Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus [ alˈfʀɛd dʀɛˈfys ] ( October 9, 1859 in Mulhouse - July 12, 1935 in Paris ) was a French officer. His unjustified conviction for treason sparked the Dreyfus affair in 1894 , which deeply shook France domestically.

Family and childhood

Alfred Dreyfus was the ninth and youngest son of a Jewish textile entrepreneur from Mülhausen who had started his career as a peddler. When Alsace became part of the newly founded German Empire in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War , his parents (as well as other members of the urban elite) opted to keep their French citizenship and moved part of the family to Paris in 1872. In order to save the fortune, another part of the family stayed in Alsace. Only Alfred and his brother received a completely French education. The first language of most of Alfred's brothers and sisters was German or Alsatian .

Dreyfus passed the Baccalauréat in Paris and passed the entrance examination to the traditional École polytechnique in 1878 , which at that time was mainly technical officers, e.g. B. for the artillery trained. He became a career officer as an artilleryman and, because of his academic achievements, was accepted into the École supérieure de guerre . The École supérieure de guerre was only founded towards the end of the 1870s. Graduates of the École polytechnique and the Saint-Cyr military school received a final training here before being appointed staff officer. One of the innovations introduced by War Minister Charles de Freycinet and General Marie François Joseph de Miribel as part of their reforms of the French military was the admission of the twelve best graduates from this military school to the French General Staff, where they went through several areas. Previously, these positions had been awarded exclusively by co-option , which led to the fact that predominantly Catholic nobles were appointed to the General Staff.

On April 21, 1890, he married Lucie Hadamard (1869-1945), daughter of a wealthy diamond trader and sister of the mathematician Jacques Salomon Hadamard . The marriage had two children: Pierre (1891–1946) and Jeanne (1893–1981).

In 1893 Dreyfus, meanwhile promoted to captain , was transferred to the general staff .

The Dreyfus Affair

development

In September 1894, the French foreign intelligence service ( Deuxième Bureau ), allegedly through a spy smuggled into the German embassy , came into possession of a handwritten document in which an apparently well-informed anonymous insider gave the German military attaché Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen secret military information, in particular about the French artillery, listed and promised to deliver. (The M 1890 howitzer was explicitly mentioned here .) The suspicion quickly fell on the artilleryman Alfred Dreyfus, whom his origins as an Alsatian Jew seemed predestined to be a traitor, especially since he had traveled to Mulhouse the previous year, even if only for the funeral of his father , which then belonged to the German Empire.

On October 15, he was summoned to the office of the Chief of Staff, asked to write individual words and scraps of sentences as dictated, and then arrested.

Preliminary investigations were completed on October 31, and a day later Dreyfus was already mentioned in the press as a traitor. On November 3, he was in front of a court martial in Rennes for treason accused. In the subsequent trial, the main evidence of his guilt was a graphological report by the well-known anthropologist and criminologist Alphonse Bertillon , which the judges followed, despite three dissenting reports and despite the fact that Bertillon had demonstrably no experience in comparing scriptures.

Dreyfus, who had vainly pleaded his innocence, was found guilty on December 22, 1894 by a unanimous vote of the judges and sentenced to life in exile and imprisonment. He refused the easing of imprisonment promised to him should he confess his espionage. On January 5, 1895, he was demoted in degrading form in the court of the École Militaire .

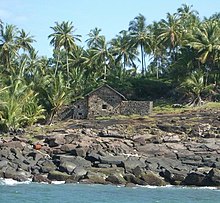

On January 31, 1895, the French Chamber of Deputies decided to ban Dreyfus to Devil's Island in French Guiana . The conditions of detention there were so severe that convicts were rarely sent to French Guiana. Dreyfus was to live on Devil's Island in the future, which would not only make escape impossible, but also isolate him completely from other prisoners. Lucie Dreyfus' original plans to follow her husband into exile were also made impossible by this decision.

Without informing the family in advance, Alfred Dreyfus' journey into exile began in the early morning of January 17, 1895. He was first taken to La Rochelle by train. When it became known that Dreyfus was on the train, such an angry crowd gathered that the authorities in charge considered it safer to keep him waiting on the train until late at night before taking him to the nearby fortress of Saint-Martin on the Île de Ré . Nevertheless, there were assaults. On February 13th he was able to see his wife Lucie for the last time. Lucie Dreyfus was forbidden to tell her husband where he was going to be deported, and the spouses were also forbidden from hugging, as it was feared that Lucie would slip a message to her husband.

