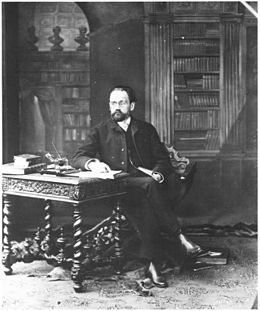

Emile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (born April 2, 1840 in Paris , † September 29, 1902 in Paris) was a French writer , painter and journalist .

Zola is considered one of the great French novelists of the 19th century and a leading figure and founder of the pan-European literary movement of naturalism . At the same time he was a very active journalist who took part in political life in a moderately left-wing position.

His article J'accuse…! ("I accuse ...!") Played a key role in the Dreyfus affair , which kept France in suspense for years, and made a decisive contribution to the later rehabilitation of the officer, Alfred Dreyfus, who was falsely convicted of treason .

Life

Childhood and youth in Provence (1840–1858)

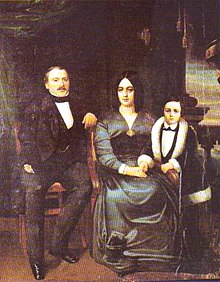

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola was born on April 2, 1840 on Rue Saint-Joseph in Paris to an Italian father and a French mother. He remained the only child of François Zola , born in Venice , and Émilie Aubert , who came from Dourdan . His father, a former officer in the Italian army, was a civil engineer and applied for a tender to build a drinking water supply in Aix-en-Provence from Mount Sainte-Victoire. He was awarded the contract on April 19, 1843 and subsequently settled with his family in Aix-en-Provence. After the contract was signed in 1844, he founded the Société du canal Zola company with some investors . Construction began in 1847, but in the same year Zola died of pneumonia after overseeing the construction of the Zola Dam near Aix-en-Provence . From that point on, the creditors began to pursue the canal company.

In 1851, Madame Aubert moved to Paris with her son to pursue legal action against Jules Migeon and the creditors who fought the canal company in court. They had the company declared bankrupt by the Aix-en-Provence Commercial Court in 1852. On May 10, 1853, the bankruptcy estate of the Société du canal Zola was auctioned. It was bought by the creditors and renamed Migeon et Compagnie . The now completely self-sufficient Émilie Aubert looked after her son together with her mother Henriette Aubert. She was very close to him until her death in 1880 and profoundly influenced the work and life of Émile Zola.

During his school days in Aix-en-Provence, Émile Zola made friends with Jean-Baptist Baille and especially Paul Cézanne , who introduced him to the graphic arts, especially painting. From his early teens, Émile Zola had a strong passion for literature. He read a lot and very soon set himself the goal of writing professionally himself. Even as a teenager he saw his true calling in writing. As a first grader in high school, he wrote a novel about the Crusades , but it has not survived. His childhood friends Cézanne and Baille became his first readers. In their correspondence, Zola predicted several times that one day he would be a recognized writer.

Bohème in Paris (1858–1862)

Émile Zola left Aix in 1858 and moved to his mother in Paris to live in modest circumstances and with the hope of finding success. In Paris, Zola slowly built up a circle of friends, most of which consisted of people from Aix. He began to read Molière , Montaigne and Shakespeare ; Balzac did not influence him until later. Contemporary authors like Jules Michelet also became a source of inspiration early on.

In 1859 Zola failed the baccalaureate exams twice . These setbacks left a deep mark on the young man, because he feared that he had disappointed his mother. He was also aware of the danger of getting into economic difficulties without a diploma. He now entered the labor market without qualifications and began working as a clerk in the customs office in April 1860. However, the job did not suit him and he dropped the position after only two months. A long period of unemployment followed, with moral and financial difficulties.

Zola's first love was Berthe. She was a prostitute with whom he fell in love in the winter of 1860/61. The young Zola himself called her "divided girl". He wanted to “get her out of the gutter” and give her the desire to work again, but his idealism failed because of the reality of the poor districts of Paris. At the same time, this failure provided the material for his first novel, La confession de Claude .

In this phase other passions broke through. Especially the impressionistic painting fascinated Zola, and he defended the Impressionists in his works. He became friends with Édouard Manet , who portrayed him several times in his works, and through Manet he found contact with Stéphane Mallarmé . He was also close to Camille Pissarro , Auguste Renoir , Alfred Sisley and Johan Barthold Jongkind . He had a special friendship with Paul Cézanne , his childhood friend. Until the 1870s the painter and the writer came together, they exchanged a rich correspondence and helped each other, also financially. The friendship later cooled and ended in a rift in 1886, because Cézanne recognized herself in Zola's novel The Work in the figure of the failing artist Lantier.

