Kingdom of Württemberg

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Württemberg was a state in the southwest of what is now Germany. It came into being on January 1, 1806 as a sovereign kingdom at the instigation of the French emperor , Napoleon Bonaparte , who was striving for political hegemony . The kingdom emerged from the Duchy of Württemberg (elevated to an electorate in 1803 ) . Its original area, also known as Altwuerttemberg , had recently been greatly expanded by the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss and the Peace of Pressburg, mainly in the south and east, and had thus almost doubled its geographical area.

From 1806 to 1813, Württemberg was a member of the Rhine Confederation, which was geared towards the interests of France, and after the end of the Napoleonic wars , following the resolutions of the Congress of Vienna from 1815 to 1866, a member of the German Confederation . After the Franco-German War of 1870-71 joined the Kingdom of the as - small German - Empire proclaimed under Prussian leadership Germany's first nation-state as the state of.

On the basis of the constitution of 1819, an early constitutional monarchy developed over the years with relatively strong liberal and democratic currents compared to many other German states, which continued even after the suppression of the largely peaceful German revolution of 1848/49 in Württemberg could maintain and reinforce.

As a result of the German defeat in World War I and the November Revolution of 1918, King Wilhelm II of Württemberg, one of the last German monarchs, renounced the throne. Württemberg was converted into a parliamentary democracy and as a people's state remained part of the German Empire in the Weimar Republic .

In 1952, its former sovereign territory was opened in what is now the state of Baden-Württemberg .

geography

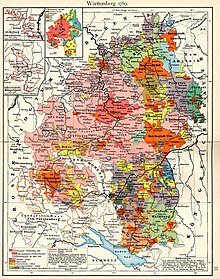

The former Kingdom of Württemberg in its borders from 1813 onwards lay between 47 ° 34 'and 49 ° 35' north latitude and between 8 ° 15 'and 10 ° 30' east longitude. The greatest extension from north to south was 225 kilometers, the greatest width from west to east 160 kilometers. The borders had a total length of 1,800 kilometers. The total area was 19,508 km². In the east, Württemberg bordered the Kingdom of Bavaria , in the north and west on the Grand Duchy of Baden and in the south until 1850 on the principalities of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and Hohenzollern-Hechingen , which from 1850 belonged to Prussia as the Hohenzollern Lands , and on Lake Constance . There were various exclaves , enclaves and other territorial features along the border with Baden and Hohenzollern . Due to the Wimpfen exclave , Württemberg also shared a border with the Grand Duchy of Hesse .

The former borders of Württemberg at Baden and Hohenzollern can no longer be found on a political map of present-day Germany since they were blurred when the district reform in Baden-Württemberg came into force on January 1, 1973. Until this reform, the borders were still present in the administrative districts of North Württemberg and South Württemberg-Hohenzollern , and the structure of the districts also coincided with these external borders. In contrast, the areas of the Protestant regional church (not exactly, because including the Hohenzollern Lands ) and the Catholic Diocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart (exactly, because without the Hohenzollern Lands) correspond to the old borders of Württemberg to this day.

The hills and mountains in the north include the plains of the Triassic Formation with valleys rich in wine and fruit, while in the south the plateau of the Jura formation . The climate is Central European temperate in Upper Swabia , in the central Neckar area and in the north, but significantly rougher in the higher areas of the Swabian Alb , the Allgäu and the Black Forest . The mean annual temperature varies between 6 and 10 ° C depending on the area. The abundant forests ensure abundant rainfall. The most important rivers are the Neckar with its tributaries Fils , Rems , Enz , Kocher and Jagst , the Tauber and the Danube with its tributary Iller , which forms the border with Bavaria for 56 kilometers. The area extends over the main European watershed . 70 percent of the area is drained towards the Rhine, 30 percent towards the Danube. There are important mineral springs in Bad Wildbad and Bad Cannstatt . Larger lakes are the Bodensee and the Federsee in Upper Swabia. The highest point is the Dreifürstenstein at 1,151 meters on the Hornisgrinde in the Black Forest, the highest mountain peak at 1,118 meters is the Black Ridge near Isny in the Allgäu . The lowest level is at 125 meters near Böttingen , where the Neckar flows from Württemberg to Baden. The mean height of Württemberg is about 500 meters above sea level .

history

Creation of the Kingdom

In the 18th century, the Duchy of Wirtenberg essentially consisted of the former ancestral land in the central Neckar area around Stuttgart and the associated possessions in the northern Black Forest and the Swabian Alb . In addition to the area around Heidenheim , the county of Mömpelgard on the left bank of the Rhine was the most important exclave of the duchy. In addition, there were other smaller exclaves to the left of the Rhine in what is now French territory with the county of Horburg and the village of Reichenweier . After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, which restricted the privileges of the nobility and clergy, coalitions were formed among the European monarchies with the aim of stopping the development of the republic in France. The first coalition agreed between Emperor Leopold II and the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm II in the Pillnitz Declaration was soon followed by other monarchies. On April 20, 1792, the First Coalition War broke out , which revolutionary France won. In the Peace of Campo Formio on October 17, 1797, Emperor Franz II recognized the Rhine as the eastern border of France. Mömpelgard and the other holdings on the left bank of the Rhine in Württemberg were also affected . The duchy then participated from 1799 as a partner of Austria in the second coalition against France under Napoleon Bonaparte . In the spring of 1800 the French occupied Württemberg. Since Austria made no efforts to defend the country, Duke Friedrich II of Württemberg and his troops had to join the retreat of the Austrians. After this humiliation, his confidence in the alliance with Austria was deeply shaken. In the Treaty of Lunéville on February 9, 1801, he came to terms with France. His aim was to enlarge the territory on the right bank of the Rhine. The Paris Treaty of May 20, 1802 secured the existence of the duchy and promised compensation for the areas on the left bank of the Rhine. Württemberg had the seat and the right to vote in the extraordinary Reich Deputation , which prepared the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss , which stipulated the compensation for the lost possessions of German princes on the left bank of the Rhine. Duke Friedrich was made electoral prince . Numerous small rulers were mediatized and added to the new electorate under the name Neuwuerttemberg . These included the mediatized imperial cities of Aalen , Giengen an der Brenz , Heilbronn , Rottweil , Esslingen am Neckar , Reutlingen , Schwäbisch Gmünd , Schwäbisch Hall and Weil der Stadt as well as the following secularized ecclesiastical possessions: the Prince Propstei Ellwangen , the Reichsabbey Zwiefalten , the Knight Comburg , the Kloster Heiligkreuztal at Riedlingen , the convent Schoental , the convent Margrethausen , the pin Supreme box and the pin-murische part of the village Dürrenmettstetten. These gains corresponded in total to an area of 1609 square kilometers with 110,000 inhabitants and 700,000 guilders tax revenue. This contrasted with around 388 square kilometers of lost area on the left bank of the Rhine with around 14,000 residents and around 250,000 guilders in government income. The Minister Normann-Ehrenfels was entrusted with setting up the administration of Neuwuerttemberg .

On October 3, 1805, Friedrich concluded another alliance with Napoleon in Ludwigsburg . Wuerttemberg then took part in the Third Coalition War with troops on the French side . In the Treaties of Brno (December 10–12, 1805) and the Peace of Pressburg of December 26, 1805, Upper Austria was divided between Württemberg, Bavaria and Baden . This meant that another 125,000 new residents were added to the Electorate of Württemberg. Specifically, the following territories were concerned: Grafschaft Hohenberg , Landvogtei Schwaben , Herrschaft Ehingen , the so-called Danube cities Mengen , Munderkingen , Riedlingen and Saulgau as well as in the Unterland areas of the Teutonic Order (Amt Hornegg with Neckarsulm and Gundelsheim ), areas of the Order of St. John and smaller territories of the imperial knighthood . Württemberg was elevated to a sovereign kingdom with effect from January 1, 1806. The previous name Wirtenberg was replaced by the more modern spelling Württemberg . The first king was the previous Duke and Elector Friedrich II under the name Friedrich (own name: King Friedrich I.). With the signing of the Rhine Confederation Act on July 12, 1806, Württemberg left the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . With the Rhine Confederation , another 270,000 new residents were added to the Kingdom of Württemberg, who were spread over the territories of the principalities and counties of Hohenlohe , Königsegg-Aulendorf , Thurn and Taxis , Waldburg and many other dominions in Upper Swabia .

