Lanzarote

| Lanzarote | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Basic data | |

| Country: |

|

| Province: | Las Palmas |

| Geographical location: | 29 ° 3 ′ N , 13 ° 37 ′ W |

| Time zone : | GMT ( UTC ± 0) |

| Surface: | 845.94 km² |

| Residents: | 162,500 (2020) |

| Population density : | 192.09 inhabitants / km² |

| Capital : | Arrecife |

| President of the island government: | María Dolores Corujo Berriel ( PSOE ) |

| Website ( Cabildo de Lanzarote ): | cabildodelanzarote.com |

| Location of Lanzarote within the Canary Islands | |

|

|

| Satellite image | |

Lanzarote [ ˌlansaˈɾote , ˌlanθaˈɾote ] is the northeasternmost of the eight inhabited Canary Islands that make up one of Spain's 17 autonomous communities in the Atlantic Ocean .

Lanzarote is around 140 kilometers west of the Moroccan coast and around 1000 kilometers from mainland Spain . The main traffic connection is Arrecife Airport .

In 1993, Lanzarote was the first island to be fully declared a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO .

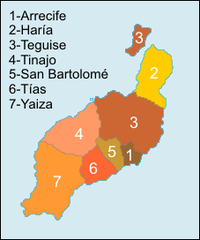

administration

Lanzarote belongs to the Spanish province of Las Palmas of the autonomous community of Canarias and is divided into the seven municipalities of Arrecife , Haría , San Bartolomé , Teguise , Tías , Tinajo and Yaiza . The capital of Lanzarote is Arrecife, the national language is Spanish .

Lanzarote has an island council / government, the Cabildo Insular de Lanzarote , of which María Dolores Corujo was elected by the PSOE as president in the local elections on May 26, 2019 . The 23 seats of the Island Council have since been distributed as follows:

- 9 seats: Partido Socialista Obrero Español

- 8 seats: Coalición Canaria - Partido Nacionalista Canario

- 4 seats: Partido Popular

- 3 seats: Podemos Equo-sí se puede

geography

Lanzarote measures around 58 kilometers from north ( Punta Fariones ) to south ( Punta Pechiguera ) and 34 kilometers in the largest east-west extension. With an area of 845.94 km², the island has an area of 11.29 percent of the total area of all Canaries. South of Lanzarote, separated by the 11.5 kilometers wide La Bocayna strait , is the island of Fuerteventura , and in the north about 1 kilometer away is the Chinijo archipelago with the small islands of La Graciosa , Montaña Clara , Alegranza , Roque del Oeste and Roque del Este . Of the total of 213 kilometers of coastline, 10 kilometers are sandy and 16.5 kilometers are pebble beaches, the rest is rocky. There are two mountain ranges on the island. In the north of the island the Famara massif rises with the summit Peñas del Chache to 671 m , and in the south of the Los Ajaches to 608 m . To the south of the Famara massif is the El Jable sand desert , which separates the Famara massif from the so-called fire mountains ( Montañas del Fuego ) of the Timanfaya National Park . In the Timanfaya area, strong volcanic eruptions last occurred from 1730 to 1736 and 1824 , which buried large parts of the most fertile farmland and several villages and farms with a total of around 420 houses. The rest of the island is characterized by a hilly landscape with striking volcanic cones .

climate

Lanzarote is located in the Passat Zone , which means that fresh winds blow from north to northeast on the island all year round. Lanzarote has a mild and arid climate all year round , as the trade winds usually do not rain down on the relatively flat island. The air temperature is the annual average at 20.5 ° C . The monthly average is 16.9 ° C in January and 24.7 ° C in August. The water temperature of the Atlantic Ocean fluctuates between 17 ° C in winter and 22 ° C in summer due to the swelling of cold deep water off the northwest African coast and the Canary Islands .

