William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare [ ˈwɪljəm ˈʃeɪkspɪə ] (baptized 26 Apr 1564 Jul . at Stratford-upon-Avon ; † 23 Apr. Jul . / 3 May 1616 greg. ibid) was an English playwright , poet and actor . His comedies and tragedies are among the most important plays in world literature and are the most frequently performed and filmed . The surviving complete work includes 38 (according to another count 37) dramas, epic poems and 154 sonnets .

Life

Early Years and Family

Shakespeare's date of birth is unknown. According to church registers at Holy Trinity Church , Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire , he was baptized on 26 April 1564. The baptismal entry is Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakespeare ("William, son of John Shakespeare"). Since the 18th century, April 23 has often been mentioned as his birthday, but this information is not certain and is probably only due to the fact that Shakespeare died on the same day in 1616 (April 23). Sometimes April 23 as Shakespeare's supposed birthday is also supported by the claim that in Elizabethan England children were baptized three days after their birth; in fact, however, such a three-day custom did not exist.

William Shakespeare's parents were John Shakespeare and Mary Arden , who came from a wealthy family. His father was a free landowner and made it to Oberaldermann in his town. Later, however, his fortune declined and he lost his reputation because of his debts.

It is likely that William Shakespeare attended the Latin Grammar School at Stratford-upon-Avon , where he received instruction in Latin, Greek, history, morals and poetry. Lessons at a grammar school imparted knowledge of rhetoric and poetics and also instructed the pupils in the production of small dramas based on the models of antiquity. There is no evidence that Shakespeare attended university like other contemporary English playwrights.

At the age of 18 he married Anne Hathaway (1556-1623), the daughter of a large landowner who was eight years his senior, probably on November 30 or December 1, 1582. The date of the marriage is not known, the marriage license report was ordered on November 27, 1582. This date of enlistment is attested by an entry in the Register of the Diocese of Worcester granting a license to marry "Willelmum Shaxpere et Annam Whateley". The bride's maiden name apparently stands for "Hath(a)way" incorrectly. On November 28, 1582, at the consistory of the aforementioned diocese, a pledge by two friends to the considerable sum of £40 is documented in order to obtain a dispensation from the threefold banning of the marriage of "Willm Shagspere" and Anne Hathwey of Stratford, which was then prescribed. This time-consuming dispensation procedure was necessary so that the marriage could take place before the start of the Christmas season, since banns and weddings were no longer permitted under church law from the first Advent. The daughter Susanna was born about six months after the marriage (baptismal entry May 26, 1583). Almost two years later, twins, son Hamnet and daughter Judith, were born. The baptismal entry in the Stratford parish register of February 2, 1585 read: Hamnet and Judith, son and daughter to William Shakespeare. Nothing is known about the relationship between the couple and their children. Relevant documents do not exist, which is not unusual, however, since personal relationships among the bourgeoisie were not usually recorded in writing, either in private letters or in diaries, which usually did not contain any personal notes. Shakespeare's son Hamnet died in 1596 aged eleven (burial 11 August 1596; cause of death unknown), while Susanna lived to 1649 and Judith to 1662. A letter survives from 1598 in which a certain Richard Quiney asked Shakespeare for a loan of £30. Eighteen years later, on February 10, 1616, William Shakespeare's daughter Judith married his son Thomas Quiney. Shakespeare's daughter Susanna married the physician John Hall on June 5, 1607.

lost years

Little is known about the eight years from 1584/85 to 1592, which Shakespeare scholars refer to as the "lost years". In the absence of sufficient sources, all the more legends have emerged, some of which can be traced back to anecdotes handed down by contemporaries. Essentially, rumors circulating about Shakespeare's life were first recorded in the Shakespeare edition by Nicholas Rowe , who accompanied his edition with a life account of Shakespeare, in which he recorded the surviving myths and legends in a compiled form, but without any critical examination or assessment of each to carry out truthfulness. From a factual point of view, however, such a historical gap in the documentary record is not at all surprising for a young man who was neither involved in litigation nor involved in real estate transactions.

In the centuries that followed up to the present, the sparse stock of historically verified facts about Shakespeare's biography has led to completely different images of his personality and his life, some of which have changed drastically from epoch to epoch. Despite the lack of reliable evidence, the author's image was adapted to the changing historical needs and demands of the various epochs in order to construct the appropriate artist personality for the specific perspective of his works.

The first written document proving that Shakespeare was in London was by the poet Robert Greene , who in a 1592 pamphlet defamed him as an upstart. Greene blasphemed that Shakespeare presumed to compose like the respected poets of his day: there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hard wrapt in a Players hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and beeing an absolute Johannes fac totum, is in his own conceit the onely shake-scene in a countrey . (For there is a crow that has come up, finely decked out in our feathers, that with its tiger heart, tucked into an actor's garb, thinks it can pour out blank verse like the best of you; and comes as an absolute jack of all trades he bills himself as the greatest theatrical shaker in the land.) The phrase shake-scene is a pun on the name Shakespeare .

When the pamphlet was published posthumously, the editor included an apology, suggesting that Shakespeare was already popular and had influential patrons. At that time he was already a member of the troupe Lord Strange's Men , a large part of which formed the Lord Chamberlain's Men in 1594 and was one of the leading acting troupes in London . Shortly after his accession to the throne, James I made them his own as King's Men .

playwright and actor

Although the theatrical system that developed in the Elizabethan period was still unstable and subject to rapid, risky changes, it was just as profitable under favorable conditions. However, this did not apply to the professional poet or playwright as such, who, as numerous examples from this period show, could not live from his work as an author on the flat-rate fees normally granted to him by the acting troupes to whom he sold his drama texts, since all further rights of use were transferred to these theater groups when the manuscript was handed over. The former respectable existence and way of life of the professional poet and author under the patronage of a noble patron whose writing was rewarded with rich donations or honorary pay had largely been lost in Shakespeare's time.

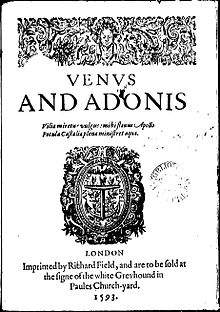

Against this historical background, Shakespeare wrote two short verse epics, Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594), which, unlike all his other works, he published himself and with a signed dedication to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton , mistaken. Since epic works were classified as high literature at the time, while plays were classified as functional literature, Shakespeare probably referred to Venus and Adonis as his first work (" first heir of my invention ") for this reason. In this way he not only gained a high reputation in the circles of literary connoisseurs and lovers, but as the author of these epics he was praised and mentioned by his contemporaries more often than later for his most widely discussed and praised tragedy, Hamlet . This allowed him to appropriately launch his literary career as well as a commercially successful playwright.

As early as the beginning of 1595, Shakespeare was one of the most respected members of Lord Chamberlain's Men , which shortly thereafter became the leading drama troupe, as can be seen from a surviving receipt from the Master of the Revels or the Royal Treasury for a special performance at court dated 15 March 1595 after James I 's accession to the throne in 1603, it was placed under his patronage and thus elevated to the service of the crown. Shakespeare's name appears, along with that of Richard Burbage and well-known actor William Kempe , on a receipt for receipt of ₤20 for two court productions of Lord Chamberlain's Men on behalf of the company, documenting not only his full establishment within the company but his own at the same time official authority to represent the troops to the outside world.

