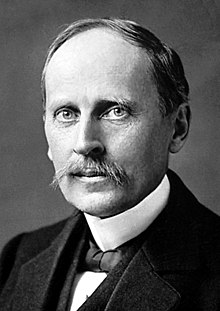

Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland (born January 29, 1866 in Clamecy , Département Nièvre , † December 30, 1944 in Vézelay , Burgundy ) was a French writer , music critic and pacifist . In 1915 he was the third Frenchman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature .

Life and work

The younger years

Rolland was the son of a notary and received a civil upbringing and education. He started writing at the age of eleven. In addition, under the guidance of his very musical mother, he became enthusiastic about music at an early age. In 1880 the father sold his office and the family moved to Paris to give the boy better opportunities to take preparatory classes for the entrance examination (concours) to the École normal supérieure (ENS), the French elite school for teaching subjects at grammar schools ( Lycées ) to prepare. Rolland, who had previously attended the Catholic high school in his hometown, now switched to the Lycée Saint-Louis and in 1882 to the traditional high school Louis-le-Grand , where he made friends with Paul Claudel , among others . In 1886 he was accepted into the ENS, where he studied literature and history until 1889.

After taking the final exam ( license ) and successfully completed the employment test ( agrégation ) for the post of high school professor of history, he immediately took leave and went for two years (1889-1891) as a scholarship holder to the École française de Rome to get material for a to collect a music-historical doctoral thesis (thèse) on the history of the opera before Lully and Scarlatti . In Rome he frequented the salon of the Wagner friend Malwida von Meysenbug , who had been an admirer of Wagner for a long time , and she took him on a visit to Bayreuth . His most important secondary occupation in the Roman years was art history, but he continued to write, for example, reflections on a “roman musical” (1890) and first dramas (1890/91), which however remained unprinted.

Back in Paris in 1892 he accepted a part-time position at the traditional high school Lycée Henri IV and married. After completing his thesis in 1895 and taking the corresponding examination (soutenance), he was seconded to the ENS as a lecturer in art history and later (1904) transferred to the Sorbonne as a lecturer in music history . His marriage, which had remained childless, was divorced in 1901.

In all these years before the First World War, Rolland undertook many, sometimes longer, educational trips through Western and Central Europe, often spent several months on work holidays in Switzerland and wrote narrative texts, essays, music and art historical writings and biographies, for example Beethoven's (1903), Michelangelo , Handel or Tolstois (printed 1903, 1906, 1910, 1911, respectively). The fragment of a biography of Georges Bizet , which he had begun at the suggestion of his son Jacques Bizet , was also created at this time . The numerous dramas that he also wrote remained unpublished or unplayed for a long time. The first pieces accepted and performed were Aërt and Les Loups in 1898 . The latter was the first of an eight-part drama cycle that continued for over 40 years and can be regarded as a kind of epic of the French Revolution. The other pieces (with performance dates) are: Danton (1899), Le Triomphe de la raison (1899), Le Quatorze-Juillet (1902), Le Jeu de l'amour et de la mort (1925), Pâques fleuries (1926) , Les Léonides (1928), Robespierre (1939).

In 1903 Rolland began the work that was to make him known: the 10-volume “ roman-fleuve ” Jean-Christophe (printed 1904–1912). The title hero is the (fictional) German composer Johann-Christoph Krafft, who came to France as a young man, assimilated there with the help of a French friend and thus combined and ennobled his innate “German energy” with “French spirit” in his music can. The Jean-Christophe was a great success and brought him the Nobel Prize in 1915. After 1918 he was also valued by the not a few Francophile Germans who were tired of the talk of Franco-German hereditary enmity and who wanted an understanding between the two peoples. The material served as a template for the television series of the same name by French director François Villiers in 1978 .

In October 1910, Rolland was hit by a car in Paris and suffered injuries that left him unable to work for several months. The accident played a part in his decision to give up his professorship and become a freelance writer (1912).

In 1913/14 he wrote Colas Breugnon , a shorter historical novel in the form of a (fictional) diary from the years 1616/17 (printed in 1919).

