Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe (baptized February 26, 1564 in Canterbury , † May 30, 1593 in Deptford ), nicknamed "Kit", was an English poet, playwright and translator of the Elizabethan era .

Knowledge of Christopher Marlowe's personality and life is sparse and patchy. Most of them have been reconstructed "like a mosaic" from indirect, very different sources, records, testimonies and finds over the course of centuries.

The early New English language had no regular orthography, which is why the name Marlowe is spelled very differently. a. as Malyn, Marlar, Marley, Marlen, Marle, Marlin, Marly, Marlye, Marlyn, Marlo, Marlow, Merling, Merlin, Merley, Morley, Morleyn . In the case of various sources with differently written names, there is sometimes controversial debate about whether it was clearly Christopher Marlowe.

Life

Canterbury (1564-1579)

The earliest source about Christopher Marlowe is the baptism entry in St. George's Church in Canterbury on February 26, 1564. His exact date of birth has not been determined; it is believed to have been between February 15 and 26, 1564. He was born as the second child of the shoemaker and "free man" ("freeman") of Canterbury John Marlowe († February 1605) and his wife Catherine Arthur († July 1605) from Dover , whose wedding on May 22, 1561 is notarized. His great-grandfather Richard Marley and grandfather Christopher Marley were also shoemakers. The father had moved to Canterbury from Ospringe (now part of Faversham ) eight years earlier . Of the nine children, six survived childhood. The younger siblings are Margaret (* 1565), Joan (* 1569), Thomas I (* 1570, died early), Ann (* 1571, marriage 1593), Dorothy (* 1573, marriage 1594) and Thomas II (* 1576). A Canterbury source (1573) identifying a 12-year-old boy Christopher Mowle as Marlowe has not been widely recognized.

On January 14, 1579, he officially began a fellowship at King's School in Canterbury. At that time there is evidence that he was well versed in Latin. Nothing is known about his schooling up to this date. As a schoolmate at the King's School, the brother of the playwright John Lyly , Will Lyly, (Lilly or Lylie) was recognized. The satirist Stephen Gosson and the physiologist William Harvey began their training at this school before and after Marlowe, respectively. The Archbishop of Canterbury from 1559 to 1575, Matthew Parker , who was a close reference person to Queen Elizabeth I through his previous chaplaincy to Elizabeth's mother Anna Boleyn , had in his will a university scholarship for a student at the King's School in Canterbury at Corpus Christi College of Cambridge University left what some years after his death († 1575) chose his son Jonathan (John) Parker Christopher Marlowe. John Parker was a friend of Sir Roger Manwood , Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer. A Latin elegy in his honor was discovered on the occasion of his death in 1593, the author of which is believed to be Marlowe. The Latin epitaph was found on the back of the title page of a copy (1629) by Marlowes and George Chapmans Hero and Leander .

There is evidence that after leaving Cambridge (1580), Marlowe returned to Canterbury at least twice, once in the autumn of 1585 on the occasion of a will certification (see signature) of a Mrs. Benchkyn and in 1592 when he got into a dispute with the singer and composer William Corkine II was involved, who published the songbook Second Book of Airs in 1612 .

Cambridge (1580-1586)

Marlowe left Canterbury at the age of almost 17 in late 1580 to begin his fellowship at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge . According to the university register, he was registered as “convictus secundus” “Coll.corp.xr.Chrof.Marlen” on March 17, 1581. The name “Christof. Marlyn ”appears in the list of students at Corpus Christi College who were admitted to the BA, while the name“ Marley ”appears as the 199th of 231 students on the“ Ordo Senioritatis ”in the“ Grace Book ”of Cambridge University in 1583 / 84 is listed. In Cambridge, where he was officially enrolled for the next seven years, he obtained his BA in 1584 and his MA in 1587. Unknown is the exact period during which he became a friend of Thomas Walsingham, his younger cousin, Sir Francis Walsingham , who was the was the influential "head of the secret service" of Queen Elisabeth. Francis Walsingham owed his own position at court and his seat on the Privy Council (from 1573) to his powerful patron and confidante William Cecil, Lord Burghley , Royal Chancellor of the Exchequer and chief advisor to the Queen and also Chancellor of Cambridge University. Both Francis and Thomas Walsingham and Lord Burghley, as far as the sources indicate, must have played a prominent role in Marlowe's life and work in Cambridge and London.

Literary historians have not yet been able to clarify when Marlowe's friendship with Thomas Walsingham began. In Edward Blount's attribution of the epic poem Hero & Leander to Thomas Walsingham, he marks the close relationship between Walsingham and the poet Marlowe "the man that hath been dear unto us". It is documented that Thomas Walsingham was with his older cousin Francis Walsingham and Philip Sidney in the St. Bartholomew lingered on 24 August 1572 the British Embassy in Paris, during the massacre of the Huguenots, about Marlowe his drama the Massacre at Paris wrote. Francis Walsingham's only daughter by second marriage Frances married Sir Philip Sidney, Earl of Essex in 1583, second marriage to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex , third marriage to Richard Burke, 4th Earl of Clanricarde . Thomas Walsingham, who was in the service of his influential cousin Francis Walsingham at a young age, is regarded as a friend and patron and, with a high degree of probability, also as Marlowe's lover.

The sources of the scholarship accounts received and records of expenses from the college canteen ("College Buttery") provide some information about his actual presence in Cambridge. From these sources it is clear that he was absent more frequently for longer periods, for example seven weeks in June – September 1582, seven weeks in April – June 1583. For the academic year 1584/85 (his first year as Dominus Marlowe, BA) appears he was present for far less than half of the prescribed time. Although payment documents for the academic year 1585/86 are missing, his "Buttery Accounts" show that he was officially only absent between April and June 1586. Little is known about his stays during his absence except for a stay in his hometown of Canterbury, during which he signed the will of the otherwise unknown person Catherie Benchkyn in August 1585. Marlowe's signature, which has survived and which he signed with "Christofer Marley" comes from this will, together with his father's signature.

It is believed that Francis Kett , who received his BA in 1569 and MA in 1573 at the same Corpus Christi College and was burned at the stake in Norwich on January 14, 1589 for heresy , was a fellow and tutor at his college and had him in his influenced religious attitudes.

In Cambridge, around 1582/83, he translated Ovid's erotic love poems Amore and Lucan's Pharsalia, First Book (poem about the battle of Pharsalus ) from Latin. Marlowe's Ovid translation, which went to press in 1596, succumbed to censorship and was exiled by cremation in 1599 on the orders of Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift and Bishop of London Richard Bancroft . The True History of George Scanderbeg is believed by some experts to be the first complete play from the same period to be lost . The majority of literary historians assume that he might have conceived Queen of Carthage Dido with the help of Thomas Nashe and Tamburlaine , Part I, in Cambridge within around 1584/86, with which he later had great success in London.

London (1587–1593)

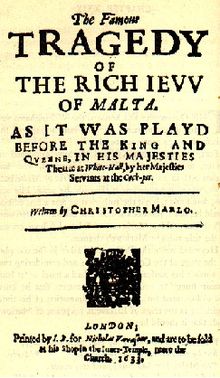

As far as the sources and reconstructions indicate, he must have begun to write for the theater directly in the last six years of his life in London from 1588 to 1593. This was followed by performances of his plays Dido , Edward II , The Massacre at Paris , Doktor Faustus , The Jew of Malta , performed by the members of the theater groups Lord Admiral's Company of Players ( Admiral's Men for short ) under the leadership of the theater manager and actor Edward Alleyn or Lord Strange's Men or The Earl of Pembroke's Men . During Marlowe's lifetime, none of his printed works bore his name. Editions of Tamburlaine 1590 and 1592 did not have a name on the title page. All other works associated with the name Marlowe were not printed until after his death in 1593.

1587

Even before his MA was approved (March 13, 1587), it can be deduced from a source that he was intended for a stay at the Catholic seminary in Reims (“was determined”). At the same time as Marlowe's absence, the Babington conspiracy occurred, which was conceived at the Catholic seminary in Reims , which was under the direction of William Allen . At that time, Allen organized the Catholic resistance against the Protestant rule of Elizabeth I in England. "Non-Catholic" students were also admitted there, and the rumor that had reached Cambridge that Marlowe might be staying in Reims as a converted Catholic prompted the administration of Corpus Christi College in Cambridge to withhold permission to grant his Master's degree (MA).

William Allen, appointed cardinal in 1587, established the English Catholic Seminary in 1569 at the university founded by King Philip of Spain in Douai (northern France) in 1559, which had to leave Douai in 1578 and continued in Reims until 1593. At that time, like Christopher Marlowe, to be suspected in the Catholic seminary at the "Collège des Anglais" in Reims, was considered an affront to Protestant England. From 1580 to 1587 Reims was the center of the “Catholic rebellion against England and Queen Elizabeth”. Marlowe appealed to the Privy Council to declare it unencumbered, which the Privy Council did in a conspicuous way with the surviving letter of June 29, 1587 to the University of Cambridge, signed and signed. a. by the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Whitgift ; and by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Cecil, Lord Burghley.

