High Tatras

| High Tatras | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Aerial view of the High Tatras from the Oswald-Balzer-Weg |

||

| Highest peak | Gerlachovský štít (Gerlsdorfer Peak) ( 2655 m nm ) | |

| location | Slovakia, Poland | |

| part of | Western Carpathians | |

|

|

||

| Coordinates | 49 ° 10 ′ N , 20 ° 8 ′ E | |

The High Tatras ( Polish Tatry Wysokie , Slovak Vysoké Tatry ), a part of the Tatra Mountains . It is the highest part of the Carpathian Mountains and two thirds belong to Slovakia and one third to Poland . In both countries, it is in each case as part of a National Park under special protection, at the same time it is a biosphere reserve of UNESCO . On the Slovak side, the High Tatras mainly belong to the Spiš , only the extreme southwest to the Liptov . Since 1999 the Slovak municipalities on the south side of the High Tatras have been grouped together as a town under the Slovak name of the High Tatras, Vysoké Tatry , as they were between 1947 and 1960 . In Poland, the High Tatras belongs to the Podhale region and the municipalities of Zakopane , Poronin and Bukowina Tatrzańska in the Powiat Tatrzański district in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship .

etymology

"Tritri" (1086), "Tatry" (1255), in the 13th / 14th Century "Thorholl" (1256), "Thorchal", "Tarczal", "Tutur", "Thurthul" which could mean hell, "Tołtry, Toutry", as well as "Schneegebürg" ( Montes nivium ). Adam Mickiewicz used the names Tatry and Krępak at the beginning of the 19th century , just like Spener a hundred years earlier. In 1790, Baltazar Hacquet wrote that the Slavs call the mountains Tatari or Tatri , because Tartars previously lived there. According to Jan Michał Rozwadowski , the name Tatry (Old Polish Tartry) has a Celtic origin. The term tertre means mountains . Cyprian Kamil Norwid shared this opinion . Some authors see a Drak or a Trakish origin. At the beginning of the 19th century, the High Tatras were known as Karpak ( highest snow-capped mountain ), from the Illirischen karpe that is rock , which occurs in old Polish in the form karp , z. B. karpętne or s (z) karpa - mountain slope. In official Hungarian documents of the 13th and 14th centuries, the Carpathian Mountains and especially the Tatras are referred to as Thorchal , Tarczal and Schneegebürg , Montes Nivium . The name High Tatras comes from the fact that it towers above the other mountain ranges of the Tatra Mountains, the Western Tatras and the Belianske Tatras by approx. 500 m.

geology

The High Tatras are, like the whole Tatras, a relatively young fold mountain range. In contrast to the Western Tatras, however, it consists of granites that were formed from lava solidified during the geological age of the Carboniferous . The granite rock of the High Tatras is about 315 million years old. Rock layers from the Permian and Triassic also occur. During the Chalk Age, tectonic events caused the rocks of the High Tatras to fold and shift several kilometers to the north. In the Eocene , the area of the High Tatras, especially in the north of the High Tatras, was flooded by a shallow sea. Layers of sediment were deposited in the water. On the other hand, parts of the granite rock already protruded from the sea and were subject to erosion , in particular rock layers from the Jura and the Cretaceous have largely eroded. They can no longer be found on the southern slopes. Sediments and sedimentary rocks therefore only occur on the northern slopes of the High Tatras and there in particular on the mountains Żółta Turnia , Mała Koszysta , Gęsia Szyja , Kopy Sołtysie , Szeroka Jaworzyńska and Jagnięcy Szczyt . The last folding of the High Tatras took place in the Miocene . The High Tatras themselves, like the whole of the Carpathian Mountains and many other high mountains in Europe, came into being during the Alpine Orogeny . It owes its current appearance to the glaciers of the ice ages. The glacial cirques were particularly north of the main ridge at an altitude of 1400 m to 1700 m. The mountain lakes of the High Tatras are cirque lakes that are relics of the glacial cirques. The glacier tongues led the mountain valleys in their entire lengths down to approx. 1000 m. This created the characteristic U-shaped trough valleys of the Tatra Mountains. Glacier moraines can be found in the mountain valleys and at the foot of the High Tatras.

history

The whole Tatras had been on the border between Poland and Hungary since the 11th century. One of the most important trade routes of the Middle Ages ran east of the Tatras, connecting the Polish capital Krakow with the Hungarian capital Buda . In order to protect the merchants from raids by the band of robbers living in the Tatra Mountains, numerous castles were built at the foot of the Tatra Mountains. a. on the Dunajec in Czorsztyn and Niedzica and in the Zips . In addition to robbers, the Tatras were also visited by treasure hunters and miners in the Middle Ages. From some topographical names, such as This can still be seen from the mountain Miedziane , in German Kupferberg, west of the Morskie Oko . Cattle breeding, alpine pasture and forestry came to the Tatras in the late Middle Ages and early modern times.

The first documented tourist trip to the High Tatras took place in the 16th century. The widowed Princess Ostrogski Beata Łaska z Kościeleckich married Albert ( pol. Olbracht) Łaski, Lord of Kesmark in 1564 and settled there. On June 10, 1565, she undertook a spectacular mountain tour in the High Tatras.

The first documented ascents of the High Tatras peaks took place in 1615 and 1664. In 1683 Daniel Speer described his travels in the High Tatras in his work Hungarian or Dacian Simplicissimus. In 1782 a detailed map of the High Tatras was made. At the end of the 18th century, the High Tatras were researched by the French Belshazzar Hacquet and the English Robert Townson and described in scientific publications. Stanisław Staszic was the first Pole to scientifically research the High Tatras. He stayed in the Tatras from 1803 to 1805 and climbed numerous peaks. In 1815 his work O ziemiorodztwie Karpatów u. a. over the High Tatras. He was followed by numerous other Polish geologists and mountaineers in the first half of the 19th century. The first travel guides of the High Tatras appeared around the middle of the century. In 1873 the Polish Tatra Association and the Hungarian Carpathian Association were founded. The Polish Tatra Association had the first three mountain huts built in the High Tatras between 1874 and 1876. Most of the Tatra peaks were climbed for the first time in the 1870s. Most winter ascents were documented in the 1880s.

During this period Zakopane became very popular among Polish writers, poets, architects and artists. A Zakopane style of its own developed in Polish art history. The mountain rescue service in the High Tatras has existed since the turn of the century before last. Many of those who worked for the High Tatras in the 19th and 20th centuries have found their final resting place in the Cmentarz Zasłużonych na Pęksowym Brzyzku cemetery in Zakopane.

