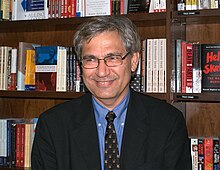

Orhan Pamuk

Orhan Pamuk (born June 7, 1952 in Istanbul , Turkey ) is a Turkish writer . He is considered one of the most internationally known authors in his country and was the first Turkish writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006. His work includes 10 novels (as of 2020), an autobiographical memory book and numerous essays . It has been translated into 35 languages and published in over 100 countries.

In his work, Pamuk mediates between the modern European novel and the storytelling tradition of the Orient. His political engagement, which is essentially based on human rights, also shows him in a mediating position between Turkey and Europe that demands both sides.

Biographical aspects

Childhood and youth

Orhan Pamuk was born in Istanbul in 1952 and has been closely associated with the city throughout his life. His parents belonged to the western-oriented, affluent middle class. Pamuk's grandfather had made his fortune as an engineer and industrialist building railways. His father was also an engineer. Pamuk has an older brother and a younger half-sister. Together with their grandmother, uncles and aunts, the family lived in a five-story house in the Nişantaşı district of Istanbul's Şişli district north of the Bosphorus . The family supported Ataturk's modernization of Turkey and was oriented towards the West. The father in particular had numerous cultural interests:

“I grew up in a house where many novels were read. My father had an extensive library and talked about the great writers like Thomas Mann , Kafka , Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy in the same way that other fathers at home might speak of generals or saints. Even as a child, all these novels and authors were one with the term Europe for me. "

After primary school, Pamuk attended the English-speaking Robert College . He dealt intensively with painting at an early age and had the desire to become an artist as a teenager. Nevertheless, like his grandfather and father, he began to study architecture at the Istanbul Technical University . He dropped out of studies after a few years and decided to give up painting and become a writer. In order to avoid military service, he moved to the University of Istanbul and obtained a university degree as a journalist in 1977 .

Start of career

In 1974 he began work on his first novel, Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları ( Cevdet and his sons ). During this time, Pamuk lived with his mother in a summer house on one of the Prince Islands in the Marmara Sea without earning any income . Together with Mehmet Eroğlu, he won the 1979 novel competition of the Milliyet publishing house . The novel was first published in 1982 under the title Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları . In 1983 he won the Orhan Kemal Literature Prize.

In 1982 Pamuk married Aylin Türegün. In 1991 the daughter Rüya was born. The marriage was divorced in 2002. From 1985 to 1988 Pamuk stayed in the USA with his wife, who did her doctorate at Columbia University in New York . There he is working on his third novel Kara Kitap ( The Black Book ) . With this novel, which was published in 1990, Pamuk also had an international breakthrough.

Except for her three-year stay in the USA , Pamuk always lives in Istanbul. He expresses his bond with the city in numerous works.

“In contrast to before, Istanbul is the center of the world for me today, and not only because I've spent almost my entire life here, but also because I've been walking the streets, the bridges, the people, the dogs for thirty-three years , describe the mosques, the fountains, the strange heroes, the shops, the famous personalities, the sore spots, the days and nights of this city and always identify myself with all of them. The ideas that I have developed develop a life of their own and become more important in my head than the city itself in which I live. "

Literary positions, motifs and themes

Comparison of modernity and tradition or orient and occident

Pamuk's works reflect the identity problem of Turkish society, which has been torn between Orient and Occident since Ottoman times. Overall, it addresses the relationship between these two cultural areas and deals with universal topics such as the relationship between Christianity and Islam or modernity and tradition. The reason for the award of the Peace Prize states that he is following the historical traces of the West in the East and the East in the West like no other poet of our time. He is committed to a concept of culture that is based entirely on knowledge and respect for the other.

Istanbul as a city with a 2000 year history right on the border between the two spheres is the ideal focal point for this topic. Spatially, most of Pamuk's novels are set in Istanbul or in the closer and wider surroundings of the city. In the novels Red is My Name ( Benim Adım Kırmızı , 1998) and The White Fortress ( Beyaz Kale , 1985) he draws on historical material from the time of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. The early novels Cevdet and his sons (Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları, 1982) and The Silent House ( Sessiz ev , 1983) have the development of Turkey at the beginning of the 20th century as a background, while the plot of The Black Book ( Kara Kitap , 1990) and The New Life ( Yeni Hayat , 1994) is set in the present. Regardless of the time of the action, all of the novels address the controversial and conflict-ridden relationship between Islamic, Ottoman and Persian traditions and the demands of the present and modern developments, which mostly have their origins in Western Europe.

Narrative technique

Numerous intertextual references can be found in many of Pamuk's novels . The author uses historical material from the Persian or Ottoman tradition that is not very well known in the West. A frequently recurring motif are the myths taken from the Persian national epic Shāhnāme , some of which are presented in detail in the form of a kind of internal plot by various protagonists of the novel. For example, the Islamist leader Lapis Lazuli in Snow (Kar, 2002) tells the protagonist Ka the story of Rustem (or Rostam) and Suhrab as a parable. My name is in red ( Benim Adım Kırmızı , 1998) references to myths and fairy tales are a central stylistic element. In addition to the aforementioned legend of Rüstem, the unhappy love between Sirin and Hüsrev is a leitmotif of the novel. The function of these intertextual references is complex. In any case, they point to a forgotten or neglected past of Turkey.

Quotations and allusions from the European cultural area can also be found in many of his novels. The young protagonist from the novel The Red-haired Woman tells the well-builder master Mehmut the myth of Oedipus . In the novel Das neue Leben ( Yeni Hayat , 1994) there are references to German Romanticism, in particular to Heinrich von Ofterdingen von Novalis . The title alludes to Dante's youth work Vita nova . Pamuk combines various cultural elements from the western and eastern hemisphere. The central concern is to make both lines of tradition fertile. The discussion revolves around the imitation and copy of the modern, and the discussion and synthesis between East and West.