Beginnings in the publishing trade (1862–1865)

While unemployed, Zola came into contact with Louis Hachette , who took him on as an employee of his bookstore on March 1, 1862. On October 31, 1862, Emile Zola was naturalized as a French. He stayed in the advertising department of Hachette for four years, where he eventually held a position similar to the press secretary of a company today. He was valued and had the opportunity to make contacts in the world of literature.

The positivist and anti-clerical ideology at the Librairie Hachette shaped Zola. In addition, he learned all the techniques for making and marketing books. After hard work in his spare time, he managed to publish his first article and book, Les Contes à Ninon (1864 by Hetzel ).

At the end of 1864 Zola made the acquaintance of Éléonore-Alexandrine Meley , who let herself be called Gabrielle. Gabrielle was the name of her biological daughter who she had to give into state welfare at the age of 17. She probably told Emile Zola about this fact only after her wedding. Born in Paris on March 23, 1839, the woman was the daughter of a 17-year-old small market trader and a typographer from Rouen . Zola dedicated a portrait to her in 1865, entitled Love under the Roof ( L'amour sous les toits ), which appeared in the Petit Journal . The origin of this connection is not known. Perhaps it was a coincidence, as Zola and Alexandrine both lived on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève hill . There are rumors of a prior association with Paul Cézanne, or she might have worked as a model for the group of painters Zola was friends with. A prior connection with a medical student is also an option. However, none of these theories has been proven.

In 1865, Émile Zola left his mother and moved with his girlfriend to the Quartier des Batignolles on the right bank of the Seine , near Montmartre , where the offices of the most important press publishers were then. Zola's mother's reservations delayed the marriage for five years. At the beginning of 1866 Zola separated from the Librairie Hachette, in future he only wanted to make a living from writing. Alexandrine took on odd jobs to help the couple make ends meet.

Literary journalist

From 1863, Émile Zola worked occasionally and from 1866 regularly on the sections on literary and artistic criticism of various newspapers. The daily newspapers allowed the young man to publish his writings quickly, show his qualities as a writer to a wide audience, and increase his income. He thus benefited from the stormy development of the press in the second half of the 19th century. Up until his last days, Zola recommended that all up-and-coming writers who asked his advice should publish in newspapers first.

Zola started out in newspapers in northern France that were opponents of the Second Empire . He used his knowledge of the literary and artistic circles to successfully write critical articles. In 1866, at the age of 26, he received the art and literature columns in the newspaper L'Événement . In L'Illustration he published two short stories with some success. After that, his contributions became more numerous: hundreds of articles appeared in a variety of magazines and newspapers. The most important were L'Événement and L'Événement Illustré , La Cloche , Le Figaro , Le Voltaire , Le Sémaphore de Marseille and Le Bien public from Dijon .

In addition to literary, theater and art criticism, Zola published over 100 stories and feature pages in the press . He used a polemical journalism by showing his hatred, but also his taste and emphasizing his aesthetic and political positions. Zola mastered the journalistic craft perfectly and used the press as a tool to promote his literary work. For his early works, Zola even sent ready-made reports to Paris literary critics personally and received a great deal of feedback from them.

Political journalist

The commitment of Émile Zola is particularly evident through his appearances in the political press. The liberalization of the press in 1868 enabled him to take an active part in its expansion. Through friends of Manet, Zola came across the new Republican weekly La Tribune , where he lived out his polemical talents by writing fine anti-emperor satires. However, the most poisonous of his attacks against the Empire were published in the satirical magazine La Cloche (founded in 1868 by Louis Ulbach ).

From 1868 he was friends thanks to his journalistic work with the brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt . Zola was a sociable person who cultivated many friendships, but had no tendency towards the glamorous life. He made friends primarily with artists and writers and avoided politicians.

On May 31, 1870, on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War , Émile Zola and Alexandrine married in the town hall of the 17th arrondissement. Paul Cézanne , Paul Alexis , Marius Roux and Philippe Solari were witnesses. Alexandrine then became an irreplaceable support for Zola in the numerous moments of self-doubt. For that he was forever grateful to her. When the war broke out in July 1870, Zola was not mobilized. He could have been drafted into the Mobile Guard , but his shortsightedness and maintenance status (for his mother) prevented him.

Zola watched the fall of the Second Empire with irony, but did not stay in Paris during the "Bloody Week" in May 1871. Although he did not share the spirit of the Paris Commune , unlike Flaubert, Goncourt or Daudet, he rejected their violent suppression. He left them to be treated moderately in his writings. On June 3, 1871, Zola wrote of the people of Paris in the Sémaphore de Marseille newspaper : “The bloodshed was perhaps just a terrible necessity to calm some of his fevers. They will now be seen to grow stronger in wisdom and glory. ”When the republic was proclaimed, Zola tried to be appointed sub-prefect of Aix-en-Provence and Castelsarrasin . Despite a trip to Bordeaux, where the government had been evacuated, he failed. Zola was not a man of intrigue or networking.

