People's State of Württemberg

| coat of arms | flag |

|---|---|

( Details ) ( Details )

|

|

| Situation in the German Reich | |

|

|

| Arose from | Kingdom of Württemberg |

| Incorporated into |

Württemberg-Baden ; Württemberg-Hohenzollern |

| Today (part of): | Baden-Württemberg |

| Data from 1925 | |

| State capital | Stuttgart |

| Form of government | Parliamentary democracy |

| Head of state | President |

| Constitution | Constitution of Sept. 25, 1919 |

| Consist | 1918 - 1933 / 1945 |

| surface | 19,508 km² |

| Residents | 2,580,235 (1925) |

| Population density | 132 inhabitants / km² |

| Religions | 68.0% Ev. 30.9% Roman Catholic 0.4% Jews 0.73% others |

| Reichsrat | 4 votes |

| License Plate |

III A, III C, III D, III E, III H, III K, III M, III P, III S, III T, III X, III Y,III Z

|

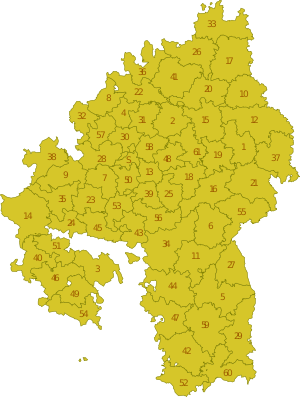

| administration | 1 District 63 (61) Oberämter 1,875 municipalities |

| map | |

|

|

The free people's state of Württemberg was a state of the German Empire during the Weimar Republic . At the end of the First World War , the November Revolution - bloodless in Württemberg - transformed the Kingdom of Württemberg into a people's state . The borders remained unchanged, as did the state administration . According to the new constitution of 1919, which replaced that of the Kingdom of 1819, Württemberg was still a member state of the German Empire and now had the form of a democratic republic , which was described in the constitutional text as a free people's state .

The country's political development in the turbulent Weimar years was characterized by continuity and stability. Unlike the Reichstag , the three legislative periods of the Württemberg state parliament from 1920 to 1932 each reached the duration of four years provided for by the constitution. In contrast to neighboring Baden, the Social Democrats lost their influence on government policy early on. A conservative coalition ruled Stuttgart from 1924 to 1933 . Despite the crises, economic development in Württemberg was more favorable than in other German countries in the 1920s. The state capital Stuttgart was an up-and-coming cultural and economic center.

Through the takeover of the National Socialists in 1933 was also in democracy eliminated Wuerttemberg and lifted the constitutional order of the country. The constitution of Württemberg as a free people's state thus only lasted from 1919 to 1933. The state continuity of the state ended in 1945. The states of Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern that were formed afterwards merged in 1952 in what is now the state of Baden-Württemberg .

geography

The state of Württemberg was part of the German Reich. The total area was 19,508 km². The outer border had a total length of 1,800 kilometers with a variety of territorial features . In the east, Württemberg bordered the Free State of Bavaria , in the north and west on the Republic of Baden and in the south on the Hohenzollern Lands , which belonged to the Free State of Prussia , and Lake Constance . Due to the Hessian exclave Wimpfen , Württemberg also shared a border with the People's State of Hesse . The geographical conditions of the People's State of Württemberg were otherwise the same as in the times of the kingdom and are described in more detail in the chapter Geography (Kingdom of Württemberg) .

history

Emergence

The People's State of Württemberg came into being at the end of the First World War through the abolition of the existing constitution of the Kingdom of Württemberg . The state continuity of the country was not interrupted, but some of the previous self-government rights were subsequently transferred to the German Reich. At the end of the 1880s, representatives of the Württemberg People's Party were already thinking about "The Redemption of the Crown", as a title in the Observer , the People's Party's newspaper, was entitled to . The author of this article was Karl Mayer . In 1907, Conrad Haussmann again represented the idea of a Württemberg republic, but did not find much approval in his party. Even the Württemberg Social Democrats were not as decided on this issue as had been expected. In the Stuttgart SPD party newspaper Schwäbische Tagwacht number 160 of July 13, 1906, under the heading “Democracy or Monarchy”, it was stated that instead of a republic in Württemberg, a parliamentary monarchy could well be imagined. However, this did not become a reality in the liberal Württemberg until November 1918.

The prehistory of the Württemberg revolution

After more than four years of war there was great dissatisfaction and bitterness in large parts of the population in Germany, especially since the Supreme Army Command had to admit at the end of September 1918 that the war was lost. Up until that point in time, the public had always been given the prospect of a victorious outcome of the world war for the Central Powers .

When it became clear that four years of hardship, hardship and suffering had been in vain, the people of Württemberg also took a clearly negative mood. On October 26, 1918, around half of the 8,000 workers in the armaments industry around Friedrichshafen gathered on the market square there to demonstrate for peace. On October 30, 1918, a rally organized by the USPD took place in Stuttgart , at which the Reichstag member Ewald Vogtherr and the Stuttgart Spartakist leader Fritz Rück spoke in front of 5,000 people. Then a manifesto of the Spartakusbund was read out calling for the dissolution of the Reichstag and all state parliaments. A people's parliament consisting of soldiers, workers and peasants should take their place. The rally was followed by a march, but only 2,000 people attended.

On November 3rd, over 3,000 people gathered on the Cannstatter Wasen in anticipation of a speech by Karl Liebknecht . The announcement turned out to be a disappointing false report for those waiting, since Liebknecht was not in Stuttgart. On November 4, 1918, on the initiative of the Spartacists, there was a large demonstration in Stuttgart, during which over 10,000 workers marched through the city center and heard a speech by Fritz Rück on the Schloßplatz in which the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and also of Württemberg's King Wilhelm was challenged. On that day a workers and soldiers council was formed in Stuttgart . As of November 5, its organ was the newspaper Die Rote Fahne .

While things remained calm in Stuttgart until November 9, there was a general strike in Friedrichshafen on November 5 and 6. A USPD spokesman called for an immediate ceasefire in front of an audience of 4,000. On November 5th, a workers 'and soldiers' council was also formed in Friedrichshafen. As a result of these events, the previous Württemberg government under the national liberal Prime Minister Karl von Weizsäcker resigned on November 6, 1918 to make way for a parliamentary government.

Order of the King

monument by Hermann-Christian Zimmerle in front of the Wilhelmspalais in Stuttgart

The new royal state ministry under the democratic-liberal Theodor Liesching ordered a constituent state assembly in the name of King Wilhelm II on November 9, 1918, which, after a general, equal, direct and secret election by all citizens of Württemberg who had reached the age of 24 should be chosen. The task of the assembly was to draw up a constitution on a democratic basis. In this way, the future form of government in Württemberg should be decided. In the order it is stated by the king, who had been very popular with the people, “... that his person will never be an obstacle to a development demanded by the majority of the people, as he has seen his only task in this until now To serve the well-being and the wishes of his people. ”This announcement, probably made under the impression of the revolution that broke out on November 7th in Munich , Braunschweig and other major German cities , was intended to prevent a revolution in Stuttgart. The order was already wasted on the day of its publication, because on this November 9th, under the impression of the news from Berlin that afternoon, the revolution also broke out in Stuttgart . The People's State of Württemberg was formed.

The revolution on November 9, 1918 in Stuttgart and its consequences

On the morning of November 9th, a large demonstration sponsored by the MSPD and USPD took place in Stuttgart . Among others, Wilhelm Keil (MSPD) spoke in the morning on the Schloßplatz in front of an audience of almost 100,000 and announced a “Social Republic”. The Spartakists were in a weakened position on November 9th, as their leaders Fritz Rück and August Thalheimer had been arrested in Ulm on the evening of November 6th while they were on their way from Stuttgart to Friedrichshafen. They were not released until late evening on November 9th.

In the morning some revolutionaries, against the will of the demonstration leadership, entered the king's residence, the Wilhelmspalais , and hoisted the red flag on the building in place of the royal house standard. An officer on watch who opposed the intruders was knocked down. According to contemporary witnesses, this remained the only act of violence in the otherwise bloodless demonstration in Stuttgart.

