Friedrich I (Prussia)

Friedrich I (born July 11, 1657 in Königsberg , † February 25, 1713 in Berlin ) from the House of Hohenzollern was named Friedrich III. Elector of Brandenburg and Duke in Prussia and crowned himself in 1701 as Friedrich I as the first king in Prussia .

After taking power on May 9, 1688, Friedrich, who was popularly called Schiefer Fritz due to his crooked spine , continued his father Friedrich Wilhelm's domestic and foreign policy . In the same year he supported Wilhelm III. of Orange on landing in England . In the Palatinate War of Succession he took part in the siege of Bonn in 1689, but rarely commanded his troops. As an admirer of Louis XIV of France , Frederick sought to become a kingdom. The approval of Emperor Leopold I.but only reached when he needed his troops in the threatening war against France. On January 18, 1701 Frederick crowned in Konigsberg Castle to King of Prussia . In the War of the Spanish Succession he supported Emperor Leopold I as agreed with the Prussian Army , which distinguished itself in the Second Battle of Höchstädt in 1704.

Under Frederick's rule, the country experienced on the one hand a financial decline due to the lavish court and the corrupt cabinet of three counts , but on the other hand also a cultural rise through the admission of persecuted Huguenots , the founding of the later Prussian Academy of Sciences and the expansion of Berlin into a baroque royal seat . By becoming a kingdom, Friedrich laid the foundation for the development of Prussia into a major European power.

Life

Childhood and Adolescence (1657–1674)

|

Joachim Friedrich (Elector of Brandenburg) ⚭ Catherine of Brandenburg-Küstrin |

Albrecht Friedrich (Duke in Prussia) ⚭ Marie Eleonore |

Louis VI. (Elector of the Palatinate) ⚭ Elisabeth |

William I (Orange) (main leader of the Dutch revolt) ⚭ Charlotte de Bourbon-Montpensier |

Wilhelm (Count of Nassau-Dillenburg) ⚭ Juliana |

Gaspard II. ⚭ Charlotte de Laval |

Conrad (Count of Solms-Braunfels) ⚭ Elisabeth von Nassau-Dillenburg |

Ludwig I. (Count of Sayn and Wittgenstein) ⚭ Elisabeth of Solms-Laubach |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Johann Sigismund (Elector of Brandenburg) |

Anna (Electress of Brandenburg) |

Friedrich IV. (Elector Palatinate) |

Luise Juliana (Electress of the Palatinate) |

William I (Orange) (main leader of the Dutch revolt) |

Louise de Coligny | Johann Albrecht I of Solms-Braunfels | Agnes zu Sayn-Wittgenstein | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Georg Wilhelm (Elector of Brandenburg, Duke in Prussia) |

Elisabeth Charlotte |

Friedrich Heinrich (Governor of the United Netherlands) |

Amalie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Friedrich Wilhelm (Elector of Brandenburg and Duke in Prussia) |

Luise | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Karl Emil (Prince Elector of Brandenburg) |

Friedrich I. (King in Prussia) |

Ludwig (Prince of Brandenburg) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Friedrich was the third son of Elector Friedrich Wilhelm and Luise Henriette of Orange . On July 29th he was baptized in the Königsberg Castle Church. Since he was weak as an infant, his chances of survival were very slim in those days with high infant mortality rates . On top of that, he was so unhappily dropped by his midwife in the first year of his life that he kept a crippled shoulder for the rest of his life. That is why the Berlin vernacular called him the "Leaning Fritz". Friedrich survived this critical time for him and developed into a normal, slightly disabled man. In 1662 his education was given to Otto von Schwerin . At his mother's request, Friedrich lived with him on his property, the Minor town Altlandsberg , in order to strengthen his health in the country. His tutor taught the prince religion, history and geography at an early age, and he also learned French, Polish and Latin. At the age of 10 he had to recite an oration in Latin for his father's birthday . Even in Altlandsberg, Friedrich had such a great passion for splendor and pomp that he founded his own order “de la générosité” at the age of 10.

