavarian administrative districts. The district association of Munich comprises the state capital Munich , the district association of Upper Bavaria the remaining administrative district of the same name. In addition, there are district and local associations, but not all of them are active.

The chairpersons of the district associations at a glance:

| Middle Franconia | Peter Rinke | Munich | Alexander Hilger |

| Lower Bavaria | Anton Maller | Upper Bavaria | Hubert Dorn |

| Upper Franconia | Christiane Zeigler | Upper Palatinate | Michael Prensky |

| Swabia | Helmut Kellerer | Lower Franconia | Uwe Hartmann |

Party press

The Free Bavaria press organ appears four times a year. This newspaper was first published in 1952, but has not appeared continuously since then. From 1949 to 1954, the “Bayerische Landeszeitung” appeared with an initial circulation of 65,000 copies. This weekly was primarily planned as a party-affiliated general-interest newspaper, comparable to the CSU's Bayernkurier , but it incurred considerable losses, which ultimately led to its discontinuation. The “Bayernruf”, which appeared biweekly from 1951 to 1960, however, was more aimed at the party's own members.

Social media

The party is very active on social media, e.g. B. on Facebook with well over 40,000 followers. Here it is even in third place among the parties in Bavaria, behind CSU and AfD.

Youth organization

The party's youth organization is the Jungbayernbund e. V. (JBB) based in Munich. It was founded at the state level in 1950, after regional foundings had already existed since 1948, and sees itself as the "Association of Franconian, Swabian and Bavarian youth in the Free State". The Jungbayernbund (JBB) is a member of the Ring Politischer Jugend (RPJ) Bayern. The chairman of Jungbayern has been Mario Gafus since July 14, 2019, his predecessor, Helmut Freund from Frasdorf, was appointed honorary chairman on July 14, 2019, his predecessor, Richard Progl from Munich, on February 21, 2015. The young Bavarians see themselves the committed to the Bavarian constitutional tradition and strive to realize the principle of self-determination of the peoples.

| Chairman | Mario Gafus |

| vice-chairman | Bastian Andrelang, Marina Ettl, Oliver Hess, Andreas Zimmer |

| Financial representative | Alexander Wertatschnik |

| Secretary General | Bernhard Neumann, Deputy Thomas Pfeffer |

| Secretary | Alexander Hilger, Deputy Florian Geisenfelder |

| Honorary Chairwoman | Helmut Freund, Richard Progl |

| State Committee Chairman | Thomas Mayr, Deputy Bernd Hoffmann |

Participation in elections and votes

Participation in referendums

In addition to participating in elections, the Bavarian Party also uses the means of popular legislation . In 1988 she tried to initiate a referendum against the nuclear reprocessing plant in Wackersdorf , which, however, turned out to be illegal. In 1991 she supported the referendum “The Better Garbage Concept” and in 1995 the referendum “More democracy in Bavaria: referendums in municipalities and districts” . These were directed against decisions of the CSU majority in the state parliament. In 1997 the Bavarian Party fought together with the CSU against the popular initiative "Lean State without Senate" to prevent the abolition of the 2nd Chamber in Bavaria . In 2008 it was the only party to support the campaign alliance “Bavaria says no!”, Which opposed the popular initiative “For real non-smoker protection!” .

Election results since 1946

| Election year | State election of Bavaria |

Bundestag election (share of second votes in Bavaria) |

European elections (share of votes in Bavaria) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 0.9% | ||

| 2018 | 1.7% | ||

| 2017 | 0.8% | ||

| 2014 | 1.3% | ||

| 2013 | 2.1% | 0.9% | |

| 2009 | 0.7% | 1.0% | |

| 2008 | 1.1% | ||

| 2005 | 0.5% | ||

| 2004 | 1.0% | ||

| 2003 | 0.8% | ||

| 2002 | 0.1% | ||

| 1999 | 0.4% | ||

| 1998 | 0.7% | 0.4% | |

| 1994 | 1.0% | 0.6% | 1.6% |

| 1990 | 0.8% | 0.5% | |

| 1989 | 0.8% | ||

| 1987 | 0.4% | ||

| 1986 | 0.6% | ||

| 1984 | 0.6% | ||

| 1982 | 0.5% | ||

| 1978 | 0.4% | ||

| 1974 | 0.8% | ||

| 1970 | 1.3% | ||

| 1969 | 0.9% | ||

| 1966 | 3.4% | ||

| 1962 | 4.8% | ||

| 1958 | 8.1% | ||

| 1957 | 3.2% 1 | ||

| 1954 | 13.2% | ||

| 1953 | 9.2% | ||

| 1950 | 17.9% | ||

| 1949 | 20.9% |

Mandates in district days

The Bavarian Party sent or sent representatives to the following district days :