Dreyfus left Île de Ré on February 21st and arrived on Devil's Island on April 13th. He was the only prisoner on the island. His detention conditions were initially relatively mild. For example, he was allowed to walk a few hundred meters every day. At night he was locked in a four-square-meter hut. He was guarded by five guards who, however, were not allowed to speak to him. Due to the climatic conditions, however, Dreyfus repeatedly contracted tropical fevers. While the high humidity prevented his clothes from drying out, he lost a lot of weight due to the lack of food. Conditions of detention changed on September 6, 1896, when rumors of an escape plan began to circulate in Paris. A picket fence was built around the hut, which blocked Dreyfus from any view of his surroundings. He was handcuffed to his bed at night.

distributed by F. Hamel , Altona - Hamburg ...; Stereoscopy from the Lachmund Collection

Dreyfus received letters from his family and was also allowed to write to them. However, correspondence with the family was strictly censored. Dreyfus only received copies of his wife's letters so that she could not convey any secret messages to him. It was not allowed to address in the letters the sensation that his case was increasingly causing in France, so that Dreyfus remained ignorant of it until his return to the second trial in 1899. In her monograph on the Dreyfus case, Ruth Harris describes his letters to his family as surprisingly free from bitterness. Dreyfus did not mention his belonging to the Jewish faith nor did he suggest that he might be the victim of an anti-Semitic conspiracy. His letters express a deep longing for his family and he repeatedly asks his wife Lucie and brother Mathieu to restore his honor.

Thanks to the persistence of relatives, especially his older brother Mathieu, who was convinced of Dreyfus' innocence and interested various personalities from politics and the press in the case, it did not disappear into oblivion. In the summer of 1896, the new head of the secret service, Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart , came across evidence that suggested that another general staff officer, Major Esterházy , must have been the traitor. However, he was silenced by the General Staff and transferred to Tunisia at the turn of the year . From there, however, he addressed a memorandum to President Félix Faure , which ended up in the hands of a senator . Its rather discreet attempts to obtain a revision of the process failed due to resistance from the generals and the government. In the autumn of 1897, Mathieu Dreyfus also became aware of the contents of the memorandum and publicly accused Esterházy of being the traitor. The disciplinary proceedings that he then applied against him quickly ended with no result. The same was true of a pro forma trial opened against him in early 1898. The generals who had stood as witnesses against Dreyfus were unwilling to retract their statements. Rather, they had even subsequently falsified indications to his disadvantage.

When Esterházy was immediately acquitted on January 11, many people reacted with indignation. The open letter J'accuse ... sparked a real domestic political storm ! ( I accuse…! ), Which the well-known author Émile Zola addressed to the President Félix Faure in the newspaper L'Aurore on January 13, 1898, to draw attention to the injustice against Dreyfus.

The French society was polarized by the Dreyfus Affair , as it was now called, down to the families and split into "Dreyfusards" and "Anti-Dreyfusards".

Revision and pardon

After the Justice Minister had rejected two requests from Dreyfus' wife Lucie in July and September 1898 or referred them to a commission, the government finally decided to act. At the end of September, the French Court of Cassation was given the task of revising the 1894 case. He overturned the verdict against Dreyfus in June 1899 and referred the case back to the Rennes court martial. Dreyfus was allowed to leave Devil's Island on June 9, 1899 and returned to France on June 30, 1899. At the new trial in August, he was still found guilty, but was granted extenuating circumstances. His sentence was commuted to ten years of imprisonment , but the new French President Émile Loubet offered him an immediate pardon if he did not appeal. Dreyfus accepted on September 15, which disappointed many of his sympathizers.

He withdrew to his family and put his memories on paper, which he published in 1901 under the title Cinq années de ma vie 1894–1899 (“Five years of my life”).

Rehabilitation

After the left electoral victory in 1902, a renewed discussion about his case began under the changed political circumstances. Finally, the last trial was also revised by the Court of Cassation. The sentence was overturned and Dreyfus acquitted and rehabilitated on July 12, 1906. Immediately afterwards he was admitted back into the army with a solemn act, promoted to major and also made a knight of the Legion of Honor . A continuation of his career as a general staff officer was denied to him. He was only used briefly as the commandant of two artillery depots in the Paris region, in Vincennes and Saint-Denis . In October 1907 he took early retirement for health reasons.

When in 1908 the remains of Zola, who had died in 1902, were transferred to the French temple of fame, the Paris Panthéon , with an escort of honor to which Dreyfus belonged, an anti-Dreyfusard from the crowd carried out a pistol attack on him. But he was only injured.

After the beginning of the First World War , Dreyfus had himself reactivated, stood at the front and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. With this rank he left the army at the end of the war .

Death and afterlife

Dreyfus died of a heart attack in Paris in 1935 . He was buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

His granddaughter Madeleine Levy was later deported as a Jew to Auschwitz during World War II and murdered there. His wife Lucie survived the Holocaust and died shortly after the liberation in Paris.

Theodor Herzl , who had witnessed Dreyfus' demotion as a correspondent for the Neue Freie Presse in 1895 , wrote his book Der Judenstaat under the impression of the trial . The work was published on February 14, 1896, before the first Zionist congress took place in Basel from August 29 to 31, 1896 .

After the Second World War, Dreyfus was gradually stylized into a kind of icon of the republic. Since 1988 he has a monument in the Jardin des Tuileries . A commemorative plaque is attached to his house. There is also a memorial plaque in the Blücher barracks in Kladow in Berlin .

On July 12, 2006, the 100th anniversary of his rehabilitation , a commemorative ceremony was held in the Paris Military School, at which President Jacques Chirac was the keynote speaker and accompanied by the Prime Minister and four other Ministers Dreyfus “the solemn homage to the nation” (French. l'hommage solennel de la Nation ).

