Othello

Othello, the Moor of Venice ( Early Modern English The Tragedy of Othello, The Moore of Venice ) is a tragedy by William Shakespeare . The work is about the dark-skinned general Othello , who, out of exaggerated jealousy promoted by the schemer Iago , kills his beloved wife Desdemona and then himself. Shakespeare's source was a tale from the collection Hecatommithi by the Italian Giraldo Cinthio . The author completed the work around 1603 or 1604. The first quarto print dates from 1622. A year later the first folio edition appeareda revised version of the piece. The earliest performance known from an entry in the Accounts Book of the Master of the Revels was a performance of the play by Shakespeare's troupe in the great ballroom of the royal residence in Whitehall on November 1, 1604. The first German translation was part of the Complete Edition of Shakespeare's Theatrical Works (1762–1766) by Christoph Martin Wieland . The German premiere took place in Hamburg in 1766 . A hugely successful and popular work even in Shakespeare's time, Othello has enjoyed a dense and uninterrupted stage presence since its creation. The best-known adaptation of the work is Giuseppe Verdi's opera Otello .

overview

main characters

The title character , Othello , is portrayed as a noble, sincere character, although his dark complexion makes him an a priori alien in Venetian society. The common translation "Moor" = Mohr as an outdated term for a black African is misleading; more correct would be the term " Moor " for an inhabitant of Muslim North Africa. There is no unanimous opinion in Shakespearean scholarship about the color of Othello's skin. Islam is not mentioned in the play; rather, it is implied that Othello is a Christian . Moors and other dark-skinned peoples were mostly portrayed negatively in Shakespeare's time - as criminals, barbarians or hot-blooded, dissolute savages. The "noble" Othello thus forms a contrasting figure, although his appearance is considered ugly by the Venetians (except for Desdemona). The name Desdemona or Disdemona ( Greek Δυσδαιμόνα Dysdaimóna ) is possibly derived from the ancient Greek adjective δυσδαίμων , dysdaímon = "unfortunate", "under an evil star", "haunted by fate". The schemer Iago (English: Iago ) has the greatest speaking role among non-titular characters in all of Shakespeare's plays. His text portion is even more extensive than that of Othello himself. Several motives are given for Jago's intrigue: the missed promotion, but also the suspicion that his wife is cheating on him with Othello. However, Jago himself recognizes this suspicion as a pure pretext. His self-reflection reveals that he is acting out of pure malice and consciously does not want to take any other path. Modern interpretations also accuse him of racism .

plot

Act I

[Scene 1] The nobleman Roderigo and Iago , a low-ranking soldier, are out and about in Venice at night. Roderigo complains that Iago has kept something important from him, although he - the wealthy one - always gave him money. However, Iago claims to have been taken by surprise and is also angry because he was passed over for a promotion. An inexperienced competitor - Michael Cassio from Florence - was preferred, although he, Iago , had always served his superior - a Moor - faithfully ("... I know my worth, the post is mine."). Now he has decided to pretend ("...I'm not what I am.") and only serve out of selfishness. When they arrive at their destination - the house of a Venetian - the now masked Iago asks his companion to wake up the master of the house Brabantio by shouting loudly . Brabantio appears at the window, complains about the noise and is overheard that his daughter has secretly eloped with a stranger. The master of the house recognizes one of the nocturnal disturbers - Roderigo - as his daughter's unwanted suitor and thinks he is making a nasty joke ("... with a full brain... you come cheeky and disturb my peace."). Without naming their names, the two uninvited guests explain in coarse words ("black buck, Barbary stallion, rabbit position") that Brabantios daughter, without his consent, secretly, in the middle of the night, took the colored general - Iago's superior - as a husband. The nobleman Roderigo 's oath that the matter is true unsettles Brabantio , he looks for his daughter in the house, but without success, and asks the now trustworthy Roderigo for help. Meanwhile, Iago , wishing to remain unrecognized, makes off. Brabantio is beside himself, accompanied by his servants, he sets out in his nightgown with Roderigo , takes up arms, orders his brother, his relatives and the night watch to be alerted to look for his daughter and her suitor, the general, to whom he cast magic suspected of arrest.

[Scene 2] Iago plays a double game. That same night, he visits Othello in front of his house and reports that Brabantio had reviled his master with such foul language that he – for whom it was a matter of conscience never to plan to murder – wanted to kill the Magnifico. Othello should be careful, because Brabantio is a powerful and influential opponent ("... he burdens you with burdens and trouble, as the law lets him leash."). Othello trusts Iago blindly, he tells him what he has told no one before, namely that he is of high, royal blood. Accompanied by servants of the council , Cassio rushes to bring Othello a most urgent message from the Doge . The Senate is assembled in the middle of the night because of an imminent war ("... three squads have been sent to track you down"). While Othello - "just a word" - enters his house, the ensign and the lieutenant talk about their general's secret wedding, when Brabantio arrives looking for Othello and both groups immediately face each other with their blades drawn blank ("The weapons are gone !"). The betrayed father does not spare with clear words ("... the filthy thief, ... the creature with a soot-black chest ... have abused a child's heart with herbal poison ... and is an adept of forbidden arts."). Brabantio wants to see the general in custody, but an officer of the Doge demands to be heard and brings the request that both be summoned to the Senate immediately because of "urgent matters of state".

[Scene 3] Together with other senators, the Doge discusses the bad news of an attack by the Turkish fleet on Cyprus. A camouflage maneuver in which thirty "Ottomanen" ships temporarily set course for Rhodes is quickly seen through. When Othello and Brabantio arrive, the Doge overlooks the Senate colleague and turns first to Othello , immediately rebuking Brabantio for his omission ("...we missed your advice and assistance today."). Unfazed by the impending war, Brabantio wants to negotiate his "private sorrow" and complains that his daughter has been stolen from him through witchcraft. The Doge does not hesitate for a moment to assure his councilor of every support ("Whoever he may be ... you shall read the blood book of the law to him ... and even if your complaint falls upon our own son."). Without even remotely understanding the dangerous military situation, Brabantio accuses the "black" who has probably been summoned for some state business. The entire Senate is appalled ("We regret that."). The Doge assumes the role of a judge and invites the parties to present their case. He immediately coolly dismisses Brabantio 's accusation of witchcraft as unproven. Othello asks that his wife be heard as a witness in evidence, and the Doge orders her brought ("Fetch Desdemona."), then demands the accused's testimony ("Tell me, Othello"). Othello 's defense reveals a surprising fact, namely that the general was a regular and welcome guest in the house of Brabantios , where he was always asked to tell of his life and deeds that won him the heart of Desdemona . The Doge is immediately convinced ("I think my daughter would also win this story."). Then Desdemona arrives and confirms Othello 's report. The Doge demands that Brabantio give in, which he is doing in contrition, and Othello is immediately ordered to Cyprus ("The matter is urgent and demands haste."). He asks to be allowed to take his young wife with him, which the Doge generously allows and asks Brabantio to give up his reservations about the "Mohren" ("And listen, Signor, if nobleness were a price for fair skin, then it would be your son-in-law instead black pure white."). At the end of the scene and the first act, Roderigo and Iago remain on the stage and discuss the status of their undertakings and the continuation of their plans. Iago first wants to sleep in - in the morning he goes to the field - Roderigo sees himself forced to give up his beloved and therefore wants to "drown". Iago makes fun of his wealthy patron's touch of melancholy: Desdemona is worth no more than a "curb swallow" and suicidal thoughts are a "lack of discipline of will" ("Be a man! Drown cats and puppies!") He pesters Roderigo to keep paying him for his services ("Make some money free.") until he agrees to sell all his land. Alone on stage, Iago does not hide his contempt for the "fool" he is "making a purse" of, and muses aloud on how he will bring misfortune to Othello :

- "I got it! I fathered it!

