Prussia

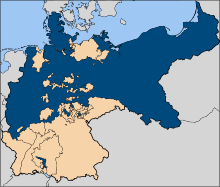

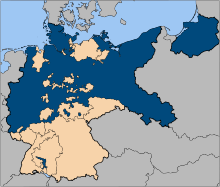

Prussia was a country on the Baltic Sea , between Pomerania , Poland and Lithuania , which had existed since the late Middle Ages , whose name was applied after 1701 to a much larger state that emerged from Brandenburg-Prussia , which eventually encompassed almost all of Germany north of the Main line and to the end of the Second World War existed.

Originally the name Prussia only referred to the core of the Teutonic Order State in the former tribal area of the West Baltic people of the Prussians and the rulers outside the Holy Roman Empire that emerged from it . After the Hohenzollern Elector of Brandenburg had elevated his Duchy of Prussia to a kingdom in 1701 and accepted the title of King in Prussia , the general name Prussia became natural for all properties of his house inside and outside the empire . In the middle of the 18th century the country rose to become the second German and fifth European great power and subsequently played an important role in the concert of the powers.

A member state of the German Confederation since 1815 , Prussia became the dominant power of the North German Confederation in 1866 and the driving force behind the founding of the German Empire in 1871 . After 1918, in the Weimar Republic , the Free State of Prussia was considered a “bulwark of democracy”. After the Prussian strike of 1932 and the coordination of the states during the National Socialist era , the Free State lost its autonomy . In 1947 the Allied Control Council declared Prussia de jure dissolved.

The capital of the Duchy and later Kingdom of Prussia was Königsberg , while that of the entire state was Berlin .

overview

The original historical landscape of Prussia , named after its native Baltic inhabitants, the Prussians , roughly corresponded to the later East Prussia . After the Teutonic Order had subjugated Prussia, for which it was not subject to any secular feudal lords due to the papal bull of Rieti (1234) , it formed the center of the Teutonic Order state together with Pomerania . Its territory was divided by Thorn in the Second Peace of 1466 : into the Royal Prussia , which was directly subordinate to the Polish crown , which included Pomerania, and into the rest of the Order , which had to recognize the Polish feudal sovereignty. As a result of its secularization, the secular Duchy of Prussia was created in 1525 , which in 1618 fell to the Electors of Brandenburg by inheritance . These now ruled both countries in personal union.

Elector Friedrich Wilhelm was able to free the duchy from Polish fiefdom in 1657. Since it was outside the borders of the empire, he was now a sovereign ruler there. This took his son Elector Friedrich III. To when in 1701 Frederick I to King of Prussia to crown. The Margraviate of Brandenburg remained the center of the Hohenzollern area. In the Silesian Wars triggered by Frederick II , the state, now known as the Kingdom of Prussia , rose to become the second German and fifth European great power. In the same epoch Prussia developed into a center of the Enlightenment in Germany. After the defeat by Napoleonic France, Prussia lost large parts of its national territory in 1806, but gained more power and prestige than before as a result of the Stein-Hardenberg reforms and victorious participation in the wars of liberation .

The Congress of Vienna brought Prussia considerable territorial gains in 1815, especially in western Germany. In the newly founded German Confederation , it was the most important power after Austria . In the course of the March Revolution of 1848, the idea of a small German empire unification under Prussian leadership emerged for the first time . Although King Friedrich Wilhelm IV rejected the imperial crown proposed to him by the Frankfurt National Assembly in 1849, the national liberal movement increasingly placed its hopes for a united Germany on Prussia. Its victory in the German War in 1866 led to the exclusion of Austria from Germany and the dissolution of the German Confederation. In its place, Prussia and the German states north of the Main Line formed the North German Confederation . During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, the southern German states, with the exception of Luxembourg, also joined the Confederation. Since then, Prussia has been the dominant federal state of the newly founded German Empire and its king, as its head, has the additional title of German Emperor .

After the overthrow of the monarchy in the November Revolution of 1918, the kingdom became the republican Free State of Prussia , which during the Weimar Republic proved to be a bulwark of democracy. In the so-called Preussenschlag , however, his state government was ousted by the Reich government in 1932. The Prussian ministers were replaced by Reich commissioners and in 1934 their ministries were merged with the relevant departments of the Reich as part of the National Socialist policy of harmonization. With the Control Council Act No. 46 of February 25, 1947, the Allied Control Council of the four occupying powers in Germany ordered the legal dissolution of Prussia. In fact, it ceased to exist as a state at the end of the war in 1945.

Both the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany and many of their countries continued Prussian traditions. The areas that formed the Prussian state until 1918 - at the time of its greatest expansion - today belong to Germany and six other states: Belgium , Denmark , Poland , Russia , Lithuania and the Czech Republic .

story

The later Kingdom of Prussia became essentially consists of two parts of the country, both by princes of the House of Hohenzollern were ruled: from the Margraviate of Brandenburg , which of the seven electorates of the Holy Roman Empire was one, and from the Duchy of Prussia, which in turn from the state of the Teutonic Order .

Teutonic Order and Duchy

After several unsuccessful attempts to conquer the tribal areas of the pagan Prussians, the Polish Duke Konrad of Mazovia called the Teutonic Order for help in 1209 and was ready to grant him land rights in the areas to be conquered. These plans took shape after Emperor Friedrich II had entrusted the Grand Master of the Order, Hermann von Salza , with the so-called “Heidenmission” in Prussia in the Golden Bull of Rimini in 1226 . In 1234 the rights of the order were also confirmed by the Pope. With the year 1226 the formation of the religious state began in Prussia, which was connected with the Holy Roman Empire , but was not part of it.

After the violent Christianization of the Prussians and the conquest of their country had been completed, the knights of the order found themselves increasingly in a legitimation crisis. In addition, there were conflicts with neighboring countries Poland and Lithuania. In the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410 the knights of the order finally suffered a decisive defeat against Poland and Lithuania. In 1466, in the Second Peace of Thorn, the state had to cede the west of its territory and recognize the suzerainty of the Polish crown for the rest . West Prussia and Warmia were henceforth directly subordinate to the Polish crown as Royal Prussia .

The remaining area of the order state roughly comprised the later East Prussia without the Warmia . The Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach , initially waged war against Poland, especially against royal Prussia with Warmia. When the hoped-for support from the empire did not materialize, he changed his policy: on the advice of Martin Luther, he converted the area of the order into a secular, hereditary duchy in the Hohenzollern family , introduced the Reformation and took it from the Polish hands on April 8, 1525 Fief of King Sigismund I in Krakow . Like the duke, his subjects also became evangelicals.

Since the Pope and Emperor neither recognized the Second Peace of Thorner nor the secularization of the order state, the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order were formally regarded as sovereigns of the Prussian territories at the Reichstag for a long time.

The Mark Brandenburg and the Hohenzollern

The real nucleus of the later Hohenzollern state of Prussia was the Mark Brandenburg. It was founded in 1157 by the Ascanian Albrecht I after he had finally conquered the territory settled by Slavs . Albrecht saw the area as an allodial property and has since called himself “Margrave in Brandenburg”. After the death of the last Ascanian margrave Waldemar in 1320, the country first fell to the Wittelsbach family , then in 1373 to the Luxembourgers .

The reason that Brandenburg finally fell to the then comparatively insignificant House of Hohenzollern was due to the controversial election of the king in 1410. After King Ruprecht's death , Sigismund of Luxembourg and his cousin Jobst of Moravia stood for election. In addition, both claimed the title and the vote of Elector of Brandenburg for themselves. Sigismund sent his brother-in-law , Burgrave Friedrich VI. von Nürnberg , as his representative in the Kurkollegium, there to cast the Brandenburg vote for him. So he initially prevailed with 4: 3 course votes against his favorite cousin. On October 1, 1410, however, the other electors recognized Jobst's claim to the Kurmark as legal, so that he was now elected Roman-German king. However, Jobst von Moravia died on January 18, 1411 of unknown cause. The crown finally went to Sigismund. In 1415, King Sigismund granted Hohenzollern the hereditary dignity of Margrave and Elector of Brandenburg to thank Frederick for his service in the first election and to settle his debts. In 1417 he formally enfeoffed him with the Kurmark and the office of arch chamberlain . In return, the wealthy Friedrich granted his brother-in-law loans that he could use to cover his war costs in Hungary .

