Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt (* 23. December 1918 in Hamburg-Barmbek ; † 10. November 2015 in langenhorn ) was a German politician of the SPD . From 1974 to 1982 he was head of government of a social-liberal coalition after the resignation of Willy Brandt, the fifth Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany.

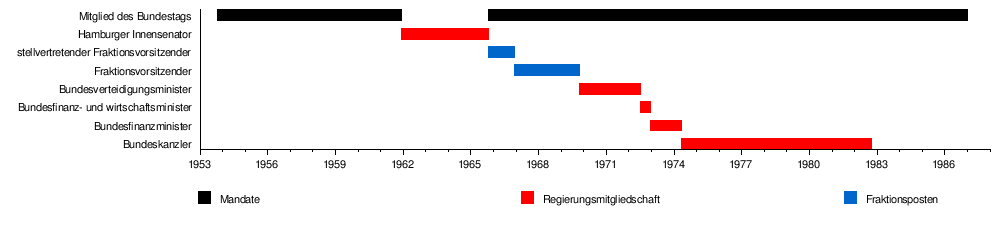

From 1961 Schmidt was a senator for the police in Hamburg. In this role he became known and appreciated far beyond Hamburg as a crisis manager during the storm surge in 1962 . From 1967 to 1969 he was chairman of the SPD parliamentary group , 1969 to 1972 Federal Minister of Defense and 1972 to 1974 Federal Minister of Finance .

Even after his chancellorship, Schmidt gained great popularity as an Elder Statesman across all parties. From 1983 until his death he was co-editor of the weekly newspaper Die Zeit .

Life

Origin and school

Helmut Schmidt was born in Hamburg in 1918 as the eldest of two sons of the teachers Gustav Ludwig Schmidt (1888–1981) and Ludovica Schmidt (née Koch) (1890–1968). He grew up in Hamburg and attended the Lichtwark School here , which he graduated from high school in March 1937 . Erna Stahl was one of his teachers .

Training and military service

As a 17-year-old student, Schmidt was expelled from the Marine Hitler Youth in 1936 for being too “brisk” , into which he and his student rowing club had been integrated two years earlier. After graduating from high school, Schmidt, like the majority of high school graduates, volunteered for military service in order to be able to study without interruption and initially did a six-month labor service in Hamburg-Reitbrook . On November 4, 1937, he was drafted into military service with the flak cartillery in Bremen-Vegesack . During this time he had a friendly relationship with Tim and Cato Bontjes van Beek and their family. From 1939 he was used as a sergeant in the reserve for the air defense of Bremen. In 1941, he became a reserve lieutenant in the High Command of the Air Force transferred to Berlin. From August to the end of 1941 Schmidt served as an officer in a light flak division of the 1st Panzer Division on the Eastern Front . He was u. a. commanded for the Leningrad blockade and received the Iron Cross 2nd class during this time . From 1942 to 1944 he was a consultant for training regulations for light anti-aircraft cartillery at the Reich Aviation Ministry in Berlin and Bernau .

As a member of the Reich Aviation Ministry, Oberleutnant Schmidt was assigned to watch the show trials of the People's Court against the men in the assassination attempt on July 20, 1944 . Disgusted by the behavior of the presiding judge Roland Freisler , Schmidt was released from further audience by his superior general. From December 1944, he was first transferred to Belgium as battery chief on the Western Front , and at the beginning of 1945 he criticized Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and the Nazi regime during an exercise on the Rerik flak firing range on the Baltic Sea . To do this, a Nazi command officer wanted to try him before a court martial. A trial was prevented, however, when two superior generals Schmidt withdrew from the judiciary through permanent transfers. In April 1945, Schmidt came in Soltau in the Luneburg Heath in British captivity . In a Belgian prison camp in Jabbeke , Hans Bohnenkamp's lecture entitled Verführtes Volk in June 1945 took away his last “illusions” about National Socialism. On August 31, 1945 he was released from captivity.

Schmidt made the statement about his development in the time of National Socialism that he was an opponent of the National Socialists. In evaluating his actions and attitudes at the time, this referred to an “internal opposition”. This is how a superior judged him on February 1, 1942: “Is on the floor of the nat. social worldview and knows how to pass on these ideas. ”Also in other assessments from his time in the Wehrmacht he was certified as having an“ impeccable National Socialist attitude ”(September 10, 1943) or a“ faultless National Socialist attitude ”(September 18, 1944). In the interview program Menschen bei Maischberger (night from April 28 to 29, 2015), Schmidt rejected this accusation as nonsensical: At that time it was common for commanders to issue certificates of favor regardless of the soldier's actual disposition. Neither the assessor nor the person assessed took these certificates seriously.

After founding the Bundeswehr , Schmidt was promoted to captain of the reserve in March 1958 . In October / November 1958 he took part in a military exercise in what was then the Iserbrook barracks in Hamburg-Iserbrook ; During the exercise he was voted out of the executive committee of the SPD parliamentary group on the grounds that he was a militarist .

Study and job

After his release from prisoner-of-war, Schmidt studied economics and political science at the University of Hamburg from 1945 and completed his studies in 1949 with a degree in economics . His thesis dealt with the comparison of currency reforms in Japan and Germany. He then worked as a speaker and later as a department head at the Department for Economics and Transport of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, which was headed by Karl Schiller . From 1952 to 1953 he headed the Office for Transport.

Party career

Immediately after his release from captivity, Schmidt joined the SPD in March 1946, according to his own statements, influenced by fellow prisoner Hans Bohnenkamp. Here he was initially involved in the Socialist German Student Union (SDS). 1947/1948 he was its chairman in the British zone of occupation . From 1968 to 1984 he was Deputy Federal Chairman of the SPD. Unlike the other two social democratic chancellors Willy Brandt and Gerhard Schröder , Schmidt was never the national chairman of his party.

Schmidt identified Max Brauer , Fritz Erler , Wilhelm Hoegner , Wilhelm Kaisen , Waldemar von Knoeringen , Heinz Kühn and Ernst Reuter as role models in his own party . In 2008, he commented on his motivation to become politically active:

“Ambition is a term I wouldn't apply to myself; Of course, I wanted public recognition, but the driving force was elsewhere. The driving force was typical of the generation I belonged to: We came out of the war, we saw a lot of misery and shit during the war, and we were all determined to do our part to ensure that all these horrible things never happen again in Germany. That was the real driving force. "

Member of Parliament

From 1953 to January 19, 1962 and from 1965 to 1987 Schmidt was a member of the German Bundestag . After moving back in 1965, he immediately became deputy chairman of the SPD parliamentary group. From 1967 to 1969, during the first grand coalition of the Federal Republic, he was finally chairman of the parliamentary group. Schmidt later admitted that he had enjoyed this position the most during his political career. From April 27, 1967 to 1969, he headed the parliamentary group's working group on foreign policy and all-German issues.

From February 27, 1958 to November 29, 1961 he was also a member of the European Parliament .

Schmidt entered the Bundestag in 1953 and 1965 via the Hamburg state list , in 1957 and 1961 as a directly elected member of the Hamburg VIII constituency and then always as a directly elected member of the Hamburg-Bergedorf constituency .

Offices and political functions

Senator in Hamburg (1961–1965)

From December 13, 1961 to December 14, 1965, Schmidt served under the First Mayors Paul Nevermann and Herbert Weichmann as Senator of the Police Authority (from June 1962: Senator for the Interior ) of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg. In this position he achieved popularity and a very high reputation as a crisis manager in the 1962 storm surge on the German North Sea coast on the night of February 16-17, 1962. He coordinated the large-scale deployment of the police, rescue services, disaster control and THW . Without being explicitly legitimized by the Basic Law, Schmidt used existing contacts with the Bundeswehr to ensure that the support that had already started for the Bundeswehr and allies with helicopters, pioneering equipment and supplies for Hamburg was reinforced. He is quoted as saying: "I did not look at the Basic Law in those days." In fact, the Bundeswehr had already been deployed several times in domestic disasters before 1962, and there was an internal service regulation for assistance in the event of disasters.

In January 1963, the federal prosecutor's office investigated the Interior Senator for aiding and abetting treason in the course of the Spiegel affair . The background to this was that, at the request of his college friend Conrad Ahler's request, Schmidt had excerpts from the article " Conditionally ready for defense " checked to see whether there were any legal obstacles to publication. The proceedings were discontinued in early 1965.