“Whereas it was reported that Christopher Morley was determined to have gone beyond the seas to Reames and there to remaine, Their Lordships thought good to certefie that he had no such intent, but that in all his accions he had behaved him selfe orderlie and discreetlie wherebie he had done her Majestie good service, & deserved to be rewarded for his fathfull dealinge: Their Lordships request that the rumor thereof should be allaied by all possible meanes, and that he should be furthered in the degree he was to take this next Commencement : Because it was not her Majesties pleasure that anie one emploied as he had been in matters touching the benefitt of his Countrie should be defamed by those that are ignorant in th'affaires he went about. To this are appended the titles of the Lord Archbishop (John Whitgift), Lord Chancelor (Christopher Hatton), Lord Thr [easur] er (William Cecil), Lord Chamberlaine (Henry Carey) and Mr. Comptroler (James Crofts). "

This source makes it clear that Marlowe was in the "highest" official service of the Privy Council (probably at least since 1584) and at the same time there must have been a strong interest from Privy Council and Queen Elisabeth that Christopher Marlowe received the Master Degree (MA) from the leadership the university is not denied. Queen Elisabeth certifies to Marlowe that he was engaged in matters for the good of the country and that he deserved to be treated with trust for it (“deserved to be rewarded for his fathfull dealinge”). From this it was concluded that at the age of 20 Marlowe must have been held in high esteem by the very highest authorities in the crown and government, especially William Cecil and Sir Francis Walsingham and the court of Queen Elizabeth. It is not known to this day whether Marlowe's government service consisted of conveying reports between foreign embassies and royal courts or whether he was one of Francis Walsingham's regular informants and (travel) companions and diplomats. It is considered likely that he was active as an ambassador and scout. There is no clear evidence in any known source that he carried out "regular" espionage work for Francis Walsingham. He must have been entrusted by the Privy Council with much more highly regarded tasks. In July 1587 he promptly received his MA, probably never returned to Cambridge and spent the presumed last six years of his life in London. In an official letter from Robert Ardern to Lord Burghley, dated October 2, 1587, sent from Utrecht (“the Low Countries”), a “Morley” is listed among the “government messengers”, of which many experts are convinced that it could only have been Christopher Marlowe.

1588/1589

The growing success of Marlowe's theater productions in London drew the attention of other poets such as Robert Greene , who appears to show his "rivalry" with Marlowe in several of his writings. It is believed that Greene alludes to Marlowe in his foreword to Perimedes the Blacksmith (1588).

The Menaphon with a foreword by Thomas Nashe , published on August 23, 1589, presumably contains, in various passages, Greene's attack on Marlowe. May have been The Jew of Malta already listed in 1589 in London. While the beginning of his stay in London in 1587 is largely in the dark, he is more recognizable by a source dating back to 1589, which states that he was in Norton Folgate, Shoreditch , outside and north of the city limits of London near the poet Thomas Watson lived where the two main London theaters, The Theater and The Curtain, were.

Despite the generally small and in part unreliable and mostly only indirect sources, Marlowe seems to have had a larger circle of friends and acquaintances in London, including in particular his friend and patron Thomas Walsingham, younger cousin of Queen Elizabeth I's influential chief of intelligence, Francis Walsingham. In London he belonged to a group of intellectuals, educated nobility, philosophers and poets around Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland , (also born in 1564) and Sir Walter Raleigh , who had formed a secret group of free thinkers The School of Night , the Discussed “forbidden knowledge” behind closed doors and was stigmatized as a “circle of atheists”. This circle also included the mathematician Thomas Harriot , Walter Warner and the poets Matthew Royden and Philip Sidney . It can be assumed with good reason that he knew the publishers Edward Blount, editor of Shakespeare's First Folio , and Thomas Thorpe, editor of Shakespeare's sonnets, as well as the University of Wits , a, later so-called, circle of poets and poets. Playwrights with Thomas Nashe, Robert Greene, George Peele , John Lyly and Thomas Lodge who got together in London and wrote for the theater and the public. Moving in theater circles, he must have known the theater manager Philip Henslowe , who sold his plays, and the gigantic Edward Alleyn, who starred in most of his plays. He is also credited with an acquaintance with Lord Strange (the future Earl of Derby), whose cast, the Lord Strange's Men , had performed his plays.

From a source of a letter from the Countess of Shrewsbury, Elizabeth Talbot to William Cecil dated September 21, 1592 it becomes clear that Christopher Marlowe was tutor or tutor (reader and attendant) with her granddaughter Lady Arabella Stuart for three and a half years between 1589 and 1592 , before he left her.

“One Morley, who hath attended on Arbell and read to her for the space of three year and a half, showed to be much discontented since my return into the country, in saying he had lived in hope to have some annuity granted him by Arbell out of her land during his life, or some lease of grounds to the value of fourty pound a year, alleging that he was so much damnified by leaving the University…. I understanding by divers that Morley was so much discontended, and withall of late having some cause to be doubtful of his forwardness in religion (though I cannot charge him with papistry) took occasion to part with him. After he was gone from my house, and all his stuff carried from hence, the next day he returned again, very importunate to serve, without standing upon any recompense…. From my house at Hardwyck, the 21st Sept. 1592. "

This source was neglected for a long time until it was discovered that Lady Shrewsbury, Elisabeth Talbot, on 18/28. September 1589 the "headquarters of her business empire" moved from Hardwick, Derbyshire to London, and Arabella Stuart is likely to have been in London at the same time as Marlowe. Since Arabella Stuart was one of Queen Elizabeth's immediate aspirants to the throne (niece of Maria Stuart and cousin of James VI. Of Scotland ) and thus posed a threat to the Queen, it was also assumed that the appointment of Marlowe as tutor Arabella Stuart by the Privy Council could have served as a source of information for the government (Francis Walsingham or William Cecil).

Records of an incident at the same time on September 18, 1589 show that he was involved in a dispute in "Hog Lane" ( St Giles-without-Cripplegate parish ), in which his poet friend Thomas Watson, in self-defense, William Bradley, the son of an innkeeper, killed. He was taken to Newgate Prison with Watson, bailed on October 1st, and officially acquitted on December 3rd. Thomas Watson was, like Marlowe, friends with Thomas Walsingham, to whom he dedicated Meliboeus in 1590 , a Latin elegy on the death of the powerful and influential cousin Francis Walsingham.

1590/1591

On August 14, 1590, his play Tamburlaine was submitted to the guild of printers, publishers and booksellers, the Stationer's Register .

Sources indirectly indicate that he shared an apartment with Thomas Kyd in London in 1591 . In January 1592 Marlowe (Christofer Marly) on the continent in Vlissingen , an English garrison town at the time, was accused by Richard Baines (who a year later accused him of heresy and atheism) of having coined false shillings and had treasonous intentions, and was arrested . Sir Robert Sidney sent him back to England with a letter dated January 26, 1591/2, to the Lord Chamberlain William Cecil, who was to decide his case. From the letter, which details the situation of the mutual allegations of Richard Baines and Marlowe, it can be seen that Governor Robert Sidney does not appear to be convinced that serious counterfeiting was intended, and that Marlowe is well known with Lord Northumberland and the Lord Stranges Men theater company . Richard Baines informed Governor Robert Sidney of the incident the day after the crime. A year later, a few days before Marlowe's death, Baines again accused Marlowe of the most serious offense and came back to this incident of counterfeiting.

"... that he [Marlowe] had as good Right to Coine as the Queen of England and that he was acquainted with one Pooly (Poley) a prisoner in Newgate who hath greate skill in mixture of metals and having learned some thinges of him he ment through help of a Cunninge stamp maker to Coin French Crownes pistoletes and English shillinges. "

It is not known if Marlowe was held accountable in any way as part of this incident. Other sources indicate that he was free at least three months later. One explanation for his speedy release was given that his influential connections and assignments to the Privy Council, especially Lord Burghley, must have existed earlier.

1592/1593

On March 12, 1592, during the siege of Rouen by the English, the English ambassador Sir Henry Unton received a “Mr. Marlin ”together with a delegation from the Queen lying in the port of Dieppe , with a complaint from the English garrison about lack of food, demand for supplies or permission to return. From Dieppe Marlowe ("Mr Marlin") was returned to Lord Burghley with a letter, whose letter was marked:

"To the Lord Treasurer; by Mr. Marlin… this bearrer also they send, by whom I thought good to write to your Lordship to crave your furder directions in that behalfe, beinge sorry to see ther wants. "

It is relatively safe assumption that both the drama The Jew of Malta and the tragedy of Edward II in winter 1591/1592 of Pembroke's Men in London Rose Theater have had their needs, although Edward II is not in the diaries (Diaries) of Theater manager Philip Henslowe is noted and therefore no exact data are available about the first performances. For Edward II, however, it can be concluded relatively reliably from indirect references (lines of text), in particular through its powerful effect on his contemporary poet rivals (Kyd, Peele , Lodge , Nashe, anonymous author of Arden Feversham ) about the period of the first performances.