Climate table

| Lanzarote | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Lanzarote

Source: wetterkontor.de

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rainfall

With 112 millimeters of rainfall per year, Lanzarote is the driest of the Canary Islands. 85 percent of the precipitation falls from January to March. The average relative humidity is 70 percent. In the mountainous north, rainfall of up to 300 millimeters per year can fall significantly more than in the south. There, the north-eastern trade winds coming from the Atlantic can hit the Famara massif with the highest point of 671 m , which is in the lowest part of the condensation zone . The trade winds accumulate only when there is strong circulation and are forced to rise. The humid Atlantic air cools down by 1 K (1 ° C) per 100 meters ( dry adiabatic cooling ) during the ascent . However, since the cooler air can store less water vapor, but the absolute amount of water vapor remains the same, the water vapor condenses when the saturation limit is reached. Clouds or fog arise . The moisture from the clouds is sufficient to practice agriculture in the form of dry fields in this area (see section Agriculture ). The humidity is also sufficient to create a sight unusual for Lanzarote in the valley of 1000 palm trees, in the area around Haría . With the many palm trees (Canarian date palm, Phoenix canariensis ) and the lush vegetation, especially in spring, you will find a green oasis in this valley on the otherwise very little vegetation island.

Water supply

The water supply has always been a problem on the island with little precipitation. Originally, the precipitation was collected by means of large paved areas ( Eras or Alcogidas ) and stored in large cisterns ( Ajibes ). These systems have made human life possible on Lanzarote for centuries. With the introduction of seawater desalination plants and the availability of tap water, the Eras and Ajibes have lost their importance almost everywhere. The eras of paved areas with their sometimes idiosyncratic exterior shapes on the mountain slopes of Lanzarote still characterize the landscape in some regions today. As buildings, they shape the landscape and are of cultural and historical importance.

In the 1950s, around 25 percent of the water requirement was covered by water-bearing tunnels in the Famara massif. Four of the seven water-bearing tunnels were used in 1950.

As a result of the tourism that began in the 1950s , the need for water in Lanzarote rose sharply, especially since on average every tourist in the Canary Islands consumes around 230 liters of water per day, whereas the locals only use 138 liters. The sinking groundwater levels due to the increasing extraction led to the pressurization of heavier seawater and thus to a salinization of the groundwater. Therefore, water had to be transported to the island by tankers from the neighboring islands of Tenerife and Gran Canaria .

In 1964, the first municipal seawater desalination plant east of Arrecife went into operation (Lanzarote I), which was later expanded (Lanzarote V) and supplemented by plants in Punta de Los Vientos (Lanzarote III and Lanzarote IV) and Yaiza (Lanzarote II). Because of its high energy requirements, seawater desalination brings with it considerable ecological problems. The demand for electricity is reduced by reverse osmosis , but it can only be partially covered by wind turbines and solar systems ; the geothermal energy that is very close to the surface on the island has not yet been used for this purpose. The extraction of fresh water on Lanzarote therefore still requires the import of petroleum.

In the 1970s, a project to store rainwater in a reservoir, the Presa de Mala near Mala, failed.

Weather phenomena

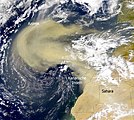

On Lanzarote as well as on the other Canary Islands there can be a special weather situation , called Calima , several times a year . It occurs when dust particles are transported to great heights over the Sahara by sand storms and strong thermals . With southeasterly winds these aerosols are then transported far out to the Atlantic. During such weather conditions the visibility on the island can decrease to a few 100 meters. The air is then enriched with dust and the sky can appear in an unreal shade of red to brown. During these weather conditions, temperatures can rise to over 40 ° C at times. The high content of aerosols in the air can mean that air traffic has to be stopped or diverted, as due to the topography of Lanzarote, planes can only approach Arrecife Airport (ACE) from the north with sufficient pilot visibility. This hot southeast wind is also called Levante by the locals .

geology

Lanzarote is an island of volcanic origin. Around 36 million years ago, repeated undersea volcanic eruptions began to form the island's base. These eruptions originated as manifestations of intraplate volcanism caused by continental drift and hotspot volcanism. More on this in the article Canary Islands . 15.5 million years ago Lanzarote grew above the sea surface. The Lanzarote Geodynamic Laboratory researches the associated terrestrial, oceanic and atmospheric phenomena.

The surface of Lanzarote was created by four main volcanic phases, most of which are proven by potassium-argon dating :

- Phase 1 : Here the Famara massif in the north, the second highest mountain range Los Ajaches, the eastern part of the Rubicón plain, and individual volcanoes near Tías in the southeast. This eruption phase took place 15.5 to 3.8 million years ago, interrupted by times that were marked by erosion.