Rolland in the First World War

The First World War surprised Rolland in Switzerland. He saw in him the downfall of Europe with dismay. He decided to stay in Switzerland, where he lived in Villeneuve and was able to publish uncensored. Here he met Henry van de Velde .

From October 1914 to July 1915 he volunteered at the International Center for Prisoners of War of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Geneva. He worked in the Civilian Internees Division , which was responsible for reuniting civilian prisoners with their families, searching for missing persons and forwarding letters to relatives. In addition, he published in the Journal de Genève the war-critical series of articles Au-dessus de la mêlée (Eng. Over the turmoil), in which he sharply criticized the warring parties for striving for victory at all costs and ruling out a negotiated peace. Standing above the warring parties, Rolland tried to influence both France (where he was regarded as an “enemy within” because of his allegedly unpatriotic attitude) and Germany (where he was barely heard). After his series of articles appeared as a book in 1915, it became more widely used in the second half of the war. It was now quickly translated into several European languages - but not into German - and, along with the novel Jean-Christophe, played a major role in the fact that Rolland was selected in 1916 for a subsequent award of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915 - “in recognition of the high idealism of his poetry Work and for the warmth and truthfulness with which he presented people in their diversity ” . He donated half of the prize money to the International Central Agency for Prisoners of War of the ICRC.

“ There was another place at this narrow, unplaned wooden table. It was shown to me with a certain awe. Here Romain Rolland had worked every day and tirelessly voluntarily in the service of the Franco-German prisoner exchange for more than two years. And when, in the midst of this activity, he received the Nobel Prize worth almost a quarter of a million, he made it available to charitable work up to the last franc, so that his word testified to deed and deed to be his word. Ecce homo! Ecce poeta! "

Because of his criticism of the war policies of both camps, which he accused as the war went on of destroying themselves in the event of a victory, Rolland became a symbol of the transnational anti-war - and of the international labor movement during the First World War. When Lenin left for Russia from exile in Switzerland in April 1917 , he commissioned the socialist Henri Guilbeaux to invite Rolland to revolutionary Russia. Citing his independence as an “intellectual guardian” over the parties, Rolland turned down the offer. Stefan Zweig meets Romain Rolland during the First World War in Switzerland and is overwhelmed by his person and work.

Rolland as a committed intellectual

After the war, in 1919 with Henri Barbusse he initiated the group Clarté , a peace movement of left-wing intellectuals, and the magazine of the same name. In 1923 he was a co-founder of the magazine Europe , which particularly campaigned for an understanding between France and Germany . The novel Clérambault, histoire d'une conscience libre pendant la guerre from 1920 is also an expression of his transnational pacifism.

Since the Bolsheviks came to power in the Russian October Revolution in 1917, Rolland sympathized with communism and, accordingly, with the French Communist Party founded in 1920 . He became one of the not few pro-communist intellectuals whom the Parti communiste français (PCF) valued as " comrades ". In 1935, despite his poor health, he traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Maxim Gorky , where he was received by Josef Stalin as the representative of the French intellectuals. Rolland then compared Stalin to Augustus , the first emperor of the Roman Empire . In Moscow, Rolland campaigned for the imprisoned writer Victor Serge to be released .

From 1936, however, Rolland kept his distance from the Soviet system because of the Moscow show trials of alleged traitors within the Communist Party during the Great Terror . In the late summer of 1939 he finally broke with the Soviet Union when the Kremlin, after the extradition of Czechoslovakia to Germany by France and Great Britain , concluded the non-aggression pact with National Socialist Germany in the Munich Agreement . He demonstratively resigned from the French "Society of Friends of the USSR".

Romain's maxim “pessimism of the mind, optimism of the will” was raised as a programmatic guiding principle by the Italian Marxist and CP founder Antonio Gramsci as early as 1919 on the pages of the party newspaper L'Ordine Nuovo . Today, the quote is often mistakenly attributed to Gramsci himself as the author.

