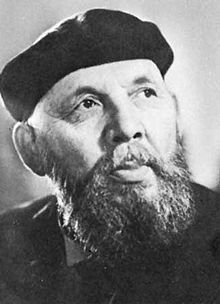

Frans Eemil Sillanpää

Frans Eemil Sillanpää [ ˈfrɑns ˈɛːmil ˈsilːɑnpæː ] (born September 16, 1888 in Kierikkala, Hämeenkyrö municipality ; † June 3, 1964 in Helsinki ) was a Finnish writer . In 1939 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature .

Life

youth

Sillanpää's parents both came from landowning families who, however, had got into economic hardship. The father's real name was Frans Koskinen, but according to Finnish custom he was called Sillanpää (German: "bridgehead") after his hut. The day laborer earned a little extra money through a tiny shop in his hut. Frans Eemil Sillanpää experienced the poverty here, which later became the dominant theme of his novels The Pious Misery and Silja, the Maid .

Two siblings had died early. At that time there was no compulsory education in the Grand Duchy of Finland - at that time part of the Russian Empire . However, the parents did everything possible to give Frans Eemil an education. They first sent him to a primary school in Hankijärvi, then in 1896 to the Tampere municipal high school . Since his parents could no longer bear the costs, the director of the grammar school got him a private tutor position with a wealthy industrialist.

After graduating from high school, Sillanpää moved to Helsinki in 1908, where he enrolled at the Imperial Alexander University to study natural sciences. However, he did not take an exam in a total of five years of study. However, one consequence of his studies was that he saw himself as a materialist . He became a member of a group of artists - the most famous representatives of which were the painter Pekka Halonen and the composer Jean Sibelius - that had come together in Tuusula .

Sillanpää suffered from anxiety while studying . In 1913 he returned to his parents' house, who had moved to Heinijärvi . Their humble home is known in Finnish literature as Töllinmäki ("The Hut on the Hill"). Here he met the 17-year-old daughter of a tenant, Sigrid Maria Salomäki, whom he married two years later.

The writer

In 1914 the newspaper Uusi Suometar published several literary sketches and short stories under the pseudonym “E. Syväri ”. The texts of the unknown author caused a sensation and the Werner Söderström publishing house from Porvoo got in touch. In the autumn of 1916, the first novel, the sun of life , was published here , and it was a great success. Sillanpää lived through the Finnish Civil War in Hämeenkyrö without taking part in the fighting. However, his sympathy was clearly on the left. He processed the events in the novel Das pious misery (also under the title: "Dying and Resurrecting"), which was published in 1919.

The two first works of Sillanpää had aroused great expectations, and Sillanpää has since been under pressure to write the great Finnish novel. The novellas and stories that have appeared since then disappointed in this respect. Sillanpää had taken over financially in Töllinmäki by building a house and founding a family that had now grown to six children. His publisher tried to help him by offering him the editor of Panu magazine in 1926 , but the family had to move to Porvoo to do so.

The debt increased further, and in 1929 Sillanpää turned to the competition, the Otava publishing house, to which he offered all of his future work. The publisher Alvar Renqvist agreed and also became the manager of Sillanpää's financial affairs. As a result, Sillanpää moved to Helsinki in 1930. This improved his working conditions so that the three great novels Silja, the maid , one man's way and people in the summer night could be written. In the mid-1930s, Sillanpää was considered the best writer in Finland. In 1936 the Viidestoista collection of novels was published .

Nobel Prize in literature

The Nobel Prize to Frans Eemil Sillanpää was the first and so far the only one to be awarded to a Finn. The writer had been proposed every year since 1930. One problem was that no member of the Swedish Academy of Finland was powerful, so it only after the on Swedish could judge this translations. Domestically, the Finnish efforts were an obstacle to abolishing Swedish as the second official language in Finland. For a while there was discussion of dividing the award between Sillanpää and the Finland- Swede Bertel Gripenberg , which would also have awarded a representative of “white” Finland alongside “red” Sillanpää (cf. “ Finnish Civil War ”). In the end, however, the academy chose Sillanpää alone. Most of his works were translated into Swedish and often appeared at the same time as the Finnish original. Until recently, however, Per Hallström , the Academy's permanent secretary, did not consider Sillanpää worthy of the award.

The decisive factor was the political situation at a time when Finland was threatened by the Soviet Union (" winter war "). Sillanpää seem to have been aware of these circumstances; because he responded to the message with the words: “This award goes to my country and me in equal measure.” Because of the beginning of the Second World War, this Nobel Prize was hardly noticed outside of Scandinavia. There was no public celebration for the same reason; However, Sillanpää went to Stockholm, where the award was presented to him at a regular meeting of the Swedish Academy. The Nobel Prize for Literature was not awarded until 1944.