- This freak is brought into the world by hell and night!".

Act II

The second act deals with Othello 's arrival in Cyprus and has three scenes, the second scene being very short.

[Scene 1] The first scene consists of six takes and opens with a conversation between Montano , the governor of Cyprus, and his nobles. Montano awaits the arrival of Othello ; he is very worried. The governor's subordinates report that a terrible storm is whipping up the sea in an unprecedented way. ("No storm has ever so shaken the fortress.") Even as one worries that the storm itself is threatening the order of the heavens ("...and snuffs out the keepers of the Pole Star.") a messenger brings the news that the Turkish invasion fleet was scattered by the forces of nature ("The war is over!") and reports the arrival of Lieutenant Michael Cassio , whose ship was separated from Othello in the storm . Montano wants to go from his fortress to the harbor to peek for the "brave black man". On their way, they meet Cassio , who reiterates how much Othello is worshiped in Cyprus. A messenger reports the arrival of another ship and the enthusiasm of the people, who also await the arrival of the commander. Montano inquires about Othello 's fiancé, who describes Cassio effusively. ("... a woman who is a model for hymns and eulogies.") A messenger announces the arrival of Iago's ship, with Desdemona and Iago's wife Emilia with him . Cassio greets the "divine Desdemona " with kneeling and a blessing. ("Hail to you, mistress!") With Iago's appearance, the character of the shot suddenly changes into something suggestive. In an exchange of words between Iago and Desdemona , the ensign gives examples of rhymed taunts ("The black one, to be called clever, takes a white one as a color contrast."). After the witty exchange of blows, Iago speaks aside a confession of his cunning and hints to the audience the plan to portray the vain Cassio , who also kisses Desdemona , as in love with the general's bride. ("If it were just enemas, you'd better kiss!") Meanwhile, Othello arrives and greets his fiancée. ("O my brave soldier!") To the loving couple's rejoicing, Iago speaks aside his promise to spoil their happiness. ("But I'll loosen the strings of the music.") As the pair head for the citadel, Iago is ordered to fetch his master's luggage, giving him an opportunity to discuss the progress of his intrigue with Roderigo. He convinces him that Desdemona is in love with Cassio and justifies this by assuming her depraved nature, which soon becomes weary of Othello and then seeks sexual diversion from Cassio , the "slippery rascal". Roderigo doesn't want to believe that, he considers her "pious and chaste", which Iago dismisses with a coarse choice of words. ("Pious farts. ... If she were so pious and chaste, she would never have fallen for the black man.") Roderigo should now ambush the lieutenant at his guard at night and provoke a fight. Iago will then ensure that the dispute develops into riot and mutiny. If Cassio falls out of favor with the general, the way will soon be clear for Roderigo to win over the supposedly unfaithful bride. In the final monologue of the first scene , Iago rejoices in his revenge plan.

[Scene 2] The second scene consists of only one shot. A herald appears and announces the end of the threat of invasion from the Turkish fleet and the impending marriage of Othello and Desdemona . For these reasons, anyone can celebrate. ("All kitchens and cellars are open.")

[Scene 3] The third scene is also divided into six shots. In the beginning, Othello orders Cassio to oversee the guards. In the following shot, Iago makes lewd remarks about Cassio as usual and finds out that he doesn't tolerate alcohol. ("Unfortunately, I have this weak point.") In an interim monologue, Iago decides to take advantage of this. ("If I just put a mug in him...") The long and complex third shot of Scene 3 marks the first crucial turning point in the drama's development. Contrary to his intention, Cassio drank wine. ("By God, they threw me a clean one.") Along with Governor Montano and his nobles , Iago continues to fuel the revelry by intoning drinking songs. When Cassio is completely drunk, he sets out to check on the guards, as per Othello 's orders. Iago now knows how to paint a bad picture of the lieutenant to Montano by accusing him of drunkenness. ("...just look at his vice.") Meanwhile, Roderigo has started an argument with the drunken Cassio and comes running screaming loudly , pursued by Cassio . When Montano tries to stop him, Cassio attacks the governor, gun drawn. As agreed, Roderigo starts shouting loudly. ("Mutiny!") The guard rushes in and the uproar awakens half the town. Othello appears in no time with his sword drawn brightly, the governor is wounded. ("Damn, I'm bleeding!"). The commander is beside himself. ("Who only flinches, dies.") His powerful demeanor immediately forces everyone to calm down. In the attitude of a judge, he questions the parties involved. Cassio unable to defend himself, Montano wounded, Iago replies , setting the matter to the lieutenant's detriment. Othello demotes him ("...never again be my officer.") and orders his ensign, whom he trusts completely to calm the situation. The following shot shows Iago and Cassio in conversation. The humiliated Cassio is an easy target for the ensign's insinuations. He advises him to ask Desdemona for help, so that she should put in a good word for him. ("The advice is good.") In an interim monologue, the fifth shot of the scene, Iago wonders why his intrigue actually works. ("And who can say I'm playing the villain here?") He plans to take advantage of Desdemona 's good nature ("Theology of Hell!") and reveals his next move to the audience, which is to convince Othello that his wife is unfaithful to him and in Cassio was in love. In the final shot, he commands the beaten-up Roderigo to his quarters ("Get away.") He's useless to the ensign now that he's used up all his money. In the final monologue of the second act he announces that he will now use his wife Emilia for his intrigue.

- "That's how it's done!

- Lukewarmness and hesitation only harm the plan."

Act III

[Scene 1] The first scene has four settings. It plays in the early morning in front of Othello 's residence in Cyprus. The first plot sequence shows Cassio in front of Othello's house. He has brought musicians to serenade the new couple. But the choice of music is inappropriate. Othello sends a servant, his fool , to send the uninvited guests away, he doesn't want to hear any musical profanity. In perfect courtesy, the fool pays the musicians not to play and leaves. Would you like to vanish into thin air, please? In the second shot , after the musicians have left, Cassio asks the fool a favor. He gives him a "modest piece of gold" so that he can send Emilia to him. In the third shot, Iago appears . He is on his way to see Othello , who has invited him and other nobles to a meeting. The brief exchange of words between the two indicates that the scene immediately follows the events of the previous night. Having hired the fool , Cassio urges Iago to send his wife to arrange an audience with Desdemona for him. Iago agrees. A fourth shot closes the first scene. In her capacity as chambermaid, Emilia comes out of the house and tells gossip from her mistress' household. Othello spoke to his wife – probably at the table – about his former lieutenant and promised to reinstate him in his old position soon. Cassio nevertheless insists on a conversation with Desdemona . Emilia then invites him into the house.

