William Shakespeare authorship

William Shakespeare Authorship deals with the debate that has been going on since the 18th century as to whether the works ascribed to William Shakespeare (1564–1616) of Stratford-upon-Avon were in fact written by another author or by more than one author.

Those who doubt William Shakespeare's authorship argue that there is a lack of concrete evidence that the Stratford actor and businessman was responsible for the literary work that bears his name. There are too great gaps in the historical records of his life and no letter written to him or by him has been received or known. His detailed will does not mention any of his shares in the Globe and Blackfriars Theaters , nor does it mention any books, plays, poems or other writings from his hand.

In fact, almost nothing is known about his personality, and although much about the historical person may be indirectly inferred from his plays, he remains a puzzling person due to a lack of solid life-world information about himself. John Michell noted in Who Wrote Shakespeare (1996) that "the known facts about Shakespeare's life ... could be written on a piece of paper". He also quoted Mark Twain's satirical comment on it in Is Shakespeare dead? (1909).

Literary scholars do not consider this lack of information astonishing in view of the distant past and the generally incomplete documentation of the lives of non-aristocrats or non-upper-class people from that time. They point out that historical information about many other people in the Elizabethan theater is patchy. That is why the debate does not play a significant role in serious literary studies. Stephen Greenblatt , one of the leading Shakespeare experts, wrote in around 2005 that there was "an overwhelming scientific consensus" on authorship.

Another reason for doubt that is often mentioned is the general education recognizable in the Shakespeare works, which the author must have had, documented primarily by the enormous vocabulary of around 29,000 different words, almost six times as much as that in the King James' Bible that gets by with 5,000 different words. Many critics consider it difficult to assume that a person of the 16th century from a social class below the nobility could have been so well-versed in English or even in foreign languages after the historically recognizable schooling that Shakespeare enjoyed, recognizable above all by the fact that the works contain specialist vocabulary from the fields of politics, law or horticulture. There is no evidence of attending at least one grammar school or university. Authorship doubters therefore believe that the information available about Shakespeare's life does not provide sufficient evidence that the Stratford historical theater man Shakespeare was able to write the works ascribed to him. They therefore propose that other, more suitable persons of this time period should be considered as probable author of Shakespeare's works into consideration, and assume that Shakespeare only a " straw man war" ( "frontman") for the true author wanted to (or had to) remain anonymous.

For nearly 200 years, Francis Bacon was the leading alternative candidate. Various other candidates were also proposed, including Christopher Marlowe , William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford . As the most popular theory among anti-Tratfordians in the 20th century, the notion that Shakespeare's works could have been written by Edward de Vere emerged. Although classical literary studies have so far rejected all theories for alternative candidates, interest in the authorship debate has increased, especially among independent scholars, theater professionals and non-philologists ( Friedrich Nietzsche , Otto von Bismarck and Sigmund Freud are among the more well-known doubters), a trend that will continue in the 21st century.

Overview

Established view

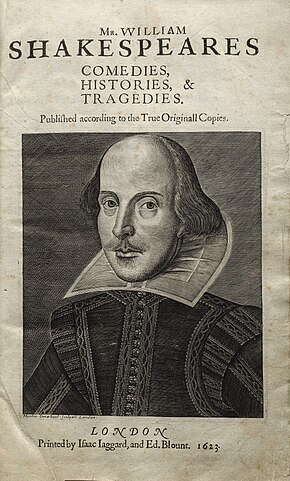

Within the established literary scholarship, the following facts are considered certain: William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564 , moved to London and became a poet, playwright, actor and sharer of the well-known theater company Lord Chamberlain's Men ( later the King's Men ) who owned the Globe Theater and Blackfriars Theaters in London . He moved back and forth between London and Stratford and retired to Stratford around 1613, a few years before his death in 1616. Shakespeare's name appeared on fourteen of the fifteen works published before his death. In 1623, after most of the alternative candidates had died, his pieces were compiled for publication in the First Folio Edition. The actor was identified with the author by the following additional evidence:

- a) Shakespeare from Stratford left gifts in his will for actors of his London theater company,

- b) the Stratford man and the works author have the same name, and

- c) There are poems referring to Shakespeare's works in the First Folio , which refer to a swan from Avon ("Swan of Avon") and his tomb (his "Stratford monument").

The majority of scholars assume that with the sentences in question Shakespeare's tomb in Stratford in Holy Trinity Church is meant, which is clearly characterized as that of a writer ("writer"); he is compared to Virgil , and his works are referred to as "living art".

Further references support the "Stratfordian" view:

- In the pamphlet "Greene's Groatsworth of Wit", written by Robert Greene in 1592, Greene scolded a playwright whom he derided as a "shake-scene", an "upstart crow" and a jack-of -all-trades , a man who doesn't have skills, but only pretends:

For there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and beeing an absolute Johannes fac totum, is in his owne conceit the onely shake scene in a countrey. (Because there is a crow that has come up, finely dressed up with our feathers, which, with its tiger heart hidden in an actor's robe, thinks it can pour out blank verse like the best of you: and he comes to himself as an absolute jack-of-all-trades as the only theatrical shaker in the country)

that suggests contemporaries knew about a writer named Shakespeare. - The poet John Davies of Hereford once referred to a "Shakespeare" as "our English Terence " during Shakespeare's lifetime .

- Shakespeare's funerary monument in Stratford, built within a decade of his death, depicts him at a desk with a quill in hand. So he was characterized as a writer (although there has been scholarly debate as to whether the tomb should be at a later date Time was changed).

Authorship doubters

For those who doubt authorship, there are indications from various sources that Shakespeare by Stratford was just a straw man for another, as yet undiscovered playwright: These are both perceived ambiguities and a lack of information from historical sources that, in their eyes, cast doubts on Shakespeare Establish authorship, as well as the observation that his pieces reflect a level of education that (including foreign language skills) is considerably higher than Shakespeare's schooling would suggest. The doubters also cite hints from contemporary authors that the potential author may have been dead while Stratford's Shakespeare was still alive; there are also hidden references to the content of sources and to persons to whom Stratford Shakespeare had no access and who therefore suggested another author or candidate.

terminology

"Anti-Stratfordians"

Those who question William Shakespeare of Stratford as the author of Shakespeare's works usually call themselves "anti-Stratfordians." Those who consider Francis Bacon , Christopher Marlowe or the Earl of Oxford to be the lead author of Shakespeare's plays are commonly referred to as Baconians , Marlowians or Oxfordians .

"Shakespeare" versus "Shakespeare"

In Elizabethan England there was no standardized orthography, especially not a proper name, which is why one encounters his name in various phonetic spellings (including "Shakespeare") during Shakespeare's lifetime. Anti-Stratfordians usually refer to the Stratford man as "Shakespeare" (as his name appears in the baptismal and death records) or as "Shaksper" to distinguish him from the writer "Shakespeare" or "Shakespeare".

Anti-Stratfordians also point out that the vast majority of contemporary references to the Stratford man in public documents usually write him in the first syllable without the "e" as "Shak", or occasionally as "Shag" or "Shax" during the Dramatist is consistently spelled with a long "a" as "shake". Stratfordians reject this convention presumption, that is, they doubt that the Stratford man spelled his name differently from the editors of the books. Since these so-called "Shakespeare" conventions are controversial, the name in this article is always written after the current convention "Shakespeare".