Shakespeare not only wrote a wealth of plays for his theater troupe as their ancestral resident dramatist, but also initially had a 10% financial interest in their profits as a sharer . He also acted as an actor in smaller roles himself. The diary entries of theater entrepreneur Philip Henslowe , for example, document the financial merits of Shakespeare's plays; unlike many other contemporary playwrights, Shakespeare henceforth achieved consistent success not only professionally or artistically, but increasingly in business and society.

His acting troupe was very popular both at court and with the theater audiences of the large public theaters and earned accordingly. Shakespeare signs at two court performances during the Christmas festivities in 1594. From 1596 it can be proven without offsetting that Shakespeare continuously invested money or real estate. When Shakespeare's troupe moved to the newly built Globe Theater in 1599, he was given a one-tenth partnership by James Burbage, whose family had owned the old Globe Theatre . Some time later this figure rose to one in seven in 1608 when Blackfriars was built as a second theater mainly for performances during the winter season.

His greatest poetic competitor was initially Christopher Marlowe , and later Ben Jonson . It was common to rewrite and re-perform older plays: Shakespeare's Hamlet , for example, might be an adaptation of an older 'Ur-Hamlet'. In some cases, legends and fairy tales were also made into drama several times, as in the case of King Lear . Pieces were also based on printed sources, such as Plutarch 's biographies of great men, collections of Italian short stories, or chronicles of English history. Another common method was to write sequels to successful plays. The character of Falstaff in Henry IV was so popular with audiences that Shakespeare reprized it in The Merry Wives of Windsor .

poet and businessman

In addition to his dramatic works, Shakespeare also wrote lyrical and epic poems (presumably when London's theaters had to close temporarily because of the plague epidemics). The latter established his reputation as an author among his contemporaries. It was probably in 1593 that he wrote the two verse narratives Venus and Adonis and Lucrece mentioned above . The subsequent publication of 154 sonnets in 1609 is surrounded by many mysteries. In a short publisher's introduction, which is usually read as a "dedication", the only begetter and Mr. WH is mentioned; the identity of this person has not been clarified to this day. Perhaps this sonnet publication is a pirated edition .

As co-owner of London's Globe Theatre , which his company had built to replace the Theater after its lease expired, Shakespeare found increasing success as a poet and businessman. The Lord Chamberlain's Men , named after their patron and sponsor , often performed at Queen Elizabeth's court. Under Elizabeth's successor , James I , they called themselves the King's Men , after their royal patron .

As a partner in the Globe , Shakespeare acquired considerable wealth and influence. In 1596 his father, John Shakespeare , was granted a family crest, which he had unsuccessfully applied for in 1576. The relevant document (reprinted in Chambers, Shakespeare, Vol. II, pp. 19-20) states: “Wherefore being solicited and by credible report 'info'rmed, That John Shakespeare of Stratford vppon Avon, 'in' the count' e of Warwike, ‹…› was advanced & rewar>ded ‹by the most prudent› prince King Henry the seventh ‹…› This sh‹ield› or ‹cote of› Arms, viz. Gould, on a bend sables, a spear of the first steeled argent. And for his crest of cognizaunce a falcon his winges displayed Argant standing on a wrethe of his coullers: suppo‹rting› a Speare Gould steeled as aforesaid sett vppon a helmett with mantelles & tasselles as hath ben accustomed and doth more playnely appeare depicted on this margent: Signefieing hereby & by the authorite of my office aforesaid ratefieing that it half lawfull for the said John Shakespeare gentilman and for his children yssue & posterite (at all tymes & places convenient) to bear and make demonstracon of the same Blazon or Atchevment vppon theyre Shieldes, Targetes, escucheons, Cotes of Arms, pennons, Guydons, Seales, Ringes, edefices, Buyldinges, vtensiles, Lyveries, Tombes, or monumentes or otherwise for all lawfull warlyke facts or ciuile vse or exercises, according to the Lawes of Arms , and customs that to gentillmen belongethe without let or interruption of any other person or persons for vse or bearing the same.”

Although the name of William Shakespeare is not explicitly mentioned in the document on the award of the coat of arms by the College of Arms , the royal coat of arms office, dated October 20, 1596, which was expressly confirmed again in 1599, it can be assumed that he used this leadership of a promoted and funded the family crest. With the transfer of the right to carry the coat of arms to Shakespeare's father, which included all children and grandchildren, Shakespeare was now associated with the status of gentleman and with it immense social advancement. For example, in his role as theater man he also used this newly acquired right of coat of arms and henceforth used the addition gentleman in all documents as a designation of his status.

In addition to his economic transactions in the theater business, Shakespeare was also active as a businessman and investor in numerous businesses outside of the theater company. He invested most of his money in buying real estate in his native town of Stratford. Thus, on May 4, 1597, he bought New Place , the second largest house in town, for his manor house, and on May 1, 1602 acquired 43 hectares (107 acres ) of farmland, along with woodland and common land use rights. On September 28, 1602 he bought another house and land across from his manor and on July 24, 1605 acquired the right to collect part of the tithes of various peasant leases for a price of ₤440, bringing him a net annual income of ₤40. Shakespeare not only invested his fortune, but also managed his new acquisitions and made further profits from them. He rented and leased land or farmland, sold his rubble to the community or collected debts through lawsuits, and also speculated in grain hoarding alongside his interests in various collective activities of the large landowning group. In London, Shakespeare also bought a house and shop in the immediate vicinity of Blackfriars Theatre .

The acquisition of the Blackfriars Theater in 1596 by the theater entrepreneur James Burbage , in which, as already explained, Shakespeare has also been involved since then, was not only profitable for Shakespeare. Unlike the Globe , it was a covered theater where the troupe played during the winter months from then on. The audience there was more exclusive than at the large open-air stages because of the considerably higher admission prices.

While Shakespeare was on the one hand purposeful in his efforts to increase his fortune and his social advancement, on the other hand he did little or nothing to promote his literary prominence. Although he probably wrote his numerous works with a great deal of energy, he did not make use of the limited but still existing opportunities for self-portrayal as an author and poet: with the exception of the short works mentioned above, he did not have any of his individual works printed himself , nor did he himself commission a complete edition of his plays. He also made little attempt to publicize his authorship as an author, and likewise refrained from providing a literary self-portrait in prefaces or introductions to the works of other poets, as did, for example, his contemporary Ben Jonson . As much as he cared about his social advancement, he seemed to have been all the less interested in his artistic fame and the conscious, planned promotion of his poetic and literary career.

Nonetheless, by 1598 at the latest, he had achieved such a degree of notoriety and popularity that Shakespeare's name tended to appear in large form on the frontispieces of the first printed editions, sometimes even in works not written by him. His name was also listed in various contemporary best lists, in particular that of Francis Meeres.

last years

At the age of 46, Shakespeare returned to Stratford as a wealthy man and spent his last years there as the second richest citizen, although unlike his father he was not actively involved in local government. He did not completely sever ties with his former colleagues, and he was a co-author in several theater productions. Several visits to London are documented for the years that followed, most of which had family and friendly reasons.

