La Palma

| La Palma | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Basic data | |

| Country: |

|

| Autonomous community: | Canarias |

| Province: | Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

| Surface: | 708.32 km² |

| Resident: | 83,458 (2020) |

| Population density : | 120.16 inhabitants / km² |

| Capital : | Santa Cruz de La Palma |

| President of the island government: | Anselmo Pestana Padrón |

| Island Council website: | www.cabildodelapalma.es |

| Location of La Palma within the Canary Islands | |

|

|

| Satellite image | |

|

|

La Palma (full name: La Isla de San Miguel de La Palma ) is the northwesternmost of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean . Together with the western Canary Islands of Tenerife , La Gomera and El Hierro , it forms the Spanish province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife . The eastern islands form the province of Las Palmas (named here is the capital Las Palmas of the island of Gran Canaria ). The autonomous community of Canarias ( Comunidad Autónoma de Canaria s) consists of these two provinces.

La Palma is one of the geologically youngest islands in the Canary Islands, whose volcanism is still visible in the many craters and lava flows along the volcanic route on the Cumbre Vieja and the large crater of the Caldera de Taburiente . With 40% forest cover it is the most densely forested compared to the other Canary Islands and is therefore also called Isla Verde ("Green Island").

geography

With an area of about 708 km², La Palma has a north-south extension of 45.2 km and a west-east extension of 27.3 km. With a share of 9.45% of the total area, it is the fifth largest island in the archipelago. La Palma is 417 km off the Moroccan coast, 1371 km from mainland Spain and 86.2 km west of Tenerife .

geology

Like all the Canary Islands, La Palma is of volcanic origin. Its origin is traced back to a hotspot in the earth's mantle , which built up the chain of the Canary Islands on the part of the African plate covered by the Atlantic . While the African plate drifts to the northeast over the stationary hotspot, shield volcanoes that now form the Canary Islands grew up in continuous eruptions over several million years . The shield volcano rising from 4000 m depth of the Canary Basin about 2-4 million years ago reached the sea surface 1.7 million years ago and gave rise to the island of La Palma. Today, pillow lava from the time of the earliest volcanism around 3 million years ago can be found in the lowest sections of the Caldera de Taburiente . These were raised by around 2 km together with the island as a result of the forcing magma . Iron-bearing rocks, oxidized by hot water vapor and colored red in the phase after the eruptions, also point to the early volcanic activity. Even clearer traces can be found in the underground irrigation systems, the galerías, which run through the massif.

The mountain massif of La Palma was built up by three large, overlapping volcanoes, the Garafia volcano, the lower and the upper Taburiente volcano . The Garafia volcano had a diameter of about 23 km at the base and a height of about 2500 to 3000 m.The steeply rising volcanic cone (0.8 mm / year) collapsed about 1.2 million years ago in a south-westerly direction and let in extensive debris field is created, which is referred to as "Playa de la Veta". Using submarine sonar measurements , an area of 2000 km², an extension of 80 km and a bulk volume of 650 km³ were determined. The topography of the field also shows a second bulk layer, that of the Cumbre Nueva (see below).

On the east side of the island a volcanic collapse occurred about 1 million years ago with the debris field Santa Cruz (extension: 50 km, area: 1000 km²), the origin of which is not known.

About a million years ago volcanism continued with the Lower Taburiente volcano , which rose above the crater of the Garafia volcano (more than 6 mm / year) and covered it with a 400 m thick layer of lava. Radiometric dating and differences in the chemical composition of the lava rock indicate a second volcano, the Upper Taburiente volcano , which reached an altitude of between 2500 and 3000 meters between 0.8 and 0.4 million years ago, and the lava layer of the Garafia volcano completely covered.

The volcanism on the island shifted southwards and built an elongated volcanic cone with a height of 3000 m, extending to the south. Its western flank collapsed about 500,000 years ago and gave rise to the Caldera de Taburiente and the Cumbre Nueva . The debris avalanche Cumbre Nueva with a volume of 95 km³ showered the debris field of the Playa de la Veta over an area of 780 km² and extends to a depth of 2500 to 4000 m.

In the middle of the caldera, volcanism continued 580,000 to 490,000 years ago with the Bejenado volcano , which rose in a relatively short time to 1864 m (12 mm / year).

The formation of the Caldera de Taburiente with a diameter of about 9 km and a circumference of about 28 km is now regarded as a product of the following geological events: The Cumbre Nueva debris avalanche, with the wrecking edge on the northeastern edge of the Caldera de Taburiente and the Cumbre Nueva -Ridge, the later backfilling by the Bejenado volcano and the ongoing erosion of the caldera and the Barranco de Las Angustias . At the northern edge of the crater is the highest point on the island, the 2426 m high Roque de los Muchachos .

The Cumbre Nueva is followed by a north-south ridge, the Cumbre Vieja . The mountain ridge rises to around 2000 m and divides the island into two climatically different halves. The volcanic activity of the Cumbre Vieja began 150,000 years ago and continues to this day. The penultimate volcanic eruption took place in 1971 on the southern tip of the island near Los Canarios, creating the Teneguía volcano . On September 19, 2021, an eruption began near the Cabeza de Vaca in the Cumbre Vieja in the municipality of El Paso . The lava flow drains to the west.

The volcanic eruptions were always accompanied by a series of earthquakes that preceded them and thus also heralded them. The seismic activities in the Canary Islands are determined by the ongoing volcanism. Tectonic earthquakes , on the other hand, are minor due to the geographical location of the islands on the ocean-African plate .

The volcanic risk on La Palma is derived from the seven volcanic eruptions that have occurred since the conquest of La Palma in 1492, when records began (see table). In the past 523 years, they occurred at intervals of 31 to 237 years with no discernible trend over future shorter or longer intervals. The average interval between volcanic eruptions on La Palma is then 73 years, corresponding to an average frequency of 0.014 per year. In 2018, the Canary Islands Volcano Institute estimated the risk of eruption within the next 50 years to be 48%. However, with the exception of the 83-day Tajuya event of 1585 with a Strombolian eruption , the damage effects of the volcanic eruptions on the population were minor. They were limited to the area of the Cumbre Vieja, the geologically youngest part of the island, and there largely to its ridge location. The volcanic eruptions consisted mainly of slow-flowing lava flows.

In contrast to the volcanic risk, the earthquake risk is more extensive and affects the entire area of the island. In connection with the San Juan volcano, earthquake tremors of intensity VIII occurred in the center of the volcano near Jedey, and in the distant towns of Santa Cruz and Barlovento there were still intensities IV and III. In December 2013, the undersea earthquake west of El Hierro to Santa Cruz was clearly noticeable.

In 2017, the first larger swarm of earthquakes occurred on La Palma, which has been registered since the commissioning of the monitoring network after the Teneguia eruption in the early 1970s. It falls into the category of volcanotectonic earthquakes, which, through a horizontal displacement of the magma, cause tensions in the rock bedrock and trigger earthquakes in a narrowly limited area and time period with a similar magnitude. Such volcanic earthquakes at relatively great depths and low magnitudes do not indicate an imminent volcanic eruption. In the previous years from 2000 to 2016 only eight earthquake events were registered in the area of La Palma, whereas in the south of Tenerife and the strait between Tenerife and Gran Canaria between January 1, 2000 to December 1, 2017 a total of 2352 events were measured. Several events occurred nearly every month during this period. On October 2, 2016, an earthquake swarm with 98 events took place in Tenerife.

Historically documented volcanic eruptions and earthquakes

| Year (duration) |

Volcano / earthquake (location) |

Volcanic height |

Earthquake ( intensity / magnitude ) |

effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1470–1492 exact date unknown |