Due to their multi-layered structure and the numerous intertextual references, many of Pamuk's works are classified as postmodern . The changing narrative perspective emphasizes the subjective feelings of different protagonists. In the novel Red is My Name ( Benim Adım Kırmızı , 1998) eleven different main and secondary characters tell the story from their point of view. The author crosses the boundaries of the real world when he lets a tree or the already murdered painter speak. Other novels (e.g. Schnee , Kar, 2002 or das neue Leben , Yeni Hayat, 1994 ) are written from the perspective of a reporting first-person narrator who often has the author's first name.

Autobiographical Influences

In his publications, the author repeatedly establishes a connection between personal experiences and his literary work. Numerous novels, especially the early ones, have autobiographical influences. The work Istanbul, Memories of a City ( İstanbul - Hatıralar ve Şehir , 2003), in which Pamuk describes his childhood and youth there as well as the development of the city in the 19th and 20th centuries, is clearly autobiographical . The travel reports and old pictures from the 19th century as well as the portrayal of Turkish writers broaden the perspective, but the portrayal remains with a very personal point of view. Ultimately, the work is also about the question of how the first-person narrator became who he is. The work ends with the decision to become a writer.

In the acceptance speech for receiving the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 2005, Pamuk explains how, from his point of view, experiences and ideas relate to one another. He emphasizes the similarities between writer and reader when he says that people in a novel should experience situations that “we know, that concern us, that are similar to our situation. Above all, we want a novel to be about people who are like us, or even better: that it is about ourselves. ”In a sense, the reader and author have the same interest: they want to be able to recognize themselves in the characters. He underlines this observation when he reports that as a 17-year-old he read Buddenbrooks and - without knowing anything about Thomas Mann - was able to identify “easily” with the family history. “The wondrous mechanisms of novel art serve to present our own story to the whole of humanity as the story of another.” Pamuk obviously does not accept the accusation that a novel can have too many autobiographical features. For the writer, the process of writing goes in two directions: "It gives us the opportunity to tell both our life as someone else's, and the life of other people as ours." When the writer turns into a literary Shifted figure into it, he appropriates the "other" and thus expands his own horizon and that of the reader.

“The novelist senses that because of the way the art he practices works, identification with the 'other' will produce fruitful results. He knows that it will set him free to think the other way around than what is commonly expected. The story of the novel can also be written as the story of the possibility of putting yourself in the shoes of others and changing, even liberating yourself through this imagination. "

Literary role models

First of all, the “great” novelists of the 19th and early 20th centuries, with whom Pamuk made the acquaintance of early in his father's library, should be mentioned as literary models. The author repeatedly mentions Fedor M. Dostoevskij or Thomas Mann in speeches . In addition, Lev N. Tolstoy , William Faulkner , Virginia Woolf , Vladimir Nabokov and Marcel Proust are counted among his role models. According to his own statements, the reception of this “western world literature” also gave him the feeling that he was “not in the center” and that, as a Turk, he was excluded.

Turkish writers have also influenced Pamuk. Mention should be made of Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar (1901–1962), whose concept of melancholy or “Hüzün” he takes up and continues. Another role model could be the experimental author Oğuz Atay (1934–1977).

Some later works of Pamuk are associated with authors such as Jorge Luis Borges , Italo Calvino , Paul Auster and Gabriel García Márquez .

Individual works

Novels

Cevdet and his sons

Pamuk's debut Cevdet and his sons (Turkish: Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları), created between 1974 and 78, tells in three parts the decisive developments of the Işıkçı family of merchants and manufacturers against the background of the changing Turkish history in the 20th century, which was shaped by reform movements based on the European model. Century. The novel was first published in Turkey in 1982 and the German translation was published in 2011.

The main plot begins in 1905 with the marriage of the company founder Cevdet to Nigân, the daughter of a respected Paşa family, and ends with their death in 1970. Designed using the example of the title character, his children Osman, Refik, his friends Ömer and Muhittin, as well as Ayşe and grandson Ahmet the author different conceptions, which in the later works deal with varying central themes: the search for the meaning of life, the vacillation between the priorities family, business and self-discovery as well as career and morality, the discussions about tradition and progress, the artistic processing of the Reality and political engagement. Osman and his son Cemil on the one hand and Refik and his son Ahmet on the other hand represent two contrasting lines of development. The broad personal networking and the various locations of Istanbul, Ankara and the rural region around Kemah create a differentiated picture of the change in Turkish upper-class society.

The silent house

Between 1980 and 1983 Pamuk wrote his second novel Das Stille Haus (Sessiz ev) , published in 1983 and published in German in 2009. As in his debut Cevdet and his sons , he paints a differentiated picture of Turkish society in the 20th century in the tension between tradition and reform efforts using the example of a family. Inserted into the seven-day action in Cennethisar near Gebze on the Marmara Sea are the memories of five storytellers from three generations: They reveal the background of the story of the grandfather, the doctor and radical enlightener Selâhattin Darvinoğlu, the one with the traditionally conservative Fatma from the Istanbul upper middle class is married. This enters into a marriage-like relationship with his maid from the poor class of the population. Two sons, who later worked as servants and lot sellers, the dwarfed Recep and the limping İsmail, as well as a grandson, Hasan, came from the non-legalized connection. These descendants now meet in July 1980, at a time of left and right-wing radical controversy and acts of violence two months before the military coup, with the three legal grandchildren (Faruk, lecturer in history, Nilgün, sociology student, and Metin, high school student) tragic end of the summer vacation week.

