Tenerife

| Tenerife | |

|---|---|

| Satellite image | |

| Waters | Atlantic |

| Archipelago | Canary Islands |

| Geographical location | 28 ° 19 ′ N , 16 ° 34 ′ W |

| area | 2,034.38 |

| Residents | 917.841 (2019) |

| main place | Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

| Aerial view from west northwest with the Teno Mountains and the rocks of Los Gigantes in the foreground | |

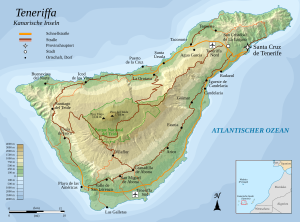

Tenerife ( Spanish Tenerife ) is the largest of the Canary Islands and belongs to Spain . The island is 83.3 kilometers long, up to 53.9 kilometers (east-west extension) wide and has an area of 2,034.38 square kilometers. With 917,841 inhabitants, it is the most populous island in Spain. The capital is Santa Cruz de Tenerife . The locals are called Tinerfeños .

geography

Tenerife is a volcanic island. Like all the Canary Islands, it belongs topographically to Africa , is 288 kilometers off the coast of Morocco and the Western Sahara and is 1,274 kilometers from the south coast of mainland Spain.

geology

The island of Tenerife was formed about twelve million years ago through volcanic activity. This is due to a hotspot in the Earth's mantle , which, through its activity, creates a chain of islands , while the African Plate drifts to the northeast via this point in the Earth's interior . The geologically oldest parts of the island are the Anaga Mountains in the extreme northeast, the Teno Mountains in the northwest and small areas (Bandas del Sur) in the extreme south.

Younger is the volcanic massif in the center of the island, which is occupied in the middle by a 12 by 17 kilometer caldera called Las Cañadas . From it rises the highest mountain in Spain, the 3715 meter high Pico del Teide .

Viewed from above, these mountain areas together have the shape of the letter "Y".

The proven volcanic eruptions between the Teide massif and the Teno mountains in 1706, 1798 and 1909 show that the island is still very volcanically active.

climate

Like all the other islands of the Canary Islands, Tenerife has mild temperatures all year round due to the northeast trade winds that develop south of the Rossbreiten . These tropical downwinds are also responsible for the so-called Azores high , which is located over Madeira in winter , but migrates further north to the Azores in summer . Especially during the day, the air, saturated with water vapor from the sea, rises up the Teidemassiv. It formed in about 1000 to 1500 meters altitude clouds that emit a fine drizzle in contact with the local laurel and pine forests (see fog condensation ). This fact brings decisive advantages for agriculture on the north side of the island in the otherwise extremely dry summer months. There are also high temperature phases with more than 35 degrees.

|

Average monthly temperatures for Santa Cruz (Tenerife)

Source: missing

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

nature

Flora and fauna

The island has a diverse vegetation - numerous plant species are only native ( endemic ) to the Canary Islands or even only to Tenerife . The Canary Pine ( Pinus canariensis ) forms large forests. Succulent milkweed plants ( Euphorbia canariensis ) are found in the dry south of the island . Other characteristic plant species are z. B. the magnificent Tenerife - adder head (called 'Orgullo de Tenerife - pride of Tenerife' or Taginaste, wild prets adder head ) and the Canarian dragon tree ( Dracaena draco ) - an old and impressive specimen can be found at Icod de los Vinos . In addition to the native plants, many plants from all over the world also shape the island. Feral cacti and the huge bushes of the poinsettia , a plant that is sold in pots in Central Europe for Advent, come from America . The distinctive inflorescences of the South African Strelitzia are a popular souvenir for tourists. Almost all plant species are now subject to strict species protection , the export of plants, parts of plants or seeds is therefore prohibited.

Apart from feral domestic cats and introduced wild rabbits, the animal world hardly contains any mammals. There have never been larger predators or poisonous snakes. On the other hand, the bird world is rich - there are also some species typical of Tenerife and the Canaries, such as the Tey finch or the wild form of the canary , the Canary Girlitz . Also to be mentioned are the western Canary Islands lizards , which are found in large numbers on Tenerife.

