Leopold I. (HRR)

Leopold I (born June 9, 1640 in Vienna ; † May 5, 1705 ibid), VI. from the House of Habsburg , born Leopold Ignaz Joseph Balthasar Franz Felician , was from 1658 to 1705 Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and King in Germania (from 1654), Hungary (from 1655), Bohemia (from 1656), Croatia and Slavonia (from 1657). In terms of power politics, his reign in the West was dominated by the defense against French expansion under Louis XIV.In the southeast, the Habsburg territories were initially threatened by the Ottoman expansion at the height of the Second Siege of Vienna . The imperial generals were ultimately militarily successful and a counter-offensive ensued, which led to the profit of all of Hungary. As a result, the Habsburg sphere of influence grew even more than before beyond the Holy Roman Empire. Leopold's reign is therefore also considered to be the beginning of the great power position of the Habsburg monarchy . Domestically, Leopold relied on an absolutist style of rule in the Habsburg lands . The last climax of the Counter-Reformation also fell during his time . In the empire, on the other hand, he acted as the guardian of the balance between denominations. Through a skilful policy he succeeded in making the empire dominate for the last time. The death of the last Spanish king from the House of Habsburg, Charles II , led to the War of the Spanish Succession , in which Leopold represented the succession of his family.

Origin and family

He was the son of Emperor Ferdinand III. (1608–1657) and the Spanish Infanta Maria Anna . His older brother was Ferdinand, who later became Ferdinand IV. His sister Maria Anna was married to King Philip IV of Spain. His half-sister Eleanor married King Michael of Poland and later Duke Charles V of Lorraine . His half-sister Maria Anna Josepha was the wife of the Duke of Jülich-Berg and later Elector of the Palatinate, Jan Wellem , whose sister Eleonore Leopold married in his third marriage. His paternal grandfather, Emperor Ferdinand II , married to Maria Anna of Bavaria , and his maternal grandmother, Margaret of Austria , wife of King Philip III of Spain . , were siblings.

He had close family ties with Louis XIV, who was almost the same age, and his lifelong rival. They were cousins to their Spanish mothers and soon were brothers-in-law to their respective Spanish wives.

He was short in stature, rather ugly, and had a very pronounced Habsburg lower lip . As the emperor's second son, Leopold was originally intended for a spiritual career. He was to become Bishop of Passau . Hence, he received an excellent education. He received his education from Johann Ferdinand Graf Porzia and the Jesuits Christoph Miller and Johann Eberhard Neidhardt . His upbringing shaped a baroque Catholicism in him. At first he also had strong counter-Reformation tendencies.

Takeover

After the surprising death of his older brother Ferdinand in 1654, who as Ferdinand IV had been Roman-German King and King of Hungary and Bohemia , Leopold became his heir at the age of only fourteen. Sole heir to the Habsburg hereditary lands he was 1654. On June 27, 1655, he was in St. Martin to Bratislava for Apostolic King of Hungary , and on September 14, 1656 in St. Vitus Cathedral at Prague to the King of Bohemia crowned.

The succession in the empire turned out to be much more difficult. The French minister Mazarin brought a candidacy of Louis XIV into play. To do this, he ran an expensive and elaborate advertisement in the empire. There was also talk of a Bavarian and even a Protestant candidacy (Sweden, Kurbrandenburg , Electoral Saxony or Electoral Palatinate ). On the other hand, there was hardly any talk of a Habsburg empire. After the death of his father (1657) the question had to be resolved. An interregnum began which, with a duration of one year, was one of the longest in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

It was only after lengthy negotiations with the elector that Leopold was able to prevail against the French King Louis XIV and his candidates, Duke Philipp Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg, as well as Archduke Leopold Wilhelm and Elector Ferdinand Maria of Bavaria , who had also expressed their interest. The election took place on July 18 and the coronation on August 1, 1658 in the Imperial Cathedral of St. Bartholomew in Frankfurt.

Imperial Court

The emperor relied mainly on the court. In winter Leopold spent most of the time in the Hofburg in Vienna. He spent spring in Laxenburg , summer in Favorita and autumn at Schloss Kaiserebersdorf .

The court, in turn, was closely linked to the central authorities. It was shaped by the high aristocracy from Austria and Bohemia. Similar to the court in Versailles , it was supposed to attract the high nobility. The government agencies and the military also offered attractive positions to attract the imperial nobility to Vienna. The court followed the Spanish court ceremony. The baroque splendor unfolded in large festivals. In 1672 the court, including the central government authorities, comprised 1966 people. A hundred years earlier there were only 531 people. In the same time the costs had quintupled.

In the course of his first marriage on December 12, 1666 to Margarita Theresa of Spain , a festive dance began that lasted almost a year. On the occasion of the Empress's birthday, the opera “Il Pomo d'oro” (the golden apple) by Antonio Cesti was premiered for five hours each on July 12 and 13, 1668. For this "festa teatrale" a special comedy house was built based on the example of Venice. The opera itself was a high point of baroque culture. In addition to Antonio Cesti, several well-known composers such as Johann Heinrich Schmelzer and the Kaiser himself, who set two scenes to music, as well as the librettist Francesco Sbarra and others were involved. At the same time, the opera was an example of the pomp and waste of time. The opera cost a total of 100,000 guilders.

Like the emperor himself, the imperial court was shaped by the Catholic spirit. Apparently the emperor had no extramarital affairs. There were no mistresses like at the French court. Various clergymen had a strong influence, such as the Jesuit and later Bishop Emerich Sinelli , the Capuchin Marco d'Aviano , the Franciscan Christoph de Royas y Spinola and the Augustinian Abraham a Sancta Clara . Marco d'Aviano preached successfully mobilizing in the spirit of the old crusades during the Turkish wars since 1683 .

Various court parties were formed at the imperial court, trying to influence the emperor's politics. Between them there were endless intrigues, conflicts and rapidly changing alliances.