A provisional socialist Württemberg government made up of members of the MSPD and USPD was formed in the Württemberg state parliament on the afternoon of November 9, 1918, after it became known that Scheidemann had proclaimed the republic in Berlin . This formation of a government was the real revolutionary act in Württemberg. The king left his palace in the evening and was brought to Tübingen , to Bebenhausen Castle . The head of the provisional government was the majority Social Democrat Wilhelm Blos . The presiding representative of the USPD, Arthur Crispien , soon took a back seat to Blos. Two days later, an all-party government was formed from the provisional government with the admission of the bourgeois ministers Theodor Liesching ( democrat ) and Johannes Baptist von Kiene ( center ), who had belonged to the last government of the kingdom, as well as the national liberal deputy Julius Baumann .

After the events in Stuttgart became known, further local councils emerged, for example on November 9th in Heilbronn and Ludwigsburg and on November 11th in Ulm. In the workers 'and soldiers' councils, radical elements lost their influence early on, so there was neither a civil war-like situation in Württemberg nor a soviet republic. The majority of the Stuttgart workforce also supported the MSPD.

Consolidation of the provisional state government

On November 16, 1918, the head of cabinet of the royal government released all civil servants from their oath of service to the king on behalf of the king in a letter to the provisional government . The bureaucratic apparatus, which was not changed and thus ensured the continued existence of the administration, was an important pillar of the provisional government in the fight against the radical forces. The councils were limited to control functions which could not seriously disturb the administration. The government of Blos quickly enjoyed the trust of state officials, teachers and clergy. There was a saying that not much has changed in Württemberg: "In the past, only Wilhelm ruled, now Wilhelm Blos."

In an announcement to the people of Württemberg on November 30, 1918, King Wilhelm II voluntarily laid down the crown and thanked everyone who had served him and Württemberg loyally during his 27-year reign. With the abdication of the throne , he assumed the title of Duke of Württemberg.

The later Lord Mayor of Ulm, Theodor Pfizer , summed up the Württemberg revolution in the following words:

“The end of the monarchy brought a turning point, but not a deep break in the development of the country and its capital. The court, uniforms and medals disappeared, but the state apparatus and civil servants remained bound to their task even in the new regime ... The men of the new era like the Social Democrats Blos and Keil were not turned to extremes. Perhaps too little new space was given in the bloodless revolution, too much was taken over unchanged. But a profound change of heart was hardly necessary in Württemberg. The country's loyal, conservative citizens were, like the king, tolerant, politically liberal, like the father was, even when they voted for conservatives, and beneficially anointed with the often invoked democratic oil. One remained loyal to the Reich, even though one often cursed the Prussians and forgot that in Württemberg, behind the desks and counters, were South Prussians who meticulously carried out the laws that were devised in Berlin and laughed at in Bavaria. "

On December 8, 1918, the first state assembly of the Württemberg workers' councils was held, in which about 120 delegates took part. The regional committee formed there consisted mainly of members of the MSPD.

On December 11, 1918, the election regulations for the constituent Württemberg state assembly with the election date January 12, 1919 were enacted.

On December 28, 1918, a meeting of the four South German Prime Ministers Wilhelm Blos (Württemberg), Kurt Eisner (Bavaria), Anton Geiß (Baden) and Carl Ulrich (Hessen), all of whom belonged to the SPD and USPD, took place in Stuttgart. In their Stuttgart declaration, despite some reservations from Bavaria, they stated that the southern German states were holding onto the Reich.

First attempted coup by the Spartakists in January 1919

In the days before the election of the state constituent assembly, Wilhelm Blos, with the help of the security forces set up by Lieutenant Paul Hahn, put down an uprising of the Spartacists in Stuttgart inspired by the events in Berlin . The unrest lasted from January 4 to 12, 1919. However, the form and course did not come close to the severity of the acts of violence that were to be lamented in other parts of Germany. Nevertheless, there were dead and injured when firearms were used in Stuttgart. During these January riots, the government went to safety in the tower of the half-finished Stuttgart Central Station . As the USPD supported the uprising of the Spartacists, Arthur Crispien and Ulrich Fischer were dismissed from the government on January 10, 1919.

The National Constituent Assembly

On January 12, 1919, the election to the constituent assembly of the state was carried out without any incidents worth mentioning and brought victory to parliamentary democracy. The majority Socialists represented by Blos received 52 mandates, the Democrats and National Liberals together 38 and the Center 31 mandates. The three party groups of the so-called Weimar coalition , which supported the government, were thus able to unite four fifths of all MPs. The camp of opponents of the republic included the farmers 'union , the vineyard association and the citizens' party, consisting of the monarchist right with 25 seats and the radical left of the USPD with only four seats. 13 of the 150 members of the state assembly were women.

During this eventful time, the possibility of a unification of the states of Baden and Württemberg was discussed. On January 17, 1919, Theodor Heuss gave a lecture at a party event of the DDP in Stuttgart, where he proposed the unification of Baden and Württemberg. The lecture received wide press coverage. The topic was later discussed in the constitutional state assembly of Württemberg and by members of the Baden and Württemberg national assembly in Weimar. These talks did not lead to any practical result, but in the state's press, such as the Stuttgarter Neue Tagblatt or the Heilbronner Neckar-Zeitung, there were repeatedly reflections on a federalism reform that involved the dissolution of the overpowering Prussia and the Amalgamation of smaller German countries - especially Baden, Württemberg and the Hohenzollernsche Lande - to form larger ones .

On January 23, 1919, the constituent assembly elected on January 12 met for the first time. On January 29, 1919, she confirmed the previous provisional government in office and commissioned Blos as Prime Minister to continue exercising government business. On February 14, 1919, the Provisional Government was renamed State Government by a resolution of the Assembly . On March 7, 1919, the previous Prime Minister was elected President with 100 of 129 votes. Soon some bourgeois politicians in the state assembly demanded the dissolution of the councils in Württemberg, but initially without success. One of the first important laws was a new municipal code on March 15, 1919.

Second attempted coup by the Spartakists in April 1919

Since the king’s officials set the tone in the administration practically unchanged and there were no democratic reforms in this area, a disapproving mood grew among the population. As a result, the Spartakists won new supporters, but there was also increasing dissatisfaction among supporters of the MSPD. Then there was the assassination of the Bavarian Prime Minister Kurt Eisner (USPD), which acted as an additional signal for the Spartakists that something had to be done. The action committee of the united proletariat decided to call a general strike.

From March 31 to April 10, 1919, the Württemberg government violently fought this general strike in Stuttgart and the surrounding area by declaring a state of siege . About 400 Spartakists had holed up on the Wangener Höhe and Abelsberg and took the state road - today's Ulmer Strasse in Stuttgart - under fire. The government countered this with the use of guns. 16 people were killed in the fighting and around 50 were wounded. The Spartakists were rolled up by the Württemberg military and brought to court martial . An official combat report was issued. Clara Zetkin later criticized the government's brutal crackdown on the Spartacists at a session of the state constituent assembly.

The government not only restored peace and order in Württemberg, but also sent Württemberg troops in April 1919 to remove the Munich Soviet Republic to Bavaria , where they were deployed together with Prussian associations and the Freikorps operating there. The Württemberg SPD state chairman, Friedrich Fischer, was against sending Württemberg troops to Munich, but found no approval for his position in the government.

Adoption of the constitution of the People's State of Württemberg

The new Württemberg constitution was passed on April 26, 1919 and came into force on May 20, 1919. On April 28, 1919, Reich President Friedrich Ebert gave a speech in Stuttgart in which he expressed his commitment to federalism in the following words: “The unification of the Reich and the preservation of the tribal characteristics in our German districts are not mutually exclusive. They can very well be combined. ”Since the Württemberg constitution contradicted the constitution of the German Reich, which came into force on August 14, 1919, in some points, it had to be revised. The contradictions arose in particular from the elimination of the Württemberg reserve rights in the military as well as in the postal and railway operations (see section State structure and administration). Finally, the final constitution of Württemberg came into force on September 25, 1919, exactly one hundred years after the promulgation of the first constitution of Württemberg on September 25, 1819. With the entry into force of the constitution of the people's state, the workers 'and soldiers' councils that supported the revolution of 1918 were established , but had now lost their political importance, also formally canceled. On October 4, 1919, President Blos was sworn in on the new constitution of Württemberg.

