Schwäbisch Hall

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 49 ° 7 ' N , 9 ° 44' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Baden-Württemberg | |

| Administrative region : | Stuttgart | |

| County : | Schwäbisch Hall | |

| Height : | 304 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 104.23 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 40,440 (Dec. 31, 2018) | |

| Population density : | 388 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 74523 | |

| Primaries : | 0791, 07907, 07977 | |

| License plate : | SHA, BK , CR | |

| Community key : | 08 1 27 076 | |

| LOCODE : | DE SHL | |

| City structure: | 17 districts | |

City administration address : |

Am Markt 6 74523 Schwäbisch Hall |

|

| Website : | ||

| Lord Mayor : | Hermann-Josef Pelgrim ( SPD ) | |

| Location of the city of Schwäbisch Hall in the Schwäbisch Hall district | ||

Schwäbisch Hall (1802–1934 officially just Hall - as it is colloquial to this day) is a town in the Franconian north-east of Baden-Württemberg, about 37 km east of Heilbronn and 60 km north-east of Stuttgart . It is the seat of the district and the largest city in the Schwäbisch Hall district and forms a medium-sized center in the Heilbronn-Franconia region .

The industrial settlement on the Franconian royal estate , which was built around a saltworks in the Middle Ages and was first documented with certainty for the first time in 1156, became a royal Hohenstaufen town. In 1280 Hall achieved the status of an imperial city in the Holy Roman Empire and was able to maintain it until it was mediatized in 1802.

Schwäbisch Hall has been a major district town since October 1st, 1960 .

The city is known for the Heller named after it as well as for the salt boilers , the Bausparkasse Schwäbisch Hall and the open-air plays on the grand staircase in front of St. Michael .

geography

Geographical location

Schwäbisch Hall is located at an old source of salt in the rugged cut Kocher , in which both sides several steep limestone - blade open. The newer districts and incorporated places are mostly located on both sides of the river on the plateau of the Haller level , which is surrounded by the greater heights of the Swabian-Franconian Forest . The urban area is part of the natural areas of the Swabian-Franconian Forest Mountains , Kocher-Jagst-Ebene and Hohenloher-Haller Ebene .

Neighboring communities

The following towns and communities border the town of Schwäbisch Hall ( clockwise , from the north): Untermünkheim , Braunsbach , Wolpertshausen , Ilshofen , Vellberg , Obersontheim , Michelbach an der Bilz , Rosengarten , Oberrot , Mainhardt and Michelfeld (all districts of Schwäbisch Hall ) as well Waldenburg and Kupferzell (both Hohenlohekreis ).

The city of Schwäbisch Hall has entered into an agreed administrative partnership with the communities of Michelbach an der Bilz, Michelfeld and Rosengarten .

City structure

The urban area of Schwäbisch Hall is divided into a total of 17 districts .

As early as the 1930s, the previously independent communities of Steinbach and Hessental were incorporated and thus became districts of Schwäbisch Hall.

In the course of administrative reform in the 1970s an additional seven surrounding villages were incorporated and the villages within the meaning of Baden-Wuerttemberg Municipal Code equipped, they have a Ortschaftsrat , which a mayor projects.

| district | Coat of arms 1 | Incorporation | Resident December 31, 2017 |

Living spaces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City center | 2758 | City center, Katharinenvorstadt, Weilerwiese, Gelbinger Gasse and Vorderer Galgenberg | ||

| Northern core city | 955 | Rippergstraße, Spinnerei, Auwiese, Diak and Wettbach | ||

| Kreuzäcker | 3984 | Lehen, Kreuzäcker, Herrenäcker, Klingenberg and Friedensberg | ||

| Southern core city | 908 | Lindach, Ackeranlagen, Unterlimpurger Straße and Oberlimpurg | ||

| Tullauer Höhe / Hagenbach | April 1, 1935 2 | 3062 | Hagenbach , Tullauer Höhe, middle school, Hagenbach settlement and school center west | |

| Rollhof / tire yard | 3424 | Rollhofsiedlung, Alter Rollhof, train station, Reifenhof and Sonnenhof | ||

| Stadtheide | 503 | Stadtheide (industry) and Stadtheide | ||

| Heimbach settlement / Teurershof | 5933 | Heimbach settlement, Teurershof I, Teurershof II, Heimbach 3 and An der Breiteich | ||

| Steinbach | October 1, 1930 | 1054 | Kocherwieseniedlung, camping site, Comburg, Loh, Kleincomburg, prison garden and barrel factory | |

| Hessental | July 1, 1936 | 7195 | Hessental town center, industrial area, Wasenwiesen, Grundwiesensiedlung, Hessental train station, Ghagäcker, Kühläcker, Mittelhöhe and Schenkensee | |

| Bibersfeld |

|

June 1, 1972 | 1664 | Town center Bibersfeld, Hofäcker, Bühl, Baindäcker, Hohenholz, Sittenhardt, Wielandsweiler and Starkholzbach |

| Gailenkirchen |

|

January 1, 1972 | 2293 | Gailenkirchen town center, Wackershofen, Sülz town expansion , Gottwollshausen town center , Schleifbach and Riegeläcker |

| Gelbingen |

|

1st January 1975 | 692 | The center of Gelbingen, Sonnenhalde, Schutzberg, Kocherhalde, Erlach |

| Eltershofen |

|

July 1, 1973 | 731 | The center of Eltershofen, Riedwiesen and Breitenstein |

| Waking peace |

|

January 1, 1972 | 421 | Weckrieden town center |

| Tüngental |

|

January 1, 1972 | 1500 | Tüngental town center, Schönäckersiedlung, Brunnenwiesen, Ramsbach , Veinau , Altenhausen , Wolpertsdorf and Otterbach |

| Sulzdorf |

|

January 1, 1972 | 2904 | Town center Sulzdorf, Kirchäcker, industrial area, Matheshörlebach , Jagstrot , Hohenstadt , Anhausen , Buch and Dörrenzimmern |

Division of space

According to data from the State Statistical Office , as of 2014.

Spatial planning

Schwäbisch Hall forms a middle center within the Heilbronn-Franconia region , in which Heilbronn is designated as a regional center . The central area of Schwäbisch Hall includes the towns and communities in the southwestern half of the Schwäbisch Hall district: Braunsbach , Bühlertann , Bühlerzell , Fichtenberg , Gaildorf , Ilshofen , Mainhardt , Michelbach an der Bilz , Michelfeld , Oberrot , Obersontheim , Rosengarten , Sulzbach-Laufen , Untermünkheim , Vellberg and Wolpertshausen .

history

Surname

Schwäbisch Hall is usually only called “Hall” in the oldest documents. This word is a typical place name for salt production, which may refer to the salt boiling in the salt works. The city did not belong to the early medieval Duchy of Swabia, but to the Duchy of (Eastern) Franconia.

A single designation as "Hallam in Suevia" in the chronicle of Gislebert von Mons (1190) can probably be explained by the fact that the city belonged to the domain of the Hohenstaufen at that time and in this case the name of their most important property, the Duchy of Swabia , was transferred to all of their possessions. The permanent designation as "Schwäbisch" Hall is of a later date and has its cause in violent conflicts that the now imperial city fought in the 14th and 15th centuries with the district court of Würzburg responsible for the area of the Duchy of Franconia .

In 1442 the council declared that the city was called Schwäbisch Hall and was located on Swabian soil, i.e. outside the jurisdiction of the Würzburg court.

In 1489 the council made a formal resolution to name the city in all official correspondence as Schwäbisch Hall ( Latin: Hala Suevorum) . As a consequence, Schwäbisch Hall joined the Swabian Imperial Circle in 1495 , although most of the ruled areas in the neighborhood belonged to the Franconian Imperial Circle .

When the city came to Württemberg in 1802, the addition "Swabian" was officially deleted from the city name (probably as an unwanted reference to institutions of the Old Kingdom ), but remained in use in everyday language. Until 1806, the name also had the official component "am Kocher".

During the Third Reich, the term "Swabian" was again an official part of the name in 1934. This was used to distinguish it from other places called Hall, such as. B. Hall in Tirol .

The name for the local dialect as well as the rule and its territory is Hallish .