In 1871 he met Gustave Flaubert . The latter introduced him to Alphonse Daudet and Ivan Turgenev at one of their Sunday meetings . All his life Zola raved about the small group, "in which the three to six of us rode a gallop over all subjects, where it was always about literature, the current book or a current play, general topics or the most daring theories" .

From February 1871 to August 1872, Zola produced more than 250 articles critical of Parliament's work. In a courageous to foolhardy manner, Zola attacked the leading figures. He berated Parliament as a "shy, reactionary and [...] manipulated house". For the writer, the opinionated comments were not without risk. He was arrested twice in March 1871, but both were released on the same day. He later processed the political material in his novels.

Zola kept a distance from politics that enabled him to interfere with restraint, distance and serenity. He was not interested in his own political action, and he never allowed himself to be run as a candidate for an election. He saw himself primarily as a writer with unruly views. He was committed to social, artistic or literary goals that seemed fair to him and remained an observer of the people and events of his time. He acted as a free thinker, as an independent moralist and was classified as a moderate liberal.

Zola kept his job as a journalist until 1881. Apart from sporadic requests to speak, he did not speak again until the Dreyfus affair in the press: at the end of 1897 in Le Figaro and at the beginning of 1898 in L'Aurore .

Zola as a successful novelist

In 1867, Émile Zola had already caused a stir with his third novel, Thérèse Raquin . In 1869 he began work on the monumental cycle Die Rougon-Macquart , which would keep him busy for more than twenty years. From 1871 he published one novel per year, as well as journalistic articles and plays such as Les Nouveaux Contes à Ninon .

The first novels of the Rougon-Macquart cycle have a satirical and political thrust. When, after the proclamation of the republic, his novel Die Beute (1871) fell victim to censorship, Zola was deeply disappointed. But he remained an ardent republican, because for him the republic was "the only just form of government that is possible". Zola kept his distance from political operations. Politicians didn't seem trustworthy to him, and before the Dreyfus Affair he had no friends in politics. This is borne out by Zola's correspondence from 1871 to 1897.

After Zola had to struggle with considerable financial difficulties for years, his situation improved after the great success of Der Totschläger from 1877. As early as 1878, Zola was able to acquire a country house in Médan near Poissy . From then on he had an annual income of between 80,000 and 100,000 francs. This made Zola wealthy, but he also had to maintain his mother and two houses.

Zola also got along with young authors such as Guy de Maupassant , Paul Alexis , Joris-Karl Huysmans , Léon Hennique and Henri Céard . They often met for social evenings at his home in Médan. This was the group of six that appear in the cycle of novels Les Soirées de Médan (1880).

1880 was a difficult year for the writer. The death of Edmond Duranty , then especially that of Gustave Flaubert, shook him. When his mother died at the end of the year, Zola fell into a depression. Since he was now financially independent through the regular publication of the Rougon Macquart novels, he gave up his activity as a journalist in 1881. On this occasion he published an article in Figaro entitled Adieux (“Farewell”), in which he reviewed 15 years of journalistic arguments in the press. However, in his heart he remained a journalist. For example, the plot of Germinal (1885) is inspired by encounters with miners and meticulously describes the soaring mining stocks on the Lille stock exchange.

Zola's strengths included his creativity and persistence according to his motto, which he had painted on the fireplace of his study in Médan: Nulla dies sine linea (“No day without a line”). For more than 30 years, Zola was strict about his time, although his plans were subject to change, especially when he had to reconcile journalism and novel writing. In Médan, Zola used to get up at 7 a.m., have a quick breakfast and walk his dog for half an hour on the Seine . Then began his first working session, which lasted about 4 hours and in which he produced five pages. He spent the afternoon reading and correspondence, which Zola took up a lot. At the end of his life he changed these habits in order to devote more time to his two illegitimate children, whom he had with his lover Jeanne Rozerot, in the afternoon, but he postponed some of his activities into the evening and night.

When his political involvement meant that fewer of his novels were sold, he could run into financial difficulties at times. This was usually only temporary and Zola had no major financial difficulties until his death. His feuilleton novels earned him an average of 1,500 francs and he earned 50 cents on every copy of the novel sold. The numerous translations and adaptations of his novels for the theater were further important sources of income. Thus, Zola's income increased and by 1895 reached about 150,000 francs a year.