Development in the first few years

In 1809 King Friedrich participated with troops in the suppression of the Tyrolean uprising . With the Peace of Schönbrunn on October 14, 1809, the Kingdom of Württemberg was expanded to include the areas of the Teutonic Order near Mergentheim , and an uproar among the local population was bloodily suppressed. Finally, with the Treaty of Paris on February 28, 1810 and the related border treaties with Bavaria and Baden, the number of inhabitants increased by another 110,000. In addition, there were mainly Crailsheim and Creglingen as well as the former imperial cities of Bopfingen , Buchhorn , Leutkirch , Ravensburg , Ulm and Wangen and areas of the former county of Montfort . In return, the old Württemberg rule of Weiltingen fell to the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Upper Office Hornberg and the Office St. Georgen to the Grand Duchy of Baden . In 1813, the Kingdom of Württemberg acquired the Hohenzollern rule of Hirschlatt . Overall, Württemberg had thus increased from originally 9,500 square kilometers with around 650,000 inhabitants to 19,508 square kilometers with around 1,380,000 inhabitants.

In the years 1812/13 King Friedrich participated in Napoleon's war against Russia , from which only a few hundred of 15,800 Württemberg soldiers returned. Despite this defeat, the kingdom initially remained on the side of France as a member of the Rhine Confederation until Napoleon suffered another devastating defeat in the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813. Only then did Württemberg switch to the Sixth Coalition , which was led by Austria, Prussia and Russia. On November 2, 1813, King Friedrich changed direction after Austria had guaranteed the country to preserve its property and its sovereignty through the Treaty of Fulda.

The area growth in Württemberg was not revised by the territorial reorganization of Germany at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and was thus indirectly confirmed under international law . Due to the participation in the coalition wars and their consequences, the kingdom experienced an economic decline in its early years, which led to high national debt and the impoverishment of large sections of the population up to famine. This economically very difficult situation was exacerbated by the unusually cold year 1816, which was marked by natural disasters . The emigration to Eastern Europe and North America increased by leaps and bounds.

In the first years of the kingdom, the involvement of Württemberg in the armed conflicts and loyalty to France ensured King Frederick extensive freedom of action in domestic politics. Their goal was the consistent modernization of the administration and the merging of the various territories into a unified and centrally managed state. This was all the more difficult since the newly added areas brought a considerable Catholic minority to the previously pure and strictly Protestant Württemberg . The means of modernization were the rigorous abolition of the privileges of respectability in Old Wuerttemberg and of the nobility in the newly acquired territories. Resistance to this policy was rigorously fought; a police ministry, a secret police force and a censorship authority were set up on the French model. Important reforms in the first few years were the separation of justice and administration, the division of the country into higher offices and districts, the abolition of internal tariffs and the equal rights of the Catholic and Reformed denominations with the former Evangelical-Lutheran state denomination.

During the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna, the goal was to establish a federal constitution for the newly constituted Germany . The first draft of the concept for a confederation of states was submitted by Metternich to the assembly of the German states on May 23, 1815. Württemberg opposed this federation together with Bavaria. Because King Friedrich wanted to pre-empt the federal constitution with his own constitution, he submitted a constitution to the state parliament, which was convened on March 15, 1815. Württemberg only signed the German Federal Act on September 1, 1815 and thus only subsequently joined the German Confederation founded on June 8, 1815 . The draft of the Basic State Law met with strong opposition from the estates , who wanted to reinstate the constitution based on the Tübingen Treaty of 1514. The estates managed to get the population on their side in a campaign for the old law . One of the protagonists of this movement was the poet and politician Ludwig Uhland , who wrote the poem The old, good law especially for this purpose . The campaign was so effective that the constitutional constitution presented by King Friedrich was not passed. The completely revised constitution was only issued by his successor, King Wilhelm I, on September 25, 1819.

Political consolidation after King Wilhelm I took office

The relationship between King Friedrich and his son Wilhelm Friedrich Karl , later King Wilhelm I, was marked by strong tensions, both personally and politically. In 1805, Wilhelm openly rebelled against his father, which led to his flight to Paris. Wilhelm tried to bring France to overthrow in Württemberg, which Napoleon refused to do. In 1807 Wilhelm and Friedrich reached an understanding politically; but their personal and political aversion to one another remained. So it was only logical that the new king took over the reign on October 30, 1816, not with the name of his father, but with the name Wilhelm and initiated a comprehensive change of policy. It has been handed down that the population of Württemberg could hardly be kept from celebrating Friedrich's death by soldiers. Together with his wife Queen Katharina , a daughter of the Russian Tsar Paul I , Wilhelm’s policy in his first years in office was strongly oriented towards alleviating the economic hardship of broad sections of the population. Katharina, who died on January 9, 1819 at the age of only 30, devoted herself to social welfare with great commitment. The founding of the Katharinenstift as a girls' school, the Katharinenhospital , the Württembergische Landessparkasse , the University of Hohenheim and other institutions go back to her. When he took office, Wilhelm issued an amnesty and implemented a comprehensive administrative reform on the basis of the new, modern constitution of September 25, 1819. The absolutist dictatorship of Frederick was not replaced by the dualism between the regent and the estates inherited from the Duchy of Württemberg. Instead, the new form of government was based on constitutionalism , which supplemented the rule of the monarch with constitutionally established say for elected representatives. The constitution thus became a link between the old and the new parts of the country. The old-class opposition practically dissolved. A no less contentious bourgeois opposition with a liberal orientation arose .

The main components of the administrative reorganization implemented in connection with the new constitution were local self-government and the separation of the executive and judiciary . The administration was streamlined and made more transparent. The officials committed to the state and the king quickly developed into a kind of class and thus into a political class that supported the state government.

When Wilhelm I came to power, the national debt was almost 25 million guilders, which was almost four times the annual income. In the first 20 years of his reign, these debts were reduced so sustainably by the finance ministers Weckherlin , Varnbuler and, above all, Herdegen that tax cuts were made possible. A particular focus of the king's economic policy was the expansion of agriculture.

In terms of foreign policy, Wilhelm pursued the goal of further streamlining the state structures in Germany and limiting them to the five kingdoms of Prussia , Saxony , Bavaria , Hanover and Württemberg as well as the Austrian Empire . He saw Prussia and Austria as European powers. The four other German kingdoms were to pursue a common policy aimed at the unification of a third German great power through a close alliance . Wilhelm sought to mediate Baden, Hohenzollern and the acquisition of Alsace. The means to this goal, which was never achieved, should be the strong family connection with Russia . To this end, his aunt Sophie Dorothee was married to the Russian heir to the throne, later Tsar Paul , in 1776 . To strengthen this bond, Wilhelm married her daughter Katharina in 1818. After Katharina had died in 1819, Wilhelm pursued the foreign policy developed together with her throughout his entire reign. So it was only logical that his son and heir to the throne Karl married the Tsar's daughter Olga on July 13, 1846 .

Gaining strength of the democratic movement and liberalism from 1830

After the successful French July Revolution of 1830, the liberals received a boost in almost all of Europe, including Württemberg. In December 1831 they won the elections for the second chamber of the Württemberg state parliament. Wilhelm I then postponed the convening of the state parliament over a year until January 15, 1833. After the state parliament was dissolved on March 22, new elections were held in April, from which the liberals under Friedrich Römer emerged victorious. Wilhelm thereupon refused to give the elected members of the civil service leave to exercise their mandate. Friedrich Römer, Ludwig Uhland and other liberal MPs therefore resigned from civil service.