| Administrative district in Bavaria: |

District election 2018 Bavaria Party seats: |

District elections 2013 Bavaria Party seats: |

District elections 2008 Bavaria Party seats: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Bavaria | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Lower Bavaria | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Swabia | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Upper Palatinate | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Party leader

| Period | Surname |

| 1948-1952 | Joseph Baumgartner |

| 1952-1953 | Jakob Fischbacher |

| 1953 | Anton Besold |

| 1953-1959 | Joseph Baumgartner |

| 1959-1963 | Joseph Panholzer |

| 1963-1966 | Robert Wehgartner |

| 1966-1967 | Helmut Kalkbrenner |

| 1967 | Simon Weinhuber 1 |

| 1967-1973 | Hans Höcherl |

| 1973-1976 | Franz Sponheimer |

| 1976-1979 | Rudolf Drasch |

| 1979-1989 | Maximilian Zierl |

| 1989-1999 | Hubert Dorn |

| 1999-2001 | Hermann Seiderer |

| 2001-2002 | Jürgen Kalb |

| 2002-2007 | Andreas Settele |

| since 2007 | Florian Weber |

Group leader in the Bavarian state parliament

| Period | Surname |

| 1950-1954 | Joseph Baumgartner |

| 1954-1957 | Carljörg Lacherbauer |

| 1957-1960 | Jakob Fischbacher |

| 1960 | Joseph Panholzer |

| 1960-1963 | Karl von Brentano-Hommeyer |

| 1963-1966 | Joseph Panholzer |

See also

literature

- Andreas Eichmüller: The Jagerwiggerl: Ludwig Volkholz; Forester, politician, folk hero. Mittelbayerische Dr.- und Verl.-Ges., Regensburg 1997, ISBN 3-931904-11-3

- Doris Fuchsberger, Albrecht Vorherr: Nymphenburg Palace under the swastika. Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-86906-605-9 .

- Uwe Kranenpohl, Bayernpartei In: Frank Decker (editor), Viola Neu (ed.): Handbook of German political parties , Wiesbaden, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2007, ISBN 3-531-15189-4

- Alf Mintzel : The Bavarian Party. In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook , Volume 2. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1986 (1983), pp. 395-489, ISBN 3-531-11838-2

- Ilse Unger: The Bavarian Party. History and structure 1945–1957. German Verl.-Anst., Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-486-53291-X

- Bernhard Taubenberger: Light across the country, The Bavarian coalition of four 1954–1957. Buchendorfer-Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-934036-89-9

- Christoph Walther: Jakob Fischbacher and the Bavarian Party . Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-8316-0406-7

- Konstanze Wolf: CSU and Bavaria party - a special competitive relationship. Verl. Wiss. und Politik, Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-8046-8606-0

Especially on the casino affair and the role of the BP and CSU in it

- Heinrich Senfft: Happiness is possible. The Bavarian casino trial, the CSU and the unstoppable rise of Doctor Friedrich Zimmermann. A political lesson. Kiepenheuer and Witsch, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-462-01940-6 ; Droemer Knaur, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-426-04050-6

- Meet at Café Annast . In: Der Spiegel . No. 42 , 1955 ( online - 12 October 1955 ).

- The donation roulette . In: Der Spiegel . No. 22 , 1959 ( online - May 27, 1959 ).

- White cuffs . In: Der Spiegel . No. 6 , 1960 ( online - Feb. 3, 1960 ).

- The perjury trap . In: Der Spiegel . No. 10 , 1960 ( online - Mar. 2, 1960 ).

- So-called white vest . In: Der Spiegel . No. 37 , 1970 ( online - Sept. 7, 1970 ).

- Fools eaten . In: Der Spiegel . No. 39 , 1970 ( online - Sept. 21, 1970 ).

- Tremendous power . In: Der Spiegel . No. 30 1971 ( online - 19 July 1971 ).

- Three little pieces of paper . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 1974 ( online - 22 April 1974 ).

