absinthe

Absinthe , also called absinthe or wormwood spirit , is an alcoholic drink that is traditionally made from wormwood , anise , fennel , a range of other herbs and alcohol, which vary depending on the recipe .

Most absinthe brands are green, which is why absinthe is also called "The Green Fairy" ( French La fée verte ). The alcohol content is usually between 45 and 89 percent by volume and is therefore in the upper range of spirits . Due to the use of bitter-tasting herbs, especially wormwood, absinthe is considered a bitter spirit , although it does not necessarily taste bitter.

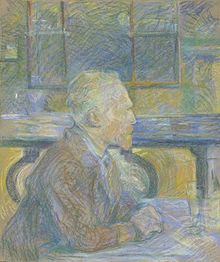

Absinthe was originally produced as a medicinal product in the 18th century in the Val de Travers in today's Swiss canton of Neuchâtel ( République et Canton de Neuchâtel ). This spirit, which is traditionally drunk mixed with water, found great popularity in France in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Famous absinthe drinkers include Charles Baudelaire , Paul Gauguin , Vincent van Gogh , Ernest Hemingway , Edgar Allan Poe , Arthur Rimbaud , Aleister Crowley , Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Oscar Wilde .

At the height of its popularity, the drink had a reputation for being addictive due to its thujone content and causing serious health problems. In 1915 the drink was banned in a number of European countries and the USA. Modern studies have not been able to prove any damage caused by absinthe consumption beyond the effects of alcohol; the damage to health found at the time is now attributed to the poor quality of the alcohol and the high amounts of alcohol consumed. Absinthe has been available again in most European countries since 1998. In Switzerland, too, the production and sale of absinthe has been permitted again since 2005.

ingredients

Used herbs

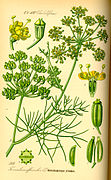

Besides wormwood ( Artemisia absinthium ), absinthe produced in France and Switzerland contains anise, partially replaced by the cheaper star anise , fennel, hyssop , lemon balm and Pontic wormwood . Variants also use angelica , calamus , origanum dictamnus , coriander , veronica , juniper , nutmeg and various other herbs. Vermouth, anise and fennel make up the typical taste of absinthe. The other spices serve to round off the taste. The green color that many types of absinthe have comes from the chlorophyll in Pontic wormwood, hyssop, lemon balm and mint.

Thujone

Thujone is a component of the essential oil of wormwood, which is used to make absinthe. The harmful effects seen during the height of absinthe popularity in France in the 19th century, including dizziness , hallucinations , delusions , depression , convulsions , blindness, and mental and physical decline, have been attributed to this substance. Thujone is a neurotoxin which, in higher doses , can cause confusion and epileptic cramps ( convulsions ). For this reason, the thujone content in alcoholic beverages has been limited in the European Union (5 mg / kg in alcoholic beverages with an alcohol content of up to 25% vol. And up to 10 mg / kg in alcoholic beverages with an alcohol content of more than 25% vol. and up to 35 mg / kg in bitter spirits.)

The observed in particular in animal experiments of the 19th century convulsive effect of absinthium is today a blockage of GABA A receptors and desensitization of serotonin - 5HT 3 receptors recycled through thujone. However, it has now been refuted that the amount of thujone contained in absinthe is sufficient to have a pharmacodynamic effect to this extent. The alcohol contained in absinthe is more likely to be the cause or major factor. A possible common mechanism of action with the cannabis active ingredient tetrahydrocannabinol via an activation of cannabinoid receptors could not be confirmed either. A euphoric and aphrodisiac effect of today's absinthes, which has been proclaimed in the club scene and in the media, cannot be traced back to the dose of thujone contained in these beverages on the basis of these experimental data.

The absinthe of the 19th century, contrary to earlier reports, which spoke of up to 350 milligrams per liter, essentially had no higher thujone content than today's regulated absinthe. In a study of absinthe based on historical recipes and processes and absinthe produced in 1930, only thujone quantities of less than 10 mg / kg could be detected. The thujone content can, however, be higher if wormwood extracts or wormwood oils are added. The absinthes become very bitter this way.

alcohol

The alcohol content of historical absinthes was between 45 and 78%. With a few exceptions, this area also includes the types of absinthe available today. Absinthe is also available with an alcohol content of up to 90%. Because of the high alcohol content, absinthe is usually drunk diluted.

