Charles the Bold

Charles I the Bold - French Charles I er le Téméraire or le Hardi , Dutch Karel de Stoute , English Charles the Bold - (born November 10, 1433 in the Ducal Palace , Dijon ; † January 5, 1477 near Nancy ) was a member of the dynasty Valois-Burgundy , a sideline of the French royal family Valois . His parents were Philip III. the good and Isabella of Portugal. Charles the Bold was Duke of Burgundy and the Burgundian Netherlands from June 15, 1467 to January 5, 1477 .

In the judgment of posterity , Charles the Bold was often seen as the last representative of the feudal spirit. He had great abilities, strict morals, was extremely cultured, and was able to speak several languages. Karl is, as the historian Christoph Driessen writes, "the prime example of a ruler who, in a very short time, through excessive ambition for a great empire and, moreover, for his head and shoulders".

Life

Youth and the way to power

Charles the Bold was born in Dijon as the son of Philip III. the good, Duke of Burgundy from a sideline of the French royal family of Valois, and Isabella of Portugal. During his father's lifetime he was named Count of Charolais . Twenty days after his birth he was made Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece . He was brought up under the supervision of Mr. d'Auxy and is said to have shown great devotion to study, but also to exercises in the craft of war. Karl grew up at his father's court, which was one of the most glamorous of the era and a center for art, trade and culture. For many years his father's policy was shaped by the endeavor, on the one hand, to unite his numerous domains into a unified state structure and to administer it according to the most modern aspects of the time and, on the other hand, to break away from the feudal sovereignty of the French king or the Roman-German emperor . In order to achieve this, Philip did not shy away from the alliance with England , France's archenemy (in the context of the Hundred Years War ). The resulting armed conflict between France and Burgundy did not end until 1435 with the Treaty of Arras . Burgundy received some additional territories and became a de facto independent state; Philip's son was to marry a French princess.

According to the Treaty of Arras, Charles was married in 1440 at the age of six to Katharina von Valois , the twelve-year-old daughter of the French King Charles VII . Katharina von Valois died in 1446 at the age of 18. The marriage remained childless. In 1454, Charles Margaret of York , daughter of the Duke of York, wanted to marry. However, his father chose his niece Isabelle de Bourbon , who was also the cousin of the King of France, as his wife. Their daughter Maria of Burgundy was the only surviving child of Charles and sole heir to all of his possessions.

Karl met the Dauphin and later French King Louis XI. know when he lived as a refugee at the Burgundian court between 1456 and 1461 after falling out with his father. When Ludwig rose to king, however, he turned against his former ally and, for example, triggered the pledge of the Somme cities , which his father had given to Philip the Good in the Treaty of Arras. The French noble houses then allied against the king in 1465 in the "League of Public Welfare" ( Ligue du Bien public ) , headed by Charles von Berry and Charles the Bold. After the undecided battle of Montlhéry , Ludwig had to make considerable concessions to the nobility. In the Treaty of Conflans , Charles got the cities back on the Somme.

Charles's second wife, Isabella von Bourbon, died during the negotiations between Ludwig and Karl. Negotiations about a marriage between Karl and Anne de Beaujeu , the daughter of Louis XI., Remained fruitless.

On April 12, 1465, Philip the Good handed over all government affairs to Karl, who from then on tried to continue his father's policy.

On July 3, 1468, Charles the Bold married nineteen-year-old Margaret of York . This wedding was described in detail by the court official and historian Olivier de la Marche in his memoirs. Among other things, a 10 meter high tower ("Tower of Gorkum") was erected as a centerpiece. Mechanical boars blew trumpets from its sound holes and mechanical goats sang motets . This marriage remained childless, but a friendly relationship developed between Margaret and her stepdaughter Maria of Burgundy .

