Magnate conspiracy

The magnate conspiracy or conspiracy of Muray or Wesselényi conspiracy ( Wesselényi conspiracy, Wesselényis conspiracy ; Hungarian Wesselényi-összeesküvés ; Slovak : Vešeléniho / Wesselényiho sprisahanie ) or Wesselényi-Zrinyi in Croatia ( koprinski-zrinskiy conspiracy) ( Zrinsko- Croatian ) -frankopanska ), was a conspiracy of important noble families in royal Hungary and Croatia from 1664/1666 to 1670/1671against their ruler, Emperor Leopold I of Habsburg. The uprising was exposed and the revolt quickly put down. Many of those involved were executed, others fled and triggered the Kuruc uprisings that followed .

Starting position

From the point of view of the conspirators, the trigger was the emperor's misconduct after winning the battle of Mogersdorf against the Ottomans and the agreed conditions in the Peace of Eisenburg / Vasvár in 1664 , which was viewed as a disgraceful peace of Eisenburg . Emperor Leopold I , who was inexperienced at the time, had to cede large areas of Royal Hungary and Croatia to the Turks despite a victory of his troops during the Turkish War of 1663/1664 , which angered many nobles against the Habsburgs. The recapture of areas that were once lost to the Turks was expected to bring additional influence and wealth.

During this period, the Hungarian magnates were deprived of traditional rights as a result of the emperor's absolutism and centralism , which led to disappointment and dissatisfaction. The Reformation had also gained a foothold among most of the Hungarian aristocrats and thus their serfs, and they wanted to distance themselves from the Catholic Cisleithania , as a partially violent re-Catholicization was carried out from there . There was also dissatisfaction with the practice of giving the lands reclaimed from Turkish hands to the Hungarian nobles only if they could provide evidence of family ownership. After about 150 years this was not always possible and so many goods went to deserving soldiers and civil servants. At that time it was also unusual to billet soldiers in barracks, in most cases the army requisitioned their accommodation near the place of action and there were frequent looting and violence.

From the court's point of view, restricting the local nobility was the only means of surviving the constant threat posed by the Ottoman Empire. One was tired of seeing the monarchy's fighting power endangered by the internal quarrels in the Kingdom of Hungary. In addition, the finances were in a very poor condition, the Ottoman army was still far superior to the imperial one and, to make matters worse, a war with France threatened . It was of the opinion that newly conquered areas could not be held anyway. That is why the first goal of the peace negotiations was to achieve a ceasefire as a much-needed respite.

Conspiracy and betrayal

The conspiracy of 1664 was led by Franz Wesselényi , the palatine of the Kingdom of Hungary, Nikola Zrinski ( ung. Zrínyi Miklós), the Ban of Croatia, (after his death by his brother Petar Zrinski ) and Fran Krsto Frankopan . They received support from other members of the nobility such as Franz III. Nádasdy , Franz I. Rákóczi (husband of Helena Zrinski ( Croatian Jelena Zrinski ), the daughter of Petar Zrinski), Stephan Thököly , György Lippay and Hans Erasmus von Tattenbach , a Styrian nobleman. The meetings took place in the baths of Trenčín-Teplitz and Altsohl in what is now central Slovakia .

The noble families of the Zrinski and the Frankopan were linked by family ties and formed the two most influential and powerful aristocratic families in Croatia. Numerous castles, palaces and lands in Croatia were in their possession. With the death of Nikola Zrinski in 1664, the Habsburgs began to disempower both sexes. Nikolas brother Petar Zrinski was appointed Croatian Ban . When the Generalschaft Karlovac (Karlstadt) instead of Petar Zrinski was slammed into his bitterest opponent, Count Johann Joseph von Herberstein , he saw the rebellion against the emperor as the last resort to safeguard his interests.

The conspirators initially conducted negotiations with France , Poland-Lithuania , the Republic of Venice and also the Ottoman Empire in order to examine possibilities of resistance against Vienna. This constituted high treason in the Kingdom of Hungary, especially since the region was of particular strategic interest as a permanent war zone with the Ottoman Empire. The emperor therefore had spies in the border region who were able to uncover the conspiracy in 1669. The Archbishop of Gran Georg Szelepcsényi , a confidante of the emperor, played a decisive role in uncovering the conspiracy . László Fekete - Iványi (ung. Iványi-Fekete László) betrayed the conspirators to the archbishop, who passed this information on to the Viennese imperial court. The Ottomans also probably reported the negotiations with the conspirators to the imperial court. The longed-for arms aid was only provided to the Croatian conspirators through Venice, albeit to a very limited extent.

At first the insurgents tried to recruit further allies into their ranks, doing all sorts of propaganda and anti-Habsburg agitation. In contrast, the forces loyal to the emperor tried to discredit the conspirators through rumors in the eyes of the population. They ventured that Ana Katarina Frankopan-Zrinski - Petar's wife - had converted to Islam and that Zrinski wanted to separate his people from Catholic Austria at great cost. Legend later emerged that the deaths of Nikola Zrinski (hunting accident), Lippay and Wesselényi (illness or poisoning) were murders by Habsburg agents. But since they died before 1669, this is highly unlikely.

Then, after six years of preparation, with practically no support from foreign powers, the armed rebellion was dared. This was put down immediately, however, and everyone was well informed and prepared about all the steps taken by the conspirators. Some had already betrayed everything to the Viennese court. General Herberstein moved into Croatia with his troops and arrested the rebels. Thököly died while trying to entrench himself in his northern Slovak fortress Arwaburg and Franz I. Rákóczi was taken prisoner near Munkacs . His mother Sophia Báthory , who had excellent contacts with the Jesuits , was able to save his life by paying a ransom of 400,000 guilders to the imperial war chest.

