George (saint)

Georg ( Latin Georgius , modern Greek Γεώργιος Geó̱rgios , Coptic Ⲅⲉⲟⲣⲅⲓⲟⲥ Georgios ) is a legendary Christian saint who, according to tradition, suffered martyrdom at the beginning of the persecution of Christians under Diocletian (284-305) . In the Orthodox churches he is venerated as a great martyr or arch martyr.

Historical information about his person is uncertain. Due to the possibly legendary character of the saint, George in the Roman Catholic Church was deleted from the Roman general calendar in 1969 , but reinserted in 1975.

Georg is one of the fourteen helpers in need . He is the patron saint of various countries, noble families, cities and knightly orders . The first name Georg (and its linguistic modifications) is one of the most popular first names in Europe.

Its symbol in heraldry is the George Cross . The red cross on a white background is featured in many coats of arms and flags. Attributes of the saints , which in addition to the St. George's Cross serve as a distinguishing mark of the saint, are the dragon and his depiction as a knight with a lance; sometimes George is shown with the palm frond of martyrdom.

Lore

Research into the sources of the legend of St. George reveals two wreaths, whereby the fight with the dragon was later added to the legend.

martyrdom

Eusebius reported in his church history (Hist. Eccl. 8,5) that an unnamed member of the upper class suffered martyrdom during the persecution of Christians under Diocletian in Nicomedia. This anonymus was subsequently identified with Georg.

Legends soon formed around the Asia Minor - Syrian area , reporting different dates and events, but containing the cruelty of his martyrdom and the overcoming of agony through faith as the core of the statement. George stood up for Christians persecuted under Diocletian and was tortured in order to induce him to renounce Christianity. Other elements in various sources and later additions concern, for example, the Christian ideal of poverty (George, depicted as a noble knight, gives away his land to the poor) and the destruction of idols in pagan temples . In Islam, George is known under the name Circis (or Cercis ) and is considered a prophet who endeavored to spread Christianity.

Dragon slayer

For the first time, St. George was associated with the concept of the dragon slayer at the time of the Crusades in the 12th century, especially through the Legenda aurea of Jacobus de Voragine . The dragon legend of George of Cappadocia is similar to various knight tales. Georg saves the virgin king's daughter from a beast, the dragon, by seriously injuring him, after which the maiden leads him tame into the city at the behest of the maiden. There George brings the king and the people to be baptized and then slays the dragon. The virgin is a sacrifice that the dragon demands of the population. After killing the dragon, the land is freed from evil. Different versions of the legend tell of different numbers of people being baptized. The theologian Hubertus Halbfas points out that Georg did not marry the king's daughter, since baptism is the goal of the legend. The dragon fight symbolizes the courageous fight against evil. According to this legend, St. George's Bay in Beirut got its name because the battle is said to have taken place here.

Late antique and early medieval travel reports on Palestine (6th - 7th centuries)

Soon after the saint's death , the center of oriental worship of George at the church of St. George was formed at his grave in Diospolis, the former Lydda and today's Lod (near Tel Aviv) . The archdeacon Theodosius , who came from North Africa, reported in his travelogue around 518/530 about Diospolis as the place of the martyrdom of St. George. An anonymous pilgrim from Piacenza in northern Italy mentions the same thing around 570. Only the pilgrimage story of the Gallic bishop Arculf , who traveled to Palestine around 680 , written by the Irish abbot Adamnanus († 704) from the island monastery of Iona , describes some oriental legends of George in more detail.

The Old High German Georgslied (9th-11th centuries)

In a manuscript of the first Old High German poet Otfrid von Weißenburg (* around 800, † after 870), an unknown scribe wrote the Old High German poem of the Georgslied at the turn of the 11th century or at the beginning of the 11th century . The verses tell of the conversion, judgment, martyrdom, and miracles of the saint. The text has only survived as a fragment.