Montaña Quemada ( Tacande ) |

1362 m | A lava flow emerged from the eruption of the crater's flank to the northeast and covered an area 8 km long and 1 km wide at the foot of the Cumbre Nueva as far as El Paso . | |

| 1585 May 19 - August 10. |

Tajuya (above Jedey) |

1871 m | There were many tremors before the volcanic eruption. Several volcanic cones and eruption sites formed an eruption fissure, from which lava flowed down to the sea and created a land area of around 1.5 km² in the area between Puerto Naos and Charco Verde. A considerable ash shower fell on the land, and many people were killed by the toxic sulfur fumes. Six weeks later, the island was shaken again by violent tremors. | |

| 1646 09/30 - 12/21 |

San Martin ( Tigalate ) |

1300 m | A strong earthquake preceded the volcanic eruption and houses threatened to collapse. The eruption site formed a small cone southeast of the 1529 m high main crater, from which the lava flow on the east side of the Cumbre formed a 7.5 km² lava area. | |

| 1677/78 17.11.-01.21. |

San Antonio (below Fuencaliente ) |

632 m | A slight earthquake preceded the volcanic eruption. The eruption points occurred on the flanks of the volcanic cone, through which seven lava flows flowed to the sea and formed extensive lava platforms. (The large volcanic cone visible today was not the eruption site where a massive eruption took place around 3,200 years ago.) | |

| 1712 October 9th – December 3rd |

El Charco ( El Paso , above El Remo) |

1700 m | Several earthquakes occurred from October 4th to 8th, followed by a major earthquake after a period of rest. From a series of eruptive vents along a roughly 2.5 km long crevice, lava flowed west to the sea at today's El Remo, creating an extensive platform. Around 6.4 hectares of arable land were lost. | |

| 1903 09/23 |

Earthquake ( Santa Cruz ) |

VI | ||

| 1920 January 20th |

Earthquake ( Cumbre Vieja ) |

VII | ||

| 1936 July 23. |

Earthquake ( Caldera de Taburiente ) |

III | A series of earthquakes occurred on the southern edge of the Caldera de Taburiente and in the Valle de Aridane | |

| 1939 02/21 - 04/02. |

Earthquake (Cumbre Vieja) |

V, VI | Earthquake tremors in Los Llanos, in Fuencaliente the lighthouse was badly damaged. | |

| 1947 January 23. |

Earthquake (El Paso) |

V | Earthquake tremors in El Paso | |

| 1949 February 22nd - March 7th. |

Swarm of earthquakes (south of the island) |

The earth shook almost every day. A violent earthquake in the south of the island, walls collapsed, the lighthouse of Fuencaliente was damaged and several crevasses tore open in an east-west direction. | ||

| 1949 June 24th - August 4th |

The volcanic eruption occurred at three spatially separate locations, which were connected by a system of crevices about 3 km long. On June 24th, the newly formed crater Duraznero opened under violent tremors and lava flowed off to the east. On July 1st a strong earthquake shook the whole of La Palma, there was great damage to walls and roofs and there was considerable damage in Los Llanos. On July 8th, a crevice opened at Llano del Banco above San Nicolás, from which lava flowed westward into the sea and new land of about 2 km² was created, where today the place La Bombilla and the lighthouse Faro de Punta are located Lava (this is where the Tubo Volcánico de Todoque lava tunnel was created , accessible as Cueva de Las Palomas since the visitor center opened ). On July 12th, the Hoyo Negro broke out and spat ashes. | |||

|

San Juan Duraznero, Llano del Banco, Hoyo Negro (San Nicolas) |

1820 m, 1300 m, 1871 m |

VIII: Jedey VII: Puerto Naos V: Los Llanos IV: Santa Cruz |

||

| 1971 October 21 - November 18. |

Teneguía (below Fuencaliente) |

439 m | II-V | A series of tremors began on October 21st. A day before the volcanic eruption, the island was hit by a strong earthquake. Lava emerged from eruption crevices of the volcano (up to 300 m in length) and flowed to the sea, creating around 29 hectares of new land. Two people were killed as a result of CO 2 gases that accumulated in terrain depressions. |

| 2011 04/17 |

Single earthquake (north / north-east Atlantic) |

? / 3.9 | An earthquake was registered 100 km north of La Palma. Shortly afterwards, large amounts of water poured out of the Laguna de Barlovento reservoir . With 2.5 million m³ it is the largest storage basin on the island. | |

| 2012 09/16 18 50 |

? / 3.7 | Earthquake in the Atlantic off La Palma, 64 km north of Santa Cruz. The night before, 17 earthquakes with a magnitude of up to 3.2 were recorded on El Hierro. | ||

| 2013 09/22 |

? / 3.0 | An earthquake with several tremors struck about 20 km off the northeast coast near Barlovento. | ||

| 2014 02/10 |

? / 3.7 | About 3 km off the coast of Los Sauces , an earthquake occurred at a depth of 40 km. | ||

| 2017 October 7th - October 14th |

Swarm of earthquakes (south of the island) |

? / 1.1-2.9 | The earthquake swarm with 127 events occurred in the area of the volcanic chain of the Cumbre Vieja, at a depth of 20 to 33 km on the border between the oceanic crust and the upper mantle, in which the hotspot is suspected. | |

| 2018 02/11 - 02/14 |

? / 2.3-2.5 | 10 earthquakes with magnitudes of 2.3 to 2.5 | ||

| 2020 July 24th / 25th / 30th |

? / 2.3-2.5 | 7 earthquakes with magnitudes of 2.3 to 2.5 | ||

| 2021 09/12 - 09/19 |

? / 2.1-3.8 | 452 earthquakes with magnitudes from 2.1 to 2.6, 79 with magnitudes from 2.7 to 2.9, 38 with magnitudes from 3.0 to 3.8 at depths of 12 km and shortly before the eruption at a depth of 1 km. | ||

| 2021 09/19 - 12/14 |

From September 11, 2021, a steadily intensifying swarm of earthquakes developed in a series of several thousand earthquakes with a strength of up to 3.8 on the Richter scale . The eruption began on September 19 at 3:12 p.m. WEST / local time in the area of Cabeza de Vaca. Ash, smoke and lava are emitted through more than four chimneys. | |||

|

Cumbre Vieja |

1122 m | V / 5.1 | ||

Teneguía volcano , eruption in 1971

Lava flow on the Cumbre Vieja near Cabeza de Vaca, eruption 2021

Volcanic eruption landslide tsunami theory

An investigation in the 1990s showed that the interior of the Cumbre Vieja had water-soaked, vertical layers of porous volcanic rock. British geologists put forward the theory that the western flank of the Cumbre Vieja could become unstable if a new volcanic eruption occurs and slide into the sea. This massive landslide would trigger a megatsunami . This theory was promoted in a BBC documentary in 2000. A detailed study by the TU Delft in 2006, however, considers a landslide to be likely in 10,000 years at the earliest and also assumes a slide in several stages, which makes a tsunami of the extent assumed by the BBC documentation unlikely.

climate

The year-round mild climate on La Palma is largely determined by the northeast trade winds and the Canary Islands .

The trade winds meet at an altitude of between 600 and 1700 m in the northeast of the island on the pine-wooded mountain slopes of Barlovento, where the up to 30 cm long needles of the Canary Pine comb out the clouds ( fog condensation ) and so precipitation amounts between 1000 and 1500 mm in the Generate year. The amount of water supplied to the ground is around two to three times the amount of precipitation that would occur without the effect of fog condensation. The water, which is constantly dripping to the ground, seeps through the porous lava rock and collects in large caves in the interior of the island, which act as natural water reservoirs. The large number of pines on the island contributes significantly to the total water balance of La Palma.

A characteristic picture of the flow of trade winds arises on the Cumbre Nueva at an altitude of about 1450 m, where the clouds roll over the mountain ridge and dissolve on the west side. The phenomenon is known as Cascada de nubes ("cloud waterfall").

On the east side of the island, for example, the average annual rainfall is 900 mm in Barlovento and 507 mm in Santa Cruz . In the southwest facing away from the Passat, on the other hand, there are significantly lower annual volumes, in Tazacorte it is 284 mm.

The second climate-determining factor is the Canary Current , a cool to moderately warm ocean current. It ensures a balanced temperature level on the island throughout the year. At La Palma airport , for example, the average annual temperature is 20.3 ° C, with the lowest values in January and February at 17.6 ° C and the highest values in August and September at 23.5 ° C.

Temperatures on the island vary considerably depending on the altitude, as the temperature drops with increasing altitude . The hair dryer effect also plays a role, the drier air that has rained down on the west side is warmer than the air on the east side.

The wind called Calima , which arises over the Sahara , carries very dry, hot air and the finest sand dust. In summer it can let the temperatures rise to 45 ° C. The sand dust gives the air a yellowish tint, deposits as a layer of dust, deteriorates air quality and affects visibility, which can affect air traffic. Such a weather situation occurs on La Palma several times a year for about three to five days each time.

Forest fires

Forest fires , which have recurred in the Canary Islands, contributed significantly to biological evolution , such as by stimulating plant growth, natural regeneration and biodiversity . After a fire, the Canarian pine forest regenerates in 8 to 10 years. After just one year, young pine needles emerge from the charred bark of the pine trees. Only an accumulation of fires (in periods of less than 6 to 8 years) would prevent the forest from regenerating.

Forest fires in the Canary Islands mainly occur in the dry summer time in late summer and during the hot desert wind Calima.

From 1988 to 1998 there were four large-scale forest fires on La Palma with dimensions of 8 to 55 km².

One of the most serious forest fires occurred in Garafía in July / August 2000 when 39.12 km² of forest and scrubland were destroyed. A fire that was not completely extinguished at a barbecue was identified as the cause of the fire. In Tijarafe , numerous residents had to leave their homes.

In September 2005, a six-day forest fire in Garafía killed around 20 km² of forest before it was ended by the use of eight fire-fighting helicopters, two aircraft and a large number of helpers. Dense cloud banks over the zone of the forest fires had repeatedly hindered the fire fighting work from the air.

