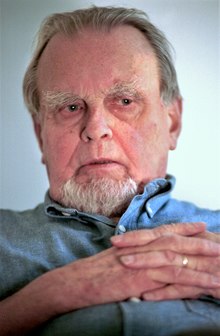

Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz [ ˈt ͡ʂɛswaf ˈmiwɔʂ ] ( ) (born June 30, 1911 in Šeteniai (Polish: Szetejnie ), Kowno Governorate , Russian Empire (now Lithuania ); † August 14, 2004 in Krakow , Poland ) was a Polish poet . In 1980 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature .

Life

The family belonged to the long-established Polish landed gentry . Czesław Miłosz completed his secondary and university studies in Vilnius , which became the capital of a voivodeship in 1922 after the occupation by Poland in 1920 . He broke off studying literature because, according to him, so many women were studying at this faculty that it was called the "marriage department". Reluctantly, he went to law school instead.

His first poems were published in 1930 in the student newspaper Alma Mater Vilnensis . Between 1931 and 1934 he was a leading member of the Żagary (dt. Reisig), a group of writers who were critical of Polish nationalism. He met in Café Rudnicki , a meeting place for Polish artists, and published an avant-garde sheet of the same name, in which the art direction of catastrophism was propagated. In 1933 he published his first volume of poems Poemat o czasie zastygłym (Poem about a frozen time). He graduated the following year, received the first of many literary prizes and a scholarship that allowed him to study in Paris for a year.

During the German occupation in World War II , he worked underground and was able to save the lives of several Jewish fellow citizens, for which he was awarded the title Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1989 .

Between 1945 and 1949 he held various posts in diplomatic missions of the People's Republic of Poland in New York City and Washington, DC , and in 1950 he was transferred to Paris . During a holiday in Warsaw in December, his passport was withdrawn, which he got back at the end of January 1951 only thanks to the intercession of influential personalities. On February 1, 1951, Miłosz “jumped” and was granted political asylum in France. 1953 appeared simultaneously in New York and Paris The Captive Mind (seduced thinking) in English language. Based on four case studies (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta), the book analyzes the enormous attraction that totalitarian systems exert on the writing profession. “The great longing of the free-floating intellectual is to belong to the crowd. This need is so impetuous that many who once looked for inspiration in fascist Germany or Italy have now converted to the New Faith ”. According to Miłosz, the writers' urge to stall makes it so easy for all peddlers to sell their Murti-Bing pills to them (he borrows the picture from Witkiewicz ). Most of all, however, Miłosz angered the Intelligentsia , who set the tone in Paris, with their consistent refusal to enter into a dialogue with dialectical materialism, like other people who have written off. Instead, he focused on describing and analyzing the effects of this method. He briefly dismissed the method itself with the ancient story of the snake, which is undoubtedly a dialectical animal: “'Dad, does the snake have a tail?' asked little Hans. 'Nothing but a tail', answered the father “. - Some critics tried to interpret the book as a kind of roman a clef and criticism of people, and tried to uncover which famous people Miłosz might have meant, e.g. B. Jerzy Putrament (as Gamma, “the slave of history”), Tadeusz Borowski (as Beta), Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński (as Delta) and his former good friend Jerzy Andrzejewski (as Alpha).

In 1960 Miłosz worked as a visiting professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California at Berkeley, where he became a full professor in 1961. He received American citizenship in 1970.

In 1978 he was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature . He gave up teaching and was recognized by his university with the highest recognition, The Berkeley Citation . In 1980 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature , after which the censorship of his books was lifted in Poland that same year. In June 1981, after 30 years of exile, Miłosz returned to Poland, but soon returned to Berkeley. In December, his books were banned again (see also Martial Law in Poland 1981–1983 ). After the fall of the Wall in 1989, Miłosz commuted back and forth between Krakow and Berkeley until he finally settled in Krakow in 2000. In the same year, the poet Pope John Paul II sent an ode on his 80th birthday on May 18th. In the last years of his life, Miłosz explained his ideas in a series of documentaries. Czesław Miłosz died on August 14, 2004 in Kraków.

