Tenerife air disaster

| Tenerife air disaster | |

|---|---|

|

Wreck on the slopes |

|

| Accident summary | |

| Accident type | Collision on the ground |

| place | Tenerife Airport "Los Rodeos" |

| date | March 27, 1977 |

| Fatalities | 583 |

| Injured | 61 |

| 1. Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-121 |

| operator | Pan American World Airways |

| Mark | N736PA |

| Surname | Clipper Victor |

| Departure airport |

|

| 1. Stopover |

|

| 2. Stopover |

(unplanned) |

| Destination airport |

|

| Passengers | 380 |

| crew | 16 |

| Survivors | 61 |

| 2. Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-206B |

| operator | KLM Royal Dutch Airlines |

| Mark | PH-BUF |

| Surname | Rijn |

| Departure airport |

|

| Stopover |

(unplanned) |

| Destination airport |

|

| Passengers | 234 |

| crew | 14th |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Lists of aviation accidents | |

In the Tenerife airport disaster collided on the Los Rodeos Airport on Sunday, March 27, 1977 at 17:06 local time, a Boeing 747-206B of KLM Royal Dutch Airlines with a Boeing 747-121 of Pan American World Airways (Pan Am ). A total of 644 people were on board the aircraft. Only 70 inmates of the Pan Am Jumbo survived the collision; of these, nine later died from their injuries. With 583 deaths, the accident is one of the most serious in civil aviation and to date the most serious without direct terrorist impact.

The KLM aircraft took off without take-off clearance and collided with the Pan-Am aircraft , which was still taxiing on the runway , while it was taking off . Visibility impaired by thick fog and the inadequate and ambiguous communication between the KLM pilots and the control room in the tower contributed to the accident .

The accident triggered a series of measures that significantly increased security. Binding formulations for the radio were introduced, airports were equipped with ground penetrating radar and the cooperation between crew members was improved.

prehistory

The American scheduled airline Pan American World Airways (Pan Am) was commissioned by the shipping company Royal Cruise Line with an ad hoc charter flight to Gran Canaria , where the cruise ship Golden Odyssey was to take over the shipping company's passengers. The special flight ( flight number : PA1736, derived from the license plate number of the aircraft used) began in Los Angeles and was routed via New York , where other cruise participants boarded. A crew change took place during this stopover. On the transatlantic flight there were 394 people on board the Boeing 747. The captain in charge was Victor Grubbs.

The Dutch machine operated an IT charter flight under flight number KL4805 on behalf of the Dutch tour operator Holland International Travel Group with 235 passengers and 14 crew members. The aircraft took off at 9:31 am under the command of KLM chief pilot Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten in Amsterdam .

Both planes had the airport of Gran Canaria near Las Palmas as their destination. During the flight, the KLM crew was informed that Gran Canaria airport was temporarily closed due to a bomb explosion in the waiting hall at 12:30 p.m. and a further bomb threat from Canarian separatists . KLM flight 4805, like several other aircraft, was then diverted to Los Rodeos Airport in the north of the nearby island of Tenerife, where the aircraft landed at 1:38 p.m. local time (1:08 p.m. GMT). Pan-Am flight 1736 was also instructed to evade to Los Rodeos, although the crew would have preferred to circling until cleared to land . At least five commercial aircraft were diverted to Tenerife. Los Rodeos Airport had difficulties due to its limited space to accommodate these machines in addition to its own air traffic.

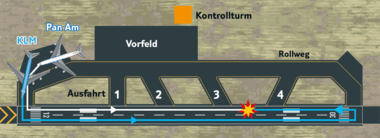

Los Rodeos Airport (former IATA code TCI, today TFN, ICAO code GCXO) has a 3300 m long runway 12/30 (corresponds to an orientation of 120 or 300 degrees) and a parallel main runway, one like this called taxiway, which joins the runway on both sides. In addition, the taxiway is connected to the runway via four short cross lanes. The diverted wide-body aircraft had to park on the western end of the taxiway together with a Boeing 737 from Braathens SAFE , a Boeing 727 from Sterling Airways and a Douglas DC-8 from SATA , so that this section could no longer be used for taxiing.

