Blue tit

| Blue tit | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Blue tit ( Cyanistes caeruleus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Cyanistes caeruleus | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The Blaumeise ( cyanistes coeruleus , Syn. : Parus coeruleus ) is a bird art of the genus cyanistes from the family titmouse (Paridae). The small bird is easy to identify with its blue-yellow plumage and is very common in Central Europe. Preferred habitats are deciduous and mixed forests with a high proportion of oak ; the blue tit is also commonly found in parks and gardens. In addition to Europe, it occurs in some neighboring areas of Asia, in North Africa and on the Canary Islands . The population of the Canary Islands is often viewed as a separate species (African blue tit, Cyanistes teneriffae ).

The blue tit prefers animal food, especially insects and spiders . Outside of the reproductive period, the importance of seeds and other vegetable food increases. When it comes to food, the blue tit stands out for its dexterity, it can cling to the outermost branches and look for food hanging upside down.

Blue tits usually breed in tree hollows , and nesting boxes are also often accepted. The main competitor for breeding caves and when searching for food is the much larger great tit .

Appearance and characteristics

With a body length of just under twelve centimeters, the blue tit is significantly smaller than the great tit . The light blue plumage on the head and on the top does not occur in any other songbird in Central Europe and thus allows easy identification. The dark horn-brown beak is short and high compared to that of related species. The iris is brown, the feet are dark blue-gray, the claws gray.

Plumage and moult

In the head area, the plumage of the blue tit shows a very typical pattern, which, due to the lack of black plumage, appears less contrasting than that of the sister species . The forehead, white from the base of the beak to the front corner of the eye, merges with the characteristic light blue headstock. The feathers in the apex area can be set up to form a low, blunt hood . From the base of the beak a narrow, black eye stripe extends to the dark blue neck band, which is separated from the light blue headstock by a white stripe. The cheeks, which are also white, are bordered in front by a black throat patch and on the chest by a black and blue neck ring.

The back and shoulders are dull greenish, the hue varying between populations. The rump is gray-blue and flows smoothly into the upper tail-covers. The light blue control feathers are usually very dark on the keel and some have a white border or edge. The chest, flanks and abdomen are bright yellow, the intensity of the coloration can vary greatly from person to person. In the middle of the underside of the fuselage there is a black vertical line, which, however, can also be partially covered by the surrounding feathers. The wings are blue on top with a white wing band, the individual wing feathers are multicolored. Blue tits of a different color are extremely rare.

In addition, the plumage has a very distinctive pattern in the ultraviolet range that is invisible to the human eye . These color variations obviously play a role when choosing a partner. In the meantime, it has also been proven in many other bird species that ultraviolet light can be perceived and that the plumage of such species also has a reflection maximum in the ultraviolet range. However, it turned out to be a special feature that the blue tits show a kind of "encrypted" sexual dimorphism , because in the ultraviolet spectrum of light the sexes can be clearly distinguished in contrast to the visible range.

Young birds can be recognized by the pale yellow color in the head area until the autumn of their first calendar year, as the change of head plumage does not start until the end of the juvenile moult , which takes place from mid-July to the end of October of the hatching year. Even after the juvenile moult, they can be distinguished from the adult birds by the clear color difference between the arm that was renewed during the moult and the remaining hand covers . The new arm covers show the typical blue color, the hand covers are more greenish.

The annual moult of the adult birds is a postnuptial (“after the wedding”) full moult and begins on average six weeks before the moult of the young birds. The beginning of the moult usually falls during the rearing phase. The entire changeover takes 115 to 120 days, which is unusually long for a bird of this size. The moulting scheme is similar to that of most other passerine birds .

Sex determination

A slight gender dimorphism is present in some traits, but this does not allow all individuals to be clearly assigned. The most helpful plumage features for sex differentiation are the width and color of the collar and the color intensity of the blue head plate (see adjacent figure). In addition, the male has more white on the forehead, wing band and control feathers.

In the case of the subspecies of the teneriffae group (see systematics ), the differences between males and females are significantly smaller and the sexes can hardly be distinguished externally.

measurements and weight

On average, males are larger than females, but there is an area of overlap. There are sometimes considerable differences in size between the various subspecies, which can be seen when comparing the wing lengths . The birds from Western, Central and Northern Europe are on average larger than their Mediterranean relatives. Even within the nominate form , the wing length decreases from northeast to southwest. Towards the south-east there is again a tendency to longer wings, especially in the subspecies in the Middle East . In the nominate form, the wing length of the males is between 65 and 71 millimeters, that of the females between 62 and 67 millimeters. The average length of the tail is 51.5 millimeters in males and 49.6 millimeters in females.

On average, males are heavier than females. The weight of the blue tits is subject to strong seasonal fluctuations, it reaches its maximum in early winter, in females just before laying eggs, only at this time they are heavier than males. When there is enough food, the weight is highest in severe winters. Animals from Scandinavia weigh more than Central European ones, in Finland the average was 12.1 grams for males and 11.4 grams for females, in East Germany it was 11.5 and 11.0 grams, respectively.

voice

The blue tit's typical hunting ground begins with two to three high, very similar sounds at a frequency of around 8 kHz , which are usually transcribed as “ zizi ” or “ zizizi ”. This is followed by a trill in a slightly lower pitch, which consists of 5 to 15, in exceptional cases even up to 25 shorter elements. These stanza parts are fairly uniform compared to those of other tits. However, there is also a stanza form that can be confused with the song of the great tit . Between the introduction and the trill, a middle section consisting of a few but very variable elements is occasionally inserted. Sometimes these stanzas, consisting of two or three phrases, are strung together directly, the final series of sounds is then often shortened.

A male has three to eight different types of stanzas. Even with females, territorial singing occasionally occurs, for example when they are involved in territorial disputes. The typical trill at the end of the stanza is less common in birds in the Mediterranean region. This is obviously due to the fact that, in contrast to northern and central Europe, there is no such strong competition with the great tit. In the northern blue tits, the trill seems to be necessary to differentiate the song from the great tit, because it has been shown experimentally that great tits react to blue tit song without trills as strongly as to their own song. The territorial song of the African blue tits is still very different from the nominate form. It contains no phrased stanzas, but more variable elements. The singing deviates so much that Central European blue tits do not react to verses of the representatives from Tenerife.

Two different types of alarm calls, which can be clearly distinguished, are very important for the calls of the blue tit. The alarm for flying predators is a very high, long drawn " ii ". This alarm call is very similar to the warning call made by other songbirds in a comparable situation and is also understood across all species. Another important call of the blue tits, the so-called screeching stanza, can be heard when there is strong excitement, during territorial disputes, when approaching enemies of the soil and when hating seated birds of prey. This second alarm sound does not show such a strong interspecific agreement, but is probably also interpreted correctly by other species.