Legends of the Late Middle Ages (13th-15th centuries)

The extensive veneration of St. George in the late Middle Ages corresponded to the legends of St. George that were widespread at the time and enjoyed great popularity among the faithful. Variations and adaptations of the life and suffering of the arch-martyr accompanied the whole of medieval history. Up until the 12th century, the dragon fight and the rescue of the princess were included in the legend of St. George, and the Legenda aurea of Jacobus de Voragine (approx. 1230–1298), an extensive collection of saints' lives, written around 1263/67 , reports in detail about the saint. A legend of St. George in verse is the Reinbots by Durne (around 1240), which is based on Wolframs von Eschenbach's " Willehalm " and " Parzival " († around / after 1220). The legend of St. George Reinbots was then transformed into the prose version "Book of Saint George" in the late Middle Ages.

More legends

In addition to the two main legends that formed the life story of George in the Middle Ages , there are others. For example, a legend tells of how a dragon was killed with the help of the relic of a finger of St. Georg was defeated.

The miracle of the young Paphlagonian (from the end of the 12th century) depicted on a cycle of wall paintings in the church in Pavnisi in Georgia is also shown on many icons. The subject has a historical background: In 917/918 the Byzantine army was defeated by the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon I at Anchialos and Katasirti . Legend has it that a young Papal agonist was captured and had to serve a Bulgarian nobleman in the Bulgarian capital, Preslav . One day, while he was bringing a vessel of warm water upstairs, a rider appeared and immediately took him back to his parents' house in Paphlagonia , just as his parents, who thought he was dead, were celebrating his funeral.

The capture of Jerusalem by the crusader army is important for the spread of the Georg cult in Christian countries . Legend has it that Georg appeared as a white knight and helped to take the city.

Relics

To St. Relics attributed to George are venerated in various places, for example in Toulouse , where he is said to be buried. The head is said to have been kept in Ferrara and has been venerated in Rome since the 8th century. The skullcap is venerated in the Georgskloster on the island of Reichenau. There are also several arm relics and smaller relics, including his flag.

Adoration

The veneration of St. Georg spread in the Middle East , Ethiopia and Egypt . In the Merovingian Franconian Empire , the veneration of George is attested as early as the 6th century, but George was most popular in the High Middle Ages . In the age of the crusades and chivalry , the cult of the oriental martyr spread noticeably. Georg became a battle helper during the conquest of Jerusalem by the Crusaders (July 15, 1099), as Miles christianus , as "Soldier of Christ", he became a figure of identification for knights and warriors, saints of orders of knights such as the Teutonic Order that emerged towards the end of the 12th century or the Templars . In the last centuries of the Middle Ages, Georg was the patron saint of cities, castles and rulers; he was counted among the 14 helpers in need. The oaths of the late medieval nobility (for example: societies with St. Jörgenschild ), as well as the veneration of George in the urban bourgeoisie, belong here under the sign of St. George .

German-speaking area (from 896)

George's Church on Reichenau

In the first centuries of the Middle Ages, the worship and relics of George reached Italy and the Merovingian Franconian Empire . The Archbishop of Mainz and Reichenau abbot Hatto I (891–913) received relics in Rome from Pope Formosus (891–896 ) in 896 , which have since been venerated in St. George's Church on the island of Reichenau. The cult of St. George introduced by the Archbishop of Mainz can be traced back to Reichenau in the centuries that followed.

It is controversial whether the Old High German Georgslied belongs to Lake Constance. Around the middle of the 11th century, the well-known historiographer Hermann von Reichenau (1013-1054) wrote a Historia sancti Georgii (“History of Saint George”), a Latin poem that has been lost. Finally, from a Reichenau manuscript of the 12th century come several Latin lines with neumes , the medieval musical notation, a song of praise to the saint of martyrs.

