Kosovo

|

Republika e Kosovës ( Albanian ) Republika Kosovo / Република Косово ( Serbian ) Republic of Kosovo |

|||||

|

|||||

| Official language | Albanian and Serbian 1 | ||||

| Capital | Pristina | ||||

| Form of government | parliamentary democracy | ||||

| head | President Hashim Thaçi | ||||

| Head of government | Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti ( LDK ) | ||||

| surface | 10,877 km² | ||||

| population | 1,907,592 (July 2018) | ||||

| Population density | 159.8 inhabitants per km² | ||||

gross domestic product

|

2019 | ||||

| Human Development Index | 0.742 2 (82nd) 3 (2016) | ||||

| currency | Euro (EUR) 4 | ||||

| independence | February 17, 2008 (from Serbia ) | ||||

| National anthem |

Evropa |

||||

| National holiday | February 17th | ||||

| Time zone |

UTC + 1 CET UTC + 2 CEST (March-October) |

||||

| License Plate | RKS | ||||

| ISO 3166 | not assigned sometimes alternatively: XK, XKX |

||||

| Telephone code | +383 | ||||

| The independence of Kosovo is controversial under international law. The Republic of Kosovo has so far been recognized by 114 UN member states.

2The Republic of Kosovo is not a member of the UN and is therefore not included in the Human Development Report . The United Nations Development Program uses the same methods to calculate a value for the HDI, but publishes it separately.

3For the reasons mentioned above, the Republic of Kosovo is also not included in the HDI ranking list. Due to the separately calculated HDI value, however, this can be fictitiously assigned to 82nd place in the official 2014 ranking list.

|

|||||

Kosovo (also Kosovo or Kosovo , Albanian Kosova / Kosovë , Serbian - Cyrillic Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo , is a republic in Southeastern Europe on the western part of the Balkan Peninsula . It was formerly part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia , then the newly constituted Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1992 and a sub-region of the Republic of Serbia since 2003 . The Republic of Kosovo has around 1.9 million inhabitants and is considered a stabilized de facto regime . The capital and largest city is Pristina . Recent history is shaped by the Kosovo war of 1999 and its consequences. The country's international legal status is controversial. On 17 February 2008, the proclaimed parliament , the independence of the territory. 114 of the 193 member states of the United Nations recognize the Republic of Kosovo as an independent state.

While the membership of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was formally maintained , Kosovo was placed under the administrative sovereignty of the United Nations after the war in 1999 . The basis of international law was Resolution 1244 of the UN Security Council , which guarantees the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, whose legal successor is today's Serbia . Furthermore, since December 9, 2008, political developments have been monitored by EULEX Kosovo . This also applies to the region of northern Kosovo , which is predominantly inhabited by Serbs and which is currently only partially controlled by the Kosovo government .

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) reached on 22 July 2010 in a non-legally binding, the UN General Assembly requested on Serbian initiative opinion to the conclusion that the declaration of independence of Kosovo did not violate international law. At the same time, the ICJ avoided assessing Kosovo's status under international law and recognized the validity of UN resolution 1244.

The Serbian government considers the Kosovo formally as its Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija ( Serbian Аутономна покрајина Косово и Метохија Autonomna Pokrajina Kosovo i Metohija , shortly Космет / Kosmet , Albanian Krahina Autonomous e Kosovës dhe Metohisë ), but acknowledges that a "Serbian sovereignty about Kosovo is practically non-existent ”and the“ true borders ”of Serbia have yet to be determined in the future.

The country has been a member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group since June 2009 . Since November 2012 it has also been part of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development .

Names and etymology

Kosovo usually refers to the entire area. Also in Serbo-Croatian is Kosovo synonymously used. In addition, nationally conscious Serbs use the term cosmet , a combination of words from Kosovo and Metohija , in parallel.

Kos refers to the blackbird in Serbo-Croatian . The region is named after the blackbird field (Serbian Kosovo Polje , Albanian Fushë Kosovë ) near Pristina. The word kosovo is a possessive adjective (“belonging to the blackbird”) and therefore actually incomplete without an additional polje (“field”). However, the abbreviation has become common in this form.

The name Metochien for the west of Kosovo is derived from the Greek μετο met ( metochí "monastery property "). This name, which describes a landscape shaped by many churches and monasteries, was no longer used by the state in Yugoslavia from 1974. The Kosovar Albanians call this region Dukagjini or Rrafshi i Dukagjinit .

Dardania or Dardania is a common historicizing name for Kosovo among Albanians. It is derived from the ancient Illyrian people of the Dardans who lived in the area of today's Kosovo. It comprised today's territory of Kosovo, as well as some areas in southern Serbia and in North Macedonia . In October 2000 the future President Ibrahim Rugova presented his proposal for a future flag of Kosovo . On it was a banner with the designation "Dardania", which Rugova proposed as the country name of an independent Kosovo.

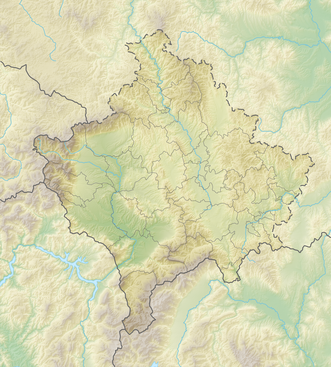

geography

Kosovo is inland in the center of the Balkan Peninsula . It borders Albania in the southwest , Montenegro in the northwest , Serbia and central Serbia in the north and east, and North Macedonia in the southeast . Tectonically, the leveling of the Blackbird Field and Metochiens are entirely bounded by mountains. The mountain groups of the Prokletije delimit Kosovo from Montenegro and Albania, the Kopaonik from Serbia and the Šar Planina from North Macedonia.

At 10,877 km², Kosovo, the smallest country in Southeast Europe, has about two thirds of the area of Thuringia and is relatively densely populated with 195 inhabitants per square kilometer. 53% of the area is used for agriculture, 42% is forest area and 5% is built-up or urban area.

Due to the spatial structure of a valley surrounded by high mountains, Kosovo has always been an important agricultural region - the Amselfelder wine is well known - as well as the center of the Balkan pastureland , in which the Metochian lowlands in particular were used as winter pastures and in the 19th century by the Thessalians and north Serbian shepherds was visited. A specialty of cattle breeding is the use of water buffalo , which in some cases continues to this day .

In terms of settlement geography, the higher-lying Amselfeld with the capital Pristina, which stretches between the Ibar and the southern Morava as a long depression, is now the economically more important region. Historically, Metochien with the oldest urban centers of Prizren , the old Roman administrative center and the later Serbian imperial city, as well as Peja were more important. The plains are separated from each other by a hilly, low mountain range, largely overgrown by loose oak forests, which makes communication routes difficult.

The high mountain landscapes on the borders with Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia consistently reach 2500 m . The highest mountains are Rudoka (in the Šar Planina, 2658 m), Gjeravica (in the large municipality of Peja , 2656 m ), Bistra ( municipality of Ferizaj , 2640 m ), Marjash (Peja, 2530 m ), Ljuboten (Alb.Luboten, Ferizaj, 2496 m ) and Koproniku (Peja, 2460 m ). Mostly made up of silicate rocks, the mountains are usually rich in water and well suited for keeping cattle. From Cretaceous limestones are Karst as the Koproniku as well as the central portions of the Sar Mountain with the Bistra constructed so that even less accessible and a lower water content.

Waters

The White Drin , which rises near Peja, flows through the west of the country . The Drin is the most important and with about 113 km the longest river in Kosovo. Some reservoirs are located inland and on the borders with Serbia and Albania. The largest of them is gazivoda lake km² with 11.9, followed by Radoniq Lake and the Batllava Lake .

Numerous glacial lakes can be found particularly in the Šar Planina. In the metochian Prokletije, three small lakes around the Gjeravica are left as evidence of the ice age of the mountains.

climate

Because of its inland location, Kosovo has a predominantly continental climate . Depending on the geographic location, however, the continental climate characteristics are different. For this reason, Kosovo is subdivided into three climatic regions, namely the blackbird field, metochia (alb. Dukagjin ) and mountainous and forested parts.

In the area of the blackbird field, which includes the eastern half of the country with the capital Pristina, the continental climate is predominant. The winters are cold with an average temperature of −10 ° C, but can also reach lows of −26 ° C. The summers, on the other hand, are very warm with an average temperature of 20 ° C, but temperatures of up to 37 ° C are not uncommon. This region is also characterized by a rather dry climate, as the annual rainfall averages around 600 mm.