Otto von Schwerin remained Friedrich's tutor until June 20, 1676. His teacher was Eberhard von Danckelman . On March 23, 1664, his father decided that he should receive the Principality of Halberstadt as an inheritance, since his older brother Karl Emil, preferred by the Elector, stood before him in the line of succession. This was the second son of Luise Henriette, the first son Wilhelm Heinrich died at the age of 1 1 ⁄ 2 years. Karl Emil was strong and well-built, spirited and loved the military and hunting. In character he resembled the Great Elector, who therefore particularly liked him. The third son Friedrich is different; Since he was crippled by the wet nurse's accident in his first year of life, unconditional love came only from his mother. When Friedrich was ten years old, his mother Luise Henriette died; a year later the Great Elector married the 32-year-old widow Dorothea Sophie von Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg . While Luise Henriette was a very beautiful, sensitive and witty woman, Dorothea had a rather simpler temperament and also no advantageous appearance; she bore the Great Elector four more sons and three daughters. The relationship between stepmother Dorothea and Friedrich was not good.

In 1670 Friedrich was appointed Rittmeister of a "company on horseback", but did not lead this unit, which was due to his physical handicap. He did not receive any further promotions. At the age of 16 he asked King Charles II of England for the Order of the Garter , for which he had envied his father for a long time, and in 1673 he became engaged to the then twelve-year-old Elisabeth Henriette von Hessen-Kassel . It was not an engagement for dynastic purposes, but out of affection, which was rather unusual in royal houses at the time. The relationship between his future wives and Friedrich was less affectionate.

Elector Prince (1674–1688)

When his brother Karl Emil died on December 7th, 1674 after a short illness, Friedrich became elector prince . Because his importance as the direct successor to the throne had increased significantly, he accompanied his father in the Northern War during the campaigns in Pomerania from 1675 to 1678 and in early 1679 on the arduous winter campaign to Prussia against the invaded Swedes. After surviving a serious illness that he contracted on this campaign, he married the Hessian Princess Elisabeth Henriette on August 13, 1679 in Potsdam, to whom he had been quietly engaged since 1673. In 1680 the couple moved into the unfinished Köpenick Castle , which their father had commissioned , where the Prince Elector lived with them. On July 7, 1683, Elisabeth Henriette died of smallpox while pregnant in Berlin-Cölln . At her request, Friedrich was no longer allowed to visit his dying wife because of the risk of infection.

After the year of mourning had ended, Friedrich married the fifteen-year-old Welf Princess Sophie Charlotte of Braunschweig-Hanover in Hanover in 1684 . In this marriage, Friedrich Wilhelm , heir to the throne, was born in Berlin on August 14, 1688 . Friedrich also lived in Köpenick with his second wife, Sophie Charlotte, in order to escape the intrigues of the Berlin court. There was an atmosphere of constant suspicion and distrust and aversion caused by the ambitions of his stepmother Dorothea Sophie to secure parts of the electorate in the line of succession for her own sons. Friedrich saw in this a great danger for his inheritance claim to the undivided Brandenburg-Prussia.

The relationship with his father deteriorated considerably in the last years of his life due to the dispute over the question of inheritance. The strained father-son relationship broke out when the electoral prince became aware of the elector's testamentary provisions for the sons from the second marriage. After that, the Brandenburg homeland should have been divided among all sons (including the four sons from the second marriage). In 1682, Friedrich had the largest room in his Köpenick residence equipped with a complete series of coats of arms from the different parts of the country (“coat of arms hall”), thereby making clear his claim to be the sole heir.

In 1686 the Austrian envoy Baron Fridag von Goedens took advantage of the prince's uncertainty with regard to the succession to the throne. He concluded a treaty with Friedrich behind the elector's back, which provided for the return of the Schwiebus district to Austria. This small area of Silesia had been ceded to the elector for his help against France. At the same time, Friedrich renounced the already unpromising claims to the Silesian duchies of Brieg, Liegnitz and Wohlau. After the death of his father, Friedrich declared the contract null and void. The claims to parts of Silesia persisted according to Hohenzoller's view and gave his grandson Frederick the Great the official occasion to occupy Silesia at the beginning of the War of the Austrian Succession .

On April 7, 1687, at a time that was tense due to the planned wills in favor of Friedrich's half-brothers, Friedrich's younger brother Ludwig from his father's first marriage also died . Friedrich, who suspected his stepmother of poisoning, then decided not to return to Berlin from a spa stay in Karlsbad , but to travel to Kassel via Leipzig and Hanover . Friedrich only wanted to agree to the return to Berlin demanded by the aging elector with a guarantee of personal security, which further enraged his father. With Danckelmann's mediation, he was finally persuaded to return at the beginning of November 1687, after an absence of six months. A long discussion between son and father took place in Berlin, and Friedrich was allowed to attend the meetings of the Privy Council for the first time . Although their mutual distrust persisted, both felt that any further argument about the health of the elector had become pointless.

Elector (1688–1701)

Elector Friedrich Wilhelm died on May 9, 1688. A week later, the Secret Council met for the first time under the chairmanship of Frederick III. The subject and agenda was the opening and reading of the father's will. In violation of the house laws of the Hohenzollern , which had been in force since 1473 , Brandenburg-Prussia was to be divided between the five sons of Friedrich Wilhelm (Friedrich himself and his four half-brothers). After lengthy negotiations and detailed legal opinions (including by Eberhard von Danckelman), the heir to the throne succeeded in asserting himself against his siblings by 1692 and preserving the unity of the country. While his father had decided all government questions himself, Frederick III left. on May 20, 1688, as one of the first acts of government, the affairs of government to his former teacher von Danckelman.

Elector Friedrich III supported foreign policy. in November 1688 William of Orange on the landing in England and from 1688 to 1697 in the Palatinate War of Succession with Brandenburg troops the great alliance against France. Although the elector had inherited a coalition with France on paper from his father when he took office, for financial, family, denominational and strategic reasons, he quickly oriented himself to the anti-French, Protestant coalition organized by William of Orange . After five months of double play with Dutch and French agents, the elector openly positioned himself against France for the first time in October 1688. He was instrumental in the formation of the anti-French Magdeburg Concert . During the sieges of Kaiserswerth and Bonn in 1689, he showed in the forefront that he had physical courage.

From 1696 onwards, Elector Friedrich pursued the idea of raising the rank to kingship . He also directed his political ambition towards the unification of his torn state. In a sense, he was looking for a nationwide bracket. In addition, a higher rank in the hierarchically structured aristocratic society of that time was associated with a higher position and a higher reputation. Together with his second wife Sophie Charlotte von Hanover (1668–1705), a highly intelligent and emancipated princess from Hanover, he strove to achieve this goal. Initial explorations at the Viennese court met with strict rejection. At the end of 1696, Friedrich signed a secret contract with the Bavarian Elector Max Emanuel , in which both sides assured each other of support in obtaining the royal crown. However, this contract had no consequences. From 1697 Friedrich III. the thing with more energy. The upper president Danckelman and other senior state officials still resisted, given the high costs to be expected.

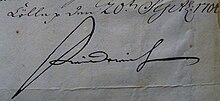

On December 20, 1697, through the intrigues of his enemies, Field Marshal Fuchs, Barfus and Dohna , Danckelman was arrested on Friedrich's orders and taken to the Spandau Citadel , where he was held in custody until 1707. The only reason for Danckelman's imprisonment was Friedrich's inability to assert his own way against the strong personality of his mentor. An opponent Danckelmans, John Casimir Kolbe von Wartenberg , who faced the intentions of the Elector less critical, entered with an annual salary of 120,000 Reichstalern to his successor. He brought his wife to him as maitresse, Catharina von Wartenberg . After the overthrow of Danckelman, Friedrich made serious plans to become his own prime minister and worked more closely with the Privy Council. Overtaxed by the resulting burdens, he agreed to a proposal by Wartenberg to have a selection made in advance by a narrow council consisting of four people .

The segregation procedure deprived the Privy Council of its competence in crucial matters. Wartenberg himself changed the composition of the inner council and from then on determined politics in Prussia, bypassing King Friedrich until 1710. In addition to Wartenberg, his partisans August David zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein and Alexander Hermann von Wartensleben (from 1702) formed the Cabinet of Three Counts . Friedrich did not see through these machinations. Due to their exploitative and corrupt policies, the cabinet became part of the three woes of the country, which was so called because of the first letters of their names.

After the death of Charles II , the last Habsburg king of Spain, on November 1, 1700, new conflicts arose in Europe. Due to the related disputes about the succession to the throne, the conditions for Frederick's concerns improved, because the Habsburgs needed allies in the war against France. After secret negotiations in Schönhausen Palace , on November 16, 1700, the emperor promised in the so-called contract that the Protestant elector could achieve the dignity of the king. The coronation should take place outside of the Holy Roman Empire . Also, the title of king was not allowed to refer to the Mark Brandenburg , which belonged to the empire , but only to Prussia, which was located on the other side of the empire, and could be "King in Prussia" (not " of Prussia"). In addition, Frederick III had to pay a high price of 2 million ducats to Emperor Leopold I and 600,000 ducats to the German clergy in order to gain royal dignity ; the Jesuit order received 20,000 thalers for the intercession of Father Wolf at the Viennese court. In addition, Friedrich committed himself to take part with 8,000 soldiers in the War of the Spanish Succession led by the Habsburg Emperor .

King (1701–1713)

On December 17, 1700, after the permission of Emperor Leopold, a long carriage train with an extensive retinue and 30,000 horses in front set off from Berlin to Königsberg, the Prussian capital. On the day before the coronation, the (still elector) founded the High Order of the Black Eagle . The coronation celebrations took place on January 18, 1701. In order to document his sovereignty to the world, Friedrich put the crown on himself in the castle church of Königsberg Castle , then crowned his wife Sophie Charlotte and had himself anointed by two Protestant bishops, one for the Reformed Hohenzollern and one for the majority Lutheran people . The Pope never accepted Frederick's royal dignity, because Prussia had been Lutheran since 1525, and Frederick's father, the Great Elector , had represented the Protestant side against the papacy in the Peace of Westphalia . The secret crown treaty between Kaiser and Frederick quickly became public and was partly used for amusement by the other imperial princes. The Elector of Brandenburg had contractually assured that in future imperial elections he would always give his electoral vote to the House of Habsburg , which seemed absurd in view of the Habsburg dominance in the empire. (See also: King Frederick III of Brandenburg's coronation )

As a result of the coronation as king in Prussia, the previously electoral Brandenburg institutions became royal Prussian institutions; In the next few decades, the term Prussia for the emerging state prevailed. Friedrich increased the political importance of his country and consolidated its development into what would later become a unitary state , which under his successors rose to become a major European power.

As the next male descendant of Wilhelm I of Orange , Friedrich inherited after the death of the childless Wilhelm III. of England in 1702 the counties of Lingen and Moers . In 1707, both areas were annexed to the county of Tecklenburg, which was acquired through purchase . Since Friedrich was a Calvinist , he could also be elected Prince of Neuchâtel in 1707 , which was internationally recognized by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. That is why Friedrich and his heirs also carried the title of "sovereign Prince of Orange, Neuchâtel and Valangin" . When his second wife Sophie Charlotte died of a neglected sore throat at her mother's in Hanover on February 1, 1705 while attending Carnival at the age of only 36, Friedrich fainted when the news arrived and had to be drained. Although the relationship with his second wife was quite cold, he was deeply struck by the knowledge of what excellent wife he had now lost. Her funeral cost 200,000 thalers and was so magnificent that 80,000 strangers came to Berlin to attend the funeral. The mourning lasted a year.

On November 27, 1708, Friedrich married the 23-year-old Sophie Luise von Mecklenburg . The purpose of the marriage was to have another son in order to ensure the continued existence of the dynasty in the event of the death of the only heir to the throne. In Berlin, Sophie Luise came into contact with August Hermann Francke and surrendered completely to his religious views. As a result, there were religious disputes between the spouses. After Francke returned to Halle on the orders of the king in 1710, the queen lived lonely and withdrawn, fell into melancholy and occasionally had attacks of absent-mindedness.

From July 2 to 17, 1709, Friedrich was able to present himself as the equal host of two monarchs at the meeting of the Three Kings in Potsdam and Berlin. His guests were August “the Strong” of Poland and Saxony and Frederick IV of Denmark . The extensive festivities, politically poor, put a further strain on the state finances, which were already heavily strained. However, in terms of foreign policy, Friedrich was able to prevent two wars that had been waged simultaneously and across Europe since 1701, the Great Northern War and the War of Spanish Succession, from encroaching on Prussian territory through his consistent westward orientation .

"If Friedrich I deserves praise, it is because he has always kept his country peaceful while the neighbors were devastated by war."

At the end of 1710, a commission of inquiry, ordered by the 22-year-old Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm , uncovered the bad economy of the three counts cabinet. The occasion was the affair surrounding the looted fire fund for homeowners in the town of Crossen , which, when the town burned down almost completely, could not be paid out. The three counts were finally dropped by the king and deposed at the end of December 1710. After receiving the investigation report on December 23, 1710, Friedrich was completely surprised by the extent of the corruption.

"I have never ordered such a thing ... muhs balt and the more the better it is to be changed"

On January 6, 1711, Wartenberg came again from Woltersdorf to Berlin for an hour-long talk with Friedrich. The king gave Wartenberg a valuable diamond ring and shed tears when he parted, although he knew full well that he had been lied to by him for years. The fact that he still gave him presents in tears testifies to the loneliness of Friedrich, for whom the amiable appearance had become more important than the reality. After the whole corruption affair of the Three Counts Cabinet had been exposed, Friedrich tried to repair the damage. The most important reorganization was the rescript of October 27, 1710, which made the validity of the administrative acts to be signed by the king no longer dependent on a dignitary, as was previously the case, but on the examination of the professionally competent privy councilor. This day was the foundation of the specialist authorities in Prussia. As a result of these changes, the financial situation slowly improved again.

death

Friedrich had been feeling weak and sick for a long time. Since his youth he suffered from narrow-chestedness , now came a strong cough and a frightening asthma. When his insane wife escaped from her lady-in-waiting one day, ran through the gallery, stepped into the king's chamber, fell through a glass door and threw himself over Friedrich, he suddenly woke up in his armchair and was startled at the sight of the white, bloody figure . The servants entered the room and tried to free the king from his wife's arms. She was taken back to her bedroom and brought back to her mother in Mecklenburg a few days later. The king fell into a fever and did not leave the bed until his death.

See also: Kings in Prussia and Kings of Prussia

politics

Cultural policy

Friedrich's internal politics concentrated on enhancing built culture and education with the aim of achieving equality with the other great European powers. In 1694 he founded the University of Halle , in 1696 the Mahl-, Bild- und Baukunst-Academie in Berlin, from which the Prussian Academy of the Arts emerged , in 1700 the Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences (later the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences ) and built the Comprehensive Royal Library in Berlin . During his reign, important scientists and artists came and worked in Prussia. Immediately after his coronation, he commissioned his court sculptor and architect Andreas Schlueter to design the famous Amber Room , which his successor Friedrich Wilhelm I gave to the Russian Tsar Peter the Great in 1716 .

Berlin, which until then had been medieval and provincial, was expanded into a splendid baroque residential city during his reign. City palaces and respectable town houses determined the palace and government area of Berlin. Andreas Schlüter set standards with the reconstruction of the Berlin Palace and, as a sculptor, created a magnificent representation of the ruler with the equestrian statue of the Great Elector on the Long Bridge, built in 1692, from 1695 to 1697. During his reign, the armory , Monbijou Palace (1703), Charlottenburg Palace from 1695, the Parochial Church , the Friedrichshospital from 1695 and the two cathedrals on the Gendarmenmarkt from 1701 were built . On the occasion of the bicentenary of the first Brandenburg State University Alma Mater Viadrina in 1706 in Frankfurt (Oder) , Erdmann Wircker first coined the term Spree-Athens , which is still used in Berlin to this day . When he died in 1713, he left 24 castles to his son Friedrich Wilhelm.

Overall, his reign can be counted among the richest epochs in Brandenburg's cultural history. The other side of this medal was a demand on public funds, which the productivity of Brandenburg-Prussia was not able to cope with. The resulting impoverishment of large sections of the population who had to bear the costs of the ventures is also viewed critically in historical research.

Schlueterhof in the Berlin Palace

Financial policy

Under his rule there were mismanagement and massive financial scandals from 1697 onwards to the Chief President (Prime Minister) Count Johann Kasimir Kolbe von Wartenberg , the Finance Minister Count Wittgenstein and Count Wartensleben (the three Wehs) .

The three counts, who held key positions with control over the army and finances, managed the country in a dire situation. Due to the monarch's constant new financial demands, first for the coronation, then for the palace buildings in Berlin, Potsdam, Köpenick, Lietzenburg and other places, the growing court , lavish celebrations, jewelery purchases and princely gifts, the court budget was constantly exceeded. However, Wartenberg and his colleagues could only hold out if they met the needs of the monarch. The three tapped into ever new sources of finance in the form of tax increases and inventions of new and absurd taxes that plundered the people of the country and left them poor. The productivity of Brandenburg-Prussia was not able to cope with these financial burdens. In the end, a bankrupt state remained with a debt of 20 million Reichstalers .

It is assumed that Friedrich was humanly dependent on Count von Wartenberg, as on his predecessor Danckelmann. In contrast to the innocent Danckelmann, Wartenberg used this for great personal enrichment, but did not have to spend ten years in prison like him . These severe cases of corruption put a heavy burden on the finances of the Prussian state. Friedrich's role in this matter is generally viewed critically.

Court keeping

Frederick's policy was based on a strong, recognized army and a brilliant court that was to compete with the richest countries in Europe. This seemed to him the outward embodiment of a dignity that should equate him with the highest rulers of Europe. The image of the prodigal on the royal throne, which emerged in earlier research, cannot, however, be maintained in this form. In historical research, this image was largely shaped by the negative written statements of his grandson, Frederick II .

Despite the very high court costs, which in 1712 amounted to 561,000 thalers with a state budget of 4 million thalers, in the 18th century representation (which included festivals, castles, art subsidies, but also the procurement of exotic animals for the so-called " Hetzgarten ") an important power factor with which a prince or king expressed how much power he possessed. Frederick I was thus only a child of his time, which explains his apparent extravagance.

Shortly after the funeral in 1713, his son, the soldier king, forbade all pomp and pomp and thus caused artists and craftsmen to leave Berlin and Prussia. The soloists of the court orchestra went to Köthen , where they were welcomed by Johann Sebastian Bach .

rating

Frederick I was neglected by historiography. So he always stood in the shadow of his father, the Great Elector, his son, the Soldier King, and his grandson Frederick the Great .

Friedrich was already accused of wasting money by his contemporaries during his lifetime. The written statements of his grandson Friedrich II, a representative of enlightened absolutism , about his grandfather represented a formative research opinion for the history . In his historical work History of my Time , published in 1750, the grandfather described the grandfather as a foolish spendthrift.

“Friedrich was indeed without firmness, vain and lustful, but not without benevolence and good-naturedness, but on the whole big in small things and small in big things. His misfortune was that in the story he was placed between a father and a son, both of whom were superior to him in spiritual powers. He was more concerned with the dazzling shine than with the useful, which is simply dignified. He sacrificed 30,000 subjects in the various wars of the emperor and the allies in order to obtain the royal crown. And he only wanted her so ardently because he wanted to satisfy his penchant for ceremonies and justify his lavish pomp on sham reasons. He showed rulership and generosity. But at what price did he buy the pleasure of satisfying his secret desires? "

Considered largely uncritically, Friedrich's judgment was generally adopted and represented by historical research well into the 20th century. Only a few representations before 1945 did without Friedrich's reduction and uncritical emphasis on the basic motif “vanity”.

In the German Empire, contemporaries at the bicentenary of the Kingdom of Prussia were embarrassed by the circumstances of the elevation of the rank of Hohenzollern, namely the self-coronation of Frederick I and the pomp in 1701. In Prussian-German historiography, Frederick's foreign policy also moved away from the northern theater of war to keep away and to concentrate all forces on the war against France, heavily criticized. Johann Gustav Droysen judged the system of Frederick I in his work History of Prussian Politics (IV., 1874):

“So strangely the Prussian power and its actions are disintegrating: in the west war without politics, in the east politics without an army. ... Under Friedrich's father, the Great Elector, the government would have led to different results. "

The idea behind it was the attempt to project the national dreams of the 19th and early 20th centuries back onto the reality of the early 18th century. This is how Ernst Berner judged in From the correspondence of Friedrich I of Prussia and his family , Berlin 1901:

"We also complain that he (Friedrich) did not use the opportunity of the Northern War to recapture Pomerania and the German seaside."

In the writing of history after 1945, the overall picture of Friedrich changed, so that the main points of criticism were viewed more differently and placed more in the context of the time of Frederick I. She endeavors to lead Friedrich I out of the shadow in which his grandson Friedrich II had put him and, following on from him, almost all of Brandenburg-Prussian historiography. The publicist Sebastian Haffner stated in his book: Preußen ohne Legende (1979) about the evaluation of Friedrich by his grandson: That is, with respect, a superficial judgment . Current historians rate Friedrich's government balance sheet more positively. In doing so, they emphasize that Frederick's outstanding successes were the preservation and consolidation of the continuum in the development of the state and also in the area of constitutional and administrative law.

memory

The Collegium Fridericianum received his name at his coronation .

In Berlin, a statue created by Andreas Schlüter in 1698 in front of Charlottenburg Palace , a cenotaph in the cathedral , also made by Schlüter, and a sculpture on the Charlottenburg Gate designed by Heinrich Baucke in 1908 remind of Friedrich I. A statue originally created by Ludwig Brunow in 1884 for the Hall of Fame The statue of the king is now in Hohenzollern Castle . On the Neumarkt in Moers there is a monument to King Friedrich I, also erected by Baucke.

For the former Berliner Siegesallee , the sculptor Gustav Eberlein designed monument group 26 with a statue of Frederick I as the main figure. The figure shows the first Prussian king with an eagle-crowned scepter , the pommel of a king's sword and an allonge wig adorned with a laurel wreath in the pose of the sun king Louis XIV. With this pose, a wide cloak and richly embroidered skirt, Eberlein covered Friedrich's physical handicap ( Schiefer Fritz , see above). The busts of the architect Andreas Schlueter and Eberhard von Danckelman were assigned to the statue as secondary characters . The unveiling of the group took place on May 3, 1900. The monument has been preserved with contour damage and broken parts and has been kept in the Spandau Citadel since May 2009 .

Statue of Frederick I by Andreas Schlueter in front of Charlottenburg Palace (1698)

Cenotaph of Frederick I by Andreas Schlueter in the Berlin Cathedral (around 1713)

Statue of Frederick I by Ludwig Brunow at Hohenzollern Castle (1884)

Statue of Friedrich I by Heinrich Baucke on the Neumarkt in Moers (1902)

Statue of Friedrich I by Heinrich Baucke at the Charlottenburg Gate (1908)

progeny

First marriage: In 1679 he married Princess Elisabeth Henriette of Hessen-Kassel (1661–1683) in Potsdam .

- 1st child: Luise Dorothee (1680–1705) ⚭ 1700 Landgrave Friedrich von Hessen-Kassel

Second marriage: In 1684 he married Princess Sophie Charlotte of Hanover (1668–1705) in Herrenhausen .

- 2nd child: Friedrich August (1685–1686)

- 3rd child: Friedrich Wilhelm I (1688–1740) ⚭ 1706 Princess Sophie Dorothea of Hanover

Third marriage: In 1708 he married Duchess Sophie Luise von Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1685–1735) in Berlin , who remained childless.

literature

- Friedrich III., Elector of Brandenburg . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1877, pp. 627-635.

- Gerhard Oestreich : Friedrich I. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, ISBN 3-428-00186-9 , pp. 536-540 ( digitized version ).

- Heinz Ohff : Prussia's kings. Piper, Munich 2016, ISBN 9783492310048 . (Pp. 11–42)

- Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Diederichs, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-424-01319-6 .

- Linda Frey, Marsha Frey: Friedrich I, Prussia's first king. Styria, Graz and others 1984, ISBN 3-222-11521-4 .

- Heide Barmeyer (ed.): The Prussian rise in rank and coronation in 1701 in a German and European perspective. Peter Lang, Frankfurt / Main and others 2002, ISBN 3-631-38845-4 .

- Wolfgang Neugebauer : Friedrich III./I. (1688-1713). In: Frank-Lothar Kroll (Ed.): Prussia's rulers. From the first Hohenzollern to Wilhelm II. Munich 2000, 113–133.

- Hans-Joachim Neumann : Friedrich I. The first king of the Prussians. Berlin 2001, ISBN 978-3-86124-539-1 .

- German Historical Museum , Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens Berlin-Brandenburg (Hrsg.): Prussia 1701. A European history. Essays . Henschel, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-89487-388-4 (Volume II of the catalogs for the exhibition, Berlin 2001).

