tomato

| tomato | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tomato ( Solanum lycopersicum ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Solanum lycopersicum | ||||||||||||

| L. |

The tomato ( Solanum lycopersicum ), in parts of Austria and South Tyrol also tomatoes (rare Paradeisapfel or Paradiesapfel ), is a plant from the family of the nightshade family (Solanaceae). It is therefore closely related to other edible plants such as the potato ( Solanum tuberosum ), the paprika ( Capsicum ) and the aubergine ( Solanum melongena ), but also to plants such as the deadly nightshade , mandrake , angel's trumpet , petunia or tobacco ( Nicotiana ).

Long known as the love apple or gold apple (hence the Italian name "pomodoro"), it was not until the 19th century that it was given the name "tomato" which is used today. This is derived from xītomatl , the word for this fruit in the Aztec Nahuatl language . Colloquially, the red fruit used as a vegetable , which is a berry, is called a tomato. Former botanical names and synonyms: Lycopersicon esculentum, Solanum esculentum or Lycopersicon lycopersicum .

description

Vegetative characteristics

The tomato plant is an herbaceous , annual , biennial or occasionally perennial that initially grows upright, but later grows prostrate and creeping. The individual branches can be up to 4 m long. The stems have a diameter of 10 to 14 mm at the base, they are green, finely haired and usually tomentose towards the tip. The hair consists of simple, single-celled trichomes , which are up to 0.5 mm long, as well as sparsely distributed, mostly consisting of up to ten cells, multicellular trichomes with a length of up to 3 mm. The longer trichomes in particular often have glandular tips that give the plant a strong odor.

The sympodial units usually have three leaves , the internodes are 1 to 6 cm long, sometimes longer. The leaves are interrupted, pinnate unpaired, 20 to 35 cm (rarely only 10 cm or more than 35 cm) long and 7 to 10 cm (rarely only 3 cm or more than 10 cm) wide. They are sparsely hairy on both sides, the trichomes resemble those of the stems. The petiole is 1.2 to 6 cm long or sometimes longer.

The main part leaves are in three or four (rarely five) pairs. They are egg-shaped or elliptical in shape, the base is oblique and running down to the base of the entire leaf, cut off or heart-shaped. The margins are particularly serrated or notched near the base, rarely they are entire or deeply serrated or lobed. The tip of the partial leaves is pointed or acuminate. The top leaf is usually larger than the side leaf, 3 to 5 cm long and 1.5 to 3 cm wide. The stem is 0.5 to 1.5 cm long. The tip is usually pointed. The lateral partial leaves are 2 to 4.5 cm long and 0.8 to 2.5 cm wide, they are on 0.3 to 2 cm long stalks.

The sub-leaves of the second rank are mostly on the side of the lower main part leaves facing the leaf tip. They are 0.2 to 0.8 cm long and 0.1 to 0.5 cm wide, they are sessile or stand on a stalk up to 0.4 cm long. Partial leaflets of the third rank are missing. There are usually six to ten interleaved leaflets between the main leaves. These are 0.1 to 0.8 cm long and 0.1 to 0.6 cm wide and are on 0.1 to 0.3 cm long stalks. Mock secondary leaves are not formed.

Inflorescences and flowers

The inflorescences are up to 10 cm long, consist of five to fifteen flowers and are mostly undivided or rarely split into two branches. The peduncle is shorter than 3 cm and hairy similar to the stems. The flower stalks are 1 to 1.2 cm long, the outer third is divided like a joint. The shape of the inflorescence is a wrap .

The buds are 0.5 to 0.8 cm long and 0.2 to 0.3 cm wide and straight conical in shape. Before blooming, the crown protrudes about halfway from the calyx . The calyx tube is very fine during flowering and covered with calyx lobes up to 0.5 cm long. These are linearly shaped, pointed towards the front and covered with long and short, simple, single-row trichomes. The bright yellow, pentagonal crown has a diameter of 1 to 2 cm, it is often banded and, in some cultivars, has more than five lobes. The corolla tube is 0.2 to 0.4 cm long, the corolla lobes are 0.5 to 2 cm long, 0.3 to 0.5 cm wide, narrowly lanceolate and sparse with intertwined, single-row trichomes at the tip and the edges occupied by up to 0.5 mm in length. During the flowering period, the corolla lobes are protruding.

The stamens are fused to form a tube, this is 0.6 to 0.8 cm long and 0.2 to 0.3 (rarely up to 0.5) cm wide. It is narrow, conical and straight. The stamens are very fine and only 0.5 mm long, the anthers are 0.4 to 0.5 cm long and have a sterile appendix at the tip that is 0.2 to 0.3 cm long and never more than that Makes up half of the total length of the anthers. The ovary is conical, finely hairy glandular. The stylus is 0.6 to 1 cm long and less than 0.5 mm in diameter. It usually does not protrude beyond the stamen. The scar is heady and green.

Fruits and seeds

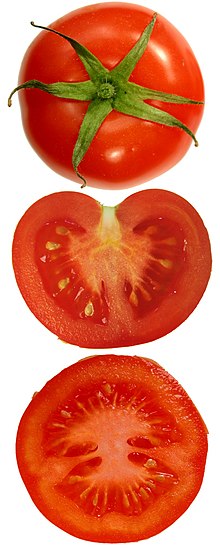

The fruits are berries , usually measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter, but can also be up to 10 cm in size in cultivated plants. Since the fruit is made up of two carpels, it has two chambers with numerous ovules. These are connected via a centrally located, placental tissue. The number of carpels and thus the number of chambers can vary, mainly due to breeding. The fruit shape is mostly approximately spherical, other growth forms such as oval-elongated or pear-shaped are also possible, also due to breeding.