In Metohija, which occupies the western half of the country, the continental climate is strongly influenced by the warm air masses of the Mediterranean Sea . The average daytime temperature in winter is between 0.5 and 22.8 ° C. The average annual rainfall in this region is around 700 mm. Heavy snowfalls are typical in winter.

The third climatic region comprises the mountainous regions to Montenegro, Albania and North Macedonia as well as the wooded parts of the hill and mountainous country in the center and in the north of Kosovo. In contrast to the other two regions, more precipitation falls here (between 900 and 1300 mm annually). And while summers are fairly short and mild, winter is usually cold and rainy.

For the whole of Kosovo, December and January are the coldest months and July and August are the warmest months of the year. Most of the precipitation falls between October and December.

population

| Statistical data (2006) | |

|---|---|

|

Life expectancy years |

69 |

|

Death rate per 1,000 people |

3.56 |

|

Birth rate per 1000 inhabitants |

16.7 |

|

Population density inhabitants per km² |

166.7 |

| Urban population | 35-40% |

| Population under 18 years of age | 46% |

| Population over 65 years | 6% |

At the 2011 census, the Republic of Kosovo had around 1.8 million inhabitants. The average birth rate (TFR) is 2.3 children per woman (as of 2015) The population is the youngest on average in Europe: In 2006, 33% were under 16 years old, over half of the population was under 25 years old, only 6% over 65 years. Figures from 2017 indicate that an aging process has also occurred here. At this point, half of the population was under 29.1 years of age. The birth rate currently clearly exceeds the death rate: 23 births per 1000 inhabitants were compared to seven deaths per 1000 inhabitants in 2003. The life expectancy for women is 71, that of men 67. The proportion of the rural population is between 60 and 65%. In addition to the roughly 1.8 million inhabitants of Kosovo, around 420,000 Kosovars live and work abroad, mainly in Germany , the United States , Austria and Switzerland .

Ethnic structure

The proportion of Kosovar Albanians has risen steadily over the last century as a result of the above-average birth rates and the emigration of Serbs. Kosovo already had a non-Serb majority in 1912 when Ottoman rule ended. When was the last time or whether there was ever a Serb majority is controversial among historians .

The vast majority of Kosovo is now inhabited by Albanians. World Bank estimates from 2000, followed by the statistical office of Kosovo to this day, assume 88% Albanians, 7% Serbs and 5% of the other ethnic groups. The latter mainly include Turks , Bosniaks , Torbeschen , Gorans , Janjevci (Croats), Roma , Ashkali and Balkan Egyptians . After the war in 1999, part of the Serbian minority was expelled. Today the north of Kosovo in particular is predominantly populated by Serbs who do not recognize the Albanian-led government in Pristina and who refused to cooperate with it in a referendum in 2012 with 99.74%.

Linguistic landscape

The official languages are Albanian and Serbian , in some communities also Turkish , Bosnian and Romani . English also had official status under the UNMIK administration .

religion

Article 8 of the Constitution defines the Republic of Kosovo as a secular state that is neutral on issues related to religious beliefs. There are religiously colored political parties, but they advocate secular state structures and often do not reach the necessary five percent hurdle in parliamentary elections . Politicians from all camps stand up for religious harmony and see this as a value to be protected in Kosovar society.

Kosovar society is also heavily secularized . Many deal with religion loosely and have a pragmatic relationship with it. Nonetheless, when asked in 2010 whether religion is an important part of their everyday life, 89% of Albanians in Kosovo answered yes. The proportion of Serbs in Kosovo was a little lower at 81%. The Gallup Organization survey responded to 1,000 people.

The Islam has the most followers in the country. There are also Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholic minorities. The proportion of atheists is low. Traditionally, Albanians, Bosniaks, Turks and Gorans belong to the Muslim faith. The majority are Sunni . According to the 2011 census, 95.61 percent of the population of Kosovo was Muslim. Most of the Serbs belong to the Serbian Orthodox Church . In 2011, 1.49 percent of the population of Kosovo (excluding Northern Kosovo ) were Orthodox. The number of Catholics was given in 2011 with 38,438 believers, which makes 2.21 percent of the population. The majority of these are Albanians, the few also Roman Catholic members of the Janjevci , the Croatian minority, almost all of them fled after the Kosovo war. The Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian groups contain followers of all three faiths.

The relationship between Muslim and Roman Catholic communities in Kosovo is considered good, but both groups have little or no relationship with the Serbian Orthodox Church. Kosovar Albanians define their ethnicity by language, not by belonging to a particular religion. In contrast, among the Slavic ethnic groups , both the Muslim Bosniaks and the Orthodox Serbs, religion is seen as a characteristic of identity .

Islam

Islam has a tradition of over 500 years in Kosovo and is the religion with the most followers. The Kosovar Muslims are almost exclusively Sunnis . The Islamic Community of Kosovo ( Albanian Bashkësia Islame e Kosovës ; Serbian Islamska Zajednica Kosova ; Turkish Kosova İslam Topluluğu ) is their official representative and organizes, for example, the management of most mosques. She also takes zakat from believers and uses it to carry out charitable activities. The imams are trained at the Faculty of Islamic Studies in Pristina; Budding Albanian imams from Albania, North Macedonia and Montenegro also study there.

In addition, since the spread of Islam in the 15th century, there have also been many dervish orders and Sufi brotherhoods. Sufism in Kosovo is considered to be a mixture between the Sunni and Shiite faiths . Members of the Bektashi order, whose center is in the Albanian capital Tirana , were leaders in the Albanian national movement of the 19th century.

Before the Kosovo war there were 560 mosques and 60 Tekken of the Sufi brotherhoods, the latter mainly in the western cities of Peja , Gjakova , Rahovec and Prizren . 218 mosques and five tekken were destroyed during the war. In December 2010, 660 mosques were counted, of which 607 were active, 25 under construction and 28 inactive. With 77 mosques, Prizren has most of the Islamic places of worship.

Serbian Orthodox Church

Kosovo is an important center of the Serbian Orthodox Church and is home to the Archbishopric of the Patriarchate of Peć and the Raszien-Prizren eparchy . Some of the most important and oldest churches and monasteries of the Serbian Orthodox Church, in particular the Visoki Dečani and Gračanica monasteries , are located in Kosovo ( see also: List of cultural monuments in Kosovo ). The autocephalous Serbian Orthodox Church sees itself as the guardian of a Serbian culture and identity. During the reign of Slobodan Milošević , large parts of the clergy initially supported his policy. When the negative consequences for the Serbs themselves became more and more apparent, they kept their distance. After the NATO air strikes ended in 1999, according to UNMIK representatives, 76 Serbian Orthodox churches, monasteries and chapels were destroyed. In the period after the KFOR invasion , the Serbian Orthodox Bishop Artemije von Raszien and Prizren and the monk Sava from Dečani Monastery initially became political spokesmen for those Kosovar Serbs who were in favor of cooperation with UNMIK. In recent years, however, the clergy have largely relinquished their role as spokesman for the Serbs to Kosovar Serb politicians. During the violent riots in March 2004 , Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries were again destroyed, whereupon the KFOR increased the protection of these buildings.

Roman Catholic Church

There are over 38,000 Roman Catholic Albanians, plus a small group of Roman Catholic Roma and Croats. They are divided into 23 parishes in which 55 priests work. Until 2000, the Roman Catholic Kosovars belonged to the Diocese of Skopje and Prizren, then the North Macedonian part was separated and an independent Apostolic Administration Prizren (since 2018 Diocese Prizren-Pristina ) was formed. Catholics founded the Albanian Christian Democratic Party of Kosovo , with a high number of Muslims among the members of the PSHDK. Most of the Roman Catholic priests belong to the Franciscan order and were trained in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia or Slovenia.

The Holy See is represented in Kosovo by an Apostolic Delegate . Since March 19, 2019, this has been Archbishop Jean-Marie Speich .

education

The percentage of illiterate women is significantly higher than that of men: 13.4% in rural areas (3.8% for men) and 10.4% in urban settlements (2.3% for men). Illiteracy correlates not only with gender, but also with age - in the group up to 39 years of age the rate is far below the average, among women between 55 and 59 years of age it is almost 20%, among women between 70 and 74 years of age it is almost 60 % Illiterate.

