Education of the Enlightenment

The pedagogy of the Enlightenment was founded at the turn of the 19th century by philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel . At its heart was the idea that man in "wildness" was born and education into a being of reason must be used. This was opposed to the opinion of other enlightenmentists, according to which humans are naturally gifted with reason and insight. This teaching already refers to the pedagogues of romanticism.

Precursors and Early Enlightenment

It is true that since the 17th century pedagogues had called for a reform of narrow-minded education out of religious conviction, such as Johann Amos Comenius , who demanded that everyone should know everything in order to praise God's creation, or August Hermann Franke , who thought of the idea of original sin rejected. Up until the Enlightenment, however, education remained Christian education and was ruled by the paradigm that it was God who made man human. In doing so, emphasis was placed above all on the early teaching of a solid morality, but also on work education for the lower classes.

With John Locke , a phase of educational optimism begins. According to him, the child's mind is a tabula rasa ; it can be directed in different directions as easily as water. Upbringing is the main reason for the great differences between people.

With the assumption that not everything is divinely predetermined, pedagogy in the middle of the 18th century is charged with a new meaning: It is no longer just individual virtue or professional ability that is at stake, but the human future as a rational being. Enlightenment means trusting people that they see themselves as a product of their own educational practice.

The idea that man is born in a state of “wildness” and can only be made man - a creature of reason - through upbringing , won more and more supporters among the bourgeoisie and became an element of the radical self-sufficiency of bourgeois people. Educational reforms flooded the market. Upbringing took place less and less naturally, but as a conscious and purposeful formation of the human being. It was - in accordance with the spirit of the Enlightenment - aimed at wresting people from nature , emancipating them from fateful fate and making them human so that they could shape the world on their own. Kant wrote in his pedagogy lecture in 1803: “Man can only become man through education. He is nothing but what education makes of him. "

Principles of educational pedagogy

The Enlightenment believers assumed that reason cannot be acquired directly through upbringing, but only through education . The former is directed by the teacher, the latter by the student himself. In order to be able to educate people, however, according to the Enlightenment, their nature must be disciplined and brought under control. In order for the child to become educable, his “wildness” and “brutality” must first be driven out. For Heinz-Joachim Heydorn (1916–1974) maturity was “liberation of man through victory over nature”. The motivation of the Enlightenment against nature was motivated by the impression that it was imposing unbearable fetters and fateful fate on human development, for example where the birth status decides on life chances. Thus, enlightenment pedagogy consequently aims at mastering nature . “One of the main elements of education is discipline, which has the purpose of breaking the child's own will so that the purely sensual and natural may be exploited. Here one does not have to think that one is only getting along with kindness; for it is precisely the immediate will that acts according to immediate ideas and desires, not according to reasons and ideas, ” wrote Hegel in 1820 in his Basic Lines of Philosophy of Law .

Above all, Jean-Jacques Rousseau , in his work Émile or On Education (1762), thought about a natural, not just rational education. He drew attention to the costs of the civilization process celebrated by the Enlightenment and saw one in culture The process of decay of what man received from the hand of the Creator. Culture and social obligations have spoiled people: one shouldn't approach the child too early with moral ideas; it must learn from its own experience. The book was considered disreputable and was burned by the executioner in Paris; Rousseau went into exile. Goethe , on the other hand, called it a "natural gospel of education". Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi tried to apply Rousseau's prescriptions, which he had probably misunderstood, to his son Jakob and failed completely. He is considered a forerunner of reform pedagogy .

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing shows in his religious-philosophical work The Education of the Human Race , published in 1780, three stages of spiritual development and moralization of the human being. While the Old Testament wants to lead the people to the good through “ sensual punishments and rewards ”, Christ as the better educator promises him the good: “ A better educator must come and tear the exhausted elementary book from the child's hands. Christ came. “In a third stage, neither out of fear nor in view of promise, man does good and leaves evil; he then does it by virtue of his own insight and reason. Reason is given to man by nature.

Individual elements within the educational philosophy of the Enlightenment

In early modern ideas about upbringing, the use of physical and emotional violence corresponded to the prevailing opinion about so-called "child rearing". The scholar Johann Gottfried Gregorii alias Melissantes spoke out against the excessive use of force and in favor of renouncing mental intimidation because of possible lifelong psychological damage . The spread in the 18th and 19th century ideas about the "evil child nature" or the necessary "training" testify to the idea people form in a similar way to how it as dressage knew of animals.

“These first years also have the advantage that you can use force and coercion. Over the years, children forget everything they encountered in their first childhood. If one can take away the will of the children, they will never remember afterwards that they had a will. "

- obedience

Parents who have already achieved what is to be created in the child through upbringing (they have already been trained to be citizens), and who thus “make up the general and essentials” for the child, may and must demand obedience from the child : “Obedience is the beginning of all wisdom; for through it the will which is true, does not yet know the objective and makes it to its end, therefore not yet truly independent and free, rather unfinished, allows the rational will coming from outside to apply to it and gradually makes it his own " . However, as many authors later assumed, the obedience requirement did not aim to establish a sense of authority and a spirit of submission in young people. The central credo of the Enlightenment philosophers had always been to think for yourself. They assumed, however, that the free development of reason required discipline and bending "under the yoke of a certain rule". The inflection was aimed at what prevented the formation of man: his unreasonable side.