The later years

In 1922, Rolland rented the Villa Olga at the Hôtel Byron in Villeneuve on Lake Geneva , where he met Mahatma Gandhi. An avenue there is named after him .

In the early 1920s, in addition to extensive journalistic activities, Rolland again tackled a larger novel project: L'Âme enchantée (Eng. The Enchanted Soul ), the four parts of which appeared in three volumes from 1922 to 1933. The plot extends from approx. 1890 to approx. 1930 and tells the story of a woman who accepts to be a single mother and thus emancipates herself first socially, then politically through a left-wing active engagement and finally religiously in a mystical spirituality.

To a certain extent, this development mirrors that of the author, who was active on the left after the war and also began to deal with India and its spiritual and religious traditions, which resulted in a series of articles on Mahatma Gandhi in 1923 , which was published as a book in 1925 . Emil Roniger translated and published his book Gandhi in South Africa-Mohandas Karemchand Gandhi an Indian Patriot in South Africa and published this and other books by Rolland, &. a. the biographies about Beethoven, published by Rotapfel Verlag .

At the end of the 1920s he turned back to Beethoven and started a five-volume monograph that appeared in parts in 1928, 1930, 1937 and finally posthumously in 1945, but remained unfinished.

In 1934 Rolland married Maria Kudaschewa, the Russian translator of his works, with whom he had been in contact since 1923.

In a message to the conference of the World Committee against War and Fascism in Paris in 1935, he addressed a “proud and grateful greeting” to the KPD leader Ernst Thälmann, imprisoned in Bautzen , as “the living symbol of our cause”, as he fought against referred to the threat of war that came from Hitler's Germany. On the first French edition of the book Das deutsche Volk anklags - Hitler's war against the peace fighters in Germany. Rolland wrote the foreword in a book of facts .

In 1937 he retired to the Burgundian pilgrimage site of Vézelay, where he intended to spend his old age. Here he wrote his memoirs, completed among other things the story of his childhood, Voyage intérieur, begun in 1924 (printed in 1942) and a book about the author Charles Péguy (1943) that had been in progress for a long time . In early November 1944, despite his illness, he traveled one last time to Paris, which had been abandoned by the German army in August, to attend a reception at the Soviet embassy. Back in Vézelay, he experienced the almost complete liberation of France at the end of 1944.

After his death, his extensive and varied correspondence and diaries appeared. Numerous works have been reprinted in the decades since then, in Germany around 1977 Johann Christof as a dtv thin print edition and in 1994 the Tolstoy biography by Diogenes . Despite its fame in the first half of the 20th century, Rolland is rarely read today.

The animal rights activist Rolland

Romain Rolland was also an avowed animal rights activist . So he called rawness towards animals and indifference from their torment "one of the gravest sins of the human race" and saw them as "the basis of human depravity". Elsewhere he is reported to have written: “I have never been able to think of these millions of sufferings, endured quietly and patiently, without being oppressed by them. If man creates so much suffering, what right does he have to complain when he is suffering? "

Works

prose

Narrative works

- Jean-Christophe (1904-1912); Johann Christof (childhood and youth, in Paris, Am Ziel), German Otto and Erna Grautoff (1914–1920)

- Colas Breugnon (1919); Master Breugnon, German Erna and Otto Grautoff (1950)

- Clérambault (1920); Clérambault. History of a Free Spirit in War, German Stefan Zweig (1922)

- Pierre et Luce (1920); Peter and Lutz, German Paul Ammann (1921)

- L'âme enchantée (1922-1933); Enchanted Soul (Anette and Sylvie, Sommer), German Paul Ammann (1921–1924)

Critical Writings

- Vie de Beethoven (1903); Ludwig van Beethoven, German L. Langnese-Hug (1918)

- Vie de Michel-Ange (1907); Michelangelo, German Werner Klette (1919)

- Musiciens d'aujourd'hui (1908)

- Musiciens d'autrefois (1908)

- Haendel (1910); The life of GF Handel, German L. Langnese-Hug

- La vie de Tolstoï (1911); The Life of Tolstoy, German OR Sylvester (1922; Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1966)