Classes in primary school in the country are conducted in one of the five languages Albanian, Serbian, Bosnian, Turkish and Croatian, depending on the situation in the municipality, and are compulsory and free of charge for all children. Most recently, the Kosovo government published plans to reform the entire education system. Among other things, these provide for middle school to be made compulsory. The reforms are named as a priority by the government, but the lack of funds, technological and professional resources for teaching and the high number of students per class are obstacles to comprehensive educational reform .

During the 2005/06 school year, a total of 423,220 students were registered in the pre-school, elementary and middle school levels. 22,404 teachers taught them. This corresponds to approx. 19 students per teacher.

In 1970 the University of Prishtina was opened. In the 2005/06 school year 28,707 students and 980 professors were registered. That made an average of 29 students per course .

In the 2015 PISA ranking , Kosovo's students ranked 70th out of 72 countries in mathematics, 70th in science and 71st in reading comprehension.

history

antiquity

The area of the later Kosovo was inhabited by the Illyrians in antiquity ; Thus the Roman Theranda near today's Prizrens was originally an Illyrian settlement. The Illyrians in Kosovo were in close proximity to the Thracians in the east . After the defeat of Queen Teuta ruled Illyrian kingdom of Labeaten in the first Illyrian war 229/228 v. The region came under Roman rule . It was only after decades of military conflict between Romans and Illyrians that the area became known in 168 BC. A protectorate of the Roman Empire. Since 59 BC Chr. As Illyrian province referred to, this was only after the wars Octavian v in Illyria 35-33. Officially to the Roman province . After further conquests by the Romans and the establishment of the province of Moesia, the later Metochien remained with Illyricum , while the blackbird field Moesia superior was added. Besides Theranda, Ulpiana near Pristina was the most important Roman settlement in Kosovo. After the division of the empire under Theodosius I , the region finally came under Byzantine rule .

middle Ages

With the migration of the Avars and the sacking and capture of the most important Byzantine cities in Moesia and Illyria ( see also: Maurikios' Balkan campaigns ), Slavs settled in the 7th century . In the 9th century, northwestern Kosovo around Peja belonged to the Serbian state of Vlastimirovi ć, while southeastern Kosovo with Prizren and Pristina belonged to the Bulgarian Empire . The region was only recaptured by the Byzantines under Basil II in 1018. In the 11th century, the Serbian Raszien expanded southwards under the sovereignty of Dioklitiens , Konstantin Bodin was proclaimed emperor of the Bulgarians in Prizren as a result of a Slavic uprising against Byzantium in 1072 . The uprising was unsuccessful, however, the south of Kosovo came under Byzantine rule again, while the north remained with Raszien, now under Byzantine suzerainty. This rule was strengthened with the battle of Sirmium under Manuel I. Komnenos also against Hungary .

The involvement of the Raszian Großžupan Stefan Nemanja as a Byzantine vassal and the missionary work and cultural imprinting of the Serbian court by Ostrom was followed by the formation of the Serbian Nemanjid Empire in formerly Byzantine areas in Kosovo. In the Nemanjid Empire, Kosovo became the political, economic and cultural center of the Serbian state due to its natural resources and the trade routes from the coast to the interior of the Balkans. This bloom ended with the advance of the Ottomans . After several military clashes, the best known of which is the Battle of the Blackbird Field , the Ottomans conquered the region of today's Kosovo around 1454. The conquest of today's Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina , which began towards the end of the 14th century, was completed in 1459/1461 under Mehmet II . Kosovo, Serbia and Bosnia became provinces of the Ottoman Empire for the next four centuries .

Ottoman time

The myth of the Kosovo battle as well as the historical legacy in Kosovo established the emotional bond between the Serbs and the region, which is now largely inhabited by Albanians. The Albanians Islamized under the Ottoman rule moved into the fertile Kosovo area , including after the Great Exodus of the Serbs in 1690. In the 19th century the western Kosovo, Metohija, was mostly Albanian, while the east, the "historical" Kosovo, was mostly still Serbian. With the independence of the Principality of Serbia in 1878, there was another population shift when many Serbs left Kosovo or were forced to resettle, while Albanians also emigrated freely or under duress from the Principality. During this time, Eastern Kosovo also got an Albanian majority.

20th and 21st centuries

After the First Balkan War , what is now Kosovo was largely added to Serbia in 1912 and the area around Peja Montenegro . From 1918 it was then part of Yugoslavia . After the Balkan campaign was divided Mussolini on August 12, 1941 the annexed since April 1939 Albania , the one at that time Italian vassal state was Kosovo and some Macedonian territories to. However, this reorganization of the borders was only recognized by the Axis powers .

The Albanian militia in Kosovo expelled numerous Serbs during this time. After the German occupation in 1943, the 21st Waffen-Gebirgs-Division of the SS "Skanderbeg" (Albanian No. 1) was set up on May 1, 1944 , mainly from volunteers from Kosovo, as the occupation regime in Albania had already lost its support. This division was supposed to fight mainly against Yugoslav partisans. The members of the division, which never made it to the front and was only used by the Wehrmacht for guard duties, expelled around 10,000 Serb families and murdered numerous Serbs and Jews. In June the division also invaded Montenegro. It was dissolved on November 1, 1944. Then there were Serbian acts of revenge against the relatives.

After the Second World War, the Autonomous Region "Kosovo and Metohija" became part of the Socialist Republic of Serbia within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia on September 3, 1945, just like the Autonomous Region of Vojvodina . Full legal, economic and social equality between the sexes was first guaranteed in the 1946 Yugoslav constitution. With the redesign of the borders within Yugoslavia and the composition of Serbia with two autonomous provinces, the new political leadership under Josip Broz Tito, after the experiences of the interwar period, aimed to create a balance between the Serbs and the other nations of the country. For the Serbs, this conception of the state meant a weakening compared to their position in the interwar period, as they now represented large population groups in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina on the one hand and a predominantly Albanian population in the autonomous region of Kosovo and a strong Hungarian and Croatian population in Vojvodina on the other Had a minority. Another reason for this arrangement was that in the first few years after the war, Tito wanted Albania to be incorporated into a Balkan federation dominated by Yugoslavia, which Bulgaria should also have joined.

With the Yugoslav Constitution of 1963, the Autonomous Region of Kosovo was converted into an Autonomous Province ( Kosovo-Metohija , in short 'Cosmet'), which formally meant a better position, but in fact led to a greater dependence on the Republic of Serbia, which increased the possibilities of political participation at the level of the Federal Republic decreased. As a concession to Serbia, the republics were given greater powers, especially for their policy towards the autonomous provinces.

Gradually since 1967, but especially with the amendment of the Yugoslav constitution in 1974, the previously formally already existing autonomy rights were considerably expanded and the right of co-determination in the federation was massively expanded.

In the 1980s, nationalist aspirations grew stronger among both Serbs and Albanians. Both ethnic groups complained of mutual discrimination. The Kosovar Serbs saw themselves disadvantaged by the predominantly Albanian provincial government and the Kosovar Albanians in turn by the Republic of Serbia. At the same time, voices were raised calling for a separate Republic of Kosovo within Yugoslavia or even a secession of Kosovo from the all-Yugoslav state association. Nationalist propaganda on both sides further heated the mood and favored, among other things, the seizure of power by Slobodan Milošević , who promised fundamental reforms.

The autonomy status of Kosovo from 1974 was severely restricted by a resolution of the Serbian parliament as part of the so - called anti - bureaucratic revolution of 1989 at the instigation of Slobodan Milošević and officially reset to the status of 1963. As a result, the most important Albanian politicians called for a boycott of all Serbian state institutions, the so-called non-violent resistance. Many Kosovars also fled during the Yugoslav wars, even though there were no acts of war in Kosovo itself. The Kosovar Albanians asked for asylum in various European countries and complained about the violation of their human and civil rights by the Milošević government. As a result of the boycott in 1989, there was no longer an Albanian-language school system in many places, Albanians were often arbitrarily expropriated, their associations and political parties were banned if they did not correspond to the political line of the Milošević government. Most of the Albanians employed in the civil service were reportedly dismissed after 1989 on the basis of their ethnicity . In September 1992 the Albanians in Kosovo declared themselves independent for the first time in a referendum . However, only Albania recognized the Republic of Kosova .

