Corporal punishment

The corporal punishment or corporal punishment is a part of each relevant legal approved punishment , against the physical integrity is directed to a person. Corporal punishment intentionally inflicts temporary physical pain . According to an older understanding of corporal punishment, permanent physical damage can also be inflicted. Corporal punishment often takes the form of beatings (corporal punishment). The blows can be given as sticks or flogging on the back, buttocks, soles of the feet or other parts of the body. Slapping your hand like a slap in the face can also be corporal punishment.

Intentional but unlawful infliction of physical pain falls under the definition of physical harm and torture as abuse . Slaps can also constitute an offense .

The elderly and the corporal punishment conceptually deferrable expression of corporal punishment consisted primarily the cutting off of limbs (especially hands, ears, nose, see mutilation ), the glare , the branding , the shearing of hair (in women) and Bart (in men). The public denunciation (for example the public closing in the block ) is to be subsumed under the term of honor penalty, as it does not have a direct effect on the physical integrity.

General

Corporal punishment is still used today as a formal legal legal consequence (“punishment”). In the past, corporal punishment often served to discipline and informal punishment of subordinate or dependent people (e.g. slaves, serfs, apprentices, wives, children). These subordinate relationships prevailed in hierarchically structured organizations and institutions (e.g. military, monasteries, prisons, educational institutions, educational homes, families). Application and legal admissibility - both in the educational and legal areas - have changed significantly over time, depending on the prevailing social norms . The corporal punishments that are generally legally inadmissible today include, in particular, all forms that fall under the term torture.

In Germany and Austria, corporal punishment is prohibited by law and will be prosecuted if a criminal complaint is filed or if the public prosecutor has determined that there is a particular public interest . In addition, reasonable compensation for pain and suffering can be claimed under civil law. The husband's right to punish his wife was abolished in Germany in 1928. The parents' right to chastise their children

- phased out in Austria between 1975 and 1989 and

- Abolished without replacement in Germany in 2000 (through an amendment to the Civil Code (BGB) ): Through the tightening of Section 1631 BGB ( law to ban violence in upbringing ), children have the express "right to a non-violent upbringing": "Corporal punishment , emotional injuries and other degrading measures are not permitted. "

In Switzerland, corporal punishment against children is regarded as a “legally permitted act” within the meaning of Article 14 of the Criminal Code , whereby no assault is allowed.

Judicial corporal punishment

As judicial penalties body penalties were usually in the form of the West whipping (usually with a whip or birch left) or in the form of strokes of the cane. The blows were usually given to the back or buttocks. In the Middle East, blows with a stick on the soles of the feet ( bastinad ) are still common today. This type of punishment was also used in a variety of Western cultures, primarily for disciplining prisoners until the 20th century.

In Germany, corporal punishment was abolished as a criminal punishment in many countries as early as the first half of the 19th century, in Nassau around 1809, in Baden in 1831 or in Braunschweig in 1837. Prussia followed in 1848. With the establishment of the Reich and the introduction of a uniform Reich Penal Code in 1871 The corporal punishment was annulled as a criminal punishment throughout the entire Reich.

In the military and seafaring in particular, severe corporal punishments such as running the gauntlet , killing or jamming were used until the 19th century . In the time of National Socialism , corporal punishment with a cane on a whipping rack was used relatively often.

Today, judicial corporal punishment is seen as barbaric in many countries around the world and has at least been officially abolished - even in countries that have retained the death penalty , such as some US states. However, in other countries (particularly in Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia) they are still provided for by law. In Malaysia and Singapore, violent criminals such as rapists , but also illegal labor immigrants and perpetrators of property damage or administrative offenses, receive a corporal punishment in addition to imprisonment, which is carried out under controlled conditions and medical supervision with a rattan cane on the bare buttocks of the convicted perpetrator. Regardless of age, up to 24 blows can be given with the 120 cm long and 13 mm thick cane, which inevitably leads to serious injuries to the buttocks with lifelong scarring. In the Bahamas , corporal punishment with the stick or whip was abolished in 1984 as a relic of the colonial era , but reintroduced in 1991.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and the UN Convention against Torture that came into force in 1987 expressly forbid “cruel, unusual and degrading punishments” and categorized them as torture. The laws of many states that have ratified the UN Convention against Torture, as well as the Sharia ( Islamic law) practiced in some states, however, expressly prescribe corporal punishment. This apparent contradiction is resolved by a restriction of the term torture in Article 1 of the UN Convention against Torture : "The expression does not include pain or suffering that merely results from, belongs to or is associated with legally permissible sanctions." This does not cover corporal punishment under the concept of torture and will not be criticized by the UN Committee against Torture if there is a legal basis for this in the states practicing judicial punishment. Therefore, even at present, sovereign prisoners in many states are subject to the application of judicial corporal punishment in formalized procedures, but also in immediate execution by prison staff, in accordance with the UN Convention against Torture. Since convicted prisoners in most states are deprived of their basic rights and thus of the defense against state action, there is in fact no defense against such measures for the prisoners concerned, despite the UN Convention against Torture.

In South Africa, corporal punishment was a compulsory form of punishment for certain violent crimes and property crimes until 1965, when apartheid still prevailed . It was then converted into an optional sanction for judges and called "cane blows".

According to a report by Amnesty International , corporal punishment was carried out in 2001 in the following countries: Afghanistan , Guyana , Brunei , Iran , Malaysia , Nigeria , Saudi Arabia , Singapore , Sudan and the United Arab Emirates .

Corporal punishment in raising children

In Christian societies, children have traditionally been viewed as beings who could easily succumb to sin . American studies show that corporal punishment was understood in parts of the population as " driving out the devil " until the 20th century . Rule violations were taken very seriously because they were seen as an expression of bad character that could only be improved by harsh penalties.

As a punitive method in bringing up children, corporal punishment was probably the most common means of upbringing in the western world until the 1970s (and sometimes even beyond) . These corporal punishments were usually performed with the flat of the hand, a leather thong, a carpet beater or a thin cane on the buttocks of the child or adolescent. In the school environment, punishments were often given to the child's outstretched hand (" paws ") in addition to the trousers . In school, the rod was used earlier, later the cane and also the ruler. Other commonly used corporal punishments were slapping , head butting , pulling on the hair or ears or letting the child kneel on a pointed, triangular log .