It is now widely accepted that Marlowe is the author of the Latin dedication, signed with C. M, by Thomas Watson Amintae Gaudia to Mary Sidney Herbert , Countess of Pembroke, (1592). On June 23, 1592, the Privy Council, disturbed by riots in Southwark , closed all theaters in London. The closure was prolonged by a severe plague outbreak and lasted until June 1594 before the theaters reopened. From September 15, 1592, there is a source of legal action in Canterbury, in which it came about the cost of a damaged jacket in a dispute between Marlowe and an old friend William Corkine in Canterbury. Apparently the case was amicably resolved outside the court. Years later (1612) his son William Corkine II published an instrumental arrangement of Marlowe's poem Come Live with Me ("a sweet new tune") in his second songbook, Second Book of Ayres .

Robert Greene 's posthumous work , "Greene's Groatsworth of Wit, bought with a million of Repentance," published on September 20, 1592, allegedly written on Greene's deathbed (he died on September 3, 1592), contains a letter to three Playwright colleagues with various admonishing warnings.

"I will send warning to my olde consorts, which have lived as loosely as my selfe, albeit weakenesse will scarce suffer me to write, yet to my fellowe Schollers about this Cittie, will I direct these few insuing lines. ... To those Gentlemen his Quondam acquaintance, that spend their wits in making Plaies, R. G., wisheth a better exercise, and wisedome, to prevent his extremities. "

Experts agree that the three unnamed playwrights must have meant Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, and most likely George Peele. In the part of the text that refers to Marlowe, Greene worries about the urbane atheist Marlowe without actually attacking him. Marlowe is accused of atheism in a longer consideration:

"I doubt not but you will look back with sorrow on your time past, and indevour with repentance to spend that which is to come. Wonder not (for with thee wil I first begin), thou famous gracer of Tragedian, that Greene, who hath said with thee (like the foole in his heart) There is no God, should now give glorie unto his greatnes: for penetrating is his power, his hand lies heavie upon me, he hath spoken unto me with a voice of thunder, and I have felt he is a God that can punish enimies. Why should thy excellent wit, his gift, bee so blinded, that thou shouldst give no glory to the giver? Is it pestilent Machivilian pollicy that thou hast studied? O peevish follie! What are his rules but meere confused mockeries, able to extirpate in small time the generation of mankind ?. for if Sic volo, sic iubeo, hold in those that are able to commaund: and if it be lawfull Fas & nefas to do any thing that is beneficiall, onely Tyrants should possesse the earth, and they striving to exceed in tyrannie, should each to other bee a slaughter man; till the mightiest outliving all, one stroke were left for death, that in one age man's life should end. The brother of this Diabolicall Atheisme is dead, ... "

With the following passage, the doomed Robert Greene again turns to Marlowe, Nashe and Peele (?) With a warning against atheism, blasphemy and lust.

"But now returne I againe to you three, knowing my miserie is to you no news: and let me hartily intreate you to bee warned by my harms. Delight not (as I have done) in irreligious oathes; for from the blasphermers house, a curse shall not depart. Despise drunkennes, which wasteth the wit, and maketh men all equall unto beasts. Flie lust, as the deathsman of the soule, and defile not the Temple of the holy Ghost. Abhorre those Epicures, whose loose life hath made religion lothsome to your eares: and when they sooth you wit htearmes of Mastership, remember Robert Greene. "

These evaluations of Greene already reveal the looming dangers to which Marlowe was exposed in the immediate aftermath in repressive, puritanical England.

In January 1593, The Paris Massacre was "re-performed", as the theater manager Philip Henslowe entered in his diary ( ne for new), and repeated ten times in the summer of 1594 when the theaters reopened after the plague.

Circumstances in the last months of life

Culminating life-threatening situation

From the winter / spring of 1592/1593 a series of events occurred which undoubtedly must have put Marlowe in an extremely threatening position. In 1593, Thomas Nashe was arrested and incarcerated, and Thomas Kyd , two friends of Marlowe, was tortured , and religious dissidents such as John Penry (* 1559 - May 29, 1593) were hanged on the eve of Marlowe's death, Henry Barrowe and John Greenwood along with three printers who had published their works. On May 5, 1593, "xenophobic" posters, threatening immigrant Protestant merchants from Holland and France, were pasted in blank verse , in the Marlowe style, on the wall of the Dutch Churchyard on Broad Street , now known as " Dutch Church Libel ”. One of the surviving threatening posters begins:

- You strangers that inhabit in this land,

- Note this same writing, do it understand,

- Conceive it well, for safe-guard of your lives,

- Your goods, your children and your dearest wives

in German:

- You strangers who live in this land

- Pay attention to this writing, understand it,

- She knows well how to preserve your life,

- Your goods, your children and your dearest wives

This 1593 poster, discovered in 1973, was signed by an anonymous person named “Tamburlaine”, one of Marlowe's famous main characters from the play of the same name and with references to two other of his plays (The Paris Massacre, The Rich Jew of Malta) . The result was that, on the basis of his plays, he was held at least indirectly responsible for the public unrest that can be shown to arise from the texts from April 16. The posters brought to Queen Elizabeth's attention challenged her authority. The Queen's Privy Council et al. a. with Sir Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury , Lord Archbishop , Earl of Derby , - ordered on May 11th 1593 to find those responsible for the "Libel" and to find out the truth under torture and to punish them.

"If you shal find them dulie to be suspected and they shal refuze to confesse the truth, you shal by aucthoritie hereof put them to the torture in Bridewel, and by th'extremitie thereof, to be used at such times and as often as you shal thinck fit, draw them to discover their knowledge concerning the said libels "

The search for those responsible undoubtedly included Marlowe as the author of Tamburlaine, despite the lack of evidence of involvement in the authorship of the posters. The following day, May 12, 1593, the poet and playwright Thomas Kyd was arrested, who was suspected as the main troublemaker, to be responsible for drawing for the Dutch Church Libel . His room was searched and allegedly heretical writings were found in which the deity of Jesus is denied and which he portrayed as belonging to Marlowe and originating from their time together in 1591, when he was still living with Marlowe in the same room and both wrote together . Although Kyd was arguably innocent of the Dutch Church Libel's primary accusation , he was tortured in Brideswell prison . He accused Marlowe - trying to distance himself from him as much as possible - of atheism. He later repeated his allegations against Marlowe in writing. Kyd's written notes are likely to mark the things he said when questioned in May 1593, but they must have been written after May 30, 1593, as reference is made to a dead Marlowe.

In a letter from Kyd to Lord Keeper Sir John Puckering , Kyd expanded his allegations against Marlowe under the obvious threat of being suspected and accused of atheism. On May 18, 1593, Marlowe received a summons from Henry Maunders, who had been sent to his whereabouts, to appear before the Privy Council in Nonsuch , Surrey, on charges of blasphemy, atheism and free-thinking.

"To repaire to the house of Mr Tho: Walsingham in Kent, or any other place where he shall understand where Christopher Marlow may be remayning, and by vertue hereof to apprehend, and bring him to the Court in his Companie."

Marlowe followed this edition on May 20, 1593. He stayed at the time of the plague in London with his patron and friend Thomas Walsingham (1561-1630) at the Walsinghams' country estate in Scadbury, Chislehurst Kent , after the death of his brother Edmund Walsinghams came into his possession in 1590. In contrast to the arrested and tortured Thomas Kyd, Marlowe was released on bail with the requirement to report daily until further notice. There are no sources as to whether Marlowe complied with this requirement.

At the same time, other massively incriminating documents emerged in quick succession, all of which were supposed to confirm that Marlowe was not only an atheist himself, but had also encouraged and strengthened others in their atheism. They were:

- the so-called Remembrances documents with attacks or accusations against Richard Cholmeley directed to William Cecil in the second half of May 1593, most likely originating from a Thomas Drury, which at the same time contained accusations of Marlowe's campaigning for atheism.

- further charges again, most likely by Thomas Drury, allegations against Richard Cholmeley, first sent to Justice Young, which (according to Drury) were passed on to Sir John Puckering and Lord Buckhurst and from there to Queen Elizabeth. These charges related to the previous allegations.

- the Baines Notes with a whole list of the most massive allegations and denunciations by the informant Richard Baines against Marlowe's blasphemy, which were probably handed over to the Privy Council around May 27, 1593. Both the original and a copy of these notes exist, which were probably sent to the Privy Council and the Queen. Although the Baines notes or information were delivered three days before Marlowe's death, the document was held back for a few days for corrections and only reached the Privy Council and the Queen as a slightly modified copy after the death (with a modified date). It has been argued that the leaving of Marlowe at large and the delay in the "Baines Report" may have created a need to delay the planning and execution of Marlowe's fake death rescue. It has been suggested that the official record of the massive denunciation of Marlowe by Richard Baines had been withheld for a while to be edited before reaching the Privy Council and the Queen.