- Acted like the Sicilian Mafia . In: Der Spiegel . No. 33 , 1988 ( online - Aug. 15, 1988 ).

Web links

- Web presence of the Bavarian Party

- Official party newspaper "Free Bavaria"

- BR: Bayernpartei - the name says it all

- BR: Bavarian Party - Topics and Positions ( Memento from September 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Minutes, reports, manuscripts, election and speaker materials, correspondence of the Bavarian Party 1897–1945, 1945–1972 (ED 719) in the archive of the Institute for Contemporary History Munich-Berlin (PDF, 3.4 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Board of Directors. In: bayernpartei.de. Retrieved August 28, 2018 .

- ^ Isabelle Borucki: Bavarian Party (BP). May 3, 2019, accessed July 22, 2020 .

- ↑ General overview of the determination of state funds for 2018 (PDF), as of April 15, 2019

- ↑ Imprint. In: bayernpartei.de. Retrieved September 25, 2018 .

- ^ A b Johannes Reichart, Bayerischer Rundfunk: Small parties before the state elections in Bavaria. In: BR.de. September 18, 2018, accessed September 25, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c Uwe Kranenpohl: Bavaria Party. In: Frank Decker (editor), Viola Neu (ed.): Handbook of German parties. Wiesbaden, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2007, p. 166

- ^ A b Hubensteiner: Bayerische Geschichte , Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, 17th edition 2009, pp. 488–489.

- ↑ a b Kreikenbom / Neu, Small parties on the rise: On the change of the German party landscape, 2013.

- ^ Bernhard Taubenberger: Cabinet Hoegner II, 1954–1957 . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria . Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Alf Mintzel: Bavaria Party . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here p. 397, p. 399.

- ↑ Alf Mintzel: Bavaria Party . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here pp. 398/399.

- ↑ Alf Mintzel: Bavaria Party . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here pp. 416/417.

- ↑ Alf Mintzel: Bavaria Party . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here pp. 405/407.

- ^ Election results according to Alf Mintzel: Bayernpartei . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here p. 446, p. 451.

- ↑ Alf Mintzel: Bavaria Party . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here p. 446, p. 407.

- ↑ Alf Mintzel: Bavaria Party . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here p. 446, p. 409.

- ↑ Alf Mintzel: Bavaria Party . In: Richard Stöss (Ed.): Party Handbook. The parties in the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980 , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1986 (1983), pp. 395–489, here p. 446, p. 411.

- ↑ Acted like the Sicilian Mafia . In: Der Spiegel . No. 33 , 1988 ( online - Aug. 15, 1988 ).

- ↑ Fools eaten . In: Der Spiegel . No. 39 , 1970 ( online - Sept. 21, 1970 ).

- ^ Results of the state elections in Bavaria

- ↑ Holtmann, Politiklexikon, 3rd edition, Oldenbourg, p. 521 f.

- ↑ Bavaria has a district administrator , Die Zeit No. 11/1970 of March 13, 1970, p. 6

- ↑ Heimlicher Sieger , Der Spiegel No. 12/1970 of March 16, 1970, p. 76

- ↑ “Your husband will fix it ” , Die Zeit No. 13/1970 of March 27, 1970, p. 12

- ↑ Election of the district councils in the districts , bayern.de, State Returning Officer Bavaria, accessed on August 18, 2012

- ↑ Election of the city councils in the independent cities , bayern.de, State Returning Officer Bavaria, accessed on August 18, 2012

- ↑ Temporal from Bavaria. The old people cry , Die Zeit No. 06/79 of February 9, 1979

- ↑ Festschrift of the Bavarian Party on the 50th anniversary of its existence in 1996 ( Memento from February 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). Accessed December 1, 2016 (PDF).

- ^ Uwe Kranenpohl: Bavaria Party. In: Frank Decker (editor), Viola Neu (ed.): Handbook of German parties. Wiesbaden, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2007, p. 165

- ↑ a b Uwe Kranenpohl: Bavaria Party. In: Frank Decker (editor), Viola Neu (ed.): Handbook of German parties. Wiesbaden, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2007, p. 167

