Grand Duchy of Berg

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

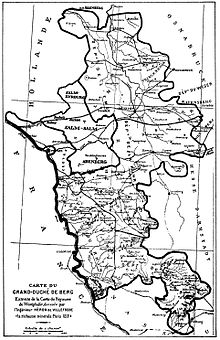

The Grand Duchy of Berg (also Grand Duchy of Kleve and Berg , French Grand-Duché de Berg et de Clèves ) was a Napoleonic satellite state that existed from 1806 to 1813 . The capital was Düsseldorf , where the former Jesuit monastery , the governor's palace on Mühlenstrasse and Benrath Palace served as government seats. The core of the Grand Duchy of Berg emerged from the Duchy of Berg and was formed from numerous other territories with different, mixed confessional traditions. As a founding member of the Rhine Confederation , the country left the Holy Roman Empire on August 1, 1806 . First ruled by Joachim Murat and then from July 1808 by Napoleon himself, the de jure sovereign Grand Duchy was de facto a satellite state of the French Empire . In addition to the Kingdom of Westphalia , it was to serve as a model state for the rest of the Confederation of the Rhine and as a buffer state ("État intermédiaire") to secure France against Prussia .

There were reforms of the administration, the judiciary, the economy and agricultural reforms. The Bergisch army fought in various campaigns during the coalition wars .

In 1808, the Grand Duchy of Berg bordered the French Empire ( Département de la Roer , Département de Rhin-et-Moselle ), the Kingdom of Holland , the Principality of Salm , the Duchy of Arenberg-Meppen , the Kingdom of Westphalia , the Grand Duchy of Hesse and the Duchy Nassau . From 1811, after the French annexation of Bergisch areas north of the Lippe , the Grand Duchy bordered two of the so-called Hanseatic departments of the French Empire in the north , the Département de la Lippe and the Département de l'Ems-Supérieur .

In the short period of its existence, no significant national or national awareness could develop in the country. Last but not least, it played a role that, for various reasons, neither the landed aristocracy nor the bourgeoisie or the lower classes supported the system as one. Triggered by economic crises and displeasure against the drafting of troops , serious unrest broke out in 1813, which was suppressed militarily (→ " Knüppelrussenaufstand "). After the collapse of Napoleonic rule, most areas fell to the Kingdom of Prussia as a result of the Congress of Vienna .

history

Time under Murat

The historical starting point for the emergence of the Grand Duchy of Berg was created by the Peace of Pressburg , with which France successfully ended the Third Coalition War after the Battle of Austerlitz in December 1805 and thus began to integrate a number of German states into an alliance under French hegemony . A few months later this led to the fall of the Holy Roman Empire and the foundation of the Rhine Confederation . On March 15, 1806, King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria ceded his Duchy of Berg to Napoleon . Kurbayern committed itself to this in the Treaty of Schönbrunn in 1805 in exchange for the Principality of Ansbach . On the same day, Napoleon transferred sovereignty over the duchies of Berg and Kleve to his brother-in-law, the French prince Joachim Murat , who initially became a German imperial prince for a few months . The territory of the February 15, 1806 Prussia ceded Duchy of Cleves (which according to 1795 / 1797 / 1801 / 1803 remaining rechtsrheinische rest) was connected to the Duchy of Berg. Murat took his land in Cologne on March 19, 1806, initially as Duke of Kleve (Cleve) and Berg, and eight days later received homage from the estates in Düsseldorf. From 1806 to 1808 , Jean Antoine Michel Agar implemented Murat's directives as Minister of Finance, Provisional Minister-State Secretary and President of the Bergisches Staatsrat . During his rare stays, Murat used the governor's palace on Mühlenstrasse in Düsseldorf, which had already taken on the features of a government district in the Palatinate era, and Benrath Palace .

In July 1806 Murat declared on the basis of the Rhine Confederation Act and in the course of the establishment of the Rhine Confederation, the exit from the Holy Roman Empire . With effect from 1 August 1806, he claimed, with mutual recognition of the signatory , the sovereignty and the Act of Confederation, adopted in accordance with Art. 5 the title of Grand Duke of. A little later, after the defeat of Prussia at Jena and Auerstedt and the peace of Tilsit , the Klevisch-Bergische Grand Duchy was expanded. By January 1808, the following, mostly formerly Prussian, areas were added: the monasteries of Elten , Essen and Werden , the county of Mark with Lippstadt , the hereditary principality of Münster , the principality of Rheina-Wolbeck , the county of Salm-Horstmar , the counties of Tecklenburg along with the rule of Rheda and Lingen , the former imperial city of Dortmund and the Nassau areas around Siegen and Dillenburg . The city of Wesel , however, became part of France in January 1808; their well-developed fortress also served as the control of the Grand Duchy.