Shakespeare died at Stratford in 1616, aged 52, ten days after his great Spanish contemporary , Miguel de Cervantes , and was buried on 25 April 1616 in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church . As a “gentleman” he was entitled to this place of honor befitting his status. The stone slab marking his grave bears the inscription:

GOOD FREND FOR JESUS SAKE FORBEARE,

TO DIGG THE DVST ENCLOASED HEARE.

BLESTE BE THE MAN THAT SPARES THES STONES,

AND CVRST BE HE THAT MOVES MY BONES

- O good friend, for Jesus' sake do not dig

- in the dust that lies trapped here.

- Blessed be who spares these stones,

- Cursed be who moves my bones.

According to a local tradition, Shakespeare is said to have written this doggery verse with the curse it contains to deter all attempts to open the tomb later on before his death.

Probably shortly after Shakespeare's death, a memorial bust with an inscription in Latin was erected in the side wall of the church by an unknown person.

Shakespeare's former theater colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell published his works under the title Mr William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories and Tragedies in a large format book called the First Folio . The volume is preceded by an acknowledgment by Ben Jonson stating:

Triumph my Britain, thou hast one to show

To whom all scenes of Europe homage owe.

He was not of an age, but for all time! ...

- Britain, rejoice you call it your own,

- before which Europe's stages bow.

- He does not belong to one time, but to all times! ...

The cause of death is not known. Some 50 years after Shakespeare's death, however, John Ward, vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford, noted in his diary: 'Shakespeare, Drayton , and Ben Jonson had a merry meeting, and apparently drank too much; for Shakespeare died of a fever which he had contracted.” This news is now considered an anecdote without factual content, but its true essence may lie in the fact that in the year Shakespeare died a typhus epidemic was rampant, to which the poet fell victim could be.

Shakespeare's Will and Legacy

Shortly before his death, probably in January 1616, Shakespeare drafted his will and had it drawn up by the notary Thomas Collins. This notarized will is dated March 25, 1616 and consists of three closely written leaves, each signed by Shakespeare himself. Shakespeare's will was not rediscovered until the 18th century. The surviving copy, with numerous revisions, changes and additions to the drafting during the period between January and March 1616, represents the most extensive private document surviving by Shakespeare himself. Shakespeare's shaky signature on the first two pages is seen by various Shakespeare researchers as an indication of Shakespeare's already very poor state of health, which could also have been the reason why a final fair copy of the entire testamentary disposition was apparently dispensed with.

Most of Shakespeare's estate went to his eldest daughter, Susanna, who, together with her husband, received all of the house and property, including the leaseholds acquired by Shakespeare. In the first place in the will, however, her younger sister Judith is named as the first of the heirs. To her Shakespeare bequeathed ₤100 from the estate, plus a further ₤50 in the event of an cession of the claim to the house in Chapel Lane opposite Shakespeare's mansion, New Place . If she or one of her children were still alive three years after the will was drawn up, a further ₤ 150 was earmarked for her, of which she was only entitled to dispose of the interest for the duration of her marriage. Shakespeare expressly prevented her husband from accessing Judith's entire share of the inheritance in his will by deleting the word "son-in-law".

Shakespeare left his sister Joan an amount of ₤20 in addition to his clothing and a lifelong occupancy at his father's Henley Street estate for a small nominal rent. Additionally, Shakespeare's will awarded gifts of money to his Stratford friends and a comparatively generous endowment of ₤10 to the poor in the community. The three former fellow actors Richard Burbage and John Heminges and Henry Condell , who later edited the First Folio of 1623, were also considered by Shakespeare.

In previous biographical Shakespeare research, the focus of interest has been on a single sentence in the Legacy, which has raised numerous questions and has given rise to very different, sometimes purely speculative interpretations and interpretations up to the present: « Item, I give unto my wife my second best bed wih the furniture », whereby in the language of the time furniture could be understood both as bedding and as furnishings. The name of Shakespeare's wife Anne appears nowhere else in the will except for this passage.

Some of the later Shakespeare biographers interpret this largely missing provision for his wife Anne in Shakespeare's last will as an overt expression of his indifference or even contempt for her. On the other hand, another part of the biographers refers to the widow's right to maintenance, which was common in England at the time. As a widow, she was already entitled to a third of her deceased husband's entire belongings and a lifelong right to live in the house he left behind, even without a special disposition. Therefore, an explicit mention of his wife in the will was superfluous. The legacy of the "second best bed" is also sometimes interpreted as a special token of affection or love, since the "best bed", so the reasoning, was reserved for the guests and this "second best bed" was the shared marriage bed, which Shakespeare may have subsequently explicitly granted to his wife at her special request.

In contrast to this, however, it is sometimes pointed out, especially in recent research, that this customary law with regard to widows' claims in Elizabethan-Jacobean England was by no means uniform, but bound to local customs and therefore varied from place to place. In his 1991 study, the renowned Shakespeare scholar EAJ Honigmann , in particular, came to the conclusion in his comparison with wills of similarly wealthy families from this period that the explicitly mentioned, quite meager legatee for his wife in Shakespeare's last will was in this form does not correspond to the usual wording of a will.

In a retrospective overall view of the will, the recognized German Shakespeare researcher Ulrich Suerbaum primarily sees clear signs that Shakespeare was primarily concerned with a closed transfer of his entire possessions; he tried to take into account the other inheritance claims in such a way that the main inheritance could be transferred without any major reduction. He therefore left only one object of remembrance, which is to be understood more as a symbol, to all other people who were friends or family members of him.

Shakespeare portraits

A few pictorial representations and portraits of Shakespeare have survived. As the playwright's reputation grew, these images were copied many times and modified to a greater or lesser extent. Several unsecured works were also identified as Shakespeare portraits early on.

The only two portraits likely to depict the historical William Shakespeare were made posthumously:

- the Droeshout engraving (1623), the frontispiece of the title page of the first folio edition. It was probably engraved based on a template that is now lost. The artist is traditionally Martin Droeshout the Younger (* 1601), but recently the older Martin Droeshout (1560-1642) has also been mentioned.

- the funerary monument at Holy Trinity Church , Stratford-upon-Avon (before 1623).

What is also considered to be probably authentic is what may have been written during the poet's lifetime

- Chandos portrait (from c. 1594–1599). The exact date of origin is unknown, the painter was probably Joseph Taylor (1585-1651). Research by curator Tarnya Cooper in 2006 showed that the image dates from Shakespeare's time and could represent the poet.