Salt extraction

The city achieved an important position in politics and economics in the Middle Ages and the early modern period. While other trades were important for its economy in the late Middle Ages (including cloth makers and leather workers), it increasingly concentrated economically on its salt source, which provided prosperity for centuries. It is a salt water spring that was tapped near the river, on today's Haalplatz, where the stone parapet of the covered well has been preserved. The salinity of the brine (the salty groundwater) was 4 to 8 percent. The decisive factor for the city, however, was its lack of competition. The closest salt pans with relevant salt production were far away: Lorraine salt pans such as in the Salzgau or the salt springs in the Alpine region. Due to the limited transportability of salt, Schwäbisch Hall was able to act in the space between the big players. In the 16th century, the Duchy of Württemberg was continuously looking for solutions to develop its own salt works in order to become independent from Schwäbisch Hall.

The technology of the Haller Saline was only innovative to a limited extent. In the Middle Ages and in the early modern period there were frequent problems with inrushing river water, which resulted in large losses. At the beginning of the 18th century, the new grading technology was used so that one could keep up with the production quantities of the other grading salines. The grading technique significantly reduces fuel consumption, which makes the end product significantly more profitable. The city's heyday only ended with the advent of salt mines. Test drillings were carried out to find out where the salt store was located, but these efforts ultimately proved fruitless (see Wilhelmsglück rock salt mine ). A rock salt works could be built in 1824 and operated for several decades, but the unique selling point that the Halle saltworks enjoyed up to this point in time had disappeared. After the mediatization, the municipal salt works came into the hands of Württemberg. Their influence quickly waned until the salt works closed in 1924.

Prehistoric times and antiquity

Human settlements in today's urban area can be traced for the first time in the Neolithic Age (around 6000 BC). They were located on the heights above the Kochertal, including in the area of today's Kreuzäckersiedlung and the sub-community of Hessental. The operation of a Celtic saltworks in today's urban area was possible for the 5th to 1st century BC. Be proven. Salt was extracted from the saline groundwater that escaped there by heating .

middle Ages

A continuity between the ancient settlement and the medieval Schwäbisch Hall has not yet been proven. The earliest documentary evidence for the existence of Hall is the Öhringer foundation letter , an allegedly forged document which is dated to 1037, but probably dates from the last years of the 11th century. The reason for the emergence of the medieval settlement in the defensive valley floor was the saltworks . At first the city belonged to the Counts of Comburg-Rothenburg, after their extinction around 1116 it passed to the Staufer . The city developed in several steps in the 12th century. Schwäbisch Hall is mentioned for the first time in a document in the consecration certificate of St. Michael's Church from 1156. In 1204 Schwäbisch Hall was first referred to as a city. Coin minting, trade and saltworks gave it an economic boom.

Coinage

Coins have been minted in Hall since the High Middle Ages; Silver pennies, which were called “Haller Pfennige” or “ Heller ” after their place of origin . Based on a document from 1189 , Frederick I, from the Hohenstaufen dynasty, is considered to be the originator of this coin. The document was obviously changed afterwards. The mention of Heller is on a part of the parchment deed that has been scraped off and overwritten. Historians therefore assume that the Hall city council later tried to legitimize its right to coinage historically. This assumption is supported by the fact that no Heller find from the 12th century is known to date. In contrast, large numbers of coins from the early 13th century have been found. It is possible that the Heller is the creation of a successor to Emperor Friedrich. The low-value coin made of thin sheet silver became a means of payment for large sections of the population throughout the Holy Roman Empire . The mint marks of the Heller are cross and hand, symbols of law and the market. It was not until 1396 that the right to mint coins was transferred from the imperial ministerials to the imperial city itself.

trade

Trade was conducted into the city through a ford in the Kocher . As part of the Hohenstaufen city fortifications, the Sulferturm secured the lucrative passage for carts. Several marketplaces developed as centers of trade within the city walls: a cattle market, a milk market and a fish market as well as sales rooms for meat, salt and bread. The square in front of St. Michael developed into the main market . The city's prosperity increased particularly between 1150 and 1400. During this time, one arm of the stove was filled in, which separated the settlement and the saltworks, creating the Blockgasse. In the 14th century, the city expanded to the other side of the Kocherufer in the Katharinenvorstadt and to the north in the Gelbinger Vorstadt. Because of the geographical proximity to their territorial power in the Rems Valley and to the Swabian-Franconian border, the town was of political relevance for the Hohenstaufen in addition to its economic importance. In 1190 Henry VI. held a court day here, of which Gislebert von Mons claimed that 4,000 princes, nobles and knights had come together. This information is probably exaggerated, but testifies to the cultural and courtly splendor of the Staufer period.

Political structure

The “Vienna arbitration” by King Rudolf von Habsburg in 1280 ended a long conflict with the Limpurg taverns for city rule and enabled Schwäbisch Hall to achieve the status of an imperial city . The dominant class was the city nobility that had emerged from the Hohenstaufen ministerial. After internal unrest they had to cede part of the rule to the non-nobles. The constitutional charter of Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria from 1340 remained valid with minor changes until 1802. The most important body was the council, headed by the town master (mayor). This council consisted of twelve nobles, six "middle class" and eight craftsmen. The domination of the city nobility was finally broken by the "Second Discord" from 1509 to 1512. As a result, a bourgeois, increasingly academically educated upper class dominated the city, including the ancestors of the theologian and resistance fighter Dietrich Bonhoeffer .

At the edge of the flat valley basin of the Otterbach lies north of the village Altenhausen opposite the remains of the castle hill of the Altenhausen moated castle . A little north of the hamlet of Buch are the remains of Buch Castle . In the valley hamlet of Anhausen , in the triangle where the Schwarzenlachenbach flows into the Bühler , an open-air church square was laid out in the 1970s within the walls of the Anhausen Church , which was demolished in the 19th century and is the original church of the now much larger Sulzdorf about 2 km upstream. A little east of a small lake between the hamlets of Anhausen and Hohenstadt, above the left Bühler slope, between the lake drain and a run, there is another castle stable ; a small part of the wall was restored. On a spur to the west above the Bühlerschling between the hamlet of Hohenstadt on the Haller level and the Mühlenweiler Neunbronn in the valley, a deep ditch and a high castle hill indicate where Hohenstein Castle once stood. Opposite it, on an almost leveled old circular mountain above the eastern slope of the valley, almost nothing but heaps of rubble reveal the location of Hohenstatt Castle . On an eastern spur on the left side of the Bühler valley above the Wolpertshausen valley town of Cröffelbach lies the Bielriet castle ruins .

expansion

In the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, the imperial city systematically expanded its territory. They bought rulership rights whenever the opportunity arose and defended them by force of arms if necessary. The last major acquisition was in 1595 when the Vellberg estate was bought . At the end of the Old Kingdom, the imperial city of Schwäbisch Hall owned a territory of 330 square kilometers and around 21,000 inhabitants. It comprised three cities, 21 parish villages and 90 villages and hamlets. The area was divided into the offices of Kocheneck , Rosengarten , Bühler , Schlicht , Ilshofen , Vellberg and Honhardt .

Early modern age

Age of denominational tension (1517-1648)

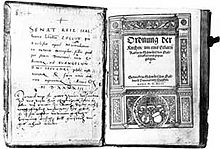

In 1523, the theologian Johannes Brenz , who had been active since 1522, initiated the transition to the Reformation , which was completed with the church ordinance of 1543. At Christmas 1526 he celebrated the Lord's Supper for the first time in both forms in St. Michael . In the Peasants' War of 1525, the imperial city was one of the few rulers in the region to hold its own against the rebellious peasants. To participate in the Schmalkaldic war on the Protestant side, the city of heavy fines to the emperor had Charles V paid. The city master Johann Christoph Adler signed the Lutheran concord formula of 1577 for the city council .

During the Thirty Years' War, the city suffered heavily from changing occupations by Imperial, French and Swedish troops. Between 1634 and 1638 every fifth inhabitant died of disease and starvation. Nonetheless, after the end of the war, it quickly rose again, which was partly due to a reorganization of the salt trade and the salt works. Another source of wealth for the city was the wine trade .

Multiple fires devastated the city. In 1316 large parts are said to have burned down, in 1680 a fire triggered by lightning destroyed around a hundred buildings in the Gelbinger suburb.

