Old Confederation

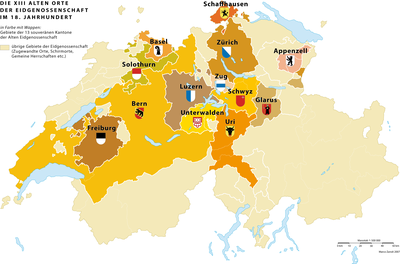

As Old Confederation is Swiss Confederation referred to in the form as of the first alliances in 13/14. Century until the French invasion and the beginning of the Helvetic Republic in 1798. From a constitutional point of view , the old confederation was a loose confederation of states , which was strongly influenced by the power interests of the individual members. It consisted of the autonomous member states designated as "places" ( eight old places , from 1513 thirteen old places ) with their respective subject areas as well as the assigned places and the common lordships.

The idealized narratives about the Swiss Confederation, which from the 15th century onwards also called itself Liga vetus et magna Alamaniae superioris in Latin, ‹Old Big Federation of Upper German Lands› , formed a central element in the formation of federal and later Swiss-national identity since the 16th century.

story

founding

A document from the year 1291 , sealed by the three forest sites Uri , Schwyz and Unterwalden (later also called Federal Letter), acquired central importance as the possible founding date of an «Old Confederation» , as well as the Bund von Brunnen 1315 and the alliance between Lucerne and the three forest sites by 1332.

As an inconsistent political-military network of alliances between the participating "places", headed by the up-and-coming urban patriciate or the landed aristocracy, the Confederation was initially directed against the claims of the Habsburgs , which had established themselves in the Central Plateau and Central Switzerland since the acquisition of the city of Lucerne in 1291 had. In addition to the first attempts at territorial expansion, the alliances served to secure the peace and justice, and to preserve the privileges and freedoms acquired by various Roman-German emperors (the myth of Wilhelm Tell ). In 1309 King Heinrich VII confirmed the imperial immediacy of Uri and Schwyz and now also included Unterwalden; the three forest sites were placed under a royal governor. In more recent research, the privilege of 1309 is viewed as an important step towards the formation of an alliance later, but the importance of the Federal Letter is sometimes viewed as overestimated.

The wars against Habsburg Austria in the 14th and 15th centuries ( Battle of Morgarten in 1315, Battle of Sempach in 1386, the myth of Arnold Winkelried , conquest of Aargau and Thurgau in 1415, battle against Habsburg and Zurich in the Old Zurich War ) followed in the 15th In the 16th and 16th centuries a military expansion to the south into Ticino and through pay alliances further into Lombardy. Mercenaries and the towns from the Confederation fought successfully (under the Visconti and Sforza ) until the victory against France in Novara in 1513 - only two years later, in 1515, the tragedy of the Battle of Marignano followed , where mercenaries from the Confederation joined the troops faced individual places after those places had withdrawn which agreed to the various deals and pay alliances with the French, so there could be no question of a unit.

Old Zurich War and Stans Declaration

Even before the Reformation , Zurich and Schwyz fought for access to the Ricken Pass, which was of central importance for the supply of grain to the forest, for example in the Old Zurich War (1436–1450), which put the confederation's loose network of alliances to the test. Another conflict arose after the successful Burgundian Wars under the leadership of the city of Bern when it came to the admission of the cities of Solothurn and Freiburg to the Swiss Confederation: In the so-called " Stanser Verkommnis " (1481), according to legend, only the council of the hermit (and later National saint) Brother Klaus the community before the collapse. According to more recent research results, this was the first constitutional treaty that included all the places involved. The Swiss Confederation owes this step towards a binding treaty the successful resistance against the attempt to reintegrate the federal territory into the empire by the Habsburg Maximilian I ( Swabian War 1499) and ultimately the subsequent complete separation from the Holy Roman Empire .

reformation

After the beginning of the Reformation, the cantons split into a Reformed and a Catholic camp: while the large cities of Zurich, Bern and Basel joined the Reformation, the Waldstätte with Lucerne and Zug formed their own denominational and political bloc as “Five Places” and left in addition, a defensive alliance with the Reich; on the other hand, Zurich concluded a temporary " castle law " with Reformed cities in southern Germany that were outside the Confederation. There were repeated military conflicts between the two denominational groups, for example in the First (1529) and Second Kappel War (1531) and in the First 1656 and Second Villmerger War in 1712 ( Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Switzerland ; 1519–1712). The application for membership of the reformed Free Imperial City of Strasbourg was also delayed by the Catholic estates after its entry in 1584 in order not to fall into the minority.

