The German Imperium

|

German Empire German Empire 1871-1918 |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Constitution | Constitution of the German Reich of April 16, 1871 | ||||

| official language | German | ||||

| capital city | Berlin | ||||

| form of government | federal hereditary monarchy | ||||

|

System of Government – 1871 to 1918 – 1918 |

constitutional monarchy parliamentary monarchy |

||||

|

Head of State - 1871 to 1888 - 1888 - 1888 to 1918 |

German Emperor, King of Prussia Wilhelm I Friedrich III. William II |

||||

|

Prime Minister - 1871 to 1890 - 1890 to 1894 - 1894 to 1900 - 1900 to 1909 - 1909 to 1917 - 1917 - 1917 to 1918 - 1918 |

Imperial Chancellor Prince Otto von Bismarck Leo Count of Caprivi Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst Prince Bernhard von Bülow Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg Georg Michaelis Georg Count von Hertling Prince Max von Baden |

||||

|

Area – 1910 |

540,858 km² (excluding colonies ) |

||||

|

Population – 1871 (Dec 1) – 1890 (Dec 1) – 1910 (Dec 1) |

41,058,792 49,428,470 (excluding colonies) 64,925,993 (excluding colonies) |

||||

|

Population density - 1871 - 1890 - 1910 |

76 inhabitants per km² 91 inhabitants per km² 120 inhabitants per km² |

||||

| currency | 1 mark = 100 cents | ||||

|

Incorporation – January 1, 1871 – January 18, 1871 |

Entry into force of the new constitution Proclamation of the Emperor |

||||

| national anthem |

No imperial hymn: heal in the victor's wreath |

||||

| national holiday | unofficially 2 September ( Sedantag ) | ||||

|

Time zone - 1871 to 1893 - 1893 to 1918 |

no uniform time zone CET |

||||

|

License plates - 1871 to 1907 - 1907 to 1918 |

no uniform regulation D |

||||

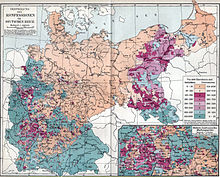

| map | |||||

German Empire is the retrospective designation for the phase of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918 to clearly distinguish it from the period after 1918. In the German Empire, the German nation state was a federally organized constitutional monarchy .

The German Empire was founded when the new constitution came into effect on January 1, 1871. It was staged by a less spectacular, secretly prepared military-court ceremonial, the imperial proclamation of the Prussian King Wilhelm I on January 18, 1871 in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles . Meanwhile, the Empire was still in the Franco-Prussian War . A German national state was created for the first time on a Kleindeutsch basis and under the rule of the Prussian Hohenzollerns . The main residence of the German Emperor and Prussian King was the Berlin Palace .

During the time of the German Empire, Germany was economically and socially characterized by high industrialization . Economically and socio-structurally, it began to change from an agricultural to an industrial country, especially in the last decades of the 19th century . The service sector also gained increasing importance with the expansion of trade and banking. The economic growth, which was also caused by the French war reparations after 1871, was temporarily slowed down by the so-called founder's crash of 1873 and the long-term economic crisis that followed. Despite significant political consequences, this did not change anything in the structural development towards an industrial state.

Characteristic of the social change was a strongly internationally oriented reform movement, in the course of which the social question was pushed forward with poverty scandalization and poverty fight, women demanded improved educational opportunities and the right to vote . In addition to mass politicization, the structural basis of these changes was rapid population growth , internal migration and urbanization . The social structure was significantly changed by the increase in the urban working population and - especially in the years from about 1890 - also the new middle class of technicians, employees and small and medium-sized civil servants. On the other hand, the economic importance of crafts and agriculture - based on their contributions to national income - tended to decline.

Until 1890, domestic and foreign policy developments were determined by the first and longest-serving chancellor of the empire, Otto von Bismarck . His reign can be divided into a relatively liberal phase, characterized by domestic political reforms and the Kulturkampf , and a more conservative period after 1878/79. The transition to state interventionism ( protective tariffs , social security ) and the Socialist Law are seen as turning points .

In terms of foreign policy, Bismarck attempted to secure the empire with a complex system of alliances (e.g. dual alliance with Austria-Hungary in 1879). From 1884 began the - later intensified - entry into overseas imperialism . International conflicts of interest with other colonial powers followed, most notably the world power Great Britain .

The phase after the Bismarck era is often referred to as the Wilhelmine era , because Kaiser Wilhelm II (from 1888) personally exercised considerable influence on day-to-day politics after Bismarck was dismissed. Other, sometimes competing, players also played an important role. They influenced the emperor's decisions, often making them seem contradictory and unpredictable.

Public opinion also gained weight through the rise of mass associations and parties and the growing importance of the press . Last but not least, the government tried to increase its support among the population with an imperialist world policy, an anti-social democratic collection policy and a popular naval armament (see naval laws ). In terms of foreign policy, however, Wilhelm's striving for world power led to isolation; through this policy the empire contributed to increasing the danger of the outbreak of a major war. When World War I finally broke out in 1914, the Reich was embroiled in a multi-front war. The military also gained influence in domestic politics. With the increasing number of war casualties on the fronts and the social hardship at home (encouraged by Allied naval blockades ), the monarchy began to lose support.

It was not until the end of the war that the October reforms of 1918 came about, which stipulated, among other things, that the Reich Chancellor had to have the confidence of the Reichstag . The republic was proclaimed soon afterwards in the November Revolution , and the constituent national assembly in Weimar constituted the Reich as a parliamentary democracy in 1919 . Under international law, today's Germany is identical to the German Reich of 1871, even if the form of government and administrative area have changed several times since then.

prehistory

Up to the founding of the nation state, German history in the 19th century was characterized by numerous political and territorial changes, which entered a new phase after the end of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1806. The Old Empire , a pre-national and supranational entity led by the Roman-German emperors – from the mid-18th century increasingly shaped by the conflicting interests of its two great powers , Austria and the up-and-coming Prussia – broke up as a result of the Napoleonic Wars and the founding initiated by France of the Rhine Confederation .

The ideas of the French Revolution between 1789 and 1799 and the wars of liberation directed against the subsequent hegemonic policy of Napoleon Bonaparte led to nation state movements in almost all of Europe , including the German-speaking area, with the idea of the nation as the basis for state formation. A unified empire including the German settlement areas of the Austrian , Prussian and Danish empires was described as the Greater German solution , and a German Empire without Austria under Prussian leadership as a small German solution .

However, after the European powers opposed to France (Great Britain, Prussia, Russia and Austria in the lead) defeated the armies of Napoleon, the German princes had no interest in a central power that would limit their own rule. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, only the German Confederation was founded, a loose association of those areas that had belonged to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation before 1806. The era that followed the Congress of Vienna, later known as the Vormärz era, was shaped by the policy of restoration , which was dominated by the Austrian state chancellor Clemens Wenzel Fürst von Metternich . As part of the so-called Holy Alliance , an alliance initially formed between Austria , Prussia and Russia , the restoration was intended to restore the balance of power in Europe, both domestically and internationally, which had prevailed in the Ancien Régime up until the French Revolution.

Nation- state and bourgeois-democratic movements opposed the policy of the Restoration. In the year of revolution 1848 in large parts of Central Europe, the March Revolution in the German states was also included in the revolutionary movement. Members of the first all-German, democratically elected parliament that then emerged, the Frankfurt National Assembly , offered the German imperial crown to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV as part of the Little Germany solution after the Paulskirche constitution had been passed. However, because he refused, citing his “right of God ”, the attempt to unify the majority of the German states on a constitutional basis failed.