Distribution, habitat and migrations

distribution

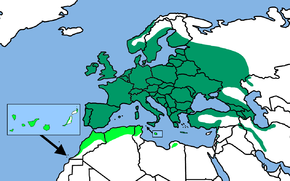

The distribution area of the blue tit is limited to two small areas in the north and south of Iran in the Western Palearctic . With the exception of the north, Europe is largely populated throughout the country. Gaps in distribution exist in the high altitudes of the Alps and probably also in some mountains in the Balkans , although in many places insufficient data are available for the latter.

The blue tit is absent from Iceland as well as the northern part of Scotland and many of the offshore islands. The Outer Hebrides were not settled until 1963. In Scandinavia , the distribution is limited to the southern parts of the country and the lowland regions , the high mountain ranges are not populated. The northern limit of the distribution area in Norway is approximately 67 ° north latitude, in Sweden the closed breeding area in the mixed forests extends to around 61 °, in the coastal area in a narrowing strip up to 65 ° north latitude. In Finland, the distribution also extends northwards to roughly the 65th parallel; in the course of the 20th century the blue tit expanded its range there significantly to the north. From southern Finland the northern border of the area stretches southeast over Bashkiria to the southern foothills of the Urals . The eastern border of the area is complex and likely to be subject to constant change. It is conceivable that there will be a mutual dependency with the border of the distribution area of the glaucous tit , which repeatedly pushes west.

In the south, the blue tit colonizes Iran, Asia Minor and northwest Africa, including the Canary Islands . In Morocco the distribution area extends south to the southern foothills of the High Atlas , in Algeria to the Sahara Atlas and in Tunisia up to the level of Sfax . In Libya there is an isolated occurrence in northwestern Cyrenaica . An attempt at naturalization in New Zealand in 1871 was unsuccessful.

habitat

Due to their wide distribution, blue tits colonize different habitats. In Central Europe, oak- rich deciduous and mixed deciduous forests achieve the highest settlement densities and breeding successes. The pure oak forests, which are very rare in Central Europe, are very attractive despite their small area. Much more common are different types of mixed oak and hornbeam forests, which also offer the species very good living conditions, as are hardwood meadows with a high proportion of oak. Beech and mixed beech forests are a bit less favorable, but they are also quite densely populated. In mixed coniferous forests, the number of blue tit territories depends heavily on the presence of individual deciduous trees. In pure coniferous forests the blue tit is absent or at most inhabits the forest edges. Mixed forests with a comparatively high proportion of hardwood are largely avoided both in the Alps from the montane altitude level and at the northern limit of the distribution area in Scandinavia. The settlement density, for which a maximum value of 1.85 breeding pairs per hectare was determined, is largely independent of the area size, which is between 0.16 and 0.84 hectares. In the case of high settlement densities, the districts are directly adjacent to one another.

In addition to the forests, the blue tit is also found in the vicinity of humans, with different habitats that are also more strongly influenced by anthropogenic populations. These include semi-open cultural landscapes with interspersed trees and hedges, orchards and green spaces. Presumably due to the competition of the great tit, the population densities in the settlement area are far lower than in the forests. The blue tit needs a higher number of old trees than the great tit, but can use irregular prey more efficiently.

In general, the blue tit is a bird of the plains, in the mountains its occurrences are largely concentrated in the valleys. The altitude limit of the distribution is much lower in isolated mountain ranges than in closed massifs: in the Harz Mountains the limit is 550 meters, in the Alps between 1,300 and 1,700 meters and in the Pyrenees around 1,800 meters, in the Caucasus at 3,500 meters. When comparing long-term observation data, there is often an upward shift in the altitude limit, which is likely to be attributable to global warming and habitat changes caused by forest death .

In the south of Europe the habitat requirements are lower. Likewise in the lower areas of the distribution area in the Middle East , where the blue tits can also be found in coniferous forests. For the most part, the habitats of the populations in North Africa differ considerably from those of Central European representatives. Montane coniferous forests, dominated by juniper , cypress and pine trees, are also populated here , as are very dry habitats such as palm oases on the northern edge of the Sahara .

The Canary Islands are another special case, as the very preferred oaks are not found there at all. There the blue tit benefits from the fact that no other tit species has colonized this Atlantic archipelago. This lack of competition is evident in behavior and in the choice of habitat, where blue tits show a clear expansion of niches. The habitats include palm groves, trees formed by tamarisk trees, montane forests of the Canary Islands pines and the evergreen laurel forests on the north side of the island. Nesting caves can also be found in the extremely arid dry bush in the south of Tenerife in the stem succulent sprouts of candelabra spurge .

Outside of the breeding season, the habitat specificity is generally significantly reduced. If favorable food sources are available, the birds are even treeless terrain like reeds reeds , grazing areas or exposed coastal cliffs on.

hikes

The blue tit is a resident or partial migrant within the distribution area , whereby the dismigration is quite pronounced, especially among young birds. Migration and migration behavior can change within a few generations. The individuals in a population also often show very different levels of willingness to move.

Loyalty to the place of birth seems to be relatively low, but it is controversial whether the extremely low catch rate of nest- ringed birds at the place of birth is due to dismigration or high mortality. The birds migrate undirected, females on average move further away from the place of birth than males. A study in Braunschweig found that over 90 percent of the birds settle less than three kilometers from the place of birth, 2.9 percent of the females and 0.7 percent of the males were found further than ten kilometers from the place of birth.

In Central, Eastern and Northern Europe there are both individuals who remain in the traditional breeding area for a long time, as well as those who show some typical characteristics of migratory birds; in Great Britain , on the other hand, the birds are consistently resident. In the other areas, the weak migration runs towards the southwest, it begins at the end of August, when the large plumage is largely moulted, and reaches its peak around the end of September. A very weak migration back home takes place between March and April. The greatest distances determined for the actual train movements are 1500 kilometers. Females take part in the migration more often, as well as predominantly younger and socially low-ranking birds.

Invasive migrations, as they regularly occur in the coal tit , are much less common and less pronounced in the blue tit. Sometimes such migrations occur several years in a row, on the other hand there can be almost 20 years between such inflows. Mild winters with subsequent above-average breeding success are assumed to be the cause.

Furthermore, there are also spatially more limited vertical hikes; the birds of the mountains can sometimes be found at significantly higher altitudes in early autumn than during the breeding season. The reason for this is probably the favorable autumn food supply in this habitat. In the middle of winter a clear valley migration can be observed, in general the blue tits can be found more frequently in the human settlement area in winter, which seems to be attractive due to artificial food sources; to what extent this is beneficial for the survival of the birds is unclear.