In English the punishment on the buttocks is called " spanking ", in French "fessée", in High German "spanking". A multitude of regional dialect expressions are widespread, such as “spank your ass / get your ass full”, “get a few on the back” or “get your pants full” in Berlin, “Hosenspannes” in southern German, “do a yacht trip” and in northern Germany , “What to do” and “then the butt has fun fair” in the Ruhr area.

In contrast to the rest of the world, corporal punishment plays a lesser role in bringing up children in Northern and Central Europe and particularly in German-speaking countries. In Germany, all corporal punishment in child-rearing has been banned since 2000 due to the law banning violence in upbringing , in Sweden since 1979 (as the first country in the world) and in Finland since 1984 (as the second country in the world; 1979 was the parental right to chastise abolished). Corporal punishment has been banned in Finnish schools since 1914.

history

Antiquity

The practice of corporal punishment is transmitted from some primitive peoples , but not from others. Corporal punishment is mentioned as a punishment in almost all more advanced ancient societies , e.g. B. at the schools of the Sumerians , in ancient India or in the empire of China . A first theoretical justification for the practice of corporal punishment is found in the Hebrews in the Old Testament . Here the chastisement is not only justified but also recommended again and again, especially in the Book of Proverbs .

Examples ( standard translation ):

“If a man has a stubborn and unruly son who doesn't listen to his father's and mother's voice, and if they chastise him and he still doesn't listen, then… all the men in town should stone him and let him die. "

“He who loves discipline becomes wise; but whoever hates reprimands remains stupid. "

"Whoever saves the rod hates his son,

whoever loves him takes him for breeding early."

"Chastise your son while there is still hope,

but do not be carried away to kill him."

Deuterocanonical Books:

"Do not be ashamed of the following things: the law of the Most High and its statutes,

the righteous judgment that does not absolve the guilty, ... the frequent chastisement of children

and the beatings for a bad and indolent slave."

"Music in mourning is an inopportune speech, but discipline and beatings always testify to wisdom."

“If you love your son, you always have the stick ready for you so that you can be happy in the end. Whoever punishes his son will enjoy him and be able to boast of his acquaintances. "

However, there is also the rule in the Old Testament that corporal punishment must not dishonor or even kill the (adult) convicted perpetrator. The person to be punished may therefore receive a maximum of forty blows: "Then the judge, if the guilty party has been sentenced to a flogging sentence, should order that he lie down and receive a certain number of blows in his presence, according to his guilt. He is allowed to give him forty blows, nothing more. Otherwise your brother could be dishonored in your eyes if he was beaten too many times ”( Deut 25,2–3 EU ). In practice, a maximum of 39 blows were given so that the law was not broken by a possible miscounting.

There is also a passage in the New Testament that shows that corporal punishment is a common practice:

“For whom the Lord loves, he disciplines him; he beats every son he likes with the rod. Endure when you are chastened. God treats you like sons. For where is a son whom his father does not chasten? If you weren't chastised, as everyone has done so far, then you wouldn't really be his children, you wouldn't be his sons. "

In ancient Athens , chastisements were just as common, although Plato was the first to speak out in favor of a non-violent upbringing. Aristotle advises that a disobedient child should "be dishonored and beaten" (Politics, VII, 17).

Compared to the comparatively moderate Athens, corporal punishment played a particularly large role in the strict society of the Spartans . Hard and frequent blows should not only induce obedience here, but also harden the soul, mind and body. Plutarch reports cruel flogging for the slightest offense.

Corporal punishment in schools was primarily communicated by the Romans. Punishment instruments were there

- the scutia (leather straps),

- ferula (tail),

- virga (birch rod) and

- the flagellum (whip with knots; flagellation is a synonym for whipping )

A few Roman authors spoke out in favor of restricting the punishment to slaves because it was too dishonorable for citizens' children.

Christian Europe

With the spread of Christianity across Europe, there was no fundamental change in pedagogy. The Western European societies of the Middle Ages adopted the methods of punishment from the Romans and from their own tradition, not only in bringing up children, but also to punish adults, such as pounding in the pillory . Christianity and the Germanic tradition provided the justification for the notoriously harsh punishments of the Middle Ages in all areas of life (on the other hand, the comparatively mild penal practice in the Byzantine Empire was based on Christianity). During this time, based on biblical advice, the proverb "Take care of the rod and spoil the child" was created, equivalent to the saying "Saving on the rod takes revenge after years". Particularly tough means of education have been handed down from the monastery schools , where the children, as novices, were often “ scourged to the blood ” for the smallest mistake .

The educational means of punishment for offenses was increasingly being replaced by a more balanced combination of punishment and reward , as described by the phrase “ carrot and stick ”. Even Martin Luther (1483-1546), recommends "to lay beside the apple a rod" in parenting, and this was meant not just metaphorically. The rod that St. Nicholas brings to disobedient children is a necessary remnant.

The Age of Enlightenment did not yet bring about any major changes in the educational methods for children (→ Pedagogy of the Enlightenment , Pedagogy of Philanthropism , Black Pedagogy ). Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746–1827) reformed pedagogy , but it was not until the 19th century that individual voices were heard calling for the complete renunciation of corporal punishment in raising children.

Nevertheless, corporal punishment of children and adolescents was widespread in West Germany in (especially manual) apprenticeships until about 1960 and in elementary schools until about 1970. The transfer of the right to punishment to third parties (such as tutors) was also socially accepted until around 1970 and was not uncommon.

A trend reversal in education began in the 1960s; it happened - at least in Europe - very quickly and radically (see also the 1968 movement ). Nonetheless, in many European countries violence against children (see also child abuse ) is still tolerated or advocated by individuals.

Corporal punishment has been a barbaric relic of bygone times in Europe since the 1970s and is equated with child abuse or even with the sexual abuse of children .