The white fortress

The novel The White Fortress ( Beyaz Kale , 1985), first published in Turkey in 1985 and in 1990 by Insel Verlag in German translation, tells of the adventures of a young Venetian who falls into the hands of the Turks in a sea battle. As the slave of a hodja who plays a role at the Ottoman court and who looks astonishingly similar to the first-person narrator , he becomes entangled in a master-servant relationship in which the two opponents become increasingly similar. As clearly as the roles between the Venetian, who is oriented towards western science, and the Islamic-conservative Hodscha are initially divided, the contours become blurred over time. In a sophisticated puzzle game, the readers' expectations of the typically Oriental are taken up, questioned and finally reduced to absurdity. The hoped-for clear separation between East and West is increasingly proving to be an illusion.

In literary terms, The White Fortress is reminiscent of Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose . Against the backdrop of an exciting story, the world unfolds Koprulu - grand viziers , mingle " enlightened " and " conservative time with images of history, policies and the ideological power struggles between Sultan, courtyard and mosque" ideas. "Of course, an old handwriting", Umberto Eco puts in front of his text, not without irony. “This manuscript came into my hands in 1982”, Orhan Pamuk adds, citing the year of publication of many Eco translations and perhaps his first reading of the “Rose” as the date of discovery, while Eco's narrator “his” manuscript 1968, in the middle of the one for Eco significant student revolt. Like Eco's “reporter”, Pamuks' narrator initially expresses doubts about the authenticity of the document. He also claims that he did not reproduce the original story exactly, but rather neglected it.

The “White Fortress” is the story of a literary kidnapping. The transfer of the European novel to modern Turkey enriches both sides. If Eco amazes in the “Name of the Rose” with the confusing arrangement of modern and medieval views, Pamuk confronts the western reader with unexpected pages of Ottoman and European history.

The black book

The novel The Black Book (Kara Kitap) was first published in Turkey in 1990 and a German translation by Hanser Verlag in 1995 . It's basically a fairly simple story: The young lawyer Galip is left by his beautiful young wife and cousin Rüya. An exciting search begins across the districts of Istanbul, through mosques and catacombs, through bars and brothels. There is increasing suspicion that Rüya is hiding with Celâl, her half-brother, a successful columnist, Galip's great role model. But Celâl cannot be found. He is obviously involved in all kinds of machinations, maintains connections with the mafia, secret organizations and sects.

Galip is desperately looking for signs, for clues in Celâls' column, for example, which repeatedly refers to the life of the family, contains hidden allusions and encrypted messages. Galip becomes more and more entangled in the art of text interpretation, follows instructions from mystical interpreters of the Koran, searches for clues in Celâl's texts and finds literary models, fates that Galip has processed, gets to know people who are also on the lookout. It is a search for identity in a world in which East and West are hopelessly mixed up and in which no one can "be himself".

Orhan Pamuk's book is a document of the turmoil, the vacillation of people between meaningless traditions, superstitions and Western models from great literature to film stars. But even when searching for the true sources, he always comes across new mixtures. At the bottom of the Bosporus these traces come together, crusaders and sultans, gangsters and hanged men, old coins and everyday objects form the soil on which Istanbul grows. In the old shafts you can find mystical texts, forgotten items of clothing, the bones of murdered people, a cabinet of wax figures that embody the people of Istanbul before the city lost its identity.

As in Llosa's novel Aunt Julia and the Art Writer, Pamuk mixes the narrative with contributions from the journalist, with the stories beginning to push their boundaries. Reality and column refer to each other, the characters from Celâl's stories appear in Galip's reality, become threatening, interpret Celâl's portrayal, and are also on the lookout for the lost author. In the end, the boundaries between identities fall. Galip becomes more and more Celâl, sits in one of Celâl's secret apartments and continues the series of columns.

The new life

“One day I read a book and my whole life changed.” With this sentence Orhan Pamuk begins perhaps the most important literary novel, the title The New Life (Yeni Hayat) alludes to Dante 's work of the same name . The story of the mysterious book refers to German romanticism , to Novalis ' Heinrich von Ofterdingen and his search for the blue flower . It is a story of love and death, of a mysterious journey, of playing with literary and mystical sources from East and West. The work is a classic in the sense that it can be read as a mysterious adventure novel, unaffected by all intellectual history gimmicks, but at the same time a perfect toy for the educated reader who can investigate the allusions, hidden quotations and misleading references.

Red is my name

In his novel, written between 1990 and 1998, with the title "Red is my name" based on the old symbolic color (Chapter 31), the author tells the adventurous life story of Kara and Şeküres, which came about with the illuminating dispute in the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. and is woven into a criminal act that develops from it. In doing so, he shifts the current topic of other works, the tension between Eastern tradition and Western influences, to a historical time with fabulous roots.

Since Kara's advertisement for his twelve-year-old cousin was rejected by her father, he accepted a position as secretary of the finance master in the eastern provinces, experienced the wars against the Persians there and returned to Istanbul after twelve years at the age of 36 in 1591 . Here he is supposed to help his uncle write a book. He accepts the order that Şeküre, meanwhile widow of a soldier, lives with her two sons Şevket and Orhan again in their father's house and he hopes to be able to marry his childhood sweetheart. As envoy of Sultan Murad III. in Venice individual Renaissance - portraits met and should be make an illustrated book in the new "Frankish" style for its rulers. Since the state painting workshop of the master Osman is committed to the traditional style, tolerated by most representatives of Islam , the best illustrators Velican ("Olive"), Hasan Celibi ("Butterfly") and Musavvir Mustafa ("Stork") work at home on this secret project. They receive partial orders with precise instructions that only give them a fragmentary insight. As a result of their work, the artists get into a conflict of conscience between religious belief, according to which they, like the " Franks ", glorify people and also displace centuries-old image design, and interest in new artistic possibilities, which they do not yet master technically and only imitate . From this situation, the ornamenter Fein, fanatical by the preacher Nusret Hodscha from Erzurum, and soon afterwards his uncle, are slain. The murder instrument of the second act is a 300 year old Mongolian inkwell from Tabriz , and the color red it contains is symbolically mixed with the blood of the victim. Its soul roaming the universe finally reaches a wonderful red area. When she asked whether she was not too touched by the images of the unbelievers, she heard a voice: “The West and the East, both are mine” (chap. 37, p. 310).

