Kestrel

| Kestrel | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kestrel, male |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Falco tinnunculus | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The kestrel ( Falco tinnunculus ) is the most common falcon in Central Europe. Many people are familiar with the kestrel, as it has also conquered cities as a habitat and can often be seen shaking flight . He was bird of the year in Germany in 2007 and bird of the year in Switzerland in 2008 .

Surname

The scientific species name ( Latin tinnunculus , "sounding" or "ringing") indicates the kestrel's call, which is reminiscent of a ti, ti, ti, ti and varies in tone and call speed depending on the situation.

The term kestrel, which is commonly used in German today, indicates that kestrels also use human structures as breeding grounds and prefer to nest in the uppermost regions. In addition to the name kestrel, there are a number of other trivial names that differ from region to region. The name Rüttelfalke (not to be confused with the similar red chalk falcon ) indicates the characteristic flight; Wall , cathedral or church falcons on the preferred nesting opportunities in human settlements. The term Taubensperber, which is also occasionally used, is, however, a misinterpretation of the prey spectrum of the kestrel. In contrast to the peregrine falcon , pigeons are seldom one of the bird species that they prey because they are too big as prey. The name Wannewehr is extinct .

Appearance

plumage

Kestrels show a pronounced sexual dimorphism in their plumage . The most noticeable distinguishing feature between male and female kestrels is the color of their heads. In males, the head is gray, while females are uniformly red-brown in color. Males also have small black and sometimes diamond-shaped spots on their red-brown back. Their upper tail-coverts as well as the back and the tail feathers - the so-called thrust - are also light gray. The butt end has a distinct black end band with a white border. The underside is light cream-colored and only very slightly brownish spotted or striped. The lower abdomen and the under wing coverts are almost white.

The adult female has dark bands across the back. In contrast to the male, the joint is brown and also shows several horizontal stripes and a clear end band. The underside is also darker than that of the male and has more pronounced spots. Young birds resemble the females in their plumage. However, their wings appear rounder and shorter than that of adult kestrels. In addition, the tips of the hand wings have lighter hems. Wax skin and eye ring, which are yellow in adult birds, are light blue to green-yellow in juvenile birds.

In both sexes, the tail is rounded because the outer tail feathers are shorter than the middle tail feathers. In adult birds, the wing tips reach the tail end. The legs are deep yellow, the claws black.

anatomy

Body size and wingspan vary greatly depending on the subspecies and individual. In the subspecies Falco tinnunculus tinnunculus , which is represented in Europe, males reach an average body length of 34.5 centimeters and females of 36 centimeters. The wingspan of the male is just under 75 centimeters on average and 76 centimeters for the larger females.

Normally fed males weigh on average around 200 grams, females are on average around 20 grams heavier. While males generally have a constant weight throughout the year, that of females fluctuates considerably: They are heaviest during the laying period, when even normally fed females can weigh more than 300 grams. The weight of the females and breeding success are positively correlated : Heavy females have larger clutches and are more successful in rearing their young.

Flight image

Kestrel shaking flight , the wings are maximally extended

The kestrel is easily recognizable during its conspicuous shaking flight . He uses this to search for prey. It remains in the air at a height of 10 to 20 meters and looks for suitable prey. The flapping of the wings is fast, the tail is usually diversified and bent down a little. Raising and precipitation take place in a largely horizontal plane and move approximately equal amounts of air. Does he have a potential prey animal, such as a vole , seen, he falls in dive towards it and attacks it, and it slows down just before the ground.

The rapid approach to its hunting area, the cross-country flight, is characterized by a fast, somewhat hasty-looking wing flap. If the wind is favorable or when approaching a prey, it can also slide.

Vocalizations

Studies have shown that eleven different sounds can be differentiated in females and over nine in males. The calls can be divided into a few basic patterns, the volume, pitch and frequency of which vary depending on the situation. Both the female and the male vary, among other things, the begging call of the young birds, which is also known as lapping . This leaning can be heard especially from females during courtship or when they beg their males for food during the breeding season.

The ti, ti, ti , which some authors also spell out as kikiki , is an excitement sound that can be heard especially when the birds are disturbed at the nest. Variants of this call also occur shortly before the male hands over the prey at the nest.