Direct Napoleonic rule

According to the Treaty of Bayonne of July 15, 1808, Napoleon appointed Joachim Murat King of Naples and from this point took over control of the Grand Duchy of Berg in personal union with the French Empire. The personal union of France and Berg avoided an annexation , which was not permitted under the Rhine Confederation Act. Michel Gaudin (until December 31, 1808), Hugues-Bernard Maret (January 1, 1809 to September 23, 1810) and Pierre-Louis Roederer (September 24, 1810) acted as Minister-State Secretaries for Affairs of the Grand Duchy of Berg to the imperial government of Paris 1810 to November 1813). The Imperial Commissioner Jacques Claude Beugnot, as head of administration of the Grand Ducal Government in Düsseldorf, was in constant correspondence with them. In this respect, the Grand Duchy could hardly play an independent political role. In April 1808 the Grand Duchy of Berg reached an area that it would not exceed in the following period.

On March 3, 1809, Napoléon appointed his four-year-old nephew Napoléon Louis Bonaparte Grand Duke of Berg. He was the eldest living son of the King of Holland and the brother of the later Napoleon III. Since Napoléon Louis was not yet of legal age and since Napoléon did not want to let his brother Louis, the King of Holland, rule over the Grand Duchy of Berg due to serious differences of opinion about the implementation of the continental blockade, the Emperor preferred to take over the Bergisch regency himself.

After the abdication of the King of Holland on July 1, 1810, the Grand Duchy of Berg was linked to the Kingdom of Holland in personal union for a few days because, following the abdication of his father, the five-year-old Grand Duke von Berg had also become King of Holland. This personal union came to an end with the French annexation of Holland on July 9, 1810. The Grand Duchy was initially spared from an annexation. It was not until December 13, 1810 that the French Senate decided to annex the Klevian and Bergisch areas north of a line from the Lippe via Haltern , Telgte to Borgholzhausen in order to enforce the continental barrier , in order to incorporate them into the newly created departments of Ober-Ems and Lippe .

In 1811 Napoleon visited the Grand Duchy and its capital, Düsseldorf, with the aim of personally discussing and inspecting the difficulties that arose - for example through contacts with personalities from the Bergisch administration and economy. In order to keep the Bergische population in favor of France and for him as Berg's regent, he had a Bergische trade exhibition organized, which he also attended, ordered a beautification of the city fortifications of Düsseldorf, which had been removed from 1801, and made a certain sum of money available for this. The urban planning “embellissement” was gradually implemented by the commissioned planners, in particular Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe , with a system of boulevards, esplanades and landscaped parks.

Reforms and internal development

As a model state, there were numerous reforms in the administration, the judiciary and other areas in the Grand Duchy. However, this phase only began after Murat, who only spent a short time in his dominion, changed to Napoleon in 1808. Unlike in the Kingdom of Westphalia, a real constitution was not introduced. Unlike there, the reforms were not carried out on the basis of a constitution, but by means of ordinances. In contrast to the Kingdom of Westphalia, where the French model of state organization was introduced at one stroke, the Grand Duchy proceeded more cautiously. The imperial commissioner and representative of Napoleon in Düsseldorf, Jacques Claude Beugnot, also warned against hasty steps.

Legal system

The Civil Code was introduced as the basis for case law in 1810. The pénal Code was also introduced. Two years later, the judicial organization was reorganized according to the French model. This included both the French court proceedings and the notarial code. With this, the separation of the administration of justice was finally completed. When the French system was introduced, modifications were made - mainly implemented by local officials - in order to better take regional requirements into account. Basically the equality of all was realized before the law. In practice, however, the implementation of the new judiciary proved difficult. The judicial staff were often not familiar with the new regulations.

From 1806, a state police under the name "Landjäger" was formed from the Bergische Security Corps and the Dillenburg Hussars.

Administrative structures

A council of state, which was not called that until 1812, was responsible for government and legislation. Officials from the annexed areas were represented. At first the Council of State was passed over by Beugnot, who saw in this a limitation of his position of power. But when problems arose with the enforcement of French legislation, Beugnot was forced to fall back on the expertise of the members of the Council of State. Since then, this has been more involved in legislation. The Council of State could not work against French policy, but it could change it. This ultimately differentiated Bergisch law from French law.

The reform of the administrative structures based on the French model was of considerable importance. The basic aim, similar to France, was to strengthen the power of the central authority, for example by abolishing the self-government of the municipalities and pushing back intermediate powers. It was also about strengthening administrative efficiency. At the top were specialist ministers. The former Elector of Cologne governor in Vest Recklinghausen and marshal of the knighthood of the Duchy of Berg, Johann Franz Joseph von Nesselrode-Reichenstein , was Minister of the Interior, later Minister of War and Minister of Justice. Beugnot himself was finance minister. In 1812 this office fell to Johann Peter Bislinger , formerly a member of the Bergisches Landesdirektorium.