Even during his exile , Miłosz wrote his works almost exclusively in Polish. Most of his poetic work is available in English translations in editions of HarperCollins and Tate / Penguin. He translated the later poems into English himself in collaboration with Robert Hass.

The poet in the judgment of important colleagues

Joseph Brodsky calls him one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest poets of our time.

For Seamus Heaney , he is one of the few people who know more about reality and can endure it better than anyone else.

Andrew Motion is convinced that the turnaround that Ted Hughes initiated with Crow cannot be explained without Milosz's influence.

Tony Judt considered him the greatest Polish poet of the 20th century.

Honors

- Honorary citizen of Sopot

- Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences , 1981

- Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters , 1982

- Name giver for Miłosz Point in Antarctica, since 1983

- Namesake for the Czesław Point in Antarctica, since 1984

- Honored as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem , 1989

- Honorary Citizen of Krakow, 1993

- Honorary Citizen of Vilnius , 2001

Works in Polish

- 1930: Kompozycja ( composition )

- 1930: Podróż ( travel )

- 1933: Poemat o czasie zastygłym

- 1936: Trzy zimy ( Three winters )

- 193 ?: Obrachunki

- 1940: Wiersze ( poems )

- 1942: Pieśń niepodległa

- 1945: Ocalenie

- 1947: Treatise moralny

- 1953: Zniewolony umysł ( Seduced Thinking )

- 1953: Zdobycie władzy ( The Face of Time )

- 1953: Światło dzienne ( daylight )

- 1955: Dolina Issy ( The Issa Valley ) - based on the author's childhood experiences in the Nevėžis Valley

- 1957: treatise poetycki

- 1958: Rodzinna Europa ( western and eastern area )

- 1958: Kontynenty

- 1961: Człowiek wśród skorpionów ( Man Among Scorpions )

- 1961: Król Popiel i inne wiersze ( King Popiel and other poems )

- 1965: Gucio zaczarowany

- 1969: Widzenia nad zatoką San Francisco

- 1969: Miasto bez imienia ( city without a name )

- 1972: Prywatne obowiązki ( private obligations )

- 1974: Gdzie słońce wschodzi i kędy zapada ( Where the sun rises and where it sinks )

- 1977: Ziemia Ulro

- 1979: Ogród nauk

- 1982: Hymn o pearl

- 1984: Nieobjęta ziemia

- 1987: Kroniki ( Chronicles )

- 1985: Zaczynając od moich ulic

- 1989: Metafizyczna pauza

- 1991: Dalsze okolice ( Far Areas )

- 1991: Poszukiwanie ojczyzny ( search for home )

- 1991: Rok myśliwego ( Year of the Hunter )

- 1992: Szukanie ojczyzny

- 1994: Na brzegu rzeki ( On the Riverside )

- 1996: Legendy nowoczesności

- 1997: Życie na wyspach ( Life on the Islands )

- 1997: Piesek przydrożny (little dog by the wayside)

- 1997: Abecadło Miłosza ( Miłosz alphabet )

- 1998: Inne abecadło ( Different alphabet )

- 1999: Wyprawa w dwudziestolecie

- 2000: To

- 2003: Orfeusz i Eurydyka

Works in German translation

- Seduced thinking , Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne, Berlin 1953, OCLC 600704050

- The face of time . Europa-Verlag, Cologne, Berlin 1953, OCLC 7335938

- The valley of the Issa . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne, Berlin 1957, OCLC 720107898

- West and East Terrain . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne, Berlin 1961, OCLC 601469659

- Song of the end of the world. Poems . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne, Berlin 1966, OCLC 468842693

- The land of Ulro . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1977, ISBN 3-462-01501-X

- Characters in the dark. Poetry and poetics . Suhrkamp, 1979, ISBN 3-518-10995-2

- History of Polish Literature . Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1981, ISBN 3-8046-8583-8

- Poems 1933–1981 . Suhrkamp, 1982, ISBN 3-518-03648-3

- The testimony of poetry . Carl Hanser, 1984, ISBN 3-446-13949-4

- Poems . Suhrkamp, 1992, ISBN 3-518-22090-X

- Streets of Vilnius . Carl Hanser, 1997, ISBN 3-446-18945-9

- Puppy by the wayside . Carl Hanser, 2000, ISBN 3-446-19914-4 .