A social acceptance of corporal punishment can provide a pretext for reacting to aggressive drive impulses at will, a process that is also known as sublimation in psychology (see also drive theory , behavioral patterns ).

Situation today

The Convention on the Rights of the Child of 1989, in Articles 18 and 29, obliges the signatory states to provide non-violent upbringing in the interests of equality and peace. However, corporal punishment (such as slapping or slapping the buttocks) is still legal as a means of education in most countries of the world, as long as it is “moderate” and “appropriate”, and can there especially by the parents, however - within the framework of stipulated Laws - also issued by teachers or other persons responsible for educating children.

In most European countries, since around the end of the Second World War, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, and supported by new psychological findings, the new public opinion has prevailed that corporal punishment is harmful to the development of children and is no longer used should. In Finland, corporal punishment in schools was abolished in 1914, in the GDR in 1949, in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1973. However, in 1979 the Bavarian Supreme Court declared that in the territory of the Free State of Bavaria there was “a customary right to punish teachers at elementary schools”. In 1980 corporal punishment was abolished in schools in Bavaria as well.

Nevertheless, z. Some religious communities still suggest corporal punishment as a legitimate means of education. In a more than 200-page document from 1983 called As-Salah - The Prayer in Islam , published by the Muslim book distribution company “Islamic Library”, it says:

“Children from the age of seven should be urged by their parents to pray by admonishing them, from the age of ten also if necessary, if there is no other way, by being beaten. If children perform the prayer, they will be rewarded by Allah (t) for it, but not punished by Him if they fail to do so. "

With reference to religious justifications, the corporal punishment of children is propagated in parts of the Christian fundamentalist groups. For example, in 1995 the author Tedd Tripp urged Christian parents in his book Parents: Shepherds of Hearts to use the “rod” as a means of education. By the author couple Michael Pearl and Debi Pearl is the volume How to Train Up a Child (To Train Up a Child) , in which practical advice is given on how to punish children with a rod and break their will. The book is linked to two deaths and one case of serious child abuse in the United States. At the request of the German Child Protection Association , the Federal Testing Office for writings harmful to minors indexed the book.

In 1998, a study commission of the German Bundestag on the subject of so -called sects and psycho-groups came to the conclusion that "a sometimes clear advocacy of disciplinary, corporal punishment can be found in cults , even if excessive forms of corporal punishment are rejected and criticized". The advocacy of corporal punishment in upbringing also occurs in non-religious families and is therefore not a “singular phenomenon in specific religious groups”.

When the ban on punishment was extended to private schools in 1998 , an initiative of Christian private schools was formed to reintroduce punishment in Great Britain , which was supported by 40 schools and argued with the freedom to practice religion . The legal proceedings by all instances only ended in 2005 with a rejection of the suggestion.

In 2013, the criminologist Christian Pfeiffer presented a study in which he showed that the upbringing methods of evangelical parents are more violence-oriented the more religious they are. According to this, 17.4% of the Protestant free church youth from non-academic families experienced severe parental violence in their childhood, while the percentage among Protestant or Catholic youth is 11.8 and 11.9% respectively. In addition, there is a correlation between the religiousness of the parents and the use of violence in upbringing in the parental homes of the Evangelical Free Church . 56.1% of young people from the Protestant Free Church who came from non-religious homes stated that they had been brought up without violence, whereas the corresponding percentage among young people from highly religious homes was only 20.9%.

In addition to Germany, the legal regulations prohibit parental corporal punishment in several countries, for example in Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Denmark, Norway, Austria, Italy, Cyprus, Croatia, New Zealand, Costa Rica, Venezuela and Israel. Corresponding legislative initiatives in the USA have repeatedly failed over the past decades. Since the beginning of the 1990s, parents' initiatives have been set up there to oppose such a ban.

In Sweden, corporal punishment was banned as a means of education as early as 1979, as has been the case since then in several other - mainly European - countries that have followed Sweden's example. With the amendment of Section 1631 (2) BGB by the Bundestag on July 6, 2000, children in Germany also have the right to a non-violent upbringing; that is, the use of psychological violence in the form of humiliation is also prohibited. With this, the parental right to punishment that had existed until then was repealed. Physical or emotional abuse of children during upbringing, on the other hand, has been prohibited in Germany since 1998.

Corporal punishment was long banned in primary schools in France, but it continued to be practiced for a long time, and it was not until 1991 that all punishment in preschools and all forms of corporal punishment in primary schools was expressly prohibited. The "pat on the bottom" by the parents was banned on July 10, 2019 after a long debate.

In the United States, corporal punishment is still legal in public schools in two-fifths of all US states, but it is mainly practiced in the former southern states or the Bible Belt . The punishments are usually given with a special wooden paddle or with a leather strap on the clothed (or only in rare cases bared) buttocks of the student (“paddling” / “lashing” / “strapping”). Paddling is legal in state schools in the following 19 of the 50 American states: Alabama , Arizona , Arkansas , Colorado , Florida , Georgia , Idaho , Indiana , Kansas , Kentucky , Louisiana , Mississippi , Missouri , North Carolina , Oklahoma , South Carolina , Tennessee , Texas and Wyoming (as of July 2012). According to an estimate by the United States Department of Education , there were around 458,000 paddlings at all US state schools in the 1996/97 school year, which corresponds to about 1% of the students. The highest percentage of paddling are in Arkansas and Mississippi (over 10% of the students there receive at least one paddling per school year). Figures from 2000 came to a similar result with the ranking Mississippi (9.8%), Arkansas (9.1%) Alabama (5.4%) and Tennessee (4.2%). In these states of the Bible Belt , the churches are often behind the paddling, because they see corporal punishment anchored in the Old Testament. In a 2008 study, Mississippi is once again the state with the largest number of high school students, this time 7.5% out of about 40,000 paddlings. Most paddling altogether are recorded in Texas with 50,000 cases. Black children and adolescents and Latinos are disproportionately affected; black girls were twice as likely as white girls, boys were three times as likely as girls, and children of Indian origin were also excessively affected. In the states concerned, it is up to the respective school district to determine the permissibility, reasons, scope and implementation regulations for corporal punishment. In the past, school workers have repeatedly lost their jobs because they violated relevant regulations. Some school districts prohibit it even if the state still allows it.