In August 1806, the Duchy of Berg was initially divided into four districts ( arrondissements ):

Düsseldorf , Elberfeld , Mülheim am Rhein and Siegburg ; the Duchy of Kleve in two districts: Duisburg and Wesel .

By an imperial decree signed in Burgos on November 14, 1808 , the Grand Duchy of Berg was administratively divided into four departments (for example: provinces), twelve arrondissements (administrative districts) and 78 cantons (districts). The smallest administrative units were the mairies (mayor's offices ). The departments were the Rhine department with the Düsseldorf prefecture , the Sieg department with the Dillenburg prefecture , the Ruhr department with the Dortmund prefecture and the Ems department , which was annexed by France in 1811, with the Münster prefecture . In December 1808, the municipal administration for the cities and municipalities finally replaced the former bailiwicks , monies and offices.

The communities were brought under state control; this ended the local self-government. Smaller communities were merged. Department, arrondissement and municipal councils were formed. However, these were appointed and not elected. Germans, mostly aristocrats, were appointed as prefects of the departments. The Maire (mayor) was also appointed. In industrial communities such as Elberfeld , Barmen (both now part of Wuppertal ), Mülheim an der Ruhr or Iserlohn , these were often merchants or manufacturers, in more rural communities, but also in Münster , they were often local aristocrats.

The appointed municipal councils had little authority and only met once a year. Also on these councils were mostly local notables , following the French example . Between 1806 and 1815 there were a total of 43 men on the city council of Düsseldorf. 14 of them were bankers or merchants and five were lawyers. In doing so, attention was paid to non-denominationalism. Protestants also sat on the council in the predominantly Catholic Düsseldorf. Overall, the reforms pushed back the dominance of the old urban elites.

Deficit of the political constitution and representation

There was never a written constitution in the Grand Duchy. The French representatives on site in particular were opposed to a proper constitution. Napoleon himself did not want to be bound by a constitution in his decisions. Various elaborated drafts therefore had no effect.

Already under Murat there were considerations about a representative body to replace the old estates . Since this was initially bound to a codified constitution, it did not come to that for the time being. After representative bodies had been formed at various subordinate levels as a result of the reform of the administrative structures of 1808, the old assembly of estates had become inoperable. There were no reactions from the population. It was not until Napoleon's visit to Düsseldorf in 1811 that there was renewed movement in the question of state representation. This should essentially resemble the imperial estates of the Kingdom of Westphalia . With this, however, Napoleon met the resistance of Commissioner Beugnot, who saw problems in keeping the organ politically compliant.

In 1812 an organic statute was issued, which provided for the establishment of a council of state and a representation of the country on the basis of the census suffrage; it bore the title Imperial Decree, which concerns the organization of the Council of State and the College . The implementation slowed down and ultimately got stuck. The election was delayed and there were often not enough candidates because the cantons often did not have the required notables . It was not until the beginning of 1813 that electors were appointed. The constitutional reform did not get beyond this modest step.

Denominational and educational policy

The population of the Grand Duchy was religiously mixed because the country was made up of different territories with different beliefs and denominational histories. About half were Protestants, the other half Catholics. The Rhenish and Münsterland areas were mostly Catholic, the Bergisches Land , Siegerland and the Brandenburg Sauerland were Protestant . In addition, there was a small Jewish population, which made up about 4,000 to 5,000 people. The secularization of the monasteries had begun even before the founding of the Grand Duchy . The episcopal seats in Cologne and Münster were vacant and were administered by chapter vicars. In 1811 Napoleon ordered a reorganization of the parishes, based on the new administrative boundaries. This, as well as the establishment of a diocese in Düsseldorf, never came about. The clergy were paid by the state. There was no significant reform of the school system. With decrees of December 1811, after his visit to the Grand Duchy, which took place in early November 1811, Napoleon Bonaparte ordered that the Düsseldorf Palace, which was destroyed by the cannons of the French Revolutionary Army in 1794 , should be restored and set up as the seat of a university with five faculties.

Emancipation of the Jews

The Jewish minority was partially emancipated, following the example of the Kingdom of Westphalia: special taxation and “letters of protection” were abolished by the finance minister on July 22, 1808, and full civic equality was not achieved. The three central Napoleonic decrees of 1808 (family names, consistories, commercial activity) that had been issued for France did not come into force in the Grand Duchy. The legal autonomy of the former regional rabbi Löb Aron Scheuer (1736-1821) was revoked. Since the introduction of the civil code, Jews have been under state jurisdiction.