Revolts and renewed struggle with France

The peace between Karl and Ludwig XI. only lasted for a short time. On August 25, 1466, Karl took Dinant , which he looted and burned. At the same time he successfully negotiated with Liège . After the death of his father on June 15, 1467, the hostilities with the citizens of Liège flared up again, which ended with a victory for Charles at Sint-Truiden . Charles became Vogt of the Principality of Liège, whose possessions ran through what is now Belgium from north to south.

Alarmed by these early successes of the Duke of Burgundy and for fear of having to fulfill some open points of the Treaty of Conflans, Ludwig requested a meeting with Charles in October 1468 and passed into his hands at Péronne . In the course of the negotiations, Karl was informed of another Liège revolt, which Ludwig had secretly instigated. After four days of deliberations on how to deal with his opponent, who had so clumsily put himself into his hands, Karl decided to negotiate with Ludwig and got Ludwig to support him in suppressing the revolt in Liege.

After the one-year truce that followed the Treaty of Péronne , Louis XI sued. Charles of Treason, summoned him to the Parlement of Paris and in 1471 took some cities on the Somme. The Duke responded with the invasion of France by a large army, took possession of Nesle and caused a bloodbath among the inhabitants. After a failed attack on Beauvais , Karl moved with his troops as far as Rouen , where he paused. Charles now concluded an alliance with Edward IV of England to conquer France, while Ludwig negotiated with the German Emperor, the Habsburgs and the Confederation in order to employ Karl on the eastern border.

Karl suggested the new offer from Louis XI. decided to take his daughter Anne as wife. After the death of his father, no longer bound by the Treaty of Arras, Karl had Margareta brought from York to Bruges and married her there in a splendid ceremony in the summer of 1468. On this occasion, Karl was accepted into the Order of the Garter. The couple remained childless.

Domestic reforms

Karl carried on the exuberant luxury and splendor of his father at his court. At the meeting with the emperor in Trier, according to his accounting chamber, Karl spent the enormous sum of 38,819 Flemish pounds just on the clothing of his courtiers. The famous tapestries that the Duke had made on every occasion were also legendary. Some of these tapestries, which were very luxurious for the time, have been preserved from Grandson's Burgundy loot.

In addition, Karl directed his efforts into building up his military and political power. Since the beginning of his rule he was busy with the reorganization of the army and administration of his lands. He maintained the principles of feudal recruitment, but established a system of strict discipline among his troops, which he reinforced with mercenaries , particularly from England and Italy . He also developed his artillery further.

Under his leadership, the administration of the Burgundian territories was largely centralized in what is now the Netherlands and Belgium . The two chambers of accounts (Cour des comptes) of Lille and Brussels (the Chamber of Accounts The Hague had merged with that of Brussels in 1463) were dissolved and centralized in a newly established Chamber of Accounts in Mechelen . In the same city, Karl also founded a parliament that was responsible for the Burgundian areas in the north. In addition, there were still the parliaments of Beaune , St. Laurent-lès-Chalon and Dole , which were responsible for the Duchy of Burgundy, the part of the Duchy located in the empire and the Palatinate County of Burgundy . The re-establishment of Mechelen was necessary, among other things, because the Treaty of Péronne in 1468 removed the jurisdiction of the Parliament of Paris for the Burgundian countries .

Karl occupied himself extensively with military affairs. According to contemporary reports, hardly a day went by without spending an hour or two writing down and devising his prescriptions. Every year he had his officers distributed army orders ( Ordonnanzen ), with rigorous instructions regarding organization, discipline, manners and procedures. He tried to curtail the traditionally strong participation rights of the nobility and bourgeoisie in the later Netherlands and Belgium as much as possible.

From 1471, when Charles was again at war with Louis XI after the Treaty of Péronne. found, his endeavor was to create an army that was always ready to fight, consisting mainly of mercenaries. He set up orderly companies, with the nobles of his court with the orderly from April 19, 1472 as company commanders (French: dizainiers - here: Zehner (leaders) = leaders of 10 units), to whom a unit of 10 lances (approx. 70-90 Fighter) was subordinated to service in the army. The rest of his court was also increasingly militarized and in the court rules of 1474 the court finally appears as a kind of army in which every office also forms a solid military unit.