In August 2009, the pine forest in the municipality of Mazo burned . Thousands of residents had to be evacuated, around 50 houses burned down and several vineyards were destroyed. Around 20 km² of forest and farmland fell victim to the fire.

In July 2012 - supported by the Calima - violent forest fires broke out around the same time on Tenerife , La Gomera and La Palma. The dry pine needles that were abundant on the forest floor acted like fire accelerators. The jointly used fire-fighting helicopters and fire-fighting aircraft on the western Canary Islands were at their capacity limits when they were used on the three islands.

In July 2012 a forest area burned above El Paso to Las Manchas and a month later the forest in the municipality of Mazo, 7.52 and 20.28 km² of forest and some houses were destroyed. The residents of two places in Mazo had to be temporarily evacuated.

In the summer months of 2013 (in Tajarafe) and 2014 (in El Paso, Breña Alta and Garafía) there were again forest fires at temperatures of up to 40 ° C, but their spread was significantly less than in the previous years mentioned.

On August 3, 2016, a forest fire broke out in the Tamanca region below Jedey, which, due to strong winds and temperatures of 37 ° C, spread quickly north to El Paso and later south to Fuencaliente and Mazo and lasted for several days. A 27-year-old German who negligently caused the fire - according to his own account by burning toilet paper to hide his illegal presence - was arrested. In May 2017 he was sentenced to three and a half years in prison and compensation payments by the district court in Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The 300-man La Palmas fire-fighting force and the two island helicopters were used to fight the fire. In addition, soldiers from a special unit against environmental disasters with 26 all-terrain vehicles and additional fire-fighting aircraft were deployed from the neighboring islands. An employee of the island's environmental agency, who had helped with the extinguishing work, was killed in the flames. The extinguishing work in Mazo and Fuencaliente was made more difficult by the fact that several water pipes burst due to the extreme heat of the forest fire, which are fed via an 82 km long water channel from the water-rich northeast of the island. A total of around 4,000 residents from the communities threatened by the fire had to leave their homes. The fire destroyed the pine forest over an area of around 40 km² as a result of various firebreaks.

On August 17, 2021, during a calima, a bush fire of introduced cat's tail grass (Rabo de Gato) broke out on the outskirts of El Paso, which destroyed 30 residential buildings and several more gardens.

nature and landscape

Flora and vegetation

Compared to the other Canary Islands, La Palma is geologically distinguished by its steep slopes, which result from the relatively small island area of 708 km² and the mountain range with the 2426 m high Roque de los Muchachos . At the different altitudes, in the course of the island's history, isolated from the mainland and human influence, diverse forms of vegetation have developed by creating their own strategies for survival. Of the approximately 800 different free-growing plants, 45 are island-endemic , i.e. H. they only grow there. The Palmerian botanist Arnoldo Santos names 70 local endemic plant species.

The volcanic origin with the formation of the lava soil and the geographical location of the island in the flow of the trade winds are essential factors in this development. With the Spanish conquest of the island in the 15th century, additional plants were introduced by humans, the so-called adventitious plants .

Due to the height differences on La Palma, five levels of vegetation (also height levels ) are distinguished in which different forms of vegetation have developed:

- Coastal zone (up to 500 m): The coastal vegetation is determined by dwarf shrubs such as the comb-shaped sea lavender . Especially on the west side, which is characterized by drought, heat and solar radiation, canary spurge and balsam spurge are often found at altitudes of up to about 800 m . The dragon tree is also widespread .

- Laurel forests (500–1000 m): The laurel tree occurs in up to 20 different shrub and tree species and can reach heights of up to 30 m. The laurel forests are typical of the east side, especially in the Los Tilos biosphere reserve.

- Tree heather (1000–1500 m): The tree heather (Brezo) and the Gagel tree (Faya), which can reach heights of up to 20 m, grow here .

- Pine forest (1500–2000 m): The pine forests dominate in this altitude area . Among other things, the comfrey-leaved rockrose grows in their undergrowth . Due to the condensation of fog , the Canary Islands pine with its long needles contributes significantly to the water balance of La Palma beyond its own needs (see climate ). With the thick, cork-like bark of the Canary Islands pine, it is largely resistant to repeated fires. In the event of a fire, only the bark is charred, the actual trunk remains undamaged. Green pine shoots sprout from the charred bark after only six months.

- Subalpine high mountain forms (from 2000 m): At this altitude, where trees no longer grow, the weather conditions alternate between frost, heavy freezing rain, intense cosmic radiation and extreme drought. Unique plants grow there, such as the sticky gorse , a special scotland , the gentian-like adder head and wild prets adder head . These species are only found at high altitudes in the Canary Islands.

A specialty among the Canarian pines is the El Pino de la Virgen in the municipality of El Paso . With a diameter of about 240 cm and a height of about 32 m, it is one of the largest and oldest of its kind; their age is estimated to be 800 years.

In addition to the native plants, there are numerous free-growing plants introduced by humans on the island. The prickly pear (on which the scale insects were bred to obtain the red pigment until the 19th century) are widespread in rural regions . Its red fruits with fine thorns are very sweet and edible. Indian laurel grows mainly in cities . The poinsettia from the milkweed family grows as a meter-high shrub and originally comes from Mexico . The fig tree grows mainly in mountain regions. Free-growing ornamental plants include hibiscus , oleander and strelitzia .

La Palma owes its nicknames La Isla bonita ("The beautiful island") and La Isla verde ("The green island") to the diversity and - at least in the northeast - year-round green vegetation .

fauna

The fauna on La Palma - as on the rest of the Canary Islands - is mainly determined by reptiles and birds.

The La Palma giant lizard , the Canary Islands lizard , the Tenerife Gecko , sea turtles , the Graja , the Berthelot's Pipit , the Atlantic Canary , the Tenerife Goldcrest , the Canary Islands pigeon and the laurel pigeon typical of La Palma. A subspecies of the common buzzard ( Buteo buteo ssp. Insularum ) also breeds near humans; it is often wrongly identified as an eagle buzzard .

The Mediterranean tree frog and the Iberian water frog live in the more humid regions in the northeast of the island . The Canarian Giant Runner ( Scolopendra valida ), which is up to 15 cm long, also prefers a humid environment; its bites can be very painful.

Butterflies, among others the Canarian whiteling , the Canarian admiral and the Canary forest board game are just as common as dragonflies . The cochineal scale insect was introduced to produce red dye (see also the history section ) and is now widely used.

Protected areas

There are 21 nature and landscape protection areas on La Palma:

- a strict nature reserve ( Reserva Natural Integral, IUCN Category I)

- a national park ( Parque Nacional, IUCN category II)

- two nature parks ( Parque Natural, IUCN Category II)

- eight natural monuments ( Monumento Natural, IUCN Category III)

- a species protection area ( Reserva Natural Especial, IUCN Category IV)

- three areas of scientific importance ( Sitio de Interés Científico, IUCN Category IV)

- four Protected Landscapes ( Paisaje Protegido, IUCN Category V)

- a marine reserve (Reserva Marina)

Strict Natural Reserve of

Pinar de GarafíaCaldera de Taburiente National Park

Cumbre Vieja Natural Park

Natural Monument

Tubo Volcánico de Todoque

From the UNESCO two protected areas have been especially certified, each comprising the entire island:

- the La Palma Biosphere Reserve (Reserva de la Biosfera)

- the La Palma Starlight Reserve (Reserva Starlight)

Furthermore, nine Natura 2000 protected areas have been designated, most of which overlap with the above mentioned protected areas.

Natural symbols of the island

Natural symbols of the island of La Palma are: Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax barbarus and Pinus canariensis .

Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax barbarus

story

First settlement

The first traces of the presence of humans in the Canary Islands, proven by archaeological finds, date from the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. A permanent settlement does not seem to exist until the 3rd century BC. To have taken place. The oldest finds on the island of La Palma come from the Cueva de La Palmera ( Tijarafe ). They were established around the 3rd century BC. Dated. Over a long period of time, settlers from the area around the Strait of Gibraltar seem to have come to the Canary Islands again and again . In the 1st century AD there were close economic ties between the Roman Empire and the Romanized states of North Africa and the Canary Islands. With the imperial crisis of the 3rd century AD, the connections between the island of La Palma and the Mediterranean culture area broke off. Since the natives had neither the tools to build seaworthy ships nor nautical skills, they were unable to maintain connections with the other islands. In the following 1000 years up to the 14th century, the Benahoaritas , the native inhabitants of the island, developed their own culture on La Palma.

