Slovakia

| Slovenská republika | |||||

| Slovak Republic | |||||

|

|||||

| Official language | Slovak | ||||

| Capital | Bratislava | ||||

| Form of government | Parliamentary republic | ||||

| Government system | Parliamentary democracy | ||||

| Head of state |

President Zuzana Čaputová |

||||

| Head of government |

Prime Minister Igor Matovič |

||||

| surface | 49,034 km² | ||||

| population | 5,457,873 (December 31, 2019) | ||||

| Population density | 111 inhabitants per km² | ||||

| Population development | + 0.01% per year | ||||

gross domestic product

|

2018 | ||||

| Human Development Index | 0.857 ( 36th ) (2018) | ||||

| currency | Euro (EUR) | ||||

| founding | January 1, 1993 | ||||

| National anthem | Nad Tatrou sa blýska | ||||

| Time zone |

UTC + 1 CET UTC + 2 CEST (March to October) |

||||

| License Plate | SK | ||||

| ISO 3166 | SK , SVK, 703 | ||||

| Internet TLD | .sk | ||||

| Telephone code | +421 | ||||

The Slovakia (Slovak Slovensko , officially Slovak Republic , Slovak Slovenská republika ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe , which in Austria , Czech Republic , Poland , the Ukraine and Hungary borders. The capital and largest city of the country is Bratislava ( Pressburg in German ), other important cities are Košice ( Kaschau ), Prešov ( Eperies ), Žilina ( Sillein ), Banská Bystrica ( Neusohl ) and Nitra ( Neutra ).

Two thirds of the country is mountainous and has a considerable share of the Carpathian Arc . In the west it extends to the part of the Vienna Basin to the north of the Danube , while the south and southeast to the Danube and a small part of the Tisza are shaped by the foothills of the Pannonian Plain . Slovakia lies in the continental temperate climate zone with differences between the lower south and the mountainous north of the country.

The area of today's Slovakia was settled by the Slavs at the turning point of the 5th and 6th centuries . Their first political formation was the empire of Samo (7th century), later one of the centers of the early medieval Moravian empire was in Slovakia . In the 11th century Slovakia was incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary , which was part of the Habsburg Monarchy from 1526 and part of Austria-Hungary from 1867 . After the dissolution of the dual monarchy in 1918, Slovakia became part of the newly established Czechoslovakia , except during the period from 1939 to 1945 when the Slovak state existed. After the end of the Second World War , the Czechoslovak state was restored. On January 1, 1993, after the peaceful division of this state structure, the independent Slovak Republic was established as the national state of the Slovaks .

Slovakia has been a member of the European Union and NATO since 2004 . In 2007, border controls with EU countries were lifted in accordance with the Schengen Agreement , and Slovakia joined the euro zone in 2009 . The country is a democratically constituted parliamentary republic. Together with Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary, Slovakia forms the Visegrád Group .

In the ranking according to the human development index , Slovakia was ranked 36th out of 189 countries evaluated in 2018 with a value of 0.857 and is thus in the group with “very high human development”.

State name and ethnonym

History

The current German name of the area and state, Slovakia , is relatively new and appears for the first time in a petition to the Austrian emperor in 1849. The Slovak national name Slovensko has been documented in writing since the 15th century and was derived from the Old Slavic self-name of all Slavs, the Sloveni , which appeared in the 9th century . In the 14th century, the area of today's western and central Slovakia was often referred to as " Mattesland " (Slovak: Matúšová zem ), after the powerful Magyar prince Mattäus Csák . Since the 16th century, the term Upper Hungary (Slovak: Horné Uhorsko ) has been increasingly used for the area of today's Slovakia , after most of Hungary was under Turkish rule except for today's Slovakia.

Similarities between the state names of Slovakia and Slovenia

The current self-designation of the West Slavic Slovaks , like that of the South Slavic Slovenes, is derived from the original name of all Slavs, the Sloveni . Thus, the Slovaks refer to their country as Sloven sko, while Slovenia among Slovenians Sloven is ija. The Slovak language is in Slovak as sloven Cina, the Slovenian language in Slovenian as sloven referred Scina. The word for Slovak (in Slovak) and Slovenian (in Slovenian) is the same in both languages: Sloven ka. The only major difference today is the male form: While the Slovenian original male form Sloven ec has been preserved to this day, the Slovaks in the 15th century (under Czech and Polish influence) underwent a transformation in which the original Male name Sloven was replaced by today's name Slov ák.

geography

Natural space

Slovakia stretches between the 47th and 49th parallel north, between the 17th and 22nd east latitude and has a maximum east-west extension of 429 kilometers (from Záhorská Ves to Nová Sedlica ) and a north-south extension of 197 kilometers (from Obid to Skalité ). In the north and in the middle it has the character of a mountainous country , but in the south it extends into the Great and Small Hungarian Plains . The state has an area of almost a third of the entire Carpathian arch , especially the Western Carpathians . The highest point is the Gerlachovský štít (Gerlsdorferspitze) in the High Tatras with 2655 m nm (also the highest mountain in the entire Carpathian Mountains); the number of two thousand meter peaks is around 100. The lowest point is on the Bodrog River near Streda nad Bodrogom , where the river leaves Slovakia at 94 m nm . The geographical center of Slovakia is on the Hrb mountain near Ľubietová , one of the claimed centers of Europe is located near Kremnické Bane . Slovakia has the following border lengths to the neighboring countries: Austria 107 km, Czech Republic 252 km, Poland 541 km, Ukraine 98 km and Hungary 655 km.

Two thirds of the area of Slovakia belong to the Carpathian Mountains , the rest form the foothills of the Pannonian Plain and a small part of the Vienna Basin .

In the west, near Bratislava, the Carpathians begin with the Little Carpathians (height to 770 m), a small mountain range, northeast mind to close the White Carpathians ( Biele Karpaty , to 1000 m), Strážovské vrchy , Javorníky and various mountains in the Beskidy Mountains , which follow the Czech and later the Polish border. East of Žilina the altitude continues to increase, with mountains such as Small and Great Fatra ( Malá / Veľká Fatra , up to 1700 m), the Low Tatras ( Nízke Tatry , up to 2040 m) and the Tatras ( Tatry , highest peaks 2400–2655) m) on the Polish border. In the further course of the Outer Carpathians the altitude drops again, beginning with the Leutschauer Mountains and the Spiš Magura and further over the Lower Beskids to the Ukrainian border (altitude 500–1200 m); near Bardejov lies the border between the Western Carpathians and Eastern Carpathians (in this region also called Forest Carpathians in German ). This is followed by the Ondavská vrchovina mountain range , before the Slovak part of the outer Carpathians ends with the Bukovské vrchy mountains .

Further inland , the elevations begin with the Tribetz and the Vogelgebirge near Nitra and Topoľčany (up to 1340 m). The region to the west and south of Banská Bystrica is covered by various mountain ranges of the Slovak Central Uplands (up to 1300 m), including the Schemnitzer , Kremnitzer Mountains and the Po .ana. The entire area between Detva (east of Zvolen ) and Košice is covered by the Slovak Ore Mountains ( Slovenské rudohorie , up to almost 1500 m), with the altitude generally decreasing from north to south. To the east of Košice there are significant mountains, the Slanské vrchy and the Vihorlat (up to almost 1100 m).

The population in the mountains of the country is concentrated in the many basins; the most important are (from west to east): the Považské podolie , the Hornonitrianska kotlina , the Žilinská kotlina , the Turčianska kotlina , the Zvolenská kotlina , the Podtatranská kotlina , the Juhoslovenská kotlina and the Košická kotlina .

Larger lowlands are mainly in the west and south-east of the country. The Záhorská nížina is located between the March and the Little Carpathians, and it overlaps with the Záhorie landscape . From a geomorphological point of view, it is part of the Vienna Basin. The Danube lowlands (Podunajská nížina) stretches roughly between the Little Carpathians and the Slovak Central Uplands ; due to their size and different landscapes, it extends further into the Danube Plain (Podunajská rovina) in the southwest between Bratislava and Nové Zámky / Komárno and into the Danube Hills (Podunajská) pahorkatina) to the north and east of it. The height varies from 100 m in the south to 200 m in the north. In the area around Trebišov and Michalovce, the east Slovak lowland stretches out , which, like the Danube lowlands , is divided into a flat and hilly part.

geology

Slovakia belongs to the Alpidic mountain system , which arose in the late Mesozoic and Cenozoic . Rocks of Paleozoic and possibly Proterozoic origin also took part in the formation . Until the late Mesozoic, most of what is now Slovakia was below sea level. The core of the later Western Carpathians is formed by metamorphosis , granite , gneiss and mica schist , which are covered by limestone and dolomite rock formed from sedimentary rocks. Towards the end of the Mesozoic and the Cenozoic there were significant changes in the structure of the earth's crust through folding and orogeny. In the Young Tertiary , today's mountains emerged from raised clods , from sunken basins and lowlands, which were formed on molasse basins in the Miocene and Pliocene . Mountain formation continued as the area gradually increased. There was volcanic activity in southern central and eastern Slovakia, from which today's volcanic mountains emerged. At the end of the Neogene , when the last parts of the world's oceans and lakes disappeared from Slovakia, today's river system emerged. The current relief was also formed by glacial activity in the Quaternary and erosion .

