cocktail

A cocktail [ ˈkɔkteɪl , English ˈkɒkteɪl ] is an alcoholic mixed drink . Typically, cocktails consist of two or more ingredients, including at least one spirit . They are freshly prepared individually with ice in the cocktail shaker , mixing glass or directly in the cocktail glass, arranged in a suitable glass and served and drunk immediately. Usually every cocktail recipe has a memorable name. Some cocktails are internationally known and are mixed by bartenders worldwide.

Change of meaning

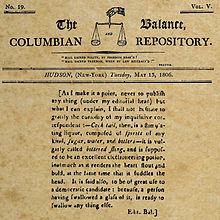

The word "cocktail" originated around 1800 in the Anglo-Saxon language area and originally only referred to a very specific type of mixed drinks common at the time. The first written source defined "cock tail" in 1806 as a "stimulating drink made from all kinds of spirits, sugar, water and bitters ". It was common practice to dilute the spirits, which were often very rough at the time and which came out of the barrel with a high percentage of percentage, with water and sweetened with sugar, and these drinks were called slings . A “cocktail” was therefore nothing more than a variant of a sling additionally flavored with herbal bitters, which roughly corresponds to today's Old Fashioned . It was also common to have cocktails in the morning. Soon other variations emerged, which were also called “cocktail”, and the word became a generic term, but remained just one of many drink groups in the 19th century. In the first half of the 20th century, “cocktail” increasingly became the generic term for almost all alcoholic short drinks . Especially in professional circles, the word is still understood today in this narrow sense, i.e. as a designation for mostly strongly alcoholic, cold-mixed short drinks served without ice in a stemmed glass (typically a cocktail bowl ) and as a demarcation especially to long drinks and larger, in Mixed drinks served in tumblers or fancy glasses. In general usage, however, another change in meaning took place in the second half of the 20th century: “Cocktail” gradually became a collective term for almost every alcoholic mixed drink and sometimes also for non-alcoholic mixes. In this article and generally in the German-language Wikipedia, the word “cocktail” is mainly used in this broad sense.

Word origin

How the word “cocktail” came about and why it became the name for alcoholic mixed drinks has not been clarified and is therefore the subject of many theories and anecdotes. What is certain is that the name came up around 1800 and first spread in the English- speaking world, especially on the east coast of the United States . But even the assumption that the word originated from the amalgamation of the English words cock (cock) and tail (tail), as some dictionaries suspect, is controversial, although the hyphenated spelling in some very early sources suggests this.

Early use

One of the earliest printed evidence of the use of “cocktail” in a drink comes from a London newspaper from 1798. The Morning Post and Gazetteer reported on a happy pub owner who had canceled his guests' debts after winning the lottery. A week later, the newspaper revealed in a satirical statement the allegedly imposed collieries by individual politicians, including

"Mr. Pitt,

two petit verses of 'L'huile de Venus' 0 1 0

Ditto, one of 'perfeit amour' 0 0 7

Ditto, 'cock-tail' (vulgarly called ginger) 0 0 3/4 "

"Mr. Pitt ”(which probably meant the then Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger ) allegedly consumed two glasses (French: verres )“ Venus Oil ”, a glass of Parfait Amour (German:“ perfect love ”) and a glass of“ cock-tail ”. What this "cock-tail" consisted of is not mentioned, but it is also known as "ginger" (ginger). The drinks could have been allusions to Pitt's private life, as the fact that he was unmarried was often the subject of lewd jokes and speculations about his alleged homosexuality; In addition, there is a reference to France through the French liqueurs, with which Great Britain was at war at the time. “Ginger” not only referred to a brownish-red color, the ginger tuber was also considered aphrodisiac and gingery was used as an adjective in the sense of “hot-blooded” or “disgruntled”. In later sources, too, the stimulating effect of a morning cocktail is repeatedly pointed out, regardless of whether the recipes actually contained ginger or not. According to the cocktail historians Brown and Miller, the mention in connection with French liqueurs could also indicate a French origin of the word “cocktail”. There actually was a French drink called “coquetel”; Dietrich Bock speaks of a wine-based mixed drink from the Bordeaux area and he also points out that the Americans were supported by a French expeditionary army during the War of Independence (1755–1781), which could explain the later adoption of the word into American. The French word “coqueter” (to flirt) also sounds similar to “cocktail”, but there is no evidence of a corresponding use of language at the time.

In any case, in North America “cocktail” appeared as a name for a drink for the first time in 1803. In a humorous newspaper essay, the narrator, a young do-it-all, describes the course of a hungover morning: “ 11 [o'clock]. Drank a glass of cocktail — excellent for the head… […] Call'd at the Doct's… —drank another glass of cocktail. "(German:" 11 [o'clock]. Drank a glass of cocktail - excellent for the head ... [...] called the doctor ... - drank another glass of cocktail. ") Whatever this drink was; It should be kept in mind that in the first half of the 19th century cocktails were already consumed in the mornings due to their restorative effect, especially by vicious day thieves - the historian David Wondrich calls them “a loungy, sporty, dissolute set”; Ted Haigh speaks of gamblers, crooks and pimps.

The first indication of what a cocktail actually consisted of came from a New York newspaper three years later in May 1806 . In a mocking report on an election campaign event, one can read the alcoholic effort with which a politician kept his potential electorate happy. Be Enumerated among other 720 Rum - grog , 411 glasses Kräuterbitter and "cock-tails" for $ 25. Incidentally, in vain, the candidate lost the election - what is interesting, however, is a letter to the editor that the editorial team then received. In it a reader asked about this new, unknown drink called "cock-tail". Should the name indicate the effect of the potion on certain parts of the body? Would he have turned the heads of those present in such a way that they were now lying in the abdomen (“where their tails should be”)? The editor's answer will appear in the next issue:

"Cock-tail, then, is a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters - it is vulgarly called a bittered sling, and is supposed to be an excellent electioneering potion inasmuch as it renders the heart stout and bold, at the same time that it fuddles the head. [...] a person having swallowed a glass of it, is ready to swallow any thing else. "

“A cock-tail is a stimulating drink made from all kinds of spirits, sugar, water and bitters , is also commonly known as“ bittered sling ”and is said to be an excellent campaign drink that makes you bold and daring and at the same time clouds your head. [...] Anyone who has had a glass of it is ready to swallow everything else too. "

Sling was a common mixed drink at that time and referred to a spirit diluted with water and sweetened with sugar. The brandies of that time were still very rough and could hardly be enjoyed undiluted from the barrel. The “new” thing about the cocktail was that the well-known sling was also seasoned with cocktail bitters . These bitter spirits made from herbs and spices, which were often made by pharmacists, were widely used as remedies at the time and, like alcohol in general, were used to cure all kinds of ailments and to increase general well-being.

Cocktails as a morning drink

From then on, the word “cocktail” kept appearing, even if only sporadically at first. Although the often cited early mention in Washington Irving's Knickerbocker's History of New York from 1809 is not documented (“Cocktail” only appears in later reprints), a newspaper in New York already praised the “superior virtues of gin-sling and cock” in 1813 -tail ”(“ the superior virtues of gin sling and cocktail ”) and in 1816 an author in the New York Courier described how he spent his days with“ a cocktail or two every morning before breakfast ”(“ a cocktail or two every morning before breakfast ”) and ends the day with two or three Brandy Tods (Brandy Toddies) without missing out on one or two cocktails before dinner. In an advertisement from 1818, the cocktail was defined as bitter sling in Massachusetts, as in 1806, and also in Worcester in 1820. David Wondrich therefore locates the roots of the cocktail spread in the Hudson Valley on the east coast of the United States, i.e. the area around Boston, Albany and New York.

Originally, cocktails were quick, invigorating, strongly alcoholic drinks that were consumed early in the morning. William Grimes quotes a contemporary witness from 1822, according to which a simple "Kentucky breakfast" consisted of "three cocktails and a chaw of terbacker" ("three cocktails and a portion of chewing tobacco"). In 1869, William Terrington defined cocktails in London as “mixtures that are preferred by early birds to strengthen their virility”. Some recipes followed, some of which even correspond to the definition from 1806, i.e. only alongside a spirit Contained sugar, water or ice as well as bitters or other spice essences; but sometimes also other ingredients such as ginger syrup or curacao . Up until the end of the 19th century, morning cocktails weren't unusual in the United States either: "If you like a cocktail in the morning, come here and you'll get one that is made as a cocktail should be made" (German: "If you want a cocktail in the morning, come to us and you will get it the way a cocktail should be"), so the text suggestion for an advertisement from a guide for liquor dealers from 1899. Associated until the 1830s there is also a certain viciousness with cocktails:

"If you drank a cocktail, you were a little dangerous, and therein lay the seeds of its fame. It was the bad-boy syndrome. "

“When you've had a cocktail, you seem a little dangerous, and that's why it's so successful. It's the bad boy image. "

Poultry stories

Since cock and tail mean “rooster” and “tail” in English, the word creation was later often associated with a colorful rooster tail (the “rooster's tail” or “cock tail”). William T. Boothby used a corresponding cover picture for his mix book American Bar-Tender as early as 1891 . The logo of the German Barkeeper Union, which was registered as a trademark in 1965 , also featured a colorfully feathered rooster on a cocktail glass . Various theories are used to derive this. The bright colors of the drinks supposedly reminded of a cock's tail. This may apply to colorful juice, syrup and liqueur creations of the 20th century, the mixed drinks called “cocktails” around 1800, as shown above, were by no means colorful, and pousse cafés made from colored liqueurs came into fashion much later. Ted Haigh suspects that the cocktail got its name because it was consumed in the morning and looked like the wake-up call of a rooster greeting the first light of day.