In all US states except New Jersey and Iowa, corporal punishment is permitted in private schools and is usually practiced there as paddling and less often as strapping .

A study published in 2005 that interviewed mothers anonymously by telephone in two states ( North Carolina , South Carolina ) found that 45.1% of children were chastised by hand blows in the past year. 24.5% of the children were hit on the buttocks with an object. In the USA, it is particularly common for younger children to rinse their mouths with soap as a (also additional) punishment for naughty answers or indecent words .

Canada tightened its laws in the spring of 2004. Since then, it has been legal there to physically punish children and young people between the ages of two and twelve years old according to certain guidelines. Contrary to the general tendency in western states to generally prohibit corporal punishment of children, however, the Canadian Supreme Court in Ottawa took a more differentiated position on January 30, 2004 and decided that parents corporal punishment of their children cannot be prohibited by law As long as the punishments are "reasonable", d. H. not be done in anger . According to the court, only corporal punishment for an important reason is “reasonable”; According to the judgment, they may only be carried out without tools (i.e. only by hand) and only on children who are at least two and not yet thirteen years old. After all, physical education measures against the head (slapping, headbuttons, pulling on the hair or ears) are prohibited without exception.

In 2006, the Supreme Court of Portugal ruled that slapping or slapping with the palm of the hand was "legal and acceptable" as a means of education and overturned a sentence sentenced a home manager for beating mentally disabled children. As a result, a 2007 criminal law banned all corporal punishment of children.

In the United Kingdom , beating students in public schools was banned first on July 22, 1986 and in 1998 for all types of schools. An appendix to the British Child Protection Act , which should generally prohibit parents from beating their children, was rejected in 2004 in the House of Commons with 424 votes to 75. Another motion prohibiting the beating of children while “leaving visible traces” was accepted by 284 votes to 208 and came into force in January 2005. In January 2006, the four UK Child Representatives called for a total ban on violence in raising children; however, this request was rejected by the Tony Blair government . Blair had admitted in the past that he occasionally hit his children. In 2018, a bill was introduced in Scotland to make it illegal for parents to beat their children. The Scottish government said it supported the bill.

In 1978, in Switzerland, the express right of parents to punish them was deleted from the civil code , but corporal punishment against children is still regarded as a “legally permissible act” within the meaning of Article 14 of the Criminal Code , as long as it is considered a parental authority. Repeated corporal punishments that exceed “the generally customary and socially tolerated level” are prosecuted ex officio as assault , as are certain physical injuries . In 1993, the federal court ruled that there was no common law of corporal punishment for teachers or anyone else caring for children. In 2008, the National Council rejected the parliamentary initiative Improved Protection for Children from Violence by Ruth-Gaby Vermot-Mangold , with which children should be protected from corporal punishment and other bad treatments "which violate their physical or psychological integrity" with 102 to 71 votes from. A study carried out by the University of Freiburg in 2004 showed that 43.9% of the parents questioned in German and French-speaking Switzerland had given corporal punishment within the last year. At the same time, the proportion of parents who stated that they had never physically punished their children rose from 13.2% in 1990 to 26.4%.

Legal situation

Right to punishment and impermissible punishment

Chastisement rights often still exist where society has traditionally accepted chastisement to enforce an authority to issue instructions or an educational mandate. Other people have no right to chastise and may be liable to prosecution if they chastise a person.

In various countries there was and is still a judicial right to punish the penal system (see above). A distinction must be made between the punishment in immediate execution (in accordance with the administrative regulations applicable in the respective states), which is carried out in individual cases at the discretion of a supervising officer as a direct reaction to a misconduct, and the punishment in a formalized procedure for serious violations, in which the relevant offense a person in captivity is initially secured largely immobile in a formal procedure and then hit on certain parts of the body such as the buttocks , soles of the feet or back . Only instructed employees are authorized to carry out the punishment. In terms of criminal law, these actions, which would otherwise fall under the criminal offense of bodily harm, are irrelevant due to the existing authorization, as long as they are within the framework prescribed by the respective legal system. These therefore do not constitute a criminal offense from the outset and are permissible according to the UN Convention against Torture. General remedies or complaints by those affected by judicial punishment to the UN Committee against Torture are therefore ineffective.

In Germany, parents used to have the right to punish their children. Other people, such as neighbors, did not have this right. So if a child got a slap from a neighbor, it could be a criminal assault act. However, the same slap in the face from the hand of one's own parents was permissible within the framework of parental chastisement.

In the scope of the right to punishment, a distinction is made between “appropriate and moderate” punishment and “mistreatment”, which are inadmissible and constitute a criminal offense . Where exactly the boundary between permissible and impermissible punishment lies was defined very differently historically and regionally.

In legal systems, however, in which there is no longer a right to punishment (e.g. in the Swedish or German legal system), this distinction is no longer made: There, every form of punishment is considered to be abuse or bodily harm.

Germany

In Germany there were various chastisement rights that were gradually revoked in the course of historical development.

Right to chastise in prison

So-called corporal punishment was mainly carried out on male and female prisoners in penitentiaries until the 20th century. During the time of the Nazi regime, corporal punishment of the most varied of types was used significantly more frequently in prisons. After the end of the Third Reich, the right to punish prisoners was gradually abolished.

Chastisement in the military

Various forms of flogging existed in the military, as well as running the gauntlet and pounding .

For the first time in Prussia, corporal punishment for soldiers under the influence of the military theorist Count Wilhelm von Schaumburg-Lippe was abolished through Scharnhorst's army reform from 1807. Until the Wars of Liberation in 1813, officers had the right to punish the soldiers under their command with blows.

Spouses' right to chastise

The Prussian Land Law (ALR), issued in 1794, gave the husband the "right to moderate punishment" of his wife. It was abolished by edict in 1812.