Archbishop Anno II of Cologne (11th century)

The person of the holy Archbishop of Cologne Anno II (1010-1075) can be represented as an example of a strong veneration of George in the German-speaking area . Anno came from St. Gallen, where the cult of St. George has been documented since the turn of the 9th century. The saint was also present during Anno's spiritual training in Bamberg, at the cathedral church, which was also consecrated to St. George. It was therefore logical that Anno continued to worship George. Visible evidence is the founding of the Georgstift in Cologne in the years 1056/1058. Perhaps Anno temporarily lived in a house directly on St. Georg, which was equipped with a Georg chapel. The veneration of George in the Siegburg Monastery , also founded in Anno, was probably mediated by the Archbishop. From the centuries that followed, further evidence of the cult of St. George was passed down, which can be associated with the veneration of saints in Annos: The Siegburg Benignus Shrine , created around 1190, shows the saints Anno, Erasmus, Georg and Nikolaus on its right. The Albinus shrine , made around 1186 in the St. Pantaleon Monastery in Cologne , also depicts - among the seven main Christian virtues - the martyr. Conversely, relics of Archbishop Anno were to be found in the Georgstift in Cologne.

St. Georgen in the Black Forest (11th century)

The St. Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest goes back to the veneration of St. George on the island of Reichenau, which must have influenced the Reichenau monastery governors, who came from the family of the St. Georgen monastery founder Hezelo in the 11th century. Her prayer house near her ancestral castle in Königseggwald was probably consecrated to St. George at the turn of the 10th to the 11th century and provided with corresponding relics. In the course of the foundation of the Black Forest monastery Hezelos and Hessos (1084/1085), relics of the saint finally came to St. Georgen in the Black Forest and led to the name foundation.

Patron of the German knights

After Georg became the patron saint of knights and men of war, his role was further promoted by the German Order of Knights , for example in Poland and the Baltic States. He is still the national saint of Lithuania today. Thirteen orders of knights are named after him.

The Habsburg emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519), who is also known as “ the last knight ”, has Saint George entered in his family tree and makes him the patron of his family. Maximilian is buried in St. George's Church in Wiener Neustadt .

Customs / representation

In addition to the described beginnings of dissemination and examples of veneration in the German-speaking area by churches and monasteries, nobility and knighthood as well as in poetry and literature, Georg also plays a role in popular belief . His dragon legend probably forms the template for the Further Drachenstich (from 1590), which was part of the Further Corpus Christi procession until it was banned .

Important peasant rules developed around Georg . For example, from St. George's Day (April 23), the fields were no longer allowed to be entered.

The house of Ritter St. Georg in Braunschweig is named after him and his picture has been on the north side of the Freiburg Schwabentor since 1903.

England

St. George ( English Saint George ) was the patron saint of Richard the Lionheart and his descendants and was appointed patron saint of all of England at the Oxford Synod in 1222 .

Various orders, such as the Order of the Garter (which is also called the Order of St. George in England), the George Cross or the George Medal derive their name from the saint. Edward III (1312–1377) had the George Chapel built for him in Windsor Castle. In his play Henry V (1600), William Shakespeare has the soldiers exclaim “ God with Henry! England! Saint George! ".

The red George Cross is of particular importance in the country's trade and war history. It is considered to be one of the first characters to represent the country. The cross on a white robe becomes the clothing of the English soldiers. Around 1277 the flag becomes the national flag and later also goes into the Union Jack . As a sign of England, it moved around the world with the conquests of the English crown and was accepted by many former colonies. Both in national coats of arms, as well as in trade and war flags. Even today, the White Ensign with the George Cross is the flag of war of the United Kingdom and India.

George's symbols also spread through the Church of England . For example, the Episcopal Church of the United States of America also uses the St. George Cross, even if the day of the saint no longer appears in the current calendar of the Book of Common Prayer from 1979.

In 1894 the Royal Society of St. George was founded.

Georgia

In Georgia the myth of White George , Tetri Giorgi , has been born since the middle of the 9th century. Georgian ethnologists place the origin of the name in connection with a pagan moon god , the mythological warrior Giorgi . In the eyes of the population, he is said to have merged with Georgia's patron saint, Saint George. Giorgi has the combative qualities of George and fights against injustice.

According to myth, the saint personally intervened in battles against Georgia's enemies. He is said to have participated on August 12, 1121 in the Battle of the Didgori against the Seljuks and in 1659 in the Bachtrioni uprising against the Persians .