Wilhelm Blos later wrote about the emergence of the people's state:

“On November 9, 1918, the wave of a mighty revolution carried me to the head of the new Württemberg government, where I stayed until June 23, 1920. After all relationships had dissolved, the task was to save the country from the threatening anarchy and dictatorship of a violent minority. A democratic republic was to be built on the ruins of an old monarchy, in which the people of Württemberg could determine their own future. Together with the workers 'and soldiers' councils, it was possible to overthrow the Spartacist coups of winter and spring. Likewise, the Bolshevik danger threatening from Munich was happily warded off by Württemberg. "

Political development in the early twenties

Stuttgart as a refuge for the Reich government during the Kapp Putsch

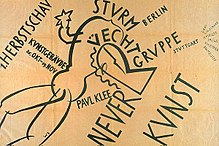

The relatively stable political conditions in Württemberg compared with other areas of the German Reich allowed the Blos government to host the Reich President Friedrich Ebert and the ministers of the Reich government in Stuttgart from March 15 to 20, 1920, and give them a safe place during the Kapp Putsch To provide residence. General Haas of the 5th Division of the Reichswehr in Stuttgart had agreed to support the Reich government and the Reichstag after the initially unsteady attitude. The commanding General Maercker in Dresden, where Ebert and the Reich government had initially fled, had not given this promise. On March 18, 1920, the German National Assembly met in the Stuttgart art building .

Formation of the Hieber minority government (Democrats and Center)

In the first regular state elections on June 6, 1920, the majority Social Democrats and the Democrats each suffered a significant defeat. Thereupon the state executive of the SPD decided not to belong to the new government, which Blos and Keil disagreed with, but ultimately bowed to the will of the party, which was also no longer represented in the new government . After his election, the democrat Johannes Hieber , who succeeded Wilhelm Blos as President of Württemberg, paid tribute to the services of the predecessor in overcoming the great problems after the lost World War .

From 1920 to 1924 the Democrats and the Center formed the Hieber cabinet . Actually, as the strongest party in the state parliament, the center would have been entitled to the office of state president. The center refrained from asserting this claim. This was justified by the fact that a Catholic state president did not yet appear reasonable to the majority of the Protestant population of Württemberg at this point in time. The Protestant candidate Hieber from the DDP was therefore given precedence. The Hieber cabinet temporarily became a minority government tolerated by the Social Democrats. Only from November 7, 1921 to June 2, 1923 was the Weimar coalition in Württemberg complete again, as the Social Democrat Wilhelm Keil was a member of the Hieber government as labor and nutrition minister. The reason for the SPD's entry into the Württemberg government was also that, with the Wirth cabinet , a Weimar coalition ruled again at the Reich level from May 1921.

Despite the relative political stability in Württemberg, this government had to do with the enormous problems of post-war inflation and the hyperinflation triggered by the war in the Ruhr in 1923 . When in the summer of 1920 Communist-influenced workers in the factories of Daimler , Bosch and the Esslingen machine factory demonstrated against the newly introduced wage tax deduction, the Württemberg government had these factories occupied by police on the morning of August 26, 1920. The radical workers' councils responded by calling for a general strike. The police, led by the tried and tested Red Rooster , loyal to the government , were able to put down the general strike within 14 days , supported by many volunteers (especially students led by Eberhard Wildermuth ). During this crisis, the government holed up again in the tower of the new Stuttgart main station.

Years under the influence of political assassinations

In August 1921, the murder of the Württemberg center politician Matthias Erzberger shook the public. On June 9, 1922, Chancellor Joseph Wirth and Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau , the negotiator of the Rapallo Treaty , came to Stuttgart. Rathenau gave a speech to invited guests of the Württemberg Society and met with the Württemberg government for talks. Two weeks later, news of his murder came out. The Deutschvölkische Schutz- und Trutzbund was associated with the assassination and banned in 1922 on the basis of the Republic Protection Act in most of the German states, but not in Württemberg. The fact that no bans against ethnic and anti-republican organizations were imposed in Württemberg can be attributed, among other things, to the fact that the state police office recorded only a small number of followers in its reports for these associations in Württemberg and came to the judgment that they should be regarded as consistently harmless. In addition, for legal reasons, the State Ministry refused to intervene against the right-wing extremist associations that were banned in other countries. The Minister of the Interior only issued a decree of September 13, 1922, in which the higher offices were requested to pay special attention to the NSDAP, the Association of Nationally Minded Soldiers and the Schutz- und Trutzbund.

Despite some activities in Württemberg in the twenties, the Völkisch and the National Socialists were not granted any major success, which was not changed by Hitler's eleven visits to Stuttgart from 1920 to 1932. During the Hitler putsch in Munich in November 1923, the population of Württemberg was generally calm.

The SPD leaves the government in May 1923

In October 1922, the SPD gained strength in the Württemberg state parliament through reunification with parts of the USPD. The greater political weight encouraged the Social Democrats to lay claim to the appointment of an SPD minister to the interior ministry that had become vacant when the center minister Eugen Graf died in May 1923. This was rejected by the center, which is why the SPD returned to the opposition. During her participation in government she had also failed to achieve her main goals in the area of social policy. For example, the eight-hour working day could not be generally enforced, an expansion of the trade and industry supervision was not possible, and a tax reform to upgrade communities with high industrialization was prevented by the coalition partners. The introduction of the generally binding eighth school year had also not been achieved.

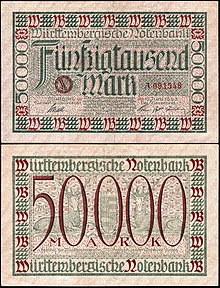

The hyperinflation

The hyperinflation of 1923 , which destroyed financial assets and devalued current wages, lasted until the currency reform, which took place in November 1923 with the introduction of the Rentenmark . While the big entrepreneurs and landowners were mostly able to capitalize on the hyperinflation, the thrifty urban petty bourgeoisie and the working population became impoverished in the course of 1923. In Württemberg, the crisis was milder as many residents, in addition to their work as employees, still had connections to the Had agriculture, partly as part-time farmers and partly through family ties. Full-time farmers were significantly less affected by the crisis. In addition, the Württemberg economy was generally more medium-sized, less centralized in large cities and, due to vehicle construction and electrical engineering, more export-oriented than elsewhere in the empire.

The failure of the government Hieber

The minority government in Stuttgart failed in the spring of 1924 not because of opposition from the tolerant SPD or because of the huge domestic, foreign or economic policy issues, but rather because of an attempt at administrative reform. In order to be more economical in the public budgets after the end of the inflation, the administrative structure of Württemberg from the beginning of the 19th century should be significantly leaner. However, since the state parliament refused to give its consent including the center involved in the government and only succeeded in abolishing the four district governments, the DDP withdrew its ministers from the government. One month before the elections in April 1924, the Hieber government gave way to the Rau interim government . One of the most important achievements of the failed government was the separation of the church from the state in the church law of March 1924, which also ended the centuries-old integration of the Protestant church with the Württemberg state. A comprehensive district reform was carried out in 1938 under the National Socialist dictatorship.

Between inflation and the global economic crisis

The state election campaign in 1924

In the state election campaign of 1924, which was still under the shock of the inflation events of the previous year, the citizens 'party (the Württemberg DNVP ) and the farmers' union cleverly used the failed plan of the Hieber government to dissolve the seven smallest higher offices and the Hall district court for propaganda purposes . With the help of a mass of leaflets, the topic was presented in a populist way, as if the old government wanted to destroy living organisms by dissolving higher offices. The election campaign of these conservative parties was directed in sharp words against democracy and made use of both the stab in the back and anti-Semitic slogans. The state election on May 4, 1924 led to a clear shift to the right. The parliamentary group of the Citizens' Party with the Farmers and Vineyards Association was the strongest parliamentary group in the state parliament , and they managed to win the center over to join a coalition government. The time of the Weimar coalition in Württemberg was over. The SPD always remained in opposition, in particular the deputy to Kurt Schumacher excelled, who was from 1924 to 1931 the Diet.

Conservative coalition with the center

On June 3, 1924, the DNVP politician Wilhelm Bazille was elected as the new Württemberg state president. Bazille, a conservative anti-democrat and monarchist, had until then led the opposition in the state parliament and, in addition to the state ministry, also took over the management of the cultural and economic departments. Bazille ruled until 1930 in a coalition of the Württemberg Citizens' Party (the regional DNVP offshoot), which was stable for the time, with the also Protestant Württemberg Farmers and Vineyards Association and the Catholic Center Party . The collaboration between Catholics ("blacks") and Protestant conservatives ("Prussian blue") - sometimes referred to in literature as the "black-blue" coalition - began in Württemberg in 1906 and is considered to pave the way for the later establishment a non-denominational Christian Democratic party - the CDU .