The butterfly species endemic to the Canary Islands include the Canary Whites ( Pieris cheiranthi ), the Canary Admiral ( Vanessa vulcania ) and the Canary forest board game ( Pararge xiphioides ).

A special feature are the pilot whales , which can be found in large numbers in the up to 2000 meters deep strait between Tenerife and La Gomera . There is hardly any other coastal location in the world that has so many whales.

natural reserve

There are several protected areas on the island.

The whole island has also been a light protection area since 1988 ( Ley del Cielo 31/1988), especially for the Observatorio del Teide (European Northern Observatory ).

Natural symbols of the island

Natural symbols of the island of Tenerife are:

Teydefink ( Fringilla teydea )

story

First settlers

The oldest traces of human presence on the island of Tenerife date from the 10th century BC. The permanent settlement of the island probably happened continuously or in several waves between the 5th century BC. BC and the 1st century AD The settlers most likely came from the area north and south of the Strait of Gibraltar . Between the 1st century BC BC and the 1st century AD there were close economic ties between the Mediterranean and the Canary Islands. Relations between the islands and Europe ended with the imperial crisis of the 3rd century at the latest .

Since the Guanches , the indigenous inhabitants of the island of Tenerife, had no nautical knowledge whatsoever, the connections between the individual islands also broke off. Contacts between Tenerife and La Gomera only seem to have occurred occasionally through individuals. During the next thousand years or so, the Guanches on the island of Tenerife developed a culture that was clearly different from the old Canaries on the other islands.

Rediscovery in the 14th / 15th centuries

In the 14th century, technical advances made it possible for Mediterranean seafarers not only to reach the Canary Islands, but also to return to Europe. The interest of the Europeans focused on the eastern islands, which were closer to the African mainland and where it was easier to get into the interior of the islands because the coasts were not so steep.

An expedition equipped by the Portuguese King Alfonso IV visited the Canary Islands in 1341. A report about it, which was probably written by Niccoloso da Recco, one of the leaders of this trip, is available today in the editing of Giovanni Boccaccio . It is considered to be the first credible piece of information about the islands since their rediscovery in the late Middle Ages. Precise information is given about the peculiarities of some islands. Tenerife was not entered by the expedition because they were afraid of wondrous natural phenomena on the high mountain. After this trip at the latest, the location of all islands in Europe was known. The oldest map in which Tenerife was represented almost correctly in its position and form is part of the Portolano Laurenziano Gaddiano in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana from the year 1351. There it is, as in many other maps and reports of the following period, as " Insula de Infierno “(Island of Hell).

- Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de la Salle

Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de la Salle , who came from France, brought the inhabitants of the islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and El Hierro under the suzerainty of the Crown of Castile from 1402. From the reports of the Chronicle Le Canarien , in which the activities of the French are described, one can conclude that, however, they never set foot on Tenerife. Jean de Béthencourt was in 1403 by King Henry III. of Castile granted the right to conquer and subsequent possession of the Canary Islands.

1405 put Jean de Béthencourt his relative Maciot de Béthencourt as a deputy. He gave the rights in 1418 to Enrique de Guzmán, Count of Niebla. After a few more transfers, Inés Peraza de las Casas and her husband Diego García de Herrera received the rulership of the entire archipelago from 1452. After the rights accidentally granted by Henry IV were withdrawn, the members of the Peraza – Garcia de Herrera family were theoretically masters of the Canary Islands from 1468 without restrictions or reservations, even if some of them had not yet been conquered.