After the violent suppression of the revolutionary movement in 1848/49, the German Confederation continued to exist until 1866. After a decade of political reaction ( reaction era ), in which democratic and liberal aspirations were again suppressed, the first political parties as we know them today were formed in the German states at the beginning of the 1860s . The relationship between Austria and Prussia was characterized by cooperation in the 1850s, and then by rivalry again. Different ideas emerged, for example, at the Frankfurt Princes ' Day in 1863: Austria and the central states such as Bavaria wanted to expand the German Confederation into a confederation of states, while Prussia preferred a federal solution. In the German-Danish War of 1864, the two great powers worked together again, but then fell out over the spoils of Schleswig-Holstein .

Prussian provocation (the invasion of Austrian-administered Holstein) triggered the German War of Prussia against Austria in 1866 , in which the armies of Prussia and some northern German states fought alongside Italy against the troops of Austria, which shared with the southern German states, including Baden , Bavaria , Hesse and Württemberg , was allied. After the defeat, Austria had to recognize the dissolution of the German Confederation and accept that Prussia founded the North German Confederation with the states north of the Main line , initially as a military alliance . This received a federal constitution in 1867 . The southern German states, previously allied with Austria, concluded protective and defiant alliances with Prussia.

The Franco-Prussian War began in 1870, triggered by a diplomatic dispute over the Spanish succession . The declaration of war came from the French side after the Prussian Prime Minister Bismarck had exposed France politically. The southern German states took part in the war and joined the North German Confederation on January 1, 1871. The three wars between 1864 and 1871 are also known as the German wars of unification .

Empire founding

The German victory at Sedan and the capture of the French Emperor Napoleon III. (both on September 2, 1870) paved the way for the founding of the empire. Bismarck began negotiating with the southern German states. This meant the accession of Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden to the North German Confederation through the establishment of a new "German Confederation" agreed in November 1870. Other plans, such as a double alliance, as proposed by Bavaria , now stood no chance. On the one hand, Bismarck's solution guaranteed Prussia's dominance in the new, so-called second German Reich . On the other hand, the monarchical federalism meant a barrier against tendencies towards parliamentarization .

Demands were made in the German public for an annexation of Alsace and parts of Lorraine , and Bismarck embraced these demands. This prolonged the war, was one reason for the intensification of the " Franco-German hereditary enmity " (see also French revanchism ) and gave national enthusiasm in Germany a further boost. The latter facilitated Bismarck's negotiations with the southern German states, which resulted in the November treaties.

Nevertheless, he had to make concessions, the so-called reservation rights . Thus Bavaria retained its own army ( Bavarian Army ) in peacetime. Moreover, like Württemberg, it retained its own postal service. The southern German states as a whole retained their state railways ( Royal Bavarian State Railways , Royal Württemberg State Railways , Grand Ducal Baden State Railways , Grand Ducal Hessian State Railways ). In foreign policy they successfully insisted on their own diplomatic relations .

The Prussian king, holder of the Federal Presidium , received the additional title " German Emperor ". This designation was of subordinate constitutional importance, but of considerable symbolic importance - the memory of the Old Kingdom made it easier to identify with the new state. In order to emphasize the monarchical legitimacy of the nation state , it was important to Bismarck that King Ludwig II, as the monarch of the largest accession country , should offer the imperial crown to King Wilhelm I. After agreeing to improve his private treasury, the reluctant but politically isolated Bavarian king agreed to take this step and proposed King Wilhelm as German emperor in Bismarck's letter of 30 November 1870. The secret annual donations that Bismarck diverted from the Guelph fund for Ludwig totaled 4 to 5 million marks. Characteristic of the character of the new empire was that the representatives of the North German Reichstag had to wait until the federal princes had declared their consent to the imperial dignity. Only then could the deputies ask the king to accept the imperial crown . This was in marked contrast to the Kaiserdeputation of 1849.

King Wilhelm himself, who – not without reason – feared that the new title would cover up the Prussian royal dignity, remained opposed for a long time. If anything, he demanded the title of "Kaiser von Deutschland". Bismarck warned that the southern German monarchs were unlikely to accept this. In addition, the constitutional title has been “German Emperor” since January 1st. At the Kaiser proclamation on January 18, Wilhelm allowed the Grand Duke of Baden to cheer “Kaiser Wilhelm”.

The first Reichstag elections then took place on March 3, 1871 . The first constituent session of the Reichstag took place on March 21 in the Prussian House of Representatives in Berlin , which was declared the capital of the Reich . Thereafter, the constitution of January 1, 1871 was revised and passed on April 16; it is usually meant when the "Bismarckian Imperial Constitution" is mentioned.

The Peace of Frankfurt officially ended the Franco-Prussian War. The signing took place on May 10th. The Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine was annexed to the German Reich and was directly subject to the German Emperor. The victory of Prussia and the allied German states and the founding of the Reich were celebrated on June 16, 1871 with a pompous victory parade in Berlin and other German cities. The Reichsmünzgesetz unified the German currencies, the Mark was introduced in 1876 as a uniform currency in the Reich and replaced the previous means of payment of the individual states . The new mark currency was based on the gold standard .

structure of the empire

area breakdown

The Empire included 25 federal states (federal members) - including the three republican Hanseatic cities of Hamburg , Bremen and Lübeck - as well as the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine .

| state | form of government | capital city | Area in km² (1910) | Population (1871) | Population (1900) | Residents (1910) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Prussia | monarchy | Berlin | 348,780 | 24.691.085 | 34.472.509 | 40.165.219 |

| Kingdom of Bavaria | monarchy | Munich | 75,870 | 4,863,450 | 6,524,372 | 6,887,291 |

| Kingdom of Wuerttemberg | monarchy | Stuttgart | 19,507 | 1,818,539 | 2,169,480 | 2,437,574 |

| Kingdom of Saxony | monarchy | Dresden | 14,993 | 2,556,244 | 4,202,216 | 4,806,661 |

| Grand Duchy of Baden | monarchy | Karlsruhe | 15,070 | 1,461,562 | 1,867,944 | 2,142,833 |

| Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | monarchy | Schwerin | 13.127 | 557,707 | 607,770 | 639,958 |

| Grand Duchy of Hesse | monarchy | Darmstadt | 7,688 | 852,894 | 1,119,893 | 1,282,051 |

| Grand Duchy of Oldenburg | monarchy | Oldenburg | 6,429 | 314,591 | 399,180 | 483,042 |

| Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach | monarchy | Weimar | 3,610 | 286,183 | 362,873 | 417,149 |

| Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz | monarchy | Neustrelitz | 2,929 | 96,982 | 102,602 | 106,442 |

| Duchy of Brunswick | monarchy | Brunswick | 3,672 | 312,170 | 464,333 | 494,339 |

| Duchy of Saxe-Meiningen | monarchy | Meiningen | 2,468 | 187,957 | 250,731 | 278,762 |

| Duchy of Anhalt | monarchy | dessau | 2,299 | 203,437 | 316,085 | 331.128 |

| Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | monarchy | Coburg / Gotha | 1,977 | 174,339 | 229,550 | 257,177 |

| Duchy of Saxe-Altenburg | monarchy | Altenburg | 1,324 | 142.122 | 194,914 | 216,128 |

| Principality of Lippe | monarchy | Detmold | 1.215 | 111.135 | 138,952 | 150,937 |

| Principality of Waldeck | monarchy | arolsen | 1.121 | 56,224 | 57,918 | 61,707 |

| Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt | monarchy | Rudolstadt | 941 | 75,523 | 93,059 | 100,702 |

| Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen | monarchy | Sondershausen | 862 | 67.191 | 80,898 | 89,917 |

| Principality of Reuss younger line | monarchy | Gera | 827 | 89,032 | 139,210 | 152,752 |

| Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe | monarchy | Buckeburg | 340 | 32,059 | 43.132 | 46,652 |

| Principality of Reuss older line | monarchy | greece | 316 | 45,094 | 68,396 | 72,769 |

| Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg | republic | Hamburg | 414 | 338,974 | 768,349 | 1,014,664 |

| Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck | republic | Luebeck | 298 | 52,158 | 96,775 | 116,599 |

| Free Hanseatic City of Bremen | republic | Bremen | 256 | 122,402 | 224,882 | 299,526 |

| Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine | monarchy | Strasbourg | 14,522 | 1,549,738 | 1,719,470 | 1.874.014 |

| Deutsches Reich | monarchy | Berlin | 540,858 | 41,058,792 | 56.367.178 | 64,925,993 |

Geographic-political situation in Central Europe

The Empire had eight neighboring states:

In the north it bordered on Denmark (77 km), in the northeast and east on the Russian Empire (1,322 km), in the southeast and south on Austria-Hungary (2,388 km), in the south on Switzerland (385 km), in the southwest France (392 kilometers), to the west by Luxembourg (219 kilometers) and Belgium (84 kilometers), and to the north-west by the Netherlands (567 kilometers). The border length totaled 5,434 kilometers (excluding the border in Lake Constance ).

