champagne

The champagne ( French le champagne ) is a sparkling wine , which from grapes is produced according to strict rules laid down in the wine region Champagne (French. La Champagne ) in France are read. In many parts of the world it is considered the most festive of all drinks. The carbon dioxide (→ carbon dioxide ) dissolved in the wine is created during a second fermentation in the bottle ( méthode traditionnelle or méthode champenoise ). Champagne enjoys the status of an Appellation d'Origine Protegée , even if this is not noted on the label .

Differentiation from sparkling wine

The French name “Champagne” has been protected by the INAO as an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée since June 29, 1936 . According to German food law , other sparkling wines must be designated as sparkling wine , depending on their production and country of origin . Sparkling wines produced by bottle fermentation are called Vin Mousseux or Crémant in France and Luxembourg , Cava in Spain , Spumante Metodo Classico in Italy , Winzersekt in Germany and Hauersekt in Austria, provided that the base wines come from a single winery and are produced by the latter itself or in a producer group have been.

In the former Soviet Union, every sparkling wine was called "Schampanskoje". Although Russian or Ukrainian sparkling wine has been traded as "Igristoje" ( igristoje wino = "sparkling wine") for many years , the original word is still widely used.

Champagne is subject to manufacturing regulations, compliance with which is monitored by independent bodies. Which includes:

|

|

Production of champagne

Growing area

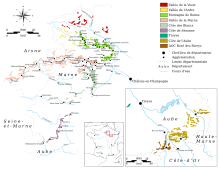

The area in which grapes for champagne can be grown was established on July 22, 1927. It comprises approx. 33,500 hectares , which is now almost completely planted. An expansion has now been decided. Because of its extension of around 150 km, the area is not homogeneous. In the so-called terroir , not only are the microclimates different, but also the soil types. It is therefore divided into different wine-growing regions, the most important of which are Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, Côte des Blancs and Côte des Bar . For details, see Champagne (wine-growing region) .

Grape varieties

Three grape varieties are used almost exclusively for champagne : the red grape varieties Pinot Noir ( Pinot Noir ) and Pinot Meunier (Müllerrebe or Schwarzriesling) as well as the white grape variety Chardonnay . Approved, but since the phylloxera crisis almost disappeared, the varieties are Arbane , Petit Meslier and Pinot Gris Vrai ( Pinot Gris ) and Pinot Blanc ( Pinot Blanc ), who considers himself particularly in Celles-sur-Ource (Aube). The mixture of the varieties determines the character of the respective champagne. In one part of Champagne, the Côte des Blancs, single-variety Chardonnay cuvées are preferably produced, the Blanc de Blancs . Pinot Noir makes up 38.4% of the Champagne vineyards, Pinot Meunier 33.3% and Chardonnay 28.3%. Pinot Noir gives the wine its fullness, Chardonnay the finesse, Pinot Meunier the fruitiness. The term Blanc de Noirs for white wine made from dark grapes was originally coined in Champagne. Blanc de Noirs champagnes are rarely found (e.g. from Bollinger, Bruno Paillard or Mailly ) and mostly come from areas around Aÿ , Bouzy, Mailly, Hautvillers and Verzenay.

Cultivation, harvest and pressing

Strict quality standards apply to the cultivation of grapes and the production of champagne. With 7,000 to 8,000 vines per hectare, the planting density is much denser than in most other wine-growing regions. In any case, the maximum yield is limited to 15,500 kg of grapes per hectare. In difficult years it can be set well below this. The harvest must be done by hand so that the grapes remain intact. Reading takes place in the mannequins, which are baskets or small containers that, unlike the German grape chests, are not built to hold back juice. The grapes of the red base wine varieties Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier are pressed quickly so that as little red color as possible gets into the base wine. A maceration for the production of rosé champagnes is the exception. In this case, 10–20% red wine is usually added to the white base wine.

Since 1983, 160 kg of grapes have to be used to produce 102 liters of must; until then it was only 150 kg. But only the first 82 liters, also known as Cuvée , are of really high quality. The rest, which is pressed twice and is called Première and Deuxième Taille , is less good because more bitter substances get into the must through the pressing. The best champagnes are therefore only made from the cuvée, while the Tailles are used in the standard grades. Due to the losses in wine-growing and dégorging, you get a total of around 100 liters of champagne, i.e. 133 bottles of 0.75 liters each.

Assemblage

First, the base wine is made from the must through alcoholic fermentation . Some of the producers then allow malolactic fermentation , i.e. biological acid degradation. Once this process is complete, the base wine can be put together for bottle fermentation.

Around 80% of all champagnes are blended from base wines from different vintages to form an assemblage and come onto the market without a vintage (BSA = brut sans année). This assemblage is an important part of making champagne. Up to a hundred different wines can be combined for one champagne. Around 70% of the basic wine of a typical vintage-free champagne is from the current vintage. The rest are older vintages, the so-called reserve wines. With the help of the reserve wines, it is possible for the champagne houses to produce an equivalent and almost the same tasting champagne every year. Today there are around 20,000 champagne products.