- Au-dessus de la mêlée (1915); About the battles, German P. Ammann (1950)

- Les précurseurs (1919); The Vorrupp, German P. Ammann (1950)

- Gandhi (1924); Mahatma Gandhi , German Emil Roniger (1924)

Dramas

- Aërt (1897); Aert, German Erwin Rieger (1926)

- Les loups (1898); The Wolves, German Wilhelm Herzog (1914)

- Danton (1899); Danton, German Lucy v. Jacobi and Wilhelm Herzog (1919)

- Le triomphe de la raison (1899); The Triumph of Reason, German SD Steinberg and Erwin Rieger (1925)

- Le quatorze juillet (1902); July 14th, German Wilhelm Herzog (1924)

- Le temps viendra (1903); The time will come, German Stefan Zweig (1919)

- Liluli (1919); Liluli. Dramatic poetry, German Walter Schiff (1924)

- Le jeu de l'amour et de la mort (1925); A game of death and love, German Erwin Rieger (1920)

- Pâques fleuries (1926); Palm Sunday, German Erwin Rieger (1929)

- Léonides (1928); The Leonids , German Erwin Rieger (1929)

- Robespierre (1939); Robespierre, German Eva Schumann (1950)

Diaries

- Over the trenches. From the diaries 1914–1919. With an afterword by Julia Encke ed. by Hans Peter Buohler. CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68347-3 .

- Diary of the war years 1914–1919. With a foreword by Gerhard Schewe, translated from the French by Cornelia Lehmann. Tostari, Pulheim 2017, ISBN 978-3-945726-03-7 .

Correspondence

- Romain Rolland, Stefan Zweig : From world to world. Letters of friendship. With an accompanying word by Peter Handke . Translated from the French by Eva and Gerhard Schewe, from the German by Christel Gersch. Construction Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-351-03413-9 .

Honors

Various schools are named after Rolland, such as the Romain-Rolland-Gymnasium Dresden and a gymnasium of the same name in Berlin. There are also several schools in France that commemorate him. In 1966, a postage stamp was issued in the Soviet Union on the occasion of his 100th birthday.

literature

- Michael Klepsch : Romain Rolland in the First World War. An intellectual in a losing position . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-17-016587-9 .

- Marina Ortrud M. Hertrampf (ed.): Romain Rolland, the First World War and the German-speaking countries: Connections - Perception - Reception. La Grande Guerre et les pays de langue allemande: Connexions - perception - réception . Frank & Timme, Berlin 2018

- Marina Ortrud M. Hertrampf: The European idea by Romain Rolland (1866-1944) , in: Winfried Böttcher ed., Classics of European Thought . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2014, pp. 470–476

- Stefan Zweig : Romain Rolland. The man and the work . Rütten & Loening, Frankfurt 1921 (online)

- Werner Ilberg : Dream and Action. Romain Rolland in his relationship with Germany and the Soviet Union . Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 1950

- Werner Ilberg: Romain Rolland - Essay . Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1951

- Werner Ilberg: The difficult way. Life and work of Romain Rolland . Petermänken, Schwerin 1955

- Ernst Robert Curtius : French Spirit in the 20th Century. Essays on French Literature. Francke Verlag , Bern 1952 (frequent new editions, most recently 1994, pp. 73–115)

- Wolfgang Schwarzer: Romain Rolland 1866–1944. In: Jan-Pieter Barbian (Red.): Vive la littérature! French literature in German translation. Edited and published by Duisburg City Library . 2009, ISBN 978-3-89279-656-5 , p. 30f with ill.

