Right to vote in the individual German states until 1918

The individual German states play a special role in the history of the right to vote in Germany , as they existed much earlier than a single German state. Developments such as the introduction of elected parliaments per se or the discussions about secret voting rights , for example , had specific reference to the individual states. At the same time, however, an all-German debate has already taken place in newspapers and literature. The March Revolution of 1848/1849 had the greatest influence on the individual states, almost everywhere the constitutions and electoral laws were changed or at least new elections were held.

The founding of the North German Confederation (1867–1870 / 1871) and the German Empire (1871–1918) are less visible in the history of the electoral law of the individual states . But the universal and equal right to vote in the Reichstag fueled the discussion in the individual states, in which such a right to vote was seldom realized.

State and State

Originally, the individual German states were sovereign and could independently grant or limit voting rights. The German Confederation (1815–1866) required a state constitution from the individual states, but what this meant was not precisely defined. The two largest states, Austria and Prussia , did not adopt a constitution with national representation for the first time until 1848/49. However, laws of the German Confederation had an effect on the political situation of the individual states, for example the restriction of freedom of expression and freedom of association through the Karlsbad Decisions of 1819. This legislation was particularly active in the 1830s and 1850s.

March Revolution 1848/1849

In the spring of 1848 liberals had joined the governments in many German individual states ( March governments ). Since they had often had experiences in the regional parliaments of Vormärz, the state parliaments already appeared to them as legitimate organs of popular representation. Even the left hardly thought at that time of calling for new electoral laws, for example, in states that had representative constitutions before 1848. It was only with the resolutions that led to the same and relatively general election to the National Assembly that there was greater awareness that at least new elections were appropriate everywhere. Only occasionally did discussions lead to the demand that the March governments impose a new right to vote.

In the Frankfurt National Assembly there were two views from the beginning. According to the more moderate, the constitutions of the individual states should be revised according to the specifications of the imperial constitution (still to be drawn up). More radical was the view that provisions in the constitutions of individual states were automatically invalid if they contradicted the future imperial constitution. The vast majority of the National Assembly broadly followed the second view. This is important for the way the National Assembly sees itself, for all reform legislation and thus also for the right to vote. The March Revolution brought about changes in the electoral law in almost all German individual states. However, progress was often undone when the reaction began; the imperial constitution and the right to vote of 1849 remained proposals that were not implemented.

North German Confederation and Empire 1867–1918

In 1871 a German nation-state was formed; the electoral laws generally remained the same. The experience of the general and equal Reichstag electoral law had an influence on the electoral law debate in the individual states. There were attempts to use the Reich for reforms at the state level. Mecklenburg was the only federal state to have only one state constitution and was the object of an initiative by Friedrich Büsing, a member of the Reichstag . On November 2, 1871, the National Liberal from Mecklenburg-Schwerin demanded an expansion of the imperial constitution: All federal states should have an organ that emerged “from elections by the population” and whose approval was necessary for state laws and the budget. The Reichstag accepted the proposal, but the Federal Council rejected it in 1875. After all, the Federal Council expressed its expectation that the constitution in Mecklenburg would be reformed and thus implicitly accepted the relevant competence of the Reich.

In 1908 a long-term attempt to give the Mecklenburg duchies at least a partially elected representative body failed due to resistance from the knighthood . The liberal parliamentary groups in the Reichstag urged the Federal Council to take action. But the answer they received was that intervention by the Reich would be contrary to federal principles. It could not be acceptable for the federal states to receive their constitution from the hands of the Reichstag and Bundesrat.

In particular, the Social Democrats tried to pull the struggle for universal and equal suffrage in the individual states such as Prussia on the Reich level. To this end, on December 2, 1905, they introduced a motion to the Reichstag to change the Reich constitution. It should prescribe universal, equal and secret voting rights for the states. Conservatives, Center and Christian Socials rejected the request as interference by the Reich in state affairs. Like the left-wing liberals, the National Liberals were of the opinion that the Reich had the right to do so, but nevertheless rejected the proposal, which ultimately failed.

In October 1918, towards the end of the First World War, a bill was finally passed in Prussia that would have introduced universal and equal male suffrage. As a result, women's rights activists protested together - from the bourgeois feminist Gertrud Bäumer to the socialist Marie Juchacz , trade unionists as well as liberals - because the draft showed that the reformers were not thinking of them. The Social Democrats in the Reichstag wanted to speed up the process, and on November 8, the parliamentary groups in the Intergroup brought a bill. The Reich Constitution, in an amended Article 20, was supposed to demand general, equal, direct and secret proportional representation for men and women over the age of 24 for the Reichstag and all state parliaments.

Individual states in the Napoleonic period until 1815

Model states

Napoleon , self-proclaimed Emperor of France since 1804 , created the Kingdom of Westphalia , the Grand Duchy of Berg in West Germany in 1807 and the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt in 1810 . As model states, the first two were supposed to bring the Germans closer to a liberal government and thereby alienate them from the alleged arbitrary regime of Prussia; Frankfurt was very similar to the two role models Westphalen and Berg. The introduction of the French Civil Code was a real step forward, otherwise the constitutions only poorly concealed the sole rule of the King or Grand Duke. In this way the sympathy of the population could not be won. The assemblies of the estates were only called once or twice and for that reason alone did not serve as a role model. In the imperial pseudo constitutionalism in Napoleon's France itself, the corps législatif had at least one subordinate function.

The old social conditions, shaped by the feudal structure and the church, remained. Despite civil equality and freedom in the legal system, a “system of aristocratic-bureaucratic oligarchy” (Huber) prevailed in this Napoleonic pseudo constitutionalism.

According to the French model, Westphalen consisted of departments whose colleges elected the members of the imperial estates . In the end, this assembly of estates was only allowed to act in an advisory capacity on legislation, which otherwise was the sole responsibility of the king. The king was in turn a brother of Napoleon. As early as 1810, the king only ruled by ordinances, but for the time before that, it can be said that the Westphalian imperial estates were the first representative assembly in Germany without an estate basis.

The department colleges in Westphalia were appointed by the king. Four-sixths of the members should belong to the highest taxable persons in the department, a further sixth of wealthy merchants and manufacturers, and a last sixth of particularly distinguished artists and scholars and well-deserved citizens. The constitution also determined the social origin of those who were allowed to be elected by the departmental colleges. Of the hundred deputies, i.e. the members of the assembly of estates, seventy had to be landowners; fifteen merchants or manufacturers; the rest of the class of those who had rendered services to the state. Furthermore, the regional origin of the deputies should also be taken into account in the election.

In the state elections of 1808 in Westphalen it was shown that half of the elected belonged to the landed nobility. Otherwise, they were representatives of the rich upper class; the scholars, apart from professors, were often state officials. The assembly of the estates hardly represented the population, but was an assembly of notables . There was no real right to vote in Westphalia.

The Westphalian electors voted secretly by ballot and, as a rule, each other. After one session in 1808 there was only one more session, from January to March 1810. According to the keynote speech by MP Wachler, there should be no deliberations on the laws, and the current state budget was only now presented to the estates. When parts of Hanover were added to the Kingdom of Westphalia at that time, the new departments were redistributed among the hundred members. The historian Helmut Stubbe da Luz called the stands “a political sandpit”.

