The Spanish tragedy

The Spanish Tragedy (English. The Spanish Tragedy, or Hieronimo is Mad Again ) is an Elizabethan tragedy by Thomas Kyd , which was written between 1582 and 1592. In its time, the play was extremely popular and made a significant contribution to establishing the new genre of revenge tragedy in English literature. Several other Elizabethan authors, including William Shakespeare , Ben Jonson and Christopher Marlowe , alluded to or parodied the Spanish tragedy in their works .

Many elements of Spanish tragedy later appeared in Shakespeare's Hamlet , including the play in the game , which is used to convict a murderer, or the spirit seeking revenge. Thomas Kyd is also regularly thought to be the author of the unspecified original Hamlet , who may have been one of Shakespeare's sources.

action

original version

Before the start of the play, the Viceroy of Portugal rebelled against Spanish rule. The Portuguese were defeated in a battle and their leader, Balthazar, son of the viceroy, was captured; the Spanish officer Andrea was murdered by Balthazar. His spirit and the spirit of vengeance (present on stage throughout the play) act as a chorus - at the beginning of each act Andrea laments the injustices, while vengeance assures him that those to whom it is due will receive their well-deserved punishment . A subplot describes the enmity of two Portuguese noblemen, one of whom tries to convince the viceroy that his rival murdered the missing Balthazar.

Lorenzo, the king's nephew, and Andrew's best friend Horatio argue about which of them captured Balthazar. Although it becomes clear early on that in truth Horatio defeated Balthazar and Lorenzo stole the partial glory, the king puts Balthazar under Lorenzo's care and divides the proceeds of the victory between the two. Horatio comforts Lorenzo's sister Bel-Imperia, who was in love with Andrea against the wishes of her family. Despite her earlier feelings, she soon falls in love with Horatio, partly due to her desire for revenge. She plans to torment Balthazar, who is in love with her.

The royal family sees Balthazar's love for Bel-Imperia as an opportunity to restore peace with Portugal and plans a wedding. Horatio's father, Marshal Hieronimo, is supposed to put on an entertainment piece for the Portuguese ambassador. Lorenzo, who suspects that Bel-Imperia has found a new lover, bribes her servant Pedringano and learns that it is Horatio. He convinces Balthazar to help him murder Horatio during a meeting with Bel-Imperia. Hieronimo and his wife Isabella find their son's body hanged and stabbed, driving Isabella insane. Changes to the original text expanded this scene to the effect that Hieronimo also briefly lost his mind.

Lorenzo locks Bel-Imperia away; however, she manages to send Hieronimo a letter written in her blood, telling him that Lorenzo and Balthazar are the murderers of Horatios. Hieronimo's questions and attempts to see Bel-Imperia show Lorenzo that he knows something. Suspected that Balthazar's servant Serberine had betrayed her, Lorenzo Pedringano persuades Pedringano to murder him too, and then has him arrested in order to also calm him down. Hieronimo as appointed judge sentenced Pedringano to death. Pedringano expects a pardon from Lorenzo; the latter left him in this belief until his execution.

Lorenzo manages to prevent Hieronimo from seeking justice by convincing the king that Horatio is alive. He prevents Hieronimo from visiting the king by claiming that he is too busy. Isabella killed herself shortly before that. Hieronimo loses his temper, curses incoherently and thrusts his dagger into the ground. Lorenzo explains to the king that Hieronimo cannot handle the new wealth of his son Horatio (the ransom for Balthazar from the Portuguese viceroy) and is mad with jealousy. When he regains his senses, he and Bel-Imperia feign reconciliation with the murderers and together stage a play called Soliman and Perseda . During the play, they stab Lorenzo and Balthazar in front of the king, viceroy and duke of Castile (the father of Lorenzo and Bel-Imperia). Bel-Imperia kills himself and Hieronimo explains his motives to the audience, but does not reveal Bel-Imperia's complicity. Finally he bites out his tongue so as not to be able to speak under torture and subsequently kills the duke and himself. Andrea and the vengeance are satisfied.