In southern Europe and also with all subspecies except the nominate form , the migratory behavior seems to be at least partially significantly less pronounced.

Food and subsistence

The diet of the blue tit is basically the same as that of its close relatives; In the reproductive period and especially during the rearing of young animals, animal food dominates, especially various insects and spiders . In the autumn and winter months, the importance of vegetable foods increases. The blue tit is more adept at foraging than any closely related tit, can cling to the outermost leaves and branches, often hangs upside down and uses its feet as tools in a variety of ways. The short beak is particularly suitable for hammering and splitting as well as for bringing out small objects and animals.

Food spectrum of adult birds

Throughout the year, animal nutrition accounts for around 80 percent of total nutrition. Very small prey animals under two millimeters in length predominate. In addition to butterflies and their developmental stages, hemipterans - especially aphids - are important prey all year round. Furthermore, various representatives of the hymenoptera and beetles are very regularly found in food samples . For a short period in late winter, larvae of flies and mosquitoes also play an important role. In addition to insects, spiders are also regularly eaten.

In beech forests, the beech nuts, which are abundant in some years, play the main role in plant food and can have a decisive influence on winter mortality. Otherwise, other seeds such as acorns and sweet chestnuts are used, as well as seeds from various deciduous and coniferous trees and some herbaceous plants. In autumn, various berries and types of fruit contribute to reaching the maximum weight by early winter. In spring, the birds often eat leaf and flower buds, prefer pollen and nectar , and in some plants the blue tits are even a possible pollinator, such as the imperial crown . The frequent visits to maple blossoms in late spring should serve the first stages of the numerous caterpillars of various sawfly . It has repeatedly been observed that blue tits lick tree sap leaking from woodpeckers at break points and on ringed trees .

In addition, blue tits regularly feed on artificial feeding places, especially in the winter months. If available, these are also used in the breeding season. The opening of milk bottles, which was observed in England in the late 1940s and 1950s, attracted particular interest. The birds had learned to open the tinfoil closures of the bottles that were common there at the time. Today, this is considered a real behavioral tradition and is probably derived from the unwrapping of larvae in leaves. The rapid spread of this ability among the conspecifics there is due to the fact that blue tits can learn through observation.

The food spectrum correlates closely with the seasonal and random fluctuations in the food supply. The energy requirement of adult blue tits depends on the ambient temperature. In winter, tests in open aviaries found a winter daily requirement of 45.2 kJ ; under field conditions, the energy consumption is likely to be higher. The highest energy consumption occurs in egg-producing and breeding females.

Nestling food

The food fed to the nestlings is far less variable than that of the adult birds. Butterflies and especially their caterpillars form the main component. Depending on the habitat and availability of these insects, the proportion varies between 45 and 91 percent. If this food is scarce, spiders, hymenoptera and beetles play an important role. In habitats that are heavily influenced by humans, up to 15 percent of artificial food is used for rearing. However, not only suitable food, but also components that are harmful due to the lack of proteins and vitamins , such as bread and French fries, are fed by the adult birds.

Habitat choice

For the foraging for food, the oak plays an important role among the woody plants all year round, other deciduous trees such as elms and maples are subject to greater seasonal fluctuations in their importance. The interspecific influence on the choice of habitat was intensively investigated in the case of the blue tit, since several other bird species occur syntopically in the deciduous trees, i.e. they can be found in the same biotope and have a similar diet. The low body mass determines the ecological niche of the blue tit, because it prefers thin branches and twigs, even high up in the tree. The preference for this microhabitat is likely to have arisen in the course of the joint evolution with its competitors, but the physical adaptation has now progressed so far that direct competition is no longer absolutely necessary to maintain this niche. The blue tit occupies a similar ecological niche in the deciduous trees as the coal tit and golden grouse in the coniferous trees and thus seems to be exposed to a higher risk of being prey by birds of prey . In general, the species-specific niche is more pronounced in the summer than in winter.

In an experiment it was shown that even inexperienced blue tits, raised by hand, prefer deciduous trees to conifers, so the behavior seems to be innate. In more recent studies with young tits that showed an incorrect imprint on an atypical habitat, however, it was shown that experience-related components also played an important role in the choice of habitat. This also explains why blue tits can occasionally be found in mixed forests, searching intensively for prey in conifers.

The choice of habitat differs for those blue tits that can be found in habitats other than those found in Central and Western Europe. In research, the representatives of the Canary Islands have received special attention. It has been shown that the birds from Tenerife show anatomical adaptations, especially of the feet, which are well adapted to foraging in conifers - for example a longer leg .

Reproduction

The breeding biology is the best studied aspect of the generally very well researched species. It should be noted that mostly nesting box breeding populations were studied. It is controversial to what extent data obtained in this way can be transferred to birds that breed in natural caves. While some of the findings obtained in this way are certainly independent of the type of breeding cave, the breeding success in the nesting boxes is likely to be higher than that in the natural caves.

Courtship and pairing

Like most small birds, blue tits reach sexual maturity before they are even one year old. On the one hand it is reported that females from late broods lay their first eggs at the age of ten months, on the other hand, at least in some study areas, around 30 percent of the annuals do not breed.

As early as mid-January, when the mixed winter swarms dissolve, territorial behavior begins, and some males are already displacing potential competitors from the vicinity of a female they are accompanying. The male's territory chant, which was already beginning at this time, is aimed not only at competitors, but also at the female partner. Some of the females, which are generally the more active when it comes to mate selection, are still unmated until March, but still choose a mate until the actual start of breeding. Due to the common defense of the breeding area, in which the female occasionally singing territory can be heard, the intensity of the pair bond increases.

The subsequent conspicuous ritual of “showing the cave” serves to further strengthen the bond between couples and sexual stimulation. It probably has no practical significance, as the female has also been in the area for a long time and knows the breeding caves as well. The situation is presumably different with courtship feeding that occurs in a later phase, the intensity of which can sometimes be very high. It can be assumed that this not only serves to bond with a couple and overcome individual distance, but also has great energetic significance for the female, since the energy requirement at the time of egg formation is the highest in its life cycle.

During the copulations that begin a few days before the first egg is laid, the partners gradually approach each other with trembling wings. The posture is not unlike that of a threatening blue tit, body and tail are horizontal, the hand wings are slightly spread. Presumably to appease, the birds let soft contact sounds be heard. For the actual copulation, the male flies on the back of the female and lingers there for a few seconds without holding onto the neck. After the separation, the female puffs up and performs cleaning movements, the male can utter a short stanza of the territorial song. The copulations can be repeated several times, whereby the ritualized approach is omitted. Further copulations take place during oviposition and also during early incubation.