The idea of secret authorship in Renaissance England

"Anti-Stratfordians" point to examples of anonymous or pseudonymous publications by Elizabethan contemporaries of high social standing in support of the possibility that Shakespeare was a straw man. In his description of contemporary writers and playwrights, Robert Greene wrote that “Others… if they come to write or publish anything in print, it is either distilled out of ballets [ballads] or borrowed of theological poets which, for their calling and gravity, being loth to have any profane pamphlets pass under their hand, get some other Batillus to set his name to their verses. ” (“ With others, when they have something written or printed, it is either drawn from ballads or borrowed from theological poets who Because of their reputation and dignity, they do not want to have secular pamphlets printed under their names and therefore find another Bathyllus who puts his name under their verses. ”) Bathyllus was known for having passed the verses of Virgil to the emperor Augustus as his own . Roger Ascham , in his book The Schoolmaster, discusses the belief that two plays ascribed to the Roman playwright Terence were secretly written by “worthy Scipio, and wise Lælius” because the language was too sublime to be spoken by a “servile stranger ”(Terence came from Carthage and came to Rome as a slave, his African name is unknown) as Terence could have been written.

Common Arguments of the Anti-Stratfordians

Shakespeare's education

Against the under-education argument put forward by the anti-Statfordians, Stratfordians object that Shakespeare was entitled to attend The King's School in Stratford until the age of fourteen, where he also studied Latin playwrights and poets such as Plautus and Ovid . However, since there are no records of this, it can no longer be proven today whether Shakespeare actually attended this school. There are no sources whatsoever that Shakespeare ever attended university, although this was not uncommon among Renaissance playwrights. It is believed that Shakespeare was partly self-taught .

The playwright Ben Jonson is often cited as a similar case. He came from an even lower social class than Shakespeare and yet rose to become a court poet. Similar to Shakespeare, Jonson never went to university and yet became an educated person who was later awarded an honorary degree from both universities ( Oxford and Cambridge ). In addition, Jonson had access to libraries that helped him develop his education. A source for Shakespeare's possible self-education was suggested by AL Rowse, who noted that some of the sources for his pieces were sold in the "Printers Shop" by Richard Field, a Stratfordian student Shakespeare's age.

Stratfordians noted that Shakespeare's works do not require an unusual level of training from the start: Ben Jonson's contribution to Shakespeare's First Folio 1623 states that his plays are significant, although he only had “small Latin and less Greek” . It has also been argued that much of its classical formation can only be derived from a single text, Ovid's Metamorphoses , which was a canonical text in many contemporary schools. Anti-Stratfordians, on the other hand, point out that this does not explain where the author got his knowledge of foreign languages, modern science, martial arts, law, and aristocratic sports such as tennis, hunting and falconry.

Shakespeare's Testament

William Shakespeare's will is long and detailed, it lists in detail the possessions of a successful citizen. Anti-Stratfordians find it remarkable that his will nowhere mentions possession of personal papers, letters, or books of any kind (books were rare and expensive possessions at the time). Likewise, no poems, manuscripts or unfinished work, correspondence or papers are listed, nor are there any references to his valuable holdings in the Globe Theater.

In particular, anti-Stratfordians point out that when Shakespeare's death eighteen of his plays had not yet been published and yet no literary work and none of these plays were mentioned in his will, which is in contrast to, for example, Sir Francis Bacon's two wills, which are also refer to works that he only wanted to have published posthumously. Anti-Stratfordians also find it unusual that Shakespeare did not express in the will that his family should benefit (financially) from his unpublished works, and that he was obviously not interested in bequeathing to posterity. They also consider it unlikely that Shakespeare should have given all of his manuscripts to the King's Men theater company, where he himself was a partner. Because at that time it was common for plays intended for a theater group to be owned jointly by the author and the theater company. There were two associates in the company, John Heminge and Henry Condell , whose names were mentioned in the 1623 First Folio attribution.

The problem of 1604

Some anti-Stratford researchers believe that certain documents suggest that the real author was dead as early as 1604, the year in which the continuous production of new Shakespeare plays "mysteriously" ceased, and that numerous anti-Stratfordian researchers believe that A Winter's Tale , The Storm , Henry VIII. , Macbeth , King Lear and Antonius and Cleopatra , so-called "later pieces", were not written after 1604. Scholars cite the first print of Shakespeare's Sonnets from 1609, in the apparent dedication of which appears the passage "our ever-living Poet", and emphasize that the words "ever-living" were very rarely, if ever, applied to a living person - words that typically honor someone who has died and become "immortal" after death. A contemporary source is also cited to suggest that Shakespeare, the partner in the Globe theater, died before 1616.

Shakespeare's literacy

Anti-Stratfordians argue that Shakespeare's last signatures in particular (see the adjacent figure) are so awkward that they stand in the way of the undersigned's extensive literary activity. The anti-Stratfordians also note that there is no surviving letter from or to Shakespeare. They point out that a man of Shakespeare's writing skills should have written numerous letters. No other documents written by Shakespeare have survived, and not a single original of his works has survived.

It should also be noted that Shakespeare's wife Anne Hathaway and at least one of the two daughters (Judith) were proven to remain illiterate, from which it can be inferred that Shakespeare had not taught them to write. However, Shakespeare's older daughter Susannah was able to provide signatures. The majority of Shakespeare researchers, on the other hand, hold the view that illiteracy was normal for middle-class women in the 17th century.

Shakespeare's reputation

Anti-Stratfordians believe that the son of a provincial glove maker who resided in Stratford until his early adulthood is unlikely to have written the plays that deal with activity, travel, and life in such a personal way have discussed at court. This view was published by Charles Chaplin : “In the work of greatest geniuses, humble beginnings will reveal themselves somewhere, but one cannot trace the slightest sign of them in Shakespeare. Whoever wrote Shakespeare had an aristocratic attitude. ”Orthodox scholars respond that the“ glamorous ”world of the aristocracy was the most popular backdrop for plays of this age. They add that numerous English Renaissance writers - including Christopher Marlowe , John Webster , Ben Jonson , Thomas Dekker, and others - wrote about the aristocracy despite their lowly origins. Shakespeare was also an "open-minded" person: his theater group played regularly at court, and he was therefore given ample opportunity to observe court life. In addition, his theater career made him wealthy, so that he was able to acquire a coat of arms and the title of "gentleman" for his family like many other wealthy middle-class people at that time.

In The Genius of Shakespeare , Jonathan Bate emphasizes that the class argument is reversible: the plays contained details of lower-class life that nobles had little insight into. Many of Shakespeare's liveliest characters are from the lower class or can be associated with this milieu, such as: B. Falstaff, Nick Bottom, Autolycus, Sir Toby Belch.