Since the beginning of the 19th century, this position has been characterized as the “middle position” in Europe in the German debate about the supposed “naturalness” of historically determined borders and spaces of a nation. This discussion also continued during the Kaiserreich and is still represented today, such as the publicist Joachim Fest :

“Germany's destiny is the middle position in Europe. Either it is threatened by all its neighbors, or it is threatening all its neighbors.”

symbols of the empire

The German Empire did not have an official national anthem . The songs Heil dir im Siegerkranz , the melody of which is identical to the British national anthem , as well as Die Wacht am Rhein and the Lied der Deutschen were considered as replacements .

According to Art. 55 RV, black, white and red were the colors of the naval flag and the merchant flag . They date from the time of the North German Confederation. The colors are made up of the colors of Prussia ( black and white ) and those of the free and Hanseatic cities (white over red). Only in 1892 was black, white and red made the national flag by the highest decree .

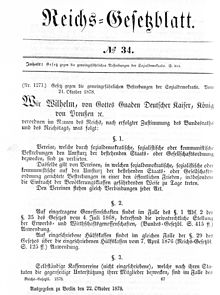

Constitution

The constitution of the German Reich of April 16, 1871 emerged from the constitution of the North German Confederation drawn up in 1866 ; Otto von Bismarck had decisively shaped it and tailored it to himself. On the one hand, it was an organizational statute that mutually delimited the competences of the state organs through which the Reich acted and other institutions of the Reich. On the other hand, it determined the jurisdiction of the Reich in relation to the federal states. Here it followed the principle of limited individual authority: the Reich was only allowed to take action for those matters that were expressly assigned to the Reich in the constitution as responsibility. Otherwise, the states were responsible.

The Imperial Constitution does not have a section on fundamental rights that would have legally defined the relationship between subjects (citizens) and the state with constitutional status. Only a ban on discrimination based on citizenship of a federal state (equal treatment for nationals) was standardized. The missing section on fundamental rights did not necessarily have to have a negative effect. Because the federal states generally implemented the imperial laws, only they intervened in the law against the citizen. The decisive factor was therefore whether and which basic rights were provided for in the state constitutions. For example, the constitution of January 31, 1850, applicable to the Prussian state , contained a catalog of basic rights.

According to its constitution, the German Reich was an “eternal federation” of federal princes. This corresponded to the fact that the German Reich was a federal state . Its constituent states had distinctive autonomy, with them also having an important shaping function at the Reich level through the Federal Council . The Bundesrat was intended by the constitution to be the real sovereign of the Reich. Its powers were both legislative and executive in nature. Realpolitik, however, its importance as an independent center of power remained limited for various reasons. One aspect was that Prussia, as the largest federal state, had only 17 out of 58 votes, but the small states of northern and central Germany almost always supported the Prussian vote.

The King of Prussia formed the presidium of the federation and bore the title of German Emperor. The Emperor was entitled to considerable powers that went far beyond what the term Presidium of the Federation would suggest. He appointed and dismissed the Reich Chancellor and the Reich officials (particularly the Secretaries of State). Together with the Reich Chancellor, who was usually also Prussian Prime Minister and Prussian Foreign Minister, he determined the foreign policy of the Reich. The Kaiser was supreme in command of the navy and the German army (the Bavarian army only in times of war). In particular, the constitution provided that the emperor, if necessary, could restore internal security with the help of the army. This concentration of command was often used as a means of pressure in domestic politics. The southern German kingdoms of Württemberg and Bavaria reserved reservation rights during the constitutional negotiations . However, the power of neither the Prussian king nor the German emperor was absolute, but they stood in the tradition of German constitutionalism of the 19th century, albeit with elements that stood outside of the constitution.

In this power structure, the Reich Chancellor was the Reich Minister responsible to the Kaiser, who was responsible for the State Secretaries. He chaired the Bundesrat, headed the Reich administration and was usually Prussian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister at the same time. The democratic deficit of this constitution was primarily due to the lack of parliamentary responsibility for the Reich Chancellor, who the Reichstag could neither elect nor overthrow. It was not until October 1918 that the Reich Chancellor's parliamentary responsibility was introduced as part of the October Constitution .

The real counterweight to the allied governments, the Federal Council and the Reich leadership was the Reichstag . The suffrage provided for universal and equal suffrage for males aged 25 and over (in the form of first-past-the-post suffrage). In principle the election was secret, although not necessarily in practice. In comparison with other European states, but also with the right to vote in many federal states , this was a special democratic feature of the imperial constitution.

The legislative period of the Reichstag initially lasted three years, after 1888 five years. With the Emperor's consent, the Federal Council could dissolve Parliament at any time and call for new elections; in reality, the initiative for the dissolution came from the chancellor. MPs received no diets as a counterweight to universal suffrage . The deputies had a free mandate and, according to the constitution, were not bound by the orders of the voters. In fact, there were numerous "wild deputies" in the first legislative periods. In practice, of course, the formation of factions quickly continued to prevail.

The Reichstag was an equal body with the Bundesrat when it came to passing laws. This central parliamentary right was of growing importance in the age of legal positivism , since government action was essentially based on laws. After the development of the doctrine of the reservation of statutes , government regulations only played a role after parliamentary authorization. Administrative directives only had an effect within the administration. The second core competence of Parliament was the adoption of the budget in the form of a law. The budget debate quickly developed into a general debate on all government action. However, the possibility of deciding on the military budget, which was the main expenditure item of the empire, was limited. By 1874 the budget was fixed anyway, and later the Septennate and later the Quinquennate limited parliamentary rights in this area. The Reichstag had the legislative initiative, i.e. the right to propose possible new laws, just like the Reich Chancellor.

The political leadership of the Reich was therefore dependent on cooperation with the Reichstag. Contrary to what the preamble to the constitution suggested, the empire was by no means a “federation of princes”. Rather, the constitution represented a compromise between the national and democratic demands of the aspiring business and educated middle classes and the dynastic structures of rule ( constitutional monarchy ), or a compromise between the unitarian principle, embodied by the emperor and the Reichstag, and the federal principle with the Federal Council as representation of the member states.

power centers of the empire

The constitutional order was an important framework for the actual order of government. In fact, the institutions anchored in Bismarck's imperial constitution, such as the Reichstag or the chancellor, were of central importance to the political system. In addition, there were other centers of power that were only partially reflected in the written constitution.

bureaucracy and administration

Bureaucracy, for example, was hardly mentioned in the constitution. The bureaucratic apparatus ensured continuity in all domestic political conflicts. At the same time, the political decision-makers - including the Chancellor and the Emperor - had to reckon with the weight of the higher officials. However, the Reich itself had only a modest apparatus at the beginning and was dependent on the support of the Prussian ministries for a long time.

There was no real imperial government alongside the imperial chancellor. Instead of ministers, there were only a number of state secretaries reporting to the chancellor, who presided over imperial offices. In the course of time, in addition to the Reich Chancellery , a Reich Railway Office , a Reich Post Office , a Reich Justice Office , a Reich Treasury , a Ministry for Alsace-Lorraine , the Foreign Office , the Reich Office of the Interior , a Reich Navy Office and finally a Reich Colonial Office were created . The administrative dependency on Prussia decreased with the expansion of the imperial administration. Until the end, however, the organizational connection between Prussia and the Reich was of great importance.