The passengers of the first aircraft - including the 235 passengers of KLM - were looked after during the waiting time prescribed in Tenerife in the airport terminal , but this was soon so overloaded that the passengers of the aircraft arriving later, as well as those of the 14:15 pm, were taken care of Pm Pan-Am-Jumbos landed, not allowed to leave the machines.

At 2:30 p.m. the blockage of Gran Canaria Airport was lifted. The crew of the US aircraft, whose passengers were still on board, then wanted to continue the flight to Gran Canaria immediately. The Dutch plane in front of her blocked the way to the runway. The US co-pilot and flight engineer stepped onto the tarmac to examine the possibility of taxiing past the KLM-747. They came to the conclusion that there was not enough space between the two machines. After all passengers had been brought back on board the Dutch Boeing 747, the volume of traffic at the reopened airport in Gran Canaria had already increased so much that the departure from Tenerife was delayed further. KLM captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten then decided to have his aircraft refueled in Tenerife for the return flight to Amsterdam in order to save time later at Gran Canaria airport. Refueling with 55,500 liters (around 44.4 tons) of kerosene took another 30 minutes.

Two employees at the airport climbed into the Pan-Am machine and sat on jump seats in the cockpit . A passenger on the KLM plane who was working as a tour guide in Tenerife decided to stay on site and did not return to the plane.

At 4:51 p.m. KLM flight 4805 received permission to start the engines. A minute later, Pan-Am flight 1736 also received clearance to start the engine. Meanwhile, a thick bank of fog had drawn up over the airport. This made work and coordination in the tower much more difficult, as the airport did not have a ground radar and because of the fog there was no longer any visual contact with the aircraft.

the accident

At 4:58 p.m., the KLM crew received clearance from Tower Los Rodeos to taxi via runway 12 to the third junction (referred to as C-3 or Charlie 3 ) and to leave it there. The further taxiway to the opposite end of the train should take place via the parallel taxiway . After the Dutch aircraft had started taxiing and had turned onto the runway, the co-pilot confirmed this instruction incorrectly, so that the air traffic controller gave the instruction to continue on the runway and to turn at the end of the runway in order to get to the take-off position.

17:02 Tower also instructed the Pan Am crew on the runway to rewinding parked aircraft on the runway 12th The US aircraft should then leave the runway via the third cross runway and continue from there on the free section of the taxiway to the start position.

While the Pan-Am-747 was slowly rolling against the current take-off direction on the runway so as not to miss the right turn in the thick fog, the Dutch machine had already turned and was in the take-off position. The KLM crew announced that they were ready to take off and requested ATC clearance . The pilots were then given the departure procedure and the route to Las Palmas to be followed. Such a route clearance does not include a start clearance. This is granted separately.

Meanwhile, the Pan-Am crew missed the junction with the third cross lane and slowly rolled on in the direction of the fourth junction. It remained unclear whether the master overlooked junction C-3 in the fog or deliberately wanted to go to cross runway C-4, which was more convenient for him. Despite poor visibility, he had clearly identified the first two branches.

Although the take-off clearance was still pending, the KLM captain had already started the take-off run at this point, while the co-pilot was still confirming the route clearance to the end. Immediately afterwards, there was an overlap effect on the shared radio frequency: When the tower instructed the KLM crew to wait for take-off clearance, the Pan-Am crew also announced that they were still on the runway. The overlapping radio messages generated a whistling tone in the cockpit of the Dutch aircraft. It is unclear whether and to what extent their crew could understand the radio messages.

Immediately thereafter, the air traffic controller instructed the Pan-Am pilots to report as soon as they had left the runway. The US crew confirmed that they would announce the departure of the train. The KLM flight engineer also heard both radio messages, who then became skeptical and asked his captain whether the Pan-Am-747 was still in the way. Convinced that the track was clear, captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten did not abort the start.