Anti-Stratfordians believe that Shakespeare's treatment of the rural population, including comedic and hurtful names (such as Bullcalfe, Elbow, Bottom, Belch, often portrayed as "the butt of jokes or as an angry mob") was markedly different from the treatment of the nobility, which turned out to be much more personal and complex. Stratfordians also suggested that Shakespeare was not considered an expert of the court, but a child of nature in the 17th century ("Warbled his native wood-notes wild", as John Milton put it in his poem L'Allegro ). In fact, John Dryden wrote in 1668 that the playwrights Beaumont and Fletcher could understand and imitate the conversations of “gentlemen” better than Shakespeare, and in 1673 about playwrights of the “Elizabethan” era in general: “any of them had been conversant in courts, except Ben Jonson ”(“ Each of them had courtly company, with the exception of Ben Jonson ”). For example, since it took Ben Jonson (who himself came from the lower class) twelve years after his first play to receive nobility patronage from Prince Henry for his commentary on The Masque of Queens (1609), anti-Stratfordians doubt that a still unknown Shakespeare was made Stratford the patronage of the Earl of Southampton for one of his first published works, the long verse epic Venus and Adonis (1593), so it could have received very quickly.

Comments from contemporaries

Contemporary writers' comments on Shakespeare can be interpreted as expressing their doubt about his authorship. So Ben Jonson had a contradicting relationship with Shakespeare. On the one hand, he regarded him as a friend when he wrote "I loved the man" in 1637 - and praised him in the 1623 First Folio. On the other hand, Jonson called Shakespeare “too wordy”. Commenting on the praise of fellow actors for never correcting a line, he wrote: “would he had blotted a thousand” and that he “flowed with that facility that sometimes it was necessary he should be stopped ”(“ the words gushed out of him in such a way that it was sometimes necessary to interrupt him ”).

In the same text (published 1641) Jonson mocked a line from Shakespeare in which he wrote about the person Caesar (presumably in his play ) "Caesar never did wrong but with just cause" ("Caesar never did wrong but with just cause") , which Jonson found stupid, and indeed Jonson's text in 1623 in the First Folio contains a different line: “Know, Caesar doth not wrong, nor without cause / Will he be satisfied” (“Caesar does no wrong, least of all for nothing because he wants to stand before himself ”(3.1.47-48)). Jonson also made contempt for this line in his play The Staple of News , without referring directly to Shakespeare. Some anti-Stratfordians interpret these ratings as expressing a doubt about Shakespeare's ability to write these plays.

In Robert Greene's posthumous publication Greene's Groatsworth of Wit (published 1592, possibly written by the playwright Henry Chettle ), a playwright named "Shake-scene" is quoted as an upstart Crowe beautified with our feathers Henry VI. (Part 3) ridiculed (quoted in the overview above). The orthodox view is that Greene criticizes the relatively uneducated Shakespeare for entering the realm of the university-trained playwright Greene. Some anti-Stratfordians believe that Greene is actually questioning Shakespeare's authorship. In Robert Greene's earlier work Mirror of Modesty (1584) the attribution “Ezops Crowe, which covers hir selfe with others feathers” is mentioned as a reference to Aesop's fable the crow, the hedgehog and the feathers that go against people who pretend they have what they don't. In John Marston's satirical poem The Scourge of Villainy (1598), Marston turns against the upper class, which is described as polluted by their sexual contact with the lower class. Spiced with sexual imagery, Marston asks:

Shall broking pandars sucke nobility?

Soyling fayre stems with foule impuritie?

Nay, shall a trencher slaue extenuate,

Some Lucrece rape ?. And straight magnificate

Lewd Jovian Lust? Whilst my satyrick vaine

Shall muzzled be, not daring out to straine

His tearing paw? No gloomy Juvenall,

Though to thy fortunes I disastrous fall.

(Translation roughly: Should decrepit matchmakers associate themselves with the nobility? Should tainted beauty wrestle with foul smelling impurity? Yes, should a slave glorify the desecration of a Lucretia? And thus promote the lust of a horny Jupiter? During my satirical vein, the mouth should be stuffed, because no one dares to stop his slamming paw? No, gloomy Juvenal, I would share your cruel fate.)

According to tradition, the Roman satirical poet Juvenal was exiled by Domitian for mocking an actor with whom the emperor was in love, and in exile he became very gloomy. Marston's poem could have been directed against an actor, so to speak, as a question of whether such a lowly standing slave (trencher slave, who digs trenches) played down the desecration of Lucretia ( Rape of Lucrece ) in Shakespeare's poem of the same name. The opening lines would then be referred to by Shakespeare, who wrote such a poem Lucretia , as "broking pandar" ("seedy pimp"), who in the lowest way ingratiated himself with the nobility ("suck nobility"), perhaps an allusion to that with the poem won patronage of the Earl of Southampton. In addition, the word “pandar” comes from Shakespeare's play Troilus and Cressida (it meant “pimp” back then, now “pimp”). It is an originally Italian word that entered the English language through Shakespeare.

Notes in the poems

Anti-Stratfordians like Charlton Ogburn have repeatedly used Shakespeare's sonnets as evidence of their position. You quote e.g. B. Sonnet 76 as an obviously tricky admission by the author:

Why write I still all one, ever the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed,

That every word doth almost tell my name,

Showing their birth, and where they did proceed?

("Why do I always only write one thing, always the same, and put the invention in a familiar dress that every word almost says my name, what it gave birth to, the words, and what they grew from?")

Geographic knowledge

Most anti-Stratfordians assume that the plays must have been written by a polyglot author, as many take place in European countries and show a strong attention to local detail. They assume that such local information must have been obtained firsthand on the spot and come to the conclusion that the author of the plays could or must have been a diplomat, an aristocrat or a politician. Scholars respond that numerous contemporary plays by other playwrights are also set in other countries and that Shakespeare is nothing extraordinary in this regard. In addition, Shakespeare has in many cases borrowed the description of the place from sources.

Beyond the question of authorship, a debate developed about the extent of geographical knowledge that is expressed in Shakespeare's plays. Some scientists argued that it in the lyrics at all just give topographical information (nowhere in Othello or the Merchant of Venice were Venetian canals mentioned). There are actual noticeable errors, e.g. For example, in the play A Winter's Tale , Shakespeare referred to a Bohemia with a sea coast, but it is well known that Bohemia is only surrounded by land. Shakespeare referred Verona and Milan in the play Two Gentlemen from Verona to seaports, but the cities are inland, in the play Ending Well, All Well , he meant that a trip from Paris to Northern Spain must touch Italy , and in the play He speaks to Timon of Athens that there are ebb and flow of tides in the Mediterranean and that they only happen once a day instead of twice. Answers to such objections have come from a variety of sources (both scientists and "anti-Stratfordians"). In individual other cases, such as in The Merchant of Venice, there is detailed local knowledge of the city at that time. B. the native word "traghetto" for the Venetian shipping traffic as a traject in the published text.

In all cases, however, the essential fact was overlooked that such geographical errors were already present in Shakespeare's sources or in Robert Greene's Pandosto and were therefore only repeated in the pieces - which, however, also speaks against the theory of one's own view.

Scientists believe that Shakespeare's plays contained various geographically bound names for a particular flora and fauna that were only valid for the county of Warwickshire , in which Stratford-upon-Avon is located, e.g. B. love in idleness in the Midsummer Night's Dream for the Wild Pansy (Viola tricolor).

Such names suggested that a Warwickshire native might have written these pieces. Supporters of the Oxford Thesis pointed out that de Vere owned a country house in Bilton , Warwickshire, although sources show that he rented the house in 1574 and sold it in 1581 .