Economic and agricultural reforms

Preliminary high points of the administrative and legal reforms were the formal abolition of the feudal system and serfdom (December 1808), the abolition of feudalism (January 1809), the abolition of the guilds, the ban on mills, the wineries and pensions as well as the general freedom of trade (March 1809 ). This favored the emergence of a modern economic bourgeoisie. There were also fundamental reforms of the judiciary, the post office, administration and educational policy. The national survey , which was initiated in 1805, in particular for taxation purposes, was continued with the significant contribution of the astronomer and geodesist Johann Friedrich Benzenberg . The agrarian reform proved difficult. It was not even possible to convert the confusing taxes of the farmers into a removable basic rent . Numerous replacement decrees were issued, but failed in practice. Finally, the French mortgage regime was also transferred to the Grand Duchy. In principle, the payments had thus become basic rents, and the farmer could in principle freely dispose of his land by buying, selling or exchanging. In 1808 Napoleon issued a decree abolishing serfdom and transferring full land rights to the former serfs and tenants. Another decree followed in September 1811, after which all non-private feudal property titles were extinguished. But the law came too late to have any effect. The nobility also often ignored the regulations. Under pressure from the nobility and against the background of the imminent Russian campaign , the government even stopped all peasant trials against the previous landlords in 1812. Hardly anything changed in the situation of the farmers, as the transfer fees were too high. For the nobility, on the other hand, the reforms meant a deep cut. He largely lost his feudal rights, the de facto monopoly on certain offices and his tax privileges. Based on the French model, patrimonial estates and entails were subject to state approval.

Many peasants responded with protests to the resistance of the nobility to the state's peasant liberation initiatives. Their cause was supported by Arnold Mallinckrodt and his newspaper, the " Westfälischer Anzeiger ". A delegation brought a petition from the peasants to Paris, where Napoleon received it and ultimately vainly promised to remedy the situation.

economy

First, the country's economy experienced an upswing. Berg's commercial economy was particularly important for the Napoleonic system because in France itself the negative consequences of the revolution for the local economy had not yet been overcome. Therefore, France initially granted the Grand Duchy a favorable tariff . However, Berg then suffered severe damage when the Napoleonic continental system was introduced , which increased the tariff barriers. This effectively cut the country off from the French, Italian and Dutch markets. Berg's exports fell from 55 million francs in 1807 to just 38 million in 1812. A number of entrepreneurs reacted by relocating their businesses to the left (French) bank of the Rhine . The Bergisch entrepreneurs therefore demanded the full connection of the country to France. However, this was rejected with concern that there would be overwhelming competition for French products. The Grand Duchy benefited little from smuggling against the continental barrier. Instead of exporting to France, the Grand Duchy's economy now had to concentrate on trade in the German area. The geographical shift in trade from the coast to the inland, particularly to the Rhine, also strengthened individual economic sectors in the Grand Duchy. In 1811 Friedrich Krupp founded a cast steel factory together with partners in Essen - precisely under the favorable conditions of the continental dam, which prevented the import of English cast steel - which formed a crystallization core of the industrialization of the Ruhr area.

The center of the textile industry was the area around Barmen and Elberfeld. Even before the founding of the Grand Duchy, cotton production and processing gained in importance. The development stagnated after 1806 due to the customs policy. 50,000 people were already employed in this area in the Grand Duchy. Iron production and processing experienced a significant boom during the time of the Grand Duchy. The small-scale production of finished metal goods, such as knives in Solingen , was particularly important here . Overall, this sector was still comparatively small with 5000 employees.

Bergische Post

Under the direction of the French postal inspector Du Preuil, the postal facilities of the Imperial Post Office operated by Thurn und Taxis , which had previously carried out the postal services in the Duchy of Berg, were confiscated in May 1806 at the behest of Duke Joachim. Du Preuil, who acted under the supervision of the Bergische Finance Ministry and was soon appointed General Post Director Bergische , began to organize the postal system of the Bergische Post according to French requirements and models, whereby a special connection with the post in northern Germany had to be taken into account. In 1809 the Bergische Post also took over the post in the Duchy of Arenberg-Meppen and in the Principality of Salm . On the instructions of Napoleon, suspicious postal items were inspected and observed in the Bergische post offices, also in order to uncover measures against the continental blockade.

military

According to the international legal provisions of the Rhine Confederation Act , the Grand Duchy had to provide troops and pay for the army in the event of a military conflict. For many residents, the introduction of compulsory military service was something new. It contributed significantly to the growing discontent against the regime.