City fire of 1728

On August 31, 1728, two thirds of the old town was destroyed by flames. The cause was a fire that broke out in the “Zum güldenen Helm” inn below the town hall (at today's milk market) during a meeting of the Bader guild. In addition to 294 private houses, two churches, the hospital , the town hall and the saltworks were burned . Only the southern old town with the two Herrengassen and the Keckenhof, St. Michael and the surrounding buildings, the Gelbinger suburb and the suburbs on the other side of the Kocher were spared. The citizens' attempts to extinguish the fire were unsuccessful because, on the one hand, the fire engine itself burned and, on the other hand, fighting with water buckets was not very effective. For this purpose, the buckets filled at a well were passed to the scene of the fire using a human chain. Every citizen in Schwäbisch Hall was obliged to keep such a bucket. In order to return the buckets to their owner after use, the city council had ordered them to be labeled with house numbers or names. The reconstruction was carried out in the Baroque style , which has shaped the cityscape to this day , but the medieval quarters were retained apart from the newly planned Neue Straße. Artists who previously worked at the Württemberg court in Ludwigsburg , such as the Italian Livio Retti (1692–1751), were now active in and for Schwäbisch Hall. The destroyed residential buildings in the old town were rebuilt according to a regularized floor plan, which is particularly evident in the dead straight Neue Straße. The baroque change in taste was so great that a splendid music salon was installed in the undamaged Keckenturm.

19th century

Incorporation into the state of Württemberg

The year 1802 heralded the end of Schwäbisch Hall's independence in the imperial city : In the Paris Treaty of May 20, 1802 , France guaranteed not only the continued existence of the Duchy of Württemberg , but also territorial compensation for losses to France on the left bank of the Rhine. The imperial city of Hall, along with other territories, was also intended to compensate for the territorial cedings of Württemberg agreed between France and Duke Friedrich II of Württemberg in the Treaty of Paris . While Prussia and Austria took possession of the compensation countries they had been awarded in June and August 1802, respectively, and immediately took over administration, Frederick II was still reluctant to follow the example of these large states. The city's independent minting of coins ended as early as 1798.

But when the compensation plan of June 3, 1802 was published in the French state newspaper Moniteur in the last days of August , legend has it that Frederick II longed for the day of possession "with nervous impatience". On September 5, 1802, Frederick II announced the provisional military occupation of the imperial city of Hall. The city had not remained idle, however. The Haller appealed directly to their highest city lords - the Roman-German emperor . In a letter dated September 4, 1802, the city council asked the emperor to guarantee that the previous legal system and privileges would remain in force even in the event of incorporation into the Württemberg state.

However, all of these efforts were unsuccessful. On September 9, 1802, the provisional military occupation of Schwäbisch Hall by Württemberg took place. About 100 Württemberg soldiers held a parade on the market square that day. In the meantime, the Duke of Württemberg had already made preparations for the final, so-called "civilian possession". In order to guarantee the uniform approach of the Württemberg commissioners, Friedrich II had an extensive catalog of instructions drawn up, which the delegates in all places had to adhere to exactly. In 18 paragraphs it was stipulated, among other things, that all servants and officials had to take an oath to their duke. In addition, the previous coats of arms and symbols expressing the old sovereignty had to be removed and the ducal coat of arms affixed to all public buildings and gates.

On November 25, 1802, the military marched again with great pomp on the market square, while in the town hall the city council and officials were released from their previous rights and duties and sworn in to the new sovereign. A bang and trumpet sound accompanied the exchange of the imperial city coats of arms with Württemberg ones on the town hall, on the gates and on other public buildings. Not only the civil servants, but also the district contingent were committed to the new sovereign; General von Mylius took over 46 men into the ducal military. According to reports from Rentkammerherr Dörr, the people of Hall were indifferent to the change to the rule of Württemberg. Nowhere did the ducal army have to militarily secure the oaths.

The city became the seat of the upper office of the same name , its associated cities and villages became independent communities of various higher offices. For the city of Hall a long phase of stagnation and regression began. The Napoleonic Wars ruined the city's finances. By the boundaries of the Kingdom of Württemberg newly established state merchants and craftsmen from Hall of their traditional markets in now to have the Kingdom of Bavaria related francs cut off.

Institutions and companies

The traditional grammar school was downgraded to a Latin school in 1811. The state took over the saltworks , which had previously been privately owned by numerous citizens. The compensation negotiations dragged on until 1827. The agreed "perpetual annuities" are still paid to the descendants of the owners at that time; However, since no inflation adjustment was agreed, they have largely lost their value. The salt works closed in 1924. Since the city was the seat of the Oberamt Hall , other authorities settled there, for example a camera office in 1807 (since 1919 tax office) or in 1811 the Oberamtsgericht (district court since 1879). Of particular importance were the establishment of a prison ordered in 1839, whose new building on the edge of the old town had been used since 1846, as well as the establishment of the District Court (since 1879 Regional Court) as a higher authority for the Higher and District Courts (repealed in 1932 despite protests). In addition, there was the employment office established by the city in 1896 (state-run since 1927) as well as institutions for school, rail, post and telegraph, road construction, customs and military administration .

Revolution of 1848

During the revolution of 1848/49 riots broke out in Schwäbisch Hall, but this did not result in open violence. A political association, the forerunner of today's parties , the Fatherland Association, was founded early on, but it was not democratic but constitutional, i.e. it worked towards a constitutional monarchy . The activities of the association were largely limited to the preparation and implementation of the elections for the German National Assembly in the Paulskirche at the beginning of May (an election day had not been set). The majority of the citizens elected the Stuttgart professor Wilhelm Zimmermann , a moderate republican, to the Frankfurt National Assembly .

After that, the club fell into political lethargy; there was probably too much trust in “those up there in Frankfurt” and that “they will probably sort it out”. Its lack of structures and chaotic procedures had already been lamented beforehand. On June 13th , the Democratic Association was established on the initiative of the teacher Rümelin , who was also instrumental in founding the Fatherland Association. This was now explicitly republican and democratic and attracted many members of the Patriotic Association. In a short time it gained a large number of visitors and thus became a reflection of the rampant radicalization of the population, which had left behind the moderate notions of the “pastoral” fatherland association, which eventually merged into the democratic association.

In autumn 1848, the Württemberg government had the city occupied by troops because of the “anarchic spirit” of the citizens. Some local Republican leaders were imprisoned on the Hohenasperg and some of them later emigrated to the USA . By the end of the Empire, the majority of the citizens was minded liberal left and chose appropriate deputies in the Reichstag and parliament . A local association of the SPD was founded in 1864, it was soon able to establish itself as a representative of the workers and win up to a quarter of the votes in elections.

Industrial revolution

The industrialization in essence, the only hesitantly began in Schwäbisch Hall, could only compensate for the loss of jobs in traditional crafts. The connection to the network of the Württemberg railway through the opening of the line to Heilbronn in 1862 did not result in any fundamental change, but favored tourism and the development as a health resort. Numerous residents emigrated to the nearby metropolitan areas and overseas, which is why the population rose only slowly in the 19th century. It was not until the 20th century that larger new settlements emerged outside of the old city area. The city was able to regain its function as a regional educational center; In 1877 it was possible to restore the high school. An important step in the development of the service center was the foundation of the deaconess hospital in 1886 , which is now one of the largest employers in the city.

20th century

In the age of world wars

During the First World War the city was a hospital location . During the Weimar Republic there was a profound change in the political climate. The left-liberal DDP quickly lost its approval, the majority of the bourgeoisie turned to the German National People's Party (DNVP), hostile to the Weimar Republic , which appeared as a citizens' party in the People's State of Württemberg . A local group of the NSDAP , led by the teacher and later Minister-President of Württemberg, Christian Mergenthaler , came into being in 1922 and had 180-200 members in the following year, but disintegrated again after 1925 and was not rebuilt until 1930. Until the elections of 1932 and 1933, the SPD remained the strongest political force in Schwäbisch Hall.

A characteristic of the 1920s and 1930s is a strong growth in tourism , which was attracted by the picturesque old town and the revitalized customs of salt boilers. The brine bath, on the other hand, could not recover from the war-related incision and did not regain its old importance. The open-air theater on the grand staircase in front of St. Michael, founded in 1925 as the Jedermann Festival, continues to attract a national audience. From the 1920s the city began to grow beyond the boundaries of the old town. In particular through the settlements on the Tullauer Höhe (1931) and the Rollhofsiedlung (1st construction phase 1933), the city slowly spread to the surrounding mountain ranges. This process continued during the National Socialist era - the war victims' settlement built from 1939 , today the Kreuzäckersiedlung, was considered a National Socialist showcase project - as were the efforts to incorporate them. Steinbach had already come to Schwäbisch Hall with the Comburg in 1930, followed by the previous Bibersfeld district of Hagenbach in 1935, and Hessental in 1936. As part of the administrative reform during the Nazi era in Württemberg , the area of the old Upper Office Hall (since 1934 called "District" instead of "Upper Office") was transferred to the district of Schwäbisch Hall .