Increase in power

In 1469, Sigismund , Archduke of Austria , pledged the county of Pfirt , the bailiffs of Upper Alsace and the Breisgau in the Treaty of Saint-Omer , but reserved the right to later redeem the pledge. Karl should also help Sigismund in his fight against the Confederates . (→ Swiss Habsburg Wars )

Between 1472 and 1473, Karl was able to buy the successor in the Duchy of Geldern because he had supported the Geldrian Duke Arnold against the rebellion of his son. Not yet satisfied with the title of "Grand Duke of the West", he took up the project to establish an independent Kingdom of Burgundy. While its territories, which were in the Kingdom of France, were already separated from the feudal sovereignty of France by the treaties of 1468 and 1471, its eastern territories were still subject to the Holy Roman Empire .

Under the pretext of considering a Burgundian participation in a crusade against the Turks, he therefore met with Emperor Friedrich III on September 30, 1473 . in Trier. The main subject of the meeting was the negotiation of a marriage between Karl's only child, Maria, and the emperor's son, Maximilian . Karl demanded the royal crown in exchange for himself. He appeared in Trier in golden armor with a bodyguard of 250 men and an army of over 6,000 men, accompanied by some imperial princes from his sphere of influence. The emperor and his son had an even larger retinue, but displayed far less pomp. The voting votes of Mainz , Trier and Brandenburg were also represented in Trier . During the negotiations, some lavish banquets, receptions and tournament games took place. On November 4th, the two parties found a compromise: Although Karl renounced his coronation as Roman-German king , which would have made him the emperor's successor, he was to receive a new royal crown from Burgundy and Friesland. The electors , however, refused to consent to this trade. After Karl had been enfeoffed with the Duchy of Geldern, the royal coronation announced for November 18th and then on November 21st did not take place, and the emperor left Trier in a hurry on November 25th. It is unclear exactly why the negotiations failed. The role of the electors seems to have been decisive. Karl insisted on her consenting to his coronation, while the Kaiser was of the opinion that this decision was his own. The electors and the emperor's surroundings were also alienated by the luxury that Karl displayed, including the fact that he B. wore an ermine collar that was longer than that of the electors.

Downfall

The following year, Karl got caught up in a number of difficulties and struggles, e.g. B. the unsuccessful siege of Neuss , which should ultimately lead to his downfall. Last but not least, the intrigues and schemes of the French King Louis XI. decisive for the failure of Charlemagne. Karl fell out with Sigismund of Austria, to whom he did not want to return his possessions in Alsace and the county of Hauenstein for the agreed sum, with the Confederation , which ultimately supported the imperial cities in Alsace in their revolt against the tyranny of the Burgundian governor Peter von Hagenbach also with René of Lorraine , with whom he contested the succession of Lorraine , which separated the two main parts of Charles' lands, the county of Flanders and the Duchy of Burgundy.

All these opponents, incited and supported by Ludwig, did not need long to ally against their common enemy. Karl suffered a first defeat when he tried to support Ruprecht von der Pfalz , Archbishop of Cologne , in the Cologne collegiate feud . In this context, he besieged the city of Neuss from July 1474 to June 1475 for ten months, but was due to the arrival of the army of Emperor Friedrich III. forced to lift the siege and withdraw. In addition, the expedition of his brother-in-law Edward IV of England against Louis was stopped by the Treaty of Picquigny on August 29, 1475. Therefore, on November 17, 1475, Karl made peace with Emperor Friedrich III. and turned against the Duchy of Lorraine , where he was able to successfully take the capital Nancy after a siege.