When the pilots of both aircraft finally had visual contact, the Pan-Am crew tried to steer their aircraft to the left of the runway. At the same time, the KLM captain pulled up his aircraft, the rear of the machine touching the ground (see Tailstrike ) and dragging it over the runway for a distance of 20 meters. Both maneuvers narrowly failed. The KLM-747 was able to take off briefly, but collided with the Pan-Am-Jumbo rolling diagonally on the runway. The landing gear and the underside of the Dutch machine penetrated the passenger cabin of the Pan-Am-747 at a 45-degree angle above the right wing and almost completely tore open the part of the passenger deck behind it. The outer right engine of the KLM-747 hit the upper deck of the Pan-Am-Jumbo and was demolished. In addition, the left wing of the Dutch aircraft separated the tail unit of the Pan-Am-747 from the fuselage.

The badly damaged KLM jumbo hit the runway again about 150 meters behind the US aircraft, slid another 300 meters, exploded and burned out completely. All 248 people on board the Dutch Boeing lost their lives.

The Pan-Am-747 rolled on for a brief moment after the collision with the engines running and then broke apart behind the wings. The kerosene leaking from the damaged right wing caused several explosions. Of the 396 occupants, 70 escaped the burning aircraft alive; However, nine of them later died from serious injuries. The pilots were able to escape from the upper deck and survived the accident with minor injuries. Actress and film producer Eve Meyer was also among the victims .

The airport fire brigade was initially only busy with extinguishing the wreckage of the KLM machine. The Pan-Am-747, which was also burning, had not yet been noticed in the thick fog, as it was further back on the runway. Even the tower didn't know that the machine had collided with another. A second fire was only noticed after the extinguishing work had started on the KLM aircraft and, after the fire-fighting forces had been divided up, identified as the second burning aircraft.

Extract from the communication protocol

The following text is the German translation of an excerpt from the communication protocol that was created during the evaluation of the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and the radio recordings of the tower. The pull-out begins shortly after the KLM machine has turned on the starting position. The fog loosens a little and visibility reaches around 700 meters. The KLM captain would like to take this opportunity.

Legend:

Messages transmitted over the air Internal cockpit communication (not audible for the crew of the other machine) Remarks CPT = captain · F / O = first officer · ING = flight engineer · ??? = cannot be assigned · italics = noises and control inputs

| Time (local time) | KLM | Pan Am | ATC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17:05:41 | The thrust levers of the KLM-747 are pushed forward at 17:05:41, the engine pressure ratio increases continuously for all engines. | |||

|

F / O: Wait, [we] don't have an ATC clearance yet. |

||||

| 17:05:44 | F / O: Um, the KLM ... four eight zero five is now ready to go and we are waiting for our ATC clearance. | |||

| 17:05:53 | KLM four eight zero five, um, you have clearance for the radio beacon Papa, climb up and hold flight level nine zero ... right turn after take off Continuing flight course zero four zero to radial three two five from Las Palmas rotary radio beacon. | |||

| 17:06:07 | CPT: Yeah. | |||

| 17:06:09 | F / O: Uh understood, sir, we have clearance to radio beacon Papa flight level nine zero, right turn zero four zero until the intersection of three two five. We are now starting. | |||

| 17:06:12 | The master of the KLM releases the brakes at 17:06:12 and begins the take-off run, while the first officer is still repeating the clearance on the radio. This repetition lasts until 5:06:18 pm; At this point the machine has already reached a speed of 46 knots (85 km / h). | |||

|

CPT: We're going ... check takeoff thrust. Sound of the engines running up |

||||

| 17:06:18 | OK … | |||

| At this point, the signals are superimposed, as the Tower and Pan Am radio simultaneously in the following three passages. This resulted in a high-pitched noise from 17: 06: 19.39 to 17: 06: 23.19. In the opinion of the investigative commission, what was said was still audible. For the report, however, the voice recorder recordings were filtered to improve their quality. It is controversial whether the pilots could understand the following three radio messages. | ||||

| 17:06:19 | CPT: No ... um ... | ... be ready to take off, I'll call you. | ||

| 17:06:20 | Q / O: And we, Clipper one seven three six, are still rolling down the runway. | |||