Much to the astonishment of many contemporaries, the former demagogue Bazille turned into a statesman with dignity and prudence in the state offices, although his thoughts and actions were still shaped by the fear of the Bolshevik revolution. The time of the Bazille government falls into the era of the so-called Roaring Twenties .

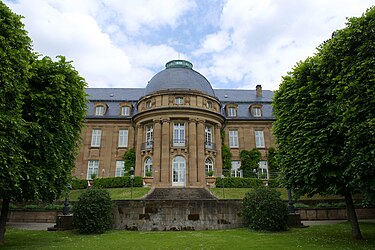

With the death of President Ebert and the election of Hindenburg as the new Reich President, there was an overall shift in political weight to the right in Germany. On November 11, 1925, the new Reich President made a state visit to Württemberg and was received by Lord Mayor Karl Lautenschlager in the Stuttgart City Hall and by President Bazille in Villa Reitzenstein .

The Villa Reitzenstein was the new headquarters of the Württemberg State Ministry after Bazille had arranged the move from the previous location in Stuttgart's Königstrasse to the new address on Gänsheide. The amalgamation of the state parliament, ministries and central authorities in one government district was discussed but rejected as impracticable. Further plans of the government to record the historically grown and sometimes difficult to survey legal regulations of Württemberg in a code and to simplify the structure of the state did not lead to any visible results. Only the Oberamt Weinsberg was dissolved during this time.

In matters of foreign policy, the government in the Reichsrat showed a fluctuating picture. In August 1924, under pressure from the center, Württemberg voted for the Dawes Plan , although the DNVP was strictly against it. However , Württemberg was unable to find a unified position on the results of the Locarno Conference in autumn 1925 because Bazille considered the Locarno Treaty to be acceptable, but his cabinet colleague and party friend Alfred Dehlinger, in line with the DNVP position, rejected it. With regard to economic policy, Bazille was able to emphasize in the state parliament at the end of 1927 that Württemberg had the lowest unemployment in the German Reich . In the question of the relationship between the states and the Reich, which was open during the entire period of the Weimar Republic, Bazille took a position aimed at maintaining the independence of the states and saw himself as the guardian of the interests of Württemberg. Bazille was the main target of the opposition parties in the election campaign for the Reichstag and state elections on May 20, 1928. Communists, social democrats and liberals strongly criticized the fact that Bazille, as minister of culture , had prevented the introduction of an eighth year of primary school. The SPD politician Fritz Ulrich described the "regime of the French-born Bazille" as alien to the Swabians.

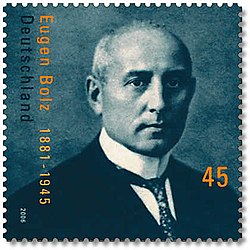

The formation of the Bolz government

The state elections of May 20, 1928 brought the Conservatives a heavy defeat, while the center was able to maintain its number of seats. The absolute majority of the previous coalition was lost. Since the center, under the leadership of Eugen Bolz , did not want a new edition of the Weimar coalition with the SPD, which was deemed incapable of government , and the DDP refused to join the government with the DNVP, the Bolz minority government was formed. The keeping of the SPD away from the Württemberg government by the politicians of the center and the conservative parties can be explained under the following aspect. The SPD, which has been the strongest political force in the state parliament since the new elections, should not be able to assert its relatively heavy weight as a ruling party. The politically fragmented bourgeois-conservative camp in Württemberg wanted to prevent this at all costs, while at the Reich level the Müller cabinet came into being under the leadership of the SPD. A specific reproach made by the governing parties to the SPD in Württemberg was that the SPD had no state political program and that it was far too “Unitarian” thinking only of its politics at the Reich level. A particularly weighty argument in favor of maintaining the coalition of the center, the citizens 'party and the farmers' union was the adherence to the denominational elementary schools in Württemberg. The SPD wanted to introduce mixed denominational elementary schools, so-called simultaneous schools.

In the state parliament session on June 8, 1928, Eugen Bolz was elected as the new President of the State with 39 of 80 votes based on the current rules of procedure. The SPD sued the State Court of Justice against this, whereby it was to be established that the Bolz Ministry and in particular the Minister Bazille had come into office unconstitutionally. Another charge against the SPD was the rules of procedure used in the state parliament, which rated abstentions in the case of no-confidence votes as a “no”, which, in the SPD's view, also violated the state constitution. It was not until February 18, 1930 that the State Court decided to reject the SPD's complaints. At that time, however, these were already politically outdated, because in January 1930, with the entry of Reinhold Maier from the DDP as the new Minister of Economics and State Councilor Johannes Rath from the DVP, a stable parliamentary majority in the Bolz government was established. This entry into the government was connected with the planned approval of the Württemberg government for the Young Plan in the Reichsrat. Since the DNVP under Alfred Hugenberg was strictly against approving the Young Plan, there was a risk that the Württemberg government would not have a quorum. By January 1930, the government had only four ministers: Bolz and Beyerle from the Center and Bazille and Delinger from the DNVP. Bazille in particular came increasingly into conflict with his party's Hugenberg line on this issue. The plebiscite against the Young Plan , which the right-wing extremist parties started in the summer of 1929, led to a referendum that was held on December 22, 1929. In Württemberg, only 11.6% of voters spoke out in favor of rejecting the Young Plan. The Reich average for this rejection was 13.5%. This paved the way for the Bolz government to give its approval in the Reichsrat. After Reinhold Maier joined the Württemberg government, the Young Plan was approved in quick succession. The representatives of the anti-republican parties (NSDAP, DNVP, KPD) called the behavior of the Bolz government treacherous towards the German people, as they had been exposed to the capitalist exploitation of foreign tributaries for decades. In the opinion of these opponents, the Württemberg government should not have bowed to the will of the Reich government.

An important topic for the Württemberg government was the question of imperial reform , which was pending throughout the years of the Weimar Republic , with which federalism in the German Reich was to be placed on a more homogeneous and thus healthier basis. The political weight of Württemberg in the Reichsrat and thus its influence on Reich politics was small. The Prussian state, on the other hand, had an overwhelming status, and the office of the Prussian Prime Minister was comparable to that of the Reich Chancellor. In order to strengthen the influence of the south-west German states, the Württemberg cabinet discussed the question of a merger between Württemberg and Baden on February 10, 1930 . Despite considerable reservations on the part of the two DNVP members, the ministers agreed that Württemberg would have been ready to merge the states. The result of this government decision was made public during the budget consultation in the Württemberg state parliament. Since President Bolz imagined the greater advantages of such a merger in Baden, he expected an initiative from Karlsruhe , but this did not happen.

In Württemberg, too, the SPD dealt intensively with the question of whether the SPD Reich ministers should have approved the budget for the construction of new armored cruisers . Kurt Schumacher was a staunch opponent of the new armored cruisers and was thus in line with the party base, while Wilhelm Keil and the SPD state chairman Erich Roßmann expressed understanding for the attitude of the Reich government. Kurt Schumacher always criticized the republic's inadequate clout and advocated that the Reichswehr must first be won over to the ideas of the republic before any thought could be given to rearmament. Schumacher saw the republic threatened by both National Socialism and Communism . On March 25, 1930, the last Chancellor of Weimar to stand up for democracy, Hermann Müller , spoke on the 10th anniversary of the failed Kapp Putsch in the Stuttgart Liederhalle, which led to a social democratic mass meeting. Two days later, Müller resigned from his office because the SPD parliamentary group did not approve a coalition compromise on unemployment insurance. This marked the end of the Müller II cabinet , the last parliamentary government of the Weimar Republic.