According to another story, the name came about during cockfights. Allegedly, the owner of the winning tap had the right to tear out a feather from the losing tap, which he stuck to his drink. Then you toasted the cock's tail. However, there is no historical evidence for this version, nor for the assumption that the first cocktails owed their name to a ceramic tap from which they were drawn, or were even called "cock ale" or "cock bread" from the taps themselves ale ”. It was bread soaked in a spicy infusion of herbs, roots and ale to strengthen their fighting strength.

In fact, "cock ale" was established around 1800 as a name for a certain type of drink and can be traced back to 1648. In Scotland, a potion of this name is said to have been prepared by placing the crushed bones of a boiled rooster with nutmeg, raisins, cloves and other spices in a canvas sack in a barrel of ale and allowing it to steep for several days. An English publication from 1869 mentions that in the 18th century, beer-based mixed drinks were particularly popular among mixed drinks ("cups"). Their recipes are all similar, but hardly worth mentioning. Among the many colloquial names for these mixtures, including “Humtpie-Dumptie”, “Clamber-clown”, “Knock-me-down” or “Stichback”, “Cock-ale” would have been included, especially towards the end of the 18th century. While the similarity of the words “cock ale” and “cocktail” suggests a connection, the fact that the former was a mixed beer drink, while the “cocktails” widespread in the United States at the beginning of the 19th century originally consisted of diluted, sweetened and with Bitters-mixed spirits were prepared.

The story of Betsy Flanagan, which is told in different variants, is particularly popular in the United States . She is said to have opened a pub in Four Corners, Elmsford or Yorktown during the American Revolution in the course of which her husband died, which was frequented by American and French soldiers. One evening she would have served the officers with poultry that had been stolen from a neighbor - supporter of the hated English. After the meal she served bracer (or punch), a popular drink at the time, and decorated the glasses with feathers. "Let's have some more cocktail" (English = let's have another cocktail) and "Vive le cocktail" (French = long live the cocktail) are said to have proclaimed the officers - this is supposed to have given rise to the name "cocktail". In fact, the anecdote goes back to the author James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851). For his 1821 story The Spy. A tale of Neutral Ground , which takes place in the revolutionary era, he invented a character named Betty Flanagan. She was a hotel landlady in Four Corners and served the first "cocktail". Whether this fictional Betty had a real role model, possibly a bar hostess named Catherine "Kitty" Hustler from Storm's Bridge (now Elmsford, New York), where Cooper temporarily lived, could never be clarified; at any rate, she later became the aforementioned Betsy of the popular anecdote.

Other derivations

The French pharmacist Antoine Amédée Peychaud, who settled in New Orleans in 1795, is often mentioned . He is said to have served mixed drinks there - including the local brandy toddy made from cognac , water, sugar and the Peychaud's Bitters that he made himself - in egg cups (French coquetier) , an early version of the Sazerac . By distorting the drinking vessel, the word cocktail was later developed from it . The proximity of the Sazerac to the bittered sling described in 1806 - both mixtures of spirit, sugar, water and bitter - would speak in favor of this theory, were it not for a time problem: Peychaud probably only produced the bitter named after him from 1830 when the name “ Cocktail “had long been popular.

Occasionally an anecdote is quoted by the bartender Harry Craddock , who published the legendary and widely known Savoy Cocktail Book in 1930 . According to this, the cocktail is said to have been named after a young beauty named "Coctel", the daughter of King Axolotl VIII of Mexico, who is said to have served a southern general a mixed drink during peace negotiations. With his remark "There is irrefutable evidence for the truth of this story, even if there is not the smallest written document about it!" Craddock suggests with a wink that it is a counter legend.

In his standard work The American Language , Henry L. Mencken postulated as an attempt to explain that in English pubs the leftovers (“tailings”) were poured out of liquor barrels at a reduced price. Since the tap on the barrel was also called "cock", drinkers would have liked to have "cocktails" made from leftovers. In fact, slings, the forerunners of the cocktail, consisted of a single barrel liquor (which was mixed with sugar and water), not several, and only a few dashes of bitter were added to the early cocktails . An article in the Baltimore Sun from 1908 with a detailed history of the origin of the cocktail - allegedly in Maryland - also goes back to Mencken, but it has since turned out to be a joke.

The historian David Wondrich, on the other hand, recalls that the tails of draft horses were often trimmed in the 18th and 19th centuries so that they would not get caught in the harness, and these horses were called "cock-tailed" because their tails resembled a cock's tail the air was standing - possibly a parallel to the stimulating effect of a cocktail enjoyed before breakfast. On the other hand, purebred horses were generally not used as work and draft animals, so that the term “cocktail” was generally established for a non-thoroughbred horse, also in racing. Although rare, this designation can be traced back to John Lawrence in 1796; and traced back to 1769 according to Dietrich Bock. According to Wondrich, it was not far from a “mixed-breed horse” to a “mixed-breed drink”. The word “cocktail” could have arisen in analogy to equestrian sport, as a name for a spirit that was not consumed pure, but diluted, sweetened and mixed with bitter .

history

Early mixed alcoholic drinks

Alcoholic mixed drinks, which today would be called "cocktails" (in a broader sense, see introduction), existed long before the word was established in the Anglo-Saxon region around 1800. Basically, its history is as old as the history of alcohol itself - its origins are lost in the distant past. The earliest finds can be assigned to the Neolithic Age . During the Neolithic Revolution , which began about 12,000 years ago, there was a transition from the nomadic way of life of hunters and gatherers to sedentarism with agriculture and livestock. In Jiaju ( China ), one of the oldest excavation sites associated with the Peiligang culture , vessels were found that had residues of fermented rice, honey and fruits and could be dated to around 7000 BC. Around the same time, cultures in the Middle East began brewing beer from barley and making wine from wild grapes. In Anyang (China), lockable bronze vessels from the time of the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties (around 1250–1000 BC) were found that contained rice and millet wine , which was made with wormwood , chrysanthemums , spruce , elemi and other plants Herbs. Even today, similar flavored wines are produced in Vietnam (“Ruou”), China (“Zieu” or “Chiew”), Korea and Japan ( Shōchū ). The ancient Greeks already introduced flavored wines ( "vinum Hippocraticum") away, from where in the 18th century in Italy, the wormwood developed (vermouth) - today one of the main cocktail ingredient.

However, only a comparatively low alcohol content could be achieved using alcoholic fermentation alone . The Mongols , however, found a way to increase it early on by repeatedly freezing donkey milk fermented with wild yeast and separating the ice. This increased the alcohol content in the remaining liquid up to 30% vol., Which made it durable for months. The same method was used by early American settlers in New England centuries later, freezing fermented cider during the cold winter months to create applejack with a higher alcohol content. This was not healthy, however, because undesirable and harmful by-products of fermentation were also concentrated in the drink. Today Applejack is also made by distillation .

The discovery of distillation

A significant milestone in the history of mixed alcoholic beverages was the discovery of distillation : it was recognized that some liquids could be "separated" into different components when heated by collecting their vapors and allowing them to condense . Around 9,000 years ago, blossoms and other parts of plants were heated in China and the vapors captured to make perfume. The oldest written tradition for the production of drinking alcohol can be found in the Vedas . In these collections of texts in Sanskrit there is talk of a ritually used drink called "Somarasa", which was consumed at religious festivals in honor of the deity Indra . In the 2000 year old constitutional law textbook Arthashastra , several spirits are mentioned, including Asava , made from grain, fruits, roots, bark, flowers and sugar cane. In a medical textbook, probably around 350 AD, the Susruta Samhita , which goes back to the doctor Sushruta , the word khola is used for the first time as a generic term for these drinks, which was later introduced into European languages via Arabic ("alcohol") ) found. A text by Aristotle , in which he describes the extraction of fresh water from salt water, suggests that the technique of distillation was already known in ancient Greece . However, the transfer of knowledge from the East temporarily ended with the demise of the Alexandria Library , from whose holdings only a few works in European monasteries survived.