Another legend tells that after death the saint was cut into 365 pieces and his remains were buried all over Georgia. Many church buildings in Transcaucasia are said to have been erected on George's burial sites.

Middle East

In the Middle East, the Arab Christians in Israel , Palestine , Lebanon , Syria and Jordan revere Georg under the name of Mār Jirdjis ( Arabic مار جرجس, DMG Mār Ǧirǧis ) and equate him with al-Chidr . There are pictures or reliefs of the saint above many front doors and there is a picture of George in most of the apartments. Instead of a picture of Christophorus there are Georg badges in the cars. Visitors to the grave in Lod bring bottles of olive oil with them, as oil that comes into contact with the grave plate is said to have healing properties. The consecration day of the church in Lod (November 3rd according to the Julian calendar) is celebrated annually and is the beginning of the Christmas business.

Remembrance day

| Catholic | Evangelical | Anglican | Orthodox (except Georgia and Bulgaria) | Orthodox (Bulgaria) | Georgian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 23 | April 23 | April 23 | April 23 | May 6th | November 23 |

| Not required day of remembrance in the general Roman calendar | Remembrance day in the Evangelical Name Calendar of the Evangelical Church in Germany | Remembrance day in some Anglican churches * |

Or on May 6th. ** If the public holiday falls in the week before Eastern Easter Sunday , then the day of remembrance shifts to Eastern Easter Monday. |

public holiday , Bulgarian Army Day | National holiday |

| * e.g. B. in the Church of England, but not in the Episcopal Church of the United States of America | |||||

| ** The old calendars celebrate in the years 1900 to 2099 on May 6th, April 23rd of the old calendar . | |||||

Patronage

More places

- German: St. Georgen , St. Jürgen , St. Jöris , Sankt Jörg

- as well as Saint George (English), Saint Georges (French), Sint-Joris (nl.), San Giorgio (Italian), San Jorge (Spanish), Sant Jordi (Catalan), São Jorge (Portuguese), Svätý Jur (Slovak.)

- Special

- George Island

- Georgenstein (Isar)

- Georgia

- Georgetown

- St. George's Fountain

- Georgenberg , St. Georg Canal , St. Georg estuary of the Danube

- Georgensgmünd

- German Scouting Society Sankt Georg

- Girl Scouting St. Georg

- Sankt Jørgens Sogn

- Sankt Jørgens Kirke in Landet Sogn , Denmark

- St. Georg (magazine) (for riders, Georg is the patron saint)

- St. Georg Schanze (Winterberg)

Important sacred buildings

- Bamberg Cathedral

- Pray Giyorgis, rock church in Lalibela (Ethiopia)

- George's Church in Reichenau-Oberzell

- St. Georg Minster in Dinkelsbühl

- Evangelical parish church St. Georg in Nördlingen

- Catholic parish church St. Georg in Vienna-Kagran

- St. George Church (Bocholt)

- St. Georg Monastery in Leipzig (Georgennonnenkloster)

- St. Georgen Monastery in the Black Forest

- Cistercian Monastery of St. Jöris and Parish Church of St. Georg in St. Jöris (French: St. George )

- Limburg Cathedral , also called Georgsdom. The cathedral of the Diocese of Limburg

- Sogn Gieri from the 10th century near Rhäzüns in the canton of Graubünden in Switzerland

- Deir Mar Georges in Syria, the monastery is said to be built over the cave of the dragon that Georg killed

- Catholic Church of St. Georg in Nonn near Bad Reichenhall

- Christkath. St. Georg Church in Zuzgen (Switzerland)

- St. Georgen Monastery in Stein am Rhein (Switzerland)

- Mosque of the Prophet Jirdis in Mosul (Iraq)