After the international community excluded extensive and functioning autonomy for Kosovo from the Dayton Peace Conference in 1995, the conflicts between the ethnic groups and the demand for state independence intensified . Separatist groups, including the Democratic League of Kosovo , set up the “Republic of Kosova”, a shadow state whose parallel institutions were supposed to ensure, among other things, school education and medical supplies for the Albanians. The long-term non-violent resistance turned into armed conflicts between Albanian militants and the Serbian armed forces from around 1996 under the leadership of the KLA . By 1999, the number of Albanian refugees from Yugoslav territory multiplied , especially in the direction of the neighboring countries Albania and North Macedonia as well as the European Union and Switzerland.

On the grounds of wanting to avert a humanitarian catastrophe, NATO began bombing strategic targets in Yugoslavia on March 24, 1999 after the failure of the conferences on the Rambouillet Treaty . As a result of the Kosovo war , Kosovo was occupied by international troops and a UN protectorate was established. During the war, the number of refugees jumped again, but then subsided and many Kosovars returned to their homeland.

The war was followed by excesses of violence, particularly against the Serbian minorities, but also against other minorities in the region. According to the human rights organization Human Rights Watch , KFOR did not provide adequate protection for Serbs and Roma in Kosovo, who were particularly exposed to attacks by the KLA. In August 1999, according to the UN, 170,000 of the 200,000 Serbs had fled the province and, according to the Serbian Orthodox Church, over 40 churches had been plundered or destroyed. While almost all Kosovar Albanians had returned within weeks of the end of the fighting, this was not the case for most of the refugee Serbs after more than four years, especially since 230,000 Serbs and non-Albanians were then forced to flee.

The violence reached a new high point with the pogrom-like riots in March 2004 , which were mainly directed against Serbs and their religious sites, but also against Roma and Ashkali; approximately 50,000 people participated in the violence, in which 19 people were killed, more than 1,000 injured and over 4,000 displaced. NATO then increased its presence.

Further riots occurred in the weeks after the proclamation of the republic - this time in northern Kosovo, which is mostly inhabited by Serbs . The violence could only be ended by the intervention of the KFOR troops.

Since the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) began, the future political status of Kosovo has regularly been on the international agenda. Even after the failure of the attempt to find an amicable solution with Serbia and the subsequent unilateral declaration of independence by the Kosovar parliament, the issue has still not been fully clarified.

On January 16, 2018, Oliver Ivanović , a politician from the Serb minority in Kosovo, was shot dead by unknown persons in front of his party's headquarters in Mitrovica . The talks scheduled for that day between representatives of Kosovo and Serbia in Brussels were initially canceled after the murder.

politics

executive

The state president is elected by parliament for five years. He guarantees the constitutional functioning of the political system , organizes parliamentary elections, can reject laws once if he considers them harmful, promulgates the laws, conducts foreign policy , receives diplomats , is commander in chief of the security forces , proposes the prime minister to parliament and can one Bring constitutional action. In addition, he has further representative tasks and powers of appointment. The president is politically immune .

The president was Fatmir Sejdiu ( LDK ) from February 10, 2006 to September 27, 2010 . He resigned because the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Kosovo ruled that the president could not be the party leader at the same time. Sejdiu had only let this party office rest. On a temporary basis, Parliamentary President Jakup Krasniqi ( PDK ) took over the rights and duties of the President of Kosovo. On February 22, 2011, the building contractor and politician Behgjet Pacolli of the Alliance for a New Kosovo (AKR), a coalition partner of the PDK of Thaçi, was elected by the parliament as the new head of state under controversial circumstances . On March 28, 2011, the Constitutional Court ruled that the election of the president was unconstitutional; it responded to a questionnaire from the political opposition . On April 7, Atifete Jahjaga was elected as the new President of the Parliament with 80 votes out of 100 possible. The current president is Hashim Thaçi .

The most important executive state body is the government. The prime minister is elected by parliament on the proposal of the president, the full government must be confirmed by parliament. The head of government can dismiss ministers without the consent of parliament. One minister must belong to the Serb minority and another to a different minority. If the cabinet has more than twelve members, a third minister must be assigned to a minority. On January 30, 2008, Hashim Thaçi (PDK) became Prime Minister of a multi-party coalition, which broke up in autumn 2010. On February 22, 2011, a new government was re-elected under his leadership, which in addition to the PDK also includes the AKR of Behgjet Pacolli and representatives of the Serbian minority.

legislative branch

The Parliament of the Republic of Kosovo ( Albanian Kuvendi i Republikës së Kosovës ; Serbian Skupština Republike Kosovo Скупштина Републике Косово ) is the country's legislative body . It has 120 seats, which are directly elected by the people every four years . Since February 3, 2020, Vjosa Osmani ( LDK ) has been appointed as Kosovar's first female parliamentarian.

The electoral system offers advantages for the many ethnic minorities in Kosovo. 100 of the 120 parliamentary seats can be filled freely. The 20 other parliamentary seats are reserved for Serbs, Roma, Ashkali, Balkan Egyptians, Bosniaks, Turks and Gorans.

After the results of the 2019 elections , self-determination became! the strongest force. In its sixth legislative period, the parliament is composed as follows:

| Political party | percent | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| Lëvizja Vetëvendosje! | 26.27% | 29 |

| Lidhja Demokratie e Kosovës | 24.55% | 28 |

| Partia Demokratie e Kosovës | 21.23% | 24 |

| Aleanca për Ardhmërinë e Kosovës | 11.51% | 13 |

| Srpska Lista | 6.04% | 10 |

| Nisma Social Democrats | 5.00% | 6th |

| VAKAT coalition | 0.84% | 2 |

| Kosova Democracy Turk Partisi | 0.81% | 2 |

| The Kosovar-Egyptian Liberal Party | 0.58% | 1 |

| New Democratic Party | 0.47% | 1 |

| Ashkali Party for Integration | 0.37% | 1 |

| New Democratic Initiative of Kosovo | 0.21% | 1 |

| Jedinstvena Goranska Partija | 0.14% | 1 |

| United Roma Party | 0.13% | 1 |

| All in all | 100% | 120 |

In the 2017 parliamentary elections on June 11, 2017, a radical alliance of parties of former Albanian rebel commanders won around 35 percent of the vote. The rebels are followed by the left-wing nationalist movement for self-determination Vetëvendosje! and a pacifist alliance led by former Finance Minister Avdullah Hoti.

Some legislative functions are reserved for the parliaments of the 38 large municipalities. These are also elected by the local electorate every four years and have a varying number of seats. The last local elections took place in October 2017.

In the election on October 6, 2019 , the opposition LVV under top candidate Albin Kurti won the relative majority of the votes with 26.27% for the first time . After several months of negotiations, LVV and LDK agreed on a coalition at the beginning of February 2020. The new Kurti government was elected on February 3, 2020. On March 25, 2020, however, Kurti was overthrown by a vote of no confidence and voted out by 82 of the 120 MPs. The Vice Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti ( LDK ) succeeded and was elected Prime Minister by 61 of the 120 MPs on June 3, 2020.

Parties

Civil society and political parties in Kosovo are divided along ethnic lines. The multi-party system is dominated by the two large Albanian parties, the LDK and PDK . The "Democratic League of Kosovo" (LDK), founded in 1989, was for a long time the main political force behind the resistance to Serbian rule and provided the later President Rugova. The “ Democratic Party of Kosovo ” (PDK) was the strongest party for a long time. It partially represents social democratic positions and is (since 1999) the most important political successor organization to the paramilitary organization UÇK . The current President of Parliament, Kadri Veseli, is the chairman of the PDK . Since the last parliamentary elections in June 2017, the left-wing nationalist movement for self-determination has been Lëvizja Vetëvendosje! the strongest party.

With pension payments that resemble a clientele system , the former UÇK leadership still dominated politics and society in 2018. The annual expenditure for veterans and veterans associations tripled from 2015 to 2018 for the allegedly 40,000 war veterans, roughly double the number of pensions compared to the estimated number of the KLA at the height of its number in 1999.

Human rights

According to a survey carried out by the UNDP (United Nations Development Program) among the inhabitants of Kosovo in the second half of 2005, the individual ethnic groups identified the greatest current problem in each case (figures in percent of the ethnic group):

- Albanians: unemployment (33.8%), uncertainty about the future status of Kosovo (28.3%), poverty (19.4%), corruption (4.8%), the fate of the missing (4.3%) , Power supply (3.6%), prices (1.2%) unsolved murders (1.0%).