The Napoleonic constitution of Frankfurt was similar to the Westphalian one. In addition to the old imperial city, the newly established Grand Duchy of Frankfurt also comprised a few more eastern areas with Aschaffenburg and Fulda . Aschaffenburg was the royal seat. The meeting of the estates there consisted of twelve large landowners, four wealthy merchants or manufacturers and four scholars. A third of them were elected every three years. As in Westphalia, the voters were the departmental colleges, which in turn were appointed by the Grand Duke. There were also rules in Frankfurt about the social composition of the departmental colleges.

In the Grand Duchy of Berg , there was no written constitution. A college of March 15, 1812 was to have 85 members to be elected by the cantonal assemblies of the notables, ten of which were to be determined by the Grand Duke. From 7,500 people with the highest taxation, 2,860 notables were determined from above. They should then choose from a list of 600 highly taxed candidates. As in the French Empire, the cantonal assemblies did not deliberate but only voted. A list of 550 candidates was presented to Emperor Napoleon in Paris, which he could have filled out. It was not until early 1813, after the Russian campaign, that he got around to approving the list. The Consultative Assembly of Berg never met, and in October 1813 the Grand Duchy had already ended.

Southern German reform states

During the Napoleonic era, Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden succeeded in enlarging their respective national territories considerably and in gaining a higher rank for their princes, so the former kingdoms and Baden became a Grand Duchy. Some of the rulers pushed through anti-class reforms that really helped absolutism to break through in those countries. All of this continued after 1815. The members of the assemblies of the estates were rarely elected, but usually appointed by the cities, universities or church chapters. The knights came to the diets in person.

In late absolutist Württemberg there were no questions about suffrage, but there were in Bavaria and Baden. The Kingdom of Bavaria had had a constitution since 1808, according to which a general assembly of electors should meet in the individual districts. The king selected the electors from among the four hundred landowners, merchants or manufacturers who paid the most property tax in the district. The election of the electors was for life, so that one can doubt whether it was at all an election act. The electors then elected seven MPs for the National Representation, from the group of the 200 most taxed persons. The aim of these regulations was to replace the nobility with a new elite.

In the Grand Duchy of Baden there was no meeting of the estates. According to a draft from 1808, the district administrator should have 24 members. They were to be determined according to occupational groups. Three had to come from the class of "land table-like" landowners, with all of them being entitled to vote. Nine were supposed to come from agriculture, but only the town councilors were allowed to vote. Nine would have come from trade and commerce, chosen by the cities, and three from the sciences, chosen by the "scholars". The elections should only take place in one district at a time.

For those to be elected in Baden:

- They had to be of the class she chose;

- had to live in the respective province for at least six years;

- had to be at least 40 years old;

- were not allowed to be in foreign service;

- were not allowed to work in a central authority in Baden;

- had to be innocent .

The representatives of the landscape had to have their own soil, the trade representatives their own trade. The draft for Baden was therefore more classically shaped than the Bavarian constitution.

Prussia

In Prussia , the defeat against Napoleon in 1806/1807 initiated domestic political reforms. However, a modern constitution and a representative assembly did not take place, despite the king's promises. An assembly of notables appointed by the king in February 1811 was dissolved in September after the 64 members fell out.

An interim national representation from 1812–1815 with 42 members was actually put together by various groups and bodies:

- 18 from the noble landowners to the old-class district assemblies

- 12, later 14 by city councils

- 9 from the non-noble landowners who owned at least one hoof of land

The gathering had no significant influence, but on April 10th itself called for the adoption of a constitution and eventual representation. In his constitutional promise of May 1815, the king announced an advisory state parliament for all legislation, which was to be elected by the provincial estates. In such an indirectly elected national representation, the property owners and educated citizens would have been entitled to vote in the participating estates. However, after the interim national representation was dissolved in July 1815, the development of the constitution stopped.

Due to the city order of 1808, however, there were elections at the local level. Male citizens who were resident in the respective city as homeowners or who had a certain tax revenue (depending on the size of the city 150–200 thalers annual income) were allowed to vote. They directly elected the city council for each district. This in turn elected the magistrate, the city government. In Berlin, seven percent of the city's population was allowed to vote, that was a third of the male adults. The delegates were representatives of the entire community, no longer just one class.

According to an organizational plan drawn up by Freiherr vom Stein on November 23, 1807, the provincial estates were to be elected. All landowners would have had the right to vote and thus the noble landowners as well as citizens and farmers. According to Stein, only independent owners had the maturity to participate in public affairs. In the law on provincial estates of 1825, one third of the seats in the provincial estates were assigned to bourgeois landed property, and a total of two thirds to aristocratic and peasant estates. The provincial estates only had an advisory function for matters relating to the entire Prussian state; they were only allowed to resolve provincial matters.

Southern German individual states 1815–1918

In southern Germany, the bicameral system prevailed in 1818/1820 and thus provided an example for many other German states until 1918. Parliament consisted of a first chamber, which had mostly appointed members, and a second chamber, the majority of which were elected. This system preserved the old social differences. For example, nobles who were mediatized during the time of the Rhine Confederation could be integrated into the respective new state by receiving a seat in the First Chamber. The bicameral system should also deliberately separate the nobility and the bourgeoisie. Despite their different composition, both chambers were supposed to represent the entire people, with the first saving a remnant of the noble privileges in the constitutional system.

In all four states, a law could only be proposed by the prince or his government and only passed if both chambers agreed. The chambers were convened by the respective prince; the mandate of the elected MPs was free and lasted six (in Baden: eight) years. The dissolution was also carried out by the prince, not by the MPs themselves. Men who were at least 25 years old were allowed to vote; Wealthy men aged 30 and over could be elected.

Bavaria

In Bavaria the first chamber was called the " Chamber of Reich Councilors ". Its members were the royal princes, the crown officials (crown chief steward, crown chief chamberlain, crown chief marshal, crown chief postmaster), the two archbishops , another (Catholic) bishop, the president of the Protestant general consistory, heads of mediatized families, and finally those appointed by the king (for life or hereditary) ) People.

The members of the Second Chamber were elected in classes from the individual estates. One eighth of the deputies: aristocratic landowners with landlord jurisdiction , another eighth of the deputies: Catholic and Protestant clergy, a quarter of the deputies: representatives of the cities and markets, half of the deputies: the other landowners, regardless of whether they were noble or noble not, and finally a representative from each of the three universities. The electoral process in the individual classes was different, so the choice in the first class and the universities was direct, in the other classes several times indirect. The requirements for voting and being elected were also different in each class: for landowners with jurisdiction and clergy, membership of the relevant class was sufficient, and for the university class, a full professorship was sufficient. A census was only required in the classes of the cities and the other landowners. This severely restricted the number of passive voters, especially in the last class. At the election in 1818 there were 673,164 families in this class only 6689 passively eligible voters, in some district courts there was not a single one.

In the March Revolution a new electoral law was passed on June 4, 1848. Whoever paid taxes was allowed to vote; the election should be equal and indirect.

After the revolution, the highly conservative Minister of the Interior, Count Reigersberg, tried unsuccessfully in 1854 to restore the old electoral system of 1818, and the government did not dare to impose it on the Prussian model. In 1858/1859 the government reconsidered the conflict with the chambers, but feared a loss of reputation in Germany and resigned.

With changes to the electoral law of 1848, secret voting was introduced in 1881.

In Bavaria, non-taxpayers were excluded from voting, which, in addition to the constituency division, benefited the Liberals. In addition to the Social Democrats, the center and the farmers' union also pushed for reform. They wanted proportional representation with universal and direct suffrage. After an attempt in 1903, a reform followed after the elections in 1905. According to the election law of April 9, 1906, the election was still a census election. Instead of 6 months, you had to pay a direct tax for a year in order to be able to vote. From then on, however, the choice was the same, secret and direct. Bavaria was one of the few German federal states to introduce relative majority voting. However, a candidate could only win if he had received at least a third of the votes cast. Of the 163 MPs, 103 were elected in single-constituencies and 60 in 30 two-electoral constituencies. In contrast to the constituency division for Reichstag elections, the number of residents per member of parliament was almost the same in the individual constituencies.