- Johannes Kunisch (ed.): Three hundred years of Prussian royal coronation. A conference documentation (= research on Brandenburg and Prussian history, supplement; NF vol. 6). Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-428-10796-9 .

- Frank Göse : Friedrich I. (1657-1713). A king in Prussia. Pustet, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7917-2455-3 .

- Karl Eduard Vehse: Prussian Kings. Private. Berlin court stories. Anaconda Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-938484-87-X , pp. 7–56.

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedrich I. in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Friedrich I in the German Digital Library

- Publications by and about Friedrich I in VD 17 .

- Friedrich I. - German biography

- Friedrich I. in Prussia - rbb Prussia Chronicle

- From elector to king - Deutschlandfunk

Remarks

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 81.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Karl Eduard Vehse: Prussian Kings. Private. Berlin court stories. Cologne 2006, pp. 7, 14.

- ^ Karl Friedrich Pauli: General Prussian State History, Seventh Volume , Halle 1767, p. 5.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, pp. 29–41.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Karl Eduard Vehse: Prussian Kings. Private. Berlin court stories. Cologne 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Karl Friedrich Pauli: General Prussian State History, Seventh Volume. Hall 1767, p. 5.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 59.

- ^ National Museums in Berlin: Köpenick Palace

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 81.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 85.

- ↑ Hans Bentzien: Under the Red and Black Eagle - History of Brandenburg-Prussia for everyone. Berlin 1992, p. 104.

- ^ Daniel Bellingradt: The moment of decision 1688. Formative forces of the Brandenburg foreign policy on the eve of the glorious revolution in England. In: Research on Brandenburg and Prussian History NF 16 (2006), pp. 139–170.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 93.

- ^ Werner Schmidt, Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg, King in Prussia . Diederichs, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-424-01319-6 , p. 117.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 162.

- ↑ a b Hans Bentzien: Under the Red and Black Eagle - History of Brandenburg-Prussia for everyone. Berlin 1992, p. 105.

- ↑ Acquisition of the Prussian royal crown in: Berliner Börsenzeitung , January 18, 1901.

- ^ Karl Eduard Vehse: Prussian Kings. Private. Berlin court stories. Cologne 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Karl Eduard Vehse: Prussian Kings. Private. Berlin court stories. Cologne 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 220.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 213.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 216.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 221.

- ^ Karl Eduard Vehse: Prussian Kings. Private. Berlin court stories. Cologne 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ This is the designation in the statute that came into force in 1699, see Academy of the Arts and University of the Arts (ed.): 300 years of the University of the Arts. "Art has never been owned by one person". An exhibition by the Akademie der Künste. Henschel, Berlin 1996 [exhibition catalog], ISBN 3-89487-255-1 , p. 31.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 107.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 110.

- ↑ a b Ingrid Mittenzwei, Erika Herzfeld: Brandenburg-Prussia 1648–1789. Berlin 1987, p. 180.

- ↑ Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, Volume 7, p. 680.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 210.

- ↑ Otto Ernst Kempen: The Spectacle of the House of Brandenburg. In: Prussia Yearbook - An Almanach. P. 19.

- ↑ Hans Bentzien: Under the Red and Black Eagle - History of Brandenburg-Prussia for everyone. Berlin 1992, p. 108.

- ↑ Otto Ernst Kempen: The Spectacle of the House of Brandenburg. In: Prussian Yearbook - An Almanach. P. 20.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 184.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 183.

- ^ Werner Schmidt: Friedrich I. Elector of Brandenburg. King in Prussia. Munich 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ Uta Lehnert: The Kaiser and the Siegesallee. Réclame Royale. Berlin 1998, p. 195 f.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Friedrich Wilhelm |

Elector of Brandenburg 1688–1713 |

Friedrich Wilhelm I. |

| New title created |

King in Prussia 1701–1713 |

Friedrich Wilhelm I. |

| Friedrich Wilhelm |

Duke in Prussia 1688–1701 |

Title increased |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Friedrich I. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | King Friedrich I in Prussia; Friedrich III. Elector of Brandenburg |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King in Prussia, Elector of Brandenburg |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 11, 1657 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Koenigsberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 25, 1713 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Berlin |