Candidates

History of alternative assignments

The first indirect references to suspect authorship of Shakespeare's work came from Elizabethan contemporaries themselves. As early as 1595, the poet Thomas Edwards published his work Narcissus and the L'Envoy (Announcement) on Narcissus , in which he clearly states that Shakespeare must have been an aristocrat. Edwards referred to the poet of Venus and Adonis as someone who was "dressed in purple robes", purple-violet here understood as a symbol of the aristocracy. The Elizabethan satirist Joseph Hall (1597) and his contemporary John Marston (1598) suggested that Sir Francis Bacon was the author of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece . At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Cambridge scholar Gabriel Harvey left marginalia in his copies of Geoffrey Chaucer's work, suggesting that he believed Sir Edward Dyer was at least the author of Venus and Adonis . However, all of these references were only veiled indications of the authorship issue, not explicit claims.

The first direct references to a doubt about Shakespeare's authorship came in the eighteenth century when unorthodox views of Shakespeare were expressed in three different allegorical narratives. In an essay Against Too Much Reading (1728) by Captain Golding, Shakespeare is portrayed as a pure collaborator who “in all probability could not write English” (“in all probability could not write English”). In the work The Life and Adventures of Common Sense (1769) by Herbert Lawrence Shakespeare is characterized as a "shifty theatrical character ... and incorrigible thief" ("devious theater character and incorrigible thief"). In The Story of the Learned Pig (1786), written by an unknown author, Shakespeare is described as "an officer of the Royal Navy" who was used solely as a "straw man" for the real author, a person named "Pimping Billy “(A sexual innuendo, Billy for William).

During this time the learned clergyman James Wilmot of Warwickshire was researching the biography of Shakespeare. He toured extensively the Stratford on Avon area, visiting libraries and libraries of country houses within about fifty miles to look for sources, letters, and books relating to Shakespeare. By 1781, Wilmot was so dismayed by the lack of documentary mentions of Shakespeare that he concluded that Shakespeare could not be the author of the Shakespeare work. Knowing the works of Sir Francis Bacon, Wilmot decided that Bacon must probably be the actual author. He reported this to a certain James Cowell, who then presented the thesis to the Ipswich Philosophical Society in 1805 (Cowell's manuscript was not rediscovered until 1932).

All these assumptions and investigations were soon forgotten again. As part of the increasing admiration for Shakespeare, Sir Francis Bacon did not step into the limelight again until the 19th century and was much more emphatic as an alternative candidate.

Many of those who doubted authorship in the 19th century claimed to be "agnostics" and were unwilling to support a specific alternative candidate. The popular American poet Walt Whitman formulated his skepticism, which he shared with Horace Traubel, as follows: “I go with you fellows when you say no to Shaksper: that's about as far as I have got. As to Bacon, well, we'll see , we'll see. "

From 1908 onwards, Sir George Greenwood led a lengthy debate with Shakespearean biographers such as Sir Sidney Lee and JM Robertson . With his numerous books on the question of authorship, he tried to fight against the prevailing opinion that William Shakespeare was the author of the Shakespeare work, but initially did not come to the final support of a certain alternative candidate. In 1922 he joined John Thomas Looney, who first advocated the authorship of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, by supporting "The Shakespeare Fellowship," an international organization dedicated to discussing and promoting the authorship debate would have. In 1975 the "Encyclopedia Britannica" declared that de Vere was probably the most likely alternative candidate for authorship. Support for Oxford authorship has been growing since the 1980s.

The poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe has also become a popular candidate in the 20th century. Various other candidates - including De Vere's son-in-law William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby - have been proposed as candidates, but have not yet had a large following.

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Perhaps the most popular current candidate is Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford , first proposed in 1920 by J. Thomas Looney. This theory had already found various famous followers in the 1920s such as Sigmund Freud , Orson Welles , Marjorie Bowen and many other intellectuals in the early 20th century. The Oxford theory gained more popularity in 1984 with Charlton Ogburn's book The Mysterious William Shakespeare , whereupon Oxford quickly rose to become the most important alternative candidate. Oxfordians base their theory on the circumstances of numerous and striking similarities or similarities between the Oxford biography and events in Shakespeare's plays. They point to contemporary references to Oxford, to his talent as a poet and playwright, to his closeness to Queen Elizabeth I and to court life, to the underlines in Oxford's Bible, which they believe to be related to Shakespeare's content in his plays correspond to sentence and thought similarities between Shakespeare's works and Oxford's surviving letters and poems, to his high level of education and intelligence, to his travel reports about Italy including many places of the Shakespeare plays. Stratfordian supporters question most of these arguments. For Stratfordians, the most convincing evidence against Oxford is that he died as early as 1604, while they believe that a number of Shakespearean plays may not have been written until after Oxford's death in 1604. Anti-Stratfordians counter this by stating that the exact times at which the pieces and poems were written are not known or can be reconstructed with certainty. More recent research results from the textual science or critical editions, which in the case of pieces such as Macbeth , The Winter's Tale or Henry VIII, provide clear indications such as current allusions or intertextual references, which exclude an earlier dating of these pieces and fundamental changes in the chronology of Shakespeare's works, try to guess to refute that de Vere had already prefabricated those pieces during his lifetime. After his death, these works were only later taken from his estate and updated accordingly before they were published. The Tempest , which in several places contains clear references to the news of the sinking of the flagship Sea Adventure off the coast of Bermuda at the end of July 1609, which did not reach England until 1610, and which for other largely undisputed reasons could not have been made before 1610, is inconsistent to be classified in the context of the Oxford Hypothesis and is therefore mostly classified by the Oxfordians as a secondary work, which may not be attributed to Shakespeare's authorship at all.

In addition, from a literary point of view, it is argued against the Oxford hypothesis that Oxford's published poems show no stylistic similarities to the works of Shakespeare. Oxfordians, however, argue that the Oxford poems were those of a very young man and support their arguments by comparing Oxford's poetry and Shakespeare's “early” works such as Romeo and Juliet .

In the German-speaking countries, a group of supporters of the Oxford hypothesis has recently emerged since the mid-1990s, which from 1997 to 2008 published the annual New Shake-Speare Journal . In March 2010 this group founded the “New Shake-speare Society” ; Since 2012 the annual volumes of this society have been published under the title Spectrum Shake-speare .

The American Shakespeare scholar and author Irvin Leigh Matus, on the other hand, tried to comprehensively refute the theses and assumptions of the Oxfordians in his research work, which he had also essentially published since the 1990s in various specialist articles and in book form.

Sir Francis Bacon

In 1856, the politician William Henry Smith asserted that Sir Francis Bacon , a contemporary of Shakespeare and famous scientist, philosopher, courtier, diplomat, essayist, historian and influential politician, was the author of Shakespeare's works. Bacon also served as "Solicitor General" (1607), Crown Attorney General (1613) and Lord Chancellor (1618). Smith was assisted by Delia Bacon in her book The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded in 1857 . She claimed that it was a group of writers (Francis Bacon, Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser ) who had shared responsibility for Shakespeare's work for the purpose of spreading a philosophical moral system, which a single member of the group did not have been able to take on. Delia Bacon believed to have discovered such a system on a second level of meaning in the dramatic texts. Constance Mary Fearon Pott (1833-1915) came to a modified point of view, founded the "Francis Bacon Society" in 1885 and published a Bacon-centered authorship theory in her book Francis Bacon and his secret society in 1891 .