However, the war with the Lower Association , which consisted of the Alsatian imperial cities , the diocese of Basel , Duke Sigismund of Austria and the Swiss Confederation , ultimately led to its end . A Burgundian army suffered its first defeat against the emerging military power of the Swiss Confederation on November 13, 1474 near Héricourt . This opened the series of battles known in Switzerland as the Burgundian Wars that led to the fall of Charles. Karl marched from Nancy against the Swiss Confederation in Vaud , where he united with allied nobles from the Duchy of Savoy . At Grandson he met federal troops for the first time, whom he hung and drowned after the siege of the fortress despite their surrender. On March 2, 1476, he was attacked by a federal army in front of Grandson , where he suffered a heavy defeat. He was able to flee with a handful of followers, but his artillery and the huge booty fell into the hands of the Confederates as "Burgundy booty".

Karl fled to Lausanne , where he and the ally Savoy raised a new army of 20,000 men to march again against the federal imperial city of Bern , which was the head of the anti-Burgundian coalition in the Confederation. On May 6, 1476, in Lausanne, he also confirmed the marriage agreement between his daughter Maria and Archduke Maximilian of Austria, but the marriage was not yet consummated for the time being because the planned wedding date of November 11th had not been completed. At the beginning of June Karl marched with his army against Bern and from June 9th besieged Murten , where he was attacked on June 22nd by an army of the Confederation and the Duke René of Lorraine . His technically superior army was surprised, similar to the one in Grandson, and was devastatingly defeated by the force of the federal infantry in the battle of Murten . The Duchess of Savoy was forced to conclude peace with the Swiss Confederation, and the Burgundian possessions in Vaud were lost.

Charles returned to Burgundy and in the autumn turned against Lorraine, which was in open revolt against the Burgundian occupation. Duke René secured federal support and began to recapture his duchy. On September 25, Karl set out from Gex with an army, for which a strength of less than 10,000 to a maximum of 15,000 men is given, in the direction of Lorraine, where René besieged the capital Nancy . A few days before Karl arrived in Lorraine, Nancy fell into the hands of the Lorraine people. Although winter was approaching and against the advice of his officers, Karl laid a siege ring around Nancy on October 22nd. In the middle of winter, on January 5th, 1477, the battle of Nancy broke out at the gates of the city , when Duke René, reinforced by influx from the Swiss Confederation, put Karl to fight. With 15,000 to 20,000 men, the federal-Lorraine army clearly outnumbered Charles's army, which had already been weakened by the siege, but despite the unfavorable balance of power, the Burgundian duke faced the battle, which ended in a catastrophic defeat for the Burgundians.

Charles the Bold died in this battle under unknown circumstances. Presumably his horse shied and threw off the already wounded duke. Lying on the ground, he finally received such a severe blow to the head that his skull was split open. His frozen corpse, severely disfigured by several wounds and almost naked due to looting, which had also been eaten by wolves or wild dogs, was found two days later near a pond. One of Karl's servants eventually identified the body from some scars and other physical features than that of the Duke of Burgundy. Charles's victorious enemies captured, among other things, his to Louis XI. The helmet he sent to him, his ring given to the Duke of Milan in 1478, his tunic that was hung on the Strasbourg Cathedral as a sign of victory, and his chain of medals with the Golden Fleece, which he sold to Milan. Duke René had Karl's body laid out like a trophy and then buried in his court church of St. Georges in Nancy. Two tablets add an anti-Burgundian note. Charles V , the great-grandson of Charles the Bold, finally arranged for the mortal remains of the last Duke of Burgundy to be transferred to the Church of Our Lady in Bruges , where they are still to this day in a very elaborately designed tomb commensurate with their rank.