The sounds made by the kestrel can be heard on a page from lbv.de.

distribution

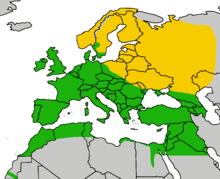

As a characteristic example of an ancient world distribution, the kestrel can be found in Europe , Asia and Africa , where it inhabits almost all climatic zones of the Palearctic , Ethiopian and Oriental regions. It is more likely to be found in the lowlands. A number of subspecies are described within this large distribution area, the number of which varies depending on the author. The following subspecies essentially follows Piechocki (1991):

- Falco tinnunculus tinnunculus Linnaeus , 1758 is the nominate form that inhabits almost the entire Palearctic . Their breeding range in Europe ranges from 68 ° N in Scandinavia and 61 ° N in Russia over the islands of the Mediterranean to North Africa . It is also common in the British Isles .

- F. t. alexandri Bourne , 1955 is from the southern Cape Verde Islands , F. t. neglectus occurs on the northern Cape Verde Islands. Both subspecies are more strongly colored than the nominate form and are characterized by a smaller wing size.

- F. t. canariensis ( Koenig, AF , 1890) lives in the western Canary Islands and is also found on Madeira . F. t. dacotiae , however, lives in the eastern Canary Islands.

- F. t. rupicolaeformis ( Brehm, CL , 1855) is found from Egypt and northern Sudan to the Arabian Peninsula .

- F. t. interstinctus McClelland , 1840 lives in Japan , Korea , China , Burma , Assam and the Himalayas .

- F. t. rufescens Swainson , 1837 inhabits the African savannas south of the Sahara as far as Ethiopia .

- F. t. archeri Hartert, E & Neumann , 1932 occurs in Somalia and on the southern coast of Kenya .

- F. t. rupicolus Daudin , 1800 is distributed from Angola in an easterly direction to Tanzania and in a southerly direction to the Cape . Today it is managed as a separate species, Falco rupicolus .

- F. t. objurgatus ( Baker, ECS , 1927) occurs in southern and western India and Sri Lanka .

The International Ornithological Committee also conducts:

- F. t. perpallidus ( Clark, AH , 1907) occurs in north-east Siberia over north-east China and Korea .

- F. t. dacotiae Hartert, E , 1913 is common in the Canary Islands .

- F. t. neglectus Schlegel , 1873 occurs in the north of the Cape Verde Islands .

Wintering areas

With the help of the bird ringing , the migration behavior of kestrels could be largely deciphered. Due to numerous ring finds you know that kestrels both stand , stroke and distinct migratory birds can be. Their migratory behavior is essentially determined by the food available to them in their respective breeding areas.

The kestrels that breed in Scandinavia or the Baltic states generally migrate to southern Europe to spend the winter there. In years when there was a vole gradation and thus the food supply was very plentiful, kestrels were observed in the southwest of Finland , which wintered there as well as the grouse and buzzards. Southern Swedish birds mostly overwinter in Poland , Germany , Belgium and northern France . Detailed studies have shown that breeding birds in central Sweden migrate to Spain and in some cases even to North Africa.

The breeding birds in Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium are predominantly standing and line birds. Only a few individuals undertake long migrations and hibernate in the regions where Scandinavian breeding birds are found. The birds that breed in North Asia and Eastern Europe migrate to the southwest, with the younger birds appearing to migrate the farthest. In addition to southern Europe, their wintering area also includes Africa , where they migrate to areas where the tropical rainforest begins. The birds that breed in the European part of Russia also use the eastern Mediterranean area for wintering.

The wintering areas of Asian populations extend from the Caspian region and southern Central Asia to Iraq and northern Iran . The northern part of the Indian Ocean is also one of them. It is also true of the Asian populations that the birds are standing and mooring birds if their habitat offers them sufficient prey even during winter.

Migratory behavior

Kestrels are so-called broad - front migrants that do not follow traditional migration routes and predominantly migrate individually. For example, almost 121,000 honey buzzards , but only 1237 kestrels, migrated across the Strait of Gibraltar among 210,000 birds of prey and falcon-like birds . This figure shows, on the one hand, that only a small part of the birds that are so common in Central Europe overwinter in Africa, and on the other hand, that they cross the Mediterranean on a broad front.