In the years 1846 and 1847, after bad harvests, there were famines and increased emigration. The general mood of the population, which had been relatively “satisfied” up to that point, turned. Liberal and democratic demands were made more forceful. In January 1848, a protest meeting in Stuttgart demanded an all-German federal parliament, freedom of the press, freedom of association and assembly, the introduction of jury courts and popular arming. Wilhelm I first tried to stop the revolution in Wuerttemberg , which began in March 1848 - in the wake of the French February Revolution (which had led to the second French republic) - spreading in all German states. He put the liberal press law of January 30, 1817 back into force and tolerated a liberal government chaired by Friedrich Römers. The March Ministry , established on March 9, 1848, was the country's first parliamentary government. This policy avoided major military conflicts in the Kingdom of Württemberg during the March Revolution .

In April 1849 the government and the state parliament approved the recognition of the imperial constitution passed in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt , which provided for a nation-state conceived as a small German solution on the basis of a democratically constituted constitutional monarchy. Wilhelm felt this decision as a humiliation, but was the only king among the 29 sovereign princes of the German Confederation who approved the constitution passed by the Frankfurt National Assembly - the kings of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover and the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I rejected it from.

After the National Assembly failed with the rejection of a German imperial crown by the Prussian king, the remaining members of the parliament decided on May 30, 1849 to move the meetings to Stuttgart. From June 6, 1849, this remainder of the National Assembly, sometimes mockingly referred to as the rump parliament , initially had 154 members under Parliament President Wilhelm Loewe (1814–1886) in Stuttgart. When the rump parliament called for tax refusal and, with the support of the Reich constitution campaign, for a revolt against the governments, it was occupied by the Württemberg military on June 18, 1849 and after a demonstration by the remaining 99 members of parliament through Stuttgart, it was forcibly dissolved. The non-Württemberg deputies were expelled from the state.

In August 1849 elections to a constituent assembly took place in Württemberg , in which the Democrats gained a majority over the moderate Liberals. While the Liberals called for active and passive voting rights to be linked to income levels and wealth, the Democrats demanded universal, equal and direct suffrage for all men of age. At the end of October 1849, the king dismissed the government under Friedrich Römer, which was elected by the state assembly. The ministers were replaced by civil servants under Johannes von Schlayer . When the structure and the legal basis of the Ministry of Officials were rejected by the state assembly, Wilhelm I dissolved it. Two more state assemblies in 1850, in which the Democrats also each had a majority, were also dissolved. Nevertheless, a strong liberal and democratic opposition established itself in Württemberg even afterwards.

When King Karl took office in 1864, he complied with liberal and democratic demands. The freedom of the press and freedom of association were restored, freedom of trade and freedom of movement were guaranteed. The Jews received full citizenship rights. Existing marriage restrictions for the poor have been lifted. The conservative Chief Minister Joseph von Linden was replaced by the more liberal Karl von Varnbuler (1809-1889).

Württemberg as a federal state in the German Empire

Contrary to his father's policy, King Karl was an advocate for the creation of a German nation-state. When, after the war between Prussia and Austria against Denmark in 1864, the tension between the allies Prussia and Austria led to war in 1866 , Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden sided with Austria. The Württemberg army was defeated by Prussian troops on July 24, 1866 near Tauberbischofsheim just a few days before the armistice between Prussia and Austria. As a result, Württemberg concluded an armistice with Prussia on August 1, 1866. The war ended on August 23 with the Peace of Prague , under which Württemberg had to recognize the North German Confederation that had been founded by Prussia and pay war indemnities to Prussia.

Prior to this, Württemberg, like Bavaria and Baden, had to conclude a protective and defensive alliance , initially to be kept secret , in which territorial integrity was guaranteed, but which transferred the military command in the event of war to Prussia. After the end of the war, the national liberal German party was founded in Württemberg under the leadership of Julius Hölder , the aim of which was the accession of Württemberg to the North German Confederation. Opposite it was the democratic Württemberg People's Party , which had emerged from the liberal Progressive Party as early as 1864. The People's Party, headed by Karl Mayer , formed an alliance with conservatives and representatives of Catholicism, the aim of which was to prevent a nation-state ruled by Prussia.

In the Franco-Prussian War , the Württemberg army was subordinate to the Prussian command in accordance with the concluded alliance. During the war, Württemberg signed a November treaty with the North German Confederation on November 25, 1870 , which it joined. This accession happened with the Federal Constitution of January 1, 1871 , in the Imperial Constitution of April 16, 1871 Württemberg received four out of 58 votes in the Federal Council . Of the 397 members of the Reichstag , 17 came from Württemberg. As reservation rights , the country was granted the administration of the railroad, post office and telecommunications, the income from the beer and spirits tax and its own military administration under Prussian command.

The loss of political power of the state and the ruling house that went hand in hand with the entry into the empire was compensated for by a strong focus on the Württemberg identity. In 1876 the government was reorganized. The core of the reform was the establishment of a state ministry under Prime Minister Hermann von Mittnacht . In the years that followed, King Charles largely withdrew from operational government business and, together with Queen Olga, devoted himself to more cultural and social tasks. Although he was the head ( Summenepiskopus ) of the Württemberg Evangelical Church , he attached great importance to the development of the rights of the Catholic minority. The Kingdom of Württemberg was spared a culture war like in Prussia.

In his old age, King Charles' homosexuality did not become obvious to large sections of the population; but it almost led to a state crisis. The American Charles Woodcock , who had been employed by the king since 1883 , came under increasing criticism for his personal demands, which the government perceived as presumptuous, and for his behavior. He was also attacked by the press. The resulting conflict between the King and Prime Minister Midnight in 1888 could only be ended with the dismissal of Woodcock through the mediation of Bismarck .

King Karl died on October 6, 1891. Since he had no biological children, the reign passed to Wilhelm II , the son of his cousin Prince Friedrich von Württemberg and his sister Princess Katharina von Württemberg.

Monument by Hermann-Christian Wilhelm Zimmerle in front of the Wilhelmspalais in Stuttgart

Wilhelm, who had already retired from military service in 1882 at the age of 34, was very distant from the representational behavior of Kaiser Wilhelm II and many other rulers of the German federal states. In contrast to his predecessors, he did not enter into a marriage relationship with any of the great European dynasties. When his first wife Marie von Waldeck-Pyrmont died in 1882, he did not have her buried in the family crypt in Ludwigsburg Palace , but in the civil cemetery in Ludwigsburg. As king he did not reside in the New Palace in Stuttgart , but lived in the Wilhelmspalais , which in terms of size and furnishings corresponded to a bourgeois villa of the time. He did without the predicate of God's grace on his letterhead, which was customary for monarchs at the time, and wore civil suits instead of uniforms. As the so-called citizen king , he was very respected among the population. Politically, he aligned himself with the parliamentary majority. His administration was more like that of a president. Although he appointed the ministers in accordance with the constitution, he largely left the political work to them and the state parliament. His personal focus was on promoting culture. In this way, he made a decisive contribution to the development of cultural independence in Württemberg in the federal empire.

During the reign of Wilhelm, Württemberg was organized more democratically than the other German federal states. While in Prussia the three-class suffrage was valid, in Württemberg almost all men over 25 years of age were able to vote for the second chamber of the state parliament. The economic and social structure was more medium-sized than large industrial. Accordingly, the urbanization and the resulting impoverishment of the workers was less than in other parts of the German Empire. Nevertheless, especially in Stuttgart there was a notable and increasing housing misery among the workers. Civic social initiatives such as the construction of workers' apartments and the founding of consumer associations could not eliminate the plight of the workers; However, they contributed to the fact that the living conditions of the lower class were significantly better compared to the Ruhr area or Berlin.