- Phase 2 : Here the western part of the Rubicón plain with the Montaña Roja, some volcanoes in the interior of the island, as well as the Montaña de Guanapay near Teguise and the Atalaya near Haría in the north emerged. This eruptive phase took place around 2.7 to 1.3 million years ago.

- Phase 3 : There were up to 100 eruption centers here, which were spread over the entire island about 730,000 to 240,000 years ago.

- Phase 4 : A distinction is made here: The first eruption phase caused the 30 square kilometer Malpaís de la Corona and thus the Cueva de los Verdes to arise in the northeast of Lanzarote a good 3,000 years ago . The second eruption phase occurred from 1730 to 1736 and 1824 , with over 23 percent of Lanzarote's area being covered with around three to five cubic kilometers of new lava from around 30 new volcanic craters. This target is both in terms of duration, eruptierter Lavamengen and composition of the lavas (including olivine - basalt ) in historical times world one of the most important, after the eruptions of Eldgjá (around 934) and the Laki (1783-84) in Iceland . Today the Timanfaya National Park extends over a large part of this area . The geologist Leopold von Buch visited the island in 1814. He recognized that most of the eruptions came from a single long crevice, which is now estimated to be at least 14 km, and quoted in 1819 in a lecture at the Prussian Academy of Sciences and in 1825 in a review from the eyewitness account of Pastor Andrés Lorenzo Curbelo .

history

First settlement

Pieces from the Buenavista site, dated using the radiocarbon method, point to the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. BC as the beginning of the colonization of the island of Lanzarote by the Phoenicians. The combination of fertile soil and temporary water points led to the fact that some places were viewed as preferred areas for the settlement of a population who could make a living from livestock and agriculture. In the beginning it must have been a state-financed company, a colonization process for geo-strategic reasons and for the agricultural use of the raw materials of the area. It can be assumed that groups of North African Paleo-Berbers who were in contact with the Phoenician culture of North Africa were the first settlers. The colonization process must have occurred after the 6th century BC. Along with the expansion of Carthage. At the turn of the ages the beginning of extensive exploitation of the island's area can be observed. The basis was the island model of agricultural production with the goal of goods such as B. to produce purple , sea salt and garum , which were of interest to the Roman culture. Pliny the Elder refers to the relationship between the Mauritanian king Juba II , who was under Roman rule, and the Canary Islands. It is believed that more settlers came to the islands from the area north and south of the Strait of Gibraltar at this time . The presence of the Roman or Romanized sailors on the islands ended after the political and economic crisis of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century AD when part of the Mauretania Tingitana province was also abandoned. This led to the end of purple workshops and salt pans on the Moroccan Atlantic coast. At this time, the Canary Islands became more and more isolated. This finally meant that the indigenous people, who had no knowledge of shipbuilding and nautical science, could not even maintain connections between the islands.

Time of isolated development

An independent culture developed on the island of Lanzarote in the following period. The native inhabitants of the Canary Island of Lanzarote were the Majos . Since they did not leave any written evidence themselves, the cultures of the Old Canary Islands are only known through archaeological finds and reports by European seafarers from the 14th and 15th centuries.

Rediscovery of the Canary Islands in the 14th century

In the 14th century there was significant advancement in European shipping through the use of the compass , astrolabe and portolans . Especially the seafarers of the Italian trade centers were looking for a new way to India . The area along the west coast of Africa was rediscovered. As part of this development, Lancelotto Malocello probably came to the island of Lanzarote at the beginning of the 14th century . It is believed that he established a trading post there. In the report Le Canarien about the subjugation of the island of Lanzarote, which was written at the beginning of the 15th century, a "castle" is called that "Lancelot Maloisel" built. In a portolan by the Mallorcan cartographer Angelino Dulcert from 1339, the islands of Lanzarote, Lobos and Fuerteventura are drawn in the correct position. Lanzarote is known as the "Insula de lanzarotus marocelus" and the area is filled with the coat of arms of Genoa , the home of Lancelotto Malocellos.

In the course of the 14th century, a large number of expeditions by Genoese , Portuguese , Mallorcans, Catalans and Andalusians came to the island to catch people who they sold as slaves in the markets in the Mediterranean region and on the Spanish peninsula . One of the attacks, that of Gonzalo Pérez Martel, lord of Almonaster, on the population of Lanzarote in 1393 is reported in the chronicle of Henry III. that seafarers landed on the island and took the king, queen and another 160 people as prisoners.