Friedrich came from the Franconian line of the Hohenzollern and had been burgrave in Nuremberg since 1397 . In the years after 1411 he secured his supremacy in the country in years of battles against the reluctant Brandenburg nobility . As Friedrich I of Brandenburg, from now on he combined the titles of Elector of Brandenburg , Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach . He founded the Brandenburg line of his house, which would later provide all the kings of Prussia and from 1871 to 1918 the German emperors .

Brandenburg-Prussia (1618–1701)

In 1618 the ducal-Prussian line of the House of Hohenzollern became extinct in the male line. Their heirs, the Margrave and Elector of Brandenburg, governed from then on the two countries in personal union . They were thus both the Emperor and the King of Poland loan fee . The term Brandenburg-Prussia for the widely spaced Hohenzollern territories is not contemporary, but has become naturalized in historical studies to denote the transition period from 1618 to the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 and at the same time the continuity between the Electorate of Brandenburg and the Emphasize Kingdom of Prussia.

Thirty Years' War

A few years before the Thirty Years War , Brandenburg had also been able to secure rule over the Duchy of Kleve and the counties of Mark and Ravensberg in the west of the empire in the Jülich-Klevian succession dispute . The country was initially spared from the war itself. In 1625, however, the Danish-Lower Saxon War broke out, in which some Protestant states in northern Germany, led by Denmark and supported by England and the States General , opposed the Catholic League and the Emperor. After the defeat of the Danish army near Dessau in April 1626, imperial troops invaded the march. Elector Georg Wilhelm , who had no significant armed forces at his disposal, withdrew to the Duchy of Prussia, which was outside the empire, and in 1627 was forced to conclude an alliance with the emperor. From then on, Brandenburg served the imperial troops as a deployment and retreat area.

On July 6, 1630, the Swedish king Gustav Adolf landed on Usedom with 13,000 men . This marked the beginning of a new phase in the Thirty Years War. When Gustav Adolf moved into Brandenburg in the spring of 1631, he forced the elector, his father-in-law, to form an alliance. After the Swedish troops were defeated in the Battle of Nördlingen on September 6, 1634, the Protestant alliance broke up. Brandenburg entered into a new alliance with the emperor. The Kurmark was now occupied alternately by opponents and allies. The elector withdrew again to Königsberg in Prussia , where he died on December 1, 1640.

The new elector was his son Friedrich Wilhelm . The primary goal of his policy was to pacify the country. He tried to achieve this through a settlement with Sweden, which was valid for two years from July 24, 1641. In negotiations with the Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna , the Brandenburgers succeeded on May 28, 1643 in negotiating a contract that formally returned the entire country to the electoral administration. Until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, however, some permanent places in Brandenburg remained occupied by the Swedes. In the Peace of Westphalia, Brandenburg-Prussia was able to acquire Upper Pomerania , the Halberstadt Monastery and the Principality of Minden , as well as the entitlement to the Magdeburg Archbishopric , which came into effect in 1680. The territorial gains made a total of about 20,000 km².

Consolidation and reform policy of the Great Elector

Brandenburg was one of the German territories hardest hit by the Thirty Years War. Large stretches of land were devastated and depopulated. In order to spare the country from being the plaything of more powerful neighbors in the future, Friedrich Wilhelm, later called the Great Elector , pursued a cautious rocking policy between the great powers after the war, as well as building a powerful army and an efficient administration. He built up a standing army that made Brandenburg a sought-after ally of the European powers. This made it possible for the elector to receive subsidy payments from several sides. He set up his own Brandenburg Navy and in later years pursued colonial projects in West Africa and West India . After the Groß Friedrichsburg Fortress was founded in 1683 by the Brandenburg-African Company in what is now Ghana , Brandenburg took part in the international slave trade .

Inside, Friedrich Wilhelm carried out economic reforms and initiated extensive peuplication measures in order to develop his economically weakened country. Among other things, he invited thousands of Huguenots expelled from France to settle in Brandenburg-Prussia in the Edict of Potsdam in 1685 - his answer to the Edict of Fontainebleau of King Louis XIV . At the same time he disempowered the estates in favor of an absolutist central administration. In doing so, he laid the foundation for the Prussian civil service , which had enjoyed a reputation for efficiency and loyalty to the state since the 18th century.

In the Treaty of Wehlau in 1657, the elector succeeded in releasing the Duchy of Prussia from Polish sovereignty. In the Peace of Oliva of 1660, the sovereignty of the duchy was finally recognized. This was a crucial prerequisite for his elevation to kingdom under the son of the great elector. Thanks to the victory in the Swedish-Brandenburg War (1674–1679), the state was able to further expand its position of power despite the lack of land gains. During his tenure, Friedrich Wilhelm made the previously comparatively insignificant Brandenburg the second most powerful territory in the empire after Austria. This laid the foundation for the future kingdom.

At the instigation of Friedrich Wilhelm and his Orange wife Luise Henriette , important Dutch scholars, especially from the University of Leiden , contributed to the modernization of the Brandenburg-Prussian state. “Through the Leiden philosopher Justus Lipsius there was an effective contact between Calvinism and neoicism , which with their demand for active commitment, hard fulfillment of duties and inner discipline became elements of the civil service, the elite of which was almost without exception trained in Holland . In Leiden , Samuel von Pufendorf also took over the basic principles of natural law thinking from Hugo Grotius . "

Kingdom of Prussia (1701-1918)

Achievement of the royal dignity by Frederick I (1701–1713)

The rank, reputation and prestige of a prince were important political factors in the era of absolutism . Elector Friedrich III. therefore used the sovereignty of the Duchy of Prussia to strive for its elevation to kingdom and its own to king . Above all, he tried to maintain equality of rank with two other electors, with that of Saxony , who was also King of Poland, and that of Braunschweig-Lüneburg , who was a candidate for the English throne.

Since there could be no crown within the Holy Roman Empire except that of the emperor, Elector Friedrich III. strive for royal dignity for the Duchy of Prussia instead of the actually more important part of the country, the Mark Brandenburg . Emperor Leopold I finally agreed that Frederick should receive the title of king for the Duchy of Prussia, which was not part of the empire. Elector Friedrich III. crowned himself on January 18, 1701 in Königsberg and became Frederick I, King in Prussia .

The restrictive title " in Prussia" was necessary because the designation "King of Prussia" would have been understood as a claim to rule over the entire Prussian territory. Since Warmia and western Prussia ( Pomerania ) were still under the sovereignty of the Polish crown at that time, this would have provoked conflicts with the neighboring country, whose rulers claimed the title of "King of Prussia" until 1742. Since 1701, however, the term Kingdom of Prussia has gradually become commonplace in general German usage for all areas ruled by the Hohenzollerns - whether located within or outside the Holy Roman Empire. The capital Berlin and the summer residence Potsdam remained the centers of the Hohenzollern State . However, all royal coronations traditionally took place in Königsberg.

Friedrich I left the political business largely to the so-called Three Counts Cabinet . He himself concentrated on an elaborate court holding of the Prussian court based on the French model, which brought his state to the brink of financial ruin. He financed the pageantry at court, among other things. by leasing Prussian soldiers to the Alliance in the War of the Spanish Succession . When Friedrich I died on February 25, 1713, he left behind a mountain of debt of twenty million thalers.

Centralization and militarization under Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713–1740)

The son of Friedrich I, Friedrich Wilhelm I , was not fond of splendor like his father, but was economical and practical. As a result, he kept household expenses to a minimum. Everything that served the courtly luxury was either abolished or used for other purposes. All of the king's austerity measures were aimed at building up a strong standing army , in which the king saw the basis of his internal and external power. This attitude earned him the nickname "Soldier King". Nevertheless, Friedrich Wilhelm I only led a brief campaign in the Great Northern War during the siege of Stralsund once during his tenure . As a result, Prussia not only gained part of Western Pomerania, but thanks to the prestigious victory over the Swedes also gained international renown.

Friedrich Wilhelm I revolutionized the administration, among other things with the founding of the general directorate . In doing so, he centralized the country, which was still territorially fragmented, and gave it a unified state organization. Through a mercantilist economic policy, the promotion of trade and industry and a tax reform, the king succeeded in doubling the annual state income. In order to attract the necessary skilled workers, he introduced compulsory schooling and set up economics chairs at Prussian universities, the first of their kind in Europe. In the course of an intensive population policy , he let people from all over Europe settle in his sparsely populated provinces.