- My ABC . Hanser Belletristik, 2002, ISBN 3-446-20133-5

- DAS and other poems . Carl Hanser, 2004, ISBN 3-446-20472-5

- Visions on the Bay of San Francisco: American Essays . Suhrkamp, 2008, ISBN 3-518-41993-5

- Poems . Carl Hanser, 2013, ISBN 3-446-24181-7

literature

- Ralf Georg Czapla : Warsaw, Easter 1943. Czesław Miłosz ' Shoa poem "Campo di Fiori" . In: Journal for the history of ideas , volume V / 2, summer 2011, pp. 39–46.

- Christian Heidrich : Strategies against mortality. Czeslaw Milosz seeks grace in gravity . In: Akzente , Issue 3, June 2007, 230–248.

- Ulrike Jekutsch (ed.): Questions of faith. Religion and Church in 20th Century Polish Literature . 1st edition. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-447-06454-5 (in particular pp. 25-67.).

- Andreas Lawaty , Marek Zybura (eds.): Czesław Miłosz in the century of extremes. Ars poetica - space projections - abysses - ars translationis (= Studia Brandtiana. Volume 8). fiber, Osnabrück 2013, ISBN 978-3-938400-85-2 .

- Rafał Pokrywka: Three Autobiographical Dimensions of Czesław Miłosz's Essay Writing . In: Studia Germanica Gedanensia, Vol. 32/2015, pp. 113-121.

- Natacha Royon: Return in the Word. Eastern places of remembrance in works by Czeslaw Milosz et al . Hamburg 2008.

- Andrzej Wierciński : The poet in his being a poet. Attempt at a philosophical-theological interpretation of being a poet using the example of Czeslaw Milosz . Frankfurt / M. 1997.

- Czeslaw Miłosz , In: Internationales Biographisches Archiv 48/2004 of November 27, 2004, in the Munzinger archive ( beginning of article freely available)

Web links

- Literature by and about Czesław Miłosz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Czesław Miłosz in the German Digital Library

- Czeslaw Milosz in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1980 award to Czesław Miłosz

- milosz.pl: Official website (Polish)

- culture.pl: biography (English)

- poets.org: Biography in American Academy of Poets (English)

- Grace Yoon , deutschlandfunk.de: What was big turned out to be small . Deutschlandfunk , Das Feature , January 2, 2015

References and comments

- ^ Czesław Miłosz, Polish-American author - Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ↑ Czeslaw Milosz: Seduced Thinking. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1959, p. 20

- ↑ Czeslaw Milosz: Seduced Thinking. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1959, p. 61

- ↑ Gaither Stewart: Czesław Miłosz. The unfashionable poet. Retrieved February 25, 2020 .

- ↑ Eastern Europe. German publishing company. 2004, Volume 54, Issues 7–8, p. 9

- ↑ Andreas Dorschel : It is a pleasure to confess , in: Süddeutsche Zeitung No. 192 (August 20, 2004), p. 14.

- ^ Czesław Miłosz: New and Collected Poems (1931-2001). HarperCollins, New York 2001

- ^ Nicholas Roe: Czesław Miłosz A Century's Witness. In The Guardian Profile, Nov. 10, 2001

- ↑ Tony Judt: Captive Minds. In New York Review of Books , September 30, 2010, pages 8-10, here: 8

- ↑ Members: Czesław Miłosz. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed April 15, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Miłosz, Czesław |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Polish-American poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 30, 1911 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Šeteniai , Lithuania |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 14, 2004 |

| Place of death | Krakow , Poland |