The exact course of the border between Poland and Hungary or between Galicia (after the First Partition of Poland in 1772) was not determined even after the Hungarian-Austrian settlement in 1867. The exact demarcation in the High Tatras was only drawn at the beginning of the 20th century by a judgment of an Austrian court in Graz. In the period between the World Wars, the High Tatras developed into a popular excursion area for the well-heeled citizens of Poland and Czechoslovakia. During the Second World War, the Tatra Mountains were a retreat for Polish partisans. Even after the war, many resistance fighters against the communist regime stayed in the Tatras. In the middle of the 20th century, the two national parks on the Czechoslovak and Polish sides were established. For most mountaineers from Eastern Central Europe, u. a. from the GDR, the High Tatras were the only accessible high mountains during the Cold War.

On November 19, 2004, a hurricane destroyed almost half of all trees on the Slovak side of the High Tatras. The path of devastation was three kilometers wide and 50 kilometers long. The size of the destroyed area was estimated at 12,000 hectares . On December 21, 2007, border controls between Poland and Slovakia ceased to exist due to the Schengen Agreement. The border can therefore be crossed easily on the marked hiking trails. It should be noted, however, that the hiking trails in the Polish part of the High Tatras are open all year round, but in the Slovak part above the mountain huts are closed in winter from November 1st to June 15th.

topography

The High Tatras offers an alpine-like panorama with high mountain relief and isolated snow fields. The arrangement of the highest peaks on the (southern) outer edge is unusual . Although it is actually a partial mountain range , it is often referred to as the “smallest high mountain range in the world” in terms of area, but by no means in terms of height . The area of the High Tatras measures approx. 340 km² and is thus somewhat smaller than the area of the Western Tatras . The main ridge of the High Tatras is 27 km long, with the distance between the border passes as the crow flies only 16.5 km. The mountains offer an abundance of natural beauties and tourist opportunities (hikes, climbing tours, ski tours, slopes, numerous health resorts and recreational areas).

mountains

24 peaks of the High Tatras exceed the 2500 meter limit, several hundred exceed the 2000 meter limit. The crown of the Tatras is known as 75 peaks that are more than 100 m high . Most of these peaks are in the High Tatras.

The highest peaks are the Gerlachovský štít (Gerlsdorfer Peak) with 2655 m, at the same time the highest mountain in Slovakia and the entire Carpathian Mountains , the Gerlachovská veža (Gerlsdorfer Tower) with 2642 m, the Lomnický štít (Lomnitzer Peak) with 2632 m and the Ľadový štít (Eistaler peak) with 2627 m. Of the slightly lower peaks, the mighty Slavkovský štít (Schlagendorferspitze) with 2452 m and the Rysy (Meeraugspitze) consisting of three peaks are to be mentioned, the middle one just on the Slovak-Polish border, the highest with 2503 m, the north-western than second highest with 2499 m is also the highest mountain in Poland. Another mountain worth mentioning is the Kriváň (crooked horn or ox horn) depicted as an important national symbol on the Slovak cent coins , with a height of 2494 m.

The most famous peaks of the High Tatras include:

| Name of the summit | German name | Height (m) | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gerlachovský štít | Gerlsdorf tip | 2655 | Highest peak in Slovakia , the Carpathian Mountains , the Tatra Mountains and the High Tatras |

| Lomnický štít | Lomnicky tip | 2632 | Second highest peak in the Carpathian Mountains |

| Ľadový štít | Eistaler tip | 2627 | Third highest peak in the Carpathian Mountains |

| Kežmarský štít | Kesmarker tip | 2556 | |

| Rysy | Meeraugspitze | 2503 | Highest peak in Poland , highest peak of the massif of the same name |

| Kriváň | Krummhorn | 2494 | National mountain of Slovakia |

| Mięguszowiecki Szczyt | Big Mengsdorf peak | 2438 | The highest peak of the Mięguszowieckie Szczyty massif |

| Hińczowa Turnia | Hinzensee tower | 2377 | The highest peak of the Wołowy Grzbiet massif |

| Świnica | Seenalmspitze | 2301 | Highest peak of the massif of the same name |

| Kozi Wierch | Gämsenberg | 2291 | Highest peak of the massif of the same name |

| Żabi Szczyt Wyżni | Big frog tip | 2259 | The highest peak of the Żabia Grań massif |

| Zawratowa Turnia | Lower Seealmturm | 2247 | The highest peak of the Grań Kościelców massif |

| Pośredni garnet | Medium grenade tip | 2234 | Highest peak of the Granaty massif |

| Miedziane | Copper mountain | 2233 | The highest peak of the Miedziane Grań massif |

| Skrajna Sieczkowa Turnia | Front Sieczka Tower | 2220 | The highest peak of the Sieczkowe Turnie massif |

| Wielka Koszysta | Great Koszysta | 2193 | Highest peak of the Koszysta massif |

| Wielka Buczynowa Turnia | Great Buczynowa tower | 2182 | Highest peak of the Buczynowe Turnie massif |

| Zadnia Pańszczycka Czuba | Rear Pańszczyca Koppe | 2174 | The highest peak of the Grań Żółtej Turni massif |

| Szpiglasowy Wierch | Liptauer Grenzberg | 2172 | Highest peak of the Liptowskie Mury massif |

| Walentkowy Wierch | Walentkowy peak | 2156 | The highest peak of the Walentkowa Grań massif |

| Wielki Wołoszyn | Great Wołoszyn | 2155 | The highest peak of the Wołoszyn massif |

| Mnich | monk | 2068 | Popular climbing mountain on the Meerauge |

Mountain passes

Most of the mountain passes of the High Tatras lie in their main ridge and thus on the border between Poland and Slovakia. The most famous mountain passes in the main ridge of the High Tatras are from west to east:

| Name of the mountain pass | German name | Height (m) | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liliowe | Lily saddle | 1952 | Western edge of the High Tatras, marked hiking trail |

| Świnicka Przełęcz | Swinicajoch | 2051 | marked hiking trail |

| Gładka Przełęcz | Smooth pass | 1994 | marked hiking trail |

| Czarna Ławka | Czarnyjoch | 1968 | no access |

| Wrota Chałubińskiego | Chałubiński Gate | 2022 | marked hiking trail |

| Mięguszowiecka Przełęcz pod Chłopkiem | Poacher's yoke | 2307 | marked hiking trail |

| Hińczowa Przełęcz | Hinzenseescharte | 2323 | no access |

| Żabia Przełęcz | Froschseejoch | 2225 | no access |

| Waga | Hunfalvyjoch | 2337 | no access |

| Żelazne Wrota | Iron gate | 2360 | no access |

| Polski Grzebień | Polish comb | 2200 | marked hiking trail |

| Rohatka | Notch | 2288 | marked hiking trail |

| Lodowa Przełęcz | Small saddle pass | 2372 | Eastern edge of the High Tatras, marked hiking trail |