The Şeküre, who is defenseless without her father and harassed by her brother-in-law Hasan, marries Kara on condition that she clarify the death of her father. He suspects the murderer to be among the painters in the workshop and tries to track him down together with Master Osman through style analyzes by comparing the artists' models in the sultan's treasury with a horse drawing found in the dead Fein's. This is how they achieve their goal and the Persian illustrator Olive has to confess the deeds. In the fight with Kara he injures Kara badly and escapes. But while on the run he is killed by the jealous Hasan, who, curiously, thinks he is a companion of his rival. Şeküre cares for the wounded man and, since he has solved the case and almost had to pay for it with his life, she discovers her love for him. Despite the fulfillment of his childhood dream and the affection of his wife, the 26 years up to his death are accompanied by melancholy, perhaps a reaction to the lack of interest of the sultan's successors in art and the decline of the workshops: one now paints neither in the east nor in the west Style, but no longer at all: “The picture has been given up” (chap. 59, p. 550). The novel ends with the unfulfilled wish of the protagonist, who has grown old, to have an individual portrait of her youth as well as a portrait of bliss - a mother who breastfeeds her children - in the style of the old Herater masters who endured the time .

The author has Şeküres son Orhan write the novel based on the stories of his mother, who in turn collected the personal messages of the other people, mixed with her own ideas and inventions, and thus opens up a broad spectrum of overlapping and, through the reports of the murdered victims , fictional perspectives that transcend the boundaries of reality . This creates a complex polyphonic structure: eleven main and secondary characters alternately present the plot, generally in chronological order. Through the centuries-old fairy tales and legends , z. B. von Rüstem from the "Book of Kings" ( Shāhnāme ) by Firdausi or, above all, the situation used as a leitmotif when the beautiful Şirin fell in love with King Hüsrev through a picture, as well as through the histories of the old master painters and their precious works and that of one Storytellers ( Meddah ) like painted figures (dog, horse, woman, Satan, death, etc.) brought up in a role play, the crime story expands into an imaginative wide painting.

snow

The novel Schnee was published by Carl Hanser Verlag in the original in Turkish in 2002 under the title Kar and in German in 2005 in a translation by Christoph K. Neumann . He describes on z. In a partly satirical way, the conditions and the various actors in a Turkish / Kurdish provincial town, which stands like a kind of microcosm for Turkey as a whole.

At the center of the plot is the poet and journalist Ka, who goes to the provincial town of Kars to report on a series of suicides among young women. They killed themselves because they were forced to take off their headscarves at university. Secretly, he would also like to see his former student friend, Ipek, who has since separated from her husband, the local police chief and candidate for mayor. Ka begins the research by speaking to various local actors and the bereaved. The stay inspires Ka to write new poems after a lengthy creative crisis. He also comes into contact with Ipek again. The tension in the village becomes visible when he and Ipek witness the murder of the university director, where the young women killed themselves because of the headscarf ban. The theatrical performance of an acting troupe that evening, which Ka is also attending, gets completely out of control. During the performance there is a coup, first staged by actors, then by real soldiers who shoot into the auditorium. Due to the heavy snowfall, the place is cut off from the outside world and nobody can leave the city. Ka is increasingly drawn into the events and is supposed to help publish a joint appeal against the coup in a German newspaper, in which an Islamist leader in hiding is also involved. Finally his report breaks off and the first-person narrator has to reconstruct the further course of events.

With the present-day plot, Pamuk addresses some of the current issues in 2002, such as the role of the secular state, surveillance by the police and the ban on headscarves. He is less interested in taking a clear position than in describing the conflict situations and different actors: "Everyone, every important trend, has their say in the novel: the Turks and the Kurds, the nationalists, the secularists, the army, the Believers and the Islamist fundamentalists. The subject is political, but the novel is about something else, perhaps about the meaning of life in this eastern Anatolian corner of the world. "

The Museum of Innocence

In this novel, Pamuk tells a love story that takes place in Istanbul between 1975 and 1985. The wealthy factory owner's son Kemal and the well-educated Sibel plan to marry. One day Kemal happens to meet a family relative, Füsun, a young woman from a lower class. They fall in love but cannot live together. Kemal's love for Füsun grows over time and he begins to collect Füsun's personal items, with which he opens a museum at the end of their sad love story.

The Museum of Innocence is the title of the book and at the same time the name of the museum. Pamuk describes the museum as "a modest collection of everyday life in Istanbul."

This strangeness in me

The novel This Strangeness in Me was first published in 2014 under the title Kafamda Bir Tuhaflık and was published by Carl Hanser Verlag in 2016 in a translation by Gerhard Meier . It is about the life story of a street vendor in Istanbul, based on which the events of the last 50 years in this metropolis are described. In the 1960s, Mevlut falls in love with a woman in Anatolia. He woos her for three years until her brother finally sends him the older sister, while his childhood friend takes the one he actually desires as his wife. Mevlut accepts his fate and marries the woman he doesn't actually love, and the two families live together in Istanbul for many years.

The red-haired woman

The red-haired woman first appeared in German in 2017 in a translation from Turkish by Gerhard Meier. The original edition was published in 2016 under the title Kırmızı Saçlı Kadın by Yapı Kredı Yayınları. The novel describes the memories of the first-person narrator Cem of an event long ago and its effects on his further life. The action takes place in the greater Istanbul area in the 1980s and extends to the present day. The author links the based in the modern Turkey of action with the Greek Oedipus -Sage and the legend of Rostam and Sohrab from the Persian national epic Shahnameh .

