Gran Canaria

| Gran Canaria | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Basic data | |

| Country: |

|

| Province: | Las Palmas Province |

| Surface: | 1,560.1 km² |

| Residents: | 851,231 (2019) |

| Population density : | 531 inhabitants / km² |

| Capital : | Las Palmas de Gran Canaria |

| Website: | www.grancanaria.com |

| Time zone : | Western European Time ( UTC ) |

| Satellite image | |

|

|

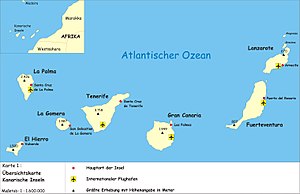

With an area of 1560.1 km², Gran Canaria is the third largest of the Canary Islands , an autonomous community of Spain, after Tenerife and Fuerteventura . The roughly circular island has a diameter of around 50 kilometers and a coastline of around 236 kilometers. In terms of population, Gran Canaria is the second largest island in the Canaries after Tenerife. The capital is Las Palmas de Gran Canaria . In 2019 the island had 851,231 inhabitants.

geography

location

Gran Canaria is an island of the Canary Archipelago and is located 210 kilometers west of the coast of southern Morocco in the Atlantic Ocean , between its larger neighboring islands Tenerife in the west and Fuerteventura in the east. Geographically, the island belongs to Africa , politically to Spain .

nature

Like the entire archipelago, the island is of volcanic origin. The highest point is the 1956 meter high Morro de la Agujereada . The landmark of Gran Canaria is the 1813 meter high Roque Nublo . Although the last eruption on the island was about 2000 years ago, the volcanoes in the north of Gran Canaria are still active, contrary to previous assumptions.

Due to its climatic and geographical diversity as well as its differentiated flora and fauna , Gran Canaria is also described as a "miniature continent ". The island has 14 microclimate zones. Many arid valleys, so-called barrancos , lead from the mountainous interior of the island to the coast. With the rare rainfall, which can then be quite productive, the Barrancos fill up into torrential torrents. In the inhabited areas, the stream valleys were therefore expanded and fortified.

climate

Gran Canaria is in the area of influence of the trade winds , which come in from the northeast in the northern hemisphere. They are forced to ascend on the island mountains and on the northern slopes of the mountains they cause heavy rainfall, mostly in the form of fog . The island is therefore climatically divided into two parts: the wetter north and the drier south. The dryness of the South Island is due to the influence of dry winds from the Sahara are reinforced this as Calima called weather phenomenon ranges from barely noticeable temperature increase to strong winds with sand and a rise in temperature during the day up to 50 ° C and at night up to 40 ° C.

| Gando (Gran Canaria) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Monthly average temperatures and rainfall for Gando (Gran Canaria)

Source: wetterkontor.de

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Like all Canary Islands, Gran Canaria is also badly affected by global warming . This results from the special effects of the climate crisis on island territories. In the Canary Islands, this is associated with a change in the trade winds, a rise in sea level and water temperature, the risk of tropics, longer periods of dryness, haze, but also more intense precipitation. Increased droughts prepare the breeding ground for forest fires .

vegetation

Different vegetation zones have developed in accordance with the regionally varying climate . In the north, laurel forests predominate, while the south is characterized by semi-desert vegetation. There, spurge plants adapted to the drought dominate. Canary spurge is famous for its cactus-like appearance. Bush-high, woody and thick-leaved adder- head species are also widespread . The prickly pear cacti from America have also spread there. The laurel forests are formed by Canary Islands laurel (Laurus novocanariensis) and tree heather . The Canary Bellflower , the character species of the Canary Islands, occurs naturally there. On Gran Canaria, the laurel forests in particular have shrunk to small remnants due to the intensive use by humans. The high-montane regions are occupied by pine forests, which are mainly composed of Canary Islands pines .