Delia Bacon argued that the drama was already used as a means of educating men's minds to virtue in ancient times. Another hypothesis assumed that Francis Bacon acted alone and left his moral philosophy for posterity in the Shakespeare plays. Although in his Advancement of Learning (1605) he also treated morality in addition to the philosophy of science, only his scientific methodology was published during Bacon's lifetime ( Novum Organum 1620). Francis Carr even claimed that Francis Bacon wrote both Shakespeare's works and the novel Don Quixote by Cervantes .

Supporters of the Bacon theory particularly pointed out similarities between special sentences and idioms of the Shakespeare plays and sentences and those of Francis Bacon in his notebooks "The Promus". They were unknown to the public for more than 200 years. Numerous entries in these notebooks, often made at the same time as the publication or performance of Shakespeare plays, would later have found their way into the Shakespeare plays. Bacon also admitted in a letter that he was a "hidden" poet, "a concealed poet". Bacon was also a member of the governing council of the Virginia Company when William Strachey's letters from the Virginia colony in England arrived, reports of shipwrecks that some scholars consider to be sources for Shakespeare's play The Tempest (see below).

In Germany, Nietzsche was fascinated by the theory of Baconian authorship and flirted ironically with it, for example when he wrote in his autobiography Ecce Homo :

“And that I confess it: I am instinctively sure and certain that Lord Bacon is the author, the self-torturer of this most sinister kind of literature: what do I care about the pitiful chatter of American confused and flat-headed people? But the power to the most powerful reality of the vision is not only compatible with the most powerful power to the deed, the monstrous deed, the crime - it presupposes itself [...] Suppose I had baptized my Zarathustra in a strange name, for example on that of Richard Wagner , the acumen of two millennia would not have been enough to guess that the author of " Human, All Too Human " is the visionary of Zarathustra [...] "

Another well-known representative in Germany was the mathematician Georg Cantor .

Edwin Bormann , who expressed this opinion in numerous publications around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries , also appeared as a vehement advocate of Bacon's authorship . He believed to have proven that findings from the scientific and philosophical writings of Bacon, some of which were only accessible posthumously, can be found in individual dramas by Shakespeare.

One of the last committed representatives of the thesis that Bacon wrote Shakespeare's works for the time being was the German writer Erna Grautoff. To explain her assumption in detail, she wrote a novel, and a scientifically intended accompanying text Grautoff even goes so far as to assume that Francis Bacon was a son of Elizabeth I and that in some of his sonnets his mother asked him to be his biological son and about it to publicly recognize natural successors on the throne. Grautoff translated 42 sonnets from Shakespeare for her novel .

Literary scholars and philologists were no more convinced by the Bacon theory then than it is today. They argue that Bacon's poetry is too different from Shakespeare's style, and note that Shakespeare treats legal aspects and terms far more abstractly than the professional lawyer Bacon.

Christopher Marlowe

The gifted playwright and poet Christopher Marlowe has also become a popular candidate, although, according to contemporary sources, he died before the Shakespeare of the same age published his first work Venus and Adonis at the age of 30 . Marlowe was discussed as a candidate as early as the 19th century. The Marlowe theory only became popular in 1955 after the publication of the book by the American journalist Calvin Hofmann The Murder of the Man who was Shakespeare .

Marlowe was killed by a group of men in 1593, according to early historical gossip, including Ingram Frizer , a servant of Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe's patron saint. The Marlowe theory states that Marlowe's life was mortally threatened because of allegations of treason and heresy and could only be saved by faking his death, giving up his identity and name, henceforth in support of the crown through William Cecil, Lord Burghley who lived anonymity and wrote under various pseudonyms including Shakespeare. The pseudonym Shakespeare was theoretically chosen after 1593 because William Shakspere from Stratford in London was willing to serve Marlowe as a straw man for a fee to increase his security. Samuel Blumenfeld and Daryl Pinksen tried in their monographs, which were published independently in 2008, to comprehensively prove that Marlowe was only able to continue to live under the pseudonym Shakespeare with a foreign identity after a faked death.

The supporters of the "Marlowe theory" quote u. a. stylistic or stylometric research suggesting similarities in vocabulary and style. Literary scholars could not make friends with the argument of a “conspiratorial” death pretense of Marlowe. The style differences between Marlowe and Shakespeare are too great, the similarities are attributed to the popularity of Marlowe's works. More recent stylometric studies even assume that the stylistic similarity between Marlowe and Shakespeare arises from an error of assignment. The three parts of Henry VI and Titus Andronicus contained Marlowe signals because they were directly adjacent to the Marlowe corpus in principal component analyzes. However, this turned out not to be homogeneous. The texts in question Edward II and The Jew of Malta had no stylistic correspondence with Marlowe's Tamburlaine dramas.

More candidates

In 2007 AWL Saunders proposed a new authorship candidate, Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke (1554-1628) in The Master of Shakespeare . However, Saunders was left with this proposal alone.

In The Truth Will Out , published in 2005 , the authors Brenda James, professor at the University of Portsmouth , and William Rubinstein, professor of history at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth , believed that Sir Henry Neville (1562-1615), a contemporary English diplomat and distantly related to Shakespeare who was the author of Shakespeare's works. Neville's career took him to many of the places where Shakespeare's plays are set, and his life bore many similarities with what happened in the plays.

Other proposed candidates: Mary Sidney , William Stanley, the 6th Earl of Derby, Sir Edward Dyer or Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland (occasionally with his wife Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Philip Sidney , and his aunt Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke, as co-authors). Around fifty other candidates have also been discussed, including the Irish rebel William Nugent and Queen Elizabeth (based on a presumed similarity between a portrait of the Queen and the Shakespeare engraving in the First Folio). Malcolm X argued that Shakespeare actually King I. Jacob was.

In the 1960s, the most popular theory was that Shakespeare's plays and poems were the work of a group consisting of u. a. De Vere, Bacon, William Stanley pose. This theory has been mentioned and renewed many times, most recently by the well-known stage actor Derek Jacobi , who told the English press that he supported the "group theory": I subscribe to the group theory. I don't think anybody could do it on their own. I think the leading light was probably de Vere, as I agree that an author writes about his own experiences, his own life and personalities.

The citizen scientist Holger Lohse assumes that the duo William Stanley and Edward Dyer stood as secret authorship behind Shakespeare. In his opinion, “the deep artistic quality and the virtuoso formal quality as well as the refinement of the language” exceeded “the abilities of someone who has never attended school and was illiterate all his life.” As evidence, he sees the list of actors in the first complete edition of the dramas, the first folio.

media

The Oxfordian thesis is the subject of the film Anonymous by Roland Emmerich (2011).

literature

Established view / neutral / doubters

- Bertram Fields: Players: The Mysterious Identity of William Shakespeare. Regan Books, New York 2005, ISBN 0-06-077559-9 .

- HN Gibson: The Shakespeare Claimants. London 1962. Overview from a conservative point of view.