Between 1894 and 1898 Zola published a second cycle of novels: Trois Villes , consisting of three volumes.

The narrative work of Zola, like that of the Goncourts , is a treasure trove for social historians .

Dreyfus affair

On January 13, 1898, he tried to use his personal prestige in an open letter to President Félix Faure for Captain Alfred Dreyfus , the first French Jew on the General Staff , who was wrongly condemned as a pro-German traitor . This letter with the title J'accuse…! (“I accuse…!”) Sparked an unexpected domestic political storm ( Dreyfus affair ), which for years split France into Dreyfusards and Antidreyfusards , often down to the families . H. into a progressive left and a conservative right that was both militant-nationalist and anti-Semitic .

Zola himself was sued by the Minister of War and by a few private individuals in 1898 and sentenced to a fine and (short) prison term in political trials for defamation. He escaped punishment by fleeing to London, where he stayed for almost a year.

death

In 1898 Zola began a third cycle of novels: Four Gospels (Quatre Evangiles) . The fourth volume, entitled Justice , remained unfinished. Zola died of carbon monoxide poisoning in his Paris home at the beginning of the heating season in the fall of 1902 . Rumors that he was murdered by deliberately plugging the chimney have not been entirely dispelled to this day. There is a burial site in the Montmartre cemetery .

After Zola's death, his wife Gabrielle reconciled with his lover Jeanne Rozerot, so that the two illegitimate children could take his name.

On June 4, 1908, the remains of Zola were transferred to the Panthéon by order of the Georges Clemenceau government , probably also to honor the involvement in the Dreyfus affair.

Works

Thérèse Raquin

Zola's first major novel was Thérèse Raquin (1867). Zola combines an exciting plot about the eponymous heroine, who becomes an adulteress and murderer, with an unadorned portrayal of the Parisian petty bourgeoisie. The foreword to the 2nd edition in 1868, in which Zola defended himself against his critics (especially Louis Ulbach ) and their accusation of bad taste, became the manifesto of the young naturalistic school, of which Zola gradually advanced to become its head.

The cycle The Rougon-Macquart

Starting in 1869, Zola designed most of his novels as part of a cycle entitled Les Rougon-Macquart, based on the model of Honoré de Balzac . Histoire naturelle et sociale d'une famille sous le Second Empire ("The Rougon-Macquart. The natural and social history of a family in the Second Empire"). The total of 20 novels should be a kind of positivist-based family history, with the Rougon branch of the bourgeoisie and the Macquart branch of the lower class. The individual figures should be presented as determined by their genetic makeup (e.g. tendency towards alcoholism ), their milieu (bourgeoisie or lower class) and historical circumstances (the socio-economic conditions of the Second Empire , 1852–1870). Even if the novels were enthusiastic thanks to Zola's literary temperament, over time he was accused of a mechanistic and overly scientific conception. From the 1890s onwards, he himself realized that his confession as an “old, furrowed positivist” was going out of fashion and being overwhelmed by an era of “new mysticism”.

Several novels, including Der Totschläger , Nana and Germinal , were turned into successful plays soon after their publication.

The 20 novels of the cycle:

- The happiness of the Rougon family ( La fortune des Rougon 1871), Manesse Library of World Literature 2003, ISBN 3-7175-2024-5 .

- The booty ( La curée 1871), Artemis & Winkler 1998, ISBN 3-538-05401-0 .

- The Belly of Paris ( Le ventre de Paris 1873). The most important locations are the famous market halls of Paris.

- The conquest of Plassans ( La conquête de Plassans 1874). The novel is about a scheming clergyman who brings misfortune to a family. After the Catholic Church intervened, the Colportage Commission banned the sale of the novel at train stations.

- The sin of the Abbé Mouret ( La faute de l'Abbé Mouret 1875). In this work Zola attacked the church dogma of chastity.

- His Excellency Eugène Rougon ( Son excellence Eugène Rougon 1876)

- The Blackjack ( L'Assommoir 1877). Using the fate of a laundress and her family, Zola vividly describes the effects of alcoholism in the cramped and dreary lower-class milieu of Paris.

- A leaf of love ( Une page d'amour 1878)

- Nana ( Nana 1880). (German EA 1881, published by J. Gnadenfeld and Co. Berlin W. 30. (shortened by 100 pages)). The story of a young woman from the people who, thanks to her sexual attractiveness, rises to the costly lover of a count, but who experiences a decline through debauchery of all kinds, falls ill and dies early. The novel became a great success.

- A fine house ( Pot-Bouille 1882)

- Ladies' Paradise ( Au bonheur des dames 1883). The action takes place in a modern Parisian department store in which a young girl from the provinces works as a saleswoman.