In the formation of the «Old Confederation» a distinction is made between different periods, which are based on the number of places involved (estates, cantons).

- 1291–1332 III Places : Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden

- 1353–1481 VIII Locations : Lucerne, Glarus, Zurich, Zug, Bern

- 1481–1501 X Places : Freiburg, Solothurn

- 1501–1513 XII Places : Basel, Schaffhausen

- 1513–1798 XIII Places : Appenzell

In 1648, in the Peace of Westphalia , the Confederation also became de jure independent of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , after having been de facto since the Swabian Wars ( Battle of Dornach ) in 1499.

«Constitution» of the Old Confederation

The constitutional registration of the old Confederation causes some difficulties. According to medieval understanding, it was an alliance with the primary purpose of maintaining peace in the country and of defending the territory of the members against foreign legal claims and military attacks. In addition, until 1798 there was no international treaty valid for all members from which the establishment of a federal state or a federation of states could be derived. Until 1526, the ceremony of conjuring up the old covenants and treaties remained the framework by which all members of the covenant were held together. Then even this fell away because of the denominational separation. Even among the early constitutional lawyers of the 16th century, it was therefore controversial whether the Confederation was a confederation or an alliance or an alliance.

The core of the difficulty is the question of the sovereignty of the federal locations and those who are related to them. A transfer of sovereignty from the members to a confederation of states can only take place if the members are sovereign beforehand. The federal locations or cantons and allies were de iure sovereign to the outside only from 1648, when they were "released" from the Roman Empire by the Peace of Westphalia . Before that, the old confederation was an alliance of de facto against outside sovereign imperial estates , which still derived their rights of rule and freedom as well as privileges from the empire. Even for the period after 1648, the complete sovereignty of the Old Confederation is externally controversial, as there was a strong dependence on France, which was anchored in various pay alliances. Since, after the internal division caused by the Reformation, these pay alliances were temporarily the only document signed by almost all places, the alliance with France can almost be seen as part of the constitution of the Old Confederation. After the alliance expired in 1723, the new soldiers' alliance and the military alliance of the Thirteen Old Places as well as the Prince Abbey and City of St.Gallen, Wallis, Mulhouse and Biel with France formed the last jointly signed treaty of the Old Confederation. Based on the internal organization, the old places and allies were to be addressed as a confederation of states at the latest from 1648, despite the restrictions mentioned above. According to Peyer, in a European comparison it was between the Netherlands on the one hand and the Reich on the other in terms of degree of organization.

At the level of the confederation of states only the institution of the daily statute was established. Their main task was the administration of the common lordship, the negotiation of pay contracts and negotiations with foreign countries. After the Kappel Wars, the basis for these tasks was formed by four different so-called land peace treaties , in which the distribution of power between Catholic and Reformed places was regulated. Various approaches to develop the Swiss Confederation into a federal state such as B. the federal reform of 1655 , failed in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Reversal of the class order

At the end of the Middle Ages, several written statements show that the Confederates were convinced that they were a people chosen by God. The reversal of the “Christian status ” by the Swiss (e.g. in the battle of Sempach ), where Duke Leopold III, appointed by the Holy Roman Empire . "On his own, for his own, by his own people", strengthened their faith even more: Since the nobility neglected their duties to the simple peasants, the old order was no longer willed by God: Divine Providence gave victory to the Confederates Victory and made them the true nobles. In doing so, they opposed the Habsburg anti-federal propaganda, which in turn accused the Confederates of godlessness and the overthrow of the divine order.

A treatise on the other side accused the Confederates of the following erroneous self-understanding: "We are that chosen people, prefigured by the people of Israel, whom Almighty God defended against kings and princes because they obeyed his laws and his justice." Envoys replied z. B. self-confident in diplomatic negotiations with Charles the Bold : "If the Prince of Austria were then in his umbrella, the laudable confederates would be in God's umbrella." In addition, the veneration of the Passion (Christ) came astonishingly early in Switzerland, and "Praying with the outstretched arms" had become a common publicly celebrated prayer gesture among the Swiss at the end of the Middle Ages, especially at the beginning of a battle!