Other works

Istanbul - memories of a city

Main article Istanbul - memory of a city

The autobiographical work was first published in 2003 under the original title İstanbul - Hatıralar ve Şehir in Turkey and in 2006 in the German translation by Gerhard Meier by Carl Hanser Verlag .

Divided into 37 chapters, the author describes his memories of his childhood and youth in Istanbul from around the mid-1950s (Pamuk was born in Istanbul in 1952) to around 1972, when he decided to study architecture and painting give up and become a writer. In addition to these autobiographical memories, the author takes into account the impressions of western travelers to the Orient such as the French romantics of the 19th century Gèrard de Nerval and Théophile Gautier as well as Turkish writers and journalists of the early 20th century. With this, Pamuk addresses the far-reaching cultural changes that have shaken Turkey and Istanbul. He describes the deep melancholy (Turkish: hüzün ) of its residents, which everyday culture in Istanbul cannot be imagined without. Orhan Pamuk understands hüzün as "the feeling with which Istanbul and its inhabitants have been infected in the most intense way in the last century". In addition, the work contains numerous photos of Istanbul from the 50s and 60s as well as the cityscapes by Antoine Ignace Melling from the 18th century, to which the author also devotes a separate chapter.

In terms of genre, the work most closely resembles a very long essay , e.g. Sometimes it is also referred to as a novel in secondary literature .

Ben Bir Agacım

Ben Bir Ağacım (in German: Ich bin ein Baum ) was published in August 2013 by Yapı Kredi Yayınları in Turkish and is an anthology with various excerpts from the author's novels. It contains u. a. a chapter from the as yet unpublished novel Kafamda bir tuhaflık'ın (for example: “A bizarre in my head”), in which the protagonist Mevlut Karataş tells from his school days, and a selection of stories from the novels The Black Book , My Name ist red (Kp. 10 Ich bin ein Baum : the story of a tree intended to illustrate a book is told), snow and Istanbul .

This compilation can be seen as an introduction to Pamuk's work, because the selected texts are written in an easily understandable language so that as many (especially younger) people as possible can read and understand them.

Pamuk's photo book

Pamuk's first photo book, Balkon , was published in Germany in autumn 2018 . The photos were all taken from Pamuk's balcony over the course of five winter months and show the ship traffic on the Bosporus.

Political positions

Political engagement in Turkey

Pamuk often takes a stand on controversial social and political issues in Turkey and Europe. He is therefore a sought-after interview partner and essayist. Despite this commitment, Pamuk sees himself primarily as a fiction writer who does not pursue any specific political goals. With his commitment he is committed to a humanism that is also expressed in his works.

“What literature today should primarily tell and research is mankind's fundamental problem, namely feelings of inferiority, the fear of being excluded and insignificant, injured national pride, sensitivities, various types of resentment and fundamental suspicion, never-ending humiliation fantasies and accompanying nationalistic boasting and arrogance. "

Pamuk has repeatedly campaigned for freedom of expression in Turkey without taking into account possible threats from Islamists or nationalists. He condemned the fatwa against Salman Rushdie as the first author in the Muslim world. He stood up for the Turkish-Kurdish writer Yaşar Kemal when he was indicted in Turkey in 1995. He also criticized the Turkish government's Kurdish policy and therefore refused to receive the Turkish Culture Prize.

With the novel Schnee (Kar) , published in 2002, the author describes current political and social actors in Turkey in a distant and sometimes ironic way and also takes up the polarizing problem of the headscarf ban without taking a clear position on it. The author was then attacked mainly by nationalist circles. However, the novel met with little understanding, even in enlightened circles, so that Pamuk, according to his own statement, is “nobody” in Turkey: “I express myself publicly critical of Turkish nationalism, the many nationalists here cannot bear that. And also the fact that I'm flying around the world [...] and not waving the Turkish flag like an Olympic gold medalist, but that I'm critical, that drives many Turks crazy. "

In 2007 Pamuk withdrew from the public for a few years. The publications following the novel Schnee (Kar) did not address current political issues. The protests around the Taksim Gezi Park in Istanbul in 2013 but he again supported. He also criticized increasing restrictions on freedom of expression in Turkey with publicity. After the failed coup in 2016 , he protested the arbitrary arrests and, for example, signed a letter of protest from the PEN with other international authors against the imprisonment of numerous journalists and intellectuals.

Hostility from Turkish nationalists

At the end of the interview quoted above, which appeared in the Zürcher Tages-Anzeiger magazine on February 5, 2005, Pamuk mentioned that there had been mass killing of Armenians in Turkey , avoiding the term “ genocide ”: “ Thirty thousand Kurds were killed here. And a million Armenians. And almost nobody dares to mention it. So i do it. And they hate me for that. "

Turkish nationalists then launched a campaign against him. He was verbally abused and received death threats. In the district of Sütçüler in the province of Isparta , a district administrator ordered that his books should be removed from public libraries. The measure was reversed by a higher authority.

Pamuk was charged by an Istanbul district attorney for violating Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code , the so-called “ public degradation of Turkishness ”, which resulted in up to five years imprisonment in Turkey at the time. The trial began on December 16, 2005, but was postponed to February 2006 that same morning due to open procedural issues. Amnesty International and numerous writers' organizations as well as the President of the German Bundestag Norbert Lammert protested against the process . The proceedings were initially discontinued on January 22, 2006. After the trial was reopened, Pamuk was sentenced to pay 6,000 Turkish liras in damages to six plaintiffs who were offended by his statements about the Armenian genocide.

Even after the trial, the author was confronted with death threats, so that in January 2007 he canceled a planned trip to Germany and left Turkey. In January 2008 it became known that the nationalist underground organization Ergenekon assassinations u. a. also supposed to have planned on Orhan Pamuk. The arrested members included a lawyer who, along with others, had initiated the criminal case against Pamuk.