There are also some well-known passes in the side ridges of the High Tatras:

| Name of the mountain pass | German name | Height (m) | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buczynowa Przełęcz | Buchentalscharte | 2127 | Świnica ridge, Poland, no access, formerly Orla Perć |

| Zawrat | Riegelscharte | 2159 | Świnica ridge, Poland, Orla Perć via ferrata |

| Kozia Przełęcz | Kozia notch | 2135 | Świnica ridge, Poland, Orla Perć via ferrata |

| Krzyżne | Cross saddle | 2159 | Świnica ridge, Poland, Orla Perć via ferrata |

| Szpiglasowa Przełęcz | Miedzianejoch | 2110 | Miedziane ridge, Poland, marked hiking trail |

| Czerwona Ławka | Roteturmscharte | 2352 | Slovakia, marked hiking trail |

Mountain valleys

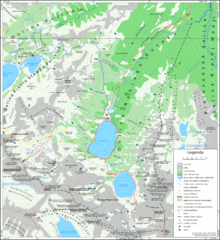

The relief map shows a view of the High Tatras from the north. So Slovakia is in the upper half of the picture and Poland in the lower. The main ridge of the High Tatras can be clearly seen, which runs in the middle from left to right and represents the national border for almost its entire length. In the foreground below the main ridge is the valley Dolina Białki , which with its side valleys from east to west: Dolina Białej Wody , Dolina Rybiego Potoku (the two large mountain lakes Czarny Staw pod Rysami and below it Morkie Oko can be clearly seen in its upper course) , Dolina Roztoki with the Dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich in its upper course (the five Polish lakes are clearly visible) and Dolina Waksmundzka occupies about 4/5 of the lower half of the picture. It is the largest valley in the High Tatras. In the lower right corner you can see the valley Dolina Suchej Wody Gąsienicowej with its side valleys Dolina Pańszczyca and Dolina Gąsienicowa with the mountain lake Wielki Staw Gąsienicowy . On the Slovak side, the Dolina Cicha Liptowska valley , which already belongs to the Western Tatras, can be seen at the top right, and the Dolina Mięguszowiecka valley with its side valleys at the top left . In the upper left corner is the largest mountain lake on the Slovak side, the Štrbské Pleso .

| Name of the mountain valley | German name | country | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dolina Białki | Bialkatal | Poland, Slovakia | north of the main ridge, the largest valley in the Tatra Mountains |

| Dolina Rybiego Potoku | Fischbachtal | Poland | Side valley of the Dolina Białki valley |

| Dolina Roztoki | Roztokatal | Poland | Side valley of the Dolina Rybiego Potoku valley |

| Dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich | Polish Five Lakes Valley | Poland | Upper course of the Dolina Roztoki valley |

| Dolina Waksmundzka | Waksmundtal | Poland | Side valley of the Dolina Rybiego Potoku valley |

| Dolina Suchej Wody Gąsienicowej | Suchatal | Poland | north of the main ridge |

| Dolina Gąsienicowa | Gąsienicowa valley | Poland | in the upper reaches of the valley Dolina Suchej Wody Gąsienicowej |

| Dolina Pańszczyca | Pańszczyca Valley | Poland | Side valley of Dolina Suchej Wody Gąsienicowej |

Waters

Flowing waters

The High Tatras lies in the catchment area of the Vistula . The northern streams drain into the Vistula via the Dunajec and the southern via the Poprad . The Dunajec has two of its three source rivers in the High Tatras, the Biały Dunajec in the west and the Białka in the east . Its third source river is the Czarny Dunajec , which rises in the Western Tatras . They unite in the Czorsztyn reservoir east of Nowy Targ to form the Dunajec.

| Name of the mountain stream | German name | River system | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Białka | Weissbach | Białka | |

| Czarnostawiański Potok | Schwarzseebach | Białka | in the upper reaches of the Rybi Potok |

| Mnichowski Potok | Mönchsbach | Białka | in the upper reaches of the Rybi Potok |

| Rybi Potok | Fischbach | Białka | western tributary of the Białka |

| Roztoka | Roztoka | Białka | western tributary of the Rybi Potok |

| Waksmundzki Potok | Waksmundbach | Białka | western tributary of the Rybi Potok |

| Czarny Potok Gąsienicowy | Schwarzbach | Biały Dunajec | in the upper reaches of the Sucha Woda Gąsienicowa |

| Pańszczycki Potok | Pańszczycki brook | Biały Dunajec | in the upper reaches of the Sucha Woda Gąsienicowa |

| Sucha Woda Gąsienicowa | Suchabach | Biały Dunajec | eastern source river of the Biały Dunajec |

Lakes

The largest of the numerous glacial lakes in the High Tatras are located below the Rysy (Meeraugspitze) on Polish territory, such as the Morskie Oko ( Meerauge , Slovak. Morské oko ), the Czarny Staw pod Rysami (Black Pond under the Meeraugspitze) and lakes in the dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich (Valley of the Five Polish Ponds). On the Slovak side are lakes such as Štrbské pleso (Štrbské Pleso) where the tourist resort of the same name is located, as the main source of Poprad applicable Veľké Hincovo pleso (Great Hincovo) or the Zelené pleso (Green Lake) to the east of the High Tatras.

| Name of the lake | German name | Height (m) | Area (ha) | maximum depth (m) | Volume (m³) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morskie Oko | Sea eye | 1393 | 34.54 | 50.8 | 9935000 |

| Wielki Staw Polski | Great Polish Lake | 1664 | 34.14 | 79.3 | 12967000 |

| Czarny Staw pod Rysami | Black lake below the Meeraugspitze | 1579 | 20.54 | 76.4 | 7761700 |

| Veľké Hincovo pleso | Great Hinzensee | 1945 | 20.08 | 53.7 | 4138700 |

| Štrbské pleso | Tschirmer See | 1346 | 19.76 | 20th | 1284000 |

| Czarny Staw Gąsienicowy | Polish Black Lake | 1624 | 17.79 | 51 | 3798000 |

| Czarny Staw Polski | Black Polish Lake | 1722 | 12.65 | 50.4 | 2825800 |

| Niżni Ciemnosmreczyński Staw | Lower Smrečin Lake | 1674 | 12.01 | 37.8 | 1500000 |