After the original assumption of seasonal monogamy in most species of titmouse , a genetic examination showed that 20 percent of the males were polygynous and 35 percent of the females lived in such partnerships. In addition, copulations outside of the partnership also occurred. Despite the guarding of the female by the territory-keeping male, around 6 percent of the nestlings were mated with a partner other than the territory-keeping partner. In no case did all the nestlings of a brood come from a strange partner.

Nest location and nest building

Blue tits - like all tits - build relatively complex nests compared to other cave breeders , invest considerable time in building the nest and are not satisfied with cleaning or padding. The blue tits are quite flexible in their choice of cave, but almost exclusively use existing caves; only in very rare cases are putrefactive caves expanded. In addition to this type of cave, which is mainly used, woodpecker caves are also adopted unchanged. A preference for certain tree species has not been proven, although this is often shown in the literature, but in previous studies on this topic, the distribution of the selected caves has not been sufficiently compared with the offer of a certain habitat.

A typical blue tit den is higher up the tree, has a smaller entrance opening and a shallower internal depth than those of other tits. This is attributed to interspecific competition, especially the great tit . However, there is an overlap area between the species in the breeding caves used, even with "non-titmouse" such as pied flycatcher , nuthatch , starling or tree sparrow . Nests in holes in the ground are very rare, and there have also been individual reports of the construction or use of free-standing nests of other species.

In habitats that are heavily influenced by humans, many blue tits breed in artificial nesting aids . The preference for nest boxes is similar to that for natural caves; those with an entrance opening of 26 to 28 millimeters in diameter are preferred, which exclude the main competitor great tit. Not as common as great tits, but nonetheless regularly, blue tits also use unusual places in settlement areas for breeding, for example crevices in the masonry or post boxes standing in the open.

The female alone building the nest begins with the outer layer, for which mainly moss , but also characteristic bitten and kinked blades of grass are used. If the brood cavity is larger, the time required for this phase increases. On average, from the third day onwards, the female begins to put in upholstery fabrics. Animal hair and feathers are mainly used here. The time it takes to build a nest varies and is primarily influenced by the current weather. The total construction time can be between 2 days for a replacement brood and 14 days.

A distinction is made between various techniques for the construction activity itself. In the first phase, the so-called "cremation" predominates, in which the female sitting in the hollow sticks the entered nesting material with rapid lateral beak rashes between already existing nest components and shakes it into it. In the subsequent fine-tuning of the nest, a distinction is made between three techniques: "kicking", "stuffing" and "plucking". When "kicking" the female tries to move all nesting material out of the hollow to the side with the appropriate movements. During the later “stuffing”, nesting material is grasped with the beak and then stuffed in another place with long, sweeping, slow movements, whereby the material begins to become matted. During the laying and incubation phase, "plucking" occurs, which in the blue tit only differs from "stuffing" in that the material is fetched from further away and less moved back and forth. For the actual nest building, the "plucking" is probably of little importance, rather it is a forerunner of the sequence of movements with which the eggs are later covered before leaving the nest cavity.

Clutch

The eggs of the blue tit are very similar to those of other small tits and can hardly be distinguished from them visually. They have a white basic color and a spindle shape typical for titmice, as well as a smooth, slightly shiny surface. Furthermore, they show a non-uniform pattern of light or darker reddish to brown spots and blobs, which are often concentrated at the obtuse pole.

The egg size seems to depend to a considerable extent on the respective female and is genetically determined. The length is between 14 and 18, the width between 10.7 and 13.5 millimeters. The geographic variation is quite small. In contrast to the great tit, the egg size does not increase with height, but rather decreases, which is probably due to the lower adaptation of the blue tit to montane habitats. The weight of the eggs of the nominate form varies between 0.87 and 1.16 grams, the weight of the entire clutch can be 1.5 times the weight of the female.

Laying begins in Central Europe in mid-April, the most important timer is the length of the day, and environmental factors and above all the temperature play a role. Recent studies indicate that the onset of laying has become significantly premature over the past few decades. This statement is based on the comparative data collected in a somewhat standardized manner since the 1950s. Blue tits are therefore good bio-indicators , and their changed behavior reflects global warming .

The mean clutch size is between 6 and 12 eggs, in extreme cases up to 17 eggs were counted; this represents a maximum value for the first brood in the tit species of the western palearctic . The habitat seems to be the decisive factor for the clutch size, which is due to the different availability of prey. The highest egg numbers are found in deciduous oak forests, smaller clutch sizes occur in coniferous forests and evergreen deciduous forests. The smallest clutch sizes were found in Central Europe in gardens, parks and other biotopes in the settlement area. This is mainly attributed to the high proportion of foreign woody plants and the resulting poverty of insects. In addition to the dependence on the habitat, the clutch size is also related to the geographical latitude; in comparable habitats, the clutches are larger in the north than in the south. The Canarian blue tits represent a special case that goes well beyond this north-south divide. The mean clutch size of them is less than 4 eggs.

In most habitats, second broods only occur in exceptional cases, the frequency is usually well below 10 percent. Replacement broods are also comparatively rare. An increased occurrence of second and replacement broods only occurs in certain habitats and in special weather-related constellations. This is a clear difference to the coal tit , which is comparable in size ; In this case, the clutch size of the first brood is smaller, but second broods occur much more frequently. The fact that the first brood represents a considerable amount of energy expenditure for the female blue tit is also shown by the fact that interruptions in oviposition occur very frequently at 37 percent, which is a maximum value for cave breeders.

Incubation and hatching

As with the other related tit species, in the blue tit only the female incubates the clutch, the male defends the territory and continues the courtship feeding. The brood usually begins after the last egg is laid and lasts between 12 and 17 days, with the extreme values only being observed in isolated cases. The incubation of larger clutches takes a little more time.

On the last days of incubation, the mean residence time on the eggs was determined to be 26 minutes, which alternated with an average of ten minutes outside the brood cavity. At low temperatures, the breeding intervals lengthen in favor of staying on the eggs.

In the case of blue tits, the asynchronous hatching typical of songbird species with large clutches is particularly pronounced. As a rule, the hatching takes two to three days, only in rare cases do the young hatch on the same day. Among other things, this is attributed to the fact that the female, which already sleeps in the cave before the actual brood begins, warms up the relatively small volume of air in the cave.