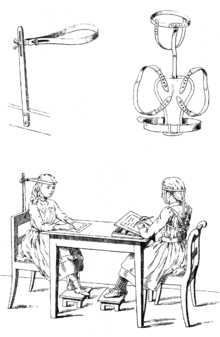

- Motor skills

The regulation of children's motor skills takes up a large part of the educational instructions for educational pedagogy . The idea was to quickly raise children to upright postures in order to quickly turn them into sensible adults. Among other things, children should not run or jump, but walk measuredly, sit up straight without crossing their legs, stay still and not grimace. Above all, the pietistic influence led to a lead pedagogy.

- Sex education

Johann Bernhard Basedow attached great importance to gender education and instruction. In his Philalethie (Altona 1764) and in the Elementarwerk 1774 he urged parents and educators not to evade the burning questions of the children, but to answer them truthfully and in a child-friendly manner. As a result of Rousseau, he criticized the unnatural nature of upbringing, but also advocated a pedagogy of hardening. Since idealized self-control includes dealing with one's own body, the educational instructions repeatedly warn against child masturbation . Although early bourgeois society cultivated the ideal image of the asexual child and adolescent, Donata Elschenbroich assumes that it was not sexuality itself that was interpreted as a threat, but rather "the self-sufficiency in playing with one's own body, which the bourgeoisie has to reject as unproductive, the devotion to the pleasure of the moment, which contradicts the planned foresight that the bourgeoisie has to develop in order to pursue its interests. ” The educational consequences hardly allow any conclusions to be drawn about what was actually meant. Onanists were warned by doctors of the imminent death to which this “disease” inevitably led, priests pointed out the sinfulness , and educators developed aids to preserve chastity.

Ending, reception and effect

From around 1800 the educational ideas of romanticism and philanthropism developed, which were clearly differentiated from those of the Enlightenment. According to Friedrich Froebel , humans should be drawn to their inner being and thus to the laws of nature. Childhood was thus discovered as an independent, valuable stage of human development: the child is by nature “innocent”, and its development must not be guided too early by pedagogical interventions. Reform pedagogy, too, emerged in the late 19th century as a direct response to the pedagogy of the Enlightenment.

In the 1970s, Katharina Rutschky and Alice Miller attempted a psychoanalytic interpretation of Enlightenment pedagogy, which they now criticized as " black pedagogy ".

See also

- Philanthropism , an educational philosophy that immediately followed Enlightenment pedagogy

Individual evidence

- ^ John Locke: Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693).

- ^ Carola Kuhlmann: Upbringing and education. Springer, 2012, p. 31 ff.

- ↑ Werner Sesink: Introduction to Pedagogy . Lit, Münster, Hamburg, London 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5830-8 , pp. 79 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Werner Sesink: Introduction to Pedagogy . Lit, Münster, Hamburg, London 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5830-8 , pp. 69 f., 78 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Kant, Immanuel: About pedagogy. Königsberg, 1803. Retrieved November 17, 2018 .

- ↑ Werner Sesink: Introduction to Pedagogy . Lit, Münster, Hamburg, London 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5830-8 , pp. 87 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: About pedagogy

- ↑ quoted from: Werner Sesink: Introduction to Pedagogy . Lit, Münster, Hamburg, London 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5830-8 , pp. 86 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Werner Sesink: Introduction to Pedagogy . Lit, Münster, Hamburg, London 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5830-8 , pp. 86 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Basic lines of the philosophy of law, or natural law and political science in the outline . Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1833, p. 236 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Karl Voss: Ways of the French literature. Berlin 1965, p. 225.

- ^ Hermann Glaser , Jakob Lehmann, Arno Lubos: Ways of German literature. Propylaea n.d., p. 130.

- ↑ Melissantes: Curieuser AFFECTen-Spiegel, Or auserlesene Cautelen and strange maxims, to explore the minds of people, and to behave carefully and cautiously afterwards , Frankfurt, Leipzig [and Arnstadt] 1715. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München , p. 627.

- ↑ Hegel: Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts , p. 327.

- ↑ Hegel: Die Philosophie des Geistes , p. 81.

- ↑ Heide Jurczek: Hello Mommy! - Recognize and mirror me: Noteworthy messages from an infant . epubli, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-8442-4764-0 , p. 112 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ FWE Mende : Obedience in education . In: Adolph Diesterweg (ed.): Guide to education for German teachers, Volume 1 . Bädeker, Essen 1850, p. 102 f., here: p. 103 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Werner Sesink: The Pedagogical Century. (PDF) Retrieved on November 23, 2018 (p. 86f).

- ↑ The crime of being a child. In: Der Spiegel . June 6, 1977. Retrieved November 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Donata Elschenbroich: Children are not born. Studies on the Origin of Childhood . Frankfurt / Main 1977, p. 141 (dissertation).

- ↑ Oliver Gellenbeck: The taboo and taboo removal of sexuality in children's books: On repression and emancipation and their effects on the current educational literature for children . Diplomica, ISBN 978-3-8324-5628-3 , pp. 58 f . ( limited preview in Google Book Search - thesis).