- Serbs: Public and personal security (30.7%), poverty (15.3%), inter-ethnic relations (12.9%), unemployment (12.4%), uncertainty about the future status of Kosovo (9, 9%), organized crime (6.4%), the fate of the missing (3.0%), electricity supply (1.5%).

- Other minorities: unemployment (43.5%), uncertainty about the future status of Kosovo (20.4%), poverty (17.6%), electricity supply (9.3%), prices (2.8%), relationships inter-ethnic group (2.8%), corruption (1.9%), social problems and health care (0.9% each).

In 2007 Amnesty International accused the government of failing to protect minorities and of failing to prosecute war crimes committed against Serbs . Because of the long-standing links between political extremism and organized crime, there are close ties between parts of the KLA-emerged political establishment and criminal structures.

On the festival of the breaking of the fast , on August 29, 2011, the members of parliament voted with a large majority against the introduction of religious education and for a ban on the wearing of headscarves by pupils and teachers in elementary and secondary schools. In doing so, they decided against a joint submission by the parties Alliance New Kosovo , Independent Liberal Party and 6 Plus . The Islamic community of Kosovo sharply criticized the Parliament's actions and described it as illegal and “stabbed in the back” - referring to the time of the vote on the evening of the Muslim breaking of the fast. Islamic scholars also criticized the fact that the ban was contrary to the constitution of the Republic of Kosovo , since religious freedom was guaranteed in the Basic Law . Education Minister Enver Hoxhaj argued that Kosovo is a secular state from the constitutional point of view and that the state must be separated from religion. The reason for this decision were differences between various court instances on the case of a young Kosovar woman from 2010 who was no longer admitted to her school because of her headscarf. The security officers had received an order from the school principal not to allow any more people wearing headscarves to enter the building. The Neue Zürcher Zeitung reported on the controversial case on July 8, 2010. After the fall of the young Kosovar, more similar ones became known and in mid-June around 5,000 people took to the streets to protest against the ban.

Status under international law

After the end of the Kosovo war, the area came under the administration of the United Nations (UN). It remained formally an integral part of the successor state of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and later of Serbia and Montenegro , which existed until 2006. After Montenegro declared itself independent from this state union, Kosovo remained a part of the Republic of Serbia .

Since the declaration of independence on February 17, 2008, Kosovo has been a sovereign state from the perspective of its institutions , and since September 10, 2012 also from an international perspective . To date, 114 of the 193 UN member states have recognized the country's independence . Other states consider the unilaterally proclaimed independence to be illegal and continue to view Kosovo as part of Serbia, even if the Serbian government no longer exercises control over the area.

According to the Ahtisaari plan, which Serbia rejected, independence should be monitored internationally. In February 2008 the European Union decided to send the EULEX Kosovo mission to support the development of the rule of law . It is planned that around 1,800 police officers and lawyers will take on essential tasks in the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo ( UNMIK ). EULEX officially started work on December 9, 2008. The basis for this was a compromise which the United Nations, the EU and Serbia agreed to. Accordingly, the activities of EULEX will take place in a status-neutral framework - which in turn is not recognized by the government of Kosovo.

Four months after the declaration of independence, the new constitution of Kosovo came into force on June 15, 2008 . A week earlier, the parliament in Pristina passed a new national anthem and the establishment of a 2500-strong security group ( Albanian Forca e Sigurisë së Kosovës ). The new constitution defines the country as a democratically governed, secular "state of all its citizens" , which respects the rights of its minorities and international human rights. In the new constitution, the equality of ethnic groups and the importance of the protection of minorities are particularly emphasized. Autonomous rights are granted to the Serbian-dominated regions.

Political work has so far been shared between the UN administration and the “institutions of provisional self-administration” it founded. Security is guaranteed by the peacekeeping force "Kosovo Force" ( KFOR ) under the leadership of NATO, legitimized by a UN mandate . In addition, there are administrative structures (schools, courts, authorities) financed and controlled by Serbia in the Serbian enclaves , especially in northern Kosovo. These are tolerated by UNMIK (and thus also by EULEX), but not recognized; conversely, the Serbian administrations only partially recognize the decisions of UNMIK.

On October 8, 2008, the General Assembly of the United Nations commissioned the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to prepare a legal opinion on the validity of Kosovo's declaration of independence. The UN General Assembly thus followed a request from Serbia. 21 states that have recognized Kosovo and 14 states that speak out against independence submitted statements to the ICJ. The IGH's opinion was published on July 22, 2010. Accordingly, the declaration of independence did not violate international law.

On February 24, 2012, Serbia and Kosovo reached an agreement on the future appearance of Kosovo in international negotiations and on the joint management of their border. The agreement stipulates that Kosovo can in future appear at all regional conferences under the name “Kosovo” and conclude agreements itself (the UN representation in Kosovo was previously responsible for this). The name Kosovo is provided with an asterisk, which refers to a footnote: accordingly, no recognition of independence is associated with this name. Reference is also made to the UN Security Council resolution of 1999, in which Kosovo is recognized as part of Serbia.

External relations

Foreign relations have so far been overshadowed by the dispute over diplomatic recognition. A number of countries, including Germany, Austria and Switzerland, have opened embassies in Pristina since February 2008 . The neighboring countries Albania , Montenegro and North Macedonia have established diplomatic relations with Kosovo.

So far, 22 of the 27 member states of the European Union have recognized Kosovo as an independent state. Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Romania and Slovakia do not recognize Kosovo. The European Commission classifies Kosovo - with reference to UN Resolution 1244, which leaves the final status under international law open - as a potential candidate for EU membership .

An important ally is the US , which maintains a major military base, Camp Bondsteel , as part of KFOR . Russia, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, has sided with Serbia, and China continues to be hostile. For this reason, Kosovo's path to the United Nations and many other international organizations will remain blocked for the time being. One exception is the International Monetary Fund , which offered Kosovo membership on May 8, 2009.

On October 17, 2009, the parliaments of Macedonia and Kosovo ratified an interstate treaty establishing a common national border. For the first time, the border between the two neighboring countries will be made internationally binding.

In March 2011, representatives of Kosovo and Serbia started direct talks for the first time since February 2008 in order to resolve technical and official issues. The representative of Kosovo, Edita Tahiri (Deputy Prime Minister), and the representative of Serbia, Borko Stefanović (Deputy Foreign Minister), met several times with their delegations under EU mediation in Brussels . An initial agreement concerned the area of civil status registers. According to this, Serbia will issue copies of its civil register regarding births, deaths and marriages to Kosovo. In the run-up to the granting of the EU accession candidate status sought by Serbia , both sides agreed in February 2012 on regulations for the administration of the common border and for the freedom of citizens to travel. There was also an agreement on the appearance of Kosovo at international conferences, which Serbia had boycotted until then. Thereafter, the country appears externally under the name Kosovo with a footnote according to which on the one hand the use of the name Kosovo does not mean a statement about the legal status of Kosovo, but on the other hand it is based on the judgment of the International Court of Justice in which its declaration of independence was recognized as legal in 2010 , indicates.

Mutual import bans have existed between Kosovo and Serbia since independence in 2008 , but these were lifted by both sides in September 2011.