During the migration, kestrels fly relatively low and usually stay at an altitude of 45 to 100 meters. They continue their migration even in bad weather and, unlike many birds of prey, do not depend on good thermals . You will therefore also cross the Alps , which thermal-dependent birds of prey such as the buzzard rarely cross. When crossing the Alps, they mainly use passes, but they also fly over peaks and glaciers .

habitat

Typical habitats of the kestrel

The kestrel is an adaptable species that can be found in different habitats . In general, kestrels avoid both dense, closed forests and completely treeless steppes . In Central Europe, it is a common bird of the cultural landscape , which can live anywhere where there are woods or forest edges. Basically, he needs free areas with low vegetation for hunting. Where there are no trees, he uses the masts of power lines as a nesting place. There is evidence of a case from the Orkney Islands from the 1950s , where it even brooded on soil without vegetation.

In addition to the availability of nesting opportunities, it is above all the presence of prey that influences which habitats are occupied by the kestrel. If there are enough prey animals, it shows a great adaptation to different heights. In the Harz and the Ore Mountains there is a connection between the appearance of its main prey there, the field mouse , and the altitude up to which kestrels can be observed. In the Harz Mountains, it is increasingly rare to see it at altitudes above 600 meters above sea level, and it hardly occurs any more than 900 meters. In the Alps, on the other hand, where it uses a different range of prey, it can still be seen hunting in the mountain pastures at an altitude of 2000 meters. In the Caucasus he was observed at altitudes up to 3400 meters, in the Pamir also over 4000 meters. In Nepal it occurs from the lowlands up to 5000 meters, in Tibet it has been observed in high mountain areas up to 5500 meters.

Kestrel as a follower of culture

The kestrel has also conquered urban landscapes as a habitat. He benefits from the fact that hunting and breeding habitats do not have to be identical. However, falcons that breed in cities often have to fly far to hunt down mice. The kestrels that breed in the tower of the Frauenkirche in Munich cover at least three flight kilometers per mouse. Research suggests that kestrels tolerate a distance of up to five kilometers from their hunting grounds. In the case of a number of individuals breeding in the city, however, there is a change in the form of hunting and in the range of prey, which is described in more detail in the section on forms of hunting.

An example of a city populated by kestrels is Berlin . The Berlin specialist group kestrels of the Naturschutzbund Deutschland has been working with these animals in urban habitats since the late 1980s. On average, the population in Berlin fluctuates between 200 and 300 breeding pairs and collapses particularly after hard winters. The stock is supported by the installation of nesting aids in public buildings such as churches , schools or town halls . "Natural" nesting opportunities in wall niches can be found mainly on old buildings. However, these are increasingly being renovated. Modern high-rise buildings usually have too few wall holes and cavities to allow the kestrel to nest. Accordingly, around 60 percent of the birds in Berlin now breed in nesting aids that have been specifically placed for them.

The city harbors dangers for animals. Hawks regularly fall victim to car accidents or crash into windows. Young falcons can fall out of the nesting niche and are found weakened. Up to 50 animals are looked after annually in the two stations of the Berlin specialist group kestrels.

Food and subsistence

Prey animals

Kestrels living in open cultivated land feed mainly on small mammals such as voles and real mice . Kestrels living in cities also pick up small songbirds , mostly house sparrows . Which animals make up the main part of the prey depends on the local conditions. Studies on the island of Amrum have shown that kestrels prefer to hunt water voles there. Unlike in major European cities, the field mouse can make up the majority of the prey in smaller cities. The kestrel also eats lizards (with a larger proportion in southern European countries), sometimes earthworms and a significant proportion of insects such as grasshoppers and beetles as food. Breeding kestrels fall back on these prey when the small mammal populations collapse. Even young birds that have flown out first feed on insects and larger invertebrates and only switch to small mammals with increasing hunting experience.

A free-flying kestrel needs around 25% of its body weight as food every day. Investigations carried out on accident birds have shown that kestrels have an average of about two digested mice in their stomachs.