Protestants as well as members of the nobility were over-represented in the higher positions, including in the higher imperial administration. Thus, out of a total of 31 Reich State Secretaries , twelve belonged to the nobility and in 1909 71% were of the Protestant denomination. Politically, however, these were initially relatively liberal in orientation. Only a long-term youth policy ensured a conservative orientation of the higher officials in the long term.

monarchy and court

The constitution guaranteed the emperor considerable freedom of action. The various imperial advisory bodies such as the civil , military and naval cabinets played important roles in the decisions of the monarchs. Added to this were the court and the close personal confidants of the emperors. As early as Wilhelm I, the monarch exerted considerable influence on personnel policy, without usually intervening in day-to-day business. This level was one of the central centers of power in the empire, especially under Kaiser Wilhelm II with his claim to a “ personal regiment ”.

The change of the emperor from a presidency of the federation to an imperial monarch should also hardly be underestimated. Outside of Prussia, not only the commemoration days of the various dynasties were celebrated, but also the Kaiser's birthday . The emperor increasingly became a symbol of the empire. The question of the extent to which Kaiser Wilhelm II was actually able to enforce a personal regime is, of course, controversial in historical scholarship. In the years after 1888, Hans-Ulrich Wehler sees more of an authoritarian polycracy in which, in addition to the “ brambling but weak” Kaiser, the Reich Chancellor, Alfred von Tirpitz as State Secretary of the Reich Navy Office, the General Staff, the bureaucrats of the Reich offices and the representatives of the various economic interests wrestled with each other over the basic lines of Reich politics.

It is undisputed that the imperial influence was still limited until 1897, while the importance of the emperor increased significantly until 1908, only to then lose importance again. The affair surrounding the confidante of Emperor Philipp zu Eulenburg contributed to this . This and the ensuing Daily Telegraph scandal contributed to the decline in the public image of the emperor, but not of the monarchy as an institution.

military

Kluck , Emmich (upper left and right corners);

Bülow , Crown Prince Rupprecht , Crown Prince Wilhelm , Duke Albrecht , Heeringen (1st row);

François , Beseler , Hindenburg , Stein (2nd row);

Tirpitz , Prince Heinrich (3rd row);

Lochow , Haeseler , Woyrsch , Einem (4th row);

Mackensen , Ludendorff , Falkenhayn , Zwehl (5th row)

Apart from the approval of the necessary financial resources, the army and the navy remained largely under the control of the Prussian king and emperor, respectively. The limits of the seemingly absolutist “command authority” were hardly defined. It therefore remained one of the central pillars of the monarchy. Below the “supreme warlord” there were three institutions, the military cabinet , the Prussian Ministry of War and the General Staff, which at times competed with one another over competences. In particular, the General Staff under Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke and later Alfred von Waldersee tried to influence political decisions. The same applies to Alfred von Tirpitz on naval matters.

The army was not only directed against external enemies, but should also be used internally, for example in the event of strikes , according to the will of the military leadership . In practice, the army was hardly used in the big strikes. Nevertheless, as a potential threat, the army represented a domestic political power factor that should not be underestimated.

The close ties with the monarchy were initially reflected in the officer corps , which was strongly characterized by aristocracy . Even later, the nobility retained a strong position among the leading ranks, although in the middle ranks, with the enlargement of the army and the navy, the bourgeois portion penetrated more strongly. However, the appropriate selection and the internal socialization in the military ensured that the self-image of this group hardly differed from that of their noble comrades.

Militarism in Germany intensified. Between 1848 and the 1860s, society tended to view the military with suspicion. This changed fundamentally after the victories from 1864 to 1871. The military became a central element of the emerging imperial patriotism . Criticism of the military was considered unpatriotic. Nevertheless, the parties did not support an enlargement of the army indefinitely. It was only in 1890, with a peacetime presence of almost 490,000 men, that the military reached its constitutional strength of one percent of the population. In the years that followed, the land forces were further reinforced. Between 1898 and 1911, costly naval armaments required restrictions on the land army. During this time, the General Staff itself had opposed an increase in troop strength because it feared that the bourgeois element would be reinforced at the expense of the aristocratic element in the officer corps. In 1905, the Schlieffen Plan was the concept for a possible two-front war against France and Russia, taking into account England's participation on the enemy's side. After 1911 rearmament was intensively pursued. Ultimately, the number of troops required to carry out the Schlieffen Plan was not reached.

During the Empire, the army gained a very strong social significance. The officer corps was considered by large parts of the population to be the "first class in the state". Its world view was characterized by loyalty to the monarchy and the defense of royal rights, it was conservative, anti-socialist and fundamentally anti-parliamentary. The military code of conduct and honor extended far into society. For many citizens, too, reserve officer status now became a desirable goal.

The military was undoubtedly also important for internal nation-building. The shared service promoted the integration of the Catholic population into the Protestant-dominated empire. Even the workers were not immune to the military's broadcasts. Military service , which lasted at least two years (three years for the cavalry), as the so-called “school of the nation”, played a formative role. However, because of the oversupply of conscripts in Germany, only half of those born did active military service. Highly educated conscripts—almost exclusively members of the middle and upper classes—were privileged to do short-term military service as one-year volunteers .

Heinrich Mann's Untertan , the Hauptmann von Köpenick or the Zabern Affair reflect the importance of militarism in German society. Everywhere in the empire the new warriors' associations became the bearers of a militaristic worldview. The number of 2.9 million members in the Kyffhäuser League (1913) shows the widespread effect this had . The Bund was thus the strongest mass organization in the Reich. The associations sponsored by the state were supposed to cultivate military, national and monarchical sentiments and immunize the members against social democracy.

population, economy and society

The period of the German Empire saw fundamental demographic, economic and social changes that also had a significant impact on culture and politics. A characteristic of this was the enormous growth in population . In 1871 there were 41 million inhabitants in the Reich, in 1890 there were over 49 million and in 1910 almost 65 million inhabitants. Not least due to internal migrations - initially from the surrounding area, later also due to long-distance migrations, for example from the agricultural Prussian eastern areas to Berlin or western Germany - the urban population, especially the large city population, grew strongly. In 1871, 64% of the population still lived in communities with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants and only 5% in large cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants, by 1890 there was already equality between city and country dwellers. In 1910 only 40% lived in communities with less than 2000 inhabitants and 21.3% in large cities. This was also associated with a change in lifestyle. For example, life in the tenements in Berlin was fundamentally different from life in the village.

This change was only possible because there were a few prerequisites:

- the economy was able to provide enough jobs

- banking, and especially the big universal banks, had evolved and grown

- Transport and logistics had made progress (see also History of the railways in Germany ): for example, the Prussian Eastern Railway transported many times the quantity of goods forecast at the time of construction - including large quantities of food - from the countryside to metropolitan areas.

During this period, Germany transitioned from an agricultural country to a modern industrial state (→ high industrialization in Germany ). At the beginning of the empire, railway construction and heavy industry dominated ; later, the chemical industry and the electronics industry were added as new leading sectors. In 1873 the share of the primary sector in the net domestic product was 37.9% and that of industry 31.7%. In 1889 the tie was reached; In 1895, agriculture only accounted for 32%, while the secondary sector accounted for 36%. This change was also reflected in the development of employment relationships. Whereas in 1871 the ratio of those employed in agriculture to those in industry, transport and the service sector was 8.5 to 5.3 million, in 1880 the ratio was 9.6 to 7.5 million and in 1890 9.6 to 10 million. In 1910, 10.5 million people were employed in agriculture, while 13 million were employed in industry, transport and the service sector.

| economic sector | 1882 | 1895 | 1907 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 41.6 | 35.0 | 28.4 |

| Industry/Craft | 34.8 | 38.5 | 42.2 |

| trade/traffic | 9.4 | 11.0 | 12.9 |

| domestic services | 5.0 | 4.3 | 3.3 |

| public service/professions | 4.6 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

| unemployed/pensioners | 4.7 | 6.1 | 8.1 |

From a socio -historical point of view, the Kaiserreich was shaped above all by the rise of the working class. The different groups of origin, consisting of unskilled workers, semi-skilled workers and skilled workers, tended to develop a specific self-image of the working-class population, despite all the differences that still existed, through shared experiences at the workplace and in the living quarters. With the emergence of large companies, new state services and the increase in trade and transport, the number of employees and small and medium-sized civil servants also increased. These paid attention to social distance from the workers, even if their economic situation differed little from that of industrial workers.