Battle for the legacy of Charles the Bold

The Burgundian inheritance of Charles the Bold fell to his 19-year-old daughter Maria as the only heir, as he had left no male heirs. Margaret of York, the widow of Charles, led marriage negotiations with the French king and the Roman-German emperor as the protector of Mary. The eldest sons of both rulers were still unmarried at this time and Maria, with her huge inheritance, represented the best match in Europe. The marriage between Archduke Maximilian of Austria and Maria of Burgundy was already agreed on May 6, 1476, but before the death of Charles has not yet been carried out. King Louis XI. von France worsened his negotiating situation drastically when, shortly after Charles's death, he occupied the parts of Charles's dominion bordering France. The Duchy of Burgundy, the Free County of Burgundy, Picardy, Ponthieu and Boulogne fell under the control of the French crown again. At this favorable moment, Emperor Friedrich brought the negotiations to a conclusion with the help of Margaret of York, who was hostile to Ludwig, so that the marriage could be concluded on April 21st. On August 19, 1477 Maximilian and Maria married in Ghent . In this way, after the death of his father, Maximilian was able to combine the inheritance of Charles with the power of the Habsburgs, making him the most powerful prince in Europe at that time. The Burgundian inheritance was one of the decisive steps in the rise of the House of Habsburg to world power.

Immediately after the marriage between Maximilian and Maria, a war broke out between Maximilian and Ludwig XI over the inheritance of Charles . Although they concluded a provisional armistice in September 1477, the war began again in 1478 when the Parliament of Paris declared Charles's French fiefs to be over. Maximilian was able to regain Flanders and Artois from the parts of his wife's inheritance claimed by Ludwig after his victory in the Battle of Guinegate in 1479. After Mary's early death on March 27, 1482 and an uprising in Ghent, Maximilian had to conclude the Peace of Arras with Ludwig in 1482 . The Duchy of Burgundy, the Free County of Burgundy, Artois, Picardy, Ponthieu, Boulogne, Vermandois and Mâcon fell to France. Maximilian kept Flanders and the other possessions of Charles in what is now Belgium and the Netherlands. Later Maximilian received the free county and Artois back in the Peace of Senlis in 1493. The county of Charolais remained in the possession of Maximilian or his underage son Philip , the actual heir of Mary, but was subject to the French feudal sovereignty.

The Burgundian heritage was cherished by Maximilian and his descendants. His children with Maria grew up in Ghent, Flanders, and his son Philip the Fair was named after Philip the Good. His son was baptized Karl in memory of the last Duke of Burgundy and, as Emperor Karl V, rose to become one of the most powerful rulers in the world at that time. With Philip and Karl, the Burgundian inheritance came to the Spanish line of the Habsburgs.

Result

The French King Louis XI. declared the Duchy of Burgundy, the Mâconnais , the Auxerrois and the Charolais to be defunct fiefdoms. The other provinces, in particular Franche-Comté (Free County ), Luxembourg, the Duchy of Brabant , the Artois, the County of Flanders and the County of Holland were assigned to the Burgundian Empire by the Roman-German Emperor Maximilian I.

Familiar

ancestors

|

Philip II the Bold (1342–1404) Duke of Burgundy |

|||||||||||||

|

Johann Ohnefurcht (1371–1419) Duke of Burgundy |

|||||||||||||

|

Margaret of Flanders (1350–1405) Countess of Flanders |

|||||||||||||

|

Philip III the Good (1396–1467) Duke of Burgundy |

|||||||||||||

|

Albrecht I (1336–1404) Duke of Lower Bavaria |

|||||||||||||

| Margaret of Bavaria (1363–1423) | |||||||||||||

| Margarete von Schlesien-Liegnitz (around 1342-1386) | |||||||||||||

|

Charles the Bold (1433–1477) Duke of Burgundy |

|||||||||||||

|

Peter I the Cruel / the Just (1320–1367) King of Portugal |

|||||||||||||

|

John I the Great (1357–1433) King of Portugal |

|||||||||||||

| Teresa Lourenço | |||||||||||||

| Isabella of Portugal (1397–1471) | |||||||||||||

|

John of Gaunt (1340-1399) Duke of Lancaster |

|||||||||||||

| Philippa of Lancaster (1360-1415) | |||||||||||||

| Blanche of Lancaster (1341-1369) | |||||||||||||

Wives and offspring

Karl married three times and had one child:

First marriage on May 19, 1440 in Blois Katharina von Valois (* 1428; † July 30, 1446), daughter of King Charles VII of France and Maria von Anjou . There were no descendants from this marriage.