Paul I, Prince Esterházy , who was loyal to the emperor , was later accused of having passed this information on and of having been rewarded with lands belonging to the conspirators.

Detention and Trial

Finally, the remaining conspirators Nádasdy, Tattenbach, Frankopan and Zrinski were summoned to the court of Leopold I. The Croatian nobles believed the mediation by Martin Borković , the bishop of Zagreb, and the letter from the king assuring them safe conduct. In Vienna, both were initially placed under house arrest. Some time later they were all taken to a dungeon in Wiener Neustadt , where they were subjected to torture. Accusations from each other were brought to the prisoners, and the traitors to the conspiracy had gathered sufficient material.

For the remaining leaders of the conspiracy (Nádasdy, Petar Zrinski and Frankopan) a special court was set up under the chairmanship of Chancellor Johann Paul Hocher . They were sentenced to death on April 23 and April 25, 1671 for high treason . The grounds for the verdict against Petar Zrinski stated that he

“Committed the greatest sins of trying to be crowned an independent Croatian ruler. Instead of a crown, a bloody sword awaits him. "

Zrinski wrote to his wife Ana Katarina Frankopan-Zrinski:

“Today we forgave one another of our sins. For this reason I am also writing to you to ask your forgiveness. If I've treated you wrong sometimes, forgive me. In the name of our father, I am ready to die and I am not afraid. "

Frankopan also wrote a very emotional letter to his wife:

“My dear Julia, I would have to lie with all my soul in order to hide the last expression of my deep love for you. But I am naked and miserable. "

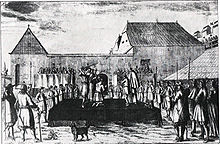

On April 30, 1671, Zrinski and Frankopan were taken to their place of execution at the civic armory in Wiener Neustadt . Before his death, Zrinski tied his hair with a handkerchief so that the hangman's ax could hit his neck directly without being slowed down by the hair. Even so, the drunken hangman did not cut off his head until he had his second blow with the sword. It was the same with Frankopan. Nádasdy was executed on the same day in the old town hall in Vienna and Tattenbach on December 1, 1671 in Graz.

The remains of the two Croatians were reburied in the cathedral of Zagreb after the end of the Danube monarchy in 1919 . The tombstones can still be seen at the cathedral in Wiener Neustadt and at the municipal cemetery.

consequences

The aristocratic families involved were de facto expropriated. Two younger daughters of Petar Zrinski died in the monastery, Helena fought against the Habsburgs until 1688. His son Ivan Antun went mad after torture and incarceration and died in 1703 at the age of about 50. The same happened to his wife Ana Katarina Frankopan-Zrinski in 1673 . Nikolaus' son Adam died in the Battle of Slankamen in 1691 . Frankopan's only son died at a young age. Both families remained without male successors and the Croatian territories lost the leading noble families, after which only a few Croatians rose to become Ban.

In 1671 the emperor had an investigative committee set up in Levoča and then a special court in Pressburg (the Judicium delegatum extraordinarium Posoniense , the so-called Rottal Court), which summoned more than 200 suspicious nobles. There were prison terms, enslavement and execution. As a result, Protestants were persecuted and driven out and their churches burned down. The offices of Palatine and Ban were abolished, new taxes introduced and royal Hungary and Croatia occupied by the military. After international protests, the worst measures were withdrawn after a year and the galley slaves were released. The Hungarian constitution was not restored and normality was restored until the Landtag of Ödenburg in 1681 . Many noble families from what is now Croatia, Slovakia and Hungary fled to Transylvania and submitted to Ottoman rule. Together with the descendants of the executed nobles, the refugees triggered the Kuruc uprisings , which led the Ottomans to the Great Turkish War and the second Turkish siege of Vienna, and which shook the Kingdom of Hungary until 1711.

In the 19th and 20th centuries the conspirators were revered by nationalists in Hungary and Croatia as early freedom fighters and stylized as national heroes . This has very little in common with reality in the 17th century, since the nobility hardly cared about nationalities in the domain. It was about power, wealth and influence, a division of rule according to peoples was contrary to one's own endeavors. Demands for the self-determination of the peoples came into being more than 100 years later, after the French Revolution .

swell

- Franz Theuer : Tragedy of the Magnates: The Conspiracy from Muray to the Ödenburg Reichstag: A historical report . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna et al. 1979, ISBN 3-205-07150-6 .

- Emil Lilek : Critical representation of the Hungarian-Croatian conspiracy and rebellion 1663–1671 . 4 vols. Self-published, Cilli 1930.

- Entry on magnate conspiracy in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- History of the Magyars, Volume 5

- Prehistory in the standard

- Diploma thesis: Prince Eugene of Savoy and Count Imre Thököly

Individual evidence

- ^ László Fekete-Iványi belonged to the Hungarian nobility. Between 1650 and 1661 he was deputy commandant of the fortress Fileck and a follower of the palatine Franz Wesselényi , who in 1668 initiated him into the planned conspiracy. Out of greed and in the hope of increasing his possessions through betrayal, he betrayed the conspirators to the archbishop. (quoted from Magyar életrajzi Lexikon, Vol. 1, p. 786)

- ^ Nepomuki Johann Mailath: History of the Magyars. F. Tendler, 1831, accessed August 31, 2016 .

- ^ Gábor Bartha: Prince Eugene of Savoy and Count Imre Thököly . Ed .: University of Vienna. Vienna December 2012.