The labor movement, which had also been organized in Württemberg from the middle of the 19th century, was more moderate than in Prussia. It profited from the liberal policies of Charles and Wilhelm II of Württemberg. The first workers' association was founded in Stuttgart in May 1848. The first union-like association was the Gutenberg Association of Book Printers , which was also founded in Stuttgart in 1862 . The Socialist Law , which was valid in the German Reich from 1878 to 1890 , was initially handled with rigor, but gradually weakened in Württemberg, so that well-known social democrats such as JHW Dietz , Wilhelm Blos , Georg Bassler and Karl Kautsky were able to operate more or less unhindered in Stuttgart . After the repeal of the Socialist Law in 1890, there was also a wave of social democratic associations in Württemberg. Stuttgart became the center of trade union efforts. The German Metalworkers Association , founded in 1891, was also based in Stuttgart. The aim of the union work was initially to reduce working hours. An initial success was the introduction of the nine-hour day at Bosch in 1894. The increasingly independent cultural identity of the labor movement became clearly visible with the establishment of the Stuttgart forest homes.

The state elections of 1895 resulted in a strong majority for the democratic parliamentary groups. The supremacy of the German party was broken. The new majority was formed by the democratic Württemberg People's Party and the Catholic Center founded before the election . The SPD came to the state parliament with two seats for the first time. In the following years parliamentarianism was expanded. A modern spectrum of parties developed from conservatives, national liberals, the People's Party, the Center and the SPD. The leading party politicians in the late phase of the Württemberg monarchy were Heinrich von Kraut and Theodor Körner for the conservatives , Friedrich Payer and Conrad Haußmann for the People's Party , Adolf Gröber for the Center and Wilhelm Keil for the SPD . At the local level, social democrats participated in politics early on and often found political consensus with bourgeois parties.

In the Landtag, on the other hand, the Social Democratic parliamentary group only approved the Württemberg state budget once, in 1907. This was in return for the International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart in August of the same year , the first of its kind on German soil. The Württemberg authorities supported the organizers of the congress, much to the displeasure of the Kaiser and the Reich government in Berlin. Around 900 delegates, including the women's rights activist Clara Zetkin , who lives in Stuttgart, and the Russian revolutionary Lenin , received a hospitable reception and were even allowed to use the first class waiting room at Stuttgart Central Station . The congress was able to carry out its program unhindered in the Stuttgart Liederhalle and hold a major event with public speeches on the Cannstatter Wasen , in which more than 30,000 people took part.

The results of the last two state elections for the Second Chamber in the Kingdom of Württemberg are summarized in the table below. After the constitutional reform of 1906, the representatives represented there were elected by the people alone:

| Election year |

Social demo- crats |

People's Party |

German party |

center | Conservative Party and Association of Farmers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 | 22.6% 15 seats |

23.6% 24 seats |

10.9% 13 seats |

26.7% 25 seats |

16.2% 15 seats |

| 1912 | 26.0% 17 seats |

19.5% 19 seats |

12.1% 10 seats |

26.8% 26 seats |

15.6% 20 seats |

Since King Wilhelm II had no sons, it was foreseeable that the succession to the throne would pass from the Protestant line of the House of Württemberg with Albrecht von Württemberg to the Catholic sidelines. This perspective alarmed the leading Protestant liberal bourgeoisie in Württemberg, and there were many discussions about the future relationship between church and state. This led to the somewhat paradoxical situation that a Protestant dynasty ruled in the predominantly Catholic neighboring state of Baden , while in the predominantly Protestant Württemberg a Catholic dynasty was to take over the succession.

First World War and End of the Kingdom

On August 1, 1914, the Kingdom of Württemberg, like the other federal states, agreed in the Bundesrat to the authorization of Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to declare war on France and Russia. King Wilhelm then signed the war appeal to his people on August 2nd, although he did not share the general enthusiasm of the population for war. By 1918 there were 508,482 Württemberg combatants, which was more than a fifth of the population. 71,641 Württemberg soldiers fell victim to the war .

In the course of the November Revolution, the Württemberg government resigned on November 6, 1918 to make way for a parliamentary government. When State Secretary Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the Republic from a window in the Reichstag in Berlin on November 9, rallies were also held in Stuttgart. In the morning demonstrators occupied the Wilhelmspalais. In the afternoon a provisional government from the two socialist parties SPD and USPD was formed under Wilhelm Blos in the state parliament . King Wilhelm then left Stuttgart on the evening of November 9th and moved to the Bebenhausen hunting lodge . On November 30, he renounced his throne and assumed the title of Duke of Württemberg. As a people's state, Württemberg became part of the German Empire during the Weimar Republic .

State building and administration

Constitution

The constitution of the Kingdom of Württemberg was enacted by King Wilhelm I on September 25, 1819. It comprised ten chapters with a total of 205 paragraphs. In Chapter I, Württemberg was defined as a state and part of the German Confederation . Chapter II defined the king as head of state and regulated the succession to the throne . The king was the sole holder of state authority , which he could only exercise within the framework of the constitution (§ 4). Among other things, he appointed and dismissed the members of the government represented on the Privy Council (§ 57). He represented the state externally (Section 85), had the right of initiative for legislation (Section 172), issued the ordinances (Section 89) and was in charge of the jurisdiction (Section 92). Chapter III regulated civil rights and duties. The state was obliged to secure civil rights (Section 24), which included, among other things, freedom of the person, freedom of movement , freedom of trade (Section 29) and property (Section 30). The freedom of the press (§ 28) was subject to a legal reservation . Chapter IV regulated the organization and tasks of the Secret Council and the administration. With the formation of a government legitimized by parliament in 1848 under Friedrich Römer , the Secret Council lost its previous importance. From 1876 the government was transferred to the newly established State Ministry of the Midnight Government . The Secret Council continued to exist until 1911 as a state authority advising the king. The constitution provided for the ministries of justice, foreign affairs, home affairs, warfare and finance (section 56). The respective ministers belonged to the Secret Council and later to the State Ministry. In 1848 the Ministry of Churches and Schools was spun off from the Ministry of the Interior. All members of the Privy Council were elected and dismissed by the King (Section 57). Chapter V regulates the rights of the municipalities and regional authorities. The principle of local self-government applied . Chapter VI defined the relationship of the three Christian churches in the kingdom to the state. Chapter VII dealt with the exercise of state authority . The legislation was bound to the approval of the estates (§ 88); all laws had to conform to the constitution (§ 91). The jurisdiction was independent (§ 93). Chapter VIII regulated finance. Chapter IX laid down the composition and organization of the estates, the main task of which was to participate in the legislative process by approving the draft bills submitted by the government (Section 124). The estates were organized as a bicameral system . Members of the first chamber, referred to as the Chamber of Class Lords , were the princes of the royal house, the representatives of the nobility and the former civil society in Altwuerttemberg, as well as members appointed by the king hereditary or for life (§ 129). The second chamber, known as the Chamber of Deputies , consisted of members by virtue of office, of 13 elected representatives of the knightly nobility and of representatives of the cities and higher offices elected by the people (§ 133). The electoral term was six years (Section 157). The elected representatives were not bound by instructions (§ 155). Chapter X regulated the organization and tasks of the State Court.

After the German Revolution of 1848, a state constituent assembly was set up and, after its election, dissolved again by the king. Significant changes to the constitution and its application were made by the establishment of the Reich in 1871 and by the constitutional laws of 1906 and 1911. In 1906, the bicameral system was redefined, so that only members elected by the people were represented in the second chamber. When the constitution was amended in 1911, the Secret Council was finally abolished.

Administrative division

The Kingdom of Württemberg was divided into twelve regional bailiffs in 1810, which were divided into 64 higher offices. In 1818 the twelve provincial bailiffs were replaced by four administrative districts called Kreise , which were only dissolved on April 1, 1924. The Donaukreis had its seat in Ulm , the Neckarkreis in Ludwigsburg , the Jagstkreis in Ellwangen and the Schwarzwaldkreis in Reutlingen .