- The joy of life ( La joie de vivre 1884)

- Germinal ( Germinal 1885), Manesse Library of World Literature 2002, ISBN 3-7175-2000-8 . The dramatic story of a miners' strike in the force field of the economic and ideological antagonisms of the time. Zola writes from the perspective of a socially active personand demonstrates the practical effects ofopposing directions within the labor movement (especially Marx , Bakunin and reformism ).

- The work ( L'Œuvre 1886). The protagonist is a failed painter. Paul Cézanne said he was represented in this figure. Outraged, he sent Zola one last letter. This ended the friendship, and Cézanne and Zola never saw each other again.

- The earth ( La terre 1887). This novel deals with the rural milieu.

- The dream ( Le rêve 1888)

- The beast in man / The beast in man ( La bête humaine 1890)

- Das Geld ( L'argent 1891), last published in paperback in the translation by Leopold Rosenzweig by Insel Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-458-36227-2 .

- The collapse ( La débâcle 1892). This novel was the most successful in Zola's lifetime. The action takes place against the backdrop of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 and the bloody oppressed Paris Commune .

- Doctor Pascal ( Le docteur Pascal 1893), Manesse Library of World Literature 1970

The complete German edition of the cycle was published by Verlag Rütten & Loening in Berlin, the capital of the GDR (several editions, also as a paperback), as well as by Artemis & Winkler, Zurich. A book club edition based on this edition was published by Bertelsmann Buchclub in the 1970s.

The complete works appeared as an electronic resource in 2005 as volume 128 of the digital library , edited by Rita Schober ( Directmedia Publishing , ISBN 3-89853-528-2 ).

┌─ Eugène Rougon ┌─ Maxime Rougon Saccard ──── Charles Rougon Saccard

│ 1811-? │ 1840-1873 1857-1873

│ │

├─ Pascal Rougon ├─ Clotilde Rougon Saccard ── A child

│ 1813-1873 │ 1847-? 1874-?

│ │

┌─ Pierre Rougon ────┼─ Aristide Rougon ───┴─ Victor Rougon Saccard

│ 1787-1870 │ 1815-? 1853-?

│ │

│ ├─ Sidonie Rougon ────── Angélique Rougon Saccard

│ │ 1818-? 1851-1869

│ │

│ └─ Marthe Rougon ───┐ ┌─ Octave Mouret ──────────── Two children

│ 1819-1864 │ │ 1840-

│ │ │

│ ├─┼─ Serge Mouret ───────────── A son and a daughter

│ │ │ 1841-?

│ │ │

│ ┌─ François Mouret ─┘ └─ Désirée Mouret

│ │ 1817-1864 1844-?

│ │

Adélaïde Fouque ─┼─ Ursule Macquart ──┼─ Hélène Mouret ────── Jeanne Grandjean

1768-1873 │ 1791-1839 │ 1824-? 1842-1855

│ │

│ └─ Silvère Mouret

│ 1834-1851

│

│ ┌─ Lisa Macquart ─────── Pauline Quenu

│ │ 1827-1863 1852-?

│ │

│ │ ┌─ Claude Lantier ─────────── Jacques-Louis Lantier

│ │ │ 1842-1870 1860-1869

│ │ │

└─ Antoine Macquart ─┼─ Gervaise Macquart ─┼─ Jacques Lantier

1789-1873 │ 1829-1869 │ 1844-1870

│ │

│ ├─ Étienne Lantier ────────── A daughter

│ │ 1846-?

│ │

│ └─ Anna Coupeau dite Nana ─── Louis Coupeau called Louiset

│ 1852-1870 1867-1870

│

└─ Jean Macquart ─────── Two children

1831-?

The Trois Villes cycle

Pierre, a young priest, learns about social and economic misery through his work in the slums of Paris. In the quarrel between faith and reason, he chooses reason and gives up his office. The cycle consists of three novels:

- Lourdes (1894). Pierre accompanies a pilgrimage. This brings him to the realization that most people cannot endure serious illnesses without faith. This is taken advantage of by business people and part of the clergy. He is looking for a new religion that does not nourish illusions, but rather creates justice.

- Rome (1896). Pierre has written a book on the great misery of the poor with proposals for solutions to eliminate the social injustices that the Church puts on the index as revolutionary. He wants to correct this in a conversation with Pope Leo XIII . But he has to recognize that the church is neither willing nor able to reform.

- Paris (1898). Back in Paris, Pierre realizes that nothing can be expected from politics either. The MPs are busy with a financial scandal ( Panama scandal ), he rejects the solution with violence (anarchist trials), in which his brother is also involved. So in the end he only has reason. Science should be the new religion, the educator of humanity.