There are historical records of five quality grades : Absinthe des essences (German absinthe extracts), Absinthe ordinaire (German ordinary absinthe), Absinthe demi-fine (German absinthe semi-fine), Absinthe fine (German absinthe fine) and Absinthe Suisse (Eng. Swiss absinthe), whereby absinthe des essences represents the lowest alcohol content and the lowest quality. Absinthe Suisse does not refer to the country of manufacture, but to a particularly high alcohol content and high quality.

In retrospect, today it is no longer thujone, but rather the alcohol content of absinthe that is considered to be the main cause of absinthism that was widespread in the 19th and early 20th centuries . In 1914, the pure amount of alcohol consumed per capita by French adults was 30 liters per year. In comparison, today (2013, according to WHO) Moldova leads the statistics of alcohol consumption worldwide with 18.22 liters of pure alcohol per adult. The symptoms of absinthism are no different from those of chronic alcohol abuse ( alcoholism ).

Other ingredients

An additional problem with 19th century absinthe was that the alcohol used was often poor quality and contained a lot of amyl alcohol and other fusel oils . Also methanol , the dizziness, headaches and nausea caused and as a late consequence of blindness, palsy draws or an overdose of the fatality was contained in the former absinthe. In order to give absinthe its characteristic color, additives such as aniline green , copper sulfate , copper acetate and indigo were sometimes added. It has also been antimony added to the ouzo effect (when diluted with water or is very strongly cooled, the milky haze of the otherwise clear beverage) cause. However, the concentrations of potential pollutants found in historical samples, such as pinocamphone , fenchone , alcohol impurities, copper and antimony ions, were in an unsuspicious range for conclusions about absinthism.

Manufacturing

During production, wormwood, anise and fennel are macerated (soaked) in neutral alcohol or wine alcohol and then distilled . The distillation helps to separate the strong bitter substances in wormwood. These are less volatile than the flavoring substances and are left behind during the distillation. Otherwise the result would be unpleasant to inedible bitter. A disproportionate bitterness in absinthe can be an indication that the distillation was completely or partially dispensed with in production, that wormwood extracts were used in the production and that it could be inferior or fake absinthe.

The distillate can be colored with herbs such as Pontic wormwood, lemon balm and hyssop. The coloring by herbs contributes to the overall taste of the end product. It places high demands on the skills of the manufacturer in the selection of the coloring herbs, their quantitative ratio and the duration of the coloring. In the case of old absinthe, the color of the drink can change from an originally bright green to a yellowish green or brown, as the chlorophyll decomposes. Very old absinthes are occasionally amber in color. Clear absinthe, also known as “Blanche” or “La Bleue”, is typical of the absinthe produced in illegal distilleries in Switzerland. The fact that absinthe was not colored normally made it easier to sell it secretly in times when absinthe was banned in Switzerland.

Today absinthe is often made by adding absinthe essence to high-proof alcohol. Classical production methods such as maceration are only used from the upper middle class . Some of the absinthes made today are colored with food coloring. It is also mostly about inferior absinthe with a simplified production process, which robs absinthe of important taste nuances . In addition to the “green fairy”, there is also red, black or blue colored absinthe. This coloring, which is unusual for absinthe, is mainly for marketing reasons.

history

origin of the name

"Absinthe" is the Germanization of the French absinthe , which originally meant "wormwood". It goes back from Latin absinthium to ancient Greek ἀψίνθιον apsinthion , which also referred to wormwood.

Wormwood as a remedy

Wormwood belongs to the genus Artemisia (mugwort), whose representatives grow in the temperate climates of the northern hemisphere. Many species of these fragrant and often insect repellent plants have a long tradition as medicinal plants. References to the use of mugwort species for healing purposes can already be found in the Ebers papyrus , which contains texts from the period from 3550 to 1550 BC. The Old Testament also refers in several places to the bitterness of the Artemisia herbs. In German editions, the plants are usually translated as "wormwood", although they are other species of the genus Artemisia . In 2007, German researchers found in a double-blind study that wormwood brought about a "significant improvement" in patients with Crohn's disease .