[Scene 2] This brief scene shows Othello, Iago and some nobles at a military conference at Othello's residence. Iago receives a letter from the general that is addressed to the Senate of Venice and is handed over to a messenger. Then the general wants to inspect the fortifications.

[Scene 3] The first shot of the third - the so-called temptation scene - shows the discreet meeting that Emilia arranged for Cassio to have with Desdemona . They are in a part of the residence where they are largely undisturbed. Desdemona assures Cassio that she will intercede with her husband on his behalf, and Emilia confirms that her husband Iago will also support Cassio 's rehabilitation . Desdemona says she sees the lieutenant's dismissal as a "tactical detachment" -- to calm local anger over the attack on Governor Montano , for example . Ultimately, she vouched for Cassio's concerns and even risked her life to restore his position. In the second shot of the scene, Iago and Othello return from their inspection of the fortifications. When Cassio sees them coming, he slips away, not wanting to meet his general. The ensign notices this first, Othello is not sure, he wants Iago to confirm his impression. When they meet, Desdemona addresses her husband directly to Cassio . She urges him to summon the lieutenant immediately, reminding Othello that it was Cassio who introduced him to her father Brabantio 's company and was his suitor. Increasingly displeased with his wife's behavior, Othello eventually sends her and Emilia away. In the third shot, Iago manages to arouse doubts in his master about his wife's fidelity. He begins with the seemingly harmless question of whether Cassio knew of Othello 's affection for Desdemona . He hints that he has an ulterior motive on the matter, then piques Othello's curiosity. When the general asks his ensign to voice his thoughts, Iago refuses, saying it is the slaves' freedom to keep their thoughts to themselves. Instead, he argues about his master's good reputation, the "sharp-eyed monster" of jealousy and the unfaithfulness of wives. When Othello wants to know if his wife is faithful to him, Iago promises to get to the bottom of the matter. Desdemona enters and reminds Othello to do his duty as host to a feast. Othello complains of a headache and his wife wants to bandage his forehead with her handkerchief. She loses the towel. Emilia takes the lost cloth. She wants to copy it and then give it back to her mistress, she wants to give the copy to her husband. Iago takes it from her and reveals to the audience his plan to have the cloth sent to Cassio unnoticed. In the last shot , Iago deepens his master's distrust of his wife. Othello promotes Iago to his deputy.

[Scene 4] Desdemona enlists the fool to find Cassio after unsuccessfully questioning him. He only responds to her inquiries with puns and counter-questions. Then she casually asks Emilia for her handkerchief, who answers evasively. She calms herself with the thought that her husband was "created out of no meanness". At the beginning of the second shot, Othello asks his wife for the handkerchief he once gave her as a token of his love. When she confesses that she doesn't have it with her, he tells her a story about how he got the cloth. It was a gift from his mother and had the power to enchant the husband in love. It was embroidered by a sibyl in "prophetic madness" and the fabric was dyed in a tincture she extracted from the hearts of maidens.

Act III-V

When Othello witnesses Desdemona and Cassio meeting, Iago finds it easy to arouse Othello 's jealousy (III, 3) and convince him that Desdemona is cheating on him with Cassio . An embroidered handkerchief that Desdemona loses becomes a decisive clue for him : Emilia picks it up; Iago snatches it from her and slips it onto the ignorant Cassio (III, 3). Desdemona 's ignorance of the handkerchief's whereabouts is interpreted by Othello as a lie; when he finally sees the cloth in Cassio 's hands, he is finally convinced of Desdemona 's infidelity (IV, 1). Blind and mad with jealousy, he doesn't believe her protestations. The fear on her face that he will not believe her, Othello interprets as a sign that she is lying to him and strangles her in their marriage bed (V, 2). Although Iago's wife Emilia can still explain the true facts to Othello , she is then murdered by her husband. Iago is arrested and the intrigue is exposed. Realizing his mistake, Othello stabs himself. Ultimately, the judgment of Iago rests with Cassio , who inherits the governorship with Othello 's death.

Literary templates and cultural references

Shakespeare developed the plot after the 7th story of the 3rd decade from the collection Hecatommithi by the Italian Giraldo Cinthio (also Cinzio ), a well-known and popular collection of short stories throughout Europe modeled on Boccacio's Decameron . Cinthio's work was originally published in 1565 and translated into French in 1584. An early English translation has not survived; Whether Shakespeare knew the original, used the translation into French or an English translation that has since disappeared is unclear.

Shakespeare gives the story a new beginning: the events in Venice and the storm off Cyprus are not found in the original. The end of the story is also changed by Shakespeare; in Cinthio's story, the Moor first tries to evade punishment. In the actual plot of the intrigues and intrigues of the wily villain, however, Shakespeare follows the plot of Cinthius relatively exactly, with the exception of occasional tightening and escalation.

Some passages in Shakespeare's Othello are closer to the original Italian than in Gabriel Chappuy's 1584 translation into French. The only named person in Cinthio's tale is Desdemona; other figures include a mischievous ensign, a captain and a moor. The ensign covets Desdemona and seeks revenge because she rejects him. However, in Cinthio's tale, the Moor does not regret killing his wife. He and the standard-bearer flee Venice and are only later killed. Cinthio put the moral into Desdemona's mouth: European women made a mistake when they married the hot-blooded, unpredictable men of other nations.

Shakespeare, on the other hand, does not adhere to the guidelines of Cinthio in the development of the characters and their relationships to one another and in the dramatization of the themes underlying the course of the action such as jealousy, credulity, outsider status or gender roles and conflicts level told.

dating

The exact genesis of the work has not been handed down; From today's perspective, only a period of composition between 1601 at the earliest ( terminus a quo ) and autumn 1604 at the latest ( terminus ad quem ) can be reconstructed with relatively high certainty . In this time frame, most Shakespeare researchers assume that the work was composed rather late, around 1603/4; an earlier draft, around 1601/02, which EAJ Honigmann , for example, considered more likely in the more recent discussion , is not fundamentally ruled out.

The latest possible date of origin comes from a well-known court performance of Othello on the occasion of All Saints' Day on November 1, 1604. There is an entry by Sir Edmund Tilney , the Master of the Revels , in his Accounts Book for the year 1604 about a performance in the great ballroom ( Banqueting House ) of the palace in Whitehall on this day: "By the Kings Maiesties plaiers. Hallamas Day being the first of Nouember. A play in the Banketing house at Whithall called the Moor of Venis. [by] Shaxbred [=Shakespeare]" .