Administrative division

The Republic of Kosovo has one level of administrative organization . It is divided into 38 municipalities ( Albanian komuna , Serbian opštine општине ), which include cities and villages with their surroundings. According to the law of February 20, 2008 approved by Parliament and the decree of June 15, 2008 issued by the President, the state is divided into the following municipalities:

| Name of the parish | Official seat | Residents municipality | Urban population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deçan | Deçan | 40,019 | 3,803 |

| Dragash | Dragash | 33,917 | 1,098 |

| Drenas | Drenas | 58,531 | 6.143 |

| Ferizaj | Ferizaj | 108,610 | 42,628 |

| Fushë Kosova | Fushë Kosova | 34,827 | 18,515 |

| Gjakova | Gjakova | 94,556 | 40,827 |

| Gjilan | Gjilan | 90.178 | 54,239 |

| Gračanica | Gračanica | 10,675 | 0 |

| Han i Elezit | Han i Elezit | 9,403 | 0 |

| Istog | Istog | 39,289 | 5.115 |

| Junik | Junik | 6,084 | 0 |

| Kaçanik | Kaçanik | 33,409 | 10,393 |

| Kamenica | Kamenica | 36,085 | 7,331 |

| Klina | Klina | 38,496 | 5,908 |

| Loo | Loo | 2,556 | 0 |

| Leposavić | Leposavić | not specified | not specified |

| Lipjan | Lipjan | 57,605 | 6,870 |

| Malisheva | Malisheva | 54,613 | 3,395 |

| Mamusha | Mamusha | 5,507 | 0 |

| Mitrovica e Jugut | Mitrovica e Jugut | 71,909 | 46.132 |

| Novo Brdo | Bostan | 6,729 | 0 |

| Obiliq | Obiliq | 21,549 | 6,864 |

| Parteš | Parteš | 1,787 | 0 |

| Peja | Peja | 96,450 | 48,962 |

| Podujeva | Podujeva | 88,499 | 23,453 |

| Pristina | Pristina | 198,897 | 161,751 |

| Prizren | Prizren | 177.781 | 94,517 |

| Rahovec | Rahovec | 56.208 | 15,892 |

| Ranilug | Ranilug | 3,866 | 0 |

| Severna Kosovska Mitrovica | Severna Kosovska Mitrovica | not specified | not specified |

| Shtime | Shtime | 27,324 | 7,255 |

| Skënderaj | Skënderaj | 50,858 | 6,612 |

| Štrpce | Štrpce | 6,949 | 1,265 |

| Suhareka | Suhareka | 59,722 | 10,422 |

| Vitia | Vitia | 46,987 | 4,924 |

| Vushtrria | Vushtrria | 69,870 | 27,272 |

| Zubin Potok | Zubin Potok | not specified | not specified |

| Zvečan | Zvečan | not specified | not specified |

Northern Kosovo

Northern Kosovo, largely inhabited by Serbs, is de facto beyond the control of the institutions in Pristina, as many residents do not recognize Kosovo's independence. On June 28, 2008, Serbian politicians in Kosovo established a parliament of the Community of Municipalities of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija, which was independent of Pristina .

Biggest cities

According to the last census from June 2011, the ten largest cities in Kosovo are:

| rank | Albanian | Serbian-Latin | Serbian-Cyrillic | Urban population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Prishtina | Pristina | Приштина | 161,751 |

| 2. | Prizren | Prizren | Призрен | 94,517 |

| 3. | Gjilan | Gnjilane | Гњилане | 54,239 |

| 4th | Peja | Peć | Пећ | 48,962 |

| 5. | Mitrovica | Kosovska Mitrovica | Косовска Митровица | 46.132 |

| 6th | Ferizaj | Uroševac | Урошевац | 42,628 |

| 7th | Gjakova | Đakovica | Ђаковица | 40,827 |

| 8th. | Vushtrria | Vučitrn | Вучитрн | 27,272 |

| 9. | Podujeva | Podujevo | Подујево | 23,453 |

| 10. | Fushë Kosova | Kosovo Polje | Косово Поље | 18,515 |

safety

The United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK)

The Afghan Zahir Tanin has been Head of UNMIK and Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General since 2015 .

UNMIK consisted of four pillars, which were formed by different international organizations: Police and Justice (UN), Self-Government (UN), Democratization and Reconstruction of Institutions ( OSCE ) and Reconstruction and Economic Development ( EU ). The “pillar” supported by the EU was closed on June 30, 2008.

Important functions are formally reserved for the head of UNMIK: approval of the budget (created and managed by the local self-government), law and order (international UN police and local Kosovo police), appointment of judges, protection of ethnic minorities, external relations such as graduation of contracts with other states or international organizations, management of public property, customs and monetary policy.

In fact, in the course of the ongoing reconfiguration, UNMIK transferred important functions to the authorities in Kosovo, which was justified by the changed situation in the country. Police tasks and the organization of elections were given in particular. Most of the UNMIK employees also left the country by the end of 2008. According to the UN Secretary General, although the mission is nominally ongoing, there are only limited working contacts between UNMIK and the Kosovar authorities. A UNMIK spokesman stated in June 2009 that after transferring most of the remaining functions to the EU Rule of Law Mission (EULEX), UNMIK would concentrate on the political task of “establishing dialogue between the communities”.

military

On January 21, 2009, the Kosovo Security Forces ( Forca e Sigurisë së Kosovës , FSK) were founded. They have a strength of 2500 active soldiers and 800 reservists. With the contemporaneous dissolution of the Kosovo Protection Corps , the Kosovo government fulfilled an obligation under the plan of UN - negotiator Martti Ahtisaari , the basis of the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo.

Around 4030 soldiers from the NATO military mission KFOR are also deployed in Kosovo .

Organized crime

According to the US State Department , Kosovo and the neighboring regions are one of the most important European drug transit routes for heroin from Afghanistan to Western Europe . In Kosovo there is a regional center for drug smuggling on the Balkan Peninsula. Even when the KLA was set up in the 1990s, a connection between funding from the drug milieu was at the fore. In particular, drug trafficking increased sharply in the uncontrollable situation after the Kosovo war. According to Interpol, up to 40% of the heroin sold in Europe came from Kosovo after the war. According to the Carla Del Pontes report, the need to curb the extent of drug trafficking in Kosovo was recognized as a main problem area for the European Commission in further European Kosovo policy, which also plays an important role in the Eulex mission . Nevertheless, Eulex, which is responsible for border controls, was unable to carry out effective customs surveillance of the administrative border with the means available at the moment, which is due, among other things, to the lack of law in individual parts of the country and the inaction of the local judiciary.

Due to the weakness of the judicial authorities, extensive organized crime cannot be contained. According to UNMIK, drug trafficking made up 15–20% of the country's total economic output in 2008. The actual economic turnover of organized crime corresponds to over a quarter of the gross national product , which is artificially high due to enormous international money shifts , which amounts to around 1.5 million euros per day (550 million euros per year). In particular, the prime minister of the country, Ramush Haradinaj, was accused of a connection to drug trafficking, which contributes to the social insecurity of the Kosovar population in the post-war society in Kosovo , which is divided into clans and in the hostile groups in power struggles, some of which are now included in mafia-like structures.

Since the governing members of the government are generally close to organized crime, mafia-like structures form the basis of the leadership areas in the political landscape. According to the Federal Intelligence Service (BND), the top Kosovar politicians Thaçi, Halili and Haradinaj operate closely interwoven networks of organized crime that penetrate politics and the economy deeply. An anti-corruption law to combat money laundering was only passed under pressure from the EU. As a result of the social transformation processes and the political reorganization since the Kosovo war, as well as the tolerance of power structures by the international community, a “gangster culture” that holds the rest of society hostage has been able to establish itself .

The events in the so-called BND affair , as a result of which a high-ranking BND employee spoke of Kosovo as a country in which "organized crime is the form of government [...]", also indicated the connection between organized crime and state structures . Through this establishment of organized crime in the political environment in Kosovo, which in the areas of drug smuggling, human trafficking and money laundering are leading actors of mafia organizations in Europe - up to 80 percent of the heroin smuggled into Western Europe now comes from Kosovo - this group is one serious threat to the EU. A confidential study on security issues in the Western Balkans carried out by the Berlin Institute for European Politics on behalf of the German Defense Ministry criticized the methods of the Americans, which in individual cases placed high-ranking criminals under protection, as well as the investigative efforts of European judicial bodies, counterproductive to European efforts.

According to older information from UNMIK, organized criminal Albanian groups also operated 104 brothels in Kosovo, in which forced prostitution, trafficking in women, money laundering and human smuggling pose problems of organized crime and its interdependence with international organizations on site.

Also, in a report by the Council of Europe from the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011, serious allegations of organ harvesting in Kosovo in connection with human trafficking, murder and other serious crimes for the period from 1999 to 2000, in which leading politicians such as Hashim Thaçi are and are involved which should not have been punished by the international community. While these allegations have been under review by EULEX Kosovo since 2011, a court judgment was passed in 2008 for organ trafficking in the Medicus Clinic in Pristina, which found several defendants guilty.