Other portraits, about whose authenticity there is no broad consensus and some of which are very controversial, include:

- the Sanders portrait, discovered in Canada in 2001, was probably painted during Shakespeare's lifetime, according to investigations

- the Cobbe portrait , made public in 2006 and presented to the public in 2009, is accepted as authentic by Stanley Wells and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Stratford-upon-Avon

- the Flower portrait of 1609, which was initially believed to be a 19th-century forgery following a 2004 investigation by the National Portrait Gallery. More recently, however, more recent research has led to the assumption that this portrait was not, as previously assumed, based on the Droeshout engraving of 1623, but rather that the engraving of 1623 was probably used as a model. For example, the recognized German Anglicist and Shakespeare researcher Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel , based on her extensive investigations into the authenticity of the Darmstadt death mask, assumes that not only the Chandos portrait but also the Flower portrait is authentic. However, given the current state of research, this hypothesis is still being discussed controversially.

- the Janssen portrait, by the same painter as the Cobbe portrait, known since 1770, restored 1988.

The following are considered to be inauthentic:

- the Ashbourne portrait , preserved in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC

- the so-called Darmstadt death mask, known since 1849; the authenticity is claimed only by Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel

- the Davenant bust, from ca. 1613, in terracotta; the authenticity is also only claimed by Hammerschmidt-Hummel.

Shakespeare's language

Shakespeare had an extensive vocabulary: there are 17,750 different words in his works. Characteristic of Shakespeare is his stylistic diversity, which, from the lowest street language to the highest court language, has mastered all language levels and registers equally. A special feature of his literary language is the diverse use of imagery (imagery) .

In Shakespeare's time, grammar, orthography and pronunciation were not as standardized as they had been, increasingly, since the eighteenth century. It was also possible and common to coin new words when the need arose. Many terms found in modern English appear for the first time in Shakespeare ( e.g. multitudinous, accommodation, premeditated, assassination, submerged, obscene ). However, the impression that Shakespeare invented more new expressions and phrases than any other English poet can be partly explained by the fact that the Oxford English Dictionary , which was created in the 19th century, prefers to use quotations from Shakespeare as the first reference.

authorship of his works

The established scientific Shakespeare research assumes at the current stage of the discussion that doubts about the authorship of William Shakespeare from Stratford on the work traditionally attributed to him are unfounded. For more than 150 years, however, there has been a debate about “true” authorship. This is due not least to the fact that the image of the “genius poet” that originated in the Romantic era seems incompatible with a person like the business-oriented London theater entrepreneur Shakespeare. The first folio edition of 1623, with its concrete definition of Shakespear's drama corpus, disregarding the apocryphal plays that preceded it, did the rest to outline the image of a suddenly appearing genius who could easily be converted into that of a straw man. The problematization of William Shakespeare's authorship of the work attributed to him is not considered a legitimate research topic by mainstream academic Shakespearean scholarship. Individual Shakespeare scholars, however, criticize the refusal of academic literary studies to seriously discuss with non-academic (and now also some academic) researchers who also describe themselves as "anti-Stratfordians". ( Stratfordians are thus those individuals who believe that Stratford-born William Shakespeare is the author of the works attributed to him.)

The background to the authorship debates among many "anti-Stratfordians" is the view that the poet of Shakespeare's works could not have been a simple man with little education from the provinces. In doing so, instruction at a grammar school , such as Shakespeare probably attended at Stratford, provided the basic knowledge and skills needed to acquire the knowledge that went into his plays. In the 18th century, Shakespeare was considered an uneducated author. One cannot very well claim both: the author of the plays has an inexplicably high education and at the same time he had only little education. Another argument against Shakespeare's authorship of his works is that no original manuscripts of his works have survived, apart from the controversial manuscript of the play Sir Thomas More . However, this is not unusual for authors of the 16th century. Moreover, the six surviving Shakespeare's autograph signatures are considered by some judges to be so clumsy that they may have rendered downright illiterate. But this too is an assessment from a modern point of view that does not take historical reality into account.

The discussion about the actual author of the works of Shakespeare begins with the writer Delia Bacon . In her book The Philosophy of Shakespeare's Plays (1857) she developed the hypothesis that behind the name William Shakespeare was a group of writers consisting of Francis Bacon , Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser . Their publication sparked further speculation that continues to this day, with new candidates constantly being named for authorship.

Among the people cited as possible authors of Shakespeare's works, the most frequently cited are Francis Bacon , William Stanley and, more recently, Edward de Vere . Alongside this, Christopher Marlowe also plays a certain role (see Marlowe theory ). In the 19th and 20th centuries, prominent personalities such as Georg Cantor , Henry James and Mark Twain publicly took a stand in line with the anti-Stratfordian theses.

Reception in Germany

In Germany, the reception of Shakespeare has an eventful history, in which the poet was employed for a wide variety of interests.

Shakespeare was of great importance for the literary theory of the Enlightenment with Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (in the 17th Literaturbrief 1759), for the dramatists of the Sturm und Drang for example with Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg ( Letters on the Strange Things of Litteratur , 1766/67), with Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz ( Notes on the Theater , 1774), with Johann Gottfried Herder ( From German Art and Art , 1773) and with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe ( Speech on Schäkespears Day , 1771), also with the amateurish but all the more enthusiastic Ulrich Bräker ( Something about William Shakespears plays of a poor unlearned cosmopolitan who had the good fortune to read them (Anno 1780) ; likewise for German Romanticism , notably in August Wilhelm von Schlegel (Vienna Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature 1809–1811) and for nineteenth-century drama theory . The theorist Johann Christoph Gottsched , who was influential in the early 18th century and was committed to the French classicism of the 17th century. based on the three Aristotelian units of French drama theory, had, like Voltaire before him, spoken quite disparagingly about Shakespeare. In the second half of the century, however, Shakespeare became the prototype of genius for the drama theorists of the late Enlightenment and Sturm und Drang and not only remained in the judgment of the theater poet of an unrivaled “star of the highest height” (Goethe) up to the present day.

The theater principal Abel Seyler and the Seylersche Schauspiel-Gesellschaft contributed significantly to Shakespeare's popularity in German-speaking countries in the 1770s; Seyler also had the great merit of Shakespeare's actual entry into the National Theater in Mannheim , founded on November 2, 1778, which he led as founding director.

One of the peculiarities of the German reception of Shakespeare since Romanticism is the view that the Germans have a special affinity for Shakespeare, that his work is closer to the German soul than to the English one. The study of Shakespeare and the popularization of his work, which reached into the political realm, found institutional anchoring in the German Shakespeare Society , which was founded in 1864 more by enthusiasts than by specialist philologists. It is the oldest Shakespeare society in the world and significantly older than the English one. On the occasion of Shakespeare's 400th birthday, the German Shakespeare Society and the Institute for Theater Studies at the University of Cologne compiled a documentation and exhibited it in the Bochum Art Gallery and in Heidelberg Castle under the title Shakespeare and the German Theater .

The number of Germanizations (often specially prepared for individual productions) by Shakespeare over the past 250 years cannot be overlooked. Well-known transmissions of the dramas are the editions by Christoph Martin Wieland and by Johann Joachim Eschenburg (both published in Zurich) and by Gabriel Eckert (who revised the Wieland/Eschenburg texts in the so-called "Mannheimer Shakespeare"), by Eduard Wilhelm Sievers , the one by Johann Heinrich Voß and his sons Heinrich and Abraham, the Schlegel-Tieck edition (by August Wilhelm von Schlegel , Wolf von Baudissin , Ludwig Tieck and his daughter Dorothea Tieck ) and, in older times, the translations of individual pieces by Friedrich von Schiller or Theodor Fontane , more recently the versions by Hans Ludwig Rothe , which were very popular during the Weimar Republic because they were suitable for the stage, but which were banned after a Goebbels decree, as well as the extensive translation (27 pieces) by Erich Fried and the complete translation by Frank Günther . Recent translations of individual pieces that caused a stir were e.g. B. those of Thomas Brasch and Peter Handke .