The geological structure of Slovakia is diverse. The flysch zone includes the outer western and eastern Carpathians in northern and northeastern Slovakia, which are separated from the inner Carpathians by the Pieninen rock belt . Then there are inner-Carpathian paleogene zones on the inner (southern) side of the rock belt, which include valleys, low mountain ranges and mountainous regions from Žilina to about Prešov, with a foothill to the Humenné area. The core mountains belong to the so-called Fatra-Tatra area , which consist of granite, gneiss and mica slate in the core and lime and dolomites on the ceiling and extend in two zones from the Little Carpathians and Tribeč Mountains to the Tatras and Low Tatras. The volcanic mountains are located south of the core mountains and essentially form the Slovak Central Mountains , the Slanské vrchy and the Vihorlat in the east and the small mountains Burda near Štúrovo are also volcanic mountains . The Slovak Ore Mountains consist of two separate zones, namely the Vepor zone in the west and the Čierna hora mountains in the east and the Gemer zone with other eastern parts of the mountains. Some authors consider the small mountain range Zemplínske vrchy as a separate tectonic unit (see also the map on the right), while others consider it to be volcanic mountains.

Slovakia lies on the Eurasian plate and has several seismically active areas. These include the Komárno area , the Little Carpathians (especially around Dobrá Voda), the area from Trenčín to Žilina, the area of Banská Bystrica, the High Tatras and the Northern Spiš (continued in Podhale in Poland ) and the Zemplín landscape. The strongest recorded earthquakes were in central Slovakia in 1443 and in Dobrá Voda in 1906 ( M w = 5.7) as well as in Žilina in 1613 and in Komárno (M w = 5.6) in 1763 .

Waters

The main European watershed between the Black Sea (Danube) and the Baltic Sea ( Vistula ) runs through the country , with 96% of the country belonging to the catchment area of the Danube. Due to the geographical location, only about 12% of the water volume flows in the rivers that originate in Slovakia. The Danube (Dunaj) in the southwest has a length of 172 km on Slovak territory (including the borders with Austria and Hungary, 22.5 km on both sides). With an average discharge of around 2060 m³ / s (MQ) near Bratislava, it is by far the most water-rich river in Slovakia. The longest Slovak river is the Waag (Váh) with a length of 403 kilometers, which flows through the whole north and west of the country and has a discharge of 142 m³ / s (MQ) at Komoča . Other important rivers are the March (Morava) on the borders with the Czech Republic and Austria, the Gran (Hron) in the middle, the Eipel (Ipeľ) on the border with Hungary, as well as Sajó (Slaná) , Hornád , Laborec , Latorica and Bodrog in the east, while the Tisza (Tisa) affected only the southeast corner of the country. Only the Poprad and the Dunajec (border with Poland) east of the Tatra Mountains belong to the catchment area of the Vistula .

Natural lake areas are concentrated in the High Tatras, where numerous mountain lakes ( plesá in Slovak ) were created as a result of glaciation during the Ice Age ; the largest is the Veľké Hincovo pleso . There are very few natural lakes elsewhere. Reservoirs, which were created in the course of river regulation for energy generation and flood protection, shape the landscape. Most are located on the Waag, whose system is also known as the Waag Cascade (Vážska kaskáda) . These include the dam Liptovská Mara (Liptovská Mara) , Reservoir Nosice , Sĺňava , Reservoir Kráľová and more. The largest is the Orava reservoir (35 km²), followed by the Zemplínska šírava and the Liptov reservoir. The reservoirs of the Danube hydroelectric power station Gabčíkovo are also important . Exceptions are the so-called tajchy around Banská Štiavnica , which were created in the course of mining there.

Slovakia has large groundwater reserves , but these are unevenly distributed across the country. The area of the Große Schüttinsel is important with around 10 billion m³ of groundwater. It has been a water protection area since 1978. Artesian springs are mainly found in the Danube lowlands around Galanta and Nové Zámky, in the Záhorie landscape, in the eastern Slovak lowlands. In the mountains there are groundwater reserves in limestone and dolomite , but they are hardly available in the Flysch mountains . The country is also rich in mineral springs with more than 1,600 known springs. More than 100 of these springs are bottled for mineral water or used for treatment purposes. The most famous spa town is Piešťany, other spas total Slovak importance Trenčianske Teplice , Bardejov Spa , Smrdáky , Rajecké Teplice , Sklené Teplice , Turčianske Teplice , Dudince , Sliač , Kováčová , Nimnica , Korytnica , Lúčky , Číž , Vyšné Ružbachy , Bojnice and Korytnica (except Business).

fauna and Flora

The natural area of Slovakia belongs to the moderate climatic zone .

There are a total of around 34,000 animal species , of which around 30,000 are insects alone . There are 934 types of arachnids , 352 types of birds , 346 types of molluscs , 90 types of mammals , 79 types of fish , 18 types of amphibians, and 12 types of reptiles .

Of the mammals, 24 species are bats : the most famous representatives are the great mouse-eared mouse and the little horseshoe bat . In the middle and high mountains one can still find predators such as wolves and brown bears ; foxes, game, wild cats and wild boars can be found in the deciduous forests, while brown bears, squirrels and lynxes are represented in the coniferous forest . Above the tree line one can find Tatra chamois , marmots and snow mice . Since 2004 there have been wild bison again in Slovakia (17 animals, as of 2013), in the Beskids in the far north-east of the country.

There are around 13,100 plant species in Slovakia, including around 3,000 algae and blue-green algae, 3,700 fungi, 1,500 lichens, 900 mosses and 4,000 vascular plants. According to the last forest inventory (2004–2007), the proportion of forest on the surface is 44.3% of the national area.

The prevailing climate divides the country into several levels of vegetation . Most of the lowlands have been landscaped , with only a few remains of the original forests. Alluvial forest ( willows , poplars ) has declined sharply, the best examples can be found along the Danube. Up to a height of about 550 m (lowlands, lower mountains), oaks and hornbeams are predominantly found, in the Záhorie the Swiss stone pine can also be found. Next up in 1100-1250 m (highlands) up Book and fir , while spruce up to the tree line can be found (1450-1700 m), in the Tatra also comes pineal ago. The Krummholz stage is located above the tree line, while the pure alpine stage is limited to the highest peaks of the Tatra Mountains. Overall, the forests consist of 60% deciduous forest and 40% coniferous forest, the most common beeches (with a share of more than 33%), spruce and oak.

caves

Due to geological conditions, many karst caves and a smaller number of caves of other than karst origin (e.g. andesite , basalt , granite , slate ) have formed in Slovakia . Most of the karst caves were formed in Mesozoic limestones of the Middle Triassic , less in travertines or occasionally less soluble rocks. Including short transition caves, more than 7,100 caves are known in Slovakia and new ones are constantly being discovered. Most of them can be found in the Slovak Karst, the Muránska planina, the Great Fatra and all parts of the Tatra Mountains.

About 20 caves are operated as show caves , 13 of them by the Slovak State Cave Administration ( Slovenská správa jaskýň , abbreviated SSJ). These include five caves that are listed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage “Caves of the Aggtelek and Slovak Karst”: Domica , Jasovská jaskyňa , Gombasecká jaskyňa , Ochtinská aragonitová jaskyňa and Dobšinská ľadová jaskyňa . In the Demänová cave system, the Demänovská jaskyňa Slobody and the Demänovská ľadová jaskyňa are open to the public. The other caves operated by the SSJ are the Belianska jaskyňa , the Brestovská jaskyňa , the Bystrianska jaskyňa , Driny , the Harmanecká jaskyňa and the Važecká jaskyňa . Other show caves outside the SSJ network include Bojnická hradná jaskyňa in Bojnice, Jaskyňa mŕtvych netopierov in the Low Tatras, Krásnohorská jaskyňa in the Slovak Karst and Zlá diera in the Bachureň Mountains.

The three longest caves include the Demänová cave system in the Low Tatras (41 kilometers), Mesačný tieň in the High Tatras (32 kilometers) and Stratenská diera in the Slovak Paradise (22 kilometers). The deepest caves are Hipmanove Jaskyne in the Low Tatras (495 meters), Mesačný tieň (451 meters) and Javorinka (374 meters) in the High Tatras.

climate

Slovakia lies in the continental temperate zone, with the influence of the oceanic climate ( Gulf Stream ) decreasing towards the east. However, there are regional differences, mainly between the mountainous north and the southern lowlands. These regional conditions are shown below. The stated temperature and precipitation values refer to the period 1961 to 1990.