The next milestone is considered to be the alambic , a still of the Arab alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyān (Latinized Geber, Jeber, probably 8th century), with which the alcohol could be concentrated much higher than with the methods known from India and China. A little later, al-Kindī is said to have distilled highly concentrated ethanol with the Alambic . Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi (Rasis) produced brandy and confirmed the suitability of alcohol as a preservative and carrier for medicinal substances. With the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula by the Moors and the translation of Arabic texts by Robert von Chester , the knowledge of distillation reached Spain around 1140. Inspired by this, Arnaldus de Villanova coined the word eau de vie (“water of life”) for distilled drinking alcohol around 1250, and Ramon Llull called the substance “alcohol” around the same time . Distilleries spread across Europe between the 13th and 15th centuries. In 1476 Michael Puff von Schrick described 82 herbal liqueurs in his useful little book about the burned-out waters ; 38 revised editions appeared up to 1601. Influential was Jerome Brunschwigs book Liber de Arte de distillandi Compositis - The Büch of art were distill timeouts . Numerous distilleries for brandewijn made from malted grain were built in Schiedam and Amsterdam . In Poland, too, a grain-based aqua vitae was made in the 15th century; the name "Vodka" has been handed down since the 16th century. Also in the 16th century, the production of spirits began in the New World , where the sugar cane liquor aguardiente de cana (today Cachaça ), rum and pisco were distilled . In 1675 rum became an official part of the daily rations in the Royal Navy , since 1730 a sailor has received almost 300 ml of 70 to 85% rum every day, which corresponds to about 570 ml in today's drinking strength. So over the centuries, alcohol had changed from an alchemist's elixir to a daily food and beverage that was even considered healthy and vitalizing in medicine.

Alcoholic mixed drinks before 1800

Alcoholic mixed drinks were also known in North America long before the name “cocktail” was developed. After the Swedish cleric Israel Acrelius had toured the British colonies in North America between 1749 and 1756, he reported 45 different mixed drinks , including combinations of lemon juice, milk and sweetened vinegar. And an Englishman who toured the United States between 1793 and 1806 noted:

"The first craving of an American in the morning, is for ardent spirits, mixed with sugar, mint, or some other hot herb, and which are called slings."

"The first thing Americans want in the morning are liquor drinks that are mixed with sugar, mint, or other strong herbs and are called slings."

The time until 1860

While the morning consumption of "cocktails" was initially considered indecent, the drink was able to penetrate more and more established circles of society by around 1830. Cocktails were now also consumed when hunting foxes or playing polo and lost their originally offensive image. Variants of the drink originally defined as "bittered sling" emerged and their consumption shifted to socially less controversial times of the day. At the same time, the bitters, often produced by pharmacists, were increasingly criticized as “snake oil” (snake oil) and “sham medicine” (quackery). In a cocktail, however, the elixirs could be what they are still today: a luxury item.

Several factors contributed to the popularization of cocktails and other mixed drinks in the United States during the first half of the 19th century:

On the one hand, there have been some significant innovations in distillation processes in these decades . With the column still developed by Robert Stein in 1826 and improved by the Irishman Aeneas Coffey in 1831, for example, it was possible to produce large quantities of whiskey very inexpensively in a continuous distillation process. In addition, the quality of spirits improved in general; they became increasingly palatable in the course of the 19th century, without masking their sharp taste with water, sugar and spices.

Immigration from Europe also plays a role. With her, not only technical knowledge came into the country, but also many people who wanted to build a new life for themselves in the “New World”. In the newly founded localities, saloons developed where alcohol was first served behind a barrier and later on a counter - the actual bar. They were a social meeting place, a place to make new contacts and of course a place to drink too. At the same time, the immigrants brought their drinking habits and preferences with them from Europe, so that numerous new mixed drinks were to be created in America. The import of vermouth from Italy to the United States, for example, has been documented since the 1840s - this ingredient was later the basis for legendary cocktails such as the Manhattan or the Martini .

The availability of ice - today an indispensable ingredient in the preparation of almost all alcoholic mixed drinks - has also improved in these years. Frederic Tudor built a large ice cream warehouse in New Orleans in 1820 and exported North American natural ice not only to the Caribbean , but also to Rio de Janeiro and Calcutta . The cooling with ice improved the taste of many mixed drinks enormously.

The golden age of cocktails

An important milestone in cocktail history is a book: In 1862 Jerry Thomas published his legendary recipe collection How to Mix Drinks, or the Bon Vivant's Companion . Before that, Thomas had been a bartender across the United States for several years . In his book he had collected and categorized numerous mix recipes. For the first time a kind of “official canon” of North American mixed drinks was created. The book spread very quickly in several editions and numerous, partly unauthorized reprints, even as far as Europe. By the way, in Jerry Thomas' time the cocktail was still an everyday drink, it was even available ready-made in bottles and you could take it with you on a trip or to a picnic:

"The cocktail is a modern invention and is generally used on fishing and other sporting parties, although some patients insist that it is good in the morning as a tonic."

"The cocktail is a modern invention and is commonly taken to fishing and other sporting events, although some patients insist that a morning cocktail is a good tonic."

The phase up to the end of the 19th century is also referred to by many authors as the "golden age of cocktails". Unlike in Europe, it was customary in North America at that time to separate food and drink in the catering trade - there were restaurants on the one hand, and saloons and bars on the other, which mainly served alcohol and at most offered small bites as free additions. After the American Civil War (1861–1865) the development of the " Wild West " continued. More and more new cities with their bars and saloons emerged, for example along the railway lines that had connected the western states since 1869, such as California , which was incorporated in 1850, with those in the east.

During this time, the cocktail became the generic term for a large number of mixed drinks. At the same time, the profession of professionalized bartender and still valid techniques in preparing established themselves. The first cocktail shakers also appeared and were even patented. Many classics that are still known today, such as the Martini or its forerunners, the Martinez , the Old Fashioned and the Manhattan were created in those years.

With some delay, the cocktail wave also reached continental Europe, where the new mixed drinks were initially referred to as "American mixed drinks". The first definition of a cocktail in German can be found in a cookery dictionary from 1886:

"Cocktail. A very popular drink in America, a kind of cold grog made up of brandy, bitter liqueur, ice and sugar; Sometimes peppermint liqueur is used instead of bitters. You have brandy cocktail, whiskey cocktail, gin cocktail, etc. depending on whether you take cognac or other brandy with a glass of this drink. The procedure is as follows: Put in a glass about two to three tablespoons of clear-boiled sugar syrup, three tablespoons of bitter liqueur, good bitter oranges, a wine glass of cognac, gin, or whiskey, and a piece of thinly peeled lemon peel, fill the glass into one Third with crushed ice, pour the drink back and forth a few times, since then and pour it into a large wine glass. "

Literature and web links on the history of cocktails

- From the origin of the cocktail Article series to cocktail history

- Dietrich Bock: Exquisite cocktails for private guests. Self-published, Erkrath-Hochdahl 1997, ISBN 3-00-001901-4 . First German-language presentation of the history of cocktails, the American drinking culture of the 19th century and its spread in Europe, extensively researched using original sources.

- Stefan Gabányi: German Bar Culture , in: Mixologist. The Journal of the European Cocktail, Vol. 3 . Mixellany, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-907434-00-6 , pp. 121-126 (English). Brief overview of the development of mixed drinks in Germany.

- William Grimes: Straight up or on the Rocks. The Story of the American Cocktail. North Point Press, New York 2001, ISBN 0-86547-601-2 (English).

- Anistatia Miller, Jared Brown: A Tour de Force . In: Helmut Adam , Jens Hasenbein, Bastian Heuser: Cocktailian. The bar's manual . Tre Torri, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-941641-41-9 , pp. 19-41. Timeline for the development of mixed drinks.

- Anistatia Miller, Jared Brown: Spirituous Journey. A History of Drink. Volume 1: Book One: From the Birth of Spirits to the Birth of the Cocktail . Mixellany, London 2009, ISBN 978-0-9760937-9-4 ; Volume 2: Book Two: From Publicans to Master Mixologists . Mixellany, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-907434-06-8 (English). Detailed history of the production of spirits and mixed drinks.

- David Wondrich: Imbibe! From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash, A Salute in Stories and Drinks to "Professor" Jerry Thomas, Pioneer of the American Bar. Perigee (Penguin Group), New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-399-53287-0 (English). Comprehensive presentation of the development of bar culture in the United States in the 19th century using historical cocktail recipes.