Criticism of the west

In many contributions and interviews, Pamuk criticized the West's attitude towards Turkey and the Islamic world. A well-received article, which first appeared in the Süddeutsche Zeitung in response to the attacks on September 11, 2001 , explains the partially positive reaction of the population in the Arab world. "Unfortunately, the West has little idea of this feeling of humiliation that a large majority of the world population goes through and has to overcome without losing their minds or getting involved with terrorists, radical nationalists or fundamentalists." A solution to the conflict by military means, In the same essay, he clearly criticizes how the USA is striving for it:

“Today the problem of the“ West ”is less of finding out which terrorist in which tent, which cave, which alley, which distant city is preparing a new attack and then dropping bombs. The problem of the West is rather to understand the mental state of the poor, humiliated and always "wrong" majority who do not live in the western world. "

In the speech about the receipt of the peace prize of the German book trade , Pamuk accuses the West of having an arrogant attitude towards the countries of the Middle East:

“Often the East-West problem is nothing else than the fact that the poor countries in the East do not want to bow to all the demands of the West and the USA. This point of view reveals that the culture, life, and politics of those climes where I come from are seen as just a nuisance, and writers like me are even expected to find a solution to that problem. It must be said that the condescending style in which such things are phrased is part of the problem itself. "

Pamuk has campaigned vehemently in many newspaper articles and speeches for Turkey's accession to the European Union and has tried to allay the concerns. If Europe takes the ideals of the French Revolution of freedom, equality and fraternity seriously, it could also accept a predominantly Muslim country like Turkey into the EU. The strength of Europe lies in a development that was brought about not by religious, but by secular forces. Elsewhere he emphasizes that the “heart of the European Union” is the idea of peace and that Turkey's wish to participate in this peaceful cooperation between states cannot be turned down. It is also about the choice between “book-burning nationalism” and peace. In later interviews he criticized the hesitant attitude of the Europeans and justified the turning away of many Turks from Europe. He condemned the increasing isolation of Europe during the refugee crisis in 2015 : "Dealing with refugees damages not only the social context in Europe, but also the spirit of Europe."

Awards

He received the 'Prix de la découverte européenne' in 1991 for the French translation of his novel Sessiz Ev (German: The silent house ) and the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 1990 for the novel Beyaz Kale (German: The White Castle ) . The novel Benim Adım Kırmızı (dt .: red is my name ) won the 2003 IMPAC Dublin Award .

On October 12, 2006, the Swedish Academy announced its decision to award the 2006 Nobel Prize for Literature to Pamuk, “who, in search of the melancholy soul of his hometown, had found new symbols for conflict and interwoven cultures”.

- 1979: Winner of the Milliyet publishing house's novel competition with the novel Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları (TR)

- 1983: Orhan Kemal Literature Prize for Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları (TR)

- 1984: Madarali Novel Prize for Sessiz Ev (TR)

- 1990: Independent Foreign Fiction Prize

- 1991: Prix de la découverte européenne

- 2003: International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award for Red is my name

- 2005: Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

- 2005: Ricarda Huch Prize

- 2005: Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 2006: Nobel Prize in Literature

- 2007: Honorary doctorates from the Free University of Berlin as an “exceptional phenomenon in world literature”, the Catholic University of Brussels and the Bosporus University in Istanbul

- 2008: Admission to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 2012: Sonning Prize

- 2015: Erdal-Öz Literature Prize

- 2016: Nomination for the Man Booker International Prize

- 2017: Shortlist of the International DUBLIN Literary Award with A Strangeness in My Mind

- 2018: Member of the American Philosophical Society

Quotes

- My job is not to explain the Turks to the Europeans and the Europeans to the Turks, but to write good books.

- You know, there are people who love their country by torturing them. I love my country by criticizing my state.

Works

- Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları (1982), ISBN 975-470-455-4 German Cevdet and his sons (2011), ISBN 978-3-446-23639-4

- Sessiz Ev (1983), ISBN 975-470-444-9 German The silent house (2009), ISBN 978-3-446-23400-0

- Beyaz Kale (1985), ISBN 975-470-454-6 ; German The White Fortress (1990), ISBN 3-518-38999-8

- Kara Kitap (1990), ISBN 975-470-453-8 ; German The Black Book (1995), ISBN 3-596-12992-3

- Gizli Yüz (1992) feature film Turkey 1991, director: Ömer Kavur, script: Orhan Pamuk, Ömer Kavur

- Yeni Hayat (1994), ISBN 975-470-445-7 ; German Das neue Leben (1998), ISBN 3-596-14561-9

- Benim Adım Kırmızı (1998), ISBN 975-470-711-1 ; German red is my name (2001), ISBN 3-596-15660-2

- Öteki Renkler (1999), ISBN 975-470-765-0

- Kar (2002), ISBN 975-470-961-0 ; German snow (2005), ISBN 3-446-20574-8

- İstanbul - Hatıralar ve Şehir (2003); German Istanbul - Memory of a City (2006), ISBN 978-3-446-20826-1

- Babamın Bavulu (2007) ISBN 978-975-05-0482-2 ; German My Father's Suitcase (2010), ISBN 978-3-446-23492-5

- Mandarin (2008) feature film Turkey / Hungary, director: Balázs Simonyi, screenplay: Orhan Pamuk / Balázs Simonyi

- Masumiyet Müzesi (2008), ISBN 978-975-05-0609-3 ; German The Museum of Innocence (2008), ISBN 3-446-23061-0

- The View Out of My Window: Reflections (2008), ISBN 978-3-596-17763-9

- Manzaradan Parçalar: Hayat, Sokaklar, Edebiyat (2010), ISBN 978-975-05-0798-4

- Saf ve Düşünceli Romancı (2011), ISBN 978-975-05-0940-7 ; German The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist (2012), ISBN 978-344-62-3884-8

- Ben Bir Ağacım (2013), ISBN 978-975-08-2610-8

- Kafamda Bir Tuhaflık (2014), ISBN 978-975-08-3088-4 , German. This strangeness in me. Hanser, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-44625-058-1 .