When Friedrich Wilhelm I died in 1740, he left behind an economically and financially stable country. With him, however, the militarization of Prussia began, although its scope and effects are controversial.

Rise to great power under Friedrich II. (1740–1786)

On May 31, 1740, his son Friedrich II - later called Friedrich the Great - ascended the throne. In his first year of reign he let the Prussian army march into Austria's Silesia , to which he laid claim. This marked the beginning of the Austro-Prussian dualism , the struggle between the two leading German powers for supremacy in the empire.

In the three Silesian Wars (1740–1763) it was possible to secure the newly won province for Prussia. In the third, the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), Prussia, allied with Great Britain , faced a coalition of Austria, France, Russia and Saxony and, despite great military successes, came to the brink of collapse. It was saved from defeat only by the failure of Austria and Russia to conquer Berlin together after Frederick's devastating defeat in the battle of Kunersdorf (" Miracle of the House of Brandenburg "), as well as by the death of Tsarina Elisabeth . Her successor, Tsar Peter III. , was an admirer of Frederick and detached Russia from the alliance. His opponents were forced to come to an understanding with Friedrich and, in the Treaty of Hubertusburg , granted him the final possession of Silesia. Prussia, whose army was now considered to be one of the best in Europe, had risen to become the fifth great power.

Frederick II was a representative of enlightened absolutism and saw himself as “the first servant of the state”. In this way he abolished torture , reduced censorship, laid the foundation for general Prussian land law and, by granting complete freedom of belief, brought more exiles into the country. Under his government, the development of the country was promoted as well as the population of previously largely uninhabited areas, such as the Oder and Netzbruch .

Together with Austria and Russia, Friedrich operated the partition of Poland . At the first division in 1772 he acquired Polish Prussia , which was incorporated into West Prussia , the Netzedistrikt and the Duchy of Warmia , which came to East Prussia . This meant that the Hohenzollern territories of Pomerania and East Prussia were no longer separated from each other by Polish territory. In addition, all Prussian areas now belonged to the Hohenzollern State, so that Frederick could now call himself King "of Prussia". He died on August 17, 1786 at Sanssouci Palace .

Stagnation and end of the Prussian feudal state (1786–1807)

After the death of Friedrich II, his nephew Friedrich Wilhelm II (1786–1797) ascended the Prussian throne. In the 1790s, Berlin grew into a handsome city characterized by classicism . Here, as in the rest of the empire, the rising educated bourgeoisie generally welcomed the French Revolution . Since 1794, the general land law was in force in Prussia , a comprehensive set of laws, the drafting of which had already begun under Frederick II.

In terms of foreign policy, Prussia forced Austria into a separate peace in the Russo-Austrian Turkish War in 1790 through an alliance with the Ottoman Empire . Friedrich Wilhelm continued the partition policy towards Poland, so that Prussia was able to secure further areas as far as Warsaw in the second and third partition of Poland (1793 and 1795). The new provinces of South Prussia (1793), New East Prussia and New Silesia (both 1795) were formed from them. The population initially grew by 2.5 million, but the new acquisitions were lost again after the defeat against France in 1806.

The French Revolution brought about a rapprochement between Austria and Prussia. Although the Prussian government had viewed the revolution benevolently at the beginning, it concluded a defensive alliance with Austria on February 7, 1792. Because of the Pillnitz Declaration in favor of King Louis XVI. France declared war on both countries on April 20, 1792. In the First Coalition War , the initial rapid advance after the Valmy cannonade was followed by the withdrawal of Prussian and Austrian troops from France. Then French revolutionary troops advanced as far as the Rhine. After the Treaty of Basel in 1795, Prussia left the anti-French alliance for more than a decade. Friedrich Wilhelm II died on November 16, 1797. He was followed by his son Friedrich Wilhelm III. (1797-1840) to the throne.

Between 1795 and 1806, Prussia benefited from a foreign policy favored by France. With his support, it actually became the dominant power in northern Germany. In the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803, the state received a large part of the bishopric of Münster , the dioceses of Hildesheim and Paderborn and other areas as compensation for losses on the left bank of the Rhine . As a result, its territory grew by around 3 percent and its population by around 5 percent. In addition, Prussia briefly occupied the Electorate of Hanover, which is connected to Great Britain .

When negotiations with France on the division of power in Germany failed in 1806, war broke out again. In the battle of Jena and Auerstedt , Prussia suffered a crushing defeat against the troops of Napoleon I , which meant the fall of the old Prussian state. In the Peace of Tilsit in 1807, Prussia lost about half of its territory: all areas west of the Elbe as well as the gains from the second and third division of Poland. In addition, the country had to accept a French occupation, supply the foreign troops and make high contributions to France. In fact, Prussia lost its great power position and, in terms of size and function, was only a buffer state between France and Russia.

State reforms and wars of liberation (1807-1815)

The conditions of the Tilsit peace, which were perceived as intolerable, also brought about a renewal of the state. The fundamental reforms that were undertaken after 1807 aimed domestically at changing the conditions that had led to the defeat of 1806 and externally at shaking off French hegemony. The state was modernized with the Stein-Hardenberg reforms under the leadership of Freiherr vom Stein , Scharnhorst and Hardenberg . In 1807, the peasants' serfdom was abolished, local self-government was introduced in 1808 and freedom of trade was granted in 1810 . The envoy Wilhelm von Humboldt , who was recalled from Rome, redesigned the educational system and founded the first Berlin university in 1809 , which today bears his name. The army reform was completed in 1813 with the introduction of general conscription.

In Napoleon's Russian campaign of 1812 , Prussia took part as an ally of France. After the defeat of the "Grande Army", however, the Prussian Lieutenant General Graf Yorck concluded the Tauroggen Convention on December 30, 1812 with the General of the Russian Army, Hans von Diebitsch . It provided for an armistice and said that Yorck should separate his Prussian troops from the alliance with the French army. Yorck acted on his own initiative, without orders from his king, who for several months wavered between the enforced loyalty to France and a policy that was friendly to Russia. The Tauroggen Convention was understood in Prussia as the beginning of the uprising against French rule. Finally, Friedrich Wilhelm also managed to change politics. When he called for the liberation struggle on March 20, 1813 in the Silesian privileged newspaper with his appeal " To Mein Volk ", which was dated March 17, 300,000 Prussian soldiers (6% of the total population) were standing by. General conscription was introduced for the duration of the upcoming war. Prussian troops under Blücher and Gneisenau made a decisive contribution to the victory over Napoleon in the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, in the Allied advance to Paris in the spring campaign in 1814 and in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

From the Restoration to the March Revolution (1815–1848)

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Prussia was given back most of its national territory, which had existed since 1807. The rest of Swedish Pomerania and the northern part of the Kingdom of Saxony were added . In addition, Prussia gained considerable areas in the west, which it soon combined to form the province of Westphalia and the Rhine province , when it was united with the former western state territory . In the new provinces in the west, mighty fortresses were built in Koblenz , Cologne and Minden , built according to the New Prussian fortification manner , to secure Prussian supremacy. Prussia got back the former Polish province of Posen , which had become part of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 , but lost territories from the second and third partition of Poland to Russia. Since then, the Prussian state has consisted of two large, but spatially separated country blocks in East and West Germany. Prussia became a member of the German Confederation .

The promise made to his people during the wars of freedom to give the country a constitution was canceled by Friedrich Wilhelm III. not a. In contrast to most other German states, in Prussia no representative body was created for the entire state. Instead of a state assembly for all of Prussia, only provincial parishes were convened. The law of June 5, 1823 gave them a say. Conditions therefore prevailed as in a corporate state , because in addition to the influential nobility in the provinces, the cities had self-government, even if there was a certain state supervision.

The royal government believed that it could prevent liberal efforts towards a constitutional monarchy and democratic rights of participation. The goal of suppressing democratic aspirations throughout Europe was served on the foreign policy level by the Holy Alliance , which Friedrich Wilhelm III. together with the Tsar of the Russian Empire and the Emperor of Austria .