Classification

Attempts have always been made to divide alcoholic mixed drinks into groups: Jerry Thomas already sorted the recipes in his handbook for bartenders from 1862 - the earliest of its kind - into different categories and defined punch; Egg nogg; Juleps; The smash; The Cobbler; The Cocktail and Crusta; Mulls and sangarees; Toddies and slings; Fixes and sours; Flip, Negus and Shrub ; He summarized non-alcoholic drinks as Temperance Drinks . But despite the many groups, Thomas already knew many drinks back then that could not be clearly assigned, so that he listed over 50 recipes as fancy drinks (such as "fantasy drinks ", from English fancy = unusual, original) and two more dozen as miscellaneous Drinks ("various beverages"). In the 19th century, “cocktail” was only the name of one of many subgroups of mixed alcoholic beverages. However, the category increasingly took up more space - in the 1887 edition of the book, “Cocktails” already represented the first-mentioned drink group and the number of recipes had doubled compared to 1862.

Since then, cocktails have been summarized and classified according to very different criteria on bar menus and in the literature. However, it is particularly difficult to assign them to new drinks that are not clearly similar to known classics. As with Jerry Thomas, they are usually grouped together as fancy drinks . Many recipe books completely dispense with categorization and list all drinks in alphabetical order. Bar menus are mostly sorted according to basic spirits, and only a few popular categories such as aperitifs or after-dinner drinks are listed separately.

By volume: short drinks and long drinks

Very often between short drinks and long drinks distinguished. Mixed drinks that contain up to 10 cl of liquid are considered short drinks. They regularly have a high proportion of alcoholic ingredients and are mostly served "straight up", i.e. without ice, in cocktail bowls with a stick. The word cocktail is often used in this narrow sense, i.e. as a generic term for a large number of short drinks and in contrast to long drinks . Long drinks are accordingly larger mixed drinks with more than 10 cl, more likely 15–20 cl liquid, e.g. B. all highballs , collinses or drinks with juices like Campari Orange . The boundaries between short and long drinks are naturally fluid and a large number of mixed drinks cannot be clearly assigned because they do not correspond to either of the two types.

Another group of drinks, which can be determined according to size, are the shooters , shots or shorts , which usually only consist of 2 or 4 cl spirits, pure or mixed, in a shot glass and are drunk in a single pull.

According to alcohol content

When classifying according to alcohol content, non-alcoholic mixed drinks, occasionally also those with comparatively little alcohol, are differentiated from “normal” cocktails, for example on bar cards or in recipe books. As non-alcoholic drinks are under German food legislation with less than 0.5% vol. Alcohol. Conversely, very (alcohol) strong drinks are occasionally shown separately. On some bar menus, for example, there are references that allegedly only a maximum of two or three of a cocktail per evening and guest are served (for example at the Zombie ).

Historically, however, the term “cocktail” is closely related to the consumption of alcohol, in particular the use of spirits (i.e. distilled distillates, as opposed to wine and beer ). Since the first half of the 20th century, when the word began to become a generic term for a variety of mixed drinks, some non-alcoholic mixed drinks have also been referred to as cocktails. However, this always happens in connection with and as a distinction to alcoholic drinks, e.g. B. on bar cards or in mixed books. As a result, a pineapple and coconut milkshake - undoubtedly a non-alcoholic mixed drink - that is served in an ice cream parlor would hardly be called a “cocktail”, whereas a Virgin Colada made from pineapple juice, cream and cream of coconut is the non-alcoholic variant of the Piña Colada on a bar menu could well be referred to as a "non-alcoholic cocktail". Non-alcoholic drinks, which, like the Virgin Colada, have an alcoholic equivalent, are also known as mocktails . In most cases, the alcoholic ingredients are left out (in the case of the Virgin Colada the rum), liqueurs are often replaced by similar tasting syrups or fruit juices. Other examples of non-alcoholic cocktails are Safer Sex on the Beach , Ipanema ( caipirinha with ginger ale instead of cachaça ) and Pussy Foot , a mixture of pineapple, orange and grapefruit juice with grenadine that has no alcoholic equivalent.

After drinking occasion

In the 20th century in particular, it was customary to differentiate between before-dinner drinks and after-dinner drinks for short drinks . Before dinner drinks were enjoyed as an aperitif before dinner. Accordingly, they are small, appetizing, high in alcohol and mostly tart or aromatic, in any case they do not contain any filling or too sweet ingredients. The best-known example is probably the martini . In contrast, you drink after-dinner drinks after your meal. This includes dessert cocktails such as the creamy-sweet (brandy) Alexander , mixtures with liqueurs (e.g. Rusty Nail ) or herbal-spicy drinks that are intended to stimulate or refresh the digestion as a digestif , e.g. B. the brandy stinger . Occasionally, medium drinks are also used; This refers to short drinks that cannot be clearly assigned to the aforementioned groups and contain citrus juices, e.g. B. the Bronx .

A specialty are the Corpse Reviers (German, for example: "revitalized"), which are supposed to rebuild and strengthen after a long bar evening. Like hangover drinks or "hangover killers", they are often spicy, e.g. B. Bloody Mary , Prairie Oyster (with egg and ketchup, among other things) or Bull Shot (vodka, beef bouillon).

According to the prevailing taste

Short drinks are often divided into the groups dry (dry = tart), medium (medium) and sweet (= sweet), a good example are the different versions of Manhattan . In addition, descriptions such as “aromatic”, “fruity”, “fresh”, “creamy-creamy” etc. can be used for orientation on bar menus.

According to ingredients

Cocktails are very often classified according to the basic alcoholic ingredient, e.g. B. in champagne drinks, vodka drinks, gin drinks, vermouth cocktails or tropicals or tropical drinks, which are almost always based on rum, rhum or cachaça. Since the alcoholic base (with the exception of vodka) usually also predominates in terms of taste, this is also associated with a rough classification of taste.

There are also drink groups for which the use of certain non-alcoholic ingredients is characteristic. Mint Juleps can be mixed with different spirits (e.g. bourbon, rye whiskey, cognac), but they always contain mint or fresh herbs (e.g. Mint Julep), similar to smashes , also with mint, fresh herbs and / or pieces of fruit that are crushed in the shaker (e.g. whiskey smash ). Eggnogs , as the name suggests, are prepared with egg yolk and cream or milk. Drinks with cream are also known as cream cocktails (e.g. Golden Cadillac ), tropical drinks with cream of coconut form the group of coladas (e.g. Piña Colada ). Snapper contain spicy ingredients such as tomato juice or beef bouillon (e.g. Bloody Mary ), coffee drinks are prepared with coffee liqueur or coffee such as White Russian or Irish Coffee .

Occasionally, the literature also differentiates according to the number of ingredients, for example when speaking of the group of two and three parts.

After preparation or serving

Some drink groups can be separated because they are not, like most cocktails, prepared in a shaker or mixing glass over ice. This includes pousse cafés , where different and above all different colored spirits, liqueurs and syrups are layered on top of each other in the glass; Frozen drinks , in the blender are prepared (Blender) with ice so that a creamy mass similar to a sherbet is formed (Example: Frozen daiquiri ); Frappés , in which only one liqueur is regularly served over shaved ice (e.g. crème de menthe frappé ); Crustas , which are served with a broad sugar rim and a spiral made of citrus peel, hot drinks , i.e. hot drinks such as Irish coffee or grog ; Bottled cocktails , which are already mixed in bottles and ripened until they are used, as well as punches , which are typically prepared for several guests and served like a punch in a bowl (e.g. the well-known Fish House Punch ).

Molecular cocktails form a special group . In line with the molecular cuisine of the 1990s, there was also a trend a few years ago at the bar to change the texture of mixed drinks, for example complete drinks or individual components with gelling agents such as sodium alginate (E401) or agar in jellies , gels and espumas (foams) or with the help of calcium lactate (E327) to transform into "aromatic pearls" or to let them fluoresce in the dark with the help of riboflavin . Rejected in principle by many bartenders , this molecular mixology could not prevail and remained a temporary fashion. However, individual elements have remained, for example espumas made from cocktail ingredients in a cream siphon with nitrous oxide .

Another trend that has been observed since around 2010 is stored or barrel stored cocktails. The ready-mixed cocktails are either stored in closed bottles for a long time - up to several months - whereby the ingredients combine differently than in a freshly prepared drink, or they mature in a wooden barrel. Analogously to spirits, one speaks of barrel aged , a similar effect can be achieved by adding wood chips, whereby the cocktail often changes significantly within hours or days when it comes into contact with wood. Several processes take place during barrel storage: Infusion, that is, flavors from the wood (especially vanillin ) are transferred to the cocktail; Oxidation through contact with oxygen, which makes the cocktail taste “nuttier”; Finally, extraction, where the wood reacts with the acidity of the cocktail and the drink becomes softer and sweeter.