The extensions of 1602

The fourth quarto edition from 1602 added five passages with a total of 320 verses to the original version. The largest of these is a complete scene, most of which includes Hieronimo's conversation with a painter. It falls between scenes III.xii and III.xiii and is often listed as scene III.xiia.

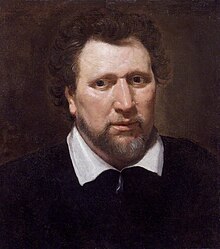

Henslowe's diary mentions two payments to Ben Jonson for additions to the Spanish Tragedy , dated September 25, 1601 and June 22, 1602. However, research has overwhelmingly rejected the view that Jonson was the author of the supplements. Her style is judged to be atypical of Jonson. In addition, Henslowe Jonson paid several pounds for his additions, which seems too much for 320 verses. In addition, John Marston seems to parody the "painter scene" as early as 1599 in his play Antonio and Mellida , which suggests that the scene must have existed at the time and must have been known to the public. The five additions from 1602 could have been created for the performance of Admiral's Men in 1597. Scholars have made various speculations about her authorship, including Thomas Dekker , John Webster, and Shakespeare.

Interpretations

Themes and motifs

A lengthy scholarly debate sparked the moral value of vengeance, the most obvious theme of the play. One question is whether the moral error that can be interpreted into Hieronimo's plans for revenge really goes back to himself. Steven Justice believes that the play does not condemn Hieronimo as much as the society that produced this tragedy. He argues that Kyd used the revenge tragedy to stage popular ideas about Catholic Spain. Kyd would therefore try to convey a negative image of Spain by showing how the Spanish court did not leave Hieronimo any acceptable options for action. So the court would force Hieronimo to seek vengeance in his quest for justice.

Another motive of the Spanish tragedy is the tragic itself in the form of murders and death. An extremely large number of characters are killed or almost killed in the course of the play: Horatio is hanged, Pedringano is hanged, Alexandro is almost burned, Villuppo is probably tortured and burned. The high frequency of murders is already discussed at the beginning of the play by Andrea in the underworld and runs through to the last scene. Molly Smith considers the decade in which the piece was written to be an important factor in this subject.

In addition, the motif of vengeance could also have a historical component - according to Glenn Carmann, the piece subliminally addresses the conflict between England and Spain. The Spanish Armada may have become the subject of a political joke.

structure

An important element in the structure of the piece is the play in the game. The Spanish tragedy initially tells the background of Hieronimo's quest for revenge. He initially appears as a minor character, but eventually becomes the main participant in the plot, which revolves around revenge. As he becomes the main character, the real plot becomes clear and reveals the centrality of vengeance. Kyd uses the path to revenge motif to show the characters' internal and external conflicts. Ultimately, the real vengeance takes place during the play that Hieronimo directs - making it the central scene of the tragedy. The resolution ultimately takes place in the declaration to the king. The in-game play is not described prior to its performance, which makes it a highlight.

Critics have noted that the Spanish tragedy corresponds to the Seneca conception of the tragedy . The separation of the characters, the emphatically bloody climax and the vengeance itself put the piece in the tradition of some famous ancient pieces. Kyd points out references to ancient tragedies by using Latin in his play, although he allows Christian motifs to collide directly with ancient ones. He also alludes directly to three ancient tragedies. The Spanish tragedy is said to have profoundly influenced the style of various Elizabethan revenge tragedies , of which Hamlet is the most significant.

Influences

Spanish tragedy has been influenced by various works, mainly medieval ones and those by Seneca, from which she draws the tragic, bloody plot, the rhetoric of the "terrible", the theme of the spirit and typical motifs for revenge. The figures of the ghost of Andrea and that of Vengeance form a choir that corresponds to that of Thyestes . The ghost describes its journey into the underworld and finally calls for a punishment influenced by Thyestes, Agamemnon and Phaidra . The use of onomastic rhetoric, in which characters like Hieronimo play with their names, also goes back to Seneca. Hieronimo himself also alludes to Seneca's Agamemnon and Troades . The figure of the old man, Senex, is read as a direct reference to Seneca.