Rediscovery of the Canary Islands in the 14th century

When the Canary Islands were rediscovered in the 14th century, the island of La Palma was not the focus of European interest. Niccoloso da Recco, the reporter of a research trip sent in 1341 by the Portuguese King Alfonso IV , reports that there were high rocky mountains and abundant rainfall on the island and that the indigenous people settled on the coast. Niccoloso da Recco has probably not entered La Palma and Tenerife. The map drawn by the brothers Francesco and Domenico Pizzigano in Venice in 1367 shows the island of La Palma. This island is missing from the representation of the Catalan World Atlas by the Mallorcan Abraham Cresques from 1375.

Attempts at submission by Europeans

- Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de La Salle

The native of Normandy in France Jean de Béthencourt had 1403, after he had the Castilian King Henry III. recognized as its overlord, had the right to conquer and rule all the islands of the Canary Islands. Until 1405 Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de la Salle were able to subdue the population of the islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and El Hierro. They landed several times between 1402 and 1405 on the island of La Palma. This brought about contacts with the population. There is no evidence of violent clashes. A longer stay of the two French on the island is rather unlikely.

In 1405 Jean de Béthencourt left the archipelago and put his relative Maciot de Béthencourt as a deputy. In 1418 he was forced to transfer all claims to rule over the islands to Enrique de Guzmán, Count of Niebla. In the course of the next few years, the rights passed several times to other people.

- Diego García de Herrera y Ayala

In 1445 Guillén de Las Casas transferred his rights to the Canary Islands to Hernán Peraza (el Viejo) and his children Inés and Guillen Peraza de Las Casas. At the end of 1447, Guillén Peraza de las Casas landed with five hundred men from Seville, Lanzarote and Fuerteventura near what is now the city of Tazacorte . The aim of the attack on the indigenous people was probably not to gain control of the area. Rather, it was one of the many acts of piracy that took place on the islands during the rule of the Peraza family. Natives were captured and sold as slaves on the Spanish peninsula. The soldiers, who could not cope with the mountainous terrain and could not fight in their usual order of battle, were attacked from all sides by the Benahoaritas with spears and stones. After Guillén Peraza was fatally injured in the head by a stone, the attack was called off.

Preparation for the conquest

In 1476, Queen Isabella I and King Ferdinand V of Castile commissioned a group of lawyers to prepare an expert report on the legal situation in relation to the Canary Islands. The report stated that Diego García de Herrera y Ayala and his wife Inés Peraza de las Casas were entitled to property and sovereign rights over the four islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, La Gomera and El Hierro and that they also had the rights to conquer them the islands of Gran Canaria and Tenerife and La Palma. In 1477 Diego García de Herrera y Ayala and Inés Peraza de las Casas ceded these conquest rights in exchange for compensation to the Crown of Castile. In the period between 1478 and 1483, the island of Gran Canaria was conquered by order of the Crown of Castile . In the Treaty of Alcáçovas in 1479, the Canary Islands were recognized as an area of interest for the Crown of Castile. The concentration of funds on the conquest of Granada resulted in a complete lack of initiative on the part of the Crown of Castile to conquer the islands of La Palma and Tenerife between 1482 and 1492. In order to prepare the submission of the population of these islands, the governor of Gran Canaria Francisco Maldonado contacted the rulers of the tribes of the island of La Palma at the beginning of 1492 with the aim of convincing them that resistance against the Castilians was hopeless .

Conquering the island

In 1491 Alonso Fernández de Lugo started negotiations on the conquest of the island of La Palma at the court of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, who at that time had settled in the camp of Santa Fe . He also met Christopher Columbus there , who was negotiating the terms of the surrender of Santa Fe . After an agreement between Alonso Fernández de Lugo and the representatives of the Crown of Castile, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand issued a capitulación in June 1492 in which Alonso Fernández de Lugo was entrusted with the conquest of the island of La Palma and he was promised the office of governor.

In 1492 Alonso Fernandez de Lugo landed near the present-day city of Tazacorte with an army of around 900 men . The troops were able to advance to the south of the island without fighting. This lack of resistance is attributed to the fact that the rulers of the districts of Aridane, Tihuya, Tamanca and Ahenguareme were baptized in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and therefore cooperated with the Castilians. There was an armed clash with the indigenous people near what is now the town of Villa de Mazo , in which the indigenous people had to retreat defeated. The occupation of the island continued without incident of major importance. At the end of winter only the Aceró district remained, in the Caldera de Taburiente under the rule of the indigenous people.

A military victory over the Acerós, under their "King" Tanausú, was not possible for the Castilians due to the basin location of the tribal area. A siege seemed ineffective, as the population of the Caldera de Taburiente was almost self-sufficient . Therefore, Lugo had to rely on negotiations. Tanausú and his people were captured by betrayal. This broke the last resistance on the island. On May 3, 1493, Alonso Fernández de Lugo declared the conquest over. As the future capital, he founded what is now called Santa Cruz de La Palma on the east coast of the island.

Distribution of land and water rights

After completing the conquest of the island of La Palmas in May 1493, Alonso Fernández de Lugo traveled to Gran Canaria with the aim of organizing the conquest of the island of Tenerife. In the autumn of 1493 he negotiated the conditions for the conquest of Tenerife at the court, who was staying in Zaragoza at the time . By the "Capitulaciones de Zaragoza" he was obliged to conquer the island of Tenerife with the means he had raised. As a result, Alonso Fernández de Lugo could not personally carry out his duties as governor of the island of La Palma in the next few years. His nephew, Juan Fernández de Lugo Señorino, whom he had named as deputy, was only authorized to distribute land and water rights in 1499. There are no original documents on the decisions in this area. They can only be reconstructed from later documents such as sales contracts and wills. The distribution of land and water rights was somewhat unsystematic in the beginning. By occupying and using the land and building processing plants, the beneficiaries created facts that were later mostly confirmed. At the end of 1501 Alonso Fernández de Lugo returned to La Palma and officially began the allocation of land and water rights, with he and his deputy Juan Fernández de Lugo Señorino being the main beneficiaries.

Incorporation of La Palma into the kingdoms of the Crown of Castile

La Palma was incorporated into the kingdoms of the Crown of Castile as one of the Canary Islands. The city of Santa Cruz de La Palma received, like the capitals of the other islands that were directly under royal rule (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and San Cristóbal de La Laguna), an administration that was organized on the model of the city of Seville. The first meeting of the Cabildos of the island or the city of Santa Cruz de La Palma took place on April 26, 1495. It consisted of six members ( Regidores ), two judges ( Alcaldes ) and a secretary (Escribano).

Colonial times and development until the 18th century

The cultivation of sugar cane - at that time the most profitable arable product - was at the beginning of the economic development of La Palma. European merchants, artisans, wine and arable farmers were called to the island to invest capital and labor in sugar processing plants. The properties and lands changed hands repeatedly during this development phase: in 1508 Juan Fernández de Lugo, the nephew of the Spanish conqueror Alonso Fernández de Lugo , sold his sugar processing and irrigation plant in Tazacorte and Argual to the Andalusian Dinarte ; this sold them a year later to the Augsburg Welser ; again a year later (1510) they came into the possession of the Antwerp merchant Jakob Groenenberch (Hispanic: Jacomo Monteverde), from whom they finally acquired the Brussels trading house Van de Valle .

From 1553 the sugar cane cultivation on La Palma was less and less worthwhile . In Central and South America , production was cheaper. Many sugar cane plantations that were no longer profitable were converted into vineyards. The sweet Malvasia that thrives on young volcanic soil, especially in the south of the island , became La Palma's most important export product. The main buyer of the Palmerian wine was England . The triumphant advance of the Palmerian Malvasia lasted until the middle of the 19th century, then changing consumer tastes led to the decline of viticulture. Today wine is grown again with increasing success.

La Palma became an important stopover for the Spaniards on the way to the West Indies . In the 16th century, after Antwerp and Seville , La Palma was given the privilege of trading with America. Santa Cruz de La Palma quickly developed into one of the most important ports of the Spanish Empire. In the course of the 16th century, Santa Cruz de La Palma repeatedly attracted pirates who wanted to seize the city's riches. Under the orders of François Le Clerc , the French looted the port city in 1553. What they couldn't take with them they burned down. After this disaster, churches, monasteries and houses were rebuilt larger and more splendid.

New defenses were built, which consisted of several bastions and walls. Of the old fortifications in Santa Cruz, only the Castillo de Santa Catalina (listed in 1951) and the Castillo of the Barrio de Santa Cruz north of the mouth of the Barranco de Las Nieves are preserved.

In 1585, the attack by the Englishman Francis Drake was successfully repulsed. Trade with America favored the emergence of other branches of business such as shipbuilding and the manufacture of canvas. Numerous merchants from all over the world came to Santa Cruz and gave the place an international flair; many foreign-sounding street names still bear witness to this era. However, the decline began as early as the middle of the 17th century. According to a decree from 1657, all ships on their way to America had to be registered in Tenerife and pay their duties there. The trade in the port of Santa Cruz de La Palma almost came to a standstill. Although King Carlos III. 1778 free the American trade for all Spanish ports, but Santa Cruz could never fully recover from the economic crisis.