David Lack already suspected in 1954 that asynchronous hatching serves not only to regulate the clutch size but also to regulate the number of offspring according to the current feeding conditions. In this behavior, known as “non-aggressive brood reduction”, the significantly smaller nestlings are no longer fed in situations of lack of food, which increases the chances of survival of the remaining young. This assumption was largely confirmed experimentally in the case of the blue tit.

In the literature it is stated that 82 to 92 percent of eggs hatch young. The lowest hatching rates were found in urban habitats. However, more recent studies indicate that the hatching rate was negatively influenced by the earlier studies itself and that the actual hatching rate is higher. The cause can be minimal damage to the eggs, which occurs when the egg size is measured and which can lead to the egg drying out. On the other hand, it has been proven that disturbances in the nesting area lead to lower hatching rates.

Development of the young birds

The information for the nestling period is between 16 and 22 days. In the initial phase the females are predominantly the Hudern busy, and the males make the most of the Fütterarbeit, the food often fed by the male itself, but is passed to the waiting female. From around the 8th nestling day, the proportion of feedings between males and females is evenly distributed. However, this does not apply to polygynously mated males; their share in this phase is only 20 to 30 percent. In the cases observed, it was found that the broods of such males were staggered in time so that the initial phases of the nestling times did not overlap.

The feeding frequency is at its maximum between the 11th and 15th day, then drops slightly and remains at a slightly lower level until the animal leaves. Short-term changes in the food requirements of the young birds are not only regulated by the feeding frequency, but also by the choice of different prey; Since blue tits hardly bundle even smaller prey, the increased need for food is also satisfied by choosing larger animals.

The weight gain of the nestlings is most pronounced between the 5th and 12th nestling day. Shortly before leaving, they almost reach the weight of adult birds. A comparison of the weight development of the blue tit with sympathetic coal tits shows that the weight differences of the blue tit nestlings of a brood increase over time instead of decreasing as in the coal tit, and the weight of the nestlings of the coal tit can exceed that of adult birds.

In contrast to weight gain, plumage development is largely independent of the effects of the environment. The first breakthrough keels are those of the hand and arm swing , around the 5th day. The development of the head plumage takes the longest. A large part of the springs is already developed before the flight, the wings and control springs continue to grow afterwards.

Older nestlings often climb the cave wall to the entrance opening and receive the food there. In doing so, they already get to know the immediate surroundings of the cave, which is likely to be important for their future habitat selection, for example. The flight does not appear to be tied to a specific time of day, but a tendency towards the hours of the morning was observed. The young birds usually fly out in quick succession, in the direction of the nearby, dense vegetation. The young birds continue to be fed outside the breeding cave. It is assumed that the mortality in the first phase of life is very high, but such studies are difficult because the independent young birds usually migrate from the immediate breeding site.

Breeding success

Weather conditions have the greatest influence on breeding success; It is noteworthy that in addition to the onset of winter, above-average temperatures also result in reduced breeding success. This is due to the fact that in such weather the development of the most important prey animals is significantly accelerated and the timing of the breeding process is disturbed, which the blue tits can no longer influence from the time they lay their eggs.

The relative breeding success, the proportion of fledgling young birds based on the clutch size, is greatest in oak forests, where it is over 80 percent. It is lowest in pure coniferous and evergreen deciduous forests , while 31 percent was determined in a spruce forest in southern Germany. The habitat has an even more pronounced effect on the differences in the absolute breeding success, since the clutch size also shows a connection with the habitat quality. The number of young birds that a single blue tit makes to fly in the course of its life varies greatly from person to person. In a detailed study in Belgium , a few very successful blue tits made 40 or more nestlings fly out. Most of the hatchlings, however, never breed successfully on their own; it is estimated that 35 percent of successful breeders do not produce grandchildren.

Other behavior

Blue tits start the day earlier than great tits and stay active longer in the evening. Both in the breeding season and in winter, blue tits spend a large part of their time foraging, in midwinter it is about 85 percent of the active time.

Calm and comfort behavior

As a rule, blue tits spend the night individually, from late summer to spring in tree hollows, other niches and nesting boxes. In summer, people will probably also spend the night on branches outside. When it comes to sleeping places, the main competitor is the great tit, as it is when searching for food. The amount of time spent on plumage care is estimated at 6 percent of the total activity. Blue tits bathe frequently and intensively; in addition to water baths, bathing in snow can also be observed.

Move

Blue tits usually only fly short distances, between trees or from branch to branch. When flying over longer distances, avoid flying over open spaces if possible, the flight is curved and relatively slow. With its short, strong toes, the blue tit can cling to branches and leaves much better than any other species of tit.

Social and antagonistic behavior

After the breeding season, couple and family associations gradually break up. In autumn and winter, blue tits join larger, mostly mixed troops, which can include nuthatches , tree creepers or golden cockerels in addition to other tits . Interspecific disputes can occur at cheap food sources, especially at feeding places, and the blue tit is often dominant even over larger birds - in contrast to the dispute about nesting caves.

In general, blue tits have a very high potential for aggression in relation to their size. There is a pronounced hierarchy within the blue tits, in which individual males dominate. The rank positions are recognized instantly by conspecifics. Birds resident in a territory dominate over immigrants and migrants.

Causes of Loss and Life Expectancy

In addition to nestling mortality, the high mortality rate in the first year of life is particularly important. Only about a quarter of the fledglings breed in the following year.

Predator

Despite the comparatively protected brood in caves, predation plays a not inconsiderable role in the nestlings; in natural caves the losses are significantly higher than in nesting boxes. Among the mammals, species from the marten family are particularly important, especially weasels ( Mustela spp.) Can have a significant local influence. In birds is Buntspecht the most important nest enemy. He expands the entry hole or otherwise hacks an access to the potential breeding cave and searches it specifically for eggs and young birds. It also happens that blocking young birds are pulled out through the entrance hole.

The main enemy of adult blue tits is the sparrowhawk . The proportion of breeding birds he has shot can be up to 17 percent, but varies between different observation years. Despite this clearly noticeable influence on the breeding success, the importance for the population dynamics of the blue tits seems to be rather minor overall. In their behavior, blue tits show clear adaptations to their main enemy, for example the warning call is barely audible for the sparrowhawk due to the high frequency and is extremely difficult to locate. In addition to the sparrowhawk, other birds of prey can occasionally prey on blue tits, such as the kestrel in urban habitats. The threat posed by mammals is significantly lower for adult blue tits than for nestlings, but especially breeding females are repeatedly preyed on by nest predators.

Other causes of loss

The weather plays an important role in nestling mortality, but adult birds survive periods of bad weather quite well during the breeding season. In the winter half-year, however, in addition to the availability of food, the weather plays a significant role in mortality, as the energy requirements of the small birds rise sharply with falling temperatures. There is no reliable evidence for the influence of diseases and parasites on the mortality of blue tits.