- Diego García de Herrera y Ayala

After Diego García de Herrera took possession of the island of Gran Canaria in a symbolic ceremony on August 16, 1461 in the presence of the Guanartemes of Telde and Gáldar in the name of the King of Castile, he repeated this type of occupation on June 21, 1464 for the Tenerife island. In the solemn act, documented in the documents as “Acta de Bufadero”, the Menceyes, referred to as “kings”, of the nine territories of the islands took part. The documents state that these nine kings paid their respects to their lord "Diego de Perrera", kissed his hands and promised to obey him as their lord. Not only the interpreter and people from the environment of Diego García de Herreras, but also citizens of the island of Lanzarote, citizens of Seville and many others "who speak the language of the island of Tenerife" were listed as witnesses. To give the document more meaning, it was certified by the Bishop of Rubicón , Diego López de Illescas, and sent to the court of Castile. This act of taking power was purely symbolic. There was nothing that later turned out to be an acknowledgment of sovereignty.

After taking possession of Tenerife, Diego García de Herrera signed a contract with the Mencey of Anaga to build a fortification near Añazo (now in the area of downtown Santa Cruz de Tenerife). The purpose of the facility, occupied by a few soldiers, was to enable trade between the island of Tenerife and the islands under Castilian sovereignty. The friendly relations between the Castilians and the Guanches lasted from around 1465 to 1471. The behavior of the soldiers of the garrison and the reactions to it by Diego García de Herrera led to the Guanches attacking and destroying the facility.

Proselytizing

- Virgin of Candelaria

The center of the Christian mission in Tenerife was on the south side of the island in the Menceyato Güímar . According to legend, two guanches who were herding goats in the area found a wooden sculpture of a woman with a child on the beach in Chimisay. They informed their ruler, the Mencey of Güímar, who had the figure brought to his residence, the Chinguaro cave.

The time when the statue of the saint, now venerated as the Virgin of Candelaria , was found is as unknown as its origin. There are different guesses:

- Mallorcan-Catalan missionaries put them on the beach in the last decades of the 14th century.

- The Friars Minor of the San Buenaventura monastery on the island of Fuerteventura brought them to Tenerife between 1425 and 1450.

- The Franciscan brother Alfonso de Bolaños wanted to astonish the Guanches with the appearance of the sculpture in the middle to the end of the 15th century.

- Alfonso de Bolaños

In 1462 the Franciscan brother Alfonso de Bolaños and some of his companions established a mission base in Güímar. The project was not to be limited to the island, but aimed at the entire African coast. Thirty years before the conquest, the missionaries lived with the Guanches and preached to them in their language. After the election of the Franciscan Sixtus IV as Pope, Bolaños had the opportunity in 1472 to present his program and his missionary successes to him personally. In his report, Alfonso de Bolaños claimed that he and his confreres had converted several thousand pagans in Tenerife. An affirmation that was certainly exaggerated. The Franciscan missionary project was very much based on the personality of Bolaño. After his death in 1480, this type of mission, which was independent of political and military efforts, was discontinued on the island.

conquest

Diego García de Herrera failed to subdue the islands of Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife with negotiations and without fighting. His means were insufficient for a military conquest. Therefore, the Crown of Castile agreed with Diego García de Herrera and Inés Peraza in 1477 the return of the rights to the conquest and political rule over the islands. Gran Canaria was conquered by Castilian troops by 1483. In 1492 the Castilians under the leadership of Alonso Fernández de Lugo encountered little resistance when conquering the island of La Palma.

In May 1493, right after the conquest of La Palma, Alonso Fernández de Lugo traveled to Gran Canaria to organize the conquest of the island of Tenerife. In the autumn of 1493 he negotiated at the court of the Queen and King of Castile, who was staying in Saragossa at the time, about the conditions for the conquest of the last Canary Island, which was not under Castilian rule. By the "Capitulaciones de Zaragoza" he was obliged to conquer the island of Tenerife with the means he had raised.

- First landing (1494)

In May 1494, 1,500 infantrymen and 150 horsemen landed under the command of Alonso Fernández de Lugos on the beach of Añazo, just south of what is now downtown Santa Cruz de Tenerife . Peace treaties were signed with the Menceyes of Anaga, Güímar , Abona and Adeje . A conversation between the Mencey of Taoro Bencomo and Alonso Fernández de Lugo did not lead to an agreement. The Menceyes of Tegueste , Tacoronte , Taoro, Icod and Daute were not ready to submit to the Castilian kings. The Castilian troops then marched towards the area of Taoro ( Orotava Valley ).