Like other dramas that have survived to be performed at court, the work was probably not written exclusively for this purpose, but was probably performed publicly beforehand. Since the public theaters in London were closed from March 1603 to April 1604, an earlier time of performance and composition would have to be assumed, at the latest in the spring of 1604 or even before March 1603.

The earliest possible point in time of its creation cannot be determined with the same unambiguousness or certainty from external evidence, but is inferred in more recent Shakespeare research, primarily from internal textual references. Various details in the exotic geographic descriptions in Othello point to Philemon Holland's translation of Pliny 's History of the World ( Naturalis historia ) and, in fact, could not have been written without his knowledge. Holland's translation can be dated fairly accurately; the corresponding entry for printing registration in the Stationers' Register was made in 1600; the first print appeared in 1601 with an introductory epistle from Holland, which is dated "Iuniij xij.1601" . The resulting terminus a quo for Othello is largely uncontroversial in contemporary Shakespearean discussion.

The first version of the piece may have been written shortly thereafter; the main evidence for such a supposition is seen in several apparent text echoes from Othello in the first quarto (Q1) of Hamlet , registered by James Roberts in the Stationers' Register on July 26, 1602 and published in 1603. This first edition of Hamlet is considered a so-called bad quarto , based on a transcript by a theatergoer or an actor's memory reconstruction. However, since the earliest printed texts of Othello are now believed to be derived from Shakespeare's own manuscripts, the borrowings can only be explained in one direction as a misremembering by someone who knew both plays; Accordingly, Othello must have been composed in the summer of 1602 at the latest. Various metrical and stylistic-lexical comparative analyzes with other Shakespeare plays also point to the year 1602 on statistical average, but have only limited probative value for principal methodological reasons. Furthermore, in a complex multi-step argumentation, Honigmann tries to draw from the different casting requirements of the first two text versions of Othello , which result from the removal of Desdemona's Willow Song (4.3, 30–50 and 52–54), in connection with the boy's voice breaking, who played this role of reconstructing a date of origin in the winter of 1601/02; His chain of arguments, however, contains unsecured speculative assumptions in several places, which can be invalidated by other hypothetical considerations with the same probability, but cannot be ruled out beyond a doubt.

On the other hand, certain contemporary and theatrical historical circumstances as well as presumed intertextual relationships with other works that only appeared in this period speak for a later dating of the work's origins to 1603/04.

Upon his accession to power in 1603, James I took over the patronage of Shakespeare's troupe. The new king's special interest in the disputes between the Ottoman Empire and the Christian Mediterranean powers is documented. A poem by the king about the defeat of the Turks at the naval battle of Lepanto (1571), first published in 1591, was reprinted in 1603. In this context, Othello may not have been written until 1603, or just before the court performance in late 1604, with the interests and tastes of the new patron in mind. The inclusion of Ben Jonson's masque Blackness in the court entertainment program in the winter of 1604/1605 also points to the fascination that dark-skinned exotic figures exercised on the new queen and her court circles at the time; the Moor as the protagonist in Shakespeare's work would have corresponded to the interest of the public at court at the time in this respect as well. Furthermore, a possible reference to Othello in the first part of Dekker and Middleton 's The Honest Whore , first performed in 1604 and entered in the Stationer's Register on 9 November of that year , can be seen as an indication of the novelty and timeliness of Shakespeare's play in the period , but would rather suggest a time of origin as early as 1603.

In the more recent discussion, similarities between Othello and Shakespeare's comedy Measure for Measure are also discussed, which suggest that they were created in the same period. In both works, Shakespeare uses Giraldo Cinthio's collection of stories Gli Hecatommithi (around 1565) as a model for various plot elements ; Also striking is the use of the name "Angelo" for both the protagonist in Maß für Maß and the "Signor Angelo" from the seaman's messenger report in Othello (1.3, 16). For December 26, 1604, a court performance of measure for measure is documented; an origin of this work between 1603 and 1604 is considered probable. Simultaneous work by Shakespeare on both plays is quite conceivable and would support the assumption that Othello could be Shakespeare's first Jacobean tragedy.

The name "Angelo" also appears in Richard Knolles' historical account, The General History of the Turkes . Knolles, in his detailed account of the confrontations between the Venetians and the Turks before the siege of Nicosia in 1570, mentions a commander of the Venetian forces named "Angelus Sorianus" ("Angelo Soriano"). The messenger's report in Othello apparently agrees with Knolles' statements in various details, especially with regard to the tactics of the Turkish fleet, and indicates that Shakespeare may have been aware of this account of the historical events before Othello was written. Knolles' work, which was dedicated to James I, has an introductory epistle dated "the last of September, 1603" , which would place the end of 1603 as the earliest possible date of Othello 's composition. However, the correspondences are not precise or extensive enough to provide unequivocal proof of the use of Knolles' work as a template for Othello . It is also possible that Shakespeare's The General History was available as a private handwritten manuscript before it was printed in September 1603.

text story

As with all of Shakespeare's other works, an original manuscript of the play has not survived. Othello is one of the most difficult works for modern editors , as there are two early printed versions that are markedly different, with neither the relationship of the two printed versions to Shakespeare's autograph nor their relationship to each other being clearly clarified.

The play was first printed singly in 1622 as a quarto (Q) edition which, according to various editors, may have been based on a copy of Shakespeare's own manuscript. A year later the work was collected and reprinted in the folio edition of 1623 (F). The basis for this print may have been Shakespeare's own copy of a manuscript he had revised. Depending on the edition, both printed versions were simultaneously considered reliable sources for a long time, although the two versions differ significantly from each other.

Although the individual variants are not substantial in many places, they add up to over 1000 places, which corresponds to about a third of the entire text. In addition, (F) contains about 150 rows missing from (Q), while (Q) conversely has about a dozen rows not included in (F).

In the additional lines of the folio edition of 1623 there are a number of quite significant additions; for example Roderigo's account of Desdemona's secret escape (I, i, 122-138) or additions in Othello's text that express his concern for Desdemona's marital fidelity in a differentiated form (e.g. III, iii, 388-395) . Also unlike the first quarto edition, the 1623 folio contains Desdemona's Willow Song (IV, iii, 30-51, 53-55, 58-61) and Emilia's proto-feminist criticism (IV, iii, 84-101) and her condemnation of Othello and Iago (V, ii, 192–200).

These additions in (F) partially take back the pessimistic tone of the piece and draw the role of Desdemona more passive and virtuous or submissive than in (Q). Desdemona's open declaration of her sexuality in the scene before the Senate in the first quarto is deleted in the folio and replaced with less offensive language (e.g. I, iii, 250); likewise, numerous curses or vulgar expressions are omitted from the folio version, probably in response to the Profanity Act of 1606, which banned curses on stage.

In contrast to earlier editors, today's editors assume by and large that neither of the two early printed versions can be directly traced back to a reliable autograph or author-related manuscript, and mostly assume that (F) after a handwritten altered, partially corrected and supplemented, but also partially distorted copy of (Q).