Württemberg

In Württemberg , the first chamber also consisted primarily of the king's sons, certain heads of families and members appointed by the king; the representatives of the church, however, sat in the second chamber. In the second chamber sat 13 members of the knightly nobility, the six Protestant general superintendents, three high Catholic clergy, the chancellor of the university, one deputy from each of the seven most important cities and one deputy from each of the 64 higher offices (a local administrative unit). The men of voting age who pay direct taxes were allowed to vote, although at that time there was only property tax in Württemberg as such. About 17.4 percent of the population were primary voters in 1844.

A newly elected assembly of estates passed a new electoral law on July 1, 1849. Accordingly, the two chambers should be replaced by a single one, which revised the constitution. But the conservative turnaround was already beginning: the king dismissed the liberal government in October and soon dissolved the state assembly on December 1, 1849. The new one from March 1850, however, also had a radical democratic majority and assumed that the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution had put an end to the German Confederation; the majority therefore rejected the foreign policy of Württemberg, which together with Austria thwarted the Prussian union policy. The conflict persisted even after the election of a third regional assembly, so that the king ordered a new election according to the old electoral system. With this coup he was successful, because the Democrats took part in the new elections in 1851. A liberal-conservative majority then ultimately supported the king's policy of reaction .

In the 1880s there was a majority in the Second Chamber for constitutional reform. The “privileged”, the representatives of the knighthood, churches and the university, should leave the chamber when general and equal elections were introduced. However, the government demanded a conservative element such as partial census voting for the case. An election defeat of the governing parties in 1895 led to a reform proposal by the government, which was rejected by the center in 1898 because of differences of opinion on another topic. Another attempt led to the goal on July 16, 1906, after two of the privileged had also approved a government draft and thus enabled a two-thirds majority. The privileged passed from the second to the first chamber. The members of the Second Chamber were elected according to universal and equal suffrage. The 63 MPs from the districts and some larger cities were elected by majority vote, the six MPs for Stuttgart and 17 MPs in two state constituencies by proportional representation.

to bathe

In Baden, the First Chamber brought together the princes, the heads of the noble families, the Archbishop of Freiburg , a Protestant prelate (appointed for life by the Grand Duke), eight representatives of the noble nobility, two members of the Universities of Freiburg and Heidelberg, and others appointed by the Grand Duke People. In Baden, therefore, not only the high, but also the lower nobility were represented in the First Chamber. There were only elected representatives of the cities and rural communities, in contrast to the other southern German Second Chambers. This shows the particularly progressive, liberal character of Baden. Whoever was a resident citizen (i.e. who owned property) or held a public office was allowed to vote, which means that the influential class of public officials was also allowed to vote. In the chamber election in 1845, 16.8 percent of the population were primary voters.

After the March Revolution, the last Landtag de facto ended its activities on May 14, 1849, and Grand Duke Leopold declared it closed. The resigned radical democrats were replaced by replacement elections, and after March 6, 1850, the state parliament had a liberal-conservative majority.

Since 1869, the right to vote in Baden was universal and equal, while previously only those who had citizenship or held public office in the electoral district were eligible to vote. The electoral law debate was about the introduction of direct voting, which took place in 1904. Since the electoral law of August 24, 1914, the Second Chamber had to elect 73 members, general, direct, equal and secret. A voter had to be over 25 and have had Baden citizenship for at least two years, and also had to live in Baden. Anyone who lived in the same place of residence in Baden for at least one year before the election was allowed to choose citizenship after just one year. The winner in the constituency was whoever achieved an absolute majority in the first ballot, otherwise the relative majority was sufficient in the second. Only those who received first place, second place or at least one tenth of the votes in the first ballot were allowed to participate in the second ballot. There was also a first chamber with members by birth or office as well as those elected because of property ownership.

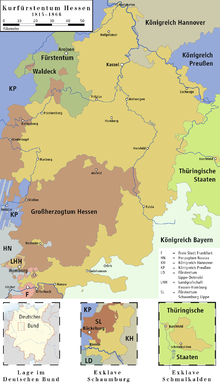

Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hessen-Darmstadt)

The Grand Duchy of Hesse had, according to its Constitution of 1820, a first chamber with representatives of the nobility, churches and universities. The lower nobility was in the second chamber. Of the members of the Second Chamber, 34 were elected from the country and ten from the larger cities, six from the landed nobility. There was a census right to vote in which the right to vote depended on the tax burden.

The Hessian chambers had passed an electoral law that strictly paid attention to equality, but the liberal ministry did not have it promulgated until September 1849. The newly elected chambers in December were dissolved by the Grand Duke in January 1850, as the Liberals dominated the First Chamber, while the Radical Democrats dominated the Second.

In the conflict over Union policy, the Grand Duke dismissed the liberal ministry, and when the newly elected Chamber in June 1850 refused to determine the tax, the Grand Duke dissolved the Chamber again. He banned political associations by issuing emergency ordinances, abolished freedom of the press and imposed indirect census voting rights. The new chambers (since 1851) followed the government.

In 1856, 1872, 1875 and 1885 there were minor changes in the electoral law, but only those who paid a direct state tax were allowed to vote permanently. The system gave the National Liberals large majorities. After losses by the National Liberals and an attempt at reform in 1903, three laws were passed on June 3, 1911 that made the election to the Second Chamber secret and direct. The census remained, and in addition, voters over fifty years received a second vote. The winner was the candidate with an absolute majority in the constituency, possibly after a runoff election. In order to be eligible to vote, you had to have paid a direct municipal or state tax in the previous financial year, with exceptions, for example, for military officials and invalids.

North and Central German states 1815–1918

In northern and central Germany it often took until after the French July Revolution of 1830 for a federal state to receive a representative constitution. It provided a foretaste of the March Revolution of 1848/49, as a result of which almost all other states took this step. Only the two Mecklenburg duchies still had an old-class constitution in 1918.

Hanover until 1866

In the Kingdom of Hanover , the constitutions of 1833 and 1840 were representative constitutions. The constitution of 1833 spoke of two chambers. The first continued to represent the nobility, the second had ten prelates, 37 municipal and 38 rural deputies as members. The self-employed citizens had the right to vote in the city and the self-employed farmers in the countryside. The state parliament decided on laws, taxes and the budget, in the case of restrictive prerogatives of the king.

But the time of the constitutional system was short-lived. In 1837 the new king, Ernst August , declared that he was not bound by the constitution because he had not been asked for consent at the time. But this constitution restricts the rights of the king; Ernst August ultimately argued that this would diminish his royal legacy. After violent protests inside and outside of Hanover, the King and Parliament agreed a new constitution in 1840, which, although it emphasized the monarchical principle more strongly, but ultimately did not undermine the constitutional state in such a way that the three years of serious dispute would have been worthwhile.

According to the constitution of 1840, the First Chamber had sixty members (in 1848), most of whom were elected chivalrous deputies. The second chamber comprised class members who were appointed by the king, the churches or the university or elected by the provincial authorities. 37 MPs were elected from the towns and cities and 39 from the rural landowners who represented the historic landscapes. The latter in particular represented very different population sizes, one of them 8,697, the other 57,452 inhabitants. Eligible to vote for the Second Chamber was usually anyone who was also allowed to vote for the community there according to the regulations in their home town. These were usually just home and landowners. The elections were indirect. For the right to be elected, a certain tax payment was required, a minimum age of 25 years and the Christian denomination.