The Quatre Evangiles (Four Gospels) cycle

The political Dreyfus Affair marked a turning point in Zola's poetic work, which was expressed in the final cycle Quatre Evangiles , which emerged from socialist impetus . The unfinished novel cycle consists of four parts and as a document of the fin de siècle is therefore also of contemporary historical importance:

- Fécondité (fertility) (1899). In this novel, on the foil of the entire complex of birth control and eugenics , in a moral-biological disguised sense, it is about a “deception” against nature.

- Travail (work) (1901) anticipates the transformation of high capitalist structures into a society of universal prosperity in a utopian way and based on the theories of Charles Fourier .

- Vérité (Truth) (1903). This novel transfers the Dreyfus affair in great detail to the school system in the cultural war that has since broken out.

- Justice (unfinished)

Other works (selection)

- Master narratives , Manesse Library of World Literature , Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-7175-1630-2

-

Madame Sourdis, in French Tales from Chateaubriand to France . Vorw. Victor Klemperer , transl. Günther Steinig. Dieterich Collection, 124. Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung , Leipzig 1951, pp. 330–378.

- dsb. Over, separate print. Nachw. Horst-Werner Nöckler. (Illustr. As in 1960) Henschel, Berlin 1958.

- other translations Eva Rechel-Mertens , Nachw. Horst-Werner Nöckler. 24 drawings by Günter Horlbeck . Henschel, Berlin 1960

Movie

Biography

- The life of Emile Zola , biography by William Dieterle , USA 1937 (Oscar for best film), title role: Paul Muni

- My time with Cézanne , biography by Danièle Thompson , France 2016, describes Zola's friendship with Paul Cézanne

Film adaptations

- Les Victimes de l'alcoolisme , (after The Blackjack ), Ferdinand Zecca , F 1902

- L'Assomoir ( Albert Capellani ), F 1909

- Germinal ( Albert Capellani ), F 1913

- La terre ( André Antoine ), F 1921

- Le Rêve ( Jacques de Baroncelli ), F 1921

- Nana ( Jean Renoir ), F 1926

- The Money ( Marcel L'Herbier ), F 1928

- Women's Paradise ( Julien Duvivier ), F 1930

- Beast Man (Jean Renoir), F 1938

- Thérèse Raquin - You shall not commit adultery ( Marcel Carné ), F / I 1953

- Greed for Life ( Fritz Lang ), USA 1954

- The Prey ( Roger Vadim ), F 1966

- The Sin of the Abbé Mouret ( Georges Franju ), F 1970

- Germinal ( Claude Berri ), B / F / I 1993

- The Paradise (Bill Gallagher), TV Series, UK 2012-2013

radio play

- Zola's chimney ; (with audio file). Detective radio play (about Zola's death) by Christoph Prochnow, director: Rainer Clute, Deutschlandradio Kultur, February 17, 2014, 9:33 pm-10:30pm

- Germinal . Audio book. Read by Hans-Helmut Dickow , Der Audio Verlag , Berlin, 2007, ISBN 978-3-86735-258-1

- Nana . Scenic audio book. Speaker: Ernst-August Schepmann , Julia Grimpe , Ulrike Johannson. Editor: Brigitte Röttgers. Director: Jürgen Nola. Berlin, Universal Music Group, 2010 ISBN 978-3-8291-2338-9

- The money . Radio play by Christiane Ohaus, OSTERWOLD audio , Hamburg, 2014, ISBN 978-3-86952-185-5

literature

- Irene Albers : Seeing and Knowing. The photographic in Émile Zola's novels. (= Theory and history of literature and the fine arts. 105). W. Fink, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7705-3769-6 .

- Horst Althaus: Between the old and the new owning class. Stendhal, Balzac, Flaubert, Zola. Contribution to French social history. (= Writings on cultural sociology. 8). Reimer, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-496-00899-7 .

- Veronika Beci : Émile Zola. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-538-07137-3 .

- Cord-Friedrich Berghahn: Émile Zola. Life in Pictures . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin / Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-422-07209-1 .

- Marc Bernard: Emile Zola. With testimonials and photo documents. (= rororo 50024; Rowohlt's monographs ). 6th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-50024-8 .

- Manuela Biele-Wrunsch: The friendship between Édouard Manet and Émile Zola. Aesthetic and genre-specific touches and differences. Driesen, Taunusstein 2004, ISBN 3-936328-17-X .

- Martin Braun: Emile Zola and romance. Legacy or inheritance? Study of a complex conception of naturalism. (= Erlangen Romanesque documents and works. 10). Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-923721-99-4 .