SPD parliamentary group leader in the Bundestag (1966 / 1967-1969)

In the elections of 1965 , Schmidt won another Bundestag mandate. When the Union- led government of Ludwig Erhard fell a year later , the SPD, together with the Union parties CDU / CSU, formed the first grand coalition with Kurt Georg Kiesinger (CDU) as Chancellor and Willy Brandt (SPD) as Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister. Schmidt, who had been provisional chairman of the SPD parliamentary group since the fall of 1966 due to Fritz Erler's illness and who officially took it over after Erler's death in February 1967, and Rainer Barzel , as parliamentary group chairmen of the two main coalition partners, played key roles in the vote of the party Work too. On this basis, a personal friendship developed with the political opponent Barzel, which lasted until his death in 2006. Schmidt held the funeral speech for Rainer Barzel at the state ceremony in the Bundestag. Schmidt's successful work as Hamburg's Senator for the Interior and parliamentary group chairman made him one of his party's first contenders for higher government tasks in federal politics.

Federal Minister (1969–1974)

Following the election victory of the SPD in the 1969 Bundestag elections and the agreement between the Social Liberal Coalition and the FDP , Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt Schmidt appointed Schmidt as Federal Minister of Defense in the new Federal Government on October 22, 1969 . During his term of office, the basic military service was shortened from 18 to 15 months and the establishment of the Bundeswehr universities in Hamburg and Munich was decided.

On July 7, 1972, after the resignation of Karl Schiller , he took over the office of Minister of Finance and Economics . After the federal election in 1972 , this “ super ministry ” was divided again. From December 15, 1972, the FDP appointed the Federal Minister of Economics ; Schmidt continued to head the Federal Ministry of Finance .

Federal Chancellor (1974–1982)

After Willy Brandt's resignation as head of government , the Bundestag elected Schmidt on May 16, 1974 with 267 votes in favor as the fifth Chancellor of the Federal Republic. The biggest challenges during his tenure were the global economic recession ( stagflation ) and the oil crises of the 1970s, which the Federal Republic survived better than most other industrialized countries under his leadership, as well as the pension financing 1976/1977 and the terrorism of the Red Army Faction (RAF) in the so-called " German Autumn ". He later saw his earlier willingness to negotiate with the terrorists, especially during the kidnapping of Peter Lorenz in 1975, as a mistake. From then on, he followed an unyielding, hard line that sometimes earned him harsh criticism from the relatives of victims. In an interview in 2007, Schmidt said that he found the enormous responsibility for the lives of others in the case of hostage-taking such as that of Hanns Martin Schleyer to be existentially depressing. Overall, the media gave the era of left-wing terrorism a weight that clearly exceeded its actual significance for German history.

Schmidt was a staunch advocate of generating electricity from nuclear power. In 1977 his government intended to build a nuclear fuel reprocessing facility in Gorleben .

Together with the French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing , Schmidt improved German-French relations and took decisive steps towards further European integration. The European Council was established shortly after Schmidt took office , and he also took the most important economic measure of his reign in cooperation with Giscard: the establishment of the world economic summit in 1975, which was planned as an informal gathering of the heads of state and government of the most important Western democracies. the introduction of the European Monetary System and the European Monetary Unit (ECU) on January 1, 1979, from which the European Economic and Monetary Union and the Euro would later emerge. The founding of the Group of 7 (G7) also went back to an idea by Schmidt and Giscard .

In 1977, Schmidt was the first western statesman to point out the dangers to the armaments balance posed by the Soviet Union's new SS-20 medium-range missiles : he feared that the Soviet Union would be able to attack Western Europe with nuclear weapons without affecting its protective power, the USA . could lead in the long run to a decoupling of American from European security interests. He therefore pushed for the so-called NATO double resolution , which provided for the deployment of medium-range missiles in Western Europe, but combined this with an offer to negotiate with the Soviet Union to renounce these weapon systems on both sides. This decision was very controversial in the population and especially in their own party. At the end of Schmidt's reign (1980), the new party of the Greens emerged from the protest movement against NATO's double decision, which was combined with the growing number of environmentalists .

His special commitment in the early 1980s was also aimed at improving relations between the two German states. The developments of the Cold War and decisions in the field of military confrontation between the two systems increasingly carried the risk of being directed against the peace-loving interests of the people of the FRG and the GDR. As an advocate of clearer and more serious efforts to relax, he went to the third Inner German Meeting at the invitation of Erich Honecker in December 1981; the meetings and discussions took place at the Werbellinsee and in Güstrow .

In the late summer of 1982 the social-liberal coalition he led broke up due to differences in economic and social policy (federal budget, public debt, employment programs). On September 17, 1982, all FDP federal ministers ( Hans-Dietrich Genscher , Gerhart Baum , Otto Graf Lambsdorff and Josef Ertl ) resigned. Schmidt therefore took over the office of Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs in addition to the office of Federal Chancellor for a short time and continued to run government without a majority in the Bundestag.

Vote of no confidence

On October 1, 1982 the chancellorship ended with a constructive vote of no confidence in Helmut Schmidt . With the votes of the CDU , CSU and the majority of the FDP parliamentary group, Helmut Kohl was elected as his successor in the office of Federal Chancellor.

Schmidt lost afterwards in the SPD almost any support for its security policy at the Cologne Congress of the SPD on 18 and 19 November 1983 agreed by some 400 delegates in addition to Schmidt 14 the Seeheim Circle associated delegates for the NATO double-track decision . Helmut Schmidt held his farewell speech in the Bundestag on September 10, 1986, and left parliament in 1987 at the end of the 10th electoral term .

Schmidt's security policy was meanwhile continued by the Christian-liberal coalition . It culminated in the conclusion of the INF treaties on December 8, 1987. With the conclusion of this agreement, Schmidt achieved the long-term goal of the 1979 double-ended NATO decision - the mutual destruction of Soviet and American medium-range nuclear missiles - which had been formulated by Schmidt in 1977.

Activities after the end of an active political career

Since 1983 Schmidt was co-editor of the Hamburg weekly newspaper Die Zeit , until 1990 also managing director of Zeitverlag with Hilde von Lang . After his election as Federal Chancellor, he did not take on any political office, but developed a lively journalistic activity as a book author, lecturer and sought-after elder statesman .

Schmidt was a member of the Atlantik-Brücke Association and Honorary President of the German-British Society . In 1993 he founded the German National Foundation , of which he was honorary chairman. He also held the honorary chairmanship of the InterAction Council , which he also co-founded , a council of former statesmen and women that he initiated with friends and of which he was chairman from 1985 to 1995. In 1992 the Helmut and Loki Schmidt Foundation (Hamburg) was established. 1995–1999 he was President of the German Poland Institute (Darmstadt). In 1997, Schmidt was one of the first to sign the Universal Declaration of Human Duties .

In 1985, Schmidt founded the Friday Society , based on the model of the Wednesday Society , which met in the winter semesters in his house for 30 years until it was dissolved, with the aim of exchanging members outside of their own professional area in the context of lecture evenings and subsequent discussions promote (since it was founded in 1996, Schmidt was also a member of the new Wednesday Society).

At the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen , where he gave the 7th Global Ethic Speech at the invitation of the President of the Global Ethic Foundation Hans Küng , Schmidt stated in May 2007 that in the constitutional-democratic order comes the reason of the politicians, but not their specific religious Confession to play a crucial role in constitutional politics. He was morally, politically and economically disappointed by the work of the churches, and nothing was less important to him than theology. After the Second World War , the churches did not re-establish morality, democracy and the rule of law . Despite his growing distance, he confessed to remaining in the church (as a church member), because it set counterweights against moral decline.

death

Helmut Schmidt died of an infection on November 10, 2015 a good month before he was 97 in his house in Hamburg-Langenhorn , after having had to be treated for a peripheral arterial disease ("smoker's leg") two months earlier . On November 23, 2015, a state ceremony was held in his honor in Hamburg's Michel with 1,800 invited guests. Following the funeral service, in which at Schmidt's request, the evening song of Matthias Claudius was sung, held Hamburg's Mayor Olaf Scholz , the former US secretary of state and close friend of the deceased Henry Kissinger and German Chancellor Angela Merkel , the memorial speeches. The urns of Helmut Schmidt and his wife Loki rest in the Koch and Schmidt family grave in the Ohlsdorf cemetery .

Both Schmidt spouses had decreed that after their death their house at Neubergerweg 80 should be transferred to a publicly accessible museum. The Helmut and Loki Schmidt Foundation is in charge of the implementation, and it is also responsible for deciding which of the rooms will be made accessible. Helmut Schmidt's private archive is managed in the archive of social democracy . A law establishing the Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt Foundation was passed on October 13, 2016 and came into force on January 1, 2017. As a non-partisan politicians Memorial Foundation she has devoted herself mainly topics that dominated the political work of Helmut Schmidt: the European integration , the social challenges of globalization and the crisis of the open society .