Broad Local Government

According to the constitution of 1819, the principle of local self-government applied in the Württemberg municipalities , the practical design of which was laid down in the administrative edict of March 1, 1822. The mayor, who was referred to as Stadtschultheiß in the cities and as mayor in the villages , was elected by the citizens entitled to vote from three applicants for life. He represented the community and chaired the local council. The council was depending on the size of the community from seven to 21 members, who were also elected for life. Various committees were set up for day-to-day business, the most important of which was the church convention, which was expanded to include the pastor and the foundation curator . The second body in the community was the citizens' committee, whose members were temporarily elected. Resolutions of the municipal council were dependent on the hearing and approval of the citizens' committee. Community officials were the council clerk, whose office was often carried out by the mayor in small communities, and the community caretaker for the treasury and accounting. The parish clerk was not allowed to be council clerk at the same time. If the mayor or the parish clerk could not provide the necessary training for their tasks, the municipalities had to employ an administrative actuary who was appointed by the respective senior offices at the municipality's expense. The law of July 6, 1849 abolished the election of municipal councilors for life and replaced it with a six-year term. The election of the mayor for life was only abolished by the municipal code of July 28, 1906.

The main tasks of the community were the welfare, the school system and the affairs of the local police. The municipalities did not have jurisdiction. The church conventions could, however, impose smaller fines and arrest sentences in matters of morality. In his function as justice of the peace , the mayor was unable to pass judgments, but as an arbitrator in civil law disputes he could bring about an agreement or, in private litigation, an out-of-court settlement known as an attempted atonement . According to the Police Criminal Code of October 2, 1839, the municipal council and the mayor were given the right to punish defined criminal matters.

The next higher regional authority after the municipality was the Oberamt . In addition to their self-defined tasks within the framework of local self-government, the higher offices also had to perform state tasks assigned by the state. In addition, they took on a large number of voluntary legal obligations of the municipalities, such as the maintenance of communal roads. Organs of the Oberamt were the Oberamtmann and the official assembly, in which all municipalities of the Oberamt were represented. It met once or twice a year. The day-to-day business was handled by the local assembly committee, which appointed an actuary as chairman and at the same time deputy to the senior bailiff. A senior clerk was appointed as the treasurer , who had a seat and an advisory vote in the official assembly.

Since the administrative reform after Wilhelm I came to power, the administration has been separated from the judiciary. For this purpose, a higher official court with an upper official judge as chairman was set up in each higher office. Area notaries and their assisting notaries were subordinate to the Higher Regional Court to carry out the formal legal transactions in the Higher Office and the associated municipalities .

Basics of the state administration

The executive was delegated to the individual ministries under the direction of the king. There were the five classic ministries of justice, foreign affairs, the interior, warfare and finance, which were supplemented from 1848 by a ministry of education, initially called the ministry of church and school. The state administration was carried out partly decentrally in the four administrative districts known as districts and partly centrally by central authorities subordinate to the ministries.

Examples of central authorities in the business areas of the individual ministries included the State Stud Commission ( see also : Main and State Stud Marbach ) and General Directorate of the Württemberg Post Offices ( see also : Württemberg (Postal History and Stamps) ) in the Ministry of the Interior, the House and State Archives ( see also : Main State Archives Stuttgart ) in the Ministry for Foreign Affairs as well as the Chamber of Accounts and the State Treasury in the Ministry of Finance. Each central authority was headed by a director.

At the time of their establishment in 1818, the counties had about as many inhabitants as a French department . In each county there was a government, a finance chamber and a court of justice. The district governments were among other things higher authority in the state police administration and the state economy. Up to 1848 her tasks also included the promotion of agriculture, trade and commerce and up to 1872 road construction. They were also the supervisory authority for the higher offices in their area.

In addition to the local police, the state police were also set up from 1807, which were named Landjägerkorps from 1823 . Its task was to support the state and municipal authorities in their work to maintain security and in the prosecution of criminal acts. The Landjäger Corps was organized militarily. The chief was the corps commander , who presided over the district commanders in the four districts. In 1823 it comprised 441 men who were distributed among the senior offices and commanded by a station commander in each senior office .

Basic features of the army

Wuerttemberg already had its own army before the time it was founded as a kingdom in 1806 until the end of the monarchy in the November Revolution 1918 and for a short time beyond that, but this was integrated into the command structures of the Prussian army when the empire was founded in 1871 and thus from 1871 to 1918 was part of the German Army . While the neighboring kingdom of Bavaria was allowed to maintain its full military autonomy in times of peace beyond 1871, Württemberg was unable to enforce this degree of autonomy after the unification of the empire. Similar to the Kingdom of Saxony, Württemberg retained limited military sovereignty. The Württemberg War Ministry , founded in 1806 , continued to exist until 1919.

When he took office as Duke of Württemberg, Frederick II took over a standing army of 4,264 men and 465 horses. For France's third coalition war against Austria and Russia in 1805, Württemberg had to provide a contingent of 6,300 men with 800 horses and 16 guns, but this did not come into contact with the enemy.

When the royal dignity was accepted in 1806, the Württemberg army already comprised 9,928 men and 1,510 horses. Of these, 8,109 men belonged to the infantry , 1,353 men with 1,270 horses to the cavalry and 466 men with 240 horses to the artillery . Membership in the Rheinbund made it necessary for Württemberg to raise a contingent of 12,000 men. In order for this to be possible, King Friedrich I issued a military conscription law on August 6, 1806 , which was based in principle on the idea of general conscription .

In the fourth coalition war between France and Prussia, the Württemberg troops were deployed in 1806 with a strength of 12,000 infantry and 1,500 horses, mainly for the siege of the Prussian fortresses of Glogau, Breslau, Schweidnitz, Neisse and Kolberg . In the Fifth Coalition War against Austria in 1809, 13,000 men, 2,600 horses and 22 artillery pieces from Württemberg took part in the conflict. They were used in the battle of Eggmühl . Further battles along the Danube followed. In 1809 Württemberg had a total of 28,600 men under arms, plus 3,844 horses and 36 artillery pieces.

For the Russian campaign in 1812, Württemberg contributed 15,800 men, 3,400 horses and 30 guns to the Grande Armée . Of these, 2,400 men got through to Moscow, but the contingent perished miserably on the march back after the onset of winter due to frostbite, illness and the pursuing Russian army, except for a few hundred men. After this military catastrophe, Württemberg had to march again 11,600 men and 2,700 horses for Napoleon in 1813 against the coalition of Russia, Prussia and Austria. The troops again suffered heavy losses in the battles near Bautzen, Lauban, Groß-Görschen and Dennewitz .

After Württemberg had renounced its alliance with Napoleon at the end of 1813 and switched to the camp of the Allied Powers against France, 24,000 men, 2,900 horses and 24 guns of the Württemberg army were called up to advance to Paris in 1814. At the end of the coalition wars in 1815, the army comprised a total of 22,734 men with 2,967 horses. Of these, 16,485 men with 48 horses belonged to the infantry, 3,399 men with 2,547 horses to the cavalry and 2,138 men with 309 horses to the artillery. There were also 456 men in the gendarmerie with 63 horses, 190 men in the Honorary Invalid Corps and 66 officers from the various staffs. Calculated in military units, there were 24 battalions of foot troops, 24 squadrons of cavalry and 13 gun and ouvrier companies.

In 1815, the greatest war period for the Kingdom of Württemberg came to an end before the outbreak of the First World War. The wars of coalition and liberation resulted in the loss of a total of 269 officers and 26,623 soldiers for the Württemberg army. About 75% of the losses were accounted for in the years 1812 and 1813. The regular military budget between 1810 and 1816 amounted to 3.8 million guilders, about 33% of government spending. The economic losses of the war years from 1792 to 1813 were put at around 65 million guilders without adding the regular military budget.