Government style

Little trained politically, he left the affairs of state to experienced advisors until the beginning of the 1680s. Initially, his former tutor, Porzia, was first minister. It was followed by Johann Weikhard Prince of Auersperg (1615–1677) and the President of the Court Councilor Wenzel Eusebius, Prince Lobkowitz (1609–1677). Auersperg was overthrown as the leading minister in 1669. In 1674 Lobkowitz also lost his post. Both had established connections with France without the knowledge of the emperor.

Since then the emperor himself has determined the guidelines of politics. There were no more senior ministers. The Chancellor Johann Paul Hocher (1616–1683) and his successors were civil climbers. An important diplomatic helper in the policy against France was Franz von Lisola . The financial situation was a constant problem. It was significant that the President of the Court Chamber, Georg Ludwig von Sinzendorf, was overthrown for embezzlement. A stabilization of the finances succeeded under Gundaker Graf Starhemberg . Reich Vice Chancellor Leopold Wilhelm von Königsegg-Rothenfels and previously Wilderich von Walderdorff played important roles in the background. Since the Secret Council was barely functional due to the large number of members , Leopold had the Secret Conference set up as a predominantly foreign policy advisory body . Technical commissions were also set up later. His government activities could be compared with the manner of Louis XIV.

In Leopold's time, the development and establishment of an imperial embassy system at the courts of the most important imperial estates and the imperial circles . The imperial principal commissioner and the Austrian embassy to the Reichstag played an important role . It was also positive that the Reichshof Chancellery and the Austrian Court Chancellery tended to work together and not get lost in the dispute over competencies.

While after the first few years Leopold had essentially determined the direction of politics himself, the “war party” around Eugene of Savoy and the later Emperor Joseph succeeded in largely pushing Leopold into the background in recent years.

His motto was: consilio et industria = through advice and diligence [sc. to the goal]

Domestic Policy in the Habsburg Lands

Absolutism and its limits

Domestically, Leopold's reign in the Habsburg countries was absolutist. The absolutism Leopold was dominated ecclesiastical and courtly and aimed less at building a central administration. In this respect the hereditary lands fell behind against Brandenburg-Prussia . The connection between church and state found its expression, among other things, in the fact that the emperor named St. Leopold III. made the Austrian patron saint. His trips to Klosterneuburg resembled state pilgrimages after 1663 . The absolutist tendencies also had their limits. In this way, the corporate bodies were able to assert themselves in the various Habsburg areas.

It was also important that in his reign, after the death of Prince Sigismund Franz , Tyrol and the foreland fell to the emperor in 1665. This once again strengthened his position in imperial politics. The attack from Tyrol, which had previously been ruled by a Habsburg branch line , to the main line of the house, was significantly promoted by the second marriage of the emperor to Claudia Felizitas of Austria-Tyrol .

Economic and social policy

From a social point of view, the pressure of the noble landlords on the peasants increased. The emperor tried, for example, to intervene through the “Tractatus de iuribus incorporalibus” of 1679. Until 1848 it formed the basis for the relationship between the landlords and farmers. For the farmers it brought better legal security, at the same time the landlords could still demand unlimited robot work. To combat the growing number of the poor in the city of Vienna, Leopold had a breeding and work house built in 1671. In addition, a large poor house was built in 1691. In 1696, 1,000 people were accommodated there. The plague wave of 1678/79 , which is said to have claimed 50,000 victims in Vienna alone , also fell during Leopold's time .

On the other hand, under the sign of mercantilism, the first manufactories were founded. A first oriental trading company quickly disappeared. With the Commerce College, a central economic organization was created in 1666. This was responsible for the supervision of trade, trade and customs. Officials and representatives of the merchants belonged to the institution. It became a model for comparable organizations in other German territories.

Counter-Reformation and Jewish Policy

Leopold pursued a counter-Reformation policy aimed at suppressing Protestantism, which was particularly strong in Hungary. Sometimes handled differently by the regional authorities and estates, pressure was exerted on the remaining Protestants in all Habsburg countries to convert to Catholicism. In Bohemia, Protestantism could only survive underground. In Silesia the number of Protestant places of worship had fallen to 220 by 1700, while their number had been 1,400 by 1600. It was only at the end of Leopold's reign that the pressure on the Protestants eased a little . to strengthen again.

Jewish financiers and court Jews , especially from Frankfurt, such as Samuel Oppenheimer and Samson Wertheimer , played an important role in financing the wars . This was in contrast to his anti-Jewish policies in the hereditary countries. The expulsion of the Jews from Vienna in 1670/71 belongs to this context . The once flourishing community in Vienna was located in Unteren Werd on the other side of the city wall. She was expelled from the country ( gesera ), and as a thank you, the Viennese people renamed the area Leopoldstadt in honor of the emperor, today's 2nd district of Vienna. Paul I, Prince Esterházy , settled some expelled Jews in the seven communities around Eisenstadt . Others were brought to Berlin by the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm , where they helped rebuild the country devastated by the Thirty Years' War and founded a flourishing Jewish community .

The collapse of Samuel Oppenheimer's bank in 1703 in the wake of anti-Semitic riots led to national bankruptcy. The state reacted by founding a state bank "Banco del Giro" and issuing a first form of paper money ("Giro-Zeddel"). The bank was not very successful and was handed over to the City of Vienna in 1705. The "Wiener Stadtbank" emerged from it

Robot riots in Bohemia

Bohemia suffered from the high tax demands from Vienna. These were passed on from the landlords to the farmers. Then there were the plague epidemics and the relentless policy of recatholization. When the emperor came to Bohemia in 1679, he received numerous complaints. After the emperor left the country, numerous applicants were arrested. Everything together led to a great peasant uprising in March 1680, which affected large parts of Bohemia. Only at the end of May was it possible to restore the calm by means of armed force. Many participants in the uprising were executed, sentenced to forced labor or imprisonment.