The last years of the People's State of Württemberg

Country of stable conditions at the beginning of the global economic crisis

When Eugen Bolz took office as President of the State on June 8, 1928, he had been Württemberg Minister without interruption from July 24, 1919, first as Minister of Justice until June 2, 1923 and then as Minister of the Interior, which he continued until March 11, 1933 stayed. As Minister of the Interior, Bolz had made the Württemberg police responsible for the state, as they had previously been subordinate to the municipal authorities following an old tradition. With the help of his police, Bolz tried to keep state life in Württemberg stable. Bolz believed he had to see the main opponents of the order to the left of the political center. The right-wing parties and groups he apparently saw a lower risk, and that, as the erosion of parliamentary relations in the Kingdom during 1930 even after the global economic crisis was already in full swing.

The SPD took offense at the Wuerttemberg police leadership, which was German-national and applied the emergency decrees of the Reich President of March 31, 1931 to combat political riots unilaterally restrictive against the left-wing parties SPD and KPD and acted much too mildly in the obvious offenses of the NSDAP. In autumn 1931, the SPD parliamentary group set up a committee of inquiry into the political orientation of the Stuttgart police leadership. On January 5, 1932, the police confiscated the issue of the SPD party newspaper Schwäbische Tagwacht , because the Reich Court's slow investigations against the author of the Boxheim documents , Werner Best , were criticized there. The Stuttgart police leadership justified the confiscation of the Tagwacht edition with the fact that the Reichsgericht had been made "maliciously insulted and contemptible". Wilhelm Keil emphasized in a speech in the state parliament on February 16, 1932 that the article in the Swabian Tagwacht had been a completely justified criticism of the Reichsgericht and criticized the fact that stricter censorship was applied than during the First World War.

Another example of the politically one-sided approach of the Stuttgart police leadership was the arrest of the police leader of the Württemberg KPD, Josef Schlaffer , on November 8, 1931. On November 7, 1931, the KPD held a ceremony to commemorate the Russian in the Stuttgart city hall October Revolution held and, according to the regulations, no political speeches, but only a sporting and artistic program that ended with the singing of the International . Only then did Josef Schlaffer give a short closing remarks, which gave rise to his arrest and sentencing to three months imprisonment in an express trial. Kurt Schumacher then criticized the Stuttgart Police President for violating Schlaffer's immunity as a member of the Reichstag.

In addition to his controversial police regime, Bolz also ensured a well-founded policy in the area of social services, infrastructure development and energy supply, which contributed to the stability of the Württemberg state during the global economic crisis.

The American journalist Hubert R. Knickerbocker was impressed during his trip through Germany at the height of the global economic crisis that there was “no external sign of depression to be seen” in Württemberg's capital. The "city shining in its glow of lights" and "its new public and private buildings speak more clearly of prosperity". Knickerbocker also said, "In the streets of Stuttgart you can see more well-dressed people than in any other" German city he knows.

The state parliament is unable to act

On April 24, 1932 the election for the new Landtag took place, from which the NSDAP emerged as the strongest parliamentary group with 23 seats. The National Socialist Christian Mergenthaler became the new President of the State Parliament . None of the eight candidates for the office of President received the absolute majority required. Jonathan Schmid from the NSDAP received 22 and Eugen Bolz only 20 votes. The new state parliament with an absolute majority of the opponents of the Weimar Republic, which include the NSDAP and KPD as well as the DNVP (citizens' party) and the WBWB, was unable to act. There were constant noisy heckling and tumultuous scenes between the members of the NSDAP and the KPD . There could be no doubt that these parties did not value a functioning parliament. Since a new president was not elected, the Bolz government remained in office and, following the example of the Brüning government , switched to governing with emergency ordinances , largely excluding the state parliament.

In June 1932 Bolz and his counterparts Josef Schmitt from Baden and Heinrich Held from Bavaria tried in vain to persuade Reich President Paul von Hindenburg to prevent the so-called Prussian strike, as this would lead to a tremendous weakening of federalism and apart from that constituted a breach of the constitution. Three days after the Prussian strike, on July 23, 1932, Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen met with the Prime Ministers of the southern German states in the Reitzenstein villa to discuss how a dictatorship by Hitler could be prevented and to assure that the southern German states would remain intact should stay. This Stuttgart meeting remained ineffective overall.

The way to dictatorship

After Adolf Hitler became Chancellor on January 30, 1933, the decline of statehood in the German states began. The attempt to hold back developments in Berlin with the help of a general strike in Mössingen remained a courageous individual action in the Württemberg province. The Reichstag was dissolved and new elections were scheduled for March 5th. The election campaign was accompanied by street terror on the part of the NSDAP. On February 4, 1933, the imperial government's emergency decree restricted freedom of the press and assembly. On February 15, 1933, Hitler gave a speech in Stuttgart. Opponents of the National Socialists succeeded in interrupting the radio broadcast by cutting a transmission cable .

In the 1933 Reichstag election , the NSDAP in Württemberg only achieved 41.9% of the vote and thus remained slightly below the 44% at the Reich level, but this no longer played a role. The Bolz minority government came under increasing pressure. On March 8th, the Reich government appointed Dietrich von Jagow as Reich Commissioner for Württemberg. As a result, many members of the opposition were arrested and taken to the Heuberg concentration camp near Stetten on the cold market .

With the votes of the Württemberg Citizens' Party and the Württemberg Farmers and Vineyards Association, the Württemberg Gauleiter of the NSDAP, Wilhelm Murr , was elected as the new state president in the state parliament on March 15, 1933. Thirty-six MPs voted for Murr, the Center and the DDP abstained with 19 votes, while the 13 SPD MPs voted against. The communists had already been expelled from the state parliament.

The Enabling Act of March 24th and the Act on bringing the Länder into line with the Reich of March 31st led to the factual insignificance of the Länder. The Württemberg state parliament was reorganized according to the result of the Reichstag election on March 5. The offices of Reichsstatthalter were created by the second law for the conformity of the federal states of April 7, 1933 . The previous President Wilhelm Murr became Reich Governor for Württemberg. In this position he was superordinate to the new state government under the Prime Minister, Christian Mergenthaler, and was only responsible to the Reich Chancellor. The last session of the Württemberg state parliament took place on June 8, 1933. The Enabling Act passed here suspended the Württemberg constitution of 1919 and transferred the legislation to the state government. The Reich Law of January 30, 1934 repealed all German state parliaments and transferred the sovereign rights of the states to the Reich. Like the other state governments, the Württemberg state ministry had thus become a central authority of the Reich. The planned conversion of Württemberg into a Reichsgau was not carried out.

The dictatorship and its consequences

History of Württemberg from 1933 to 1945

Main article: Württemberg at the time of National Socialism

The Nazi rule in Württemberg was shaped until 1945 by the permanent dualism of the Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalters Murr and the Prime Minister Mergenthaler, who was formally subordinate to him. Both officials mistrusted each other in principle, but Hitler never lifted this dualism despite repeated attempts on the part of Wilhelm Murr. After the seizure of power, Hitler very rarely came to Württemberg. At the height of his popularity, shortly after the annexation of Austria to the now Greater German Reich , the Führer and Imperial Chancellor paid the Stuttgarters a long-awaited visit. On April 1, 1938, he drove to great joy in an open car from the main train station via Königstrasse to the town hall, where he was received by Mayor Karl Strölin and Reichsstatthalter Murr. In the evening he gave a speech in the town hall.

As in the rest of the Reich , Jews were persecuted and murdered, the opposition was eliminated, the administration was brought into line and the administration emigrated. The ranks of particularly notorious Nazi criminals from Württemberg included, for example, the head of the special court in Stuttgart, Hermann Cuhorst , the SS-Obergruppenführer Gottlob Berger , the SS brigade leader Walter Stahlecker and the NS district leader of Heilbronn, Richard Drauz . Resistance fighters from Württemberg were, for example, Georg Elser , the siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl , the brothers Berthold and Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg , Fritz Elsas and Eugen Bolz . Active resistance against National Socialism remained the exception in Württemberg - as in the Reich as a whole.

During the Second World War , the native of Württemberg Field Marshal acquired Erwin Rommel high reputation. In the bombing war that began in 1943, the cities and towns of Württemberg suffered from increased bombing. Stuttgart had a total of 4,562 dead in 53 air raids , Heilbronn, which was destroyed on December 4, 1944 , around 6,500 dead. The cities of Ulm , Reutlingen and Friedrichshafen also suffered particularly severe damage . During the ground fighting in the course of the capture of Württemberg by American and French troops in 1945, the cities of Crailsheim , Waldenburg and Freudenstadt were almost completely destroyed.