The old urban middle classes were among the stagnant parts of society. Craftsmen often felt their existence threatened by industry. The reality, however, was different: there were overstaffed traditional trades; on the other hand, construction and food crafts benefited from the growing population and urban development. Many professions adapted to developments, for example the shoemakers no longer made shoes, but only repaired them.

The bourgeoisie largely succeeded in enforcing its cultural norms, with the business bourgeoisie (including the big industrialists ) being the economic leaders and the educated bourgeoisie making Germany a center of science and research. Nevertheless, the political influence of the bourgeoisie remained limited, for example due to the peculiarities of the political system and the rise of the workers and the new middle classes.

Economically, the existence of the landowning nobility was threatened, especially in East Elbia , by the increasing international integration of the agricultural market. The demands of the nobility and agricultural interest groups for state aid became a feature of domestic politics during the imperial period. At the same time, the Prussian constitution ensured that the nobility retained numerous special rights in the largest state in the empire. The nobility was also able to maintain its influence in the military, diplomacy and bureaucracy.

cities

The largest cities of the empire were:

denominations and national minorities

Confessional differences have changed less than the economy and society during this time. But they were also important for the overall history of the empire. The same applies to the contradiction between the claim to be a nation state and the existence of numerically significant national minorities.

Denominations and Churches in the Empire

There was basically little change in the general distribution of denominations in the early modern period . Furthermore, there were almost purely Catholic areas ( Lower and Upper Bavaria , northern Westphalia , Upper Silesia and others) and almost purely Protestant (Schleswig-Holstein, Pomerania, Saxony, etc.). The denominational prejudices and reservations, especially towards mixed denominational marriages, were therefore still significant. Gradually, internal migration led to a gradual denominational mixing. In the eastern areas of the empire, there was often also a national difference, since the equation Protestant = German, Catholic = Polish applied to a large extent there. In the immigration areas, for example in the Ruhr area and Westphalia or in some large cities, there were sometimes considerable confessional shifts (especially in Catholic Westphalia due to Protestant immigrants from the eastern provinces).

Politically, the distribution of denominations had significant consequences. In the Catholic-dominated areas, the Center Party managed to win over the vast majority of voters. The Social Democrats and their unions hardly managed to gain a foothold in the Catholic parts of the Ruhr area. Only with increasing secularization in the last decades of the empire did this begin to change.

| area | Protestants | Catholics | Otherwise. Christians | Jews | Other | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | |

| Deutsches Reich | 28.331.152 | 62.63 | 16,232,651 | 35.89 | 78,031 | 0.17 | 561,612 | 1.24 | 30,615 | 0.07 |

| Prussia | 17,633,279 | 64.64 | 9,206,283 | 33.75 | 52,225 | 0.19 | 363,790 | 1.33 | 23,534 | 0.09 |

| Bavaria | 1,477,952 | 27.97 | 3,748,253 | 70.93 | 5.017 | 0.09 | 53,526 | 1.01 | 30 | 0.00 |

| Saxony | 2,886,806 | 97.11 | 74,333 | 2.50 | 4,809 | 0.16 | 6,518 | 0.22 | 339 | 0.01 |

| Wuerttemberg | 1,364,580 | 69.23 | 590,290 | 29.95 | 2,817 | 0.14 | 13,331 | 0.68 | 100 | 0.01 |

| to bathe | 547,461 | 34.86 | 993.109 | 63.25 | 2,280 | 0.15 | 27,278 | 1.74 | 126 | 0.01 |

| Alsace-Lorraine | 305,315 | 19.49 | 1,218,513 | 77.78 | 3,053 | 0.19 | 39,278 | 2.51 | 511 | 0.03 |

Judaism and anti-Semitism

Around 1871, the Jews in the German Empire made up a small percentage of the total population, accounting for just over one percent. Due to a lower number of births and the increasing proportion of Christian-Jewish marriages, in which the children were mostly raised Christian, their share gradually decreased. The Jewish population was concentrated in the larger cities. Around 1910, a third of all German Jews lived in the city of Berlin with surrounding communities, where their share of the population was about 5%. Apart from Berlin, centers of Jewish life were Frankfurt am Main (10%), Breslau (5.5%), Königsberg (Prussia) and Hamburg (3.2%). But there were also rural regions with above-average Jewish populations: in the east the province of Posen , West Prussia and Upper Silesia , in the south-west the Grand Duchy of Hesse , Lower Franconia , the Palatinate (Bavaria) and Alsace-Lorraine .

In the eastern provinces with a mixed German and Polish population, the Jews predominantly identified themselves as German. Even among those Jews who spoke East Yiddish dialects , the tendency to assimilate into German society was strong for a long time. Zionism , which sought to found a national home for the Jews in Palestine, was rejected by the overwhelming majority of German Jews until the end of the German Empire.

In 1893 the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith was founded, and the name of the association was program. The Central-Verein made it its task to combat anti-Semitism, but rejected all ideas of the Jews as a people or a separate race, and regarded the German Jews as one of the German tribes, so to speak. Overall, German Jews were extraordinarily successful in the areas of business, culture, science, and the academic professions. According to statistics from 1910, the Jewish population was 0.95% (615,000 of 64,926,000). Of these, 555,000 were of German origin, the remaining 60,000 (approx. 10%) were non-German nationals (mostly refugees from Poland, Ukraine and Russia). In contrast, 4.28% of the public prosecutors and judges, 6.01% of the doctors, 14.67% of the lawyers and notaries in the German Empire were of Jewish faith. A disproportionately large number of prominent musicians and virtuosos were of Jewish descent. The Jewish contribution was particularly evident in major cities, particularly Berlin . The German Jews thus made an outstanding contribution to global cultural life.

Nevertheless, for various reasons , anti-Semitism was able to gain an administrative, social and political foothold, especially in the later empire under Kaiser Wilhelm II . Certain professions were practically closed to the Jews. Thus it was impossible for a Jew to become an officer (which was a serious limitation, since the officer rank was one of the most prestigious professions in the Empire). For example, in 1907 the Prussian Minister of War Karl von Einem considered "an intrusion of Jewish elements into the active officer corps not only to be harmful, but to be directly fatal". The percentage of Jewish university professors was significantly lower than the percentage of Jewish private lecturers, which was partly an expression of anti-Jewish reservations about appointments to chairs. Leading scholars, while dismissing the anti-Semitic movement as primitive, expressed their distrust of Jewish intrusion into the academic profession and envisioned possible Jewish domination of German universities. Jews were never appointed to a chair in German language and literature or in classical antiquities and languages , and were mainly only employed in the newly developing mathematical and scientific subjects and medicine, where they achieved outstanding results. The later Nobel Prize winner Richard Willstätter later confessed: … the attitude of the faculties made a much deeper and decisive impression on me, namely the frequent cases in which the appointment of Jewish scholars was opposed and prevented, and the way in which this happened. The faculties allowed exceptions, but did not grant equal rights.

