As you Like It

As You Like It ( Early Modern English As you like it ) is a play by William Shakespeare , written probably 1599th

action

Duke Friedrich disempowered his older brother Duke Senior, who thereupon went into exile with a number of loyal followers in the forest of Arden . Rosalind, Senior's eldest daughter, stays at Friedrich's court with her friend Celia, Friedrich's daughter. After the death of Rowland de Bois, his eldest son Oliver becomes the main heir, his youngest son Orlando receives only one thousand crowns; in addition, Oliver refuses him adequate training. Orlando hits his older brother in the throat during an argument. Oliver wants Orlando to be harmed in a wrestling match by the court wrestler Charles. Unexpectedly, however, Orlando wins the fight; Rosalind, who had seen the fight, falls in love with him and he returns her feelings. When Orlando learns that Duke Friedrich is resentful to him, he flees to the Arden Forest. Rosalind is banished by Friedrich. Together with her friend Celia, she plans to flee to her father. To do this, she disguises herself as a young man and takes on the false name "Ganymede", while Celia pretends to be a simple girl named Aliena. Together with the fool's touchstone, they too reach the forest of Arden.

At the table at Herzog Senior's loyal Lord Jacques philosophizes about life and the world. Orlando has been taken in by Duke Senior and writes love poems that he hangs on trees for his lost Rosalind. Rosalind finds the poems and, disguised as Ganymede, asks Orlando about his true feelings and promises to cure Orlando of his lovesickness if Orlando woos him as if he were Rosalind, which Orlando agrees to. Both fall in love more and more. In the forest, Probstein and the goatherd Käthchen decide to get married. The young shepherd Silvius woos the shepherdess Phöbe, who, however, is in love with Ganymede and writes a love letter to the supposed man.

The idyll in the forest is threatened when Friedrich sends Oliver out to find Orlando - he hopes to get hold of the two runaways Celia and Rosalind. In the forest, Oliver is almost killed when a snake winds around the sleeping man's neck and then a lioness appears. However, he is rescued by Orlando, who drives away the animals; Through this experience Oliver becomes a new person and the brothers are reconciled. Oliver and Celia fall in love and the wedding is supposed to take place the next day. Orlando regrets not being able to marry his Rosalind, but Ganymede promises to make this possible through magic. At the wedding she reveals herself as Rosalind, Phöbe then turns to her admirer Silvius, and Probstein and Käthchen also join. All four couples are married by Hymen , the god of marriage, and a big wedding celebration begins. In the middle of the celebrations, the wedding party learns that Duke Friedrich met a religious person on the way to the Arden Forest, who converted him to a peace-loving life, and that is why Duke Senior is giving the Duchy back to Duke Senior.

Literary templates and cultural references

In his comedy, Shakespeare uses the shepherd's novel Rosalynde, or Euphues 'Golden Legacie ( Rosalinde or Euphues' golden legacy ) by his contemporary Thomas Lodge as a direct reference . This pastoral prose romance appeared in print for the first time in 1590 and was published in numerous new editions in the following years, one of them in 1598. Shakespeare roughly takes over the plot structure and most of the characters, but adds further elements to the plot and shifts the focus and proportions; in addition, he extends the circle of characters to include the melancholic Jacques and the fool Touchstone ( Probstein ). Whether Shakespeare also knew Lodges probable source, the medieval poem The Tale of Gamelyn (around 1350), can no longer be clarified with certainty today.

In his play, Shakespeare focuses on the pastoral love scenes in the forest of Arden, but in contrast to the novel, not only strings together the courtship of the three couples additively, but also links them together in a virtuoso manner so that they mirror each other ironically . With the introduction of the melancholic Jacques and the fool Touchstone, who, as commentary characters, further illuminate the thematic contrast between court life and shepherd existence, Shakespeare expands this ironic technique of reflection in his work. For example, Touchstone's unromantic love affair with the country girl Audrey ( Käthchen ) varies the motif of pastoral love romance on the level of sensual desire and thus sets precisely the pastoral conventions and axiomatic values of the paradisiacal idyll of shepherd existence and the idealistic claims of romantic love, which are unquestionably accepted at Lodge Question.

In contrast to Lodge, Shakespeare is not concerned with creating an unclouded picture of pastoral life or love happiness. The ambiguous title As You Like It initially promises the audience what they like, and thus takes into account the preference for pastoral drama or poetry in the taste of the time; However, in the course of the play this assumed expectation of the audience is broken and questioned several times. Dramaturgical elements such as Rosalinde's role-play-within-a-game, which is additionally reinforced by the Elizabethan cross-casting , i.e. the casting of female roles by male actors, as well as her stepping out of the role lead in Shakespeare's comedy to a self-reflective thematization of the dramatic design and thus establish a meta-fictional or metadramatische dimension of As You Like It . The audience not only receives what is expected to be pleasing in anticipation of pastoral poetry: Rosalinde's request at the end, "to like as much of the play as please you" (V, 4,210 f.) Is not a simple modesty formula, but refers to it the structural complexity of the work, which goes far beyond the role it represents. With this, Shakespeare breaks through the seriousness of the pastoral world of his model of Lodge at decisive points, in which the conventional characters of this shepherd novel perform their humorless rituals with ornate speeches and self-talk.

Dating

The time when this Shakespeare comedy was written has not been passed on, but it can be narrowed down to the period between autumn 1598 and summer 1600 with an unusually high degree of certainty and accuracy. In the book Palladis Tamia, Wit's Treasury by Francis Meres, published at the end of 1598 , which contains a catalog of the works of Shakespeare known up to that point in time, there is still no reference to As You Like It ; the piece was therefore most likely not written before autumn 1598 ( terminus a quo ). The latest possible time of writing ( terminus ad quem ) can also be determined very precisely: On August 4, 1600, the printing rights to this work and three other pieces by Shakespeare were entered in the Stationers 'Register , the register of the printers' guild.

Various indications inherent in the text also speak for the assumption of a time of origin between the autumn of 1599 and the summer of 1600. The song It was a lover and his lass (v.3) can also be found in Thomas Morley's The First Book of Ayres (1600); Phoebe cited in III, 5.82 from Marlowe Christopher narrative poem Hero and Leander , which was published in two editions in 1598, and Jacques plays with "All the world'sa stage" (II, 7.139) on the theme of the 1599 opened Globe Theater at . In Shakespeare's research, it is generally accepted that the work be dated to 1599 within this possible period.

Text history

The entry in the Stationers' Register from August 1600 contains the title of the comedy and the additional blocking notice ... to be staied . The reasons why this blocking entry was added is no longer known today. It is possible that such a blocking entry should prevent unauthorized pirated prints or at least make them more difficult, or prevent a competitor's publication project. It is also possible, however, that Shakespeare's actors not only wanted to secure their printing rights with such an entry, but also wanted to announce their intention to sell the printing rights to a publisher.

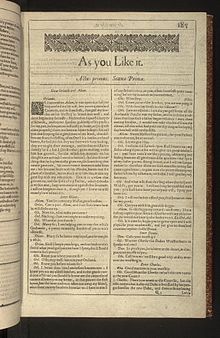

Despite the entry of the printing rights to a single publication of the work, there is no four-high edition of this play. Why the work was not published individually as a four-high print after registration in the Stationers's Register can no longer be determined with certainty today. A printed edition of the work did not appear until 23 years later in the first Shakespeare Complete Edition ( Shakespeare's Folio ) of 1623.

The folio edition provides the only authoritative source of text; this first printed text is largely reliable and comparatively low in errors and hardly problematic even for today's editors. The template for the print was probably a copy of the prompt book made by a professional scribe or a rough version of Shakespeare's manuscript ( foul papers ).

Performance history and cast

As You Like It is still one of the most played and widely read Shakespeare dramas. The actual history of the effect of the piece began relatively late, when the genre of the pastoral had already largely lost its validity. In the 18th century the documented successful stage tradition of the work begins; There are no records or evidence of previous performances. In 1723 an adaptation of the work by Charles Johnson was performed under the title Love in a Forest at the Theater Royal Drury Lane . In this adaptation, rowdy and clown scenes from A Midsummer Night's Dream were embedded as a game in the game in a drastically simplified plot of As You Like It . With the first documented performance of the original work at the same theater in 1740, a series of productions that has lasted up to the present began, with which the piece firmly established itself in the repertoire of the English and German theaters. As you like it was first performed in Germany in 1775 by the Wieland- inspired drama group from Biberach.

Similar to Shakespeare's other great comedies, As You Like It deals with serious topics such as the relationship between game and reality or existence and appearance, the importance of love and the relationships between the sexes for the development of one's own identity or the possibilities and limits of one alternative life in nature, in which the forest appears as a symbolic place of testing and rehabilitation. The particular fascination that this comedy has exerted on the theater audience from the 18th century to the present is not based solely on its themes, but in particular in its design as a theater about theater. The actors on stage not only play their role as characters in the play, but also act as players who demonstrate their art or tricks. The viewer is shown how to drop or change roles, how to make a different figure of oneself, how to be in a role and at the same time stand next to it; Having fun playing the theater enables others to have fun.

The role of Rosalind in particular has repeatedly attracted famous actresses since the 18th century; this role was played by actresses such as Peggy Ashcroft (1932), Edith Evans (1936), Katharine Hepburn (1950) or Vanessa Redgrave (1961), to name just a few. The large number of successful performances on German stages include, above all, productions that are significant in terms of theater history, such as those by Otto Falckenberg (1917, 1933), Heinz Hilpert (1934) or Gustaf Gründgens (1941).

In recent decades, there has been a particular tendency to return to Elizabethan cross-casting in order to accentuate the ambiguities of the sexes. The 1967 performance of Clifford Williams, who, against the background of Jan Kott 's Shakespeare interpretation, had an all-male ensemble perform in a surrealistic forest of the “Bitter Arcadia”, was groundbreaking for such a staging practice .

In Germany, Peter Stein took up Kott's suggestions and staged an impressive performance in the Spandau CCC film studios in 1977, in which the audience had to laboriously escape into the forest of Arden. In productions such as that by Declan Donnellan (1991), the role of Rosalind was cast by a colored actor; In 1993 Katharina Thalbach had an all-male ensemble perform in her production of How You Like It at the Berlin Schiller Theater; in her performance in 2009 at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm , however, she cast all roles exclusively with female actors.

In 2018, Heinz Rudolf Kunze and Heiner Lürig performed their version of How You Like It in the Theater am Aegi in Hanover.

Text output

- English

- Alan Brissenden (Ed.): As You Like It. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953615-3

- Juliet Dusinberre (Ed.): William Shakespeare: As You Like It. Arden Third Series. Thomson Learning, London 2006, ISBN 978-1-904271-22-2

- Michael Hattaway (Ed.): William Shakespeare: As You Like It. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-73250-5

- German

- Frank Günther (Ed.): William Shakespeare: As you like it. Bilingual edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2nd edition Munich 2014 [1996], ISBN 978-3-423-12488-1 .

- Ilse Leisi and Hugo Schwaller (eds.): William Shakespeare: As You Like It. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2000, ISBN 3-86057-558-9 .

literature

- Michael Dobson, Stanley Wells (Eds.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7

- Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 309-312.

- Bernhard Reitz: As You Like It. In: Interpretations - Shakespeare's Dramas. Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, reprint 2010, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , pp. 207-237.

- Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2

- Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8

- Stanley Wells , Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 978-0-393-31667-4

- Sound carrier

In October 2019 Heiner Lürig released an album with the songs of the Kunze Lürig musical As You Like It , sung by the performers of the world premiere in Hanover in 2018 and the composer.

Web links

- As you like it - German translation by Schlegel on Projekt Gutenberg-DE

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rosalind chooses the false name of the mythological figure of Ganymede , with explicit reference to the supreme Roman god Jupiter , in order to embody strength in her supposed role as a man (cf. I.3.115ff: “I'll have no worse name than than Jove's own page. " ). On the other hand, Celia wants to use her newly chosen false name to express her changed condition with her choice of the name "Aliena", which goes back in Latin to the name for a "stranger" (cf. I.3.123: "Something that hath a reference to my state: No longer Celia, but Aliena. " ). The name Ganymede was quite common for young men in Elizabethan times, but could also refer to a homo-erotic relationship with an older man. See, for example, the commentary on the corresponding text passage I.3.115ff by Jonathan Bate and Eric Eric Rassmussen in the RSC edition published by them : William Shakespeare - Complete Works. Mamillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire, ISBN 978-0-230-20095-1 , p. 486.

- ↑ See the following passages in the text: “And so, from hour to hour, we ripe and ripe, And then, from hour to hour, we rot and rot, And thereby hangs a tale.” (II.vii.26-28 ) "All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; "(II.vii.139-141)

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 422, and Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd reviewed and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 147. See also Bernhard Reitz: As you Like It. In: Interpretations - Shakespeare's Dramen. Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, reprint 2010, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , p. 210 f. See also Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , p. 309.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 422.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 422. See also Bernhard Reitz: As you Like It. In: Interpretations - Shakespeare's dramas. Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, reprint 2010, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , p. 210 f. and 234. Cf. also Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer. 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 147.

- ↑ See Bernhard Reitz: As You Like It. In: Interpretations - Shakespeare's Dramas. Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, reprint 2010, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , p. 208.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook . Kröner, Stuttgart 2009. ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 422, and Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer . 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 147. See also Stanley Wells , Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, corrected new edition 1997, ISBN 978-0-393-31667-4 , p. 392. See also Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 232. A detailed discussion of the dating question can also be found in the introduction to Alan Brissenden's ed. Oxford edition of As You Like It , Oxford University Press, 2008 reissue, ISBN 978-0-19-953615-3 , pp. 1-5.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook . Kröner, Stuttgart 2009. ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 422, and Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer . 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 147. See also Stanley Wells , Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, corrected new edition 1997, ISBN 978-0-393-31667-4 , p. 392. See also Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 232. A detailed discussion of the hypotheses on possible reasons for the blocking notice in the entry in the Stationers' Register can be found in the introduction to Alan Brissenden's ed. Oxford edition of As You Like It , Oxford University Press, new edition 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953615-3 , pp. 1–5, esp. P. 2 ff. On the background of the ban on the publication of satirical works of On June 1, 1599, Brissenden thinks it is also conceivable that Shakespeare's drama troupe, Lord Chamberlain's Men, did not get permission to print As You Like It during the political turmoil around 1600 . However, there is no clear evidence or evidence for the acceptance of such a printing ban (see ibid., P. 2 ff.)

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook . Kröner, Stuttgart 2009. ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 422, and Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer . 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 147. See also Stanley Wells , Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, corrected new edition 1997, ISBN 978-0-393-31667-4 , p. 392. See also Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 232. See also the introduction to Alan Brissenden's ed. Oxford edition of As You Like It , Oxford University Press, 2008 reissue, ISBN 978-0-19-953615-3 , pp. 84-86.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 148.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 426. See also Shakespeare in Performance: Stage Production . From Internet Shakespeare Editions , accessed February 28, 2016.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 426 f., And Ulrich Suerbaum: Der Shakespeare-Führer. 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 148.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd revised and supplemented edition, Reclam, Dietzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 153.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 427. On the performances on English stages since the 18th century, see also Alan Brissenden (ed.): As You Like it. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953615-3 , pp. 50-81, here especially pp. 63 ff. And 72.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 427. See also Alan Brissenden (Ed.): As You Like It. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953615-3 , pp. 66 f. See also that of Heather Dubrow ed. Edition of As You Like It , Evans Shakespeare Series, Wadsworth, Boston 2012, ISBN 978-0-495-91117-3 , p. 209.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 427. On Stein and Donnellan's productions, see also Alan Brissenden (ed.): As You Like It. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953615-3 , pp. 50-81, especially pp. 67 ff. And 75 f. See also the review of Donnellan's production in the New York Times of July 28, 1991, online As You Like It , in Its Native Language . accessed on February 29, 2016. See also the review of Thalbach's productions in the Tagesspiegel from January 19, 2009, online How Thalbach likes it , accessed on February 29, 2016, as well as the announcement How you like it on AVIVA , accessed on 29 February 2016.

- ↑ http://wieeseuchgefaellt-musical.de/ - accessed on June 2, 2018

- ↑ http://wieeseuchgefaellt-musical.de/ - accessed on August 4, 2018

- ↑ http://www.heinerluerig.de/neuheiten/ , accessed on October 1, 2019