However, the efforts of the royal government to combat liberalism, democracy and the idea of the unification of Germany were opposed by strong economic constraints. Due to the division of its national territory into two parts, the economic unification of Germany after 1815 was in Prussia's own interests. The kingdom was therefore one of the driving forces behind the German Customs Union , of which it became a member in 1834.

Due to the success of the Zollverein, more and more supporters of German unification placed their hopes on Prussia replacing Austria as the leading power of the federal government. The Prussian government, however, did not want to get involved in the political unification of Germany.

The hopes that the accession of Friedrich Wilhelm IV. (1840–1861) had initially aroused among liberals and supporters of German unification were soon disappointed. Even the new king made no secret of his aversion to a constitution and an all-Prussian state parliament.

However, the large financial requirements for the construction of the eastern railway required by the military required the approval of budget funds from all provinces. That is why the United State Parliament was finally convened in the spring of 1847 . In his opening speech, the king made it unmistakably clear that he saw the state parliament only as an instrument for granting money and that he did not want any constitutional issues discussed. Since the majority of the state parliament demanded not only the budget approval right from the beginning, but also parliamentary control of state finances and a constitution, the body was dissolved again after a short time. Prussia was thus faced with a constitutional conflict even before the outbreak of the March Revolution .

After the popular uprisings in southwest Germany, the revolution finally reached Berlin on March 18, 1848. Friedrich Wilhelm IV., Who initially had the rebels shot, had the troops withdrawn from the city and now seemed to bow to the demands of the revolutionaries. The United State Parliament met again to resolve the convening of a Prussian National Assembly , which met from May 22 to September 1848 in the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin .

The Prussian National Assembly had been given the task of working out a constitution with it. However, the National Assembly did not approve the government draft for a constitution, but worked out its own draft with the Waldeck Charte . The constitutional policy of the Prussian National Assembly also led to a counter-revolution: the dissolution of the assembly and the introduction of an imposed (decreed) constitution by the state leadership. This imposed constitution retained certain points of the charter, but on the other hand restored central prerogatives of the crown. Above all, the three-class suffrage that was introduced had a decisive influence on the political culture of Prussia until 1918.

In the Frankfurt National Assembly, the proponents of a Greater German nation-state first prevailed, who envisaged an empire including the German-speaking parts of Austria. Since Austria only wanted to agree to unification of the empire with the involvement of all of its parts of the country, the so-called small German solution was finally decided. H. an agreement under Prussia's leadership. However, democracy and German unity failed in 1849 when Friedrich Wilhelm IV rejected the imperial crown offered to him by the National Assembly. The revolution was finally put down in southwest Germany with the help of Prussian troops.

From the revolution to the founding of the federal government (1849–1866)

While the revolution was being crushed, Prussia made another attempt at unification, albeit with a more conservative draft constitution and closer cooperation with the medium-sized states. Meanwhile Austria tried to enforce a Greater Austria . After the political and diplomatic conflict between the two German great powers had almost led to war in the autumn crisis of 1850 , Prussia finally gave up its Erfurt Union . The German Confederation was restored almost unchanged.

During the Reaction Era , Prussia and Austria again worked closely together to suppress democratic and national movements; but Prussia was denied equal rights. King Wilhelm I ascended the Prussian throne in 1861. With War Minister Roon , he sought an army reform that provided for longer periods of service and an arming of the Prussian army . However, the liberal majority in the Prussian state parliament , which had budget rights , did not want to approve the necessary funds. A constitutional conflict arose , in the course of which the king considered abdicating .

As a last resort, Wilhelm decided in 1862 to appoint Otto von Bismarck as Prime Minister . This was a vehement supporter of the royal claim to autocracy and ruled for years in the conflict period against the constitution and parliament and without a statutory budget. Recognizing that the Prussian crown could only gain popular support if it took the lead in the German unification movement, Bismarck pursued an offensive policy that led to the three wars of unification .

With the so-called November constitution of 1863, the Danish government tried - contrary to the provisions of the London Protocol of 1852 - to bind the Duchy of Schleswig more closely to the actual Kingdom of Denmark , excluding Holstein . This triggered the German-Danish War in 1864 , which Prussia and Austria waged together on behalf of the German Confederation. After the victory of the troops of the German Confederation, the Danish crown had to renounce the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg in the Peace of Vienna . The duchies were initially administered jointly by Prussia and Austria.

Soon after the end of the war with Denmark, a dispute broke out between Austria and Prussia over the administration and the future of Schleswig-Holstein. Its deeper cause, however, was the struggle for supremacy in the German Confederation. Bismarck succeeded in persuading King Wilhelm, who had been hesitant for a long time for reasons of loyalty to Austria, to find a martial solution. On the part of Prussia, in addition to some small northern German and Thuringian states, the Kingdom of Italy also entered the war (→ Battle of Custozza and Sea Battle of Lissa ).

In the German War , Prussia's army under General Helmuth von Moltke achieved the decisive victory in the Battle of Königgrätz on July 3, 1866 . In the Peace of Prague on August 23, 1866, Prussia was able to enforce its demands: Austria had to recognize the dissolution of the German Confederation , renounce participation in the “new formation of Germany” and recognize the “closer federal relationship” that Prussia had with the German states north of the Main line received. While Prussia incorporated several member states of the dissolved German Confederation, Austria remained territorially untouched at the urging of Bismarck and against the resistance of King Wilhelm. This was a crucial prerequisite for the later alliance with the Danube monarchy.

North German Confederation and Forging an Empire (1866–1871)

As a result of the German War, Prussia increased its power considerably. First, on August 18, 1866, it concluded a defensive alliance with its allies. The August Alliance prepared the foundation of the North German Confederation . With the annexations of October 1866 , Prussia officially annexed the territories already occupied during the war: the Kingdom of Hanover , the Electorate of Hesse- Kassel, the Duchy of Nassau , the Free City of Frankfurt and all of Schleswig-Holstein. From then on, almost all of northern Germany formed a closed Prussian state territory. In addition, Prussia entered into so-called protective and defensive alliances with the formerly opposing southern German states of Bavaria , Württemberg and Baden . Only Austria and Liechtenstein were excluded from this.

Inside, Bismarck put an end to the Prussian constitutional conflict that had been smoldering since 1862 with the Indemnity Act . It subsequently granted the Prussian state parliament the right to approve the budget, while Bismarck granted impunity for its unconstitutional government action. The right-wing liberals, the later National Liberals, supported the bill and worked closely with Bismarck. The left liberals remained in the opposition. The Conservatives also split over the question of whether to support Bismarck and his policies.

Prussia's policy towards Austria was only possible because France remained neutral. Therefore, Bismarck had Napoleon III. with vague promises that Luxembourg would eventually be left to France , induced them to condone this policy. Now, however, France was faced with a strengthened Prussia, which no longer wanted to have anything to do with the earlier territorial commitments. In 1870, the dispute over the Spanish candidacy for the throne of the Catholic Hohenzollern Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen escalated , which Bismarck used to provoke war with France. After Bismarck published the so-called Emser Depesche , the French government declared war on Prussia. For the southern German states of Bavaria , Württemberg , Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt , which is still independent south of the Main Line , the case of an alliance came into being .

After the rapid German victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the ensuing national enthusiasm throughout Germany, the southern German princes now also felt compelled to join the North German Confederation. This was followed by the establishment of the German Empire in the small German version, which had already been envisaged as a model of unification by the National Assembly in 1848/49. The Imperial Constitution, which came into force on January 1, 1871, transferred the Federal Presidium to the Prussian King. As part of a proclamation in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles , Wilhelm I accepted the title of " German Emperor " on January 18, 1871, the 170th anniversary of Frederick I's coronation . Therefore, not the 1st, but the 18th of January was later celebrated as the official founding day of the Reich .

In the German Empire (1871-1918)

In the German Empire (1871–1918), German and Prussian politics were always closely linked; for the King of Prussia was at the same time German Emperor and the Prussian Prime Minister - with the exception of the brief terms of office of Botho zu Eulenburg and Albrecht von Roon - always also Chancellor .

Between 1871 and 1887 Bismarck led the so-called Kulturkampf in Prussia in order to reduce the influence of Catholicism . Resistance from the Catholic population and the clergy, especially in the Rhineland and in the formerly Polish areas, forced Bismarck to end the dispute without any result. In the eastern parts of Prussia, which are mostly inhabited by Poles, the Kulturkampf was accompanied by an attempt at a policy of Germanization.