Despite the high percentage of Jewish lawyers, higher legal careers were largely closed to them. In particular , judicial offices were only filled with Jews to a limited extent, which was justified by the fact that the judicial office requires special trust and therefore, out of consideration for the feelings of the population, it could not be filled with Jews, and a Jew could hardly take an oath from a Christian. It was very difficult or impossible for Jews to obtain a higher state office. In contrast to Great Britain, where a Christian-baptized Jew - Benjamin Disraeli - even became prime minister, the German Empire had no Jewish minister. Individual Jews who reached a higher state office, such as the director of the colonial department of the Foreign Office , Bernhard Dernburg , remained exceptions. Anti-Semitism spread in the flourishing seaside resorts on the North and Baltic Seas . Anti-Semitic prejudices and caricatures of Jews were to be found in almost all walks of life.

The attitude of the social democratic party was at least ambivalent for a while, since the stereotype of the wealthy capitalist Jew existed there. In principle, anti-Semitism was rejected by the Social Democrats; party chairman August Bebel condemned anti- Semitism as reactionary in a keynote speech on anti-Semitism and social democracy held in 1893. Conservative parties flirted with anti-Semitic program points at times. In its Tivoli program of 1892 , the German Conservative Party turned against “the Jewish influence on our national life, which was pushing ahead and decomposing in many ways” and called for a Christian government and Christian teachers . There were efforts to withdraw the civil equality that Jews had gained in the course of the 19th century. In 1880/81, the anti-Semite petition of the “ Berlin Movement ” demanded that Jews be given equal rights under civil law , but was rejected by the Prussian government and the liberal parties in the Reichstag. Anti-Semitic sentiments and actions that recurred on a regional level, such as those expressed in the Konitz murder affair of 1900-1902, were suppressed by the authorities. As a counter-reaction to anti-Semitism, liberal scholars and politicians (including Theodor Mommsen , Rudolf Virchow , Johann Gustav Droysen ) founded the Association for the Defense of Anti-Semitism (“Defense Association”) in 1890. Politically, the anti-Semites did not succeed in forming a unified party. The share of the votes of the fragmented anti-Semitic parties was at most five and a half percent in all Reichstag elections before the First World War. Political anti-Semitism shifted more to the German Conservative Party, professional associations, student fraternities, and the Christian churches. Leaving aside the liberals, German bourgeois culture had long been steeped in anti-Semitism.

national minorities

| native language | Quantity | portion |

|---|---|---|

| German | 51.883.131 | 92.05 |

| German and a foreign language | 252,918 | 0.45 |

| Polish | 3,086,489 | 5.48 |

| French | 211,679 | 0.38 |

| Masurian | 142,049 | 0.25 |

| Danish | 141.061 | 0.25 |

| Lithuanian | 106,305 | 0.19 |

| Kashubian | 100,213 | 0.18 |

| Wendish (Sorbian) | 93,032 | 0.16 |

| Dutch | 80,361 | 0.14 |

| Italian | 65,930 | 0.12 |

| Moravian | 64,382 | 0.11 |

| Czech | 43.016 | 0.08 |

| Frisian | 20,677 | 0.04 |

| English | 20.217 | 0.04 |

| Russian | 9,617 | 0.02 |

| Swedish | 8,998 | 0.02 |

| Hungarian | 8.158 | 0.01 |

| Spanish | 2,059 | 0.00 |

| Portuguese | 479 | 0.00 |

| other foreign languages | 14,535 | 0.03 |

| Residents on December 1, 1900 | 56.367.187 | 100 |

The German Empire increasingly developed into a unified national state modeled on France and Great Britain. Nevertheless, in 1880, in addition to the almost 42 million German native speakers at the time, there were around 3.25 million non-German speakers, including 2.5 million who spoke Polish or Czech, 140,000 Sorbs , 200,000 Kashubians , 150,000 Lithuanian speakers, 140,000 Danes and 280,000 French native speakers. These mostly lived near the outer borders of the empire.

Not only the government, the chancellor and the emperor, but also the national and liberal-minded bourgeoisie fundamentally advocated a policy of cultural and linguistic Germanization for the formation of a newly defined nation in the heart of Europe. The school played a central role with the consistent use of German-language instruction.

In the competition between the different cultures, but also in accordance with the desire for a German nation that was recognizable both internally and externally, e.g. For example, the Polish pastors in the Prussian state were replaced by secular, German-speaking teachers. The predominantly French-speaking areas of Alsace-Lorraine were an exception, where French was permitted as a school language. The introduction of German as the official and court language was important.

While the Prussian kingdom with its external borders in the east was largely tolerant towards its national minorities before the founding of the empire and had expressly promoted school teaching in the mother tongue, this tolerance increasingly gave way to a policy of cultural nationalization, especially in the Polish-speaking areas. The Polish language, which had been taught in predominantly Polish-speaking areas before the founding of the Reich, was gradually replaced by the German language of instruction. Only Catholic religious instruction could still be given in Polish. When German was introduced as the language of instruction there, too, there was open resistance, which manifested itself in school strikes (1901 Wreschen school strike ), which the Prussian authorities and teachers responded to with disciplinary measures. The measures were sharply condemned by the Social Democrats, the Left Liberals and the Center. In the case of the Polish population, measures were later added to limit large-scale Polish landownership in favor of German settlers. The Prussian Settlement Commission also tried, with little success, to acquire Polish property for German settlers. In 1885, 35,000 Poles were expelled from the Kingdom of Prussia when Poles were expelled. The procedure was initiated by Bismarck and implemented by the Prussian Minister of the Interior, Robert Viktor von Puttkamer .

However, this new policy had only limited success, as it turned against the authorities the Poles, who had previously been able to live quite well with the tolerant attitude of the Prussian state. Despite financial efforts and pithy nationalist speeches (“We are not going back a step here!”), there was rather an increase in the Polish-speaking population and a decrease in the German population, for example in the province of Posen, and increasing alienation between Germans and Poles. The minorities tried to preserve their own identity and successfully organized themselves into farmers' associations, founded credit institutions and aid organizations. All nationalities, for example, were represented relatively stably in the Reichstag and were even overrepresented in number. Even the Poles who emigrated to the Ruhr area stuck to their roots. Strong Polish trade unions emerged there. The anti-Polish measures during the time of the German Empire had an ominous after-effect on German-Polish relations in general. When the Second Polish Republic emerged as an independent state after World War I, most of the former provinces of Poznań and West Prussia became part of Poland. The Polish government now exercised a similarly repressive policy towards the German minorities in these areas, ultimately to force them to leave the country. This policy was justified with the argument that these areas had been artificially "Germanized" under German rule and now had to be Polonized again.

Change and development of political culture

The Kaiserreich was formative for the political culture in Germany well after the end of the monarchy. Industrialization, urbanization and the improved possibilities of communication (e.g. the distribution of daily newspapers to the lower classes) and other factors also changed the field of political culture. Whereas politics was previously primarily a matter for the elite and notables, fundamental politicization now took place, in which almost all social groups played a part in different ways. The general and equal male suffrage (from the age of 25) at the Reich level also undoubtedly contributed to this. One indication of this was the increase in voter turnout. In 1871 only 51% of those entitled to vote took part in the Reichstag elections, in 1912 it was 84.9%. The growing women's movement, which, like in other industrialized countries, formed at this time, was to prove to be a decisive component of mass politicization, demanding reforms and, in many cases, women's suffrage.

Emergence of the political camps

The formation of the various political camps took place during the founding of the Reich. Karl Rohe distinguishes between a socialist, a catholic and a national camp. Other authors subdivide the latter into a national and a liberal camp. Irrespective of party splits, mergers or similar events, these camps largely shaped political life well into the Weimar Republic . All of these basic orientations had existed in one way or another before the founding of the German Empire. However, the German Center Party (Center) was the first strong Catholic party that reached almost all social groups, from the Catholic rural population and the working class to the bourgeoisie and nobility. But the party organization remained weak and the center did not develop into a mass party. Another hallmark was the rise of social democracy. Overall, their supporters had increased eightfold between 1874 and 1912. The SPD 's share of the vote rose from about 9.1 percent (1877) to 34.8 percent (1912).

