House martin

| House martin | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

House martin ( Delichon urbicum ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Delichon urbicum | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

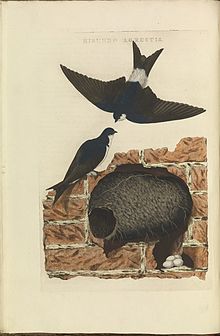

The House Martin ( Delichon urbicum , Syn. : Delichon urbica ), also city Schwalbe and Kirch Schwalbe called, is a bird art from the family of swallows (Hirundinidae). It is the fourth species of this family that occurs as a breeding bird in Central Europe , along with the bank , smoke and rock tern. It can be identified particularly well by the white rump , which no other European species of swallow shows.

The range of the house martin extends over almost all of Europe and extra-tropical Asia. Despite this large distribution area, only two subspecies are distinguished. House martins are distinct migratory birds . The Western Eurasian breeding birds usually overwinter in Africa in an area that extends from the southern border of the Sahara to the Cape Province . The East Asian breeding birds stay during the winter half-year in an area that extends from southern China via Indonesia to Assam .

description

Appearance

The house martin is about 13 centimeters long and weighs between 16 and 25 grams. It is therefore smaller and slimmer than a sparrow and belongs to the medium-sized birds within the swallow family.

In adult house martins, the head, back, top of the wings, and tail are blue-black. The entire underside of the body and the rump contrast with a pure white to powdery white color. The short legs and feet are also feathered in white. The toes and the few feathered parts of the legs are light flesh-colored. Compared with the barn swallow , the tail is less forked; there are no greatly elongated outer feathers. The eyes are brown; the beak is short and black. A sexual dimorphism does not exist.

Occasionally, house martins also have white fish whose plumage is either completely white or whose white areas are significantly more extensive than those of normally colored house martins. In the literature, among other things, individuals are described in whom only the head was normally colored and the rest of the body was feathered white or in whom only the wing bend, wing cover and hand wings were pure white on the right.

Young birds differ from adult birds in that they have a brownish to brownish-black upper surface of the body that only shines bluish-black in some places. The wings are also brownish in color and still dull. The throat and the flanks are feathered gray. The most noticeable distinguishing feature is the gray rump (pure white in adults). It looks speckled because its dark brown feathers have white tips.

The dune dress of newly hatched house martins is grayish-white in color. The fur down gives older nestlings a white woolly appearance.

Flight image and airspeed

The flight of the house martin is less rapid than that of the barn swallow, but rather flutters and is interrupted by longer gliding phases. Frequent, abrupt ascent with whirring wing beats is characteristic of their hunting flight. The wing beat frequency of the house martin is on average 5.3 beats per second, while it is somewhat slower with the barn swallow with 4.4 beats per second. Basically the house martin hunts in higher air layers than the barn swallow. Even if it occasionally flies after plowing tractors or grazing cattle to catch frightened insects, its flight altitude in the breeding area is on average 21 meters, in its wintering areas even 50 meters above the ground. Barn swallows, on the other hand, hunt most of their prey at an altitude of seven to eight meters.

House martins pursued by birds of prey can reach speeds of up to 74 kilometers per hour. Migrating house martins fly at an average speed of 43 kilometers per hour. They cover the distance between the breeding site and their hunting grounds at an average of 38 kilometers per hour.

Differentiation from other bird species

Due to their characteristic body shape and the way they fly, house martins who are less experienced in ornithology can be assigned to swallows. In the Central European breeding area, the distribution of the house martin overlaps with three other species of swallow, from which it is easy to distinguish: The sand martin, the smallest European swallow, has a plain, medium-brown upper side, a brown chest band and a weakly forked tail. The barn swallow has a metallic, shiny blue-black body surface, but, unlike the house martin, has strongly elongated outer tail feathers, a blue-black choker and a chestnut-red throat and forehead. The rock tern, which is much less common in Central Europe, is larger than the house martin and, like the sand martin, has a brown upper side. Its tail is cut straight and at the lower end of the tail feathers there are white fields like the barn swallow. The rock tern occurs regularly as a breeding bird on the northern edge of the Alps. In the African wintering area there is a possibility of confusing young birds, which are not fully colored, the house martin with the gray- backed swallow ( Pseudhirundo griseopyga ), a species of swallow restricted to Africa. In this species, however, the underside is markedly gray in color and the tail is longer and forked deeper.

voice

House martins are very vocal birds. Most often heard is a quiet, chattering chirping or lirring, which is not as varied and melodious as that of the barn swallow. A tritri or driddrli can be heard regularly in flight and when approaching the nest . The contact sound is a harsh drieer , sometimes onomatopoeic also referred to as chirrp . This call can also be heard in the wintering area. The alarm call is a high-pitched tsier or tseep .