Blue tits in Germany have been affected by an apparently contagious disease since March 2020. The first cases were observed in Rheinhessen , meanwhile there are reports from an area between the Westerwald in Rhineland-Palatinate through Central Hesse to western Thuringia . The affected birds look apathetic and fluffy, their eyes sticky. Sometimes great tits and other small songbirds are also affected. Some symptoms suggest a bacterial infection that has caused pneumonia in tit species in the past, particularly in the UK. This bird epidemic was first described extensively in England and Wales in 1996, and something similar occurred in North Rhine-Westphalia in March 2018. For the further recording and evaluation of this newer phenomenon and its spread, the NABU asked for such observations to be reported. NABU was able to gain more information about the spread of the disease through the Garden Birds Hour in 2020, when the blue tit was the focus and more people than ever before. Dead birds could also be sent to the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine or the responsible district veterinary office for examination after prior consultation and taking the relevant safety measures into account . At the end of April 2020, the bacterium Suttonella ornithocola was identified as the cause. The affected animals die from pneumonia. According to the authorities, however, the bacterium is harmless to humans and pets.

Life expectancy

Few blue tits live to be more than two years old. A critical phase of life with increased mortality occurs again in Central Europe from the age of seven, so that older birds are a rarity there. In an intensively studied population near Braunschweig , the oldest individuals were a little over 8 years old. In the British Isles, blue tits are older, presumably due to lower winter mortality; the two “record holders” there were 11.4 and 12.3 years old.

Inventory and inventory development

| country | Number of breeding pairs | year |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | 2,600,000-3,300,000 | 2008 |

| Austria | 200,000-500,000 | 1993 |

| Switzerland | 150,000-250,000 | 1998 |

Large-scale population data are difficult to determine for the blue tit, as for all other small birds. An estimate from 1997 assumed 16 to 21 million breeding pairs in Europe. No reliable information is available for other parts of the distribution area - such as North Africa. The table on the right shows the population estimates for some selected countries in Central Europe.

Since the 20th century it seems as if the positive and negative influences of humans on the habitat of the blue tits in Central Europe are more or less canceled out. The most striking change in the past century was the expansion of the area in Scandinavia, where the stock in Finland, for example, has increased sixfold since the 1950s. Blue tit populations fluctuate more than those of the great tit and appear to have an average cycle of four years. In Central Europe, the larger sister species is more common in most habitats, in Great Britain a shift in the proportions in favor of the blue tit can be seen.

Systematics

Relationships within the tits

The traditional subdivision of the titmouse family, comprising around 50 species, was very unbalanced, because all species - with the exception of two atypical oriental species - were combined in a single genus, the genus Parus . This division has long been controversial, but every attempt at a more differentiated structure was entangled in contradictions. Morphological and behavioral differences and later also molecular biological findings suggested a division of the genus. A molecular genetic investigation carried out in 2005 into the relationship of the tits, which analyzed the mitochondrial gene sequence of the cytochrome b gene, led to the recognition of a division of the genus Parus by the British Ornithologists' Union . Such a division into the genera Cyanistes , Poecile , Periparus , Lophophanes , Baeolophus , with a remainder of about 23 species in Parus , had already been proposed in 1903 by the Austrian ornithologist Carl Eduard Hellmayr on the basis of plumage characteristics.

The blue tit and the glaze tit form the genus Cyanistes . The fact that these two species are closely related was and is undisputed. The molecular genetic investigation mentioned above also shows that these sister species were the first to split off from the remaining "former" Parus species. This is surprising insofar as the Cyanistes species and the species that have now remained in the genus Parus - especially the great tit - are therefore not directly related, but seem to be the only tit species that do not hide any food.

Subspecies

The blue tit shows great variability in a comparatively limited range. The 14 to 16 differentiated subspecies are divided into two groups, the larger of which is native to Europe and Asia and is called the caeruleus group. The other group are the blue tits of the Canary Islands and North Africa, traditionally known as the tenerife group.

It has long been discussed whether to regard the blue tits of the Canary Islands as a separate species ( Cyanistes teneriffae ). In addition to genetic differences and differences in behavior, the main argument is the strongly deviating territorial song - Central European blue tits do not react to verses of their conspecifics from Tenerife. However, it is controversial how the two North African subspecies are then to be assigned, in particular the assignment of the northwest African subspecies Cyanistes caeruleus ultramarinus is a problem, this is obviously between the Canarian and the actual Eurasian blue tit. The North African subspecies tend to be assigned to the actual blue tit. Studies published in 2007 provided a somewhat different result: According to them, Cyanistes caeruleus degener, one of the subspecies native to the Canary Islands, cannot be distinguished from the north-west African subspecies, and with Cyanistes caeruleus palmensis another Canarian subspecies is obviously closer to the actual blue tit than at the Canary Islands.

The following representation of the subspecies corresponds to the structure presented by Harrap and Quinn in 1996.

The caeruleus group

This subspecies group includes all blue tits except those in the African part of the distribution area. The group includes all typical Central European blue tits and all representatives of this group are more or less similar to the Central European form. Within the group, the main differences are in the intensity of the blue and yellow coloration of the plumage.

- Cyanistes caeruleus caeruleus ( Linnaeus , 1758): With the exception of the Iberian Peninsula, continental Europe is almost exclusively populated by the nominate form . This subspecies is also found in Asia Minor and in the northern part of the Middle East . The appearance corresponds to the description above.

- Cyanistes caeruleus obscurus ( Pražák 1894): The subspecies occurs on the British Isles and the Channel Islands , in western France it is mixed with the nominate form, which occasionally makes the status as a subspecies in connection with the small differences appear doubtful. The headstock is a little darker blue, the coat is also darker and goes more green. C. c. obscurus is on average slightly smaller than the nominate form.

- Cyanistes caeruleus balearicus ( Von Jordans 1930): The occurrence of this subspecies, which also differ only slightly, is limited to Mallorca . The plumage appears duller overall, the belly stripe is significantly reduced.

- Cyanistes caeruleus ogliastrae ( Hartert 1905): This subspecies occurs in Portugal , southern Spain , Corsica and Sardinia . In some Spanish provinces, mixed forms with the nominate form occur. C. c. ogliastrae is very similar to the British Isles breed. The coat, however, tends more towards blue or gray, the elytra are usually darker and brighter blue. The reduced sexual dimorphism is striking , the coloring of the females is sometimes just as bright as that of the males.

