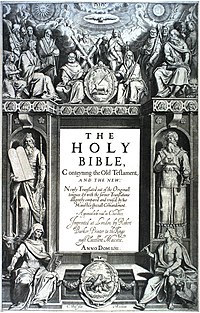

King James Bible

The King James Bible (KJB; English King James Version (KJV), King James Bible (KJB) and Authorized Version (AV)) is an English translation of the Bible . It was created for the Anglican Church on behalf of King James I of England . Hence the name King James Bible, because King James is the English-language form of King Jacob . It has been the most influential English language translation of the Bible since it was first published in 1611 . In the following years seven editions were published; the one created in 1769 is the one mainly used today.

origin

The KJB emerged as a reaction to the Protestant teaching that it is not the interpretation by church leaders but the Bible itself that is the basis of Christian teaching (“ Sola scriptura ”). In order to give every Christian access to scripture, the translation of the Bible into the respective vernacular became necessary as a result of the Reformation . Already in the early Middle Ages - before the Catholic Church began to only allow the Latin Bible - there were translations of parts of the Bible into Anglo-Saxon . After that, in the High Middle Ages, ( Middle English ) translations of biblical books were produced again, which were revised by John Wyclif from around 1380 and compiled into a full Bible. The first translation of the Bible into (early) New English , the Tyndale Bible translation made by the evangelical theologian William Tyndale , was made from 1525–1534, about 80 years before the KJB appeared. Even though King Henry VIII, according to Reformation custom, granted the king the supreme power of the Church in England in 1534, William Tyndale had to pay for his translation and publication work with his life two years later. His translation, revised and supplemented several times by himself and by his successors, was officially banned, but ultimately formed the basis for the development of the King James Bible of 1611.

The English Church initially used the officially sanctioned " Bishops' Bible ", which, however, was hardly used by the population. More popular was the " Geneva Bible ", which was based on the Tyndale translation in Geneva under the direct successor of the reformer John Calvin for his English followers. Their footnotes, however, represented a Calvinist puritanism that King Jacob was too radical. In particular, the decidedly anti-royalist tone of the Geneva Bible was unbearable for King James I, because he was a staunch advocate of God's grace . The translators of the Geneva Bible had translated the word king with tyrant around four hundred times - the word tyrant does not appear once in the KJB . For his project, King Jacob convened a synod at Hampton Court Palace in 1604 , where he proposed a new translation to replace the popular Geneva Bible. The translators were asked to follow the teaching of the Anglican Church and to refrain from polemical footnotes. Among other things, he demanded:

- to follow the “Bishop's Bible” as far as possible and to follow everyday usage when referring to the names of biblical persons;

- to follow traditional ecclesiastical practice and not replace the word church (“Kirche”) with congregation (“congregation”);

- To use footnotes only to explain words;

- to find the text of the translation in agreement with all translators;

- in the event of disagreement, to consult other scholars.

The translation was done by 47 scholars , divided into a number of working groups. Each group worked on a Bible passage that was then harmonized with one another. The working groups were:

- First Westminster Company ( Genesis to Second Book of Kings ): Lancelot Andrewes, John Overall, Hadrian Saravia, Richard Clarke, John Laifield, Robert Tighe, Francis Burleigh, Geoffry King, Richard Thompson, William Bedwell.

- First Cambridge Company ( 1 Chronicles to the Song of Songs ): Edward Lively, John Richardson, Lawrence Chaderton, Francis Dillingham, Roger Andrews, Thomas Harrison, Robert Spaulding, Andrew Bing.

- First Oxford Company ( Isaiah to Malachi ): John Harding, John Reynolds, Thomas Holland, Richard Kilby, Miles Smith, Richard Brett, Daniel Fairclough.

- Second Oxford Company (The Four Gospels , Acts, and Revelation of John ): Thomas Ravis, George Abbot, Richard Eedes, Giles Tomson, Henry Savile , John Peryn, Ralph Ravens, John Harmar.

- Second Westminster Company (the New Testament Letters ): William Barlow, John Spencer, Roger Fenton, Ralph Hutchinson, William Dakins, Michael Rabbet, Thomas Sanderson.