The warmest and driest areas are in the south. Typical here are the Danube lowlands , East Slovak lowlands and lower valleys and basins. The average annual temperature reaches 9 ° C to 11 ° C, in January the average is between −2 ° C and −1 ° C, in July between 18 ° C and 21 ° C. In addition, the temperature values in the west are around 1 ° C higher than in the east. The annual rainfall is also the lowest, from around 500 mm in Senec and Galanta to 550 mm in the eastern Slovak lowlands. This region is represented by the measuring stations Bratislava , Hurbanovo and Košice , while the measuring station Kamenica nad Cirochou represents a transition.

The moderately warm climatic area includes the inner-Carpathian valley basins and the lower mountains, whereby the average temperature generally drops by around 0.6 ° C per 100 meters of altitude and precipitation increases by around 50–60 mm. In the river valleys of the Waag , Nitra or Hron that adjoin the lowlands , the annual temperature fluctuates between 6 ° C and 8 ° C, in the highest basins ( Popradská kotlina , Oravská kotlina ) it drops below 6 ° C. Around 1000 meters altitude, the annual temperature reaches values of 4 ° C to 5 ° C. In the valley basins, the average temperature in January reaches values between −5 ° C and −3 ° C, in July between 14 ° C and 16 ° C. There is annual precipitation of 700–800 mm, in parts of the Zips in the rain shadow of the mountains only about 600 mm. There are measuring stations in Sliač , Poprad and Oravská Lesná .

The entire Tatras, the upper parts of the Low Tatras and the highest mountains of the Little and Great Tatras, the Slovak Beskids and the Slovak Ore Mountains are cold. The climate is characterized by the lowest annual temperatures: around 2000 meters above sea level, the annual average is −1 ° C, in the highest peaks of the Tatra Mountains it is −3 ° C. For January the average values in the Tatras are around –10 ° C, in July the average is around 3 ° C. The annual precipitation varies from about 1400 mm in the Little and Big Fatra and the Low Tatras to more than 2000 mm in the Tatras. The measuring station for this climate is located at the summit of Lomnický štít (2634 m).

Records were set in Komárno with 40.3 ° C (July 20, 2007) and in Vígľaš- Pstruša with −41 ° C (February 11, 1929).

In general, precipitation is concentrated in summer (June to August) with around 40% of the annual values, in spring it falls around 25%, in autumn around 20%, while the remainder of 15% falls in winter. The highest precipitation ever recorded on a day in Salka was a total of 231.9 mm on July 12, 1957. In summer there is often stormy weather, with daily precipitation reaching 100 mm somewhere almost every year. In the mountains as well as in mountain valleys and basins there is stormy weather on average for 30–35 days per year , while this value is lower in the lowlands. Winter storms are rare in Slovakia. Depending on the altitude, it can snow heavily in winter : In the Tatras the peaks can be covered with snow for more than 200 days per year, in the shaded valleys snowfields can sometimes remain all year round. The snow cover falls from 80–120 days in the mountains over 60–80 days in basins up to 40 days in southern Slovakia. Fog occurs particularly in autumn and winter, especially in valley basins, while temperature inversions can occur at higher altitudes in winter .

Environment and nature protection

Nature conservation has a tradition of more than a hundred years in Slovakia, some decisions and regulations on this go back to the Middle Ages. The formalities for nature protection are generally regulated in the Slovak constitution and by the specific “Law for the Protection of Nature and Landscape” (zákon o ochrane prírody a krajiny) . Slovakia was among the first countries in the world to adopt such a legal norm (1955). The Tatra National Park was established by law a few years earlier . The UN biodiversity convention has also been incorporated into the “Law for the Protection of Nature and Landscape” .

From the point of view of nature conservation, Slovakia is divided into five levels of protection, the first level being the lowest and the fifth level being the highest. The national parks (národné parky) and the protected landscape components (chránené krajiné oblasti) represent "large-scale protected areas" (veľkoplošné chránené územia) .

Slovakia has 23 large-scale protected areas as well as hundreds of small-scale protected areas. The first category includes nine national parks . The oldest and largest is the Tatra National Park with 73,800 ha, other important national parks Low Tatras National Park (72,842 ha), Poloniny National Park (29,805 ha), Malá Fatra National Park (22,630 ha) and Slovak Paradise National Park (19,763 ha). In addition, there are 14 landscape protection areas which, in addition to mountains, also place three lowland areas under protection. There are also 1101 small-scale protected areas, 642 protected areas of European importance and 41 bird protection areas.

population

Around 5.46 million people live in the country (as of 2019). The population development has had a rather stagnant course since independence. Life expectancy in the period from 2015 to 2020 was 77.3 years (men: 73.7 years, women: 80.8 years), the average age 41.2 years (as of 2020), with an increasing aging of the population being observed.

Distribution according to nationality and citizenship

The census in Slovakia is between the " nationality " (slowak. Narodnost ) in the sense of ethnic ethnicity and " citizenship " (slovak. Štátne občianstvo ) distinguished. The information on ethnic nationality is based on the self-classification of the population and includes all persons with permanent residence on Slovak territory. The ethnic structure is likely to differ from the results. This applies in particular to the proportion of Roma, which is estimated to be much higher than in official statistics. The so-called “Atlas of Roma communities”, born in 2013, gives an estimate of 402,840 Roma (around 7.5%), Amnesty International estimates the number at 300,000 to 600,000, which corresponds to 5 to 10% of the population. The last census in 2011 in particular showed gross inaccuracies. The Slovak Roma expert Martin Šuvada (2015) estimates the total number of Slovak Roma in his study at 450,000 people. It is clear that the number of Roma will continue to rise due to the high birth rate and that the value will have to be revised upwards in the future. The Roma are the only nationality in Slovakia, the majority of which does not admit to their ethnicity in censuses.

The "Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic" ( Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky , ŠU SR) made the following information for the 5,443,100 inhabitants in 2017 (seven main countries):

| citizenship | Proportion of (%) | number |

|---|---|---|

|

|

98.66 | 5,370,237 |

|

|

0.25 | 13,525 |

|

|

0.19 | 10,248 |

|

|

0.12 | 6,521 |

|

|

0.11 | 5,758 |

|

|

0.08 | 4,083 |

|

|

0.06 | 3,482 |

At the same time, the statistical office reported the following on the ethnic composition: Slovaks (81.5%), Magyars (8.3%), Roma (2%), Czechs (0.7%), Russians (0.6%), Ukrainians (0.2%), Germans (0.1%), Poles (0.1%) and others including those without information (6.4%).

| Slovak population by nationality | |||||||||

| 2011 census | 2001 census | 1991 census | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nationality | number | % | number | % | number | % | |||

| Slovak | 4,352,775 | 80.7 | 4,614,854 | 85.8 | 4,519,328 | 85.7 | |||

| Magyar | 458.476 | 8.5 | 520,528 | 9.7 | 567.296 | 10.8 | |||

| romani | 105,738 | 2.0 | 89,920 | 1.7 | 75,802 | 1.4 | |||

| Russian | 33,428 | 0.6 | 24,201 | 0.4 | 17.197 | 0.3 | |||

| Czech | 30,367 | 0.6 | 44,620 | 0.8 | 52,884 | 1.0 | |||

| Ukrainian | 7,430 | 0.1 | 10,814 | 0.2 | 13,281 | 0.3 | |||

| German | 4,690 | 0.1 | 5,405 | 0.1 | 5,414 | 0.1 | |||

| Moravian | 3,286 | 0.1 | 2,348 | 0.0 | 6,037 | 0.1 | |||

| Polish | 3,084 | 0.1 | 2,602 | 0.0 | 2,659 | 0.1 | |||

| Russian | 1.997 | 0.0 | 1,590 | 0.0 | 1,389 | 0.0 | |||

| Bulgarian | 1,051 | 0.0 | 1,179 | 0.0 | 1,400 | 0.0 | |||

| Croatian | 1,022 | 0.0 | 890 | 0.0 | n / A | n / A | |||

| Serbian | 689 | 0.0 | 434 | 0.0 | n / A | n / A | |||

| Jewish | 631 | 0.0 | 218 | 0.0 | 134 | 0.0 | |||

| other | 9,825 | 0.2 | 5,350 | 0.1 | 2,732 | 0.1 | |||

| not determined | 382.493 | 7.0 | 54.502 | 1.0 | 8,782 | 0.2 | |||

| total | 5,397,036 | 100 | 5,379,455 | 100 | 5,274,335 | 100 | |||

Like Israel and some other Eastern European and Asian states, Slovakia is described as an ethnic democracy with a “constitutional nationalism” in which “the dominance of an ethnic group is institutionalized”. The preamble to the Slovak constitution expresses the ethnonational ideological basis of the Slovak Republic:

“We, the Slovak people, in memory of the political and cultural heritage of our ancestors and the centuries of experience from the struggles for national existence and our own statehood, in the sense of the spiritual heritage of Cyrillios and Methodius and the historical legacy of the Great Moravian Empire , proceeding from the natural right of the peoples to self-determination, together with the members of the national minorities and ethnic groups living in the territory of the Slovak Republic, in the interest of a lasting peaceful cooperation with the other democratic states, in the endeavor to establish a democratic form of government, guarantees for a We, the citizens of the Slovak Republic, resolve this constitution through our representatives to enforce free life, the development of intellectual culture and economic prosperity: […]. "

With this preamble, the Slovak people are defined as a state people. Thus, the preamble does not emphasize sovereignty based on the citizens, but based on the Slovak nation. The Slovak constitution prohibits any discrimination against minorities and guarantees them the right to organize and the possibility of cultural self-determination, but at the same time it functions as an instrument to establish the absolute rule of the majority. The rights of minorities "must not jeopardize the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Slovakia or cause discrimination against the rest of the population". According to Robert J. Kaiser in 2014, the Slovak constitution of 1992 clearly signals that “Slovakia for the Slovaks” is the basis on which the nation-state will be constructed.

languages

According to Art. 6 of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic, Slovak is the state language and, together with Kashubian , Polish , Sorbian and Czech, belongs to the West Slavic branch of the Slavic languages . Slovak is a heavily inflected language with six grammatical cases and is divided into three major dialect groups: West Slovak, Central Slovak and East Slovak . The orthography is based on the Latin alphabet and contains a total of 46 letters, 17 of which have diacritical marks and three are digraphs . Today's written language is based on Middle-Slovak dialects and was codified by Ľudovít Štúr in 1846. When Slovakia joined the EU on May 1, 2004, Slovak also became one of the official languages of the European Union.

Hungarian is widespread in southern Slovakia, while Russian can be found mainly in northeastern Slovakia in the area of the Lower Beskids. Romani is often spoken in Roma communities; German as an autochthonous language has almost disappeared since 1945, apart from smaller linguistic islands. Because they live together in Czechoslovakia and have linguistic similarities, Slovaks can usually understand Czech without any problems. Even after the separation, a high standard is guaranteed mainly by Czech-language television, even if the younger generation can have difficulties communicating. According to a representative survey by the Eurobarometer in 2012, 26% of Slovaks have sufficient English skills to have a conversation, followed by German with 22% and Russian with 17%. English, German, Italian, French, Spanish and Russian are offered in primary schools, with the first foreign language being introduced as a compulsory subject in the third grade. If the first foreign language is not English, this becomes a compulsory subject for the second foreign language from the seventh grade onwards.

According to the law, localities with a minority are those localities in which a non-Slovak population group reached at least 20% of the total population in two or more censuses. In these places, the minority language is used as the second official language, and inscriptions on public buildings are also bilingual. For example, in the central Slovak municipalities of Krahule (German Blaufuss ) and Kunešov (Kuneschhau), German is the second official language. In 2011, against the will of the opposition parties, a law was passed that reduces the percentage to 15%. In addition to German, the languages in question are Hungarian , Czech , Bulgarian , Croatian , Polish , Romani , Ruthenian and Ukrainian .

| Slovak population by language according to 2011 census | |||||||||

| according to mother tongue | according to house language | according to lingua franca | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| language | number | % | number | % | number | % | |||

| Slovak | 4,352,775 | 78.6 | 3,954,149 | 73.3 | 4,337,695 | 80.4 | |||

| Hungarian | 508.714 | 9.4 | 472.212 | 8.7 | 391,577 | 7.3 | |||

| romani | 122,518 | 2.3 | 128,242 | 2.4 | 36,660 | 0.7 | |||

| Russian | 55,469 | 1.0 | 49,860 | 0.9 | 24,524 | 0.5 | |||

| Ukrainian | 5,689 | 0.1 | 2,775 | 0.1 | 1,100 | 0.0 | |||

| Czech | 35,216 | 0.7 | 17,148 | 0.3 | 18,747 | 0.3 | |||

| German | 5,186 | 0.1 | 6,173 | 0.1 | 11,474 | 0.2 | |||

| Polish | 3.119 | 0.1 | 1,316 | 0.0 | 723 | 0.0 | |||

| Croatian | 1,234 | 0.0 | 932 | 0.0 | 383 | 0.0 | |||

| Yiddish | 460 | 0.0 | 203 | 0.0 | 159 | 0.0 | |||

| Bulgarian | 132 | 0.0 | 124 | 0.0 | 68 | 0.0 | |||

| other | 13,585 | 0.3 | 34,992 | 0.7 | 58,614 | 1.1 | |||

| not determined | 405.261 | 7.5 | 728.910 | 13.5 | 515,312 | 9.5 | |||

| total | 5,397,036 | 100 | 5,397,036 | 100 | 5,397,036 | 100 | |||

Religions

Slovakia is a country with a long Christian tradition. The most important denomination is the Roman Catholic Church , to which 62% of the population professed in 2011. The center of the Lutheran Christians are the western border areas with the Czech Republic and above all central Slovakia ; the Reformed population is concentrated in the Hungarian-speaking area in the south. In the north-east of the country there are Greek Catholic believers, mainly members of the Ruthenian minority. The Orthodox Church has 49,000 members. There are also several small Protestant denominations ( Methodists , Baptists , Brethren and Pentecostals ). There are also Jehovah's Witnesses , Seventh-day Adventists, and others.

In 1938 there were around 120,000 Jews in Slovakia , but as a result of the Holocaust and emigration during communism, their number has fallen to around 2,300. The official number of Muslims in Slovakia is not known as Islam was not a separate category in the 2011 census. The number has increased due to migration in recent years. Besides Estonia, Slovakia is the only country within the European Union that does not have a mosque. A tightening of the religious law of 2016 set the minimum number of members of a newly registered religious community to 50,000, which made it almost impossible to recognize Muslims. According to the spokesman for the Islamic Center in Bratislava, Ibrahim Mahmoud, there are currently around 5,000 Muslims living in the Slovak Republic, but they belong to different directions and do not feel represented by anyone.

According to a representative survey by the Eurobarometer , 63% of people in Slovakia believed in God in 2010 , and another 23% only partially believed in a spiritual force . 13% of the respondents believed neither in a god nor in any other spiritual force, 1% of the Slovaks were undecided.

| Population of Slovakia by religion | |||||||||

| 2011 census | 2001 census | 1991 census | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creed | number | % | number | % | number | % | |||

| Roman Catholic Church | 3,347,277 | 62.0 | 3,708,120 | 68.9 | 3,187,120 | 60.4 | |||

| Evangelical Church AB | 316.250 | 5.9 | 372.858 | 6.9 | 326.397 | 6.2 | |||

| Greek Catholic Church | 206,871 | 3.8 | 219.831 | 4.1 | 178,733 | 3.4 | |||

| Reformed churches | 98,797 | 1.8 | 109,735 | 2.0 | 82,545 | 1.6 | |||

| Orthodox Church | 49.133 | 0.9 | 50,363 | 0.9 | 34,376 | 0.7 | |||

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 17,222 | 0.3 | 20,630 | 0.4 | 10,501 | 0.2 | |||

| Methodist Church | 10,328 | 0.2 | 7,347 | 0.1 | 4,359 | 0.1 | |||

| Kresťanské zbory (Christian communities in Slovakia) | 7,720 | 0.1 | 6,519 | 0.1 | 700 | 0.0 | |||

| Apostolic Church | 5,831 | 0.1 | 3,905 | 0.1 | 1,116 | 0.0 | |||

| Fraternal unity of the Baptists | 3,486 | 0.1 | 3,562 | 0.1 | 2,465 | 0.0 | |||

| Brethren Movement | 3,396 | 0.1 | 3,217 | 0.1 | 1,867 | 0.0 | |||

| Seventh-day Adventists | 2,915 | 0.1 | 3,429 | 0.1 | 1,721 | 0.0 | |||

| Judaism | 1999 | 0.0 | 2,310 | 0.0 | 912 | 0.0 | |||

| Czechoslovak Hussite Church | 1,782 | 0.0 | 1,696 | 0.0 | 625 | 0.0 | |||

| Old Catholic Church | 1,687 | 0.0 | 1,733 | 0.0 | 882 | 0.0 | |||

| Bahaitum | 1,065 | 0.0 | n / A | n / A | n / A | n / A | |||

| Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints | 972 | 0.0 | 58 | 0.0 | 91 | 0.0 | |||

| New Apostolic Church | 166 | 0.0 | 22nd | 0.0 | 188 | 0.0 | |||

| other | 23,340 | 0.4 | 6.214 | 0.1 | 6.094 | 0.1 | |||

| not determined | 725.362 | 13.4 | 697,308 | 13.0 | 515,551 | 9.8 | |||

| total | 5,397,036 | 100 | 5,379,455 | 100 | 5,274,335 | 100 | |||

migration

Slovakia is not one of the traditional destination countries for migrants and, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), is a “culturally homogeneous country” that was not affected by the dramatic increase in migration in the 20th century. Until recently, Slovakia was almost exclusively affected by emigration , whose citizens left the country for various reasons. At the beginning of the 20th century, Slovakia was one of the most emigrated areas in the world. Even before the First World War , around 600,000 Slovaks emigrated to the USA alone, and in the interwar period, around 200,000 more residents were added, who left the country primarily for economic reasons. After the Communists came to power in 1948, many residents emigrated, mainly for political reasons. Estimates assume around 440,000 emigrants from all over Czechoslovakia for the period from 1948 to 1989. The mass emigration had many negative consequences for the country: a decrease in the number of young people, in some cases the emigration of many particularly educated residents.