End of the Old Confederation

The French Revolution and the termination of the pay contracts with the Confederation after the storming of the Tuileries resulted in an alienation from France, which was fueled politically by the agitation of various groups of emigrants in France and the Confederation. Nevertheless, the Old Confederation was militarily neutral towards France during the First Coalition War and even tolerated the partial occupation of the Three Leagues and the annexation of the northern part of the Principality of Basel by France in 1792.

After the end of the First Coalition War, the Habsburg Monarchy left Switzerland, with the exception of Graubünden , to the French sphere of influence. In view of the immediate threat to federal territory, the federal envoys met at the invitation of the suburb of Zurich on December 26, 1797 in Aarau for an extraordinary meeting . It broke up without any concrete military decision. The beginning of the Helvetic Revolution on January 17, 1798 in Liestal shook the old Confederation. Between January 28, 1798 and May 28, 1799, war broke out with the Campagne d'Helvétie between the First French Republic and the Confederation. The French victory brought with it the military occupation of a large part of the territory of today's Switzerland by France and the establishment of the Helvetic Republic as a subsidiary republic . The so-called French invasion traditionally ended the era of the Ancien Régime or the Old Confederation in Swiss historiography .

Structure of the Old Confederation

Thirteen sovereign cantons

The order corresponds to the traditional counting. The year of entry in brackets.

VIII places

-

City of Zurich (1351)

City of Zurich (1351) -

City of Bern (1353)

City of Bern (1353) -

City of Lucerne (1332)

City of Lucerne (1332) -

Country of Uri (1291)

Country of Uri (1291) -

State of Schwyz (1291)

State of Schwyz (1291) -

Land Unterwalden ( Ob- and Nidwalden ) (1291)

Land Unterwalden ( Ob- and Nidwalden ) (1291) -

State of Glarus (1352/86)

State of Glarus (1352/86) -

City and Country Zug (1352)

City and Country Zug (1352)

X places

XII places

-

City of Basel (1501)

City of Basel (1501) -

City of Schaffhausen (1501), a locality since 1454

City of Schaffhausen (1501), a locality since 1454

XIII places

-

Land of Appenzell (1513), a locality since 1411

Land of Appenzell (1513), a locality since 1411

The 13 sovereign estates (cantons) formed the actual Confederation as full members. A distinction must be made between the country locations and the city locations . In the republican towns, the rural community formed the supreme sovereign as an assembly of all male rural residents with civil rights . The day-to-day business and the government were taken care of by the district administrator, representing the municipalities and parts of the country, as well as the district administrator, who formed the state government with some high-ranking officials (heads). In the towns, the citizenship of the namesake towns was politically decisive. According to the politically determining stratum of the urban bourgeoisie, one can further distinguish between guild towns (Zurich, Basel, Schaffhausen) and patricians (Bern, Solothurn, Freiburg, Lucerne). In the guild towns, the sovereign was the large council and the minor council, which consisted of the guilds' boards. The "ruling class" in a guild town consisted of merchants, craftsmen, entrepreneurs (publishers), landowners, court lords and families of officers from foreign services . In the patriciate, the city councils were firmly in the hands of a hereditary and socially isolated upper class made up of rural and military nobility. The city of Bern, the largest city republic north of the Alps, was often compared with Venice in terms of its government structure. In the provincial as well as in the cities, the newcomers without civil rights, the so-called rear - seaters , as well as the residents of the subject areas, had no political rights .

There was no federal treaty signed by all Thirteen Locations, but only a series of alliances that individual cantons had concluded with each other or among themselves. Contracts signed by all members, such as the Pfaffenbrief (1370), the Sempacherbrief (1393) and the Stans Declaration (1481) , acted as brackets . The joint treaties were regularly invoked by all places in a ceremony until 1526. The further development of the federal structure was prevented by the split in the Old Confederation through the Reformation. The cities of Zurich, Bern, Basel and Schaffhausen as well as parts of the provincial towns of Appenzell and Glarus changed over to the Reformed faith in the 16th century, while the cities of Lucerne, Freiburg and Solothurn with the provincial towns of Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and Zug remained in the old faith.