In second marriage on October 30, 1454 in Lille Isabelle de Bourbon (* 1437; † September 25, 1465 in Antwerp ), daughter of Duke of Bourbon Charles I and Agnes of Burgundy . From this marriage there was a daughter:

- Mary of Burgundy (born February 13, 1457 in Brussels , † March 27, 1482 in Bruges ) ∞ (1477) Maximilian I , son of Friedrich III. , Holy Roman Emperor and his successor.

Third marriage on July 3, 1468 in Damme Margaret of York (born May 3, 1446 in Fotheringhay Castle ; † November 23, 1503 in Mechelen ), daughter of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York , and sister of King Edward IV. from England. There were no descendants from this marriage.

Charles the Bold in the judgment of posterity

Charles the Bold was often seen as the final representative of the feudal spirit, a man who possessed no ability other than blind valor. "Not even half of Europe would have been enough for him," said contemporary chronicler Philippe de Commynes of him. Often he was his opponent Ludwig XI. juxtaposed, which stood for modern politics. In truth, he had great abilities, strict morals, was extremely cultured, and spoke several languages. Although he cannot be acquitted of occasional hardship, he had the secret of winning the hearts of his subjects, who never denied him support even in difficult times. Since he left only his daughter Maria, the Habsburgs inherited the country complex of his house and expanded to the House of Austria and Burgundy , which was an essential cornerstone for their later world renown. Charles V was proud all his life to be descended from him.

In Swiss historiography, the contemporary saying is often quoted for the three battles of the Burgundian Wars that Charles the Bold "lost his hat in Grandson, his courage in Murten and his blood in Nancy". Instead of "the hat", which he is supposed to have really lost, there is also a more common version in which "the good" is only generally spoken of. In fact, after the Battle of Grandson, the city of Basel sold a ducal hat made of golden velvet, embroidered with pearls and precious stones, owned by Karl for 47,000 guilders, along with two other pieces of jewelry to Jakob Fugger .

In English he is also referred to as Charles the Rash (Karl the Hasty), which refers to his hasty urge to expand. Karl "is the prime example of a ruler who, in a very short time, with excessive ambition for a large empire and, moreover, for a head and neck". Due to its aggressive expansion and war policy, which resulted in a series of defeats, Burgundy lost its great power position and the rise of France to a European great power was made possible.

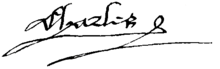

Portraits

All identified individual portraits of Charles as an adult go back to the portrait that is now in the Berlin Gemäldegalerie (cat. No. 545). The picture was taken around 1460 and shows Karl still as Count of Charolais. It is now generally attributed to Rogier van der Weyden , while for a long time it was thought to be either a workshop copy or a handwritten replica. It seems to have been the only official portrait of the state that was accepted by Karl and corresponds to the description of Karl by Georges Chastellain . The picture was later in the possession of his granddaughter Margaret of Austria in Mechelen Castle . It came to Berlin in 1821 with the collection of Edward Solly .

Rogier van der Weyden , around 1460

Peter Paul Rubens ,

around 1618Portrait with chain of the Order of the Golden Fleece , around 1470

coat of arms

The coat of arms of Charles the Bold is with the coat of arms of his father Philip III. identical. This introduced the fourth coat of arms in 1430.