- Klaus Thiele-Dohrmann : Romain Rolland: "I want to be dead". The desperate struggle of the French poet to save Europe from self-destruction. Die Zeit , 36, August 30, 2001 (online) again in: Die Zeit. Welt- und Kulturgeschichte, 13. ISBN 3-411-17603-2 , pp. 526-534, with 1 illustration: "Rolland and Maxim Gorki 1935"

- Christian Sénéchal: Romain Rolland. Coll. Aujourd'hui. La Caravelle, Paris 1933

- Dushan Bresky: Cathedral or Symphony. Essays on "Jean-Christophe." Series: Canadian Studies on German Language and Literature / Etudes canadiennes de langue et littérature allemandes. Herbert Lang, Bern 1973

Web links

- Literature by and about Romain Rolland in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Romain Rolland in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Romain Rolland in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Romain Rolland's estate in the Basel University Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the award ceremony for Romain Rolland in 1915

- Works by Romain Rolland in Project Gutenberg ( currently usually not available for users from Germany )

- Works by Romain Rolland in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Romain Rolland on the Internet Archive

- Doris Jakubec: Romain Rolland. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . November 11, 2010 , accessed February 15, 2020 .

- Romain Rolland in the Names, Titles and Dates of French Literature

- Association Romain Rolland

- Society of Friends of Romain Rollands in Germany V

- Monika Grucza: Europe threatened . Studies on the idea of Europe with Alfons Paquet , André Suarès and Romain Rolland in the period between 1890 and 1914. Diss. Phil. University of Giessen , 2008. online

Footnotes

- ^ Henry van de Velde and Rolland, pp. 402–405. ( PDF )

- ↑ Nicole Billeter: Words against the desecration of the spirit !. War views of writers who emigrated from Switzerland in 1914/1918 . Peter Lang Verlag, Bern 2005, ISBN 3-03910-417-9 .

- ^ Romain Rolland: Au-dessus de la mêlée. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Journal de Genève. , Garnish. September 22, 1914.

- ↑ réédition Petite Bibliothèque Payot, 2013, ISBN 978-2-228-90875-7 .

- ↑ nobelpreis.org ( Memento of the original from October 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Paul-Emile Schazmann: Romain Rolland et la Croix-Rouge. In: Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge. Edited by the ICRC, February 1955.

- ↑ First published in Neue Freie Presse. Vienna, December 23, 1917.

- ^ Henri Guilbeaux: Vladimir Ilyich Lenin: A true picture of his being. Transfer to Ger. u. Mitw. V. Rudolf Leonhard . Verlag Die Schmiede , Berlin 1923, p. 140; Lenin's telegram on p. 48.

- ↑ Stefan Zweig: The world of yesterday. Anaconda Verlag, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-86647-899-2 , p. 353.

- ^ Benedikt Sarnov: Imperija zla. Sud'by pisatelej. Moscow 2011, p. 109.

- ↑ Boris Frezinskij: Pisateli i sovetskie voždi. Moscow 2008, pp. 336–339.

- ↑ Boris Frezinskij: Pisateli i sovetskie voždi. Moscow 2008, p. 474.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Meylan: Page 4, Romain Rolland and India. Retrieved August 30, 2019 .

- ^ Jeanlouis Cornuz: Les caprices: les désastres de la guerre . l'age d'homme, 2000 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ HelveticArchives . Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Avenue Romain Rolland at 46 ° 24 '15.4 " N , 6 ° 55' 53.7" E

- ↑ Quoted from Ruth Wimmer, Walter Wimmer (ed.): Peace certificates from four millennia . Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-332-00095-0 , p. 176.

- ^ Letter to Magnus Schwantje, April 8, 1915 , quoted by Gutz .

- ↑ Quoted from: Questionable prayers at table , under For freedom and the life of all animals! .

- ↑ Volume I: Annette et Sylvie , Volume II: L'Été , Volume III / 1: Mère et fils , Volume III / 2: Mère et fils , Volume IV: L'Annonciatrice (Anna Nuncia) , digitized edition in the Internet Archive .

- ↑ Reading sample (pdf) ( Memento of the original dated August 9, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ In 1987 the correspondence was published by Verlag Rütten & Loening ( ISBN 978-3-352-00118-5 , ISBN 978-3-352-00119-2 )

- ^ Page of the Lycée Romain Rolland in Dijon , accessed on June 3, 2013.

- ^ Frontispiece by Romain Rolland

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rolland, Romain |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 29, 1866 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Clamecy (Nièvre) |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 30, 1944 |

| Place of death | Vezelay |