Submission of the majos by Europeans

On May 1, 1402, an expedition headed by Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de la Salle to the Canary Islands started in La Rochelle . The aim of the company was to create a base for the extraction and export of the lichen Roccella canariensis, which was processed into a red dye in Europe. So that the trade base could work independently of the supply from Europe, French farmers and artisans were to be settled as colonists. The participants in the expedition were therefore, in addition to a few soldiers, farmers and artisans, some of whom had also taken their wives with them. The conversion of the natives to Christianity was a goal of Béthencourt, which he took very seriously. For this reason, the clergy Jean Le Verrier and Pierre Bontier accompanied the expedition. Together they wrote the original version of the Chronicle Le Canarien, which depicts the expedition. At the end of July 1402, the ship reached the south coast of the island of Lanzarote. About 60 people were on board at the time, including two former slaves who had been abducted from Lanzarote to Europe. You should act as a translator and mediator. There was no hostility on landing. Jean de Béthencourt managed through negotiations with Guadafrá, the head of the Majos , to conclude a contract that allowed him to build a fortification on the island. In return, he was supposed to protect the majos from slave hunters. The fortification, the Castillo de Rubicón , consisted of a defense tower , fountain, a few houses and a church dedicated to Saint Martial of Limoges .

After a short stay on the island, it became clear to the leaders of the expedition that the equipment and personnel for the project, especially if it was to be expanded to the other islands, were inadequate. Therefore, Jean de Béthencourt traveled to Castile around there, through the mediation of a relative, Robín de Bracamonte, who was the ambassador of the King of France at the Castilian court, supported by King Henry III. to obtain. A prerequisite for the aid was that Jean de Béthencourt submitted to the supremacy of the Castilian king and took a vassal oath on him. As a result, the expedition started in the Canary Islands was a company of the Crown of Castile. Jean de Béthencourt received the title of "Señor de las islas Canarias" (Lord of the Canary Islands).

With the bull "Romanus pontifex" Pope Benedict XIII. on July 7, 1404 the Diocese of Rubicón . Since the bishopric had to be in a city after which the diocese was named, the Castillo de Rubicón was declared a city. The 13.5 × 7 m church of San Marcial was the cathedral. After the conquest of the island of Gran Canaria , the bishopric was moved to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in 1485 .

Reign of the Señores

After the subjugation of the population of the islands of Fuerteventura and El Hierro and unsuccessful attempts to conquer other islands, Jean de Béthencourt left the archipelago in December 1405 and commissioned his nephew Maciot de Béthencourt to rule over the islands. On November 15, 1419, he irrevocably transferred the lordship rights to the Canary Islands in the name of Jean de Béthencourt to the Count of Niebla, Enrique de Guzmán. Maciot de Béthencourt was confirmed by the Count in his position as captain and governor of the islands. After disputes between Maciot de Béthencourt and the new masters of the island of Lanzarote, Portuguese troops occupied the island in 1448 . After revolts by all parts of the population, the Portuguese Prince Henry the Navigator withdrew his troops from the island in 1450.

In 1452 Inés Peraza de las Casas inherited the rulership rights on the island, which she, according to the tradition of the time, exercised together with her husband Diego García de Herrera y Ayala until his death. These rights of ownership and rule were expressly confirmed in 1477 by Queen Isabella I and King Ferdinand V of Castile . After Inés Peraza's death in 1503, her son Sancho de Herrera practically took over the rule of the island. His descendants remained lords of Lanzarote until the abolition of feudal rule in the 19th century.

Natural disasters in the 18th and 19th centuries

At the beginning of the second part of the fourth main phase of volcanic activity on Lanzarote , severe volcanic eruptions occurred from September 1, 1730 . A total of 32 new volcanoes eventually formed over a distance of 18 kilometers. The eruptions were documented by Andrés Lorenzo Curbelo, pastor of Yaiza, who stayed on the island with the exception of three months, in a report that was finally completed in 1744, but only received in the form of extracts from the geologist from Buch. According to Curbelos, they lasted until April 1736, according to the files of the island administration maybe only until May 1735. In the end, lava and solid ejections had buried around a quarter of the island, including the most fertile soils on the island. More than 200 of the 1,077 households were also directly affected, several farms and villages such as Santa Catalina, Tingafa, Mancha Blanca and Chimanfaya (today Timanfaya) were completely destroyed, many others were damaged by the ejections of the volcanoes, such as San Bartolomé, Conil, Masdache and Montaña Blanca. The area with the most contiguous volcanoes was named Montañas del Fuego (Fire Mountains).