- First Battle of Acentejo

In the Barranco de Acentejo, a narrow gorge, the Castilian troops were attacked by the Guanches. The Castilians were not able to adopt a battle order and thus use their superior weapon technology. The First Battle of Acentejo ended in a "slaughter" ( Spanish matanza ). Of the attackers, only 300 foot soldiers and 60 horsemen survived.

- Second landing (1495)

Alonso Fernández de Lugo found new donors who provided the funds for equipping a new army of conquest. At the beginning of November 1495, 1,500 men and 100 horses landed again on Añazo beach. The troops consisted almost entirely of experienced soldiers. A large number of them had fought in the conquest of the kingdom of Granada . The Duke of Medina Sidonia sent a contingent of 38 horsemen and 722 foot soldiers .

- Battle of Aguere

On November 14th, the Castilian troops faced the Guanche forces of the Menceyatos on the north side of the island. The battle took place in an open area just below what is now downtown La Laguna. The Guanches were mainly armed with a fire-hardened wooden lance (banote). The Guanches' most dangerous weapon for the Castilians were thrown stones with sharp edges which had already led to many wounded and dead on the side of the attackers in the first battle of Acentejo. When the troops were clearly juxtaposed, the Castilians were able to use firearms and crossbows. The grasslands of La Laguna allowed the Castilian cavalry to flourish. That made the Guanches' defeat inevitable. 45 attackers and 1,700 guanches were killed in the battle. After the Battle of Aguere, the Castilians built an army camp on the western edge of the Orotava Valley, from which today's city of Los Realejos developed.

- Second Battle of Acentejo

During December 24th, 1495, the leadership of the Castilian troops was informed by scouts that the Menceyes of Taoro, Tacoronte, Tegueste, Icod and Daute were preparing for an attack. On Christmas Day 1495, the Castilian troops marched north from their camp. Near the site of the first battle of Acentejo, another battle, known as the "Second Battle of Acentejo", broke out in which the Guanches were defeated. A large part of the Guanches fled to the inaccessible mountain regions. On February 15, 1496, most of the Castilian troops were demobilized on the island. In May 1496, the Menceyes surrendered to the territories of the north side of the island in the army camp of Los Realejos. (The official date is July 25th, the holiday of the Spanish national saint Santiago .)

A new society emerges

- Distribution of land and water rights

Participants and donors of the conquest of Tenerife were z. T. shares in the island's land and water rights have been promised as compensation for their services. About half of the soldiers who participated in the conquest of the island were troops of the Duke of Medina Sidonia who returned to Andalusia at the end of February. Some of the other soldiers only took part in the conquest to avoid a judicial conviction in Castile. They could now return to their homeland without having to expect further persecution. Many of the soldiers did not aspire to live as landowners, but moved on to America. Only 126 of the 1,016 people included in the land grants in Tenerife were soldiers from the Spanish peninsula. Thirty other conquerors who were given land came from Gran Canaria and three from La Gomera. Therefore, in the lands of the Crown of Castile, settlers were recruited, sometimes with the promise of land allotments. The settlement efforts on the island of Tenerife competed with the new settlements in the Kingdom of Granada and in America.

The colonizers had to settle on the island for at least five years, clear the parcels in the prescribed time and devote themselves mainly to the cultivation of the plantations indicated in their allocation deed. In order to promote the island's economy, some properties that were also equipped with appropriate water rights required the cultivation of sugar cane and the necessary processing facilities to be built. That was only possible for the conquerors and settlers who had the necessary funds or who had been given them from other sources. This led to the establishment of large farms, in the areas particularly in the north of the island that were most closely linked to the export market. The lands of the indigenous people who did not have the necessary funds were in the not so fertile south of the island.