- George Greenwood: The Shakespeare Problem Restated. John Lane, London 1908.

- same: Shakespeare's Law and Latin. Watts & Co., London 1916.

- the same: Is There a Shakespeare Problem? John Lane, London 1916.

- the same: Shakespeare's Law. Cecil Palmer, London 1920.

- EAJ Honigman: The Lost Years. 1985.

- Irvin Leigh Matus: Shakespeare, in fact. Continuum, London 1999, ISBN 0-8264-0928-8 , new edition Dover Publications, Mineola / New York 2012, ISBN 0-4864-9027-0 . Extensive examination of the Oxford hypothesis for refutation.

- Ian Wilson: Shakespeare - The Evidence. Unlocking the mysteries of the man and his work. Headline, London 1993, ISBN 0-7472-0582-5 .

- Scott McCrea: The Case for Shakespeare. Praeger, Westport CT 2005, ISBN 0-275-98527-X .

- Bob Grumman: Shakespeare and the Rigidniks. The Runaway Spoon Press, Port Charlotte FL 2006, ISBN 1-57141-072-4 .

- Paul Edmondson, Stanley Wells (Eds.): Shakespeare beyond doubt: evidence, argument, controversy , Cambridge University Press 2013

Oxfordians

In English:

- Mark Anderson: "Shakespeare" By Another Name: The Life of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, The Man Who Was Shakespeare. Gotham Books, New York 2005, ISBN 1-59240-103-1 .

- Al Austin and Judy Woodruff: The Shakespeare Mystery. Frontline documentary, 1989 [5] . Documentary about the Oxford thesis.

- William Plumer Fowler: Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford's Letters. Peter E. Randall Publisher, Portsmouth / NH 1986, ISBN 0-914339-12-5 .

- Warren Hope, Kim Holston: The Shakespeare Controversy: An Analysis of the Claimants to Authorship, and their Champions and Detractors. McFarland and Co., Jefferson / NC 1992, ISBN 0-89950-735-2 .

- Kurt Kreiler: Anonymous Shake-Speare. The Man Behind. Dölling and Galitz, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-86218-021-9 .

- J. Thomas Looney: Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. Cecil Palmer, London 1920, Archives . The first book on the Oxford thesis. Reprint 1975.

- Richard Malim (Ed.): Great Oxford: Essays on the Life and Work of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, 1550-1604. Parapress, Tunbridge Wells 2004, ISBN 1-898594-79-1 .

- John Michell: Who Wrote Shakespeare? Thames and Hudson, London 1999, ISBN 0-500-28113-0 .

- Charlton Ogburn Jr .: The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Man Behind the Mask. Dodd, Mead & Co., New York 1984, ISBN 0-396-08441-9 . Influential book promoting the Oxford thesis.

- Diana Price: Shakespeare's unorthodox biography: new evidence of an authorship problem. Greenwood, Westport CT 2001, ISBN 0-313-31202-8 . [6] . Introduction to the problems of proof of the Oxford thesis.

- Joseph Sobran: Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time. Free Press, New York 1997, ISBN 0-684-82658-5 .

- Roger Stritmatter: The Marginalia of Edward de Vere's Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Literary Reasoning, and Historical Consequence. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Massachusetts, 2001 [7]

- BM Ward: The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford (1550-1604) From Contemporary Documents. John Murray, London 1928.

- Richard Whalen: Shakespeare: Who Was He? The Oxford Challenge to the Bard of Avon. Praeger, Westport CT 1994, ISBN 0-275-94850-1 .

In German language:

- Walter Klier: The Shakespeare case - The authorship debate and the 17th Earl of Oxford as the true Shakespeare. Laugwitz, Buchholz in der Nordheide 2004, ISBN 3-933077-15-X . (Revised and expanded version of The Shakespeare Plot . Göttingen 1994.)

- Robert Detobel: How William Shaxsper became William Shakespeare. Laugwitz, Buchholz in der Nordheide 2005, ISBN 3-933077-18-4 .

- Kurt Kreiler: The man who invented Shakespeare: Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-458-17452-3 .

- New Shake-speare Journal . Yearbook edited by Dr. Uwe Laugwitz and Robert Detobel (published since 1997).

Marlowians

(Chronologically)

- WG Zeigler: It was Marlowe: a story of the secret of three centuries. 1895. Novel-like fiction with a foreword that develops the theory.

- A. Webster: What, Marlowe the Man? In: The National Review . Volume 82, 1923, pp. 81-86. Theory based on the sonnets.

- C. Hoffman: The Murder of the Man who was Shakespeare. 1955. First monograph on the Marlowe theory.

- David Rhys Williams: Shakespeare, Thy Name is Marlowe. 1966.

- Lewis JM Grant: Christopher Marlowe, the ghost writer of all the plays, poems and Sonnets of Shakespeare, from 1593 to 1613. 1967.

- William Honey: The Shakespeare Epitaph Deciphered. 1969.

- William Honey: The Life, Loves and Achievements of Christopher Marlowe, aka Shakespeare. 1982.

- Louis Ule: Christopher Marlowe (1564-1609): A Biography. 1992.

- Annie D. Wraight: The Story that the Sonnets Tell. Hart, London 1994, ISBN 1-897763-05-0 .

- Annie D. Wraight: Shakespeare: New Evidence. 1996.

- Peter Zenner: The Shakespeare Invention. The life and deaths of Christopher Marlowe. Country Books, Bakewell 1999, ISBN 1-898941-31-9 .

- Alex Jack: Hamlet, by Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare. 2 volumes. 2005 ( related website )

- Samuel L. Blumenfeld: The Marlowe-Shakespeare connection. A new study of the authorship question. McFarland, Jefferson / NC 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3902-7 .

- Daryl Pinksen: Marlowe's Ghost: The Blacklisting of the Man Who Was Shakespeare . 2008, ISBN 978-0-595-47514-8 .

- Robert U. Ayres: The death and posthumous life of Christopher Marlowe ( website )

in German language:

- Bastian Conrad: The true Shakespeare: Christopher Marlowe, To solve the centuries-old authorship problem (5th edition, 2016) Book & Media, 2011, ISBN 978-3-86520-374-8 . ( related website )

Baconians

- N. Cockburn: The Bacon-Shakespeare Question . private publication, 1998 (Contents)

- Peter Dawkins: The Shakespeare Enigma. Polair Publ., London 2004, ISBN 0-9545389-4-3 (English)

- Amelie Deventer von Kunow: Francis Bacon: Last of the Tudors . 1924. Translated by Willard Parker.

- Penn Leary: Bacon Is Shakespeare , Cryptographic Shakespeare (n. D.)

- Virginia M. Fellows: The Shakespeare Code . 2006, ISBN 1-932890-02-5 .

- Erna Grautoff, Roman ruler over dream life , Berlin 1940.

- Baconian Evidence For Shakespeare Evidence

- Edwin Reed: Bacon vs. Shakspere, brief for plaintiff Service & Patton, Boston 1897

Rutlandians

- Karl Bleibtreu: The True Shakespeare. G. Mueller, Munich 1907.

- Lewis Frederick Bostelmann: Rutland. Rutland publishing company, New York 1911.

- Celestin Demblon: Lord Rutland est Shakespeare. Charles Carrington, Paris 1912.