Manfred Botzenhart:

"If you consider that in addition to the general assembly of estates formed in this way, the provincial landscapes of the individual areas of the kingdom also continued to exist, then it can be said that no other German state in the institutions of popular representation has so much historically grown, locally peculiar and the spirit of the Time kept contradicting things in the framework of a constitution passed after the July Revolution, while especially in the southern German states after the turmoil of the Napoleonic period, the need to bring old and new possessions through a state unity had come to the fore to merge justifying, but leveling and anti-historical constitution into a new whole. "

In the March Revolution of 1848, at the end of March, the so-called “conditional deputies” demanded a reform of the assembly of estates. Similar to the pre-parliament at the federal level, these were representatives from community assemblies or popular assemblies without actual legal legitimation. They reappeared in April after a committee from both chambers of estates and the government proposals, among other things, failed to propose a revision of the First Chamber. They wanted to see the pre-parliamentary suffrage enforced, with the criterion of independence based on the payment of a direct tax. When they demanded that there should be one member for every 15,000 inhabitants, the previously privileged smaller towns protested, so that they were finally asked to let them have their previous number of members. The first chamber should be abolished. The government and the assembly of estates received the demands quite coolly.

The Constitutional Commission of the Assembly of States disputed the composition of the First Chamber; especially about the hereditary virile votes and the number of those elected. The latter should be increased and the right to vote extended to a total of 5,000 voters. A fundamental reform of the Second Chamber was opposed to the self-interests of the previous MPs, who did not want constituencies with the same number of inhabitants. However, in future the right to vote should apply to all men over 25 years of age who were ungodly, who paid direct state tax, and who were not under trusteeship or paternal authority. The census was minimal, but about ten percent of the adult men who were allowed to vote in the Frankfurt National Assembly in Hanover were excluded. The First Chamber rejected the suggestions of a detail, but gave up, among other things after the Second Chamber threatened to convene a constituent assembly for Hanover in June.

On September 5, 1848, the constitution of 1840 was revised according to these provisions so that its content was similar to that of 1833. An election law of October 26 regulates further details. According to individual figures, between 56 and 80 percent of adult men had the right to vote.

After the revolution, the German question remained a matter of conflict between the moderate-liberal government and the Second Chamber. King Ernst August, who opposed the unification efforts, dissolved the chamber in early 1849. The re-assembly of the newly elected did not happen until November 8th. A joint committee of both chambers proposed in 1853 that the knights should be given greater consideration in the First Chamber, but the majority of the Second Chamber rejected this. The king therefore dissolved it on November 21, 1853. A Bundestag resolution confirmed the view of the Hanover government that the constitutional law of 1848 had unjustifiably robbed the knights of their representation. In 1855, the government declared the amendment to the constitution to be repealed.

Oldenburg

The Grand Duke of Oldenburg issued a patent on March 10, 1848, with which he had 34 members of a constitutional committee elected. In the future, the election should be general and the representative parliament must approve laws. The committee followed the liberal model of Electoral Hesse, and the Grand Duke ordered the election of the constituent state parliament. Primary voters had to be male citizens of legal age who had their own household (i.e. exclusion of servants). These primary voters chose electors with a very low turnout. The government and the state parliament agreed on the constitution of February 18, 1849. The only chamber was elected according to general (excluding servants) and indirect voting rights.

As of 1909, the state parliament of Oldenburg had 45 members. The elections were general and secret, but not the same, as you could cast an additional vote if you were over forty. Voters and eligible voters had to live in the Grand Duchy for at least three years.

Braunschweig

According to the Renewed Landscape Regulations of April 25, 1820, the free farmers received twenty members of the state parliament of the Duchy of Braunschweig . After an unsuccessful ducal coup d'état, a new landscape order was adopted in 1832, which Duke Wilhelm and the estates jointly agreed. It was now a really representative constitution. The only chamber was still called the landscape, and could choose who had to pay taxes.

The electoral law of September 11, 1848 introduced universal suffrage for men. The election was unequal because almost half of the MPs were withheld from the highest taxed. On May 6, 1899, the Braunschweig electoral law stipulated that 18 members were to be elected from the professions and thirty by general election. For the latter, the indirect three-tier voting right applied. On May 20, 1908, a new law introduced direct voting and softened class elections. Third-class voters (seventy percent of all eligible voters) had one vote, second-class voters two (twenty percent), and first-class voters (ten percent) three. Four electors were chosen for each class in a district. The electors then elected a total of thirty members. In addition, there were 18 members elected by the professions (such as clergy, large landowners, highest taxed persons, etc.).

lip

Lippe-Detmold elected its 21 members of the state parliament secretly and directly according to a three-class suffrage. In contrast to Prussia, each class did not vote a third of the electorate, but a third of the MPs.

Schaumburg-Lippe

Despite the promise of a constitution in 1848, Schaumburg-Lippe did not receive a constitution from its prince until 1868 with strong estates. The Landtag had 15 members, some of whom were elected by knightly landowners, preachers and certain professional representatives (two by the sovereign). The cities elected three and the districts seven representatives. Landowners didn't have to be nationals.

Kurhessen (Hessen-Kassel) until 1866

The Electorate of Hesse (Hessen-Kassel) remained without a constitution after the liberation of Napoleon, despite promises made by the prince. In 1830 an uprising led to the meeting of a state parliament, which on January 5, 1831 led to an agreed constitution . It did not end the constitutional conflict because it was particularly radical for the time.

The assembly of estates was the only chamber, on the one hand it united the princes, the heads of the mediated families, members of the former imperial nobility and the knighthood. On the other hand there were 16 delegates each from the cities and the rural districts, half of which had to be able to show possession. According to the electoral law of February 16, 1831, the election was indirect. Laws needed the approval of the meeting of the estates and the prince, both had the legislative initiative. The constitution ensured the fundamental rights of subjects, and the assembly of estates could indict ministers of constitutional violation in the Supreme Court.

The liberal constitution did not escape reactionary politics after 1849. The revised (and imposed) constitution of 1852 introduced a two-chamber system with strict census voting rights. The chambers no longer had the right to initiate legislation, and in constitutional conflicts it was no longer the local court that decided, but the Bundestag. As expected, the newly elected state parliament of July 16, 1852 resulted in a conservative majority decimating the liberals and removing the left. Nevertheless, the conflict in Hesse persisted.

Nassau until 1866

The Duchy of Nassau had an assembly of estates since 1818. In the course of the March Revolution it was given a unicameral system with indirect and universal elections, and a constitution of December 28, 1849 agreed with that Landtag. In 1851 the government repealed the constitution and passed a new electoral law. The voters of the Second Chamber were divided into three classes and voted orally. In the First Chamber, in addition to the princes, owners of the class and manors, the Catholic and Evangelical bishops, there were other members who were elected by the highest taxed landowners and traders. The Liberals called for the constitution of 1849 to be restored and, despite the dissolution of the state parliament in 1864 and 1865, won a majority. The new parliament had two chambers. In 1866 Nassau was annexed by Prussia.