Political positions

Domestic politics

In 2005, Schmidt identified mass unemployment as the biggest German problem. He praised Gerhard Schröder's “ Agenda 2010 ” and saw it as a first step towards coping with the consequences of demographic change . However, he considered the reform program to be insufficient and, as early as 1997, spoke out in favor of deregulating the German labor market, including restricting protection against dismissal . The reasonableness of the unemployed should be tightened further and unemployment benefit II should be frozen for several years in nominal terms (or should decrease in real terms). Schmidt saw the collective agreement as outdated and demanded that it be largely abolished; the influence of what he considered to be the all too powerful unions should be reduced. According to Schmidt, a (but relatively lower) minimum wage could only be introduced after these reforms have been implemented . In order to finance the pensions, a general extension of working hours ( life and weekly working hours ) is unavoidable.

Schmidt was also a supporter of nuclear energy and an opponent of the nuclear phase-out, which was decided under the red-green led federal government. Another point of conflict with the SPD was his support for general tuition fees with adequate funding of the BAföG and scholarship system.

Schmidt was a supporter of the introduction of majority voting in Germany as early as the 1960s , when this reform was part of the domestic political agenda of the then grand coalition . Later he still saw it as superior to proportional representation , but considered the success of a new attempt at electoral reform to be impossible. Schmidt rejected a frequently requested extension of referendums because they are too dependent on the mood of the people. He also criticized the type of party funding in Germany. In the long term, he wanted the complete abolition of state funding and business donations. Private membership fees should no longer be tax-deductible.

Schmidt certified numerous historically grown weaknesses in German federalism , which he referred to as “ small states, ” although he acknowledged the principle of subsidiarity . Schmidt viewed the "permanent quarterly election campaign" due to the "egoism of the parties" and the interference of state politics in federal politics as crippling, as it influenced or delayed national legislation in a populist way ("to increase popularity"). He therefore advocated pooling all federal and state elections on a single date every two years, along the lines of the United States of America . According to Schmidt's will, the German capital Berlin should be financially strengthened, with a capital ( federal district ) such as Washington, DC, subordinate to the federal government and maintained by it, such as Washington, DC, as the most viable model.

Throughout his life, Helmut Schmidt complained of Germany's excessive “regulatory rage” and noted that the state executive had a pronounced “belief in paragraphs”. The political class in Germany had been hit by a “psychological epidemic”, as evidenced by the deposit on cans introduced in 2003 and the smoking ban that was enforced until 2008 . Therefore, many laws should be abolished and simplified. The Basic Law should be changed more cautiously and not as frequently and the Federal Constitutional Court should hold back with its "restrictive" judgments. Schmidt warned of a power shift between parliament and bureaucracy. For him, the best example of an authority that acts without understanding or parliamentary control was the KMK, the Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs, which caused the German spelling chaos.

In 2011, Schmidt joined the debate about the role of the ECB in the current crisis of the common currency, the euro. This was u. a. also came under criticism through statements of the then Federal President Christian Wulff . Here Schmidt spoke out clearly in favor of the ECB, which he praised for its independence.

Social policy

The multicultural society called Helmut Schmidt as "an illusion of intellectuals". According to Schmidt, the concept of multiculturalism is difficult to reconcile with a democratic society. It was therefore a mistake "that we brought guest workers from foreign cultures into the country at the beginning of the 1960s ".

On the question of the age of majority , Helmut Schmidt was always against the reduction from 21 to 18 years of age in 1975. This was in contrast to the party opinion of the SPD.

Foreign policy

In foreign policy, Schmidt attached great importance to the principle of non-interference in the affairs of sovereign states . Schmidt took a critical stance on so-called humanitarian interventions such as those in the Balkans: “Unfortunately, as far as international law is concerned, we are currently only experiencing setbacks, not only among the Americans, but also on the German side. What we did in Kosovo and in Bosnia-Herzegovina clearly violated the international law applicable at the time. "

Schmidt was against Turkey's planned accession to the European Union . He feared that accession would jeopardize the EU's freedom of action in foreign policy, as well as that accession and the associated freedom of movement would render the integration of Turkish citizens living in Germany, which in his opinion urgently needed, futile.

He called the G8 summit in its current form a "media spectacle" and called for the expansion to include China , India , the major oil exporters and the developing countries .

Climate policy

Schmidt called the debate about global warming in June 2007 "hysterically overheated". There has always been a change in climate; the causes are "not yet adequately researched". In 2011 Schmidt stated on the one hand: “The so-called climate policy pursued internationally by many governments is still in its infancy. The documents supplied so far by an international group of scientists "- (meaning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ) - are met with skepticism. In any case, the objectives publicly stated by some governments are so far less scientifically and more politically justified ”, but also spoke out in favor of a reorientation in energy policy , since fossil reserves are limited and climate change, insofar as it is energy-related, must be counteracted .

He described the global population explosion and the associated handling of food, energy and environmental protection issues as the greatest international challenge of the future .

Private

family

Schmidt's father Gustav (1888–1981), illegitimate son of the Jewish private banker Ludwig Gumpel and a waitress, was adopted by the Schmidt family. Having grown up in the house of a dock worker, Gustav Schmidt trained as an elementary school teacher after completing an apprenticeship in a law firm with the professional goal of office manager . Later, he made the trade teaching certificate and was last teacher . The two sons of Gustav and Ludovica Schmidt, Helmut and his younger brother Wolfgang († 2006), attended the Wallstraße elementary school east of the Outer Alster and then the Lichtwark high school on Grasweg in Winterhude .

According to Schmidt, himself a Protestant , he and his father hushed up his Jewish descent by forging documents so that the Aryan certificate was issued. As a " second degree Jewish hybrid " Schmidt would have been disadvantaged and an officer career in the Wehrmacht would have been excluded.

Schmidt did not disclose these connections to the public until 1984 when journalists found out about this from Giscard d'Estaing. In his childhood and youth memories (1992) he writes that his origins helped determine his rejection of National Socialism .

“The high school pupil Schmidt, who was 14 years old at the time of the transfer of power to Hitler, knew that he was a“ quarter Jew ”and would have been considered racially inferior if this fact had become known. At first he was not reluctant to be a member of the Marine Hitler Youth; in the summer of 1936 he took part in an "Adolf Hitler march" from Hamburg to Nuremberg for the Nazi party rally. He did not become a National Socialist, but was temporarily impressed by the "socialist" propaganda of the regime that conjured up the values of the community. "

Helmut Schmidt married Hannelore Glaser (“Loki”, 1919–2010) on June 27, 1942 . The church wedding took place on July 1, 1942 in the St. Cosmae and Damiani Church in Hambergen . The marriage had two children. Her son Helmut Walter (born June 26, 1944), born disabled in Bernau near Berlin, died there on February 19, 1945 before his first birthday. Daughter Susanne , who works for the business television broadcaster Bloomberg TV in London, was born in Hamburg in May 1947.

In a later interview, Schmidt stated that his family sometimes hid Jews during the National Socialist era , and that he knew nothing about concentration camps or the genocide of the Jews , as was the case with many people at the time.

In the autumn of 1981 Schmidt became seriously ill, so that on October 13, 1981, a pacemaker was inserted into the Bundeswehr Central Hospital in Koblenz . Previously, the then Chancellor had to be resuscitated twice after Adams-Stokes attacks .

In August 2002 Schmidt had to undergo a bypass operation as a result of a severe heart attack .

Schmidt had lived in Hamburg-Langenhorn for a long time . Schmidt had a second home on Brahmsee in Holstein . His denomination was Evangelical Lutheran, although he did not describe himself as religious, but was not an atheist either. In June 2007 he said in a television interview on the show Menschen bei Maischberger that he no longer trusts in God, u. a. because God allowed Auschwitz . When asked whether he would have liked to exercise the office of Federal Chancellor, he replied: “Not really that much, no.” He justified this statement by stating that the office of Federal Chancellor was a very heavy burden, especially for private life be.

Almost two years after Loki's death, Schmidt announced in August 2012 that he had a new partner: Ruth Loah (* September 27, 1933; † February 23, 2017), who had been one of his confidants for decades.

Friendships

Helmut Schmidt was a close friend of the banker, US officer and founder of the German-American network Atlantik-Brücke , Eric M. Warburg . He also became friends with the former United States Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger .

Paul Volcker , the globally influential director of the American Council on Germany , long-time member and former director of the Council on Foreign Relations , member of the Trilateral Commission and chairman of the US Federal Reserve , had been a confidante for over 40 years. Schmidt also stayed in contact with John J. McCloy , former President of the World Bank , Director of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), CEO of Chase Manhattan Bank and initiator of the German-American network Atlantik-Brücke .

Schmidt counted the murdered Egyptian President Anwar as-Sadat and the former French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing among his most outstanding political friends. Former US Secretary of State Kissinger said he hoped to die before Schmidt; he doesn't want to live in a world in which there is no Helmut Schmidt.