The Confederation, which is divided into denominational groups, has been plagued by civil wars for the supremacy of a denominational group ( Kappelerkriege 1529/1531, Villmergerkriege 1656/1712). Until 1712, the Catholic cantons organized in the Golden League were able to maintain a certain supremacy. Since the final separation of the Confederation as a whole from the Holy Roman Empire in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the individual cantons were considered to be sovereign republics. Since then, the old Confederation has been referred to by contemporaries as the Corpus Helveticum and, from today's perspective, can be described as a loose confederation of states. After the Kappel Wars, the First Land Peace signed by the Thirteen Places became a kind of constitution for the Confederation. By 1712, three more such rural peace treaties were signed, in which the common interests of the cantons were regulated, in particular the modalities of the administration of the common lordships and religious questions.

The only central institution of the Old Confederation was the Tagsatzung , which met in different places, most often in Baden and Frauenfeld . The assembly of delegates from the cantons had only very limited legislative and executive powers and was very cumbersome because the delegates were bound by the instructions of their cantons. Since the 15th century, Zurich, as a suburb, was entitled to chair the assembly. The professional votes of the half-cantons were counted as one vote in the daily statute. The annual accounting meeting in Baden, which takes place every July, mainly served the administration of the common lordships. If necessary, extraordinary assemblies of all places or denominational blocks were convened.

Facing Places (Allies)

After the year of the alliance, the alliance-concluding federal locations.

Closer ones

-

Prince Abbey of St. Gallen (1451); Zurich, Lucerne, Glarus and Schwyz

Prince Abbey of St. Gallen (1451); Zurich, Lucerne, Glarus and Schwyz -

City of Biel (1353); Bern, Freiburg, Solothurn, nominally under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel

City of Biel (1353); Bern, Freiburg, Solothurn, nominally under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel

-

City of St. Gallen (1454); Zurich, Bern, Lucerne, Schwyz, Zug, Glarus

City of St. Gallen (1454); Zurich, Bern, Lucerne, Schwyz, Zug, Glarus

Eternal allies

-

Republic of Valais (1416/17); Lucerne, Uri, Unterwalden; 1475 Bern; 1529 Schwyz, Zug, Freiburg; 1533 Solothurn

Republic of Valais (1416/17); Lucerne, Uri, Unterwalden; 1475 Bern; 1529 Schwyz, Zug, Freiburg; 1533 Solothurn -

Free State of the Three Leagues (1497/99); Zurich, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus; 1600 Valais; 1602 Bern; after 1618 actually only Bern and Zurich

Free State of the Three Leagues (1497/99); Zurich, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus; 1600 Valais; 1602 Bern; after 1618 actually only Bern and Zurich

Evangelical friends

-

City of Mulhouse (1515/86); XII places; 1586 only Zurich, Bern, Glarus, Schaffhausen, Basel; 1777 (XIII places)

City of Mulhouse (1515/86); XII places; 1586 only Zurich, Bern, Glarus, Schaffhausen, Basel; 1777 (XIII places) -

City of Geneva (1519/36); Bern, Freiburg; 1558 only Bern; 1584 Zurich, Bern

City of Geneva (1519/36); Bern, Freiburg; 1558 only Bern; 1584 Zurich, Bern

Remaining (temporary) allies

-

Principality / County of Neuchâtel (1406/1529); Bern, Solothurn; 1495 Freiburg; 1501 Lucerne

Principality / County of Neuchâtel (1406/1529); Bern, Solothurn; 1495 Freiburg; 1501 Lucerne -

Ursern valley (1317–1410); Uri; 1410 to Uri

Ursern valley (1317–1410); Uri; 1410 to Uri -

Weggis (1332-1380); Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Lucerne; 1480 in Lucerne

Weggis (1332-1380); Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Lucerne; 1480 in Lucerne -

City of Murten (1353–1475); Bern; 1475 common rule

City of Murten (1353–1475); Bern; 1475 common rule -

City of Payerne (1353-1536); Bern; 1536 in Bern

City of Payerne (1353-1536); Bern; 1536 in Bern -

Saanen and Château-d'Oex valleys (1403–1555) (Hochgreyerz, part of the county of Gruyères); Bern; 1555 in Bern