- Second Cambridge Company (The Apocrypha or Deuterocanonical Books ): John Duport, William Brainthwaite, Jeremiah Radcliffe, Samuel Ward, Andrew Downes, John Bois , John Ward, John Aglionby, Leonard Hutten, Thomas Bilson, Richard Bancroft.

Literary quality

Both the prose and poetry of the KJB are traditionally valued; however, the change in the English language since its publication makes the text archaic to the modern reader. Common linguistic anachronisms are the words thou , thee , thine , thy , thyself (2nd person singular du, dich, dein; modern English uses you , your , yours , yourself ).

A linguistic peculiarity is the use of the possessive genitive form, e.g. B. his (the animal's) blood, which in Middle English would be his blood , in New English its blood . William Tyndale's slightly older translation, which was created when the transition from Middle English to New English was in full swing, circumvented this problem by using the form the blood thereof , which is possible in both languages. The KJB followed this form of expression, which has now been perceived as "biblical".

Sometimes neither his nor its were used, but the nouns were assigned to a gender, as in German, so that the word her was sometimes allowed: And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind (Revelation 6:13).

The translators of the KJB did not hesitate to use expressions that were perceived as offensive today if the literal translation required it (1 Samuel 25:22: So and more also do God unto the enemies of David, if I leave of all that pertain to him by the morning light any that pisseth against the wall ). Almost all of the newer English Bibles (and most of the German ones too) use euphemisms in such cases , which correspond only imprecisely to the original text. The miniature Bible by Franz Eugen Schlachter from 1905 and the revision from 1951 as well as the Zurich Bible also had this translation.

The translators used the Masoretic text for the Old and the Textus receptus published by Erasmus of Rotterdam for the New Testament . They managed a translation that was very close to the text; Words that were not present in the original text but only implied were indicated by square brackets or italics, in the early editions by antiqua within the Gothic body text. In the New Testament the translation is hardly objectionable. In the Old Testament, however, many forms of translation show that the translators only incompletely understood the Hebrew vocabulary and the structures of the Hebrew grammar - Christian Hebrew studies was still in its infancy.

expenditure

New editions of the KJB differ from the first edition in the following points:

- The Apocrypha and Deuterocanonical books originally included in the KJB are mostly missing. This omission follows the teaching of the Church of England, which does not consider those books to be divinely inspired.

- The first edition contained a number of text alternatives if there is no consensus on the reading of the original text. These variants are usually no longer included; only the American Cornerstone UltraThin Reference Bible , published by Broadman and Holman, still contains it today.

- The first edition had annotations when a section of text is a quote from someone else or is directly related. These notes are seldom included in modern editions.

- The original dedication of the translation to King James I can still be found in British editions today, and more rarely in other editions.

- An introduction by the translators who justify their work and explain their intentions and methods is missing in almost all editions today.

- The extensive appendices to the first edition, e.g. B. via calendar calculation, are missing in the modern editions.

- The first edition print set used “v” for the lowercase “u” and “v” at the beginning of the word, and “u” for “u” and “v” in the word. The "s" inside the word was represented by "ſ". The "j" only appeared after "i" or as the last letter in Roman numerals . Punctuation marks were different from today. The article “the” was replaced by “y e ”, which represented the Middle English letter þ (“thorn”) with a “y”. There is also “ã” for the letter combinations “an” or “am” (a kind of shorthand) in order to be able to print more closely.

Modern editions are based on the text published by Oxford University in 1769, which marked missing words in the original using italics and corrected some typographical errors and anachronistic expressions at the time. On the other hand, expressions that only became uncommon after 1769 can also be found in the latest editions of the KJB.

The original text is available in an edition by Thomas Nelson ( ISBN 0-517-36748-3 ) and an annotated edition by Hendrickson Publishers ( ISBN 1-56563-160-9 ).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (commonly known as " Mormons ") published an edition that includes footnotes, changes to the Bible text by the church founder, Joseph Smith, and references to the Book of Mormon and its other scriptures, as well as an edition of the Bible in one volume with the Book of Mormon and the other scriptures in this church.