Typical characteristics for Seneca are undermined in the Spanish tragedy , such as the figure of the spirit. With Kyd, the spirit is part of the choir, unlike in Thyestes , where it disappears after the prologue. In addition, he does not give the audience any information about the plot or its outcome. Rather, the spirit corresponds to those in metric medieval form who return and comment on the plot. The figure of vengeance also corresponds more closely to medieval drama.

Text history

Dating

In the introduction to his play Bartholomew Fair (1614), Ben Jonson mentions the Spanish tragedy and gives its age as "five and twenty or thirty years" (twenty-five or thirty years). If this information is taken literally, it results in a date of origin between 1584 and 1589, which agrees well with the known information. Some critics take the view that the piece makes no allusions to the battle with the Spanish Armada of 1588 and therefore see 1587 as the most likely year of composition. Other assessments deviate by a year in one direction or the other. In his edition of the play Philip Edwards assumes a time window from 1582 to 1592 and considers a date around 1590 to be the most likely.

Performance history

No reports have survived of the earliest performances of the piece in the 1580s. Lord Strange's Men performed a play called Jeronimo on March 14, 1592 , and repeated the performance 16 more times by January 22, 1593. It is uncertain whether Jeronimo was the Spanish tragedy . Another possibility would be The First Part of Hieronimo (printed 1604), an anonymous precursor to Kyd's drama; It is also conceivable that different performances were different pieces.

The Admiral's Men resumed Kyd's play on January 7, 1597 and performed it twelve times by July 19; together with Pembroke's Men they performed it again on October 11th of the same year. Records by Philip Henslowe suggest that the piece was also performed in 1601 and 1602. In addition, there were performances by English theater troupes in Germany in 1601; German and Dutch translations were also made.

Edition history

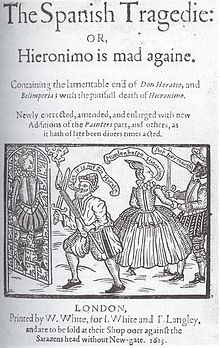

Kyd's piece was entered in the Stationers' Register on October 6, 1592 by a bookseller named Abel Jeffes . The piece was almost certainly published as an undated quarto edition before the end of 1592 . This first edition was printed by Edward Allde and published not by copyright holder Jeffes, but by Edward White, another bookseller. On December 18, 1592, the Stationers' Company decided that both Jeffes and White had violated the Guild's laws by printing someone else's work. She sentenced both to a fine of 10 shillings and had the books destroyed, which is why only one copy of the first quarto edition of the Spanish Tragedy has survived . However, its title page mentions an even earlier edition, probably by Jeffes, of which no copy has survived.

In 1594 the popular piece was reissued. Obviously trying to find a compromise between the competing booksellers, the title page attributes the second quarto edition to Abell Jeffes, “to be sold by Edward White”. On August 13, 1599, Jeffes transferred his copyright to William White, who published a third edition that same year. White himself in turn transferred his rights on August 14, 1600 to Thomas Pavier , who published the fourth edition (which William White printed for him) in 1602. This edition contained five extensions of the previous text and was reissued in 1610, 1615 (in two editions), 1618, 1623 (in two editions) and 1633.

Authorship

All early editions were anonymous. The first reference to the author's identity appeared in Thomas Heywood's Apology for Actors in 1612 , where the play is attributed to Kyd. The style of Spanish tragedy is so similar to that of Kyd's further play Cornelia (1593) that his authorship is widely recognized in scholarship.

reception

The Spanish tragedy was decidedly influential; There are numerous mentions and allusions to be found in contemporary literature. Ben Jonson mentioned Hieronimo in the introduction to Cynthia's Revels (1600) and quoted in Every Man in His Humor (1598) from the play (act I, scene iv). In Satiromastix (1601), Thomas Dekker suggested that Jonson himself played Hieronimo in his early days as an actor.