- Cyanistes caeruleus calamensis ( Parrot 1908): The representatives of the Peloponnese , the Cyclades , as well as Crete and Rhodes are often smaller in comparison to the nominate form, but hardly differ in their plumage from the nominate form. It seems questionable whether the status of this subspecies could stand up to critical scrutiny.

- Cyanistes caeruleus orientalis ( Zarudny & Loudon 1905): The subspecies occurs in areas near the Volga to the southern and central Urals . The main differences to the nominate form are the duller colored, more gray-yellowish upper side and the lighter yellow belly side. On average, the representatives of this breed are somewhat larger, but some authors do not consider the differences to be sufficient to separate them from the nominate form.

- Cyanistes caeruleus satunini ( Zarudny 1908): The area adjoining the distribution area of the nominate form in the southeast includes the Crimea peninsula , the Caucasus and Transcaucasia , northwestern Iran , eastern and southern Turkey and parts of Turkmenistan . The subspecies shows a gradual transition to the nominate form, there is an extensive mixed zone, only the birds of the easternmost part of the range differ significantly. On the upper side, olive and gray tones are dominant, the underside is more uniform and duller yellow.

- Cyanistes caeruleus raddei ( Zarudny 1908): This subspecies is native to a narrow strip in Northern Iran and is therefore together with C. c. persicus is the only representative outside the Palearctic region . It shows similarities with the nominate form as well as with C. c. satunini . The coat is darker and more bluish on average, the underside clearer and stronger yellow.

- Cyanistes caeruleus persicus ( Blanford 1873): These birds can be found in the Zagros Mountains of southern and southwestern Iran. At the northern edge of the distribution area there are mixed forms with C. c. raddei . Representatives of this subspecies are on average smaller than the nominate form and generally pale in color, the top is bluish green-gray, the bottom is comparatively variable.

The teneriffae group

In contrast to the caeruleus group, the subspecies of this group can be more clearly separated from one another. This is based on the fact that all six subspecies occur allopatric and therefore there are no mixed zones. What they all have in common is the comparatively darker coloration and the vocalizations that differ greatly from those of the other subspecies group. In particular, the four subspecies of this group occurring in the Canary Islands are now often viewed as a separate species, but the assignment of the two Northwest African subspecies is controversial in this classification.

- Cyanistes caeruleus ultramarinus ( Bonaparte , 1841): This subspecies is relatively widespread in northwest Africa. It also settles on the Italian Mediterranean island of Pantelleria , about 70 kilometers from the Tunisian mainland. These birds can be distinguished mainly by their slate blue top.

- Cyanistes caeruleus cyrenaicae ( Hartert , 1922): This is an isolated endemic endemic to north-western Cyrenaica in Libya. However, it is doubtful whether the deposit has always been so separated. The isolation could be due to the massive habitat changes in northern Africa. This subspecies is similar to C. c. ultramarine strong, the white band on the forehead is narrower, the coat is darker and duller blue, the yellow of the underside is darker. In addition, the birds are somewhat smaller, but have a thicker beak, which can be seen as an adaptation to foraging in juniper .

- Cyanistes caeruleus degener ( Hartert , 1901): The subspecies colonizes the desert-like islands of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura . It is reminiscent of C. c. ultramarine , but is duller and more gray on the upper side, the dark bands on the throat and neck are broader. The longer and thicker beak should also be an adaptation to the habitat here. However, recent molecular genetic studies show no difference between this subspecies and C. c. recognize ultramarinus .

- Cyanistes caeruleus teneriffae ( Lesson , 1831): These birds are not only found on Tenerife , but also on the neighboring islands of Gran Canaria and La Gomera . The back appears even darker than in C. c. degener , the underside is dark yellow and the black belly stripe is almost completely absent. As with the following subspecies, the beak is quite fine and is interpreted as an adaptation for foraging on Canary Islands pines .

- Cyanistes caeruleus palmensis ( Meade-Waldo , 1889): In this endemic to the island of La Palma , the headstock is very darkly colored, more black than blue. The mantle and cover feathers are dull and grayish.

- Cyanistes caeruleus ombriosus ( Meade-Waldo , 1890): This subspecies is endemic to the island of El Hierro and is similar to C. c. tenerife . The top tends to be more green, the bottom is more yellow.

The island blue tits of the Canaries are an excellent example of radiation under the isolated conditions of an oceanic archipelago , although their diversity does not quite match that of the island genera and families - such as the Darwin's finches .

Blue tit and human

In general, the blue tit is considered a cute little bird; its notoriety is very high because it is often close to people and it is also very easy to identify.

Etymology and naming

Both the German common name and the scientific name indicate the basic color of the plumage, "caeruleus" is the Latin word for "blue". Local German and foreign names also often contain this color name, for example “Blue tit” in English and “Mésange bleue” in French. In some languages the name goes back to the voice of the bird, for example in Italian, where the blue tit is called "Cinciarella". The Dutch name “Pimpelmees”, on the other hand, refers to their behavior of hanging down from the tips of branches when foraging. The way in which food is processed with the beak is reflected in Spanish, where the blue tit is called "Herrerillo común", "Herrerillo" is the diminutive of "Herrero", in English "blacksmith".

Arts and Culture

The blue tit can be found in early book printing , but mostly it is only part of the floral decorations in book illuminations . A famous example is the Koberger Bible, which was written in the 15th century. In the book of Genesis , a blue tit can be seen in the tendrils at the bottom.

Postage stamp in the GDR

|

The blue tit is also regularly featured in poems; Wilhelm Busch , for example, describes its foraging:

She whistles brightly and climbs cheerfully

on the bush upside down and upside down.

She doesn't disdain the hardest grain, she pounds

until the shell breaks.

The contemporary Berlin artist Wolfgang Müller dedicates a good part of his work to the blue tit , including the Blue Tit exhibition organized together with Nan Goldin .

The arts and crafts take on the blue tit in different ways, for example in the form of porcelain figures, decorative plates and jewelry. Due to the bird's attractive appearance, it is used again and again as an adornment for everyday objects. The representations on numerous postage stamps are a special case, some of which go into great detail and even depict subspecies.

Research history

More than 400 years ago, Conrad Gessner described the blue tit in his Historia animalium and distinguished it from other species - in particular from the tail tit . In 1853 the first issue of the Journal of Ornithology was devoted to the blue tit with a contribution to its oology . Since then, the most diverse questions of the biology of the blue tit have been extensively investigated, with a special focus on the interrelationships between clutch size, habitat and other environmental factors as well as questions of population dynamics . This problem area gave rise to further questions about reproduction, reproductive success and thus parental fitness. In recent times, the Mediterranean region in particular has developed into a kind of “open-air laboratory” for this complex of interests.