The begging sounds made by the young house martins from an age of two to four days are striking. Young nestlings initially let out a monosyllabic tik tik tik ; in older nestlings this changes to a zittritvitvii . From around two weeks of age, the nestling's begging sounds can also be heard during the night.

distribution

The range of the two subspecies of the house martin extends over Eurasia and Africa. It is estimated at a total of 10 million square kilometers.

The nominate form Delichon urbicum urbicum , which breeds in Central Europe, has a distribution area whose northern border in Scandinavia is at about 71 degrees north and 62 degrees in western Siberia . The eastern limit of distribution runs through Mongolia and along the Yenisei River . In a southerly direction, the distribution area extends to the Mediterranean region and south-east Europe. The nominate form occurs in the Balearic Islands , Malta , Corsica , Sardinia , Sicily and Cyprus . Breeding areas are also found in north-western Africa from Morocco to northern Algeria . Occasionally there are also brooding house martins in Tunisia , Libya , Israel , in the Sahara as well as in South Africa and Namibia . Further to the east, the distribution area extends to the Crimea , the Caucasus, and continues to the north of Afghanistan . Advance breeding areas can also be found in the Pamir region , north of Kashmir , Ladakh and north of Punjab .

The wintering areas of the nominate form are for the eastern populations in northeast India. In Africa the wintering area extends from the south of the Sahara to the Cape Province.

The subspecies Delichon urbicum lagopodum breeds from the West Siberian lowlands to the central Siberian mountains and the region of the Lena and Jana rivers , the Kolyma river delta and the Chukchi peninsula . The distribution area reaches its northern limit in eastern Siberia at the 69th parallel. In a southerly direction, the distribution area extends to the Altai , northern Mongolia and northeast China. The subspecies winters in southern China and in Southeast Asia. Wintering house martins of this subspecies can be found in areas such as Indochina and Assam .

habitat

House martins are originally breeding birds that breed on vertical rock walls. There are breeding colonies in such natural places to this day. In Tibet, the house martin is even a distinct mountain bird, which uses rock, earth and loess walls up to an altitude of 4,600 meters to create its nests there. In the European distribution area, on the other hand, the species is predominantly a cultural follower that uses the open and populated cultural landscape as a habitat. House martins also settle at great heights in the European distribution area. In Austria there is a colony of house martins on the Grossglockner at an altitude of 2450 meters; In Switzerland , house martins brooded on the Furka Pass at an altitude of 2,431 meters. In Spain the altitude distribution reaches 2600 meters.

House martins depend on open areas with low vegetation. This enables them to hunt aerial plankton even when it is flying low due to rainy or stormy weather. The proximity of larger bodies of water is also necessary in order to find suitable nesting material. In the literature there are different statements as to how pronounced the cultivation behavior of the house martin is, especially in comparison to the barn swallow. High levels of air pollution can cause house martins to avoid cities in some regions. After air pollution in British cities declined in Great Britain following the passage and implementation of the Clean Air Act of 1956 , house martins began to settle again in the city center, even in cities like London .

In the wintering areas, the house martin also uses open landscapes. The house martin is less noticeable there than the barn swallows that overwinter in the same room. It flies higher and has a more nomadic way of life. In the tropical regions of the wintering area, such as in East Africa and Thailand , house martins tend to stay at higher altitudes.

Migration behavior and local loyalty

House martins are long-distance migrants who cross the Mediterranean and the Sahara on a broad front. The peak of the migration in Western and Central Europe is between late August and early October, in the southern breeding area it begins a little later. The return to the breeding areas occurs in April and May, with strong regional differences. The average arrival date for Luxembourg was April 13th; in Estonia it was May 19th. As a rule, house martins arrive around 10 days after the barn swallows. House martins generally migrate during the day. However, some birds appear to move on during the night as well.