The fruits ripen due to the carotenoid content and especially the lycopene to a strong red, yellow or dark orange, are initially hairy, but when ripe they become bald. The flower stalk has enlarged to 1 to 3 cm in length by the time the fruit is ripe, and in varieties with large fruits it is often thickened. It is straight or curved at the hinge point in the direction of the inflorescence axis. The calyx is also enlarged on the fruit, the calyx lobes are about 0.8 to 1 cm long and 0.2 to 0.25 mm wide and sometimes strongly bent backwards.

The fruits contain a wide variety of seeds . These are 2.5 to 3.3 mm long, 1.5 to 2.3 mm wide and 0.5 to 0.8 mm thick. They are inverted ovoid, pale brown and covered with hair-like outgrowths on the outer cells of the seed coat. These are either close-fitting and give the seeds a velvety surface or they are shaggy. The seeds are narrow at the tip (0.3-0.4 mm) winged and pointed at the base. The seed coats are made in the extreme range of cells strongly verschleimendem epithelium , which botanically Myxotesta is called. Between the individual seeds there is a gel-like tissue that is formed by the placenta.

Chromosome number

The number of chromosomes is 2n = 24.

Systematics

Within the nightshade ( Solanum ) the tomato is classified in the subgenus Solanum and within this in the section of the tomatoes ( Solanum sect. Lycopersicon ). Within this section, the species forms the Lycopersion group together with Solanum pimpinellifolium , Solanum cheesmaniae and Solanum galapagense , all of which develop red to orange-colored fruits .

To subdivide the species, various approaches have been followed, especially since the 20th century, but none of them succeeded. Small, red and yellow fruits were often referred to as Solanum lycopersicum var. Cerasiforme or Lycopersicon esculentum var. Cerasiforme (often colloquially known as "cherry tomatoes"). It was assumed that these correspond to the wild form of the species Solanum lycopersicum or are at least very close to it. However, they are probably breeds and in some cases crosses with wild tomato species such as Solanum pimpinellifolium . These and all other varieties within the species are not recognized and are only used as a synonym for Solanum lycopersicum .

history

The area of origin of the tomato is Central and South America , with the wild forms from northern Chile to Venezuela being common and native. The original domestication of the tomato has not been clearly clarified: the Peruvian hypothesis and the Mexican hypothesis exist. The greatest variety of forms in culture is found in Central America. There tomatoes were bought by the Maya and other peoples around 200 BC. Cultivated until 700 AD as "Xītomatl" ( Nahuatl for the navel of thick water ) or "Tomatl" for short ( thick water ). Seeds were found in excavations south of Mexico City in caves in the Tehuacán Valley.

The tomato is one of the hemerochoric plants in Europe due to its introduction by humans and one of the neophytes due to its introduction only in modern times (probably around 1500 by Columbus) . However, the tomato can only be described as a temporary neophyte, as it is extremely rare and temporarily found in the wild in Europe; essentially it is cultivated.

History of the tomato in Europe

The first tomato plants came to Europe very soon after the conquest of Central and South America. They were first brought to Spain at the beginning of the 16th century by the Spaniard Hernán Cortés after the conquest of Mexico. It was referred to as "tomato" based on its Aztec name.

The first European descriptions of the plant date from the first half of the 16th century, mainly from Italy. In 1544 the Italian Pietro Andrea Mattioli was one of the first to provide a more detailed description. He described the tomato as a yellow fruit and compared it to the melrose . In 1554 he refined his first description, he reported on varieties with red fruits and for the first time gave an Italian name for the tomato: "pomi d'oro". In 1586, after Mattioli's death , Camerarius published a revised edition, which was expanded to include a woodcut of a tomato plant, among other things.

Spanish possessions such as Sardinia or Naples played an important role in the spread of the tomato into what is now Italy. Returning colonists probably brought the new fruits with them to Spain in the form of seeds, and from there they reached Italy. The history of the tomato in Italy began on October 31, 1548, when the Tuscan Grand Duke Cosimo di Medici received a basket full of tomatoes from his estate for the first time.

The herbarium “En Tibi Herbarium” from around 1555, kept in Leiden, contains a herbarium record for the oldest tomato in Europe. The earliest herbarium records from Aldrovandi and Oelinger also go back to the 16th century. Both cultivated tomatoes. There are many other mentions from the 16th century, including Dodoens and Gessner . The latter mentioned that tomatoes grow well in Germany, ripen early and that the fruits have different colors.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, tomato plants were planted as rarities in the gardens of the upper class. Since they were rare, they symbolized prosperity and impressed visitors. Across Europe, tomatoes were mainly used as ornamental plants because it was believed that their fruits were inedible or even poisonous. This attitude changed over the course of the 17th century as medicine advanced.

History of the tomato in Italy

After the first appearance of the tomato in Italy in 1548/1555, the tomato plants decorated the Italian gardens primarily as ornamental plants, as they were considered poisonous due to their similarity to the nightshade family. But even the Medici , who incidentally included the tomato in their family coat of arms, were interested in using the tomato for consumption. Although Mattioli gave a recipe for the consumption of tomatoes as early as 1544, the literature doubts that it was really often used as a food plant.

In Italy in particular, the tomato became increasingly important from the 17th century. Antonio Latini worked as a cook for the Spanish viceroy of Naples from 1658. In the cookbook he wrote, there were also recipes with New World ingredients for the first time. The three dishes in which the tomato appeared were called "alla spagnola". Around 1700 people began to appreciate the tomato as an ingredient in food; Italy was once again considered a pioneer.