Saanen and Château-d'Oex valleys (1403–1555) (Hochgreyerz, part of the county of Gruyères); Bern; 1555 in Bern -

Bellenz (1407-1419); Uri, Obwalden; 1419–22 common rule

Bellenz (1407-1419); Uri, Obwalden; 1419–22 common rule -

County Sargans (1437-1483); Schwyz, Glarus; 1483 Common rule

County Sargans (1437-1483); Schwyz, Glarus; 1483 Common rule -

Freiherrschaft Sax-Forstegg (1458-1615); Zurich; 1615 in Zurich

Freiherrschaft Sax-Forstegg (1458-1615); Zurich; 1615 in Zurich -

City of Stein am Rhein (1459–1484) Zurich, Schaffhausen; 1484 in Zurich

City of Stein am Rhein (1459–1484) Zurich, Schaffhausen; 1484 in Zurich -

County of Gruyères (Niedergreyerz) (1475–1555); 1555 in Freiburg

County of Gruyères (Niedergreyerz) (1475–1555); 1555 in Freiburg -

Werdenberg county (1493–1517); Lucerne; 1517 in Glarus

Werdenberg county (1493–1517); Lucerne; 1517 in Glarus -

City of Rottweil (1463–1507 and 1519–1689); XIII places; after 1632 only Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Solothurn, Freiburg

City of Rottweil (1463–1507 and 1519–1689); XIII places; after 1632 only Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Solothurn, Freiburg -

Principality of Basel (1579–1735); Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Solothurn, Freiburg

Principality of Basel (1579–1735); Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Solothurn, Freiburg

The associated places were states, monarchs or regions that were allied with the Confederation or parts of it. The “close relatives” had definitely had a seat and vote in the federal assembly since 1667. The "Eternal Co-Allies", the Republic of Valais and the Free State of the Three Leagues, were also organized on a federal basis. The Republic of Valais consisted of seven tens in Upper Valais, each of which had its own parish and was only under a common district administrator and governor. As the original sovereign, the Prince-Bishop of Sitten had a kind of honorary presidium. The Free State of the Three Leagues was led out of the Federal Heads through the “Contribution”. The final decision, however, lay with the people's assemblies of the 55 high courts or with the Bundestag, the assembly of representatives of the high courts. Another group of relatives formed after the Reformation were the cities of Mulhouse and Geneva, which because of their Reformed faith were only associated with Reformed cantons. The group of those involved is very heterogeneous in terms of their forms of government and state structures (guild towns, patricians, landscapes, monarchies), and the alliances are of very different content. In the 17th and 18th centuries, because of the denominational and political contradictions in the Confederation, the relations between some members of the Confederation and the Confederation cooled down considerably, so that, for example, the Duchy of Basel can no longer be counted as a locality after 1735, and so can the Three Leagues in practice no longer maintained contact with the Diet.

Common gentlemen (condominiums)

The ruling places are shown next to the year of acquisition of power.

German-speaking common bailiwicks

-

Free offices (1415); VII Orte (excluding Bern), after 1712 Upper Freiamt: VIII Orte, Lower Freiamt: Zurich, Bern, Glarus

Free offices (1415); VII Orte (excluding Bern), after 1712 Upper Freiamt: VIII Orte, Lower Freiamt: Zurich, Bern, Glarus -

County of Baden (1415); VII Orte (without Uri), after 1443–1712 VIII Orte, then only Zurich, Bern, Glarus

County of Baden (1415); VII Orte (without Uri), after 1443–1712 VIII Orte, then only Zurich, Bern, Glarus -

County Sargans (1460/83); VII Orte (excluding Bern), after 1712 VIII Orte

County Sargans (1460/83); VII Orte (excluding Bern), after 1712 VIII Orte -

Landgraviate of Thurgau (1460); VII Orte (excluding Bern), after 1712 VIII Orte

Landgraviate of Thurgau (1460); VII Orte (excluding Bern), after 1712 VIII Orte -

Reign of the Rhine Valley (1490); VIII Orte (excluding Bern with Appenzell), after 1712 VIII Orte and Appenzell

Reign of the Rhine Valley (1490); VIII Orte (excluding Bern with Appenzell), after 1712 VIII Orte and Appenzell

Bailiwicks of the third half of a town

Common lords of Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden

-

Bollenz (Blenio) (1477-1480, 1495)