| Wyżni Żabi Staw Białczański | Upper frog lake | 1702 | 9.56 | 24.3 | |

| Przedni Staw Polski | Front Polish Lake | 1668 | 7.7 | 34.6 | 1130000 |

| Popradské pleso | Poppersee | 1494 | 6.88 | 17.6 | |

| Zadni Staw Polski | Rear Polish Lake | 1890 | 6.47 | 31.6 | 918400 |

| Wyżni Ciemnosmreczyński Staw | Upper Smrečin Lake | 1716 | 5.55 | 20th | |

| Niżni Teriański Staw | Lower Lake Terianko | 1941 | 5.47 | 47.2 | |

| Wyżni Wielki Furkotny Staw | Upper Wahlenbergsee | 2145 | 5.18 | 21st | |

| Zielony Staw Gąsienicowy | Polish Green Lake | 1672 | 3.84 | 15.1 | |

| Dwoisty Staw Gąsienicowy | Twin lake | 1657 | 2.31 | 9.2 | |

| Długi Staw Gąsienicowy | Polish Long Lake | 1783 | 1.58 | 10.6 | |

| Kurtkowiec | Jagged lake | 1686 | 1.54 | 4.8 | |

| Zadni Staw Gąsienicowy | Polish Rear Lake | 1852 | 0.52 | 8.0 | |

| Mokra Jama | Wet hole | 1500 | 0.48 | 3.0 | |

| Toporowy Staw Niżni | Lower forest lake | 1089 | 0.62 | 5.9 | |

| Czerwone Stawki Gąsienicowe | Lower and Upper Polish Little Lakes | 1695 | 0.42 | 1.4 | |

| Czerwony Staw Pańszczycki | Pańszczycatal Red Lake | 1654 | 0.30 | 0.9 | |

| Zmarzły Staw Gąsienicowy | Polish Frozen Lake | 1788 | 0.28 | 3.7 | |

| Małe Morskie Oko | Little sea eye | 1392 | 0.22 | 3.3 | |

| Mały Staw Polski | Small Polish Lake | 1668 | 0.18 | 2.1 | |

| Żabie Oko | Frog eye | 1390 | 0.11 | 2.3 | |

| Wole Oko | Ox eye | 1862 | 0.10 | 1.1 | |

| Zadni Mnichowy Stawek | Hinterer Mönchssee | 2070 | 0.04 | 1.1 | |

| Toporowy Staw Wyżni | Lower forest lake | 1120 | 0.03 | 1.1 | |

| Małe Żabie Oko | Little frog eye | 1390 | 0.02 | 2.3 |

water falls

| Name of the waterfall | German name | Brook | Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Siklawa | Siklawafall | Roztoka | 80 |

| Czarnostawiańska Siklawa | Black Sea Fall | Czarnostawiański Potok | 200 in several cascades |

| Dwoista Siklawa | Double case | Mnichowy Potok | 55 |

| Wodogrzmoty Mickiewicza | Mickiewicz cases | Roztoka | 30th |

| Buczynowa Siklawa | Buczynowafall | Buczynowy Potok | 30th |

caves

In contrast to the Western Tatras , which are made of limestone , the High Tatras consist mainly of granite and are therefore poor in karst features compared to the Western Tatras. However, there are some well-known caves in the High Tatras. On the Polish side alone, 46 caves are currently (as of February 2017) developed.

| Name of the cave | German name | Length (m) | Depth (m) | mountain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studnia w Mnichu | Well in the monk | 59.3 | 22.3 | Mnich |

| Jaskinia Wołoszyńska Niżnia | Lower Woloszyn Cave | 46.4 | 15.7 | Wołoszyn |

| Jaskinia Wołoszyńska Wyżnia | Upper Woloszyn Cave | 44 | 10.2 | Wołoszyn |

| Wielka Żabia Szpara | Big frog column | 35.8 | 26th | Siedem Granatów |

| Cubryńska Dziura I | Cubrynaloch I | 27 | 11.5 | Cubryna |

nature

flora

The flora of the High Tatras can be divided into different sections according to altitude.

- 1,200–1,250 m above sea level - there are mixed forests here

- 1,250–1,500 m above sea level - there are coniferous forests here and the spruce ( Picea abies ) dominates. The tree line runs at 1,500 m above sea level.

- 1,500–1,800 m above sea level - in the subalpine zone the mountain pine ( Pinus mugo ) dominates

- 1,800–2,300 m above sea level - grasses dominate the alpine zone

- over 2,300 m above sea level - around 120 plant species still grow in the rock zone

In the High Tatras there are about 1,300 types of plants, 700 types of moss, 1,000 types of mushrooms and 900 types of lichens. The flora of the High Tatras is similar to the flora of the Alps and other high mountains. So found in the High Tatras z. B. also the edelweiss ( Leontopodium alpinum ), the Turk's Union ( Lilium martagon ), the silver thistle ( Carlina acaulis ), clove root ( Geum montanum ), saxifrage ( Saxifraga aizoides ) and the pasque flower ( Pulsatila alpina ). Crocuses ( Crocus scepusiensis Borbás ) are less common in the valleys of the High Tatras than in the Western Tatras.

To their own species that have formed in the High Tatras, include Tatra carnations ( Dianthus nitidus ), Tatra delphiniums ( Delphinuim oxysepalum ), Tatra Occupation herbs ( Erigeron hungaricus ) Tatraschöterriche ( Erysimum wahlenbergii ), Tatra saxifrages ( Saxifraga perdurans ), Tatra Alpenglöckchen ( Soldanella carpatica ), Tatra grasses ( Cochlearia tatrae ) and Tatra grasses ( Poa nobilis ) etc. a.

fauna

The fauna in the High Tatras is similar to the fauna in the Alps and other high mountains. Due to the remote location of the High Tatras as the only high mountain range between the Alps and the Taurus, animal species have also developed that do not otherwise occur in the world. The fauna of the High Tatras can be divided into two categories: the fauna below the tree line and the fauna above the tree line.

The species that live below the tree line include: roe deer ( Capreolus capreolus ), deer ( Cervus elaphus ), fox ( Vulpes vulpes ), badger ( Meles meles ), lynx ( Lynx lynx ), wild cat ( Felis silvestris ), ermine , brown bear ( Ursus arctos ), wild boar ( Sus scrofa ), wolf ( Canis lupus ), eagle owl ( Bubo bubo ), common raven ( Corvus corax ), golden eagle ( Aquila chrysaetos ), common buzzard ( Buteo buteo ), goshawk ( Accipiter gentilis ), peregrine falcon ( Falco peregrinus ), Kestrel ( Falco tinnunculus ), Barn swallow ( Hirundo rustica ), grouse ( Tetrao urogallus ), grouse ( Lyrurus tetrix ), Mallard ( Anas platyrhynchos ), Buntspecht ( Dendrocopos major ), devil ( Cuculus canorus ), Fichtenkreuzschnabel ( Loxia curvirostra ) , ring throttle ( Turdus torquatus ), Alps Braunelle ( Prunella collaris ), grouse ( Bonasa bonasia ) Schreiadler ( Aquila pomarina ), dipper ( Cinclus cinclus ), black kite ( Milvus migrans ), Rotmilan ( Milvus milvus ) Weißstorch ( ciconi a ciconia ), Black Stork ( Ciconia nigra ), brown trout ( Salmo trutta ), bat (chiroptera), viper ( Vipera berus ), Waldeidechse ( Zootoca vivipara ), salamander ( Salam salamandra ), edible frog ( Rana esculenta ), squirrel ( Sciurus vulgaris ) , Swallowtail ( Papilio machaon ), peacock butterfly ( Inachis io ), u. a.