Distribution in the rest of Europe

Joachim Kreich, pharmacist in Torgau , founded a botanical garden famous in Germany in 1543 , which the Moser family of pharmacists continued until it was destroyed in the Thirty Years' War in 1637. Kreich was one of only four known tomato owners in what was then Germany. Since no uniform system for the scientific naming of living beings was used at that time, the tomato appeared in the literature of the time under a variety of different names, including “mala peruviana”, “pomi del Peru” (Peruvian apple), “poma aurea” "," Pomme d'Amour "," pomum amoris "(candy apple) or compound names such as" poma amoris fructo luteo "or" poma amoris fructo rubro ".

Botanists established the connection to the genus Solanum early on , so that the tomato was often referred to as Solanum pomiferum . In 1694 the name Lycopersicon was first used by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort . Carl von Linné assigned the tomato to the genus Solanum again in his work " Species Plantarum " and described the cultivated tomato as Solanum lycopersicum and the wild tomatoes as Solanum peruvianum . As a result, the tomato was repeatedly described by various authors either as a separate genus Lycopersicon or as part of the genus Solanum . Based on current DNA sequence analyzes and morphological studies, almost all sources attribute the tomato to the genus Solanum today .

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the tomato was mainly seen as an ornamental plant in Europe; only a few medicinal uses are known. However, an English translation of Tournefort's book Éléments de botanique mentions in 1719 that the fruits are eaten in Italy. As early as the end of the 18th century, the Encyclopædia Britannica described the use of tomatoes in the kitchen as "commonplace".

Around 1900 the tomato was also known as a food in Germany and was mainly used in the south in sauces , soups and salads .

Tomatoes were shown at the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873 . The first tomatoes appeared on the Viennese markets around 1900. However, they did not find their way on a large scale until 1945. In Seewinkel ( Burgenland ) had settled as seasonal workers has come Bulgarians, who brought with them also the necessary for the cultivation of knowledge. Due to the widespread aversion to the unknown and the harsher climatic conditions, tomatoes did not spread in the western federal states of Austria until the 1950s or even later. In some alpine valleys they only came with the construction of the first supermarkets.

In 1961 around 28 million tons of tomatoes were produced worldwide.

In the 1990s, the Flavr Savr tomato was the first genetically modified tomato to hit the market. The first tomato variety with an open source seed license was launched in 2017 under the name Sunviva . Thanks to the open source license, the seeds can be propagated further and used for their own breeding if these are also placed under the license.

Diseases

Diseases and growth disorders in tomato plants can have different causes. The most important and common are:

Fungal attack by Phytophthora infestans ( late blight and brown rot ), Alternaria solani ( dry spot disease ), Stemphylium solani (Stemphylium leaf spot disease), Cladosporium fulvum (velvet and brown spot disease), Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici ( Fusarium wilt ), Verticillium albo-atrum ( verticillium wilt ), Botrytis cinerea (gray mold), Phytophthora parasitica , Alternaria tomato , Septoria lycopersici , Sclerotium rolfsii , Colletotrichum species, Botryosporium species, Didymella lycopersici (Didymella stem rot) ;

Bacterial attack by Xanthomonas campestris pv. Vesicatoria , Clavibacter michiganensis ssp. michiganensis ;

Viral infections

Nutrient deficiency and unfavorable growth conditions with various damage patterns , for example flower end rot (mostly physiological calcium deficiency ), bursting of the fruits (too fast growth especially after stress), micro-cracks;

Animal pests Spider mites , whiteflies , aphids , caterpillars , thrips , tomato leaf miner ( Tuta absoluta ).

Economical meaning

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization FAO, around 182 million tons of tomatoes were harvested worldwide in 2018 .

The following table provides an overview of the 20 largest tomato producers worldwide, who produced 86.1 percent of the total.

| rank | country | Quantity (in t ) |

rank | country | Quantity (in t) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

61,523,462 | 11 |

|

3,913,993 | |

| 2 |

|

19,377,000 | 12 |

|

2,899,664 | |

| 3 |

|

12,612,139 | 13 |

|

2,324,070 | |

| 4th |

|

12,150,000 | 14th |

|

2,324,070 | |

| 5 |

|

6,624,733 | 15th |

|

1,409,437 | |

| 6th |

|

6,577,109 | 16 |

|

1,357,621 | |

| 7th |

|

6,577,109 | 17th |

|

1,330,482 | |

| 8th |

|

4,768,595 | 18th |

|

1,309,745 | |

| 9 |

|

4,559,375 | 19th |

|

1,068,495 | |

| 10 |

|

4,110,242 | 20th |

|

976.790 | |

| world | 182.256.460 |

In 2018, a total of 23,291,126 tons were harvested in Europe. The largest producers in the EU are Italy, Spain and Portugal. In Germany 103,266 t, in Austria 58,154 t and in Switzerland 43,243 t were harvested.

The Netherlands produced around 910,000 tonnes in 2018, but leads the yield per hectare statistics (over 508 tonnes per hectare) thanks to intensive greenhouse cultivation.

In 2018, 4,762,457 hectares of production area were planted with tomatoes worldwide. The average yield per hectare was 38.2 tons.

cultivation

Varieties and breeding goals

Worldwide there are more than 3,100 varieties and at least as many breeder varieties that were never registered and therefore never received a name. The number of new varieties added each year is also considerable.

When selecting new varieties, the following breeding goals are usually in the foreground: loose growth, high resistance and / or tolerance to environmental influences, diseases, pests and viruses, good productivity, high yield, fast fruit development, reliable fruit set even in unfavorable climatic conditions, uniform sorting, certain Size and weight, uniform color and color itself, good taste and high content of important ingredients, good transportability and fruit firmness, long shelf life (see also: mash tomato ), general use- specific suitability.

Often tomatoes are bred to survive a long transport from southern (western) Europe; this is at the expense of other properties, especially taste.