- Innocence of Memories (2015) feature film Great Britain, director: Grant Gee, script: Orhan Pamuk, Grant Gee

- Kırmızı Saçlı Kadın (2016), ISBN 978-975-08-3560-5 , German The red-haired woman . From the Turkish by Gerhard Meier. Hanser, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-446-25648-4 .

Secondary literature

- To the work

- Ian Almond: Islam, Melancholy, and Sad, Concrete Minarets: The Futility of Narratives in Orhan Pamuk's “The Black Book”. In: New Literary History, 34. 2003. H. 1, pp. 75-90.

- Feride Çiçekoğlu: A Pedagogy of Two Ways of Seeing: A Confrontation of “World and Image” in “My Name is Red”. In: The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 37. 2003. H. 3, pp. 1-20.

- Feride Çiçekoğlu: Difference, Visual Narration and “Point of View” in “My Name is Red”. In: The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 37. 2003. H. 4, pp. 124-137.

- Catharina Dufft: Orhan Pamuks Istanbul (= Mîzân , Volume 14). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-447-05629-8 (also dissertation at the Free University of Berlin , 2007).

- Catharina Dufft: The Autobiographical Space in Orhan Pamuk's Works. In: Olcay Akyıldız, Halim Kara, Börte Sagaster (eds.): Autobiographical Themes in Turkish Literature: Theoretical and Comparative Perspectives (= Istanbul Texts and Studies 6). Ergon, Würzburg 2007.

- Catharina Dufft: Entry Pamuk, Orhan in Munzinger Online / KLfG - critical lexicon for contemporary foreign language literature.

- Priska Furrer: Longing for meaning. Literary Semantization of History in Contemporary Turkish Novel . Reichert, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 978-3-89500-370-7 (also habilitation thesis at the University of Bern , 2002).

- Katrin Gebhardt-Fuchs: The I - a second self - intercultural self-construction and ethnographic representation in Orhan Pamuk's novel “The White Fortress” . KIT Library, Karlsruhe 2014, DNB 1059157519 ( Dissertation Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), August 13, 2014, supervisor: Bernd Thum , online PDF, free of charge, 196 pages, 1.1 MB).

- Yasemin Karakaşoğlu: Five voices in the silent house. History, time and identity in contemporary Turkish novels using the example of “Sessiz Ev” by Orhan Pamuk (= Mîzân , Volume 5). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-447-03379-7 .

- Oliver Kohns: World literature and the misunderstanding of the novel - Orhan Pamuk's “Masumiyet Müzesi” (“Museum of Innocence”). In: Thomas Hunkeler, Sophie Jaussi, Joëlle Légeret (eds.): Productive errors, constructive misunderstandings (= Colloquium Helveticum, 46). Aisthesis Verlag, Bielefeld 2017 (as pdf download , as of March 29, 2020).

- Interview / conversation

- Gero von Boehm : Orhan Pamuk, July 22, 2008 . Interview in: Encounters. Images of man from three decades . Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-89910-443-1 , pp. 602-615.

Movies

- Human landscapes - “Six portraits of Turkish writers”. Portrait of Orhan Pamuk, WDR December 2010, production: Lighthouse Film, (in cooperation with the Kulturforum Turkey / Germany) 0, director: Osman Okkan, camera: Tom Kaiser, Antonio Uscategui, editor: Daniela Roos, Nils Schomers. Advice: Galip Iyitanir

- Orhan Pamuk - The Discovery of Solitude. Documentation, 45 min., Script and direction: Florian Leidenberger, first broadcast: Bayerischer Rundfunk , July 17th, 2005 ( summary by arte )

- Test case for freedom of expression - The writer Orhan Pamuk in court in Turkey. Report, 8 min., Production: NDR , October 2, 2005 ( summary from NDR ( memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ))

Web links

- Literature by and about Orhan Pamuk in the catalog of the German National Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 2006 award to Orhan Pamuk

- Orhan Pamuk in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Orhan Pamuk Bookweb (English)

- www.orhan-pamuk.de Author's website about Orhan Pamuk from Hanser Verlag

- Current portrait of Orhan Pamuk , December 2010

- Interview with Orhan Pamuk: The Museum of Innocence - a declaration of love to Istanbul

Posts by Pamuk

- Orhan Pamuk: “Before my trial” , FAZ , December 15, 2005 (Text that Pamuk wrote before his trial. In it he sees his 'drama' in the context of a conflict that is taking place in economically emerging countries like India and China between a politically -economic program on the one hand and accompanying cultural expectations on the other hand. The new economic elites adopt Western idiom and behavior and expose themselves to the accusation of neglecting their own traditions. The counter-reaction then comes to a passionate and virulent nationalism.)

- On trial. ( Memento of April 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) English translation in New Yorker , December 12, 2005

- Orhan Pamuk: "My Father's Suitcase" Nobel Prize Speech, December 7th, 200

Interviews

- “The invention of Turkey. The writer Orhan Pamuk on Ottoman traditions, westernization and the future of Europe ” , Der Tagesspiegel , August 12, 2005

- “Snails in the Muslim Quarter” , Jungle World from November 2, 2005, interview by Deniz Yücel

- "I am happy when I write" , Nobel laureate in literature Orhan Pamuk in an interview with Rubina Möhring, Kulturzeit, August 13, 2008, video 5:36 min.

- The quince grater and the universe of love , October 25, 2008, Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Reviews

- From heaven through the world to hell. The secret logic of color. In his masterful novel “Red is my name”, Orhan Pamuk asks which side Allah is on. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 10, 2001, p. V.