- Ronald Daus: Zola and French Naturalism. (= Metzler Collection. 146). Metzler, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-476-10146-0 .

- Herbert Eulenberg : Emile Zola. In: shadow images. A primer for those in need of culture in Germany. First Berlin in 1909.

- Günter Helmes : Georg Brandes and French Naturalism. With particular reference to Émile Zola. In: Georg Brandes and the modernity discourse. Modern and anti-modern in Europe I, ed. v. Matthias Bauer and Ivy York Möller-Christensen. Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-86815-571-6 , pp. 42-74.

- Frederick WJ Hemmings: Emile Zola. Chronicler and accuser of his time. Biography. (= Fischer library. 5099). Fischer, Frankfurt 1981, ISBN 3-596-25099-4 .

- Joseph Jurt : France's committed intellectuals. From Zola to Bourdieu . Wallstein, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8353-1048-3 .

- Karl Korn : Zola in his time. (= Ullstein Life Pictures. 27532). Ullstein, Frankfurt 1984.

- Till R. Kuhnle: The millenarianism Zola and the Third Republic . In: Ders .: The trauma of progress. Four studies on the pathogenesis of literary discourses. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-86057-162-1 , pp. 273-285.

- Heinrich Mann : Zola. In: Spirit and Action. French from 1780 to 1930. Essays, Berlin 1931. (Again: Fischer TB, Frankfurt 1997, ISBN 3-596-12860-9 ; first edition 1915)

- Henri Mitterand : Émile Zola . In: La Grande Encyclopédie . 20 volumes, Larousse, Paris 1971–1976, pp. 14779–14788 (French).

- Peter Müller: Emile Zola, the author in the field of tension of his era. Apology, social criticism and social sense of mission in his thinking and literary work. (= Romance treatises. 3). Metzler, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-476-00477-5 .

- Ralf Nestmeyer : French poets and their homes . Insel, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-458-34793-3 .

- Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer : Popular novels in the 19th century. From Dumas to Zola. Fink, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-7705-1336-3 .

- Viktor Roth: Émile Zola at the turn of the century. Stations of a combative career. Steinmeier, Nördlingen 1987.

- Barbara Vinken : Zola. See everything, know everything, heal everything. The fetishism in naturalism. In: Rudolf Behrens, Roland Galle (ed.): Historical anthropology and literature . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1996, pp. 215–226.

- Barbara Vinken: Balzac - Zola: Hysterical Madonnas - New Mothers. In: Doris Ruhe (Ed.): Gender difference in interdisciplinary discussion . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1998, pp. 117-134.

- Barbara Vinken: Pygmalion à rebors: Zola's oeuvre. In: Mathias Mayer, Gerhard Neumann (ed.): Pygmalion. The history of myth in western culture. Rombach, Freiburg 1997, pp. 593-621.

- To individual novel cycles or works

- Willi Hirdt: Alcohol in French Naturalism. The context of the “Assommoir”. (= Treatises on art, music and literary studies. 391). Bouvier, Bonn 1991, ISBN 3-416-02286-6 .

- Elke Kaiser: Knowledge and storytelling at Zola. Reality modeling in the "Rougon-Macquart". (= Romanica Monacensia. 33). Narr, Tübingen 1990, ISBN 3-8233-4300-9 .

- Sabine Küster: Medicine in a novel. Studies on "Les Rougon-Macquart" by Émile Zola. Cuvillier, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-86727-793-8 .

- Stephan Leopold: The messianic overcoming of the mortalistic abyss: "Le docteur Pascal" and "Les Quatre Évangiles". In: Stephan Leopold, Dietrich Scholler (ed.): From decadence to the new life discourses. French literature and culture between Sedan and Vichy . W. Fink, Munich 2010, pp. 141–167.

- Susanne Schmidt: The contrast technique in the "Rougon-Macquart". (= Bonn Romance works. 30). Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-631-40612-6 .

- To the reception

- 100 years of “Rougon-Macquart” in the course of the history of reception. At the same time, supplement to the journal Articles on Romance Philology . Eds. Winfried Engler , Rita Schober. Narr, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-8233-4145-6 .

- Vera Ingunn Moe: German Naturalism and Foreign Literature. On the reception of the works of Zola, Ibsen and Dostoevsky by the German naturalistic movement (1880–1895). (= European university publications. Series 1. 729). Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1983, ISBN 3-8204-5262-1 .

- Rolf Sältzer: Development lines of the German Zola reception from the beginning to the death of the author. (= New York University Ottendorfer series. NF 31). Peter Lang, Bern 1989, ISBN 3-261-03928-0 .