Classification according to types

Fruit shape round and smooth (normal tomato), flat round and smooth (mostly beefsteak tomato), flat round and wrinkled ( cuore di bue in northern Italy), heart-shaped (Russian cuore di bue ), oval or plum-shaped (date and egg tomato, mostly in cherry or Cocktail area ), pear-shaped (cherry tomato ), oblong (bottle tomato , e.g. San Marzano tomato and Andean horn ), consisting of several individual parts (travel tomato).

Size It depends heavily on the number of fruit chambers (chambers). Cherry tomatoes (2–3), normal tomatoes (3–5), cuore di bue (4–10), beefsteak tomatoes (3–6), San Marzano tomatoes, giant tomatoes (up to 1 kg).

Color white, yellow, orange, red, pink, purple, green, brown, black. But striped and marbled tomatoes are also known.

Color distribution unicolor (UC), bicolor (BC) mostly with a green approach to the stem, mackerel / spotted.

Growth type growing indefinitely (indeterminate) or growing to a limited extent (determined), as a bush or stake tomato (also on a string).

Ripeness type early, medium or late ripening ( producing the first red tomato), to be harvested as loose tomatoes or truss tomatoes (panicle tomatoes).

Use of ornamental plants, hobby cultivation, self- pickers , direct sales and marketers , wholesale marketing or industrial utilization , suitability for drying , storability.

Harvesting suitability Mechanical harvesting for industry, loose without calyx, loose with calyx, baggage train / cluster / panicle, baggage train / cluster jointless (stem without predetermined breaking point).

Success factors

So that the tomato culture leads to a good result, the following factors must be optimized: resistant and tolerant varieties, balanced, continuous supply of nutrients, lots of light, sufficient warmth, good soil structure up to a depth of about 50 cm, no fresh liming for soil culture , warm soils (temp. > 14 ° C), harvest as early as possible and even watering for even growth. Uneven irrigation leads to a hardening of the skin in phases with a low water supply, which means that it is no longer elastic enough to follow the growth of the fruit in subsequent phases with a high water supply. The result is an increased burst of tomatoes. Recent research has shown that tomatoes grown with diluted seawater contain an increased amount of important nutrients while consuming less valuable drinking water.

Developments in tomato cultivation

In recent years, especially in organic farming , a large number of no longer known ancient varieties that originate from the beginnings of tomato cultivation have been rediscovered. The tomatoes are usually harvested by hand and cost more than 10 euros per kilogram. Such an assortment was launched a few years ago by a large retail chain in Switzerland (as part of the ProSpecieRara program; 138 different types of tomato), in Germany such varieties are also available in specialist shops as wild tomatoes . The old tomato varieties often convince with their taste and, despite the high price, attract a small layer of lovers and casual buyers. At the beginning of the 21st century, however, only small markets were opened up for such “exotic” vegetables. They were rated more as niche products for the hobby sector and by direct marketers for enthusiasts. However, the organic wholesalers in Europe also supply the affiliated specialist shops with larger batches of the somewhat forgotten forms and cultivars of the “paradise apples”.

The Austrian farmer Erich Stekovics in Frauenkirchen (Burgenland) owns the seeds of 3,200 tomato varieties and offers 500 varieties of tomatoes for sale on his farm.

There are also varieties of Tross tomatoes that no longer have a “predetermined breaking point” (small thickening on the fruit stalk). This means that individual fruits no longer break off unintentionally. These varieties are also bred so that the fruit itself holds better on the calyx. Therefore, such varieties are not suitable for single crop harvest. This stem is called jointless . When improving the quality of tomatoes, breeding is increasingly focusing on the internal and external qualities of the fruit. In the USA, for example, the lycopene content and in Europe especially the taste play an important role. The latter is determined by the sugar content ( Brix ), the acid content and by taste tests by trained taste testers, and stated in test results. These quality controls and breeding trends have resulted in good varieties that show strong colors, taste better, and are more suitable for marketing than traditional varieties.

A number of very small tomatoes, such as currant tomatoes and cherry tomatoes, are grown primarily in allotment gardens.

Crossing and grafting with other nightshade plants

In EU agricultural trials, the crossing of the tomato with the genetically closely related potato to form the so-called Tomoffel is tried again and again in order to further increase the yield - but so far with only moderate success, as the plants cultivated have always been too weak to be equally high-energy edible To be able to develop tubers and edible fruits. Even in earlier years, tomatoes were grafted onto potatoes, which is quite easy in the short term, but in the long term it depletes the plant and thus destroys it. This combination will probably always remain difficult, since the formation of the storage organs of the potato, as well as for large fruits on the tomato at the same time, requires considerably more leaf mass than the tomato can produce. Foliage is needed to store enough carbohydrates through photosynthesis. The tuber and the above-ground fruit compete. Therefore, this wish is not a very sensible combination if high yields are to be achieved on both sides.

The use of tomatoes as a refining base for eggplants is of greater importance . Wild tomato hybrids ( Solanum lycopersicum × Solanum habrochaites ) are used as bases . Most of the grafting of tomatoes is carried out on tomato bases to prevent nematode and cork root disease . Tomato refinement sets are now available in stores and can therefore also be used successfully by hobby gardeners.

Bumblebees as pollinator insects

Tomatoes are so-called vibratory pollinators . In order to achieve a fruit set here, labor-intensive manual pollination with electrical pollinators was necessary in the greenhouse cultivation of tomatoes until the 1980s. In Europe in the 1980s this resulted in labor costs of around € 10,000 per hectare .

In 1985, the Belgian veterinarian and hobby entomologist Roland de Jonghe released a nest of dark bumblebees in a greenhouse where tomatoes were growing, and found that they were very effective at pollinating the plants. It was succeeded while in 1912, Hummel queens in captivity to keep so that they began to build their nest, and in the 1970s were so advanced experience with the artificial breeding and maintenance under captivity conditions of bumblebees that one was able to go through a complete annual cycle for individual bumblebee species . The dark bumblebee in particular seemed to be particularly easy to raise under artificial conditions. It was not until de Jonghe, however, that the potential commercial importance of the use of bumblebees as a pollination practice was recognized, which in little more than a decade changed the form of tomato cultivation under glass. Compared to the costs of the high manual effort involved in pollination, the costs of the labor-intensive breeding of bumblebees were low. De Jonghe also found that plants pollinated by bumblebees were more productive.