The use of Artemisia herbs in tinctures and extracts is important for the creation of absinthe . It is already mentioned by Theophrast and Hippocrates . Hildegard von Bingen recommended decoctions of wormwood in wine as a de- wormer . Vermouth wines, in which wormwood leaves are fermented together with grapes, are documented for the 16th century. They had a reputation for being particularly effective gastric remedies.

The origin of absinthe

The recipe for absinthe was created in the second half of the 18th century in Val-de-Travers in what is now the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel (Neuchâtel). In this area, the consumption of wine to which vermouth was added is documented from 1737. While the original place of manufacture is secured, different people are named as the originators of the original recipe depending on the source. The French doctor, who fled to the Prussian principality for political reasons, Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, who practiced as a country doctor in Couvet , is said to have used a self-made "élixir d'absinthe" on his patients. After his death, the recipe came to the Henriod family, also based in Couvet, who declared it as a medicinal product and sold it through pharmacies. According to other sources, an absinthe elixir had been made in the Henriod family for a long time - a wormwood elixir was distilled by a Henriette Henriod as early as the middle of the 18th century. Suzanne-Marguerite Motta, who is married to the innkeeper Henry-Francois Henriod, known as "Mother Henriod", is also named as the originator of the original recipe. In his history of absinthe, Helmut Werner put forward the thesis that Pierre Ordinaire, based on his medical experience, merely optimized the manufacturing process of a family recipe from the Henriod family and designed it for larger quantities.

It is certain that in 1797 a Major Dubied acquired the recipe from a member of the Henriod family and founded an absinthe distillery with his son Marcellin and his son-in-law Henri Louis Pernod . Initially only 16 liters a day were produced, and most of the production went to nearby France. To avoid the cumbersome customs formalities, Henri Louis Pernod relocated the distillery to Pontarlier, France, in 1805 and initially produced 400 liters a day there. Its success led to the creation of a number of other absinthe distilleries both in France and in the Principality of Neuchâtel.

Use of absinthe by military doctors

In 1830 France occupied Algeria . The inadequate sanitary facilities regularly led to epidemics among French soldiers, who were fought by military doctors with a mixture of wine, water and absinthe. The first ships that crossed to Algeria already had barrels of absinthe on board. The soldiers were given absinthrations every day in the hope of combating both the effects of poor drinking water and malaria . This had a clear impact on absinthe production. The Pernod company increased its production to 20,000 liters a day, and its competitor Berger founded an absinthe distillery near Marseille to shorten the transport routes to Algeria.

Soldiers returning from Algeria made absinthe known throughout France. The drink became particularly popular in Paris, where those returning from the war regularly enjoyed absinthe in the cafes in the late afternoon.

Changed drinking habits and the success of absinthe

The “green hour”, the “heure verte”, was already established in everyday life in French metropolises around 1860. Drinking absinthe between 5 and 7 p.m. was considered chic. The numerous drinking rituals also contributed to its reputation as a contemporary drink in the late afternoon. There were often tall water containers with several taps on the tables of bars and cafés on Parisian boulevards. An absinthe drinker placed one of the spatula-shaped and perforated or slotted absinthe spoons on his glass and placed a lump of sugar on it. Then he turned on one of the taps on the water container, causing water to drip onto the spoon at a rate of about one drop per second. Every drop of sugared water that fell into the absinthe glass below left a milky trail in the absinthe, until a mixing ratio was reached that gave the drink a milky-greenish color overall.

Marie-Claude Delahaye is considered the historian in France who has dealt most intensively with the history of absinthe. In an interview with Taras Grescoe she pointed out that absinthe was an innovation in French drinking habits in several ways. For the first time, the French drank an alcoholic drink in large quantities, the taste of which was largely determined by herbs and which was diluted with water. Absinthe was at the same time the first high-proof spirit that women who did not belong to the demi-world could consume in public. Absinthe had already established itself as a bohemian drink by the middle of the 19th century .

Absinthe was a relatively cheap drink that remained cheaper than wine even after taxation by the French government. It could also be produced with cheap alcohol from sugar beet or grain, and a single glass of absinthe could buy the right to stay in one of the bars for hours because it was diluted with water. With around three sous per glass, not only artists could afford this drink, but workers too. For many of them it became a habit to stop in one of the bars and drink absinthe after finishing their work. In view of cramped living conditions and a very limited range of leisure activities, stopping at a bar was one of the few entertainment options. This explains why there were 11.5 pubs per 1000 inhabitants in Paris at the turn of the 20th century. In 1912 the annual consumption of absinthe in France was 221.9 million liters.