- Karl Zieger: The reception of the works of Emile Zola by the Austrian literary criticism of the turn of the century. (= European university publications. Series 18. 44). Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1986, ISBN 3-261-03560-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Émile Zola in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Émile Zola in the German Digital Library

- Levke Harders: Émile Zola. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Article in name, title and dates of the French Literature (source for the biography). Called on March 10, 2013

- Erich Köhler : Lectures on the history of French literature , Volume 6.2 (PDF), pp. 198–223 (interpretation and presentation of the main works)

- Works by Émile Zola at Zeno.org .

- Works by Émile Zola in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Émile Zola in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Encyclopédie Larousse : Émile Zola , visited on April 11, 2013.

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, ISBN 2-213-60083-X , pp. 18-30 .

- ↑ Emile Zola, biography ladissertation.com (French)

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola. Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins 1993, ISBN 2-221-07612-5 , p. 47.

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Zola: la vérité en marche. Découvertes Gallimard 1995, ISBN 2-07-053288-7 , p. 19.

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, p. 110 .

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, p. 470 f .

- ↑ Brockhaus, The Greats of the World. Volume 5. Brockhaus, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-7653-9265-0 , p. 155.

- ^ Marie-Aude de Langenhagen, Gilbert Guislan: Zola - Panorama d'un auteur . P. 20 f.

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, p. 380 .

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola. Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins 1993, p. 244.

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, p. 376-379 .

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola. Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins 1993, p. 200.

- ↑ Histoire de la Presse en France, PUF, p. 397 f.

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola. Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins 1993, pp. 202-203.

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, p. 408 f .

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola . Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins, 1993, p. 462 .

- ↑ Michèle Sacquin and others: Zola . Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fayard, 2002, ISBN 2-213-61354-0 , p. 51 .

- ↑ Le Cri du Peuple. Vol. 4: Le Testament des ruines. Tardi et Vautrin.

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, p. 766 .

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Émile Zola . tape 1 : Sous le regard d'Olympia. 1840-1871 . Paris 1999, p. 773 .

- ↑ Michèle Sacquin and others: Zola . Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fayard, 2002, p. 80 .

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola . Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins, 1993, p. 357 .

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola . Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins, 1993, p. 357 .

- ^ Henri Mitterand: Zola: la vérité en marche . Découvertes Gallimard, 1995, ISBN 2-07-053288-7 , p. 31 .

- ↑ Emila Zola: Adieux. Le Figaro, September 22, 1881, accessed December 7, 2013 .

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola . Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins, 1993, p. 362 .

- ↑ A teacher had an annual income of between 700 and 1,000 francs, a good journalist had about 10,000 francs.

- ↑ Emila Zola: Adieux. Le Figaro, September 22, 1881, accessed December 7, 2013 .

- ↑ Émile Zola, Germinal , Part 2, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola. Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins 1993, p. 128 f.

- ↑ Brockhaus, The Greats of the World. Volume 5. Brockhaus, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-7653-9265-0 , p. 161.

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola . Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins, 1993, p. 364 .

- ^ Henri Mitterand : Zola. Volume 3: L'Honneur . Fayard, Paris 2002, pp. 807 f.

- ↑ Brockhaus, The Greats of the World. Volume 5. Brockhaus, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-7653-9265-0 , p. 161.

- ↑ Ed. And transl. Wolfgang Tschöke. dtv, Munich 2002.

- ↑ See Zola's speech of May 20, 1893 to university graduates in Paris, published in English on June 20, 1893 in the New York Times .

- ↑ Michèle Sacquin and others: Zola . Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fayard, 2002, p. 76 .

- ↑ Colette Becker, Gina Gourdin-Servenière, Véronique Lavielle: Dictionnaire d'Émile Zola . Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins, 1993, p. 243 .

- ↑ The notes on the trip to Rome appeared in a separate book: My trip to Rome. Translated from the French by Helmut Moysich, Dietrich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Mainz 2014, ISBN 978-3-87162-081-2 .

- ↑ Contains: Who loves me. The blood. A victim of advertising. The four days of Jean Gourdon. For a night of love. Nais Micoulin. Nantas. The death of Oliver Bécaille. Monsieur Chabre's mussels. Jaques Damour. Angeline.

- ↑ Albert Capellani - L'Assomoir et autres Drames , accessed on 27 June 2016th

- ↑ The bibliography has been supplemented since 1997 (last title from 1995). All issues nevertheless with the same ISBN. Only the 2002 edition with a personal register.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zola, Émile |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zola, Émile François (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French writer and journalist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 2, 1840 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 29, 1902 |

| Place of death | Paris |