Huguenots

Huguenots is the name in use since 1560 for the French Protestants in pre-revolutionary France . Their belief was Calvinism , the teaching of John Calvin from the 1530s . Since the Edict of Nantes in 1598, the Huguenots were officially referred to as religionists ( religionnaires ), and their denomination was identified in state documents as the so-called Reformed religion ( Religion prétendue réformée , RPR) designated. According to Patrick Cabanel, the Huguenots made up around 2 million people or 12.5 percent of the total French population at the time; other authors such as Hans Hillerbrand assume 10 percent around 1572, which also results in 2 million people.

In the 1520s, early Protestantism was only tolerated in the circle of the intellectuals around Margaret of Angoulême ( Cénacle de Meaux , "Circle of Meaux "). In general, the powerful Catholic clergy immediately instituted severe persecution. The first execution is dated to 1523. From the poster affair in 1534, the practice of the Protestants' faith was suppressed by Francis I. The Protestant French were pushed underground and the first wave of refugees began. Despite suppressive measures, the Reformation was able to develop secretly.

Armed conflicts followed in the second half of the 16th century, known as the Huguenot Wars (1562–1598). On the other hand, there was also violence and rioting from some representatives on the Protestant side. Catholic churches and monasteries were destroyed or looted by angry supporters of Calvinism, including the cathedral of Soissons in 1567 and the Cîteaux monastery in 1589 . There were also massacres against Catholics such as B. the Michelade of Nîmes .

In 1589 the Huguenot Henry of Navarre ascended the throne of France . Until his abjuration in 1593, the Estates General acted because of the opposition of a large part of the nobles against the king. Through the provision of the Parlement of Paris, the loi salique demanded a Roman Catholic king. As a result, many refused to recognize Henry as king. The last supporter of the Catholic League , the Duke of Mercœur recognized Henry IV after a bribe of 4,300,000 livres .

After the Edict of Nantes in 1598 there was about twenty years of peace. During this time France was able to regain its supremacy in Europe and rise to the rank of colonial power .

In 1621, as a result of the developed French absolutism, Huguenot uprisings broke out, which ended with the grace edict of Alès in 1629. Louis XIII. withdrew the political and military rights that were regarded as the independence of the Huguenots within France ( Etat dans l'Etat ), but religious freedom was still guaranteed. Also in 1652 Louis XIV confirmed the clause of the Edict of Nantes, which guaranteed the religious freedom of the Reformed Protestants in France.

Strong persecutions began in 1661, which reached a climax under Louis XIV through the Edict of Fontainebleau from 1685 and triggered a wave of about a quarter of a million Huguenots to the Protestant areas of Europe and overseas. As a result, almost the entire kingdom of France was evacuated by the Huguenots. The only exception was the Cevennes in east-north Languedoc , which became the scene of the Cevennes War . Persecution in France ended with the Edict of Versailles in 1787 . After the end of the persecution and the entry into force of the French constitution of 1791 , the term Protestant became more and more popular; the term "Huguenots", on the other hand, usually refers to Calvinist believers at the time of their persecution in France.

All French Protestants are now a minority of around 3% in predominantly Catholic France . In 2012, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of France and the Reformed Church of France merged to form the United Protestant Church of France . The United Protestant Church of France has 250,000 Reformed Protestants, roughly 0.4% of the total French population.

etymology

The word Huguenots possibly goes back to the early New High German ( Alemannic ) term Confederate and thus shows connections to Geneva . It appears in the French first in the early 16th century in the form eygenot to refer to the followers of a political party in the Canton of Geneva , against the annexation sversuche of the Duke of Savoy fought and so in 1526 a covenant between Geneva and the Swiss locations Freiburg and Bern closed. These Eygenots or Eugenots were Catholics at the beginning, because Geneva was not reformed until 1536. In the second half of the 16th century it was used increasingly and in contrast to the Catholic Savoy in the sense of "Protestant, Reformed", including by the Prince of Condé in 1562 in the form aignos . The Geneva freedom fighter Besançon Hugues is also being considered as a godfather for the naming.

Another assumption sees the word origin in the designation "Huis Genooten" ( housemates ) for Flemish Protestants who studied the Bible in secret . The origin of the word can certainly not be deduced, but it is undisputed that the name did not come about as a self-designation of the believers, but as a term of derision, which was also intended to discredit.

Against this background, the following derivation of the term is finally offered: In some regions of France in the 16th century, for reasons of persecution, the Protestants could only meet in secret. They therefore went to their meeting points at night, many of which were outside the localities. This is where Dante's Divine Comedy , which was very famous in France at the time, plays it. In it, Dante meets the French King Hugues (Hugo) Capet wandering around in purgatory. In a speech the king describes himself as "the root of the evil tree" that has overshadowed Christianity. In analogy to this, the “wandering” Protestants are referred to as little Hugos, as “Huguenots”.

overview

Essentially, a western and a southern part ( Le Midi / Occitanien ) of France became the main area of the Reformation .

Among the Huguenot strongholds were the historical provinces of Aunis (with the capital La Rochelle ), Saintonge , Poitou , Limousin , Béarn (including Navarra ), Foix , Languedoc and Dauphiné (southernmost parts of both of these provinces remained Roman Catholic ). Aquitaine (including Labord , more Huguenot Gascon and more Roman Catholic Guyenne ), Angoumois and Auvergne were roughly equally divided . Anjou (mostly Saumurois ), Orléanais , La Marche , Bourbonnais , Nivernais , Touraine , Maine and Côtes-d'Armor (part of Brittany ) were influenced by Huguenots only to a small extent .

In 1704 only a north-eastern part of the Languedoc (especially Gard , Vivarais and Ardèche ) located in the mountains ( Cevennes ) and a part of the Dauphiné ( Drôme ) bordering these areas remained under the Reformed faith .

| year | Number of Huguenots in France |

|---|---|

| 1519 | None |

| 1560 | 1,800,000 |

| 1572 | 2,000,000 |

| 1610 | 1,200,000 |

| 1629 | 1,000,000 |

| 1661 | 900,000 |

| 1685 | 800,000 |

| 1700 | less than 200,000 |

The persecution is lifted with the Edict of Versailles in 1787.

| year | Number of Reformed Protestants in France |

|---|---|

| 1789 | less than 200,000 |

| 1851 | 481,000 |

| 2013 | 250,000 |

story

Beginnings of the Reformation in France

Around the time when the Reformation began in Germany through Luther's theses (1517), there was a situation in France in which Luther's ideas could fall on fertile ground:

Francis I , who had ruled France since 1515, had at this time increasingly expanded and rebuilt the Catholic Church into an administrative organ of the state: Since the Bologna Concordat in 1516 he had the right to fill the high offices of the French Church according to his own will . He used this skillfully to accommodate the French high nobility in the appropriate positions and to commit him in this way. The infrastructure of the church was for Franz also important:

your presence in every town and village, the high range that could achieve the pastors in their communities, and the church records in which the parishes baptisms , marriages and deaths recorded were elements he is responsible for administrative tasks, e.g. B. to publish edicts .

In Paris this secularization led to the contradiction of humanistic circles, in particular the circle around Erasmus of Rotterdam (Didier Érasme) and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (Jakob Faber). Around 1520, people began to discuss Luther's theses in these circles , which made the Holy Scriptures the standard of faith and called for the separation of state and church . Luther's theological theses were initially received rather positively by the royal family. The king's sister, Margaret of Navarre , and the Bishop of Bayonne , Jean du Bellay , as well as his brother Guillaume, were members of the group around Lefèvre.

Franz I, already very enlightened and open-minded, and probably influenced by his sister, was also not averse to the theological aspects of the beginning Reformation movement. For example, he held his protective hand over Lefèvre when a heresy trial was brought against him after a treatise on Mary Magdalene . Reforming the church from within, at least as far as theological interpretations are concerned, was nothing that Francis I should have feared.

The idea of the Reformation was initially allowed to gain a foothold in France around 1520. From the humanists he quickly found his way into the upper middle class , where the existing, far-reaching trade relations not only helped to spread goods quickly, but also ideas.

Beginning of persecution

Soon a Catholic counter-movement set in. Officials of the church saw their teachings and their power endangered by the emerging movement: Luther was excommunicated by the Pope in 1521, and the Sorbonne University in Paris condemned his teachings.

As a result, Francis I came under increasing pressure, for two reasons:

- The first was of an internal political nature, since the administration of the state was in the hands of the Catholic Church: after 1520 it quickly became clear that the Reformation was not just a theological matter that spread in the study of scholars, but that the theses began to attack the existing clerical (and closely related also the secular) power structure. Franz could have had no interest in the reformers now sawing the chairs of those nobles for whom he had just obtained ecclesiastical offices, dignities and sources of income and who were an essential pillar of his rule over France.

- Second, at this time Franz I was in a serious conflict with the Habsburgs , more precisely with the German Emperor Charles V. France was pinched by the Habsburgs over the Netherlands , Germany and Spain ; in northern Italy it was at open war with the Habsburgs. If Francis had allowed the Reformation to run free in France, he would have had the Pope against him, and Charles V, who had banished Luther from the empire in 1521 , would - then with the support of the Pope - have been unable to prevent an invasion of France . These foreign policy considerations also prompted Franz to distance himself from Protestantism.

So there were increasing reprisals against the Protestants, which expanded into the persecution of at least public Protestantism: The first execution of a French Protestant is documented for August 8, 1523: the Augustinian monk Jean Vallière was burned on a stake in Paris.

Underground Church

Protestantism was increasingly pushed into the underground until around 1530, as religious persecution by the Catholic side increased more and more. Some of the Protestants fled, including to the Reformed towns in Switzerland , where Ulrich Zwingli was in the process of completely disempowering the Catholic Church. However, when pushed into political extinction, the Protestants from the underground appeared increasingly provocative. The first major clashes between Catholics and Protestants occurred in 1534 over the Affaire des Placards , in which anti-Catholic posters were posted in Paris and four other cities. The Catholic mass was referred to therein as idolatry . Various statues of the Virgin Mary were defaced. After those responsible for this action were burned at the stake, relations between the two sides remained tense.

Around 1533, John Calvin joined Protestantism in Paris. Up to this point he too could be described as a Catholic humanist rather than a Reformed man. After a Protestant-tinged speech by Nicolas Cop , the rector of the University of Paris, which was most likely made with Calvin's participation, both had to flee Paris.

When the Lutheran movement was supposed to spread in Provence and the Dauphiné , Francis I suppressed the Waldensians (which had existed there since the High Middle Ages ) . The main event is the Mérindol massacre in 1545.

But despite the repression, the movement was still gaining traction. In 1546 the first Protestant congregation in France was formed in Meaux . In 1559 the first national synod of the Reformed Christians of France took place in Paris. Fifteen parishes sent their delegates. A church ordinance and a creed were adopted . The church ordinance that Calvin had created in 1541 based on his understanding of the New Testament and the Geneva Constitution was adopted. In addition to the offices of pastors ( pasteurs ), doctors ( docteurs ) and deacons ( diacres ), it provided for that of elders ( anciens ; presbyters ), who were also elected members of the city council of Geneva. As a persecuted minority church, the French Reformed could not rely on secular authorities (like the Anabaptists, they practiced the separation of church and state from the beginning). Therefore, the adult male parishioners chose the (church) elders, lay volunteers, from their own ranks. The French Protestant Christians added synods at regional and national level to this presbyterial system, the members of which were also elected by the parishioners. This gave the laity a very powerful influence in the governance of the Church at all levels. This democratic church order, which was adopted by many other Reformed churches (e.g. on the Lower Rhine, in the Netherlands and in Scotland), was one of the most important consequences of Luther's teaching of the “general priesthood of all believers ”, which became Protestant common property. At the next French national synod, which took place two years later, around 2,000 parishes were already represented. By the early 1560s, the underground Reformed Churches had about two million followers, about ten percent of the total French population.

These Reformed communities were no longer Lutheran: the persecution had created close ties between the French Reformed and Calvin, who lived in Geneva. Between 1535 and 1560, Calvinism increasingly penetrated French Protestantism, and it was Calvinism that attracted dissidents. Now the name "Huguenots" also came up.

In 1562 the Geneva Psalter was written, the lyrics of which became an encouragement and consolation for many Huguenots in difficult life situations. From 1564 the Reformed were no longer admitted to the universities. So they only had their own academies and seminars in Montauban , Montpellier , Nîmes , Orange , Orthez , Saumur and Sedan .

Huguenot Wars

Francis I died in 1547 and his son Henry II ascended the French throne. He continued the repression against the Huguenots undiminished. Around this time the Habsburg Empire began to disintegrate into a large number of small states : Emperor Charles V no longer got the Reformation under control, and the compromise of " Cuius regio, eius religio " (whose territory, whose religion) did the rest to divide of the empire.

Heinrich II wanted to prevent similar conditions as in Germany in any case. Increasingly, aristocrats had now joined the Huguenots, and an agreement based on the Augsburg principle for France would have seriously damaged the successful centralization of France under Francis I. Political discrimination against Protestantism in France finally began .

A new institution and three edicts were enough to suppress the Huguenots more and more:

- The basis was the establishment of the Chambre ardente in Paris, a chamber that persecuted the Huguenot MPs (see Inquisition ). Heinrich set up this chamber in the first year of his reign. In June 1551 this principle was extended to the provincial parliaments in the Edict of Châteaubriant .

- The Edict of Compiègne followed on July 24, 1557: Protestants “ who disrupted order in any way ” were placed under secular jurisdiction; Heinrich still left the conviction for heresy in the hands of the Church.

- Heinrich put the final point on June 2, 1559 in the Edict of Écouen : From now on, the courts for heresy were only allowed to impose the death penalty. Heinrich died shortly after the edict.

The expulsion that had begun continued under Heinrich's son Franz II . In 1562 Catholic soldiers attacked Protestants at Vassy during a service . In 1567, a Protestant crowd murdered 24 Catholic clergy in the so-called Michelade of Nîmes . The Bartholomew Night 23./24. August 1572 in Paris again triggered numerous flows of refugees. Important Protestant figures were murdered. The death toll was around 3,000 in Paris and between 10,000 and 30,000 in the countryside. The killing of children, women, old people and boys went on for two long months.

In 1589, Henry IV became the first Bourbon and the only Calvinist king of France . To end the wars of religion and gain recognition from French Catholics, he converted to Catholicism in 1593. He should have said: "Paris is worth a fair ".

Finally, Henry IV achieved a temporary calming of the situation with the Edict of Nantes in 1598 , which lasted almost 23 years. During this time France was able to regain its supremacy in Europe and also rise as a colonial power . A ministry for the so-called Reformed religion was established. The State Secretary of the so-called Reformed Religion ( Secrétaire d'État de la Religion Prétendue Réformée ) was the main post of the ministry, which existed from 1598 to 1749. In 1749 this ministry was merged with the ministry of the royal house ( Département de la Maison du Roi ). The first Secretary of State was Pierre Forget de Fresnes , the chief author of the Edict of Nantes. The other state secretaries, from 1610, were always members of the Phélypeaux family .

Situation of the Huguenots in the French colonies

From 1562 to 1564 the Huguenots tried to found a colony ( French Florida ) in what is now the United States (see also Fort Caroline ). This only existed for a year before it was wiped out by the Spaniards. From 1555 to 1567 the Huguenots tried to found a colony in what is now Brazil ( France Antarctique ). In 1567 the local Fort Coligny was conquered and thus the colony was wiped out by the Portuguese. Both attempts were not independent projects, but intended the establishment of formal colonies that should belong to the Kingdom of France (even if the settlers had understood these new colonies as overseas refuges for the persecuted French Reformed).

Initially, the Huguenots were settled in New France (first settled around 1600) together with Catholics. Many settled in Acadia (especially in the villages of Beaubassin and Grand-Pré ). In 1627, Richelieu gave direct control of New France to the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France . According to a document of the Compagnie New France could "only Roman Catholic to be" . Because of this determination, many Huguenot settlers emigrated to the English Thirteen Colonies and New Netherlands .

According to the historian Pierre Miquel , thousands of Huguenots were deported to the penal colonies of the French West Indies ( Guadeloupe , St. Lucia , St. Kitts , Martinique ) in the Caribbean and to French Guiana (capital Cayenne ) in South America . Most were able to flee to the mainland. Rodrigues in the Indian Ocean was first colonized by an expedition by the Huguenot adventurer François Leguat . Most of the settlers were also Roman Catholic.

Huguenot uprisings under Louis XIII.

From 1610 to 1617, power in the Kingdom of France was effectively held by Maria de 'Medici and her Italian favorites. Under the regent Maria, the Edict of Nantes remained in force and was even promoted directly by her. This did not change, even if the court Italians, who exerted a great influence on Maria, wanted to abolish the edict. Among them were the lady-in-waiting Leonora Galigaï and the adventurer Concino Concini .

When Louis XIII. took power, Huguenot uprisings broke out. His first minister, Charles d'Albert, duc de Luynes , initially did not want to intervene militarily against them, but then changed his mind (allegedly because the king insisted on it) and went against the Huguenots together with him.

In the years 1621 to 1629 Ludwig XIII. against the military power of the Protestants and conquered the city of La Rochelle from them in 1628 . In Alès' edict of grace of June 28, 1629, the Huguenots were finally eliminated as a political power factor, although their religious freedom was still guaranteed by the king. The real power at this time lay with Cardinal Richelieu . His main motivation in his action against the Huguenots in the years 1624 to 1628 was the strengthening of French absolutism and not religious reasons. At the European level, the Kingdom of France interfered in the Thirty Years War . Richelieu led an alliance with Sweden and other Protestant states in the Holy Roman Empire against the emperor, his Habsburg monarchy and Catholic allies. From 1635 Richelieu declared war directly on the emperor. In order to be able to maintain the alliance with Sweden, Richelieu had to maintain the position of the Huguenots and guarantee the freedom of the Protestants to practice their faith. When France was now leading the Protestant side of the Thirty Years' War militarily, Richelieu turned away from any kind of persecution against the Huguenots.

Temporary standstill

Between 1643 and 1661, real power in the Kingdom of France was in the hands of Anna of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin . Domestic policy towards the Huguenots remained as Richelieu had practiced. Anna and Mazarin continued the Franco-Spanish War and also had to take action against the Frondes . These were enough problems to take action against the Huguenots, who had been deprived of their power as early as 1629.

Dragonades under Louis XIV.

Starting in 1661, the "Sun King" Louis XIV initiated a large-scale systematic persecution of Protestants associated with conversion and missionary activities, which he combined with a ban on emigration in 1669 due to the waves of refugees that began and which since 1681 in the notorious dragoons (billeting of soldiers in the apartments of the Huguenots) found a climax. The many government restrictions and harassment in the years 1656 to 1679 drove around 680 preachers to flee and 590 churches were destroyed, despite the prohibition. Despite the travel ban, around 200,000 Huguenots left their homeland over the course of about fifty years. They looked like the children of Israel who had to leave Egypt. With them, France lost its cultural and economic diversity and strength.

Edict of Fontainebleau

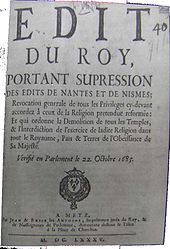

In the Edict of Fontainebleau 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes. The edict is said to have been written on the advice of his favorite and secret wife Françoise d'Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon . The edict, as well as the dragonades, were successfully implemented under one of the most gifted ministers of Louis XIV - First Minister and Minister of War François Michel Le Tellier de Louvois . Foreign Minister Charles Colbert, marquis de Croissy was responsible for presenting the consequences of the edict to the world public. The international situation also favored the revocation. The Chancellor of France Louis Boucherat, comte de Compans was responsible for the legal introduction of the edict.

The State Secretary of the so-called Reformed Religion ( Secrétaire d'État de la Religion Prétendue Réformée ) was currently Balthazar Phélypeaux de Châteauneuf, marquis de Châteauneuf et Tanlay . He countersigned the edict. There were also important figures such as Charles Colbert, marquis de Croissy and Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban who viewed the revocation as a mistake by the king.

Exercising the Protestant Reformed faith has since been a criminal offense. As a result, 600,000 Huguenots who had not fled went to an underground church . Since the members of the Protestant upper class, including most of the clergy, fled abroad, the church was led by lay pastors who felt called by divine inspiration. That is why prophetic and ecstatic forms of religiosity emerged. They took effect in the Inspired Movement across Europe.

The edict was not valid in the territories of France newly acquired by Louis XIV. The king issued edicts that guaranteed even the long persecuted Mennonites special rights in Alsace .

| fate | number |

|---|---|

| Remained convert to Catholicism | more than 400,000 |

| Remain, do not convert to Catholicism | less than 200,000 |

| Fled abroad | about 200,000 |

| Total number of people affected | about 800,000 |

Emigration after 1685

After the Edict of Fontainebleau was signed in 1685, around 200,000 Huguenots out of a total of 800,000 left the Kingdom of France.

The rulers of the neighboring countries readily welcomed the dispossessed Huguenots, who belonged to the most productive strata of society. They were granted privileges and credits , which in turn aroused incomprehension, envy and hostility in the rest of the population. In addition, as Reformed people they came across Lutherans, so that they again embodied a religious minority .

Countries that became new homes for around 200,000 Huguenots included Switzerland, the Netherlands, England, Ireland, North America and some territories of the Holy Roman Empire . Huguenots also settled in Scandinavian countries such as Copenhagen and Fredericia in Denmark , Stockholm in Sweden , Russia and South Africa.

Most of the emigrants (around 50,000) emigrated to the British Isles. As early as 1550, a French Protestant church was founded in Soho (London) by Royal Charter . Huguenot centers in England included London, some places in Kent and Bedfordshire and Norwich . In the course of the plantation (settlement of Protestant settlers) some Huguenots also came to Ulster (Ireland). There they made a major contribution to the establishment of the linen industry in the region around Lisburn , which, alongside shipbuilding, was the most important industry in Ulster for a long time. A Huguenot neighborhood can still be found in Cork City today . There is a Huguenot cemetery in Dublin (near St. Stephen's Green ).

The Huguenots often ensured an economic boom in the countries to which they immigrated, especially agriculture . They opened up the cultural and intellectual life. They significantly developed the textile and silk manufactories, the stump weaving and trade ( silkworm breeding ), introduced tobacco cultivation in Germany (mainly in the Uckermark with the center of Schwedt / Oder ) and were active in the manufacture and trade of jewelry.

| Escape destination | number |

|---|---|

| Republic of the Seven United Provinces | 50,000 |

| Germany | 50,000 (including 20,000 Brandenburg-Prussia ) |

| England | 45,000 |

| Old Confederation | 20,000 |

| Sweden | 20,000 |

| other escape destinations | 10,000 (mainly Denmark-Norway ) |

| Thirteen colonies | 4,800 |

| French Canada | 800 |

| Dutch Cape Colony | 200 |

| Total number of people affected | about 200,000 |

Camisard war at the beginning of the 18th century

In view of the revocation , some of the Huguenots in the Cevennes resisted ( Camisards ). Jean Cavalier , Pierre Roland Laporte and Abraham Mazel were the leaders of the 3,000 so-called Camisards. From 1703 to 1706 there was a civil war there with around 30,000 dead, after which Louis XIV and his 25,000 soldiers had 466 villages razed to the ground. Singing psalms and reading the Bible was punishable by heavy penalties. Many people were forcibly converted to Catholicism, also to avoid the dreaded dragons. But Protestantism could not be exterminated because the persecuted and punished Protestants were venerated as martyrs. In 1715 the "Church of the Desert" was founded under the leadership of Antoine Court , which had called off the violence. Mostly covered and hidden as crypto-Protestants survived in the south of France around 400,000 Protestants. Of these, fewer than 200,000 remained public Protestants. These were mostly camisards in the Cevennes. There are still Protestants in the Cevennes today .

Tolerance and equality in France

It was not until 1787 that the Edict of Versailles under Louis XVI. created a new, open opportunity for Protestant life in France. From 1790, some goods were returned to re-naturalized Protestants, which was to last until 1927. However, not too many Huguenots returned to France because they had often integrated and assimilated economically and socially in the respective countries. In 1792 the first new Protestant church was built in Nîmes, and in 1804 Protestants were given equal rights. But it took decades for the new law to be implemented across the country. In 1852 a society for the history of French Protestantism , the Société de l'Histoire du Protestantisme Français SHPF, was founded. In 1872 the first reformed national synod since 1659 could take place. The proportion of Protestants in France remained small, however, the census shows a population share of 1.4 (members) to 3.6% (sympathizers).

Huguenots abroad

Huguenots in America

Huguenots who lived in La Rochelle and elsewhere in western France also chose America as a destination. From 1670 to 1720 about 4,800 religious refugees crossed the Atlantic and reached the cities of Boston , New Rochelle , New York and Charleston on the east coast of the English colony of America. About 800 Protestants tried their luck in Canada, the northern French colony. As early as 1654 the Protestant pastor Pierre Daillé, who was first professor of theology in Saumur , France , founded the first Reformed church in New York.

Huguenots in Germany

In 1597 Huguenots settled in Hanau and built Hanau Neustadt, in 1604 Huguenots founded the village of Ludweiler with the permission of Count Ludwig II of Nassau-Saarbrücken .

From 1670 to 1720, especially around 1685, 40,000 to 50,000 Huguenots fled to Germany and formed around 200 Reformed parishes there. About 20,000 of them went to Brandenburg-Prussia , where the Reformed Elector Friedrich Wilhelm granted them special privileges with the Edict of Potsdam . Two regiments were formed by Huguenots: the Varenne foot regiment (1686) and the Wylich foot regiment (1688) . The Brandenburg ambassador in Paris, Ezekiel Spanheim , helped many emigrants to leave the country.

Almost 10,000 Huguenots settled in Baden ( Friedrichstal , Neureut ), Franconia ( Principality of Bayreuth and the Principality of Ansbach , today part of Bavaria with 3,200 refugees), in the Landgraviate of Hessen-Kassel (7,500 people), in the County of Nassau-Dillenburg and in Württemberg (2,500 people) about. A further 3,400 religious refugees moved to the Rhine-Main area ( Hanau ), to the counties of the Wetterau Counts Association , to what is now Saarland and to the Palatinate with Zweibrücken . Around 1,500 Huguenots found a new home in Hamburg , Bremen and Lower Saxony . About 300 Huguenots at the court of the Duke found George William of Brunswick and Luneburg , his wife Eleonore d'Olbreuse even Huguenot was in Celle recording and received a church of their own . Huguenots founded Neu-Isenburg in the county of Isenburg-Offenbach in 1699, and many settled in their Offenbach residence . Most of the refugees settled in their Refuge , as their new home was called, from 1697 onwards .

Huguenots in England

A Church of Foreigners was recognized in London as early as 1550 . From 1553 to 1568, when Mary I ruled, Protestants were hardly ever accepted in England. Shortly thereafter, 6,000 to 7,000 Huguenot craftsmen and traders came to England from the west and north coast of France. Around 1685, when the wave of refugees was at its peak, around 45,000 religious refugees reached the British island. The majority of them settled in London, Canterbury and the east of England.

Huguenots in the Netherlands

The cremation of Johannes van Esschen and Hendrik Vos , two Augustinian monks from Antwerp who had become evangelicals in 1523 in Brussels , marked the beginning of the persecution in the southern Netherlands. As a result, it led to the flight of around 40,000 Protestants to Amsterdam and Emden . From 1544 to 1648, around 60,000 Evangelical Walloons who lived in the southern province of the Netherlands followed to the northern province. From 1680 about 50,000 Huguenots and another 100,000 Flemings fled to the northern Netherlands to freely practice their faith. In addition to the city of Amsterdam, the University of Leiden also became a focal point for evangelical refugees.

Huguenots in Switzerland

150,000 or more Huguenots crossed Switzerland on their way to Germany and other European countries of exile. They came in two waves, the first from 1540 to 1590 and the second from 1680 to 1690, with the highest number of people passing the country in 1687. A particularly large number of Huguenots reached Geneva (up to 28,000 refugees out of a population of 12,000) and Zurich (23,000 out of 10,000 in the years 1683 to 1688). The city of Lausanne also provided great support with travel money for thousands of Huguenots and Neuchâtel with the naturalization of 5,300 people. About 20,000 religious refugees stayed permanently in Switzerland, they settled in many cities and also formed their own reformed, French-speaking parishes in Aarau , Basel , Bern , Biel , Chur , St. Gallen , Schaffhausen and Winterthur . With their professional knowledge, educated Huguenots made a significant contribution to the development of banks, textile production and handicrafts.

Huguenots in South Africa

The escape from France led some Huguenots via the Netherlands to the southern tip of Africa. The Voorschoten was the first ship to sail from Delfshaven with several Huguenot families on board on December 31, 1687 in the direction of the Cape of Good Hope . It reached the Cape region on April 13 of the following year. Some of the fellow travelers carried vines with them and brought a noticeable upswing in viticulture in South Africa . Around 200 Huguenots came to South Africa in this way and founded the town of Franschhoek . Numerous other ships followed by 1749, bringing Huguenots to South Africa.

Branch offices in Germany today

Today Huguenot communities exist in the following places (list not complete):

Hesse

- Bad Karlshafen , North Hesse, today the location of the German Huguenot Museum , the German Huguenot Center with a genealogical research facility and the library and image archive of the German Huguenot Society .

- Weser Valley (Waldenserorte Gewissenruh , Gottstreu )

- Frankenau (places: Louisendorf , Ellershausen )

- Schwabendorf

- Hertingshausen (Wohratal)

- Walloon-Dutch Church in Hanau

- Friedrichsdorf (1890 founding place of the German Huguenot Society, current seat in Bad Karlshafen )

- Hofgeismar (places: Carlsdorf , Kelze , Schöneberg , Friedrichsdorf )

- Obermeiser

- Immenhausen (Place: Mariendorf )

- Wolfhagen ( Leckringhausen )

- Helsa (place: St. Ottilien)

- kassel

- Mörfelden-Walldorf ( Walldorf district )

- Neu-Isenburg

- Ober-Ramstadt (districts Rohrbach and Wembach-Hahn)

- Hunger

- French Reformed Church in Offenbach am Main

- Schwalmstadt-Frankenhain

- Ehringshausen (places: Daubhausen and Greifenthal )

Independent Huguenot-Waldensian communities founded

- In the old district of Frankenberg

- Louisendorf (village with Old French language preserved until 1990)

- Meadow field

- In today's district of Kassel

- Bad Karlshafen

- Carlsdorf

- Mariendorf (Immenhausen)

- Kelze

- Schöneberg (Hofgeismar)

- Peace of mind

- Godly

- Friedrichsdorf (Hofgeismar)

- St. Ottilien

- Hofgeismar , Neustädter Church

- Leckringhausen

- Friedrichsfeld (Trendelburg)

- In the old district of Wolfhagen, Huguenots settled in the already existing Hessian town of Zierenberg and in the municipality of Dörnberg

- In the rest of Hesse

- District of Marburg-Biedenkopf (places: Schwabendorf , Todenhausen and Wolfskaute ) as of 2006;

- Daubhausen

- Greifenthal (founded by Wilhelm Moritz Graf zu Solms-Greifenstein )

- Hertingshausen

- Friedrichsdorf (founded by Landgrave Friedrich )

- Kassel , Oberneustadt (own district)

to bathe

- Mannheim-Friedrichsfeld (then Electoral Palatinate )

- Friedrichstal (part of Stutensee since 1975 )

- Palmbach (since 1975 part of Karlsruhe )

- Mutschelbach (since 1975 part of Karlsbad )

- Welschneureut (since 1935 united with Teutschneureut to Neureut , this part of Karlsruhe since 1975 )

Bavaria

Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

Hamburg

In Hamburg and in the Hamburg district of Altona there were French Reformed congregations until 1976, which in 1976 merged with the German Reformed to form the Evangelical Reformed Church in Hamburg .

Saarland

Württemberg

- Pinache (since 1975 district of Wiernsheim )

- Serres (since 1975 district of Wiernsheim )

- Großvillars (part of Oberderdingen since 1972 )

- Kleinvillars (district of Knittlingen since 1972 )

- Corres (district of Ötisheim )

- Perouse (district of Rutesheim since 1972 )

- Neuhengstett (since 1974 part of Althengstett )

- Nordhausen (Nordheim)

Berlin and Brandenburg

In Berlin and Brandenburg the French Reformed congregations belong to the Evangelical Church Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia and form the Reformed Church District. This church district took on a French-speaking congregation in 1997 (Communauté protestante francophone de Berlin et environs).

In Berlin, the names of districts such as Moabit and French Buchholz and Straßen and in the Oderbruch the place names Vevais , Beauregard and Croustillier still recall the Huguenots who settled in Prussia . An alternative name, especially in the 19th century, was refugies .

literature

Non-fiction

German speaking

- Andreas Jakob: Huguenots in Franconia. More than an initial spark? in: Andrea M. Kluxen / Julia Krieger / Andrea May (Ed.): Strangers in Franconia. Migration and Culture Transfer (History and Culture in Middle Franconia, Vol. 4), Würzburg 2016, pp. 157–212. ISSN 2190-4847 , ISBN 978-3-95650-137-1 .

- Manuela Böhm (Ed.): Huguenots between migration and integration. New research on the refuge in Berlin and Brandenburg. Metropol, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-936411-73-5 ( review ).

- Guido Braun, Susanne Lachenicht (ed.): Huguenots and the German territorial states. Immigration Policy and Integration Processes. Oldenbourg, Munich 2007 (Paris Historical Studies, 82), ISBN 978-3-486-58181-2 Online perspectivia.net .

- Jochen Desel : Huguenots. French religious refugees all over the world. 2nd edition, German Huguenot Society, Bad Karlshafen 2005, ISBN 3-930481-18-9 .

- Gerhard Fischer: The Huguenots in Berlin , Hentrich & Hentrich Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-941450-11-0 .

- Barbara Dölemeyer : The Huguenots (Urban pocket books; 615). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-018841-0 .

- Ingrid and Klaus Brandenburg: Huguenots: History of a Martyrdom. Panorama, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-926642-17-3 .

- Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots. History, Belief and Impact. 4th, revised edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-374-02260-1 ( review (PDF)).

- Ute Lotz-Heumann: Reformed denominational migration: The Huguenots. In: European History Online , ed. from the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2012, accessed on: March 25, 2021.

- Ulrich Niggemann: Huguenots (UTB Profile). Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-8252-3437-9 ( review ).

- Andreas Jakob: The legend of the 'Huguenot cities'. German planned cities of the 16th and 17th centuries in: Volker Himmelein (Ed.): 'Clear and bright like a rule'. Planned cities of the modern age from the 16th to the 18th century (exhibition catalog Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe 1990), Karlsruhe 1990, pp. 181-198, ISBN 3-7650-9026-3 .

- Willi Stubenvoll: The German Huguenot Cities, Frankfurt am Main 1990.

- Catalog: Immigration to Germany - The Huguenots. For the German Historical Museum, edited by Sabine and Hans Ottomeyer. German Historical Museum Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86102-135-8 (museum edition), ISBN 3-938832-01-0 (book trade edition ).

French speaking

- Henri Bosc: La guerre des Cévennes . Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier 1985/92, ISBN 2-85998-023-7 (6 vols.)

- Philippe Joutard: Les Camisards . Gallimard, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-07-029411-0 .

- Philippe Joutard: La légende des Camisards Une sensibilité au passé . Gallimard, Paris 1985, ISBN 2-07-029638-5 .

- Henry Mouysset: Les premiers Camisards. Juliet 1702 . Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier 1985, ISBN 2-85998-259-0 .

- Pierre Rolland: Dictionnaire des Camisards . Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier 1995, ISBN 2-85998-147-0 .

English speaking

- Anne Dunan-Page: The Religious Culture of the Huguenots. 1660-1750. Ashgate, Aldershot 2006, ISBN 0-7546-5495-8 .

- David Horton: French Huguenots in English Speaking Lands. Lang, New York 2000, ISBN 0-8204-4542-8 .

- Neil Kamil: Fortress of the Soul. Violence, Metaphysics and Material Life in the Huguenots' New World, 1517-1751. University Press, Baltimore MD 2005, ISBN 0-8018-7390-8 .

- Abraham D. Lavender: French Huguenots. From Mediterranean Catholics to White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Lang, New York 1990, ISBN 0-8204-1136-1 .

- Brian E. Strayer: Huguenots and Camisards as Aliens in France, 1598–1789. The Struggle for Religious Toleration. Mellen, Lewiston NY 2001, ISBN 0-7734-7370-X .

- David Trim (Ed.): The Huguenots. History and Memory in Transnational Context. Essays in Honor and Memory of Walter C. Utt. Brill, Leiden et al. 2011 (Studies in the History of Christian Traditions, Vol. 156), ISBN 978-90-04-20775-2 (preview on Google Books).

Fiction

- Taylor Caldwell : All the power in the world. Novel. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0246-4 .

- Victoria Holt : The Bloody Night of Paris. Novel. Hestia, Rastatt 1995, ISBN 3-89457-068-7 .

- Heinrich Mann: The youth of the king Henri Quatre , novel.

- Ursula Meyer-Nobs: The galley convict. A novel based on the experience report by Jakob Maler. Zytglogge, Gümlingen 2003, ISBN 3-7296-0649-2 .

- Uwe Otto : The Laurents. The novel by a Berlin Huguenot family. Droemer / Knaur, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-426-00787-8 .

- Emil-Ernst Rommer: Blanche Gamond or the crown of life. Hänssler, Holzgerlingen 2002, ISBN 3-7751-3842-0 .

Web links

- Literature on the Huguenots in the catalog of the German National Library

- German Huguenot Society

- German Huguenot Museum, Bad Karlshafen

- Library for Huguenot History (BfHG)

- Website calvin.de of the Evangelical Church in Germany EKD, 2019

- European cultural long-distance hiking trail Huguenot and Waldensian trails

- Musée virtuel du protestantisme Virtual Museum of Protestantism (in French, English and German)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Patrick Cabanel: Histoire des protestants en France . XVIe-XXIe siècle. No. 87 . Fayard , 2012.

- ↑ Marcel Couturier, "Le sacre du roi Henri IV en 1594", Bulletin de la Société archéologique d'Eure-et-Loir, no 40, January 1994

- ^ Philippe Emmanuel de Lorraine, duc de Mercœur, prétendant au Duché de Bretagne - Histoire locale de la commune de Glénac dans le Morbihan .

- ^ Emil Dönges: Wilhelm Farel. A reformer of French-speaking Switzerland. Through 2nd edition (1st edition 1897). Ernst-Paulus-Verlag, Neustadt / Weinstrasse 1993, p. 104.

- ↑ evidence!

- ^ Dante: Divina commedia , Purgatorio 20, 16–123

- ↑ https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_POPU_901_0215--official-statistics-on-religion-protesta.htm#

- ↑ Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots. History, Belief and Impact. 4th, revised edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-374-02260-1 , pp. 61 to 67.

- ↑ Beatrix Siering, Sandra Thürmann, Claudia Bandholtz, Christiane Stuff: 1685: The invention of the green card - the Huguenots are coming . In: Birgit Kletzin (ed.): Strangers in Brandenburg - from Huguenots, socialist contract workers and right-wing enemy image (= region - nation - Europe ). tape 17 . Lit, Münster 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6331-X , p. 22 ( Google Books [accessed January 17, 2012]).

- ^ Reformed churches in Denmark

- ^ French Reformed Congregation Stockholm

- ↑ hugenotten.de

- ↑ Huguenots

- ↑ Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots. History, Belief and Impact. 4th, revised edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-374-02260-1 , pp. 72 to 77

- ↑ Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots. History, Belief and Impact. 4th, revised edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-374-02260-1 , pp. 78 to 82

- ↑ website of the Evangelical Church in Germany EKD 2019 calvin.de,

- ^ The Huguenot refugee movement to America , Musée virtuel du protestantisme

- ↑ On Prussia in summary Ursula Fuhrich-Grubert: Minorities in Prussia. The Huguenots as an example. In: Wolfgang Neugebauer (Ed.): Handbook of Prussian History. Vol. 1: The 17th and 18th centuries and major themes in the history of Prussia. De Gruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-014091-0 , pp. 1125-1224 (preview on Google Books).

- ↑ Dirk Van der Cruysse: Madame is a great craft, Liselotte von der Pfalz. A German princess at the court of the Sun King. From the French by Inge Leipold. 14th edition, Piper, Munich 2015, ISBN 3-492-22141-6 , p. 337.

- ↑ Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots. History, Belief and Impact. 4th, revised edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-374-02260-1 , pp. 101 to 117.

- ^ The Huguenot refugee movement to England , Musée virtuel du protestantisme

- ↑ Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots. History, Belief and Impact. 4th, revised edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-374-02260-1 , pp. 101 to 200.

- ↑ Danièle Tosato-Rigo: Protestant religious refugees. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Benedikt Meyer: The Huguenots. When the Protestants fled France en masse in the 17th century, around 20,000 Huguenots came to the Confederation. They revitalized the economy and the culture of their new home. Swiss National Museum, 2019

- ^ The Huguenot refugee movement to Switzerland , Musée virtuel du protestantisme

- ↑ Eberhard Gresch: The Huguenots. History, Belief and Impact. 4th, revised edition. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-374-02260-1 , pp. 194 to 197.

- ↑ history. In: Erk-hamburg.de. Evangelical Reformed Church in Hamburg, accessed on August 12, 2015 .