Schmidt took advice from the philosopher Karl Popper , with whom he was in close correspondence.

On October 28, 2014, Schmidt held a farewell speech for the writer Siegfried Lenz , who died on October 7 and was friends with him, during the funeral service .

Art, music, philosophy and other interests

As Federal Chancellor, Schmidt ensured that the sculpture Large Two Forms by Henry Moore was installed in front of the Federal Chancellery in Bonn, which was supposed to symbolize the belonging together of the Federal Republic and the GDR . Schmidt's passion for art went so far that he had the Federal Chancellery equipped with numerous art loans. He also had the “Federal Chancellor” sign removed in front of his office and instead a sign saying “ Nolde -Zimmer” was put up, which should refer to the art in his office. In 1986, Schmidt chose the Leipzig painter Bernhard Heisig as a portraitist for the gallery of former Federal Chancellors in the Chancellery . This choice came as a surprise at the time. At the age of 95, Helmut Schmidt sat as a model for the Hamburg painter Manfred W. Juergens .

Both Schmidts' houses in Hamburg house numerous pictures and graphics by different artists , including his own, because the landlord painted himself into old age. From October 4, 2020 to January 31, 2021, there is a selection of around 150 pieces from the collection of Helmut and Loki Schmidt exhibited in the Ernst-Barlach-Haus in Hamburg.

But Schmidt also had a special relationship with music. For example, it was he who, as Federal Defense Minister, brought the Bundeswehr Big Band into being. He himself played the organ and piano and particularly appreciated the music of Johann Sebastian Bach . At the age of 17 he composed four-part movements for hymns. In the last years of his life, Schmidt suffered from being unable to enjoy music because of his poor hearing; Schmidt was almost deaf in his right ear, and in his left ear he wore a hearing aid that made it possible for him to hear speech to some extent.

Helmut Schmidt has recorded several records in which he can be heard as an interpreter of the works of classical composers, for example by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , Concerto for three pianos and orchestra , KV 242, or by Johann Sebastian Bach, Concerto for four pianos and strings in A minor, BWV 1065, together with the pianists Christoph Eschenbach , Justus Frantz and Gerhard Oppitz .

In addition to Mark Aurel and Immanuel Kant , Schmidt's “house philosophers” also included Max Weber and Karl Popper . Schmidt's own efforts as a politician to act pragmatically for moral purposes and his preoccupation with philosophy are respectfully recognized by experts. Volker Gerhardt wrote that Schmidt is a philosopher in the sense of a moralist who is committed to being a moral politician. He is in line with Otto von Bismarck , Walther Rathenau and Winston Churchill .

“All three were geniuses at political level; all of them had great intellectual talents, achieved great political achievements and, moreover, left behind an important literary work. Helmut Schmidt is on a par with them, even if he has published more as an author than all three together [...] His work focuses on the ethical question. It takes the global political lessons seriously, which must be drawn from the economic crisis of 1928, from the global political consequences of the hardship, from the world wars and from the danger of the global self-destruction of mankind, which has become visible for the first time with the development of technology. As Helmut Schmidt took on these problems with increasing intensity in the course of his life, one recognizes that his increasingly obvious turn to philosophy is itself again obeying political insights. He's always remained a politician, but the philosophers would do well to take him as seriously as if he were one of them. "

Public perception and appreciation

During his politically active time, Schmidt was also called "Schmidt Schnauze" by opponents because of his talent for speech. His economic expertise was widely recognized.

In 2005, Helmut Schmidt was identified as the most popular politician in recent German history in a survey by the opinion research institute Emnid . As a hamburger he was for many "the Hanseatic par excellence".

Schmidt was a public smoker . A column in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit was called Auf ein Cigarette with Helmut Schmidt . In public spaces - for example in the Hamburg citizenship - he was not banned from smoking even after the smoking bans in the federal states were tightened . He considered these prohibitions to be a temporary social phenomenon. Schmidt even smoked during television reports or in television studios. In the plenary hall of the Bundestag, where smoking was banned early on, he switched to snuff during the sessions . He was regularly parodied by cabaret artist Wilfried Schmickler as a chain smoker "Smoky" (together with Uwe Lyko as "Loki") on the WDR show Mitternachtsspitzen in the format "Loki und Smoky" .

Honors

In the course of his life Helmut Schmidt received numerous honors in the form of prizes, honorary doctorates and honorary citizenships. However, in 1968, according to Hanseatic tradition , he rejected the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in the form of a star and shoulder ribbon .

Prices

- 1978: Theodor Heuss Prize for his crisis management during the time of the RAF terror

- 1978: Peace Prize of the Louise Weiss Foundation in Strasbourg

- 1986: Athena Prize from the Alexander Onassis Foundation

- 1988: Four Freedoms Award from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Foundation.

- 1989: “ The Political Book ” award from the Friedrich Ebert Foundation for people and powers

- 1990: Naples Journalism Prize

- 1990: Friedrich Schiedel Prize for Literature for People and Powers

- 1996: Spanish Journalism Prize Godo

- 1998: Carlo Schmid Prize

- 2001: Gold medal from the Jean Monnet Foundation for his commitment to the European Monetary Union (together with his friend, the former French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing)

- 2002: Martin Buber plaque (first prize winner)

- 2002: Dolf Sternberger Prize.

- 2005: “Prix des Générations” of the VIVA 50plus initiative. As an outstanding statesman , "[...] Helmut Schmidt not only promoted the coexistence of generations, but also the understanding between the age groups [...]".

- 2005: Oswald-von-Nell-Breuning -Prize of the city of Trier , for the "[...] seriousness with which Helmut Schmidt repeatedly asked himself questions about a fair social balance [...]"

- 2005: Adenauer de Gaulle Prize for his work on Franco-German cooperation (together with Valéry Giscard d'Estaing)

- 2007: Henry Kissinger Prize of the American Academy in Berlin , first ever prize winner, for his outstanding role as a publicist in transatlantic communication.

- 2007: World Economic Prize , for his realistic politics with a sense of moral duty.

- 2008: Osgar ( Bild-Zeitung media award )

- 2009: International Mendelssohn Prize in Leipzig in the social commitment category.

- 2010: Point Alpha Prize , endowed with 25,000 euros, for services to the unity of Germany and Europe in peace and freedom. The Kuratorium Deutsche Einheit e. V. thus paid tribute to Schmidt's “steadfastness in the NATO double decision and his role in the CSCE process”.

- 2010: Henri Nannen Prize for his life's work as a journalist

- 2011: Millennium - Bambi , awarded in the Rhein-Main-Hallen in Wiesbaden

- 2012: Eric M. Warburg Prize

- 2012: International Peace Prize of Westphalia , awarded on September 22, 2012 to Schmidt and the children's aid organization Children for a better World in the historic town hall of Münster

- 2013: Hanns Martin Schleyer Prize for 2012 "for outstanding services to strengthening and promoting the foundations of a free community"

- 2014: Media Prize of the Franco-German Journalism Prize (DFJP)

- 2015: Gustav Stresemann Prize of the Grand Lodge of the Old Free and Accepted Masons of Germany for the "lifetime achievement of a person"

Further honors

Helmut Schmidt was an honorary citizen of his hometown Hamburg (1983), Bonn (1983), Bremerhaven (1983), Berlin (1989), Barlachstadt Güstrow (1995) and the state of Schleswig-Holstein (1998).

Helmut Schmidt was made an Honorary Senator of the University of Hamburg in 1983. In 1996 he became an honorary foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

During and after his reign, Helmut Schmidt was honored with 24 honorary doctorates , including from the British universities of Oxford and Cambridge , the Sorbonne in Paris , the American Harvard University and Johns Hopkins University , the Keiō University in Japan and the Belgian Katholieke Universiteit Leuven .

Helmut Schmidt received an honorary doctorate from the Philipps University of Marburg in 2007 as part of the Christian Wolff lectures on the grounds that the “subject of philosophy, which is committed to the Enlightenment” recognizes “in Helmut Schmidt the philosopher in the politician”.

On January 17, 2006, Schmidt became an honorary member of the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold

In 1966 Schmidt received the golden Nuremberg funnel of the Nuremberg funnel carnival society and in 1972 the medal against the seriousness of the Aachen carnival society for his hairnet decree .

Designations

- A rose variety was named after Helmut Schmidt in 1979.

- The Helmut Schmidt Journalists Prize has been awarded annually since 1996 by ING-DiBa for special achievements in the field of critical consumer journalism through consumer-oriented reporting on economic and financial topics. Helmut Schmidt was the patron.

- In 2003, a chair for international history at the private International University Bremen was named in honor of Helmut Schmidt .