Waldeck

The Principality of Waldeck received in 1816 a new constitution instead of the old provincial estates. On June 14, 1848, a constituent assembly was called, which had come about under a new electoral law. The until then unconstitutional part of the country Pyrmont had also sent members to this meeting . In May 1849 Waldeck had a new constitution. On August 8, 1851, the government imposed a new electoral law. A voter had to be a citizen, over 25 years old, self-employed and innocent, who had the right to stand as a candidate, who had been a citizen for at least three years. The choice was straightforward. In 1856 the Landtag accepted the government proposal that the right to vote became indirect class and census suffrage. In the following years there was a dispute over a new right to vote; instead of real estate, the Liberal Chamber wanted to make property and education eligible for election. From 1867, the formally still independent principality was administered by Prussia.

Saxony

Constitutional suffrage

The constitutional charter for the Kingdom of Saxony of September 4, 1831 provided for an assembly of estates with two chambers. Members of the first chamber were the royal princes, owners of the class lords, elected and appointed by the king manor owners, four evangelical prelates, and a Catholic professor elected by the professors of the University of Leipzig, and the first magistrates of the eight larger cities. The second chamber consisted of representatives of the manor owners, representatives from the cities, from the rural areas and from the commercial and industrial sectors, that is, the rural and urban bourgeoisie. Only the manor owners directly elected their representatives; all other voters were limited to electors. In 1833 the primary voters for the Second Chamber made up about ten percent of the population.

Male suffrage of property owners

In the spring of 1848, Saxony, like almost all states of the German Confederation, was hit by uprisings and democratic movements. On March 13, 1848, the Könneritz government resigned because they feared armed struggle and the proclamation of a republic. The new government, chaired by Karl Hermann Alexander Braun, submitted to the second chamber on March 22, 1848 a draft electoral law that adhered to a bicameral system and did not provide for general, equal and direct elections. The government withdrew the draft because the necessary constitutional majority did not appear. On September 2, 1848, the government presented a new draft. This led to a compromise: the bicameral system was retained, but the elections were direct and equal, but not yet general. According to the electoral law of November 15, 1848, elections to the Second Chamber took place in 75 constituencies without the intervening of electors. All men of legal age who were either citizens of a town or who had full civil property in the country in a property they lived in were entitled to vote, as well as their housemates and members of the army. After the May Uprising was put down and martial law was imposed, a new, conservative Saxon government ordered new chamber elections in September 1849. The elections again resulted in a slim majority for the democratic left. This came into conflict with the government over Germany's policy, as the government initially joined the Erfurt Union, which was initiated by Prussia, but later rejected the Erfurt Union with Austria. On June 1, 1850, the king and government dissolved the chambers. In a coup d'état they had the old assembly of estates convened again according to the constitution of 1831 and with the composition of May 21, 1848.

Return to the state suffrage of 1831

The newly convened meeting of the estates approved the measures of the king and government and put the constitution and the electoral law of 1831 back into force. He also continued to support its reaction policy, such as a restrictive press law that became a model in the German Confederation in 1854.

Male suffrage also for taxpayers

The election law of October 19, 1861 increased the number of representatives of the trade and factory sector from five to ten, so that the Second Chamber had 80 seats. In the urban and rural constituencies, in addition to the owners of their inhabited properties, men who paid two thalers in property taxes or direct personal state taxes were also eligible to vote, and in the larger cities three thalers. The right to vote was extended, but only those who paid direct state tax could vote; a system change did not take place. The elections were secret. Ref :.

Loss of class privileges - taxpayers' right to vote for men

Saxony joined the North German Confederation in 1866, for which Bismarck, for reasons of foreign policy, had envisaged the general, direct, equal and secret male suffrage, which he perceived as damaging domestically. To approximate this to a limited extent, the right to vote was extended in 1868 to all men who were either the owners of a property provided with a residence or who paid a thaler in direct personal state taxes. Belonging to certain population groups was no longer important. That was a change of system. Due to the electoral law of 1868, only 9.9 percent of Saxon citizens could vote. Under the electoral law of the North German Confederation, twice as many men would have been eligible to vote.

Three-class suffrage

The election for the Estates Assembly in 1893 resulted in 14 seats in the Second Chamber for the Social Democrats. When the Social Democrats demanded the same, direct, secret right to vote in the Second Chamber for male citizens over the age of 21 and women, the arch-conservative Interior Minister von Metzsch presented a draft of a new electoral law at the suggestion of the Conservative MP Paul Mehnert in February 1896. It was a three-tier suffrage, similar to that in Prussia, but slightly toned down. The draft was approved by both chambers in next to no time on March 28, 1896, before a broad protest movement could develop. The elections were kept secret, but electors were reintroduced. Between 1871 and 1918, this was the only case in which the right to vote in a German country experienced such a reactionary decline, moreover with left-wing liberal support.

In the first department, which elected a third of the electors, the primary voters were those who paid at least 300 marks a year in taxes. In contrast to the Prussian, the Saxon three-class suffrage had a maximum limit, the state property and income tax that someone paid only came up to the amount of 2,000 marks., In the second department, which also elected a third of the electors, came as primary voters who paid at least 38 marks and or who accounted for the second third of the total tax amount of the constituency. In the third department, which also elected a third of the electorate, came the many who accounted for the last third of the total tax bill for the constituency. The maximization limit did not help the primary voters of the third division. But there were more primary voters in the first section. Primary voters in the second division also benefited to a small extent from this. In Prussia, on the other hand, a strong taxpayer could, in not so rare extreme cases, choose the electors of his department alone. In the first two ballots, a candidate needed an absolute majority to be elected; in the third, a relative majority was sufficient. One candidate remained elected for six years, and one third of the seats were renewed every two years.

In Prussia, the Bethmann Hollweg government wanted to soften the strict Prussian three-class suffrage similar to the Saxon three-class suffrage, but abandoned this effort in 1910 because there was no majority in favor of it in the conservatively dominated Prussian state parliament. In 1901 the Social Democrats lost their last chamber mandate in their stronghold of Saxony, which contributed to their radicalization.

Plural suffrage

From 1907 to 1909, mass rallies and demonstrations for democratic electoral reforms, initiated by social democrats, took place in Saxony. The National Liberals moved away from the three-tier suffrage. The king and parts of the government felt that reform was necessary. To change the electoral law, however, a constitution-changing two-thirds majority was required, so that the conservatives who had previously benefited from the electoral law forced several revisions of a draft law presented by Interior Minister Wilhelm von Hohenthal. As an inadequate compromise, a plural vote came about on May 5, 1909 . It was still unequal: The census was abolished and everyone had a basic vote, but some voters received additional votes, whereby they were only allowed to have a maximum of four votes each:

- 1-3 additional votes for high income;

- An additional vote for the middle school leaving certificate (for those who were allowed to do one-year voluntary military service instead of normal service)

- an additional vote for voters over fifty years of age

In addition, all seats have now been reassigned every six years, again directly. Whoever achieved an absolute majority in the constituency was elected, with a runoff if necessary.

Mecklenburg

The Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz had the Rostock hereditary comparison as an old-class constitution since April 18, 1755. The national union was called a common national corporation. The state union consisted, on the one hand, of a knighthood, which in 1848 made up about 640 manors suitable for the state assembly with a corresponding number of seats. It could also be a matter of commoners who had acquired such an estate; that number rose. On the other hand, the state union consisted of a landscape that represented the 44 cities eligible for state parliament. The cities sent representatives of the magistrates (city governments) for this purpose. Together with the commoners in the knighthood, the representatives in the landscape had a majority. But there were also cases in which both knighthood and landscape had to come together.