Wilhelm I was followed in March 1888 by Friedrich III, who was already seriously ill . who died after a reign of just 99 days. In June of the " Three Emperors Year " Wilhelm II ascended the throne. He dismissed Bismarck in 1890 and from then on largely determined the politics of the country himself. This only changed in the course of the First World War , when both the Emperor and the Imperial Government largely left the policy competence to the Supreme Army Command under Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff . However, the victorious powers saw the Kaiser as one of the main culprits for the outbreak of war. In several replies to the German request for a ceasefire in October 1918, they pressed for his abdication in clauses. Wilhelm II initially considered abdicating only as German Emperor, but not as King of Prussia. Because of his hesitation, the revolutionary situation in Berlin worsened. In order to defuse them, Chancellor Max von Baden announced on November 9 that the emperor would renounce both crowns without his consent. This de facto ended the monarchy in Prussia and Germany. On November 28th, Wilhelm II also formally abdicated while in exile in the Netherlands. The Prussian royal crown is now in Hohenzollern Castle near Hechingen .

Free State of Prussia in the Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

With the end of the Empire, Prussia was proclaimed an independent Free State within the Reich Association and in 1920 received a democratic constitution.

With the exception of the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine, which was formed after the Franco-Prussian War, and parts of the Bavarian Palatinate, Germany's territory ceded by the Treaty of Versailles concerned exclusively Prussian territory: Eupen-Malmedy went to Belgium, Northern Schleswig to Denmark, the Hultschiner Ländchen to Czechoslovakia . Large parts of the areas of West Prussia and Posen , which Prussia had received as part of the partitions of Poland, as well as East Upper Silesia went to Poland . Danzig became a free city under the administration of the League of Nations and the Memelland came under Allied administration. As before the Polish partitions, East Prussia was separated from the rest of the country by Polish territory. From the territory of the Reich it could be reached by ship - with the East Prussian Sea Service -, by air or by train through the Polish Corridor . The Saar area , which has now been administered by the League of Nations for 15 years, was mainly formed from Prussian areas.

The annexation of the Free State of Waldeck represented an increase in Prussian territory during the Weimar Republic . This small state had already lost part of its sovereign rights to Prussia through an accession treaty in 1868 . After a referendum in 1921, the Waldecker Kreis Pyrmont came to the Prussian province of Hanover. The termination of the accession agreement by Prussia five years later led to major financial problems in the remaining part of Waldeck, which was then finally incorporated into the Prussian province of Hessen-Nassau in 1929.

From 1919 to 1932, governments of the Weimar coalition ( SPD , Zentrum and DDP ) ruled in Prussia , expanded to include the DVP from 1921 to 1925 . Unlike in some other countries of the Reich, the majority of the democratic parties in elections in Prussia were not endangered until 1932. The East Prussian Otto Braun , who ruled almost continuously from 1920 to 1932 and is still considered one of the most capable social democratic politicians of the Weimar Republic , implemented several pioneering reforms together with his Interior Minister Carl Severing , which later set an example for the Federal Republic . This included the constructive vote of no confidence , which only made it possible for the Prime Minister to be voted out if a new Prime Minister was elected at the same time. In this way, the Prussian state government could remain in office as long as no positive majority formed in the state parliament, i.e. a majority of those opposition parties that really wanted to work together.

The state elections of April 24, 1932 did not produce a positive majority either, as the radical parties KPD and NSDAP together received more seats than all other parties combined. Because there was no governing coalition in parliament, the Braun government remained in office. This provided Chancellor Franz von Papen with the pretext for the so-called “ Prussian strike ”. With this coup d'état , on July 20, 1932, the Reich government deposed the Prussian state government by decree on the pretext that it had lost control of public order (see also: Altona Blood Sunday ). Welcomed by the majority of the state apparatus, von Papen himself took over power as Reich Commissioner in Prussia, which until then “had been able to do justice to its role as a bulwark of Weimar democracy to a certain extent”. The removal of the most important, democratically-minded state government made it much easier for Adolf Hitler to take power six months later. As a result, the National Socialists had the means of power of the Prussian government - above all the police - at their disposal from the start.

| year | 1919 | 1921 | 1924 | 1928 | 1932 | 1933 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political party | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats |

| SPD | 36.4 | 145 | 25.9 | 109 | 24.9 | 114 | 29.0 | 137 | 21.2 | 94 | 16.6 | 80 |

| center | 22.3 | 94 | 17.9 | 76 | 17.6 | 81 | 15.2 | 71 | 15.3 | 67 | 14.1 | 68 |

| DDP / DStP | 16.2 | 65 | 5.9 | 26 | 5.9 | 27 | 4.4 | 21 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.7 | 3 |

| DNVP | 11.2 | 48 | 18.0 | 76 | 23.7 | 109 | 17.4 | 82 | 6.9 | 31 | 8.9 | 43 |

| USPD | 7.4 | 24 | 6.4 | 27 | ||||||||

| DVP | 5.7 | 23 | 14.0 | 59 | 9.8 | 45 | 8.5 | 40 | 1.5 | 7th | 1.0 | 3 |

| DHP | 0.5 | 2 | 2.4 | 11 | 1.4 | 6th | 1.0 | 4th | 0.3 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 |

| SHBLD | 0.4 | 1 | ||||||||||

| KPD | 7.5 | 31 | 9.6 | 44 | 11.9 | 56 | 12.3 | 57 | 13.2 | 63 | ||

| WP | 1.2 | 4th | 2.4 | 11 | 4.5 | 21 | ||||||

| Poland | 0.4 | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | ||||||||

| NSFP | 2.5 | 11 | ||||||||||

| NSDAP | 1.8 | 6th | 36.3 | 162 | 43.2 | 211 | ||||||

| CNBL | 1.5 | 8th | ||||||||||

| VRP | 1.2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| DVFP | 1.1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| CSVD | 1.2 | 2 | 0.9 | 3 | ||||||||

| Groups not represented in parliament accounted for 100% of the votes missing. | ||||||||||||

National Socialism and the End of Prussia (1933–1947)

After Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor , Hermann Göring became Reich Commissioner for the Prussian Ministry of the Interior . Thus, when the National Socialists came to power, they had the executive power of the Prussian state government at their disposal. A few weeks later, on March 21, 1933, the so-called Potsdam Day took place. The newly elected Reichstag on March 5th was symbolically opened in the Potsdam Garrison Church , the burial place of the Prussian kings, in the presence of Reich President Paul von Hindenburg . The propaganda event, in which Hitler and the NSDAP celebrated “the marriage of old Prussia with young Germany”, was intended to win Prussian-monarchist and German-national circles for the National Socialist state and to get the conservatives in the Reichstag to approve the Enabling Act , which took place two days later decency.

Since 1933, the Reich government created the National Socialist unitary state by means of harmonization laws . The Reich Governor Act of April 7, 1933 and the Act on the Rebuilding of the Reich of January 30, 1934 did not formally dissolve the states, but deprived them of their independence. All state governments were placed under the control of Reich governors. An exception to this was Prussia, where, according to the law, the Reich Chancellor himself should exercise the "rights of the Reich Governor". However, as early as April 10, 1933, Hitler transferred the exercise of these rights to the Prussian Prime Minister Göring by decree . At the same time, the (party) districts became increasingly important for the implementation of national politics at the regional level. The Gauleiter were appointed by Hitler in his capacity as leader of the NSDAP . In Prussia, this anti-federalist policy went even further: since 1934, almost all of its state ministries have been amalgamated with the corresponding Reich ministries. Only the Prussian Ministry of Finance, the archive administration and a few other state authorities remained independent until 1945.

The spatial expansion of Prussia hardly changed between 1933 and 1945. In the course of the Greater Hamburg Act , there were even minor changes to the area. On April 1, 1937, Prussia was expanded to include the previously Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck . The Polish, formerly Prussian, areas annexed in the Second World War were predominantly not incorporated into the neighboring Prussia, but assigned to so-called Reichsgauen .