When King Wilhelm I ascended the throne in 1816, he reorganized the army in 1817, which mainly resulted in a reduction in the number of troops. At the time of the German Confederation, the Württemberg army consisted of eight regiments of infantry , each with two battalions of four companies . Two of these eight regiments were divided into four brigades . Two brigades each belonged to the two infantry divisions. The infantry now had a nominal strength of 11,352 men. The cavalry with 2,851 men consisted of a division with two brigades of two regiments each. Each of these four cavalry regiments consisted of four squadrons. There was also a squadron of life guards on horseback with 163 men. In the artillery brigade there was one battalion on horseback with three batteries and one battalion on foot with four batteries. The artillery consisted of 1113 men. At the head of the army was the War Ministry, to which a so-called corps command had been subordinate since 1849 . There was also the general staff with 16 officers , the general quartermaster staff with a pioneer company and two garrison companies. A composition consisting of 40 man military police -Schwadron was responsible for the internal security of the troops. There was general conscription with a period of service of six years, but the recruits could take leave of absence after basic training. Therefore, at the beginning of the government of King Wilhelm I, there were actually only about 6,500 men in permanent service.

In the event of a defense against the German Confederation, Württemberg had to provide a total of 13,955 men. The infantry accounted for 10,816 men, the cavalry 1,994 men and the artillery and engineers 1,145 men. This contingent formed the 1st Division of the VIII Federal Army Corps . The Federal Fortress Ulm was a strong fortress of the German Confederation on the soil of the Kingdom of Württemberg .

During the revolutionary unrest of 1848, the 7th Infantry Regiment from Ludwigsburg, which secured the endangered north-western border with Taubergrund in Baden, and the 8th Infantry Regiment from Heilbronn to suppress unrest in Hohenlohe. Further units strengthened the northern border of the German Confederation against Denmark in 1848/49 and, with troops from Prussia, Mecklenburg and Hesse, took part in the so-called Neckar Corps to suppress the revolution in Baden .

The next war deployment took place in the German war against Prussia. As part of the VIII Federal Army Corps, Württemberg units were involved in the fighting at Tauberbischofsheim . The defeat paved the way for an army reform based on the Prussian model in 1867, which was carried out by the later Minister of War, Albert von Suckow . During the Franco-Prussian War , the Württemberg field division comprised a total of 15 battalions, 10 squadrons, 54 artillery pieces and two pioneer companies that belonged to the Third Army . In the Battle of Wörth 356 soldiers died from Württemberg and in the Battle of Champigny there were 1,970 losses in dead and wounded. During the entire Franco-German War, 650 Württemberg soldiers were killed, including 37 officers, and around 2,000 soldiers were wounded, including 110 officers.

Since 1871, the Württemberg army was under the general command of the XIII. Army corps based in Stuttgart. The 1st Royal Wuerttemberg Division became the 26th Division with headquarters in Stuttgart and the 2nd Royal Wuerttemberg Division became the 27th Division with its headquarters in Ulm.

National symbols

The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Württemberg consisted of a round oval shield with a golden oak wreath, which was divided into two halves. In the left half the three lying deer poles of the House of Württemberg were depicted, on the right the three Staufer lions of the former Duchy of Swabia . Shield holders were a black lion and a gold deer. The sign holders were on a red and black ribbon with the inscription Fearless und trew . Above the shield sat a helmet and the royal crown.

The flag of the kingdom was black above and red below. These national colors were introduced by decree of King Wilhelm I on December 26, 1816. They replaced the colors black, red and gold, which were only introduced on December 14, 1809. This change was not least due to the fact that tricolors had become popular in Europe during the domination of France . After the Wars of Liberation , the associated revolutionary symbolism was frowned upon; however, red and yellow were now the state colors of the new neighbor Baden, and black and yellow were the Habsburg colors, so that the only two-color combination that remained was black and red.

currency

Until 1875 the currency of the Kingdom of Württemberg was the guilder . One guilder consisted of 60 cruisers . After the establishment of the German Empire, the German Coin Act of July 9, 1873 and the imperial ordinance of September 22, 1875 introduced the gold mark with effect from January 1, 1876. The guilder could be used in parallel for another five years. The exchange rate for a Württemberg guilder was 1.71 marks for one guilder.

Economic development

The Kingdom of Württemberg was essentially an agricultural state for almost its entire existence. This only changed noticeably in the nineties of the 19th century, when the beginning of the industrial age began to emerge in Württemberg as well. Many companies that are still well-known today were founded in the middle and late phases of the monarchy.

The agrarian state and its crises

The area of the old Duchy of Württemberg has always had an economic location disadvantage due to two main factors: On the one hand, there are hardly any significant mineral resources in this area that could be economically mined in historical times. On the other hand, the geographical and topographical conditions (hilly landscapes) for the formation of a functioning transport network, which could have resulted in extensive trade, were extremely bad. The center of Altwuerttemberg had no navigable waterways, and even the kingdom was initially only easily accessible by water at its edges in Ulm on the Danube, the lower Neckar to Heilbronn and Lake Constance. So it came about that the former Swabian and Alemannic centers were all outside the Duchy of Württemberg, such as Augsburg, Ulm, Ravensburg, Constance, Zurich, Basel, Freiburg and Strasbourg.

The situation at the beginning of the 19th century can hardly be summarized more appropriately than with an excerpt from the ballad Justinus Kerner Preisend, also known as the Württembergerlied , with many beautiful speeches from 1818:

- Eberhard, the one with the beard ,

- Württemberg's beloved lord,

- Said: "My country has small cities,

- Does not carry mountains as heavy as silver ”.

In 1817 there were a total of 134 cities in Württemberg with around 1,380,000 inhabitants. Of these, only five cities had more than 6,000 inhabitants, namely Stuttgart with 26,306 inhabitants, Ulm with 11,417 inhabitants, Reutlingen with around 9,000 inhabitants, Heilbronn with 6,830 inhabitants and Tübingen with 6,630 inhabitants.

The Kingdom of Württemberg was made up of the areas of Old Württemberg with a predominantly Protestant population (around one million Protestants) with a penchant for pietism and the areas of New Württemberg that were heavily influenced by Catholicism (around 400,000 Catholics). In Altwuerttemberg there was the practice of real division in inheritance law. This led to the fact that the farms had ever smaller plots available for cultivation. The rural population had to make a living through an additional profession, a craft. So a skill arose early on, born of need and want, which is still proverbial today for the Swabians , as the people of Württemberg like to call themselves. In the Neuwuerttemberg areas this was a little different due to the inheritance law that was more widespread there . A farmer could often be a relatively wealthy man there. At the beginning of the 19th century, more than two thirds of the population were still active in agriculture.

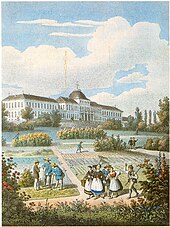

Overall, the economic situation in Württemberg at the beginning of the 19th century was characterized by want and hardship for large sections of the population, due to the long-lasting state of war from 1792 to 1815, which was only interrupted by short phases of peace or an armistice. Although most of the battles of this time did not take place on the territory of the kingdom, the constant movements of troops combined with billeting, confiscation of food and fodder, looting and pillage were a constant oppression at this time. In addition, from 1811 there were bad harvests, which in 1816 led to catastrophic supply shortages for the poorer population. In the terrible need, so-called hunger rolls were baked, which were reasonably affordable. These hunger rolls were much smaller than usual. The flour was stretched with sawdust or other inadequate additives. The good harvest of 1817 brought the long-awaited redemption from the worst hardship. Happy Thanksgiving was celebrated across the country. In the face of the hardship that had been overcome, King Wilhelm reacted by vigorously promoting agriculture in order to be able to better deal with similar emergencies in the future. From 1818 this led to the holding of an annual agricultural exhibition, the forerunner of the Cannstatter Volksfest , and the establishment of the agricultural institute in Hohenheim .

While agricultural prices rose sharply in the famine year of 1816 due to the shortage and the usury at the expense of the needy was a problem that had to be combated on all sides, they fell noticeably since 1817. The fall in prices led to a real agricultural crisis until 1826 and, as a result, to the impoverishment of the rural population. As early as 1844, a new economic crisis with inflation and unemployment announced itself , which culminated in another famine year in 1847 with hunger riots. The agricultural crisis lasted until around 1855.