As is characteristic of many long-distance migrants, house martins are often found as wanderers in regions that do not belong to their normal range. They have already been observed in Nepal , Alaska and Newfoundland , Greenland , Iceland , Bermuda , the Maldives and the Azores .

One of the characteristics of the house martin is a high degree of loyalty to its place of birth. Of the 4,700 nestlings flown out to 60 different Upper Swabian towns, around 450 returned as breeding birds to their place of birth in the following year. The high difference between fleeing nestlings and returnees is mainly due to losses during the migration. A number of studies suggest that male house martins settle on average less than 1.5 kilometers away from their birth nest. Females, on the other hand, are a little more enthusiastic about hiking and settle on average around 3.2 kilometers away. The return and resettlement at the “birth house” and sometimes even in the birth nest occurs: one of 165 controlled females returned to the birth nest, and seven more brood at the house where their birth nest was attached. This study also confirmed that the males were more localized. Of the 279 controlled males, eight used their birth nest for their own broods and 54 other males brooded at the birth house.

nutrition

In their feeding behavior, the house martin resembles other insectivorous birds, especially the swallows and sailors not related to this family, such as the common swift , which hunt for insects in the air. The respective food composition is determined by the offer. In a study at the Swiss Alps located Thun made flies , mosquitoes and aphids from about 80 percent of the food. Another 10 percent consisted of aquatic insects. Studies in other regions also confirm the great importance of aphids, flies and mosquitoes in the diet of the house martins. Hemiptera , beetles , butterflies and spiders are further eaten by martins arthropods .

Insects that fly past are usually hunted from below by shooting the house martins upwards with rapid wing flapping, grabbing the insect with their beak and then usually gliding back to their previous flight altitude. Unless the house martins have to feed their young, they swallow the trapped insects immediately. If they take care of nestlings, they collect the hunted insects in their throat pouch. Long-winged insects such as mayflies or larger butterflies are usually brought to the nest in their beak.

For foraging, they move up to two kilometers from the nest. On average, however, they hunt 450 meters from the nesting site.

Reproduction

The nest

House martins are colony breeders and the nests are sometimes built so close together that they touch at their base. Colonies usually consist of four to five nests. But there are also colonies that comprised thousands of nests.

House martins build their nests on vertical walls under natural or artificial overhangs, for example under rock ledges, eaves, roof edges or gate entrances. Nests outside human settlements, for example on isolated structures such as concrete bridges, are rare. If there are already existing nests, these will be preferred. The prerequisite for building a nest is that the clay used as building material adheres directly to the nest wall. If the nests are built on rocks, surfaces are chosen that are free of moss and lichen. Unlike the barn swallow, house martins only build their nests inside buildings in exceptional cases.

Both parents are involved in building the nest; the start of construction depends on the weather and altitude. The nest is built up from damp clay or clumps of earth, with the animals always building the nest wall from the inside. The house martins take up the building material on water banks, puddles or similar places. Finished nests have a closed, hemispherical shape. The entrance hole is at the top. Inside, the nest is padded with straws, feathers and similar soft material. Nest building takes 10 to 14 days.

The resulting nest is also used by other bird species as a nesting place. House sparrows regularly try to conquer the nests started by house martins. If they succeed in doing this, the house martins will begin to build their nest again in another place. In the case of finished nests, the entrance hole is so small that house sparrows are excluded. Other bird species that occupy occasionally flour swallows include blue tit , tree creepers , Redstart , Black Redstart , Great Tit , Sparrow , Tree Sparrow , Wren , Spotted Flycatcher and pigeon .

The clutch

A clutch consists of three to five pure white eggs. They are usually placed one day apart. Both parent birds breed, but the female's share of the breeding business is higher. After the first egg has been deposited, a parent bird remains in the nest, albeit with many interruptions. Firm and intensive incubation begins when the last egg is deposited. The young swallows usually hatch after 14 to 16 days. They fledge after just 22 to 32 days. Young birds that have flown out initially stay near the nest and are fed by their parents for up to a week.