Among the species that are living above the tree line: Tatra marmot ( Marmota marmota latirostris ), Tatra chamois ( Rupicapra rupicapra tatrica ), snow mice ( Microtus nivialis mirhanreini ), Tatra field mice ( Microtus tatricus ), Water Pipit ( Anthus spinoletta ) Wallcreeper ( Tichodroma muraria ), common jay ( Nucifraga caryocatactes ). u. a.

natural reserve

The Tatras including the High Tatras are a UNESCO biosphere reserve. On both sides of the border there is a national park that protects the Tatras. It should be noted that the High Tatras only represent a small part of the protected areas, as the other partial mountains of the Tatras are larger than the High Tatras.

As early as 1868, the regional parliament in Galicia restricted hunting in the Tatra Mountains and placed many animal species under protection. Since the turn of the century, the Polish Tatra Society has acquired land in the Tatra Mountains from private owners in order to put it under nature protection. In the Second Polish Republic , the Treasury acquired additional land in the Tatras and the government established a nature park in the Tatras by decision of June 26, 1939. However, implementation failed with the outbreak of World War II . After the war, the remaining owners of lands in the Tatras were expropriated. The TANAP National Park was founded in what was then Czechoslovakia in 1949. After the break-up of Czechoslovakia in 1993, it lies in Slovakia. It is the oldest and largest Slovak national park. The Polish part of the Tatra Mountains has also been protected in the TPN National Park since 1954 . The TPN is the most visited of the 23 national parks in Poland. With around three million tourists a year, it is also far more visited than the larger TANAP.

The main entrance to the TPN on the Polish side is Kiry in the Western Tatras. Part of the urban area of Zakopane borders the national park. A cable car leads from the Zakopan district of Kuźnice (1010 m) to the Kasprowy Wierch (1987 m), which borders directly on the High Tatras. The cable car takes up to 360 people per hour to the Kasprowy Wierch. Other access points to the TPN in its part that belongs to the High Tatras are Bystra and Toporowa Cyrhla in Zakopane as well as Łysa Polana and various parking spaces on the Oswald-Balzer-Weg panorama trail .

The Dolina Waksmundzka valley and the Miedziane mountain are particularly strictly protected areas. They must not be entered. The Dolina Waksmundzka valley is a retreat for brown bears, wolves and lynxes. Above all, the rare flora is protected on Mount Miedziane. The former hiking trails to both areas have been abolished and are now overgrown.

On the Slovak side, the national park is threatened by a lack of control and the associated uncontrolled development of the tourist infrastructure.

climate

There are two weather stations in the Tatras. The Slovak one is on Łomnicki Szczyt, the Polish one on Kasprowy Wierch. Both weather stations can be reached by cable cars.

The climate in the High Tatras is similar to that in the Alps. The average temperature is lower than the surrounding area. During the day there are large, often rapid temperature fluctuations. The amount of precipitation, especially snowfall, is high. The snow layer remains for a long time. The sun exposure is high. There are strong winds, especially from the south and southwest.

Winter in the High Tatras lasts from October to May, at the foot of the mountain in Zakopane, however, from December to March. The coldest month is usually February and the warmest July. In winter, inversion weather conditions can occur; H. It is warmer on the peaks than in the valleys. On August 8, 2013, the highest temperature of +32.8 ° C was measured in Zakopane. However, snowfall can also occur in summer.

Strong winds, which are often hurricane, are called Halny (Polish for alpine wind, hala = alpine pasture). This is a weather phenomenon known in the Alps as the foehn . They arise when there is a high pressure area on the Polish side and a low pressure area on the Slovak side. The warm air from the south rises and pushes over the main ridge of the Tatra Mountains. On the north side, the warm air masses then fall violently on Zakopane . The halny arises mainly in spring and autumn and lasts from a few hours to several days. When it fades away, there is often heavy rain or snowfall. Particularly strong Halny appeared on March 6-7. May 1968 (288 km / h) and on November 19, 2004 and destroyed several hectares of forest on the Slovak side. Cold westerly winds are called Orawski in the High Tatras after the region west of the Tatras .

The highest recorded amount of precipitation in one day in the High Tatras is 300 mm and was measured on June 30, 1973 on the Hala Gąsienicowa mountain pasture on the Polish side. The highest measured snow depth is

- on the Polish side - Kasprowy Wierch: 355 cm in April 1996,

- on the Slovak side - Łomnica: 410 cm on March 25, 2009

In the High Tatras, the Brocken Ghost and Halo light phenomena occur regularly. In popular tradition, the Brocken ghost was seen as the announcement of a misfortune for the mountaineer.

Culture

Alpine farming

During the Middle Ages, hunters, gatherers, miners and treasure hunters came to the no man's land between Poland and Hungary, of which the High Tatras were a part. From the 13th to the 15th century, settlers from Wallachia came to southern Poland. The Wallachians were mainly shepherds and ran cattle and mountain pastures in the Beskids . From the early modern era, the valleys of the Tatras, especially the Western Tatras but also the High Tatras, were used for alpine farming. Coniferous forests and mountain pines were cleared to create pastures for cattle breeding. The alpine pastures (Polish: Hala ) were usually named either after the villages at the foot of the Tatra Mountains to which the respective mountain pasture belonged (e.g. Hala Waksmundzka after the village of Waksmund ), or after the wealthy shepherd families who owned the property acquired the alpine pastures (e.g. the Hala Gąsienicowa after the Gąsienic family). The Tatraverein started buying up the alpine pastures as early as the 19th century in order to put them under protection. The remaining landowners in the High Tatras were expropriated after World War II. Alpine farming has not been practiced in the High Tatras since the 1960s. Many alpine pastures grow over with the original vegetation. The old alpine huts and the names of the mountain meadows in the High Tatras are still traces of alpine farming.