This changed with the accession of Slovakia to the European Union and the Schengen area. Since then, the number of illegal migrants has fallen, while the number of legal migrants tripled. Although Slovakia recorded the second highest increase of all EU countries in the number of its foreign share of the population between 2004 and 2008, the share of foreigners in the population remains at a low level. In 2015, the proportion of foreigners in the total Slovak population was 1.56%, making Slovakia the sixth lowest of all EU countries. Of these, 42% come from the neighboring countries of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Austria and the Ukraine. The next largest group among foreign citizens in Slovakia are people with Southeast European and Russian citizenship (20.5%). A total of 8% of foreigners in Slovakia are of Asian origin. Of the total number of 58,321 asylum applications filed since 1993, 653 people were granted asylum and 672 people were granted subsidiary protection as a further form of international protection. In 2015, 330 asylum applications were made in Slovakia, of which a total of 8 were granted asylum.

history

Primeval times to antiquity

The area of today's Slovakia was already settled by humans before the last Ice Age. Numerous finds of objects of the Gravettian culture of the middle Upper Palaeolithic indicate a settlement at this time, especially in western Slovakia up to today's city of Žilina as well as in eastern Slovakia. Two important finds from prehistoric times are the travertine filling of the skull of a Neanderthal man near Gánovce from the last interglacial period (estimated age 100,000 years) and the Venus figurine from Moravany (estimated age 22,800 years).

The first agricultural settlements appeared around 5000 BC. BC, with numerous finds especially in western and south-eastern Slovakia. These include the linear ceramic culture (including the Želiezovce culture), the Bükker culture , the Lusatian culture and the Puchau culture . According to finds, there were large settlements near Spišský Štvrtok ( Myšia hôrka site ) and Nitriansky Hrádok (near Šurany ). The first people mentioned in writing in this area were the Celts , who began in the 5th century BC. A significant ethnic group of Europe and from the 4th century BC. BC also populated today's Slovakia. With the Celts there was a far-reaching development in the processing of iron, clay, wool and linen. Weapons in particular are among the most common Celtic finds. In the 1st century AD, the Celts were replaced by the Germanic Quads . The area of today's Slovakia was the scene of several Roman-Quadi Wars , of which the Roman inscription in today's Trenčín (then Laugaricio ) testifies. The Roman presence was limited otherwise on the Danube limes , with bearings in Gerulata (now Rusovce ) and Celemantia (now Iža ). Around 200 the Vandals settled in parts of eastern Slovakia.

From the end of the 4th century to the first half of the 5th century, the territory of Slovakia was part of the Kingdom of the Huns . After the end of the Huns, the Ostrogoths came to what is now Slovakia in 469 , but then moved further west. Next, the East Germanic Gepids settled in the Carpathian Basin . At the turn of the 5th and 6th centuries AD, the Lombards reached what is now Slovakia, but moved to northern Italy in 568.

Early Middle Ages (500 to 1000)

The Slavic ancestors of the Slovaks reached the area of today's Slovakia at the end of the 5th century and became the dominant ethnic group there in the course of the 6th century. Their first political entity was possibly the empire of Samo , which emerged in the 7th century, and in the 8th century they were under the rule of the Avars . At the beginning of the 9th century, one of the centers of the early medieval Moravian Empire emerged in the city of Nitra . Prince Pribina , who resided in Nitra - either ruler of an independent principality of Nitra or a Moravian local ruler - had the first Christian church in the area of today's Slovakia consecrated there around the year 828, but was inaugurated around 833 by the Moravian Prince Mojmir I (around 830– 846) exiled.

The Moravian Empire, which was the first significant Slavic state, played and still plays a prominent role in the Slovak national identity. Under the Moravian Prince Rastislav (846–870), the Moravians rebelled successfully against the East Frankish domination several times , and the Byzantine priests Cyril and Methodius introduced the Slavic written language they had created in Moravia as the liturgical language. Rastislav's successor Svatopluk I (871-894) continued his independence policy and created a large Slavic empire through the annexation of Wislania , Bohemia and possibly Lusatia , Silesia and Pannonia , which he successfully defended against the attacks of the Eastern Franks , Bulgarians and Magyars . After Svatopluk I's death in 894, the Moravian Empire - internally weakened by a civil war between his sons - went under in the first decade of the 10th century after several attacks by the Magyars, and the Magyars defeated a Bavarian army in the Battle of Pressburg . In the course of the 10th century, especially after the Magyar defeat on the Lechfeld in 955, the area of today's Slovakia gradually came under the rule of the newly emerging Hungarian state .

Upper Hungarian era (1000 to 1918)

In the year 1000 the Hungarian King Stephen I founded the multi-ethnic Kingdom of Hungary , in which the territory of Slovakia, however, formed an independent administrative unit as a feudal duchy until 1108. After that, the territory of Slovakia was fully integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary for more than 800 years. In 1075 the monastery in Hronský Beňadik was founded in the course of Christianization , and around 1110 the diocese of Nitra was re-established. The Mongol storms in 1241 and 1242 depopulated large parts of the national territory, whereupon German settlers (see Carpathian Germans ) were brought into the country for resettlement. These favored the heyday of Upper Hungarian mining in the 13th and 14th centuries, which gained European and world-wide importance. Another consequence was the construction of numerous castles. In the 14th century the first Wallachians came to Slovakia to colonize the country's plateaus. She was gradually Slovakized and Catholicized. At the same time, the Jews also came . After the Árpáden died out , there was a feudal anarchy with several oligarchs (e.g. Mattäus Csák ), which was ended after 20 years by Charles I from the Anjou family . In the course of the Hussite Wars between 1428 and 1433 large parts of the country were heavily devastated. In 1465 the first university on Slovak territory was founded in Pressburg (now Bratislava) on behalf of the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus . However, it was closed after his death in 1490.

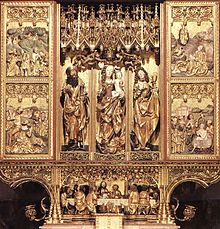

After the defeat of the Hungarian army by the Turks in 1526, Hungary became part of the Habsburg monarchy . After the Turks had conquered most of Hungary up to today's Slovakia, today's Slovak capital Bratislava became the capital of Hungary and the coronation city of the Hungarian kings (until 1783 or 1830) and the city of Tyrnau became the center of the Hungarian church. Today's eastern Slovakia was temporarily under the rule of the Turkish vassal Transylvania and parts of southern central Slovakia around Fiľakovo were ruled directly by the Ottoman Empire . After that, the country suffered from almost constant Turkish wars ; in the 17th century Upper Hungary (Slovakia) was the center of the anti-Habsburg Kuruc uprisings . The Reformation in Hungary that has been going on since 1521 was counteracted in the 17th century by the Counter Reformation . After the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna and the Battle of Kahlenberg in 1683, the Ottomans were gradually ousted, while the class revolts only came to an end with the Peace of Sathmar (1711).

In the 18th century the area of today's Slovakia was the economic center of the Kingdom of Hungary. With the ongoing reconstruction of the country, Slovakia lost its supremacy in the kingdom when the University of Tyrnau , capital and seat of the Archbishop of Gran, was moved to Buda and Esztergom . The national rebirth of the Slovaks began at the end of the 18th century . The Catholic priest Anton Bernolák created the first written Slovak language in 1787, but it did not catch on. Since the beginning of the 19th century, the Slovak national movement under Ján Kollár and Pavel Jozef Šafárik pursued intensive cooperation with the Czech national movement active in the Austrian part of the monarchy. In 1846 Ľudovít Štúr published the Slovak written language, which is still valid today . Under Štúr's leadership, armed Slovak volunteer organizations fought alongside Croats, Serbs and Romanians during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848/1849 for the separation of their territories from the Magyar-dominated Kingdom of Hungary, but this failed. After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise in 1867 , there was a repressive Magyarization policy , which threatened the national existence of the Slovaks. Except for a narrow strip of north-east Slovakia in the winter battles of 1914/15, the country was spared the direct effects of the First World War .