In 1936 Schwäbisch Hall became a garrison town with the construction of the Schwäbisch Hall-Hessental air base for the Luftwaffe . During the Second World War , mainly bombers and night fighters as well as the world's first mass-produced jet fighter , the Messerschmitt Me 262 , were stationed here. In a camouflaged plant nearby, forced laborers etc. a. machines of this type are also assembled. After the Second World War until 1993, the air base was a location of the US Army under the name "Dolan Barracks".

The Jewish community , which was still 121 people in 1933, was wiped out by the flight of its members and the deportation and murder of the Jews who stayed here. About 40 Jews from Schwäbisch Hall fell victim to the National Socialist persecution of Jews. The memorial book of the Federal Archives for the victims of the National Socialist persecution of Jews in Germany (1933-1945) lists 37 Jewish residents of Schwäbisch Hall who were deported and mostly murdered .

The Jewish prayer room in Haller Oberen Herrngasse 8 and the Steinbach synagogue at Neustetterstraße 34 were affected by the November pogrom of 1938 . A memorial stone on Hall's market square and a memorial plaque on the site of the Steinbach synagogue remind of this . As part of the so-called "euthanasia" in 1940 in the wake of were T4 and 270 occupants of the home for handicapped persons of Diakonissenanstalt removed and mostly murdered. In 1944 the Hessental concentration camp was established. It had up to 800 prisoners who had to carry out repair work, mainly on the air base. At least 182 of them died from murder, starvation and disease. A memorial in the Hall cemetery commemorates the Polish concentration camp inmates and prisoners of war. A memorial stone next to the mass graves in the Steinbach Jewish cemetery commemorates these dead. The Hessental death march claimed more victims in the Allach subcamp of the Dachau concentration camp . Two deserters were hanged from trees on April 2, 1945 by SS men between the Limpurg Bridge and the wooden walkway. A deserter memorial erected there in 1990 by a group of artists without permission was later destroyed by strangers. American troops occupied the city on April 17, 1945. The old town was largely spared from war damage. Only the town hall was hit by fire bombs during an American fighter-bomber attack on the morning of April 16, 1945. Only the outer walls and part of the inner walls survived the fire, the basement with the archive and the council library remained undamaged. Almost all of the artistic equipment, including the paintings by Livio Retti , perished.

post war period

In 1945 Schwäbisch Hall became part of the American zone of occupation and belonged to the newly founded state of Württemberg-Baden , which was incorporated into the current state of Baden-Württemberg in 1952.

On May 23, 1945, the new municipal council decided to rebuild the destroyed town hall. The topping-out ceremony was celebrated on September 16, 1946, and the tower crown was put on on July 17, 1947. The interior was finished in 1953, with color photo documentation from 1943 providing important services. The inauguration took place on April 30, 1955.

In the 1950s, the population of Schwäbisch Hall exceeded the 20,000 mark. As a result, the city administration submitted the application for a major district town , which the Baden-Württemberg state government then granted with effect from October 1, 1960. In the course of the community reform of the 1970s, the communities Tüngental, Weckrieden, Sulzdorf, Gailenkirchen, Bibersfeld, Gelbingen and Heimbach came to the city of Schwäbisch Hall. During the district reform on January 1, 1973, the district of Schwäbisch Hall received its current size.

Club Alpha 60 was founded in Schwäbisch Hall in 1966 and is considered to be Baden-Württemberg's oldest socio-cultural center. Since then, the club alpha 60 e. V. for (local) political controversies and is an event location.

In 1982 the city hosted the third state horticultural show in Baden-Württemberg.

21st century

Today Schwäbisch Hall is the education, service and cultural center of the region and the location of some medium-sized companies v. a. of mechanical engineering. Since 1944, the city has been the seat of the "Bausparkasse der Deutsche Volksbanken AG", which at that time moved from war-threatened Berlin. Today, as Bausparkasse Schwäbisch Hall AG, it is the largest local employer and until 2001 was also the largest business taxpayer.

In 2006, the city celebrated its 850th anniversary with numerous activities (counted from the first documented mention of St. Michael's Church).

In 2015 Schwäbisch Hall was awarded the honorary title of “ Reformation City of Europe ” by the Community of Evangelical Churches in Europe .

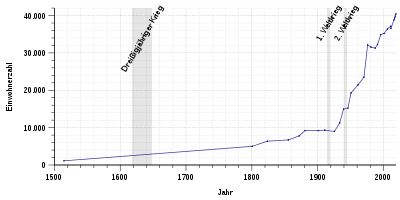

Population development

Population figures according to the respective area. Primary residences only.

| Deadline | Residents | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1514 | (1,124) | households |

| 1800 | 5,000 | approximately |

| 1823 | 6.374 | |

| 1855 | 6,720 | |

| December 1, 1871 | 7,793 | |

| December 1, 1880 | 9.222 | a |

| December 1, 1900 | 9.225 | a |

| December 1, 1910 | 9,321 | a |

| June 16, 1925 | 8,978 | a |

| June 16, 1933 | 11,239 | a |

| May 17, 1939 | 14,964 | a |

| December 1945 | 15,232 | |

| September 13, 1950 | 19,266 | a |

| Deadline | Residents | Note |

|---|---|---|

| June 6, 1961 | 21,458 | a |

| May 27, 1970 | 23,505 | a |

| December 31, 1975 | 32,129 | |

| December 31, 1980 | 31,562 | |

| May 25, 1987 | 31,289 | a |

| December 31, 1990 | 32,226 | |

| December 31, 1995 | 34,910 | c |

| December 31, 2000 | 35.192 | b |

| December 31, 2005 | 36,364 | b |

| December 31, 2010 | 37,137 | c |

| May 9, 2011 | 36,548 | a |

| December 31, 2015 | 38,827 | c |

| December 31, 2016 | 39,328 | c |

| December 31, 2017 | 39,818 | c |

| December 31, 2018 | 40,440 | c |

Religions

The area of the city of Schwäbisch Hall originally belonged to the diocese of Würzburg and was assigned to the regional chapter of Hall. The theologian Johannes Brenz , appointed by the council as preacher of St. Michael , introduced the Reformation in the imperial city from 1522 . The printed church ordinance of 1543, which became binding for town and country, can be considered the final point of their implementation . With reference to the law of bishops , the Hall council also implemented the Reformation in the parishes of the rural chapter. The parishes then de facto formed a Halle regional church under the supervision of the Imperial City Council. The last Catholic church in the city (St. Johann) was closed in 1534. The introduction of the Augsburg interim , enforced by Emperor Charles V in 1548 , temporarily (until 1558/1559) brought early church clergy back to the pulpit, but remained a mere episode. The city then remained purely Protestant until the 19th century . Since the transition to Württemberg belonged and include the parishes of the city to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Württemberg . The parishes in the Hospital, St. Urban (Unterlimpurg) and St. Johann (with Gottwollshausen) were abolished in 1812; after that there were only the two parishes St. Michael and St. Katharina left in the city. Schwäbisch Hall remained the seat of a deanery (see Schwäbisch Hall church district ), to which the parishes of the entire surrounding area belong today. In 1823 the city also became the seat of the General Superintendent Hall . Today's Schwäbisch Hall parish consists of the parish of St. Michael and St. Katharina (for the inner city, after the two inner city parishes were merged in 2004), the Johannes Brenz parish (for Rollhof and Reifenhof, founded in 1955), the Kreuzäcker parish ( in the Kreuzäckersiedlung, founded in 1964), the Sophie-Scholl-Gemeinde (for Heimbachsiedlung and Teurershof, founded in 1992) and the Lukasgemeinde (Hagenbach, founded in 1976). In addition, there is - a Schwäbisch Hall specialty - the local association of the South German Community, which has been integrated into the overall church community since 2002 as a "community parish" without a fixed area . There are other Protestant parishes in the city in the districts of Bibersfeld, Gailenkirchen, Gottwollshausen, Gelbingen, Eltershofen, Hessental, Steinbach, Sulzdorf and Tüngental.

In addition, there are Protestant free church communities in Schwäbisch Hall , including an Adventist community (on Crailsheimer Strasse), an Evangelical Free Church community in Hessental (Eberhard-Heim-Strasse) and a United Methodist Church (Christ Church on Säumarkt). The New Apostolic Church is also represented by two parishes in the Hall district (Schwäbisch Hall and Hessental). The municipality of Rollhof was closed in 2016. The Jehovah's Witnesses are also represented in the Hessental district (Einkornstrasse).