|

buildings

The first buildings in the High Tatras were alpine huts and were built in connection with cattle breeding for shepherds and shepherds on the mountain pastures. In the 19th century, the Tatra Association acquired some alpine huts in the Tatras and converted them into mountain huts for mountaineers. In addition, buildings for religious purposes, wayside crosses and larger and smaller chapels were built in the High Tatras.

|

Góralen and Zakopane style

The architecture, art, costume, music, cuisine and literature of the Podhale region at the foot of the High Tatras is known as the Góralen culture . The Góralen are mountain people, "góra" is Polish for mountain. Since the middle of the 19th century, many Polish intellectuals, u. a. Doctors, architects, musicians, artists, writers, at the foot of the High Tatras, especially to Zakopane. They were inspired by the Góralen culture and developed their own style around the turn of the last century, which is often referred to as the Zakopane style , the Tatra style or, after the leading architect and artist of the time, the Witkiewicz style. The heyday of the Tatra style in Poland coincides with the cultural era of Young Poland , which lasted from approx. 1890 to the First World War, and represented a regional variant of the same. In 1876 the wood carving school was founded in Zakopane, which is dedicated to preservation and the development of regional wood carving of the Góralen. Popular motifs in Goral culture were religious works, in particular the “Mourning Jesus” and the “Pieta”. Landscape painting in the High Tatras began to develop in the early 19th century, but reached its peak in the time of Young Poland. Known landscape painter, who engaged in the High Tatras, were: January Nepomucen Głowacki , Peter Michal Bohúň , Walery Eljasz-Radzikowski , Ludwig de Laveaux , Stanislaw Witkiewicz , Tadeusz Popiel , Kazimierz Alchimowicz , Alfred Schouppe , Wojciech Gerson , Edward Theodore Compton , Władysław Ślewiński , Csontváry Kosztka Tivadar , Leon Wyczółkowski , Stanisław Witkacy , Władysław Skoczylas and Stefan Filipkiewicz .

Museums

Since then, the Natural History Museum of the Tatra National Park in Zakopane district Kuźnice was closed in 2004 and converted into an institute with changing exhibitions, there are in the area of High Tatras no museum. There are numerous museums at the foot of the High Tatras, especially in Zakopane. The Tatra Museum should be mentioned here in particular , with numerous departments and a. in

- Zakopane: u. a. Villa Koliba , Villa Oksza

- Chochołów

- Łopuszna

- Czarna Góra

- Jurgów

There are several open-air museums in the regions around the High Tatras , such as the Liptov Village Museum , the Orava Museum and the Zubrzyca Górna Open-Air Museum . The village of Chochołów is considered a living open-air museum of Podhale architecture due to its very well-preserved wooden architecture.

tourism

Transport links

The Tatras, especially the High Tatras, are the best part of the Carpathian Mountains for tourism . In particular in the Polish Zakopane - as the largest city in the Tatra Mountains also known as the "capital of the Tatra Mountains" - Bukowina Tatrzańska and Białka Tatrzańska and in the Slovak towns Poprad , Štrbské Pleso , Starý Smokovec and Tatranská Lomnica (the last three are districts of the city of Vysoké Tatry ) there is a well-developed tourist infrastructure.

train

The Electric Tatra Railway connects the larger valley towns of the Slovak High Tatras. There is also a train connection between Krakow and Zakopane (via Sucha Beskidzka and Chabówka ). It is divided into two sections, line 97 in the north and line 99 in the south. Line 97 was modernized from 2014 to 2017 and a shorter connection bypassing Sucha Beskidzka station, on which the direction of travel of the train had to be changed, was put into operation on June 11, 2017. This has significantly reduced the travel time from Krakow to Zakopane. There is, however, no rail connection between Zakopane and Slovakia.

Street

Zakopane can be easily reached from Krakow on the “Zakopianka” S7 and DK47 expressways in around 1 to 1.5 hours. The Zakopianka is currently under renovation and is to be expanded to consist of two lanes in both directions from Krakow to Nowy Targ. The longest road tunnel in Poland is currently being built on the “Zakopianka” near Rabka-Zdrój . Another expressway into the High Tatras from Nowy Targ is DK49 along the Białka River . It leads to the Jurgów border crossing . The Oswald-Balzer-Weg panoramic road, laid out in 1902, runs along the northern border of the national park from Zakopane to the border crossing in Łysa Polana and on to the Morskie Oko mountain lake . However, the last section from Palenica Białczańska to Morskie Oko is closed to public transport . Horse-drawn carriages run from the parking lot at the entrance of the national park to just before the mountain hut at Morskie Oko.

Airports

There is a small international airport in Poprad . The significantly larger Krakow International Airport is located approx. 100 km north of Zakopane. A sports airfield is located in Nowy Targ , approx. 20 km north of Zakopane. It lies at 628 m, making it the highest airfield in Poland. It is run by the Nowy Targ aero club and the Skoczek parachute club. Nowy Targ City Council plans to expand the airfield into a passenger airport.

Summer sports

Hiking and mountaineering

There are strict rules for visiting the national parks on both sides of the border. Camping and parking is limited to marked camping or parking spaces. Overnight stays in the open air are only permitted on designated campsites, e.g. B. Campground below the Meerauge , or on approve mountain tours. Dogs are generally not allowed to enter the national parks. Exceptions apply to dogs that are accompanied by hikers due to a disability, e.g. B. poor eyesight, are instructed. A number of other provisions seek to ensure complete protection of flora and fauna. It is forbidden to use plants such as B. picking berries or flowers, picking mushrooms or damaging them. It is also not allowed to feed, frighten, hunt, injure, kill or catch fish. Within the respective national park, hikers are only allowed to use roads and marked paths. Strictly protected reserves such as the Dolina Waksmundzka valley may not be entered under any circumstances. Tours outside the marked trails are only permitted with the approval of the national park administration or under the guidance of a registered mountain guide. On the Slovak side, hiking trails above the mountain huts are closed in winter from November 1st to June 15th. On the Polish side, however, the hiking trails are open all year round. Here the use of the hiking trails is also significantly greater, the network of hiking trails and mountain huts is denser. From Zakopane (approx. 1000 m ) there are two options for inexperienced hikers, children and people with disabilities to easily get to the High Tatras. From the Kuźnice district for the Kasprowy Wierch cable car at approx. ( 2000 m ). There you can descend into the Dolina Gąsienicowa valley via a hiking trail or climb the Zawrat mountain pass along a hiking trail . The second easy route from Zakopane to the High Tatras is via the Oswald-Balzer-Weg to the Meerauge mountain lake at approx. 1400 m . You can get to Alm Palenica Białczańska by car or bus. Further to the Meerauge, you can take a horse-drawn carriage up the Dolina Rybiego Potoku valley . In summer, the Oswald-Balzer-Weg is used or committed by approx. 10,000 people per day. From the Meerauge there are numerous possibilities to climb peaks and mountain passes.