The Second World War ended in Europe on May 8, 1945. With the subsequent occupation of the Mürwik special area on May 23, the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein was completely occupied and the last government in the special area was arrested. After the end of National Socialist rule , Germany was divided into zones of occupation and its eastern territories incorporated across the newly established Oder-Neisse border, Poland and the Soviet Union. With this, the state of Prussia de facto ceased to exist in 1945 . De jure it still existed until its formal dissolution by the Control Council Act No. 46 of February 25, 1947. In it the Allied Control Council stated:

“The state of Prussia, which has always been the bearer of militarism and reaction in Germany, has in reality ceased to exist. Guided by the interest in maintaining the peace and security of the peoples and fulfilled by the desire to ensure the further restoration of political life in Germany on a democratic basis, the Control Council enacts the following law:

article 1

The state of Prussia, its central government and all subordinate authorities are hereby dissolved. "

Even before this law was passed, states had been formed across the board in the western occupation zone on what had been Prussian territory up to that point . After the decision of the Control Council, the dissolution of Prussia also continued in the Soviet zone of occupation: the provinces of Saxony (-Anhalt) and Brandenburg , which until then only existed as administrative units, were converted into states, and the addition "Western Pomerania" was derived from the name of the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania Removed in 1947, so that in official parlance z. B. Greifswalds were called "Mecklenburgers". In the same way, residents of the former Lower Silesian Upper Lusatia became "Saxons". At the same time, in the Soviet occupation zone and later in the GDR, the use of the terms "Pomerania" and "Silesia" for the parts of these former Prussian provinces that remained German was officially undesirable.

Legal successor to Prussia

The countries on the former territory of the State of Prussia are legal, especially state- and international law respects successor states of Prussia. For example, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia is bound by the Concordat that the Free State of Prussia concluded with the Holy See .

Traces of Prussia in the present

Despite the political dissolution of the Prussian state in 1947, many aspects have been preserved in everyday life , in culture or in sports and even in names. In the following areas, listed as examples, Prussia's still formative position becomes clear today:

Federation

- According to the prevailing view, the Federal Republic of Germany , as a subject of international law, is identical to the federal state initiated and dominated by Prussia , which was founded in 1867 under the name of the North German Confederation .

- Prussia's capital, Berlin , also became the capital of the newly founded empire in 1871 . The capital resolution of 1991, which designated Berlin as the federal capital of reunified Germany, the “ Berlin Republic ”, follows this tradition . Several federal institutions use building former Prussian institutions, the Federal Council as the formerly the Prussian mansion serving Federal Building . The Federal President has his first official residence in Bellevue Palace , the first classicist building in Prussia. As a means shield of national coat of arms in the gable above the main entrance is the Reichstag , the Prussian state emblem displayed.

- The constructive vote of no confidence anchored in the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany , which allows the head of government to be voted out only if a new successor is elected at the same time, goes back directly to a constitutional regulation of the Free State of Prussia.

- The Prussian war award of the Iron Cross is the symbol of the Bundeswehr in a modified form .

- The guard battalion at the Federal Ministry of Defense entered into the tradition of the 1st Guards Regiment on foot , which was introduced in 1806 as the body regiment of the King of Prussia .

- As part of state visits , in the reception with military honors the front of the pacing and Honor of the Guard Battalion of the Federal Ministry of Defense as a regular part of the diplomatic protocol of the federation of Präsentiermarsch Frederick William III. played.

- The Big Tattoo of the Bundeswehr, which is played especially when the Federal President, Federal Chancellors, Federal Defense Ministers and senior military officials say goodbye, consists largely of traditional elements of Prussian military music .

- The Police Star , the emblem of the Federal Police and the Military Police of the Armed Forces, is derived from the Prussian guard star from which the eight-rayed Breast Star of the Black Eagle declined. You can find the Gardestern on Schell trees of Bundeswehr - Music Corps .

countries

- The coat of arms of Saxony-Anhalt shows, among other things. the Prussian eagle .

- The large coat of arms of Baden-Württemberg contains the coat of arms of the Hohenzollern family .

- The Prussian model of government and administration was decisive for a large number of political institutions at the state level and is still expressed today in terms such as Prime Minister, administrative district, district administrator and district. Today's North Rhine-Westphalian landscape associations go back to the Prussian provincial associations .

- The Regional Association of Rhineland in North Rhine-Westphalia also carries the Prussian eagle in the upper part of its coat of arms - in continuation of the tradition of the Rhine Province and its provincial association.

- The countries on the former territory of the State of Prussia are legal, especially state- and international law respects successor states of Prussia. North Rhine-Westphalia, the largest successor state in Prussia, maintains its Prussian culture of history and remembrance in the form of the Prussian museums in Wesel and Minden .

Church associations

- The Union of Evangelical Churches emerged from the Evangelical Church of the Union , a church federation of the old Prussian Protestant regional churches , i. H. of the churches whose territory belonged to Prussia before 1866.

culture and education

- The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, supported by the federal and state governments, has brought together museums, collections, libraries, archives and other cultural assets of the former Prussian state since 1957. It looks after one of the largest and most universal collection complexes in the world, which also includes the Museum Island in Berlin.

- The Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg (SPSG) manages over 20 palaces and gardens from the Prussian era as well as large parts of the world cultural heritage of Potsdam's palace landscape and Charlottenburg Palace .

- The Prussian Sea Trade Foundation awards a.o. Scholarships for writers from Eastern Europe, supports research projects and book publications, gives purchase assistance for Berlin museums and awards the Berlin Theater Prize every year.

- Many universities and academies , which were founded or re-established by Brandenburg and Prussia since the 16th century, still exist today, including the Brandenburg University of Frankfurt , the Albertus University of Königsberg (1544, today the Baltic Federal University of Immanuel Kant ), the Friedrichs- University of Halle (1694), the Prussian Academy of the Arts (1694/1696, today the Academy of the Arts and University of the Arts Berlin ), the Berlin Building Academy (1799, merged with the Berlin Industrial Institute from 1821 from 1879 onwards, the Royal Technical University of Charlottenburg, today the Technical University Berlin ), the University of Berlin (1809, it incorporated the Bergakademie Berlin from 1770), the Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (1811), the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn (1818), the Art Academy Düsseldorf (1819), the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen (1870), the Royal Technical University of Hanover (1879, today the G Ottfried Wilhelm Leibniz University of Hanover ), the Westphalian Wilhelms University (1902), the Technical University of Danzig (1904) and the University of Cologne (1919).

Sports

- Club name (German): z. B. Preußen Münster or BFC Preussen

- Club name (Latin): z. B. Borussia Dortmund , Borussia Mönchengladbach , Borussia Neunkirchen , Tennis Borussia Berlin , Borussia Düsseldorf or Borussia Fulda

- In addition, the German national soccer teams and many other athletes are mostly dressed in the Prussian national colors black and white.

Place names

- City of Preußisch Oldendorf in the Minden-Lübbecke district

- Village Prussian Ströhen (district of the city Rahden ) in the Minden-Lübbecke

- Prussia station in Horstmar along with the Prussia – Münster railway line and the former Prussia colliery and Preußenhafen in Lünen, near Dortmund

- Kohlhof , a district of Neunkirchen (Saar) , was formerly called Preußisch Kohlhof , as a demarcation to the neighboring town of Bayerisch Kohlhof

Student associations

Chilean Armed Forces

- The armed forces of Chile adopted numerous Prussian military traditions after bringing German military advisers into the country after the Saltpeter War. The most important reformer of the Chilean army was the Saxon captain Emil Körner , who headed the military mission from 1885 and served as commander in chief of the Chilean army for ten years from 1900 until his retirement. The reconstruction of the Chilean army based on the German model is called "Prussianization" ( Spanish : prusianización ). The most noticeable signs include the uniforms of the army and navy, which were introduced in 1903 and are still maintained today, very closely based on the Prussian model with pimple hood and scabbard , the completely adopted Prussian drill regulations with goose- step and parade bush as well as several military songs and marches from the army march collection that have been translated into Spanish .

vocabulary

- The Berlin blue pigment is also known as Prussian blue.

- The English name for the spruce , spruce , is derived from the Polish z Prus ("from Prussia").

characteristics

Special features of the Prussian state

The state formation of Prussia differs significantly from that of other European powers such as France or England. The kingdom that emerged in 1701 was not a product of an established culture or a consequence of the historical development of a people. Since its areas were widely scattered, another important incentive for a natural state-building process was missing, namely the organization and combination ( synergy ) of geographically coherent areas. Thus the Prussian state was exclusively an expression of the will to power of its elites.