In recent years, Shakespearean translation activity has refocused on the sonnets , which many translators have attempted since the eighteenth century.

Shakespeare's work has become the richest source of sayings over the centuries . Only the Bible is quoted more often.

The outer main belt (2985) Shakespeare asteroid is named after him.

Films about Shakespeare (selection)

In addition to numerous film adaptations of Shakespeare's works, there are also various films about him and his life. These are mostly fictional adaptations of the author's biography, dramatizations or comedies. A well-known example of the latter is 1998 's Shakespeare in Love . This Oscar -winning romantic comedy starred Joseph Fiennes in the role of the poet. Also a romantic comedy was the 2007 Spanish film Miguel y William , about the poet's fictional meeting with Miguel de Cervantes .

As early as 1907, Shakespeare's writing "Julius Caesar" was the first short film that must currently be considered lost.

In the 1999 film Blackadder: Back & Forth , which continues the Blackadder series and is a comedy, the poet is portrayed by Colin Firth . In the 2005 BBC production A Waste of Shame , Shakespeare's sonnets are used to tell a story about how they came about. Rupert Graves took on the role of the poet.

Roland Emmerich 's film Anonymus (2011) is a historical thriller that also involves William Shakespearean authorship . Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford held the actual authorship of the works of the Briton. In Bill (2015), on the other hand, the rather unknown periods of Shakespeare's life, the so-called lost years, are dealt with in an adventurous family comedy. Directed by Richard Bracewell, Mathew Baynton took on the leading role.

Kenneth Branagh , who himself was responsible for several Shakespeare film adaptations as a director, made All Is True , a film about the last years of Shakespeare's life. Branagh also took on the leading role.

factories

Shakespeare was primarily a playwright, but he also wrote two epic poems and 154 sonnets . The first attempt at a complete edition of his theatrical works appeared posthumously in Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories and Tragedies , known as the folio edition . This contains 36 dramas, including 18 previously unpublished, a foreword by the editors and poems of praise and dedication.

The drama Cardenio , performed in 1612, has not survived . Also not counted is collaboration on Sir Thomas More , a play written by several authors; More recently, however, Shakespeare's participation has again been called into question. A number of dramas have been attributed to Shakespeare since the third folio edition (1662). Apart from Pericles, which is accepted as an authentic work, co-written by Shakespeare with another author, these plays, referred to as 'Apocrypha', have long since ceased to be considered candidates for inclusion among the genuine works of Shakespeare. Researchers are constantly discussing attributions and write-downs of other works and the collaboration of other authors on his works or the collaboration of Shakespeare on the works of other authors. More recent proposed attributions concern Edward III and Double Falshood or The Distrest Lovers . Edward III (printed 1596) assumes Shakespeare's co-authorship (including Brian Vickers); the drama was included in the most recent edition of The Norton Shakespeare and in the second edition of The Oxford Shakespeare. Double Falshood , whose authorship has been controversial since the early 18th century, became part of the Arden Edition of Shakespeare's works in 2010.

historical dramas

- King John ( King John , c. 1595/96)

- Henry VIII ( King Henry VIII or All Is True , ca. 1612/13)

-

Henry VI

- Part 1 ( King Henry VI, Part 1 ; 1591)

- Part 2 ( King Henry VI, Part 2 ; 1591–1592)

- Part 3 ( King Henry VI, Part 3 ; 1591–1592)

- Richard III ( King Richard III ; c.1593, printed 1597)

- Richard II ( King Richard II ; between 1590 and 1599, printed 1597)

- Henry IV

- Henry V ( King Henry V ; 1599, pirated print 1600 )

comedies

Cheerful comedies

- The Comedy of Errors ( c . 1591, printed 1623)

- Lost Lovemaking (also: Liebes Leid und Lust ; Love's Labour's Lost ; c. 1593, printed 1598)

- Taming of the Shrew ( The Taming of the Shrew ; c.1594, printed 1623)

- Zwei Herren aus Verona ( The Two Gentlemen of Verona ; ca. 1590–1595, printed 1623)

- Ein Sommernachtstraum ( A Midsummer Night's Dream ; 1595/96, printed 1600)

- The Merchant of Venice ( The Merchant of Venice ; 1596)

- Much Ado About Nothing ( Much Ado about Nothing ; c.1598/99, printed 1600)

- As You Like It ( As You Like It ; c.1599, printed 1623)

- The Merry Wives of Windsor ( The Merry Wives of Windsor ; 1600/01)

- Was Ye Want ( Twelfth Night or What You Will ; c.1601, printed 1623)

problem pieces

- Troilus and Cressida ( Troilus and Cressida ; c. 1601, printed 1610)

- All's well that ends well ( All's Well That Ends Well ; 1602/03, printed 1623)

- Measure for Measure ( c. 1604, printed 1623)

romances

- Pericles, Prince of Tire ( Pericles, Prince of Tyre ; c.1607, first printing 1609)

- Das Wintermärchen ( The Winter's Tale ; 1609, printed 1623)

- Cymbeline ( Cymbeline ; 1610)

- Der Tempest ( The Tempest ; 1611, printed 1623)

tragedies

Early Tragedies

- Titus Andronicus (c.1589–1592, printed 1594)

- Romeo and Juliet ( Romeo and Juliet ; 1595, printed 1597 ( pirated ), then 1599)

Roman dramas

- Julius Caesar ( The Tragedy of Julius Caesar ; 1599, printed 1623)

- Antony and Cleopatra ( Antony and Cleopatra ; c.1607, printed 1623)

- Coriolanus ( Coriolanus ; c.1608, printed 1623)

Later tragedies

- Hamlet ( Hamlet, Prince of Denmark ; c. 1601, printed 1603, possibly pirated )

- Othello (circa 1604, printed 1622)

- King Lear ( King Lear ; c.1605, printed 1608)

- Timon of Athens ( Timon of Athens ; c.1606, first printing 1623)

- Macbeth (circa 1608, printed 1623)

poetry

- Venus and Adonis ( Venus and Adonis ; 1593)

- Lucretia ( The Rape of Lucrece ; 1594)

- A Lover's Complaint ( 1609 )

- The Pilgrim in Love ( The Passionate Pilgrim ; 1609, contains two sonnets from Shakespeare and three verse parts from Love's Labour's Lost )

- The Phoenix and the Turtle Dove ( The Phoenix and the Turtle ; printed 1601)

- Sonnets ( Sonnets ; 1609)

expenditure

Old Spelling editions

- The First Folio of Shakespeare . The Norton Facsimile. Ed. by Charlton Hinman. Norton, NY 1969.

- The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Edited and glossed by WJ Craig, London 1978.