In 1848 the liberal movement required the Grand Dukes to convene a constituent assembly. But these faced the problem that they had to ask the state union for approval if they did not want to commit a coup. Finally, on March 18, 1848 , Grand Duke Friedrich Franz II announced the appointment of an extraordinary state parliament. A new electoral law drawn up by the latter was put into force on July 15, 1848 by the Grand Duke by promulgation. It introduced the general and equal suffrage for the (indirect) election of the constitution-agreeing state parliament (October 3 in Mecklenburg-Schwerin, October 9 in Mecklenburg-Strelitz). Male citizens over 30 were allowed to vote.

The constitution-agreeing state parliament met on October 31, 1848, with a third leaning towards the liberals and another towards the radical democrats. On August 3, 1849, the state parliament passed the Mecklenburg constitution with a census suffrage and a right of veto for the sovereigns. While the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin had put the constitution into effect, the highly conservative Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz refused and declared the state parliament to be dissolved. He did not have the right to do so, but the constitution could not come into force without his consent.

The dispute over the constitution led to the separation of the two grand duchies. The state parliament decided this on August 19, and Grand Duke Friedrich Franz II of Schwerin dissolved it with legal effect on August 22. On October 10th, he put the state constitution into effect and repealed the old constitution and its bodies by law. The Strelitz Grand Duke, however, had a decision brought about by the Arbitration Court of the Erfurt Union, the Freienwalder arbitration award of September 11, 1850. This declared the state constitution of 1849 null and void, since according to Art . The reaction policy reached both Mecklenburg, and on February 15, 1851 the old state parliament met again.

Hanseatic cities

In Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck the old-class constitutions existed again after the Napoleonic period, from 1813/1814. The main body was a senate, which co-opted its patrician members for life. In addition, there was a citizenry representing the established bourgeois upper class; the latter body was only allowed to deliberate or to decide together with the senate. Here, too, in 1848 the revolutionaries had to take the traditional patrician-oligarchic system into account.

The Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg had had a constitution since 1528 that provided for three (different sized) colleges in addition to the Senate. They corresponded in a way to the First Chambers elsewhere. The citizenship was accordingly a kind of second chamber. It consisted of rich landowners ( hereditary residents ) and foremen of the guilds ( elderly people ).

Several citizens 'deputations in the Vormärz did not bring about the change from the estates to the representative constitution, and a new council and citizens' deputation also failed to make progress in the March Revolution. Finally, in August political associations demanded the appointment of a constituent body , the Senate accepted this on September 7, 1848. It was elected at the end of 1848 under equal and universal suffrage, and in February 1849 it began its work. Negotiations were unsuccessful and a constitution was not adopted until 1860. According to her, all citizens were allowed to vote for the citizenship who paid taxes. In addition, the Senate remained equal. The introduction of a new census in 1906 went down in history as an electoral steal .

The Free Hanseatic City of Bremen also had an old-class city constitution from the time of the Reformation. In 1814 it was changed so that the Senate was no longer co-opted, but elected by the Citizens' Convention. The Senate now consisted of four mayors and 24 senators and the Citizens' Convention of 500 members who were appointed by the Senate President for life. There were also 20 senior men, the most respected large merchants. On March 14, 1848, the citizens' convention decided, with the approval of the Senate, to elect a constituent citizenship. Its constitution, which she had agreed with the Senate, came into force on April 18, 1849. The Senate therefore stepped alongside the citizenship, which was to be composed according to universal and equal suffrage. In response time, a new constituent assembly in eight classes was elected. The constitution of 1854 made the Senate back into government.

The revolution had it easy in the Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck , as the Senate and the citizenship were in favor of reforming the 17th century city constitution as early as March. An agreed new constitution came into force on April 8, 1848, the earliest state constitution of the revolution. According to this constitution, only citizens divided into five class classes were allowed to vote, according to the revised version of December 30th, the residents were also allowed to vote, according to universal and equal suffrage. It stayed that way, with a few changes, until the November Revolution.

Frankfurt until 1866

The Free City of Frankfurt , a member state of the German Confederation, had since October 18, 1816 a constitution with the constitutional amendment act with a senate as executive and a permanent citizen representation as a supervisory body. The 42 members of the Senate and 61 members of the Permanent Citizens' Representation were co-opted by electoral bodies and appointed for life.

The Legislative Body was responsible for legislating, approving and collecting taxes, approving the budget and overseeing the state budget. It consisted of 20 senators, 20 members of the permanent citizen representation and 45 indirectly elected citizens. All male Frankfurt citizens of Christian denomination were entitled to vote . Elections were made in class I for nobles and scholars, class II for traders and class III for tradespeople. The economically dependent and those who did not have full citizenship were not allowed to vote. These included Jews , residents (who did not have enough assets to acquire citizenship), foreigners (also known as permissionists , i.e. newcomers who were only allowed to be in the city with a special permit) and rural residents in the eight villages in the area of the Free city. Rural residents received active and passive voting rights in 1823, Jews only in 1864.

Thuringian duchies

The Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach had a constitution since May 5, 1816. In the March Revolution, an electoral law was passed on November 17, 1848, which introduced universal and equal suffrage. According to the state election law of April 10, 1909, one had to be a citizen of a municipality in order to be eligible to vote. The larger landowners elected five of the 38 members of the state parliament ; They had to have real estate in Germany that was farmed for agriculture or forestry and assessed at least 3000 marks for state income tax. Five other MPs came from the other highest taxed persons, whose income was taxed at least 3000 marks. The Senate of the University of Jena, the Chamber of Commerce, the Chamber of Crafts and the Chambers of Labor each elected one member. The 23 remaining members of the state parliament were elected according to property, tax and occupation.

The Grand Duchy of Saxony-Altenburg , which became independent in 1826, had a constitution since April 29, 1831. On April 10, 1848, the electoral law granted subjects a general, direct right to vote. Before the First World War, voters were divided into three classes according to their tax burden. Each class represented a third of the total amount of tax in the constituency; the first class consisted of the voters with the highest tax amounts, etc. Each class elected one MP per constituency.

In the Duchy of Saxony-Meiningen-Hildburghausen , which was also created in 1826, there was a constitution since August 23, 1829, and the electoral law of June 3, 1848 promised universal, direct elections. Before the First World War, the state parliament had four members who were elected by those large landowners who paid at least 60 marks in property or building tax per year. Four came from the highest taxable persons with an assessment of at least 3,000 marks for income tax. The other eligible voters elected 16 MPs. The election was secret and based on the principle of absolute majority with a runoff.

The Duchy of Saxony-Coburg-Saalfeld had had a constitution since August 8, 1821 ; the duchy of Saxony-Coburg and Gotha , formed in 1826, introduced universal and equal suffrage with the electoral law of April 22, 1848.

In the other small states of Thuringia, too, elections were held in 1848, mostly based on direct voting rights. Reuss-Greiz was the straggler in November; It was not until March 1867 that Reuss a.L. received a constitutional-monarchical instead of an estate constitution. In most of the states in the Thuringian region, the aristocracy and the larger landed property had an artificially created stronger position than the landed property of peasants and citizens. Electoral laws with partially privileged voting rights were introduced around 1870.

In Schwarzburg-Sondershausen , the state parliament had a maximum of six members before the First World War, whom it appointed prince for life. Six were directly elected out of the three hundred highest taxed. The remaining voters chose a further six members through electors. Those who had not paid taxes or were more than a year in arrears were excluded from voting.

Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt had a state parliament with four constituency members of the highest taxable population, who paid at least 120 marks in direct taxes a year; and 12 constituency members of the remaining voters who paid direct state taxes. The elections were direct and secret.