On the other hand, Leopold responded with a robot patent issued in 1680 . This Pardubitzer Pragmatica reorganized the relationship between the landlords and the farmers and stipulated, among other things, that the burden of robot work for the landlord was limited to three days a week. However, the decree was hardly heeded by the landlords, as early as 1680 and later there were repeated unrest.

Clashes in Hungary

In Hungary the absolutist form of rule, the counter-reformation measures and also the shameful peace of Vasvár from 1664/1666 to 1671 led to a magnate conspiracy . The leaders of the conspiracy were executed in 1671 after the emperor had previously hesitated. The emperor now tried to abolish the estate rights in Hungary and pursued a strictly anti-Protestant course. A gubernium established in 1673 under the German master Johann Caspar von Ampringen pursued a policy of Germanization. The Hungarian opposition could not eliminate all of this. Since an alliance between the Hungarians and the Turks could not be ruled out, Leopold was ultimately forced to give in. Leopold had to restore the rights of the estate and in 1681 even granted the Protestants a limited right to practice their religion.

After the victory over the Ottomans in 1683, Leopold tried to pursue anti-Protestant and absolutist politics in Hungary again. The harshness of the governor Antonio von Caraffa increased the Hungarian counter-movement. Leopold apparently gave in and tried to win the Hungarian nobility to strengthen the royal position. This also included the abandonment of the counter-Reformation course. In fact, he succeeded in weakening the rights of the class to have a say. The nobility also renounced their right of resistance, which had been documented since the Middle Ages. In 1687 Archduke Joseph was crowned King of Hungary on this changed legal basis. In addition, against the background of the imperial victory in the battle of Mohács , the Hungarian assembly of estates agreed to transfer the Hungarian royal dignity to the House of Habsburg hereditary.

Transylvania fell to Habsburg in 1697 after it had been militarily secured in 1688. In this case, however, Leopold recognized the previous rights of the residents and religions. In an imperial diploma from 1691, the country regained its old constitution and the political autonomy of nations.

The territorial gains after the conquest of Belgrade across the Sava River in 1688 were lost again in 1690, while the Hungarian acquisitions could be maintained. In the Treaty of Karlowitz of 1699, the Ottoman Empire renounced Hungary and Transylvania and most of Slavonia.

Leopold encouraged immigration throughout Hungary, even from Orthodox Serbs and Albanians. With the facility of 1689 he supported the resettlement, especially with Germans, later called (Danube) Swabians .

In connection with the War of the Spanish Succession , there was another uprising in Hungary in 1701. This new Kuruc uprising , led by Franz II Rákóczi , tied up strong military forces that were lacking elsewhere. At times, troops of the insurgents even threatened Vienna.

Imperial politics

Election surrender and First Rhine Confederation

With regard to his role as Holy Roman Emperor, it was a difficult start. He had to sign an election surrender that was marked by the weakness of the empire after the end of the Thirty Years' War . Even in terms of foreign policy, he was tightly shackled by the electors, who were responsible for the formulation. After that he was not allowed to support the enemies of France, meaning Habsburg Spain, which was at war against Louis XIV. If the Peace of Westphalia granted all imperial estates the right of alliance, this was restricted to the head of the empire of all people.

The First Rhine Confederation had been directed against the emperor since 1658 , in which many important imperial estates were linked with France and Sweden. On the French side, the covenant was the work of Cardinal Jules Mazarin , who headed the government for Louis XIV, who was not yet of age. On the part of the imperial estates, the Elector of Mainz, Johann Philipp von Schönborn, played an important role. This sought to weaken the imperial influence and a stronger class-based order in the empire. France was the protector of the Confederation of the Rhine. The aim was to preserve the principles of the Peace of Westphalia . But it was also important to keep the Austrian Habsburgs out of the Spanish-French War and the Northern War . However, the Rhine Confederation did not succeed in becoming a significant power factor. In terms of foreign policy, with the peace agreement between France and Spain, an occasion no longer existed, and domestically, with the convening of a Reichstag in Regensburg, the estates were given a forum for a say again.

France's urge to expand towards the Rhine during the personal rule of Louis XIV meant that France lost support from most of the imperial estates. The Rhine Confederation was no longer extended around 1668. The threat posed by the Ottomans in the east and France in the west led the imperial estates to lean more closely back to the emperor.

Denominational politics

While under the Catholic, personally pious Leopold in his hereditary countries, and especially in Hungary, there was a final climax of the Counter-Reformation, he acted much more cautiously in the empire. He adhered to the equality of denominations prescribed by the Peace of Westphalia. He did not question the religious peace that had been renewed in Osnabrück . He himself appeared more and more as the guardian and defender of the Peace of Westphalia.

Marriage and clientele policy

The emperor turned to the imperial estates through various measures, in particular through a corresponding marriage policy . The members of the House of Habsburg were married in the way that best served the emperor's policy. He himself married Eleonore Magdalene von Pfalz-Neuburg for the third time in 1676 . His eldest son Joseph took Wilhelmine Amalie von Braunschweig-Lüneburg as his wife. Two leading houses of the anti-Habsburg princes were connected to the imperial family. With the elevation of Ernst August von Braunschweig-Calenberg to the rank of elector , he wanted to further strengthen the support of the Guelphs .

Leopold succeeded in orienting most of the imperial estates back to Vienna. This applies to the Palatinate and Guelphs, partly also to the Brandenburgers. Leopold made it possible for Frederick I to call himself King in Prussia for his territory that was not part of the empire . He supported the Elector of Saxony Friedrich August I in becoming King of Poland. Especially in the case of smaller imperial estates, Leopold endeavored to enlarge the imperial clientele, particularly by raising the rank of rank and conferring titles. The elevation of the East Frisian family Cirksena or the Fürstenberger to the rank of prince, with corresponding seats in the Reichstag, increased Leopold's following in the empire. In the spiritual states, Leopold tried to fill them with people loyal to the Habsburg castle.