- Pierre S. Porohovshikov (Porokhovshchikov): Shakespeare Unmasked. Savoy book publishers, New York 1940.

- Ilya Gililov: The Shakespeare Game: The Mystery of the Great Phoenix. Algora Pub., New York 2003, ISBN 0-87586-181-4 .

- Brian Dutton: Let Shakespeare Die: Long Live the Merry Madcap Lord Roger Manner, 5th Earl of Rutland the Real "Shakespeare". RoseDog Books, 2007. (Most recent study of Rutland theory)

Academic authorship debate

- Jonathan Hope: The Authorship of Shakespeare's Plays: A Socio-Linguistic Study. Cambridge University Press, 1994. (covers Shakespeare authorship problems outside of the authorship debate)

in German language:

- Hartmut Ilsemann: William Shakespeare - Dramas and Apocrypha: A Stylometric Investigation with R. Aachen: Shaker, 2014

Web links

Established view

- David Kathman and Terry Ross, The Shakespeare Authorship Page (table of contents)

- Irvin Leigh Matus's Shakespeare site with several articles from an orthodox point of view

- Truth vs. Theory, Shakespeare as an autodidact

- TL Hubeart, Jr. "The Shakespeare Authorship Question", brief overview of the authorship debate (web archive) ( Memento from January 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Alan H. Nelson's Shakespeare Authorship Pages, by an Oxford biographer who is not a proponent of the authorship thesis

"Anti-Stratfordians" (general)

- The Shakespeare Authorship Coalition , homepage of the "Declaration of Reasonable Doubt About the Identity of William Shakespeare" - concise presentation of the critics' viewpoints on Shakespeare's authorship. Doubters can sign an online declaration.

"Oxfordians"

- Latest research on Oxford theory

- Joseph Sobran to Kathman

- Shakespeare Oxford Society

- Film The Shakespeare Mystery

- Article by Joseph Sobran, The Shakespeare Library

- The Shakespeare Authorship Studies Conference, annual conference at Concordia University in Oregon

- The De Vere Society of Great Britain

- In Germany: New Shake-speare Society

"Baconians"

- N. Cockburn: The Bacon-Shakespeare Question. Self-published, 1998 (Contents) , OCLC 78892818

"Marlowians"

- Peter Farey's Marlowe Page

- Frontline: Much Ado About Something, website for a television documentary

- Marlowe Lives! Collection of articles, documents, links

- Jeffrey Gantz, Review of Hamlet, by William Shakespear and Christopher Marlowe: 400th Anniversary Edition by a Skeptic

- Peter Bull, Shakespeare's Sonnets Written by Kit Marlowe

More candidates

- Website on Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke: The Master of Shakespeare, AWL Saunders, 2007

- Robin Williams stands up for Mary Sidney in her book, website to that

- Advocates the Earl of Derby

- Terry Ross, "The Droeshout Engraving of Shakespeare: Why It's NOT Queen Elizabeth".

Individual evidence

- ^ Ch. Ogburn: The Mysterious William Shakespeare. 1984, p. 173.

- ^ National Portrait Gallery: Searching for Shakespeare , NPG Publications, 2006.

- ↑ Stephen Greenblatt: Letter To the Editor . In: The New York Times , September 4, 2005.

- ^ Edgar M. Glenn: Shakespeare and His Rivals, A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy. New York 1962, p. 63.

- ↑ See Gibson The Shakespeare Claimants: A Critical Survey of the Four Principle Theories Concerning the Authorship of the Shakespearean Plays , Routledge 2005, pp. 48, 72, 124.

- ↑ McMichael, p. 159.

- ↑ [1]

- ^ A detailed overview of the anti-Stratford debate and the Oxford candidacy is also provided by Charlton Ogburn's The Mystery of William Shakespeare , 1984, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Details of an evaluation of all documents from Shakespeare's life in Samuel Schoenbaum: William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life (OUP, 1987)

- ↑ George McMichael, Edgar M. Glenn: Shakespeare and his Rivals: A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy New York, The Odyssey Press, 1962, p. 41.

- ↑ Mark Anderson: Shakespeare. Gotham Books, New York 2005, pp. XXX

- ↑ See Anderson, loc. Cit.

- ↑ See Anderson loc. Cit.

- ↑ http://www.doubtaboutwill.org/

- ^ Justice John Paul Stevens: The Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction. In: University of Pennsylvania Law Review . Volume 140, No. 4 April 1992.

-

↑ David Kathman: Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Editor: Wells, Orlin. Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 624

David Kathman: The Spelling and Pronunciation of Shakespeare's Name . In: The Shakespeare Authorship Page . Accessed October 27, 2007. - ^ Robert Greene: Farewell to Folly. 1591.

- ↑ Roger Ascham: The Schoolmaster. ( Memento from July 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

-

↑ TW Baldwin: William Shaksperes Small Latine and Less Greeke. 2 volumes. University of Illinois Press, Urbana-Champaign 1944, passim .

See also Virgil Whitaker: Shakespeare's Use of Learning . Huntington Library Press, San Marino 1953, pp. 14-44. - ^ Germaine Greer: Past Masters: Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-19-287538-8 , pp. 1-2.

- ↑ http://www.shakespeareauthorship.com/school.html Critically Examining Oxfordian Claims: The Stratford Grammar School

- ↑ David Riggs: Ben Jonson: A Life. Harvard University Press, 1989, p. 58.

-

^ AL Rowse: Shakespeare's supposed "lost" years. In: Contemporary Review . February 1994.

David Kathman: Shakespeare and Richard Field . The Shakespeare Authorship Page - ↑ Jonathan Bate: Shakespeare and Ovid. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1994.

- ↑ Anderson loc. Cit.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ James Spedding: The Life and Letters of Francis Bacon. Volume 7. 1872, pp. 228-230 ("And in particular, I wish the Elogium I wrote in felicem memoriam Reginae Elizabethae may be published")

- ^ GE Bentley: The Profession of Dramatist in Shakespeare's Time: 1590-1642. Princeton UP, 1971.

- ^ First Folio, 1623, Epistle, A2

- ↑ Anderson: Shakespeare by Another Name. 2005, pp. 400-405.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of September 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Karl Elze: Essays on Shakespeare. 1874, pp. 1-29, 151-192.

- ↑ Braunmuller: Macbeth. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997, pp. 5-8.

- ↑ Frank Kermode: King Lear. The Riverside Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1974, pp. 1249-1250.

- ↑ Alfred Harbage Pelican / Viking editions of Shakespeare 1969/1977, Preface.

- ↑ Alfred Harbage: The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. 1969.

- ^ Miller: Shakespeare Identified , Vol. 2, pp. 211-214.

- ↑ Shakespeare himself used this phrase In: Heinrich VI. Part 1 (IV, iii, pp. 51–52), where he describes the dead King Heinrich V as “[t] has ever-living man of memory”

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd edition, 1989.

- ↑ Ruth Lloyd Miller, Essays, Heminges vs. Ostler, 1992.

- ↑ For more detailed facsimiles, see S. Schoenbaum: William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life , New York: OUP, 1975, pp. 212, 221, 225, 243-5.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from July 31, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ [3]

- ^ S. Schoenbaum: William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life New York: OUP, 1975, p. 234.