In 1987 De Jonghe founded Biobest , which is still the largest commercial breeder of bumblebees to this day. In 1988, the company raised just enough bumblebees to pollinate 40 acres that were grown tomatoes. However, as early as 1989 they started exporting bumblebees' nests to Holland, France and Great Britain. In 1990, artificially reared bumblebees were used for the first time in Canada, followed a year later by the USA and Israel and a little later by Japan and Morocco. By the turn of the millennium, it had become the global standard to rely on the pollination of bumblebees when growing tomatoes. Exceptions are countries like Australia, where bumblebees do not occur naturally and where the legislation strictly prohibits the import of non-native species.

In the practice of pollination with bumblebees, complete bumblebees' nests are brought into the greenhouses. The European companies that are active in artificial bumblebee breeding send more than a million bumblebee nests worldwide every year. One of the positive side effects of using bumblebees in agricultural vegetable growing is a significantly reduced use of insecticides and pesticides, as the use of these agents also endangers pollinators. The disadvantage is that the artificially reared bumblebees are predominantly descendants of dark earth bumblebees collected in Turkey. When bumblebees are used in greenhouses, it is almost inevitable that bumblebees escape, reproduce successfully and thus influence the respective regional fauna. The practice required in Great Britain of either burning such imported nests after their use or killing the bumblebees by placing the nests in freezers is seldom implemented there , according to the experience of the British entomologist Dave Goulson . Few vegetable growers have sufficiently large freezers, and burning the nests, which are made of cardboard, plastic and polystyrene , creates annoying exhaust gases.

In Japan, it is a legal requirement that greenhouses using bumblebees' nests have double doors and meshed hatches to prevent bumblebees from escaping. In the meantime, however, there are feral dark bumblebees in Japan that go back to escaped bumblebees . The experiences in South America are even more serious: Dark bumblebees that have escaped from Chilean greenhouses have been spreading invasively over the South American land mass at a speed of around 200 km per year since 1998 . On their way, for example, the native bumblebee species Bombus dalbomii disappears regionally a few years after the arrival of the dark bumblebee. The unicellular parasite Crithidia bombi also came to the continent with the industrially bred bumblebees . It is believed that the combination of bumblebee and parasite is displacing the native bumblebee species with such great speed.

Use as food

| Nutritional value per 100 g tomatoes, raw | |

|---|---|

| Calorific value | 84 kJ (20 kcal) |

| water | 93 to 95 g |

| protein | 1 g |

| carbohydrates | 4 g |

| - of which sugar | 2.6 g |

| - fiber | 1.2 g |

| fat | 0.3 g |

| Vitamins and minerals | |

| Vitamin B 1 | 0.09 mg |

| Vitamin B 2 | 0.04 mg |

| Vitamin B 3 | 0.5 mg |

| vitamin C | 38 mg |

| Calcium | 11 mg |

| iron | 0.6 mg |

| magnesium | 10 mg |

| sodium | 3 mg |

| phosphorus | 27 mg |

| potassium | 280 mg |

| zinc | 0.24 mg |

ingredients

The main component of the tomato is water (around 95 percent), it also contains vitamins A , B1 , B2 , C , E , niacin , secondary plant substances and minerals, especially potassium and trace elements. In addition to the vitamins mentioned, the tomato contains biotin , folic acid , thiamine and pantothenic acid ; Alpha & beta carotene , potassium, chlorogenic acid , citric acid , glycoalkaloids, glycoproteins, lignin , lutein , lycopene (only in red tomatoes), p -umaric acid , 10 trace elements (chromium), especially silicon ; Tyramine , zeaxanthin .

The shell (tomato skin) contains polysaccharides and cutin , inter alia, hydrocarbons ( higher alkanes such as n-nonacosane, n-triacontane and n-hentriacontane), fatty acids ( palmitic -, stearin - oil - linoleic - and linolenic acid ) and triterpenes (α - and β-amyrin) and sterols ( β-sitosterol , stigmasterin ). The tomato skin contains a particularly large number of active ingredients (flavonoids).

The carotenoid lycopene gives tomatoes their red color. The name is derived from the Latin name of the tomato Solanum lycopersicum . Ripe tomatoes have a lycopene content of 4 to 5.6 mg per 100 g of fruit. Lycopene is a carotenoid that has an antioxidant effect and is said to strengthen the immune system and reduce the risk of certain cancers . The calorific value of tomatoes is relatively low at around 75 kJ per 100 g. Tomatoes are used in large quantities to make tomato paste , as well as tomato juice , tomato sponge and tomato ketchup .

Although the tomato is a food, the herb, the stalk and the green part is the fruit by the contained tomatidine (corresponding to the solanine potato) slightly toxic, that is indigestible. Eating the herb or very unripe fruits can cause nausea and vomiting. It is therefore also recommended by some sources to remove green parts and the base of the stalk when preparing meals.

However, there are also tomato varieties that are naturally green on the outside - e.g. B. Green Zebra (green striped on a slightly yellowish background) or Zebrino (dark green on a black-brown or dark red background). This is supposed to be because these tomatoes ripen from the inside out and not, as is known from the red tomatoes, from the outside in. These black-brown to green tomatoes, allegedly bred from a tomato variety from the Galápagos Islands , should not contain more solanine than the red tomatoes.