Bottle fermentation

In order to enable the second fermentation, cane or beet sugar and a little yeast , called liqueur de tirage , must be added to the wine . The bottles are then usually closed with a crown cap that has a plastic capsule ( bidule ) inside , which is used to collect the depot , i.e. the sediment that forms in the bottle during long periods of storage. The secondary fermentation usually takes place between March and May of the year following the harvest and takes about three weeks. The alcohol content of the champagne then increases by around 1.2 percent by volume compared to the base wine. This process may only be called “ méthode champenoise ” in Champagne .

After fermentation on the yeast, the champagne improves and can be stored for many years. The dead yeast undergoes an enzymatic decomposition process ( autolysis ), which gives the champagne its aromas. Furthermore, the autolysis ensures a fine solution of the carbon dioxide in the wine, which later ensures the fine, long-lasting perlage in the glass . A minimum of 15 months of maturity sur lattes ("on laths") is required for vintage champagne and three years for vintage champagne.

Shake

The yeast must be removed from the bottle before shipping. To do this, the bottles are first washed and the deposited yeast is removed from the bottle wall. The prepared bottles are placed in pupitres de remuage ( vibrating panels ) or placed in gyro pallets. On the first day the bottles are almost horizontal, slightly inclined towards the crown cap. The bottles are then shaken for a period of 21 days. They are left at the same angle for the first two weeks, but rotated by a tenth of a turn every day. An experienced vibrator, the “remueur”, handles around 40,000 to 50,000 bottles every day.

In the last week they are then turned upside down every day. Shaking hands is seldom these days, at Moët & Chandon, for example, only 9 million out of a total of around 35 million bottles a year. Rather, robots usually take over the machine-controlled shaking. Several dozen bottles are sorted head- butted into large, cube-shaped wire cages (gyropalettes) that are electrically driven and electronically controlled. The process is called "remuage mécanique" . The results are equivalent for manual work and mechanical vibration. If the bottles are upright, the yeast has collected in the neck of the bottle.

Disgorging

To get the settled yeast out of the bottle, the bottle neck is nowadays passed through a cooling brine (ice bath) so that the yeast freezes as a plug. Then the crown cap is opened and the ice plug shoots out of the bottle due to the excess pressure. In the past, the deposited yeast plug was removed from the bottle without freezing ( dégorgement à la volée = disgorging on the fly). This method is rarely used today because it requires specially trained personnel and causes greater losses than the modern method.

Transferring to other bottle sizes may only be used for bottle sizes below half (i.e. up to 0.375 L) and above the Jeroboam or double magnum (i.e. from 3.0 L). With the exception of vintage champagne, after the second fermentation, it is also allowed to decant it into half bottles (i.e. 0.375 L) annually for up to 20% of the amount of half bottles produced in the previous calendar year.

Dosage

Before the bottles are finally closed with a champagne cork, the loss of liquid must be compensated for by filling up. The shipping dose is added here. This dosage is a secret of the champagne manufacturers. It gives the champagne a distinctive note and above all determines the taste from extremely dry to sweet. The dosage can, for. B. consist of sweet wines or sweet reserve of the champagne base wine. As a rule, sugar solution is also added. In some houses it is still common today to use an Esprit de Cognac , which compensates for the loss of alcohol that would otherwise occur, especially with very sweet champagnes. Liquid must be removed from the bottle to dose sweet champagne. The following gradations are common in the flavors:

- Ultra Brut, Brut Nature or Brut integral, non dose or zero dosage: no dosage, 0 to 3 g / L residual sugar

- Extra Brut: Dosage with 0 to 6 g / L residual sugar

- Brut : Dosage with 0 to 12 g / L residual sugar

- Extra Sec or Extra Dry: Dosage with 12 to 17 g / L residual sugar

- Sec: Dosage with 17 to 32 g / L residual sugar

- Demi Sec: Dosage with 32 to 50 g / L residual sugar

- Doux: Dosage with more than 50 g / L residual sugar (rarely with champagnes)

In addition to champagne, many international sparkling wines are also produced using this method.

Champagne in the bottle

For sparkling wines such as champagne, the bottle has to meet special conditions, as it has to withstand the pressure generated during the second fermentation. Practically all champagne bottles have a conical recess in the bottom, which improves the pressure resistance of the bottle. The only exception with a flat bottom is the clear bottle from Roederer Cristal , the bottom of which is particularly thick.

Champagne bottles can be opened with a champagne saber, this process is also known as sabring.

Bottle sizes

Champagne is offered in different bottle sizes. The standard size is the 0.75 L or 1/1 bottle. Separate names have been established for the other bottle sizes, mostly biblical names.

Piccolo is the name for 0.2 liter champagne bottles. This bottle size was already widespread around 1900 and was primarily used to market the Medicinal-Sects marketed through pharmacies and hospitals . The word and image brand Piccolo rsp. Pikkolo is protected as a trademark by the companies Kessler Sekt and Henkell & Co. Sektkellerei KG.

| Normal size | liter | designation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 ⁄ 4 | 0.2 | Quart / piccolo |

| 1 ⁄ 2 | 0.375 | Demi / Fillette |

| 1 ⁄ 1 | 0.75 | Bouteille |

| 2 | 1.5 | Magnum (Latin for "the big one") |

| 4th | 3 | Jeroboam (after 1st king of the northern kingdom of Israel ); also called double magnum |

| 6th | 4.5 | Rehoboam (after 1st King of the Kingdom of Judah ) |

| 8th | 6th | Methuselah (after the oldest person in the Bible); also Impériale called |

| 12 | 9 | Salmanazar (after a biblical king of the Assyrian Empire) |

| 16 | 12 | Balthazar (after a member of the Three Kings ) |

| 20th | 15th | Nebuchadnezzar (after a biblical king of the Babylonian Empire) often Nebuchadnezzar called |

| 24 | 18th | Melchior (after a member of the Magi ) or Goliath (after a biblical warrior of the Philistines ) |

| 35 | 26.25 | Souverain or Sovereign |

| 36 | 27 | Primacy (Latin for "the first") |

| 40 | 30th | Melchizedech (Hebrew for "King of Justice"); Also Midas called |

The production of bottles beyond the Jeroboam is complex and therefore expensive. Accordingly, champagne is rarely available in such bottle sizes. A Primat bottle - and since 2002 also the Melchisedech bottle - is only offered by Drappier; the Armand de Brignac champagne produced by the House of Cattier has also been available in a 30 liter bottle that bears the Midas name since 2011; In 1987, Taittinger had eight Sovereign bottles with a capacity of 26.25 liters each produced and one of them was filled. This was used exclusively for the christening of the MS Sovereign .

The bottle size has a clear influence on the taste quality of the content. The same cuvée usually tastes much more harmonious from the magnum bottle than from the 1 ⁄ 1 bottle and also matures better. Larger formats, on the other hand, no longer offer any advantage, as they were not necessarily fermented in the same bottle.

Champagne corks

The cork of a champagne bottle has, as with all corks, originally an elongated cylindrical shape. The well-known mushroom shape with a conical base emerges later. The cork is strongly compressed and only about two thirds of its length is inserted into the bottle neck and secured to the bottle neck with a muselet (wire mesh) or agraffe (metal bracket). The cork adapts to the neck of the bottle and loses its elasticity during storage. Only the lower part of the cork that comes into contact with the liquid retains its original elasticity for longer. Therefore, after opening the bottle, the lower part of the cork expands to its original diameter, while the upper base piece retains the diameter of the bottle neck due to its brittleness. The restoring force of this fungus becomes smaller the longer the cork has been in the bottle.

For cost reasons, the champagne cork is divided into two parts. While the upper part of the cork (the head) consists of press corks, two discs made of natural cork are glued to the bottom. This part is in direct contact with the sparkling wine. After gluing, the cork is sanded. After a quality selection, the surface is often sealed with paraffin . This seal increases the tightness of the cork and facilitates the corking process. So that the cork stays in the bottle despite the high pressure, it is held by a muselet (wire mesh) or an agraffe (metal bracket) and a champagne lid .

In the larger bottle formats, the corks are made entirely of natural cork, but there are also layers of different cork quality that are glued together in different ways. Usually there are two to three slices of good quality at the bottom, followed by a large, lower quality piece that makes up the bulk of the cork. Often a disc of good quality is then placed on top of the cork, on which the name of the champagne is also printed.

The use of natural cork as a bottle cap can lead to off-taste tastes (colloquially: “cork tone ”) even with high-quality champagne .

Shelf life of champagne

Anyone who particularly appreciates the freshness of champagne will open it as quickly as possible after disgorging. Champagne continues to develop in the bottle even after disgorging. The carbonic acid pressure decreases slowly, but the taste becomes more harmonious and the aromas more intense. Simple, no-vintage champagnes usually peak within two years. Good vintage champagnes, on the other hand, can last ten years or more. The rule here is that the longer a champagne has been on the yeast, the slower it will develop negative in the bottle. In order to give the consumer better control, some producers (mainly independent winemakers) have started to mark the time of disgorging on the bottle. Otherwise, only the shape of the cork after opening allows certain conclusions about the time that has passed since disgorging.

Like other sparkling wines, champagne is particularly sensitive to the influence of light, especially fluorescent lamps . It develops a so-called “ light taste ”, which is based on the release of sulfur compounds, especially hydrogen sulfide. The radiation energy is probably absorbed by the riboflavin contained in the champagne , which then sets the breakdown processes in motion. In organoleptic examinations on bottles that were stored for two weeks at different distances from fluorescent lamps, oenologists were able to clearly determine the differences.

An open bottle of champagne should be drunk as soon as possible. With a special pressure cap, a half-full bottle can be kept cool for approx. 24 hours without any major loss of quality.

history

The Romans were the first to grow vines in Champagne. The wine they made from it was still. Because of its proximity to Paris and the activities of the monasteries in Reims and Châlons-en-Champagne, viticulture was preserved without really gaining popularity.

In 1114, the bishop of Châlons-en-Champagne, William of Champeaux, issued the abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Pierre-aux-Monts in Châlons a title deed for the entire monastery property ("grande charte champenoise"), including the vineyards of the present-day cultivation area, etc. . a. Hautvillers, Cumières, Aÿ and Oger. This document is considered to be the founding act of the Champagne wine-growing region.

During the reign of Henry IV , the name Vin de Champagne prevailed in the capital Paris , after it had previously disappeared in the anonymous mass of wines from the region around Paris. The name was initially not welcomed in the area of origin, as the term Champagne (from Latin campania = field, open landscape) describes a sterile soil that only serves as grazing ground for sheep. Regardless of this, the wine gained more and more friends in the royal courts of France and England.

The course was not set for the now well-known champagne until 1670: the originally still white wine became a sparkling wine. In the 17th century, the wine began to be bottled in the growing area in order to maintain its freshness, as the wine did not survive transport in the barrel. Due to the early bottling, the wine inadvertently continued to ferment in the bottles. If the English had not liked this sparkling wine very much, bottling would probably have been abolished. In any case, the vintners were not enthusiastic about the popping corks, because they caused significant losses. Until well into the 19th century, the cellar and distribution of champagne was dangerous and costly. Due to different glass grades, and depending on the mix of different expiring fermentation processes in the bottles exploding a part already in the basement or during transport through the carbon dioxide overpressure . The cellar masters wore iron masks for work safety, which made them look like medieval torturers. Hence the name Devil's Wine was obvious.

Only the development of controlled bottle fermentation made it possible to master this process. As early as December 17, 1662, the English doctor and scholar Christopher Merret mentioned in an essay submitted to the Royal Society entitled Some Observations Concerning the Ordering of Wines, the targeted addition of sugar, which was aimed at giving the wines freshness and sparkling. The method was significantly further developed by the Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon (1638–1715), then cellarius of the Benedictine abbey of Hautvillers . The art of blending and white pressing of red grape varieties goes back to him. He closed his bottles with a cork that was secured to the neck of the bottle with a cord. At that time he worked with the cellar master Frère Jean Oudart in Saint-Pierre-aux-Monts , who is said to have been the first to use a filling dosage. However, the quality of the resulting wine was still a matter of chance. It was only through the studies of Louis Pasteur that one finally understood the fundamentals of fermentation.

The transport of the wine in bottles was officially allowed in 1728, a year later Nicolas Ruinart founded the oldest champagne house still in existence today. For the Gosset family , the wine trade was documented as early as 1584, but continuity was not assured. The trading houses (e.g. Heidsieck, Moët, Perrier-Jouët and Bollinger) brought it to international marketing. The wine thus gained the reputation it has today. Unlike many other professions, women have played an important role in the development of champagne. The names of the ladies Pommery , Perrier and Clicquot are still known today .

In retrospect, as noted by Arno Widmann: May 25, 1728: Champagne: A royal decree by Louis XV. allows the French to transport wine no longer just in barrels, but also in bottles. This decree is the starting signal for one of the greatest export successes in France, which has now lasted almost three hundred years. The vintners were initially not so fond of the bottles, but since the wine continued to ferment in them and the customers - initially the English in particular - were so enthusiastic about the sparkling drink, the champagne was safe from the moment you learned the bottle to shut down a bomb shop. The Ruinart House, which still exists today, was founded right after the decree in 1729. The founder, a cloth merchant, sensed a Europe-wide opportunity for French sparkling wine.

Until the 19th century, champagne was cloudy because the yeast from the second fermentation remained in the bottle. Then in 1806 Madame Clicquot (" Veuve Clicquot ", today a brand of the Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton Group [LVMH]) invented shaking and disgorging together with her German-born cellar master Antoine Müller and Alfred Werlé. The first vibrating console is said to have been a kitchen table. This technique was first mentioned in André Jullien's Manuel du Sommelier in 1813 . In 1884, Raymond Abelé invented the disgorging machine that worked with an ice bath.

In the 19th century, champagne developed into a luxury drink that was widespread worldwide. In 1804 Veuve Clicquot brought out the first rosé champagne. The first vintage champagnes were bottled around 1870. The bottle labels, which appeared from 1830, contributed to the branding. In 1882, 36 million bottles were produced, three quarters of which were exported. The USA was the largest market after Great Britain . However, the phylloxera invasion put an end to the boom of the 19th century . Champagne was only captured by it relatively late, around 1895. As a result, numerous vineyards were abandoned. The range of grape varieties also changed in favor of the predominant varieties Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay. In 1908 the use of the name Champagne was restricted by law to wines from the Marne and Aisne departments. After violent protests, the winegrowers of the Aube département regained their rights in 1911, which in turn led to unrest in the Marne. As a compromise, the name Champagne was finally limited to the Marne, while the remaining areas were classified as Champagne Deuxième Zone until 1927 . Furthermore, in 1911 all communities were classified on a percentage scale (échelle des crus) , on the basis of which the grape prices were determined from now on.

What is curious is the fact that, outside of Champagne, real champagne was also produced in the capital of Luxembourg. “It is probably no coincidence that it was at the beginning of the legendary Belle Epoque when the Compagnie des Grands Vins de Champagne E. Mercier & Cie decided in 1885 to relocate part of their champagne production to Luxembourg. This out of the free market considerations to provide their international customers in the sales area of the German Customs Union with the price advantage that resulted from the considerable difference between the tariff rates for champagne in barrels and those in bottles. ”The Luxembourgers are probably reminiscent of the Luxembourgish champagne production The Moselle is the only wine region outside of France that is allowed to use the “Crémant” appellation for quality sparkling wine with bottle fermentation.

In 1902, it came because of the secret exchange of a German sparkling wine bottle against a champagne bottle at a naming ceremony in New York to the so-called champagne war , culminating in the German and French emotions in a million process.

The Champagne region suffered particularly badly during the First World War , as it was often the scene of fighting. With the Russian Revolution and Prohibition in America, champagne also lost important export markets. The protection of the designation of origin champagne was imposed on defeated Germany in the Peace Treaty of Versailles ( champagne paragraph ). In 1927 just 9,000 hectares of the approved vineyards were planted. At that time, the need forced many winemakers to break away from the big houses and look for their own sales channels. This is how many small family businesses arose that still exist today. The traditionally high level of unionization of the workers in the cellars is likely to have originated from this period - Champagne is still a bastion of the CGT today . It was not until the 1930s that increasing domestic sales brought an economic recovery.

Since 1936, the feast of St. Vincent of Valencia , the patron saint of winemakers. The veneration of this martyr of the Diocletian persecution of Christians from 304 can be traced back to the Merovingian era, at that time promoted by Childerich I. His status as patron saint of many churches and as patron saint of communities, especially in the wine-growing regions of Burgundy and Champagne, could be explained by folk etymology the French spelling of the name Vin-cent. Even today, midwinter is celebrated on January 22nd and pruning begins.

During the German occupation during World War II , the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne was founded, which today as the umbrella organization oversees production and represents the interests of producers. The increasing prosperity since 1945 finally brought a new boom for champagne, which led production to never-before-seen heights. In 1999, the fixed procedure for determining grape prices based on the percentage classification of all municipalities was suspended. The transition into a new millennium brought record sales of 327 million bottles of champagne in 1999, which was only exceeded in 2007 with 338.7 million bottles. To expand the area under cultivation, the vineyards of the Côte de Sézanne and Vitry-le-François, which were abandoned after the phylloxera crisis, have been planted again in recent years . An expansion of the cultivation area to 357 municipalities has meanwhile been decided. The first champagne grapes should be harvested there in 2017.

Champagne also felt the effects of the global financial and economic crisis: in 2008 sales fell by 4.8% to 322.5 million bottles, in 2009 they fell by a further 9.1% to 293.3 million bottles. In response to the slump in demand, the permitted harvest volume for 2009 was reduced to 9700 kg grapes per hectare.

The Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne has applied to the responsible ministries in Paris to include the champagne wine landscape (Paysages du Champagne) on the UNESCO World Heritage List ; this is intended to honor the unique ensemble of different types of vineyards and the cellars dug in the chalk cliff and to protect their existence.

In July 2010, Swedish divers found a shipwreck in the Baltic Sea with around 30 bottles of champagne on board. Initial evidence pointed to the Veuve Cliquot house and the 1780s, but further investigations led to the first third of the 19th century and the Juglar house, which no longer exists.

economy

Champagne production today

Every year around 2.7 million hectoliters of wine, i.e. around 385 million bottles, are produced. Due to the long fermentation time in the bottle, it is estimated that the equivalent of 1.5 billion bottles is stored in the cellars of manufacturers and trading houses. The industry's annual turnover is around € 4 billion and grew at an annual rate of 4 to 5% until 2007. The largest share of champagne sell the trading houses with 67.4%, followed by self-marketing wine producers (23.5%) and wine cooperatives (Cooperatives) (9.1%). The largest single producer with 62.2 million bottles is the LVMH group with the brands Moët & Chandon , Veuve Clicquot , Krug , Ruinart , Dom Pérignon and Mercier . Smaller listed trading houses with sales between 240 and 360 million euros are Laurent-Perrier , Boizel Chanoine and Vranken-Pommery Monopole .

With around 55% of the purchase volume, France remained the largest customer in the boom year 2007. 25% went to the rest of the EU and 15% was exported to the rest of the world. The largest customer countries were Great Britain (39.0 million bottles), the USA (21.7 million), Germany (12.9 million), Italy (10.3 million), Belgium (9.9 million) and Japan (9, 2 million). Russia and China are enjoying increasing importance. The 980,000 bottles exported to the United Arab Emirates may surprise you, but these are then exported to the rest of Africa or served in airlines and luxury hotels.

The slump from 2008 to 2009 mainly affected the export markets. France's share rose again to 61.7%. 24.1% went to the European Union and 14.2% to the rest of the world.

Champagne in times of climate change

Due to climate change , the wine growing limits have shifted significantly to the north. Before the onset of man-made climate change, Champagne was still ideally suited for the production of champagne, but it is now far too far south, too warm and too dry. The plants grow and mature too early in order to optimally protect them against spring frost. The harvest time is also set earlier. The consequences of this change are a falling acidity and thus a lower freshness of the base wine. As a move to more suitable growing areas, such as the United Kingdom or Scandinavia, is ruled out due to the protected designation of origin, adjustments to production are necessary. For example, producers have started to store champagne in magnum bottles with natural corks, to cover floors with straw, to experiment with other types of wine and yeast, or to switch to malolactic fermentation . Nevertheless, it can be assumed that due to climate change around 2070 it will no longer be possible to cultivate champagne in Champagne.

Champagne grapes as a commodity

The big champagne houses only own about 10% of the area under cultivation of champagne, but represent two thirds of the sales volume. They therefore have to buy in most of their grapes. These come from the more than 14,000 winegrowers in Champagne, some of whom have less than one hectare of vineyards and some of whom only produce grapes as a part-time job . During the harvest at the beginning of October, the champagne houses or one of the winegrowers' cooperatives buy the grapes from the small vintners. Until 1999, the grape prices were determined according to a fixed scheme: the courtiers negotiated a target price per kilogram, which was around 30% of the price of a bottle of champagne. Depending on the quality potential of his vineyards, the winemaker received a fixed percentage of the target price for the grapes. This classification of the locations was based on empirical values and was set down in writing for the first time after the unrest of 1911. 100% was only paid for grapes from the highest ranked communities, the so-called Grands Crus . The scale originally started at 22.5%, the initial value was increased several times to finally 80%. In 1999, however, this procedure was suspended, which resulted in a further increase in grape prices. In 2006, one kilogram of Grand Crus grapes cost € 6.20 compared to € 4 in 2000. In 2006, grapes from average locations were traded between € 4.50 and € 5 per kg. Due to the high demand for champagne, the winegrowers are currently holding the more leverage. The big champagne houses are responding by increasingly buying up vineyards. In the meantime, the price for one hectare of Grand Cru has passed the one million euro mark.

Trademark protection

Due to EU trademark law, sparkling wine made in Germany cannot be called champagne in bottle fermentation, as this is linked to the origin of the grapes. The same applies to all sparkling wines worldwide.

Until the beginning of the 1990s, at least the expression méthode champenoise was allowed on the label of a sparkling wine with bottle fermentation, since then any expression reminiscent of champagne has been banned. The crémant category was therefore introduced in France .

The European Court of Justice in Luxembourg (ECJ) recently had to deal with whether this should also apply to still wines from the Swiss town of Champagne (case T-212/02 of the ECJ). A quality judgment is not connected with this. The vintners there have previously called their still wine Vin de Champagne. The wine had to be renamed Libre-Champ due to the judgment .

For the same reason, a bakery in the same place has now had legal disputes with French winegrowers. The aperitif pastry "Flûte de Champagne", which has been produced under this name since 1934 and in France under the name "Recette de Champagne" (= recipe from Champagne ). distributed, would dilute the designation of origin of the wine.

Even the sparkling wine manufacturer Schlumberger from Austria is no longer allowed to advertise that its sparkling wine is produced using the champagne method, and now has to label the labels with “ Méthode traditionnelle ”.

In 2002 the Federal Court of Justice made it clear that even the mere reference to the quality generally attributed to champagne to advertise completely different items infringes the trademark rights of the champagne manufacturers. An electronics wholesale market had advertised its goods with the slogan "get champagne, pay for sparkling wine".

"Champagne" is the slang term for sparkling wines in general, ie for sparkling wine and champagne.

Champagne in Germany

According to the German Wine Institute, 9.2 million liters of champagne were imported from France in 2018 . This is a decrease of 4.1% compared to the previous year. The demand for champagne is significantly lower today than it was in the 1990s. Champagne imports peaked in 1997 at 13.6 million liters.

Champagne brands

Larger winemakers, cooperatives or champagne houses usually offer several varieties, usually dosed as Brut or Demi Sec and filled in different bottle formats. Many small winemakers leave their grapes for the production of champagne to the cooperatives, but do not want to do without their own champagne brand. The cooperatives produce different types of champagne, which all grape suppliers try at a tasting. The winemakers then buy a champagne of their choice from the cooperative and market it under their own name. Therefore, only a few large companies are behind the more than 15,000 different types of champagne. There are abbreviations on the label that draw attention to the respective origin:

- NM: Negociant manipulative. Trading company that develops and markets champagne itself. As a rule, the trading houses have their own vineyards, but buy a considerable amount of grape material.

- RM: Récoltant manipulative. This is the name given to the small wineries that grow and market champagne (their own grape material) themselves.

- CM: Cooperative de manipulation. Cooperative that develops and markets the grapes of its members.

- RC: Récoltant coopérateur. A winemaker who leaves his grape material to a cooperative for expansion and receives his own bottles back for the purpose of marketing his own champagne brand.

- ND: Negociant distributer. Trading company that buys finished champagne and sells it under its own brand.

- MA: Marque d'acheteur. Bulk buyer who asks a trading house to label the champagne with its own brand. As a rule, these are not simple qualities, but the trading company's second brand. MA is also often referred to as maison auxilliar .

The label of a champagne

The label of the champagne bottle (étiquette) contains the most important, for the most part legally required and regularly checked minimum information, in particular:

- "Champagne": this abbreviation also enjoys the legal trademark protection of the AOC,

- Brand name and address of the manufacturer (winemaker, cooperative or champagne house),

- Bottle content (nominal volume), e.g. B. 0.75 L as well

- Alcohol content (titre alcoométrique volumique) usually 12% by volume.

The following can also be noted on the label:

- Sugar content through the names brut (really dry), dry or sec as well as demi-sec (rather sweet) and so on,

- tradition: frequently used term for champagne of standard quality,

- cuvée: made only from wines of the first pressing,

- réserve: Champagne that has been mixed with older vintages from the same location, usually a term for a higher quality level

- cuvée prestige or cuvée spéciale: top product from this manufacturer,

- millésime: with the indication of the harvest year,

- blanc de blancs: made exclusively from white Chardonnay grapes,

- blanc de noirs: made only from red grapes (Pinot Noir or Pinot Meunier),

- rosé: champagne made from rosé base wines,

- Grand Cru or Premier Cru , if the requirements are met.

Some manufacturers also provide the champagne bottles with a label on the back (contre-étiquette) to indicate which grape varieties have been used, on which day it was disgorged or which dishes this champagne goes well with.

The main champagne houses and their prestige champagnes

| House | founding year | place | Cuvée de prestige | Vintages | group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henri Abelé | 1757 | Reims | Sourire de Reims |

- | Freixenet Spain |

| Alfred Gratien | 1864 | Epernay | Cuvée Paradis | Yes | Henkell & Co. Sektkellerei KG |

| AR Lenoble | 1920 | Damery | Cuvée Gentilhomme Cuvée Les Aventures |

yes no |

independently |

| Ayala | 1860 | Aÿ | Grande Cuvée | Yes | Bollinger |

| Bauget-Jouette | 1822 | Epernay | Cuvée Jouette / |

No | Family-run house with approx. 150,000 bottles p. a. |

| Beaumet / Jeanmaire | 1878 | Epernay | Cuvée Malakoff / Cuvée Elysée |

Yes | Laurent-Perrier |

| Beaumont des Crayères | 1953 | Mardeuil | nostalgia | year-dependent | Cooperative with 240 affiliated winemakers |

| Better Council de Bellefon | 1843 | Epernay | Cuvée des Moines | - | Groupe Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Billecart Salmon | 1818 | Mareuil-sur-Ay | Grande Cuvée | Yes | independently |

| Binet | 1849 | Rilly-la-Montagne | Cuvée Sélection | Yes | Groupe Binet, Prin et Collery |

| Château de Bligny | 1911 | Bligny (Aube) | Cuvée year 2000 | Yes | Groupe G. H. Martel & Co. |

| Chartogne Taillet | 1515 | Reims | Fiacre | Yes | independently |

| Henri Blin et Cie | 1947 | Vincelles | Cuvée year 2000 | Yes | Cooperative with 31 affiliated winemakers |

| Bollinger | 1829 | Aÿ | Vieilles Vignes Françaises | Yes | independently |

| La Grande Année, (R. D. - Récemment Dégorgé, is the name for the "Œnothèque" by Bollinger, the coronation of the Grande Année) | Yes | ||||

| Boizel | 1834 | Epernay | Joyau de France | Yes | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Ferdinand Bonnet | 1922 | Ogre | - | - | Groupe Rémy Cointreau |

| Raymond Boulard | 1952 | La-Neuville-aux-Larris | Vieilles Vignes | - | independently |

| Canard-Duchêne | 1868 | Ludes | Grande Cuvée Charles VII | - | Alain Thiénot |

| De Castellane | 1895 | Epernay | Commodore | Yes | Laurent-Perrier |

| Cattier | 1918 | Chigny-les-Roses | Clos du Moulin / Armand de Brignac |

- | independently |

| Charles de Cazanove | 1811 | Reims | Stradivarius | - | Groupe Rapeneau |

| Chanoine Frères | 1730 | Reims | gamme Tsarine |

year-dependent | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Deutz | 1838 | Aÿ | Amour de Deutz, Cuvée William Deutz | Yes | Louis Rœderer |

| Drappier | 1808 | Urville | Grande Sendrée | Yes | family business |

| Duval-Leroy | 1859 | Vertus | Femme de Champagne | year-dependent | independently |

| Gauthier | 1858 | Epernay | Grande Réserve Brut | - | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Paul Goerg | 1950 | Vertus | Cuvée Lady C. | Yes | - |

| Gosset | 1584 | Aÿ | Celebris | Yes | Rémy Cointreau |

| Heidsieck & Co. monopoly | 1785 | Epernay | Diamond Bleu | Yes | Vranken-Pommery Monopoly |

| Charles Heidsieck | 1851 | Reims | Blanc des Millénaires | Yes | Rémy Cointreau |

| Henriot | 1808 | Reims | Cuvée des Enchanteleurs | Yes | independently |

| jug | 1843 | Reims | Name depends on the year | Yes | LVMH |

| Clos du Mesnil, Clos d'Ambonnay | year-dependent | ||||

| Charles Lafitte | 1848 | Epernay | Orgueil de France | year-dependent | Vranken-Pommery Monopoly |

| Lanson Pere & Fils | 1760 | Reims | Noble Cuvée | Yes | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Larmandier-Bernier | 1956 | Vertus | Vieille Vigne de Cramant | Yes | Family-run champagne house |

| Laurent-Perrier | 1812 | Tours-sur-Marne | Grand Siècle "La Cuvée" | - | Laurent-Perrier |

| Mercier | 1858 | Epernay | Vendange | Yes | LVMH |

| Moët & Chandon | 1743 | Epernay | Dom Pérignon | Yes | LVMH |

| GH guts | 1827 | Reims | Mumm de Cramant | - | Pernod-Ricard |

| Bruno Paillard | 1981 | Reims | NPU (Nec Plus Ultra) | Yes | independently |

| Perrier-Jouët | 1811 | Epernay | Belle Époque | Yes | Pernod-Ricard |

| Philipponnat | 1910 | Mareuil-sur-Ay | Clos des Goisses | year-dependent | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Piper-Heidsieck | 1785 | Reims | Rare | - | Rémy Cointreau |

| Pommery | 1836 | Reims | Cuvée Louise | Yes | Vranken-Pommery Monopoly |

| Robert Moncuit | 1889 | Le Mesnil-sur-Oger | Cuvée réservée brut, Cuvée réservée extra brut, Grande Cuvée Grand Cru Blanc de Blancs | No | independently |