These circumstances of the written fixation of the Baines denunciations were interpreted to mean that there must have been influential persons at court, in the highest power center, who could delay and change such reports in order to protect Marlowe. In this case it could only have been Queen Elizabeth's "right hand man" William Cecil, together with his son Sir Robert Cecil.

The summary of various sources suggests that Christopher Marlowe had been in close contact with Lord Burghley for at least eight years. Marlowe's scholarship came from Jonathan Parker, son of Archbishop Matthew Parker , who in turn was a close friend of Burghleys. It was Burghley who persuaded Matthew Parker to take the place of Archbishop of Canterbury (1559-1575). There is evidence that Matthew Parker gave one of the few copies of his De Antiquitate Ecclesiae Burghley during a period of depression after his wife's death . Robert Cecil had started his studies at the same time as Marlowe at the age of 17 at the same college in Cambridge, and it is inconceivable that he and Robert Cecil did not meet - like Thomas Nashe - probably through "Jonathan Parker" , the mediator of the Marlowe scholarship and friend of the Cecils family.

The fact that such tremendous material and such massive accusations against Marlowe were "brought up" in such a short time was assessed to the effect that a "concerted campaign" against Marlowe must have been staged here. The question of who was behind this campaign has been discussed at length. The strongest suspicion falls on Richard Baines (a priestly man who is equated with a "rector" of Waltham, near Cleethorpes in Lincolnshire - until at least 1607 -), a "Cambridge man" whose backers were in the leadership of the church of England and thus the Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift , for whom Richard Baines worked since at least 1587.

According to various experts, it is no coincidence that Christopher Marlowe, who is threatened with torture and the death penalty, died at exactly the same time because of a comparatively trivial matter (dispute over the payment of a bill).

death

According to Meyerschen Konversationslexikon (1888), Marlowe died "stabbed to death by his rival in a love affair". As late as 1917, the official version of the death of Marlowe in the English Dictionary of National Biography (DNB), the statement that has been widely spread over the centuries to this day, that Marlowe died while drunk in a tavern or in a fight (Sir Sidney Lee "... was killed in a drunken fight ..."). It was not until the late, astonishing discovery of the “Coroners Report” by Leslie Hotson in 1925 that the view of the death of Marlowe (“tavern brawl”), which has been fixed and continued to this day, was only very gradually shaken. If one follows this Latin report by the royal coroner or coroner William Danby, Coroner of the Queen's Household, Marlowe met on the morning of May 30, 1593 in the house of a "certain" widow Eleanor Bull (about the tenth hour before noon of the same day met together in a room in the house of a certain Eleanor Bull, widow) in Deptford, half a mile west of Queen Elizabeth's Greenwich Palace , with three people - Nicholas Skeres, Ingram Frizer and Robert Poley (also Robin Poley, Roberte Pooley, Robte Poolie, Poolye, etc.).

Eleanor Bull must have been a respected lady, widow of Richard Bull with Court ties. Her sister Blanche was the goddaughter of Blanche Perry, Queen Elisabeth's wet nurse and cousin of Lord Burghley. Eleanor Bull's brother-in-law John Bull was also in the service of the "founder of the British secret service" Sir Francis Walsingham. Poley's function as the accredited courier and bearer of important letters, messages and messages from Lord Burghleys between various royal courts and English embassies in the period between 1588 and 1601 is well documented. The lists of Poley's wages before Marlowe's death between December 17, 1592 and March 23, 1593 show him longer at the Court of Scotland.

“… Carrying lettres in poste for her heighness speciall service of great importance from Hampton Courte into Scotlande to the Courte there…”

Assuming that Thomas Kyd's allegations against Marlowe at the time, that he was in correspondence with the King of Scotland and persuaded people to go with him, it was concluded that Robert Poley was an ambassador to Scotland under Marlowe's supervision .

"... he [Marlowe] would pswade with men of quallitie to go unto the king of Scotts, whether I heare Royden is gon, and where if had livd, he told me, when I saw him last, he meant to be ..."

From a letter from Lord Burghley to his son Sir Robert Cecil on May 21, 1593 it appears that the Cecils were planning to send Marlowe to Scotland in the matter of the Spanish Blanks. Poley, like Thomas Walsingham and Nicholas Skeres, was involved in the uncovering of the " Babington Conspiracy " in which Queen Elizabeth I was to be killed and Mary Queen of Scots enthroned. All three men present at the time of Marlowe's death had professional connections to the power center or were in the service of Thomas Walsingham or Lord Burghley and were, like Marlowe, acquainted with Walsingham. According to the Coroners Report, they ate lunch together, spent a quiet afternoon at Eleanor Bull's house, and went out into the garden. After dinner, the other three sat with their backs to Marlowe, who was lying on a bed next to them. A dispute broke out between Marlowe and Frizer over the payment of the bill or its calculation. Marlowe pulled Frizer's dagger from behind and hit him, injuring his head. A fight ensued in which Frizer thrust the dagger into Marlowe's head above the right eye and immediately killed him.

Two days later, Queen William Danby's coroner and 16 jurors confirmed that Ingram Frizer had acted in self-defense. He was released within a month. Marlowe was buried on June 1, 1593 in the churchyard of St. Nicholas Deptford. (Register St. Nicholas Church Deptford, Christopher Marlow slaine by ffrauncis ffrezer, noticeably not Ingram.)

Inconsistencies in the circumstances of death

In the documented "Deptford Death Scenario", various inconsistencies have been recognized and analyzed by experts, which related to the meeting of the men in a house near Lord Burghley (especially in view of the acute life-threatening situation that existed for Marlowe during the same short period ) have assigned a specific purpose. They argue that ...

- … A documented meeting of three men for a day in a house and garden in the immediate vicinity of Lord Burghley at a time of acute life threat to Marlowe must have had a certain meaning and function.

- ... the evidence determined and documented during the funeral inspection or determination of the circumstances of death depended solely on three people present (Robert Poley, Ingram Frizer, Nicholas Skeres) from the immediate vicinity of Thomas Walsingham, the friend and patron saint Marlowe and Lord Burghleys. It is assumed that the 16 jurors did not know the person or the face of Marlowe and therefore could not identify him.

- ... the body of Marlowe, at the same time as the official registration of his death, was hastily buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas' Church in Deptford.

- ... William Danby in his role as "Coroner of the Queen" must have been in close professional relationship with Cecil for at least four years. Both may have known each other well, as they both worked in the Gray's Inn / Lincoln's Inn bar in London from May 1541 , along with Thomas Walsingham Sr., father of Marlowe's friend of the same name.

- ... Marlowe's death was not reported until the next day.

- ... it was basically up to the county's coroner to investigate a death within the Queen's 12-mile zone (“within the verge”) together with a royal coroner, here Sir William Danby, and that the county's coroner had to write the investigation report. William Danby, who was under the direct control of the Privy Council or the Queen and who called the Coroner's Court of 16 jurors at Deptford, should not have done this on his own.

- ... the place where the murder took place was the estate of Eleanor Bull, whose close connections to the court are seen through William Cecil and the Cecils according to today's view.

- ... the murderer Ingram Frizer was sent to prison to await the Queen's pardon, which came in an exceptionally short period of 28 days, the shortest in the annals.

After his release on June 28, 1593, Frizer immediately returned as a free man to the service of his master Thomas Walsingham, whose best friend and admired poet Christopher Marlowe he had "just killed".

Posthumous events and documents

According to a source, two weeks after Marlowe's death, one of the men present at Marlowe's death, Robert Poley, received £ 30 from the Treasury "for the carriage of the Queen's mail in special and secret affairs of great importance". This fact was interpreted to mean that Poley must have been in the service of the Privy Council or Her Majesty in the phase of the Dutch Libel and the murder of Marlowe in May / June 1593. The fact that Marlowe's death came just days after his arrest and heresy charge, with impending death and torture, contributed to his being discussed as a candidate in the Shakespeare's authorship debate ( Marlowe theory ).

On July 6, 1593, Edward II , and on September 28, Marlowe's translation of Lucan's First Book and Hero and Leander by John Wolf, was registered with the Stationer's Register for printing. 1594 followed the application for printing of The Jew of Malta (May 17, 1594) and the publication of Edward II and Dido, Queen of Carthage, completed by Thomas Nashe. In 1596, Marlowe's translation of Ovid's elegies was printed without a date or license, and three years later it was censored and publicly burned.