The coupling of gas chromatography with mass spectrometry can be used to examine the aromatic substances in tomatoes .

storage

The fruits are best stored at 13 to 18 ° C and a relative humidity of 80 to 95 percent. In contrast to leafy vegetables, tomatoes can be kept for up to 14 days. It hardly loses any important ingredients. Many consumers, but also greengrocers and retail chains, mistakenly store tomatoes in cold stores or in the refrigerator, where they clearly lose their taste, texture and shelf life. One reason for this is that at temperatures below 12 ° C, flavorings such as isovaleraldehyde , 2-methyl-1-butanol or 3-methyl-1-butanol are no longer formed.

If the tomato is kept for too long, the skin of the tomato becomes thinner and wrinkled, the flesh collapses a little, and the whole fruit looks a bit mushy and feels very soft. Nevertheless, the tomato is still edible and not bad.

If possible, tomatoes should always be stored separately from other fruits and vegetables. During storage, they excrete ethene , which accelerates the metabolism of neighboring fruits or vegetables, so that they ripen more quickly and consequently also spoil more quickly.

Consumption and origin

On average, every German eats around 22 kg of tomatoes per year. Almost half of this is consumed as fresh tomatoes. Only 6 percent of the tomatoes marketed in Germany are also produced domestically. In total, around 17 million tons of tomatoes are grown annually in Europe on an area of 494,993 hectares .

Tomato varieties

Agro, Amati, Belriccio, Bolzano, Corazon, Corianne, Culina, Cupido, Dasher, Datteltomate, Devotion, Del-Icia, Diplom, Dolce Vita, Exxtasy, Fantasio, Fourstar, Gardenser's delight (stick tomato), toothed tomato, Green Zebra (stick tomato) , Kalimba, Kumato, Laternchen (stick tomato), Luigi, Luxor, Maestria, Maranello, Myrto, Ochsenherz / Coeur de Boeuf, Phantasia, Philovita, Picolino, Pixel, Primabell, Quadro, Ravello, Siberian Finger, Sparta, Sportivo, Suso, Sunviva , Sweet Million, Timos, Timotion, Tomosa, Trilly, Tumbling Tom Red (hanging tomato), Vilma, Vanessa, Virginia, Vision, Vitella, Zebrino, Vladivostokskij (Siberia), Gelber von Thun und Würmli (Switzerland), Gelber Moneymaker (England) , Oaxacan Jewel and Miel de Mexique (Mexico), Black Sea Man and Malakhitovaya Shakatulka (Russia), White Rabbit (USA), Dix Doigts de Naples (Italy).

Others

- In Unicode, the tomato has its own character in the block Various pictographic symbols at position U + 1F345.

- In Germany the tomato was voted Vegetable of the Year 2001 by the Association for the Preservation of Crop Diversity eV (VEN).

- For a long time it was customary to sell tomatoes of a lower, watery quality than soup tomatoes .

literature

- Adelheid Coirazza: Tomatoes: 200 recommended varieties from around the world. Formosa-Verlag, Witten 2009, ISBN 978-3-934733-06-0 .

- Adelheid Coirazza: Tomatoes 2: 208 Historic tomatoes and wild varieties. Formosa-Verlag, Witten 2014, ISBN 978-3-934733-12-1 .

- Annemieke Hendriks: Tomatoes. The true identity of our fresh vegetables. be.bra Verlag , Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-89809-139-8 .

- John Paul Jones: Compendium of Tomato Diseases. American Phytopathological Society, 1991, ISBN 0-89054-120-5 .

- Reinhard Lieberei, Christoph Reissdorf, Wolfgang Franke (founder): Crop science. 7th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag , Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-13-530407-6 .

- Andres Sprecher and Markus Dlouhy (photographer): The big book of tomatoes. Fona Verlag, Lenzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-03780-416-2 .

- Erich Stekovics , Julia Kospach: Atlas of the exquisite Paradeiser . Photographs by Peter Angerer. Löwenzahn Verlag, Innsbruck 2011, ISBN 978-3-7066-2480-0 .

- Ute Studer and Martin Studer (photographs): Tomato lust. The Tomato Pioneer Secrets - Tips for Growing Really Good Tomatoes. Haupt Verlag, Bern 2019, ISBN 978-3-258-08102-1 , review: Awarded the German Garden Book Prize , 2nd place as best garden or plant portrait .

- Christoph Wonneberge, Fritz Keller: Vegetable growing. Verlag Eugen Ulmer , Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8001-3985-5 .

- David Gentilcore: Pomodoro! A History of the Tomato in Italy. Columbia University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-231-52550-3 .

- Wolfgang Seidel: The world history of plants. Eichborn Verlag, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-8479-0512-7 .

- Udelgard Körber-Grohne: Useful Plants in Germany. Cultural history and biology. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-534-13827-9 .

- Stefanie Jacomet: The history of the tomato. University of Basel, Basel 2011, available at: https://duw.unibas.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/duw/IPNA/PDF_s/PDF_s_in_use/2011_Jacomet_GeschichteTomate.pdf

- Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner: History, Origin and Early Cultivation of Tomato (Solanaceae). In: Maharaj K. Razdan and Autar K. Mattoo (Eds.) Genetic Improvement of Solanaceous Crops, Volume 2: Tomato. Enfield (NH), Jersey & Plymouth 2007, pp. 1-24, ISBN 978-1-57808-179-0 .

- Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner, Knapp Sandra: Taxonomy of Wild Tomatoes and their Relatives (Solanum sect. Lycopersicoides, sect. Juglandifolia, sect. Lycopersicon; Solanaceae). In: Systematic Botanic Monographs 84 2008, ISBN 978-0-912861-84-5 .

Movies

- What makes real tomato taste? Knowledge broadcast, Germany, France, 2017, 26:11 Min, written and directed. Bettina Oberhauser, Barbara Petermann, Claudia Lewerenz, Scott Deberry, production: arte , Row: Xenius , first broadcast: June 21, 2017 in arte, Summary of ARD .