Last years of life

The growing debts, the consequences of alcohol abuse and the death of his wife Sigrid in early 1939 led to a state of exhaustion. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in November of that year, Sillanpää was clearly alcoholic . His second wife, Anna von Hertzen, accompanied him to Sweden. In March 1940, his second marriage ended in divorce and Sillanpää was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. After his release, he spent the rest of his life with his children and grandchildren near Helsinki.

The asteroid (1446) was named Sillanpää after the Nobel Prize winner . Sillanpää's house in Töllinmäki is now a museum.

Reception in Germany

The first work completely translated into German was Silja, the maid in 1932 . In the following novel, Eine Mann's Way , the scene of a drinking party was deleted because it was considered incompatible with the qualities of Aryan peasantry . After Sillanpää had published a critical "Christmas letter to the dictators" Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini in the social democratic newspaper Suomen Sosialidemokraatti , his books were banned in National Socialist Germany.

Works

-

Elämä ja aurinko (novel, 1916)

- Sun of Life , German Edzard Schaper (1951)

- Ihmislapsia elämän saatossa ( short stories, 1917)

- Rakas isänmaani ( short stories, 1919)

-

Hurskas kurjuus (novel, 1919)

- The pious misery , German Edzard Schaper, Werner Classen, Zurich 1948

- Die und Auferstehen , German Edzard Schaper, Nobel Prize for Literature No. 38, Coron Verlag, Zurich 1956

- Frommes Elend , German Reetta Karjalainen and Anu Katariina Lindemann, Guggolz-Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-945370-00-1 .

-

Hiltu ja Ragnar (story, 1923).

- Hiltu and Ragnar , German Reetta Karjalainen, Guggolz-Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-945370-05-6 .

-

Grandchildren suojatit (stories, 1923),

- 1938 excerpts under the title “Die kleine Tellervo” as No. 524 in the Insel-Bücherei

- Omistani ja omilleni (1924)

- Maan tasalta (short stories, 1924)

- Töllinmäki ( short stories, 1925)

- Rippi (novella, 1928)

- Jokisen Petterin mieliteot (1928)

- Kiitos hetkistä, Herra ... (Novella, 1929)

-

Nuorena nukkunut (novel, 1931)

- Silja, the maid , German Rita Öhquist (1932);

- Asleep young , German Reetta Karjalainen, Guggolz-Verlag, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-945370-14-8 .

-

Miehen tie (novel, 1932)

- A man's way , German Rita Öhquist (1933)

- Virran pohjalta (novella, 1933)

-

Ihmiset suviyössä (novel, 1934)

- People in the Summer Night , German Rita Öhquist (1936)

- Viidestoista (novella, 1936)

- Elokuu (1941)

-

Ihmiselon ihanuus ja kurjuus (novel, 1945)

- Beauty and misery of life , German Adulin Kaestlin-Burjam (1947)

- Poika eli elämäänsä (1953)

- Kerron Yes Kuvailen (1956)

- Päivä korkeimmillaan (Memoirs, 1956)

- Ajatelmia ja luonnehdintoja (1960)

literature

- Manfred Peter Hein : Finnish literature in Germany. Essays on the Kivi and Sillanpää reception . Vaasa 1991.

- Aarne Laurila: FE Sillanpää romanitaide kirjailijan asenteiden ja kertojan aseman kanalta . Otava, Helsinki 1979.

- Edwin J. Linkomies: FE Sillanpää eräitä peruspiirteitä . Otava, Helsinki 1948

Web links

- Frans Emil Sillanpää ( Memento from January 3, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- http://www.kansallisbiografia.fi/english/?id=700

- Literature by and about Frans Eemil Sillanpää in the catalog of the German National Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the awarding of the award to Frans Eemil Sillanpää in 1939 (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Olof Enckell: Life and work of Frans-Eemil Sillanpää . In: Frans-Eemil Sillanpää: Death and Resurrection . Coron, Zurich [1967], pp. 29-57.

- ^ Kjell Strömberg: Brief history of the award of the Nobel Prize to Frans-Eemil Sillanpää . In: Frans-Eemil Sillanpää: Death and Resurrection . Coron, Zurich [1967], pp. 7-15. Strömberg was a former cultural attaché at the Swedish embassy in Paris.

- ↑ http://www.kansallisbiografia.fi/english/?id=700

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sillanpää, Frans Eemil |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Finnish writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 16, 1888 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hämeenkyrö |

| DATE OF DEATH | 3rd June 1964 |

| Place of death | Helsinki |