The kingdom remained significantly from the effects of basically throughout the reign of King William I more or less pauperism marked. Mainly for economic and social reasons, at least 400,000 people from Württemberg emigrated to Eastern Europe or America from 1815 to the establishment of the German Empire in 1871, which corresponds to an annual average of 4,200 people. From 1800 to 1804 alone around 17,500 people emigrated, mainly to Eastern Europe, before King Frederick's ban , which was in effect from 1807 to 1815, prohibited emigration. After the ban was lifted, the number of emigrants skyrocketed in 1816 and 1817. It was around 20,000 people per year. The reasons for emigrating were not only poverty and unemployment, but also the heavy tax burden and the widespread arbitrariness of the authorities. The miserable writing system in particular led to the decision to turn their backs on their homeland, because under these state repression there seemed to be no prospect of development for many in the future.

Since early industrialization of Württemberg was ruled out due to the lack of coal and the production of heavy goods also failed due to the poor transport options, the craft was mainly occupied with the production of textiles and other easily transported goods (precision mechanics, instrument making for science and art as well as musical instruments) if it was about export. However, many of the products of the handicraft were only intended for the domestic market, especially in the construction and furniture trade. The craft remained organized in guilds until 1862 . The factories and individual factories obtained their energy mainly from hydropower, so that the nucleus of the industry in Württemberg lay along the Neckar, as in Esslingen and Cannstatt. It was not until 1895 that steam power surpassed water power in Württemberg.

Medium-sized industrialization in Württemberg

The economist Friedrich List , who was underestimated in his time , had pre-formulated many ideas that gradually helped Württemberg to get out of his economic misery. This included the founding of the South German Customs Union in 1828 and the German Customs Union in 1834, in the creation of which King Wilhelm I was very interested, as well as the constant improvement of land and waterways. The challenges this brought with it can be recalled with reference to the Geislinger Steige on the Albaufstieg and the Neue Weinsteige in Stuttgart. The foundation stone for expanding the Neckar as a waterway was laid between 1819 and 1821 by the Stuttgart hydraulic engineering director Karl August Friedrich von Duttenhofer with the construction of the Wilhelm Canal near Heilbronn. In 1841 the Neckar steamship service reached Heilbronn, but further upstream the economic use of paddle steamers failed due to the unfavorable water conditions of the Neckar. Steamships have been sailing on Lake Constance since 1824.

Another idea propagated by Friedrich List was the expansion of rail traffic in Germany. In 1843 a state railway was founded in Württemberg. This was a big and far-sighted investment in the future of the country, because at that time the poor agricultural country could not actually afford its own railroad through the topographically difficult terrain. The decision to found the Royal Württemberg State Railways was at the same time the decision to go into debt management. The national debt rose from the equivalent of 36 million marks in 1845 to 653 million marks in 1913, with 633 million being accounted for by the state railway. Nevertheless, the history of the railway in Württemberg was a success story that paid off for the state in the long term. It promoted the growing together of the regions and increased communication, especially because telegraph lines were also built along the rails. The importance of rail transport for Württemberg is also expressed in the folksong Auf de Schwäbsche Eisebahne . The history of the Esslingen machine works, founded in 1846, is closely related to the railway .

After the revolutionary years of 1848/49 it became politically more depressing under the Linden government , but economic development was now increasingly in better waters, not least thanks to the better roads and railways, which also made it easier to trade in agricultural products. About 44.9 percent of the land used for economic purposes was distributed over arable land and gardens, 1.1 percent over vineyards, 17.9 percent over meadows and pastures and 30.8 percent over forests. Around 90 percent of the 360,000 families in Württemberg owned property in 1857. Only about a third of them were full-time farmers. Of these, only a very small part, mainly in southern Upper Swabia, owned more than 30 acres of land. This forced a large part of the population to earn additional income in other branches of the economy, particularly in the textile, wood and construction industries. Working in agriculture and in the commercial sector at the same time was typical for Württemberg. The main agricultural products were oats, spelled, rye, wheat, barley, hops, grapes, peas, beans, corn, fruit (mainly cherries and apples), tobacco, and horticultural and dairy products. To this end, a considerable number of cattle, sheep and pigs were built up and not little attention was paid to horse breeding .

In association with Ferdinand von Steinbeis, the government was very committed to promoting agriculture, trade, commerce and industry. In 1861 the Stuttgart Stock Exchange was founded , although there were still hardly any large companies in the country. Often the financing of larger companies was still a problem because there was little developed banking and credit in the country. An exception was the Königlich Württembergische Hofbank in Stuttgart, which dates back to the founding of Madame Kaulla's family at the beginning of the 19th century. The court bank not only handled the king's financial affairs, but also granted start-up loans. Later, important things in this area were also accomplished by Kilian von Steiner . The extent to which small and medium-sized enterprises and crafts still dominated Württemberg in 1861 can be seen in the number of craft businesses: for every 1,000 Württemberg residents there were around 85 craft businesses, an unusually high density compared to the rest of Germany. The high number of skilled craftsmen was only an advantage for the beginning industrialization. With the loss of the guilds in 1862, commercial advanced training schools were founded. The member of the state parliament, Karl Wilhelm Weigle, was particularly concerned with promoting the textile industry. In 1854 the Reutlingen weaving school was founded. In addition to the textile industry, commercial products were mainly iron and steel goods as well as gold and silver goods, which required special craftsmanship in production. In Heilbronn and Ravensburg , the established production of paper . In this context, the first German to paper machine of Johann Jakob Widmann be mentioned. The Kingdom of Württemberg mainly exported cattle, grain, wood, salt from the Friedrichshall salt works in Jagstfeld , oil, leather, cotton and linen fabrics, beer, wine and spirits. Reference should be made here to the Kessler sparkling wine from Esslingen, where Georg Christian Kessler had been producing the oldest sparkling wine in Germany since 1823 . But musical instruments (pianos) and high-quality precision engineering products were also produced. The trade was concentrated in the larger cities such as Stuttgart , Ulm , Heilbronn and Friedrichshafen . Stuttgart was also known as the Leipzig of southern Germany because of its pronounced publishing and book trade, especially Cotta'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung .

After the establishment of the German Empire , the guilder was replaced as currency by the mark ; the metric system was introduced as a new system of measurement . The steady economic growth for around 20 years entered a hot boom phase with the founding period , which was seriously dampened in the Vienna stock market crash in 1873 . In economic terms, the Kingdom of Württemberg was unable to make a major contribution to the dynamism of the German Empire, which existed from 1871 to 1918, which would soon develop again. The proportion of the Württemberg population in the Reich population fell from 4.4 percent in 1871 to 4.1 percent in 1891 to 3.7 percent in the war year 1916. In 1913 the average income per inhabitant in Württemberg was 1,020 marks, which was only about 88 percent of the average in the empire. The still very rural and small town character of the country in the run-up to the First World War can also be seen from the following figures. In 1910, only one in five Württemberg residents lived in a city with more than 20,000 inhabitants, whereas in the German Empire it was already one in three. Only one in nine people from Württemberg lived in Stuttgart, the only big city in Württemberg. In contrast, one in five of the population of the Reich lived in a large city. These figures also show that the factories in Württemberg were spread all over the country and were not concentrated in a few metropolitan areas. The many medium-sized businesses allowed their employees to continue to cultivate their own land as part-time farmers. The above-described lower proletarianization of the working class and the moderate orientation of social democracy had their cause here too. In 1875 almost 288,000 people worked in commercial enterprises. 71,000 companies already employed more than five assistants. The vast majority of employees were employed in the textile and clothing industry. 22,300 workers were employed in the metal industry, slightly more in construction, wood processing and trade. Large farms were rare. In 1875 there were only 45 factories with more than 200 employees. In 1882 around half of the population was still employed in agriculture. In 1895 the proportion of the rural population was 45.5 percent. The trend towards fewer and fewer people working exclusively in the primary sector of the economy was supported by the increasing mechanization of agriculture, for which the Swabian engineer Max Eyth was the inspiration.