Literary work

Work overview

- Plays

- Dido, Queen of Carthage

- Tamburlaine the Great (Part 1)

- Tamburlaine the Great (part 2)

- The Jew of Malta

- The Massacre at Paris

- Edward II

- The Tragicall History of Dr Faustus

- Poetry

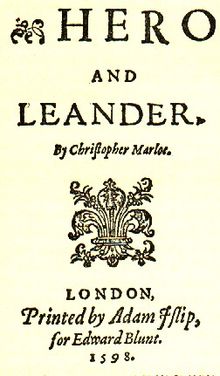

- Hero and Leander

- The Passionate Shepherd to his Love

- Translations

- Ovid, Amores

- Lucan's Pharsalia, first book

- Two assignments

(Attributed to Marlowe, original in Latin)

- Dedicated to Mary Countess of Pembroke

- Epitaph on the death of Sir Roger Manwood

subjects

Marlowe thematized numerous social, political and religious subjects and thus problematized the beliefs accepted at the time. Alongside Shakespeare, he is considered the most important literary representative of the English Renaissance . One of their main characteristics is the newly won belief in the possibilities of human reason and willpower. Marlowe turned his attention to the deeds of great men and chose historical figures as heroes from warlike tradition, from circles of finance or diplomacy, who are carried by their own powerful vitality.

Marlowe provides each individual hero with the appropriate direction of striving for power. Tamburlaine represents the irresistible pursuit of martial power, Dr. Faustus striving for power over the realm of the spirit and the forces of nature, the Jew from Malta striving for the power of gold and power over markets and people. Marlowe's heroes renounce the traditional rules of Christian ethics, which inhibit the freedom of action for the realization of their goals. The striving for power without alignment to ethical goals, however, discharges into catastrophes and leaves havoc. This motif is most clearly designed in The tragic history of Doctor Faustus , an adaptation of the Faust material .

The fight against the will of the gods is treated in the epic poem Hero and Leander , a free translation of Musaios . In Marlowe's arrangement it comprises two chants. Marlowe gave George Chapman the rights to the poem, which expanded the tragic story of the two lovers Hero and Leander to a total of six chants.

reception

There are numerous contemporary sources that speak of Marlowe's literary talent. George Peele (1556–1596), a contemporary playwright, used a traditional formula to describe him shortly after the news of his death in 1593 as the “darling of the muses”. Thomas Nashe (1567–1600?) In his The Unfortunate Traveler asks the rhetorical question whether anyone has ever heard of a more divine muse than Kit Marlowe.

In the 19th century, Marlowe's fame rose again after a long period of judgments motivated by normative art. He is referred to as "the father and founder of English dramatic poetry" (John Addington Symmonds 1884), "the father of the English drama" ( AH Bullen 1885) and "the most important of Shakespeare's predecessors" (Clifford Leech). Some nineteenth-century literary scholars call Marlowe a "Shakespearean genius."

- Algernon Swinburne (1837–1909) called him the father of "English tragedy" and the absolute and divinely gifted creator and inventor of the English blank verse, who must be seen at the same time as a teacher and guide for Shakespeare. (The blank verse introduced Surrey into English literature before Marlowe .)

- In 1936, the English literary scholar Frederick S. Boas saw the deeply classic element of Marlowe's genius in the way he translated thoughts and emotions into rhythmic language with perfect precision

- Frank Percy Wilson recognized Marlowe's dramatic genius in 1953 in his first performed piece Tamburlaine . In his opinion, he did not become a playwright because of any circumstances, he was a "born playwright" from the start.

- In 1964, Irving Ribner was convinced that the reassessment of Marlowe had only just begun: "Every facet of Marlowe's genius is likely to be freshly explored and a new understanding may emerge to which we more generally give our assent".

The intensive research into Marlowe's works over the past 50 years has led to a differentiation of the positions represented and to very different characteristics and evaluations of Marlowe (for example as a romantic rebel, as an Orthodox Christian playwright, as a man of moral ambiguity, etc.).

Literary criticism has repeatedly claimed that Marlowe's poems should be viewed as works of art and not as a mirror of the character of their creator. Any interpretation would otherwise run the risk of not finding what Marlowe has to offer, but what one would wish to find - armed with preconceived theories and influenced by unsecured biographical knowledge.

Works

Dramas

Dido, Queen of Carthage

He probably wrote his first play, Dido, Queen of Carthage, which is often referred to as an early work, while still studying in Cambridge around 1584 to 1586 with the support of Thomas Nashe. The historical basis and source of his piece was the fourth book of Virgil's verse epic Aeneid . In times of war, the play tells the tragic love story of the Carthaginian Queen Dido and Aeneas , who fled Troy and landed on Carthage's coast, having strayed from the actual sea route . The play was first performed by the Children of Her Majesty's Chapel in 1587 , the only unlicensed edition published in 1594 containing the title Played by the Children of Her Majesties Chappell . The unfinished piece, which shows striking stylistic parallels to Tamburlaine but also to Edward II and Hero and Leander , was completed by Thomas Nashe. The early work Dido as well as Tamburlaine stand for the limitless possibilities of the human being as an expression of the optimistic individualism of the Cambridge years.

Tamburlaine the Great

It is believed that Marlowe started work on the piece in Cambridge, since the piece Tamburlaine (Part II) must have premiered in London in autumn 1587. This was inferred from Robert Greene's preface by Perimedes (licensed March 29, 1588) in which he mentions Tamburlaine II and thus Marlowe's atheism and godlessness. From the prologue of Tamburlaine II it can also be inferred that Part II of Tamburlain came about only because of the great stage success of the first part, so that the performance of Tamburlaine Part I must have taken place at least in early 1587. His dramas were performed for Philip Henslowe by the Lord Admirals Company under the acting direction of actor and theater director Edward Alleyn . Tamburlaine was filed with the Stationers' Register on August 14, 1590 .

The piece is based on the historical figure of the Turkic-Mongolian conqueror Timur (1336–1405; Latinized Tamerlan and Tamburlaine). Marlowe's primary models were probably Pedro Mexias Sylva de Varia lecion (Seville 1543) and Perondino's Vita Magni Tamerlanis (Florence 1551).

The success of the Tamburlaine established blank verse as a means of expressing dramatic language in the Elizabethan theater. The success of the first part was so great that a sequel (Part II) was hastily written and produced as early as 1587.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

The Jew of Malta

The piece refers to the event, a few decades ago, of the siege of Malta by the Turks in 1565, which ended with the victory of the Catholic Knights of St. John . The battle is the basis of the play about the rich Barabas and the destructive self-development of private and state acts of revenge against the background of religious intolerance.

Both Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy or Hieronimo is Mad Againe and Marlowe's The Jew of Malta were probably performed by the theater company The Admiral's Men as early as 1589/90. The Jew of Malta was an instant hit and remained Marlowe's most popular play until the theaters closed in 1642. The prologue is spoken by Machiavell , and Barabas can also be seen as a "Machiavellian" villain. The Jew of Malta and the Paris Massacre illustrate the dubious nature of the amoral superman.

The printed edition of the Jew of Malta , published as Quarto 1633, contains various text revisions that may have been made by Thomas Heywood , who wrote the foreword.

The Massacre at Paris

On January 26, 1592, The Massacre at Paris was performed for the first time by the theater group Lord Strange's Men, as shown in the diary entries of the theater manager Philip Henslowe ( ne for new ), and was repeated ten times in the summer of 1594 when the theaters reopened after the plague with high income at the beginning of the performances. The piece was published around 1601. Christopher Marlowe develops his piece against the background of the recent political turmoil and crises in France, which exploded on the historic St. Bartholomew's Night or Parisian Blood Wedding on August 24, 1572. It happened days after the marriage between the Protestant Henry of Navarre and the sister of King Charles IX. of France, which should also serve the reconciliation between the denominations. Thousands of people, mostly Huguenots (the Protestant population), were murdered in the name of the King of France and his backers . The primary cause of the devastating acts of violence was an act of revenge, which resulted in a spiral of violence and counter-violence. The drama confronts two powerful and ambitious characters, the Duke of Guise and the Duke of Anjou (later King Henry III ). The murder of Henry III, with which the play closes, took place on August 2, 1589. In Henslowe's notes the play is called The Guise , so the title The Massacre of Paris was probably introduced much later than the interest in the Duke of Guise went out. The unsatisfactory condition of the text (1250 lines) that still remains today probably corresponds to a fraction of the earlier complete works; it has clearly been changed considerably.

Edward II

The drama Edward II (The Troublesome Reign and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second) was performed by the Pembrokes Men theater company in 1592, registered for publication in the Stationer's Register on July 6, 1593 (two months after Marlowe's death) and in 1594 (probably also 1593) first printed and published. It is one of the few pieces that are not in Henslowe's Diary (Diary) are listed, so nothing can be said about timing of the first performance. However, these can in part be read from the considerable echo of the unusually numerous line contents from Edward II , which were to be found in contemporary poet colleagues. (Six borrowings in Arden of Feversham , licensed April 3, 1592, printed 1592, five in Kyds Soliman and Perseda licensed November 20, 1592, four in George Peeles Edward the First, licensed October 8, 1593). Also in Lodge's Wound of Civil War, licensed May 24, 1594, in Nashes Summers Last Will, published in The Battle of Alcazar 1594, in Peeles Honor of Garter 1593. From these observations it was deduced that the play Edward II in the second Half of 1591 or first half of 1592 must have been performed publicly.