Given the current state of Shakespeare research, none of the various theories published so far about how the two different first printed editions came about provides any ultimately conclusive knowledge about the relationship to Shakespeare's autograph manuscript that explains or takes into account all relevant facts without a doubt. All of the explanatory approaches available so far in this regard are based at crucial points in their respective argumentation on purely hypothetical assumptions that cannot be clearly verified empirically and can be invalidated by contrary, but nevertheless possible or probable assumptions.

Today's Shakespeare researchers, partly for good reasons, abandon the earlier thesis of the existence of a single authoritative original manuscript of Shakespeare in favor of the assumption that Shakespeare himself may have deliberately intended or conceived different versions of the play for different purposes or performance occasions or performance times.

Today's editors therefore usually publish collated editions and decide at their own discretion on a case-by-case basis which of the readings of (Q) or (F) they adopt. The printed version of the Second Quarto , which Augustine Mathewes printed for Richard Hawkins in 1630, is irrelevant to today's discussion of editorial details.

Reception history and work criticism

Although the work, which historically lies somewhere between Hamlet and King Lear , is unanimously counted among Shakespeare's great tragedies by its critics and interpreters , it still occupies a special position. It is true that Shakespeare's other tragedies are not based on a uniform model either; however, since the beginning of the 19th century at the latest, Othello has been accepted primarily because of his otherness in the work criticism. As different as the reviews and interpretations may be in detail, at least in more recent reviews, efforts are made to define and explain the special features of this piece more precisely. Numerous critics see the differentness of the piece less as an award than as a limitation, without seriously denying that Othello undoubtedly belongs to the Great Tragedies .

In contrast, in the first two centuries of his impact, Othello was not so much seen in his special role, but rather as the epitome of Shakespeare's dramatic art. Hardly any other work by Shakespeare enjoyed such great popularity in the epoch of its creation and was performed and celebrated as continuously, mostly in the original text, as Othello .

The play was not only performed repeatedly at the King's Men's two houses , the Globe and the Blackfriars , but was performed more frequently than other plays at the royal court on special occasions. During the Restoration , the work was one of the few plays in Elizabethan theater that was included in the repertoire without any drastic editing or changes. Unlike other works, the play conformed broadly to the neoclassical notions of the three entities , and featured an ideal Restoration-era tragedy hero, the title character being portrayed as an exotic, aristocratic, and military hero. Even critics such as Thomas Rymer , who saw Othello as an example of the obsolete primitive culture of Elizabethan drama, could not help but acknowledge that for most contemporaries the work ranked above all other tragedies on our theaters .

While in the 18th century Othello's role as a romantic lover was in the foreground, in the 19th century the play was increasingly played as a melodrama . Until then, Jago had primarily been seen as a one-dimensional villain and an amoral antagonist to the forces of social order and the code of honor , but his role now became more psychologically differentiated. Othello as the title hero was also received in a different form in the critics and on stage in a multidimensional way, but was embedded largely unbroken in a racist research and theater tradition until the last decades of the 20th century.

Othello was one of the most popular Shakespeare plays in England in the 17th and 18th centuries. For example, Samuel Johnson , one of the most influential literary critics of the 18th century, believed that Othello as a dramatic work spoke for itself and did not need interpretation by literary critics. Above all, he praised the drawing of the characters and praised the varied and exciting storyline; he considered the improbability of Jago's intrigues, which was sometimes objected to by other critics, to be artistically skillful or natural ( artfully natural ).

The positive reception and appreciation of the work by the leading representatives of literary criticism and interpretation remained unbroken well into the 20th century. For example, Andrew Cecil Bradley , whose character criticism approach has had a significant influence on Shakespeare research for a long time since the beginning of the 20th century, emphasized the tragic greatness of the drama's title character. At the same time, in his " lecture " on "Othello", he took the view that he was " by far the most romantic figure among Shakespeare's heroes ". According to Bradley, Othello doesn't kill Desdemona because of his jealousy; rather, the almost superhuman cunning of Jago leads him, in Bradley's view, to a conviction that anyone who, like Othello, believes in honesty and sincerity (“ honesty ”) would have won.

However, the admiration of the public was not always so great: the French public around 1800 vehemently rejected the piece, although the translator Jean-François Ducis had defused it during the transmission and had written an optional happy ending . Romanticism , on the other hand, found access to the tragic piece, as corresponding settings and paintings (e.g. by Eugène Delacroix , Alexandre-Marie Colin , Robert Alexander Hillingford ) show.

In the further history of reception of the work, the ways of criticism and the theater parted. On stage, the work has retained its popularity as a drama with both theater makers and audiences over time. Above all, the intensity of the emotional effect of the piece is considered to be hard to surpass, both in terms of sympathy or pity for the main characters Othello and Desdemona and in terms of the terrible fascination of the figure of Jago. The passions and actions portrayed on stage are extreme from the perspective of the theatergoers, but they do not reduce the dismay or the recognizable familiarity with basic human phenomena such as jealousy, claims of possession or dominance in love or the dangers of absolute trust or acceptance and alienation in a society. Jago's machinations can also be understood by the viewers again and again as forms of everyday evil.

The perfect dramaturgy of the single-track plot, which is manageable despite the numerous twists and turns, ensures that the action on stage is experienced as exciting. As in other plays by Shakespeare, the audience is taken into their confidence and usually knows more than the dramatic characters themselves. Iago 's monologues serve to inform the audience about his plans. The information strategy pursued by Shakespeare in this work, however, does not give the viewer, as in many of his comedies, a certain know-it-all or foreknowledge, since Iago is a little trustworthy informant. The spectator becomes aware of his plans and intentions, but has to deal critically or questioningly with his motives and his characterization of the other dramatic figures again and again.

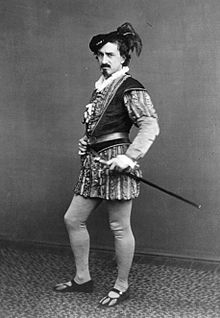

With the extensive part Iago, Othello is one of the few Shakespeare dramas with two male roles of equal weight; numerous famous actors of the English language theater from Thomas Betterton , David Garrick or Edmund Kean to Edwin Booth , Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud or Paul Scofield , to name but a few, have played one of the two roles or often both roles.

In the more recent literary or literary-critical reception and discussion of the work, there have been various attempts since the late 20th century under the influence of postcolonial criticism, especially since the 1980s, to break through the racist tradition of interpreting the work, which subsequently led to completely different reinterpretations of the work. In more recent stage performances, all roles in the play have been filled with black actors in a similar direction in order to question the black-white binary, for example in the productions by Charles Marowitz in 1972 and by H. Scott in 1989/90. In the Hamburg production of Peter Zadek 's play in 1976, the role of Othello was played as a grotesque "picture book Moor" in order to point out the strategies of stereotyping in the performance itself.