- Composition of the new society of Tenerife

Since the first contact of the Canary Islands with Europe in the 14th century, the population has been reduced to around 5% of the initial population through abduction as slaves, killings in the course of military attacks, disease and the deterioration in general living conditions. The Guanches were nevertheless the largest group of the newly emerging society after the conquest, with around 40%, which consisted of natives, conquerors and settlers from Galicia , Asturias , the Basque Country , Estremadura , Castile and Andalusia. Many craftsmen came from Portugal . In addition, large numbers of Africans from north and south of the Sahara were brought to the islands as slaves. A numerically small but economically significant group were Italians and Flemings who mostly settled as traders and investors. In this newly emerging society, it was not the local but the social origin of a person that was decisive. Old Canarians who were taken into account in the land distribution and their descendants belonged to the group of landowners. Some were given the title “Don”, which in Castile only belonged to the aristocracy. Others became clergy with appropriate dispensation because their parents were not Christian. The common basis of society was the Christian faith and ethics as well as the Castilian language. In the following period, the official documents only differentiated between people who were born on the island or who came from outside the island.

Tenerife under the rule of the Crown of Castile

In 1657 the English admiral Robert Blake tried unsuccessfully to conquer Santa Cruz de Tenerife with a fleet of 36 warships . Under Admiral John Jennings , the English tried again in 1706 to take the port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. However, the attack failed and with it the plan to conquer the fertile and conveniently located Tenerife for Great Britain on the Atlantic route. In 1778 Santa Cruz de Tenerife received from the Spanish King Carlos III. the privilege to trade with America.

In 1792 the first and until 1989 only university in the Canary Islands was founded in La Laguna. In the 2011/2012 academic year, the Universidad de La Laguna (ULL) had 22,491 students.

The English admiral Horatio Nelson lost his right arm in a new attack on Santa Cruz de Tenerife on July 25, 1797 and also suffered the only defeat in his military career.

Santa Cruz de Tenerife became the capital of the entire Canary Islands archipelago in 1822 and held this status until 1927.

Tenerife experienced a heyday during the Enlightenment . Important personalities such as Alexander von Humboldt (1799) visited the island. Nevertheless, Tenerife could not break away from the prevailing feudal social order, so that political reforms only came about in the 19th century .

The first years of the 20th century were marked by progressive political radicalization. In 1936, General Franco from Tenerife launched his coup against the republic. The Spanish Civil War did not reach Tenerife; the economic isolation under the dictatorship had a very negative effect. The only export goods at the time were bananas for the mainland.

Tenerife North Airport was opened in 1946, and Tenerife South Airport in 1978 .

In the course of democratization (" Transición ") after the end of the Franco dictatorship in Spain, Tenerife and all the other islands of the archipelago were given more autonomy; the tourism became more and more important. Within Spain, the Canary Islands received pre-autonomy in 1978 and in 1982 the status of an autonomous region with extensive self-government. The capitals Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria alternate as the seat of government every four years.

On March 27, 1977 two jumbo jets of the airlines KLM and PanAm collided at the airport "Los Rodeos" (Tenerife North) near La Laguna . The plane disaster in Tenerife is the most serious accident in aviation history with 583 deaths .

Sights (selection)

- Old town of La Laguna , ( World Heritage Site by UNESCO )

- Old town of La Orotava

- Orotava valley

- Jardín de Aclimatación de la Orotava (Botánico) , the botanical garden in Puerto de la Cruz

- The crater landscape of the Teide National Park , a UNESCO World Heritage Site, ascent to the Teide with the Teleférico del Teide is possible

- Los Roques de García in the Parque Nacional de las Cañadas del Teide

- Mercedeswald and Parque Rural de Anaga in the Anaga Mountains , biosphere reserve

- Masca canyon

- Los Gigantes rocks

- Barranco del Infierno (Hell Gorge) near Adeje

- Drago Milenario in Icod de los Vinos

- Güímar pyramids

- The port and old town of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, with a variety of historical buildings, shopping areas and the architecturally interesting Canarian Parliament

- Auditorio in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, futuristic concert hall designed by the architect Santiago Calatrava

- Whale or dolphin watching and diving off the southern tip of Tenerife, starting from Playa Paraíso

- Loro Parque with, among other things, the largest collection of parrots in the world

- Museo de la Naturaleza y el Hombre , natural history museum in Santa Cruz de Tenerife with the history of the guanches and mummies.