For the industrialization that began on a large scale in the nineties of the 19th century, big names such as the automobile pioneer Gottlieb Daimler , who came from the Schorndorf guild tradition and who founded the Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft in Cannstatt , and his companion Wilhelm Maybach can be mentioned. No less well known is the electrical engineer Robert Bosch , the founder of Robert Bosch GmbH . Other well-known names from very different branches of the time are for example:

- the Junghans company in Schramberg (clocks and defense technology),

- the Heller brothers in Nürtingen (machine tools),

- the Württembergische Metallwarenfabrik (WMF) in Geislingen an der Steige (household and hotel goods),

- the company Magirus in Ulm (fire fighting technology),

- the Zeppelin airship in Friedrichshafen,

- the Märklin company in Göppingen (toys),

- the Steiff company in Giengen an der Brenz (soft toys),

- the Bleyle company in Stuttgart (knitwear),

- the company Triumph in Heubach (clothing) and

- the Salamander company in Kornwestheim (shoes)

With the boom in industry, the country was also electrified. During the reign of the last king of Württemberg, over 240 power plants were built. In 1916, 1800 of the 1899 municipalities in Württemberg could be supplied with electricity. With the First World War accompanying war economy interrupted the early success of many companies and meant for the near much of the population hardship, deprivation and death relatives, often of the father and breadwinner. During the war, women moved into the factories for the first time in large numbers as urgently needed replacement workers.

Population development

At the end of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1806, around 650,000 inhabitants lived on the territory of the Duchy of Württemberg on an area of 9,500 square kilometers. At the end of the territorial upheaval in 1813, both the area with 19,508 square kilometers and the population with around 1,380,000 inhabitants had more than doubled. By the time the German Empire was founded , between 400,000 and 430,000 people emigrated from the Kingdom of Württemberg. The migration found mainly in the crisis years of 1816 culminating / 17, 1846/47 and 1852-1854. The densely populated areas in the Neckar and Black Forest districts were particularly affected . The main motive for emigrating was economic hardship; most of the emigrants came from agriculture and handicrafts. The target countries were in Eastern Europe and especially the United States of America . Despite these losses through emigration and child mortality of over 30 percent, the population rose by around 360,000 between 1812 and 1849. This development was abruptly interrupted in the year of the crisis in 1846. The number of marriages and the birth rate fell significantly, while the number of emigrants skyrocketed. Until 1867, the population grew by just under 34,000 people.

Even after the establishment of the empire, the population initially grew only moderately. The number of emigrants remained high. Despite the decline in the birth rate, population growth accelerated significantly from the turn of the century. This development was also triggered by advances in medicine and the associated higher life expectancy , which rose from 28 years in 1871 to around 45 years in 1910. In the 25 years between 1875 and 1900, the population grew by almost 288,000, almost as fast as in the only ten years between 1900 and 1910 with around 268,000. From 1890, as a result of the growing industry, an accelerated rural-urban migration began. While in 1890 around two thirds of Württemberg's citizens lived in the countryside, in 1910 over 43 percent lived in cities. If you add the urban communities with over 2,000 inhabitants, it was even more than 50 percent. The state capital Stuttgart was able to more than triple its population in its former district boundaries from 91,623 in 1871 through incorporations to 286,218 in 1910. Industrialization led to an increase in commuters between home and work. Between 1900 and 1910 their number grew from 54,322 to 88,155.

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1812 | 1,379,501 |

| 1849 | 1,744,017 |

| 1867 | 1,778,396 |

| 1875 | 1,881,505 |

| 1900 | 2,169,480 |

| 1910 | 2,437,574 |

Culture

In order to gain an understanding of the culture of the Kingdom of Württemberg, knowledge of the prehistory of the individual territories is essential. The most important part is the Duchy of Württemberg, which in the kingdom was called the heartland of Old Württemberg . In addition to Altwuerttemberg, there was also the areas of Neuwuerttemberg as a quite heterogeneous composition, for example from Hohenlohern, Ellwangern, Front Austrians, Imperial Cities and Upper Swabia. At the national festival for the 25th anniversary of King Wilhelm I's reign on September 28, 1841, it became apparent how colorful and diverse the population of the kingdom was. A pageant of the people of Württemberg was organized through Stuttgart, which consisted of 10,390 participants, including 640 riders and 23 carriages with horse and cattle teams from all parts of the kingdom. Around 200,000 spectators, i.e. every ninth Württemberg resident, had come to the capital Stuttgart with its 40,000 inhabitants at the time. This festival was unique in the history of the kingdom and promoted the idea of togetherness. The anniversary column by Johann Michael Knapp in front of the New Palace in Stuttgart, which was only completed in 1863, is still a reminder of this event today.

Dialects

The Kingdom of Württemberg was not only inhabited by Swabians , although the Swabian element was very dominant. In addition to Swabian dialects about south of a line from Bad Wildbad via Ludwigsburg and Ellwangen , the Lower Franconian dialect group of the South Rhine-Franconian dialect group and the Hohenlohe dialect group of the East Franconian group were spoken in the north of the kingdom . In the very south of the kingdom, on Lake Constance, Lower Alemannic was in use. In the west, south of Wildbad, there was a dialect border between Swabian and Upper Rhine- Manish, which, with a few exceptions, corresponded to the state border of Württemberg and Baden . This very simplified geographical description of the dialect distribution for Württemberg is still valid today in its basic features, although the dialects in the 19th century are much more pronounced, at the same time more primitive and in their nuances for locals due to the much lower mobility and the lack of radio and other sound carriers of the respective region were mostly distinguishable from place to place.

Pietism and Protestant regional church

The demonstration of unity in diversity on the anniversary of King Wilhelm I's reign in 1841 must not hide the fact that the essential element of the kingdom was the Protestant population of Old Württemberg, which was relatively homogeneous in its formative mentality compared to the new parts of the country, which was regional Swabian dialect sounding a little different and with its simple, dark clothing differentiated from the Catholic population in Württemberg, which for a long time still felt strange. These peculiarities of the population of Old Württemberg are due to the Reformation and Pietism , which was developed in a line of tradition from Johannes Brenz and Matthäus Alber via Johann Valentin Andreae to Johann Albrecht Bengel in its special Württemberg form .

Outward signs of Pietism were the principles of order, conscientiousness and diligence that were invoked as virtues . The characteristics that were said to be of this part of the Württemberg population, such as thrift, perseverance, tenacity and hard work, were often accompanied by the almost proverbial harshness and reserve that was customary in the country. Too great politeness aroused suspicion. Exuberance, ostentation and pomp were rejected, so that the fine arts in Altwuerttemberg have always had a difficult time.

In Altwuerttemberg the word of the Bible and the respectability , that class of influential townspeople and evangelical clergy that have developed since the Treaty of Tübingen , were valid . Altwuerttemberg was a duchy of pious citizens, less of the nobility and peasants. This tradition continued in the Kingdom of Württemberg. However, at the beginning of the 19th century, after the introduction of a new liturgy , the particularly strict Pietism came into conflict with the Evangelical Church and its officials, which could lead to emigration for some believers, but also to the establishment of communities that were supported by the Church were independent, such as Korntal and Wilhelmsdorf . An important representative of Pietism at the time of the Kingdom of Württemberg was the preacher Sixt Carl von Kapff , a declared enemy of the Enlightenment, rationalism and Hegel's philosophy of dialectics as a variation of German idealism .

In this pietistic climate, educators like Johann Gottfried Pahl had to resort to publications under pseudonyms. The book Leben Jesu, published in 1835, caused great outrage in Pietistic Württemberg - viewed critically by David Friedrich Strauss . The inaugural lecture given by Friedrich Theodor Vischer at the University of Tübingen met with similar rejection because of his pantheistic philosophy and direct attacks on pietism. However, the Evangelical Regional Church later succeeded in balancing the different points of view of the pietistic and progressive forces.

The Pietists encouraged the formation of numerous charitable associations and contributed to the spread of religious literature, which found its expression in the establishment of the Privileged Württemberg Bible Institute by Carl Friedrich Adolph Steinkopf in 1812 and the Calwer publishing association in 1833.