After this economic downturn, investments were made in new products such as beeswax and honey, tobacco and silk. With the planting of mulberry trees , La Palma was a leader in silk production in the Canaries. Around 1830 from was Mexico originating cochineal -Laus introduced a scale insect that a coveted crimson delivers dye. However, with the development of aniline paint around 1880, this branch of industry only made a short profit.

From 1878 onwards, banana cultivation was brought to the Canary Islands on a large scale by the Elder Dempster companies from England and Fyffes from Ireland, which is still an important and growing economic factor on the island today.

The rural population of La Palma hardly benefited from the island's wealth. Since mainly monocultures were grown on the island , the remaining arable land was insufficient for the cultivation of grain and other agricultural products. As early as the 16th century, grain had to be imported at high prices. As the chapter of La Palma once his tithes demanded in the form of wheat from the granary, the population to settle in this way their taxes refused, whereupon the Inquisitor one of the island excommunication imposed and some years no one was buried Christian.

19th and 20th centuries

In the 19th century, most of the islanders lived in thatched wooden huts or in low stone houses. In order to strengthen the economy of the Canary Islands, the archipelago was declared a free trade zone in 1852 by a decision of Queen Isabella II . The economic hardship in the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century led to a high level of palm emigration on La Palma. Cuba and Venezuela were the preferred destinations. Many Palmerian families still have strong family ties to these countries. In the 1920s and 1950s many returned to La Palma ("The return of the emigrants", see section Regional festivals, Carnival).

In 1860, road planning began on La Palma by establishing the necessary connecting roads between the localities. These included connections between Santa Cruz de la Palma via Breña Baja to Fuencaliente, from Fuencaliente to Tazacorte and Los Llanos de Aridane and from Santa Cruz via Puntallana to San Andrés. In 1879 the first 7 km long route between Santa Cruz de La Palma and Risco de la Concepción, which belongs to the municipality of Breña Alta, was provisionally recorded. Road works in the south of the island began in 1874 and ended in 1910.

As early as 1880, the Canario Pedro Reid and the Briton L. Jones began growing bananas on La Palma, which was supposed to compensate for the decline in sugar cane cultivation. This led to brief prosperity around 1900, but foreign trade came to a standstill due to the effects of the First World War . In 1927 the Canary Islands were divided into a western and an eastern province. La Palma forms together with Tenerife, La Gomera and El Hierro the western province "Santa Cruz de Tenerife". During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), La Palma was mostly on the side of the Republicans and, together with the Communist Party, formed the main place of resistance against the Franco regime in the Canary Islands.

The privileged location of the Canary Islands prompted the German Navy to position submarines in their vicinity during the Second World War - as in the First World War , which the German four-masted barque Pamir spent in Santa Cruz de La Palma. They were supposed to attack US ships that were crossing the Atlantic in support of the UK . On October 26, 1942, German submarines attacked a convoy of 37 ships northwest of the Canary Islands and sank three ships, including the British freighter Pacific Star . His survivors reached La Palma on October 31 in a lifeboat near the lighthouse Punta Cumplida . On May 29, 1944, about 100 nautical miles southwest of the Canary Islands, the aircraft carrier Block Island was badly damaged by the German submarine U 549 and sunk after another attack. Six crew members and four pilots from Block Island's 957 crew members were killed. Two pilots reached La Palma, near Tijarafe , with their machines .

Until the early 1960s, the Canarian economy was still dominated by agriculture. Liberalization in 1960 by the Franco regime led to an economic revival through exports of bananas (130,000 tons per year), tobacco and forestry products. Tourism developed as the most important growth engine; In 1960 there were 73,240 tourists, in 1975 it was over two million.

In 1984 both provinces were given the status of an autonomous region ( Province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Province of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria). With the accession of Spain to the European Community in 1986 and the accession of the autonomous Canary Islands to the EC in 1989, the Canary Islands also received EU subsidies, which were mainly used to build the infrastructure of the islands.

Culture and science

Religions

The vast majority of the population is Roman Catholic . Their saints from certain churches are honored with processions at regular intervals. These events run over several days and are accompanied by a supporting program and lively celebrations.

Regional festivals

There are several festivals, some of which are regionally limited, throughout the year. With the Almond Blossom Festival in Puntagorda in February or March , where most of the island's almond trees can be found, the round of festivities on the island begins. On May 3rd, the Fiesta de la Cruz celebrates the conquest of the island and the founding of the capital Santa Cruz. For this purpose, crosses are wrapped in valuable cloth and paper and decorated with flowers and candles all over the island.

The Bajada de la Virgen de las Nieves is one of the outstanding festivals on La Palma. It dates back to 1676 when the island was hit by a major drought. In order to avert an impending crop failure, the Canarian Bishop Jimenez ordered the statue of the Virgin of the Snow (Virgen de las Nieves), venerated across the island, to be carried from Las Nieves in a procession to the capital. The long-awaited rain then sets in. Since then, the procession has been repeated every five years for the 0s and 5s. The festivities drag on for more than a month each summer. A highlight of the fiesta is the dance of the dwarves in Santa Cruz.

Another highlight of the celebrations on La Palma is the carnival, whose parades and events in the strongholds of Santa Cruz and Los Llanos are reminiscent of the South American carnival. On Carnival Monday "the return of the emigrants" is celebrated in Santa Cruz. The Palmeros then dress completely in white - as a parody of those who came to prosperity in Latin America at the time and throw baby powder around them.

Cultural institutions and artists

The cultural offerings on La Palma include the archaeological centers, Parque Arqueologico in La Zarza, Garafia municipality and Cueva Belmaco in Mazo , several libraries (each in the larger towns on the island), the Circo de Marte theater , a cinema ( Teatro Chico ) in Santa Cruz and a cinema in Los Llanos as well as various music and art events, which mostly take place in the respective Casa de Cultura of the places. The island's museums include Museo Insular and Museo Naval (maritime museum in the replica Santa Maria caravel of Christopher Columbus ) in Santa Cruz, Museo Arqueológico Benahorita (Archaeological Museum) in Los LLanos , Museo del Platano (Banana Museum ) in Tazacorte and Museo del Vino (Wine Museum) in the Plaza de La Glorieta in Las Manchas, the Museo de la Seda in El Paso and the Museo del Tabaco in Breña Alta.

Luis Morera (born October 10, 1946) is one of the most famous artists on La Palma. His works include the Plaza de La Glorieta in Las Manchas, the El Jardín de las Delicias park in Los LLanos, the fountain with the bronze figure of San Miguel de La Palma in front of the town hall in Tazacortes , the bronze figure "The Dwarf" (Enano) in Santa Cruz as well as a multitude of images of the island's nature and people.

Manuel Pereda de Castro (* 1949 in Santander ; † November 27, 2018 on La Palma) was a Spanish sculptor, painter and set designer who settled on La Palma in 1986. At the beginning his works were still very figurative, the 6 m high monument to the mother ( Monomento a la Madre ) is considered a representative monument of the city of Los Llanos. Later he created various powerful abstract steel figures that fit into the landscape of the island. His greatest structural work, the Monumento a la Naturaleza is located between El Paso and the tunnel that the Palmeros call Arbol de la Graja ( crow's tree ). On November 30, 2018, the artist was posthumously awarded the title of honorary citizen of the island of La Palma ( Hijo Adoptivo de la Isla de La Palma ).

Palmerian cuisine

The Palmerian cuisine differs little from that of the other Canary Islands.

Until the 1960s, for most Palmerian families - especially in rural areas - the food consisted of the products they obtained such as potatoes, gofio (roasted and then ground grain), pork and goat meat, goat cheese , mojo (spicy sauce) , Milk, fish and some vegetables and fruits. Special dishes were prepared for festive occasions: desserts made from bread, honey and rice pudding, roasted chestnuts and biscuits. Goat cheese with mojo is still one of the special Palmerian dishes - also in the tourist sector.

Observatories

For the choice of La Palma as a location for an observatory, the altitude on the Roque de los Muchachos and a low " light pollution " of the night sky as well as a shorter distance to Europe compared to locations such as South America or Hawaii (at 4200 m) were decisive.

The founding members Spain, Sweden, Denmark and the United Kingdom decided as the first steps for the construction of the observatory to create an access road and the water and power supply as well as the establishment of a training program for Spanish astronomers. In 1985 the observatory was officially inaugurated. In 1988, the so-called Ley del Cielo ("Heavenly Law") was enacted to protect against nightly darkness . A test in 1995 in which the lights were switched off for an hour at night across the island did not reveal much difference. In 2012 La Palma was certified as the world's first Starlight Reserve .

In 2009 the Gran Telescopio Canarias (GRANTECAN, also GTC) was inaugurated by the Spanish King Juan Carlos and Queen Sophia . In 2018 it is still the largest telescope in the world consisting of a single (albeit segmented) mirror.