Since the Reichsstift Comburg remained Catholic and in the course of the Counter-Reformation also kept its possessions in this denomination or re-Catholicized, villages that were in its possession or in which it had a share remained either wholly or partially Catholic or became again (according to the Schwäbisch Haller Districts Steinbach, Hessental and Tüngental). The seat of the parish was in Steinbach. After the end of the imperial city in 1802, Catholics again settled in Schwäbisch Hall itself. The construction of the railway brought about a first move towards settlement in the 1860s, and another, larger one, the influx of refugees and expellees after 1945. Since 1887 there has been a separate parish in the city again (St. Joseph). This now looks after the Catholics in the old town, in the eastern part of the city, in the localities of Breitenstein, Eltershofen, Gelbingen and Weckrieden as well as in the neighboring villages of Untermünkheim, Enslingen, restigshausen and Kupfer. The second parish in Schwäbisch Hall, "Christ the King", was founded in 1967; the associated church was built in 1961 in the Heimbach settlement as a subsidiary church of St. Joseph. Today she looks after the Catholics of the districts Heimbachsiedlung, Teurershof, Bibersfeld, Gailenkirchen and Gottwollshausen as well as the neighboring towns of Michelfeld and Gnadental. The third parish, St. Markus, an independent parish since 1980, previously a branch of St. Joseph, is responsible for the Hagenbach district and the Rosengarten community. In other districts of Schwäbisch Hall there are also the Catholic parishes “St. Maria Queen of Peace "in Hessental (also looks after the districts Sulzdorf, Tüngental and the city of Vellberg) and" St. Johannes Baptist ”in Steinbach (also looks after the Michelbach / Bilz community and the Tullau district of the Rosengarten community). The parishes together form two pastoral care units in the Schwäbisch Hall deanery of the Rottenburg-Stuttgart diocese .

A Jewish community already existed in the Middle Ages and was first mentioned in 1241. It was destroyed by a pogrom in 1349 , but was later rebuilt and only finally disappeared in the 15th century. From 1688 onwards there was again a permanent settlement of Jews who, as protected Jews, did not enjoy citizenship and had to live under numerous restrictions. Room synagogues existed in residential buildings in the suburb of Unterlimpurg and in Steinbach. The paneling of the Unterlimpurger room synagogue, which was painted around 1738/1739 by Eliezer Sussmann from Poland , is probably the most important exhibit in the Hällisch-Franconian Museum in Schwäbisch Hall. After the end of the imperial city in 1802, the restrictions were relaxed, they were finally abolished in 1864 due to civil equality. A synagogue had existed in Steinbach since 1809, the Steinbach-Hall Jewish community was constituted in 1828, and a prayer room in Hall was added in 1893. Through immigration from the rural communities in the area, the community grew to 300 members, but then shrank again to 125 in 1933 through emigration overseas and to the larger cities. In the following years, the Jewish community was destroyed by the Nazi terror , its members fled abroad or were deported and murdered (around 40 victims). Between 1946 and 1949, Jewish survivors of the Holocaust lived in three camps in Schwäbisch Hall. Since the 1980s, the city has maintained contact with the former Jewish citizens and their descendants, the v. a. live in Israel and the USA . There have been Jewish citizens again since the 1990s, most of them having moved here from the former Soviet Union .

There are about a thousand Muslims in Schwäbisch Hall ; around 800 of them are Turkish guest workers who came to Schwäbisch Hall in the 1960s and their descendants. In 1979 the Turkish Workers Aid and Sports Association set up a prayer room, and since 2004 the Mevlana mosque of the Turkish-Muslim community has been on Gaildorfer Strasse .

According to the 2011 census , 52.7% of the population of Schwäbisch Hall were Protestant, 19.8% Roman Catholic, 1.9% Evangelical Free Church and 2.3% Orthodox Christians. 4.6% belonged to other religious communities and 18.6% did not belong to any religious community under public law (including Muslims).

politics

Municipal council

The council of the city of Schwäbisch Hall has since the last local elections on 26 May 2019 , 34 members of the "/ Councilwoman City Council" to use the title. The choice brought the following result:

| Parties and constituencies | % 2019 |

Seats 2019 |

% 2014 |

Seats 2014 |

Local elections 2019

% 30th 20th 10

0

28.1%

18.8%

17.5%

15.0%

9.9%

3.9%

3.8%

2.9%

Gains and losses

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GREEN | Alliance 90 / The Greens | 28.1 | 10 | 23.4 | 8th | |

| CDU | Christian Democratic Union of Germany | 18.8 | 7th | 24.9 | 9 | |

| SPD | Social Democratic Party of Germany | 17.5 | 6th | 23.9 | 8th | |

| FWV | Free electoral association | 15.0 | 5 | 18.5 | 6th | |

| FDP | Free Democratic Party | 9.9 | 3 | 9.3 | 3 | |

| THE PARTY | Party for work, the rule of law, animal welfare, elite support and grassroots initiative | 3.9 | 1 | - | - | |

| left | Left list | 3.8 | 1 | - | - | |

| BL | Colorful list | 2.9 | 1 | - | - | |

| total | 100 | 34 | 100 | 34 | ||

| voter turnout | 56.6% | 44.6% | ||||

Mayor

In the 13th century, the stättmeister was probably at the head of the city administration as the representative of the king and holder of the high judiciary, although he was first mentioned in a document in 1307 . He was assisted by a jury court first mentioned in 1249 . The council, which was first mentioned in 1307 and composed of city nobility, evolved from the court as the city's governing body. The judges were now on the council. Since the city acquired the lien on the office of the mayor (1382) as well as many royal rights administered by this office, this office largely lost its importance in favor of the council. In the constitutional charter of 1340, Emperor Ludwig IV decided that the council should consist of 12 “burgers” (aristocrats), six “middle burgers” (the middle burghers were a class of citizens who had become wealthy through handicrafts and trade) and eight craftsmen. At the end of the 15th century, this “Inner Council” was joined by the “Outer” or “Common Council” with 28 members, which had an advisory function. Its members were elected by the Inner Council. In the course of the so-called "Second Discord" (1510–1512), the city nobility lost their dominant position in the council, and the class division of council mandates disappeared. At the head of the Inner Council stood the two town masters ( mayors ) (first mentioned together with the council in 1307), one of whom was the mayor as the “governing town master”. Both the town master and the inner council were elected annually; however, there was no election by the citizens, but rather self-completion from the council. In principle, this organization remained until 1802. From the constitutional amendment of 1552 ("Hasenrat") forced by Emperor Charles V (repealed in 1559 and 1562), only a reduction of the Inner Council to 24 and the Outer Council to 15 persons remained.

After the transition to Württemberg in 1802, the “Municipal Constitution” of 1803 eliminated Hall's imperial city constitution. The independent constitutional history of the city ended with it. As everywhere in Württemberg, developments in the 19th century were characterized by a gradual strengthening of local self-government and democratic elements. From 1819 to 1919 there was the “Citizens Committee” as an advisory body in addition to the municipal council . The election of the councils for life fell during the revolution of 1848/49. From 1803 there were initially two mayors, from 1822 a city school appointed by the king for life. From 1891 the election took place by the citizenship, in 1906 the life of the municipal school authority fell. From 1930 onwards, the mayor held the title of “mayor”, and since it was elevated to the status of a major district town in 1960, its name has been mayor . This is elected directly by the electorate for eight years. He is chairman of the municipal council. His general deputy is the First Alderman with the title of First Mayor.

- 1803–1819: Georg Karl Haspel

- 1819–1828: Johann Friedrich Hezel

- 1829–1848: Lorenz Wibel

- 1848–1881: Friedrich Heinrich Hager

- 1881: Krumrey Town Council, Administrator

- 1882–1887: Otto Wunderlich

- 1887: Krumrey Town Council, Administrator

- 1888–1899: Friedrich Helber

- 1899–1926: Emil Hauber

- 1927–1945: Dr. jur. Wilhelm Prinzing

- 1945–1954: Ernst Hornung

- 1954–1974: Theodor Hartmann

- 1974–1996: Karl-Friedrich Binder

- Since 1997: Hermann-Josef Pelgrim (SPD)

coat of arms

| Blazon : “ Divided into gold and red . Above in a red circle a yellow cross and below a white hand pointingto the head of the shield in a blue circlewith a white border. " | |

| Crest Reason: The coat of arms shows the two sides of the Hellers , a medieval coin in Schwäbisch Hall coined was. |

Town twinning

-

Épinal , Lorraine , France (1964)

Épinal , Lorraine , France (1964) -

Loughborough , Leicestershire , UK (1966)

Loughborough , Leicestershire , UK (1966) -

Lappeenranta , Finland (1985)

Lappeenranta , Finland (1985) -

Neustrelitz , Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania , Germany (1988)

Neustrelitz , Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania , Germany (1988) -

Zamość , Poland (1989)

Zamość , Poland (1989) -

Balıkesir , Turkey (November 2006)

Balıkesir , Turkey (November 2006)

Within the framework of "Municipal Climate Partnerships" of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation :

Culture and sights

Buildings

- Stadtpfarrkirche St. Michael , Gothic hall church

- former Johanniterkirche , see also under museums

- Katharinenkirche , changed in neo-Gothic style

- baroque town hall

- former Josenkapelle

- former grain store and salt store

- Münstermeisterturm , half-timbered house based on a Hohenstaufen residential tower

- former Hospital of the Holy Spirit , founded in 1317/23, today's building in 1731

- Armory

- Hamlet gate

- Torture tower

- Stellwaghaus

theatre

- The Schwäbisch Hall open-air theater, which takes place on the 500-year-old staircase of St. Michael from June to August , was founded in 1925 as the Jedermann Festival . Three productions on the stairs form the core of the festival. From 2000 to 2016 there were also two productions a year in the Haller Globe Theater , a round wooden building on Kocherinsel. Instead of this venue, which was dismantled in autumn 2016, the New Globe, a circular building with a natural stone and glass facade, was opened at the same location in March 2019 . The children's theater and a supporting program round off the festival.

- The Theaterring e. V. offers six plays for adults and two children's plays per season. The venue is the new building hall.

- Gerhards Marionettentheater e. V. mainly performs numerous children's plays in the sheepfold , but also plays for adults.

- The Princess Gisela Theater performs children's plays in the House of Education and as a touring theater, but also amusing magic theater for adults.

Museums

- The Kunsthalle Würth , opened by Gerhard Schröder in 2001 , stands out for its architectural quality. The Danish architect Prof. Henning Larsen planned the modern building. Temporary exhibitions are shown, fed mainly from the holdings of the collector and eponymous entrepreneur Reinhold Würth . So far, large exhibitions by Eduardo Chillida , Max Liebermann , Henry Moore , Horst Antes , Fernando Botero , Edvard Munch , Alfred Hrdlicka and various themed exhibitions have been shown in the Kunsthalle . The exhibitions are accompanied by a supporting program of guided tours, museum educational activities and more. Lectures, concerts and readings take place regularly in the Adolf-Würth-Saal of the Kunsthalle.

- The Johanniterkirche is originally a Romanesque (end of the 12th century), later Gothic extended church on the Henkersbrücke . The church was profaned in 1812 and used differently under the name Johanniterhalle . After the building was acquired by the city, the church was extensively renovated by the Würth Group and an extension was added. Since November 2008, old masters from the Würth Collection have been shown in the Johanniterkirche , including works by Lucas Cranach the Elder ( Saint Barbara, Christ blesses the children, portraits of Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon ). Since January 2012, the Madonna of Mayor Jakob Meyer zum Hasen by Hans Holbein the Younger (also known as Darmstadt Madonna ) has been exhibited in the choir of the Johanniterkirche as the most valuable piece of this collection .

- In the Hällisch-Fränkisches Museum , the town and regional history from the Middle Ages to modern times is presented, along with the local geology. It is based on the collection of the Historical Association for Wuerttemberg Franconia, which was created in 1851. The museum is located in the "Keckenturm" from the Hohenstaufen era and six other buildings connected to it.

- The Hohenloher Freilandmuseum Wackershofen , founded in 1979, is a museum village in the Wackershofen district on 40 hectares. Over 70 historical buildings have now been faithfully rebuilt here. The houses show the original furnishings or corresponding pieces from the same period. They allow an insight into the rural past and culture.

- The gallery on the market shows modern art.

- The house at Lange Straße 49 is a poor house from 1470. The results of its archaeological investigation are presented.

- The fire brigade museum in Hall in the old spinning mill has around 6,000 exhibits on 1,600 m².

Look at Schwaebisch Hall from Museumshof the Kunsthalle Würth from

music

There has been a municipal music school in Schwäbisch Hall since 1971. In autumn 2011 it moved from Engelhardt-Palais in Gelbinger Gasse to the new building for education. Hall also has a city orchestra.

War cemeteries

There are 306 war graves in Hall's Nikolaifriedhof. In its upper part is the grave complex for the bomb victims of the American air raid on Schwäbisch Hall train station on February 23, 1945, which claimed between 48 and 53 lives.

Other sights

- Comburg : The Großcomburg, a former Benedictine monastery, was founded in 1078. The castle-like complex rises on an old mountain surrounding the Kocher above Steinbach. The outdoor facilities, including a parapet walk around the entire building complex, are freely accessible. The collegiate church of St. Nikolas is characterized by the Romanesque towers and the reconstruction of the Baroque period (1706–1715). The rich interior includes Romanesque art treasures such as the wheel chandelier and the altar pendium, which can be visited with a guide. Großcomburg is now home to the State Academy for advanced training and personnel development in schools. The Kleincomburg is the church of St. Giles, donated in 1108 . The Romanesque building is halfway on a valley slope opposite the Großcomburg and is a 15-minute walk away.

- Limpurg castle ruins above the suburb of Unterlimpurg with nearby remains of a prehistoric section wall.

- Einkorn , mountain spur above Schwäbisch Hall-Hessental with observation tower and ruins of the baroque pilgrimage church to the 14 helpers in need .

- Concentration camp memorial at Schwäbisch Hall-Hessentaler Bahnhof, commemorates the Hessental concentration camp (1944/1945).

- Jewish cemetery in Steinbach

- Art automatons by Bernhard Deutsch a . a. on the Henkersbrücke, on Sulfersteg, in the Hällisch Franconian Museum and in the open-air gallery Villa Wunderwelt in Steinbach.

- Aqueduct in the lower Wettbachklinge . The structure used to bridge a valley cut on the route of the old Haller " Röhrenfahrt ", in which water for the supply of the city flowed in a natural gradient from the source area near Breitenstein into the city.

Favorable points of view for an overview of the old town are:

- A small park on Königsberger Straße allows the best view over the station bay to the southern, older inner city parts.

- From the upper edge of the valley slope at the Katzenkopf you can see the central city center around the axis of Neue Straße with the town hall and Michael’s Church behind it.

- From the “Kastengärtle” at the southern corner of the new building you can see into the deep Schiedgraben and across the alleys of the eastern valley slope down to the Kocherpartie and the opposite slope.

- The path on the ridge of the Galgenberg allows a view over the Gelbingen suburb to the left bank of the Kocher.

Sports

- the Schenkensee leisure pool includes an outdoor pool and an indoor pool with an outdoor area and a sauna park ; Other attractions are several slides and a 10 m diving platform in the outdoor area

- The brine bath offers 500 m² of water and a 120 m² salt grotto, a sauna area and various therapeutic facilities; The salt content of the brine , which is 3–4%, is used to treat many diseases and has already attracted spa guests to the cooker over 100 years ago (-> see Old Salt Bath and New Salt Bath )

- the Waldbad Gelbingen, an outdoor pool, is run by a non-profit association

- The Schwäbisch Hall Golf Club operates a golf course in Dörrenzimmern with a total area of 85 hectares

- the Schwäbisch Hall Unicorns club plays American football in the GFL , winning the German championship in 2011 , 2012 , 2017 and 2018

- Every January 6th, the Schwäbisch Haller Dreikönigslauf takes place

- Since 2004, the Sparkassen Bundesliga Cup has been held every summer on the Auwiese

- almost 60 sports clubs offer a wide range of options.

Regular events

- HALLia VENEZiA: Venetian Carnival, always eight days before Rose Monday

- Cake and fountain festival: historical festival of salt boilers on Whitsun, documented since the 16th century

- Jakobimarkt: grocer's market on Haalplatz and amusement park on Kocherwiesen in Steinbach

- Summer night festival: romantic festival of lights in the “Ackeranlagen” city park with lots of music and fireworks

- Medieval Minstrels' Market: every even year

- South German cheese market: in the Hohenloher Freilandmuseum, every May; with many artisanal cheese manufacturers from all regions of Germany and neighboring countries

- Oven festival: the big annual festival in the Hohenloher open air museum with market, fresh blootz from the ovens, dance groups, cattle awards, jugglers and music; on the last weekend in September

- Handicraft Christmas market: one of the most traditional handicraft markets in Germany, where artists and craftsmen present their work to the public or offer children's workshops and musicians perform; from Friday on the weekend of the first Advent

- Christmas market: since 2011 on the historic market square, previously in Gelbinger Gasse

- Formula Mundi : film festival.