| The answer from the Pan-Am-Jumbo is a reaction to the ambiguity of the radio message reported by KLM at 17:06:09: “… and we're now at take-off.” (In German: “… and we are now at the start . ") | ||||

| 17:06:25 | Roger, alpha one seven three six, let us know when the runway is clear. | |||

| 17:06:29 | F / O: OK, notify me when the runway is clear. | |||

| 17:06:32 |

ING: So has he not left there yet? |

CPT: Let's get out of here right now. Let's get out of here! (soft laughter) |

Thank you. | |

| 17:06:34 |

CPT: What do you say? |

Q / O: Yeah, he's getting impatient now, huh? |

||

| 17:06:35 | CPT: Of course. (emphatically) | |||

| 17:06:36 |

ING: Yes, first he stops us for an hour and a half, this one (insult) ... |

|||

| 17:06:40 |

CPT: There he is ... look at him ... goddamn ... this ... this ... (insult) is coming. |

|||

| 17:06:43 |

F / O: V 1 . |

|||

| 17:06:45 | F / O: Get out of here! Path! Path! | |||

| Immediately after the first officer of the KLM aircraft had announced that the decision-making speed (V 1 ) had been reached, the flight data recorder recorded that the control horn , which had previously been pushed forward, was pulled slightly in order to take pressure off the nose wheel . Now it is pulled backwards to lift the nose and to the left to avoid the Pan-Am machine. | ||||

| 17:06:47 | CPT: Oh ... (curse) | |||

| 17:06:48 | Engine noise of the approaching KLM-747; Warning tone for poor take-off configuration, as the CPT increases the engine power in order to steer the aircraft off the runway | |||

| 17:06:49 | Impact noise | |||

| 17:06:50 | Impact noise | |||

Investigation report

The report of the investigative commission came to the conclusion that the following reasons led to the accident:

- The master of the KLM machine initiated the take-off without clearance.

- He disregarded the instruction “stand by for take off”.

- He did not abort the start when the Pan-Am machine announced that it was still on the runway.

- At the flight engineer’s request, he expressly confirmed that the Pan-Am machine had already left the runway.

The report gives as possible reasons why the captain might have made these mistakes:

- Due to the weather conditions and the strict Dutch working time regulations, there was a risk of not being able to take the onward flight. The master of the KLM machine was therefore under increasing pressure.

- Instead of fog, there were several low cloud layers at the time of the accident. If these are moved by the wind, drastic changes in visibility can occur very quickly. These conditions make it harder for the pilots to make a decision.

- Due to the overlay in radio traffic, the message was not transmitted with the desired clarity.

The following factors also contributed to the accident, according to the report:

- The misleading formulation of the KLM co-pilot “we are now at take-off”, which meant that the controller did not notice that the KLM machine was starting the start-up process.

- The Pan-Am machine did not leave the runway at the third junction and neither did its pilots ask which junction was the right one. However, since the Pan-Am crew did not report the runway as free, but instead indicated that they were still on the runway twice, this reason is of secondary importance.

- Due to the high volume of traffic, the tower was forced to open up permissible, but unusual and therefore potentially dangerous taxiways for use.

In addition, the report explicitly mentions factors that had no direct influence on the accident:

- The incident in Las Palmas.

- Refueling the KLM machine.

- The start of the KLM machine with reduced performance.

The Dutch Aviation Authority noted that the accident was the result of a chain of circumstances. Misunderstandings have arisen from common procedures, terminology and behavioral patterns. None of the parties involved would have made a serious mistake.

An investigation by the American pilots' association ALPA focused on the human factor of the accident and came to a number of other conclusions: The exchange of information had been made difficult by communication problems, including accents and idioms . The training syndrome (for example: trainer syndrome) could have resulted in the KLM captain, who is usually employed as trainer, having problems correctly grasping the real situation. Since the KLM crew asked for take-off and route clearance at the same time, they may have assumed that the route clearance issued also included the take-off clearance. Since the pilot's answer contained the word take-off , this assumption was reinforced. The report also considers it possible that the first officer of the KLM plane actually said now uh taking off instead of we're now at take-off .