At the beginning of 2013 the Council of Europe called on the authorities of Kosovo as well as the EU and UN missions for the country, EULEX and UNMIK, to finally put a stop to the “culture of impunity, often promoted by members of the government”. The European Court of Auditors last criticized the work of EULEX as “not efficient enough” in mid-2012 and found that the EU's measures to combat corruption and organized crime in Kosovo had so far not had much success.

economy

development

Kosovo was the poorest region within Yugoslavia. The reason for this was - in addition to the general backwardness of the region - also a failed economic and structural policy of the Tito era: in Kosovo predominantly raw material producing and little processing industry was settled. Although Kosovo was subsidized by other Yugoslav republics, investment in the 1960s and 1970s was around 50% of the Yugoslav average. In addition, a large part of the subsidies went to the non-productive area. The gross national product per capita fell from 44% of the Yugoslav average in 1952 to 27% in 1988.

In 1989 the average monthly income in Kosovo was 454 dinars (Slovenia: 1180; Croatia: 823; central Serbia: 784). In the early 1990s, Kosovo's economic productivity was halved again. The reasons were the collapse of the former economic area of Yugoslavia in the wake of civil wars, international sanctions and a lack of access to foreign markets and finances. As a result of the Serbian-Albanian conflict, there was another 20% decrease in 1998/99 - at an already very low level.

After the war in Kosovo, around two billion euros in aid were made available. So far, 50,000 houses, 1,400 kilometers of roads, hospitals and schools have been rebuilt or built. This led to a short-term post-war upswing in the construction, trade and public administration sectors. At an international donor conference in Brussels in July 2008, the participating countries and organizations pledged further aid to Kosovo totaling 1.2 billion euros by 2011. About 500 million euros of this should come from the European Union, the United States want to contribute around 400 million dollars. The allocation of the funds was linked to far-reaching conditions for their use, for example also for the Serbian minority.

structure

| Inflation rate (as of 2009) | |

|---|---|

| year | rate |

| August 2009 | −3% |

| 2008 | 9.4% |

| 2007 | 4.3% |

| 2005 | −0.5% |

| 2004 | 1.5% |

| 2003 | 1.1% |

| 2002 | 3.6% |

The economy is based on the one hand on small-scale family businesses as well as private companies in the trade and construction sector, which were mostly founded after the war and are partly funded by EU funds, but are often undercapitalized. Financial transfers from abroad have decreased significantly since 2003. In addition, in 2005 there were 18 agricultural combines, 124 state-owned companies and 150 cooperative companies . These companies are in social property ( "socially owned") , a special form of property in Yugoslav self-management socialism , unfamiliar with the state property in the other socialist identical countries. These operations have been managed by the Kosovo Treuhandanstalt (KTA / AKM), which is subordinate to UNMIK , since 2002 .

The gross value added per capita at the lowest point of economic development was 508 US dollars in 2000 and 2424 US dollars in 2012. The growth rates are high in a regional comparison, but fluctuate very strongly. Months of government formation, problems with the electricity supply, declining public and foreign investments and the increasing trade deficit led to a noticeable decline in growth to around 2.5 percent in 2014. The gross domestic product in 2012 was 1.814 billion US dollars.

Foreign trade

Kosovo's foreign trade has been permanently in deficit since 1990. Currently three times as much is imported as it is exported. In 2012 exports of 1.2 billion US dollars were compared with imports of 3.6 billion. Iron, steel, ores and textiles are exported, fuels, mineral oil products, synthetic yarns, motor vehicles (used cars with diesel engines) and machines are imported. The main customer countries are Italy, Albania, North Macedonia and China, the main importers are Serbia, Germany and Turkey.

Industry

The industrial sector is characterized by the areas of mining , chemistry , electronics, textiles, building materials and wood . In mining ( natural resources of Kosovo ) ore , coal , lead and zinc are extracted. Overall, the industrial sector is rather weak. The industrial sector accounts for 22.6% of GDP.

Agriculture

Are cultivated cereals ( wheat , corn ), sunflower , berries , rapeseed , sugar beet and grapes. Although a large part of the population works in this sector, it generates only 12.9% of the total gross domestic product.

Ancient breeds of domestic animals

Among the ancient breeds of domestic animals in Kosovo, the best known is the Kosovo crows , which have enjoyed increasing popularity in recent years outside of the country of origin because of their extraordinary crow call .

Services

With a share of 64.5% of the gross domestic product (2009), it is the largest sector in the economy.

currency

The official currency is the euro . However, Kosovo is not a member of the European Monetary Union . The D-Mark , which was previously established as a second currency, was introduced as a currency by the UN administration in 1999 and was later replaced by the euro. Serbian dinars can also be used to pay in Serbian enclaves .

Problems

Foreign trade deficit

The chronic foreign trade deficit is increasing and amounted to 2.4 billion US dollars in 2012, or almost 45 percent of the gross domestic product. Relatively low quality products are exported.

Dependence on foreign capital inflows

The economy is extremely dependent on external financial inflows (aid funds, capital transfers from emigrants). According to the Kosovo Ministry of Finance, remittances by guest workers from abroad are higher than the values generated in Kosovo. Since aid funds are declining and access to the EU labor market is also made more difficult for Kosovars, this already unhealthy structure harbors considerable risks. In view of the uncertain political future and problematic legislation on privatization, foreign direct investment is still negligible.

unemployment

Every year another 36,000 young people come onto the job market; even in 20 years' time it will still be around 30,000 per year due to today's birth rate.

Unemployment had fallen slightly for a while from a high level (2001: 57.1%, 2002: 55%, 2003: 49.7%). In 2008, unemployment ranged from 42 to 43%. The age group between 16 and 24 years is affected to 60%. It rose again after the financial crisis. The USAID states the unemployment rate in 2014 as 45% and youth unemployment as 70%. At the end of 2014, around 280,000 people were unemployed. According to the Statistics Institute of Kosovo (ASK), unemployment was 27.5% in 2016. This affected 32.2% women and 26% men. The Kosovar state broadcaster RTK reported in July 2017 that unemployment had risen to 30.5% again. The figures for youth unemployment (young people under the age of 25) remained at 52.7% in the last quarter of 2017. According to the Swiss Embassy in Kosovo, 70% of those who have a job only have a fixed-term contract. Ethnic minorities, especially the Roma, Ashkali or Egyptians, as well as women in general and young people without family ties to companies or administrations, find it particularly difficult to get onto the labor market.

| year | Unemployment in percent |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 57.1% |

| 2002 | 55% |

| 2003 | 49.7% |

| 2008 | 42.5% |

| 2014 | 45% |

| 2016 | 27.5% |

| 2017 | 30.5% |

| 2018 | 33.5% |

In the past, attempts have been made to resolve the coincidence of chronic underemployment and very rapid population growth through labor migration, especially to Switzerland and Germany. Unregulated migration to Germany, Austria etc. has accelerated since autumn 2014. It is not foreseeable that economic growth and direct investment from abroad will be sufficient to solve the problems of employment and poverty.

Effects of the international intervention

The international community has invested around four billion euros between the end of the war in 1999 and 2011, but there is hardly any industry, and even agricultural products are imported from China. Mismanagement, corruption and over-regulation on the part of the EU and the USA are seen as causes. A tax administration is only being set up. In January 2012 z. B. collected a whopping $ 1.2 million in taxes. That corresponds to around 14 million US dollars per year, or about 78 US dollars per inhabitant - including corporate taxes. The World Bank and other institutions have improved ratings of the start-up and business climate in recent years, primarily referring to the possibility of international investors to register export-import companies from abroad quickly and unbureaucratically. Local startups suffer from low growth potential and corruption.

Social inequality

According to the World Bank from 2009, 34% of the population live below the poverty line (income below 1.37 euros per day and adult) and 12% even below the extreme poverty line (income below 0.93 euros per day and adult).

The elderly, the disabled, residents of small or remote towns and communities, and members of non-Serb minorities such as Roma or Gorans are particularly affected. Poverty in Kosovo also affects other areas: upbringing and education are underfunded, and schools are taught in three to four shifts. The residents' health records are among the worst in Southeastern Europe.

Perspectives

The World Bank experts see economic future opportunities in the areas of energy and mining. Natural resources ( natural resources of Kosovo ) include lignite, lead, zinc, nickel, uranium, silver, gold, copper or magnesite. The World Bank also regards agriculture as a possible growth sector.

The EU experts recommend a structural reform of agriculture with significant increases in productivity and the establishment of a domestic industry, initially in the food, clothing, furniture and simple mechanical engineering sectors . A lot of growth potential is also seen in tourism in Kosovo .