The rise of the Social Democrats was not offset by any significant decline in the bourgeois and Catholic camps. Although the Center was not able to fully maintain its level of mobilization from the Kulturkampf period, this party managed to assert itself in the face of a growing number of voters. Despite all the upheavals, the bourgeois camp still managed to reach around a third of those eligible to vote. After the disproportionate position of the National Liberals and the Free Conservative Party at the beginning of the German Empire, there were considerable shifts within this area. At the end of the Kaiserreich, left-wing liberals, conservatives and national liberals were tied at just over ten percent each.

Not least because of the Kulturkampf and later the Socialist Law , the Catholic population and the supporters of social democracy developed a particularly strong inner cohesion. Favored by other factors, a Catholic and social-democratic milieu emerged. In their environment, an organization and club system developed, which met the needs of the respective group from the "cradle to the grave". In the Catholic milieu, the development was differentiated. Above all in the agrarian parts of Catholic Germany, the pastor, the church and the traditional community-based associations tied people to the milieu. In the industrial areas and cities, on the other hand, organizations with millions of members developed with the People's Association for Catholic Germany and the Christian trade unions to integrate the Catholic working-class population .

In the social-democratic field, it was not only the SPD that developed into a mass organization after the end of the Anti-Socialist Law. Union membership increased even more. In addition, a widely ramified club system of workers' education associations , workers' singers or workers' sports clubs developed, partly on older foundations . Consumer cooperatives rounded off this picture.

The self-image and way of life of Catholics, Social Democrats and Protestant bourgeois society differed significantly. Switching between them was hardly possible. The cohesion was carried on through the respective socialization even after the end of the Kulturkampf and anti-socialist laws.

mass organizations

Not only in the political sphere, but also in almost all areas of life, the mass mobilization to assert interests and other social goals unfolded.

On the right side of the political spectrum, hypernationalism and the colonial movement mobilized adherents from different social groups. The German Fleet Association relied on 1.2 million members. At least temporarily, anti-Semitism also managed to gain considerable resonance. This included the Christian Social Party around the preacher Adolf Stoecker . Some economic interest groups took up these populist demands in order to strengthen their own position. Anti-Semitism was particularly pronounced in the German National Association of Clerks . Nationalism and anti-Semitism were closely linked in the Pan-German Association .

The Federation of Farmers (BdL) was particularly successful in organizing farmers from all over the Reich, with national and anti-Semitic undertones, although the leadership was always in the hands of the eastern Elbian agrarians . He relied on a well-developed organization with millions of members. A large number of members of the Reich and Landtag owe their mandates to the support of the federal government. These were therefore also committed to the BdL in terms of content. Industrial associations such as the Central Association of German Industrialists (CdI) were less successful in this regard. But he also managed to influence politics through successful lobbying in the background, for example on the question of protective tariffs.

Associated with the large industrial associations, the CdI and the Federation of Industrialists , were the employers' associations , which had been developing since the 1890s and were primarily directed against the trade unions' claims to a say. In addition to the large interest groups, there were numerous other economically oriented organizations. In 1907 there were 500 associations with around 2000 affiliated organizations in the areas of industry, crafts, trade and commerce alone.

One aspect of the linking of politics and advocacy among the working class was the emergence of directional unions . The supporters were (social) liberalism, the Catholic milieu and social democracy. The so-called free trade unions associated with the SPD had the highest number of members after the end of the Anti-Socialist Law. In important industrial areas, such as the Ruhr area , the Christian trade unions were sometimes just as strong or even stronger. In addition, organizations of Polish-speaking miners appeared in this area after the turn of the century, so that the non-socialist trade unions were very important in this industrial core area of the empire. The left wing of liberalism found this new form of politics particularly difficult. Liberal trade unions had existed since the 1860s in the form of the Hirsch-Duncker trade unions, but their success in mobilizing them remained comparatively small.

changing nationalism

Admittedly, there were still individual state and dynastic special identities. But overall, identification with the nation as a whole gained a formative social significance. During the German Empire, the idea of the nation state changed significantly. Until 1848/1849, the old nationalism was an opposition movement aimed at change, fed by the classical liberal ideals of the French Revolution and directed against the forces of the Restoration era, which were considered conservative at the time . At the latest with the founding of the empire, the focus began to shift. The previous opponents on the right adopted national ideas and goals. Nationalism tended to be conservative. In the long run, the democratic element lost importance.

“Unity” became more important than “freedom”. Among other things, this led to a turn against the national and cultural minorities in the Reich, especially against the Poles and – in connection with the racist-based anti-Semitism gaining in importance from the late 1870s – against the Jews (→ Berlin Anti-Semitism Controversy ). The national passions in the struggle against ultramontane Catholicism also belong in this context . In the further course of the history of the Reich, nationalism was directed not least against social democracy . Their internationalist and revolutionary ideology seemed to the political elite and their supporters to be proof of their enmity towards the Reich. Against this background, the socialists/social democrats were defamed from the end of the 19th century during the Bismarck era as “ journeys without a fatherland ” or their corresponding reputation was launched in the newspapers that were pro-government and loyal to the emperor at the time.

Since the founding of the empire, nationalism in the empire had a hitherto unknown broad effect and, in conjunction with militarism , which was also increasing, now also included the petty-bourgeois and peasant sections of the population. The nationalism was carried by the gymnastics, shooting, singing and above all the warrior clubs. Schools, universities, the (Protestant) church and the military have also contributed to the spread. "Kaiser und Reich" became established as a fixed term. In contrast, the constitution of the empire was not able to develop any independent symbolic value. Of the institutions, only the Chancellor and the Reichstag gained any importance in this regard.

The Reichstag and the general elections became a visible piece of national unity. With the celebrations of the emperor's birthdays, the Sedan Day and other occasions, the national pervaded the annual calendar, especially of the rural and middle-class population. Nationalism was also visible in the numerous national memorials such as the Niederwald memorial , the Hermann memorial , later the Kaiser Wilhelm memorial on the Deutsches Eck or the Porta Westfalica , the numerous Bismarck towers and the local war memorials.

In the long term, even the "enemies of the Reich" could not escape the pull of the national. Since 1887, at the Catholic Days , cheers have not only been given to the pope, but also to the emperor. Especially after the beginning of the war in 1914, it became apparent that the workers were by no means unaffected by nationalism.

Especially during the Wilhelmine era, alongside the semi-official nationalism, there was a growing trend towards radical nationalism , such as that represented by the Pan-German Association . He propagated not only the creation of a large colonial empire, but also a Central European sphere of power ruled by Germany.

Bismarck era

The first decades of the new empire were largely shaped by Bismarck as a person, both in terms of domestic and foreign policy. The period between 1871 and 1889 is clearly divided into two phases: from 1871 to 1878/79 Bismarck worked primarily with the Liberals. In the period that followed, the conservatives and the center dominated.

Liberal era until 1878

In view of the constitutional conflict in Prussia in the 1960s, it is surprising at first glance that Otto von Bismarck worked closely with the Liberals politically even during the existence of the North German Confederation and in the early years of the German Empire. A central reason for this was the majority situation in the Reichstag, in which the Liberals had a strong majority. The National Liberals alone had 125 out of 382 seats in 1871 . If one includes the members of the Liberal Reich Party and the Progressive Party , Liberalism had an absolute majority; this was mostly reinforced by the Free Conservatives . After the Reichstag election of 1874 , the Liberals alone had an absolute majority with 204 out of 397 deputies. The Chancellor could hardly govern against them – and he probably could not have governed with the Conservatives with other majorities either: They rejected Bismarck’s policies and the Center ceased to be a possible counterweight at the latest when the Kulturkampf began.

The politics of the founding phase of the empire were made easier by the booming development of many economic sectors, which contributed to the social acceptance of liberal reforms.