Before 1730, Lanzarote had produced excess wheat, barley and other grains, stored it for years and thus supplied other Canary Islands as the “ granary ” of the archipelago . Since the island's leadership feared that there would be no more workers available, the islanders were initially forbidden to leave the island under penalty of punishment. Soon, however, the production itself was no longer sufficient for its own supply, and at the end of 1731 severe volcanic eruptions occurred again. Half of the population were therefore allowed to emigrate to the neighboring islands of Gran Canaria , Fuerteventura and Tenerife .

In 1768 there was a catastrophic drought after there was no winter precipitation for several years. The drought claimed numerous deaths, and many residents emigrated to the neighboring islands or to Cuba and America .

In 1824, at the end of the fourth main volcanic phase, there was another volcanic eruption in the area of Tiagua , but this was nowhere near as serious as the eruptions in the years 1730 to 1736. In 1974 the Timanfaya National Park was founded.

nature

flora

Lanzarote has a barren flora due to the low rainfall . Therefore, water-storing ( succulents ), drought-resistant ( xerophytes ) and salt-tolerant plants ( salt plants ) predominate here. A total of around 570 species can be found on the island, including native and introduced species , but also 13 endemic species that are only found on Lanzarote and a further 55 species that are only found on the Canary Islands. As lower plants, lichens begin to colonize the young lava rock . So far 180 different lichens have been counted. They initiate succession , which means that they prepare the colonization with higher plant species. Grow on these advanced positions euphorbia ( spurge family , on the islands tabaiba called) and the shrub-Dornlattich , a Aulaga called frugal bramble. These plants have adapted to the water and nutrient starvation in an amazing way. The biodiversity is greater in the more humid north. Here you can find the Canary Island date palm ( Phoenix canariensis ), various fern species , Canary Island pines ( Pinus canariensis ) and occasionally the wild olive tree ( Olea europaea ). After the winter rains in February and March, the vegetation in the north awakens and turns the barren landscape into a blooming one. In the past, laurel forests are said to have covered the plateaus of the Risco de Famara . A small remnant of this forest is still today at the highest point on the Famara cliff.

fauna

Most of the mammals (except bats ) probably came to the island through humans. Including dromedaries , which were in demand as work animals and pack animals, as they were perfectly adapted to the environmental conditions. Today these animals are mainly used in tourism. In 1985 the Canary Shrew ( Crocidura canariensis ) was discovered on Fuerteventura and described as a separate species in 1987 . This shrew species was subsequently also detected on Lanzarote and two uninhabited islets off the main island .

The bird world includes around 35 species, including the rare Eleanor's falcon , but also peregrine falcon and osprey.

Among the reptiles there is the Eastern Canary Lizard ( Gallotia atlantica ), which occurs primarily in the north of the island.

The small albino crab ( Munidopsis polymorpha , order Remipedia ), which occurs in the subterranean lagoon of Jameos del Agua, is an extraordinary peculiarity . This cancer usually lives in water several thousand meters deep. It remains unclear how he got there.

Agriculture

Wine is grown on around 2300 hectares in Lanzarote (see also the article Lanzarote (wine-growing region) ). The most important grape varieties are the red Listán Negro and Negramoll . White wines are made from Listán Blanco , Malvasia , Moscatel and Diego . The La Geria wine-growing region is a nature reserve and is known for its traditional lapilli cultivation method ( Spanish enarenado natural ). The sometimes meter-thick dark lapillic layer (volcanic ash, also called picón) can be used because it heats up during the day and absorbs moisture from the air at night. Because it rarely rains here, the water is stored in this way. The roots of the cultivated plants and the grapevines can penetrate into the ground below, which is also protected from erosion. In La Geria there is the Bodega El Grifo with its own wine museum in Masdache .