-

Triumph of the tomato. Documentary with scenic documentation, Austria, 2014, 45:30 min., Script and director: Maria Magdalena Koller , production: MR-Film, arte , ORF , CCTV 9 , series: Universum , first broadcast: April 29, 2014 on ORF 2 , Synopsis from ORF, ( memento from November 30, 2014 in the web archive archive.today ), film images , etc. a. with Erich Stekovics, Irina Zacharias, Joe Cocker .

This documentary was awarded the Silver Dolphin in the category “Nature, Environment and Ecology” at the Cannes Corporate Media & TV Awards in 2014. - Red Illusions - The Hunt for the Honest Tomato. Documentary, Germany, 2014, 42:15 min., Script and director: Ralph Quinke, production: Spiegel TV , series: Wissen, first broadcast: March 6, 2014 on pay TV in the cable network, table of contents and online video from Spiegel TV, with Christian Lohse .

- Sarah Wiener's first choice. Tomatoes from Vesuvius. Documentary, Germany, 2013, 43:20 min., Book: Volker Heise , director: David Nawrath , production: zero one film, arte , ORF , series: Sarah Wieners first choice, first broadcast: June 30, 2013 on ORF 2 , summary and recipes from arte, ( Memento from October 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- Tomatoes to turn red. The variety keepers. How ProSpecieRara preserves tomato varieties in Switzerland. Documentary, Switzerland, 2009, 35:50 min., Script and direction: Ursula Bischof Scherer, production: NZZ Format, first broadcast: June 7, 2009 on VOX , table of contents with preview of NZZ Format.

- Attack of the killer tomatoes . Feature film, USA, 1978, parody of the science fiction and horror film genre and is considered one of the worst films of all time.

Web links

- tomatoes-atlas.de

- tomato needle.de

- giftpflanze.com: tomato

- pflanzenforschung.de: "Ripe clock" regulates the number of inflorescences and the amount of fruit in tomatoes

- stern.de , October 9, 2012: Tomatoes can reduce the risk of stroke

- srf.ch , August 31, 2014: Swiss tomatoes that have never seen the earth (" Hors-Sol Tomatoes" = "Earthless" tomatoes)

- Iris E. Peralta, Sandra Knapp, David M. Spooner: Solanum lycopersicum . In: Solanaceae Source. accessed on January 22, 2018

Individual evidence

- Most of the information in this article has been taken from the sources given under literature; the following sources are also cited.

- ↑ tomato apple. In: Duden

- ↑ Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner, Sandra Knapp: Taxonomy of Wild Tomatoes and their Relatives (Solanum sect. Lycopersicoides, sect. Juglandifolia, sect. Lycopersicon; Solanaceae) . (= Systematic Botany Monographs. Volume 84). The American Society of Plant Taxonomists, 2008, ISBN 978-0-912861-84-5 .

- ↑ Udelgard Körber-Gröhne: Useful plants in Germany. Cultural history and biology . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-534-13827-9 , pp. 315 .

- ↑ Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner: History, Origin and Early Cultivation of Tomato (Solanaceae) . In: Maharaj K. Razdan and Autar K. Mattoo (eds.): Genetic Improvement of Solanaceous Crops . tape 2 . Science, Enfield, Jersey & Plymouth 2007, ISBN 978-1-57808-179-0 , pp. 14-17 .

- ↑ Etimología de Tomato. In: Diccionario Etimológico español en linea. dechile.net, July 2, 2017, accessed July 3, 2017 (Spanish).

- ↑ The origin of the tomatoes. In: European Food Information Center. August 3, 2001.

- ↑ Gentilcore, David .: Pomodoro! : a history of the tomato in Italy . Columbia University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-231-52550-3 , pp. 3 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Seidel: World history of plants . Eichborn Verlag, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-8479-0512-7 , pp. 231 .

- ↑ Stefanie Jacomet: The history of the tomato. (PDF) University of Basel, 2011, p. 7 , accessed on January 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner: History, Origin and Early Cultivation of Tomato (Solanaceae) . In: Maharaj K. Razdan and Autar K. Mattoo (eds.): Genetic Improvement of Solanaceous Crops . tape 2 . Science, Enfield, Jersey, Plymouth 2007, ISBN 978-1-57808-179-0 , pp. 17 .

- ↑ Gentilcore, David .: Pomodoro! : a history of the tomato in Italy . Columbia University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-231-52550-3 , pp. 3 .

- ↑ Gentilcore, David .: Pomodoro! : a history of the tomato in Italy . Columbia University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-231-52550-3 , pp. 1 .

- ↑ Stefanie Jacomet: The history of the tomato. (PDF) University of Basel, 2011, p. 8 , accessed on January 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner: History, Origin and Early Cultivation of Tomato (Solanaceae). In: Maharaj K. Razdan and Autar K. Mattoo (Eds.): Enetic Improvement of Solanaceous Crops . tape 2 . Science, Enfield, Jersey & Plymouth 2007, ISBN 978-1-57808-179-0 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Stefanie Jacomet: The history of the tomato. (PDF) University of Basel, 2011, p. 9 , accessed on January 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner: History, Origin and Early Cultivation of Tomato (Solanaceae) . In: Maharaj K. Razdan and Autar K. Mattoo (eds.): Genetic Improvement of Solanaceous Crops . tape 2 . Science, Enfield, Jersey & Plymouth 2007, ISBN 978-1-57808-179-0 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Stefanie Jacomet: The history of the tomato. (PDF) University of Basel, 2011, p. 8 , accessed on January 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Iris E. Peralta, David M. Spooner: History, Origin and Early Cultivation of Tomato (Solanaceae) . In: Maharaj K. Razdan and Autar K. Mattoo (eds.): Genetic Improvement of Solanaceous Crops . Enfield, Jersey & Plymouth 2007, ISBN 978-1-57808-179-0 , pp. 17 .