According to a typical basic structure

Many cocktails can also be divided according to a certain basic idea in the combination of ingredients, which is often already clear in the name.

Sours

One of the most important cocktail groups are the sours with the basic formula of spirits + citrus juice + source of sugar . The decisive factor here is the balance between citrus acid and sugar, those flavors that "form the invisible network of almost the entire mixed beverage cosmos" and their interaction with the basic spirit. Examples of “pure” sours are whiskey sour and daiquiri . For countless other drinks and drink groups, the basic structure of the sour is varied or expanded: Instead of sugar and spirits, a liqueur can also be combined with citrus juice. For these drinks, the author Gary "Gaz" Regan tried to establish the term International Sour ; He called liqueur sours with orange liqueur New Orleans Sours (examples: Margarita and Cosmopolitan ). A crusta, on the other hand, is a sour with liqueur and bitters , which is always served with a sugar rim and a large citrus zest on the inside of the glass, e.g. B. Brandy Crusta . An extended Sour “sprinkled” with soda water is called Fizz , z. B. Gin Fizz . The many Collinses ( Tom Collins , John Collins etc.) are sours extended with soda water, but larger than a fizz. These long drinks are always served on ice cubes and often prepared directly in the guest glass.

More cocktail groups

Further cocktail groups with a characteristic basic structure are:

- Batida , consisting of a spirit (typically Cachaça ), sugar and fresh fruit (example: Caipirinha , actually a Batida de Limao ).

- Crusta , the ingredients are similar to a sour , crustas are served with a wide sugar rim and a citrus spiral in the glass.

- French-Italian drink with vermouth or a vermouth-like wine aperitif (such as Lillet ), possibly spirit + modifier (examples: Martini , Manhattan ).

- Highball : Originally a name for spirits “lengthened” with soda water or a carbonated soft drink, traditionally served with ice in a highball glass, a medium-sized beaker. Examples: Whiskey Highball ( Whiskey and Soda or Ginger Ale), Brandy Soda , Gin Tonic , Moscow Mule . The term is used differently, however, sometimes all simple long drinks regardless of size or mixtures with a wide variety of ingredients are called highballs. Gary Regan calls highballs with orange juice as a filler Florida Highball (e.g. Harvey Wallbanger ), those with cranberry juice New England Highball (e.g. Sex on the Beach ).,

Historic cocktail groups

Other categories that were frequently used in the past have almost disappeared or only survive in the name of individual mixed drinks. Examples:

- Bishop : A bishop (German bishop) is a fruit cold bowl, the name could go back to a shape of the bowl that resembles a bishop's hat.

- Cobbler : A cobbler consists of a basic spirit (or wine), syrup and possibly liqueur, is mixed on crushed ice in a glass and usually richly decorated with fruit.

- Fix : A Fix (plural: fixes) is a Sour in principle, but is on Shaved Ice (shaved ice) served and decorated with fruit.

- Grog : While in German it usually only refers to the hot drink made from rum, water and sugar, in Anglo-Saxon the name stands for a variety of hot or cold drinks with rum, for example the trader Vic Grog from the 1960s

- Knickebein : Here a basic spirit and a liqueur are combined with egg yolk. In the classic way, the ingredients are not mixed, but layered on top of each other, with the raw egg yolk in the middle.

- Negus : A negus consists of (port) wine, water, sugar and spices and is served hot.

- Punch (German punch ), formerly a popular and frequent group of drinks with a variety of recipes, hot or cold, which, in addition to the alcoholic base, contained citrus juices, sugar and water as a common feature. Punches were often prepared for several guests in a punchbowl ( punch or bowl), but could also be mixed as a single drink. Today, for example, planter's punches with a wide variety of variants are common.

- Rickeys : A Rickey was originally a highball made from a spirit and soda water, which also contained some lime juice.

- Sangaree : This outdated English term is used to describe various mixed drinks that share port wine or sherry, see also Sangría .

- Shrub : Typical of a shrub is the use of fruit syrup, often made on the basis of vinegar.

- Sling : Originally (late 17th century) a sling consisted of a spirit, water and sugar and was often dusted with nutmeg. The original form of the cocktail was defined in 1806 as a bittered sling , i.e. a sling with bitters . The Singapore Sling , which is still popular today, goes back to this group by name, but its recipe no longer has much in common with the original slings.

- Toddy : Term for very different drinks, for example mixtures of a spirit, water, sugar and nutmeg, as hot toddy it is a hot drink similar to grog .

Systematic approaches

In 2003, Gary “Gaz” Regan attempted a systematic classification of the most famous cocktails in his book “The Joy of Mixology”. He divided them into “families”, each with a similar basic structure in terms of ingredients and preparation, but remarked himself: “And remember the first rule of the bartender: Nothing Is Written in Stone” ( “Let's think of the top rule of the bartender: nothing is set in stone ” ). Building on this, the authors of the trade journal Mixology identified 13 so-called "key cocktails" as typical key recipes and located these in their 2010 standard work "Cocktailian" on a taste coordinate system with the axes salty ↔ bitter / tart / dry and sweet ↔ sour . They grouped all other recipes in the collection around these 13 drinks, but, like Jerry Thomas 150 years before them, could not do without a category for other, non-classifiable mixed drinks (“Birds of Paradise and Border Crossers”).

Further classifications

Finally, mixed drinks can also be sorted according to their time of origin (e.g. prohibition cocktails), phases of cocktail history (e.g. "classic" or "modern" drinks), origin of the ingredients according to country or region (e.g. Caribbean Drinks, tropical cocktails) or fashionable trends, e.g. B. Classify tiki drinks, cuisine style cocktails (using fresh ingredients from the kitchen) and the like.

For each drink group, very different criteria can be relevant, so that there is always the difficulty of clearly assigning a recipe. In addition, the transitions within one criterion are fluid - so many “medium-sized” cocktails cannot be clearly classified as either a short drink or a long drink.

As a result, there is no official, universally recognized system of cocktail groups into which every drink can be assigned unequivocally. Also, the professional association International Bartenders Association (IBA) ranked official IBA cocktails until 2011 rather arbitrary with no clear criteria following various groups and distinguished between pre-dinner cocktail, after-dinner, highball Style, Popular cocktails and a single special cocktail . The list was revised at the end of 2011, since then the drinks have only been listed very roughly according to their time of origin in the three groups The Unforgettables (unforgettable drinks), Contemporary Classics (contemporary classics) and New Era drinks (e.g. drinks of the new age).

Well-known cocktails

Over the years, classics have emerged that are known worldwide and whose basic recipes repeatedly serve as the basis for new creations and variations. The following list contains internationally known mixed drinks with their typical components.

The International Bartenders Association (IBA) has published standard recipes in several categories for some so-called “IBA cocktails” . In addition, the German Barkeeper Union (DBU) lists recipes of the “30 most important classics” and 5 “Modern Classics” in their bar handbook for beginners (2017). All IBA cocktails and the classics defined by the DBU are included in the list and marked accordingly; the legend can be found at the end of the section.

All - including not mentioned here - alcoholic cocktails with articles in the German Wikipedia are in the category of alcoholic cocktail contain, in addition there are the categories of Alcoholic hot drink and cocktail party .

In 2013 a survey by a travel portal of 500 hotels around the world showed the most frequently ordered drinks in hotel bars: 1. Mojito , 2. Spritz , 3. Gin Tonic , 4. Caipirinha , 5. Martini Cocktail , 6. Beer , 7. Cosmopolitan , 8. Margarita , 9. Sex on the Beach , 10. Cuba Libre .