His motto was: “Je lay emprins” (I dared). On heraldic representations, St. George but also St. Andreas , whom Karl claimed as patron saint for Burgundy but also for himself.

reception

Johann Jakob Bodmer wrote a tragedy for Charles of Burgundy . He based his play on the tragedy The Persians by the Greek writer Aeschylus and cast the characters from Burgundy. He replaces King Xerxes with Charles of Burgundy, the queen mother Atossa becomes Mary of Burgundy, the shadow of Darius is replaced by the spirit of Philip the Good. The messenger is embodied by Comte de Chaligny and instead of the choir of Persian princes, the Burgundian princes named Imbercurt, Hugonet and Ravestein appear.

title

-

1433-5. January 1477: Count of Charolais as Charles I.

1433-5. January 1477: Count of Charolais as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Burgundy as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Burgundy as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count von Artois as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count von Artois as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count Palatine of Burgundy as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count Palatine of Burgundy as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Flanders as Charles II.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Flanders as Charles II.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Margrave of Namur as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Margrave of Namur as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Brabant and Duke of Lothier (Lower Lorraine) as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Brabant and Duke of Lothier (Lower Lorraine) as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Limburg as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Limburg as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Hainaut as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Hainaut as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Holland and Friesland as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Holland and Friesland as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Zealand as Charles I.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Count of Zealand as Charles I.

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Auxerre

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Auxerre

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Mâcon

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Mâcon

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Boulogne

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Boulogne

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Ponthieu

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Ponthieu

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Vermandois

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477 Count of Vermandois

-

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Luxembourg as Charles II.

June 15, 1467-5. January 1477: Duke of Luxembourg as Charles II.

-

February 23, 1473-5. January 1477: Duke of Geldern as Charles I.

February 23, 1473-5. January 1477: Duke of Geldern as Charles I.

-

1477: Count of Eu

1477: Count of Eu

literature

- Wim Blockmans, Walter Prevenier: The Promised Lands. The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369-1530. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 1999.

- Christoph Driessen: History of Belgium. The divided nation. Regensburg 2018.

- Petra Ehm-Schnocks: Burgundy and the Empire. Late medieval foreign policy using the example of the government of Charles the Bold (1465–1477). (= Paris historical studies. 61). Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56683-0 ( perspectivia.net ).

- Holger Kruse: court, office and fees. The daily fee lists of the Burgundian court (1430–1467) and the first court of Charles the Bold (1456) . (= Paris historical studies. 44). Bouvier, Bonn 1996, ISBN 3-416-02623-3 ( perspectivia.net ).

- Hans-Joachim Lope: Charles the Bold as a literary figure. A thematic historical attempt with special consideration of the French-language literature of Belgium. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-631-40334-8 .

- Susan Marti et al. (Ed.): Karl der Kühne (1433–1477). Art, war and court culture. Publication for the exhibition from April 25 to August 24, 2008 in the Historical Museum in Bern. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 2008, ISBN 978-3-03823-413-5 . (also: Belser, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-7630-2513-8 ).

- Klaus Oschema, Rainer C. Schwinges (Ed.): Karl the Bold of Burgundy. Prince between the European nobility and the Swiss Confederation. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-03823-542-2 .

- Werner Paravicini : Charles the Bold. The end of the house of Burgundy. Frankfurt 1976, ISBN 3-7881-0094-X .

- Harm von Seggern: History of the Burgundian Netherlands. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2018.

- Klaus Schelle: Charles the Bold. The last Duke of Burgundy. Heyne, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-453-55097-8 .

- Richard Vaughan: Charles the Bold. The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy. Longman, London / New York 1973, ISBN 0-582-50251-9 . (Reprint with updated introduction: Boydell, Woodbridge 2002, ISBN 0-85115-918-4 ) (standard work on the history of Karl; review ).

Fiction

- Werner Bergengruen : Charles the Bold. Novel. Verlag die Arche, Zurich 1976, ISBN 3-7160-1067-7 .

- Heinrich Keller : Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. A patriotic drama in 5 acts. Orell & Füssli, Zurich 1813.

- Melchior Meyr : Charles the Bold. Historical tragedy. Kröner, Stuttgart 1862.