There are several refuges for hikers in the High Tatras. On the Polish side, there is a mountain hut in each of the large valleys that is open all year round. The total length of hiking trails in the Polish Tatra National Park is 275 km. The Orla Perć is the most demanding high-altitude path in the High Tatras, the Ceprostrada is the easiest , and the Lenin path is the longest .

Marked paths lead u. a. to the following peaks:

- Rysy ( 2503 m ) - highest mountain in the High Tatras, on which a hiking trail leads ▬ red marked hiking trail from the mountain lake Meerauge

- Kriváň ( 2494 m )

- Batizovský štít ( 2456 m )

- Slavkovský štít ( 2452 m )

- Volia veža ( 2355 m )

- Świnica ( 2301 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the upper cable car station on Kasprowy Wierch

- Kozi Wierch ( 2291 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Buczynowa Strażnica ( 2242 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Zadni Granat ( 2240 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Pośredni Granat ( 2234 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Mały Kozi Wierch ( 2228 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Skrajny Granat ( 2225 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass and ▬ yellow marked hiking trail from the Dolina Gąsienicowa valley

- Wielka Buczynowa Turnia ( 2183 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Zamarła Turnia ( 2179 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Orla Baszta ( 2177 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Mała Buczynowa Turnia ( 2172 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Zawrat mountain pass

- Kościelec ( 2155 m ) ▬ black marked hiking trail from Dolina Gąsienicowa valley

- Szpiglasowy Wierch ( 2172 m ) ▬ yellow-marked hiking trail from the Szpiglasowa Przełęcz mountain pass

- Kazalnica Mięguszowiecka ( 2159 m ) ▬ green marked hiking trail from the mountain lake Czarny Staw pod Rysami

- Bula pod Rysami ( 2054 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Bergsee Meerauge

- Świstowa Czuba ( 1763 m ) ▬ blue-marked hiking trail from the Meerauge mountain lakes and Wielki Staw Polski

- Gęsia Szyja ( 1489 m ) ▬ green marked hiking trail from the Rusinowa Polana mountain pasture

- Ostry Wierch Waksmundzki ( 1475 m ) ▬ green marked trail from the Alm Rusinowa Polana and ▬ red marked trail from the Zakopane area Toporowa Cyrhla

Marked paths lead u. a. on the following mountain passes:

- Mięguszowiecka Przełęcz pod Chłopkiem ( 2307 m ) ▬ green marked hiking trail from the mountain lake Czarny Staw pod Rysami

- Zawrat ( 2158 m ) ▬ blue marked hiking trail from the mountain valleys Dolina Gąsienicowa and Dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich

- Kozia Przełęcz ( 2137 m ) ▬ yellow marked hiking trail from the mountain valleys Dolina Gąsienicowa and Dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich

- Krzyżne ( 2112 m ) ▬ yellow-marked hiking trail from the mountain valleys Dolina Gąsienicowa and Dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich

- Szpiglasowa Przełęcz ( 2110 m ) ▬ yellow marked hiking trail from the mountain valleys Dolina Rybiego Potoku and Dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich

- Wrota Chałubińskiego ( 2022 m ) ▬ black marked trail from the Dolina Rybiego Potoku valley

- Karb ( 1853 m ) ▬ red marked hiking trail from the Dolina Gąsienicowa valley

Climb

Unless marked paths lead up, climbing peaks is only permitted with a mountain guide. Climbing is only allowed to "organized" climbers (members of recognized mountaineering associations such as DAV , ÖAV , SAC , CAI , CAF ) after registering with the respective national park administration / mountain rescue service. However, some nature reserves are completely closed to all alpine activities. Climbers are allowed to enter the national park away from the hiking trails, even during the closed periods, in order to climb a summit of difficulty UIAA II or higher, including all grades from the second level of difficulty UIAA, with the exception of Kopské sedlo - Jahňací štít and Veľká Svišťovka - Kežmarský štít. Any ascent below the second level of difficulty is only permitted in summer if the descent makes it necessary, or from December 21 to March 20 in both directions if it is part of winter training for extreme mountaineers or is necessary for ice climbing. Mountaineers must carry their membership card with them and show it to the National Park staff on request. In a climbing course, all participants must be supervised by an experienced mountaineer with a valid mountain guide diploma. Bivouacking in the mountains is prohibited. Organized mountaineers are allowed to use the camp in Bielovodská dolina, the camp is not for public use. More demanding tours (such as winter tours over the main ridge) must be registered with the respective national park authorities in advance. All climbers must deposit their destination and the expected time of their return at the starting point before they embark on a tour. One of the most popular climbing walls in Poland is the east face of Kazalnica Mięguszowiecka with a height of 2159 m above sea level. NN, which rises over 500 m horizontally above the table of the mountain lake Czarny Staw pod Rysami (1583 m above sea level).

water sports

Bathing and swimming is not allowed in the lakes and streams of the High Tatras in the national parks. However, it is permitted outside the national parks. White water kayaking and rafting are practiced on the rivers in the High Tatras, especially the Dunajec and Białka . The Góralen offer organized raft trips through the Dunajec Gorge below the Czorsztyn Reservoir in the Pienines , a mountain range northeast of the High Tatras. Kayak tours in the Białka breakthrough near Krempachy are also popular .

bicycle

The use of motor vehicles and bicycles outside of public roads is prohibited in the national parks. There are only a few paths suitable for cycling in the High Tatras, e.g. B. the hiking trail in the valley Dolina Suchej Wody Gąsienicowej or the panoramic road Oswald-Balzer-Weg .

Flying and jumping

Glider pilots and parachutists take off from the airfields in Poprad and Nowy Targ . Skydiving and paragliding is limited to specially designated areas. Base jumping has not yet found its way into the High Tatras.

Winter sports

On the Slovak side, skiing is only possible on marked and groomed slopes and trails. On the Polish side, the hiking trails are not closed in winter. Therefore z. B. a descent away from the slopes for skiers and snowboarders also z. B. possible from Rysy along the hiking trails. Marked hiking trails may be used, but pedestrians and snowshoe hikers have priority there. However, you have to carry your skis or snowboards up yourself first. Groomed slopes there on the Polish side in the ski Kasprowy Wierch and Nosal Ski Complex , but for the most part already in the Western Tatras lie. In the immediate vicinity of the High Tatras there are many ski areas on the Polish and Slovak sides. The mountain lakes of the High Tatras freeze over in winter. Entering the ice rinks and skating is possible if the ice layer is thick enough.