The main obstacles are poor infrastructure, a lack of appropriately trained specialists, an uncertain overall political situation, inadequate or no economic reforms on the part of local self-government.

Infrastructure

energy

The electricity supply is poor and irregular, which is a major obstacle to economic development. The whole of Kosovo is supplied with electricity by the two coal-fired power plants Kosova A and B in Obiliq as well as by a thermal power plant and a smaller hydropower plant. The construction of a new power plant block ( Kosova e Re ) and the development of further coal deposits are planned.

As of February 2006, the Kosovo electricity works (Alban. Korporata Energjetike e Kosovës , KEK) divided the country into three reliability categories , which depend on the customer's payment behavior . Regions in which the payment behavior of electricity customers is high (category A) receive electricity all day. Regions with mediocre payment behavior receive electricity for five hours each (category B), followed by a one-hour break. Regions with the lowest payment behavior (category C) do not receive an electricity supply guarantee, but the aim is to maintain the supply at the rhythm of "two hours switched on, four hours switched off". In 2007 KEK suffered a loss of 99 million euros due to theft and unpaid electricity bills.

In the very cold January 2006 there were sensitive bottlenecks - the peak demand was 1,300 megawatts , with in-house production of 580 MW. It was not possible to close the gap through imports. For this reason, category A was temporarily supplied at a rate of 4: 2 (four hours on, two hours off), category B at a rate of 3: 3 and category C at a rate of 2: 4.

To the west of Prizren, the construction of the Zhur hydropower plant should begin in 2011 , which will be the largest in the country, have a capacity of 305 MW and produce 400 gigawatt hours of electricity per year . The water for this would be supplied via pressure pipes from reservoirs to be built in the Dragash region . However, in 2012 the project was finally abandoned. On the one hand, no investor was found for the 500 million euro project and, on the other hand, the power plant could only have produced electricity for 30 days a year, as it would only have run through reservoirs fed during the year.

traffic

railroad

The history of the railway in Kosovo began with the line from Selanik via Üsküb to Kosova Ovası , which was opened in 1874 , built and operated by the Compagnie des Chemins de Fer Orientaux (CO) , headed by Baron Hirsch . The rail network, which is used for passenger transport and which has not yet been significantly expanded or electrified, is only 333 kilometers long, but after the war in 1999 it was no longer fully used and in terms of rail infrastructure as well as vehicles are in extremely poor condition. Of the 97 kilometers of railways that can only be used industrially, it is currently not known to what extent these are served.

The lack of major investments in the Kosovar rail network, which has been neglected for decades and which is also not integrated into the Pan-European Corridor X, has so far not allowed any revival of rail traffic in the Kosovo transport route system. However , a loan of almost 40 million euros granted by the European Development Bank in September 2015 is intended to be used to modernize the 148-kilometer main line from the North Macedonian border via Fushë Kosova and Mitrovica to the Serbian border. The construction work for this began in the southern section between the border with Macedonia and Fushë Kosova at the beginning of June 2019.

The railway company Trainkos currently operates the two routes Peja - Pristina and Han i Elezit - Fushë Kosova with an international connection to Skopje.

At the beginning of March 2008, the Serbian railway company Železnice Srbije took over operations in northern Kosovo, which is primarily inhabited by Serbs .

Until 1993, the Fushë Kosova station was the stopping point of the Akropolis-Express from Munich to Athens , which was completely closed with the beginning of the Yugoslav war.

Streets

Several national roads and two motorways run through Kosovo. There are currently around 630 kilometers of main and country roads. The main traffic axes are easy to drive. Some places can only be reached on dirt roads or gravel roads.

The international green card is not recognized in Kosovo. Foreigners must therefore purchase a Kosovar insurance card at the border. A 15-day insurance for 15 euros can be taken out for transit. The vehicle can also be insured for one, two, six or twelve months.

There are currently five motorway routes in Kosovo, two of which have been completed:

- Autostrada R 6 - Autostrada Arbën Xhaferi

The R 6 is supposed to connect the Kosovar capital Pristina with the North Macedonian capital. The total length should be 60 kilometers, of which the first 20 kilometers to the village of Babush i Muhaxherëve were put into operation on December 31, 2016 . On December 22nd, 2017, the second phase of the eleven-kilometer route to Bibaj near Ferizaj was opened to traffic. The third section to Doganaj took place in summer 2018. At the end of 2018, the Autostrada should lead completely to Han i Elezit .

The Autostrada R 6b is a 32-kilometer-long planned motorway that is due to go into construction in 2018. It connects the village of Zahaq near Peja with the village of Kijeva near Pristina and is intended to significantly shorten the distance between the two cities.

-

Autostrada R 7 - Autostrada Ibrahim Rugova

The first Kosovar motorway currently exists as a connection to the Albanian A1 and connection to central Albania. The US consortium Bechtel-Enka was awarded the contract for the major project . Because of the excessive prices of this company, paid by the state of Kosovo, there is criticism from the opposition, especially the party VV ( Vetevendosje! - "Self-determination"). The European Union's rule of law mission in Kosovo has now started an investigation into the award of the contract.

An extension of the motorway to the Pan-European Transport Corridor X near Niš in Serbia is in the preliminary planning phase. The section between Truda and the Merdare border crossing is currently under construction.

-

Autostrada R 7.1 - Autostrada Prishtinë-Gjilan-Dheu i Bardhë

The R 7.1 is supposed to connect Pristina to the village of Dheu i Bardhë via Gjilan. The planning of the motorway has already been completed.

Air traffic

There is a civil airport and a military airfield in Kosovo . The Pristina International Airport Adem Jashari made from 2012 1.5 million passengers; two years earlier there were 5,777 flights to and from Pristina. Numerous European airlines fly to Pristina, including flights from German-speaking countries from Berlin , Düsseldorf , Frankfurt am Main , Hamburg , Hanover , Cologne / Bonn , Memmingen , Munich , Stuttgart , Vienna and Zurich .

Maritime transport and shipping

On February 20, 2009, the Republic of Kosovo asked neighboring Albania to use the Shëngjin port on the Adriatic coast . Unofficially, this port has been reserved for the Kosovars for more than a decade. There are also ideas to build a railway line between the port and Kosovo. As a result, both neighboring countries expect an economic upturn. Furthermore, the Kosovar government wants to set up a customs branch in this port and begin using it soon.

telecommunications

On December 15, 2016, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) officially assigned +383 to Kosovo as the international country code. According to an agreement within the framework of the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue brokered by the EU, the telephone area code was last requested by Serbia at the beginning of December 2016, based on the previous telecommunications agreement of 2015 and the reservation of this area code. Years of negotiations preceded the agreement. After all technical implementations have been carried out, the new area code +383 has been active since February 2, 2017. Until this changeover, the landline connections in Kosovo could still be reached using the country code for Serbia (+381).

The following telecommunications providers are active in Kosovo:

- Telekomi i Kosovës (landline and internet)

- PTK Vala (cellular)

- IPKO (landline, cellular, internet)

For over 1.2 million cell phone connections (PTK Vala) in the Republic of Kosovo, the phone number range issued by Monaco at +3774 is used. This belongs to Monaco Telecom , which also operates the network.

Culture

Symbols

Since the declaration of independence in February 2008, the institutions have been using the new flag of Kosovo . Many Kosovar Albanians use the flag of Albania while most Serbs prefer the flag of Serbia . The United Nations flag was used on official occasions until independence .

On June 5, 2008, the chairman of the constitutional commission of the Kosovar parliament, Hajredin Kuçi, announced that the working group to find the future national anthem had agreed on the composition Evropa ("Europe") by Mendi Mengjiqi . The national anthem came into force with the adoption of the constitution on June 15, 2008 and has thus replaced the previously provisionally used European anthem . It has no text in the official version.

public holidays

Public holidays with a fixed date are:

- New Year's Day on January 1st (Albanian Viti i ri )

- Ashkali Day on February 15th

- Declaration of Independence on February 17th (Dita e Pavarësisë)

- Veterans Day on March 6th

- Roma Day on April 8th

- Day of the Turks on April 23rd

- Labor Day on May 1st (Dita e Punës)

- Day of the Gorans on May 6th

- Europe Day on May 9th (Dita e Evropës)

- Day of Peace on June 12th

- Constitution Day on June 15 (Dita e Kushtetutës)

- Bosniak Day on September 28th