Champagne and other sparkling wine drinks:

- Champagne cocktail : champagne, sugar, Angostura bitters

- Bellini : champagne, sugar, peach pulp

- French 75 : champagne, gin, lemon juice, sugar syrup

- Kir Royal : champagne, crème de cassis

- Mimosa : champagne, orange juice

- Prince of Wales : Cognac or Rye Whiskey , Liqueur, Angostura Bitter, Champagne

- Spritz Veneziano or Aperol Spritz : white wine or Prosecco , bitter liqueur, soda water

- Hugo : Prosecco, elderflower syrup, lime, soda water

- Old Cuban : Rum, lime, sugar syrup, Angostura, mint, champagne

- Airmail : rum, lime, honey, champagne

- Barracuda : Prosecco, rum, Galliano , lime juice, pineapple juice

Aromatic or dry short drinks , including pre-dinner cocktails ( aperitifs ):

- (Dry) Martini : gin and vermouth

- Dirty Martini : variant with olive broth

- Vespers : gin, vodka and lillet

- Pink Gin : Gin, Angostura bitter

- Derby : gin, bitter peach, mint leaves

- Bijou : gin, vermouth, chartreuse

- Tuxedo : gin, vermouth, maraschino , absinthe , orange bitters

- Bronx : gin, vermouth, orange juice

- Manhattan : whiskey, vermouth, angostura bitters

- Rob Roy : variant with Scotch whiskey

- Old Fashioned : Liquor, Sugar, Bitters

- Sazerac : (Rye) Whiskey, Sugar, Peychaud's Bitters

- Mint Julep : whiskey, sugar, mint

- Kir : white wine, crème de cassis

- Negroni : gin, campari , vermouth

- Americano : Campari, vermouth, soda water

Sweet or creamy short drinks , including after-dinner cocktails ( digestifs , dessert cocktails):

- Alexander : Brandy, cocoa liqueur, cream

- Golden Cadillac : Galliano , cocoa liquor, cream

- Golden Dream : Galliano, orange liqueur, orange juice, cream

- Grasshopper : cocoa liqueur, peppermint liqueur, cream

- Porto Flip : port wine, cognac, egg yolk

- Mary Pickford : Rum, maraschino , pineapple juice, grenadine

- Monkey Gland : gin, absinthe , orange juice, grenadine

- El Presidente : rum, orange liqueur, vermouth, lime juice, grenadine

- Black Russian : vodka, coffee liqueur

- White Russian : vodka, coffee liqueur, cream

- Espresso Martini : vodka, coffee liqueur, espresso

- Apple Martini : vodka, apple liqueur, orange liqueur

- French Martini : vodka, raspberry liqueur, pineapple juice

- Paradise : gin, apricot brandy (apricot liqueur), orange juice

- Angel Face : Gin, Apricot Brandy, Calvados

- Rose : kirsch, wormwood, strawberry syrup

- Blood and Sand : whiskey, cherry liqueur, vermouth, orange juice

- Rusty Nail : Whiskey, Drambuie

- God Father : Whiskey, Amaretto

- Stinger : Brandy, Peppermint Liqueur

- B52 : coffee liqueur, rum (is lit)

Short drinks on Sour basis:

- Whiskey Sour : whiskey, lemon juice, sugar syrup

- Whiskey Smash : whiskey, lemon, sugar syrup, mint

- Pisco Sour : Pisco, lemon juice, sugar syrup

- Daiquiri : rum, lime juice, sugar syrup

- Ti Punch : Rhum Agricole , lime juice, sugar syrup

- Hemingway Special , also: Papa Doble, Hemingway Daiquiri, (Daiquiri) El Floridita : rum, lime juice, grapefruit juice, maraschino

- Bacardi Cocktail : rum, lime juice, grenadine

- Gimlet : Gin, Lime Juice Cordial

- Gin Basil Smash : gin, lemon juice, sugar syrup, basil

- Daisy : liquor, lemon juice, grenadine

- Jack Rose : Applejack , citrus juice, grenadine

- Jack Rabbit : Applejack, lemon juice, orange juice, maple syrup

- Brandy Crusta : Brandy or cognac, lemon juice, sugar syrup, Angostura, possibly liqueur

- Margarita : tequila, lemon juice, orange liqueur

- Tommy's Margarita : tequila, lime juice, agave syrup

- Snap Dragon : tequila, lime juice, elderberry syrup, grapes

- Sidecar : Brandy, Lemon Juice, Orange Liqueur

- White Lady : gin, lemon juice, orange liqueur

- Between the Sheets : Rum, Cognac, Lemon Juice, Orange Liqueur

- Blue Moon (Cocktail) : gin, lemon juice, crème de violette

- Aviation (cocktail) : gin, lemon juice, maraschino , crème de violette

- Casino : gin, lemon juice, maraschino , orange bitters

- Last word : gin, lime juice, maraschino, chartreuse

- Yellow Bird : rum, lime juice, galliano , orange liqueur

- Scarlett O'Hara : Southern Comfort , citrus juice, cranberry juice

- Kamikaze : vodka, lemon juice, orange liqueur

- Lemon Drop Martini : lemon vodka, lime juice, orange liqueur

- Cosmopolitan : lemon vodka, lime juice, orange liqueur, cranberry juice

- Clover Club : gin, lemon juice, raspberry syrup (or grenadine), egg white

- Pink Lady : gin, applejack, lemon juice, grenadine, egg white

- Penicillin : Scotch whiskey, ginger liqueur, lemon juice, honey syrup

Sour- based long drinks :

- Gin Fizz : gin, lemon juice, sugar syrup, soda water

- Ramos Fizz : Gin Fizz with whipped cream, egg white, orange blossom water

- Tom Collins : gin, lemon juice, sugar syrup, soda water (IBA: as a variant of John Collins )

- John Collins : Whiskey, lemon juice, sugar syrup, soda water

- Caipirinha : cachaça, limes, sugar

- Mojito : rum, lime juice, sugar, soda water, mint

- Bramble : gin, lemon juice, sugar syrup, blackberry liqueur

- Russian Spring Punch : vodka, lemon juice, sugar syrup, crème de cassis

More long drinks and highballs :

- Gin Tonic : Gin, Tonic Water

- Whiskey Soda : Scotch whiskey , soda water

- Whiskey Cola : Bourbon Whiskey , Cola

- Cuba Libre : rum, lime juice, cola

- Dark and Stormy : Rum, Ginger Beer

- Moscow Mule : vodka, lime juice, ginger beer

- Horse's Neck : Cognac, ginger lemonade , bitters

- Pimm's Cup : Pimm’s (liqueur), lemonade, cucumber and fruits

- (Lime) Rickey : Liquor, lime, soda water

- Paloma : tequila, grapefruit lemonade

- Campari Orange : Campari, orange juice

- Screwdriver : vodka, orange juice

- Harvey Wallbanger : Vodka, Galliano , orange juice

- Sea Breeze : vodka, cranberry juice, grapefruit juice

- Sex on the Beach : vodka, cranberry juice, orange juice, peach liqueur

- Straits Sling : gin, cherry liqueur, Bénédictine, lemon juice, bitters, soda water

- Singapore Sling : Gin, cherry liqueur , Bénédictine , orange liqueur, lime juice, grenadine, bitters, pineapple juice

- Tequila Sunrise : Tequila, orange juice, lemon juice, grenadine

- Long Island Iced Tea : gin, rum, vodka, tequila, orange liqueur, lemon juice, cola

Tropical, Karabik and Tiki drinks:

- Mai Tai : rum, orange liqueur, almond syrup , lime juice, sugar syrup

- Punsch or (rum) punch: arrak or rum, sugar, citrus fruits, water or tea, spices

- Planter's Punch : rum, citrus juice, fruit juices, grenadine

- Zombie : several types of rum, fruit liqueurs, fruit juices

- Hurricane : rum, lime juice, passion fruit syrup

- Colada : drink group with coconut and cream

- Piña Colada : coconut, rum, pineapple juice

- Swimming pool : rum, vodka, coconut, pineapple juice, cream, blue curacao

- Painkiller : rum, coconut, pineapple and orange juice

- (Rum) Swizzle : Rum, fruit juices, falernum (lime and clove liqueur) or syrup

- Sangría : spirits, wine, fruit juice, fruits

- Batida : cachaça, fruit juice

Spicy mixed drinks:

- Bloody Mary : vodka, tomato juice, spices

- Bull Shot : vodka, beef broth , spices

- Vampiro : tequila, citrus juices, honey, chilli, onions, spices

Hot mixed drinks ("Hot Drinks"):

- Irish Coffee : Irish whiskey, coffee, sugar and cream

- Brandy Egg Nog : brandy, sugar, egg (yellow), milk

- Tom and Jerry : Brandy, rum, egg, sugar, milk or water

- Blue Blazer : whiskey or brandy, boiling water, sugar

- Grog : rum, sugar, water

- Hot Buttered Rum : Grog with butter and spices

- Hot Toddy : Liquor, Sugar, Water, Spices

- Jagertee : native rum , black tea

Legend: IBA cocktails

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "IBA Cocktail" in the Contemporary Classics category with a standard recipe from the International Bartenders Association ( IBA), as of February 15, 2012.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "IBA Cocktail" in the New Era Drinks category with a standard recipe from the International Bartenders Association (IBA), as of February 15, 2012.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae “IBA Cocktail” in the category The Unforgettables with a standard recipe from the International Bartenders Association (IBA) as of February 15, 2012.

Legend: DBU cocktails

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Belongs to the 30 most important classics , with a standard recipe published in: Das Bar Handbuch für Einsteiger . German Barkeeper Union (DBU), Lauffen am Neckar 2017.