Absinthe as a drink for artists and writers

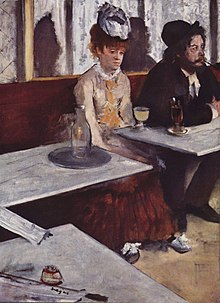

Absinthe enjoyment is still associated with the French art scene of that time. Hannes Bertschi and Marcus Reckewitz write : "It seems as if the entire European elite of literature and the visual arts staggered through the late 19th and early 20th centuries in a absinthe intoxication." Lonely, shabby absinthe drinkers were repeatedly motifs in painting at the time and literature. Édouard Manet's painting The Absinthe Drinker , which was created around 1859, caused great offense with the subject of a neglected alcoholic and was rejected by the selection committee of the Paris Salon . The literary model for the painting was a poem by Charles Baudelaire , who himself consumed absinthe in large quantities and thus tried to combat the pain and dizziness caused by syphilis . Other early representations are the caricatures Le premier verre, le sixième verre by Honoré Daumier and L'Èclipse by André Gill . Edgar Degas ' painting The Absinthe from 1876 shows a couple who are no longer aware of each other and sitting apathetically next to each other in one of the French bars.

In addition to Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley , Henri Toulouse-Lautrec was one of the well-known absinthe drinkers, who portrayed his painter colleague Vincent van Gogh in a café with a glass of absinthe in 1887. In the same year he created his still life with absinthe . Evidence for the spread of the drink outside of Paris is his painting Night Café on Place Lamartine , made in Arles , which, like Paul Gauguin's Dans un café à Arles, shows bar-goers drinking absinthe. At the beginning of the 20th century, Pablo Picasso repeatedly chose absinthe drinkers as a motif. In addition to various pictures from his Blue Period , such as Buveuse assoupie from 1902, the cubist painting Das Glas Absinthe was created in 1911 and a sculpture with the same title in 1914. The pictures The Absinthe Drinker by the Czech painter Viktor Oliva and The Absinthe Drinker by the Irish artist William Orpen also date from this period .

Examples of absinthe in literature are À Rebours by Joris-Karl Huysmans , Lendemain by Charles Cros and Comédie de la Soif by Arthur Rimbaud . He was shot on July 10, 1873 by his drunken lover Paul Verlaine , possibly due to excessive absinthe consumption. Oscar Wilde described absinthe with the poetic words: “Absinthe has a wonderful color, green. A glass of absinthe is as poetical as anything in the world. ”At the same time, he pointed out:“ After the first glass, you see things as you would like to see them. [...] In the end you see things as they are, and that is the most horrific thing that can happen. "

Even if the representations in art and literature often explicitly mention absinthe, the paintings and novels reflect the alcohol-related problems of a society in which wine was traditionally consumed and high-proof alcoholic beverages were relatively seldom consumed until the introduction of absinthe. Around 100 years earlier, a surge in the consumption of spirits in Great Britain had created comparable social problems and could only be reduced to more tolerable levels through legal measures.

Absinthe opponent

As early as 1850, worries about the consequences of long-term absinthe consumption were loud. This leads to absinthism . Symptoms were addiction , over-excitability and hallucinations . After Emile Zola's 1877 published novel L'assommoir (dt. The murderers ) to the serious social consequences of alcoholism had drawn attention, had a number of teetotaler associations tried to ban absinthe - variously along with the wine producers. In 1907 4,000 demonstrators took to the streets in Paris under the slogan “Tous pour le vin, contre l'absinthe” (All for wine and against absinthe). In France at the time, wine was considered a healthy drink and staple food. “Absinthe makes criminals, leads to madness, epilepsy and tuberculosis and is responsible for the deaths of thousands of French people. Absinthe turns the man into a wild beast, turns women into martyrs and turns children into debiles, it ruins and destroys families and threatens the future of this country, " Barnaby Conrad quotes the critics of the time in his story of absinthe. Zola, too, in his influential novel, described schnapps as a human-spoiling drink, while wine, on the other hand, was the right of the worker. This view was also supported by medical professionals. Alcoholism was first scientifically described in France in the 1850s. Around 1900, French doctors had found a particularly high number of harmful substances in the cheap absinthe brands that were produced using the cold extraction process. From their point of view, too, absinthe was the first drink that should be banned.