- ↑ Craig R. Thompson Schools in Tudor England , Washington, DC: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1958. David Cressy suspects that up to 90% were unable to sign by name; see Alice Friedman The Influence of Humanism on the Education of Girls and Boys in Tudor England. History of Education Quarterly Vol. 24, 1985, p. 57.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from May 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Were Shakespeare's Plays Written by an Aristocrat?

- ^ Jonathan Bate The Genius of Shakespeare London, Picador, 1997.

- ^ Ogburn The Mysterious William Shakespeare , 1984.

- ↑ Jonson: Discoveries 1641, ed. GB Harrison, New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966, p. 28.

- ↑ Jonson: Discoveries 1641 Ed. GB Harrison, New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966, p. 28.

- ↑ Jonson's Discoveries 1641, loc. cit. P. 29.

- ^ Peter Dawkins The Shakespeare Enigma , Polair: 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ McMichael, loc. cit., pp. 26-27.

- ^ Peter Dawkins The Shakespeare Enigma Polair, 2004, p. 47.

- ^ Arnold Davenport (ed.) The Scourge of Villanie 1599 , Satire III, in The Poems of John Marston Liverpool University Press: 1961, pp. 117, 300f.

- ^ Translation from Klaus Reichert, Salzburg and Vienna 2005, p. 165

- ↑ It was argued that at that time Bohemia actually extended as far as the Adriatic Sea - however, this is a strong coarsening that can only be maintained if one understands the Habsburg possessions as a whole by “Bohemia” . The Adriatic coast was also owned by the inner Austrian branch line. See JH Pafford, ed. The Winter's Tale , Arden Edition, 1962, p. 66.

- ↑ George Orwell As I Please December 1944 Archived copy ( Memento of August 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ See John Russell Brown, ed. The Merchant of Venice , Arden Edition, 1961, note on Act 3, Scene 4, p. 96.

- ↑ A Modern Herbal: Heartsease ; the Warwickshire dialect is also discussed in Jonathan Bate The Genius of Shakespeare Oxford UP, 1998 and in M. Wood In Search of Shakespeare , BBC Books, 2003, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Irvin Leigh Matus Shakespeare in Fact 1994.

- ^ Diana Price Shakespeare's Unorthodox Biography ISBN 0-313-31202-8 , pp. 224-25.

- ↑ George McMichael, Edward M. Glenn Shakespeare and His Rivals , p. 56.

- ^ John Michell "Who Wrote Shakespeare" ISBN 0-500-28113-0 .

- ^ Traubel: With Walt Whitman in Camden quoted in Walt Whitman on Shakespeare ( Memento of March 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ https://sourcetext.com/a-brief-biography-of-sir-george-greenwood/

- ↑ https://www.hna.de/kultur/wahre-shakespeare-dramatiker-christopher-marlowe-3384721.html

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from May 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Roger A. Stritmatter: The Marginalia of Edward de Vere's Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Reasoning Literary, and Historical Consequence. ( Memento of October 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) PhD diss., University of Massachusetts at Amherst, 2001. Reprinted in part in Mark Anderson, ed. The Shakespeare Fellowship (1997–2002) on its website

- ↑ Fowler, loc. Cit., 1986.

- ^ Ogburn: The Mystery of William Shakespeare. 1984, p. 703.

- ↑ Cf. Ingeborg Boltz: Authors' theories . In: Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 183–190, here p. 189. For the terminus a quo of The Tempest, which is clear from a textual and editorial science point of view, see for example William Shakespeare: The Tempest. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford Worlds Classics. Edited by Stephen Organ. 1987. ISBN 978-0-19-953590-3 , here Introduction p. 62ff. or Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. OUP 2001, ISBN 978-0-393-31667-4 . Second Edition 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 348. Likewise Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford 1987, reprinted Norton 1997, p. 132.

- ^ The Verse Forms of Shakespeare and Oxford

- ↑ Fowler, loc. Cit.

- ↑ Cf. Ingeborg Boltz: Authors' theories . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 183–190, here p. 189, as well as the presentation on the company's website [4] . Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ Cf. Ingeborg Boltz: Authors' theories . In: Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 183–190, here p. 189. See also the bibliographical information in the literature section.

- ^ Delia Bacon The philosophy of the plays of Shakespeare unfolded

- ↑ Sirbacon.org, Constance Pott

- ^ Bacon, Francis: Advancement of Learning 1640, Book 2, xiii

- ↑ for example the principles of good government, which Prince Hal explains in the second part of Henry IV

- ^ Francis Carr: Who Wrote Don Quixote? London: Xlibris Corporation, 2004.

- ^ British Library MS Harley 7017; reprinted in Edward Durning-Lawrence Bacon is Shakespeare 1910.

- ↑ Lambeth MS 976, folio 4.

- ↑ This is an allusion to the existing judgment on Bacon that he was as brilliant as a malicious intriguer as he was as a philosopher.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche : Complete Works . Critical study edition in 15 volumes. Edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari . Volume 6: The case of Wagner et al. a. New edition, DTV, Munich 1999, p. 287.

- ↑ Edwin Bormann: The Shakespeare Secret. Bormann, Leipzig 1894; Edwin Bormann: The historical proof of the Bacon-Shakespeare theory. Bormann, Leipzig 1897.

- ↑ Rulers over dream and life , Berlin 1940

- ↑ Historical bases and comments on the novel Rulers over Dream and Life , private typescript, Berlin 1940.

- ↑ William Shakespeare. Erna Grautoff. 42 sonnets. Edited and introduced by Jürgen Gutsch, EDITION SIGNAThUR, Dozwil / TG (Switzerland) 2016, ISBN 978-3-906273-10-5 .

- ↑ http://www.der-wahre-shakespeare.com/

- ↑ http://issuu.com/alliteraverlag/docs/9783865203748_leseprobe_issuu?e=2472932/5765391

- ^ Samuel L. Blumenfeld: Marlowe-Shakespeare Connection: A New Study of the Authorship Question. McFarland, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3902-7 .

- Jump up ↑ Daryl Pinksen: Marlowe's Ghost: The Blacklisting of the Man Who Was Shakespeare . 2008, ISBN 978-0-595-47514-8 .

- ↑ http://www.shak-stat.engsem.uni-hannover.de/

- ↑ The Case for Edmund Campion ( Memento of October 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Malcolm X, Alex Haley The Autobiography of Malcolm X Grove Press 1965.

- ↑ McMichael, p. 154.

- ↑ http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20070908/ap_on_re_eu/britain_shakespeare_debate ( Memento of September 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Ralf Lorenzen: "Shakespeare were different". For over ten years, Holger Lohse has been working as a kind of citizen scientist on the new translation of all 154 sonnets by William Shakespeare. In doing so, he made a discovery that could revolutionize Shakespeare research. In: The daily newspaper . August 13, 2018, accessed December 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Peter Intelmann: Who was Shakespeare - and if so, how many? William Shakespeare died 400 years ago. But did the Stratford man actually write the work attributed to him? Not only Mark Twain had his doubts. A translator from Lübeck assumes that the well-known author didn't even exist. In: Lübecker Nachrichten . January 7, 2016, accessed December 8, 2019 .