- Giovanni Pacini : Carlo di Borgogna. Opera in 3 acts. Libretto by Gaetano Rossi, Venice 1835.

- Thomas Vaucher : The Lion of Burgundy. A historical novel from the time of Charles the Bold. Stämpfli, Bern 2010.

Web links

- Literature about Charles the Bold in the catalog of the German National Library

- Karl der Kühne , exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, September 15, 2009 - January 10, 2010

- Hans Conrad Zander : 11/10/1433 - birthday of Charles the Bold WDR ZeitZeichen from November 10, 2013 (podcast)

- Berthold Seewald: Karl the Bold: These guys destroyed the best army of their time. In: Welt Online . Axel Springer SE , January 5, 2017, accessed on April 3, 2020 .

Remarks

- ↑ European Family Tables, Volume II, Plate 27.

- ↑ Christoph Driessen : History of Belgium. The divided nation. Regensburg 2018, p. 42.

- ↑ Horst Fuhrmann: Invitation to the Middle Ages . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-406-32052-X , p. 248 .

- ↑ Susan Marti et al. (Ed.): Karl der Kühne (1433–1477). 2008, p. 270.

- ↑ a b Christoph Driessen: History of Belgium. The divided nation. Regensburg 2018, p. 41 ff.

- ↑ Susan Marti et al. (Ed.): Karl der Kühne (1433–1477). 2008, p. 220.

- ↑ Susan Marti et al. (Ed.): Karl der Kühne (1433–1477). 2008, pp. 264 f. And 270.

- ^ E. von Rodt: The campaigns of Charles the Bold and his heirs. Hurter, Schaffhausen 1843, p. 412. - According to other representations, the Duke's corpse is said to have been recovered from the mud of this pond or found on its frozen surface.

- ↑ Joseph Calmette : The great dukes of Burgundy. Paris 1949. (German: Munich 1996, p. 342 f.)

- ↑ Norman Davies: Vanishing Empires. Theiss, Darmstadt 2015, p. 160.

- ↑ René Poupardin: Charles . [Duke of Burgundy] . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 5 : Calhoun - Chatelaine . London 1910, section penultimate paragraph , p. 932–933 (English, full text [ Wikisource ] - “ Charles the Bold has often been regarded as the last representative of the feudal spirit […] ”).

- ↑ mediatime.ch

- ↑ Susan Marti et al. (Ed.): Karl der Kühne (1433–1477). 2008, p. 277.

- ↑ Dirk De Vos: Rogier van der Weyden. Complete works. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 1999, pp. 308-310.

- ↑ Johann Jakob Bodmer : Karl von Burgund, a tragedy (after Aeschylus) (= Bernhard Seuffert, August Sauer [Hrsg.]: German literary monuments of the 18th and 19th centuries . Volume 9 ). Göschen, Stuttgart 1883 ( archive.org - published in new prints).

| predecessor | government office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Philip the good |

Duke of Burgundy 1467–1477 |

Maria |

| Philip the good |

Duke of Luxembourg 1467–1477 |

Maria |

| Philip the good |

Duke of Brabant and Lothier Duke of Limburg Margrave of Antwerp 1467–1477 |

Maria |

| Philip the good |

Count of Charolais 1433–1477 |

Maria |

| Philip the good |

Count of Flanders Count of Artois Count Palatine of Burgundy 1467–1477 |

Maria |

| Philip the good |

Count of Holland Count of Zeeland Count of Hainaut Count in Friesland 1467–1477 |

Maria |

| Arnold of Egmond |

Duke of Geldern, Count of Zutphen 1473–1477 |

Adolf von Egmond |

| Philip the good |

Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece 1467–1477 |

Maximilian I. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Charles the Bold |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Charles le Téméraire; le Hardi |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | last Duke of Burgundy |

| BIRTH DATE | November 10, 1433 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dijon , France |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 5, 1477 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | near Nancy , France |