Post-war history 1945 to 1952

Main articles: Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern

After the Second World War, the northern part of Württemberg became part of the American zone , the southern part of the French zone . The southern border of the American occupation zone was chosen in such a way that the Karlsruhe-Munich motorway, today's A 8 , lay within the American occupation zone for the entire route. The boundaries were the respective district boundaries. The military governments of the zones of occupation founded the states of Württemberg-Baden in the American zone and Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern in the French zone in 1945/46 . These countries were in the wake of the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany on 23 May 1949 to countries of the Federal Republic.

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany enabled measures to reorganize the three countries through Article 118. In the course of this, on April 25, 1952, the states of Württemberg-Baden, Baden (that is, southern Baden) and Württemberg-Hohenzollern merged to form the state of Baden-Württemberg. Further details on this topic and the further history are listed under Baden-Württemberg .

State building and administration

The constitution of the free people's state of Württemberg

The draft constitution came from the Tübingen professor Wilhelm von Blume (lawyer) . The constitution of the People's State of Württemberg, which came into force on September 25, 1919, was that of a parliamentary republic. This constitution was de facto overridden by the synchronization laws of the German Reich of March 31, 1933 and April 7, 1933, as well as the Reich law on the rebuilding of the Reich of January 30, 1934. The constitution was divided into 9 sections with a total of 67 paragraphs.

Section 1 of the first section of the constitution laid down the form of government as that of a free people's state within the German Reich. The formulation of a free people's state meant the form of a democratic republic without these words themselves being used in the entire constitutional text. In § 2 the national territory was determined which corresponded to that of the Kingdom of Württemberg .

The second section of the constitution described state authority in three paragraphs. According to § 3, all state authority emanated from the people. New features in the constitution were the proportional representation system, the now common right to vote for women throughout Germany and the lowering of the minimum age for participation in elections to 20 years. The procedure for referendums was laid down in Section 5.

The third section regulated in 20 paragraphs the formation and the tasks of the state parliament, which consists of only one chamber, as legislator and control body of the state government. Section 11 provided for a legislative period of four years. Noteworthy is the right mentioned in § 16 that the state parliament could be dissolved prematurely by referendum, which, however, never happened in practice.

The fourth section dealt in 15 paragraphs with the state management and the state authorities of the country. In accordance with Section 27, the state parliament elected the Prime Minister with the official title of State President. The Württemberg state president appointed and dismissed the ministers who together with him formed the Württemberg government and thus the executive. Pursuant to Section 28, the Landtag had the opportunity to express its mistrust in the government and thus to recall the government or to demand the dismissal of individual ministers. The President had no authority to issue guidelines. The government took its decisions in accordance with Section 31 by voting in the College of Ministers.

The fifth section of the constitution regulated the legislation in seven paragraphs and stipulated in which cases a referendum was planned. The sixth section described finance in eight paragraphs. The seventh section comprised three paragraphs, which regulated the competences of the State Court. In the eighth section three paragraphs were provided for the state control of economic life, and in the ninth section six paragraphs contained so-called “final and transitional provisions”.

Loss of Württemberg reservation rights to the Reich

The constitution of the Weimar Republic transferred some important sovereign rights that were still held by the southern German states to the Reich. For Württemberg this meant the loss of its own railway , which came to the Deutsche Reichsbahn in 1920 with a route length of 2173 kilometers , the loss of its own postal administration to the Deutsche Reichspost and the transfer of the Württemberg army to the Reichswehr , so that the Württemberg War Ministry from June 1919 could be resolved. In the Reichswehr, the 5th Division made up military district V with soldiers from Württemberg, Baden, Hesse and Thuringia . A state commander represented the military interests of Württemberg. In addition, the empire now administered the customs duties and VAT itself and set up the necessary authorities for them. The employment agency was also taken over by the Reich in 1927.

Tasks that remained with the state were carried out by the ministries of the interior, justice, economy and culture. The Ministry of Finance succeeded in keeping the Württemberg state budget in order despite all the crises. However, the relationship to the Reich remained an unsolved question in constitutional reality.

Judicial system

In addition to the Stuttgart Higher Regional Court , there were eight regional courts and a local court in each higher office . The administrative court in Stuttgart was responsible for administrative jurisdiction , also known as extraordinary jurisdiction, since 1876 in Württemberg.

administration

The People's State of Württemberg was divided into the city district of Stuttgart and 61 (1920: 63) regional offices with a total of 1,875 communities . Until April 1, 1924, Württemberg was still divided into the four districts of the Donaukreis ( Ulm ), Neckarkreis ( Ludwigsburg ), Jagstkreis ( Ellwangen ) and Black Forest ( Reutlingen ). In 1938, the 61 upper offices that still existed and the Stuttgart city directorate were merged into 34 rural districts and three urban districts. A detailed description can be found under administrative structure of Württemberg .

National emblem

The constitution passed in 1919 initially made no changes to the country's coat of arms and flag. In § 41 (3) it only stipulated that state colors and state coats of arms were to be determined by law. The national coat of arms, valid since 1817, as well as the black and red national colors remained in use for the time being. The law provided for in the constitution was passed by the state parliament on December 20, 1921 and came into force on February 20, 1922. Black and red were retained as the national colors, while the coat of arms changed. It was now square, whereby fields 1 and 4 were gold with three black stag poles lying down, fields 2 and 3, however, divided three times by black and red. Two golden stags acted as shield holders, and instead of the previously usual royal insignia, the coat of arms was replaced by a people's crown inflated. In 1933, after the National Socialists came to power, the style of the coat of arms was changed.

See also: coat of arms of Württemberg

Parties

The spectrum of parties was diverse, but only three of the important parties were firmly rooted in the Weimar constitution: the SPD , the left-liberal democrats and the left wing of the center .

The social democracy

During the years of the Weimar Republic, the SPD was in political competition with the KPD, which seriously weakened its strongholds in many parts of the German Reich. In Württemberg, regions with a high proportion of industrial workers were to be found, especially in Stuttgart and along the cities on the Heilbronn – Stuttgart – Ulm railway line. In Stuttgart, the proportion of SPD and KPD voters was at times almost equal at 15 to 20% each. Apart from Stuttgart, there was no industrial proletariat worth mentioning in Württemberg in the classic sense. Most of the SPD voters were artisans or workers who were often small farmers as part-time jobs. Heilbronn was a special stronghold for the SPD. Up to the beginning of the 1930s, the SPD's share of the vote there was up to 40%, while the KPD hardly achieved any results worth mentioning. In rural regions with a lack of social democratic milieu, the SPD found it difficult to mobilize voters. There the farmers' union dominated in the Protestant higher offices and the Center Party in the Catholic ones. In the field of education policy, two major goals of the Württemberg SPD remained unattainable. On the one hand, these were the overcoming of the traditional separation into denominational elementary schools in favor of standardized schools. These elementary schools, also known as simultaneous schools, for all denominations had been the norm in the neighboring state of Baden since 1876. On the other hand, the SPD wanted to increase compulsory schooling in Württemberg from seven to eight years, but this was blocked by the conservative Minister of Culture Bazille during his entire term in office from 1924 to 1933.

The SPD owned a dense network of 12 daily newspapers in Württemberg. The leading newspaper by a clear margin was the Swabian Tagwacht published in Stuttgart and its headers Neckarpost in Ludwigsburg, Volkszeitung in Esslingen, Freie Volkszeitung in Göppingen, Schwarzwälder Volkswacht in Schramberg and Freie Presse in Reutlingen. In Heilbronn the party paper Neckar-Echo appeared , in Schwenningen the Volksstimme and its head page, the Tuttlinger Volkszeitung . The Donauwacht appeared in Ulm with the headers Heidenheimer Volkszeitung and Geislinger Allgemeine Anzeiger .

The state chairmen of the Württemberg SPD were Friedrich Fischer (1913–1920), Otto Steinmayer (1920–1924) and Erich Roßmann (1924–1933). However, the two leading parliamentarians Wilhelm Keil and Kurt Schumacher clearly towered over them. Under the pressure of National Socialism, the Württemberg state executive committee of the SPD dissolved itself on May 10, 1933. With the law against the formation of new parties , the SPD had been banned in the entire German Reich since July 14, 1933.