Stand hunting, jolting flight and aerial hunting

The kestrel is a so-called handle holder that grabs its prey with its fangs and kills it with a bite in the neck. The hunt is sometimes carried out as a so-called stand-up hunt, in which the falcon peeks for prey from pasture stakes, telegraph poles or branches. Typical for the kestrel is the shaking flight . This is a highly specialized form of rowing flight in which the falcon “stands” for a while over a certain place in the air. This form of flight, in which the bird flaps its wings violently, is energetically expensive. When there is a strong headwind, the kestrel has developed a behavior that saves energy. While the head remains above the fixed point, it lets its body slide backwards for fractions of a second until the neck is maximally stretched. With flaps of its wings, it then actively flies forward again until the neck is maximally curved again. The energy gain compared to continuous shaking is 44%. The vibrating flight is always carried out over those places where, due to the traces of urine that they can recognize, a particularly large number of prey animals can be assumed.

The kestrels hunt in the air only under special conditions. It occurs when kestrels living in cities can surprise flocks of songbirds, and in agricultural areas when larger groups of small birds gather there. Some city hawks appear to have switched, in large part, to bird hunting in order to survive in urban habitats. At least individual individuals regularly prey on the nestlings of feral domestic pigeons .

Occasionally young kestrels can also be seen looking for earthworms in freshly plowed fields.

Optimizing energy expenditure - the types of hunting in comparison

Stand hunting is most common in winter. In the UK , kestrels spent 85% of their hunting season in raised hide and only 15% in jogging flight in January and February. In the months from May to August, the same amount of time is spent on both types of hunting. The hide hunt is at least temporarily the less productive form of hunting; only 9% of hits on prey were successful in winter and 20% of hits in summer. In the jog hunt, on the other hand, the kestrel prey in 16% of the thrusts during winter, compared to 21% in summer. The decisive factor for changing the form of hunting, however, is the energy expenditure associated with jogging. In summer the energy expenditure of both types of hunting is the same for each mouse captured. In winter, on the other hand, the energy expenditure of hide hunting per captured mouse is only half as great as that of jogging flight, despite the lower success rate. By changing the form of hunting, the kestrel optimizes its energy expenditure.

Reproduction

Courtship

The mating flights of the kestrel can be observed in Central Europe from March to April. The males perform jerky wing flaps, turn halfway around the longitudinal axis and then glide down in rapid gliding flight. During these flights, which primarily serve to delimit the territory, an excited shouting can be heard.

The call for pairing comes mainly from the female, that settles near the male and one derived from Bettelruf boys Lahnen hear leaves. After mating, the male flies to the breeding site he has selected and lures the female with bright zig- calls. In the eyrie trough, the male shows two different courtship behaviors that merge. With loud zigzag calls, the male lays down in the eyrie trough as if it wanted to breed, scratches its fangs and deepens the brood trough. If the female appears at the beach, the male straightens up again and shows an excited bobbing up and down. Normally it offers a prey previously placed in the eyrie with its beak.

Breeding site

Common kestrels are primarily rock breeders, who prefer to breed in crevices and caves in rocky regions. Like all falcons, kestrels do not build nests. In regions with little rock, the kestrel uses the nests of other bird species such as crows . As a rule, the kestrel is too weak to drive crows away from their newly built nests, so that it usually uses previous year's and abandoned nests. Isolated cases have been described in which kestrels drove feral domestic pigeons from their nests.

Building wall niches or holes serve the Kulturfolger Kestrel as nesting; they often nest in church towers or on high-rise buildings. He uses the uppermost regions of the vertical structure of buildings, where he is least exposed to hazards.

If the food supply is plentiful in a habitat, real breeding colonies can occur, similar to the red hawk . A colony from the Erdinger Moos near Munich is documented from the 1930s, where 20 pairs of rooks and 15 pairs of kestrels brooded in close proximity to one another. The kestrels used abandoned rook nests. Only the immediate nesting territory is sharply defended by the kestrel.

Raising the young

The kestrel, which already breeds in the second year of life, usually lays 3 to 6 eggs, usually from mid-April. The ocher yellowish to brown eggs are usually heavily spotted and between 3.4 and 4.4 centimeters long. The female incubates the eggs mostly alone.