According to the Bavarian Codex Maximilianeus Bavaricus Civilis of 1758, the husband also had the right to chastise. In marriage, the man had the right to chastise the wife "with moderation if necessary" in order to enforce his position and rights. This has not been used by the courts since the BGB was issued in 1896, but it was not officially repealed until 1928.

Right to chastise servants, servants and apprentices

Until the beginning of the 20th century in the German Empire, the house and court servants were subject to the rule of discipline according to the rules of the servants .

With the introduction of the Civil Code on January 1, 1900, the employer's right to punish the servants (but not against minors) was abolished. According to the Prussian servants' order , the maids and servants could be chastised by their rulers. The November Revolution of 1918 put an end to the right to punishment.

Even apprentices were under the right to punish the teacher Mr . The teacher's right to “paternal discipline” vis-à-vis the apprentices (§ 127a Industrial Code (old version)) was abolished on December 27, 1951.

In seafaring, keeling was the toughest corporal punishment.

Today, in the Federal Republic of Germany, which was founded in 1949, Section 31 of the Law on the Protection of Young People at Work prohibits the punishment of children and young people.

Right to chastise in schools

Corporal punishment in schools in the Soviet occupation zone was abolished in 1945. This regulation of the SMAD was adopted by the GDR .

In the Federal Republic of Germany, in most federal states until 1973 at the latest (in Bavaria, however, until 1983), teachers at schools had the right to punish the pupils entrusted to them for their education; Corporal punishment had already been forbidden in individual federal states, or at least nominally more or less restricted. In North Rhine-Westphalia, for example, corporal punishment in schools was initially only declared inadmissible by a circular of June 22, 1971 (according to the Official Gazette, p. 420). A school child's previous sentences encouraged inappropriate social behavior. The new School Act NRW (2005) no longer contains any regulation.

In Bavaria, the prohibition of corporal punishment by teachers was only enshrined in law on January 1, 1983. However, even before the statutory regulations, some schools had school regulations that prohibited physical punishment. Nevertheless, the Bavarian Supreme Regional Court ruled in favor of a pedagogue in one case in the early 1980s on the grounds: In Bavaria "there is a customary right to punishment insofar as the teacher at elementary schools is allowed to corporally punish the boys he teaches".

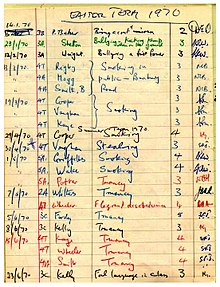

The most widespread corporal punishments, which were often noted in the class register, included slaps in the face, "headnuts" as well as the paws (blows with a ruler or cane on the palms of the student) and the student in the corner (next to the blackboard or the catheter with the Back to the class, to stand or kneel for a certain period of time, e.g. 5 or 10 minutes or until the end of the lesson (earlier also tightened: on an angular piece of wood). Corporal punishment on the buttocks, which still played a major role in the first half of the 20th century, has been increasingly reduced in schools in German-speaking countries since the end of the Second World War.

Parental right to chastise

The last right to corporal punishment, which was abolished in Germany in 2000, was the right to punish children by their parents. Previously, it was considered a parental right . Until a reform in 1980, the law used the term " parental authority "; Since then, German family law has used the term parental care (see also German Civil Code ( BGB ) §§ 1626 to 1698b ).

Historical development

In the imperial German Reich , the father had a statutory right to punish his children since 1900. Section 1631 (2) of the German Civil Code (BGB) in the version at that time read:

- By virtue of the right of upbringing, the father can use appropriate means of discipline against the child.

Before that, the right to punishment existed as customary law, as in other social contexts . The paternal right to punishment existed in the Federal Republic of Germany until July 1, 1958, when the Equal Opportunities Act came into force, since the sole paternal right to punishment constituted a violation of the special principle of equal rights for men and women in Article 3 (2) of the Basic Law (GG).

Since 1958, the parental right to chastise has continued to exist as a customary law anchored in Section 1626 of the German Civil Code (BGB) and thus included both parents (more generally the legal guardians of the child). This common law principle presented thus in the sense of criminal law a legal justification for a factual moderate injury is. Thus, the justification attacked, had

- there is concrete misconduct,

- the chastisement had to be necessary and appropriate to achieve the educational goal and

- after all, the perpetrator had to act with the will to educate.

The right to chastise was not transferable, but the exercise of the chastisement was transferable.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child , ratified by the Federal Republic of Germany in 1992, obliges the contracting states, among other things, to take all appropriate legislative measures to protect the child from any form of physical or mental violence (Article 19). However, for a long time no legal change could be implemented in Germany because criminalization of the parents was not wanted.

As part of the 1998 reform of the law on parenthood, Section 1631 (2) BGB was reformulated as follows:

- Degrading educational measures, in particular physical and mental abuse, are not permitted.

This formulation did not yet constitute a general ban on punishment, but was only directed against “degrading” educational measures and delimited permissible, non-degrading educational measures against abuse.

Current legal regulation (in family law)

In November 2000, Section 1631 (2) of the German Civil Code (BGB) was formulated as follows through the law on the prohibition of violence in upbringing :

“Children have a right to a non-violent upbringing. Corporal punishments, emotional injuries and other degrading measures are not permitted. "

Section 1631 (2) sentence 2 of the German Civil Code (BGB) is now a prohibition against parents. They are no longer allowed to use physical punishments, emotional injuries and other degrading measures when exercising personal care.

Although the current legal situation categorically prohibits punishment as an educational measure, it is tolerated in parts of the population as long as it is not associated with severe physical interventions. In the overwhelming majority of cases, however, the use of chastisement takes place in an affect and out of excessive demands, in the awareness of doing injustice and is then regretted. When the civil law prohibition of punishment was enacted, the legislature did not intend any criminal consequences, such as bodily harm.