Edward II reflects on a drama in which the panorama of the historical background is no longer the priority, but the character of the ruler himself. All scenes are arranged to work out him. At the same time, a female character, Queen Isabella, Edward's wife, is founded in his change to evil. Marlowe shows a state that is drifting towards its downfall, in which power and law are just empty phrases and which appears cruel and absurd in its arbitrariness.

- Content. King Edward publicly loves his favorite Gaveston. He forgets about the business of government and exposes his royal dignity to ridicule. The court opposed him openly, with Mortimer at their head. Edward is forced to part with his lover. Queen Isabella tries to win back her husband's favor. Finally, further conflicts force armed conflict. Gaveston is caught and murdered. Edward collects all the power still available to him and begins to rage bestially against his opponents. All leading aristocrats fall victim to his campaign of revenge except for his opponent Mortimer, who manages to escape to France, where his humiliated Isabella and her son, who later became Edward III, are waiting for him. They form an army and march victorious against the King of England. Edward is forced to renounce the rule that he nominally must continue to exercise. In reality, Queen Isabella and Mortimer, who has become her lover, run the government. While the once deluded and arrogant Edward is becoming more and more of a silent figure of suffering, the new rulers now turn out to be tyrants. What remains is Edward, naked, humiliated and finally brutally murdered, lost and deprived of all illusions. The murder calls Edward's son on the scene, who seizes power, kills Mortimer and casts the mother out.

At the same time, Shakespeare was here through Marlowe to a large extent to the form of his Henry VI. has been brought. Bertolt Brecht and Lion Feuchtwanger submitted an adaptation of the drama by Marlowe in 1923. A new arrangement comes from Ewald Palmetshofer : Edward II. I am love according to Christopher Marlowe, Wiener Festwochen 2015

Epic and lyric

Marlowe's (presumably unfinished) verse epic Hero and Leander and the well-known poem The Passionate Shepherd to His Love , often quoted in other works and later often parodied, have also survived .

Hero and Leander

Marlowe used the late Greek version of the Alexandrian poet and grammarist Musaios (5th century AD) as a template for the epic poem Hero and Leander . His language is extremely splendid and rich in images and filled with ancient allusions.

"About her neck hung chains of pebble-stone / Which, lightened by her neck, like diamonds shone gloves./ She ware no, for neither sun nor wind / would burn or parch her hands, but to her mind / Or warm or cool them, for they tool delight / To play upon those hands, they were so white ... "

"Translation: Chains of pebbles hung around her neck / which, illuminated from her neck, shone like diamonds. / She wore no gloves, because neither sun nor wind / wanted to burn or dry out her hands, but just as she liked / warmed." or did they cool them, because they liked / to play on these hands, they were so white ... "

Due to the elegance of his verses and the basic mood of subtle eroticism and passion, Hero and Leander is counted among the most beautiful poetic creations of the English Renaissance.

The love epic, which literary scholars count among Marlowe's late works, appeared in two different versions in 1598, the first unfinished, unfinished version as an 818-line poem that ends with the editor's inset “desunt nonnulla” (“something missing”) and the second Version in which the poem is divided into two “sestiads” continued by George Chapman who added four more sestiads.

The Passionate Shepherd

Although the time of the famous poem The Passionate Shepherd (The Shepherd in Love) with the lyrical poem Come Live with Me and Be My Love is unknown, it is assigned to the later 1580s in particular because it was common during this period, including by Marlowe himself , was picked up in quotes, for example, Dido, Tamburlaine, the Jew, and Edward II. such a lyrical song emerged, for example in the ballroom scene at the beginning of of Richard Loncraine staged Shakespeare film Richard III on (Come live with me, and be my love, and we will all the pleasures prove) . It appeared in various print editions from four to seven dies , with a four-stanza version printed in The Passionate Pilgrim (1599) and a six-stanza version in Englands Helicon (1600).

Translations

Ovid elegies

As a rule, the free line-to-line translation of Ovids Amores from Latin is regarded as Marlowe's first poetic work, which he probably wrote as a student in Cambridge around 1584/85. The date of initial publication is unknown. Experts believe that it must have been printed in the second half of the 1590s. They were publicly burned in 1599 under church censorship. Ovid's elegies appeared in three different editions, the first two containing only ten poems, while the third complete edition contained three books with 48 poems.

Lucan's first book

Marlowe's translation of Lucan's first book of Pharsalia , an epic poem about the battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC. Chr. Between Caesar and Pompey Magnus was filed on September 28, 1593 together with Hero and Leander in the Stationer's Register. The publication did not take place before 1600. Experts do not completely agree whether the translation can be ascribed to an early or late creative period of Marlowe.

Marlowe's assignments

Gravestone for Roger Manwood

A poem by Marlowe in the form of a short Latin tombstone for Sir Roger Manwood (1525–1593), Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer , a lawyer from Canterbury, has been preserved as a manuscript. One can assume with a certain plausibility that it must have been written between December 1592, the time of Roger Manwood's death, and May 1593, the time of Marlowe's death. The Latin epitaph was found on the back of the title page of a copy (1629) by Marlowe and Chapman's Hero and Leander .

Epistle dedicated to Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke

Marlowe is also considered to be the author of a Latin prose of a verse epistle dedicated to Mary Sidney Herbert , Countess of Pembroke (sister of Philip Sidney ), which served as the preface to Thomas Watson's poem Amintae gaudia from 1592, and which throws an astonishing light on Marlowe's career as a poet and therefore is printed today alongside his poems.

Marlowe in the Shakespeare authorship debate

The so-called authorship debate is conducted outside of institutionalized Shakespeare research. Within this debate, Christopher Marlowe has been one of the most frequently mentioned Shakespeare authorship candidates since a publication by Calvin Hoffman in 1955. Documentary evidence linking Marlowe with the works of Shakespeare goes back to the first half of the 19th century. The most lasting effect had Calvin Hoffman's book The murder of the man who was Shakespeare from 1955. The only German-language monograph on the Marlowe theory assumes that Shakespeare's Christopher Marlowe, the recognized greatest playwright, poet genius and “superstar” of his time until his "supposed" death in 1593 because of life-threatening accusations on the part of the state and the church under the pretense of his death, gave up his identity and name, lived on in anonymity with the support of the crown and wrote under numerous pseudonyms (including William Shakespeare) and in high terms Died at the age of 91 on October 13, 1655 in the Jesuit college in Gent (Belgium) under the name "Tobias Mathew". The name "Shakespere" as one of his pseudonyms was chosen at the beginning because William Shakespere from Stratford agreed in return for a fee to mask Christopher Marlowe "in person" to increase security. Marlowe's eligibility for Shakespeare's authorship was dealt with in the "Terra-X series" as the documentary Das Shakespeare-Rätsel (Atlantis Film, director: Eike Schmitz), which was first broadcast by ZDF in 2011 and can be accessed in the ZDF media library can. The stylometric analysis of the apocryphal dramas, which was expanded to include Marlowe's dramas and was carried out with the currently most comprehensive program R Stylo , arrived at completely different results, according to which Shakespeare began his apprenticeship as a playwright in London around 1585 and Marlowe only the two Tamerlane dramas and a play called Locrine is awarded. Marlowe's share in Edward II is stated to be between 20 and 25%. The authors of the alleged Marlowe dramas are considered to be Thomas Nashe, Thomas Kyd and William Shakespeare by measuring the stylistic correspondence with the reference texts. Profit-hungry printers probably saw the spectacular death of Marlowe as an opportunity to sell dramatic texts with the name of a blasphemous atheist.

swell

Work editions

- CF Tucker Brooke (Ed.): The Works of Christopher Marlowe . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1910.

- Tambourine

- Tamburlaine, Part II

- Doctor Faustus

- The Jew of Malta

- Edward II

- Dido

- The Massacre at Paris

- Hero and Leander

- Lyric poems

- Ovid's Elegies

- The First Book of Lucan

- Robert H. Case (Ed.): Works and Life of Christopher Marlowe . Methuen, London 1930/33.

- The life of Marlowe and the tragedy of Dedo, queen of Carthage

- Tamburlaine the Great

- The jew of Malta

- Poems

- The tragical history of Doctor Faustus

- Edward II

- The Plays of Christopher Marlowe. Oxford University Press (printer: Vivian Ridler), London 1939 (= The World's Classics . Volume 478); 8 reprints 1946 to 1966.

- The first part of Tamburlaine the Great

- The second part of Tamburlaine the Great

- The tragical history of Doctor Faustus

- The Jew of Malta

- Edward the Second

- The massacre at Paris

- The tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage

- Roma Gill (Ed.): The Complete Works of Christopher Marlowe . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1987 ff.

- All Ovid elegies

- Doctor Faustus

- Edward II

- The jew of Malta

- Tamburlaine the Great

Biographies / essays

- John E. Bakeless: The Tragical History of Christopher Marlowe . Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. 1970 (reprint of the Cambridge / Mass. 1942 edition, two volumes)

- Emily C. Bartels (Ed.): Critical Essays on Christopher Marlowe . Hall Books, New York 1997, ISBN 0-7838-0017-7 .