Interwar Period and the Slovak State (1918 to 1945)

After the First World War , Slovaks and Czechs founded their joint state, Czechoslovakia , in 1918 , and Milan Rastislav Štefánik is revered by the Slovaks as one of its founding fathers . With the Treaty of Trianon , Slovakia was finally separated from Hungary after 1000 years. In the constitution of Czechoslovakia of February 29, 1920, among other things, the general active and passive right to vote for women was introduced, which also applies in today's Slovakia. Until 1938, Czechoslovakia was the only state in Eastern Europe to enable the Slovaks to develop democratically and to protect themselves from Hungarian revisionism , but tensions between Slovaks and Czechs increased because of the state doctrine of Czechoslovakism and the centralism of the government in Prague. The nationalist-clerical Ludaks, led by the Catholic priest Andrej Hlinka, developed into the most important mouthpiece for the Slovak demands for autonomy within the Czechoslovak state.

In September 1938, Czechoslovakia was targeted by the National Socialist Third Reich and, as a result of the Munich Agreement and the First Vienna Arbitration, lost large parts of its territory. In March 1939, the rest of the state, which had meanwhile been renamed Czecho-Slovakia , was smashed when Slovak politicians declared an independent Slovak state after German threats of a Hungarian occupation of Slovakia . This first Slovak nation-state was a one-party dictatorship of the Ludaks under President Jozef Tiso and Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka , with Tuka in particular advocating unconditional collaboration with the Third Reich. Slovakia participated in the invasion of Poland in 1939 and, from 1941, in the war against the Soviet Union . In addition, anti-Semitic laws were passed and in 1942 two thirds of Slovak Jews were deported to German extermination camps. The Slovak National Uprising, directed by parts of the Slovak army against the invasion of the Wehrmacht and the Ludaken regime in August 1944 , was put down after two months. Slovakia was occupied by the Red Army in April 1945 and after the Second World War it was part of the newly founded Czechoslovakia.

In the re-established Czechoslovakia (1945 to 1992)

In 1948 the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) took power in the state. A Stalinist dictatorship followed under the party leaders Klement Gottwald and Antonín Novotný . In the 1960s, the Slovak part of the country was liberalized after Alexander Dubček became First Secretary of the Slovak Communists in 1963 . When Dubček also rose to become party leader of the entire KSČ at the beginning of 1968, the so-called Prague Spring occurred , which was however crushed by the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops (with the exception of Albania, the GDR and Romania). Under Dubček's successor Gustáv Husák , the so-called normalization followed , in which the country was reoriented in a pro-Soviet direction. The only point of Dubček's reform program was the federalization of the state, so that now a Slovak Socialist Republic and a Czech Socialist Republic formed Czechoslovakia.

In November 1989, the Velvet Revolution brought about the bloodless overthrow of the communist regime, the new Czechoslovakian president was the dissident Václav Havel , the former reform communist Alexander Dubček was elected parliamentary president. After the democratic turnaround, tensions between the Slovaks and the Czechs quickly returned. The first conflict became the dispute over the new state name, known as the dash war . After the first free elections in June 1990, the different interests in economic, national and foreign policy issues became clear. The final break came after the 1992 elections. The Slovak Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar and the Czech Prime Minister Václav Klaus could not agree on a joint federal government and agreed on the amicable dissolution of Czechoslovakia and its division into two independent states on New Year's Eve on January 1, 1993 took place peacefully.

Slovak Republic (since 1993)

After independence, Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar dominated Slovak politics until 1998 , who ruled increasingly authoritarian , especially after his victory in the National Council election in 1994 . In terms of economic policy, Mečiar refused to completely open up the domestic economy, as was demanded by the West, and did not favor foreign companies in privatization, but primarily Slovak companies, mostly related to his party. In terms of foreign policy, Mečiar tried to lead Slovakia into the EU and NATO , but at the same time he wanted to maintain a balance between Russia and the West in terms of foreign policy orientation . However, since its domestic and economic policy repeatedly violated Western guidelines, Slovakia increasingly moved closer to Russia and became isolated from the West.

The government under Mikuláš Dzurinda , which came to power after the National Council elections in 1998 , initiated an extensive opening of the Slovak economy to foreign investors and began with large-scale austerity measures in the public sector. Foreign policy was now exclusively geared towards the USA and the EU , but joining NATO and the European Union did not take place until 2004, after Dzurinda was able to prevail again in the 2002 election . In his second term in office, Dzurinda implemented a strongly neoliberal policy in Slovakia, under which Slovakia was the first country to introduce a flat tax of 19%. The Dzurinda government was praised as a reform government in western countries, but met with growing discontent among the Slovak population because of its social cuts.

In the National Council election in 2006 , the left-wing populist Smer-SD of Robert Fico won , which initially faced strong criticism from the West after a coalition agreement with the nationalists and the Mečiar party . Under the Fico government, Slovakia joined the Schengen Agreement in 2007 , and the euro was introduced on January 1, 2009. Foreign policy was again oriented more towards Russia, but continued to emphasize membership of the EU and NATO. The neoliberal economic policy of the Dzurinda era was ended by the Fico government and workers rights were expanded, but the flat tax was retained for the time being. From 2010 to 2011 there was another short-term, economically liberal government under Prime Minister Iveta Radičová , who wanted to tie in with the policies of the Dzurinda government. The governing coalition broke up prematurely in 2011 because of the disagreement between the governing parties on the EU bailout fund .

In the 2012 National Council election , Robert Fico's Smer-SD won an absolute majority of the votes and was thus able to form the first sole government in Slovakia since 1989. The flat tax, which was retained during the first Fico government, has now been abolished as part of a reorganization of the 2013 state budget and corporate taxes and taxes for top earners have been increased. The budget deficit was reduced from 4.3% to 3% between 2013 and 2014, which means that Slovakia again met the Maastricht criteria . In foreign policy, the second Fico government supported the common EU position towards Russia during the Crimean crisis and the war in Ukraine since 2014 , but at the same time sharply criticized the economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU. During the refugee crisis in Europe in 2015 , the Slovak government, like the governments of other former Eastern Bloc countries , declared that it preferred Christian refugees and strictly opposed an EU quota system for the redistribution of refugees from Greece and Italy as well as a permanent, mandatory distribution key to all EU countries.

After the National Council election in 2016 , Ficos Smer-SD lost its previous absolute majority significantly and formed a broad left-right coalition . On March 14, 2018, Robert Fico resigned as a result of the scandal surrounding the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and subsequent protests. His successor was party colleague Peter Pellegrini . In the 2019 presidential election , the liberal candidate Zuzana Čaputová won the runoff against the Smer SD candidate Maroš Šefčovič and has been Slovakia’s first female president since June 15, 2019. After an election campaign focused on the issues of corruption and the murder of Kuciak, the Smer-SD lost the 2020 National Council elections . The strongest force has now become the OĽaNO , which also provides the prime minister. The Matovič government took office amid the COVID-19 pandemic on March 21, 2020.

politics

Political system

According to the 1992 Constitution, Slovakia is a republic that is a parliamentary democracy. The head of state is the president, who is elected for a five-year term. He shares his power with parliament. The executive power in the country is exercised by the government of the Slovak Republic headed by the head of the government (prime minister).

The government consists of the Prime Minister (Slovakian predseda vlády ), his deputies and ministers. The government appointed by the President must submit its political program to Parliament within 30 days of its appointment and seek the confidence of the House. In addition, it can ask the National Council at any time to express its confidence in it and, in principle, combine every vote with a vote of confidence. For its part, parliament can at any time deny confidence in the government or one of its members. This requires an absolute majority of all MPs, but the government's vote of confidence is decided by a simple majority. The loss of parliamentary confidence inevitably results in the President's removal from office.

| function | image | Surname | Political party | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| President |

|

Zuzana Čaputová | independently | In office since 2019, first woman to hold office as President |

| Prime Minister | Igor Matovič | OĽaNO | In office since 2020 | |

| President of Parliament | Boris Kollár | Sme rodina | In office since 2020 |

Under the third Mečiar government (1994–1998) Slovakia was also characterized as an illiberal democracy , but under the Dzurinda government (1998–2006) it broke away from this consolidation towards the rule of law. In the 2019 Democracy Index, Slovakia ranks 42nd out of 167 countries, making it an "incomplete democracy".