| Louis Rœderer | 1776 | Reims | Cristal | Yes | independently |

| Pol Roger | 1849 | Epernay | Winston Churchill | Yes | independently |

| Ruinart | 1729 oldest still active manufacturer |

Reims | Dom Ruinart | Yes | LVMH |

| salon | 1921 | Le Mesnil-sur-Oger | S. | Yes | Laurent-Perrier |

| Marie Stuart | 1867 | Reims | Cuvée de la Sommelière | - | Alain Thiénot |

| Brut Millésimé | Yes | ||||

| Taittinger | 1734 | Reims | Comtes de Champagne | Yes | Taittinger |

| Thiénot | 1985 | Reims | Grande Cuvée | Yes | Alain Thiénot |

| Cuvée Stanislas | - | ||||

| de Venoge | 1837 | Epernay | Grand Vin des Princes | Yes | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin | 1772 | Reims | La Grande Dame | Yes | LVMH |

| Vranken | 1979 | Epernay | Demoiselle followed by a year-dependent name |

year-dependent | Vranken-Pommery Monopoly |

literature

- Peter von Becker: A votre santé! In: Der Tagesspiegel. December 29, 2007, p. 27.

- Michael Brückner: Pocket Guide Champagne. Gentlemen's Digest, Berlin 2005.

- Frederique Crestin-Billet, Dominique Pascal: Champagne. Moewig, Rastatt 2001, ISBN 3-8118-1708-6 .

- Don and Petie Kladstrup: champagne. The dramatic story of the noblest of all drinks. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-608-94446-4 .

- Klaus Rädle: Champagne: facts, data, background. Pro Business, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86805-327-2 .

- Tom Stevenson: Champagne. Gräfe and Unzer, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7742-5044-8 .

- Serena Sutcliffe: Great Champagnes. Hallwag, Bern / Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-444-10359-X .

Web links

- Official website of the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne (French)

- Website of the Union des Maisons de Champagne in Reims (French)

- Website of the Syndicat Général des Vignerons de la Champagne in Epernay (French)

- Champagne world - large database of champagne houses

Individual evidence

- ↑ 1936 Recognition of the protected designation of origin

- ↑ décret du 29 juin 1936 modified relatif à l'appellation d'origine contrôlée "Champagne"

- ↑ a b c d e Antoine Gerbelle: Champagne: extension du domaine de la bulle. In: La Revue du vin de France. No. 521, May 2008, p. 13.

- ↑ Appendix to the Ordinance on the AOC Champagne Décret n ° 2010-1441 on November 22nd, 2010 relatif à l'appellation d'origine contrôlée “Champagne”. Legifrance website, Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ↑ Kessler Piccolos: WZ. 480 371. Registered with the Reich Patent Office on November 18, 1935.

- ↑ Bottles with contents and pictures

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) The bottle sizes available at Armand de Brignac.

- ^ The Added Sparkle Of Champagne In Large Bottles. In: New York Times. December 23, 1987, Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ↑ Guy Renvoisé: Le monde du vin at-il perdu la raison? Editions du Rouergue, Rodez 2004, p. 270 f.

- ↑ Bruno Duteurtre: Le champagne - de la tradition à la science. Lavoisier Group, 2010, ISBN 978-2-7430-1920-4 , p. 3 arrêté royal du 25 may 1728

- ^ Quote from the Berliner Zeitung. 25./26. May 2013, magazine, p. 11:

- ↑ Luxembourg champagne production (PDF; 1.2 MB)

- ^ Jean-François Arnaud: Les salariés de Taittinger hostiles au candidat india. In: Le Figaro . May 26, 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ EXPEDITIONS DE CHAMPAGNE 2008. ( Memento from January 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Press release of the Comité interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne from February 2009.

- ↑ a b le champagne a bien terminé l'année 2009. ( Memento from January 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Press release of the Comité interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne from February 2010

- ↑ Probably the oldest champagne in the world discovered. In: Spiegel-online. July 17, 2010.

- ↑ Champagne found in the Baltic Sea is not a Veuve Clicquot. In: Premium champagne. August 8, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Champagne - facts, tests & recommendations

- ↑ Thomas Wyss: The champagne industry is in a festive mood. In: Finance and Economy . No. 40 of May 21, 2008.

- ↑ Les expéditions de vins de champagne en 2014. Press release of the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne from 2014, p. 43, accessed on July 24, 2016 (French)

- ↑ Bratic, Z. (2018). Climate change is affecting champagne production. Der Standard, August 8, 2018. https://derstandard.at/2000084987081/Klimawandel-setzt-Champagner-Produktion-zu

- ↑ Meister, M. (2017). Is champagne coming from England soon? Welt, July 19, 2017. https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/plus166763491/Kommt-Champagner-bald-aus-England.html

- ↑ Les Courtiers en Vins de Champagne ( Memento of February 14, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (French)

- ↑ Weinmarkt 2018. (PDF) In: German Wine Statistics '19 / '20. deutscheweine.de, accessed on January 1, 2020 .

- ^ German Wine Institute : Statistics 2008/2009 . Mainz 2008 ( deutscheweine.de ( memento from March 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 454 kB ]).