In other historically grown states, so one thesis, these adapted to the needs of society. In Prussia, on the other hand, where the prerequisites for becoming a state were completely lacking, the state had shaped society according to its needs. The result was a well-organized administrative and ruling apparatus, which was superior to its neighbors for several centuries due to its abundance of power and organizational ability and thus established the success of this “Prussian state model ”. In the North German Confederation (from July 1, 1867) and then in the German Empire (from January 1, 1871), the Prussian administration worked in the federal state. Conversely, the close connection between the Reich authorities and the Prussian authorities also led to the “attainment” of Prussia. Ernst Rudolf Huber sums up:

“The development of the Reich into a real state depended crucially on its gaining a body of officials who were distinguished not only by technical proficiency but also by the ability to politically integrate the Reich. [...] In the service of the central Reich offices, which were created in quick succession, a civil servant body was developed which was directly integrated into the Reich, whose loyalty to duty and performance was on par with the much-vaunted Prussian civil servants, the Prussian open-mindedness for administrative tasks and constitutional problems of modern times Officials but surpassed. "

The federal officials and then the Reich officials came mainly from the Prussian civil servants and judges. There were as yet no separate training courses for the federal government or the Reich. With all loyalty to the empire and the emperor, so Huber, there was a critical awareness.

Protestant liberalism

Since the Reformation , Prussia had a predominantly Protestant population. Compared to neighboring states, which were more strongly influenced by Catholicism , Prussia was considered to be relatively 'liberal' in matters of religious practice. The latter was particularly true of the reigns of Friedrich Wilhelm I , who settled the Salzburg exiles , Protestant religious refugees, in Prussia, and Frederick the Great , who took the view that every citizen should have the opportunity "to be saved in his own way" . Religious minorities persecuted in neighboring countries sought protection in Prussia, other minorities remained unmolested here. During the census at the end of 1840, 194,558 Jews were counted in Prussia.

"Prussian Spirit"

The Prussian state model was based on a special form of ethics, which is commonly summarized as the Prussian spirit and has entered into the formation of legends. So one connects with Prussia on the one hand the stereotypes of the Prussian virtues shaped by Protestant values such as reliability , thrift , modesty , honesty , diligence and tolerance . The opposite stereotype points to militarism , authoritarianism , aggressive imperialism and a fundamentally anti-democratic and reactionary politics. Prussia fought fewer wars than France and England, for example. The deterministic historical image created by Prussian historians in the 19th century that Prussia had a historical mission in Germany and the world was condemned as Borussianism as early as the 19th century .

Christopher Clark notes for the first half of the 19th century that around sixteen times as many people were executed annually in England and Wales as in the comparably large Prussia. Whereas in Prussia the death penalty was almost exclusively imposed on murderers, in England this penalty was also given for property crimes, some of which were minor. "The British tolerated state violence to an extent that would have been unthinkable in Prussia." The misery of the poor in Prussia in the 1840s lags behind the Irish famine under British rule. "If the Poles in Prussia had been carried away by a comparable famine, we might see them today as harbingers of Nazi rule after 1939."

Today's image of Prussia in historical studies is far more differentiated than both stereotypes, the latter of which, however, as shown below, appears to be necessary as the founding myth of the Federal Republic of Germany; reference is made to the complexity and long historical development of this state.

“[Prussia and National Socialism stand] in absolute opposition. Prussia stands for the sovereignty of the state, for the idea that the state absorbs the entire interests of civil society. This was inconceivable for the Nazis, they wanted to replace the state with a national entity. […] The Sonderweg thesis was fruitful because the brightest minds have dealt with it. And it served a popular educational purpose, because it made it possible to lump various problem complexes such as militarism, the cult of obedience, and belief in authority about the term Prussia together with National Socialism. That made the emergence of a liberal Federal Republic easier. But now it's time to ask other questions and make room for new perspectives. "

State symbols

The national colors of Prussia, black and white, are already included in the Hohenzollern family coat of arms. The heraldic animal of Prussia is the black Prussian eagle . Since the Reformation, the coat of arms has been Suum cuique - " To each his own ". The Prussian song was for a time the unofficial national anthem of Prussia.

See also

- History of Germany

- List of the provinces of Prussia , list of the districts of Prussia , list of the urban districts of Prussia

- Prussian coin history

- Prussian State Ministry , State Chancellor (Prussia) , List of Prussian Prime Ministers , Oberpräsident

- Prussian State Council (1817-1918)

- Prussian State Council (1921–1933)

- Prussian State Council (from 1933)

- Prussian Constitution (1848/1850) , Prussian Higher Administrative Court

- Administrative division of Prussia

- Tombs of European monarchs # Prussia

- Extrusion

- Motor vehicle flags of Prussia (1925-1935)

Source editions and older representations

- Acta Borussica.

- General archive for the history of the Prussian state. (Leopold v. Ledebur, ed.). First volume, Mittler, Berlin / Posen / Bromberg 1830, 390 pages .

- Alexander Miruss: Clear presentation of the Prussian state law together with a short history of the development of the Prussian monarchy. Herbig, Berlin 1833 ( digitized version )

- Theodor Hirsch , Friedrich August Vossberg : Caspar Weinreich's Danziger Chronik. A contribution to the history of Danzig, the lands of Prussia and Poland, the Hansabund and the Nordic empires . Berlin 1855 ( e-copy ).

-

Albert Ludwig Ewald : The Conquest of Prussia by the Germans (four volumes; 1872 to 1886)

- Volume 1: Appointment and Foundation . Hall 1872 ( books.google.de )

- Volume 2: The first uprising of the Prussians and the fighting with Swantopolk . Hall 1875 ( books.google.de )

- Volume 3: The conquest of the Samland, the eastern Natangens, eastern Bartens and Galindens . Halle 1884 (reprint, limited preview ).

- Volume 4: The great uprising of the Prussians and the conquest of the eastern landscapes. With an orientation map . Hall 1886.

- Max Toeppen : Historical-comparative geography of Prussia. Gotha 1858, 398 pages .

- Scriptores rerum Prussicarum - The historical sources of the Prussian prehistoric times. (Theodor Hirsch, Max Toeppen and Ernst Strehlke, eds.), With annotations in German, five volumes (1861–1874), volume 1 , volume 2 , volume 3 .

- The Prussian state legislation - collection of text editions. ( Max Apt , ed.). Bookstore of the orphanage, Halle / S. and Berlin 1933–1935. About 14 volumes (with supplements).

literature

- Hans Bentzien : Under the red and black eagles. History of Brandenburg-Prussia for everyone . Volk & Welt publishing house, Berlin 1992, ISBN 978-3-353-00897-8 .

- Dirk Blasius (ed.): Prussia in German history . Verlagsgruppe Athenäum, Hain, Scriptor, Hanstein, Königstein / Taunus 1980, ISBN 3-445-02062-0 .

-

Otto Büsch (ed.): Handbook of Prussian History , ed. on behalf of the Historical Commission in Berlin:

- Volume 1: Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): The 17th and 18th centuries and major topics in the history of Prussia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-014091-0 .

- Volume 2: Otto Büsch (Ed.): The 19th century and major topics in the history of Prussia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, ISBN 3-11-008322-1 .

- Volume 3: Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): From the Empire to the 20th century and major topics in the history of Prussia. Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-014092-6 .

- Christopher Clark : Prussia. Rise and fall 1600–1947 . bpb 2007, ISBN 978-3-89331-786-8 .

-

Felix Eberty : History of the Prussian State. 7 volumes. Breslau 1867–1873.

- Volume 1: 1411-1688 . Breslau 1867 ( books.google.de ).

- Volume 2: 1688-1740 . Breslau 1868 ( books.google.de ).

- Volume 3: 1740-1756 . Breslau 1868 ( books.google.de ).

- Volume 4: 1756-1763 . Breslau 1869 ( books.google.de ).

- Heinrich Gerlach : Only the name remained. Splendor and fall of the old Prussians. Econ, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1978, ISBN 3-430-13183-9 .