Bollenz (Blenio) (1477-1480, 1495) -

Reffier (Riviera) (1403-1422, 1495)

Reffier (Riviera) (1403-1422, 1495) -

Bellenz (Bellinzona) (1500)

Bellenz (Bellinzona) (1500)

Ennetbirgische Vogteien

Common dominions of the XII places (without Appenzell)

-

Maiental (Val Maggia) (1512)

Maiental (Val Maggia) (1512) -

Lauis (Lugano) (1512)

Lauis (Lugano) (1512) -

Luggarus (Locarno) (1512)

Luggarus (Locarno) (1512) -

Mendris (Mendrisio) (1512)

Mendris (Mendrisio) (1512) -

Val Travaglia (1512-1515)

Val Travaglia (1512-1515) -

Cuvio (1512-1515)

Cuvio (1512-1515) -

Ashenvale (1512-1515)

Ashenvale (1512-1515)

Two-part bailiffs

Common lords of Bern and Friborg

-

Grasburg / Schwarzenburg rule (1423)

Grasburg / Schwarzenburg rule (1423) -

Murten (1475)

Murten (1475) -

Grandson (1475);

Grandson (1475); -

Orbe and Echallens (1475);

Orbe and Echallens (1475);

Common lords of Schwyz and Glarus

-

County of Uznach (1437)

County of Uznach (1437) -

Lordship of Windegg / Gaster (1438)

Lordship of Windegg / Gaster (1438) -

Reign of Hohensax / Gams (1497)

Reign of Hohensax / Gams (1497)

Common rule of Bern and Zurich

-

Hurdles (1712)

Hurdles (1712)

Common rule with relatives

Common rule of Bern and the Prince-Bishop of Basel

-

Lordship of Tessenberg / Montagne de Diesse (1388)

Lordship of Tessenberg / Montagne de Diesse (1388)

Areas that were conquered jointly by several places and also administered jointly as bailiwicks were referred to as common lordships . The number and the combination of the ruling places varied greatly. The “German-speaking common bailiwicks” were in Aargau , Thurgau and what is now the canton of St. Gallen . The territories conquered in the course of the Milan wars in what is now the canton of Ticino were summarized under the designation " ennetbirgische Vogteien " . "Zweiörtige Vogteien" were areas that were ruled jointly by Bern and Freiburg or Schwyz and Glarus. After the Second Villmerger War in 1712, the Reformed cantons forced a new composition of the ruling places in the German-speaking common bailiwicks.

Patrons (protectorates)

In addition to the year of the establishment of the protectorate, the places of protection (protectors) are indicated.

-

Erguel : (1335–1797) Biel (military sovereignty). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel .

Erguel : (1335–1797) Biel (military sovereignty). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel . -

Republic of Gersau (1359–1798): Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden.

Republic of Gersau (1359–1798): Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden. -

Engelberg abbey: (1386–1798) Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden.

Engelberg abbey: (1386–1798) Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden. -

City of Neuenstadt / La Neuveville : (1388–1798) Bern (Burgrecht). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel .

City of Neuenstadt / La Neuveville : (1388–1798) Bern (Burgrecht). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel . -

Bellelay Abbey : (1414–1798) Bern (until 1528), Biel, Solothurn (Burgrecht). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel .

Bellelay Abbey : (1414–1798) Bern (until 1528), Biel, Solothurn (Burgrecht). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel . -

Muri Abbey (1415–1798): Zurich, Lucerne, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus, Uri (from 1549), Bern (from 1712).

Muri Abbey (1415–1798): Zurich, Lucerne, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus, Uri (from 1549), Bern (from 1712). -

Wettingen Abbey (1415–1798): Zurich, Lucerne, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus, Uri (from 1549), Bern (from 1712).

Wettingen Abbey (1415–1798): Zurich, Lucerne, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus, Uri (from 1549), Bern (from 1712). -

County of Toggenburg : (1436–1718) Schwyz, Glarus; (1436–1798) Zurich, Bern. At the same time, Toggenburg was subject to the Prince Abbey of St. Gallen.

County of Toggenburg : (1436–1718) Schwyz, Glarus; (1436–1798) Zurich, Bern. At the same time, Toggenburg was subject to the Prince Abbey of St. Gallen. -

Prince Abbey of St. Gallen : (1451 / 79–1798) Zurich, Lucerne, Schwyz, Glarus. At the same time, the prince abbey of St. Gallen was a dedicated place.