Likewise, in various more recent interpretations and reviews of the play, attention is drawn to the depiction of gender roles and conflicts, again with completely different interpretations. On the one hand Desdemona's behavior is interpreted in several respects by Dympna Callaghan in her analysis as an emancipatory transgression of the traditional gender boundaries of the Elizabethan period. Thus, against her father's wishes, Desdemona allied herself with Othello, the man of her choice, to whose courtship she herself initiated. In addition, her desire is directed at an outsider in society; Desdemona proves to be a self-confident, daughterly advocate of female autonomy in choosing a partner.

In the feminist -oriented recent literary criticism, on the other hand, under the influence of gender studies , the misogynistic implications of a dualistic image of women in Shakespeare's work are emphasized, in which Desdemona's sensuality implied the possible change from saint to whore (from saint to whore) from the beginning. In this context, Iago's characterization and condemnation of Desdemona as general's general refers to the cultural fear of the collapse of traditional gender differences and thus to the need to finally silence Desdemona; In Shakespeare's play, Desdemona's violation of the commandments of female chastity and obedience, like Emilia's, must be punished ruthlessly as an attack on the very foundations of society.

Since the end of the 20th century, this changed orientation in the more recent approaches to interpretation and analysis on the part of postcolonialism and feminism has also led to a shift in emphasis in the more recent productions of the play. For example, in today's productions Desdemona is given a more active role than the text originally suggested. Lines in which Desdemona appears to be particularly weak or submissive according to today's understanding are faded out; more modern stagings of Othello also preferably begin with Desdemona's flight from her father's house to Othello. In a 1997/98 National Theater performance directed by Sam Mendes , Desdemona even responds by physically attacking Othello when he accuses her of adultery in 4.1 by banging her fists on his chest.

In addition, modern productions often contrast the sexually fulfilling marriage of Othello and Desdemona with the unfulfilled, frustrated relationship between Iago and Emilia. In addition, the role of Bianca is upgraded and no longer seen as a purely comical and hardly necessary accessory.

While in the 17th and 18th centuries a number of actors were reluctant to take on the role of the malicious schemer Iago, today's dark-skinned actors often refuse to play the role of Othello to avoid being perceived as gullible and driven by animalistic tendencies.

adaptations

film adaptations

Othello has been filmed several times. A first silent film adaptation appeared in Germany in 1907, directed by Franz Porten ; an Italian film adaptation, directed by Mario Caserini , followed that same year, and an American production, directed by William V. Ranous, starring Hector Dion as Iago and Paul Panzer as Cassio the following year. In 1918 another early German film adaptation was released, directed by Max Mack , which was followed in 1922 by the German-produced film version , directed by Dimitri Buchowetzki and starring Emil Jannings in the role of Othello and Werner Krausss in the role of Iago.

One of the outstanding film adaptations of the second half of the 20th century is the version from 1952 with Orson Welles as Othello, which in the original version as a black-and-white film brought out the light/dark imagery of the work in a particularly successful way. Welles' film, which received the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 1952, impressed not only with the portrayal of the characters, but above all with its impressive pictures and interesting camera work. He begins with a funeral procession on the ramparts of the Castle of Cyprus, which could follow the end of Shakespeare's drama, and then, with an off -screen voice, steers back to the beginning of the tragedy.

After a film adaptation by the Soviet director Sergei Iossifowitsch Jutkewitsch in 1955, a film adaptation was made in 1965, directed by Stuart Burge, with Laurence Olivier in the title role. This version was based on John Dexter 's production of Othello at the Royal National Theater in London in 1964. The set design and costumes were retained unchanged in the film version; numerous close-ups attempted to increase the intensity of the effect on the viewers.

As part of a series of Shakespeare adaptations by the British Broadcasting Corporation , the drama was filmed in 1981, directed by Jonathan Miller and starring Anthony Hopkins as Othello. Despite the star cast and the acting performances of the actors and actresses, however, the static camera work and the unfortunate choice of costumes in this BBC television adaptation were criticized in various film reviews.

Immediately after the end of apartheid in South Africa, a 1989 film adaptation of the 1988 production at the Market Theater in Johannesburg was made, directed by Janet Suzman .

Based on a Royal Shakespeare Company Production , Trevor Nunn produced a 1990 film version starring Willard White as Othello, Imogen Stubbs as Desdemona and Ian McKellen as Iago. In this version, Nunn set the plot of the drama to the American Civil War .

Based on the screenplay based on Shakespeare and directed by Oliver Parker , an internationally commercialized British-American film version of Othello was made in 1995 with the well-known black American actor Laurence Fishburne in the title role and the well-known British actor and Shakespearean actor Kenneth Branagh in the role des Iago and the Swiss-French theater and film actress Irène Jacob as Desdemona. In this film adaptation with short camera angles and a fast pace of play, a lot has been changed and almost half of the original text has been deleted. After Othello removes his mask, Black Othello is revealed to the audience; this setting gives the impression that everyone is wearing masks except for him and Iago himself. As a new visual element, Parker also uses chess pieces, with the help of which Iago first presents his intriguing plan in order to ultimately sink them. Othello's courtship of Desdemona and the consummation of the marriage are shown in flashbacks ; at the same time, to implement Othello's statements, Parker fades in scenes of an erotic encounter between Desdemona and Cassio in 4.1.42, whereby their naked bodies are shown. At the end of Parker's film adaptation, two corpses, possibly Othello's and Desdemona's, each wrapped in a white cloth, are handed over separately from the ship out of the canal. Parker's film adaptation of Othello received mixed reactions from critics.

settings

One of the best-known musical adaptations of Shakespeare's tragedy is Giuseppe Verdi's opera Otello , which premiered on February 5, 1882 at La Scala in Milan with the libretto by Arrigo Boito . Verdi's opera, which only begins with the second act of Shakespeare's drama, fades out the plot of the previous story and focuses on the events in Cyprus. The emergence of the love affair between Othello and Desdemona is presented in Boito's version of the text as a flashback in the first love duet at the end of 1.3; Desdemona's self-confident demeanor towards the Senate and her father is omitted, as is Brabantio's warning to Otello about a woman who deceives her father and could therefore also deceive her husband (I.3.293 f.). In contrast to Shakespeare's drama, in which Desdemona begins as In keeping with the spirit of the 19th century, Boito presents a humble, completely devoted Desdemona in his version, who, especially in her night prayer «Ave Maria», seeks protection and support from the Holy Virgin Mary as the protector of the poor and weak. Boito stylizes Othello into the impeccable ideal of a heroic general and loving husband; Iago, on the other hand, becomes the incarnation of evil and destructiveness.

Unlike Verdi's setting, the libretto of Gioachino Rossini's dramma per musica Othello, or The Moor of Venice ( Otello ossia Il moro di Venezia) , written by Francesco Maria Berio in 1816, does not derive solely from the original version of Shakespeare's tragedy. The redesign of the material by Jean-François Ducis and the editing by Giovanni Carlo Baron Cosenza are used here as templates.

text editions

- total expenses

- John Jowett, William Montgomery, Gary Taylor and Stanley Wells (eds.): The Oxford Shakespeare. The Complete Works. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-0-199-267-187

- Jonathan Bate , Eric Rasmussen (eds.): William Shakespeare Complete Works. The RSC Shakespeare , Macmillan Publishers 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-20095-1

English

- EAJ Honigmann (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1997, ISBN 978-1-903436-45-5

- Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53517-5

- Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-953587-3

- Dieter Hamblock (ed.): William Shakespeare, Othello . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-019882-7 .

German

- Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-86057-549-X

- Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-423-12482-9

literature

- Anthony Gerard Barthelemy: Critical Essays on Shakespeare's Othello . Maxwell Macmillan, New York 1994.

- Anthony Gerard Barthelemy: Black Face Maligned Race. The Representation of Blacks in English Drama from Shakespeare to Southerne . Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge / London 1987.

- Christine Brückner : If you had talked, Desdemona . Impudent Speeches of Impudent Women . Ullstein, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-550-06780-1 .

- Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 312–316.

- Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, ISBN 3-89709-383-9 .

- Hans-Dieter Gelfert : Othello . In: Hans-Dieter Gelfert: William Shakespeare in his time . Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 349–354.

- GK Hunter: Dramatic Identities and Cultural Tradition. Studies in Shakespeare and his contemporaries . Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 1978.

- Stewart Martin: Othello. William Shakespeare. Guides . Letts Educational, London 2004, ISBN 1-84315-322-X .

- Margaret Leal Mikesell (ed.): Othello. An annotated bibliography . Garland, New York 1990, ISBN 0-8240-2749-3 .

- Beate Neumeier : The Tragedy of Othello the Moor of Venice . In: Interpretations – Shakespeare's Plays . Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , pp. 288-316.

- Sabine Schulting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 537–546.

- Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. 2015 edition, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 344–357.

- Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, corrected reprint 1997, ISBN 978-0-393316674 , pp. 476–491.

web links

- Othello in Project Gutenberg-DE

- Othello in full text with search function, summary (English)

- Spark Notes on Othello

- Giraldi Cinthio: Hecatommithi (1565). (PDF; 31 kB; English)

- MIT, Arden version. English text edition of Othello

- Zeno-Org = Schlegel-Tieck-Version German text edition Othello

- British Library Shakespeare in Quartos. Othello 1st Quarto 1622.

itemizations

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 1, 11.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 1, 66.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 1, 100.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 1, 89, 112, 117.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 1, 159: Enter Brabantio in his night-gown. (stage direction). See Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (eds.): William Shakespeare: Hamlet. The Texts of 1603 and 1623. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 2, Bloomsbury, London 2006, Hamlet Q1, 11, 57: Enter the Ghost in his night-gown. (stage direction)

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 2, 15-17.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 2, 46f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 2, 82. See Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2014, Act I, 1, 85f: "In torture, let the misused weapons fall from your bloody hands."

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 2, 62-81.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 51.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 65-70.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 73.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Akt I, 3, 121. The name is mentioned here for the first time.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, act I, 3, 127. Then the name of the hero is mentioned for the first time.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 170.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 272f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 284-286.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, act 1, 3, 330f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 371.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 3, 391f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 1-299; 2, 1-10; 3, 1-368.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 1-42: Montano and the nobles; 43-82: arrival of Cassio; 83-95 and 96-175: appearance of Desdemona and Emilia as well as Iago and Roderigo; 176-206: arrival of Othello; 207-271: Iago and Roderigo remain on stage; 272-299: Iago's final monologue.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 1-42.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 6. Cf.: Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Hamlet . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 1, 9: "'Tis bitter cold, ...".

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 15. Cf.: Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Hamlet. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act I, 1, 40: "... when yond same star that's westward from the pole, ...".

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 20. A contemporary theatergoer will be reminded of the English victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 48. While Othello's skin color was repeatedly negatively connoted in the first act, the governor of Cyprus emphasized the general's positive qualities.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 43f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 61-65: "... a maid that paragons description and wild fame" .

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 73.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 85. Cf.: Ernst AJ Honigmann (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Arden Shakespeare . Third Series. Bloomsbury, London 1997, p. 107. Here, Honigmann points out that this passage is similar to the prayer of the rosary: "Hail Mary, full of grace ...". Analogies to the Salve Regina (English: "Hail, holy Queen, Mother of Mercy" ) and Ps 139.5 EU ( King James Version : "Thou hast beset me behind and before, and laid thine hand upon me. ") are also there obvious.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 100-102. However, Cassio's behavior prompts him to kiss Emilia as a greeting.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 131f. See: Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare. Much Ado About Nothing . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2012, Act II, 1, 52f: "Isn't that insulting for a woman to let a piece of dirt rule her?"

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 164-172.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 176.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 194.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 214-238.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 1, 241f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 2, 7f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 1-10: Othello, Desdemona and Cassio; 11-56: Cassio and Iago with a monologue by Iago (43-56); : 56-247 all; 248-316: Iago and Cassio; 317-343 Iago's monologue; 344-362 Iago and Roderigo with Iago's final monologue (363-368).

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 1.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 35f.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): W illiam Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 43.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 56-247.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 59.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 63-67.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 113.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 146.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 153.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 163.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 238.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 309.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, act II, 3, 317. See Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Richard III. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2009, I, 2, 232: "Was a woman ever recruited in such a way?"

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 331.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 362.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 2, 363-368.

- ↑ Frank Günther (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . Bilingual edition. dtv, Munich 2010, Act II, 3, 370.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 1, 1-20.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 1, 20-29.

- ↑ Cf.: the so-called "double time scheme" - Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, pp. 33-36.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 1, 30-41.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 1, 42-56.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 2, 1-8.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Commentary on Act III, Scene 3, pp. 301-306.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 3, 1-33.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 3, 35-41.

- ↑ This scene is one of the main reasons for Honigmann in his character analysis of Othello to assume that the hero has impaired vision [Ernst AJ Honigmann (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury, London 1997, pp. 14-26, especially pp. 17f].

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 3, 42-90.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, act III, scene 3, 106f: By heaven, he makes my echo as if a monster were in his thoughts.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 3, 135f.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 4, 26f.

- ↑ Balz Engler (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. English-German study edition. Stauffenberg Verlag, Tübingen 2004, Act III, Scene 4, 69-75.

- ↑ Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 347. See also Sabine Schülting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 538.

- ↑ Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. 2015 edition, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 347. See also Sabine Schülting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 538f. See also Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 312

- ↑ Cf. Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, pp. 399-403, and Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, pp. 1 f. See also EAJ Honigmann. (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1997, pp. 344-350. Honigmann, on the other hand, concedes that he cannot definitively prove an early dating ( "[...] some steps in this reasoning cannot be proved" , p. 350), but sees no compelling reasons for a later dating ( "[...] no compelling evidence for a later date” , p. 350). Bate and Rasmussen, on the other hand, assume 1604 as the date of origin, but refer to earlier dates by other scholars. See William Shakespeare Complete Works . The RSC Shakespeare. Edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen. McMillan 2007, ISBN 978-0-230-20095-1 , p. 2085. Sabine Schülting also assumes 1603/04 as the year of origin. See Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 537.

- ↑ quoted from Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, p. 1. See also the source citation in Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, p. 399. The earlier doubts about the authenticity of this manuscript, discovered only in the 19th century, from the court documents of e.g. B. Samuel Tannenbaum or Charles Hamilton are now almost without exception rejected. See Sander (ibid., p. 1) and Neill (ibid., p. 399).

- ↑ Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, p. 399. On performance practice, see also Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbuch. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 448. However, it cannot be ruled out with complete certainty that the work was still new at the time of this court performance. This is assumed, for example, by Wells and Taylor; see Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion . Oxford 1987, p. 93.

- ↑ Cf. William Shakespeare: Othello . The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford Worlds Classics. Edited by Michael Neill. 2006, p. 399. See also William Shakespeare: Othello . The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Edited by EAJ Honigmann. 1997, p. 344 f. For the theoretically conceivable objection that a version of Othello that was written before 1601 could have been subsequently changed, there is no evidence whatsoever from the history of the text and from the scientific edition.

- ↑ However, Wells and Taylor consider these text echoes to be accidental. See Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion . Oxford 1987, p. 126.

- ↑ Cf. EAJ Honigmann. (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1997, pp. 344-350. Critical to Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, pp. 401-403. In terms of methodology, the comparative statistical analyzes have only limited meaningfulness, since the proportion of verse and prose passages in the works used differs (cf. Neill, ibid.). See also Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, pp. 1 f.

- ↑ Cf. on James I Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbuch taking full patronage of the entire theater industry and thus also of Shakespeare's acting troupe. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 102. See also Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, p. 399.

- ↑ Cf. Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, p. 399 f. Jonson's masque, an African fantasy , was created at the special request of Queen Anne (cf. ibid.).

- ↑ Cf. Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, p. 400. However, the relevant passage "more savage than a barbarous Moor" from The Honest Whore (I.1.37) is not specific enough to be able to prove with certainty a clear reference to Othello . See Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, p.2.

- ↑ Cf. Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, pp. 400 f. See also Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, p.2.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 3447f. and Sabine Schülting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 537f. See also Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, corrected reprint 1997, ISBN 978-0-393316674 , pp. 476f. and EAJ Honigmann (eds.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1997, ISBN 978-1-903436-45-5 , pp. 351f.

- ↑ Cf. Sabine Schülting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 537f. On the differences in text and meaning, cf. the analyzes and interpretations by EAJ Honigmann, some of which are rather hypothetical. (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1997, ISBN 978-1-903436-45-5 , pp. 351–354, and Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53517-5 , pp. 203-215.

- ^ See Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide . Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. 2015 edition, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 348. See also Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, corrected reprint 1997, ISBN 978-0-393316674 , pp. 477f.

- ↑ See in detail, for example, Michael Neill (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-953587-3 , pp. 405–433. See also Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, p. 141.

- ↑ Cf. on the different hypothetical theories about the formation of Q and F as well as their relationship and differences, the detailed presentation by EAJ Honigmann. (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1997, ISBN 978-1-903436-45-5 , pp. 351–367, and Norman Sanders (ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello . New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53517-5 , pp. 203-217. On modern editorial practice, see, for example, the remarks by Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, corrected new edition 1997, ISBN 978-0-393316674 , pp. 476–478, or Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide . Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. 2015 edition, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 348. See also Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, p. 138 ff.

- ↑ Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 347f. See also Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 314f.

- ↑ Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 349. See also Beate Neumeier : The Tragedy of Othello the Moor of Venice . In: Interpretations – Shakespeare's Plays . Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , pp. 289f. Likewise Sabine Schülting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 543. Notwithstanding this concession, Rymer's early commentary on the work was tantamount to a devastating scathing: still clearly committed to the classicist standard postulate of his time, he understood the fable des Dramas as lifeless and "highly improbable lies" resulting in fundamental deficiencies in plot and character drawing. There is no poetic justice at all; the innocent Desdemona finally loses her life because of the vanity of a lost handkerchief. The union of the black Othello with the white Desdemona also violated the dramatic principle of probability because of the incompatibility of the races; moreover, a black would never have been appointed commander-in-chief of the Venetian army. The figure of Iago is equally unbearable and completely lifeless. See in detail Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, pp. 89–92.

- ↑ Cf. Sabine Schülting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 543f. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 349f. See also Beate Neumeier in detail : The Tragedy of Othello the Moor of Venice . In: Interpretations – Shakespeare's Plays . Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , pp. 289ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 349f.

- ^ Cf. on this Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, pp. 95-97, and Horst Priessnitz: "Haply, For I Am Black ...": Political Aspects in the "Othello" Arrangements by Donald Howard, Paul Ableman and Charles Marowitz . In: Horst Priessnitz (ed.): Anglo-American Shakespeare adaptations of the 20th century. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1980, ISBN 3-534-07879-9 , p. 307.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 350f. See also Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-280614-7 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 314f. See also the details of the performance and stage history of the work in the introduction by EAJ Honigmann in: EAJ Honigmann. (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Othello. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 1997, ISBN 978-1-903436-45-5 , pp. 90–102.

- ↑ Cf. Sabine Schülting: Othello, the Moor of Venice . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 544f. See also in detail Beate Neumeier : The Tragedy of Othello the Moor of Venice . In: Interpretations – Shakespeare's Plays . Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , pp. 289ff.

- ↑ See in detail Beate Neumeier : The Tragedy of Othello the Moor of Venice . In: Interpretations – Shakespeare's Plays . Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 978-3-15-017513-2 , pp. 296-307.

- ↑ Cf. Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, p. 119. The alleged racism of Shakespeare's work is even reflected in the new translations of Shakespeare's attribution of Othello as Moor of Venice . The literal translation as "Moor of Venice" has led to lengthy discussions about the implicit racism of this designation and the search for other transmission options such as "dark-skinned person" or "exotic stranger" or similar more up to a complete deletion of the passages perceived as offensive led, in which this term appears in the original text. For example, in his new translation of Othello , against this background of discussion - which he himself satirized elsewhere - Frank Günther decided to consciously dispense with the original subtitle of Moor of Venice in his German translation of the work title, despite his own uneasiness about this step. so as not to further fuel the existing, escalating and, from his point of view, little useful discussion. See the chapter Othello, the Poc of Venice. In: Frank Günter: Our Shakespeare. Insights into alien-related times. dtv, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-423-14470-4 , pp. 94–118.

- ↑ Cf. Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, p. 128. See also the respective information in the Internet Movie Database and in the list of filmed works by William Shakespeare .

- ↑ Cf. Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, p. 128 f.

- ↑ Cf. Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, p. 129 f.

- ↑ Cf. Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, p. 130 f.

- ↑ Cf. on the differences between Verdi's opera and Shakespeare's original in more detail Sonja Fielitz : Othello . Kamp, Bochum 2004, pp. 126–128.