- ↑ a b c d e Belongs to the five Modern Classics , with a standard recipe published in: The bar manual for beginners . German Barkeeper Union (DBU), Lauffen am Neckar 2017.

Components of cocktails

Cocktails usually contain around 6 cl of alcoholic ingredients, which is also the internationally usual amount for most short drinks if they do not contain any other non-alcoholic ingredients. There is also about 1–2 cl of melt water. Long drinks contain 16 cl or more of liquid.

Basic composition

The most important mix ingredients include the spirits gin , vodka , whiskey and whiskey , brandy , rum , tequila and cachaça , as well as liqueurs , vermouth and champagne . They form the so-called basis of most cocktails. The base is almost always the main component of a drink, often has the largest proportion of the total liquid in terms of quantity and, with the exception of vodka, determines the taste. With whiskey sour the basis is whiskey, with gimlet usually gin, with daiquiri rum. In some drinks two, rarely three spirits together form the basis.

The second most important component is the modifier (also aroma generator), which helps determine the direction of the cocktail, but does not completely change the basic direction of the base. Typical modifiers are vermouth, liqueurs and fruit brandies , citrus juices and syrups . In a tequila sunrise , grenadine is the modifier to the tequila base, in a classic gin-based martini it is the vermouth, in a zombie (base: different rums) the modifiers are apricot brandy, grenadine and lemon juice.

Many cocktails also contain a flavoring part , i.e. tiny amounts of cocktail bitters , aromatic spirits, liqueurs or syrups. They often determine the color or round off the drink's taste, but must be used sparingly in order not to make the drink inedible. Bitters like Angostura or Peychaud’s are usually only used drop by drop.

Mixers or fillers are ingredients that "lengthen" a drink with more liquid, thereby reducing the alcohol content and rounding off an originally "hard" taste, but without covering the basic direction. A gin and tonic consists of the base (gin) and the mixer / filler tonic water , with Bloody Mary tomato juice is the filler. Usual Filler are soda water , tonic , cola , ginger ale or ginger beer , bitter lemon and other carbonated drinks, fruit juices (especially orange juice , passion fruit juice, pineapple juice, cranberry juice) and wine, sparkling wine and champagne.

Alcohol-free ingredients

Citrus juices play a particularly important role in many cocktails. Lemon or lime juice together with a spirit and sugar syrup or combined with a sweet liqueur form the basic structure for the largest and most important drink group, the sours . While industrially produced, ready-made sugar-lemon juice mixes (so-called sour mix ) were used for a long time, especially in the USA , it has now become established to only use freshly squeezed juices. A storage time of a few hours should not be detrimental to the taste of citrus juices and is sometimes even seen as an advantage. The use of industrially bottled and packaged citrus juices (especially lemon or lime juice) is unanimously advised against in the specialist literature.

Sugar is, in addition to alcohol, the most important flavor carrier in cocktails and the bar usually in the form of sugar syrup ( sugar syrup used) because it combines easily with other ingredients. The weight ratio of sugar and water during manufacture (usually between 1: 1 and 2: 1) must be taken into account when making the dosage. Some bartenders prefer powdered sugar, which also dissolves easily. In English-language recipes, the specification simple syrup is common for a 1: 1 sugar syrup, this has a degree of sweetness of 50 ° Brix . The standard work Cocktailian recommends making and using 2: 1 sugar syrup yourself, the degree of sweetness of 65 ° Brix roughly corresponds to most industrially produced sugar syrups, i.e. a nearly saturated solution.

Eggs used to be used very often in cocktails. The protein carries z. B. in a sour to a slight foam formation on the drink and ensures a round mouth feel (" umami "). Examples are Clover Club and Silver Fizz . Egg yolk is characteristic of flips or the Knickebeins that were popular in Germany in the 1960s.

With a fat content of around 30%, cream is a natural flavor carrier and can be found in many dessert cocktails such as Alexander and Grasshopper , but also in coladas and many fancy drinks .

With the renaissance of bar culture since the turn of the millennium, fresh ingredients such as freshly squeezed juices, fresh fruit and vegetables, homemade syrups , spices and herbs have increasingly found their way into the bars. When using many ingredients from the kitchen, one speaks of cuisine style .

ice

An often underestimated ingredient at the bar is ice cream. Without ice, cocktails and long drinks would never have achieved their current level of popularity, says the “Cocktailian” , and continues: “Its cooling effect and the melt water as well as its physical properties, which are necessary to aromatically combine different ingredients, make it an essential component mixed drinks. "

Except for the few hot drinks , cocktails are always prepared with ice and served ice-cold. A certain degree of dilution by the melt water (1–2 cl) that is created when stirring or shaking is desirable and plays an important role in taste , especially in highly alcoholic short drinks such as martini .

There are different types of ice cream at the bar:

- Ice cube: Cube with an edge length of 2 to about 4 cm. Ice cubes are used to shake and stir drinks and serveto keep the liquid cool longerin long drinks andcocktails served "on the rocks" (on ice cubes). Ice machines often only produce hollow ice cubes (which dilute too quickly in the drink) or uneven shapes; However, special devices can also produce uniform whole ice cubes with an edge length of around 3–4 cm without clouding or air inclusions.

- Cracked Ice : before freezers and ice cube machines found their way into bars in the 20th century, ice was stored in larger blocks in the refrigerator and, for the preparation of drinks, was broken into smaller, uneven pieces using an ice pick and hammer used like ice cubes. Some bars are using this technique again today.

- Crushed ice : Fine-grained ice with a quick melting effect. For this purpose (mostly machine-made) full or hollow ice cubes are crushed in an ice crusher . Since crushed ice is watered down quickly, it is often frozen again ( "double-frozen" ) until it is used . There are also special ice machines for crushed ice. Crushed ice is mainly used for Caribbean and fancy drinks and is suitable for making frozen drinks in an electric blender .

- Eiskugel (English ice ball.): Instead of ice drinks are recently strengthened to about 5 cm large scoops of ice cream served to cool the drink for a long time and frozen in special plastic or silicone molds, large of a (English ice balls.) Block of ice melted out or carved by hand with a sharp knife. In Japan, carving of ice cream scoops, ice diamonds and other shapes has become a trend in recent years and is now practiced in bars around the world.

Other, less common ice forms are cublets (mini ice cubes with small edges, often used in the USA and Canada for blending in an electric mixer), cobbler ice (coarsely crushed ice, ideal for caipirinhas) and shaved ice (shaved ice ) . shave = to shave: almost snow-like ice that is scraped off the block of ice with scrapers or claws). In addition, there are molds for all kinds of ice cube shapes, but these are rarely used in bars. Ice cubes can also be colored with food coloring or bar syrups or contain fruits or flowers enclosed as a garnish.

For shaking or stirring cocktails, ice from ice machines is usually used in bars, which is usually only a few degrees below freezing point. However, it cools a drink faster than frozen ice, but also dilutes it more strongly. The cooling effect of ice is greatest at the transition from the solid to the liquid state. So if extremely cold ice is used, it has to be stirred or shaken for longer in order to achieve the same cooling effect with slightly less watering, so that doubly frozen (i.e. frozen again after production and cooled to −15 to −20 ° C) in the practical bar use offers no noticeable advantage when shaking or stirring. However, things are different when the finished drink is kept cool: Frozen (“double-frozen”) ice is better suited as ice cubes in long drinks or for drinks served “ on the rocks ”, as it melts more slowly and keeps the drink cold for a longer period of time. without watering it down.

The usual serving temperature of stirred cocktails is between 2 and 4, for shaken drinks between 0 and 2 ° C, for frozen drinks prepared in a mixer (blender) between −6 and 0 ° C.

preparation

It is characteristic of all cocktails that they are prepared individually and individually for the guest immediately before consumption. The only exceptions are punch and bowls . Both common kitchen utensils and some special bar tools are used in the preparation.

Measuring the liquids

The exact measuring of the liquid ingredients is done with a measuring cup ( jigger ) or by so-called free pouring . With a little practice, the poured out quantities can be precisely dosed using pouring spouts that are placed on the bottles. Experienced bartenders can even work with both hands and speed up their work.