- Harold Bloom (Ed.): Christopher Marlowe . Chelsea House, Broomall, Pa. 2002, ISBN 0-7910-6357-7 .

- Frederick S. Boas: Christopher Marlowe. A Biographical and Critical Study . Clarendon, Oxford 1966 (reprint of the Oxford 1940 edition)

- Rodney Bolt: History play. The lives and afterlife of Christopher Marlowe . HarperCollins, London 2004, ISBN 0-00-712123-7 .

- Lois M. Chan: Marlowe Criticism. A Bibliography . Hall Books, London 1978, ISBN 0-86043-181-9 .

- Patrick Cheney (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe . University Press, Cambridge 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-52734-7 .

- Douglas Cole: Christopher Marlowe and the Renaissance of Tragedy . Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. 1995, ISBN 0-313-27516-5 .

- Mark Eccles: Christopher Marlowe in London (Harvard studies in English). Octagon Books, New York 1967 (reprinted Cambridge 1934)

- Kenneth Friedenreich: Christopher Marlowe, An Annotated Bibliography of Criticism Since 1950 . Scarecrowe Press, Metuchen N.J. 1979, ISBN 0-8108-1239-8 .

- Graham L. Hammill: Sexuality and form. Caravaggio, Marlowe, and Bacon . University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill. 2000, ISBN 0-226-31518-5 .

- Park Honan: Christopher Marlowe. Poet & Spy . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-818695-9 .

- Lisa Hopkins: Christopher Marlowe. A literary life . Palgrave Books, Basingstoke 2000, ISBN 0-333-69825-8 .

- Lisa Hopkins: A Christopher Marlowe chronology . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2005, ISBN 1-4039-3815-6 .

- Leslie Hotson: The Death of Christopher Marlowe . Russell & Russell, New York 1967 (reprint of the London 1925 edition)

- Roy Kendall: Christopher Marlowe and Richard Baines. Journeys Through the Elizabethan Underground . University Press, Madison, NJ 2004, ISBN 0-8386-3974-7 .

- Constance B. Kuriyama: Christopher Marlowe. A renaissance life . Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY 2002, ISBN 0-8014-3978-7 .

- Clifford Leech: Marlow. A collection of critical essays . Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs 1964

- David Riggs: The World of Christopher Marlowe . Holt Books, New York 2005, ISBN 0-8050-7755-3 .

- Alfred D. Rowse: Christopher Marlowe. A biography . Macmillan, London 1981, ISBN 0-333-30647-3 (former title: Marlowe, his life and works )

- Arthur W. Verity: The influence of Christopher Marlowe on Shakespeare's early style . Folcroft Press, Folcroft, Pa. 1969 (reprint of Cambridge edition 1886)

- Judith Weil: Christopher Marlowe, Merlin's Prophet . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1977, ISBN 0-521-21554-4 .

- Paul W. White (Ed.): Marlowe, history, and sexuality. New critical essays on Christopher Marlowe . AMS Press, New York 1998, ISBN 0-404-62335-2 .

- Frank P. Wilson: Marlowe and the Early Shakespeare . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1973 (reprint of the Oxford 1953 edition)

- Richard Wilson: Christopher Marlowe . Longman, London 1999, ISBN 0-582-23706-8 .

Studies on literary work

- Johannes H. Birringer: Marlowe's “Dr. Faustus "and" Tamburlaine ". Theological and theatrical perspectives . (= Trier studies on literature. Volume 10). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-5421-7 .

- Fredson Bowers (Ed.): Complete Works of Christopher Marlowe . University Press, Cambridge 1981, ISBN 0-521-22759-3 . (two volumes, reprint of the London edition, 1974)

- Douglas Cole: Christopher Marlowe and the Renaissance of Tragedy . Praeger, Westport, CT 1995.

- Lisa Hopkins: Christopher Marlowe. A literary life . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, ISBN 0-333-69825-8 .

- Hugo Keiper: Studies on the representation of space in the dramas of Christopher Marlowe. Dramaturgy and depicted reality . Verlag Die Blaue Eule, Essen 1988, ISBN 3-89206-230-7 .

- Clifford Leech: Christopher Marlowe. Poet for the Stage . AMS Press, New York 1986, ISBN 0-404-62281-X .

- Harry Levin: Science Without a Conscience: Christopher Marlowe's> The Tragicall History of Doctor Faustus <. In: Willi Erzgräber (Ed.): Interpretations Volume 7 · English literature from Thomas More to Laurence Sterne . Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1970, pp. 36-65.

- Ruth Lunney: Marlowe and the popular tradition. Innovation in the English drama before 1595 . Manchester University Press, Manchester u. a. 2002, ISBN 0-7190-6118-0 .

- Ian McAdam: The irony of identity. Self and imagination in the drama of Christopher Marlowe . University of Delaware Press et al. a., Newark, Del. u. a. 1999, ISBN 0-87413-665-2 .

- Wilfried Malz: Studies on the problem of metaphorical speech using the example of texts from Shakespeare's Richard II. And Marlowe's Edward II. (= European university publications, series 14, Anglo-Saxon language and literature. 105). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1982, ISBN 3-8204-5824-7 .

- Alan Shepard: Marlowe's soldiers. Rhetorics of masculinity in the age of the Armada. Ashgate, Aldershot, Hants, et al. a. 2002, ISBN 0-7546-0229-X .

- Stevie Simkin: Marlowe. The Plays . Palgrave, Basingstoke 2001, ISBN 0-333-92241-7 .

- William Tydeman, Vivien Thomas: Christopher Marlowe. The Plays and Their Sources . Routledge, London 1994, ISBN 0-415-04052-3 .

- Hubert Wurmbach: Christopher Marlowe's Tamburlaine Dramas. Structure, control of reception and historical significance. A contribution to drama analysis. (= English research. 166). Winter, Heidelberg 1984, ISBN 3-533-03215-9 .

Marlowe as a historical novel and film character

The brilliance of the person of Marlowe and the circumstances of his life and death have prompted various authors and writers over the decades to use him as a historical fictional character in various forms. Marlowe is also occasionally taken up as a character in feature films.

- Fiction

- Lisa A. Barnett , Elizabeth Carey , Melissa Scott : Armor of Light . New England SF Assoc., Framingham, Ma. 1997, ISBN 0-915368-29-3 (therein Marlowe is portrayed as a man who survived his attempted assassination by rescuing Sir Phillip Sidney.)

- Anthony Burgess : The Devil's Poet. Roman ("A Dead Man in Deptford"). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-608-93217-8 (this novel contains a description of Marlowe and his death. According to Burgess, it is a fiction which, however, nowhere deviates from historical facts.)

- Robin Chapman: Christoferus or Tom Kyd's Revenge . Sinclair-Stevenson, London 1993, ISBN 1-85619-241-5 . German edition: The Queen's Poet. Novel. Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th.Knaur Nachf., Munich, 1994, ISBN 3-426-63020-6 (Under torture, Thomas Kyd denounces his friend Marlowe as an atheist. Marlowe dies under mysterious circumstances after his imprisonment; Ky uncovered the plot behind it. )

- Judith Cook: The Slicing Edge of Death. Simon & Schuster, 1993, ISBN 0-671-71590-9 .

- Antonia Forest: The Player's Boy . Girls Gone By Edition, Bath 2006, ISBN 1-904417-92-2 (Children's book; Marlowe appears in four chapters. A fictional character Nicholas witnesses Marlowe's death in the Deptford house, who later became an actor in the same company as William Shakespeare will.)

- Neil Gaiman : Sandman. Comic ("The Sandman"). Edition Tilsner, Bad Tölz 2003 (two volumes, Marlowe and Shakespeare appear briefly in a pub. Marlowe is portrayed as a great writer together with the young inexperienced Shakespeare.)

- 2003, ISBN 3-933773-66-0 .

- 2003, ISBN 3-933773-68-7 .

- Lisa Goldstein : Under the sign of the sun and moon. Roman ("Strange Devices of the Sun and Moon"). Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-596-12216-3 (a fantastic novel in which Marlowe plays a central role.)

- Andreas Höfele : The informer. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-518-39415-0 (about the English spy Robert Poley and his involvement in Marlowe's murder).

- Dieter Kühn : Secret agent Marlowe. Novel of a murder . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-041510-3 (Marlowe's secret service dossier can be read in it, which presents him as an English-French double agent.)

- Andy Lane: The Empire of Glass . Dr. Who Books, London 1995, ISBN 0-426-20457-3 (Lanes describes Marlowe who outlived his killer by 16 years.)

- Rosemary Laurey: Immortal Kisses ("Kiss me forever"). Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-89897-728-9 (a romance novel in which Marlowe, as a 400-year-old vampire, is one of the two main characters.)