- The Oxford Shakespeare. The Complete Works. Original spelling edition . Ed. by Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, William Montgomery. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1987.

Modernized editions

- The Arden Shakespeare. Complete Works . Revised edition. Ed. by Ann Thompson, David Scott Kastan, Richard Proudfoot. Thomson Learning, London 2001. (without the annotations of the Arden separate editions)

- The Oxford Shakespeare. The Complete Works . second edition. Ed. by Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, William Montgomery. Clarendon Press, Oxford 2005. (no annotations)

- The Norton Shakespeare . Based on the Oxford Edition. second edition. Ed. by Stephen Greenblatt, Jane E. Howard, Katharine Eisaman Maus. Norton, NY 2008.

translations

- Shakespeare's Dramatic Works. New edition in nine volumes . Translation by August Wilhelm Schlegel and Ludwig Tieck. Printed and published by Georg Reimer, Berlin 1853 to 1855.

- William Shakespeare: Dramas. With an afterword and notes by Anselm Schlösser, 2 volumes. Berlin/Weimar 1987.

- William Shakespeare: The Complete Works in Four Volumes. (Edited by Günther Klotz, translation by August Wilhelm Schlegel, Dorothea Tieck, Wolf Graf Baudissin and Günther Klotz, with editor's notes). Structure, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7466-2554-8 .

- Shakespeare Complete Edition in 39 volumes. Translation by Frank Günther ; published until 2020: 38 volumes; the sonnets are missing. Ars vivendi Verlag, Cadolzburg.

CD-ROM Edition

- Shakespeare, complete works, English & German , Schlegel/Tieck translation, Directmedia Publishing , Berlin 2004, Digitale Bibliothek (Product) , Volume 61, ISBN 978-3-89853-461-1 .

audiobook

- Robert Gillner (ed.): Shakespeare for Lovers . Voiced by: Catherine Gayer , David Knutson et al. Monarda Publishing House, Halle 2012, 2 CD, 92 minutes.

See also

- Elizabethan world view

- Elizabethan Theater

- Shakespeare stage

- List of films made into films by William Shakespeare

- Shakespeare Research Centers

literature

- Peter Ackroyd : Shakespeare: The Biography. Translated from the English by Michael Müller and Otto Lucian. Knaus, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8135-0274-0 .

- Harold Bloom: Shakespeare. The invention of the human. comedy and history. From the American by Peter Knecht. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2002.

- Harold Bloom: Shakespeare. The invention of the human. Tragedies and late romances. From the American by Peter Knecht. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2002.

- Edmund K Chambers: William Shakespeare. A study of facts and problems . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1930.

- Thomas Döring: How we like it - Poems on and about William Shakespeare. An anniversary anthology to commemorate Shakespeare's 450th birthday and the 70th anniversary of the publishing house. Manesse Verlag Zurich 2014, ISBN 978-3-7175-4086-1 .

- Nicholas Fogg: Hidden Shakespeare: a Biography. Amberley, Stroud 2012, ISBN 978-1-4456-0769-6 .

- Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in His Time . CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 .

- Stephen Greenblatt : Will in the world. How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare . Berlin-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-8270-0438-1 .

- Stephen Greenblatt: Negotiations with Shakespeare. Interior Views of the English Renaissance . Wagenbach, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-8031-3553-2 .

- Frank Günther: Our Shakespeare. Insights into Shakespeare's stranger-related times. Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-423-26001-5 .

- Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel : William Shakespeare - His Time - His Life - His Work . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-2958-X .

- Graham Holderness: Nine Lives of William Shakespeare. Continuum, London et al. 2011, ISBN 978-1-4411-5185-8 .

- Ernst AJ Honigmann: The Lost Years . Manchester University Press, 1985, ISBN 0-7190-1743-2 .

- Ernst AJ Honigmann: Shakespeare's Life In: Margreta de Grazia and Stanley Wells (eds.): The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-521-65094-1 , pages 1–13.

- Charles T. Onions : A Shakespeare glossary. Oxford 1911; 2nd edition ibid 1919; reprinted in 1929.

- Günter Jürgensmeier (ed.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86971-118-8 .

- Irvin Leigh Matus: Shakespeare, In Fact. Continuum, New York 1999, ISBN O-8264-0928-8.

- Roger Paulin: The Critical Reception of Shakespeare in Germany 1682-1914. Native literature and foreign genius . (Anglistic and Americanistic Texts and Studies, 11). Olms, Hildesheim and others 2003, ISBN 3-487-11945-5 .

- Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 .

- Samuel Schoenbaum: William Shakespeare. A documentary of his life. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-458-04787-5 .

- Samuel Schoenbaum: Shakespeare's Lives . New edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-818618-5 .

- Marvin Spevack: A complete and systematic concordance to the works of Shakespeare. Volume I ff., Hildesheim 1970.

- Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare's Plays . UTB, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8252-1907-0 .

- Ian Wilson: Shakespeare-The Evidence. Unlocking the Mysteries of the Man and his Work . London 1993, ISBN 0-7472-0582-5 .

web links

- Literature by and about William Shakespeare in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about William Shakespeare in the German Digital Library

- Literature by and about William Shakespeare in the WorldCat bibliographic database

- Publications by and about William Shakespeare in VD 17 .

- Works by William Shakespeare at Zeno.org .

- Works by William Shakespeare in the Gutenberg-DE project

- William Shakespeare at Internet Archive

- German Shakespeare Society e. V

- Shakespeare works in English and German in the Gutenberg.net project

- British Library – Shakespeare in Quarto (English)

- Folger Shakespeare Library

- John R Wise: Shakespeare. His Birthplace and its Neighborhood Published by Smith Elder & Co., London 1861

- Shakespeare and the lure of biography

itemizations

- ↑ Date of death according to the Julian calendar in use throughout Shakespeare's lifetime in England (April 23, 1616); According to the Gregorian calendar , introduced in Catholic countries in 1582 but not until 1752 in England , the poet died on May 3, 1616. This gives him the same date of death as the Spanish national poet Cervantes , although he survived him by ten days.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 14 and Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Reclam, Ditzingen 1989, ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , p. 347. Likewise Günter Jürgensmeier (ed.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86971-118-8 , p. 11. See also the image source of the entry in Quagga Illustrations [1] . Retrieved September 12, 2020. Due to the Elizabethan peculiarities of the spelling of the name and the more than eighty different spellings of the name of the family of Shakespeare ( Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Die Zeit, der Mensch, das Werk, die Nachwelt. 5th revised and supplemented edition Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p . Volume 13 , Bertelsmann Lexikothek Verlag , Gütersloh 1996, ISBN 3-577-03893-4 , p. 206.or Bernd Lafrenz: William Shakespeare 1564–1616 .

- ↑ EK Chambers: William Shakespeare - A Study of Facts and Problems . At the Clarendon Press, Oxford 1930. Volume 2, p. 1 f. See also Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A civil life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here p. 347. Suerbaum sees Shakespeare's birthday as being fixed on the April 23, the day of the feast of the national saint St. George , also as part of the Shakespeare legend. Similar to the presentation in Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 136 f.