- ↑ "Weißblauer Alpentraum", Die Zeit of June 26, 1981

- ↑ Bavaria Party advertises in Berlin . In: n-tv.de , dossier from June 5, 2009, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Andreas Rüttenauer, Stefan Kuzmany: Pros and Cons of the Bavarian Party: Electing Bavaria from Germany? . In: taz.de , comment from June 5, 2009, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Mini-parties in the European elections . In: sueddeutsche.de of December 4, 2009, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Olaf Przybilla: Get rid of Bavaria . In: sueddeutsche.de from June 4, 2009, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Markus Jox: Bavaria party pulls over Bavaria . In: Abendzeitung-muenchen.de from May 29, 2009, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ^ Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing - Local elections in Bavaria

- ↑ Local elections in Bavaria from March 2, 2008 (PDF; 11.9 MB), Bavarian State Office for Statistics, Statistical Report from February 2009, page 17

- ^ Final results of the 2013 state elections . In: landtagswahl2013.bayern.de . Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Final results of the 2013 state elections in the constituency of Lower Bavaria . In: landtagswahl2013.bayern.de . Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ District elections 2013 - constituency of Upper Bavaria - final result . In: bekreisstagswahl-oberbayern.de . Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Local elections in Bavaria on March 16, 2014 - results. Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing, accessed on December 1, 2016 .

- ↑ Frank Weichhan: council Kitzingen: Otto Hünnerkopf as a driving force . In: mainpost.de , March 18, 2014, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Siegfried Sebelka: Bayernpartei new - majorities old . In: mainpost.de , March 17, 2014, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ^ Rumor in the town hall: CSU city councilors overflow with the Bavarian party . In: Abendzeitung-muenchen.de , March 30, 2016, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Heiner Effern: Ex-SPD man Assal changes to the Bavarian party . In: sueddeutsche.de , April 5, 2016, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Andre Wächter in the RatInformationsSystem Munich. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ↑ https://www.kommunalwahl2020.bayern.de/verbindungen_gremien_wahlvorschlag_aktuell_1_990.html Retrieved on March 25, 2020

- ↑ Unger, Bayernpartei, p. 27 ff.

- ↑ Pope's visit shows ideas of tolerance ( memento from December 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , September 26, 2011.

- ↑ White-Blue Principles of the Bavarian Party . In: bayernpartei.de , p. 1. Retrieved on August 28, 2018 (PDF; 240 kB).

- ↑ Frequently asked questions . In: bayernpartei.de . Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ a b Gerhard Summer: Cheers for the king's message . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , June 17, 2012, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ a b Secretary General Hubert Dorn welcomes the King Loyalists on the occasion of the Ash Wednesday rally 2012, video (from 0:02:04) on YouTube

- ↑ a b White and Blue Principles of the Bavarian Party . In: bayernpartei.de , p. 15 f. Retrieved on August 28, 2018 (PDF; 240 kB).

- ↑ Franz Lehner, Ulrich Widmaier: Comparative Government. 4th edition. 2005.

- ↑ www.mainpost.de

- ↑ Statutes of the Bavarian Party of October 30, 2011. In: bayernpartei.de , accessed on August 28, 2018.

- ↑ a b Peter Mühlbauer : Return to the guilder? . In: Telepolis , November 8, 2011, accessed December 1, 2016.

- ↑ “Independence Dreams of the Bavarian Party”, Mittelbayerische Zeitung October 30, 2009

- ^ Website of the popular initiative "Freedom for Bavaria" ( Memento from April 28, 2015 in the web archive archive.today ) 7050 signatures as of April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Gerald Huber: Separatism in Bavaria. In: br.de , January 21, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ The state as a family - a comparison ( Memento from December 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de .

- ↑ Are we not in solidarity? ( Memento from July 19, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) In: bayernpartei.de .

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of December 16, 2016 - 2 BvR 349/16

- ↑ Patrick Bahners: Stayed here! Bavaria remains German FAZ , January 4, 2017

- ↑ Full steam ahead to the referendum ( Memento from April 4, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), Süddeutsche Zeitung from March 25, 2010

- ↑ Michel Watzke: A lot of money for a lot of smoke . In: Deutschlandfunk , July 1, 2010, accessed on December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Why we are against a total smoking ban - Answers to frequently heard counter arguments ( Memento from November 12, 2017 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de .

- ↑ Bavarian party starts petition for basic education salary ( Memento from December 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , June 11, 2012.

- ↑ Petition “Introduction of a Basic Education Salary” . In: wirsindbayern.bayernpartei.de . Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ ESM without Bavaria . In: wirsindbayern.bayernpartei.de . Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ ESM: Federal government creates absolutist fantasy world - press release from Bavaria party. openPR, June 4, 2012, accessed on August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ Facts about the ESM ( Memento from December 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , June 29, 2012.