The young hatch after about 27 to 29 days. In the first days hudert the female young birds almost constantly and leaves it only for the short period of time needed to take over from the male food. In the case of mice, the female feeds her offspring mainly with muscle meat, while she eats the intestines and the remaining fur herself. When the young birds have completed their second week of life, the female increasingly stops huddling. Both parent birds then independently supply the young birds with food. At this age, young birds also begin to make their first attempts to stand. At the end of the third week of life, the nestlings have reached the body weight of an adult kestrel. The change from the down dress to the plumage of the young birds, on the other hand, is not completed until they are four weeks old. As with all falcons, young kestrels are hardly aggressive towards one another, so the losses from fights between the young birds are very low, especially since the parents make sure that they all get off the food when they feed the young birds. When the young birds are of advanced age, the adults usually only lay their food with the young birds, which then eat themselves. If there is a lack of food, this can lead to uneven distribution. The weakest young birds then have fewer chances of getting enough food and in bad years can still die at the breeding site.

Life expectancy

The oldest kestrels living in the wild, whose age could be proven by their ringing, reached an age of 18 years.

The probability that a young bird will survive its first year of life is around 50 percent. The death rate is high in January and February, when both adult and juvenile birds occasionally starve to death due to weather conditions that limit their hunting too much.

Duration

The population of kestrels in Central Europe was largely stable for many decades. Only after very cold winters or bad mouse years did populations suffer briefly, but these were usually quickly compensated for. There was a significant decline in stocks in large parts of Central Europe from the 1960s onwards. The greatest declines and the lowest brood density were recorded in intensively cultivated and cleared cultivated landscapes. The low of the stock was recorded in the mid to late 1980s. As a result of a series of warm and dry summers as well as measures to support the population such as the application of nest boxes and the decline in the use of pesticides, there was again a significant recovery.

For Germany, the number was estimated at 42,000 to 68,000 pairs at the beginning of the 21st century. This makes Germany the Central European country with the highest population. In Austria between 5,000 and 10,000 pairs breed, in Switzerland between 3,000 and 5,000 breeding pairs occur. There is no reliable information for the worldwide population, the IUCN gives a rough estimate of around 5 million individuals. According to the IUCN, the species is considered harmless worldwide. According to the current Red List of Germany, their population is also considered safe. The kestrel was “ Bird of the Year 2007” in Germany and Austria .

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel , Wolfgang Fiedler (eds.): The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 1: Nonpasseriformes - non-sparrow birds. Aula-Verlag Wiebelsheim, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89104-647-2 .

- Benny Génsbol, Walther Thiede: Birds of prey - All European species, identifiers, flight images, biology, distribution, endangerment, population development. BLV, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-405-16641-1 .

- Theodor Mebs : European birds of prey - biology - population conditions - population endangerment. Franckh-Kosmos, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-440-06838-2 .

- Rudolf Piechocki: The kestrel. Ziemsen, Wittenberg 1991, ISBN 3-7403-0257-7 .

Web links

- Falco tinnunculus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 31 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Falco tinnunculus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Kestrel info from the LBV

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 5.5 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (Eng.)

- Live broadcast from the water tower of the Vivantes Klinikum Berlin-Neukölln

- Feathers of the kestrel

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Germany): 2007

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Switzerland): 2008

- ↑ Call of the Kestrel

- ^ IOC World Bird List Falcons

- ↑ Riegert, J .; Dufek, A .; Fainová, D .; Mikeš, V .; Fuchs, R. (2007): Increased hunting effort buffers against vole scarcity in an urban Kestrel Falco tinnunculus population: Capsule in years with low vole abundance birds visited hunting grounds more frequently and for longer. Bird Study 54 (3), pp. 353-361

- ↑ Bednarek, W. (1996): Birds of Prey - Biology, Ecology, Determining, Protecting. Landbuch Verlag, Hanover. P. 124

- ↑ Pasi Tolonen, Erkki Korpimäki: Determinants of parental effort: a behavioral study in the Eurasian kestrel, Falco tinnunculus. In: Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 35, No. 5, 1994, pp. 355-362.

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 370

- ^ Bauer et al., S: 370

- ^ Birdlife International, http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/species/factsheet/22696362

- ↑ Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds 2016 - NABU. Retrieved June 5, 2019 .