- Philip Lindsay One Dagger for Two . Hutchinson, London 1974 (Reprint of the London 1932 edition; Lindsay treats Marlowe as the central figure with various speculations about his death.)

- Leslie Silbert : The Marlowe Code ("The Intelligencer"). Blanvalet Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7645-0139-1 (the novel links Marlowe as a possible spy of his time with contemporary events.)

- Gerald Szyszkowitz : The false face or Marlowe is Shakespeare, 2015 (in this and the two following plays, Marlowe goes abroad as a spy and writes the plays for Shakespeare)

- Gerald Szyszkowitz: Marlowe and the Lope de Vega's mistress, 2016

- Gerald Szyszkowitz: Marlowe's Romeo and Juliet in Crete, 2017

- Harry Turtledove : Ruled Britannia. A novel of alternate history . Tor Books, New York 2002, ISBN 0-451-45915-6 (set in a fictional Catholic-ruled England; Marlowe appears as a contemporary and friend of Shakespeare.)

- Alan Wall: The School of Night . Vintage Books, London 2001, ISBN 0-09-928586-X ( Using a protagonist-narrator model, Wall constructs a theory in which he identifies a not-really-dead Marlowe as the author of Shakespeare's works.)

- Louise Welsh : Tamburlaine must die. Roman ("Tamburlaine Must Die"). Kunstmann, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-88897-384-8 (this novel is based on a fictional theory of the last two weeks of Marlowe's life.)

- Connie Willis : Winter's tale. In: dies .: Impossible Things. Short stories . Bantam Books, New York 1994, ISBN 0-553-56436-6 (Marlowe is one of the main characters in this story.)

- Movie

- Rupert Everett played Marlowe in the 1998 film Shakespeare in Love , in which he helped Shakespeare write Romeo and Juliet . His last words are a happy "Well, I'm off to Deptford!"

- In 2013, John Hurt played the old vampire Christopher Marlowe in Only Lovers Left Alive . Little by little you learn in the film that he wrote all of Shakespeare's works and left all the glory to the little man for what now embittered him.

Web links

- Literature by and about Christopher Marlowe in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Christopher Marlowe in the German Digital Library

- Works by Christopher Marlowe at Zeno.org .

- Marlowe bibliography (English)

- Works by Christopher Marlowe (English)

- Works by Marlowe in the Perseus Project (English)

- The Marlowe Society (English)

- Marlowe Lives! (English)

- Peter Marlowe Fareys page (English)

- Great Monologues from Marlowe's dramas (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b J. A. Downie, JT Parnell: Constructing Christopher Marlowe . Cambridge Press, 2000.

- ^ Peter Farey: The Spelling of Marlowe's Name

- ↑ a b Christopher Marlowe - Some biographical facts

- ↑ PD Mundy: The ancestry of Christopher Marlowe . N & Q 1954, pp. 328-331.

- ^ A b C. F. Tucker Brooke: The life of Christopher Marlowe. Methuen NY Dial Press, London 1930.

- ↑ D. Grantley, P. Roberts (Eds.): Christopher Marlowe and English Renaissance Culture. 1996.

- ^ RI Page: Christopher Marlowe and the Library of Matthew Parker . N&Q 1977

- ^ Epitaph to Sir Roger Manwood, Attributed to Christopher Marlowe, translation by Peter Farey

- ↑ a b W. F. Prideaux, N&Q, 1910.

- ↑ It was concluded that John Benchkin of Canterbury, proven consemester of Marlowe at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, must have been the son of the widow Benkyn, who caused Marlowe to have his signature (and that of Marlowe's father) as a witness when she opened her will in 1585 ) afford to

- ^ A b William Urry: Marlowe and Canterbury . TLS, February 13, 1964.

- ↑ K. Stählin: Sir Francis Walsingham and his time . Heidelberg, 1908.

- ^ C. Read: Walsingham and Burghley in Queen Elizabeth's Privy Concil. The English Historial Review, 28, 1913.

- ↑ Calvin Hoffman: The Man who was Shakespeare (1955) p. 179.

- ↑ Frances Walsingham on thepeerage.com , accessed September 14, 2016.

- ↑ J. Bakeless: The Tragicall History of Christopher Marlowe. 1941, Oxford University Press Vol I + II

- ↑ J. Bakeless: Christopher Marlowe. W. Morrow and Company (1937)

- ↑ Katherine Benchkin's Will - John Moore's evidence , (Kent Archives Office, Maidstone, PRC 39/11 f. 234, from the transcript by William Urry: Christopher Marlowe and Canterbury. Pp. 127–129)

- ↑ DD Wallace: From Eschatology to Arian Heresy. The case of Francis Kett . Harvard Theological Review 1974.

- ^ The Marlowe Society: Christopher Marlowe's Work ( Memento January 5, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b c M. Eccles: Christopher Marlowe in London . 1934, Harvard Univ. Press

- ^ W. Besant: The London of Good Queen Bess . Harpers New Monthly Magazine 1891.

- ↑ a b c d A. K. Gray: Some Observations on Christopher Marlowe . Government Agent, PMLA, vol. 43, no. 3 (September 1928)

- ↑ Letter From The Privy Council - 29 June 1587 (PRO Privy Council Registers PC2 / 14/381)

- ↑ a b c d Tucker Brooke: The Marlowe Canon. PMLA, 1922.

- ↑ Philip Henderson: Christopher Marlowe. 2nd Edition. ed. (1974)

- ^ FG Hubbard: Possible Evidence for The Date of Tamburlaine . Modern Language Association, 1918.

- ↑ Irving Ribner: Greene's Attack on Marlowe: Some Light on Alphonsus and Selimus. Studies in Philogy, 1955.

- ↑ SP Cerasano: Philip Henslowe, Simon Forman and the Theatrical community of the 1590s. Shakespeare Quarterly 1993.

- ↑ a b tudorplace.com

- ↑ British Library Landdowne MS 71, f. 3

- ↑ ESJ Brooks: Marlowe in 1589-92? TLS 1937

- ↑ J. Baker, N&Q, 1997, p. 367.

- ^ FS Boas: Christopher Marlowe: A Biographical and Critical Study. 1940, Clarendon

- ↑ DN Durant: Bess of Hardwick: Portrait of an Elizabethan Dynast. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. London 1977.

- ^ TW Baldwin: On the Chronology of Thomas Kyd's Plays. In: Modern Language Notes. XL, 1925, pp. 343-349.

- ^ RB Wernham: Christopher Marlowe in Flushing in 1592. In: English Historical Review. Vol. 91, 1976, p. 344 f.

- ^ E. Seaton: Robert Poley's Ciphers . The Review of English Studies, 1931.

- ↑ P. Alexander, TLS 1964

- ↑ D. Riggs: The World of Christopher Marlowe

- ↑ Greene's Groats-worth of Wit transcript (PDF)

- ^ A b J. Briggs: Marlowes Massacre at Paris: a reconsideration. Review of English Studies 34, 1983.

- ↑ Thomas Rymer, Foedera, 26 (1726), 201; quoted in The Writings of John Greenwood and Henry Barrowe 1591-1593 (Eds.): Leland H. Carlson (Oxford, 1970), p. 318.

- ^ A b Arthur Freeman: Marlowe, Kyd, and the Dutch Church Libel . English Literary Renaissance 3, 1973.

- ↑ A libel, Fixte vpon the French Church Wall, in London. Anno 1593o

- ^ Acts of the Privy Council (Ed.): John Dasent, N, p. 24 (1901), 1592-1593, 222.

- ↑ British Library BL Harley MS.6848 ff. 188-9

- ↑ Kyd's Accusations

- ↑ Kyd's Letter To Sir John Puckering

- ^ A b E. de Kalb: Robert Poley's Movements as a Messenger of the Court. 1588 to 1601 Review of English Studies, Volume 9, No. 33

- ↑ a b Peter Farey: Marlowes's Sudden And Fearful End: Self-Defense, Murder or Fake?

- ↑ a b Privy Council Registers (PRO) PC2 / 20/374 (May 20, 1593)

- ^ The 'Remembrances' Against Richard Cholmeley

- ^ Further Accusations Against Richard Cholmeley

- ↑ The 'Baines Note'

- ^ Original, British Library (BL) Harley MS.6848 ff. 185-6.

- ↑ copy Harley MS.6853 ff.307-8

- ^ A b "The Reckoning" Revisited

- ^ Leslie Hotson: The Death of Christopher Marlowe. 1925, Nonsuch Press, London

- ^ The Coroner's Inquisition

- ↑ HA Shield: The death of Marlowe. N&Q, 1957.

- ↑ LBQE, Read, 484

- ^ Alan Haynes: The gunpowder plot. Sutton 2005.

- ↑ L. Hopkins: New light on Marlowe's Murderer. N&Q, 2004.

- ↑ Charles Nicholl: The reckoning: The murder of Christopher Marlowe 2002, 2nd edition

- ^ FS Boas: Marlowe and his Circle: A Biographical Survey Clarendon Press

- ↑ Ingram Frizer's pardon