- “The religious is political” ( Memento from March 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), Netzeitung , October 12, 2006.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk: Istanbul . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-596-17767-7 , pp. 17th ff .

- ↑ On Dostoyevsky's influence see: Orhan Pamuk: First Dostoyevsky teaches how to enjoy humiliation . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . January 2, 2001, p. 44 .

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk: A School of Understanding. Acceptance speech for the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade 2005. 2005 börsenblatt FRIEDENSPREIS. ( PDF, 265 KB ( Memento of March 10, 2014 in the Internet Archive ))

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Literature 2006. Retrieved February 23, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ NYTimes. Retrieved February 23, 2020 .

- ↑ https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2006/pamuk/25295-orhan-pamuk-nobelvorlesung/

- ↑ Jury of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade: Rationale of the jury. In: Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. 2005, accessed March 14, 2020 .

- ^ Sefik Huseyin: Orhan Pamuk's “Turkish Modern”: Intertextuality as Resistance to the East-West Dichotomy.

- ^ A b c Orhan Pamuk: Acceptance speech for the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. Retrieved February 27, 2020 (de-tr).

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Jury of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade: Rationale of the jury. In: Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. 2005, accessed March 14, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Entry "Pamuk, Orhan" in Munzinger Online / KLfG - Critical Lexicon for Contemporary Foreign Language Literature, URL: http://www.munzinger.de/document/18000000593 (retrieved from Munich City Library on February 24, 2020)

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk: Nobel Verolesung. My father's suitcase. 2006 ( nobelprize.org ).

- ^ Johanna Chovanec: Istanbul. A melancholy city in the context of the Ottoman myth. In: Marijan Bobinac, Johanna Chovanec, Wolfgang Müller-Funk, Jelena Spreicer (eds.): Post-imperial narratives in Central Europe. Narr Francke Attempto, Tübingen 2018, p. 49-68 ( researchgate.net ).

- ↑ Hubert Spiegel: Interview with Orhan Pamuk. “I will think very carefully about my words.” In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), July 6, 2005, No. 154, p. 35 ( online , accessed April 14, 2020).

- ↑ Susanne Landwehr: Orhan Pamuk: 4213 cigarettes of the beloved woman . In: The time . No. 19/2012 ( online ).

- ↑ Patrick Batarilo: Hüzün: The Turkish Melancholy. SWR2, January 7, 2010, archived from the original on June 28, 2013; accessed on May 26, 2020.

- ^ Gençler için Orhan Pamuk. Vatan Gazetesi, August 15, 2013, accessed August 16, 2013 (Turkish).

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk Gezi Parkı'yla ilgili yazı yazdı. Hürriyet Gazetesi, June 6, 2013, accessed August 16, 2013. (Turkish)

- ↑ A rare guest in Germany: Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk in Göttingen , Deutschlandfunk Kultur .mp3 on October 14, 2018, accessed October 14, 2018.

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk: My father's suitcase. Speech on receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature. Stockholm 2006 ( online , accessed April 4, 2020).

- ^ Lewis Gropp: Orhan Pamuk: Best-selling author and avant-garde writer. In: qantara.de. Goethe Institute u. a., 2003, accessed March 30, 2020 .

- ↑ Peer Teuwsen: The most hated Turk. Interview with Orhan Pamuk. Tagesanzeiger, Zurich February 5, 2005 ( online , accessed April 3, 2020).

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk: Istanbul's last chestnut. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, June 6, 2013 ( online , accessed April 4, 2020).

- ↑ Stefan Dege: Protest against the arrest of the Atlan brothers in Turkey. Orhan Pamuk sees the danger of a "terror regime". Report on Deutsche Welle Kultur, September 14, 2016 ( online , accessed April 4, 2020).

- ↑ Peer Teuwsen: The most hated Turk. Interview with Orhan Pamuk. Tagesanzeiger, Zurich, February 5, 2005. The paragraph reads: Magazine: “But I'm not quite finished yet. How can the Turks reconcile again? ” Pamuk: “ It's only about one thing: Today a Turk earns an average of four thousand euros a year, a European nine times more. This humiliation must be remedied, then the consequences such as nationalism and fanaticism will resolve themselves. That is why we need accession. You see, our past changes with our present. What happens now changes yesterday. Your own relationship to the country can be compared with that to your own family. You have to be able to live with it. Both say: Atrocities have happened, but nobody else should know. " Magazine: " And you talk about it anyway. Do you really want to get in trouble? ” Pamuk: “ Yes, everyone should do that. Thirty thousand Kurds were killed here. And a million Armenians. And almost nobody dares to mention it. So i do it. And they hate me for that. ” ( Online , accessed April 3, 2020).

- ↑ a b Orhan Pamuk: Desolate consolations. Süddeutsche Zeitung, September 28, 2001, p. 15. Reprint: “The Wrath of the Damned” in: Orhan Pamuk: The view from my window: Reflections. Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2006, pp. 52–57.

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk: Beacon of Civilization. In: Süddeutscher Zeitung, October 28, 2012 ( online , accessed April 4, 2020).

- ↑ Thomas Steinfels: Interview with Orhan Pamuk. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, May 26, 2017 ( online , accessed April 4, 2020).

- ↑ http://www.friedenspreis-des-deutschen-buchhandels.de/sixcms/media.php/1290/2005%20Friedenspreis%20Reden.pdf

- ↑ Honorary Members: Orhan Pamuk. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Stefan Grund: Orhan Pamuk does not want to be a bridge builder , Die Welt , May 3, 2007.

- ^ Niels Kadritzke: The Turks before Brussels ( Memento from May 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) , Le Monde diplomatique .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pamuk, Orhan |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Turkish journalist and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 7, 1952 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Istanbul , Turkey |