As early as 1806, the 1st Bergische Line Infantry Regiment was set up in Düsseldorf. In 1808 two more regiments of the same type were added. A fourth followed in 1811. In addition, there were mounted artillery , foot artillery and technical units. A first cavalry unit was set up in 1807 ( Chevau-légers du Grand-duché de Berg ). Originally it was Chevaulegers with splendid uniforms based on the Polish model. The character later switched to a unit of hunters on horseback with a simple green uniform. In 1810 she was fitted with lances and defined as a lancer . A second cavalry unit followed around 1812. From 1808 the flags of the grand ducal Bergischen associations carried the motto Et nos Caesare duce (literally: "We too, under the leadership of the emperor"). In doing so, they expressed that Emperor Napoleon, as regent of the Grand Duchy, was their immediate commander-in-chief.

In particular, the Bergische Cavalry received recognition. Since 1808 she belonged to the Imperial Guard during the Spanish campaign and distinguished herself in various battles and skirmishes. The foot troops were used in the siege of Graudenz in 1807 and in the war against Austria in 1809. A large part of the Bergische troops took part in the Russian campaign . Some of the Bergisch miners and sappers belonged to the guard artillery. A large part of the Bergisch cavalry fell into Russian captivity during the Battle of the Beresina . Out of 5,000 men, only 300 arrived in Marienwerder in January 1813.

In 1806 the country had 3,000 men. In 1813 the Bergische troops were 9,600 strong. The commanding officer was François-Étienne Damas . Most of the officers , however, were Germans. Many recruits tried to escape the drafts by fleeing . They evaded to Holland or the Grand Duchy of Hesse . The new soldiers had to be prevented from escaping by the gendarmes . In Lüdenscheid and Unna there were unrest as a result of levies. In order to prevent desertions, the Bergische units were mainly deployed in distant theaters of war, for example in Spain or in the Russian campaign. In 1813 the authorities only managed to raise a force of 1200 men. Some of the Bergisch soldiers went to the Prussian camp after the Battle of Leipzig .

After the victory of the Allies, the Bergisch units were incorporated into the Prussian army . The infantry became the 28th and 29th Prussian Infantry Regiment . The 11th Prussian Hussar Regiment emerged from the cavalry after intermediate stages .

Riots in 1813 and the end

Overall, the effectiveness of the reform policy, which lasted only five years, remained limited. Above all, unlike in the areas on the left bank of the Rhine, where the French period lasted about twenty years, there were no real political leaders in the population. The landed gentry remained skeptical about the agricultural policy, the majority of the population suffered from social hardship and from conscription. The economic bourgeoisie, which tended to benefit from the reform policy, remained aloof as a result of the failed economic policy.

It was clear to the imperial commissioner Beugnot that it was difficult to create a "fatherland" from numerous former territories. In fact, the Grand Duchy remained an art state. After Napoleon's defeat in Russia, the mood began to openly turn against French rule. The authorities knew that the officials in the county of Mark were still secretly loyal to the Prussian king and that there were relations with the Freiherr von Stein . At the beginning of 1813, serious unrest flared up against the new troop levies. In many places the rebels were called " stick Russians or Speck Russians ". The uprisings started in Ronsdorf and spread across more and more areas such as Solingen, Velbert , Wipperfürth , Elberfeld, Hagen , Gummersbach or Herborn . Economic problems also played a role. This survey is considered to be one of the first open uprisings against Napoleonic rule in Germany. The revolts could only be suppressed by military means. Troops from the neighboring Kingdom of Westphalia under the command of the Salmian Hereditary Prince Florentin also helped.

Soon after the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig , the Grand Duchy effectively dissolved. The top French officials took the Bergische Staatskasse and left the Grand Duchy. On November 10, 1813, a vanguard of the Allied armies entered Düsseldorf under the Cossack General Yussefowitsch, who was hailed as a liberator by the population. He was followed by a Russian army corps under Lieutenant General Count St. Priest and Prussian troops. From 1813 to 1815 the former Duchy of Berg and the gentlemen was in the area Gimborn , Homburg and Wildburg the General Berg set up as interim administration, initially under the direction of Karl Justus Gruner , who arrived in Dusseldorf on 13 November 1813th The northern and eastern parts of the Grand Duchy fell to the interim Generalgouvernement between the Weser and the Rhine , based in Münster .

Most of the territory of the Grand Duchy finally fell to Prussia through Article XXIV of the main acts of the Congress of Vienna and was absorbed into the two new Prussian provinces of Jülich-Kleve-Berg , based in Cologne, and Westphalia , based in Münster. The far north of the Grand Duchy with the former counties Bentheim and Lingen became part of the Kingdom of Hanover .

The title of Grand Duke of Kleve and Berg went to the Prussian king, Friedrich Wilhelm III. , and the House of Hohenzollern over.

Despite the extensive restoration of the old rulership and legal relationships, in many parts of the Rhineland of the former Grand Duchy - similar to France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, large parts of Italy, parts of Poland and some German countries - the French judicial system and the civil code remained in force, where they developed in a specific legal tradition of " Rhenish Law " until 1900.