Consequences

From the investigation of the accident and its causes, numerous consequences were drawn and implemented:

- Clearer and largely standardized formulations (" speaking groups ") were prescribed for radio communications . Since then, a crew has requested take-off clearance with “ready for departure” (in German aeronautical radio: “ready for departure”), the control tower issues it with the phrase “cleared for take-off” (in German aeronautical radio: “Start frei”) the crew is confirmed; only then may the take-off run be started. This means that the term “take-off” (German: “start”) appears solely in the controller's take-off clearance to the aircraft (and in the confirmation from the crew). In all other cases and in free formulations, “departure” is used. This means that, on the one hand, other radio messages can no longer be misunderstood as clearance for take-off, and on the other hand, the key word “take-off” clearly indicates the beginning of a take-off run to the other traffic.

- International airports have been equipped with ground radar to enable monitoring of the runway and runway even in poor visibility.

- The accident in Tenerife also triggered the development of Crew Resource Management and brought about a fundamental expansion of priorities in pilot training: Not only did you begin to train your flying skills, but also the ability to work in a team. Objections by the crew must be taken seriously and checked by the flight captain, and lower-ranking crew members must also be included in decisions.

- The airline KLM changed its working hours rules for staff to reduce the stress of time pressure.

Even before the accident, the planning and construction of a second airport in the south of the island began in the 1970s. This should relieve the Los Rodeos airport in the north of Tenerife, which is also subject to operational restrictions due to the frequently occurring dangerous fog. The Tenerife "Reina Sofía" airport (TFS) was opened in November 1978 and wrapped by now, most commercial domestic and international flights from.

Memorials

Memorial in La Laguna

On March 27, 2007, the 30th anniversary, the “Spiral Staircase” memorial was unveiled in memory of the victims on the Mesa Mota hill in the Tenerife city of La Laguna , from where one can see the Los Rodeos North Airport (position: 28 ° 30 ′ 24.51 ″ N , 16 ° 19 ′ 6 ″ W ). The relatives' foundation of the victims from the Netherlands commissioned the memorial and the city of La Laguna made the property available. The memorial is an 18-meter-high steel construction in the form of a spiral staircase designed by Reindest Wepko van de Wint , which seems to screw itself endlessly into the sky, symbolizing eternity. After a long, unsubstantiated closure of the monument to the public, the memorial has been open to visitors again since July 2010 during the summer months from 9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.

Memorial and burial ground in the Westgaarde cemetery

The KLM Royal Dutch Airlines put on near the Dutch Schiphol airport located cemetery Westgaarde to a cemetery where 123 victims were buried. Around a granite stone with the inscription “Tenerife 27 maart 1977” are flat stones on which there are copper strips with the names of the victims.

Community grave at Westminster Memorial Park

In a common grave at the Westminster Memorial Park , California Westminster 114 unidentifiable victims were buried that aboard the Pan Am plane had been.

Movies

- Airplane crash when taking off. (Original title: Collision on the Runway ). Seconds before the accident [Season 1; Episode 12].

- Misfortune in Tenerife. (Original title: Disaster at Tenerife ). Mayday alarm in the cockpit [Season 16; Episode 3].

Web links

- Aviation Safety Network : Aircraft accident data and reports from the PanAm and KLM aircraft as well as transcripts of radio communications in the original language

- Final reports from the Spanish and comments from the Dutch authorities

- (EN) Final report and comments from the Netherlands Aviation Safety Board, KLM, B-747, PH-BUF and Pan Am, B-747, N736, collision at Tenerife Airport, Spain, on 27 March 1977 (PDF; 5,6 MB). (PDF) Raad voor de Luchtvaart based on ICAO, Cicular 153-AN / 98, Aircraft Accident Digest No. 23, pp. 22-68, 1980, accessed March 28, 2017 .

- (ES) A-102/1977 y A-103/1977 Accidente Ocurrido el 27 de Marzo de 1977 a las Aeronaves Boeing 747, Matrícula PH-BUF de KLM y Aeronave Boeing 747, matrícula N736PA de PANAM en el Aeropuerto de los Rodeos, Tenerife (Islas Canarias). Subsecretaría de Aviación Civil, Dirección General de Transporte Aéreo, Comisión de Accidentes, July 12, 1978, accessed April 1, 2017 .