- ↑ Chambers, vol. 1, p. 13; Volume 2, p. 2.

- ↑ TW Baldwin: William Shakespere's Small Latine and Lesse Greeke. university of Illinois Press, Urbana 1944, 2 vols. Academics generally accept Baldwin's evidence that Shakespeare did, in fact, attend grammar school, as specifically in Charles Martindale/Michelle Martindale: Shakespeare and the Uses of Antiquity: An Introductory Essay . Routledge, London 1989, p. 6. However, Shakespeare's school attendance is not historically documented; However, such a lack of documentation of school attendance has little significance, since school attendance in Shakespeare's time was usually not recorded by written evidence and student lists from the Grammar School in Stratford have only existed since around 1800. A visit to the grammar school is generally considered very likely or "almost certain" in Shakespeare research due to Shakespeare's educational horizon and the numerous quotations from school books in his dramatic works. According to Frank Günther, the social position of Shakespeare's family of origin also speaks for the high degree of certainty of such an assumption. His father was mayor of the city of Stratford at the time, and thus the highest official, enjoyed high social respect, attached great importance to behavior befitting his status and was considered to be career-oriented. Since school attendance was free and education was an important means of social advancement, it can be assumed with high probability that Shakespeare was sent to grammar school as the eldest son . In any case, with the current state of research, the assumption is undisputed that Shakespeare acquired the knowledge imparted in a grammar school of the time, although his academically trained poetic rival Ben Jonson later described this knowledge of Shakespeare as "small Latin and less Greek" (Eng .: "hardly any Latin and even less Greek") downplayed. See also Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A civil life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here p. 350, and Frank Günther: Our Shakespeare: Insights into Shakespeare's Stranger-Kind Times. Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2nd edition Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-423-14470-4 , pp. 188-194. See also Samuel Schoenbaum: The Life of Shakespeare. In: Kenneth Muir and Samuel Schoenbaum (eds.): A New Companion to Shakespeare Studies. Cambridge University Press 1971, reprinted 1976, ISBN 0-521-09645-6 , pp. 1–14, here pp. 3f.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here pp. 351f. See also Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 137-140. for the biographical information also Samuel Schoenbaum : The Life of Shakespeare. In: Kenneth Muir and Samuel Schoenbaum (eds.): A New Companion to Shakespeare Studies. Cambridge University Press 1971, reprinted 1976, ISBN 0-521-09645-6 , pp. 1–14, here pp. 4f. The baptism of the first child on May 26, 1583 has led to a great deal of speculation in various Shakespearean biographies; documentary proof of a previous engagement of the couple or the conclusion of a marriage precontract , which was common in Elizabethan times , d. H. of a promise of marriage does not exist, although such an engagement cannot be ruled out entirely. For more details, see Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. The time, man, the work, posterity , ibid p. 138f.

- ↑ Chambers, Vol. 2, p. 101: Loving countryman; I am bold of you as of a friend, craving your help with £ 30... You shall neither lose credit nor money by me... so I commit this to your care and hope of your help .

- ↑ Cf. Samuel Schoenbaum: William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life . Revised edition Oxford University Press , New York et al. 1987, ISBN 0-19-505161-0 , pp. 292ff. and p. 287.

- ↑ Arthur Acheson: Shakespeare's Lost Years in London . Brentano's, New York 1920.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 121 as well as the detailed presentation of the traditional legends of Shakespeare's life, for example as a poacher or groom, ibid. p. 122ff. On the other hand, the well -known Shakespeare scholar Samuel Schoenbaum , in his biography of Shakespeare, considers it quite possible that from about the summer of 1587 Shakespeare joined one of the traveling theaters, the Leicester's , Warwick's or Queen' Men as an actor, who traveled through the provinces and lived in also made appearances at Stratford in the 1580s. See Samuel Schoenbaum: The Life of Shakespeare. In: Kenneth Muir and Samuel Schoenbaum (eds.): A New Companion to Shakespeare Studies. Cambridge University Press 1971, reprinted 1976, ISBN 0-521-09645-6 , pp. 1–14, here p. 5.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A civic life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345–376, here pp. 350f. See also fundamentally Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 118ff.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Stuttgart 2006, 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 13f. Nevertheless, Shakespeare's biography, which has been the subject of extensive research and is based on numerous surviving documents and registered entries, is probably the best-documented citizen biography from the Elizabethan age. See also Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeares Dramen. UTB, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8252-1907-0 , p. 241f.

- ↑ Chambers, Vol. 1, p. 58.

- ↑ See also Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 144–146.

- ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here pp. 354-357. See also Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 146ff.

- ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here pp. 358f. See also Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 146–130. See also Samuel Schoenbaum: The Life of Shakespeare. In: Kenneth Muir and Samuel Schoenbaum (eds.): A New Companion to Shakespeare Studies. Cambridge University Press 1971, reprinted 1976, ISBN 0-521-09645-6 , pp. 1–14, here pp. 6f.

- ↑ See et al. Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 146f.

- ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here pp. 358f.

-

↑ Raymond Carter Sutherland: The Grants of Arms to Shakespeare's Father. In: Shakespeare Quarterly. Volume 14, 1963, pp. 379-385, here: p. 385:

“…the still often-made statement that William secured arms to show the fact that he had 'arrived' is pure assumption with no basis in fact and may seriously misrepresent not only his attitude toward heraldry and society but also his relationship with the other members of his family.” - ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here pp. 361-363. See also Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare's dramas. UTB, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8252-1907-0 , p. 244ff. See also Frank Günther: Our Shakespeare: Insights into Shakespeare's strange-related times. Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2nd edition Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-423-14470-4 , p. 184 ff. In this context, Günther also refers to the social network around Shakespeare's family, which can be clearly documented by records and historical documents that have been handed down. This social network, which according to Shakespeare Günther was firmly integrated in Stratford, consisted of influential, very wealthy and educated citizens with demonstrable connections to London, the courts and the court.

- ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here pp. 365f. See also in detail Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 150-153, here especially p. 152.

- ↑ See Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 166f.

- ↑ See in detail Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 161-164, especially p. 152 and pp. 164f.

- ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A citizen's life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345-376, here p. 369. See also in detail Ina Schabert (ed. ): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 164-167, especially pp. 164f.

- ↑ See in detail Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 164-167, especially pp. 165f. See also in detail Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 369-373 here especially pp. 369-371.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A citizen's life: William Shakespeare, pp. 345–376, here p. 369. See also detailed Ina Schabert (ed.) : Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 164-167, especially pp. 166f.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 168. See Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A civil life: William Shakespeare, p. 370 f. See also EAJ Honigmann: Shakespeare Will and the Testamentary Tradition. In: Shakespeare and Cultural Traditions: Selected Proceedings of the International Shakespeare Association World Congress. Tokyo 1991, ed. by Tetsuo Kishi, Roger Pringle, and Stanley Wells (Newark: University of Delaware, 1994), pp. 127–137, esp. pp. 132ff. See also Günter Jürgensmeier (ed.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86971-118-8 , p. 21. In contrast to Honigmann, Jürgensmeier assumes that Shakespeare's wife either under English common law or through the self-evident entitlement to support her daughter Susanna after his death was materially secured even without further testamentary dispositions.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum: The Elizabethan Age. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1998 (first edition 1989), ISBN 3-15-008622-1 , Chapter 3: A bourgeois life: William Shakespeare, pp. 369f.