In order to dissuade the princes from federalist ambitions in the empire, Leopold strengthened the less powerful classes through his clientele policy. Imperial knights and imperial cities were subordinate to him anyway, the other smaller estates saw in him the patron of the larger estates. Against the princes, he also strengthened the estates and their right of tax approval.

He also achieved greater support for the imperial estates through his endeavor to no longer govern autocratically or only with the help of the electors like his immediate predecessors. He acted as a referee in relation to the different, sometimes competing groups. Despite the rivalry among the major imperial estates, Leopold, supported by his supporters in the imperial estates, always remained in control of the situation in the empire.

Of lasting importance was that Leopold registered increasing political interests in the former imperial Italy . At that time, however, Habsburg did not succeed in taking over the Duchy of Milan against Spain and France .

Relationship with the electors

The problem for him was that the electors at the height of Louis XIV's reunion policy were not on his side. The French king had brought the Brandenburg citizen on his side with subsidy payments . Due to their proximity to the French border, Ludwig XIV was able to successfully exert pressure on the electors of Mainz , Cologne and the Palatinate . His attempt to politically upgrade the Bohemian electoral dignity he had led, which so far only played a role in the election of a king, led to the formation of oppositional Kurvereine in 1683 and 1695. The problematic relationship with the electors improved with the generation change in these areas, which Leopold achieved through the aforementioned marriage policy and privileged measures. At the end of his reign, the secular Kurhöfe were, at least temporarily, bound to the Hofburg. In the War of the Spanish Succession , however, the Bavarian Elector Max Emanuel and his brother Elector Joseph Clemens of Cologne pulled out again and supported France.

Perpetual Reichstag

A structural change in the Reich was the further development of the Reichstag convened in Regensburg on January 20, 1663 to become the Perpetual Reichstag . The permanence of the Reichstag was not planned. It was initially called up to approve funds for the Turkish wars. In addition, a variety of issues were negotiated, which eventually led to the Reichstag staying together. In addition to financial issues, the constitution of the empire itself was up for debate. There was, for example, the dispute over the election surrender. Should this continue to be worked out by the electors or should other imperial estates also be involved? Should a new electoral capitulation be worked out with every change of the throne or would one work out a long-term one? These and similar questions could not be clarified, which ultimately led to the fact that the Reichstag no longer parted. The Perpetual Reichstag harmed the Kurkollegium, as there was no longer a Reichstag-free period in which the electoral days could fill the gap. Overall, the development towards the Perpetual Reichstag was the most important development in the political structure of the Reich in Leopold's time. At first he was rather skeptical about this, but later this development became important for strengthening his rule. The increase in importance of the Reichstag did not weaken the Kaiser, as some feared and others hoped, but supported him in the Reich. Through the perpetual Reichstag, Leopold was able to influence the imperial estates much better.

Military constitution

At first, the Reichstag found it difficult to provide the funds it needed for the war against the Ottomans. That this succeeded was only thanks to the personal intervention of the Emperor and Archbishop Schönborn. However, Leopold did not succeed in setting up a unified central imperial army against the resistance of the great imperial estates . He remained dependent on the contingents of the armed classes and the financial contribution of the small territories. After all, a Reich Generality and a Reich War Council were created as a supervisory body for the first time . When it was time to do so after the first peace with the Ottomans, it was not possible to build up a modern imperial army. Contemporaries such as Samuel von Pufendorf or Leibniz saw this as a threat to the empire as a whole. Against the background of growing French threat, a military order was finally passed in 1681/82, which was later called the Imperial War Constitution. This remained in force until the end of the empire. After that, the imperial districts had to provide an army of 40,000 men. In addition to a Reich War Fund, district war funds were also set up. But even this arrangement did not lead to a standing Reichsheer. Many questions, such as the appointment of the generals, remained unanswered. The Imperial Army was not involved in the Turkish Wars, which were not fought as Imperial Wars. This was a matter for the Habsburg- Imperial troops , the contingents of other territories and that of some imperial districts. In the west of the empire, various imperial circles ( Vordere Reichskreise ) began to combine in district associations to defend against France . The Kaiser joined the Laxenburg Alliance . For effective defense of the Reich, Leopold preferred these voluntary military services of an association to compulsory contributions from all imperial classes. He also used the idea of association to expand his power in the empire.

Foreign policy

In terms of foreign policy, Leopold's reign was shaped by the Habsburg-French conflict and the struggle against the Ottoman Empire . Although not very enthusiastic about war himself, he was forced to go to war in the west and east throughout his reign. There were often interactions between the theaters of war and between politics in the West and in the East. His main adversary, Louis XIV, used the ties between the imperial forces in the east for his expansion policy on the western borders of the empire.

Wars in Poland and against the Ottomans

The first war in which Leopold intervened was the fight in Poland (1655–1660) against Charles X of Sweden, who threatened the Hungarian border from there.

The first Turkish War (1662–1664) in Leopold's reign emerged from the disputes over the successor to the Prince of Transylvania Georg II. Rákóczi . The Ottoman offensive led by Ahmed Köprülü failed because of the victory of the imperial troops and the imperial troops under Count Montecúccoli , who had previously reorganized the army, in 1664 in the battle of Mogersdorf an der Raab . Leopold I ended the war in the Peace of Eisenburg . The peace, however, was unfavorable for the emperor, since it did not specifically affect the Turkish position of power. The background was that Leopold wanted to end the war as quickly as possible in order to address the threat in the west. The resentment in the Hungarian nobility was great and partly responsible for the great magnate conspiracy.