- (EN) Comments from the Netherlands Department of Civil Aviation (PDF; 88 kB). (PDF) Raad voor de Luchtvaart, July 31, 1979, accessed April 1, 2017 .

- (NL) Uitspraak van de Raad voor de Luchtvaart (PDF; 79 kB). (PDF) Raad voor de Luchtvaart, July 31, 1979, accessed April 1, 2017 .

- Pan Am Accidents: Clipper Victor - Tenerife, Spain. Archived from the original on December 15, 2014 ; accessed on March 28, 2017 (English).

- Tenerife Memorial. Retrieved April 8, 2017 (English, Spanish, Dutch).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ministerio de Transportes y Communicaciones (ed.): Joint Report KLM-PAA July 12, 1978 . Madrid July 12, 1978 (English, project-tenerife.com [PDF; 6.3 MB ; accessed on April 9, 2017]).

- ^ A b Stanley Stewart: Air Disasters . 1st edition. Hippocrene Books, 1987, ISBN 978-0-87052-385-4 , pp. 148-159 (English).

- ↑ a b David Gero: Aviation Disasters . Patrick Stephens Limited, Somerset 1993, ISBN 978-1-85260-379-3 , pp. 138-141 (English).

- ↑ CVR Transcript (Annex 5) . In: Ministerio de Transportes y Communicaciones (ed.): Joint Report KLM-PAA July 12, 1978 . Madrid 1978 (Spanish, English, project-tenerife.com [PDF; accessed April 4, 2017]).

- ^ Air Line Pilots Association: Aircraft Accident Report, Pan American World Airways Boeing 747, N 737 PA, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines Boeing 747, PH-BUF, Tenerife, Canary Islands, March 27, 1977 . Washington, DC 1979, p. 32 ff . (English, project-tenerife.com [PDF; accessed April 4, 2017]).

- ↑ Project Tenerife: Dutch comments on the Spanish Report. (PDF) In: project-tenerife.dk. 2009, accessed April 9, 2017 .

- ^ Air Line Pilots Association: Aircraft Accident Report, Pan American World Airways Boeing 747, N 737 PA, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines Boeing 747, PH-BUF, Tenerife, Canary Islands, March 27, 1977 . Washington, DC 1979 (English, project-tenerife.com [PDF; accessed April 9, 2017]).

- ↑ Spiral staircase to eternity. In: Wochenblatt - The newspaper of the Canary Islands. Wochenblatt SL, March 25, 2007, accessed April 8, 2017 .

- ↑ 40 years after the plane disaster in Tenerife. In: Wochenblatt - The newspaper of the Canary Islands. Wochenblatt SL, March 22, 2017, accessed April 8, 2017 .

- ↑ Painful memory. In: Wochenblatt - The newspaper of the Canary Islands. Wochenblatt SL, April 6, 2007, accessed April 8, 2017 .

- ↑ International Tenerife Memorial. In: tenerife-memorial.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016 ; Retrieved April 8, 2017 (English, Spanish, Dutch).

- ↑ Leon Bok: Monuments voor de vliegramp op Tenerife. In: stichting Dodenakkers.nl. July 3, 2010, archived from the original on March 2, 2017 ; Retrieved April 8, 2017 (Dutch).

- ↑ Tenerife Airport Disaster Memorial. In: findagrave.com. April 17, 2001, accessed April 8, 2017 .

- ↑ Mass burial for 114 victims of Canary Islands plane crash . In: The Stanford Daily . tape 171 , no. 51 , April 28, 1977, pp. 3 (English, stanforddailyarchive.com [accessed April 8, 2017]).

- ^ Picture of the communal grave in Westminster Memorial Park. In: findagrave.com. Retrieved April 8, 2017 .

- ↑ Collision on the Runway in the Internet Movie Database .

- ↑ Disaster at Tenerife in the Internet Movie Database .

Coordinates: 28 ° 28 ′ 55 ″ N , 16 ° 20 ′ 21 ″ W.