Mills on La Palma

The first mills on La Palma were built with sugar cane cultivation in the 16th century and were used to extract the juice from sugar cane. The water obtained from the mountains of La Palma for irrigation of sugar cane plantations was also used to power the mills. In places where there was not enough water available, windmills were used to grind grain. Of the ten windmills that remained on the island, El Molino de Las Tricias in Garafía and El Molino de Mazo have been completely renovated, the rest are in a dilapidated state.

The still existing water and windmills of La Palma are among the protected ethnographic assets of the Canary Islands.

Sports

Historical sports

Lucha Canaria is a Canarian wrestling match that was already fought among the Guanches. In 1420 the chronicler Alvar Garcia de Santa Maria reported on this sport of the Canaries. It is believed that disputes among the indigenous population were resolved bloodlessly through these battles.

Lucha is still one of the most popular sports in the Canary Islands today, alongside football. It is a team sport that is played by twelve fighters. There are always two wrestling with each other. The one whose upper body touches the ground first has lost. A fight lasts 3 rounds of a maximum of 2 minutes.

Shepherd's jump (Spanish: Salto del pastor) is a popular sport in the Canary Islands that has its roots in regional customs and probably goes back to the indigenous people, the Guanches. In order to overcome differences in altitude quickly and safely in the mountainous terrain in the shortest possible time, the herdsmen used a wooden stick several meters long, the “regatón”, to get to deeper terrain.

Transvulcania

The Transvulcania is an international ultramarathon that has been held annually on La Palma since 2009. The 73.3 km long running route begins at the lighthouse of Fuencaliente , leads over the volcanic route, the Cumbre Nueva, to the mountain range of the Caldera de Taburiente with the 2426 m high Roque de los Muchachos , down to Puerto Tazacorte and back up to Los Llanos , the goal of the ultramarathon. Altogether there is a difference in altitude of 8525 m (of which 4415 m uphill and 4110 m downhill).

administration

Within the Spanish autonomous community of the Canary Islands , La Palma belongs to the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife . The official language is Spanish , the locals speak a variety with a Latin American influence.

Island Council

The Island Council ( Cabildo Insular ) regulates matters that require an individual solution for the island and should therefore not be decided by the autonomous community, but which cannot be decided at the level of the municipalities because they affect the entire island.

The President of the Island Council is currently (2018) Anselmo Pestana. In addition, there are a further eleven members of the island government (seven of them vice-presidents) who are responsible for the various departments.

Personalities among the residents of La Palma

(For the extensive list of Palmero personalities, please see section "Palmeros destacados" in the article "La Palma" on Spanish Wikipedia)

- Jack Bruce , musician ( Cream )

- Rose Marie Dähncke , mushroom researcher

- Jürgen Fliege , pastor

- Claudia Gehrke , writer and publisher

- Manfred Günther (psychologist) , author

- Frigga Haug , sociologist, editor

- Wolfgang Fritz Haug , philosopher

- Helmut Kiesewetter , visual artist

- Harald Welzer , publicist

- Christine Wittrock , historian

Municipalities and population figures

La Palma is divided into 14 municipalities, whose area information can be found in the table below.

The population of La Palma recorded a moderate increase from 2000 to 2010 and an equally moderate decrease thereafter. In Santa Cruz, the population steadily decreased during this period, whereas the population in the municipality of Breña Baja, bordering Santa Cruz, increased. Los Llanos had a significant increase in population until 2010 and exceeded the number of inhabitants of the capital, after that the number has decreased slightly.

The more agricultural communities of Garafía, Barlovento, San Andrés y Sauces, Fuencaliente and Tazacorte are seeing declining populations.

However, the municipalities often leave the statistics unadjusted when they move, as the subsidies from Madrid are distributed to the Ayuntamientos based on the number of residents.

| local community | Area (km²) |

Population numbers | 2017 to 2010 1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||

| Barlovento | 43.55 | 2598 | 2694 | 2398 | 2507 | 2296 | 2085 | 2085 | 2005 | 1910 | 1886 | 1859 | −19.0% |

| Breña Alta | 30.82 | 5467 | 5567 | 5898 | 7039 | 7347 | 7298 | 7455 | 7293 | 7170 | 7086 | 7061 | −3.9% |

| Breña Baja | 14.2 | 3418 | 3537 | 4051 | 4355 | 5259 | 5492 | 5523 | 5366 | 5362 | 5377 | 5434 | + 3.3% |

| Fuencaliente | 56.42 | 1822 | 1804 | 1800 | 1913 | 1898 | 1840 | 1798 | 1745 | 1730 | 1705 | 1695 | −10.7% |

| Garafía | 103.0 | 2043 | 2032 | 2007 | 1924 | 1714 | 1654 | 1645 | 1618 | 1590 | 1607 | 1584 | −7.6% |

| Los Llanos de Aridane | 35.79 | 17062 | 17737 | 18190 | 19878 | 20948 | 20895 | 20930 | 20416 | 20227 | 20043 | 20107 | −4.0% |

| El Paso | 135.92 | 7154 | 7293 | 7289 | 7404 | 7837 | 7874 | 7928 | 7617 | 7563 | 7457 | 7464 | −4.8% |

| Puntagorda | 31.1 | 1692 | 1825 | 1785 | 1795 | 2177 | 1940 | 2057 | 2031 | 2027 | 2025 | 2009 | −7.7% |

| Puntallana | 35.1 | 2305 | 2296 | 2204 | 2424 | 2425 | 2428 | 2346 | 2348 | 2372 | 2387 | 2429 | + 0.2% |

| San Andrés y Sauces | 42.75 | 5399 | 5492 | 5229 | 5086 | 4874 | 4637 | 4473 | 4378 | 4265 | 4171 | 4135 | −15.2% |

| Santa Cruz de La Palma | 43.38 | 18183 | 17460 | 18204 | 17788 | 17128 | 16705 | 16330 | 16184 | 15900 | 15711 | 15581 | −9.0% |

| Tazacorte | 11.37 | 7049 | 6617 | 6147 | 5835 | 5697 | 4957 | 4911 | 4844 | 4771 | 4633 | 4620 | −18.9% |

| Tijarafe | 53.76 | 2734 | 2662 | 2672 | 2713 | 2769 | 2765 | 2776 | 2684 | 2596 | 2577 | 2590 | −6.5% |

| Villa de Mazo | 71.17 | 5112 | 5260 | 4609 | 4591 | 4955 | 4898 | 4858 | 4927 | 4863 | 4821 | 4782 | −3.5% |

| La Palma as a whole | 708.32 | 82.038 | 82,276 | 82,483 | 85.252 | 87,324 | 85,468 | 85.115 | 83,456 | 82,346 | 81,486 | 81,350 | −6.8% |

business

Agriculture and tourism are the main sources of income for La Palma.

Agriculture

The production of bananas on La Palma in 2012 contributed 125,000 tons to over 60% of the total sales of the island and 35% of the total exports of the Canary Islands. The cultivation of bananas takes place on around 30 km² of land. In addition, wine, avocado , citrus fruits and vegetables are increasingly being grown to diversify agriculture .

The small-fruited but robust dwarf banana still dominates banana cultivation on La Palma. It is increasingly being replaced by the more sensitive Giant Cavendish , whose fruits are larger and are therefore easier to market. In order to protect the new variety from strong winds and to ensure a higher level of humidity in the plantations, these are surrounded with high walls and plastic tarpaulins.

The large-scale banana cultivation subsidized by Spain and the EU also leads to ecological problems. For example, agriculture has been using more water for years than can compensate for the already decreasing rainfall. Water-bearing layers of volcanic rock are also used for irrigation. This causes the water table to drop and the few natural springs to dry up.

Agriculture is made possible by a unique irrigation system consisting of water pipes and tunnels that carry water from the mountains to the agriculturally used areas. These tunnels are sometimes driven hundreds of meters through rocks and bring the water over several kilometers into the inhabited areas on the coast.

Power supply

More than 90% of the electricity demand on La Palma is generated by the Los Guinchos power plant in the municipality of Breña Alta. 10 diesel generators and a gas turbine can generate up to 105.3 MW. Furthermore, several wind parks with a total output of 7.4 MW peak / 2.9 MW Avg (as of 2018) and photovoltaic systems with a total of 4.5 MW peak (as of 2012) contribute to the island's power generation.

Industry, trade and craft

In comparison to agriculture, industry, trade and handicrafts only play a subordinate role on La Palma. There are some companies that process agricultural products or manufacture building materials or handicrafts , as well as some construction companies that have enjoyed an upturn due to tourism, but which collapsed as a result of the 2008–2012 financial crisis. Thanks to the EU classification of the island as an “ultra-peripheral territory”, companies can save up to 90% on their sales tax when they reinvest it in real estate, etc. In addition, funds came from the Reserva para Inversiones en Canarias (RIC) investment program , which largely saved the construction industry, but in oversized, e. Road construction, etc. projects, some of which had a severe impact on the landscape, flowed which would never have been started without this program. This was also made possible by corruption on the part of local authorities.