In art

St. George has always been a popular motif in art. Probably the oldest known depiction is a fresco from the 6th century in Egypt. The most famous paintings are perhaps by Albrecht Dürer ( Paumgartner Altar , 1503, Alte Pinakothek Munich), Donatello and Georg and Michael von Raffael in the Louvre in Paris . Probably the most comprehensive representation of various legends of St. George was created with the picture cycle in the Jindřichův Hradec castle in Neuhaus / Bohemia. In the Baltic region, the colossal group of riders of St. George slaying the dragon by the Lübeck sculptor Bernt Notke , made in 1489 for the Swedish ruler Sten Sture in the Nikolaikirche in Stockholm, is outstanding for the late Middle Ages. A plaster cast of the Stockholm group is in the Katharinenkirche in Lübeck . In St. Anne's Monastery Luebeck there is another group of sculptures of the Lübeck artist is Henning von der Heyde in three-quarter format. Among the large number of depictions, the bronze group of Georg and Martin von Klausenburg (1373) in the Prague castle courtyard is also worth mentioning. Also worth seeing is the gilded monument of St. George in the Thuringian city of Eisenach, which shows him with a dragon.

- Paintings

Fresco in the Sogn Gieri church , Graubünden in Switzerland (1731)

George's Altar, Prague , (1470)

Stained glass in Ulm Minster ( Hans Acker , around 1440)

Leaded glass window in St. Mary's Church in Sandwich, Kent

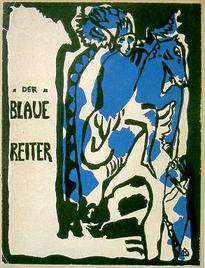

Cover illustration for the Almanac Der Blaue Reiter ( color woodcut by Wassily Kandinsky , 1911/12)

Fresco in the church of Narga Selassie on the island of Dek in Lake Tana , Ethiopia (18th century)

Wall painting at the Schwabentor in Freiburg im Breisgau ( Fritz Geiges , 1903 )

Wall painting at the gate to the castle courtyard of Neuschwanstein Castle

- Equestrian statues

Column in front of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague (1373, replica )

Statue of Bernt Notke in the Nikolaikirche in Stockholm

Statue in the New Parish Church of St. Margaret in Munich-Sendling (early 16th century)

Statue in the Michaelskapelle at Hohenzollern Castle

Statue at Basel Minster

heraldry

St. George is depicted in the following coats of arms:

Elpersdorf with Lindwurm

Heath (St. Jürgen)

Horní Jiřetín ( Obergeorgswalde )

Jiříkov (Czech Republic) ( Georgswalde )

Moscow (see also: Moscow Oblast )

Russia with Georg in the breastplate

Saint George (Canton of Vaud)

Šenčur (Slovenia) (Sankt Georgen)

Šentjur (Slovenia) (Sankt Georgen bei Cilli)

Svätý Jur (Slovakia) ( Sankt Georgen )

Sveti Jurij ob Ščavnici ( Sankt Georgen an der Stainz )

Weilheim , Tuttlingen district

numismatics

St. George is depicted on the following coins, among others:

Counter stamp z. B. on a Dreibrüdertaler (Kursachsen) or a Schmalkaldic Bundestaler

economy

St. George was also used as a trademark:

Trademark of the United Nuremberg Lebkuchen- und Schokoladenfabriken Haeberlein-Metzger AG (1922)

literature

- Horst Brunner: An overview of the history of German literature in the Middle Ages . Revised and bibliographically supplemented edition. Reclams Universal Library (RUB 9485), Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-15-009485-2 , p. 267, 326 .

- Michael Buhlmann: How St. George came to St. Georgen . In: Vertex Alemanniae . Issue 1. Association for Local History, St. Georgen 2001.

- Michael Buhlmann: On the beginnings of the veneration of George in Christian-early Islamic Palestine (6th – 7th centuries) . In: The Heimatbote . tape 14 , 2003, p. 37-47 .

- Michael Buhlmann: Sources on the medieval history of Ratingen and its districts: XII. Owned by the Cologne Georgstift in Homberg (1067? - shortly before 1148) . In: The couch grass . tape 73 , 2003, pp. 21st ff .

- Herbert Donner (Ed.): Pilgrimage to the Holy Land . The oldest accounts of Christian pilgrims to Palestine (4th – 7th centuries). 2nd, revised and supplemented edition. Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-460-31842-2 (first edition: 1979).