The blue tit is still a preferred research object today, not least because its brood biological variables can be easily controlled in nesting boxes and the species does not shy away from human proximity. Based on many existing test results, the appropriate questions can be asked and a promising test setup can be selected. The blue tit is therefore also suitable as a model organism for questions that go beyond the species itself and enable more general knowledge relating to ecology .

literature

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim , KM Bauer : Handbook of the birds of Central Europe (HBV). Volume 13 / I: Muscicapidae - Paridae. AULA-Verlag, ISBN 3-923527-00-4 .

- Manfred Föger, Karin Pegoraro: The blue tit . Neue Brehm Bücherei, Hohenwarsleben 2004, ISBN 3-89432-862-2 .

- Josep del Hoyo et al .: Handbook of the Birds of the World. (HBW) Volume 12: Picathartes to Tits and Chickadees. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2007, ISBN 84-96553-42-6 .

- Jochen Hölzinger : The birds of Baden-Württemberg . Volume 3/2, songbirds / passerine birds , Eugen Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8001-3483-7 .

Web links

- Blue tit in birds of Switzerland

- Pictures of a blue tit nest on a bald cypress

- Instructions for a blue tit nesting box

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Cyanistes caeruleus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Cyanistes caeruleus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on 12 November, 2008.

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 2.3 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta and Gerd-Michael Heinze (English)

- Feathers of the blue tit

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , field identifier, description, pp. 581-587.

- ↑ a b c d e f Föger, Pegoraro: The blue tit , general characterization, Altvögel, pp. 20–26.

- ↑ P. Mullen, G. Pohland: Studies on UV reflection in feathers of some 1000 bird species: are UV peaks in feathers correlated with violet-sensitive and ultraviolet-sensitive cones? . In: Ibis 105: 59-68, 2008. doi: 10.1111 / j.1474-919X.2007.00736.x .

- ↑ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Allgemeine Characterisierung, Jungvögel, p. 26 ff.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Mauser, p. 96 ff.

- ↑ Doutrelant et al. (2000): Effect of blue tit song syntax on great tit territorial responsiveness an experimental test of the character shift hypothesis. In: Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 48: 119-124 ( abstract )

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , voiced, pp. 589-596.

- ↑ a b Föger, Pegoraro: The blue tit , spread, p. 12 f.

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , breeding area, p. 596 ff.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. caeruleus , Spread, p. 579.

- ↑ a b c d e Föger, Pegoraro: The blue tit , systematics, subspecies, pp. 13-16.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Lebensraum und Siedlungsbiologie, pp. 29–33.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , Biotop, pp. 608-610.

- ^ W. Winkel, M. Frantzen (1991): On the population dynamics of the blue tit: Long-term studies near Braunschweig . Journal of Ornithology 132: 81-96

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , walks, p. 97 ff.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , Wanderings, pp. 600–608.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Überwinterung, pp. 99-102.

- ^ A b c d Föger, Pegoraro: The blue tit , nutrition, p. 36–47.

- ↑ a b c HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , Behavior: Food Acquisition, pp. 638–641.

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , food, pp. 651-656.

- ↑ a b Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Territorial and pair behavior, pp. 48–54.

- ↑ a b c d HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , Reproduction, pp. 614-629.

- ^ A b c Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Neststandort und Nestbau, P. 54–63.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Gelege, p. 64–72.

- Jump up ↑ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Incubation, pp. 72–77.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Schlupf, P. 78–81.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Nestlingzeit, S. 81–86.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Entwicklung der Jungvögel, pp. 86–89.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , behavior; Brood care, rearing and behavior of young; Pp. 647-651.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Ausflug der Jungvögel, p. 95.

- ^ A b Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Nestling losses, pp. 89–92.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Brutbiologie: Breeding success and delivery time reproduction, pp. 92–95.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , Breeding Success, Mortality, Age, pp. 629–634.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , behavior; Activity; P. 634 ff.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , behavior; Rest, cleaning; P. 637 f.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , behavior; Move; P. 636.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , behavior; Antagonistic behavior; P. 645 f.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: The blue tit , social behavior, p. 101.

- ↑ a b c Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Mortalität, pp. 105–110.

- ↑ Pneumonia: Mysterious tit deaths clarified , tagesschau.de of April 22, 2020, accessed April 23, 2020

- ↑ Mysterious Meisensterben , nabu.de, accessed on April 18, 2020.

- ↑ Interim results of the 2020 bird census - NABU. Retrieved May 12, 2020 .

- ^ Nadja Podbregar: Mysterious blue tit dying in Germany. In: scinexx. April 14, 2020, accessed April 14, 2020 .

- ^ Dpa report: Triggers for mysterious tit deaths identified , Die Welt from April 22, 2020

- ↑ Investigations confirm NABU suspicion , Naturschutzbund Deutschland (NABU) of April 22, 2020, accessed April 23, 2020

- ↑ cf. C. Sudfeldt, R. Dröschmeister, C. Grüneberg, S. Jaehne, A. Mitschke, J. Wahl (2008): Birds in Germany - 2008. DDA, BfN, LAG VSW, Münster, p. 7 (PDF) .

- ↑ a b c Föger, Pegoraro: The blue tit , population size and fluctuations in different areas, p. 103 f.

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. c. caeruleus , inventory, inventory development; P. 598 ff.

- ↑ Gill et al .: Phylogeny of titmice (Paridae): II. Species relationships based on sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene . In: The Auk. 122, 2005, p. 121, doi : 10.1642 / 0004-8038 (2005) 122 [0121: POTPIS] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ a b del Hoyo et al .: HBW Volume 12, Family Paridae , Systematic , pp. 662-669.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , systematics, kinship relationships within the tits, pp. 16-19.

- ↑ a b Dietzen, Garcia-del-Rey, Castro, Wink: Phylogeography of the blue tit (Parus teneriffae-group) on the Canary Islands based on mitochondrial DNA sequence data and morphometrics. Journal of Ornithology 149: 1-12, 2008

- ↑ Simon Harrap, David Quinn: Tits, nuthatches & treecreepers. Helmet Identification Guides . A & C Black, London 1996

- ↑ HBV Volume 13 / I, P. caeruleus , Geographische Variation, p. 579 ff.

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Name, p. 11.

- ↑ a b Föger, Pegoraro: The blue tit , relationship human - blue tit, p. 111 ff.

- ↑ Sonja Kübler: Food ecology of urban bird species along an urban gradient . Berlin 2005

- ^ Föger, Pegoraro: Die Blaumeise , Die Blaumeise - a model organism, p. 9 f.