A Scottish study showed that around fifteen percent of nestlings are not related to their supposed father. A mated male ensures at the beginning of the breeding period that his female spends little time alone at the nest and also accompanies it during its flights. However, this guarding of the female subsides after the first egg has been deposited. It is therefore the youngest nestlings that are more likely to have been conceived by another male.

The first brood is usually followed by a second, but the size of the clutch is somewhat smaller. Third clutches also occur in the south of the breeding area. However, late nestlings are exposed to the risk that the parent birds can no longer find enough food for them. The breeding success of the house martin is also positively correlated with the age of the parent birds . In breeding pairs in which the male was still one year old, seven chicks hatched from ten eggs. When the couple was older, nine out of ten eggs would hatch into chicks. Depending on the weather, six to eight out of ten chicks fledge.

Newly hatched house martins beg with their necks stretched out and their beak pointing straight up. Only when they are around a week old do they turn their heads purposefully towards the parent birds. To hand over the feed, the parent bird sticks its beak deep into the young bird's neck and pushes the food into its throat. Food that does not get into the throats of the young birds is ignored by them. In the case of second birds, the house martins of the first brood occasionally feed with them.

Life expectancy and causes of mortality

Out of ten adult house martins, only three to six reach the next year of life. Although individual individuals who reached an age of 10 and 14 years have been recorded, the vast majority of the house martins do not experience the fourth year of life. The average age of a house martin population is only two years.

House martins are attacked by a range of external and internal parasites . Internal parasites include flukes , tapeworms and roundworms . Feather flies , louse flies , fleas such as Ceratophyllus hirundinis , mites and blowflies are ectoparasites . The swallow bug can also be found in the nests of the house martin . In a Polish study, 29 different types of ectoparasites were found in the nests of house martins. Ectoparasites can also transmit bird malaria to house martins , among other things . Infested animals show apathy and anemia and have a restricted reproductive rate.

Adult house martins are relatively seldom struck by birds of prey . They are most likely to be attacked by birds of prey when they are sitting on the ground to pick up building materials. Sparrowhawks , hawks , black and red kites only occasionally strike house martins. The bird of prey that is most likely to prey on house martins is the tree hawk . Usually, however, the house martins are so agile in the air that they can escape pursuers. Barn owls are able to pull out the house martins, which rest in the nests at night. Individual studies have shown a proportion of house martins between four and eight percent of the birds captured by this species of owl . Also tawny owls prey occasionally during the night martins. Black woodpeckers sometimes destroy house martin nests to steal eggs and nestlings. Magpies also occasionally specialize in this form of loot acquisition. Mammals play only a subordinate role as predators of the house martin. Domestic cats sometimes specialize in hunting house martins if they only have the opportunity to collect material for nest-building in one particular place or if they have to pass low-flying spots on the way to their nests. Rats and various species of martens rob nests that they can reach and occasionally destroy entire colonies in the process.

Adverse weather conditions, especially cold and wet summers, also lead to high boy mortality. Adult house martins are particularly at risk if periods of bad weather occur during the migration. In September and October 1974, an early onset of winter in many areas of Central Europe resulted in thousands of house martins perishing from lack of food or being so weakened that they could not continue their migration. Some ornithologists assume that extreme weather fluctuations due to climate changes will occur more frequently in the future. This could also increase mortality.

Stock and protective measures

The European population is estimated at 20 to 48 million individuals, with the population being subject to strong fluctuations. The IUCN has classified the house martin in the “least concern” or “no risk” category. A number of nature conservation organizations do not share this assessment and assume that the house martin is threatened in its population in the medium term. The 2015 Red List of Germany's breeding birds lists the species in category 3 as endangered.

The house martin is one of the species that has benefited from human activities for centuries. The clearing of the forests and the establishment of human settlements went hand in hand with an increase in nesting opportunities for the house martin. As an attractive bird that feeds on flying insects, the house martin was seen as useful by humans and generally tolerated if it nested on house walls. Over the past few decades, pesticide use and changing agriculture have resulted in a decline in the species. The changes in the settlement area in particular have a negative effect on the existing building: the nests no longer stick to modern, smooth facades, and they are often carelessly or willfully destroyed during renovation work. The house martins can no longer find any building material for their nests on sealed surfaces. The house martin has been on the warning list for endangered bird species in the Federal Republic of Germany since 2002. As building breeders, house martins - as well as barn swallows , swifts and house sparrows - fall into the category of specially protected species whose nests may not be destroyed according to legal regulations (Law on Nature Conservation and Landscape Management [BNatSchG] Section 44, Paragraph 1, No. 3) .