Even decades after the piece was published, allusions can be found in other works, including Thomas Tomkis ' Albumazar (1615), Thomas Mays The Heir (1620) and Thomas Rawlins' The Rebellion (around 1638).

In the twentieth century, TS Eliot quoted the piece and its title in his poem Das Wüsten Land . In the novel Schnee by the Turkish author Orhan Pamuk , a freer staging of the Spanish tragedy is an element of the plot.

Text output

- Clara Calvo and Jesus Tronch (Ed.): Thomas Kyd : The Spanish Tragedy. Arden Early Modern Drama. Bloomsbury, London 2016. ISBN 978-1-904271-60-4

literature

- Ronald Broude: Time, Truth, and Right in 'The Spanish Tragedy' . In: Studies in Philology. Vol. 68, No. 2 (Apr. 1971), pp. 130-145. University of North Carolina Press, April 1, 2009.

- Steven Justice: Spain, Tragedy, and The Spanish Tragedy . In: Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. Vol. 25, No. 2, Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Spring, 1985), pp. 271-288. Rice University, April 1, 2009.

- Carol McGinnis Kay: Deception through Words: A Reading of The Spanish Tragedy . In: Studies in Philology. Vol. 74, no. 1 (Jan. 1977), pp. 20-38. University of North Carolina Press, April 1, 2009.

- Molly Smith: The Theater and the Scaffold: Death as Spectacle in The Spanish Tragedy . In: Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. Vol. 32, No. 2, Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Spring, 1992), pp. 217-232. Rice University

Web links

- The Spanish Tragedie on Project Gutenberg (English)

- The Spanish Tragedy

supporting documents

- ^ Thomas Kyd, The Spanish Tragedy . Philip Edwards, ed. The Revels Plays; Methuen & Co., 1959; reprinted Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1986 p. lxii.

- ^ Steven Justice: Spain, Tragedy, and The Spanish Tragedy . Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 25, No. 2, Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Spring, 1985), pp. 271-288.

- ^ Steven Justice: Spain, Tragedy, and The Spanish Tragedy . Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 25, No. 2, Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Spring, 1985), pp. 271-288.

- ^ Molly Smith: The Theater and the Scaffold: Death as Pectable in The Spanish Tragedy . Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 32, No. 2, Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Spring, 1992), pp. 217-232.

- ↑ Glenn Carman, "Apocalypse and Armada in Kyd's Spanish Tragedy." 1997. The Free Library. The Renaissance Society of America. , as seen on March 30, 2010.

- ^ Tetsuo Kishi: The Structure and Meaning of The Spanish Tragedy , viewed March 30, 2010

- ^ Janette Dillon: The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare's Tragedies . Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ^ Janette Dillon: The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare's Tragedies . Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ↑ Howard Baker: Ghosts and Guides: Kyd's 'Spanish Tragedy' and the Medieval Tragedy. Modern Philology 33.1 (1935): p. 27.

- ↑ Baker, p. 27.

- ↑ Baker, p. 33.

- ^ Scott McMillin: The Book of Seneca in The Spanish Tragedy. Studies in English Literature 14.2 (1974): p. 206.

- ↑ Baker, p. 33.

- ↑ Baker, pp. 28, 31

- ^ Chambers, EK The Elizabethan Stage. 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923; Vol. 3, p. 396.

- ^ Thomas Kyd: The Spanish Tragedy . Philip Edwards, ed. The Revels Plays; Methuen & Co., 1959. (Reprint: Manchester University Press, Manchester 1986 pp. Xxi-xxvii)

- ↑ Chambers, Vol. 3, pp. 396-397.

- ^ Edwards, pp. Xxvii-xxix.

- ↑ Chambers, Vol. 3, p. 395.

- ↑ Edwards, S. lxvii-lxviii.