However, in conservative Christian circles (for example in the biblical fundamentalist “ Conference for Church Planting ” , but also in traditionalist Catholicism ) there are also proponents of a deliberate, systematic and controlled parental discipline. Duty parents would expressly have to use this remedy in the fulfillment of the divine commission even if they found it unpleasant. In the dilemma of conscience, on the one hand causing pain to children and on the other hand disregarding the word of God, it is necessary to follow the Bible text. While the leadership of the evangelical DEA rejects corporal punishment, a moderate right to punishment is defended by the conference on church planting. Overall, an above-average use of corporal punishment can be observed in families that belong to a free church; every sixth student there experienced severe parental violence in childhood, more than every fourth with parents without a higher education degree. The Catholic-traditionalist Pius Brotherhood had to accept the closure of one of its private schools because of repeated punishments. She complains about this as an impairment of the “constitutional right of parents to bring up their children”.

Proponents of the parental right to punishment do not deny that the legal rule categorically prohibits caning. In order to defend their position nonetheless, they use the following lines of argument:

- The freedom of religious conscience allows the word of God to be accorded a higher authority than the law. Passages in the Old and New Testaments saw chastening of children as a legitimate means of upbringing, at least in certain cases. They are preferable to the law when there is a conflict of conscience.

- For reasons of customary law, the prohibition should not be applied in full. This view is based on parts of the legal literature, which argues with the criminal policy considerations of the legislature. Corporal punishment could therefore only be considered punishable to an extent that excludes the criminalization of large parts of parenthood. The legislature did not want this.

- The right to a non-violent upbringing should be viewed as a purely private law rule. It could not be assumed that every form of punishment should therefore also be criminally disapproved. At least the criminal liability is limited by the criterion of the relevance of the physical impairment. A "pat on the bottom" is therefore also legally harmless.

- The legal prohibition according to § 1631 Abs. 2 S. 2 BGB interferes with the constitutional parental rights according to Art. 6 Abs. 2 GG inadmissible. This violation of the fundamental right to education leads to the nullity of the law.

Opponents of the right to punishment, on the other hand, contradict the basic right argument and object that, according to the constitutional literature, the applicable provisions in the BGB lack the character of a restriction of the scope of protection of the constitutional parental right and therefore a ban on punishment is not an interference with constitutionally protected legal interests. Parents' right within the meaning of Article 6 (2) of the Basic Law does not from the outset include the right to education through corporal punishment or other degrading measures: “4. Parental rights (Art. 6 II GG) […]. In principle, controversial educational methods are also protected. However, whether physical or mental injury or other degrading measures are fundamentally and from the outset not to protect the area of parental education law . § II BGB in the version of the law to outlaw violence in upbringing (BGBl. 2000, I, 1479) is therefore not a limit, but a definition of the content of parental rights (on the criminal consequences of the punishment of children Roxin , JuS 2004, 177). "

Austria

In Austria, corporal punishment as a legal form of punishment was removed from criminal law and military criminal law in 1867. Parental chastisement was abolished in 1977: In 1974, Section 413 of the Criminal Law, which until then indirectly legitimized parental chastisement by only criminalizing abuse with physical harm, was abolished; In 1977, § 145 ABGB (old version) was abolished, which stipulated the right of parents to “chastise immoral, disobedient or domestic disorder children in a manner that is not exaggerated and harmless to their health”. Accordingly, children and adolescents in care in Austria were also subject to corporal punishment until 1977.

It was not until the Child Rights Amendment Act (KindRÄG) in 1989 that the prohibition of violence in domestic upbringing was explicitly formulated (Section 146a ABGB - expired on January 31, 2013).

According to § 47 (3) (Education Act 1986) corporal punishment is prohibited in Austrian schools.

Chastisement in Sharia law

Sura 4:34 recommends the husbands (translation by Rudi Paret ):

"And if you fear that (any) women will revolt, then admonish them, avoid them in the marriage bed and beat them!"

In Sharia , Islamic law, a husband's right to punishment is predominantly advocated on the basis of this passage from the Koran. Opinions are divided about how far this right to punishment goes in individual cases. Some Islamic scholars refer to a hadith that seeks to limit the chastisement to one blow with the miswak . Others argue that chastisement contradicts the ideal of harmonious marriage and that the term translated "beat them!" Can have other meanings.

Effects of corporal punishment

Corporal punishment or chastisement inflicts pain . The type and severity of the pain felt depend on the type of corporal punishment. The punished person is often also consciously humiliated . The humiliation can be felt to be just as severe as the physical experience of pain and trigger a high level of additional suffering . The chastised person immediately experiences the impression of helplessness and the experience of being completely powerless in relation to the chastising person and of being clearly below this in the applicable hierarchy . This effect is particularly pronounced when the punishment is carried out within the framework of an institution with sovereign authority and the punished person is therefore deprived of any opportunity to evade it or to be able to obtain compensation or satisfaction later in the event of unjustified treatment. Especially in the case of chastisements by sovereigns, lasting impairment of self-confidence and even anxiety disorders occur as soon as the person concerned is reminded of the incident or incidents.

In addition, the loss of a social reputation can occur if the chastisement is carried out publicly as in earlier times or in many cultures today (see also pillory ). Here the punishment also has the effect of a penalty of honor .

The objective of the chastisement is (besides the sanctioning of the undesired behavior in each case by creating the legal peace that is disturbed by the act ) also to deter the chastened person from repeating the punished misconduct. If a punishment is carried out publicly, this is usually done with the aim of deterring other people in order to induce them to behave in a certain way or to subordinate them to certain norms. In the case of the chastened person himself, a re-education process is usually triggered by triggering fear of a repetition of the procedure , in which the specifically punished behavior is linked with the physical and emotional experience of suffering and thus an adaptation to the dictated norms is achieved. This effect occurs even if the person concerned evaluates their sanctioned actions as justified according to their own values and rejects the dictated norms. A conditioning mechanism comes into play here, which is structurally similar in its mode of action to aversion therapy . The more unpleasant the overall punishment is assessed in the case of a chastisement and the more intensely the resulting aversion to the circumstances of the punishment as such is generated, the more likely the punished person will endeavor to follow the expected behavior of his own accord. In the case of a public performance, a similar (but weaker) effect is brought about in the attending spectators by triggering empathy with the chastised person. The strength of this effect is related to the extent to which the spectator can identify with the chastised person .

literature

- Chastisement by mother . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 1964, pp. 52 ( online - April 22, 1964 , with empirical figures and a reference to a contemporary academic book publication that concerns the situation in West Germany and West Berlin at the time).