Nature conservation organizations regularly draw attention to how easy it is to help house martins: The artificial nests available in stores are gladly accepted by house martins, provided that house martins nest in the wider area. A horizontal board underneath the nests prevents excrement from soiling the facade. Occasionally, it is recommended to fix these boards at least 50 centimeters below the nests so that nest robbers cannot reach the clutches. The creation of small clay puddles helps to provide the house martins with suitable nesting material. In addition, the erection of a swallow house as a supplement, security or replacement for a colony of buildings can be a useful aid measure.

Systematics

In 1758 Carl von Linné gave the house martins the scientific name Hirundo urbica , in 1854 the species was assigned to the genus Delichon by Thomas Horsfield and Frederic Moore . Delichon is an anagram of the ancient Greek word χελιδών ( chelīdōn ) for swallow. The species name urbicum indicates their tendency to settle in cities.

The eastern subspecies Delichon urbicum lagopodum was first described by the German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas in 1811. It differs from the western nominate form in that it has more extensive white plumage on the underside. The tail is not forked as much as in the nominate form. Other subspecies such as the Mediterranean Delichon urbicum meridionalis have been described. The characteristics that distinguish them from the other subspecies are not considered to be sufficiently clear to justify classification as a subspecies.

The genus Delichon was split off from the genus Hirundo relatively recently . The genus only includes three species, which are similar with their black-blue top and white underside. In the past it has been discussed several times whether the house martin and the Asian house martin ( D. dasypus ) do not belong to one species. The Asian house martin is native to the mountains of Central and East Asia. The house martin is also very similar to the Nepalese swallow ( D. nipalense ), which nests in the mountains of South Asia.

House martins can occasionally hybridize with barn swallows. This is actually the most common hybridization within the subordination of songbirds . This has led to the assumption that the genus Delichon may not differ genetically enough from the genus Hirundo to actually be considered an independent genus.

Others

The house martin was bird of the year 2010 in Switzerland . In Germany it was bird of the year in 1974 .

literature

- Einhard Bezzel : birds. BLV Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-405-14736-0 , p. 125.

- Heinz Menzel: The house martin. Delichon urbica. 1984 (The New Brehm Library, Volume 548)

- Angela K. Turner , Chris Rose : Swallows & Martins - An Identification Guide and Handbook. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston 1989, ISBN 0-395-51174-7 .

Web links

- Photos at www.naturlichter.de

- Building instructions for a house martin nesting box

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 1.9 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta and Gerd-Michael Heinze (English)

- House martin feathers

- Delichon urbicum inthe IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017.1. Listed by: BirdLife International, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

| This article is based in part on the article House Martin from the English Wikipedia in the version of March 9, 2008. A list of the authors can be found under Authors . |

Individual evidence

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 15 and 16

- ↑ a b Felix Liechti, Bruderer, Lukas: Wingbeat frequency of barn swallows and house martins: a comparison between free flight and wind tunnel experiments . In: The Company of Biologists (Ed.): The Journal of Experimental Biology . 205, 2002, pp. 2461-2467.

- ^ Turner, p. 166

- ↑ a b c Turner, p. 227

- ↑ Menzel, p. 11

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Angela K Turner, Rose, Chris: Swallows & Martins: an identification guide and handbook . Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Massachusetts, US 1989, ISBN 0-395-51174-7 . Pp. 226-233

- ↑ a b c d David Snow, Perrins, Christopher M (editors): The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes) . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-854099-X , pp. 1066-1069.

- ↑ a b Ian Sinclair, Hockey, Phil; Tarboton, Warwick: SASOL Birds of Southern Africa . Struik, 2002, pp. P296, ISBN 1-86872-721-1 .

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 24-25

- ^ A b BirdLife International: Species Factsheet - Northern House-martin ( Delichon urbicum ) . Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ↑ a b Menzel, p. 13

- ↑ a b Turner, p. 226

- ↑ a b Menzel, p. 33

- ↑ Menzel, p. 32

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 32-33

- ↑ Boonsong Lekagul, Round, Philip: A Guide to the Birds of Thailand . Saha Karn Baet, 1991, ISBN 974-85673-6-2 . p236

- ↑ Craig Robson: A Field Guide to the Birds of Thailand . New Holland Press, 2004, ISBN 1-84330-921-1 , p. 206.

- ↑ Oscar Gordo, Brotons, Lluís; Ferrer, Xavier; Comas, Pere: Do changes in climate patterns in wintering areas affect the timing of the spring arrival of trans-Saharan migrant birds? . In: Global Change Biology . 11, No. 1, January 2005, pp. 12-21. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2486.2004.00875.x .

- ↑ Menzel, p. 50

- ↑ a b Bezzel, p. 367

- ^ Jan Kube, Nils Kjellén, Jochen Bellebaum, Ronald Klein, Helmut Wendeln: How many diurnal migrants cross the Baltic Sea at night? ( Memento of the original from December 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Poster for the ESF conference "Migration in the life-history of birds", Institute for Bird Research, 2005.

- ^ David Sibley: The North American Bird Guide . Pica Press, 2000, p. 322, ISBN 1-873403-98-4 .

- ↑ a b c Bezzel, p. 365

- ↑ Menzel, p. 34

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 39-41

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 41-42

- ↑ Turner, p. 27

- ↑ a b c Turner, p. 228

- ^ Thomas Alfred Coward: The Birds of the British Isles and Their Eggs (two volumes) . Frederick Warne, 1930. Third edition, volume 2, pp. 252-254

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 71-72

- ↑ Helen T. Riley, Bryant, David M; Carter, Royston E; Parkin, David T .: Extra-pair fertilizations and paternity defense in house martins, Delichon urbica . In: Animal Behavior . 49, No. 2, February 1995, pp. 495-509. doi : 10.1006 / anbe.1995.0065 .

- ^ Menzel, pp. 89 and 92

- ↑ Menzel, p. 130

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 120-122

- ↑ The housemartin flea . In: Distribution of British fleas . Natural History Museum. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ↑ S. Kaczmarek: Ectoparasites from nests of swallows Delichon urbica and Hirundo rustica collected in autumn . In: Wiad Parazytol. . 39, No. 4, pp. 407-9.

- ↑ Jaime Weisman: Haemoproteus Infection in Avian Species . University of Georgia. 2007. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Alfonso Marzal, de Lope, Florentino; Navarro, Carlos; Møller, Anders Pape: Malarial parasites decrease reproductive success: an experimental study in a passerine bird Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Oecologia . 142, 2005, pp. 541-545. doi : 10.1007 / s00442-004-1757-2 .

- ↑ Birdguides: House Martin page . BirdGuides. Archived from the original on December 8, 2007. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 124-125

- ↑ Menzel, p. 125

- ↑ Menzel, pp. 126-127

- ↑ a b Bård G Stokke, Møller, Anders Pape; Sæther, Bernt-Erik; Rheinwald, Goetz; Gutscher, Hans: Weather in the breeding area and during migration affects the demography of a small long-distance passerine migrant . In: The Auk . 122, No. 2, April 2005, pp. 637-647.

- ^ A b House Martin Delichon urbicum (Linnaeus, 1758) . In: Bird facts . British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ The population status of birds in the UK: Birds of Conservation Concern: 2002-2007 . British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ House Martin . British Trust for Ornithology. Archived from the original on May 5, 2009. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ↑ Christoph Grüneberg, Hans-Günther Bauer, Heiko Haupt, Ommo Hüppop, Torsten Ryslavy, Peter Südbeck: Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds , 5 version . In: German Council for Bird Protection (Hrsg.): Reports on bird protection . tape 52 , November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Population trends . In: House Martin . Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ C Linnaeus : Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. ( Latin ). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii)., 1758, p. 192: “H. rectricibus immaculatis, dorso nîgro-caerulescente "

- ^ Delichon in the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Møller, Anders Pape; Gregersen, Jens (illustrator) (1994) Sexual Selection and the Barn Swallow . Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-854028-0 Full text

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Switzerland): 2010

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Germany): 1974