- ↑ Stefanie Jacomet: The history of the tomato. (PDF) University of Basel, 2011, p. 9 , accessed on January 13, 2020 .

- ↑ An excerpt from the history of the Mohren Pharmacy # 1543. In: Mohren Pharmacy. (Torgau).

- ↑ Edith Schowalter: Light into the thicket. More plant stories from home. In: BR , May 3, 2015, picture 97 [!]

- ↑ Barbara Wittor: pharmacy, botany, agriculture in the 16th century. In: DAZ , 2008, No. 47, p. 96, November 20, 2008.

- ↑ a b Iris E. Peralta, Sandra Knapp, David M. Spooner: Nomenclature for wild and cultivated tomatoes. In: Report of the Tomato Genetics Cooperative. Volume 56, September 2006, pp. 6-12.

- ^ The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation: Solanaceae . (online) . Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ↑ Karl Schumann, Ernst Gilg: Das Pflanzenreich, Hausschatz des Wissens . Verlag von J. Neumann, Neudamm, around 1900, p. 772. ( Online Scan )

- ↑ a b tomato as an entry in the transGEN database. In: transgen.de. Forum Bio- und Gentechnologie eV, accessed on January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Genetically modified tomatoes: 45 days crisp and fresh. In: zeit.de . February 2, 2010, accessed January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ First open source vegetable in Germany A tomato, free for everyone. In: swr.de . April 26, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Tomato Disorders - A Guide to the Identification of Common Problems , ( Memento March 3, 2009 on the Internet Archive ), Aggie Horticulture, Texas A&M University .

- ↑ a b c d e Crops> Tomatoes. In: Official FAO production statistics for 2018. fao.org, accessed on March 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Why a lot of tomatoes don't taste like anything. In: ORF . October 6, 2012.

- ↑ EP Heuvelink: Tomatoes - Fruit cracking and russeting . CABI, 2005, ISBN 0-85199-396-6 , pp. 193-195.

- ↑ Michael Böddeker: Sea water with added value. In: Wissenschaft.de . April 26, 2008.

- ↑ Cristina Sgherri, Zuzana Kadlecov, Alberto Pardossi, Flavia Navari-Izzo, Riccardo Izzo: Irrigation with Diluted Seawater Improves the Nutritional Value of Cherry Tomatoes. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56, 2008, pp. 3391-3397, doi: 10.1021 / jf0733012 .

- ↑ Michael Miersch : Organic warriors against crop pests. In: The world . June 5, 2009.

- ^ Dave Goulson : A sting in the tale. Random House, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-224-09689-8 , item 2607.

- ^ Dave Goulson: A sting in the tale. Random House, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-224-09689-8 , item 2602.

- ^ Dave Goulson: A sting in the tale. Random House, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-224-09689-8 , item 2596.

- ↑ a b Dave Goulson: A sting in the Tale. Random House, London 2013, position 2613.

- ↑ a b Dave Goulson: A sting in the Tale. Random House, London 2013, position 2619.

- ↑ a b Dave Goulson: A sting in the Tale. Random House, London 2013, position 2642.

- ^ Regula Schmid-Hempel et al: The invasion of southern South America by imported bumblebees and associated parasites . In: Journal of Animal Ecology . tape 83 , no. 4 , 2014, p. 823-837 , doi : 10.1111 / 1365-2656.12185 , PMID 24256429 .

- ↑ Jacques Lanore: Tables de composition des aliments. Institut scientifique d'hygiène alimentaire, éditions, 1985, ISBN 2-86268-055-9 .

- ↑ Carl Heinz Brieskorn, Heinrich Reinartz: To the composition of the tomato peel. In: Journal of Food Study and Research . 133, 1967, pp. 137-141, doi: 10.1007 / BF01460615 .

- ↑ E. Giovannuci, EB Rimm, Y. Liu, MJ Stampfer, WC Willett: A Prospective Study of Tomato Products, Lycopene and Prostate Cancer Risk. In: J. National Cancer Institute. 94, 2002, pp. 391-398.

- ↑ Werner Baltes: Food chemistry. 5th edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66525-0 , p. 232.

- ↑ Kochmann, Hans-Jürgen: Gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric analysis of volatile compounds of tomatoes , University thesis TU Berlin (West) 1969, Faculty of general engineering, dissertation from December 18, 1969 [1]

- ↑ Bo Zhang, Denise M. Tieman, Chen Jiao, Yimin Xu, Kunsong Chen, Zhangjun Fe, James J. Giovannoni, Harry J. Klee: Chilling-induced tomato flavor loss is associated with altered volatile synthesis and transient changes in DNA methylation. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 113, 2016, pp. 12580–12585, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1613910113 .

- ↑ Vegetable of the year 2001: The tomato. In: Association for the preservation of crop diversity e. V. accessed on July 3, 2017.

- ^ Tomato , in: Römpp Lexikon Lebensmittelchemie , 2nd edition, Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-13-143462-3 , pp. 1178f .; limited preview in Google Book search.

- ↑ Sigrun Hannemann: Tomato lust by Ute and Martin Studer. In: hortus-netzwerk.de , March 19, 2019.

- ↑ Prize winners 2019: 2nd place “Best garden or plant portrait”. In: gartenbuchpreis.de , accessed on May 8, 2019.

- ↑ A syllable dolphin for the tomatoes! ( Memento of March 2, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: stekovics.at , October 2, 2014, original page .

- ↑ Jürgen Ritter: Attack of the killer tomatoes. Vegetables are not healthy after all. In: SpOn September 2, 2008.