The export of La Palma is limited to agricultural products. Overall, the island has a negative trade balance. Three quarters of the food has to be imported, including citrus fruits such as oranges and lemons and around 80% of the demand for animal products. Other important imported goods, mostly supplied from mainland Spain, are crude oil, consumer goods, mechanical and electrical equipment, and motor vehicles.

tourism

Tourism has played an important role in La Palma's economy since the 1980s. However, La Palma is not very touristically developed and there is no mass tourism . Instead, “ sustainable tourism ” is promoted. In 1890 there were the first small hotels on La Palma that were frequented by the English. Until the end of the 1980s, tourism on La Palma remained at a low level. The only large hotel (200 beds) at that time was built in Puerto Naos . During this time there were still reservations among the local population against the influx of strangers who expressed themselves at the time via graffiti on house walls ("Alemanes fuera" - "Germans out"). The fact that tourism on La Palma is now also an important source of income for the population has silenced such hostilities.

On the other hand, La Palma did not benefit from the beginning of mass and charter tourism on Tenerife and Gran Canaria in the 1980s. Only in 1985 with the enlargement of the airport on La Palma , on which also charter planes from Europe could land, the organized package tourism started on La Palma. This triggered an increased expansion of the holiday complexes in Los Cancajos near the airport and on the west side of the island in Puerto Naos. The number of foreign guests on the island in 1992 was 80,994. In the following years the number rose steadily until it reached its highest level in 1999 with 135,376 guests.

In the 2000s, a larger hotel complex ("Princess") with 880 beds, of which only 400 are used, was built in a secluded location in Las Indias on the southern tip of La Palma. In addition to the few larger hotels, tourists are mainly accommodated in pensions, holiday apartments and houses.

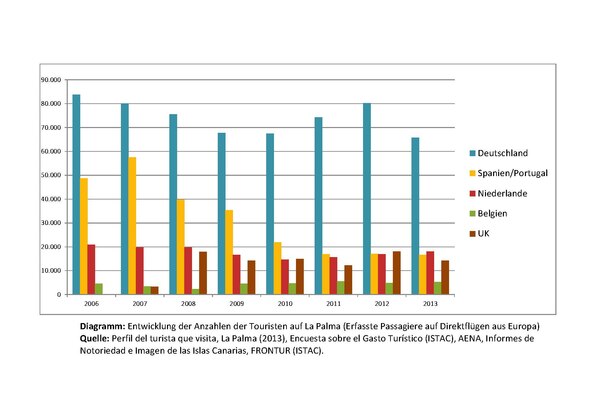

In 2006 the number of guests on La Palma was 111,328 and in 2013 then 104,953. It only accounts for 1% of the total number of guests in the Canary Islands. A survey of the number of guests in 2004 shows a concentration on the west side of the island with around 80%, with around 57% in the places Puerto Naos, La Laguna and Todoque of the municipality of Los Llanos . On the east side of the island (mostly in Los Cancajos) the proportion was 13%. In the other eleven municipalities on the island, the proportion was 19%. The diagram on the right shows the distribution of the number of guests from the various countries of origin in the period 2006 to 2013.

La Palma is traditionally an island for hikers. It is covered by a network of marked hiking trails. A distinction is made between three categories, large route (red marking), small route (yellow marking) and local route (green marking).

Other sporting activities have also been offered since the late 1990s:

- Mountain bike tours

- Horse riding excursions

- Diving centers

- Paragliding

The beaches of Tazacorte , Puerto Naos and Los Cancajos carry the blue flag of the EU and thus meet a high quality standard.

Surveys of visitors in 2013 according to the aspects that made their decision about the travel destination are shown in the table on the right.

| Evaluation criterion | La Palma | Canary Islands |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape / nature | 58% | 20% |

| Sport activity | 27% | 5% |

| Environment / quality | 14% | 7% |

| beaches | 14% | 34% |

| costs | 4% | 14% |

| Quality of the accommodation | 3% | 9% |

Since 1992, the Asociación insular de Turismo Rural Isla Bonita has set itself the task of promoting rural tourism on the island of La Palma. This includes in particular the promotion of rural accommodation and other tourism resources, such as management training, administration of museums and attractions. The association is an amalgamation of around one hundred house renters, small businesses and professional associations.

With EU funding, old houses ( fincas ) are restored in the typical landscape architecture. This type of construction includes, for example, tea wood ceilings , wooden balconies, meter-thick stone walls and the typical brick bench benches under the windows. The restoration work also encourages the local craftspeople. Preservation and rental of the houses should also counteract the rural exodus and contribute to the preservation of the agricultural structure.

traffic

Road network

The road network on La Palma covers about 510 km. All main roads are paved and often very winding due to the landscape. In order to better integrate the remote north of the island economically, a connecting road between Garafía and Barlovento was created at the beginning of 1992 . Remote hamlets can only be reached via dirt or concrete slopes.

An approximately 157 km long road ring surrounds the entire island and consists of two road sections, Carretera General del Norte (LP-1) and Carretera General del Sur (LP-2).

The northern ring road LP-1, about 102 km long, runs from Santa Cruz de La Palma to the north via Puntallana , Los Sauces , Barlovento , Garafía , Puntagorda , Tijarafe and ends in Argual / Los Llanos de Aridane . The northeast part of the LP-1 was expanded and straightened along the entire, very winding route at the beginning of the 21st century, including five tunnels in the La Galga / Puntallana area and the 319 m long arch bridge, Puente de Los Tilos in San Andrés y Sauces belong.

The southern LP-2 ring road with a length of about 55 km runs south from Santa Cruz via Breña Baja , Villa de Mazo , Fuencaliente and ends in Argual / Los Llanos and Tazacorte .

In the middle of the island, the Carretera de la Cumbre (LP-3) runs from east to west with a length of about 26 km and is laid out with two tunnels through the mountain range of the Cumbre Nueva . In the east it connects 3 km from Santa Cruz to the LP-2 and in the west at Tajuya in El Paso it connects again to the LP-2. In 1970 the first tunnel was built through the Cumbre Nueva at a height of 1,100 m and a length of 1,100 m for 62 million pesetas (373,000 euros). The previous only road connection between east and west via the southern tip of the island in Fuencaliente has been shortened considerably. In 2003 the east-west connection of the LP-3 was expanded with a second tunnel for EUR 26.6 million. At 2703 m in length, it is the longest tunnel in the Canary Islands. It runs below the old tunnel at a height of 700 m on the east side and 900 m on the west side of the Cumbre . This means that the entrances are considerably shorter on both sides, which also shortens the total distance between West and East. The new tunnel is driven from west to east, the old tunnel in the opposite direction. For this choice of direction it was essential that medical emergencies can be transported more quickly from the west side to the only island hospital in the east. In an ADAC safety test of 27 tunnels in nine European countries, the Cumbre tunnel was rated “very good”. After the renovation and conversion of the old tunnel from two to one lane in February 2019, the risk of accidents in the tunnel was significantly reduced. While there were an average of 6 accidents per year before the renovation, there were no accidents in the first year after the renovation of the tunnel. Around 4,000 vehicles pass through both tunnels every day.

In the northern part of the island there is another east-west connection, the LP-4 ( Roque Strait ) with a length of about 48 km. It leads up to the astrophysical observatory of Roque de los Muchachos and connects to the LP-1 on the east side in Hoya Grande in Garafía.

The LP-5 ( airport road ) with a length of about 4 km branches off from the LP-2 in Breña Baja and ends at La Palma airport .

The LP-20 is a 4 km long bypass road from Santa Cruz de La Palma. It was inserted into the adjacent mountain range with 5 tunnels (total length of 1831 m) to relieve the capital.

Public transportation

There are regular buses with which all major towns can be reached. Not all lines run every half hour or every hour.

Shipping

The bay of the capital has been used as a port since the island was conquered by the Spaniards. From Santa Cruz de La Palma there are various ferry connections to the neighboring islands and (weekly) to the Spanish mainland, with stops on Lanzarote , Gran Canaria and Tenerife . Since January 2008, the ferry operates El Fortuny society Trasmediterránea on the earlier of the Juan J. Sister served route to Cadiz on the Spanish mainland.

Since 2008 a ferry of the Naviera Armas , the Volcán de Tijarafe, has been operating between Portimão , Portugal via Funchal , Madeira to Santa Cruz de Tenerife, from where you can then reach La Palma. The generously developed port on the west coast in Puerto de Tazacorte was briefly connected to ferry traffic in 2005/2006 with a connection to the island of Tenerife via Santa Cruz de La Palma.