In recipes in German-speaking countries, amounts of liquids are usually given in centiliters (cl), internationally also often in milliliters (ml), in the USA in (US) fluid ounces (fl. Oz. Or oz, with 1 oz about 29.6 ml, in practice this corresponds to rounded 3 cl). This measure was also called a pony . Other historical bar measures are dram (dr) = 1 ⁄ 8 oz (≈ 3.7 ml), teaspoon (tsp) = 2 dr = 1 ⁄ 6 oz or 12 dashes (≈ 5 ml), tablespoon (Tbsp) = 1 ⁄ 2 oz. (≈ 15 ml), jigger (jig) = 3 Tbsp = 1.5 oz. (≈ 45 ml), cocktail glass = often 2 oz (≈ 60 ml), wineglass = often 2 oz (≈ 60 ml), gill (gi) ≈ 120 ml, split = 1 ⁄ 4 or 1 ⁄ 2 wine bottle (with a 0.2 gal bottle i.e. 6.3 oz. ≈ 187 ml, or 12.6 oz. ≈ 375 ml), cup (cp) = 2 gi = small tumbler = 4 oz. (≈ 240 ml), pint (pt) = large tumbler = 2 cp = 16 oz. (≈ 480 ml), quart (qt) = 2 pt = 32 oz (just under 1 liter), gallon (gal) = 16 cp = 4 qt (≈ 3.8 liters). The old British imperial ounce is smaller (1 oz. ≈ 28.4 ml) than the American one, since 1 (imp.) Gill is 5 oz. pint, quart and gallon are each 20% larger. The word shot can mean different amounts in cocktail recipes, usually 1 or 1 ½ oz. Simon Difford recommends 25 ml for his recipes.

The composition of a drink in tenths or sixths of parts or fractions of the whole ( 1 ⁄ 2 , 1 ⁄ 3 , 1 ⁄ 4 etc.) is rarely noted. In addition, the following information is customary internationally:

- 1 bar spoon (short BL, English barspoon, short bsp) = about 0.5 cl (1 larger teaspoon ). The pestle-like back of many bar spoons is also suitable for pressing on fruits, herbs or sugar cubes.

- 1 dash = 1 splash. Depending on the liquid, the actual amount can vary between a few drops (for bitters ) and a few ml, but is usually less than 1 BL.

Pestles ("muddling")

Since the 1990s, fresh ingredients have been increasingly used in bars and a new technique has been added: pounding or "muddling" with a pestle . This approximately 20 cm long mortar made of wood, metal or plastic is used in the shaker to extract the aromas from fruits, herbs or spices. For example, you mash the lime pieces in a caipirinha to release their juice and essential oils from the peel.

Mixing and cooling

To mix the ingredients and cool them down quickly, various basic techniques have developed:

- Shaking ( shaking ): The most common method of preparation, especially for cocktails that contain juices, eggs or cream. A cocktail shaker is filled with ice cubes and the liquid ingredients, closed and shaken vigorously for about 10 to 20 seconds - longer for ingredients that are difficult to mix, such as in a Ramos Gin Fizz . Hard shake describes particularly vigorous shaking, a technique that the Japanese bartender Kazuo Uyeda in particular has perfected. With a dry shake , the shake is exceptionally first without ice (but often with the metal spiral of a bar strainer in the shaker) so that more foam is created. With the speedshake , which is mainly used in discos and in flair bartending for big fancy and Caribbean drinks, only a shaker top is placed on the guest glass and shaken directly in it. The resulting drink is then no longer strained, but as an exception served with the shake ice.

- stir : cocktails that only contain alcoholic ingredients that easily combine with each other are usually stirred on ice, as they would become cloudy when shaken. This is done in a mixing glass or the glass part of a Boston Shaker with the help of a long- handled bar spoon . Classic examples are martinis and Manhattan .

- Mixing (English blend): All ingredients are mixed , usually with crushed ice, in a stand mixer (English blender). Usual technology for frozen drinks, tiki cocktails and cocktails in general whose ingredients are otherwise difficult to combine, e.g. B. Piña Coladas .

- Build in glass: The liquid ingredients are mixed together on ice directly in the guest glass by briefly stirring. Often with long drinks with few ingredients (e.g. spirits and juice), those with carbonated fillers that must not be shaken, such as highballs, collinses and champagne cocktails and drinks with purely alcoholic ingredients, but which are served on ice anyway, z. B. Rusty Nail .

- layer : A specialty are pousse cafés , where several liqueurs are carefully layered with the help of a bar spoon so that they do not mix in the glass. Exceptionally, no ice is used here.

- Throw : a technique widespread in the 19th century, in which the ingredients are mixed by sliding them several times - often in a high arc - from one cup to another. However, cocktails with cream, fruit juices, eggs and syrups are better shaken.

Strain and serve

Insofar as it was not already mixed in the guest glass, the final mixture will ultimately into a suitable glass strained (English strain.): Where a holding strainer (engl. Strainer) the fused ice in a shaker back or it is a three-part cocktail shaker with integrated sieve used in the top. The ice in the shaker is always thrown away. When double-Strain (Engl. Double strain or finest rain) is held under the strainer still a small, close-knit colander (strainer) to filter out fresh to even the finest ice chips or small particles ingredients such as herbs, spices or fruits.

For long drinks, fresh ice in the drinking glass is used to keep the drink cool. The purpose of ice cubes is not, as is often assumed, to simulate a larger filling quantity and to withhold supposedly expensive liquid from the guest, but to prevent the drink from melting down and watering down quickly. Classic short drinks , on the other hand, are usually drunk “straight up” , i.e. without ice, especially when they are served in a stemmed glass such as a cocktail or martini bowl, margarita glass, sour glass, etc. These glasses are often precooled by storing them in the freezer until use or by filling them with ice and some cold water while preparing the drink, which is thrown away before straining. If drinks are served on ice cubes, this is called on the rocks .

Cocktail glasses

Cocktails are always served in a suitable, clean, dry and, if necessary, pre-chilled cocktail glass.

A cocktail bowl (also known as a coupette ) is suitable for most short drinks , alternatively a small wine goblet or a champagne bowl . A variant of the cocktail bowl is the funnel-shaped martini glass ( cocktail tip ), in which many other drinks can be served in addition to martinis . Stem glasses with a tulip-shaped cup, similar to champagne or south wine glasses, are often used for sours . For all short drinks in stemmed glasses, they are served without ice in the glass and without a drinking straw. To ensure that the freshly prepared drink stays cold longer, the glasses should be pre-cooled (“frozen”) before straining .

Other special shapes for cocktail glasses are the hurricane glass and other so-called fancy glasses, especially for exotic and fruity drinks. Moreover, there are beakers (including tumblers , Fizz-, highball or highball glasses) in all sizes and shapes. In them, short or long drinks are usually served " on the rocks ", with fresh ice cubes in a glass.

In contrast to wine, sparkling wine or champagne, an empty cocktail glass is not refilled, but a fresh glass is used for each drink. The only exceptions are punch , bowls and so-called pitcher drinks , which are served in a mug for a larger group. Special nosing glasses are suitable for pure tasting of spirits .

decoration

In addition to the right glass, the decoration above all offers the opportunity to put the cocktail in the right light. Classic cocktails are usually only given an economical, sometimes no decoration at all, which may also be due to the fact that when they were made, there was no comparable selection of fresh fruit and other fresh ingredients available all year round as we know it today. Fancy drinks and tropical cocktails are often decorated particularly lavishly, although Charles Schumann warns: “For me, a cocktail is not a fruit and vegetable salad and certainly not suitable for an umbrella or national flag. Americans, who are afraid of the imagination of such bartenders, therefore demand 'no vegetables please' with their drinks. ” Fruits are usually attached to a cocktail stick.

Typical cocktail sets are

-

Citrus fruits (lemons, limes, oranges, depending on which juice is in the drink)

- Zeste , twist : a mostly thumb-sized, very thin piece of the outer shell (without the bitter white, English pith) of untreated fruit. Short drinksare often"sprayed off"with a twist , by quickly twisting the ends of the shell piece against each other so that the essential oils splashing out wet the surface of the cocktail. The edge of the glass is also often rubbed in and the zest is then added to the drink. A special feature is the "flame" of a drink: a previously heated twist is jerked together and at the same time a match or lighter flame is held over the drink so that the fine mist of essential oils evaporates with a bright flame mainly optical, but also olfactory effect.

- Disc : is often placed on the edge of the glass or placed in it

- Spiral: a long, thin, spiral-shaped piece of bowl is cut off with a lemon decorating knife and usually hung over the edge of the glass.

- Column, Schnitz (English wedge): a lime or lemon is divided lengthways into quarters, sixths or eighths, depending on its size, and the schnitz is then often squeezed out over the drink and then poured into it.

- Cocktail cherry : It is either added to the drink or, often with other fruits, attached to a skewer on the edge of the glass. Cherriesthat have previously been marinated in maraschino are preferredinstead of the artificially colored, candied cherries.

- Fresh mint : not only has a decorative effect, when you drink it, its aroma fills your nose.

- fresh fruits : whole physalis , berries, cherries, grapes ; Slices, wedges or pieces of pineapple , kiwis , melons , carambola , figs , kumquats , apples , pears , etc. Fruits are either placed directly on the edge of the glass or attached to a cocktail stick and placed on the glass. They are also suitable for making small figures.