Liberalism

Left-wing liberalism had a long tradition in Württemberg in the form of the Württemberg People's Party , which had existed since 1864, but which could only remain a people 's party as long as socialist or denominational client parties did not bind the voters to themselves. The People's Party, which is so attractive for ordinary people, came under increasing pressure from the nineteen-nineties onwards from the SPD, Zentrum and Bauernbund parties, which were now also organizing in Württemberg. Although left-wing liberalism was once again strengthened in Württemberg after the November Revolution of 1918, when many former National Liberals converted from the German Party to the newly formed German Democratic Party , the DDP also lost more and more rural voters in the Swabian homeland from 1919 to 1933, so that from the beginning 25% in the end only 2% of the voters remained in the DDP. This remainder of the electorate was mainly part of the urban upper class. The DDP in Württemberg was involved in the government from 1918 to 1924, and since 1920 with the Hieber cabinet even at the top of the government. From 1924 to 1930, the DDP, together with the SPD, was in sharp opposition to the black-blue coalition of the center and conservatives, before it decided in 1930, together with the DVP, to participate again in the conservative government. Reinhold Maier's entry into the Bolz cabinet prompted the nestor of Württemberg liberalism, Friedrich von Payer , to leave the DDP in protest against this rightward swing. The state chairmen of the Württemberg DDP were Conrad Haußmann (1918–1921) and Peter Bruckmann (1921–1933). On June 28, 1933, the party disbanded.

In 1918 the National Liberals from the former German Party were divided between the newly formed DDP and the Württemberg Citizens' Party, as it initially became apparent that the liberal split could be overcome. With the new German People's Party , however, a weakened successor organization emerged for the national liberal voters. The DVP initially rejected the republic, but with Gustav Stresemann, for reasons of common sense, it was willing to cooperate constructively in the new form of government. The state chairmen of the Württemberg DVP were Gottlob Egelhaaf (1919–1920), Theodor Bickes (1920–1927) and Johannes Rath (1927–1933). The organizational strength and the electoral successes of the DVP in Württemberg were comparatively low. On July 4, 1933, the party disbanded.

Political Catholicism

The center had only existed in Württemberg since 1895. The reason for its late founding was that the Catholics in the Kingdom of Württemberg, unlike in the neighboring state of Baden or in Prussia, were not exposed to any disadvantages. The long-time royal prime minister Hermann von Mittnacht was himself a Catholic, and a culture war could not arise. The political Catholic party was strongly represented in the almost homogeneous Catholic areas of Neuwuerttemberg . In the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, a sizeable Catholic community had developed in Stuttgart due to immigration, but it was still part of the diaspora there.

Since only about 30% of the residents in Württemberg were Catholic, the center could not become a political force comparable to that in the neighboring state of Baden, where the proportion of Catholics was almost 60%. During the Weimar Republic, the Weimar coalition was able to last until 1932 in Baden because the comparatively strong center there was able to accept the SPD as a junior partner. In Württemberg, the SPD was in the opposition from 1923 onwards, with almost the same political strength as in Baden, because the weaker bourgeois parties (the center, the citizens 'party and the evangelical farmers' union) were not prepared to accept the SPD's influence in a Württemberg government. The center in Württemberg was therefore more conservative than in other German countries. State chairmen of the Württemberg center were nominally Alfred Rembold (1895-1919) and Josef Beyerle (1919-1933). The real leading figures of the Württemberg center were Adolf Gröber , Johann Baptist Kiene , Matthias Erzberger , Eugen Bolz and Lorenz Bock . On July 5, 1933, the center dissolved under the pressure of National Socialism.

The conservatives

The conservative parties were opponents of what they saw as the “half-baked emergency building in Weimar”. These anti-republic parties included the Württemberg Citizens' Party as a regional association of the DNVP and the Bauernbund , which had appeared in Württemberg as an independent political party since 1895 and was an exception compared to the other countries. Although there were farmers 'associations in all German states that were organized in the Reichslandbund and were mostly politically close to the DNVP, only in Württemberg was the farmers' association an independent political party. When the urban citizens 'party and the rural farmers' union were involved as conservative elements in the Württemberg government from 1924 to 1933, the paradoxical situation arose that the parent party DNVP steered an extremely anti-republican course at the level of the Reich, but in Württemberg it did so in a certain way because of its government responsibility Became part of the Weimar system. On March 18, 1933, under the impression of the rule of National Socialism, the Württemberg farmers' union deleted the claim to be a political party from its statutes. On June 27, 1933, the German National Front , as the DNVP was last called, dissolved.

Bourgeois splinter parties

After 1928 the party landscape was split up because many voters increasingly wanted their own interests to be served. Württemberg pietists gave the CSVD their vote, and in Reichstag elections the Economic Party and the People's Rights Party could also unite votes.

The extreme left

The extreme left rejected parliamentary democracy on ideological grounds. She envisioned a state modeled on the Soviet Union . This made them appear very threatening in the eyes of the bourgeois and conservative classes. The extreme left was initially represented by the USPD , whose protagonists in Württemberg had already renounced the majority Social Democrats in 1915. From the beginning of the twenties, it was the KPD that advocated extreme left-wing politics in Germany. The Süddeutsche Arbeiterzeitung , published in Stuttgart, functioned as the organ of the KPD in Württemberg .

From 1919 to 1920 Edwin Hoernle was the head of the Württemberg party organization of the KPD . In 1924 the political head of the KPD in Württemberg, Johannes Stetter , was ousted. When Stetter published "Revelations about the KP swamp" after being expelled from the party in 1926, the KPD in Württemberg shrank considerably in terms of personnel and organization. In 1929 the so-called Brandler-Thalheimer faction was excluded from the KPD by the “ultra-left” turn of the KPD at the Reich level. The Communist Party Opposition (KPO) emerged as a right-wing split, which in Württemberg published the daily workers' tribune. Among the members of the KPO was, for example, Willi Bleicher . At the beginning of 1932 Walter Ulbricht came to Stuttgart to take care of the removal of the Württemberg KPD leadership duo Schlaffer and Schneck. The two had dared to attack the NSDAP in the political dispute instead of, as desired in Berlin and following the doctrine of the social fascism thesis, seeing the SPD as the main enemy. The division of the workers' movement into the anti-republic KPD and the state-sponsoring SPD also made itself felt in the development of the Stuttgart forest homes, which were badly affected by the conflict. Since March 8, 1933, the Nazi Reich Commissioner Dietrich von Jagow had massively persecuted and interned KPD members in Württemberg .

The extreme right

The National Socialism in Württemberg had it despite local strongholds such as in Nagold to choose hard for a long time because the Bauernbund stronger than in other German states held as a political force to be 68% Protestant population of them, Hitler's party. After the NSDAP was banned , the Völkisch-Soziale Block took a corresponding position in the Württemberg state parliament from 1924 to 1928 with three mandates.

Although the re-admitted NSDAP initially failed in the state elections in 1928, Christian Mergenthaler succeeded in June 1929 in getting a mandate through a judgment of the State Court in Stuttgart. The state elections in the spring of 1932 then led to the landslide-like success of the radicals, which gave the NSDAP 23 seats and thus also heralded the beginning of the end of democracy in Württemberg.

elections

Elections and the resulting election campaigns dominated everyday political life in the Weimar Republic. From 1918 to 1933, five state elections took place in Württemberg, if the election to the constituent state assembly is included. During the same period, there were nine Reichstag elections, which was due to the fact that none of the Reichstag reached the planned end of the legislative period provided for by the Weimar constitution. There was always an early dissolution of the Reichstag with the associated new elections. In addition, there were two ballots each for the election of the Reich President in 1925 and 1932. There were particularly violent disputes and wing battles in various votes on referendums, for example on the question of the expropriation of the princes in 1926, in which the SPD first tried to act together with the KPD. In Württemberg and Hohenzollern, 34.1% of voters finally spoke out in favor of expropriating the princes without compensation. In addition to the elections at the national and regional levels, there were also local elections.

State elections

From the elections on January 12, 1919 for the constituent state assembly , the majority Social Democrats , the DDP , which is in the tradition of the Württemberg People's Party , the center and bourgeois regional parties emerged as the strongest parliamentary groups. A total of 150 seats were up for grabs, with the Weimar coalition of these parties having an overwhelming majority of 121 members.