Wars in the west

During the Dutch War (1672–1679), Leopold had to defend not only the interests of Austria , but also those of the empire against the French King Louis XIV. Ultimately, however, Leopold proved to be inferior to the French troops. In 1679, the emperor and empire had to join the Peace of Nijmegen . This brought France the then Spanish Free County of Burgundy and Freiburg.

The French king exerted increased pressure on the empire between 1679 and 1683 with the so-called reunion chambers, which he set up. With the help of Prince-Bishop Wilhelm Egon von Fürstenberg , the French king succeeded in taking Strasbourg for himself. Leopold's alliance with the Netherlands and Sweden was unsuccessful. Ultimately, he had to recognize the French acquisitions.

Last Ottoman expansion attempt

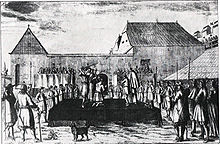

The internal crisis in Hungary brought about by the imperial policy itself and the emperor's conflicts with France led to the new Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pascha daring a new venture. This culminated in the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna . This lasted from July 13th to September 12th, 1683.

The emperor and his court had previously left Vienna. He stayed first in Passau and then in Linz. Leopold had gathered an imperial-German-Polish relief army, which under the Polish King Johann III. Sobieski and Duke Charles V of Lorraine liberated Vienna after the Battle of Kahlenberg . The merit of Leopold was to have the support of the Reich, the Poles and Pope Innocent XI. to win for this war, whereby the imperial troops were strengthened to almost four times.

Great Turkish War

The victory of 1683 put an end to the Ottomans' expansion in Central Europe. As a result, imperial policy in the East was offensive.

In the course of the Great Turkish War (1683–1699), the whole of Hungary was wrested from the Ottomans again. In 1686 Buda fell and in 1687 Mohács . In 1688 the troops under Elector Max Emanuel of Bavaria conquered Belgrade . In 1691, Margrave Ludwig Wilhelm I of Baden , also known as Türkenlouis, who had been in charge of the armed forces since 1689, triumphed at Szlankamen , which opened the way for the imperial army to the southeast.

As a result of the wars in the west, the pressure on the Ottomans eased somewhat. This changed with the appointment of Eugene of Savoy . He was victorious in 1697 at Zenta over the Ottoman army.

In the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), Leopold was also confirmed in possession of parts of Hungary that had previously been under Turkish rule. He also won Slavonia and Transylvania. This marked the beginning of Austria's real ascent to a great power.

War of the Palatinate Succession

Parallel to the Turkish war, a new source of conflict arose in the west with France when it made its alleged claim to the inheritance of the Electoral Palatinate. This led to the alliance of the emperor with various estates of the empire in 1685. The resulting Palatinate War (1688–1697) was fought as an imperial war. The French occupied the Rhineland and devastated the Rhine Palatinate. Leopold and the Viennese diplomacy succeeded in establishing a broad European alliance in 1689 and in securing the support of most of the imperial estates. However, this collaboration was not granted much success. More important were the military successes of the imperial general, Prince Eugene, in the Italian theater of war in 1695/96.

After the War of the Palatinate Succession, the Peace of Rijswijk in 1697 secured Austria's claim to the Spanish Netherlands . With the return of Freiburg, Luxembourg and Breisach, it meant a partial return to the status quo ante. The so-called Rijswijk clause should prove to be a problem for the Palatinate Protestants.

Spanish inheritance problem

It was foreseeable relatively early that the Spanish King Charles II would die without heirs. It was also foreseeable that the other European powers, and especially France, would not accept the unification of the Austrian and Spanish Habsburg lands. Leopold had negotiated this question with France as early as the 1660s. Both sides agreed in a secret treaty of 1668 to partition the Spanish possessions. The Spaniards themselves brought the Bavarian Elector Joseph Ferdinand of Bavaria into play as heir to the throne , but he died shortly afterwards. After that, Louis XIV. And the English King Wilhelm III. another division plan. The son of Leopold Karl should get Spain and the colonies, while Philip of Anjou should essentially get the Italian possessions. In the will of Charles II, who died in 1700, Philip of Anjou was expressly named as heir. However, Leopold was convinced that as head of the House of Habsburg he was entitled to the Spanish possessions. However, it was clear to him that the European powers would not support an undivided Habsburg Empire. Instead, he planned to create two new Habsburg lines. While Charles was to receive the Spanish possessions, Joseph was earmarked for the Austrian inheritance. In 1703 Charles was proclaimed King of Spain. In a treaty, the emperor and brother Joseph ceded all claims to the Spanish possessions, with the exception of Lombardy, to Charles. At the same time, a secret regulation on succession in the House of Habsburg was concluded (Pactum mutuae successionis). This confirmed the mutual succession of both lines.

War of the Spanish Succession

As early as 1701, Leopold had started the war for the Spanish inheritance on his own, with no further allies, through a campaign in Italy. There was also no formal declaration of war on France or Philip of Anjou, who is recognized as king in large parts of Spain. Leopold had secured the support of the considerable Kurbrandenburg army as early as 1700 when he was on the occasion of the imminent coronation of Frederick III. von Brandenburg promised to recognize him inside and outside the empire as king in Prussia .

In 1701 the Hague Great Alliance was formed from Austria or the Holy Roman Empire, the Netherlands, England and Prussia against France. The declaration of war followed in 1702. In the empire, the Wittelsbach Bavaria ( Bavarian Diversion in the War of the Spanish Succession ) and Kurköln and Braunschweig joined France. Reich executions took place against Kurköln and Braunschweig. In Hungary the situation was exacerbated by the uprising of Francis II Rákóczi. In 1704 the generals of the allies Eugene of Savoy and John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, defeated the French in the battle of Höchstädt . Bavaria was imperially occupied .

In the middle of the war, the Emperor died at the age of 65 in his royal seat, Vienna.