Parliament and party landscape

| Political party | Alignment | Chair | Share of the vote | position | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Obyčajní ľudia a nezávislé osobnosti (OĽaNO) Ordinary people and independent people |

Protest party , economically liberal conservatives |

Igor Matovič | 25.0% | government | |

|

Smer - sociálna demokracia (Smer-SD) direction - social democracy |

Left-wing populists , social democrats |

Robert Fico | 18.3% | opposition | |

|

Sme rodina (SR) We are family |

Protest party , populists |

Boris Kollár | 8.2% | government | |

|

Kotlebovci - Ľudová strana Naše Slovensko (ĽSNS) Kotlebians - People's Party Our Slovakia |

Ultra-nationalists , right-wing extremists |

Marian Kotleba | 8.0% | opposition | |

|

Sloboda a Solidarita (SaS) freedom and solidarity |

Libertarians , liberals |

Richard Sulík | 6.2% | government | |

|

Za ľudí For the people |

Christian Democrats , Liberals |

Andrei Kiska | 5.8% | government | |

The Parliament of Slovakia is the National Council of the Slovak Republic , which exercises the legislature as a unicameral parliament with a total of 150 members and is re-elected every four years. Election is open to all persons who are on election day at least 18 years old and it can also outside their own polling station with a ballot paper (hlasovací Preukaz) are matched.

In and immediately after the fall of the Wall in November 1989, numerous parties and political movements were founded, but they did not fit into a stable party system. Internal conflicts and splits led to the formation of new parties. In the meantime (as of 2010) there are over 100 political parties in Slovakia, which, according to the political scientist Rüdiger Kipke, seems far from a consolidation of the party system.

Since its independence in 1993, Slovakia has been divided into two large main political blocks: The first camp with an eastern orientation in foreign policy is described as "left-wing populist" or "social-national". In the 1990s the camp was dominated by the HZDS and since the mid-2000s by the Smer-SD . In addition, the SNS and the rather marginal communist party KSS are added to the camp. The second camp, with a more western orientation in foreign policy, is described as the “center-right” and historically comprised the parties SDKÚ and KDH in particular ; Today the parties SaS , OĽaNO , Progresívne Slovensko , Spolu and Za ľudí also belong to this camp . In recent years, the popularity of far-right and populist parties, especially ĽSNS and Sme rodina, has also increased .

An essential line of conflict within society with a corresponding influence on the party system and voting decisions is initially that between "Westerners" and national traditionalists. This manifests the deeply rooted contradiction between the supporters of a secular-liberal order of western character (for example, earlier SDKÚ-DS ) and the defenders of the historically formed community (e.g. formerly HZDS ). The socio-economic dividing line, the contrast between liberal market economists (SDKÚ-DS) and state interventionists (e.g. Smer-SD ) is also important. Finally, there is the national-ethnic dividing line, the contrast between Slovaks (e.g. SNS ) and Hungarians (e.g. Most – Híd ).

In the National Council election on February 29, 2020 , the conservative protest party OĽaNO (25.0%) led by Igor Matovič was the strongest party with 53 seats, an increase of 14 percentage points compared to the 2016 election . The leftist Smer-SD of Robert Fico fell from 28.3% to 18.3% (38 seats) back and missed the first time since the 2006 election victory. The populist protest party Sme rodina (8.2%) of Boris Kollár posted slight gains over the last election, while supporting the ultra-nationalist-extremist LSNS (8.0%) remained almost the same, but won as Sme Rodina 17 seats in the National Council. The neoliberal SaS (6.2%, 13 seats), which clearly distinguishes itself from Fico , was able to make it into the National Council, as did the centrist Za ľudí party of ex-President Andrej Kiska with 5.8% and 12 seats. The liberal coalition PS - Spolu (6.96%) narrowly failed because of the 7% threshold for coalitions. The Catholic-conservative KDH remained outside parliament with 4.7% for the second time in a row since the 1990 elections, while the national-conservative SNS lost all 15 seats in parliament with only 3.2%. For the first time since the 1990 elections, no minority party is represented in parliament, as both the Hungarian SMK-MKP (3.9%) and the Slovak-Hungarian party Most-Híd (2.1%) have a 5% threshold failed.

Administrative division

Today's Slovakia has been divided into eight “ Kraje ” (regional associations / regions) since 1996 , each with a regional capital. At the same time, since 2001, after a slight decentralization reform, the Krajs have had a small amount of autonomy in the design of certain areas (e.g. secondary schools, health care and infrastructure). Each Kraj has a state capital and a state chairman who is elected every four years. These self-governing landscape associations are territorially identical to the state landscape associations.

| Kraj | Administrative headquarters | Area in km² |

Residents | Density of population / km² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bratislavský kraj | Bratislava | 2,053 | 669,592 | 326 |

| Trnavský kraj | Trnava | 4.158 | 564.917 | 136 |

| Trenčiansky kraj | Trenčín | 4,502 | 584,569 | 130 |

| Nitriansky kraj | Nitra | 6.344 | 674.306 | 106 |

| Žilinský kraj | Žilina | 6,809 | 691.509 | 102 |

| Banskobystrický kraj | Banská Bystrica | 9,454 | 645.276 | 68 |

| Prešovský kraj | Prešov | 8,974 | 826.244 | 92 |

| Košický kraj | Košice | 6,755 | 801.460 | 119 |

| 49,049 | 5,457,873 | 111 |

As a sub-unit of the Krajs, 79 okresy were formed at the same time (comparable to political districts in Austria or (rural) districts in Germany), with Bratislava being divided into five and Košice into four okresy. In the beginning, district authorities (okresné úrady) were responsible for these . From 2004 to 2013, the Okresy were administratively insignificant, but had been kept for statistical purposes and for issuing license plates . For the state administration there were 50 areas, which usually comprised several districts and were administered by the district authorities. In 2007, landscape association authorities for general administration were also abolished and replaced by so-called district authorities in the state capital, which had their area of competence throughout the Kraj.

In a major administrative reform that amalgamated various area offices, 72 district authorities were reintroduced on October 1, 2013. These copy the Okresy with the exception of the urban districts of Bratislava and Košice, where there is only one district authority.

For their part, the okresy are made up of communities (obce) that have competencies primarily in the areas of education, culture, the environment, maintenance of local streets, squares and parks, and building permit procedures. Each municipality has a mayor and a municipal council, who are elected every four years in local elections. Municipalities can have city and municipality parts, but with the exception of Bratislava and Košice these have no administrative significance. There are a total of 2890 municipalities in Slovakia, 141 of which are designated cities. This number also includes the three military areas of Záhorie , Lešť and Valaškovce . The Javorina military area was abolished on January 1, 2011.

By far the largest city is the capital Bratislava with 437,725 inhabitants, the only other major city is Košice with 238,593 inhabitants. Towns with more than 50,000 inhabitants include Prešov (88,464 pop), Žilina (80,727 pop), Banská Bystrica (78,084 pop), Nitra (76,533 pop), Trnava (65,033 pop), Trenčín (55,383 pop). ), Martin (54,168 pop) and Poprad (51,235 pop) (all information as of December 31, 2019). From an administrative point of view, the distinction between town and municipality is meaningless, except in the case of Bratislava and Košice, however, mayors of the towns carry the official designation primátor , while for "ordinary" mayors this is starosta . Special laws regulate the position of Bratislava and Košice, which in addition to a city level also have district levels, each of which has its own district mayor and administration. The above competencies are shared between the city and the districts.

History of the administrative division

The administrative structure of Slovakia has been subject to intense change, especially since the establishment of the first Czechoslovak Republic. As part of the Kingdom of Hungary, the area of Slovakia was integrated into the county system, in which counties formed the highest administrative unit. The number of these units in Slovakia was 17 up to the 13th century, 21 from the 13th century to 1882 and 20 thereafter (see also the list of historical counties of Hungary ). The historical counties in Slovakia were as follows (status after 1882, names German / Hungarian / Slovak):

There was also a tiny part of Szabolcs County in south-eastern Slovakia.

Only in the years 1785–1790 and 1850–1860 were there districts as higher administrative units: in 1785, following reforms by Joseph II , the area of Slovakia was largely divided into three districts (Neutra, Neusohl and Kaschau) with smaller parts by three others (Raab, Pesth and Munkatsch). During the time of Bach absolutism in the Austrian Empire from 1850 to 1860, districts emerged again, with Slovakia mainly divided into two districts (Pressburg and Kaschau), with a small part in the district of Ödenburg. In both reforms, the number of counties fell to 16 and 18 respectively.