By a new state election law passed on May 8, 1920, the number of members of the state parliament to be elected in the future was set at 101. The first regular state parliament election on June 6, 1920, with a total of 55 seats, again led to an absolute majority for the Weimar coalition, although this was only narrowly maintained and the parties that rejected the Weimar Republic received over 43% of the votes. Although the SPD only took part in the government temporarily, it was not in direct opposition to government policy until 1924.

The law of April 4, 1924 reduced the number of seats in the Landtag to a total of 80. After the state elections on May 4, 1924, the Weimar coalition shrank to 39 MPs, which narrowly missed an absolute majority. The vote share of the opponents of Weimar was over 46%. Since then, the SPD in Württemberg has played the role of the opposition.

In the state elections of May 20, 1928, the Weimar coalition would have once again had an absolute majority with 47 seats. The opponents of the republic fell to 33% of the vote. Nevertheless, the SPD remained in the opposition. Exploratory talks took place between the Württemberg state chairman of the center, Josef Beyerle , and Wilhelm Keil from the SPD, but the center, under the decisive influence of Eugen Bolz , eventually continued a coalition with the citizens 'party and the farmers' union and an alliance with the SPD, which had been found incapable of government in front. The central politicians also feared that a farmers' union that had been relegated to the opposition might then have won over the rural electorate of the center.

The state election of April 24, 1932 had a devastating effect. For the first time, the vote share of the opponents of the republic (NSDAP, DNVP, WBWB and KPD) exceeded the absolute majority. The NSDAP became the strongest political force in the country with 23 seats, but the KPD was also able to grow.

The following overview shows the results of all state elections in Württemberg during the Weimar Republic :

| year | SPD | DDP | center |

WBP from 1924: DNVP / WBP 1932: DNVP |

WBB | USPD | WKWB | WBWB | DVP | KPD | VSB | CSVD | NSDAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919 | 34.5% 52 seats |

25.0% 38 seats |

20.8% 31 seats |

7.4% 11 seats |

5.8% 10 seats |

3.1% 4 seats |

2.7% 4 seats |

- | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1920 | 16.1% 17 seats |

14.7% 15 seats |

22.5% 23 seats |

9.3% 10 seats |

- | 13.3% 14 seats |

- | 17.7% 18 seats |

3.4% 4 seats |

- | - | - | - |

| 1924 | 16.0% 13 seats |

10.6% 9 seats |

20.9% 17 seats |

10.4% 8 seats |

- | - | - | 20.2% 17 seats |

4.6% 3 seats |

11.7% 10 seats |

4.0% 3 seats |

- | - |

| 1928 | 23.8% 22 seats |

10.1% 8 seats |

19.6% 17 seats |

5.7% 4 seats |

- | - | - | 18.1% 16 seats |

5.2% 4 seats |

7.4% 6 seats |

- | 3.9% 3 seats |

1.8% |

| 1932 | 16.6% 14 seats |

4.8% 4 seats |

20.5% 17 seats |

4.3% 3 seats |

- | - | - | 10.7% 9 seats |

- | 9.4% 7 seats |

- | 4.2% 3 seats |

26.4% 23 seats |

| 1933 | 15.0% 9 seats |

2.2% 1 seat |

16.9% 10 seats |

5.2% 3 seats |

- | - | - | 5.4% 3 seats |

- | 9.3% 6 seats |

- | 3.2% 2 seats |

42.0% 26 seats |

The reorganization of the state parliament, which now has only 60 seats, was carried out in accordance with the provisional law on bringing the states into line with the Reich of March 31, 1933 in accordance with the result of the Reichstag election of March 5, 1933. The KPD's seats were ineffective from the start due to the same law. which led to the absolute majority of the NSDAP with the DNVP in the state parliament. The DNVP had entered the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933 under the name Kampffront Schwarz-Weiß- Rot. The only session of the state parliament took place on June 8, 1933. The seats of the SPD became ineffective with the ordinance on the security of government of July 7, 1933. The legislative period ended on October 14, 1933. With the law on the reconstruction of the Reich , the state parliament was abolished on January 30, 1934, like all other state parliaments in Germany.

Reichstag elections

The following table shows how the people of Württemberg voted in Reichstag elections during the Weimar Republic :

| election day | KPD | USPD | SPD | center |

DDP from 1930: DStP |

DVP | CSVD |

WBP from 1924: DNVP / WBP 1932: DNVP |

BdG | VRP | WP | WBWB | NSDAP | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 19, 1919 | - | 2.81% | 35.93% | 21.54% | 25.37% | - | - | 14.09% | - | - | - | - | - | 0.26% |

| June 6, 1920 | 3.25% | 13.05% | 16.05% | 22.53% | 14.49% | 3.88% | - | 9.05% | - | - | - | 17.70% | - | - |

| May 4, 1924 | 11.48% | - | 16.00% | 20.63% | 9.48% | 4.43% | - | 10.10% | 2.48% | - | 0.68% | 19.66% | 4.23% | 0.85% |

| December 7, 1924 | 8.23% | - | 20.60% | 22.31% | 10.92% | 5.80% | - | 11.08% | - | - | 0.52% | 18.02% | 2.16% | 0.36% |

| May 20, 1928 | 7.33% | - | 23.95% | 19.20% | 9.66% | 5.61% | - | 6.31% | - | 3.70% | 1.31% | 17.58% | 1.89% | 4.45% |

| September 14, 1930 | 9.48% | - | 20.47% | 20.53% | 9.87% (with DVP) |

List with the DDP |

6.67% | 3.97% | - | 2.11% | 2.83% | 13.01% | 9.38% | 1.68% |

| July 31, 1932 | 11.18% | - | 17.96% | 20.70% | 2.45% | 0.96% | 3.67% | 3.89% | - | - | 0.18% | 7.01% | 30.53% | 1.47% |

| November 6, 1932 | 14.64% | - | 15.51% | 19.47% | 3.05% | 1.51% | 4.35% | 5.38% | - | - | 0.10% | 8.15% | 26.46% | 1.39% |

| March 5, 1933 | 9.33% | - | 15.03% | 16.94% | 2.17% | 0.70% | 3.18% | 5.17% | - | - | - | 5.38% | 42.00% | 0.10% |

In the elections for the National Constituent Assembly on January 19, 1919, the WBP and the WBWB formed a joint list. In the election on May 4, 1924, the WBP (DNVP) and the United Patriotic Associations entered the list of patriotic-ethnic rights . The NSDAP was banned in both Reichstag elections in 1924 . On May 4, 1924, the given election result is in the NSDAP column for the VSB (Völkischsozialer Block) list and on December 7, 1924 for the NSFB ( National Socialist Freedom Movement ) list.

In all elections to the Reichstag, the results of the NSDAP were well below the overall results in the Reich. This effect is due to various factors. The general economic situation in Württemberg was somewhat better than in the rest of the empire. The bond between the Catholic minority and the center as its interest group was particularly strong in Württemberg, but the bond between the Protestant rural population and the Württemberg farmers 'and vineyards' association also proved to be particularly robust. The strict Pietists remained loyal to the Christian Social People's Service . It was not until 1933 that voting behavior turned in favor of the National Socialists.

The following table compares the proportion of votes cast by the NSDAP in Reichstag elections in Württemberg and in the entire Reich:

| election day | May 20, 1928 | Sept. 14, 1930 | July 31, 1932 | Nov 6, 1932 | March 5, 1933 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Württemberg | 1.9% | 9.4% | 30.5% | 26.5% | 42.0% |

| German Empire | 2.6% | 18.3% | 37.3% | 33.1% | 43.9% |

The Reichstag election, which was carried out on November 12, 1933, with a Nazi unity list, was just a farce. Anyone who stayed away from the election or cast a negative vote was considered a traitor. On the same day it was possible to vote for the withdrawal of the German Reich from the League of Nations . On April 10, 1938, in connection with the referendum on the annexation of Austria , the NS standard list for the new Greater German Reichstag was also chosen. Officially, over 99% of voters vote “yes”.

Elections for the office of the Reich President

Only in 1925 and 1932 did the German people have the opportunity in their history to elect their head of state directly in free and secret elections, and in both cases they voted for Paul von Hindenburg .

The two tables below show how the voters in Württemberg and Hohenzollern voted in the decisive second ballot in 1925 and 1932 compared to the entire population of the Reich :