This type of dry farming has spread to around 8,000 hectares in the central and northern parts of the island. The oldest example is the Opuntienfelder to Guatiza on which scale insects to produce the Karminfarbstoffs are bred. One has mostly artificially applied about 15 cm thick layers of lapilli on fertile soil ( Spanish enarenado artificial ). Today, potatoes, onions, corn, garlic, tomatoes and alfalfa are mainly grown. Another type of dry field cultivation are the sand cultures in and on the edge of the El Jable plain , which extends inland below the Famara massif. Essentially, sweet potatoes, melons, pumpkins, tomatoes and cucumbers are grown on an area of around 1000 hectares on an area of sand thinly covered with lapilli. However, the yields are somewhat lower here. As farm animals, goats are kept in several areas, from whose milk goat cheese is traditionally made in various variations. In general, the arable land is slowly declining as its use is less and less worthwhile.

Personalities

The artist César Manrique (1919–1992) made a decisive contribution to the design of the island. In 1968, Manrique reached out to Pepin Ramírez, the president of the island's administration, that no building on the island could be built higher than three stories - the height of a fully grown palm tree. This prevented the excesses of unchecked mass tourism on Lanzarote with large urban castles. For a long time there was only a single high-rise building in the capital Arrecife, which was already in place before the relevant laws took effect. This development has changed increasingly in the last few years, so that in the tourist strongholds of Costa Teguise , Puerto del Carmen and Playa Blanca higher buildings have been approved in the direction of the Papagayo beaches . The design of the houses also provided for them to be painted generally white and their shutters, doors and garden fences to be set off blue in fishing villages and green in agricultural areas. In the meantime, green and blue, but also brown and natural wood colors are mixed across the island.

art

In the Fundación César Manrique , in addition to the permanently exhibited works from the estate of the artist César Manrique , international artists who focus on the subject of “art and nature” can also be seen in temporary exhibitions. The Fundación César Manrique is located north of Arrecife on the LZ 34 road, near Tahiche.

Another exhibition building for the Fundación's temporary exhibitions, the Sala Saramaro, is located in the Plaza de la Constitución in Arrecife. Also in Arrecife is the Museo Insular de Arte Contemporáno ( MIAC ) in the Castillo San José, near the port in the Avenida de Naos.

Attractions

- El Golfo , a crater half submerged in the sea with a lagoon

- Montañas del Fuego , Fire Mountains in Timanfaya National Park

- Papagayo beaches

- Salinas de Janubio , salt pans

- Jameos del Agua , a work of art by César Manrique in lava caves

- Los Hervideros, so-called "cooking holes" on the southern lava coast, created by erosion

- Mirador del Río , a lookout point in the north of the island, designed by César Manrique

- Cueva de los Verdes , one of the longest lava tunnels in the world, partially developed for tourism

- La Geria , the island's wine-growing region

- Jardín de Cactus , a cactus garden created by César Manrique in Guatiza

- Fundación César Manrique , a foundation and museum in Tahiche

- Castillo de Santa Barbara in Teguise

- Castillo de San Gabriel and the Castillo de San José in Arrecife

- Farm museum in Tiagua

- Monumento al Campesino, peasant monument of San Bartolomé

- "Tropical Park", bird park near Guinate

- "Valley of a Thousand Palms" near Haría

- Quesera de Zonsamas and Quesera de Bravo, artifacts of the pre-Hispanic population

- Choice of sights

Jardín de Cactus with windmill by César Manrique

Jameos del Agua , work of art by César Manriques

Wall painting by the Fundación César Manrique

El Golfo crater and lagoon

Mirador del Río with La Graciosa in the background

Infrastructure

Lanzarote Airport is located near the island's capital, Arrecife . The charter planes land here mainly from England, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Switzerland. Furthermore, regional air traffic, mainly with Binter Canarias , is operated to the other islands of the archipelago.

The seaport of Puerto de Arrecife , known as Los Mármoles , is the most important transfer point for supplies for the island. From here there is also ferry service to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria , Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Cádiz on the Spanish mainland. Two other ferry lines operated by Naviera Armas and Fred. Olsen operate several times a day from Playa Blanca in the south of the island to the neighboring island of Fuerteventura . Since 2004 Fuerteventura has also been served five times a week by passenger ferry from Puerto del Carmen .