The transfer of Dreyfus' remains to the Panthéon, which has been proposed on various occasions, has not yet taken place.

Dreyfus in literature and film

As early as 1913, Roger Martin du Gard , who later won the 1937 Nobel Prize for Literature, took up the Dreyfus affair. In his novel Jean Barois he describes a. a. how Dreyfus disappointed his sympathizers during the second trial with his "unheroic" apathy. In Germany, Rolf Schneider dealt with the case in his 1991 novel Süß und Dreyfus . The Israeli poet Joshua Sobol wrote the play "I Am Not Dreyfus, Or Am I" [Ani Lo Dreyfus] in 2008. The British writer Robert Harris described the affair in his 2013 novel An Officer and Spy (German title: Intrige ) from the point of view of the secret service officer Picquart.

The Dreyfus Affair also provided the template for numerous film adaptations, including a .:

- 1930: Dreyfus - Director: Richard Oswald

- 1991: Prisoners of Honor - Director: Ken Russell

- 1994: Dreyfus Affair (L'affaire Dreyfus) - Director: Yves Boisset - two-part television dramatization

- 1998: J'accuse - I accuse (J'accuse) - Director: Robert Bober , Pierre Dumayet

- 2019: Intrige (J'accuse) - Director: Roman Polanski , based on the novel by Robert Harris

In 1937, under the direction of Wilhelm Dieterle, the biopic The Life of Emile Zola with Paul Muni in the title role was created. The affair takes up a lot of space in it, but the film largely excludes its anti-Semitic aspects. Joseph Schildkraut received an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Alfred Dreyfus.

Works

- Cinq années de ma vie 1894-1899. Eugène Fasquelle, Paris 1901 (frequent new editions; German: Five years of my life 1894–1899 , John Edelheim, Berlin 1901, new edition 2019: ISBN 978-3-945831-17-5 ).

literature

- Hannah Arendt : Elements and origins of total domination. Anti-Semitism, imperialism, total domination. 7th edition. Piper, Munich / Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-492-21032-5 , therein Chapter I, Section 4: The Dreyfus Affair , pp. 212-272; first German edition: 1986, English original edition: The Origins of Totalitarism. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York 1951.

- Louis Begley : The Dreyfus Case, Devil's Island, Guantanamo, History's Nightmare. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-518-42062-1 .

- Jean-Denis Bredin : L'Affaire. Paris, 1983, also Engl. Version available: L'affaire Dreyfus , 1998 (lawyer, level of knowledge from the 1980s).

- Yvonne Domhardt: Alfred Dreyfus - degraded - deported - rehabilitated. Hentrich and Hentrich Verlag, Teetz 2005, ISBN 3-933471-86-9 .

- Vincent Duclert: The Dreyfus Affair. Military mania, hostility to the republic, hatred of Jews. Translated from from the French by Ulla Biesenkamp, Wagenbach, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-803-12239-2 (often indulges in speculation).

- Vincent Duclert: L'honneur d'un patriote. Fayard, Paris 2006 (French, most extensive biography to date, but no new findings).

- Ruth Harris: The Man on Devil's Island. Alfred Dreyfus and the Affair that divided France. Penguin Books, London 2011, ISBN 978-0-14-101477-7 .

- Robert Harris : Intrigue. Heyne-Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-453-43800-2 .

- Elke-Vera Kotowski , Julius H. Schoeps (Eds.): J'accuse…! - … I accuse! About the Dreyfus affair. Catalog accompanying the traveling exhibition in Germany May to November 2005. A documentation. Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, Potsdam 2005, ISBN 3-935035-76-4 .

- Siegfried Thalheimer : The Dreyfus Affair. dtv, Munich 1963.

- George R. Whyte : The Dreyfus Affair. The power of prejudice. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-631-60218-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Alfred Dreyfus in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Alfred Dreyfus in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Gabriel Eikenberg: Alfred Dreyfus. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Dreyfus on Devil's Island , La détention d'Alfred Dreyfus à l'Ile du Diable, online dossier of the Archives nationales d'outre-mer , ANOM, in Aix-en-Provence . Documents via the link at the bottom right (link difficult to see). In French

Individual evidence

- ^ Melvyn Bragg: In Our Time . BBC Radio 4, October 8, 2009. Robert Gildea, Professor of Modern History at Oxford University; Ruth Harris, Lecturer (Modern History) at Oxford University; Robert Tombs, Professor of French History at Cambridge University.

- ↑ Harris, pp. 62-63

- ^ Harris, p. 62

- ↑ Feix, Gerhard: The great ear of Paris - cases of the Sûrete . Verlag Das Neue Berlin, Berlin, 1975, pp. 167–178, DNB 200717472 .

- ^ Harris, p. 36

- ↑ a b Harris, p. 37

- ↑ Harris, pp. 37-39

- ↑ a b c Harris, p. 39

- ^ Harris, p. 41

- ↑ Harris, pp. 39-41

- ↑ Stefan Zweig: The world of yesterday. Insel, Berlin 2014 3 , p. 127ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dreyfus, Alfred |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French officer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 9, 1859 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mulhouse |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 12, 1935 |

| Place of death | Paris |