- Herbert Donner: St. George in the great religions of the Orient and Occident . In: Hans Martin Müller (Ed.): Reformation and Practical Theology. Festschrift for Werner Jetter . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1983, ISBN 3-525-58124-6 , pp. 51-60 .

- George . In: Hiltgart L. Keller (ed.): Reclams Lexicon of Saints and Biblical Figures, Legend and Representation in the Visual Arts. Drawings by Theodor Schwarz. Reclam, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-15-010570-6 , pp. 248–252 (first edition: 1968, current edition 2005).

- Wolfgang Haubrichs : Georgslied and Georgslegende in the early Middle Ages . Text and reconstruction. Scriptor, Königstein im Taunus 1979, ISBN 3-589-20573-3 .

- Wolfgang Haubrichs: Georg . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 4 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, Sp. 476 .

- Wolfgang Haubrichs: George legend, George veneration and George song. In: Sylvia Hahn, Sigrid Metken, Peter B. Steiner (eds.): Sanct Georg. The knight with the dragon. Lindenberg 2001, pp. 57-63.

- Achim Krefting: St. Michael and St. Georg in their intellectual-historical relationships . In: German work at the University of Cologne . No. 14 . Diederichs, Jena 1937 (in Fraktur).

- Eckhard Meineke , Judith Schwerdt: Introduction to Old High German . Schöningh (UTB 2167), Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2001, ISBN 3-8252-2167-9 , p. 115 ff .

- Elisabetta Lucchesi Palli u. a .: Georg . In: Engelbert Kirschbaum, Wolfgang Braunfels (Ed.): Lexicon of Christian Iconography. Volume 6 Iconography of Saint Crescentianus from Tunis to Innocentia . Herder, Freiburg in Breisgau 1974, ISBN 3-451-14496-4 , Sp. 365-390 .

- Gabriella Schubert : St. George and St. George's Day in the Balkans . In: Journal of Balkanology . No. 4 . Harrassowitz, 1985, ISSN 0044-2356 .

- Saint George and his cycle of pictures in Neuhaus / Bohemia ( Jindřichův Hradec ) . Historical, art historical and theological contributions. In: Ewald Volgger (Ed.): Sources and studies on the history of the Teutonic Order . No. 57 . Elwert, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-7708-1212-3 (including: Hubertus Halfbas: The truth of the legend ).

- Jacobus de Voragine : Legenda aurea . In: Rainer Nickel (Ed.): Reclams Universal Library RUB 8464 . Reclam, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-15-008464-9 , pp. 192-197 (Latin, German).

- Hans Georg Wehrens: Georg u. a. In: The city cartridge of Freiburg im Breisgau . Promo, Freiburg in Breisgau 2007, ISBN 978-3-923288-60-1 , p. 6–25 and 45 ff .

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : GEORG. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 208-209.

- Paul W. Roth: Soldier Saints . Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-222-12185-0

Web links

- Literature by and about Georg in the catalog of the German National Library

- St George, patron saint of England on britannia.com

- martinus.at on patronage ( Memento from February 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- The saint on the altar of grace of fourteen saints

Individual evidence

- ^ Richard Benz (translated from Latin): Von Sanct Georg. In: Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints .

- ↑ Helen Gibson, 1971: St. George The Ubiquitous, Saudi Aramco World ( Memento of February 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ Wolfgang Haubrichs: Georgslegende, Georgsverehrung and Georgslied . In: Sylvia Hahn, Sigrid Metken and Peter B. Steiner (eds.): Sanct Georg. The knight with the dragon . Lindenberg 2001, p. 57-63 .

- ^ Stephan Müller: Old High German Literature . S. 309 f .

- ^ Rudolf Kriss : "St. Georg, al-Ḫaḍr (Ḫaḍir, Ḫiḍr)" in Bavarian Yearbook for Folklore 1960, pp. 48–56.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | George |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | George of Cappadocia |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Holy, early Christian martyr |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 3rd century |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | uncertain: Cappadocia , Roman Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 23 at 303 |

| Place of death | uncertain: Lydda , Roman Empire |