All places on the island can be reached by roads. The LZ-2 road is laid out like a motorway between the airport and Arrecife and between Yaiza and Playa Blanca. From 1988 to 1996, the number of cars in Lanzarote increased by 65 percent. This means that there are around 800 vehicles per 1000 inhabitants (as of 2006), well above the EU average. In 2016, the extension of the LZ-3 bypass around the capital Arrecife was completed, resulting in a better connection between the airport and the north of the island.

literature

- Klaus G. Förg, Eberhard Fohrer: Lanzarote. The idiosyncratic volcanic beauty. (Photo book) Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, Rosenheim 2005, ISBN 3-475-53599-8 .

- Eberhard Fohrer: Lanzarote . Michael Müller Verlag, Erlangen 2011, ISBN 978-3-89953-617-1 .

- María Antónia Perera Betancort et al .: Lanzarote Naturaleza entre volcanes / Actas X Semana Científica Telesforo Bravo . Ed .: Julio Afonso-Carrillo. Instituto de Estudios Hispánicos de Canarias, Puerto de la Cruz 2015, ISBN 978-84-608-1557-0 (Spanish, iehcan.com [PDF; 6.4 MB ; accessed on September 4, 2018]).

- Alejandro Scarpa. César Manrique, acupuntura territorial en Lanzarote . Arrecife: Centros de Arte, Cultura y Turismo del Cabildo de Lanzarote. 2019, ISBN 978-84-12-00223-2 ( Spanish version with summaries in German ).

Web links

- Lanzarote in the Global Volcanism Program of the Smithsonian Institution (English)

- Memoria digital de Lanzarote . Historical documents on the history of the island (Spanish)

- Map of Lanzarote with all architectural works by César Manrique

Individual evidence

- ↑ El censo alcanza nuevo máximo al sumar casi 162,500 residents. July 17, 2020, accessed July 19, 2020 (European Spanish).

- ↑ Superficie por islas de Canarias. In: gobiernodecanarias.org. Retrieved September 11, 2017 (Spanish).

- ↑ In Canarian Spanish , as in all of Hispanic America , the "z" is pronounced as [s]. The Real Academia Española therefore says: “[S] e indica siempre, y en primer lugar, la pronunciación seseante, por ser la mayoritaria en el conjunto de los países hispanohablantes.” (Translation: The pronunciation with “s” ( Seseo ) becomes always stated first as it is used by the majority of Spanish speakers .) Real Academia Española: Diccionario panhispánico de dudas . First edition. Santillana: Madrid, 2005, ISBN 84-294-0623-9 .

- ^ Elecciones Locales. Resultados electorales al Cabildo de Lanzarote (26 de mayo de 2019). In: datosdelanzarote.com. Cabildo de Lanzarote, accessed November 29, 2019 (Spanish).

- ↑ Desaladora Lanzarote V. Arrecife, Lanzarote / V Lanzarote Desalination Plant - Arrecife, Lanzarote . In: Futurenviro . Special edition June 2015. Saguenay SLU, June 2015, ISSN 2340-2628 (Spanish / English, futurenviro.com [PDF; 2.6 MB; accessed February 25, 2018]).

- ↑ Lanzarote: Montaña del Fuego in the Timanfaya National Park. In: vulkane.net . 2011, accessed March 26, 2020 (updated 2019).

- ↑ Geothermal energy for Tenerife. In: wochenblatt.es . August 10, 2013, accessed May 30, 2020.

- ↑ La presa de Mala. In: rubicon.lanzarote3.com. July 14, 2015, Retrieved September 28, 2017 (Spanish).

- ↑ Mala Reservoir will never have water. In: radio-europa.fm. December 17, 2014, accessed October 1, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Juan Carlos Carracedo, Eduardo Rodríguez Badiola, Vicente Soler: Aspectos volcanológicos y estructurales, evolución petrológica e implicaciones en riesgo volcánico de la erupción de 1730 en Lanzarote, Islas Canarias. In: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (España) (ed.): Estudios geológicos. Vol. 46, 1990, pp. 25-55 (PDF, 1.7 MB)

- ↑ Leopold von Buch: About a volcanic eruption on the island of Lanzerote. Treatise read aloud in the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences on February 4, 1819. Freely accessible digitized material that can be downloaded as an eBook

- ^ Leopold von Buch: "Physical description of the Canary Islands." Berlin 1825.