- In December 2003 the University of the Federal Armed Forces in Hamburg was renamed the Helmut Schmidt University / University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg . He received an honorary doctorate from this university for his commitment to the scientific training of officers in the early 1970s.

- In 2007 the Zeit Foundation established the Helmut Schmidt Prize for German-American Economic History , which is awarded by the German Historical Institute in Washington . Previous winners were: Harold James ( Princeton University ), Volker Berghahn ( Columbia University ), Richard H. Tilly ( Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster) and Charles S. Maier ( Harvard University ).

- On November 5, 2012, the Kirchdorf / Wilhelmsburg grammar school in Hamburg-Wilhelmsburg was renamed the Helmut Schmidt grammar school .

- On January 7, 2016, the Hamburger Pressehaus , the seat of the weekly newspaper Die Zeit , was renamed the Helmut Schmidt House.

- The Hamburg airport is named since November 2016 Hamburg Airport Helmut Schmidt .

- The Bucerius Law School auditorium was renamed the “Helmut Schmidt Auditorium” in November 2016.

- A street in Bernau-Schönow has been named Helmut-Schmidt-Allee since January 1, 2017. Helmut and Loki Schmidt had lived there around 1944/1945 while he was stationed there as an officer in the Air Force. Her son Helmut Walter was buried in Schönow. The grave has now been leveled.

- In May 2020 the Lindenhof flyover in Mannheim was renamed the Helmut Schmidt Bridge.

Commemorative coin and postage stamp

For Helmut Schmidt's 100th birthday, a 2-euro commemorative coin was issued on January 30, 2018, and a special postage stamp with a face value of 70 euro cents on December 6, 2018 . The design for the stamp comes from the graphic artist Frank Fienbork.

Foundations

The Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt Foundation was established on January 1, 2017 as a non-partisan political memorial foundation , on the one hand to honor Helmut Schmidt's historical merits and, on the other, to dedicate itself to topics that shaped Helmut Schmidt's political work and which are still not topical today have lost. The headquarters of the foundation is in Hamburg's old town. The former home of the Schmidt family in Hamburg-Langenhorn also houses the Helmut Schmidt archive, which is open to scientific research.

Senates and Cabinets

Works (excerpt)

1960-1969

- Defense or retaliation. A German contribution to the strategic problem of NATO. Seewald, Stuttgart-Degerloch 1961, OCLC 2535872 .

- Military command and parliamentary control . In: Horst Ehmke , Carlo Schmid , Hans Scharoun , Festschrift for Adolf Arndt on his 65th birthday. Frankfurt am Main 1969, pp. 437-449, OCLC 864545567 .

- Reform of parliament . In: Claus Großner : The 198th decade. Marion Countess Dönhoff in honor. Wegner, Hamburg 1969, pp. 323-336. OCLC 47309003 .

1970-1979

- The opposition in modern democracy . In: Rudolf Schnabel , The Opposition in Modern Democracy. Stuttgart 1972, pp. 51-60.

- As a Christian in political decision-making. (Gütersloher Taschenbücher Siebenstern 206). Gütersloher Verlagshaus Mohn, Gütersloh 1976, ISBN 3-579-03966-0 .

- On the state of the nation: Declaration by the Federal Government to the German Bundestag on May 17, 1979 (154th session of the German Bundestag). Press and Information Office of the Federal Government, Bonn 1979, DNB 790627868 (= series of reports and documentations , volume 18).

1980-1989

- A strategy for the west. Siedler, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-88680-184-5 .

- People and powers. Siedler, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-88680-278-7 .

- Politics as a profession today . In: Hildegard Hamm-Brücher , Norbert Schreiber : The enlightened republic. A critical balance. Munich 1989, pp. 77-84.

1990-1994

- The Germans and their neighbors. People and Powers, Part 2. Settlers, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-88680-289-2 .

- Political review of an apolitical youth. In: Helmut Schmidt, Hannelore Schmidt u. a .: Childhood and youth under Hitler. Goldmann TB, 1994, ISBN 3-442-12851-X , pp. 209-282.

- Act for Germany. Berlin 1993.

- On the state of the nation. 1994.

1995-1999

- Peter Frieß, Andreas Fickers (eds.): Helmut Schmidt and Hartmut Graßl talk about the obligation of scientists to bring society and politicians to accept scientific knowledge (= TechnikDialog , volume 3), Deutsches Museum , Bonn 1995, OCLC 907718871 (die ISBN 3-924183-92-9 was used twice).

- Companions - memories and reflections. Siedler, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-88680-603-0 .

- as editor: The Universal Declaration of Human Duties . Suggestion. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-492-22664-7 .

- In search of a public morality. Germany before the new century. October 1998 (April 1999 already in the 8th edition). Goldmann, Munich ISBN 3-442-15071-X .

- Globalization. Political, economic and cultural challenges. DVA, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-421-05160-7 .

- Dorothea Hauser (Ed.): Turn of the century. Conversations with Lee Kuan Yew , Jimmy Carter , Schimon Peres , Valéry Giscard d'Estaing , Ralf Dahrendorf , Michail Gorbatschow , Rainer Barzel , Henry Kissinger , Helmut Kohl , Henning Voscherau . Siedler, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-88680-649-9 .

- Explorations - Contributions to understanding our world. Minutes of the Friday Society. Edited by Helmut Schmidt. DVA, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-421-05282-4 .

2000-2004

- The self-assertion of Europe, perspectives for the 21st century. DVA, Stuttgart / Munich 2000, ISBN 3-421-05357-X .

- Hand on heart. Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Sandra Maischberger . Ullstein, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-548-36460-8 .

- The powers of the future: winners and losers in the world of tomorrow. Siedler Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-442-15378-6 .

2005-2009

- On the way to German unity. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-498-06385-6 .

- Neighbor China. Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Frank Sieren . Econ, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-430-30004-5 ( preprint in: Die Zeit. No. 39/2006).

- I am not afraid of death. Interview Vanessa de l'Ors with Helmut Schmidt, “ Cicero - Magazine for Political Culture” , March 2007, pp. 56–66, ISSN 1613-4826 . ( online article )

- Out of service . Siedler, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-88680-863-2 .

- Helmut Schmidt, Giovanni di Lorenzo : On a cigarette with Helmut Schmidt . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-462-04065-4 . (Compilation of interviews of Die Zeit editor -in- chief with Schmidt, which appeared in the column "Auf eine Zigarette mit Helmut Schmidt" )

2010-2015

- Helmut Schmidt, Fritz Stern : Our Century: A Conversation. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60132-3 . (Also as an audio book, read by Hanns Zischler and Hans Peter Hallwachs . The Audio Verlag (DAV), Berlin, 2010, ISBN 978-3-89813-978-6 . Reading, 5 CDs, 307 min.)

- Helmut Schmidt: Interfering - his best ZEIT articles from 1983 until today . Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-455-50181-0 (article that he published in his role as editor of the weekly newspaper "Die Zeit")

- In-depths - New contributions to understanding our world. Minutes of the Friday Society. Edited by Helmut Schmidt. Siedler, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-88680-967-7 .

- Religion in responsibility. Threats to Peace in the Age of Globalization . Propylaea, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-549-07409-1 .

- Helmut Schmidt, Peer Steinbrück : Step by Step. Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-455-50197-1 .

- Helmut Schmidt, Giovanni di Lorenzo : Do you understand that, Mr. Schmidt? 5th edition, Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-462-04486-7 . (Compilation of interviews of Die Zeit editor -in- chief with Schmidt, which appeared in the column “Do you understand that, Mr. Schmidt?” )

- One last visit - encounters with the world power China. Conversation with Lee Kuan Yew , Siedler, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-8275-0034-2 ; as audio book: der Hörverlag, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-8445-1147-5 .

- My Europe. Speeches and essays. With a conversation between Helmut Schmidt and Joschka Fischer . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-455-50315-9 .

- Speech on the occasion of the award of the Hanns Martin Schleyer Prize to HS on Friday, April 26, 2013 in Stuttgart. “Decision of conscience in conflict” .

- What I wanted to say. Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-67612-3 .; as an audio book: Der Audio Verlag, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-86231-502-4 .

- Then I would have become the port director: Hamburg views . With a conversation between Helmut Schmidt and Olaf Scholz . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-455-50351-7 .

literature

Overall biographical presentations

- Sibylle Krause-Burger : Helmut Schmidt - seen up close . Econ, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1980 ISBN 3-430-15655-6 .

- Michael Schwelien: Helmut Schmidt. A life for peace . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-455-09409-0 .

-

Hartmut Soell : Helmut Schmidt .

- Volume 1: Reason and Passion. 1918-1969 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-421-05352-9 .

- Volume 2: Power and Responsibility. 1969 until today . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-421-05795-2 .