Construction activity, promotion of science and the arts

In order to make the courtyard as attractive as possible, Leopold created an ambitious building program. It made Vienna a baroque city. The new construction of Schönbrunn Palace goes back to Leopold, as did the Leopoldine wing of the Hofburg and the foundations for the baroque redesign of the city. In 1683 he had the Trinity Column erected in Vienna to commemorate a wave of plague he had survived. It contains a statue of himself praying in pompous armor and became a model for similar monuments in other places.

In 1703 he allowed the establishment of the Wienerische Diarium, the later Wiener Zeitung . In 1704, work began on the Linienwall , a fortification between the suburbs and the suburbs, where the street of the Vienna Belt extends today .

Leopold was gifted with languages. In addition to German and Latin, he also spoke Spanish and French. However, his favorite language was Italian. He was interested in literature, science and history. Advised by court librarian Peter Lambeck , he distinguished himself as a collector of books, antiques and coins. He significantly supported the founding of universities in Innsbruck , Olomouc and Breslau . He also supported Leibniz's plans to found an academy . This did not happen, but in 1692 the Academy of Fine Arts was founded. He was an honorary head of the Leopoldina natural research society named after him . He also founded the Collegium of History. Influenced by mercantilism , he brought important cameraists to his court. However, there was hardly any implementation of mercantilist ideas in practice. He was even fond of alchemy .

Leopold was a talented composer and music lover who played several instruments and conducted his chamber orchestra himself. He left behind over 230 compositions of various kinds, from smaller sacred compositions and oratorios to ballets and German Singspiele. Above all, he promoted Italian music, especially Italian opera. Nevertheless, he was the first non-Italian to appoint Johann Heinrich Schmelzer as imperial court conductor . Italian, often religious influences, also played an important role in literary terms.

Like the empress mother Eleonora Magdalena and other members of the imperial court, Leopold was an avid theater-goer and became a great patron of the theater arts. From January 1, 1659, Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini , who was appointed by Ferdinand III in 1651, was responsible for the organization of parties, the construction of theaters and the furnishing of comedies and operas . with the father Giovanni from Venice was called to Vienna, in his service. In 1659 Leopold had a wooden theater for comedies built on the so-called Rosstummelplatz, today's Josefsplatz , which was dismantled three years later, perhaps due to the opposition of the Jesuits against the comedies. Only a few years later, in 1668, Burnacini was commissioned to build the theater on the curtain wall in the immediate vicinity. The grand opera Il pomo d'oro by Antonio Cesti was premiered in this famous theater . This was followed by the performance of numerous operas and theater pieces until the wooden building, which was located next to the fortifications near the Hofburg, was demolished on the occasion of the second Ottoman siege in 1683 due to the acute risk of fire.

Personality and historical significance

His actions were deliberate and ultimately successful. Personal shyness was paired with an awareness of his imperial dignity. He was personally humble, pious, and utterly unmilitary. Anton Schindling judges that Leopold's reserved character was a stroke of luck for the House of Habsburg in view of the difficult starting position. He could wait patiently, was permeated with dynastic awareness and justice.

In contrast to Louis XIV , who went to great lengths to assert a certain image in public, in Leopold's case a well-meaning journalism and propaganda also helped. But the control effort of the court remained, unlike in France for Louis XIV, relatively low. The image cultivation carried out by many actors in the traditional imperial consciousness contributed to the fact that Leopold was associated with the resurgence of the imperial reputation among the public. He was referred to as Leopold the Great and, like Louis XIV, was seen as the Sun King. The small German historiography of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century painted a negative picture of Leopold. This accused the emperor of national disinterest and of backing away from the French expansionist efforts.

In fact, Leopold was long underestimated. Oswald Redlich described him as the architect who made Austria the “world power of the Baroque”. In terms of imperial politics, Anton Schindling called him “Emperor of the Peace of Westphalia” because he recognized the decisions made there and knew how to use them politically. His struggle against the reunion policy in the West shows that Leopold still took his office as emperor seriously, in contrast to his successors. However, the expansion in the southeast also meant that the Habsburg sphere of influence grew out of the empire. His favoring the Hohenzollern, Welfs and Wettins was a prerequisite for their increase in power and thus for the internal conflicts in the empire of the 18th century.

The empire that the contemporary Samuel von Pufendorf had seen after the end of the Thirty Years War before the dissolution, Leopold secured a century of stable development.

Death and burial

Leopold I died on May 5, 1705 in Vienna. His burial is a typical example of the burial ritual as it was practiced by high-ranking personalities in the Baroque period. After his death, Leopold I was laid out in public for three days: dressed in a black silk coat, gloves, hat, wig and sword, his body was on display, next to the catafalque there were candlesticks with burning candles. The insignia of secular power, such as crowns and medals, were also represented.

After the public display, the corpse was placed in a wooden coffin lined with precious fabrics, which was then transferred to the Vienna Capuchin Crypt after the public celebrations and lifted there in the elaborately designed metal sarcophagus during the emperor's lifetime.

The corpse had been preserved immediately before the public laying out: the rapidly decomposing internal organs had been removed, the cavities had been filled with wax and the surface of the corpse had also been treated with disinfecting tinctures. The body parts removed from the corpse were wrapped in silk scarves, placed in alcohol, and the containers were then soldered shut. The emperor's heart and tongue were placed in a gold-plated silver cup that was placed in the Habsburgs' heart tomb . His entrails, eyes and brain were buried in a gilded copper cauldron in the ducal crypt of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna.

Leopold I is one of those 41 people who received a “ separate burial ” with the body being divided between all three traditional Viennese burial sites of the Habsburgs (imperial crypt, heart crypt, ducal crypt).