Further development

On January 1, 1814, the Grand Duchy of Berg itself, with the canton of Gummersbach and the municipality of Friesenhagen, was divided into four districts, each with a director. Unlike the previous prefects and sub-prefects, these no longer had the police administration under themselves. The newly divided districts were Düsseldorf , Elberfeld , Mülheim and Wipperfürth .

The superordinate was the district of Düsseldorf, whose director was also state director. He also led the administration of the state fire health insurance fund and the presidium of the medical council, which was responsible for the medical system as well as the medical and medical police in all circles. The administrative police commanded a police director in Düsseldorf, who was subordinate to a police bailiff in each of the cantons .

In 1822 the province of Jülich-Kleve-Berg was united with the province of Grand Duchy of Lower Rhine, also formed in 1815 (administrative seat in Koblenz ) to form the Rhine province .

In 1946 the northern part of the Rhine province was united with the province of Westphalia to form the new state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the former Bergische capital Düsseldorf was designated the capital of North Rhine-Westphalia. The new country - since 1949 the country of the Federal Republic of Germany - presents itself as the successor to the Grand Duchy of Berg in terms of history, legal succession, size, location and capital.

Grand dukes

- Joachim Murat (March 15, 1806 to July 15, 1808)

- Napoleon Bonaparte (July 16, 1808 to March 2, 1809)

-

Napoléon Louis Bonaparte (March 3, 1809 to November 1813)

- Regent: Napoléon Bonaparte (March 3, 1809 to November 1813)

Minister-State Secretaries

- Jean Antoine Michel Agar (summer 1806 to July 1808, full-time, official residence in Düsseldorf)

- Michel Gaudin (August 1808 to December 31, 1808, part-time, official seat in Paris)

- Hugues-Bernard Maret (January 1, 1809 to September 23, 1810, part-time, official seat in Paris)

- Pierre-Louis Roederer (September 24, 1810 to November 1813, full-time, official seat in Paris)

swell

- Johann Josef Scotti (edit.): Collection of laws and ordinances which were passed in the former Duchies Jülich, Cleve and Berg and in the former Grand Duchy of Berg on matters of state sovereignty, constitution, administration and administration of justice. From the year 1475 to the Royal Prussian state government that took office on April 15, 1815. 4 vol. Düsseldorf, 1821–1822 ( online version ).

- Entry on archive.nrw.de

- Justice organization of the Grand Duchy of Berg: division of the country, names of judicial officials, lawyers and notaries; de Dato au Palais de Tuileries on December 17th 1811 . Kerschilgen, Düsseldorf 1812 ( digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf ).

- Klaus Rob (arrangement): Government files of the Grand Duchy of Berg 1806–1813 (= sources on the reforms in the Rhine Confederation states , edited by the Historical Commission at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1). Munich 1992.

- Law Bulletin of the Grand Duchy of Berg . Düsseldorf, 1810-1813 ( digitized version ).

- Décret impérial sur la circonscription territoriale du Grand-Duché de Berg: avec le tableau des départements, districts, cantons et communes dont il se compose . Dänzer & Leers, Düsseldorf 1809 ( digitized version ).

- Collection of government negotiations for the Grand Duchy of Berg . Düsseldorf, 1806 ( digitized edition ).

- Collection of ordinances and regulations for the factory courts in the Herzogthume Berg . Lucas, Elberfeld 1841 ( digitized edition ).

- Collection of laws, ordinances and notices that were issued in the former Grand Duchy of Berg and in the current district of Düsseldorf on the elementary school system: from 1810 to z. Conclusion d. J. 1840 . 2nd Edition. Lucas, Elberfeld 1841 ( digitized edition ).

literature

- Gerd Dethlefs, Armin Owzar , Gisela Weiß (ed.): Model and Reality. Politics, culture and society in the Grand Duchy of Berg and in the Kingdom of Westphalia. Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-506-75747-0 .

- Elisabeth Fehrenbach : From the Ancien Regime to the Congress of Vienna . Oldenbourg, Munich 2001.

- Bastian Fleermann: Marginalization and Emancipation. Everyday Jewish culture in the Duchy of Berg 1779–1847 (= Bergische Forschungen, Vol. 30). Neustadt an der Aisch 2007.

- Meent W. Francksen: State Council and Legislation in the Grand Duchy of Berg (1806–1813) (= Legal History Series, Vol. 23). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-8204-7124-3 (334 pages).

- Stefan Geppert, Axel Kolodziej : Romerike Berge - magazine for the Bergisches Land , 56th year, issue 3/2006: special edition on the occasion of the exhibition Napoleon in the Bergisches Land . September 1 to October 22, Bergisches Museum Schloss Burg, ISSN 0485-4306 .