- Candelaria Basilica : the largest church in the Canary Islands dedicated to the Virgin Mary

- La Laguna Cathedral : Seat of the Bishop of San Cristóbal de La Laguna .

- Siam Park : Water park in Costa Adeje

- Anaga Mountains : The area has also been a biosphere reserve since 2015 .

- Casa Hamilton : hydraulic structure

Economy and Infrastructure

economy

Tenerife has been a typical holiday island for decades; The economy and infrastructure are shaped by it. The tourism focuses mainly on the north coast of Puerto de la Cruz and the south at Los Cristianos and Playa de las Américas . In agriculture , potatoes , bananas , tomatoes and wine are grown.

energy

Electricity is generated by oil and natural gas- fired gas turbines and steam boilers with steam turbines , wind power and photovoltaics . The systems are mainly installed in the southeast (industrial zone CTCC Granadilla).

administration

Since the Ley de Cabildos (German: Cabildo Law) came into force in 1913, the local administrative authority has been the Cabildo Insular , which performs its own tasks below the level of the provinces and above the level of the Municipios (German: city administrations). The island is divided into 31 Municipios:

traffic

Inside the island

The north motorway TF-5 leads from the capital Santa Cruz de Tenerife to the holiday center Puerto de la Cruz . It ends in Los Realejos and continues as a country road to Icod de los Vinos .

The southern motorway TF-1 leads from Santa Cruz via Los Cristianos , Costa Adeje and Playa de las Américas to Santiago del Teide . The last 18 km long section of the TF-1 from Adeje to Santiago del Teide was completed in 2015. The construction of the TF-1 and the Tenerife South Airport pushed the development in the south of Tenerife enormously and enabled the development of many places on the southeast coast (e.g. Abades ).

Special feature: A special lane for buses leads on the northern motorway between a lane divider and the central barrier towards the city through a tunnel directly to the Santa Cruz bus station (Intercambiador de Transportes), while the rest of the traffic is directed in a different direction.

The green buses of TITSA (local name: Guagua), which serve almost every town on the island, are cheap and reliable means of transport . The main routes over the southern motorway from Las Américas or Los Cristianos in the south of the island to Santa Cruz and the northern motorway to Puerto de la Cruz in the north are driven by modern air-conditioned buses with luggage compartments. Buses run at least every hour to the two airports Tenerife North (Los Rodeos) and South (Reina Sofía) .

An approximately twelve kilometer long tram line ("Tranvía") has been connecting Santa Cruz with the northern suburbs, the university and downtown La Laguna since June 2, 2007 . A second line has existed since May 30, 2009 between the districts of La Cuesta and Tincer. An extension to Tenerife North Airport is being discussed (as of 2009); also the construction of a railway line that will connect Santa Cruz with the south of the island and the Tenerife Sur Reina Sofía airport.

To neighboring islands and long-distance destinations

There are two airports - the older Tenerife North Airport (Los Rodeos) near La Laguna and Reina Sofía Airport ( Tenerife South ), which opened in 1978 .

Ferries connect Tenerife with the Canary Islands La Gomera, El Hierro, La Palma, Gran Canaria, Lanzarote and Fuerteventura. Naviera Armas operates a ferry connection from Tenerife to Huelva and Trasmediterránea from Tenerife to Cádiz .

Festivals

- Feast of the Blessed Virgin of Candelaria (February 2nd)

- Carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife (between February and March)

- Good Friday processions (Holy Week)

- Noche San Juan (June 23rd to 24th): Midsummer bonfires are lit across the island (both on the beaches and inland).

- Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (August 15)

- Fiestas del Santísimo Cristo de La Laguna (September 14th)

literature

- Curt Theodor Fischer: Fortunatae insulae. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume VII, 1, Stuttgart 1910, Col. 42 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Irene Börjes: Tenerife. Michael Müller, Erlangen 1996, ISBN 3-923278-36-5 .

- Jürgen Richter, Ralf Nestmeyer : Journey through Tenerife. Stürtz, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 3-8003-1630-7 .

- Eyke Berghahn, Petrima Thomas, Hans-R. Grundmann: Tenerife. 5th edition. Reise-Know-How-Verlag Grundmann, Westerstede 2010, ISBN 978-3-89662-257-0 .

- Hans-Ulrich Schmincke , Mari Sumita: Geological Evolution of the Canary Islands. A young volcanic Archipelago adjacent to the old African Continent . Görres, Koblenz 2010, ISBN 978-3-86972-005-0 .

Web links

- Zedler-Lexikon-Entry Tenerife , Volume 42 (1744), Col. 857-858.

- Entries in German historical encyclopedias of the full-text library on the historical names Happy Islands (lat. Fortunatae insulae) , Ningaria or Nivaria and Tenerife (1809–1911)

- Cabildo de Tenerife - Island Government of Tenerife (Spanish)

- The geology of the island (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Population statistics from January 1, 2019.

- ↑ Herwig Wakonigg: The east Atlantic volcanic islands . Azores. Madeira archipelago. Canaries. Cape Verde. Your natural, economic and cultural area. In: Austria: Research and Science, Geography . tape 2 . Lit Verlag, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-8258-1829-6 , Chapter 14.3: Natural hazards and natural disasters in the Canary Islands, p. 245 .

- ↑ Red Canaria de Espacios Naturales Protegidos - Tenerife ( Memento of the original dated February 12, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , gobiernodecanarias.org

- ↑ Ley 31/1988 de 31 de octubre, sobre Protección de la Calidad Astronómica de los Observatorios del Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias. ( Ley del Cielo ) . BOE núm. 264, 3 de noviembre de 1988 (pdf; web link ; both iac.es) - Dispociones Adicionales, Primera extends the protection for La Palma to observatories on the island of Tenerife, except for outdoor lighting

- ↑ Ley 7/1991, de 30 de April, de símbolos de la naturaleza para las Islas Canarias

- ↑ Pablo Atoche Peña, María Ángeles Ramírez Rodríguez: El archipiélago canario en el horizonte fenicio-púnico y romano del Círculo del Estrecho (approximately siglo X ane al siglo IV dne) . In: Juan Carlos Domínguez Pérez (ed.): Gadir y el Círculo del Estrecho revisados. Propuestas de la arqueología desde un enfoque social (= Monografías Historia y Arte ). Universidad de Cádiz, Cádiz 2011, ISBN 978-84-9828-344-0 , pp. 249 (Spanish, ulpgc.es [accessed May 17, 2017]).

- ↑ Pablo Atoche Peña, María Ángeles Ramírez Rodríguez: Canarias en la etapa anterior a la conquista bajomedieval (circa s. VI aC al s. XV dC): Colonización y manifestaciones culturales . Ed .: Gobierno de Canarias. Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes. Viceconsejería de Cultura y Deportes. Dirección General de Cultura. (= Arte en Canarias [siglos XV-XIX]. Volume I ). Gobierno de Canarias. Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes. Viceconsejería de Cultura y Deportes. Dirección General de Cultura., Madrid 2001, p. 45 f . (Spanish, ulpgc.es [accessed May 17, 2017]).

- ↑ Eduardo Aznar: Le Canarien: Retrato de dos mundos I. Textos . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape XLII . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-58-2 , p. 11 (Spanish).

- ^ Giovanni Boccaccio: De Canaria y de las otras islas nuevamente halladas en el océano allende España (1341) . Ed .: Manuel Hernández Gonzalez (= A través del Tiempo . Volume 12 ). JADL, La Orotava 1998, ISBN 84-87171-06-0 , pp. 31-66 (Spanish).