A murder and the ban on absinthe

A spectacular murder case in the Vaudois community of Commugny in August 1905 , which was extensively reported in the media across Europe, was the final impetus to legally ban the production and sale of beverages containing thujone in most European countries and the USA.

The vineyard worker Jean Lanfray was a heavy alcoholic who drank up to five liters of wine a day. On the day he murdered his pregnant wife, his two-year-old daughter Blanche and his four-year-old daughter Rose in a fit of rage, he had consumed wine, brandy and two glasses of absinthe. In the ban debate, in which wine producers also lively participated, the focus was on the consumption of absinthe that had preceded the murder. In Belgium, the incident was used as an opportunity to ban absinthe that same year. In Switzerland, the absinthe ban was incorporated into the constitution in 1910 as a result of a popular initiative in which 63.5 percent of the male population voted in favor on July 5, 1908. The ban came into effect on October 7, 1910. France took its time with the ban until 1914. It can no longer be determined whether the ban on absinthe had a positive effect on French public health. A lack of health statistics and the turning point of the First World War prevent such analyzes.

Today's EU countries that did not join the absinthe ban at the beginning of the 20th century only included Spain and Portugal. Even in Great Britain, where absinthe only had a niche existence in the 19th century, at least the sale was still allowed. The ban on absinthe led to a growing popularity in France of the absinthe substitute pastis , for the production of which no wormwood is used, but which is also enjoyed diluted with water in the afternoon.

Switzerland: underground distilleries

After the French ban, the Pernod company, one of the largest French absinthe producers, initially relocated its absinthe production to Spain, but then concentrated on the production of aniseed schnapps. The Val-de-Travers, on the other hand, the original production area, suffered more from the ban. For more than a century people had lived in the rather poor valley from cultivating wormwood, selling the dried herb and distilling absinthe. After the ban, the Swiss government had the wormwood fields plowed under. The distillation was carried on secretly - the inhabitants of the valley attach importance to being able to refer to a 250-year uninterrupted history of absinthe production.

Interviewees of the author Taras Grescoe estimate the number of distilleries illegally producing absinthe in Val-de-Travers at around sixty to eighty at the beginning of the 21st century. Similar to the illegally distilled Moonshine of the USA, the Norwegian Hjemmebrent or the Irish Poteen , the illegal Swiss absinthe is also surrounded by rich folklore . Berthe Zurbuchen, a celebrity of the Val-de-Travers, who illegally distilled absinthe for eighty years and was sentenced to 3,000 francs in a show trial in the 1960s, is said to have asked her judge after the verdict whether she should pay immediately or first next time he came over to pick up his weekly bottle. After the conviction, she demonstratively painted her house absinthe green. In 1983, on the occasion of a state visit, the French President François Mitterrand was served a soufflé glazed with absinthe . For the restaurant owner, the demonstrative use of illegal absinthe led to a house search and a four-day suspended prison sentence. The representative of the canton, Pierre-André Delachaux, who had suggested the absinthe-glazed soufflé, narrowly escaped a forced resignation from his office and the end of his political career.

From 2001, in addition to illegal absinthe, a legal version of absinthe was also produced in Val-de-Travers. This was possible because the alcohol and thujone content were reduced to such an extent that this product was no longer absinthe by law. Even before absinthe legalization in Switzerland on March 1, 2005, efforts were made to protect absinthe as an intellectual property of the Val-de-Travers under the IGP, the "indication géographique protégée". You are in direct competition with your neighbors on the French side of the border, who are equally trying to get an “appellation d'origine réglementée”. Regardless of who will be successful in this competition, only those products could bear the designation absinthe after being awarded, which come from this region of the Jura and whose production has met certain quality standards.

Absinthe as a fashion drink in the late 1990s

“ If gin and vermouth had been banned instead of absinthe ... collectors today would pay a fortune for old, conical glasses and reverently quote Dorothy Parker and Dashiell Hammett about the narcotic qualities of the infamous martinis . "

This is how Grescoe writes in his essay Absinthe Suisse - One glass and You are Dead . The recipes for home-making absinthe available on the Internet can also be seen as an indication that the ban contributed to the myth of this drink. For other, once popular beverages such as violet or vanilla liqueur, no remotely comparable range of recipes can be found.