- Rudolf Göck: The Grand Duchy of Berg under Joachim Murat, Napoleon I and Louis Napoleon 1806–1813. A contribution to the history of French foreign rule on the right bank of the Rhine; mostly according to the files of the Düsseldorf State Archive. Cologne 1877 ( online ).

- Mahmoud Kandil: Social protest against the Napoleonic system of rule. Statements by the population of the Grand Duchy of Berg 1808–1813 from the perspective of the authorities . Mainz Verlag, Aachen 1995, ISBN 3-930911-58-2 (177 pages; also Diss. Phil. Fernuniversität Hagen 1995; partial document online ).

- Erwin Kiel, Gernot Tromnau (ed.): Vivre libres ou mourir! Live or Die Free! The French Revolution and its reflection on the Lower Rhine . Exhibition 13. Duisburger Akzente . Accompanying document. Niederrheinisches Museum, Duisburg 1989 (without ISBN).

- Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the West. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Verlag Aschendorff, Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-402-05489-5 .

- Charles Schmidt : Le grand-duché de Berg (1806-1813). Étude sur la domination française en Allemagne sous Napoléon Ier. Paris 1905 ( online ). German translation: The Grand Duchy of Berg 1806–1813. A study on French supremacy in Germany under Napoleon I. With contributions by Burkhard Dietz , Jörg Engelbrecht and Heinz-K. Junk, ed. by Burkhard Dietz and Jörg Engelbrecht, Neustadt an der Aisch 1999, ISBN 3-87707-535-5 .

- Bettina Severin: Model State Policy in Rhineland Germany. Berg, Westphalia, Frankfurt in comparison. In: Francia (journal) Vol. 24, H. 2, 1997, pp. 181-203 ( digitized version ).

- Bettina Severin-Barboutie: French rule politics and modernization. Administrative and constitutional reforms in the Grand Duchy of Berg (1806–1813). Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58294-9 ( digitized version ).

- Veit Veltzke (ed.): Napoléon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser. Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-17606-8 .

- Veit Veltzke (ed.): For freedom - against Napoleon: Ferdinand von Schill , Prussia and the German nation . Böhlau, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20340-5 .

Web links

- Grand Duchy of Berg (1806–1813) , website of the Rhineland Regional Council on Rhenish history

- State archive NRW:

- Entry on his-data.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Page 264 , Art. 7: Traité de Bayonne, a small supplementary contract, not identical to the actual Bayonne Treaty , which affected Spain as a whole. (French) The abbreviation SAI in the source means Son Altesse impériale , which corresponds to the salutation to persons belonging to the Imperiali (noble family) . The following letter "R." means Rex or Roi, King.

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach : From the Ancien Regime to the Congress of Vienna . Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, pp. 53, 82.

- ↑ Bettina Severin Barboutie: French government policy and modernization: administrative and constitutional reforms in the Grand Duchy of Berg (1806-1813) . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2008, p. 29.

- ^ Johann Georg von Viebahn : Statistics and topography of the government district of Düsseldorf . Düsseldorf 1836, p. 63.

- ↑ Representation of the international law exchange agreements between France, Bavaria and Prussia with reference to written sources in: Otto von Mülmann : Statistics of the government district of Düsseldorf . In: Commercial statistics from Preussen , Third Part, Volume 1, published by J. Baedeker, Iserlohn 1864, p. 370 ff. ( Online ).

- ↑ Quoted from Charles Wilp : Düsseldorf 'Vorort der Welt'. Dazzledorf. Publisher Melzer, Dreieich 1977.

- ↑ Axel Kolodiej: Departments, Arrondissements, Cantons and Marien - The middle and lower administrative structures of the Grand Duchy of Berg using the example of Barmen . ( Memento of the original from April 1, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) bgv-wuppertal.de, p. 6; Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia . Münster 2008, p. 34.

- ↑ a b Jörg Engelbrecht: Civil reforms and imperial power politics on the Lower Rhine and Westphalia. In: Veit Veltzke (Ed.): Napoleon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser . Cologne 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ Jörg Engelbrecht: On the way from the corporate to the civil society. Reform Processes in Germany in the Age of Napoleon ( online version ).

- ↑ Armin Owzar: Between divine grace and constitutional patriotism . Political propaganda and critical public in Napoleonic Germany . In: Veit Veltzke (Ed.): Napoleon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser . Cologne 2007, pp. 138-139.

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach: From the Ancien Regime to the Congress of Vienna . Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, p. 87.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Münster, 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Bettina Severin: Model State Policy in Rhineland Germany. Berg, Westphalia, Frankfurt in comparison . In: Francia 24/2 (1997), pp. 193-194.

- ↑ Police in the Grand Duchy of Berg ( Memento of the original from March 30, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Münster 2008, p. 34.