- ↑ Mary Edmond: "It was for Gentle Shakespeare Cut". In: Shakespeare Quarterly. Vol. 42, 1991, pp. 339-344.

- ↑ Charlotte Higgins: The only true painting of Shakespeare – probably ( memento of 12 July 2012 in the archive.today web archive )

- ↑ Marie-Claude Corbeil, The Scientific Examination of the Sanders Portrait of William Shakespeare. ( Memento of 20 April 2011 at Internet Archive ) Canadian Conservation Institute, 2008.

- ↑ Tarnya Cooper (ed.): Searching for Shakespeare . With essays by Marcia Pointon , James Shapiro and Stanley Wells. National Portrait Gallery/ Yale Center for British Art, Yale University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 180f. See also Maybe a Picture of a Picture by Shakespeare . In: The World . February 12, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ↑ See Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 373–376.

- ↑ Manfred Scheler: Shakespeare's English. A linguistic introduction . (Fundamentals of English and American Studies, 12). Schmidt, Berlin 1982, p. 89 (counting according to lexemes, not word types). Different calculation bases lead to different numbers. The common figures of 29,066 given by Marvin Spevack ( A complete and systematic Concordance to the works of Shakespeare , Vol. 4, Hildesheim 1969, p. 1) and 31,534 given in a study by Bradley Efron and Ronald Thisted ( Estimating the Number of Unseen Species: How Many Words did Shakespeare Know? In: Biometrika. Volume 63, 1976, pp. 435-447) is due to the fact that the authors count inflected word forms and orthographic variants as separate words .

- ↑ David and Ben Crystal: Shakespeare's Words. A Glossary and Language Companion ( Memento of 28 June 2010 at the Internet Archive ) . Penguin, London 2002.

- ^ Cf.: Wolfgang Clemen : The Development of Shakespeare's Imagery . Routledge, London 1977, ISBN 0-415-61220-9 .

- ↑ Fausto Cercignani : Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1981, ISBN 0-19-811937-2 .

- ↑ See, for example, the articles in Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells (eds.): Shakespeare Beyond Doubt – Evidence, Argument, Controversy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2013, pp. 63-120. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. 2015 edition, pp. 13–27, especially pp. 20 and 24. See also Michael Dobson : Authorship Controversy . In: Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells: The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Second Edition, Oxford University Press 2015, p. 21 f.

- ↑ The history of the "authorship question" is given in the work of Samuel Schoenbaum: Shakespeare's Lives . New edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1991. See also David Kathman: The Question of Authorship. In: Stanley Wells, Lena Cowen Orlin (eds.): Shakespeare. An Oxford Guide . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003, pp. 620-632; Ingeborg Boltz: Authorship Theories . In: Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time - man - work - posterity . 5th through and supplemented edition, Kröner-Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, pp. 185-194.

- ↑ The reluctance of academic Shakespearean scholarship to the problematization of authorship is described in Thomas A. Pendleton: Irvin Matus's Shakespeare, In Fact. In: Shakespeare Newsletter. No. 44 (Summer 1994), pp. 26–30.

- ↑ Cf. Irvin Leigh Matus: Shakespeare, In Fact. Continuum, New York 1999, Author's Preface , p. 9 ff. and Chapter 1, Section: Is it Important? , pp. 14–18, and Irvin Leigh Matus: Reflections on the Authorship Controversy (15 Years On). In which I answer the question: Is it Important? (online) ( Memento of 24 April 2017 at the Internet Archive ). Despite his fundamental misgivings about the way the “anti-Stratfordians” argue and the methodical approach, Matus advocates a more open debate, which in some areas could also be beneficial for academic discourse. See also David Chandler, Historicizing Difference: Anti-Stratfordians and the Academy. In: Elizabethan Review. 1994 (online) ( Memento of 6 May 2006 at the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Alexander Pope speaks in the preface to The Works of Shakespear. In Six Volumes. Vol. I, Printed for J. and P. Knapton, London 1745, p. xvi from the popular opinion of his want of learning .

- ↑ That before Delia Bacon a certain James Wilmot is said to have represented the Bacon thesis as early as the 18th century, James Shapiro has in Contested Will. Who Wrote Shakespeare? (Faber & Faber, London 2011, pp. 11-14) proven to be a fake.

- ↑ Hans Wolffheim: The discovery of Shakespeare, German testimonies of the 18th century . Hamburg 1959. Günther Ercken also reports in detail on the reception in Germany in: Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. 4th edition. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 635-660.

- ↑ Edmund Stadler, Shakespeare and Switzerland , Theaterkultur-Verlag, 1964, p. 10.

- ↑ Ernst Leopold Stahl , Shakespeare and the German Theater , Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 1947.

- ↑ Cf. Friedrich Theodor Vischer's Shakespeare lectures. 2nd Edition. Stuttgart/ Berlin 1905, p. 2: “The Germans are now used to regarding Shakespeare as one of our own. [...] Without being ungrateful to England, which gave us this greatest of all poets, we can proudly say that the German spirit was the first to recognize Shakespeare's character more deeply. He also freed the English from the old prejudice that Shakespeare was a wild genius.”

- ↑ Rolf Badenhausen : Laudation for the exhibition Shakespeare and the German Theater in Heidelberg Castle, June 6 – October 11, 1964 (exhibition in Bochum: April 23 – May 10). Digitized manuscript (excerpt): https://www.badenhausen.net/dr_rolfb/manuscripts/rbi_lec-229_HD1964-6.pdf Introduction in the exhibition catalog (p. 7-8): https://www.badenhausen.net/dr_rolfb/ manuscripts/rbi_intro-229_sp1964-04.pdf

- ↑ As of 2020, 38 volumes have been published, the final volume with the sonnets is announced for autumn 2021.

- ↑ Lutz D. Schmadel : Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition. Editor: Lutz D. Schmadel. 5th edition. Springer Verlag , Berlin/ Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 3-540-29925-4 , p. 186 (English, 992 p., link.springer.com [ONLINE; retrieved September 28, 2019] Original title: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . First edition: Springer Verlag, Berlin/ Heidelberg 1992): “1983 TV 1 . Discovered 1983 Oct. 12 by E. Bowell at Anderson Mesa.”

- ↑ Paul Werstine, Shakespeare More or Less: AW Pollard and Twentieth-Century Shakespeare Editing. In: Florilegium. Volume 16, 1999, pp. 125-145.

- ↑ Christa Jansohn: Doubtful Shakespeare. On the Shakespeare Apocrypha and their Reception from the Renaissance to the 20th Century . (= Studies in English literature. Volume 11). Lit, Munster et al. 2000

- ↑ Brian Vickers: Shakespeare, co-author. A historical study of five collaborative plays . Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford et al. 2004

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Shakespeare, William |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English playwright, poet and actor |

| BIRTH DATE | baptized April 26, 1564 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stratford upon Avon |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 3, 1616 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Stratford upon Avon |