Economy and Infrastructure

Trade is of great importance for Schwäbisch Hall's service sector. The catchment area of the city includes around 160,000 inhabitants. The trading centers outside the city center, where the migration of trade to the suburbs was halted in April 2011 with the new Kocher district , are located in the west in the Stadtheide and Kerz (together with Michelfeld ) and in the east in the Hessentaler Gründle. The German Congress of World Market Leaders has been held in Schwäbisch Hall every January since 2011.

traffic

Road traffic

Schwäbisch Hall has a junction on the federal motorway 6 (Heilbronn – Nürnberg). The federal highways 14 (Stuttgart-Nuremberg) and 19 (Ulm-Aalen-Schwäbisch Hall-Würzburg) also run through the city.

Rail transport

At Schwäbisch Hall-Hessental station , the Waiblingen – Schwäbisch Hall-Hessental line meets the Crailsheim – Öhringen – Heilbronn line , whose next stop is Schwäbisch Hall city station .

Bus transport

Local public transport ( ÖPNV ) is served by several local and regional bus routes . All belong to the Transport Association KreisVerkehr Schwäbisch Hall to. In the urban area, currently 11 lines of the Schwäbisch Hall city bus connect the city with its suburbs. The regional bus routes are mainly operated by the two Schwäbisch Hall-based companies Friedrich Müller and Röhler . By linking the city bus lines with the other lines of the Schwäbisch Hall roundabout, the city can be reached by public transport from all major residential areas in the district. In July 2011, the new central bus station (ZOB) was inaugurated near the Kocher district.

Air traffic

Schwäbisch Hall can be reached by plane via the Adolf-Würth-Airport airfield , which was redesigned and expanded in 2004 . The runway is 1,540 meters long and is equipped for visual, instrument and night flight modes.

Established businesses

The city's best-known company is Bausparkasse Schwäbisch Hall , whose subsidiary Schwäbisch Hall Kreditservice is also based here. Another bank, the Sparkasse Schwäbisch Hall-Crailsheim, has one of its headquarters in the city. Medium-sized companies, some of which are market leaders in their segments, dominate industry and trade in Schwäbisch Hall. According to its own statements, Klafs Saunabau is the leading manufacturer of wellness systems. The Optima Packaging Group GmbH is the world market leader in machines for packaging diapers and feminine hygiene products in foil bags, in portion packs such as pads or capsules for coffee and tea and in functional closures for food. Recaro Aircraft Seating and the automotive supplier Behr are represented with a plant in the city, while the solar module developer Nice Solar Energy GmbH is based here. Stadtwerke Schwäbisch Hall is the city's own energy and heat supplier.

Agriculture

The Swabian-Hällische Landschwein is a domestic pig breed that is mainly bred in the northeast of Baden-Württemberg. Since 1988 there has been an association of farms from the Hohenlohe region with the Schwäbisch Hall (besh) farmers' producer group .

media

- the daily newspaper is the Haller Tagblatt , founded in 1788

- On Wednesdays the advertising paper KreisKurier

- the monthly magazine alpha press has been run by Club Alpha 60 e. V. published

- the free, non-commercial radio station StHörfunk has been broadcasting since 1995. The regional radio station Radio Hall was only on the air for a short period (1988–1989).

- the city magazine HALLo, published by the city, appears every two months

Open source

In Schwäbisch Hall, the city administration's IT is operated with open source software. The city also developed a council information system based on MediaWiki . The system is offered to the public and there are no license costs for its use.

Authorities, courts and institutions

Schwäbisch Hall is the seat of the district of the same name. There is also an employment agency and a tax office . Schwäbisch Hall also has a District Court , which the District Court of Heilbronn and the Higher Regional Court heard Stuttgart.

With the introduction of the new Württemberg Criminal Code in 1839, a new district prison was built in Schwäbisch Hall, which was fully occupied in 1847. It was built in an outer corner of the city wall on a swampy stretch of shore at the Kocher ("frog pit"). From 1953 the building served as a youth detention center for the state of Baden-Württemberg. In April 1998, after the completion of new buildings on the southern edge of the Haller Stadtheide near the road to Gaildorf, the current multifunctional new correctional facility was put into operation. The old building of the former juvenile detention center close to the old town will serve as an education center after being vacant and renovated in 2011 .

The city is also the seat of the Schwäbisch Hall church district of the Evangelical Church in Württemberg and the Schwäbisch Hall deanery of the Rottenburg-Stuttgart diocese .

The Evangelical Diakoniewerk Schwäbisch Hall is one of the largest diaconal institutions in Baden-Württemberg . In addition to a central supply hospital, which is colloquially referred to as Diak , residential and nursing homes, outpatient care and training centers for nursing professions are operated. The hospital is an academic teaching hospital of the University of Heidelberg . A total of around 2300 people are employed.

The Schwäbisch Hall City Library has 60,000 media and an online library with 13,000 other digital media.

education

At the Schwäbisch Hall campus founded in 2008, a branch of the Heilbronn University of Applied Sciences , around 950 students are studying for the 2014/15 winter semester. There was also a private, state-recognized Schwäbisch Hall University of Applied Sciences from 1984 to 2013 .

Schwäbisch Hall has two high schools (Erasmus-Widmann-Gymnasium in Schulzentrum West and Gymnasium near St. Michael ), two Realschulen (Leonhard-Kern-Realschule in Schulzentrum West and Realschule Schenkensee), two secondary schools (Hauptschule with Werkrealschule Schenkensee and Thomas ) in general schools -Schweicker-Hauptschule with Werkrealschule in Schulzentrum West), a special needs school (Friedensbergschule) and several elementary schools (elementary school on Langen Graben and one elementary school each in the districts of Bibersfeld, Breitenstein, Gailenkirchen, Gottwollshausen, Hessental, Kreuzäcker, Rollhof, Steinbach and Sulzdorf).

The district of Schwäbisch Hall is responsible for the three vocational schools (vocational school, commercial school and Sibilla-Egen-Schule - home economics school), each of which also has a vocational high school for technology, economics, nutritional science and biotechnology, as well as Wolfgang-Wendlandt -School for the speech-impaired.

The following private schools complete the range of schools in Schwäbisch Hall: Geriatric care school of the Association of Schwäbischer Feierabendheime e. V., Evangelical School for Social Pedagogy Schwäbisch Hall, Evangelical School for Curative Education Care at Heim Sonnenhof, Free Waldorf School Schwäbisch Hall, a private school for the sick and nursing school at the Diakoniekrankenhaus Schwäbisch Hall as well as the Sonnenhof School for the mentally handicapped at the home in independent ownership with a school kindergarten for the mentally handicapped.

The State Academy for advanced training and personnel development in schools is located on the Comburg.

Schwäbisch Hall has also housed a Goethe Institute since 1965 . Students from all over the world get to know the German language and culture here. The institute is located in the center of the old town in the building complex of the former Haller Hospital , where the university of applied sciences was housed until it was closed. In addition to German courses, there are also concerts, lectures, exhibitions and the traditional summer festival.

Name sponsorships

Schwäbisch Hall is the namesake of the ICE 3 Tz4685 of Deutsche Bahn . This train was the first ICE multiple unit to reach London's St Pancras station .

Telephone prefixes

In the city the area code 0791 applies. Deviating from this, Sulzdorf and Tüngental can be reached via 07907 and Sittenhardt and Wielandsweiler via 07977.

Personalities

literature

- Eugen Gradmann : Hall with Oberlimpurg . In: The art and antiquity monuments of the city and the Oberamt Schwäbisch-Hall . Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen a. N. 1907, OCLC 31518382 , pp. 11 ( archive.org ).

- Lucrezia Hartmann: Schwäbisch Hall (= German Land, German Art ). Recordings by Helga Schmidt-Glassner . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1970, DNB 456917462 .

- Alexandra Kaiser, Jens Wietschorke: Cultural History City Lexicon Schwäbisch Hall. Swiridoff, Künzelsau 2006, ISBN 3-89929-079-8 .