The newly created Czechoslovakia took over the existing county system as a provisional arrangement. After some changes, the number of counties was reduced to 16. In 1923, so-called Großgaue (veľžupy) (officially only župy ) and Okresy were introduced. There were six Großgaue (Bratislava, Nitra, Považie, Zvolen, Untertatra and Košice) with 79 okresy as well as a tiny part of the seventh Großgau (Uschhorod, near Lekárovce ). After the abolition of the Großgaue in 1928, Slovakia was now part of Czechoslovakia, divided into 77 Okresy. In the Slovak state, the territory was divided into six districts (Bratislava, Nitra, Trenčín, Pohronie, Tatra and Šariš-Zemplín) with 60 Okresy between 1940 and 1945. In the restored Czechoslovakia, one year after the February coup of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, Slovakia was divided into six regional associations (Bratislava, Nitra, Žilina, Banská Bystrica, Prešov and Košice) and 90 (when it was founded), most recently 91 Okresy.

Between 1960 and 1990, Slovakia consisted of only three major regional associations: Western Slovakia ( Západoslovenský kraj ), Central Slovakia ( Stredoslovenský kraj ) and Eastern Slovakia ( Východoslovenský kraj ). In addition, the city of Bratislava existed from 1968/1970 to 1990 in the rank of a landscape association. Initially there were 33 okresy, the number of which increased to 38 following an administrative reform in 1968. The 38 Okresy continued to exist until 1996, when the current administrative structure was introduced.

Foreign policy

Slovakia has been part of the EU and NATO since 2004 . However, the foreign policy orientation of the country has been subject to strong fluctuations since its independence. The concept of a foreign policy based on a balance between Russia and the West and the concept of an emphatically pro-Western foreign policy stand in opposition. The former was represented by Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar during the 1990s and has been promoted again since 2006 by the multiple Prime Minister Robert Fico . The pronounced pro-Western foreign policy was pursued by the governments of Dzurinda (1998–2006) and Radičová (2010–2012), which also supported the military operations of NATO in the war in Kosovo , Afghanistan , Iraq and in Libya . The Fico government, on the other hand, demonstratively sided with Russia during the war in Georgia in 2008 and also rejects the missile shield propagated by the USA in Central Europe and the independence of Kosovo . In 2014, Prime Minister Fico declared against the background of the Crimean crisis that Slovakia rejects the "senseless" sanctions against Russia, as they caused Slovakia "considerable damage".

With regard to its neighbors, Slovakia has the best relationship with the former "brother" Czech Republic . In addition to the close economic relations, the mutual sympathy of the two nations, which had to suffer from national disputes in the early 1990s, has risen continuously since their independence in 1993 and is currently at a record high. Several joint TV shows will be broadcast, including the entertainment program Czech-Slovak Superstar , and a joint soccer and ice hockey league was also planned. Newly elected presidents and heads of government of the two countries traditionally make their first foreign visit to the capital of the other country - regardless of their political orientation.

Relations with our southern neighbor, Hungary , are the most difficult . Historically, they are heavily burdened by the fact that the Slovaks belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary for a thousand years, whose government tried to assimilate the non-Magyar peoples of Hungary through a repressive Magyarization policy in the 19th century , as well as the occupation of southern and eastern Slovakia by Hungarian troops before the Second World War (see First Vienna arbitration and the Slovak-Hungarian War ). The Hungarian army was also involved in the suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968 under the Warsaw Pact . Since the independence of Slovakia in 1993, the relationship between the two states has been characterized by chronic disputes over the Hungarian minority living in Slovakia , the Gabčíkovo hydropower plant and the Beneš decrees , which also affected the Hungarians living in what was then Czechoslovakia. Since Fico's second government took office , observers have been speaking of a clear improvement in relations between the Slovak government and the Hungarian government under Viktor Orbán , as both sides are now holding back on the minority issue.

In contrast, bilateral relations with Austria are not historically burdened. The only point of contention in the otherwise good conditions is the Bohunice nuclear power plant in Slovakia . Slovakia insists on adhering to nuclear power in its energy policy, while Austria insists on corresponding safety standards.

The relationship with neighboring Poland can be described as good and free from conflict. Slovakia generally has good relations with its eastern and largest neighbor Ukraine , however, as a result of the gas crisis in 2009 and the crisis in Ukraine in 2014 , differences arose between the Ukrainian government and the government in Bratislava, which was concerned about the gas supply to Slovakia.

With the onset of the refugee crisis in Europe in 2015, Slovakia was one of the countries that strictly opposed a distribution quota in the EU for incoming refugees. The Slovak government under Robert Fico sued in December 2015 against such a quota. Together with Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland, Slovakia is part of the Visegrád Group , which primarily relies on isolation when it comes to the refugee issue. Slovakia particularly emphasizes that it will not accept any Muslim war refugees. The Ministry of the Interior in Bratislava declared at the beginning of 2016 that they would not feel at home in Slovakia either. In the Catholic dominated Slovakia only Christians are accepted. In 2015, only 169 people applied for political asylum in Slovakia; eight of them were granted asylum.

Like its neighbor, the Czech Republic, the country has had observer status in the Community of Portuguese- Speaking Countries (CPLP) since 2016 .

Police and military

The centralized “ Police Corps of the Slovak Republic ” (Slovak: Policajný zbor Slovenskej republiky ) is responsible for tasks in the field of internal public order and security as well as the fight against crime . The police are divided into criminal , financial, security, traffic, rail, border and immigration police as well as property protection and special services. In 2018 the workforce was around 22,500 civil servants. In addition, municipalities can set up their own municipal and city police forces ( obecná polícia or mestská polícia ) whose powers focus on traffic monitoring (administrative offenses), implementation of municipal ordinances and the maintenance of public order in the municipality. The Military Police (vojenská polícia) is part of the Slovak Armed Forces and is therefore under the Ministry of Defense.

The Slovak Armed Forces (Slovak: Ozbrojené sily Slovenskej republiky ) have been a fully professional army since 2006 , are subordinate to the Ministry of Defense and consist of the armed forces:

- Slovak Army

- Slovak Air Force

- Special operations forces

As of December 31, 2018, Slovakia had 12,342 soldiers . In 2017, the Slovak Armed Forces had 30 main battle tanks, 313 armored personnel carriers, 67 pieces of artillery and 16 fighter jets. In 2017, Slovakia spent almost 1.2 percent of its economic output or 1.1 billion US dollars on its armed forces.

Slovakia has been a NATO member since 2004 . General conscription was lifted in peacetime in 2006, and since then citizens between the ages of 18 and 30 have been able to do voluntary military service. Women have been allowed to serve in the military since 2012. In 2017, the lack of a large number of hand-held anti-tank shells and 300,000 rounds of ammunition was noted.

Judiciary and prison system

Slovak law belongs to the Roman-Germanic legal system and is divided into public law and private law . According to Article 1 of the Constitution, the Slovak Republic sees itself as a constitutional state . The system of the judiciary consists of the constitutional court and general courts on three levels, with a two-level series of instances . The judicial system is based on Article 143 of the Constitution (for the Constitutional Court) and Law No. 757/2004 (for general courts).

The Constitutional Court ( Ústavný súd Slovenskej republiky in Slovak ) is responsible for constitutional issues and can override unconstitutional laws. The court is composed of 13 judges who are appointed by the President of the Republic for a period of 12 years on the proposal of the National Council. Its seat is in Košice.

The highest general court is the Supreme Court of the Slovak Republic (Slovak Najvyšší súd Slovenskej republiky ) in Bratislava. Below are the eight regional courts (Slovak Krajský súd ) with first instance in administrative matters and 54 district courts (Slovak Okresný súd ), which act as first instance in civil and criminal matters. Other constitutional bodies are the Public Prosecutor's Office (Slovak prokuratúra ), Ombudsman (Slovak verejný ochranca práv , unofficially ombudsman ) and the Supreme Control Authority of the Slovak Republic (Slovak Najvyšší kontrolný úrad Slovenskej republiky , abbreviation NKÚ ).

Since 2009 there has also been a special criminal court (Slovak : Špecializovaný trestný súd ) based in Pezinok as the successor to the Special Court (Slovak : Špeciálny súd ) established in 2004 for criminal cases in the area of corruption, bribery, organized crime and particularly serious financial and property crimes. Together with the original special court, the authority of the special prosecutor's office (Slovak Úrad špeciálnej prokuratúry ) was created. The formerly existing military courts (Slovak Sg. Vojenský súd ) were abolished on March 31, 2009 and their powers were transferred to general courts.

The Corps of the Prison and Justice Guards (Slovak Zbor väzenskej a justičnej stráže , abbreviation ZVJS) is responsible for the execution of prison sentences . The corps operates 18 prisons across Slovakia, the oldest being Leopoldov Prison . As of April 1, 2020, there were 10,543 prisoners in Slovak prisons, which corresponds to 195 inmates per 100,000 population.