Marriages and offspring

His first marriage in 1666 in Vienna was his niece and cousin Margarita Teresa of Spain (1651–1673), the daughter of Philip IV of Spain and his wife Maria Anna of Austria . The marriage had four children:

- Ferdinand Wenzel (1667–1668)

- Maria Antonia (1669–1692) ⚭ 1685 Maximilian II. Emanuel (1662–1726), Elector of Bavaria

- Johann Leopold (* / † 1670)

- Maria Anna Antonie (* / † 1672)

His second marriage was in Graz in 1673, his second cousin Claudia Felizitas of Austria-Tyrol (1653–1676). The marriage resulted in two children who died young:

- Anna Maria Sophie (* / † 1674)

- Maria Josefa Clementine (1675–1676)

In his third marriage in 1676 in Passau, he married his second cousin Eleonore Magdalene von Pfalz-Neuburg (1655–1720), daughter of Elector Philipp Wilhelm and his wife Elisabeth von Hessen-Darmstadt . The marriage had ten children:

- Joseph I (1678–1711) Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire ⚭ 1699 Wilhelmine Amalie von Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1673–1742)

- Christine (* / † 1679)

- Maria Elisabeth (1680–1741), governor of the Austrian Netherlands

- Leopold Josef (1682–1684)

- Maria Anna (1683–1754) ⚭ 1708 Johann V (1689–1750), King of Portugal

- Maria Theresa (1684–1696)

- Charles VI (1685–1740), Holy Roman Emperor ⚭ 1708 Elisabeth Christine von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (1691–1750)

- Maria Josepha (1687–1703)

- Maria Magdalena (1689–1743)

- Maria Margaretha (1690-1691)

ancestors

| Charles II (Inner Austria) (1540–1590) | |||||||||||||

| Ferdinand II (HRR) (1578-1637) | |||||||||||||

| Maria Anna of Bavaria (1551–1608) | |||||||||||||

| Ferdinand III. (HRR) | |||||||||||||

| Wilhelm V (Bavaria) (1548–1626) | |||||||||||||

| Maria Anna of Bavaria (1574-1616) | |||||||||||||

| Renata of Lorraine (1544–1602) | |||||||||||||

| Leopold I. (HRR) (1640–1705) | |||||||||||||

| Philip II (Spain) (1527–1598) | |||||||||||||

| Philip III (Spain) (1578-1621) | |||||||||||||

| Anna of Austria (1549-1580) | |||||||||||||

| Maria Anna of Spain (1606–1646) | |||||||||||||

| Charles II (Inner Austria) (1540–1590) | |||||||||||||

| Margaret of Austria (1584–1611) | |||||||||||||

| Maria Anna of Bavaria (1551–1608) | |||||||||||||

Honors

- Leopoldstein Castle in Styria, built in 1670, bears his name.

- The Leopold Column with a statue of Leopold, which commemorates the imperial visit to the city in 1660, has been located in Trieste on Piazza della Borsa (Börsenplatz) since 1808 .

- The 2nd district of Vienna has been called Leopoldstadt since 1850 .

- In 1993 the Austrian Mint minted a silver commemorative coin with a face value of 100 schillings from the series “1000 Years of Austria”.

- The University of Innsbruck was converted from a Jesuit grammar school into a full university with four faculties by Emperor Leopold in 1669 and equipped with a law faculty and a medical faculty in 1671/72. It therefore bears the name Leopold-Franzens-University today .

literature

- Adam Wolf : Leopold I (1640-1705) . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, pp. 316-322.

- John Philip Spielman: Leopold I. Not born to power (original title: Leopold the First of Austria , translated by Gerald and Uta Szyszkowitz). Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1981, ISBN 3-222-11339-4 .

- Volker Press : Leopold I, Kaiser. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , pp. 256-260 ( digitized version ).

- Anton Schindling : Leopold I. In: Anton Schindling, Walter Ziegler (Hrsg.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany . Beck, Munich 1990. ISBN 3-406-34395-3 , pp. 169-185.

- Thomas H. von der Dunk: 'Leopold', in: ders., The German Monument. A story in bronze and stone from the High Middle Ages to the Baroque . Böhlau, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-412-12898-8 , pp. 413-526.

- Karl Schwarz: Leopold I, Roman King, German Emperor. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 4, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-038-7 , Sp. 1501-1505.

- Rouven Pons: " Where the winning Loew has its Kayser-seat." Domination representation at the imperial Viennese currently Leopold I. German university publications, Egelsbach / Frankfurt a. M. / Munich / New York 2001, ISBN 3-8267-1195-5 .

- Jean Bérenger: Léopold Ier (1640-1705). Fondateur de la Puissance Autrichienne. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 2004.

Web links

- Literature by and about Leopold I in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Leopold I in the German Digital Library

- Curriculum vitae and list of works on Klassika.info

- Publications by and about Leopold I in VD 17 .

- Sheet music and audio files by Leopold I (HRR) in the International Music Score Library Project

- Entry on Leopold I (HRR) in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Sources on the court of Emperor Leopold I.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Anton Schindling: Leopold I. In: Anton Schindling, Walter Ziegler (Hrsg.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. Munich 1990, p. 169.

- ↑ a b Volker Press: Wars and crises. Germany 1600-1715. Munich 1991, p. 350.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Volker Press: Leopold I .. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , pp. 256-260 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ The coronation was carried out by Georg Lippay , Primate of Hungary and Archbishop of Gran .

- ↑ The coronation was carried out by Adalbert von Harrach , Archbishop of Prague.

- ↑ Johannes Burkhardt : Completion and reorganization of the early modern empire 1648–1763 . Stuttgart 2006, pp. 70f.

- ↑ a b Brigitte Vacha (Ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story . Vienna 1992, p. 262.

- ↑ a b c Anton Schindling: Leopold I. In: Ders./Walter Ziegler (Ed.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. Munich 1990, p. 182.

- ↑ Christof Dipper : German History 1648–1789 . Frankfurt 1991, p. 204 f.

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story . Vienna 1992, p. 260 f; Viennese history sheets. Volume 50, Association for the History of the City of Vienna, 1995, p. 191.

- ^ A b Leopold I., in: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaisertums Österreich , p. 428.