The spirit absinthe became widely publicized when an importer specializing in alcoholic beverages noted in the 1990s that there was no specific legislation in the UK banning the sale of absinthe. Hill's Liquere, a Czech distillery, began making Hill's absinthe for the UK market - a drink that Taras Grescoe claims is nothing more than a high-proof vodka colored with food coloring. The beginning of the re-serving of absinthe was accompanied by a series of articles in lifestyle magazines that commented on its popular hallucinogenic and erotic effects, the absinthe ban in many countries, van Gogh's allegedly absinthe- induced self-mutilation and the elaborate drinking rituals. This broad media coverage can also be observed in all other European countries that allowed absinthe to be served again in the following years. Even films took up absinthe as a feature typical of the epoch, for example in 1992 in Bram Stoker's Dracula . 2001 Johnny Depp intoxicated himself in opium and emerald green absinthe in the film From Hell on his hunt for Jack the Ripper . Together, both created a new demand for this drink, which caused importers and distilleries to review country-specific legislation. In the Netherlands, for example, the sale of absinthe has been allowed again since July 2004, after the Amsterdam wine merchant Menno Boorsma successfully sued the ban.

Adjustments to existing laws

Lawsuits against an absinthe ban generally had great prospects of success in the EU, as both Spain and Portugal allowed absinthe production and sale. Some countries, such as Belgium, lifted their absinthe ban with reference to sufficient EU legislation, without being compelled to do so through legal action. In Germany, where not only the production of absinthe but even the distribution of recipes for making it had been banned since 1923, the Absinthe Act expired at the end of 1981, but in fact the legal situation remained almost unchanged, as the Aroma Regulation continued to use wormwood oil and thujone prohibited. A fundamental change came in 1991 when the EU directive, written in 1988, for the approximation of the laws of the member states on flavorings for use in food came into force (88/388 / EEC). From now on, plants and parts of plants containing thujone (e.g. wormwood) as well as aroma extracts from them were permitted subject to the following thujone limit values: 5 mg / l with up to 25 percent alcohol by volume, 10 mg / l with alcohol content above that and 35 mg / l in bitter spirits. In 1999, Switzerland lifted the absinthe ban that was incorporated into the constitution in 1910. In the USA, the ban fell in 2007 with various conditions. In 2011, France lifted the absinthe ban that had been in force since 1915.

Drinking styles and rituals

Similar to the aniseed spirits pastis , rakı or ouzo , absinthe is generally not drunk pure, but diluted with water. The clear liquid becomes opalescent , which means that it becomes cloudy and cloudy. This phenomenon is called the louche effect . The cause of the effect is the poor water solubility of the essential oil anethole contained in absinthe . The various drinking rituals that have developed around absinthe are called the French drinking ritual , the Swiss way of drinking and the Czech or fire ritual . It is common to all of them that absinthe is mixed with ice water in a ratio of 1: 1 to 1: 5. Most absinthe drinkers choose a mixing ratio of at least 1: 3.

The Swiss way of drinking is the least established. With her, only two to four centiliters of absinthe are mixed with cold water. No sugar is used because the absinthes drunk in Switzerland were generally less bitter than the French.

The fire ritual, also known as the Czech way of drinking , is historically not associated with absinthe consumption. It was developed in the 1990s by Czech absinthe producers to make the drink more attractive. To do this, one or two sugar cubes soaked with absinthe are placed on an absinthe spoon and lit. As soon as the sugar caramelises and bubbles, the flames are extinguished and the sugar is only then added to the absinthe. If lumps of sugar still get into the glass, there is a risk that the absinthe inside will ignite. Here, too, the absinthe is mixed with ice water in a ratio of 1: 3 to 1: 5.

The French drinking ritual , on the other hand, has a historically verifiable tradition. Absinthe was enjoyed in this way from the 19th century until it was banned in France at the beginning of the 20th century. Similar to the fire ritual, absinthe is drunk with sugar. To do this, one or two lumps of sugar are placed on an absinthe spoon and cold water is poured or drizzled very slowly over the sugar. The mixing ratio is 1: 3 to 1: 5.