In Reuss a. L. the sovereigns appointed three members of parliament. The manor owners and the other landowners elected two and the other eligible voters seven members. To be eligible to vote, you had to own your own household and pay direct taxes.

In Reuss j. L. elected the highest taxable three and the remaining eligible voters 17 members. You had to have the right to vote in a local parish in the principality and be assessed for income tax.

Anhalt duchies

None of the Anhalt-Dessau , Anhalt-Köthen and Anhalt-Bernburg duchies had a constitution before 1848, only a common landscape (a state parliament) from 1625. Since the estates had no influence, the duchies were ruled in a de facto absolutist way. The government of Anhalt-Köthen was installed by the Duke of Anhalt-Dessau after the local ruler died childless, and in 1853 both duchies were united.

In the March Revolution, the Duke of Anhalt-Dessau appointed a liberal ministry. State parliaments were convened in Anhalt-Dessau and Anhalt-Köthen to deliberate on a constitution, and they united to form a joint state parliament on July 31, 1848. The constitution of October 29, 1848 (with the electoral law of February 24, 1849) was decidedly left-wing, abolished the nobility and even set up workers' commissions.

In Anhalt-Bernburg there was a conflict between Herzog and the state parliament elected on July 31, 1848. The Duke wanted to impose a constitution according to his ideas. The state parliament, in turn, declared the duke unfit to rule on November 29, 1848. The Duke then dissolved the Landtag and put his own constitution into effect, which was to be revised by agreement by the newly elected Landtag.

Since 1863 there was a united Duchy of Anhalt . According to the landscape and rules of procedure of September 17, 1859, the state parliament had 36 members. The duke appointed two members for the term of office; The highest taxed landowners (at least 63 marks property tax) elected eight, the highest taxed traders and traders (at least 18,000 marks assessment for income tax) two, the other eligible voters in the cities elected 14 and the other eligible voters in the flat country ten. Voters and voters had to be at least 25 years old. The secret election was indirect for the city and flat country MPs. In the years before World War I, the election was direct and secret; 27 members of the state parliament were elected by the cities and the country, two were appointed by the duke and 17 were elected by groups such as the landowners and professional representatives.

Federal states with non-German rulers

Holstein and Lauenburg until 1866

The duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg had been member states of the German Confederation since 1815, but had a non-German sovereign in the form of the Danish king. Together with the Danish Duchy of Schleswig they were part of the multiethnic Danish state until the German-Danish War in 1864 , although Lauenburg had only come to the state as a whole in 1814/15 to compensate for the loss of Norway . Holstein and Lauenburg were imperial fiefs of the Roman-German Empire before 1806 , whereas Schleswig was an imperial fief of Denmark . While the Danish king in Schleswig had a double function as king (feudal lord) and duke (vassal), he ruled in Holstein and Lauenburg exclusively in his function as duke and as such was a north German sovereign.

As in other countries, a liberal movement developed in the duchies in the 19th century, which, however, was soon marked by a dissent between German and Danish national liberals. According to the Federal Act of 1815, state constitutions were to be established in the individual member states. Lauenburg already had a state constitution, but Holstein did not. German National Liberals ( German: Schleswig-Holsteiner ) took this as an opportunity to demand the admission of Schleswig to the German Confederation and a common constitution for Schleswig and Holstein. Danish national liberals ( Eiderdän ), on the other hand, demanded a constitution for Denmark, including Schleswig, and were ready to cede Holstein and Lauenburg for this purpose. Both national liberal groups were alike in their demands for civil liberties, as they were deeply divided on the national question about the mixed-language Schleswig. In view of the French July Revolution of 1830 and a pamphlet by the lawyer Uwe Jens Lornsen , who called for a common constitution for Schleswig-Holstein, the Danish king decided in 1831 to have four advisory assemblies for the Danish islands (based in Roskilde ), North Jutland (based in Viborg ), Schleswig or Sønderjylland (based in Schleswig , later Flensburg ) and Holstein (based in Itzehoe ), which first met in 1834. The king did not comply with the demand of the Schleswig-Holstein nobility ( Schleswig-Holstein Knighthood ) for a joint state parliament for Schleswig and Holstein. The Schleswig-Holstein government was established at Gottorf Castle as an intermediary to the Schleswig-Holstein-Lauenburg Chancellery in Copenhagen . The members of the Estates Assemblies were partly elected, partly directly appointed by the King. The right to vote was linked to a high land ownership census, so that only about 3% of the residents were able to exercise the passive and 1.5% of the residents the active right to vote. Women and those who did not own were excluded from the start. Jews had the right to stand as elector, at least in the kingdom, but in the duchies they were denied both the right to stand and vote. The minimum age was 25 years. The turnout was 76 percent from autumn 1834 to January 1835.

The assemblies of the estates therefore only represented a fraction of the population and only had an advisory function. Denmark itself remained an absolutist monarchy until 1848/49. Nevertheless, the Schleswig and Holstein assemblies of the estates soon became a forum for national political contradictions. This was particularly evident in the language question. While the colloquial language in Schleswig was largely Danish and Frisian, the administrative language in the entire Duchy was German. This led to protests by the Danish National Liberals. In 1842 , Hjort Lorenzen consciously addressed the delegates of the Schleswig Estates Assembly in Danish , which had previously met in German. The German delegates, in turn, openly called for Schleswig to join the German Confederation. Another point of conflict developed in view of the expected extinction of the male line of the Oldenburg rulers in Copenhagen. While the female branch line was fully entitled to inheritance under the Danish royal law, the Lex Salica valid in the German duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg only permitted male succession. The German-dominated assemblies of estates in Schleswig and Holstein demanded the recognition of Christian August from the Augustenburg branch, but this was rejected by the Danish side with reference to the Danish royal law. As a result, the assemblies of the estates dissolved themselves in 1846.

In 1848 a draft constitution for the entire state was already being discussed when the first reports of unrest in France and some German states became known. In Copenhagen this led to the Danish March Revolution and the formation of a government in which the Danish National Liberals were also involved for the first time ( March Ministry ). In Kiel, on the other hand, a German-minded provisional government was formed , which subsequently initiated the so-called Schleswig-Holstein uprising . In Copenhagen there were plans to call a constituent assembly. The king should appoint only a quarter of the members for this, the remaining delegates should be allowed to be elected by all men over thirty who had their own hearth and who registered in good time for the election. Instead of 32,000 as in the state elections, 200,000 residents could now vote. The Imperial Assembly began on October 23, 1848. The draft for a constitution of Denmark was based on the Belgian one and created a bicameral system with Landsting and Folketing ; it was adopted on May 25, 1849 with a large majority. The question of the involvement of Schleswig was left open here. The Landsting as the first chamber was elected indirectly through the local districts; whoever wanted to be elected had to be at least 40 years old and earn at least 1200 Reichstaler per year. The Folketing, as the second chamber with a hundred members, was directly elected in one-man circles;

The provisional government for Schleswig-Holstein that was formed in Kiel at the same time had a constituent assembly called up to draft a constitution according to which a state assembly should be composed half by equal electoral law and half by class elections.

In Lauenburg, on the other hand, the March Revolution had replaced the estate knight and landscape with the democratically elected state assembly . This consisted of 21 members. Of these, 12 were determined by general elections and 9 by elections by landowners. In 1850 the state assembly was dissolved and the old knight and landscape re-established as the state parliament. In 1853, King Lauenburg's state parliament added further peasant delegates.