- ↑ a b c d Andrés Lorenzo Curbelo, Wolfgang Borsich: "When the volcanoes spat fire. Lanzarote diary. Notes on the events in the years 1730 to 1736." Translation of the excerpts from the diary Curbelos, concept & layout by Wolfgang Borsich. Editorial Yaiza SL, Lanzarote 2011. ISBN 978-84-89023-31-4

- ↑ Pablo Peña Atoche: Excavaciones Arqueológicas en el sitio de Buenavista (Lanzarote) - Nuevos datos para el estudio de la Colonización protohistórica del archipiélago . In: Gerión . tape 29 , no. 1 , 2011, ISSN 0213-0181 , p. 59-82 (Spanish, dialnet.unirioja.es [accessed May 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Pablo Atoche Peña, María Ángeles Ramírez Rodriguez: C14 references and cultural sequence in the proto-history of Lanzarote (Canary Islands) . In: Juan A. Barceló, Igor Bogdanovic, Berta Morell (eds.): Cronometrías para la Historia de la Península Ibérica. Actas del Congreso de Cronometrías para la Historia de la Península Ibérica . 2017, ISSN 1613-0073 , p. 278 (English, [1] [accessed on January 16, 2019]).

- ↑ Pablo Peña Atoche: Las Culturas Protohistóricas Canarias en el contexto del desarrollo cultural mediterráneo: propuesta de fasificación . In: Rafael González Antón, Fernando López Pardo, Victoria Peña (eds.): Los fenicios y el Atlántico IV Coloquio del CEFYP . Universidad Complutense, Centro de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos, 2008, ISBN 978-84-612-8878-6 , pp. 329 (Spanish, [2] [accessed May 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Eduardo Aznar: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape XLII . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 11 (Spanish).

- ↑ Pierre Bontier, Jean Le Verrier: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape XLII . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 99 (Spanish).

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Ulbrich: The discovery of the Canaries from the 9th to the 14th century: Arabs, Genoese, Portuguese, Spaniards . In: Almogaren . No. 20 , 2006, ISSN 1695-2669 , pp. 129 ( [3] [accessed February 25, 2017]).

- ↑ José Carlos Cabrera Pérez, María Antonia Perera Betancort, Antonio Tejera Gaspar: Majos, la primitiva población de Lanzarote - Islas Canarias . Fundación César Manrique, Teguise (Lanzarote) 1999, ISBN 84-88550-30-8 , p. 104 (Spanish, [4] [accessed May 22, 2017]).

- ↑ Alejandro Cioranescu: Juan de Bethencourt . Aula de Cultura de Tenerife, Santa Cruz de Tenerife 1982, ISBN 84-500-5034-0 , p. 158 (Spanish).

- ↑ Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape XLII . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 46 (Spanish).

- ↑ Eduardo Aznar: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 49 (Spanish).

- ↑ Eduardo Aznar: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 15 (Spanish).

- ^ Antonio Tejera Gaspar, Eduardo Aznar Vallejo: San Marcial de Rubicón: la primera ciudad europea de Canarias . Artemisa, La Laguna 2004, ISBN 84-96374-02-5 , pp. 73 ff . (Spanish).

- ↑ Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada: Jean de Béthencourt, Sevilla y Henrique III . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos II. (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape XLIII . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-59-0 , p. 30 (Spanish).

- ↑ Alejandro Cioranescu: Juan de Bethencourt . Aula de Cultura de Tenerife, Santa Cruz de Tenerife 1982, ISBN 84-500-5034-0 , p. 232 (Spanish).

- ↑ Manuel Lobo Cabrera: La conquista de Gran Canaria (1478-1483) . Ediciones del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-8103-653-4 , p. 55 ff . (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: El señorío de Fuerteventura en el siglo XVI . In: Anuario de estudios atlánticos . No. 32 , 1986, pp. 30 (Spanish, dialnet.unirioja.es [accessed February 16, 2020]).

- ↑ Cazorla León Santiago, Sánchez Rodríguez: Los Volcanes de Chimanfaya . Ed .: Ayuntamiento de Yaiza, Lanzarote, Departamento de Educación y Cultura, 2003

- ^ Rainer Hutterer , Luis Felipe López Jurado, Peter Vogel : The shrews of the eastern Canary Islands: a new species (Mammalia: Soricidae) . In: Journal of Natural History . tape 21 , no. 6 . Taylor & Francis, 1987, ISSN 0022-2933 , pp. 1347-1357 , doi : 10.1080 / 00222938700770851 (English).