Prince Abbey of St. Gallen : (1451 / 79–1798) Zurich, Lucerne, Schwyz, Glarus. At the same time, the prince abbey of St. Gallen was a dedicated place. -

Pfäfers Abbey : (1460–1483) Zurich, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus; 1483 to the county of Sargans.

Pfäfers Abbey : (1460–1483) Zurich, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus; 1483 to the county of Sargans. -

Rapperswil rule (1464–1712): Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Glarus; (1712–1798) Zurich, Bern, and the reformed part of Glarus.

Rapperswil rule (1464–1712): Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Glarus; (1712–1798) Zurich, Bern, and the reformed part of Glarus. -

Propstei Moutier-Grandval : (1486–1798) Bern (Burgrecht). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel and was part of the Reich until 1797.

Propstei Moutier-Grandval : (1486–1798) Bern (Burgrecht). Was under the sovereignty of the Principality of Basel and was part of the Reich until 1797. -

Reign of Haldenstein (1541–1798): Zurich, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus.

Reign of Haldenstein (1541–1798): Zurich, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus.

The patrons were actually protectorates , which, however, did not always lead to a relationship of subjects between the patrons and the patrons. While the prince abbot of St. Gallen, for example, was only really dependent on cooperation with the umbrella locations when he got into conflicts with his subjects or with individual federal locations, and also remained fairly independent in his foreign policy, the Einsiedeln Abbey or the Rapperswil rulership was in fact in a similar position to the common rulers and could no longer pursue an independent foreign policy. For Toggenburg or the parts of the Principality of Basel that were protected by Bern, the patrons were more likely to represent guarantees of their “freedoms” or traditional privileges vis-à-vis the princely rule of their feudal lords both sides firmly, usually a right to protection from external enemies, institutionalized arbitration in internal conflicts, an obligation to military immigration, etc.

Individual local subjects of country locations and relatives

Uri

-

Livinen (Leventina) (1403, 1439)

Livinen (Leventina) (1403, 1439) -

Ursern (1440)

Ursern (1440)

Schwyz

-

Küssnacht (1402)

Küssnacht (1402) -

Prince Abbey of Einsiedeln (1397/1424)

Prince Abbey of Einsiedeln (1397/1424) -

March (1405/36)

March (1405/36) -

Courtyards (1440)

Courtyards (1440)

Glarus

-

Werdenberg (1485/1517); 1485 to Lucerne; 1517 in Glarus

Werdenberg (1485/1517); 1485 to Lucerne; 1517 in Glarus

Republic of Valais

-

St-Maurice (1475/77); VII Zehenden

St-Maurice (1475/77); VII Zehenden -

Monthey (1536); VII Zehenden

Monthey (1536); VII Zehenden -

Lötschental (15th century); V upper toe

Lötschental (15th century); V upper toe -

Evian (1536-1569); VII Zehenden

Evian (1536-1569); VII Zehenden

Free State of the Three Leagues

-

Worms (Bormio) (1512)

Worms (Bormio) (1512) -

Cleven (Chiavenna) (1512)

Cleven (Chiavenna) (1512) -

Valtellina (1512)

Valtellina (1512) -

Three Pleves (1512-1526)

Three Pleves (1512-1526) -

Maienfeld ( Bündner Herrschaft ) (1509–1790); at the same time a member of the Ten Court Association

Maienfeld ( Bündner Herrschaft ) (1509–1790); at the same time a member of the Ten Court Association

In addition to the common (= jointly administered) rulers and the subject areas of individual places, the territory of the urban places consisted of subject land except for the actual urban area. Whether or not someone belonged to the ruling class in the city depended on family affiliation. However, the rights and privileges of individual areas could vary significantly. For example, the municipal cities of Winterthur and Stein am Rhein were subordinate to the city of Zurich, but also had a small subject area and their own class of ruling city citizens.

literature

- Historical Association of the Five Places (Ed.): Central Switzerland and the early Confederation. Anniversary publication 700 years of the Swiss Confederation. 2 volumes. Olten 1990.