After the First Schleswig War , the entire Danish state was restored. The previous assemblies of estates for Schleswig and Holstein were convened again and continued their work until the German-Danish War in 1864. In the London Protocol of 1852, the great powers established the state as a "European necessity". In addition, the female lineage was recognized by the great powers in Holstein and Lauenburg. In view of the demands of the respective national liberal parties to join Schleswig either to a Danish nation state or to the German Confederation, it was held that the duchies should remain in the state as a whole. In 1951, the Danish government finally introduced language rescripts in the mixed-language parts of Schleswig, which replaced the previous purely German church and school language and instead introduced a Danish school language and a mixed church language. The Frisian-speaking areas, which were assigned to the area with the sole German church and school language, were excluded from this. Denmark also promised to introduce a constitution for all of Denmark (but without incorporating Schleswig) towards Austria and Prussia. However, the entire state constitution ( Fællesforfatning ) passed in 1855 was rejected by the Holstein assembly of estates and repealed in 1858 by the German Confederation for the states of Holstein and Lauenburg. The Danish government then passed the November Constitution in 1863 , which, however, was viewed by the German side as a breach of the London Protocol and ultimately led to the federal execution of Holstein and Lauenburg by federal troops in December 1863. On February 2, 1864, Prussian and Austrian troops finally crossed the Eider against the protest of the German Confederation, with which the German-Danish War began. After the end of the war, the three duchies received Austrian and Prussian governors; after the German-German War in 1866, the areas finally became completely Prussian.

Luxembourg until 1866

Luxembourg had been a Grand Duchy since 1815, the Grand Duke of which was King William I of the Netherlands . He administered the Grand Duchy without its own constitution and like a Dutch province. The Grand Duchy belonged to the German Confederation and also had a federal fortress under a Prussian commander. When the southern Dutch provinces declared themselves independent as Belgium in 1830 , a Belgian governor was installed for Luxembourg. This was based in Arlon , in the western part of the Grand Duchy. But he also claimed power over the eastern, purely German-speaking, and had elections held there for the constituent assembly of Belgium. Only Luxembourg City and Luxembourg Fortress were able to repel the Belgian uprising. The Dutch king asked for help from the German Confederation; Ultimately, the crisis was resolved by dividing Luxembourg. The remaining Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (the former eastern part) belonged to the German Confederation as before.

In the elections to the Belgian constituent assembly ( Congrès national in French, Volksraad in Dutch) on November 3, 1830, strict census suffrage was applied, even more restrictive than for the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Intellectuals such as those practicing a liberal profession, clergymen, as well as high political functionaries and civil servants, with the exception of teachers (who were often loyal to the Dutch king) and civil servants of Dutch origin, were also allowed to vote. Ironically, the Belgian revolutionaries had recently protested against the officials-dominated representative bodies in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. With the right to vote for clergymen, their support for the new state was strengthened and the element hostile to Holland in the country was strengthened. In the elections themselves there were irregularities such as inadequate voter lists or tendentious counts. Eligible to vote were 45,000 (male) Belgians over 25 years of age, of whom 30,000 voted.

On September 12, 1841, King Wilhelm II of the Netherlands gave the Grand Duchy a constitution with a parliament called the “estates”. According to her, men over 25 years of age with Luxembourg nationality and civil rights with residence in the respective constituency (Canton) voted according to an indirect census right to vote. The necessary tax burden was ten guilders per year, and twenty guilders for eligibility as an elector. To be eligible you had to have lived in the country for a year. Electors and voters were not allowed to have legal counsel or to be sentenced to certain sentences. In addition, certain civil servants, clergymen, military personnel below the rank of captain, elementary school teachers, and the sons and sons-in-law of members of the estates were not allowed to belong to the estates.

Wilhelm II and the estates agreed a new constitution on July 9, 1848. It abolished the constitutional status of the census. Electors and voters were not allowed to receive poor relief. No members of parliament were allowed: members of the government and civil servants, as well as military personnel below the rank of captain. However, the constitution made it possible to introduce further requirements for electors and members of parliament. According to the election law of July 23 of that year, the census was ten francs. It listed numerous detailed provisions, for example on election day (a Tuesday) and the times for the “election business”. The voters had to gather at the polling station and were called by name to hand over their locked ballot to the electoral officer.

When Luxembourg no longer belonged to a German state association, it received a new constitution in 1868, which introduced direct elections and limited the electoral census. In 1919, universal and equal suffrage with proportional representation was introduced.

Limburg 1839–1866

The German Confederation had lost the western part of Luxembourg in 1839 and should be compensated for it. To compensate for this, Belgium divided its province of Limburg and returned the eastern part to the Netherlands. This eastern part became the Dutch province of Limburg and was considered the Duchy of Limburg together with Luxembourg as a federal member. Its three votes in the Federal Assembly were cast by the representative of the Dutch king. Like Luxembourg, Limburg did not belong to the new German state after the end of the German Confederation in 1866.

The representative bodies of the Dutch provinces are called Provinciale Staten (Provincial Estates). Initially, they were elected from three estates, knights, townspeople and country. Since the great constitutional reform in 1848, there has been a census vote. Limburg had 195,425 inhabitants in 1839, of which 1.42 percent had the right to vote and 0.38 percent to stand for election. Until the reform, the members of the first chamber of the national parliament were still appointed by the king, since then they have been elected by the provincial estates.

Prussia 1848 to 1918

Before 1848 there were only provincial parliaments composed of estates in Prussia , and the United Landtag of 1847 did not change anything. With this meeting the king wanted to appease the liberals and get support for the financing of the state railway. For the Liberals, this meeting of provincial representatives did not go far enough, while the Conservatives saw it as a dangerous step towards a constitutional constitution. And in fact, historically, the United State Parliament had the importance of giving liberal politicians from all over Prussia the opportunity to meet and exchange ideas.

Constitutions in Prussia since 1848

In the revolution of 1848 there were then general elections for the Prussian National Assembly , according to an electoral law passed by the second United State Parliament . The election in May was general, insofar as all adult men could vote who had lived in the same place for at least six months and were not receiving poor relief. The election was indirect, as the primary voters elected a college of electorates, which then elected the MPs. The National Assembly was shaped by liberals and left-wing liberals.

The National Assembly did not succeed in enforcing its draft constitution, but it indirectly compelled the king to set up a constitution and a Prussian parliament himself. Because it came about without an agreement with the National Assembly, it is called the enforced constitution . The first was from December 1849 and still included universal suffrage in the National Assembly. But in April 1849 this was abolished again, after which the right to vote was general, but unequal.

Mansion

The composition of the mansion was initially controversial. According to the first, “imposed” constitution, this chamber was to be elected by the representations of the provinces, districts and districts to be set up later (Art. 63). The electoral law of December 6, 1848 provisionally elected the rich. The high census ensured that some of the chamber members belonged to the landed nobility.

However, the king wanted to appoint the members himself and, during the revision, enforced that the manor house should consist of three groups (Art. 65). 120 members were to inherit their membership or (up to a tenth of the number of the first group) were appointed by the king. The remaining 120 members were to be elected: three quarters from the constituencies, one quarter from the municipal councils of the larger cities. The actual composition of the chamber was delayed, however, and finally the House of Representatives authorized the King in 1853 to regulate the composition himself. Since 1854 the manor has only known hereditary or appointed members. Members were certain members of the nobility and the landed property, deserving citizens appointed by the king, holders of the four major state offices, representatives of the ten state universities elected by the full professors, certain representatives of the cities. In 1911 there were 260 aristocratic and 87 civil members of the manor house.

House of Representatives and the three-tier suffrage