- Kristina Spohr: Helmut Schmidt. The world chancellor . wbg Theiss, Darmstadt 2016, ISBN 978-3-8062-3404-6 .

- Hans-Joachim Noack : Helmut Schmidt. The biography . Rowohlt, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-87134-566-1 .

- Harald Steffahn: Helmut Schmidt . 4th edition, rororo, 1990, ISBN 3-499-50444-8 .

- Reinhard Appel : Helmut Schmidt. Statesman - publicist - legend . 1st edition, Lingen Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-938323-81-6 .

- Gunter Hofmann : Helmut Schmidt - soldier, chancellor, icon. Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68688-7 .

- Reiner Lehberger : The Schmidts. A couple of the century . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-455-00436-6 .

Image biographies and photo documentation

- Stefan Aust , Robert Fleck (ed.): Helmut Schmidt - A life in pictures of the mirror archive . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich, and SPIEGEL-Buchverlag, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-421-05888-1 . (Photo biography using personal and private recordings)

- Dieter Dowe , Michael Schneider (Ed.), Josef Heinrich Darchinger (Photographer): Helmut Schmidt - Photographed by Jupp Darchinger. JHW Dietz Verlag (Nachf.), Bonn 2008, ISBN 978-3-8012-0389-4 .

- Jens Meyer-Odewald: One life. Helmut and Hannelore Schmidt. Ed .: Lars Haider. Hamburger Abendblatt, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-939716-98-3 . (Image double biography using photos from public archives and private photos from the Helmut Schmidt archive)

Stages of life

- Sabine Pamperrien : Helmut Schmidt and the shitty war. The biography from 1918 to 1945. Piper Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-492-05677-9 .

- Uwe Rohwedder: Helmut Schmidt and the SDS. The beginnings of the Socialist German Student Union after the Second World War . Edition Temmen, Bremen 2007, ISBN 978-3-86108-880-6 .

- Detlef Bald : Politics of Responsibility. The example of Helmut Schmidt: The primacy of the political over the military 1965–1975 . Aufbauverlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-351-02674-5 .

- Andrea H. Schneider: The Art of Compromise, Helmut Schmidt and the Grand Coalition 1966–1969. Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 1999, ISBN 3-506-77957-5 .

- Matthias Waechter: Helmut Schmidt and Valéry Giscard d'Estaing. In search of stability in the crisis of the 1970s , Edition Temmen, Bremen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8378-2010-2 .

- Klaus Bölling : The last 30 days of Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. A diary. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, ISBN 3-499-33038-5 .

- Jochen Thies : Helmut Schmidt's withdrawal from power. The end of the Schmidt era at close range. 2nd edition, Verlag Bonn Aktuell, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-87959-376-0 .

- Thomas Karlauf : Helmut Schmidt. The late years. Siedler Verlag, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-8275-0076-2 .

Principles, values and style, motives for action

- Martin Rupps : Helmut Schmidt. Man - statesman - moralist . Herder, Freiburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-451-06020-5 .

- Martin Rupps: Helmut Schmidt - The last smoker. Herder, Freiburg i. Br. 2011, ISBN 978-3-451-30419-4 .

- Martin Rupps: The pilot. Helmut Schmidt and the Germans . Orell Füssli, Zurich 2015, ISBN 978-3-280-05553-3 .

- Theo Sommer : Our Schmidt - the statesman and the publicist . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-455-50176-6 .

Individual aspects

- Helmut and Loki Schmidt Foundation (Ed.): Chancellor's Art - The private collection of Helmut and Loki Schmidt , Dölling and Galitz Verlag, Munich / Hamburg 2020, ISBN 978-3-86218-134-6

- Helmut Stubbe da Luz : "The Basic Law not looked at", "excited chickens" found. Helmut Schmidt, the rescuer from the disaster. In: Great disasters in Hamburg. Human failure in history - defensive urban development for the future? Accompanying volume for the exhibition “Great Disasters in Hamburg” at the Helmut Schmidt University / University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg , Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-86818-094-7 , pages 99–153

- Jörg Magenau : Schmidt - Lenz . Story of a friendship. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-455-50314-2 .

- Gunter Hofmann : Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt. Story of a difficult friendship. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63977-7 .

- Henning Albrecht : Pragmatic action for moral purposes. Helmut Schmidt and philosophy . Edition Temmen, Bremen 2008, ISBN 978-3-86108-635-2 .

- Johannes von Karczewski: "The world economy is our fate". Helmut Schmidt and the creation of the world economic summit . Dietz, Bonn 2008, ISBN 978-3-8012-4186-5 .

- Heinz-Norbert Jocks : The real and the imagined China. Interview with Helmut Schmidt. In: Kunstforum International. Vol. 193, September-October 2008, pp. 64-77.

- Guido Thiemeyer: Helmut Schmidt and the establishment of the European Monetary System 1973–1979. In: Franz Knipping, Matthias Schönwald (Hrsg.): Departure to Europe of the second generation. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, Trier 2004, ISBN 3-88476-652-X , pp. 245-268.

- Art in the Chancellery - Helmut Schmidt and the arts. Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-442-10192-1 .

- Rainer Hering : Helmut Schmidt - Der Protestantismus, die Kirchen und die Religion , in: Zeitschrift für Schleswig-Holsteinische Kirchengeschichte , Volume 2, 2015, pp. 269–287.

Appreciations

- Wolfgang Mielke; Helmut Marrat: Helmut Schmidt on his 95th birthday; Helmut Schmidt, Poetic Strength / A Sketch . In: Perinique . World Heritage Magazine. No. 18 . Perinique Verlag, May 2014, ISSN 1869-9952 , DNB 1000901297 , ZDB -ID 2544795-6 , p. 7-23 .

Film and television appearances

- 1997: Death Game . TV docu-drama, Germany 1997, 177 min., Script and director: Heinrich Breloer , production: WDR , with an interview with Schmidt and his cinematic representation

- 2005: The night of the great flood. TV docu-drama, Germany 2005, 90 min., Script and director: Raymond Ley , production: Cinecentrum, first broadcast: October 28, 2005, TV docudrama about the storm surge of 1962 in Hamburg. (Film clips)

- 2005: Helmut Schmidt - My Life. Documentation, Germany, 43 min., Director: Felix Schmidt, production: macroscope, ZDF , summary by arte

- 2006: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Reinhold Beckmann . First broadcast: September 25, 2006, summary ( memento of April 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) by ARD, with video (approx. 70 min.)

- 2007: Helmut Schmidt out of service. TV feature, 90 min., 2001–2006, a film by Sandra Maischberger and Jan Kerhart , production: NDR, first broadcast: July 4, 2007, awarded the Golden Camera 2008 in the “Best Information” category, as a YouTube video in 9th Share: Part 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , also as Die Zeit documentation

- 2008: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Sandra Maischberger , (“ People at Maischberger ”, 75 min.) From May 20, 2008, video ( memento from December 2, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) by ARD

- 2008: Book presentation “Out of service” - Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Claus Kleber , first broadcast: September 21, 2008, 1 p.m. ( Phoenix ) Video in the PHOENIX library

- 2008: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Reinhold Beckmann. First broadcast: September 22, 2008, table of contents ( memento from March 5, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) by ARD (approx. 72 min.)

- 2008: Mogadishu . TV drama about the kidnapping of the Lufthansa machine Landshut , Germany 2008, 108 minutes, directed by Roland Suso Richter

- 2008: Helmut Schmidt - The German Chancellor. Documentation, ZDF from December 16, 2008, 8:15 p.m. - 9:15 p.m., duration 58 minutes.

- 2008: Schmidt (Bergedorf) - Properties. Biography, Die Zeit , from December 11, 2008, DVD, duration 9 minutes.

- 2008: Helmut Schmidt - My Century. A film by Reinhold Beckmann and Christoph Weinert, ARD (60 min.) From December 23, 2008

- 2009: On the State of the Union. Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Sigmund Gottlieb , BR (“Münchner Runde”, 45 min.) On February 3, 2009

- 2009: We Schmidts. Helmut and Loki Schmidt in conversation with Giovanni di Lorenzo , first broadcast: 25 February 2009, (ARD), summary of the ARD

- 2009: experiences and insights. Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Markus Spillmann and Marco Färber, NZZ online (53 min.) On December 6, 2009 ( Helmut Schmidt - experiences and insights - video )

- 2010: Helmut Schmidt and Fritz Stern in conversation with Reinhold Beckmann, ARD (75 min.), February 22, 2010

- 2010: What do you think, Helmut Schmidt? in conversation with Sigmund Gottlieb , BR (“Münchner Runde”, 45 min.) on March 2, 2010

- 2010: More responsibility! Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Christhard Läpple, ZDF, aspekte , June 26, 2010

- 2010: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Sandra Maischberger , ARD (“Maischberger”, 75 min.) On December 14, 2010

- 2011: Helmut Schmidt and Peter Scholl-Latour in conversation with Reinhold Beckmann, ARD (75 min.) On May 2, 2011

- 2011: Helmut Schmidt and Peer Steinbrück in conversation with Günther Jauch , ARD (60 min.) On October 23, 2011

- 2011: Helmut Schmidt - His century, his life ; Studio Hamburg / NDRfernsehen / Die Zeit - Documentation; DVD compilation with five DVDs: 1. In conversation - The political studio - A portrait of the Federal Chancellor , 2. A man and his city , 3. A man named Schmidt , 4. Helmut Schmidt - My Century , 5. Statesman and Hanseatic .