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story. Vienna 1992, p. 261

- ↑ a b c Anton Schindling: Leopold I. In: Ders./Walter Ziegler (Ed.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. Munich 1990, p. 179.

- ↑ Erwin Matsch: The Foreign Service of Austria (Hungary). 1720-1920 . Vienna and others 1986, ISBN 3-205-07269-3 , pp. 31-33.

- ↑ Johannes Burkhardt: Completion and reorganization of the early modern empire 1648–1763 . Stuttgart 2006, p. 72f.

- ↑ a b c d R. R. Heinrich: Leopold I. In: Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas Vol. 3, L - P. Munich 1979, p. 24.

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story . Vienna 1992, p. 253.

- ↑ cf. Petr Mat'a: Estates and Landtag in the Bohemian and Austrian countries. From the history of decline to interaction analysis. In: Ders., Thomas Winkelbauer (ed.): The Habsburg Monarchy 1620 to 1740. Achievements and limits of the absolutism paradigm. Stuttgart 2006 digitized version (PDF; 818 kB)

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story . Vienna 1992, p. 260 f.

- ↑ Tractatus de juribus incorporalibus (1679)

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story. Vienna 1992, p. 234 f.

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story. Vienna 1992, p. 236 f., P. 241

- ↑ Gerold Ambrosius : State and economic order: an introduction to theory and history . Stuttgart 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Robert John Weston Evans: Becoming the Habsburg Monarchy 1550-1700: Society, Culture, Institutions . Vienna 1989, p. 102.

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story . Vienna 1992, p. 240 f.

- ^ Jörg K Hoensch: History of Bohemia. From the Slavic conquest to the present. Munich 1997, p. 252.

- ^ RR Heinrich: Leopold I. In: Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas Vol. 3, L - P. Munich 1979, p. 23 f.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, p. 110.

- ↑ a b c Anton Schindling: Leopold I. In: Ders./Walter Ziegler (Ed.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. Munich 1990, p. 170.

- ↑ Klaus Herbers , Helmut Neuhaus : The Holy Roman Empire. Scenes from a thousand-year history . Cologne 2005, p. 250.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, p. 110 f.

- ^ A b Anton Schindling: Leopold I. In: Anton Schindling, Walter Ziegler (Hrsg.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. Munich 1990, p. 171.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, p. 111.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, p. 112.

- ↑ Austria and the Holy Roman Empire. Exhibition by the Austrian State Archives. Vienna 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, p. 116.

- ↑ Austria and the Holy Roman Empire. Exhibition by the Austrian State Archives. Vienna 2006, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Adam Wolf: Leopold I (German Emperor) . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, p. 316.

- ^ Anton Schindling: Leopold I. In: Ders./Walter Ziegler (Hrsg.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. Munich 1990, p. 175.

- ↑ Klaus Herbers, Helmut Neuhaus: The Holy Roman Empire. Scenes from a thousand-year history . Cologne 2005, p. 249.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Anton Schindling: Leopold I. In: Ders./Walter Ziegler (ed.): Die Kaiser der Neuzeit. Munich 1990, p. 172.

- ↑ Klaus Herbers, Helmut Neuhaus: The Holy Roman Empire. Scenes from a thousand-year history. Cologne 2005, p. 250 f.

- ↑ Klaus Herbers, Helmut Neuhaus: The Holy Roman Empire. Scenes from a thousand-year history. Cologne 2005, p. 255

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495-1806 . 4th edition Darmstadt 2009, p. 113f.

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story. Vienna 1992, p. 245

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story. Vienna 1992, pp. 246-248

- ↑ Brigitte Vacha (ed.): The Habsburgs. A European family story. Vienna 1992, p. 248 f.

- ↑ Andrea Sommer-Mathis - Daniela Franke - Rudi Risatti (ed.): Spettacolo barocco! Triumph of the theater . Imhof, Vienna (exhibition catalog Theatermuseum) 2016.

- ↑ Risatti, Rudi .: Grotesque Comedy in the Drawings of Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636-1707). Hollitzer Wissenschaftsverlag, 2019, ISBN 978-3-99012-766-7 ( worldcat.org [accessed February 21, 2021]).

- ↑ see Jutta Schuhmann: The other sun. Kaiser image and media strategies in the age of Leopold I Berlin 2003

- ↑ Johannes Burkhardt: Completion and reorganization of the early modern empire 1648–1763. Stuttgart 2006, p. 72f.

- ↑ Axel Gotthard: The Old Empire 1495–1806 . Darmstadt 2009, p. 118

- ↑ Cf. Alexander Glück / Marcello LaSperanza / Peter Ryborz: Unter Wien: In the footsteps of the third man through canals, tombs and casemates. Christoph Links Verlag 2001, p. 44 ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ↑ Österreichischer Lloyd (Ed.): Triest. Travel guide for visitors to this city and its surroundings . Trieste 1857, p. 58

- ↑ Hannes Obermair : Early knowledge. Looking for pre-modern forms of knowledge in Bolzano and Tyrol . In: Hans Karl Peterlini (Ed.): Universitas Est. Volume I: Essays on the history of education in Tyrol / South Tyrol from the Middle Ages to the Free University of Bozen . Bozen: Bozen / Bolzano University Press 2008. ISBN 978-88-7283-316-2 , pp. 35-87, reference pp. 80-83.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Ferdinand III. |

Roman-German Emperor 1658–1705 |

Joseph I. |

| Ferdinand III. |

Archduke of Austria 1657–1705 |

Joseph I. |

| Ferdinand III. |

King of Hungary 1655–1705 |

Joseph I. |

| Ferdinand III. |

King of Bohemia 1656–1705 |

Joseph I. |

| Ferdinand III. |

King of Croatia and Slavonia 1657–1705 |

Joseph I. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Leopold I. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia and Hungary |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 9, 1640 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 5, 1705 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Vienna |