- ^ Bettina Severin: Model State Policy in Rhineland Germany. Berg, Westphalia, Frankfurt in comparison . In: Francia 24/2 (1997), p. 190.

- ^ Bettina Severin: Model State Policy in Rhineland Germany. Berg, Westphalia, Frankfurt in comparison . In: Francia 24/2 (1997), pp. 195-196.

- ^ Johann Josef Scotti: Collection of laws and ordinances… , Volume 3 (Grand Duchy of Berg). Wolf, Düsseldorf 1822, p. 1008 ( Bonn State Library ).

- ^ JF Wilhelmi: Panorama of Düsseldorf and its surroundings . JHC Schreiner'sche Buchhandlung, Düsseldorf 1828, p. 23.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Münster 2008, pp. 33-36.

- ^ Bettina Severin: Model State Policy in Rhineland Germany. Berg, Westphalia, Frankfurt in comparison . In: Francia 24/2 (1997), p. 189.

- ^ Imperial decree concerning the organization of the Council of State and the College (PDF; 1.2 MB).

- ↑ Veit Veltzke: Napoleon's trip to the Rhein and his visit to Wesel 1811 . In the S. (Ed.): Napoleon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser . Cologne 2007, p. 46.

- ↑ Bettina Severin-Barboutie: variants Napoleonic model state policy. The imperial estates of the Kingdom of Westphalia and the College of the Grand Duchy of Berg . In: Veit Veltzke (Ed.): Napoleon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser . Cologne 2007.

- ↑ Law Bulletins of the Grand Duchy of Berg No. 16, 1811 (p. 282 ff.) And No. 26, 1811 (p. 804 ff.). Reproduced in: Wolfgang D. Sauer: Düsseldorf under French rule 1806–1815 . In: Documentation on the history of the city of Düsseldorf (Pedagogical Institute of the State Capital Düsseldorf), October 1988, p. 47, 138.

- ↑ Decree on the Adoption of Official and Hereditary Family Names (July 20, 1808)

- ^ Réglement organique du culte mosaïque (Creation of the Consistories) (March 17, 1808)

- ^ "Shameful decree" ("decret infame", March 17, 1808)

- ↑ Fundamental: Bastian Fleermann: Marginalization and Emancipation. Everyday Jewish culture in the Duchy of Berg 1779–1847. Neustadt an der Aisch 2007.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Münster 2008, pp. 36–37.

- ^ ROB, Government Acts (1992), pp. 35-147; Francksen: State Council and Legislation in the Grand Duchy of Berg. 1982, pp. 61-73.

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach: From the Ancien Regime to the Congress of Vienna . Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, pp. 91-93.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Münster 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Otto R. Redlich: Napoleon I and the industry of the Grand Duchy of Berg . In: Contributions to the history of the Lower Rhine. Yearbook of the Düsseldorf History Association . Volume 17, Düsseldorf 1902, pp. 188 ff. ( Online ).

- ↑ Entry by traders in the Grand Duchy of Berg 1811 Online version with explanations ( memento of the original from May 24, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach: From the Ancien Regime to the Congress of Vienna . Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, pp. 99, 102.

- ↑ Ironically , in the late 19th and 20th centuries , the Krupp cast steel factory, which was founded in 1811 as a result of the French continental blockade and which was later nicknamed the armory of the empire , was one of the main reasons for French fears of Germany and the resulting Ruhr issue .

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach: From the Ancien Regime to the Congress of Vienna . Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, pp. 103-104.

- ^ Justus Hashagen : Napoleon and the Rhineland . In: Die Rheinlande , year 1907, issue 4, p. 128 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Eckhard M. Theewen: The Army of the Grand Duchy of Berg . Veit Veltzke (ed.): Napoleon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser . Cologne 2007, p. 265.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Münster 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ Veit Veltzke (ed.): Napoleon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser . Cologne 2007, p. 266.

- ^ Jörg Engelbrecht: Civil reforms and imperial power politics on the Lower Rhine and Westphalia . In: Veit Veltzke (Ed.): Napoleon. Tricolor and imperial eagle over the Rhine and Weser. Cologne 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia. Münster 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ cf. in detail: Mahmoud Kandil: Social protest against the Napoleonic system of rule in the Grand Duchy of Berg 1808–1813 ( online version ).

- ↑ Wolfgang D. Sauer: Düsseldorf under French rule 1806-1815. In: Documentation on the history of the city of Düsseldorf (Pedagogical Institute of the State Capital Düsseldorf), Düsseldorf 1988, Volume 11, p. 199.

- ↑ Filippo Ranieri : The role of French law in the history of European civil law . In: Werner Schubert, Mathias Schmoeckel (Ed.): 200 years of Code civil. The Napoleonic Codification in Germany and Europe . Legal history writings, Volume 21, Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-412-35105-9 , p. 89 f.