- 2012: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Sandra Maischberger , ARD (75 min.) On August 7, 2012.

- 2012: Why still believe in Europe? - Federal President Joachim Gauck and former Chancellor Helmut Schmidt on Maybrit Illner , ZDF (60 min.) On September 27, 2012.

- 2012: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Wolfgang Schäuble , Phoenix (Wirtschaftsforum des Zeitverlages, 44 min.) On November 10, 2012

- 2012: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Siegmund Gottlieb , BR ("Münchner Runde", 45 min.) On November 20, 2012.

- 2013: Helmut Schmidt and Yu-chien Kuan in conversation with Reinhold Beckmann, ARD (75 min.) On May 2, 2013

- 2013: Helmut Schmidt - Lebensfragen , ARD (88 min.) From December 23, 2013.

- 2015: Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Sandra Maischberger , ARD (75 min.) On April 28, 2015.

- 2018: 100 years of Helmut Schmidt , NDR (45 minutes) from December 23, 2018

Web links

- Literature by and about Helmut Schmidt in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Helmut Schmidt in the German Digital Library

- Comprehensive bibliography at the University Library of the Helmut Schmidt University

- Helmut Schmidt. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Biography of Helmut Schmidt cosmopolis.ch

- Biography at the Federal Chancellery

- Helmut Schmidt Archive ( Memento from November 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) in the archive of social democracy of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (Bonn)

- Helmut Schmidt, "Zeit" editor and former Federal Chancellor in conversation with contemporary witnesses , Deutschlandfunk on June 30, 2011

- ARD special for Helmut Schmidt's 95th birthday

- Virtual tour in the house and on the property of Helmut and Loki Schmidt, website of the Helmut and Loki Schmidt Foundation

- Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Klaus Bresser , in the series Witnesses of the Century , created in the project Memory of the Nation ( Interview - December 21, 1989 - duration 1:04:57 h).

- Archive recordings with and about Helmut Schmidt in the online archive of the Austrian Media Library

- Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt Foundation ( online )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Biography Helmut Schmidt , Who's who Germany.

- ↑ Wrong mixed with wrong . In: Der Spiegel . No. 20 , 1981 ( online - interview with Helmut Schmidt).

- ↑ Hartmut Soell : Helmut Schmidt , vol. 1, p. 87. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-421-05352-9 .

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt and the Scheißkrieg: The biography 1918 to 1945 of Sabine Pamperrien , accessed September 3, 2019

- ↑ a b Hartmut Soell: Helmut Schmidt: 1918–1969. Common sense and passion. DVA, Munich 2004.

- ↑ Michael Wolffsohn : From First Lieutenant to Soldier Chancellor? Helmut Schmidt, the fate of the Jews in the “Third Reich” and the German resistance against Hitler . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , December 16, 2014, p. 6.

- ↑ Jonathan Carr: Helmut Schmidt. Econ, Düsseldorf / Wien 1985, p. 29. Two pictures from 1942 also show the Iron Cross: Hartmut Soell: Helmut Schmidt: 1918–1969. Common sense and passion. DVA, Munich 2004, between pp. 272–273. Jonathan Carr: Helmut Schmidt. Econ, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1985, between pp. 136–137 (wedding photo). On the Leningrad blockade see Alex J. Kay: Starvation according to plan . In: Friday , January 23, 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Wibke Bruhns : A German family history . Klangkontext.de, biography.

- ↑ a b Heinrich August Winkler : The wood from which chancellors are carved . In: Die Zeit , No. 42/2003.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt . whoswho.de, rasscass media and content publishing house.

- ↑ Sabine Pamperrien: Helmut Schmidt and the shitty war. The biography from 1918 to 1945 . Piper Verlag, Munich 2014.

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe : To forget . In: Der Spiegel . No. 49 , 2014, p. 48-49 ( online ).

- ^ Hans-Joachim Noack: Helmut Schmidt. The biography . Rowohlt, Berlin 2008 (4th edition 2009), ISBN 978-3-87134-566-1 .

- ^ Post on cosmopolis.ch.

- ↑ Interview in Zeit-Magazin , No. 17/2008, category life .

- ↑ Schmidt: Cool head and crisis manager . In: NDR.de. As of November 10, 2015, accessed June 17, 2016.

- ^ Helmut Schmidt - Minister of Defense from 1969 to 1972, Federal Ministry of Defense

- ↑ a b own statements in an interview in the show Beckmann from 25 September 2006 ( Memento of 12 April 2009 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Jochen Wiemken: A Moving Life ( Memento from December 7, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on May 26, 2019.

- ↑ Our soldiers did not have a collective honor . In: Die Welt , December 20, 2008; Conversation with Ulrich Wickert .

- ↑ Helmut Stubbe da Luz : “The Basic Law not looked at”, “excited chickens” found. Helmut Schmidt, the rescuer from the disaster. In: Great disasters in Hamburg. Human failure in history - defensive urban development for the future? Accompanying volume for the exhibition “Great Disasters in Hamburg” at the Helmut Schmidt University / University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg , Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-86818-094-7 , pages 99–153

- ↑ "Helmut Schmidt: Others acted immediately", interview with Helmut Stubbe da Luz in ZEIT Hamburg no 30/2018 from July 19, 2018

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe: "Invented and exaggerated" , SPIEGEL, April 18, 2020. p. 45, with reference to the research results of Helmut Stubbe da Luz

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe , Georg Bönisch, Georg Mascolo : Renamed in the Strauss affair . In: Der Spiegel . No. 39 , 2012, p. 74, 75 ( online interview).

- ↑ bundestag.de

- ^ A b Giovanni di Lorenzo : "I am entangled in guilt" In: Die Zeit , August 30, 2007 (interview).

- ↑ Joachim Scholtyseck : The FDP in the turn. In: Historisch-Politische Mitteilungen , Volume 19, Issue 1, January 2013, pp. 197 ff., ISSN (Online) 2194-4040, ISSN (Print) 0943-691X ( PDF ).

- ↑ Information on all German Federal Chancellors Deutsche-Bundeskanzler.de, accessed on September 28, 2013.

- ^ Farewell speech in the Bundestag, 10 Sep. 1986 youtube.de, audio only, accessed on September 28, 2013.

- ↑ Correspondence between Helmut Schmidt and the members of the Seeheimer Kreis dated December 8, 1987 seeheimer-kreis.de ( Memento dated November 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

-

↑ see:

- Helmut Schmidt: Out of service . Siedler Verlag, Munich, 2008, p. 165.

- Theo Sommer , essay on Helmut Schmidt's 90th birthday. Zeit Online , April 21, 2009.

- Wolfgang Lienemann: Peace: from “just war” to “just peace” . In: Bensheimer Hefte , Heft 92, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, p. 52.

- Christian Hacke, Manfred Knapp, Christoph Bertram: Peacekeeping and Arms Control in Europe . Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1989, p. 58.

- Michael Salewski: The nuclear century: an interim balance . In: Historische Mitteilungen , Einheft, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998, p. 258.

- ↑ Helmut and Loki Schmidt Foundation with a virtual tour of the museum

- ↑ Politics needs reason more than religion . In: Katholisches Sonntagsblatt , May 20, 2007, p. 2.

- ↑ Press and Information Office of the Federal Government (ed.): Gedenken an Bundeskanzler a. D. Helmut Schmidt. State ceremony in the main church St. Michaelis in Hamburg on November 23, 2015 . Program of the State Act. Berlin January 31, 2016 (27 pages, online ( memento from November 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 5.9 MB ; accessed on November 10, 2016]). Memory of Federal Chancellor a. D. Helmut Schmidt. State ceremony in the main church St. Michaelis in Hamburg on November 23, 2015 ( Memento from November 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ State act for Helmut Schmidt: Hamburg and the world bow at tagesschau.de, November 23, 2015 (accessed on November 23, 2015).

- ↑ knerger.de: The grave of Helmut and Loki Schmidt

- ^ The Langenhorn Chancellor Museum . Hamburger Abendblatt, abendblatt.de. November 13, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- ↑ The library as an exhibit: Helmut Schmidt's house becomes a museum . n-tv.de. November 13, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- ↑ European unification . In: Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt Foundation . ( helmut-schmidt.de [accessed on March 26, 2018]).