Domestic and legal policy reforms

Bismarck's real partners were the National Liberals under Rudolf von Bennigsen . Although they were willing to compromise on many points, they also succeeded in pushing through central liberal reform projects. Cooperation was facilitated by liberal officials such as the head of the Reich Chancellery, Rudolph von Delbrück , or the Prussian Minister of Finance , Otto von Camphausen , and the Minister of Education, Adalbert Falk . The main focus of the reforms was the liberalization of the economy. Freedom of trade and freedom of movement were introduced in all federal states where they did not already exist. In the spirit of free trade , the last protective tariffs for hardware expired. A trademark and copyright protection as well as a uniform patent law were introduced. The founding of stock corporations was also made easier. In addition, measurements and weights were standardized and the currency unified: in 1873 the mark (later called 'Goldmark') was introduced. The Reichsbank was founded in 1875 as the central bank of issue. Another focus was the expansion of the rule of law , the foundations of which have survived in part to the present day. The main features of the Reich Criminal Code of 1871 , which is still in force today, but has been amended many times, should be mentioned. This is very similar to the Criminal Code of the North German Confederation of May 31, 1870.

Milestones were the Imperial Justice Laws of 1877, namely the Courts Constitution Law, the Code of Criminal Procedure , the Code of Civil Procedure , the content of which has also been modified, is still in force today, as well as the Bankruptcy Code . The Imperial Court of Justice was introduced in 1878 as the highest German criminal and civil court. A unified supreme German court of justice, which also replaced the existing Reich Higher Commercial Court , made a major contribution to the legal unification of the Reich. In addition, the liberal majority also succeeded in extending the powers of the Reichstag in questions of civil law. While the parliament in the North German Confederation was only responsible for civil law issues with an economic background, at the request of the National Liberal Reichstag deputies Johannes von Miquel and Eduard Lasker , responsibility was extended to all civil and procedural law in 1873. As a result, the Civil Code , which was passed in 1896 and came into force on January 1, 1900, was created as the codification of private law that is still in force today .

However, the liberals had to accept far-reaching compromises in the area of procedural regulations and press legislation, which some left-wing liberals did not support. A majority came about in 1876 only with the help of the Conservatives. Since there was also a liberal to moderately conservative majority in the Prussian House of Representatives , political reforms were also carried out in the largest federal state. This includes, for example, the Prussian district order of 1872, which also eliminated the remnants of estate rights. The threat of failure due to the resistance of the Prussian dynasty could of course only be broken by a " Pairsschub " (i.e. the appointment of new politically acceptable members).

culture clash

The cooperation between the liberals and Bismarck worked not only in the reform policy, but also in the so-called Kulturkampf against the Catholics and the Center Party. Structurally, the causes lay in the contrast between the secular state, which claimed more and more regulatory powers, and an official church, which opposed modernity in all its manifestations in the spirit of ultramontanism (" anti-modernism "). The 1864 encyclical Quanta Cura with its syllabus errorum was a clear rejection of modernity. For the Catholic Church, liberalism, as the legacy of the Enlightenment and as the bearer of modernization, represented the opposite of their own positions. For their part, for liberals, the papacy, with its rejection of any change, was a relic of the Middle Ages. Bismarck had various reasons for the Kulturkampf. For example, he suspected the clergy of promoting the Polish movement in the Prussian eastern provinces. He, too, fundamentally did not want state authority and the unity of the empire to be restricted by other older powers. Domestically, he was also concerned with dissuading the liberals from further domestic reform projects by redirecting the political debate. The dispute between the modern state and the ultramontane church was a common European phenomenon. In German states such as Baden ( Badischer Kulturkampf ) and Bavaria, there had already been a Kulturkampf in the 1860s. Most of the Catholic bishops in Germany did not aggressively pursue the papal criticism of modernity, and since 1866 there has not been a Catholic faction in the Prussian House of Representatives. In fact, in 1866 the Mainz Bishop Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler spoke out in favor of recognizing the Little German solution.

In the initial phase from 1871, the liberals and the government were concerned with increasing state influence. The penal code was expanded to include the so-called " pulpit paragraph ", which was intended to restrict the political activities of clergy. The Jesuit order , known as the ultramontane 'spearhead' , was banned. In addition, state school supervision was introduced in Prussia.

In a second phase, starting around 1873, the state now intervened directly in the inner sphere of the church, for example by subjecting the training of priests or the filling of church offices to state control. In a third step, further laws such as the introduction of civil marriage followed from 1874 onwards . An expatriation law of May 1874, which allowed the stay of insubordinate clergymen to be restricted or, if necessary, expelled, was purely an instrument of repression. The so-called breadbasket law blocked all government grants for the church. In May, all monastic communities were dissolved unless they devoted themselves exclusively to nursing.

One consequence of the Kulturkampf laws was that in the mid-1870s many pastoral posts were vacant, church activities no longer took place, and bishops were arrested, deposed or expelled. But the government's actions and the demands of the liberals quickly led to backlash and widespread political mobilization within Catholic Germany. The Center Party, founded before the actual start of the Kulturkampf, quickly attracted the majority of Catholic voters.

limits of cooperation

Bismarck and the Liberals did not agree on all points. For example, the attempt by the National Liberals and the Progressive Party to unify the various city ordinances failed, also due to the lack of support from the Reich Chancellor. A financial reform initially failed due to Bismarck's objections. The military budget remained a permanent problem. At first the conflict could be put off, but by 1874 at the latest it was back on the agenda. While the government, and in particular Minister of War Albrecht von Roon , demanded permanent approval of the budget ( Aeternat ), the Liberals insisted on an annual right of approval. Giving in would have meant giving up about eighty percent of the total budget. The dispute ended with a compromise - the grant for seven years ( Septennat ). At least the regulation of military strength by law remained, albeit stretched out over a fairly long period of time. Furthermore, the Liberals were unable to assert themselves on civil service law, military criminal law and the demand for jury trials for press offences.

In the first half of the 1870s the Liberals had managed to make their mark on a number of policy areas, but this was only possible through compromises with Bismarck. Not infrequently, maintaining power was more important than enforcing liberal principles. There was also internal criticism, for example of the exceptional laws of the Kulturkampf. In particular, it failed to strengthen Parliament's rights. This led to tensions within the liberal camp and disappointment among some groups of voters. In addition, a new political direction had emerged with the center. Since then, the liberals could no longer claim to represent the people as a whole. Bismarck succeeded in strengthening state power in the early 1870s. However, the alliance with the Liberals meant that the government had to make concessions and promoted economic and social modernization.

Founding years and the founding crisis of 1873

Shortly after the founding of the empire, there was an economic boom, the so-called founding years began. This was followed by an economic depression called the “ Gründerkrach ” . Several factors are considered to be the causes of the upswing: Trade within the borders of the empire was greatly simplified. For the first time in the history of the empire, a uniform domestic market was created. The impeding national tariffs were eliminated. A uniform metric system of measurement was introduced in late 1872. A general spirit of optimism triggered by the success of the war and the founding of an empire led to an enormous increase in investment and a construction boom. France 's very high reparation payments also played a major role in financing the Gründerzeit.

As early as 1872, the German Reich trumped France, which had been weakened by the war, as an industrial power. From around 1873 to around 1879 the so-called start-up crisis followed. It became public knowledge from the Berlin stock market panic of October 1873 (the Vienna stock market crash of May 9, 1873 is considered a harbinger). At first, industrial production was easy; then it stagnated. The economic crisis was a consequence of overheated speculation, a consequence of falling demand and overcapacities that had been built up in the boom years. The various sectors suffered from the crisis in different phases and to different extents. The coal and steel industry, mechanical engineering and construction industry were particularly affected; the consumer goods industry suffered less.

Many commodity prices, profits and wages fell significantly. Agriculture fell into crisis in the mid-1870s. Above all, structural reasons and the emergence of a world grain market played a role here. In direct competition with Russia and the USA , German grain soon became too expensive even on the domestic market.