- Adolf Gasser , Ernst Keller: The territorial development of the Swiss Confederation 1291–1797. Sauerländer, Aarau 1932.

- Jean-François Aubert: Petite histoire constitutionnelle de la Suisse (= Monographs on Swiss History 9, ZDB -ID 1196141-7 ). Francke, Bern 1974.

- Ulrich Im Hof : Ancien Régime. In: Handbook of Swiss History. Volume 2. Report House, Zurich 1977, ISBN 3-85572-021-5 , pp. 673–784.

- Hans Conrad Peyer : Constitutional history of old Switzerland. Schulthess et al., Zurich 1978, ISBN 3-7255-1880-7 .

- Werner Meyer : Millet porridge and halberd. On the trail of medieval life in Switzerland. Walter, Olten / Freiburg (Breisgau) 1985, ISBN 3-530-56707-8 .

- Thomas Maissen : A "Helvetian Alpine Folk". The formulation of a national self-image in Swiss historiography of the 16th century. In: Zeszyty naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellonskiego Prace Historyczne. 1994 ( University of Heidelberg online )

- Bernhard Stettler: The Confederation in the 15th Century: The Search for a Common Denominator. Markus Widmer-Dean, Menziken 2004, ISBN 3-9522927-0-2 .

- Guy P. Marchal : Swiss history of use. Historical images, myth-making and national identity. Schwabe, Basel 2006, ISBN 3-7965-2242-4 .

- Roger Sablonier : Founding time without confederates. Politics and society in Central Switzerland around 1300. here + now, Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-03919-085-0 .

- Thomas Maissen : History of Switzerland. here + now, Baden 2010, ISBN 978-3-03919-174-1 .

- Andreas Würgler: The Swiss Diet. Politics, communication and symbolism of a representative institution in the European context 1470–1798. Publishers Bibliotheca Academica, Epfendorf 2014.

Web links

- The Old Confederation 1291–1515 on the Swiss History website by Markus Jud

- Andreas Würgler: Confederation. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Remarks

- ↑ a b c Norbert Domeisen: Swiss constitutional history, philosophy of history and ideology. Bern 1978, p. 27 ff. ( Full text web archive ).

- ^ Andreas Würgler: Confederation. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Guy P. Marchal: Swiss history of use: historical images, myth formation and national identity. Schwabe, Basel 2006, ISBN 978-3-7965-2242-0 .

- ^ Josef Wiget: Waldstätte. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Roger Sablonier: Founding time without confederates. Politics and society in Central Switzerland around 1300. Baden 2008, p. 116 ff.

- ↑ Roger Sablonier: Founding time without confederates. Politics and society in Central Switzerland around 1300. Baden 2008, p. 163 ff.

- ↑ Bernhard Stettler: The Confederation in the 15th Century: The Search for a Common Denominator. Markus Widmer-Dean, Menziken 2004, ISBN 3-9522927-0-2 .

- ↑ Thomas Maissen: History of Switzerland. here + now, Baden 2010, ISBN 978-3-03919-174-1 .

- ↑ Why Strasbourg does not belong to Switzerland , NZZ, June 20, 2018, p. 18, title of the print edition

- ↑ Not until January 25, 1798, shortly before the French invasion, did the Aarau parliament once again conjure up the old leagues in the vain hope of impressing France and averting an invasion.

- ↑ Peter Stadler: The Age of the Counter Reformation. In: Handbuch der Schweizer Geschichte 1. pp. 571–672, p. 642. Hans Conrad Peyer, Verfassungsgeschichte. P. 5.

- ^ Hans Conrad Peyer: Constitutional history. Pp. 143-147.

- ↑ Guy P. Marchal: Central Switzerland and early Confederation: The old Confederates through the ages. «God had chosen the ignoble»

- ↑ Andreas Heusler: Basler Bundesbrief from 1501. Retrieved on May 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Ulrich Im Hof: Ancien Régime. In: Handbuch der Schweizer Geschichte 2. pp. 673–784, 675 f.

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Im Hof: Ancien Régime. P. 732.

- ^ Andreas Würgler : Patrons. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . October 18, 2012 , accessed June 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Also referred to in the literature as Zugewandter Ort, for example by Stadler in the Historical Lexicon of Switzerland, see Alois Stadler: Rapperswil (SG). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . September 22, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2019 .