Thermal springs

The High Tatras, especially the geologically active Podhale region , is known for its thermal springs. After drilling, five thermal baths have been built around the High Tatras, four in Poland and one in Slovakia. The largest thermal bath in Europe, Terma Bukowina Tatrzańska , is located directly on the border with the Tatra National Park in the municipality of Bukowina Tatrzańska . It is also the oldest thermal bath on the Polish side of the High Tatras. There are also thermal baths in Białka Tatrzańska , Szaflary and Chochołów as well as in Bešeňová in Slovakia.

Accidents

The first known fatal falls occurred in the High Tatras in 1650 and 1771, when Adam Kaltstein and Johann Andreas Papirus died. With the development of the High Tatras in the 19th century, the number of fatal accidents increased. Probably the best-known victim of such a mountain accident was the extremely popular mountain guide Klemens Bachleda , the Tatra Scherpa, who fell to his death in 1910 during a rescue operation even after falling into a rock. According to the mountain rescue service, 892 people died on the Polish side of the Tatras alone during the hundred years of its existence, 1909 to 2009, which means an average of about 10 deaths per year or almost one death every month. 101 deaths occurred on the Orla Perć high-altitude trail , 57 on the peaks around Mięguszowiecki Szczyt , 34 on the Świnica peak and 29 on the Rysy peak . Many famous people who died in an accident in the High Tatras were buried in the Cmentarz Zasłużonych na Pęksowym Brzyzku cemetery. The most tragic accident occurred on January 28, 2003, when eight people were killed in an avalanche on the Rysy.

literature

- Andrzej Bydlon: High Tatras and Zakopane. Laumann, Dülmen 1996, ISBN 3-87466-189-X .

- Izabella Gawin, Dieter Schulze: High Tatras - Zakopane and surroundings. 3rd edition, Edition Temmen, Bremen 2006, ISBN 3-86108-434-1 .

- Anton Klipp: The High Tatras and the Carpathian Association , Carpathian Association, Karpatendeutsches Kulturwerk Slovakia, Karlsruhe 2006, ISBN 3-927020-12-5 .

- Daniel Kollár, Ján Lacika, Roman Malarz: The Slovak-Polish Tatras (= regions without borders ), Dajama, Bratislava 1998, ISBN 80-967547-5-0 .

- Stanislav Samuhel: High Tatras: 50 selected hikes in the High Tatras, the most beautiful valley and high-altitude hikes , 6th edition, Bergverlag Rother, Oberhaching / Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-7633-4049-1 .

- The High Tatras, four-language dictionary of mountain and field names, online ( Memento from January 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ In 1256 Bela IV gave the Hrnova lands "... ab utraque partie fluvii Poprad , inter indagines regni nostri et confinia Poloniae et inter montes Semina et alpes Thorholl", [w:] Codex DH VIII.

- ↑ "Turtrut has read, later can also be used next to Turtur <Turtul the akk. Turtrot, I confessed (cf. poklot: pokol) ”. Finnish-Ugric research , t. 13, 1971. p. 176.

- ↑ "oznacza góry strome i Skaliste i odpowiada ruskiemu Tołtry" [w:] "Kosmos: czasopismo Polskiego Towarzystwa Przyrodników imienia Kopernika", t. 34. s. 535; małoruska (ukraińska) "Tołtry-Toutry", [w:] Geografja ziem dawnej Polski 1921. s. 48.

- ↑ "na Oznaczenie Tatr Mickiewicz wymiennie używał nazwy Tatry i Krępak" [w:] Władysław Dynak, Jacek Kolbuszewski. Studia o Mickiewiczu . s. 79, 96.

- ↑ "Carpates mons hodie Krapak, & Krepak, vacatur & tere russiam from Hungaria diuidit" [w:] Jacob Carl Spener. Notitia Germaniae antiquae . 1717. s. 94.

- ↑ Etnografia polska , PAN. t. 5 1961. s. 54 .; Montes Tartari, per contractionem Tatri , [w:] Historia Naturalis Curiosa Regni Poloniae. Sandomiriae . 1721. s. 20 .; na Tartari "przybysze z Tartaru", z piekła rodem, [w:] Józef Staszewski. Słownik geograficzny: pochodzenie i znaczenie nazw geograficznych , s. 305. e.g. Tatry .; "Od miasta Carpis starożytnych Bastarnów" ku krajom tatarskim, [w:] Jacek Kolbuszewski. Tatry i górale w literaturze polskiej: antologia . 1992.

- ↑ Prasłowiańszczyzna, Lechia-Polska , t 1959. 2 s. 238.

- ^ Tadeusz Milewski. Teoria, typologia i historia języka . 1993. s. 344.

- ^ Język polski . t. II, 1. 1914. [w:] Język polski , t. 3-4. PAU. Komisja Językowa. 1916.

- ↑ Norwid jako lingwista i filolog. [w:] Studia polonistyczne . tomy 9-12. Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza (Poznań). 1981. s. 196.

- ↑ Adam Fałowski, Bogdan Sendero. Biesiada słowiańska . 1992. s. 46.

- ^ Samuel Bogumił Linde. Słownik języka polskiego . 1808. s. 967.

- ^ "The name 'Tatras' appears in varius form in the oldest documents; a report of the bishopic of Prague in 1086 AD calls them 'Tritri' wheres Boleslav prince of Kraków in a documents marks them in 1255 as 'Tatry'. The Hungarians of the 13th and 14th century wrote 'Thorchal' or 'Tarczal', i.e. 'Tutur', 'Thurthul'. The Spiš Germans called them 'Schneegebürg' (Montes nivium). ”, [W:] Radek Roubal. Tatranské doliny . 1961. s. 10, 39, 49.

- ↑ Anton Klipp: The High Tatras and ..., p. 51f (see literature)

- ↑ Off to the Carpathian Mountains! The Slovak province and the expectations of tourism With reports by Kilian Kirchgeßner. Moderation: Simonetta Dibbern; Feb 21, 2009

- ↑ W Zakopanem upał wszech czasów ( Memento of 9 August 2017 Internet Archive ), accessed 2013-08-29

- ↑ Klimat Tatr ( Memento from December 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (dostęp: September 22, 2012).

Web links

- TPN - Polish National Park (Polish)

- Official website of the city of Zakopane (German)

- Official website of Bukowina Tatrzanska (Polish)

- Official website of the city of Vysoké Tatry (Slovak, English)

- TANAP - Slovak National Park (Slovak)

- Link catalog on the topic of High Tatras at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- A four-language dictionary on the names of places, mountain and field names in the High Tatras

- Map of the High Tatras (Hungarian)

- Transition Mountains High Tatras (Czech, English)

- Photos of road 537 and the storm damage (German)