Wicked Bible

An edition from 1631 contained a serious misprint in the Ten Commandments: instead of You should not commit adultery , it said you should commit adultery (Thou shalt commit adultery). Charles I , who had ordered an edition of 1000 copies from the respected royal printers Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, was furious and had the copies that had already been issued (the error only discovered months after printing) collected and burned. Only a few copies escaped and as sin Bible known (Wicked Bible) and collectors' items. A well-preserved example sold for $ 27,000 at auction in 1996. The printers were given a very heavy fine of £ 300 and lost their license.

reception

Although the KJB was supposed to replace the " Bishops' Bible " as the official Bible of the Anglican Church, no explicit edict is known. Nevertheless, the KJB prevailed in worship.

The Geneva Bible was long preferred by broad sections of the population; it remained in use until the English Civil War . Thereafter, its use was considered politically problematic as it represented the bygone era of Puritanism. The KJB achieved widespread use and popularity.

At the end of the 19th century, the King James Version got competition for the first time. In 1881 the New Testament appeared and in 1885 the so-called Revised Version of the Old Testament . This is largely based in the New Testament on the Greek text of the edition The New Testament in the Original Greek by Westcott and Hort. The American Standard version , which appeared in 1900 and 1901, is very similar, but not identical .

Modern translations of the Bible sometimes use source texts based on new manuscript finds. This results in some differences in content between the KJB and more recent translations; These are viewed by a minority of conservative Christians, especially in the USA, as a falsification of the "true" Bible and are rejected. In the Anglo-Saxon-speaking area there are certain circles under the name King-James-Only-Movement , which only recognize the King-James-Bible. Some of these followers only accept this translation as the inspired word of God. However, the majority of American conservative Protestants today use the "New International Version" of the Bible, a relatively free modern translation. Furthermore, the " New King James Version " (NKJV, first edition 1982) is very popular there. It has retained the sentence order of the KJB, which is sometimes unfamiliar, only replaces words that are not in use today with modern ones and is one of the few current NT Bible translations based on the text receptus has been revised.

The literary quality and linguistic influence of the King James Bible has led to the fact that in Bahaitum the translations of the writings of Baha'u'llah into English since Shoghi Effendi have been based on the style of the King James Bible. This translation of a hidden word may serve as an example :

“O SON OF MAN! I loved thy creation, hence I created thee. Wherefore, do thou love Me, that I may name your name and fill your soul with the spirit of life. "

copyright

In the UK , the KJB is under permanent state copyright ; this essentially in order to put it under permanent protection as an official document of the state church . British editions therefore require a license from the government or the universities of Oxford or Cambridge which own the printing rights. Annotated Bibles do not come under this protection. In all other countries the KJB is in the public domain , so anyone can use it in any way.

literature

- David Crystal : Begat: The King James Bible and the English Language . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2010, ISBN 0-19-958585-7 .

Web links

- Read King James Bible online die-bibel.de

- Blue Letter Bible : King James Version online with Strong numbering system and basic texts

- Tyndale Translation - First print of the New Testament of the English Protestant martyr William Tyndale from 1526

- King James Bible - Text of the translation at Project Gutenberg

- King James Version as audio bible (audioteaching.org)

- Complete concordances based on the original English text. Edited by Prof. Valerio Di Stefano

Individual evidence

- ^ The Guardian: The wicked bible

- ↑ Fowler Bible Collection: The wicked bible ( Memento of the original from July 14, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Frank Lewis: Unveiling the Hidden Words, by Diana Malouf: An Extended Review . In: Bahá'í Studies Review . tape 8 , 1998 ( bahai-library.com ).

- ^ Dominic Brookshaw: Unveiling the Hidden Words, by Diana Malouf: Commentary on "Translating the Hidden Words," review by Franklin Lewis . In: Bahá'í Studies Review . Volume 9 , 1999 ( bahai-library.com ).

- ^ The Hidden Words of Bahá'u'lláh