- ↑ Global Markets and Social Justice . In: Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt Foundation . ( helmut-schmidt.de [accessed on March 26, 2018]).

- ↑ The open society in crisis . In: Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt Foundation . ( helmut-schmidt.de [accessed on March 26, 2018]).

- ↑ “Don't come to us in 1945!” . In: Die Zeit , No. 38/2005; Interview with Schmidt and Biedenkopf.

- ↑ Björn Hengst: Helmut Schmidt praises Schröder's agenda . In: Spiegel Online - Politik , October 27, 2007.

- ↑ The theses: Helmut Schmidt: Whoever wants to fight unemployment effectively must deregulate . In: Die Zeit , No. 15/1997.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt: Out of service. 2008, pp. 213-269.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt: SPD will tip nuclear phase-out. In: Hamburger Abendblatt , July 24, 2008.

- ↑ "The euro crisis talk is careless chatter" In: Handelsblatt , October 19, 2011.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt: Multicultural Society "Illusion of Intellectuals" . NA press portal, April 20, 2004.

- ↑ Holger Dohmen: Schmidt: Multiculturalism is hardly possible. In: Hamburger Abendblatt , November 24, 2004.

- ↑ of age at 18? Helmut Schmidt doesn't think so. In: Now , November 11, 2007.

- ↑ Patrick Bahners , Frank Schirrmacher : The situation was not that safe. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , December 23, 2008 (interview).

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt: Turkey does not fit into the EU. In: Hamburger Abendblatt , December 13, 2002.

- ↑ Kai Diekmann , Hans-Jörg Vehlewald : “The G8 summit is just a spectacle” In: Bild , June 3, 2007 (interview).

- ↑ Climate debate “pure hysteria” In: Rheinische Post , June 4, 2007.

- ↑ Responsibility of Research in the 21st Century . Max Planck Society. January 11, 2011. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ↑ a b c The "coolest guy" in the republic. Gabriele Gillen in conversation with Helmut Schmidt. WDR5, October 5, 2011.

- ↑ Harald Steffahn: Helmut Schmidt. rowohlts monographien, Rowohlt, Reinbek 1990 (2nd edition May 1993), ISBN 3-499-50444-8 .

- ↑ Craig R. Whitney: The ex-chancellor talks about his experiences with American and Soviet statesmen, about German contemporary history and a long-kept secret. Review. An interview with Helmut Schmidt. In: The best of Reader's Digest . February 1985, p. 58 f.

- ^ Helmut Schmidt: Political review of an apolitical youth. In: Helmut Schmidt, Hannelore Schmidt u. a .: Childhood and youth under Hitler . Siedler, Berlin 1992, Goldmann TB 1994, ISBN 3-442-12851-X , pp. 209-282.

- ↑ Loki Schmidt about her church wedding on the website of the parish Hambergen. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ↑ “We don't want to complain” In: Stern , December 16, 2008 (interview with Susanne Schmidt ).

- ↑ The Germans remain an endangered people . Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. April 8, 2005. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Then it rumbles in the chest ..." In: Der Spiegel . No. 43 , 1981 ( online ).

- ↑ "Power and Powerlessness" In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , May 17, 2010.

- ↑ We see big business with disgust . FAZ .net, June 13, 2007.

- ↑ Hand on heart. Helmut Schmidt in conversation with Sandra Maischberger , 2002.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt's Neue looks very similar to Loki. In: Focus , August 2, 2012; Helmut Schmidt's last love. Ruth Loah died at the age of 83 , Focus online, March 12, 2017

- ↑ Acceptance speech by Helmut Schmidt for the Eric M. Warburg Prize ( Memento from December 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 183 kB)

- ^ Helmut Schmidt - the German chancellor. Documentation, ZDF 2008.

- ↑ Renate Pinzke: Large funeral in Michel Siegfried Lenz. In: Hamburger Morgenpost , October 27, 2014; see. also: Jörg Magenau: Schmidt-Lenz - history of a friendship , ISBN 978-3-455-50314-2 , (book tip on hoffmann-und-campe.de).

- ↑ Volker Gerhardt: Ethics of Action . In: Die Welt , December 23, 2008.

- ^ Susanne Miller : The SPD before and after Godesberg. In: Susanne Miller, Heinrich Potthoff: Brief history of the SPD, presentation and documentation 1848–1983. Verlag Neue Gesellschaft, Bonn, 5th revised. 1983 edition, ISBN 3-87831-350-0 , p. 228.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt is the most popular politician in recent German history . Discovery story. August 17, 2005. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ↑ Press releases from January 6, 1999 . Press office of the Hanseatic City of Hamburg. January 6, 1999. Archived from the original on September 23, 2004. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt is said to be a Swabian. In: Hamburger Abendblatt , May 18, 2007.

- ↑ The Power of Orders - How They Motivate and Manipulate. In: Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung , February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Nell Breuning Prize "great honor" for Helmut Schmidt , website of the city of Trier.

- ↑ List of previous winners of the Adenauer-de (…) - France-Allemagne.fr. In: deutschland-frankreich.diplo.de. Retrieved November 10, 2015 .

- ↑ American Academy press release. (PDF) American Academy in Berlin , May 30, 2007, archived from the original on June 28, 2007 ; accessed on February 24, 2011 (English): "As a publisher, he remains a pre-eminent catalyst of transatlantic dialogue and debate."

- ↑ World Economy Prize 2007 ( Memento from February 23, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), Institute for World Economy at the University of Kiel.

- ↑ Mendelssohn Prize 2009 . Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ Point Alpha Prize: Former Chancellor Schmidt honored for political services. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine , June 17, 2010.

- ↑ Helmut Schmidt receives Point Alpha Prize 2010. In: Frankfurter Rundschau . January 3, 2010.

- ↑ Responses to Helmut Schmidt. In: Westfälische Nachrichten , September 22, 2012.

- ↑ Ulrich Clauß: Schmidt is “deeply touched” by the Schleyer family. In: Die Welt , April 26, 2013.

- ↑ Freemasons award the Stresemann Prize to Helmut Schmidt. In: Grand Lodge of the Old Free and Accepted Masons of Germany , January 27, 2015.

- ↑ Honorary Senators of the University of Hamburg ( Memento from June 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ koerkel: Helmut Schmidt received an honorary doctorate from the Philipps University. As part of the traditional Christian Wolff lecture, Schmidt spoke about “Conscience and Responsibility of Politicians” - CF Gethmann, President of the German Society for Philosophy, gave the keynote address. Philipps University of Marburg , March 7, 2007, accessed on February 24, 2011 .

- ^ Charles Maier wins Helmut Schmidt Prize in German-American Economic History , Harvard University website (English).

- ↑ Edgar S. Hasse: Helmut Schmidt and the bird that cannot fly. In: The world. November 6, 2012, accessed May 19, 2015 .

- ↑ Hamburger Pressehaus renamed the Helmut Schmidt House ( memento from January 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), www.zeit.de, accessed on May 26, 2019.

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung, December 11, 2015: Hamburg is getting the Helmut Schmidt Airport , sueddeutsche.de from December 11, 2015, accessed on October 30, 2016.

- ↑ Hamburg Airport is preparing to pay tribute to Federal Chancellor a. D. Helmut Schmidt vor , Airport website from October 10, 2016, accessed on October 30, 2016.

- ↑ https://bernau-live.de/aus-der-pappelallee-in-bernau-wird-nun-die-helmut-schmidt-allee

- ↑ Oliver Seibel, DIE RHEINPFALZ: Südtangente is renamed "Helmut-Kohl-Straße". Retrieved July 3, 2020 .

- ↑ Federal Minister Altmaier issues 2 euro coins “100. Birthday Helmut Schmidt ”and“ Berlin ”in the Federal Chancellery before - Federal Ministry of Finance - Press. Accessed January 31, 2018 (German).

- ↑ Deutsche Post honors Helmut Schmidt with a special postage stamp. In: Welt.de December 7, 2018.

- ↑ About the foundation

- ↑ Table of contents (PDF; 50 kB)

- ↑ a b c Daniela Münkel : collective review Helmut Schmidt . In: H-Soz-u-Kult . November 9, 2009 ( PDF , 93 kB).

- ^ NDR: 100 years of Helmut Schmidt. Retrieved November 13, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schmidt, Helmut |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schmidt, Helmut Heinrich Waldemar (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (SPD), Member of the Bundestag, MEP, Federal Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (1974–1982) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 23, 1918 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hamburg-Barmbek |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 10, 2015 |

| Place of death | Hamburg-Langenhorn |