- Bodo von Borries : From “excess of violence” to “remorse”? Autobiographical evidence of forms and changes in parental penal practice in the 18th century . Ed. diskord, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-89295-607-3 .

- Jörg Gebhardt: Corporal punishment and the right to punishment in ancient Rome and in the present. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-412-03194-1 .

- Andreas Göbel: From parental punishment right to the prohibition of violence. Constitutional, criminal and family law investigation into § 1631 Abs. 2 BGB. Kovač, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-8300-1939-4 .

- Friedrich Koch : The wild child. The story of a failed dressage. European publishing house, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 978-3-434-50410-8 .

- Ingrid Müller-Münch: The battered generation: wooden spoons, canes and the consequences. 3rd edition, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-608-94680-2 .

- Desmond K. Runyan, Viswanathan Shankar, Fatma Hassan, Wanda M. Hunter, Dipty Jain, Cristiane S. Paula, Shrikant I. Bangdiwala, Laurie S. Ramiro, Sergio R. Muñoz, Beatriz Vizcarra, Isabel A. Bordin: International Variations in Harsh Child Discipline. In: Pediatrics. August 2, 2010, doi : 10.1542 / peds.2008-2374 ( PDF; 924 kB ).

- Adam J. Zolotor, Megan E. Puzia: Bans against Corporal Punishment: A Systematic Review of the Laws, Changes in Attitudes and Behaviors. In: Child Abuse Review. Vol. 19, No. 4, July 21, 2010, pp. 229–247, doi : 10.1002 / car.1131 ( PDF; 114 kB ).

Web links

- Peschel-Gutzeit, Lore Maria: The child as a bearer of their own rights. The long road to nonviolent upbringing.

- World Corporal Punishment Research - detailed, specialized collection of documents (English)

- Countdown to the worldwide legal abolition of corporal punishment for children

- Decision of the Canadian Supreme Court in Ottawa on January 30, 2004

- Project NoSpank (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Ewald Filler: The long way from the abolition of the former “right to punish” to today's absolute “prohibition of violence” in upbringing. Federal Child and Youth Attorney, Federal Chancellery Austria, Federal Minister for Women, Families and Youth, Vienna ( archive ).

- ↑ Martin Schröder: Corporal punishment and the right to punishment in the German protected areas of Black Africa. Münster 1997, ISBN 3-8258-2880-8 , p. 5 f.

- ↑ Christoph Sodemann: The laws of apartheid. Bonn 1986, ISBN 3-921614-15-5 , pp. 173-174.

- ^ MA Straus: Beating the Devil Out of Them: Corporal Punishment in American Children. 2nd Edition. Transaction Publishers, Piscataway, NJ 2001.

- ↑ Jürgen Oelkers: Cuddle education or not? (PDF; 159 kB), p. 11 (lecture given at the University of Zurich , September 8, 2010).

- ^ A b Silvia Staub, Andrea Lier: School penalties. Teaching materials: life studies. zebis - portal for teachers. BKZ office in Lucerne, October 18, 2006, pp. 9–14 (PDF; 1.5 MB).

- ↑ a b Antje Doberer-Bey: literacy with adults. Of undesirable developments in the acquisition of written language at school and learning success in adulthood. In: Antje Doberer-Bey, Angelika Hrubesch (eds.): Live = read? Literacy and basic education in a multilingual society. Exercise book 149/2013, StudienVerlag, Innsbruck 2013, ISBN 978-3-7065-5281-3 , pp. 16–32, here p. 22 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Werner Sesink: Introduction to Pedagogy. Lit, Münster / Hamburg / London 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5830-8 , p. 70 ( limited preview in the Google book search ).

- ↑ Alice Miller: In the beginning there was education . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-518-37451-6 .

- ↑ Katharina Rutschky (Ed.): Black Pedagogy. Sources on the natural history of civic education . Ullstein, Berlin 1977; New edition ibid. 1997, ISBN 3-548-35670-2 .

- ^ Council of Europe : Thematic Dossier Physical Violence ( Memento of 6 July 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ↑ Cf. on this: Christian H. Freitag: Striking evidence - the long end of corporal punishment in England . In: Der Tagesspiegel, Berlin, from August 28, 1977. Christian H. Freitag: Great Britain: Corporal punishment - common practice . In: concerns: education 10/1977.

- ↑ Alice Miller: In the beginning there was education . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-518-37451-6 .

- ↑ Sense of Progress . In: Der Spiegel . No. 18 , 1979, p. 107-112 ( online ).

- ↑ Muhammad Rassoul : As-Salah. Prayer in Islam. Islamic Library, Cologne 1983, ISBN 3-8217-0028-9 , p. 11 ( 7.63 MB ).

- ↑ Tedd Tripp: Shepherding a Child's Heart. ISBN 0-9663786-0-1 ; German: parents: shepherds of hearts. 3L-Verlag, Friedberg 2002, ISBN 3-935188-26-9 ( excerpts ( memento of June 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on Stop the Rod; Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Michael & Debi Pearl: To Train Up A Child. No Greater Joy Ministries, 1994, ISBN 1-892112-00-0 ; German: How to get used to a boy. European Missionary Press, Wiesenbach 2002.

- ↑ Kevin Hayes: Is Conservative Christian Group, No Greater Joy Ministries, Pushing Parents to Beat Kids to Death? In: CBS News , March 4, 2010.

- ↑ Florian Götz, Oliver das Gupta: Education with the rod - love goes through the stick. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . September 24, 2010, accessed on January 1, 2013 : “After the authors' advice, the German Child Protection Association applied for the book“ How to get used to a boy ”to be indexed by the Federal Testing Office for Media Harmful to Young People. The book is now indexed. "

- ↑ Final report of the Enquête Commission “So-called sects and psychogroups”. (PDF; 6.5 MB) In: Documentation and information system for parliamentary processes. June 9, 1998, accessed August 19, 2009 (p. 86).