Nature symbols

The government of the Canary Islands has established two natural symbols for the island, the Canarian mastiff (Perro de Presa Canario) and the Canary spurge (cardón).

history

- origin of the name

There are various explanations for the origin of the name Gran Canaria . In chapter 32 of the fourth volume of Natural History , the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder quotes the report of an expedition in the 1st century that visited the "Blessed Islands" on behalf of the King of Mauritania Juba II : "... Canaria, so called because of the many large dogs, two of which were brought to Juba. ” Another passage from Pliny refers to a tribe at the foot of the Atlas Mountains : “ The inhabitants of the neighboring mountain forests, filled with elephants, wild animals and snakes of all kinds, would be called Canarians; Their usual food is namely the entrails of dogs and other wild animals. ” An origin of the indigenous people of the island of Gran Canaria from this tribe is not excluded.

First settlement

Archaeological finds prove the presence of humans in various of the Canary Islands at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. However, continuous settlement was only possible from the 3rd century BC. Be proven. The oldest finds on the island of Gran Canaria were dated to the 1st century AD.

The relationship between the Canarian indigenous population and the Berber peoples who lived in North Africa at the time has now been archaeologically and linguistically proven through historical research. Examination of the characters found in the Canary Islands has shown a very high degree of correspondence with the scripts found in Northern Tunisia and Northeastern Geria. Since these Berber peoples were not seafarers, it is assumed that the Romans or the Mauritanians who were under Roman rule found them in the period between the 1st century BC. BC and the 1st century AD to the archipelago. It is believed that u. U. even before this time people from different areas, in several actions, were settled on the islands.

Time of isolated development

Relations between the Canary Islands and the Mediterranean region were broken off with the Roman Empire crisis of the 3rd century . Since the Canarios had no nautical knowledge and no tools to build seaworthy ships, there were no connections between Gran Canaria and the mainland, but also not between the individual islands, on which different cultures developed independently of one another in the following years.

Rediscovery of the Canary Islands in the 14th century

In the 14th century, advances in navigation , the invention of the compass and the astrolabe , and the use of portolans led seafarers from Italian trading centers to the Canary Islands in search of a sea route to India .

The presence of Lancelotto Malocello on the island that was later named after him led to the inscription of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura in the map published by Angelino Dulcert in 1339 , on which the other Canary Islands were not yet entered. The Catalan World Atlas by Abraham Cresques from 1375 already shows all the Canary Islands except El Hierro .

In 1341, King Alfonso IV of Portugal sent a research expedition to the Canary Islands. She brought detailed information about the island of Gran Canaria to Europe.

In the period that followed, various trips to the islands were made from the Mediterranean region, mostly to exchange junk for goat skins and orseille . These undertakings, some of which were carried out by government agencies and some of them privately, also meant that more and more people from the Canary Islands were being sold on the slave markets of the Mediterranean region.

Missionary work by Mallorcan monks

In the middle of the 14th century, a project was developed on Mallorca , the aim of which was to convert the indigenous people of the Canary Islands exclusively through peaceful means. For this purpose, native inhabitants of the islands should be used, who had already adopted the Christian faith. In 1351, twelve women and men were found on Mallorca, who were probably abducted as slaves from Gran Canaria. They were baptized and spoke the Catalan language . They should act as local support for the missionaries of an expedition.

King Peter IV of Aragon showed a great interest in the peaceful conversion of the indigenous people of Gran Canaria. He agreed with the organizers of the missionary work that without a climate of absolute peace, evangelization of the Gentiles would not be possible. In order not to endanger the work of the missionaries, the king pronounced an absolute ban on piracy in the Atlantic for his subjects. The project was approved by Pope Clement VI. With the bull "Coelestis rex regum" of November 7, 1351 he established the diocese of the "Happy Islands", which from 1369 was called the Diocese of Telde . Some shipowners and traders agreed to finance the peaceful expedition, which should also have an economic aspect.

In 1352 the first group of missionaries came to the island of Gran Canaria with the traders. The Mallorcans landed near Gando and began their work, supported by the baptized Canarios they had brought with them. In Telde , the most important settlement of the indigenous people, they built a “house of prayer”. No particular successes are known from missionary work. In the course of time, small chapels were built and crosses were erected in various places. Overall, however, there doesn't seem to have been a targeted plan for the work, so that she lacked a perspective. Contact with Mallorca and later Barcelona was maintained. The last information about the journey of a number of monks who wanted to preach the gospel on the archipelago dates back to 1386.

The ban on attacking the inhabitants of the Canary Islands for the subjects of the Crown of Aragon was apparently observed until the beginning of the 1390s. In 1393 private armed ships broke out from various ports of the kingdoms of the Crown of Castile in a raid on the Canary Islands. Hundreds of indigenous people were enslaved during the Castilian raids and large numbers of goats were captured. It is believed that if the missionaries did not perish during the attacks, they were killed by the remaining Canarios, who saw no difference between the attackers and the monks.

Attempts at submission by Europeans

- Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de La Salle

The relationships between Gadifer de La Salle and Jean de Béthencourt and the indigenous people of the island of Gran Canaria are presented differently in the two versions of the Chronicle Le Canarien . What is certain is that there were two contacts. The conquest of the island was out of the question for the French because of their low military strength compared to the large number of Canarios.

In a contact that took place on an information trip under the command of Gadifer de La Salle, the Canarios exchanged figs and dragon tree blood for fishhooks, iron knives and sewing needles. It is said that there was also a conversation between "Pedro el Canario", the interpreter Gadifer de La Salles and the son of Guanarteme Artamy. 22 French people were killed in an attempt to invade Gran Canaria under the command of Jean de Béthencourt. One of them was the son of Gadifer de La Salles.

- Diego García de Herrera y Ayala

After the right to conquer the island of Gran Canaria had passed to Inés Peraza de las Casas and her husband Diego García de Herrera y Ayala in 1454 through various sales and inheritances , he carried out a military conquest in 1457, during which he established a base in the Bay of Gando, which he secured with a stone tower, the "Torre de Gando". An agreement was reached with the Canarios that allowed the construction of a chapel and a warehouse for trade between Gran Canaria and Lanzarote. In 1459 the Portuguese Diego de Silva y Meneses anchored his fleet in the bay of Gando and took the Torre de Gando by storm. After a letter from the Castilian King Henry IV to his brother-in-law, the Portuguese King Alfonso V , he instructed Diego de Silva in 1461 to give up the occupation of the base and to return it to Inés Peraza and her husband Diego García de Herrera.

On August 16, 1461, near today's city of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, in the presence of the Guanartemes of Telde and Gáldar, a symbolic ceremony of taking possession of the island by Diego García de Herrera took place. An interpreter should make the Canarios understand the importance of the process. Witnesses were the Bishop of Rubicón Diego López de Illescas as well as almost all important representatives of the administration of the previously subjugated islands. In 1462, at a time of harmony between the Castilians, Portuguese and Canarios, a monastery was established in Telde under the auspices of the Bishop of Rubicón, with the consent of the indigenous people.

During 1465, preparations began for a fortified tower in the Telde area. Another building was erected near the defense tower as a kind of warehouse for supplies of the garrison and goods that were traded with the indigenous people. When the commander did not stop or punish the rapes of Canarian women and raids by soldiers of the garrison against the Canarios and their herds of cattle, the Canarios probably attacked the Torre de Gando in 1474 and set it on fire. Most of the garrison crew was killed. This ended the presence of the representatives of the "Lords of the Canary Islands" (the official title of Inés Peraza and Diego García de Herrera) on the island of Gran Canaria.

Conquest by the Crown of Castile

- Assumption of the rights of conquest by the Catholic Kings

In 1475, the residents of Lanzarote complained to Queen Isabella I and King Ferdinand V about the rule of Diego de Herrera and Inés Peraza. They demanded that the island be placed directly under the Crown. Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand appointed a "Juez Pesquisidor" (examining magistrate) on November 16, 1476, who was supposed to determine which property and conquest rights existed in the Canary Islands. As a result, it was established that Diego de Herrera and Inés Peraza were entitled to property rights and the right to rule over the four islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, La Gomera and El Hierro, as well as the right to conquer the islands of Gran Canaria, Tenerife and La Palma. Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand feared that Portugal might try to occupy the islands that had not yet been conquered as part of the War of the Castilian Succession . The Crown of Castile agreed with Diego de Herrera and Inés Peraza the assignment of the rights of conquest for Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife against financial compensation. The agreement was recorded on October 15, 1477.

- First phase of the conquest

During the war against Portugal, the Castilian state finances did not allow spending on conquests in the Atlantic. This is why Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand used the capitulación system for the first time to finance the conquest of the island of Gran Canaria . In a first capitulación of May 1478, the bishop of Rubicón, Juan de Frias was hired as the financier and the dean Juan Bermúdez and Juan Rejón as the head of the conquest. A large part of the bishop's funds came from income generated by Pope Sixtus IV granting donors of large sums for the conversion of unbelievers in the Canary Islands indulgence from their penalties.

At the end of May 1478 the Castilian troops reached the northeast coast of Gran Canaria. June 24th is seen as the founding day of the field camp of Las Palmas , the origin of today's island capital. There were differences of opinion between Juan Bermúdez and Juan Rejón about the military procedure for the conquest. The Canarios did not get involved in an open battle, but fought the Castilians in a kind of guerrilla war . Then Juan Rejón responded with a scorched earth tactic . As a result of the resistance of the natives and the internal disputes in the leadership of the Castilian troops, the conquest progressed very slowly. This prompted Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand to send Pedro de Algaba to the island as governors. He should mediate between the military leaders and take over civil administration. Pedro de Algaba was unable to resolve the dispute in the Castilian leadership. He sent Juan Rejón to the Iberian Peninsula so that the royal court could decide its future. Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand stated that Juan Rejón had not misbehaved. He was confirmed in his old position on the island and returned to Gran Canaria in May 1480 with reinforcements. There he had Pedro de Algaba arrested on charges of cooperation with the Portuguese. After a short trial, he was found guilty and executed. Juan Bermudez, against whom Juan Rejón could not proceed because he was under ecclesiastical jurisdiction, was expelled to Lanzarote.

- Second phase of the conquest

Before Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand found out about the execution of Pedro de Algabas, they reached an agreement with the chamberlain Alonso de Quintanilla and the merchant Pedro Hernández Cabrón that they should provide a newly appointed governor of the island with the necessary funds that the needed to conquer the island of Gran Canaria. The new governor Pedro de Vera was given far-reaching powers, which included both military command and civil administration after the conquest. He reached the island in mid-July 1480 with a hundred crossbowmen and a large amount of provisions. In December of the same year, Pedro de Vera sent Juan Rejon to the Spanish peninsula where he was supposed to justify his action in the Pedro de Algaba case before the royal court.

After further troop reinforcements arrived on Gran Canaria at the end of 1480 and in the course of spring 1481, Pedro de Vera organized a large-scale attack on the north of the island. In the vicinity of Arucas near the Barranco de Tenoya there was a battle in which Doramas, one of the most respected military leaders of the Canarios, was killed. As an additional base, the Castilian troops built a fortification on the west side of the island near Agaete . Alonso Fernández de Lugo was appointed first fortress commander. From Agaete he was able to capture the Guanarteme tenesor Semidán in an attack on Gáldar in February 1482 . This played an important role as mediator between the Castilians and the Canarios in the further subjugation of the islands of Gran Canaria. After conquering large areas in the south of the island, Tenesor Semidán was able to convince the Canarios in negotiations that resistance to the acceptance of the Christian faith and submission to the supremacy of the Crown of Castile was pointless. The date for the final abandonment of the struggle of the Canarios, who had withdrawn to the Fortaleza de Ansite, is April 29, 1483. In January 1484 the troops that had participated in the conquest were disbanded.

Consequences of the conquest

- Population loss

In the course of the conquest, the number of indigenous people living on the island was reduced to around 15%. The number of Canarios killed in battle must have been very high in view of the use of firearms by the Castilians. The exact number of deaths cannot be determined. In the course of the armed conflict, but also after the conquest, native inhabitants were deported to mainland Spain. They were distributed to different places in Andalusia. A large part of them settled in Seville, where they lived in poor conditions. Others took part in the conquest of the islands of La Palma and Tenerife and settled there on the land allocated to them.

- Repopulation

After the conquest, a new society emerged on Gran Canaria made up of people of different origins. The Catholic religion and the Castilian language formed the prerequisites for being accepted in this society. The conquerors, like the settlers recruited to work on the land, came primarily from the lands of the Crown of Castile. The skilled workers for sugar production were recruited in Madeira . Through campaigns on the nearby African coast, black Africans were brought to the island as work slaves for the sugar factories.

- Land and water distribution

A large number of the conquerors took part in the company on the promise to be taken into account in the distribution of land and water usage rights. In the distribution of real estate and water rights, one criterion was which personal or financial performance the recipient had contributed to the success of the company. On the other hand, the financial performance of the new owners also played a decisive role. When assigning land for sugar production, large investments in processing facilities were necessary. In distributing land and water rights in Gran Canaria, the Crown granted allotments to eminent courtiers and members of the commercial capital. In order to develop the expansion of agriculture and a money-based economy, the island needed the participation of private capital. This was particularly represented by Genoese and Catalans .

Demographics

| year | Residents | Inhabitants / km² |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 741.161 | 475.07 |

| 2001 | 755.489 | 484.26 |

| 2002 | 771.333 | 494.41 |

| 2003 | 789.908 | 506.32 |

| 2004 | 790.360 | 506.61 |

| 2005 | 802.247 | 514.23 |

| 2006 | 807.049 | 517.31 |

| 2007 | 815.379 | 522.65 |

| 2008 | 829,567 | 531.74 |

| 2009 | 838.397 | 537.40 |

| 2010 | 845.676 | 542.10 |

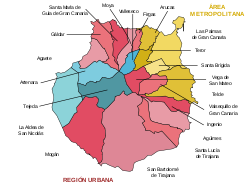

In terms of population, Gran Canaria is the second largest island in the Canaries after Tenerife. A total of 843,000 people live on the island, of which 49.9 percent are men and 50.1 percent are women (as of 2017). 45 percent of them live in the capital Las Palmas (378,000), the largest city in the Canary Islands. Cities with high populations are Telde (102,000), Santa Lucía de Tirajana (70,000), San Bartolomé de Tirajana (54,000), Arucas (37,000), Agüimes (31,000) and Ingenio (30,000).

Between 2006 and 2007 the population increased by 1% (+8,330). Mogán recorded the greatest increase (+ 11.9%).

Administration and politics

Since the Ley de Cabildos (Cabildo law) came into force in 1912, the local administrative authority has been the so-called Cabildo Insular , which performs its own tasks below the level of the provinces and above the level of the Municipios (German: city administrations). José Miguel Pérez García of the PSOE has been president of this authority since July 2007 . The island is divided into 21 Municipios:

Transport and infrastructure

Ports

The Puerto de la Luz in Las Palmas is the main port on the island. In 2016, 23.9 million tons of cargo were handled and 1,286,466 passengers were handled, including 1.1 million cruise passengers. The private shipping companies Fred. Olsen Express and Naviera Armas offer regular ferry connections to Tenerife , Fuerteventura , Lanzarote , La Palma and El Hierro as well as Madeira . Another port that connects Gran Canaria with Tenerife is Puerto de las Nieves in the fishing town of the same name near Agaete.

Airport

Gran Canaria International Airport is located about 18 kilometers south of Las Palmas, on the GC-1 motorway , between Telde and Ingenio. In 2019, 126,452 aircraft movements were counted, 13,261,405 passengers were handled and around 126,452 tons of cargo were handled.

Streets

Gran Canaria has an extensive road network. The most important motorway, the GC-1 (Autopista del Sur) , runs along the east and south coast of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria past the international airport to the tourist center of Maspalomas and on to Puerto de Mogán . The GC-2 (Autovía del Norte) runs on the north coast, with one interruption, from Las Palmas to Agaete . The GC-3 (Circunvalación de Las Palmas) serves as a bypass road and connects the two main roads southwest of Las Palmas over a length of 13 kilometers. The interior of the island is accessed by country roads, which are often winding and steep due to the geographical conditions.

Public transportation

railroad

The Cabildo de Gran Canaria decided in May 2008 to set up a 48-kilometer train connection from Las Palmas to Playa del Inglés. Ferrocarriles de Gran Canaria SA was founded as the supporting company . The planned travel time from Las Palmas to Maspalomas is around 15 minutes. Nine intermediate stops are planned between Las Palmas and Maspalomas, including a stop at the airport . The construction of the railway line should increase the number of journeys in public transport by a factor of five. In 2018, the preparatory work for the construction was finished, so that only the government of the Canary Islands has to approve the construction.

Buses and trams

The private company Global operates a dense network of regular buses (called “guaguas” by the locals). The Guaguas Municipales company , which operates the public city buses, has been owned by the city of Las Palmas since 1979 .

A tram operated in the capital Las Palmas from 1890 to 1937 . This was the first means of rail transport in the Canary Islands.

tourism

Every year around 2.8 million people visit Gran Canaria, especially the tourist centers in the south of the island with the towns of Maspalomas, Playa del Inglés and San Agustín . Since 1996, the number of tourists from abroad has been more than 2.6 million annually. In the years 1999-2001 more than 3 million tourists were counted. There was a decrease to around 2.4 million in 2009 and 2010.

The vacationers generate a turnover of around 2.5 billion euros. Gran Canaria is particularly popular as a travel destination in Central and Northern European countries. In 2012 around 29% of holidaymakers came from Scandinavia; 32% from Germany, Austria, Switzerland and 21% from Great Britain and Ireland. Gran Canaria is especially popular in winter because of the mild Canarian climate . But even in the summer months, the climate on the island is mostly moderate. This is due to the cold Canary Islands current . Because of the daytime temperatures between 18 and 26 degrees that prevail almost all year round, the Canaries are also called islands of eternal spring. The island is a popular holiday destination for gays and lesbians, especially the places Playa del Inglés and the subsequent Maspalomas.

Every year at the end of November the International Sports Festival Flower Gran Canaria takes place in Maspalomas .

Resorts

Most of the tourist accommodation is in the south of the island. The largest resorts are: Bahía Feliz - San Agustín - Playa del Inglés - Maspalomas - Puerto Rico - Mogán - Puerto de Mogán - Meloneras

Large parts of the interior of the island have a small proportion of tourist accommodation, but benefit from day and excursion tourism, for example: Fataga - Puerto de las Nieves (near Agaete ) - Agüimes - Arucas - Firgas - Gáldar - Las Palmas - Moya - San Bartolomé de Tirajana - San Nicolás de Tolentino - Santa Brígida - Santa Lucía de Tirajana - Tejeda - Telde - Teror - Valleseco - Valsequillo

Attractions

- The fishing town of Puerto de Mogán , also known as the Venice of the South

- Maspalomas dunes

- Palmitos Park - palm and animal park that was almost completely destroyed in a fire in 2007 and reopened in summer 2008

- The drinking water dam in the Barranco de Arguineguin above Maspalomas in the hinterland

- The archaeological open-air museum Mundo Aborigen in the Barranco de Fataga

- Cave village in the Barranco de Guayadeque near Agüimes

- The Museo y Parque Arqueológico Cueva Pintada in Gáldar

- The "Cruz de Tejeda", a lookout point at the summit with a view of the "Pico del Teide"

- Dedo de Dios (finger of God) rock needle in Puerto de las Nieves (part of the rock was torn off by the tropical storm Delta on November 28, 2005)

- Cenobio de Valerón , over 290 caves carved into the tufa by the indigenous people

- Botanical garden Jardín Botánico Canario Viera y Clavijo (short: Jardín Canario) in Tafira Alta

- Cactualdea cactus park near San Nicolás de Tolentino (west coast)

- The Bandama Natural Park with the Caldera de Bandama explosion cauldron

- The 80 m high monolith Roque Nublo

- The place Teror with typical Canarian architecture

- The place Arucas with an imposing basalt stone church

- Artenara Caves

- The capital Las Palmas with the port area and the historic old town Vegueta

- The places of San Bartolomé de Tirajana and Fataga in the interior

Web links

- Cabildo de Gran Canaria - official website (multilingual)

- Gran Canaria in the Global Volcanism Program of the Smithsonian Institution (English)

swell

- ↑ La tecnología destrona al Pico de las Nieves como techo de la isla

- ↑ http://iocag.ulpgc.es/blog/effects-climate-change-islands

- ↑ Ley 7/1991, de 30 de abril, de símbolos de la naturaleza para las Islas Canarias , accessed on August 18, 2012

- ↑ Cajus Plinius Secundus: The natural history of Cajus Plinius Secundus: translated into German and annotated (Chapters 1-11) . Ed .: GC Wittstein. Gressner & Schramm, Leipzig 1881, p. 487 f .

- ↑ Cajus Plinius Secundus: The natural history of Cajus Plinius Secundus: translated into German and annotated (Chapters 1-11) . Ed .: GC Wittstein. Gressner & Schramm, Leipzig 1881, p. 358 .

- ^ Antonio Tejera Gaspar: Los libio-beréberes que poblaron las islas Canarias en la antigüedad . In: Antonio Tejera Gaspar, María Esther Chávez Álvarez, Marian Montesdeoca (eds.): Canarias y el África antigua . 1st edition. Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria, Tenerife, Gran Canaria 2006, ISBN 84-7926-528-0 , p. 91 (Spanish).

- ↑ Pablo Peña Atoche: Excavaciones Arqueológicas en el sitio de Buenavista (Lanzarote) - Nuevos datos para el estudio de la Colonización protohistórica del archipiélago . In: Gerión . tape 29 , no. 1 , 2011, ISSN 0213-0181 , p. 59 (Spanish, [1] [accessed May 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Pablo Peña Atoche: Las Culturas Protohistóricas Canarias en el contexto del desarrollo cultural mediterráneo: propuesta de fasificación . In: Rafael González Antón, Fernando López Pardo, Victoria Peña (eds.): Los fenicios y el Atlántico IV Coloquio del CEFYP . Universidad Complutense, Centro de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos, 2008, ISBN 978-84-612-8878-6 , pp. 323 (Spanish, [2] [accessed May 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Felipe Jorge Pais Pais, Antonio Tejera Gaspar: La Religón de los benahoaritas . Fundación para el Desarrollo y la Cultura Ambiental de La Palma, Santa Cruz de La Palma 2010, ISBN 978-84-614-5569-0 , p. 17 (Spanish).

- ↑ Renata Ana Springer Bunk: The Libyan-Berber inscriptions of the Canary Islands in their rock painting context . Köppe, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-89645-942-8 , pp. 21 .

- ↑ Felipe Jorge Pais Pais, Antonio Tejera Gaspar: La Religón de los benahoaritas . Fundación para el Desarrollo y la Cultura Ambiental de La Palma, Santa Cruz de La Palma 2010, ISBN 978-84-614-5569-0 , p. 17 (Spanish).

- ↑ Pablo Peña Atoche: Las Culturas Protohistóricas Canarias en el contexto del desarrollo cultural mediterráneo: propuesta de fasificación . In: Rafael González Antón, Fernando López Pardo, Victoria Peña (eds.): Los fenicios y el Atlántico IV Coloquio del CEFYP . Universidad Complutense, Centro de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos, 2008, ISBN 978-84-612-8878-6 , pp. 324 f . (Spanish, [3] [accessed May 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Juan Francisco Navarro Mederos: The original inhabitants (= everything about the Canary Islands ). Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria, o.O. (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria / Santa Cruz de Tenerife) 2006, ISBN 84-7926-541-8 , p. 35 .

- ↑ Eduardo Aznar: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape 42 . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 11 (Spanish).

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Ulbrich: The discovery of the Canaries from the 9th to the 14th century: Arabs, Genoese, Portuguese, Spaniards . In: Almogaren . No. 20 , 2006, ISSN 1695-2669 , pp. 84 f . ( [4] [accessed February 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: El obispado de Telde . Misioneros mallorquines y catalanes en el Atlántico. Ed .: Ayuntamiento de Telde Gobierno de Canarias. 2nd Edition. Gobierno de Canarias, Madrid, Telde 1986, ISBN 84-505-3921-8 , pp. 46 (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: El obispado de Telde - misioneros mallorquines y catalanes en el Atlántico . Ed .: Ayuntamiento de Telde Gobierno de Canarias. 2nd Edition. Gobierno de Canarias, Madrid, Telde 1986, ISBN 84-505-3921-8 , pp. 52 f . (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: El obispado de Telde - misioneros mallorquines y catalanes en el Atlántico . Ed .: Ayuntamiento de Telde Gobierno de Canarias. 2nd Edition. Gobierno de Canarias, Madrid, Telde 1986, ISBN 84-505-3921-8 , pp. 103 (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: El obispado de Telde . Misioneros mallorquines y catalanes en el Atlántico. Ed .: Ayuntamiento de Telde Gobierno de Canarias. 2nd Edition. Gobierno de Canarias, Madrid, Telde 1986, ISBN 84-505-3921-8 , pp. 115 (Spanish).

- ↑ Eduardo Aznar: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape 42 . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 125 (Spanish).

- ↑ Eduardo Aznar: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape 42 . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 16 (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 98 (Spanish, [5] [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 41 ff . (Spanish).

- ↑ Mariano Garcia Gambin: Las cartas de los primeros nombramiento de Gobernadores de la política CanariasExpresión de los Reyes Católicos centralizadora de . In: Revista de historia canaria . No. 182 , 2000, pp. 42 (Spanish, unirioja.es [accessed June 20, 2016]).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 54 (Spanish).

- ↑ Marta Milagros de Vas Mingo: Las capitulaciones de Indias en el siglo XVI . Instituto de cooperación iberoamericana, Madrid 1986, ISBN 84-7232-397-8 , p. 24 (Spanish).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 71 (Spanish).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 122 (Spanish).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 105 (Spanish).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 167 ff . (Spanish).

- ^ Antonio M. Macías Hernández: Nobles, campesinos y burgueses . In: Antonio de Béthencourt Massieu (ed.): Historia de Canarias . Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 1995, ISBN 84-8103-056-2 , p. 204 ff . (Spanish).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 118 (Spanish).

- ^ Antonio M. Macías Hernández: Nobles, campesinos y burgueses . In: Antonio de Béthencourt Massieu (ed.): Historia de Canarias . Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 1995, ISBN 84-8103-056-2 , p. 209 (Spanish).

- ↑ ISTAC: Population of Gran Canaria. January 1, 2007, accessed November 3, 2008 (Spanish).

- ^ Tráfico Marítimo Ultimo Año. In: palmasport.es. Las Palmas Port Authority, archived from the original on September 4, 2018 ; Retrieved on September 4, 2018 (The original page is continuously updated. The information in the article is based on the archived version.).

- ↑ Annual statistics 2019 from the Spanish airport operating company AENA (PDF)

- ^ Railway for Gran Canaria. In: dmm.travel. Verlag für Mobility (VfM) GmbH & Co. KG, March 7, 2009, accessed on May 15, 2009 .

- ↑ Nepi's Gran Canaria: Gran Canaria by train (route is being built). Retrieved June 19, 2015 .

- ↑ Nepi's Gran Canaria: New millions for rapid transit. Retrieved June 19, 2015 .

- ↑ Nepi's Gran Canaria: Overview of all articles on the subject of express trains in Gran Canaria. Retrieved June 19, 2015 .

- ↑ Canaryo.net: Planning work on the railway project in Gran Canaria finished

- ↑ All Global bus routes in Gran Canaria. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010 ; Retrieved November 13, 2008 .

- ^ History of the Guaguas Municipales. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 4, 2008 ; Retrieved November 13, 2008 (Spanish).

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento of the original from March 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Visitor numbers in Gran Canaria; in Gran Canaria Olé, issue 38; February 2013

- ↑ Spain - Half a million gays visited Gran Canaria in 2014. In: queer.de. February 18, 2015, accessed March 7, 2019 .

Coordinates: 27 ° 58 ′ N , 15 ° 36 ′ W