- ↑ Call for a demonstration against the ESM ( Memento from March 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , June 22, 2012.

- ↑ 10 points in white-blue. In: bayernpartei.de. Accessed January 31, 2019 .

- ↑ Bavaria party calls for the abolition of the solidarity surcharge. (No longer available online.) Landesverband.bayernpartei.de, archived from the original on March 14, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ State financial equalization: Seehofer's fight in the fog. (No longer available online.) Landesverband.bayernpartei.de, archived from the original on March 21, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ Commuter flat-rate: equal money for all instead of preferring those with higher incomes ( memento of March 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , April 27, 2012.

- ↑ Do children need cribs? ( Memento from March 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , May 23, 2012.

- ↑ Resistance to private childcare is revealing ( memento of March 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de .

- ↑ Real freedom of choice instead of CSU care allowance ( memento from March 19, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , October 19, 2011.

- ↑ Seehofer and the pension at 67. (No longer available online.) Landesverband.bayernpartei.de, 2012, archived from the original on March 18, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ White-Blue Principles of the Bavarian Party . In: bayernpartei.de , p. 27. Accessed August 31, 2018 (PDF; 240 kB).

- ↑ White-Blue Principles of the Bavarian Party . In: bayernpartei.de , p. 45 f. Retrieved on August 28, 2018 (PDF; 240 kB).

- ↑ Energiewende: The truth about the solar record (press release). (No longer available online.) In: bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012 ; Retrieved August 1, 2012 .

- ↑ 10 years of war in Afghanistan . In: openpr.de . Press release of October 12, 2011, accessed December 1, 2016.

- ^ Paymaster Bavaria ( Memento from February 11, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ). In: freiheit-fuer-bayern.de .

- ↑ EU accession of Turkey: Financial aspects In: openpr.de . Press release of June 15, 2011, accessed December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Data retention: Bavarian party emphasizes the primacy of the constitution ( memento of March 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de , June 30, 2012.

- ↑ Bavarian party members want the end of the euro . In: openpr.de . Press release of November 10, 2011, accessed December 1, 2016.

- ↑ School policy: maintain educational federalism, defend the prohibition of cooperation. (No longer available online.) In: landesverband.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ White-Blue Principles of the Bavarian Party . In: bayernpartei.de , pp. 28–30. Retrieved on August 28, 2018 (PDF; 240 kB).

- ↑ Make secondary school more attractive. (No longer available online.) In: landesverband.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ Bayernpartei urges a continuous education concept for the secondary schools. (No longer available online.) In: landesverband.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ White-Blue Principles of the Bavarian Party . In: bayernpartei.de , pp. 31–33. Retrieved on August 28, 2018 (PDF; 240 kB).

- ↑ Parent-independent student loans. (No longer available online.) In: landesverband.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ Tuition fees: Bavaria's students pay twice. (No longer available online.) In: landesverband.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ Local history is integration. (No longer available online.) In: landesverband.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016 ; Retrieved August 21, 2012 .

- ↑ We are strengthening our dialects (state elections 2018). In: bayernpartei.de. August 25, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018 .

- ↑ State Board of Jungbayernbund. (No longer available online.) In: jbb.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017 ; accessed on December 1, 2016 .

- ↑ Honorary Chairman of the Jungbayernbund. (No longer available online.) In: jbb.bayernpartei.de. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017 ; accessed on March 16, 2015 .

- ↑ Young Bavaria Association. (No longer available online.) In: jbb.bayernpartei.de. Die Jungbayern, archived from the original on July 1, 2017 ; Retrieved June 2, 2013 .

- ↑ Bayernpartei (Ed.): Free Bavaria, Edition 4/86, p. 1 f.

- ^ Uwe Kranenpohl: Bavaria Party. In: Frank Decker (editor), Viola Neu (ed.): Handbook of German parties. Wiesbaden, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2007, p. 165 f.

- ^ District elections : BP multiplies mandates ( Memento from December 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). In: bayernpartei.de .

- ↑ Reinhold Willfurth: The district day is a little more colorful . In: Mittelbayerische.de . September 18, 2013, accessed December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Election results of the district election 2013 in Lower Bavaria ( Memento from April 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: bekreis-niederbayern.de (PDF; 274 kB)