- Gerhard Lubich: History of the city of Schwäbisch Hall. From the beginning to the end of the Middle Ages (= publications by the Society for Franconian History. Series IX: Representations from Franconian history. Volume 52). Society for Franconian History, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-86652-952-X .

- Andreas Maisch, Daniel Stihler: Schwäbisch Hall. History of a city. With the collaboration of Heike Krause. Edited by the Schwäbisch Hall city archive and the Schwäbisch Hall history workshop. Swiridoff Verlag, Künzelsau 2006, ISBN 3-89929-078-X .

- Gerhard Strohmaier: History of the Hohenloher Land. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2016, ISBN 978-3-8370-9991-1 .

Web links

- Map of the urban area and the old town area of Schwäbisch Hall. In: State Institute for the Environment Baden-Württemberg (LUBW) ( information )

- Map of the central districts of Schwäbisch Hall. (No longer available online.) In: Geoportal Baden-Württemberg ( information ). Archived from the original on October 23, 2017 .

- official directory of historical buildings

- Digitized manuscript of a Haller Chronik from the beginning of the 17th century from the Lyzealbibliothek in Käsmark

Individual evidence

- ↑ State Statistical Office Baden-Württemberg - Population by nationality and gender on December 31, 2018 (CSV file) ( help on this ).

- ↑ Natural areas of Baden-Württemberg . State Institute for the Environment, Measurements and Nature Conservation Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 2009.

- ↑ Sub-place directory Schwäbisch Hall. Population in the suburbs. In: schwaebischhall.de, accessed on November 12, 2019 (as of December 31, 2018).

- ↑ § 15 Schwäbisch Hall Main Statute of January 26, 2011. (PDF; 75 kB) (No longer available online.) In: schwaebischhall.de. September 22, 2014, p. 9 , archived from the original on March 5, 2016 ; accessed on January 16, 2019 .

- ↑ Sub- locations - City of Schwäbisch Hall. In: schwaebischhall.de. Accessed August 31, 2018 .

- ↑ State Statistical Office: Area since 1988 according to actual use for Schwäbisch Hall. In: statistik-bw.de, accessed on February 3, 2017.

- ^ Terence McIntosh: Urban Decline in Early Modern Germany. Schwäbisch Hall and its Regions, 1650–1750 . In: The James Sprunt Studies in History and Political Science . tape 62 . The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill / London 1997, ISBN 0-8078-5063-2 , pp. 201 f .

- ^ Martin Ott : Salt trade in the middle of Europe . Spatial organization and external economic relations between Bavaria, Swabia and Switzerland 1750–1815 (= series of publications on Bavarian national history . Volume 165 ). Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-10780-1 , pp. 88 (Zugl .: Munich, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 2011).

- ^ Theo Simon: Salt and salt production in northern Baden-Württemberg . Geology - technology - history. In: Research from Württembergisch Franconia . tape 42 . Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1995, ISBN 3-7995-7642-8 , p. 94-107 (parallel edition : Historischer Verein für Württembergisch Franken, Schwäbisch Hall 1995, ISBN 3-921429-42-0 ).

- ↑ Hans-Martin Decker-Hauff: The Öhringer Stiftsbrief . In: Historical Association for Württembergisch Franconia (ed.): Württembergisch Franconia. Yearbook of the Historical Association for Württemberg Franconia . 31 (new series), 1957, ISSN 0084-3067 , p. 17-31 .

- ^ Gerhard Lubich: History of the city of Schwäbisch Hall. From the beginning to the end of the Middle Ages (= publications by the Society for Franconian History. Series IX: Representations from Franconian history. Volume 52). Society for Franconian History, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-86652-952-X .

- ^ A b Gerhard Lubich: History of the city of Schwäbisch Hall. From the beginning to the end of the Middle Ages (= publications by the Society for Franconian History. Series IX: Representations from Franconian history. Volume 52). Society for Franconian History, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-86652-952-X , p. 92.

- ↑ See the confessional writings of the Evangelical Lutheran Church . Published in the commemorative year of the Augsburg Confession 1930 (BSLK) (= Göttingen Theological Textbooks ). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1930; 9th edition. Ibid. 1982, ISBN 3-525-52101-4 , p. 765; see. P. 17 (German, Latin; mostly in Fraktur) ; 13th edition, kart. Study ed. the 12th edition. Ibid 2010, ISBN 978-3-525-52101-4 .

- ↑ Pictures of the city's history. (No longer available online.) In: xn--schwbischhall-efb.de. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011 ; accessed on January 16, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Andreas Maisch, Daniel Stihler: Schwäbisch Hall. History of a city . Ed .: City Archives Schwäbisch Hall and History Workshop Schwäbisch Hall. Swiridoff, Künzelsau 2006, ISBN 3-89929-078-X , p. 252 (with the collaboration of Heike Krause).

- ↑ a b c Philippe Alexandre u. a .: Hall in the Napoleonic era . An imperial city becomes part of Württemberg. Ed .: Manfred Akermann, Harald Siebenmorgen. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1987, ISBN 978-3-7995-4106-0 (catalog of the Hällisch-Fränkisches Museum Schwäbisch Hall).

- ^ Gerhard Schön, German coin catalog 18th century, Schwäbisch Hall, No. 3

- ^ A b c Gerhard Strohmaier: History of the Hohenloher Land . Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2016, ISBN 978-3-8370-9991-1 , pp. 296 .

- ↑ Memorial Book. Search in the name directory. Search for: Schwäbisch Hall - residence. In: bundesarchiv.de, accessed on November 12, 2019.

- ↑ a b Memorials for the Victims of National Socialism. A documentation. Volume 1. Federal Agency for Civic Education , Bonn 1995, ISBN 3-89331-208-0 , p. 80 f. ( Obere Herrngasse 8, preview in the Google book search; Neustetterstraße 34, preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Marcus Haas: "We tried everything". Interview with Hermann-Josef Pelgrim. In: Haller Tagblatt online. March 1, 2014, accessed October 10, 2017 .

- ↑ City portrait of the project “Reformation cities in Europe”: Reformation city Schwäbisch Hall. Germany. In: reformation-cities.org/cities, accessed on February 4, 2017, as well as the city portrait of the project “European Station Path” : Schwäbisch Hall. In: r2017.org/europaeischer-stationweg, accessed on February 4, 2017. For the significance of Schwäbisch Hall in the history of the Reformation, see also the sections Middle Ages and Early Modern Times to 1802 and Religions .

- ↑ Persons by religion (in detail) for Schwäbisch Hall, city (district Schwäbisch Hall) - in% - extrapolation from the household sample. In: zensus2011.de. Reporting date May 9, 2011, accessed on February 4, 2017.

- ^ City of Schwäbisch Hall. Municipal Council 2019. Preliminary final result. In: wahlen11.rz-kiru.de, accessed on May 28, 2019.

- ↑ Frequently asked questions about the city's history, here: What does the city coat of arms show? In: schwaebischhall.de, accessed on February 4, 2017.

- ↑ Hermann-Josef Pelgrim: Review 2018. In: schwaebischhall.de, accessed on December 13, 2019.

- ↑ Internet presence of the largest and oldest puppet theater in Baden-Württemberg. In: gerhards-marionettentheater.de, accessed on February 4, 2017.

- ↑ Internet presence of the hand puppet theater that has existed for almost 3 decades. In: prinzessin-gisela-theater.de, accessed on February 4, 2017.

- ↑ Villa Wunderwelt. In: nurzu.de. Retrieved February 4, 2017 .

- ^ Art-hand-work market in Schwäbisch Hall, 1st Advent. In: nurzu.de. Retrieved April 12, 2016 .

- ↑ Schwäbisch Hall is an economic and growth city. In: schwaebischhall.de, accessed on February 8, 2017.

- ↑ Florian Langenscheidt , Bernd Venohr (Hrsg.): Lexicon of German world market leaders. The premier class of German companies in words and pictures. German Standards Editions, Cologne 2010, ISBN 978-3-86936-221-2 .

- ^ NICE Solar Energy GmbH: Company information . Retrieved August 21, 2019 .

- ↑ OpenSource in the town hall. In: schwaebischhall.de, accessed on February 8, 2017.

- ↑ § 31 - Presentation of the council information system (public). In: schwaebischhall.de. Minutes: Municipal Council (public), February 27, 2002, accessed on February 8, 2017.

- ↑ Home. In: landgericht-stuttgart.de, accessed on September 5, 2011.