- ↑ Christian Pfeiffer, Christian Baier: Christian religiosity and parental authority. A comparison of the family socialization of Catholics, Protestants and members of the Evangelical Free Churches ( PDF , accessed on August 18, 2017).

- ^ Cécile Calla: Violence in Upbringing: Slap on the Po? In: time online. August 21, 2019, accessed August 26, 2019 .

- ^ The Center For Effective Discipline: US: Corporal Punishment and Paddling Statistics by State and Race

- ↑ Old School: US teachers beat with paddles. In: Spiegel Online , August 25, 2004.

- ↑ Caning: 200,000 US students are beaten. In: Spiegel Online , August 22, 2008.

- ↑ Adrea D. Theodore, Jen Jen Chang, Desmond K. Runyan, Wanda M. Hunter, Shrikant I. Bangdiwala, Robert Agans: Epidemiologic Features of the Physical and Sexual Maltreatment of Children in the Carolinas. In: Pediatrics. Vol. 115, no. 3, March 1, 2005, pp. E331 – e337, doi : 10.1542 / peds.2004-1033 ( PDF; 257 kB ).

- ↑ Angèle Fauchier, Murray A. Straus: Dimensions of discipline by fathers and mothers as recalled by university students ( Memento of April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 180 kB), Family Research Laboratory at the University of New Hampshire , 2007 . See also: Rinse mouth with soap

- ↑ Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children: State Report: Portugal ( Memento of March 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (Status: November 2012)

- ^ MPs oppose moves to ban smacking . In: BBC News , November 3, 2004.

- ↑ Calls for smacking ban rejected . In: BBC News , Jan. 22, 2006.

- ^ Scotland: Church against the criminalization of beating parents. kath.net from March 12, 2018

- ↑ Network Children's Rights Switzerland: Corporal punishment ( Memento from April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 65 kB).

- ↑ Excerpt from the judgment of the Court of Cassation of March 8, 1991 in the sense of R. against the public prosecutor of the Canton of Graubünden (annulment complaint) (BGE 117 IV 14)

- ↑ Swiss Competence Center for Human Rights (SKMR): Prohibition of the Use of Violence in Education , June 27, 2012.

- ↑ Swiss Parliament: Curia Vista - Business database: 06.419 - Improved protection for children against violence.

- ↑ Children in Switzerland: No express ban on punishment , in: Humanrights.ch accessed on July 2, 2012.

- ↑ Dominik Schöbi, Meinrad Perrez: Punitive behavior of legal guardians in Switzerland. A comparative analysis of the punishment behavior of legal guardians in 1990 and 2004. Freiburg im Üechtland 2004, p. 18 ( PDF; 685 kB ).

- ↑ Michael-Sebastian Honig: From everyday evil to injustice - On the change in meaning of family violence from "How's the family doing, German Youth Institute", 1988.

- ↑ Codex Maximilianeus Bavaricus Civilis, 1st title, VI. Chapter, § 12 No. 2. and 3., quote: "In particular, 2. the spouse is respected for the head of the family, therefore his wife is not only subordinated and subordinated to him in domesticis, but also to ordinary and decent personnel and domestic services, for which she may 3. be stopped by her husband for the fee and, if necessary, chastised with moderation. ”[quoted from: The Bavarian Land Law from 1756 in its current validity / text with note and Subject reg. ed. by Max Danzer, Munich 1894, p. 27; this comment can be viewed online in: Literature sources on German, Austrian and Swiss private and civil procedure law of the 19th century , Max Planck Institute for European Legal History (accessed on June 30, 2009)]

- ↑ Meyers Konversationslexikon, Fourth Edition, 1885–1892, Volume 16: “In the narrower sense, Z. (physical Z.) means the addition of strokes of the whip, stick or rod. The right to put a Z. on someone belongs above all to parents against their children; but also the educators, teachers, employers and teachers are granted the right of a moderate Z. " [1]

- ↑ Bayerns Lehrer und die Watschn ( Memento from July 1, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) in: Süddeutsche Zeitung online from March 11, 2010 (accessed on January 14, 2012)

- ↑ http://www.polizei-beratung.de/themen-und-tipps/gewalt/kindesmisshandlung/akte.html

- ↑ The right to a non-violent upbringing ( Memento from June 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ This can be found in the statements of all parties in the corresponding debate in the Bundestag, the 114th session of the 14th Bundestag [2]

- ↑ a b Rod Education or Biblical Education? ( Memento of October 14, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 189 kB)

- ↑ http://christliche-hauskreisgemeinde.homepage.t-online.de/Aufklarung/Brenscheidt/Die_Spaltung_der_Evangel Nahrungsmittel / brenscheidt- spaltung.pdf

- ↑ Articles on church planting & church building ( memento from March 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.ndr.de/zucht101.html ( Memento from January 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.ndr.de/regional/niedersachsen/hannover/freikirchen101.html ( Memento from April 24, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Carola Padtberg: Private school closed: Flogging teachers at the Heart of Jesus. In: Spiegel Online . February 16, 2006, accessed June 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Small encyclopedia of prejudices against the Pius Brotherhood ( Memento from April 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from March 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Wilfried Plock, Michael Leister: Community and dealing with media representatives ( Memento from March 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ); in: Community Planting No. 110 (2/2012), p. 17 (pdf; 3.5 MB); Article published under the pseudonym Markus Friedrich Legal aspects of corporal punishment ; in: Congregation No. 110 (2/2012) ( Memento from March 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), p. 27 (pdf; 3.5 MB)

- ↑ See for example Kühl , Criminal Law General Part, 5th Edition, § 9 Rn. 77b

- ^ Friedhelm Hufen : Staatsrecht II - Grundrechte. Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-56152-8 , § 16 Rn. 17, pp. 260-261.

- ↑ RIS §146a. Federal Ministry for Digitization and Business Location, accessed on December 31, 2018 .

- ↑ [proof is missing]

- ↑ Thoughts on the Qur'anic text in sura 4 verse 34 ( Memento from December 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive )