Henry V (drama)

Henry V ( English The Life of Henry the Fifth ) is a drama by William Shakespeare , the plot of which relates to the life of King Henry the Fifth and is set in the Hundred Years War around the Battle of Azincourt . Its world premiere probably took place in 1599 , and it was first published in 1600 . It forms the conclusion of the so-called Lancaster tetralogy . Heinrich V is a play with a broad social distribution and a figure constellation that goes beyond the national framework.

action

The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely are concerned about a bill that has been submitted to King Henry V which, if passed, would mean the confiscation of considerable church property. Then the archbishop had the idea of drawing the king's attention to a war against France. In an elaborate argument he explains Henry's claim to the French throne because Henry's great-great-grandmother was a daughter of the French king; In France, of course, female descent does not apply, which is why the invasion of the country is the most appropriate means. Heinrich's concerns that the Scots could take advantage of his absence and that of the troops to invade England, he dispels with the suggestion that Heinrich should only go with a quarter of the army against France. When the Dauphin of France rejects the young English king's claims and sends him - an affront - a box full of tennis balls, Heinrich announces that he wants to conquer France.

But before departure, the first danger arises: Bribed by the French, the English nobles Sir Thomas Gray, Lord Scroop von Masham and the Count of Cambridge conspired to kill Heinrich - the plot is uncovered, and Heinrich leaves the men execute. Now the way is clear. Heinrich : Happy at sea! The flags are already flying. No king of England without France's throne! (II.2) On the other hand, the mood of some soldiers (Pistol, Nym, Bardolph), who once served under old Falstaff and are now mourning the death of their leader, is more gloomy.

Heinrich begins the war with the siege of Harfleur . Since initial fighting brings no decision, he calls on the city governor to open the gates, otherwise he would leave the city to his soldiers, which would mean murder and pillage; in response to this threat, the governor declares to open the gates. Heinrich has Harfleur fortified and occupied again and wants to spend the winter in Calais with the main part of his exhausted army . Bardolph has been sentenced to death for a theft in Harfleur - the king approves the sentence against his former friend, and Bardolph is hanged.

In the meantime the French king has gathered a sizable army and is thus opposing Heinrich at Azincourt. The chances for Heinrich are slim: 12,000 tired soldiers against 60,000 well-rested enemies. Accordingly, the French long for morning, while the English fear it. But Heinrich sees the positive: "There is some soul of goodness in things evil" (IV.1.4). Unrecognized, he mingles with his soldiers, and the conversation may come. a. on the responsibility of the king:

Want. : But if his cause is not good, the king himself has

- to give a difficult account, [...] on the last day [...] all shout:

- » We died here and there «, [...]

K. Hein. : [...] War is his [God's] scourge, war is his tool

- the vengeance,

- […] Every subject's duty belongs to the king,

- every subject's soul is his own! (IV.1)

Before the battle of Azincourt, Heinrich gave a great speech ( St. Crispins speech ), with which he encouraged his soldiers, and achieved the apparently impossible: Despite their numerical superiority, the French were crushed. Out of ten thousand French dead, only twenty-nine English died. The capture of the English camp and the slaughter of the pages by the French did not change that. In this overwhelming victory, Heinrich recognizes God's intervention and orders the Te Deum to be sung.

The fifth and final act leads to a reconciliation between England and France. At Troyes, the Duke of Burgundy brings the warring kings Karl and Heinrich together and in his speech clarifies the consequences of the cruel war. The peace agreement also includes the wedding of Heinrich to the French princess Katherina, which is why Heinrich will also hold the French throne after Karl's death. So the piece ends with a peaceful scene and optimistic expectations:

Isab. : God, best founder of all marriages,

- [...] So be the marriage between your realms, [...]

- That English and Franks are just the names

- be of brothers: God say amen! (V.2)

Literary templates and cultural references

The title character

The title character Henry V is introduced after the epic first prologue through a conversation between the Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop Ely. At this point he is characterized so comprehensively that the audience cannot surprise any of his actions later in the play. He is portrayed as an exemplary ruler who demonstrates all the qualities of a prince's mirror . Even more, Heinrich shows the same closeness to the people as the Tudors who ruled in Shakespeare's time demonstrated. With the death of his father, the young king changes from a dissolute, vicious prince to a responsible and serious ruler. Shakespeare describes an educational tradition that has been in place for young aristocrats until modern times: that they were given a great deal of freedom to gain experience after completing their formal training and before taking on responsibility. Heinrich suddenly (I, 1,32) became someone else, moreover a scholar in theology, admirably educated. He masters political theory like the discourses of war theory - as if he had never dealt with anything else. A larger-than-life hero is introduced to the audience - and Heinrich's appearance in the second scene confirms the expectations suggested by Canterbury and Ely. Heinrich urges the two of them to investigate the legal situation with regard to his claim to the French throne. As chief judge and general, he reserves the right to make the decision, but respects the applicable international law . For him, the question of responsibility for the consequences of a war campaign is an oppressive problem that needs clarification under international law. Shakespeare's Heinrich is character and morally strengthened and legally empowered to tackle the tasks at hand as the embodiment of the ideal ruler.

Shakespeare's sources

Shakespeare's most important source for Henry V was the historical work of Raphael Holinshed , the Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland , which he used for all British subjects . Shakespeare probably used the second edition (1586–87). Shakespeare's dramatic portrayal of historical material was not always the first play on the material. The influence of the history of " The Famous Victories of Henry V " is unmistakable with Henry V too . The author is unknown - all that can be proven is that it was written before 1588 and that the title was entered in the Stationers Register in 1594 . Clear similarities with Shakespeare's history show that he knew the play well. And the influence of " The Famous Victories of Henry V " is evident in details such as: B. in the following scenes: The tennis ball scene (I, 2); the French asking for mercy Prisoners (IV, 4); and in the advertising scene (V, 2). In the preparatory work for his Roman dramas, Shakespeare used his main source, the translation of Plutarch by Sir Thomas North , and Tacitus Annales, which were translated by Richard Grenewey in 1598 . The famous night scene (IV, 1), in which King Henry goes disguised among his troops to capture their mood, clearly indicate Tacitus' description of how Germanicus went to the Roman legionaries in disguise to check their morale .

Historical background

When Henry V (1387–1422) ascended the English throne in 1413, the initial situation was ambivalent: his predecessor and father, Henry IV (1367–1413), had strengthened England domestically and England's financial position was better than it had been for a long time . But England's position in the struggle for the French crown - in the so-called Hundred Years War (1339–1453) - was bad: apart from individual bases like Calais and Cherbourg , all territories on the mainland had been lost. After the suppression of conspiracies by the politico-religious movement of the Lollards and a conspiracy that was supposed to bring the Earl of March to the throne, but was betrayed by him, Henry's rule in England was secured. He used a domestic political crisis in France to defend his claims there by force of arms.

The Battle of Azincourt

The Battle of Azincourt on October 25, 1415 was a triumph of the English over the French army of knights. Disorganization and a lack of discipline led to the French knights running uncoordinated and in small groups against a well-prepared and fortified position of the English and being beaten by dismounted knights and archers (see Hans Delbrück - History of the Art of War). Of the allegedly 25,000 French, 8,000 to 15,000 - the numbers are probably greatly exaggerated - fell or were taken prisoner, while the English had only around 400 killed. Most heavily, however, were the losses of the high nobility, as almost all of the leaders of the French knights were killed in the battle.

Treaty of Troyes

The high blood toll of its nobility weakened France lastingly. Henry V was able to occupy large parts of northern France and secured his claims to the French throne in the Treaty of Troyes in 1420 through his marriage to Catherine of Valois , the daughter of the French king Charles VI. The Dauphin Charles VII (1403–1461), who had thus actually been ignored, refused to recognize the treaty, but was only able to change the balance of power in France with the help of the charismatic Joan of Arc (1412–1431).

Prologue / prologue speaker

The prologues and especially the prologue speaker have an important connecting function in Henry V , because the piece is characterized by great time and spatial distances. The prologue speaker, acting as a chorus, addresses the audience right at the beginning of the piece and explains these circumstances (28-31).

- [...] because it is your thoughts that must now adorn our kings.

- Carry them here and there, skipping times, transforming the achievement

- many years in an hour glass.

Prologues are extremely rare in Shakespeare. In Henry V they represent a planned further development of the prologue figure and the epilogue contained in Henry IV. The function of the prologue is to be seen in relation to the piece as an independent genre, history . At the end of the first prologue, the speaker addresses the audience with a request that clarifies the function and genre of the piece (32).

- [...] allows me as a choir access to this story [history] ...

In Shakespeare's time, the prologue speaker was an actor dressed in black and in Henry V he has the second longest role after the title character with 223 lines. It is conceivable that at the time of the premieres Shakespeare himself took on the role of the prologue speaker, since at the beginning of the epilogue the speaker calls himself "our bending author" .

text

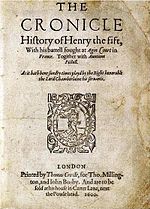

The text by Henry V used today usually goes back to the folio edition of 1623 (F1), the first, posthumously published complete edition of Shakespeare's dramas. Compared to the fourth edition (Q1) of 1600 (see illustration), the folio version offers a complete text. This is more than twice as long as the text of the quartos and also contains the prologues. For the first time, there is also a division of nudes here, even if not in the places the reader, and especially the viewer, is used to today, i. H. before the prologues. Today's nudes and scenes go back to the Shakespeare editors of the 18th century and corresponded to the dramaturgical requirements of the closed stage. The Elizabethan stage, however, was open on three sides (see illustration).

At several points in the play, comparisons with Roman history are made , evidence that Shakespeare was already working on Julius Caesar (1599). In one case, the relationship between Henry V and Julius Caesar cannot be overlooked, even for those less familiar with the matter. The introductory words of Mark Anton's famous speech : "Friends, Romans, countrymen, ..." (III, 2.75), are used in the prologue to Act 4 by Henry V as "... brothers, friends and countrymen." (IV, 34) anticipated.

interpretation

Henry V is not only a patriotic play, it also contains very nationalist statements. It was therefore far less appreciated in the cosmopolitan 18th century than in the 19th and 20th centuries. It was particularly popular in England when there was war, for example during the Boer Wars and in both World Wars . The problem of patriotism and nationalism in Henry V shows how much the Elizabethan age - represented here by Shakespeare - unites universalistic-medieval and more recent currents that emerged in the Renaissance.

Kath .: Is it possible that I should love the enemy of France?

K. Hein. : No, it is not possible that you are the enemy of

Love France, Kate; but by loving me, loving

you the friend of France, because I love France

so much that I don't want to give up any village from it; I want

have it all to myself . And, Kate, if France

mine is and I yours, then France is yours and

you are mine (v. 2)

The assessment of another nation is fundamentally based on its behavior against the background of Christian community. The value of these Christian nations depends directly on the moral behavior of their God-appointed princes and kings. The idealized leader in the person of Henry is faced with a degenerate French nobility. What is more, the Dauphin and other aristocrats indulge in excessive self-esteem and openly show their contempt for the English people and their leadership. Numerous clichés that are also familiar to us are articulated or suggested in order to make the French appear as a degenerate people from the outset. The English themselves are under criticism from the French nobility (III, 5) as the physically stronger ones. This representation of the contradictions between the English and the French before and after the battle is consistently continued.

Apart from the conflict between France and England and the experience of the Hundred Years' War, which had to be interpreted at that time, the piece can not be described as conflict-free. The actual conflict can be found in Heinrich's title character; he does not act out of private interest, but the conflict is of an internal nature and is carried out in it. This inner clash of the king with his intense urgency is expressed by him through his poetically exaggerated speeches up to the disguise scene (IV, 1).

reception

The St. Crispins Day speech in particular is often referred to in Anglo-American culture when it comes to motivating or rewarding a limited number of people for a particular challenge. For example, the title of the American TV miniseries Band of Brothers - We were like brothers also refers to the address Shakespeare put in Henry V's mouth, as does the quote We few, we happy few, we band of brothers in a window of the Westminster Abbey , dedicated to the Royal Air Force's efforts in the Battle of Britain .

Film adaptations

- Heinrich V , directed by Laurence Olivier from 1944

- Henry V. , by and with Kenneth Branagh from 1989

- The King , by David Michod from 2019

In the first two adaptations, the dialogues from the original were largely adopted.

Text output

- English

- William Shakespeare: King Henry V. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Edited by TW Craik. London 1995. ISBN 978-1-904271-08-6

- William Shakespeare: King Henry V. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Edited by Andrew Gurr. CUP 2005. ISBN 978-0-521-61264-7

- William Shakespeare: King Henry V. Oxford Shakespeare (Oxford World's Classics). Edited by Gary Taylor. OUP 1982. ISBN 978-0-19-953651-1

- German and bilingual.

- August W. von Schlegel , and Ludwig Tieck : All works in one volume - by William Shakespeare . Otus, 2006, ISBN 3-907194-35-7 .

- Max Wechsler (introduction and commentary by Barbara Sträuli Arslan): William Shakespeare: "King Henry V". English-German study edition . Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-86057-555-4 .

- Dieter Hamblock: William Shakespeare - King Henry V, King Heinrich V. English-German edition . Verlag Philipp Reclam , Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-15-009899-8 .

literature

- Jens Mittelbach: The art of contradiction. Ambiguity as a principle of representation in Shakespeare's Henry V and Julius Caesar . WVT Wiss. Verl., Trier 2003, ISBN 3-88476-581-7 .

- THE PEOPLE'S PLOETZ: Extract from history 5th edition . Verlag Ploetz, Freiburg - Würzburg 1991, ISBN 3-87640-351-0 .

- Maurice Keen: Chivalry . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf - Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-7608-1216-3 .

- Tanja Weiss: Shakespeare on the Screen: Kenneth Branagh's Adaptions of Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main - Berlin - Bern - New York - Paris - Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-631-33927-5 .

- Ewald Standop & Edgar Mertner (1992). English literary history . Wiesbaden, Quelle & Meyer, 1992. ISBN 3-494-00373-4

Web links

- MIT, English text, Arden version Henry V.

- German text, zeno.org. Schlegel-Tieck version of Heinrich V.

- British Library Shakespeare in Quartos Henry V. 1st Quarto 1600

- War piece or anti-war piece? The subjectification of war in Shakespeare's "Henry V." by Ralf Hertel, in Manfred Leber, Sikander Singh Ed .: Explorations between war and peace. Saarbrücken lecture series on literary studies, 6. Universaar, Saarbrücken 2017, pp. 53–68. Full text