- Oswald Hauser (Ed.): Prussia, Europe and the Reich (= New Research on Brandenburg-Prussian History. Volume 7). Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 1987, ISBN 3-412-05186-1 .

- Gerd Heinrich : History of Prussia. State and dynasty. Propylaea, Frankfurt and others 1981, ISBN 3-549-07620-7 .

- Klaus Herdepe : The Prussian Constitutional Question 1848 . ars et unitas, Neuried 2003 (German University Edition , Volume 22), ISBN 3-936117-22-5 .

- Otto Hintze : The Hohenzollern and their work - five hundred years of patriotic history (1415-1915). Verlag Paul Parey, Berlin 1915. (Reprint of the original edition: Hamburg / Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-490-33515-5 )

- Reinhart Koselleck : Prussia between reform and revolution. General land law, administration and social movement from 1791 to 1848 . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-608-95483-X .

- Wolfgang Neugebauer: The history of Prussia. From the beginning until 1947 . Piper, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-492-24355-X .

- Uwe A. Oster: Prussia. Story of a kingdom . Piper, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-492-05191-0 .

-

Prussia. Attempt to take stock . Five-volume catalog for the exhibition of the same name at the Berlin Festival from August 15 to November 15, 1981 in the Gropius-Bau in Berlin, Rowohlt, Reinbek 1981.

- Volume 1 Prussia. Attempt to take stock . Edited by Gottfried Korff. 1981, ISBN 3-499-34001-1 .

- Volume 2 Prussia. Contributions to a political culture . Edited by Manfred Schlenke. 1981, ISBN 3-499-34002-X .

- Volume 3 Prussia. On the social history of a state . Arranged by Peter Brandt. 1981, ISBN 3-499-34003-8 .

- Volume 4 Prussia. Your Athens on the Spree. Contributions to literature, theater and music in Berlin . Edited by Hellmut Kühn. 1981, ISBN 3-499-34004-6 .

- Volume 5 Prussia in the film. A retrospective of the Deutsche Kinemathek Foundation . Edited by Axel Marquardt and Heinz Rathsack. 1981, ISBN 3-499-34005-4 .

- Julius H. Schoeps : Prussia, history of a myth . 2nd ext. Edition, Bebra Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-89809-030-2 .

- Eberhard Straub : A little history of Prussia . Siedler, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88680-723-1 .

- Wolfgang Wippermann : Prussia. Small story of a great myth . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2011, ISBN 978-3-451-30475-0 .

Web links

- Prussia - Chronicle of a German State (website for the ARD series in the "Prussian Year" 2001)

- Constitutional document for the Prussian state ("Obligated Constitution" of December 5, 1848) in full text

- Constitutional document for the Prussian state ("Revised Constitution" of January 31, 1850) in full text

- Maps of the history of Prussia

- Collection of historical maps on Prussian / German-Polish history

- Preussenschlag, takeover of the government of the German Historical Museum

- Control Council Act No. 46 - the formal dissolution of Prussia

- Preussenmuseum.de - Prussia Museum of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia in Wesel and Minden

- Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg

- Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans-Joachim Schoeps: Prussia. History of a state. Berlin 1992, p. 13 f.

- ↑ Janusz Małłek: The presentation of the stands in the Teutonic Order (1466–1525) and in the Duchy of Prussia (1525–1566 / 68). In: Hartmut Boockmann: The beginnings of the corporate representations in Prussia and its neighboring countries . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-486-55840-4 , p. 101.

- ↑ Oswald Hauser : The spiritual Prussia . Kiel 1985

- ↑ Christopher Clark : Prussia. Rise and fall. 1600-1947 . DVA, Munich 2007, p. 105

- ^ Hugo Rachel: Mercantilism in Brandenburg-Prussia. In: Otto Büsch, Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): Modern Prussian History. Volume 2, pp. 951 ff.

- ↑ Klaus Schwieger describes the effects: Military and bourgeoisie. On the social impact of the Prussian military system in the 18th century. In: Dirk Blasius (Ed.): Prussia in German history. Koenigstein / Ts. 1980, p. 179 ff.

- ↑ Christopher Clark : Prussia. Rise and fall. 1600-1947. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-05392-3 , p. 186.

- ^ Klaus Zernack: Friedrich, Russia and Poland. In: Wilhelm Treue (Ed.): Prussia's great king. Freiburg / Würzburg, 1986, p. 197 ff.

- ^ Horst Möller : Princely State or Citizens' Nation. Germany 1763-1815. Siedler, Berlin 1989, especially chap. I From Austro-Prussian dualism to revolutionary challenge. Pp. 13-64.

- ↑ Christopher Clark : Prussia. Rise and fall. 1600-1947. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-05392-3 , p. 333.

- ^ Georg Kotowski: Wilhelm von Humboldt and the German University. In: Otto Büsch, Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): Modern Prussian History. Volume 3, pp. 1346 ff.

- ↑ Gordon A. Craig: Stein, Scharnhorst and the Prussian reforms. In: Ders .: The Prussian-German Army 1640–1945. State within the state. Düsseldorf 1960, pp. 56-72.

- ↑ For a historical perspective from the imperial era, see Otto Hintze : The monarchical principle and the constitutional constitution (first published in 1911). In: Otto Büsch, Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): Modern Prussian History. Volume 2, p. 731 ff.

- ^ Siegfried Schindelmeiser: The Albertina and its students 1544 to WS 1850/51. Volume 1 of the two-volume new edition, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-028704-6 .

- ↑ See Thomas Nipperdey: Deutsche Geschichte 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state . Beck, Munich 1998, Chapter III Restoration and Vormärz 1815–1848 , pp. 272–402, especially the section Prussia. P. 331 ff.

- ^ Richard H. Tilly: The political economy of financial policy and the industrialization of Prussia, 1815-1866. In: Dirk Blasius (Ed.): Prussia in German history. Koenigstein / Ts. 1980, p. 203 ff.

- ^ William Otto Henderson: Prussia and the Founding of the German Zollverein. In: Otto Büsch, Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): Modern Prussian History. Volume 2, p. 1088 ff.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart and others. 1988, pp. 924/925.

- ↑ Jürgen Angelow: The German Confederation. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Georg Franz-Willing: The great conflict: Kulturkampf in Prussia. In: Otto Büsch, Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): Modern Prussian History. Volume 3, pp. 1395 ff.

- ^ Hajo Holborn : Prussia and the Weimar Republic. In: Otto Büsch, Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): Modern Prussian History. Volume 3, p. 1593 ff.

- ↑ Christopher Clark : Prussia. Rise and fall. 1600-1947. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-05392-3 , p. 730.

- ↑ Hagen Schulze: Prussia as a factor of stability in the German republic. In: Dirk Blasius (Ed.): Prussia in German history. Koenigstein / Ts. 1980, p. 311 ff.

- ↑ Golo Mann describes the various stages of transformation and dissolution of old Prussia between 1871 and 1947 : The end of Prussia. In: Hans-Joachim Netzer (Ed.): Prussia. Portrait of a political culture. Munich 1968, pp. 135-165. See also from a different perspective Andreas Lawaty : The end of Prussia from a Polish perspective: On the continuity of negative effects of Prussian history on German-Polish relations . de Gruyter, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-11-009936-5 .

- ↑ Control Council Act No. 46 of February 25, 1947

- ↑ Dissolution of the State of Prussia ( Memento from August 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ^ BGH, judgment of January 31, 1955, Az. II ZR 234/53, full text .

- ^ The history of Bellevue Palace , website in the portal bundespraesident.de (2013), accessed on December 6, 2013.

- ^ Presentation march of Friedrich Wilhelm III. on YouTube , accessed November 12, 2010.

- ^ Markus Reiners: Administrative structural reforms in the German federal states. Radical reforms at the level of the central government . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15774-0 , p. 162 ( online )

- ↑ Stefan Rinke: A spiked bonnet doesn't make a Prussian. Prussian-German military adviser, military ethos and modernization in Chile. 1886-1973. In: Sandra Carreras, Günther Maihold (Ed.): Prussia and Latin America. In the field of tension between commerce, power and culture. Münster 2004, pp. 259–283.

- ↑ Prussian Year Book - An Almanach . MD Berlin, Berlin 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume IV: Structure and crises of the empire . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1969, p. 129.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 966/967.