An absinthe fountain or a special glass attachment - the Brouille - can be used to add the water . With a fountain, the sugar on the absinthe spoon is dissolved by a thin stream from the fountain taps. The Brouille, on the other hand, is placed directly on the absinthe glass so that the absinthe is prepared without an absinthe spoon. The water flows through a small hole in the glass attachment into the absinthe glass below.

French absinthe offer at the farmers market in Leichlingen

literature

German

- Jakob Hein, Lars Lobbedey, Klaus-Jürgen Neumärker: Absinthe - New fashion, old problems. (PDF; 836 kB) In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . Vol. 98, issue 42, October 19, 2001, ISSN 0172-2107 .

- Hannes Bertschi, Marcus Reckewitz : From absinthe to zabaione. Argon, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-87024-559-X .

- Erika Büttner: The green fairy absinthe. A legend lives on. Buchverlag für die Frau, Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-89798-001-0 .

- Alexander Kupfer: Divine Poisons. A short cultural history of intoxication since the Garden of Eden. Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01409-6 (extensive chapter on absinthe in the chapter: literature and art ).

- M. Lang, C. Fauhl, R. Wittkowski (eds.): Stress situation of absinthe with thujone. In: BgVV booklets . 08/2002. Federal Institute for Consumer Health Protection and Veterinary Medicine , Berlin 2002 (available from the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment : Absinthe fashion drink: BfR advises caution when consuming it! ).

- Helmut Werner: Absinthe . The green wonder drug. Ullstein-Taschenbuch 36373, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-548-36373-3 .

- Tobias Otto, Joachim Deiml: The effect of the neurotropic absinthe active ingredient a-thujone (alpha-thujone) on the 5-HT_1tn3 receptor. Dissertation at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . Munich 2003.

- Michael Erdmann, Heiko Antoniewicz: Cooking culture with absinthe. Klartext, Essen 2003, ISBN 3-89861-167-1 .

- Peter Schmersahl: Absinthe - the green fairy. The fashion drink of the artists of Montmartre. In: Deutsche Apotheker-Zeitung . 144, 5893, Stuttgart 2004, ISSN 0011-9857 .

- Diana Nitsche: Absinthe. Medical and cultural history of a pleasure drug. Dissertation at the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University . Heidelberg 2005.

- Mathias Broeckers , Chris Heidrich, Roger Liggenstorfer: Absinthe - The return of the green fairy. Stories and legends of a cult drink. Nachtschatten Verlag, Solothurn 2007, ISBN 978-3-03788-151-4 ( excerpt ( memento from June 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive )).

- Dirk W. Lachenmeier, Joachim Emmert, T. Kuballa, G. Sartor: Thujon - Cause of Absinthism? (PDF; 64 kB), study by the Chemical and Veterinary Investigation Office (CVUA) Karlsruhe and Fluka Production GmbH , Buchs SG [no year].

English

- Barnaby Conrad: Absinthe: History in a Bottle. Chronicle Books, San Francisco 1997 (Reprint), ISBN 0-8118-1650-8 .

- Phil Baker: The Dedalus Book of Absinthe. Dedalus Concept Books, Sawtry 2001, ISBN 1-873982-94-1 .

- Taras Grescoe: The Devil's Picnic - A Tour of everything the governments of the world don't want you to try. Pan Macmillan, London 2006, ISBN 0-330-43151-X .

- David Nathan-Maister: The Absinthe Encyclopedia - A Guide To The Lost World Of Absinthe And La Fée Verte. Oxygenee Press, [no location] 2009, ISBN 978-0-9556921-1-6 .

French

- Marie-Claude Delahaye, Benoît Noël: Absinthe, muse des peintres. Éditions de l'Amateur, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-85917-286-6 .

- Marie-Claude Delahaye: L'absinthe - Son histoire . le Musée de l'absinthe, Auvers-sur-Oise 2000, ISBN 2-9515316-2-1 .

- Marie-Claude Delahaye: L'absinthe, muse des poètes . le Musée de l'absinthe, Auvers-sur-Oise 2000, ISBN 2-9515316-0-5 .

- Marie-Claude Delahaye: L'Absinthe Les Cuillères. le Musée de l'absinthe, Auvers-sur-Oise 2001, ISBN 2-9515316-1-3 .

- Benoît Noël: L'Absinthe, un mythe toujours vert. Esprit frappeur, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-84405-094-8 .

- Benoît Noël: L'absinthe, une fée franco-suisse. Cabédita, Yens sur Morges 2001, ISBN 2-88295-313-5 .