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Ulbrich: The discovery of the Canaries from the 9th to the 14th century: Arabs, Genoese, Portuguese, Spaniards . In: Almogaren . No. 20 , 2006, ISSN 1695-2669 , pp. 101 ( unirioja.es [accessed February 25, 2017]).

- ^ Antonio Tejera Gaspar: Los aborígenes en la chrónica Le Canarien . In: Eduardo Aznar, Dolores Corbella, Berta Pico, Antonio Tejera (eds.): Le Canarien: retrato de dos mundos (= Fontes Rerum Canarium ). tape XLIII . Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-59-0 , p. 116/153 (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 111 (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 100 ff . (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Juan Álvarez Delgado: La conquista de Tenerife - Un reajuste de datos hasta 1496 . In: Revista de Historia Canaria . No. 125 , 1959, ISSN 0213-9472 , pp. 177 ff . (Spanish, ulpgc.es [PDF; accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 64 (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Julio Sánchez Rodríguez: La iglesia de las Islas Canarias. (PDF) Secretariado de Medios de Comunicación de la Diócesis de Canarias, 2006, p. 42 , accessed on March 9, 2019 (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 39 ff . (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ^ Ana del Carmen Viña Brito: La actuación de Juan Fernández de Lugo Señorino primer teniente de gobernador de La Palma, como detonante del intervencionismo regio . In: Revista de Historia Canaria . No. 189 , 2007, ISSN 0213-9472 , p. 156 ff . (Spanish, unirioja.es [accessed January 14, 2018]).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 217 (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 238 (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 281 (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ^ Alfredo Mederos Martín: Un enfrentamiento desigual - Baja demografía y difícil resistencia en la conquista de las Islas Canarias . In: Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos . No. 65 , 2018, ISSN 0570-4065 , p. 1 (Spanish, unirioja.es [accessed February 21, 2019]).

- ^ John Mercer: The Canary Islanders - their prehistory conquest and survival . Rex Collings, London 1980, ISBN 0-86036-126-8 , pp. 205 (English).

- ↑ real. In: Diccionario de la lengua española. Real Academia Española, accessed April 15, 2018 (Spanish).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 318 f . (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Antonio Rumeu de Armas: La Conquista de Tenerife . Ed .: Instituto de Estudios Canarios. 2nd Edition. Instituto de Estudios Canarios, La Laguna 2006, ISBN 84-88366-57-4 , p. 334 (Spanish, hdiecan.org [accessed December 25, 2017]).

- ^ Eduardo Aznar Vallejo: La integración de las Islas Canarias en la Corona de Castilla (1478-1526) . Idea, Santa Cruz de Tenerife 2009, ISBN 978-84-9941-022-7 , pp. 175 f . (Spanish).

- ^ Antonio M. Macías Hernández: La economía moderna (Siglos XV-XVIII) . In: Antonio de Béthencourt Massieu (ed.): Historia de Canarias . Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 1995, ISBN 84-8103-056-2 , p. 144 (Spanish).

- ^ Antonio Manuel Macías Hernández: La construcción de las sociedades insulares: el caso de las Islas Canarias . In: Estudios Canarios: Anuario del Instituto de Estudios Canarios . No. 45 , 2000, ISSN 0423-4804 , p. 136 f . (Spanish, unirioja.es [accessed March 19, 2019]).

- ^ Antonio M. Macías Hernández: Nobles, campesinos y burgueses . In: Antonio de Béthencourt Massieu (ed.): Historia de Canarias . Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 1995, ISBN 84-8103-056-2 , p. 204 (Spanish).

- ↑ teneriffaplus.de: Tenerife - historical overview , accessed on December 11, 2017.

- ↑ August 10, 1982: Adoption of the Statute of Autonomy for Aragon, Castile-La Mancha, Canary Islands

- ↑ The attack on the World Trade Center claimed more victims, but it was not an accident.

- ↑ El macizo de Anaga alberga mayor concentración de endemismos de toda Europa

- ↑ As of January 2017.

- ↑ Noche San Juan - The Beach Highlight. Retrieved November 28, 2017 .