With the takeover of Trasmediterránea by Naviera Armas, the connection from Huelva to the Canary Islands will be handed over to Naviera FRS in order to avoid a monopoly position

Air traffic

La Palma's first airport was built in the municipality of Breña Alta at an altitude of 350 m above sea level with a runway with a length of 1000 m and opened in 1955. He was given the name Buenavista . The airline Iberia operated regular flights from here to Santa Cruz de Tenerife . Because of the proximity of the mountains, there was a problem of changing winds from different directions, repeated fog banks and rainfalls, which in the following years caused more than 15% flight cancellations. These circumstances forced a new planning of the airport location. Buenavista Airport, the runway of which still exists in rudimentary form and is crossed by the main road from the east side of the island to the west side, was closed in 1970 when the new airport opened.

The new airport of La Palma ( IATA code: SPC) was built in the municipality of Mazo along the coastal strip with a runway with a length of 1700 m. Due to the increasing volume of traffic, the runway was extended to 2200 m in 1980 by building a dam in the adjacent sea. Since 1987 it has been the sixth international airport in the Canary Islands, to which several European airlines fly regularly. There are regular connections to the Spanish capital Madrid and to the neighboring islands, which are served by the airlines Iberia , Binter Canarias and Canaryfly. A new airport terminal with a large underground car park was put into operation in 2011 despite the steady decline in passenger numbers, the development of which reached a low point in 2013. Development of passenger numbers:

| year | Passenger numbers |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 943,536 |

| 2004 | 1,015,667 |

| 2007 | 1,207,572 |

| 2010 | 992.363 |

| 2013 | 791,000 |

| 2016 | 1,116,146 |

| 2017 | 1,302,485 |

| 2018 | 1,420,277 |

| 2019 | 1,483,720 |

literature

- Juan Carlos Carracedo, Simon Day: Canary Islands. Classic Geology in Europe 4. Terra, Harpenden 2002, ISBN 1-903544-07-6 , pp. 239-276.

- Irene Börjes, Hans-Peter Koch: La Palma. 7th edition. Müller, Erlangen 2010, ISBN 978-3-89953-456-6 .

- Peter Echevers H .: Stete Canaries. Publisher LULU Press Enterprises, 2011, ISBN 978-1-105-06365-7 .

- Izabella Gawin: La Palma. 7th edition. Reise-Know-How, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-8317-1957-0 .

- Harald Klöcker: La Palma. Travel House Media, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8342-1037-1 .

- Dieter Schulze: La Palma. DuMont Reiseverlag, Ostfildern 2011, ISBN 978-3-7701-9566-4 .

- Rainer Olzem, Timm Reisinger: Geological hiking guide La Palma. RT Geologie Verlag, Aachen, 2nd edition 2018, ISBN 978-3-00-059133-4 .

- Kirsten Lux, Lisa Graf-Riemann: 111 places on La Palma that you have to see. Emons Verlag, 1st edition March 2018, ISBN 978-3-7408-0345-2 .

Web links

- Island Council website (Spanish)

- Video of the eruption of the Teneguía volcano in 1971

- La Palma in the Global Volcanism Program of the Smithsonian Institution (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Gobierno de Canarias: istac - Instituto Canario de Estadística.

- ↑ a b Gobierno de Canarias , istac - Instituto Canario de Estadística, accessed on February 3, 2018.

- ↑ Cabildo Insular de La Palma

- ↑ a b J. C. Carracedo, ER Badiola, H. Guillou, J. de la Nuez, FJ Pérez Torrado: Geology and Volcanology of La Palma and El Hierro. 2001. (online at: digital.csic.es )

- ↑ Juan Carlos Carracedo, Simon Day: Canary Islands . Classic Geology in Europe 4. Terra Publishing, Harpenden 2002, ISBN 1-903544-07-6 , pp. 197 .

- ↑ a b K. Hoerle, JC Carracedo: Canary Islands. Geology, 2009. oceanrep.geomar.de ( Memento of the original from March 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b R. Olzem: The Caldera de Taburiente. rainer-olzem.de

- ^ DG Masson, AB Watts, MJR Gee, R. Urgeles, NC Mitchell, TP Le Bas, M. Canals: Slope failures on the flanks of the western Canary Islands. May 2001. earth.ox.ac.uk ( Memento of the original from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Juan Carlos Carracedo: Geology and volcanology of La Palma and El Hierro, Western Canaries. 2001, Append 2, Geological Map. digital.csic.es

- ↑ Roger Urgeles, Douglas G. Masson, Miquel Clanals, Anthony B. Watts, Tim Le Bas: Recurrent large-scale landsliding on the west flank of La Palma, Canary Islands. In: Journal of Geophysical Research. Vol. 104, 11. 1999 (surveying the debris avalanche on the western flank of La Palma) onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- ^ F. Neukirchen: La Palma - Ruta de los Volcanes & Ruta de la Cresteria (GR 131). May 8, 2012.

- ↑ a b R. Olzem: The San Juan eruption 1949.

- ↑ Earthquake map 2018

- ^ R. Olzem: The Cumbre Vieja

- ↑ JR Ortiz, JB Rubio: La Erupcion del Nambroque (Junio - Agusto de 1949). ( Memento of April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Madrid 1951, earthquake map, p. 81.

- ↑ Earthquake in front of El Hierro - La Palma wobbles with. In: La Palma December 24th, 28th 2013.

- ↑ a b R. Olzem and T. Reisinger: Second round swarm quake , La Palma Aktuell, October 16, 2017; Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ↑ J. Skapski: earthquake swarm on La Palma , Juskis earthquake news 9th and 14th October 2017.

- ↑ Catálogo de terremotos , Instituto Geográfico Nacional ( La Palma - geographical area: Latitud: 28.3 / 29.0; Longitud: -18.1 / -17.5 ).

- ↑ Swarm of earthquakes in Tenerife

- ↑ R. Olzem: The Volcan de Tacande.

- ↑ R. Olzem: The Volcan Jedey or Tajuya. rainer-olzem.de

- ↑ Volcanoes and Dragon Trees. In: Peter Meyer travel guide. (PDF)

- ^ R. Olzem: The volcano de Martín de Tigalate.

- ^ R. Olzem: The eruptions of the San Antonio.

- ^ R. Olzem: The El Charco volcano (Volcán del Charco o Montagna Lajiones).

- ↑ a b c d e f Geografico National, Terremotos más importantes, España, Islas Canarias, 1903–2017 , accessed on December 21, 2017

- ↑ a b The diaries of the San Juan eruption in June and July 1949.

- ↑ Cueva de Las Palomas. Retrieved July 28, 2018 .

- ↑ R. Olzem: The Eruption of Teneguía 1971.

- ↑ Dam break after earthquake on La Palma. In: nachrichten.at , April 17, 2011.

- ↑ Quake in front of La Palma. In: Canaries Express. 17th September 2012.

- ↑ Earthquake of ML3.0 near Barlovento. September 22, 2013.

- ↑ Earthquake on La Palma. In: Canaries Express. February 10, 2014.

- ^ Instituto Geográfico Nacional: Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Retrieved September 19, 2021 (European Spanish).

- ↑ ZEIT ONLINE. Retrieved September 19, 2021 .

- ↑ Noticias e informe mensual de vigilancia volcánica. IGN, December 16, 2021, accessed December 16, 2021 (Spanish).

- ↑ Steven N. Ward, Simon Day: Cumbre Vieja Volcano - Potential collapse and tsunami at La Palma, Canary Islands. (PDF; 768 kB) American Geophysical Union, 2001, accessed on March 14, 2011 .

- ^ Mega-tsunami: Wave of Destruction. In: BBC

- ↑ TU Delft / Jan Nieuwenhuis: New research puts 'killer La Palma tsunami' at distant future. September 20, 2006, accessed July 24, 2016 .

- ↑ La Palma Travel, Climate & Weather

- ↑ a b c d e Rolf Goetz: La Palma. Active holidays on the greenest of the Canary Islands. 5th edition. Peter Meyer travel guide, Frankfurt am Main 2000.

- ↑ H.-P. Koch, I. Börjes: La Palma. Verlag Michael Müller, 1993, ISBN 3-923278-31-4 .

- ↑ Standard Climate Values. La Palma Aeropuerto.

- ^ A b Peter Höllermann: The Impact of Fire in Canarian Ecosystems 1983-1998. University of Bonn, Geography, Archive for Scientific Geography.

- ↑ Incendios forestales espania 2000. ( Memento of the original from June 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Ministerio de Agricultura.

- ↑ El incendio de La Palma continúa activo tras quemar más 2,000 hectáreas. In: El Pais. September 10, 2005.

- ^ Forest fire in the north I to XX. In: La Palma news. September 30, 2005.

- ↑ Forest fire in the Canaries. In: t-online.de