Web links

- Fashion drink absinthe - BfR advises caution when consuming it! , Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR), July 2, 2003

- Absinthe effect. The “green fairy” is disenchanted , Spiegel Online , April 30, 2008

- The Virtual Absinthe Museum (English)

- Absinthe in the database of Swiss culinary heritage (French)

- Rolf Trechsel: Absinthe. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Flavor Ordinance (Article 22 of the Ordinance on the Reorganization of Food Labeling Regulations) of the Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection.

- ↑ KM Hold, NS Sirisoma, T. Ikeda, T. Narahashi, JE Casida: Alpha-thujone (the active component of absinthe): gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor modulation and metabolic detoxification. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . 97, 2000, pp. 3826-3831.

- ↑ T. Deiml, R. Haseneder, W. Zieglgänsberger, G. Rammes, B. Eisensamer, R. Rupprecht, G. Hapfelmeier: α-Thujone reduces 5-HT3 receptor activity by an effect on the agonist-reduced desensitization. In: Neuropharmacology . 46, 2004, pp. 192-201.

- ↑ a b Dirk W. Lachenmeier, David Nathan-Maister, Theodore A. Breaux, Eva-Maria Sohnius, Kerstin Schoeberl, Thomas Kuballa: Chemical Composition of Vintage Preban Absinthe with Special Reference to Thujone, Fenchone, Pinocamphone, Methanol, Copper, and Antimony Concentrations. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . 56, 2008, pp. 3073-3081, doi: 10.1021 / jf703568f .

- ↑ RW Olsen: Absinthe and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97, 2000, pp. 4417-4418.

- ↑ JP Meschler, AC Howlett: Thujone exhibits low affinity for cannabinoid receptors but fails to evoke cannabimimetic responses. In: Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior . 62, 1999, pp. 473-480.

- ^ DW Lachenmeier, J. Emmert, T. Kuballa, G. Sartor: Thujone - cause of absinthism? In: Forensic Science International. 158, 2006, pp. 1-8, PMID 15896935 .

- ↑ Production methods of absinthe .

- ↑ Y. Chapuis: Absinthe rehabilitated. In: Bulletin de l'Académie nationale de Médecine. 197, No. 2, February 2013, pp. 515-521, PMID 24919378 .

- ↑ a b S. A. Padosch, DW Lachenmeier, LU Kröner: Absinthism: a fictitious 19th century syndrome with present impact. In: Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 1, 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Werner: Absinthe. P. 122 f.

- ↑ Anonymous: Absinthe: A lot of alcohol, no psychedelic effects. In: Ärzteblatt. May 2, 2008, accessed May 15, 2020 .

- ↑ Published in: Münchner Medizinische Wochenschrift . Issue 33–34, year 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ a b Bertschi: From absinthe to zabaione. P. 16.

- ↑ Werner: Absinthe. P. 41.

- ↑ Grescoe: The Devil's Picnic. Pp. 199-202.

- ^ Conrad: Absinthe: History in a Bottle. P. 6.

- ^ Bertschi: From Absinthe to Zabaione. P. 7.

- ^ Conrad: Absinthe: History in a Bottle. P. 36.

- ^ A b Peter Dittmar: This potion makes women willing, men weak . In: Die Welt , January 11, 2015, accessed on May 18, 2016.

- ↑ Copper: Divine Poisons. P. 341.

- ^ Bertschi: From Absinthe to Zabaione. P. 15.

- ↑ Nationwide and cantonal results of the referendum on the federal popular initiative 'For a ban on absinthe' ( chronological overview ), published by the Federal Chancellery , accessed on May 18, 2016.

- ↑ Grescoe: The Devil's Picnic. P. 212.

- ↑ a b Grescoe: The Devil's Picnic. P. 216.

- ↑ Grescoe: The Devil's Picnic. P. 221.

- ↑ Werner: Absinthe. P. 10

- ↑ Parliamentary initiative to lift the absinthe ban in law , published on parlament.ch, accessed on May 18, 2016.

- ↑ Grescoe: The Devil's Picnic. P. 197.

- ↑ Directive of the Council on the approximation of the laws of the member states on flavorings for use in food. (PDF) In: PDF document. P. 11 (Thujon) , accessed on July 16, 2018 .